One Belt, One Road

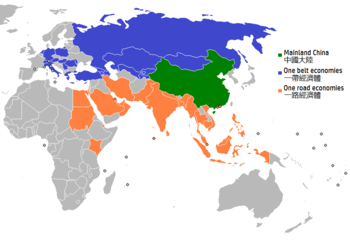

Blue: Countries of the Silk Road Economic Belt

Orange: Countries of the Maritime Silk Road

Under the name One Belt, One Road ( OBOR , Chinese 一帶 一路 / 一带 一路 , Pinyin Yīdài Yīlù - "One Belt, One Road") or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) , projects have been bundled since 2013 that reflect the interests and goals of the People's Republic China under President Xi Jinping inter the establishment and development of continental trade - and infrastructure nets between the PRC and over 60 other countries in Africa , Asia and Europe serve.

There is no coordination between the various projects, and it is also unclear which projects are put under the OBOR umbrella and why. That is why One Belt One Road was called a marketing idea for Xi Jinping, "which disguises itself as an infrastructure project".

The name New Silk Road ( 新 絲綢之路 / 新 丝绸之路 , Xīn Sīchóuzhīlù ) establishes the connection to the historical Silk Road - as for example in the competing project EU-Asia Connectivity Strategy and Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia (TRACECA).

overview

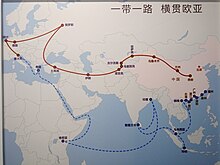

The project ties in with the old trade routes that once connected China with the west, Marco Polo's Silk Road in the north and the maritime expedition routes of Admiral Zheng He in the south. The Belt and Road Initiative now refers to the entire geographical area of the historical international trade corridor " Silk Road " , which was already used in antiquity . It comprises two areas:

- the northern overland routes under the title Silk Road Economic Belt

- the southern sea routes called Maritime Silk Road .

While some states are critical of the project because of possible Chinese influence, others point to the creation of a new global growth engine by connecting and moving together Asia, Europe and Africa.

The G7 industrial country Italy has been a partner for the development of the project since March 2019 . According to estimates, the overall project affects more than 60% of the world's population and around 35% of the global economy . Trade along the Silk Road could soon account for almost 40% of total world trade, with a large part coming from the sea. The land route of the Silk Road appears to remain a niche project in terms of transport volume in the future. On the maritime Silk Road, which is already the route for more than half of all containers moved around the world, deep-water ports are being expanded, logistical hubs are being established and, in particular, new transport routes to the hinterland are being created. In connection with the Silk Road project, China is also trying to network global research activities. There are international partnerships between the Chinese Academy of Sciences, for example with the World Academy of Science in Trieste.

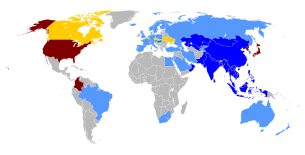

The USA wants to counter the New Silk Road and with it the shift of economic flows via China to Europe and is planning a certification program for infrastructure projects in Asia. Japan and Australia support the program.

Land routes

The Silk Road Economic Belt (" Silk Road Economic Belt ", 絲綢之路 經濟 帶 / 丝绸之路 经济 带 , Sīchóuzhīlù Jīngjìdài ) extends overland from various areas of China across South , West and Central Asia with countries such as Iran , Turkey , Pakistan and Western Russia to Central and Western Europe . With China as the starting country, the international economic cooperation can be geographically grouped into 6 corridors:

- Bangladesh - India - Myanmar

- Indochinese Peninsula

- Mongolia - Russia

- Pakistan

- Central Asia - West Asia

- Europe

China - Indochinese Peninsula

Connects China with the Indochinese countries and further with Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia.

China - Pakistan

The 62 billion US dollar project of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) with the crossing of Pakistan's central land between the approximately 4,700 m high Kunjirap Pass and the port city of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea , partly on the Karakoram Highway is rated as the most ambitious part of the project. A deep-water port is being built in Gwadar in strategic proximity to the approach to the Persian Gulf.

China - Central Asia - West Asia

- In 2009 the Central Asia-China gas pipeline goes into operation, which transports natural gas from Uzbekistan to China (also known as the " Turkmenistan- China gas pipeline ")

- An international airport and a huge goods transshipment point are being built near the city of Korgas in Xinjiang

- Since 2016, the connecting railway Angren pop the Ferghana valley with the rest of the country Uzbekistan , central structure is the Kamchiq tunnel .

- Shortly after the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal with Iran in May 2018, China put a new 8,350 km long rail link between Bayan Nur ( Inner Mongolia ) in northern China and the Iranian capital Tehran into operation: The first train delivered 1,150 tons of sunflower seeds and should complete the connection in 15 days, at least 20 days less than the necessary span at sea.

China - Europe

One route of the New Eurasian Continental Bridge leads through China, Kazakhstan , Russia , Ukraine and Slovakia to Central Europe . At the Chinese-Kazakh and Ukrainian-Slovak borders, there is a change from standard gauge to broad gauge or back. Another route leads from Chongqing via Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus and Poland to Duisburg. In Dostyk or Altynkol in Kazakhstan and on the Polish-Belarusian border, the containers are reloaded due to the different track widths of the railways involved.

Customs clearance has been simplified by the Belarus-Kazakhstan-Russia customs union, which came into force in January 2012 . Duisburg in particular , at the end of the 11,000-kilometer route, is an important logistics hub on the Rhine , the most important transport axis in Central Europe, and is the target of Chinese investments. The Port of Duisburg is planning and developing logistics investments on the New Silk Road itself.

A time overview:

- Since 2008, a commercial freight train connection between China and Germany has been sought under the name Trans-Eurasia-Express .

- Routes to Germany that have existed since 2011 lead to Duisburg , Hamburg and Nuremberg .

- Since 2011, Hewlett-Packard has had laptops and accessories in fifty sealed 40-foot containers run during the summer months with one to three company trains per week from the production facility to Duisburg.

- Since 2012, the Yuxinou has been running a regular freight train between Chongqing and Duisburg .

- DHL trains have been running since June 2013 .

- In 2016, a total of around 1,700 freight trains ran between China and Europe.

- At the end of April 2018, the first direct freight train between China ( Chengdu ) and Austria hit after a journey of more than 9,800 km and 14 days (and thus approx. Four weeks faster than by sea) with 44 containers and the like. a. with electronic components, LED lamps and sleeping bags in Vienna .

- In mid-2018, up to 35 freight trains with a journey time of 12 days arrived in Duisburg every week.

- By 2020, DB Cargo wants to increase its transport capacity on the transcontinental connection to the Far East by 20 percent. In 2020, around 100,000 standard containers (“TEU”) will be transported on the steel silk road.

- In June 2019, a letter of intent between Rostock Port, Port of Verona (Consorzio ZAI Interporto Quadrante Europa) and UTLC ERA (United Transport and Logistic Company - Eurasian Rail Alliance, responsible for the complete door-to-door transport service on the broad-gauge 1520 mm) was transferred the development of multimodal rail transport. The container transports are directed from the logistics center in Verona, Italy, to Rostock, where they reach Baltiysk via the short sea route . From there, goods are transported on the broad-gauge railway via Russia and Kazakhstan to China.

- 2019. On November 11, 2019, the first intermodal container transport reached the port of Baltiysk ( Pillau ). The containers were transported from the Chinese border to Baltiysk on a 1520 mm gauge, reloaded onto a container ship in the port of Baltiysk and driven to the Sassnitz ferry port , where they were reloaded onto container wagons of the 1435 mm gauge and to their destination, the main freight station in Mannheim , transported.

The number of container trains operated by the China Railway Express Co. between China and Europe developed as follows:

| year | All in all | China – Europe | Europe – China | In % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 17th | 17th | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 42 | 42 | 0 | 0 |

| 2013 | 80 | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 308 | 280 | 28 | 10 |

| 2015 | 815 | 550 | 265 | 48 |

| 2016 | 1702 | 1130 | 572 | 51 |

| 2017 | 3673 | 2399 | 1274 | 53 |

Sea routes

The largest part of the Maritime Silk Road ( 海上 絲綢之路 / 海上 丝绸之路 , Hǎishàng Sīchóuzhīlù , also "21st Century Maritime Silk Road", German " Maritime Silk Road" or "Silk Road to the Sea") extends south of China , which aims to extend the Silk Road Economic Belt to include maritime trade . The sea routes known since ancient times as part of the Indian trade are also referred to as the maritime silk road . Already today, more than half of the world's container volume is moving on this long route, which is being logistically and technically expanded in accordance with the Chinese initiative via links to deep-water ports . Extensive infrastructure measures are planned or in progress that will connect China and the whole of Southeast Asia with the Middle East , East Africa and Europe by sea .

The maritime Silk Road, with its links from the Chinese coast, runs south via Hanoi to Jakarta , Singapore and Kuala Lumpur through the Strait of Malacca via the Sri Lankan Colombo across from the southern tip of India via Malé , the capital of the Maldives , to the East African Mombasa from there out to Djibouti , then through the Red Sea over the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean , there via Haifa , Istanbul and Athens to the Upper Adriatic to the northern Italian junction of Trieste with its international free port and its rail connections to Central Europe and the North Sea .

The world's largest and most important container ports in 2017 are located on the Maritime Silk Road , such as Shanghai (40 million TEU), Singapore (33 million TEU), Shenzhen (25 million TEU), Ningbo-Zhoushan (24 million TEU), Busan ( Korea , 21 million TEU), Hong Kong (20 million TEU), Guangzhou (20 million TEU), Qingdao (18 million TEU), Dubai (15 million TEU), Tianjin (15 million TEU), Port Klang ( Malaysia , 12 million TEU), Xiamen (10 million TEU), Kaohsiung ( Taiwan , 10 million TEU), Dalian (9 million TEU), Tanjung Pelepas (Malaysia, 8 million TEU) and Laem Chabang ( Thailand , 7 million TEU). For comparison: Rotterdam (13 million TEU) and Hamburg (9 million TEU).

According to estimates in 2019, the land route of the Silk Road remains a niche project and the majority of the Silk Road trade continues to be carried out by sea. The reasons are primarily due to the cost of container transport. The maritime Silk Road is also considered to be particularly attractive for trade because, in contrast to the land-based Silk Road leading through the sparsely populated Central Asia, there are on the one hand far more states on the way to Europe and on the other hand their markets, development opportunities and population are far larger. In particular, there are many land-based links such as the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor (BCIM). Due to the attractiveness of this now subsidized sea route and the related investments, there have been major shifts in the logistics chains of the shipping sector in recent years. This also applies to the formation and further development of cross-border logistics and trade hubs or partnerships such as in or between Singapore , Shenzhen , Kuala Lumpur or Trieste .

According to K. Schweinsberg, the project is not just an investment in infrastructure; rather, Chinese standards would be disseminated, contacts made and the dissemination of Chinese technology (e.g. electromobility, industrial Internet, artificial intelligence and quantum computers).

Africa

From the Chinese point of view, Africa is important as a market, raw material supplier and platform for the expansion of the new Silk Road - the coasts of Africa are to be integrated. In Kenya's port of Mombasa , China has built a rail and road connection to the inland and to the capital Nairobi . To the north-east of Mombasa, a large port with 32 berths including an adjacent industrial area including infrastructure with new traffic corridors to South Sudan and Ethiopia is being built. A modern deep-water port, a satellite city, an airfield and an industrial area are being built in Bagamoyo , Tanzania . Further towards the Mediterranean, the Teda Egypt special economic zone is being built near the Egyptian coastal city of Ain Suchna as a joint Chinese-Egyptian project .

As part of its Silk Road strategy, China is participating in the construction and operation of train routes, roads, airports and industry in large areas of Africa. In several countries such as Zambia, Ethiopia and Ghana, dams have been built with Chinese help. In Nairobi, China is funding the construction of the tallest building in Africa, the Pinnacle Towers . With the Chinese investments of 60 billion dollars for Africa announced in September 2018, on the one hand sales markets are created and the local economy is promoted, and on the other hand African raw materials are made available for China.

Israel

In Israel, with Chinese participation, the railway line between Eilat on the Red Sea and the port of Ashdod or Tel Aviv on the Mediterranean is being planned and built. The railway line is considered an alternative trade route between Asia and Europe that bypasses the Suez Canal . Deliveries that arrive in Eilat could be transported by rail to the Israeli Mediterranean ports and from there to Europe by ship. The route is called the “Red Med Line” because it connects the Red Sea with the Mediterranean Sea and is to have two rail systems, one for passenger traffic and one for freight. The Shanghai International Port Group has also been building a new container port in the Israeli port city of Haifa since 2018 .

Europe

One of the Chinese bridgeheads in Europe is the port of Piraeus . In total, Chinese companies are to invest a total of 350 million euros directly in the port facilities there by 2026 and a further 200 million euros in associated projects such as hotels. In Europe, China wants to continue investing in Portugal with its deep-water port in Sines, but especially in Italy and there at the Adriatic logistics hub around Trieste . Venice, the historically important European endpoint of the maritime Silk Road, has less and less commercial importance today due to the shallow depth or silting of its port.

The international free zone of Trieste provides in particular special areas for storage, handling and processing as well as transit zones for goods. At the same time, logistics and shipping companies invest in their technology and locations in order to benefit from ongoing developments. This also applies to the logistics connections important for the Silk Road between Turkey to the free port of Trieste and from there by train to Rotterdam and Zeebrugge . There are also direct collaborations, for example between Trieste, Bettembourg and the Chinese province of Sichuan. While direct train connections from China to Europe, such as from Chengdu to Vienna overland, are partially stagnating or discontinued, there are (as of 2019) new weekly rail connections between Wolfurt and Trieste or between Trieste, Vienna and Linz on the maritime Silk Road.

There are also extensive intra-European infrastructure projects to adapt trade flows to current needs. Concrete projects (as well as their financing) to ensure the connection of the Mediterranean ports with the European hinterland are decided among others at the annual China-Central-East-Europe summit launched in 2012 . This concerns, for example, the expansion of the Belgrade-Budapest railway line and connections on the Adriatic-Baltic and Adriatic-North Sea axes. Poland, the Baltic States, Northern Europe and Central Europe are also connected to the maritime Silk Road through many links and are thus logistically networked via the Adriatic ports and Piraeus to East Africa, India and China. Overall, the ship connections for container transports between Asia and Europe will be reorganized. In contrast to the longer East Asia traffic via northwest Europe, the south-facing sea route through the Suez Canal towards the Trieste bridgehead shortens the transport of goods by at least four days.

According to a study by the University of Antwerp, the maritime route via Trieste dramatically reduces transport costs. The example of Munich shows that the transport there from Shanghai via Trieste takes 33 days, while the northern route takes 43 days. From Hong Kong , the southern route reduces transport to Munich from 37 to 28 days. The shorter transport means, on the one hand, better use of the liner ships for the shipping companies and, on the other hand, considerable ecological advantages, also with regard to the lower CO 2 emissions, because shipping is a heavy burden on the climate. Therefore, in the Mediterranean area, where the economic zone of the blue banana meets functioning railway connections and deep-water ports, there are significant growth zones . Henning Vöpel, Director of the Hamburg World Economic Institute, recognizes that the North Range (i.e. transport via the North Sea ports to Europe) is not necessarily the one that will remain dominant in the medium term.

From 2025, the Brenner Base Tunnel will also link the upper Adriatic with southern Germany. The port of Trieste , next to Gioia Tauro the only deep-water port in the central Mediterranean for seventh generation container ships, is therefore a particular target for Chinese investments. In March 2019, the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) signed agreements to promote the ports of Trieste and Genoa. Accordingly, the port's annual handling capacity will be increased from 10,000 to 25,000 trains in Trieste (Trihub project) and a reciprocal platform for promoting and handling trade between Europe and China will be created. It is also about logistics promotion between the North Adriatic port and Shanghai or Guangdong . This also includes a state Hungarian investment of 60 to 100 million euros for a 32 hectare logistics center and funding from the European Union in 2020 amounting to 45 million euros for the development of the railroad in the port city.

financing

(April 2015):

Funding is provided through the " Silk Road Fund " and, since 2016, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (aIIb), a well as the equally involved New Development Bank of BRICS newly established on Chinese initiative Development Bank . The three institutions have been endowed with funds between 40 and 100 billion US dollars each. In total, it has been estimated that $ 1.1 trillion will be needed for the OBOR initiative.

China does not impose any political conditions, but often makes loan commitments conditional on Chinese companies being given priority in the construction projects, so local companies only have limited access. To achieve this, China aims to ensure that the projects are regulated by bilateral agreements and that the tenders are subject to restrictions; for countries of the European Union (EU) this conflicts with the requirement for EU-wide public tenders, where it is not certain that Chinese companies will be awarded the contract.

Basically, there is a risk in the context of this geopolitical reorganization of the trade routes between China and Europe with the various interests of the countries involved in Asia and Africa including the global US strategies that the countries supported by Beijing through the Chinese loans and investments in a debt trap or in Chinese Get dependent. It is estimated that by 2019, the New Silk Road project was granted more than $ 200 billion in loans worldwide, and this amount could increase fivefold over the next ten years.

However, a study published in 2019 by scientists from the University of Duisburg-Essen on behalf of the Bertelsmann Foundation put the fear of the growing Chinese influence into perspective. She saw the West on par with China in investing in the countries of the New Silk Road. Sometimes the West has even greater influence than China. For the study, Western and Chinese financial flows in 25 emerging countries in Central Asia and Africa were compared.

aims

The main goals of the project for China are:

- The stabilization of the borders with the Central Asian states

- The development of the western part of the country, especially the Xinjiang Autonomous Region

- To show a reaction to the American initiatives Pivot to Asia and New Silk Road Initiative of 2011 and to offer or have an alternative to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) originally proposed by the USA . In 2017, however, under Donald Trump , the USA left the TPP.

- In July 2019, China's Defense Minister Wei Fenghe announced that the "One Belt, One Road" initiative would be expanded to include military cooperation .

development

Long before Xi Jinping, there was always talk of a new Silk Road. Since the party chairman proclaimed the project as his idea, officials and politicians have identified him as the inventor of the concept. In fact, investments in international infrastructure have not increased since 2013, so there is no evidence that OBOR actually promotes infrastructure.

Before the project

- In 1990 a continuous rail link between China and Europe was established, the " New Eurasian Continental Bridge ".

- In 1993, the EU decided on the "Europe-Caucasus-Asia" ( TRACECA ) transport corridor, a transport and communication project that aims to better connect Europe with Central Asia .

- With Russia , Kyrgyzstan , Kazakhstan and Tajikistan , China formed the " Shanghai Five " group in 1996 , which expanded in 2001 to include Uzbekistan to become the Shanghai Cooperation Organization .

- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Belarus founded the Eurasian Economic Community in 2000 , which merged into the Eurasian Economic Union in 2015 without Tajikistan, but with Armenia .

Project start 2013

- At the beginning of September 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping gave a highly acclaimed speech in China during a tour through Central Asia at Kazakhstan's Nazarbayev University , announcing the project. The destination is Turkey and Europe as well as the greater Eurasia area

- In October 2013, on a trip to Southeast Asia, Xi announced the construction of a new “maritime silk road”, with the aim of Southeast Asia and the ASEAN countries.

- On 24./25. In October 2013, at a working meeting of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) , Xi emphasized the upgrading of regional economic cooperation - this can be seen as the beginning of the project. In autumn 2013, Chinese politicians presented the project at the ASEAN China summit in Brunei and in the Indonesian parliament in Jakarta .

Further course

- In June 2015, at the EU- China summit in Brussels , it was decided to intensify cooperation, especially in trade and transport (“Eurasian land bridge”).

- The summit of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (“ Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation ”) from May 12 to 14, 2017 in Beijing was attended by representatives from 100 countries and other world leaders, including 29 state and heads of government such as Ethiopia's Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn , Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras , Presidents Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines , Miloš Zeman for the Czech Republic , Recep Tayyip Erdoğan for Turkey , Vladimir Putin for Russia , the Prime Minister Najib Razak for Malaysia and Nawaz Sharif for Pakistan , also z. B. the Executive Director of the World Bank , Christine Lagarde . For Germany , the Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy Brigitte Zypries took part, for Switzerland her Federal President Doris Leuthard , and Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond represented the United Kingdom . Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged the equivalent of around 124 billion US dollars for OBOR and said: "The fame of the ancient Silk Road shows that geographical dispersion is not insurmountable."

- Implementation of the concept stalled in 2018 due to financial concerns from China. In the summer of 2018, the New York Times reported from Beijing government circles that China was carrying out a comprehensive re-evaluation of all Silk Road projects. In 2019, the subsidies provided by China for the project were used up prematurely, which covered 40% of the costs of rail transport. In 2020 they are to be reduced to 30% and in 2021 to 20%. A stagnation or even a decline in these loads is therefore expected. Chinese President Xi Jinping has ordered an investigation into the relationship between the value of goods being transported and the subsidies spent on them. The announcement alone meant that fewer trains were sent on the journey, but they were then fully utilized.

- Malaysia began a change in relations with China in 2018 after Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad took office . In August 2018 it halted the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) rail project as well as two gas pipeline projects; these projects would have given China access to the Indian Ocean . According to Mahathir, Malaysia could not afford the projects given its national debt, and there was no need for this infrastructure. At the same time, Mahathir warned of China's growing influence in poor countries. The projects were negotiated under Mahathir's predecessor, Najib Razak . He was voted out of office following allegations of corruption, some of which also affect China's investments. The East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) rail project was restarted on July 25, 2019, and the line should be completed by December 2026.

- 37 heads of state and government, a total of 5000 representatives from more than 100 countries, came to the 2nd summit of the project in Beijing in April 2019. The Chinese state and party leader Xi Jinping announced higher standards, a "... open, clean and green development". However, the German government remains skeptical.

Risks

At the beginning of 2019, an international team of researchers in the specialist magazine Current Biology warned of the risks that in some regions of the world the introduction of alien species could impair biodiversity and thereby damage ecosystems.

See also

- Asian highway project

- Silk Road Strategy (USA)

- The Great Game (Historical conflict between Great Britain and Russia for supremacy in Central Asia)

- Trans-Asian Railway

- Trans-Eurasia-Express

- Trans-European Networks

- Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan pipeline

- World power grid

- Yuxinou

literature

- Breinbauer, Andreas: The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative and Its Implications for Europe. In: Breinbauer u. a .: Emerging Market Multinationals and Europe. Challenges and Strategies. Springer, Cham, 2019, 213-235, ISBN 978-3-030-31291-6 .

- Peter Frankopan : The new silk roads: present and future of our world. Rowohlt, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-7371-0001-4 . (English: The New Silk Roads. The Present and Future of the World. Bloomsbury Publishing, London et al. 2018).

- Marcus Hernig : The Renaissance of the Silk Road: The way of the Chinese dragon into the heart of Europe . FinanzBook Verlag, 2018, ISBN 978-3-95972-138-7 .

- Wolf D. Hartmann et al .: China's New Silk Road. Cooperation instead of isolation - the reversal of roles in world trade . Frankfurter Allgemeine Buchverlag, Frankfurt am Main 2017, ISBN 978-3-95601-224-2 .

- Tom Miller: China's Asian Dream: Empire Building along the New Silk Road . Zed Books, 2017, ISBN 978-1-78360-923-9 .

- Norbert Lacher: The New Silk Road - Geopolitics and Power , Südwestdeutscher Verlag für Hochschulschriften, Saarbrücken 2016, ISBN 978-3-8381-5248-6 .

- Uwe Hoering: The Long March 2.0. China's New Silk Roads as a development model , VSA: Verlag, Hamburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-89965-822-4 .

Documentation

- The New Silk Road - China's Reach for Global Power , 3sat / NZZ format from June 15, 2018

- New Silk Road - China's favorite showcase project , arte , France 2016

Web links

-

badische-zeitung.de , February 12, 2018, Christian Mihatsch: China is collecting ports around the globe

- June 7, 2018, Interview with Gernot Erler : Shift of power to the east

- china.org.cn: The Silk Road Economic Belt

- ciis.org.cn: Silk Road Economic Belt - Business News and International Network

-

deutschlandfunk.de , background , May 21, 2016, Agnes Handwerk: China on a shopping spree

- Wirtschaft am Mittag , November 16, 2016, Steffen Wurzel: China's players are getting bigger

- One World , May 13, 2017, Axel Dorloff: The "New Silk Road" project

- From cultural and social sciences , June 14, 2018, Peter Leusch: China's historic ways to the west

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Eyck Freymann: 'One Belt One Road' Is Just a Marketing Campaign . The Atlantic , August 17, 2019

- ↑ FAZ.net February 23, 2020: The coronavirus and Italy's relationship with China

- ↑ Heinrich von Pierer : 100 countries, 900 billion euros investments - Why Germany must not be left out in the mega-project Silk Road , in: Focus from March 19, 2018.

- ↑ See Bernhard Simon: Can The New Silk Road Compete With The Maritime Silk Road? in The Maritime Executive from January 1, 2020.

- ^ Jeff Desjardins: Visualizing China's Most Ambitious Megaproject: One Belt, One Road. Retrieved March 17, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ a b c The Silk Road Initiative | Mercator Institute for China Studies (not freely accessible). Archived from the original on May 23, 2018 ; accessed on May 22, 2018 (English).

- ↑ Cf. Marcus Hernig: The Renaissance of the Silk Road (2018), p. 7 ff.

- ↑ Ethan Masood: How China is redrawing the map of world science. In: Nature . Volume 569, number 7754, May 2019, pp. 20-23, doi: 10.1038 / d41586-019-01124-7 , PMID 31043732 .

- ↑ Christoph Hein: How America wants to counter China's New Silk Road in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on November 11, 2019.

- ^ The New Side Street . AKADS, Saarbrücken 2017. ISBN 978-3-7438-3122-3 , p. 71

- ↑ Bala Ramasamy, Matthew Yeung, Chorthip Utoktham and Yann Duval, “Trade and trade facilitation along the Belt and Road Initiative corridors”, ARTNeT Working Paper Series, no. 172, November 2017, Bangkok, ESCAP. (PDF) Retrieved April 27, 2019 (English).

- ↑ a b c d Tom Phillips: China's Xi lays out $ 900bn Silk Road vision amid claims of empire-building. May 14, 2017, accessed May 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Jon Boone: A new Shenzhen? Poor Pakistan fishing town's horror at Chinese plans. February 4, 2016, accessed May 19, 2018 .

- ^ Social Science Research Network (SSRN), papers.ssrn.com: What Is One Belt One Road? A Surplus Recycling Mechanism Approach (English, German: "What is One Belt One Road? A surplus recycling mechanism approach")

- ↑ Nadine Godehardt: China's New Silk Road Initiative - Science and Politics Foundation - German Institute for International Politics and Security China's “New” Silk Road Initiative, p. 17 - Accessed November 1, 2016 - swp-berlin.org - Online

- ↑ Turkmenistan is expanding the Silk Road . In: top-energy-news . March 16, 2016 ( top-energy-news.de [accessed on May 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Sputnik: Uzbekistan starts delivering gas through the Central Asia-China gas pipeline. Retrieved May 19, 2018 .

- ↑ China is reaching for Central Asia's oil and gas. Retrieved May 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Prof. Dr. Ralph Wrobel: "Shanghai Cooperation Organization": China's new silk road to Central Asia - East Asian Association. Accessed on May 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education: Oil and Gas in the Caspian Region | bpb. Retrieved May 19, 2018 .

- ^ After the US exit from the nuclear deal: China starts new trade route with Iran . In: Spiegel Online . May 11, 2018 ( spiegel.de [accessed May 13, 2018]).

- ↑ New Silk Road: China opens train connection to Iran . In: ZEIT ONLINE . ( zeit.de [accessed on May 18, 2018]).

- ^ Freight train from China arrived in Vienna ntv.de on April 27, 2018

- ↑ Freight train connections China – Western Europe - The Steel Silk Road In: industrie.de , April 1, 2014, accessed on January 22, 2020.

- ^ New Silk Road: First direct train from China has arrived in Vienna . In: Spiegel Online . April 27, 2018 ( spiegel.de [accessed May 13, 2018]).

- ↑ New Silk Road: How China Reaches Europe , plus-minus from August 1, 2018

- ↑ The Steel Silk Road - freight train traffic from China is growing rapidly in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung from June 15, 2019.

- ^ New multimodal route China-Europe via port of Rostock. Retrieved June 14, 2020 (American English).

- ^ NN: The first container train from China to Europe in multimodal traffic . In: OSJD-Bulletin 5–6 / 2019, p. 86.

- ↑ Pyotr Kurnkov: Container traffic between China and Russia on the Silk Railroad . In: OSJD Bulletin 5–6 / 2019, pp. 36–48 (38).

- ↑ Marcus Hernig: The Renaissance of the Silk Road (2018), p. 15.

- ↑ China Unveils Action Plan on Maritime Silk Road. 2015, accessed on September 3, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Bernhard Zand: The Maritime Silk Road: China's High Seas Ambitions . In: Spiegel Online . September 8, 2016 ( spiegel.de [accessed May 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Dietmar Pieper: Geopolitical Laboratory: How Djibouti Became China's Gateway To Africa . In: Spiegel Online . February 8, 2018 ( spiegel.de [accessed May 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: Chinas neue Seidenstrasse (2017), p. 51ff .; Emanuele Scimia: Trieste aims to be China's main port in Europe in the Asia Times from October 1, 2018; Willi Mohrs: New Silk Road. The ports of Duisburg and Trieste agree to cooperate. In the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung of June 8, 2017.

- ↑ zeit.de , June 28, 2017, Felix Lee: China's new continent

- ↑ Bernhard Simon: The natural limits of the New Silk Road. In: Manager Magazin 5/2019, from May 2, 2019

- ↑ See Bernhard Zand: China conquers the water in Der Spiegel from September 9, 2016.

- ↑ See Global shipping and logistic chain reshaped as China's Belt and Road dreams take off in Hellenic Shipping News of December 4, 2018.

- ↑ See Andrew Wheeler: How Trieste could become the Singapore of the Adriatic in Asia Shipping Media - Splash247 of February 19, 2019.

- ↑ Zeno Saracino: Cina, Dipiazza incontra il vicesindaco della città-porto Shenzhen. In: Trieste All News. October 18, 2019, accessed October 19, 2019 (it-IT).

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Klaus Schweinsberg: Die Seifenstrasse in Manager Magazin 5/2019, p. 92.

- ↑ Johnny Erling: China's Great Leap to Africa in Die Welt, September 3, 2018.

- ↑ Cf. Andreas Eckert: With Mao to Dar es Salaam in: Die Zeit from March 28, 2019, p. 17.

- ↑ Dominik Peters: The world power China is buying into the start-up country Israel in Der Spiegel from April 20, 2019; Sabine Brandes: The train comes to Jüdische Allgemeine on February 13, 2012.

- ↑ Cf. Zacharias Zacharakis: Chinas Anker in Europa in: Die Zeit from May 8, 2018.

- ↑ See Andrea Rossini: Venezia, si incaglia la via della Seta. Porto off limits per le navi cinesi in TGR Veneto (RAI) from January 16, 2020.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. The Chinese want to invest in the port of Trieste. Goods traffic on the Silk Road runs across the sea in: Die Presse from May 16, 2017.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer: Many European countries fear China's influence. Portugal believes in the Silk Road in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung of December 6, 2018.

- ↑ Cosco is investing again in a large MPP fleet . In: Hansa International Maritime Journal , November 20, 2018.

- ↑ Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: China's new silk road. Frankfurt am Main 2017, p. 59.

- ↑ The Chinese want to invest more in the port of Trieste in Kleine Zeitung from May 16, 2017.

- ↑ Marco Kauffmann Bossart: China's Silk Road Initiative brings investments and jobs to Greece. At what price? in Neue Zürcher Zeitung from July 12, 2018.

- ↑ See P&O Ferrymasters Launches New Intermodal Services Linking Turkey To Rotterdam And Zeebrugge Hubs Via Trieste. in Hellenic Shipping News from January 8, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Port of Trieste strengthens intermodal connections to Luxembourg in Verkehrsrundschau on June 12, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. Gerald Pohl: New Silk Road: China is pushing for Europe in: Die Presse of September 17, 2019.

- ^ Port of Trieste on course for growth: New rail connection to Rostock . In; The trend from October 17, 2018.

- ^ Frank Behling: Port train Kiel – Trieste. From the fjord to the Mediterranean . In the Kieler Nachrichten on January 25, 2017.

- ↑ See Triest - A World Port for Bavaria in the Bavarian State Newspaper of November 30, 2018.

- ↑ Marcus Hernig: The Renaissance of the Silk Road (2018), p. 112.

- ↑ Cf. Bruno Macaes: China's Italian advance threatens EU unity. In the Nikkei Asian Review of March 25, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Werner Balsen: The new view of Europe - from the south in DVZ on July 10, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Alexandra Endres: Shipping is just as bad for the climate as coal in Die Zeit of December 9, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Harry de Wilt: Is One Belt, One Road a China crisis for North Sea main ports? in World Cargo News of December 17, 2019.

- ^ German seaports: Local competition, global weakness

- ↑ See Matteo Bressan: Opportunities and challenges for BRI in Europe in Global Times of April 2, 2019.

- ↑ See Andreas Deutsch: Shifting Effects in Container-Based Hinterland Transport (2014), p. 143.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Johnny Erling: Beijing reaches out to Italian ports in: Die Welt from March 21, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Alexander Zwagerman: The eternal city welcomes the eternal Red Emperor: Italy's embrace of Beijing is a headache for its partners , in: Hong Kong Free Press, March 31, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Guido Santevecchi: Di Maio e la Via della Seta: “Faremo i conti nel 2020”, siglato accordo su Trieste in Corriere della Sera on November 5, 2019.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Trieste to become Hungary's sea exit , The Budapest Business Journal, June 21, 2019.

- ↑ Asia House Foundation: Old Silk Road in a New Dress - China's Globalization Offensive (supplement to taz on October 28, 2016).

- ↑ China Manager The largest investment program in the world . In: manager magazin . ( manager-magazin.de [accessed on May 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Bergen, Ben: The New Silk Road . AKADS, Saarbrücken 2017, p. 78 ( akads.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Asia House Foundation: Old Silk Road in a new guise - China's globalization offensive; Supplement to the taz on October 28, 2016

- ↑ Asia House Foundation: Old Silk Road in a New Dress - China's Globalization Offensive [1] - Retrieved May 14, 2017 - giga-hamburg.de - Online

- ↑ Marco Kauffmann Bossart: A silk road to Belgrade. www.nzz.ch, June 17, 2016, accessed on December 2, 2017 .

- ↑ Matthias Benz: China ensnares the Eastern Europeans with the "new silk road". www.nzz.ch, November 27, 2017, accessed on December 2, 2017 .

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Hannelore Crolly: On the "New Silk Road" into financial dependence on China , Die Welt, December 1, 2018.

- ↑ Michael Bender: Freeing China's South Asian string of 'little perarls' in Washington Times, December 3, 2018.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Georg Blume: Europe overslept the New Silk Road , Der Spiegel, March 26, 2019.

- ↑ Thorsten Mumme: The fear of China's New Silk Road is unfounded. In: Der Tagesspiegel. September 2, 2019, accessed September 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Study: West on par with China in investments in the Silk Road countries. In: Zeit Online. September 2, 2019, accessed September 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Bertelsmann Stiftung: West invests more in “New Silk Road” than China. In: Focus Online. September 2, 2019, accessed September 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Markus Taube et al .: What the West is investing along China's new Silk Road. A comparison of Western and Chinese financial flows. Ed .: Bertelsmann Foundation . Gütersloh 2019 ( bertelsmann-stiftung.de [PDF; accessed on September 6, 2019]).

- ↑ https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/so-will-china-die-neue-seidenstasse-militaerisch-absichern-16289164.html

- ↑ https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/studien/2014_S09_gdh.pdf page 8, accessed on May 9, 2019

- ↑ https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/studien/2014_S09_gdh.pdf page 8, accessed on May 9, 2019

- ↑ Nadine Godehardt: China's New Silk Road Initiative - Science and Politics Foundation - German Institute for International Politics and Security China's "new" Silk Road Initiative, p. 5 - Accessed November 1, 2016 - swp-berlin.org - Online

- ↑ Beijing summit on the "New Silk Road" opened. In: Deutsche Welle . May 12, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2017 .

- ↑ Federal President in China - Doris Leuthard wants to strengthen friendship. In: SRF . May 13, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2017 .

- ↑ Georg Blume: Setback for China's Silk Road. In: www.spiegel.de. July 21, 2018, accessed July 21, 2018 .

- ↑ pd / mr: Soon fewer freight trains from China to Europe? . In: Eisenbahn-Revue International 12/2019, p. 642.

- ↑ Manfred Rist: Malaysia cancels Chinese Belt and Road projects. In: www.nzz.ch. August 22, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018 .

- ↑ Setback for China's "New Silk Road": Railway line and pipelines put on hold . orf.at, August 22, 2018, accessed on August 22, 2018.

- ^ Work resumes on Malaysia's East Coast Rail Link. In: straitstimes.com. July 25, 2019, accessed on July 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Malaysia: Minister of Transport inaugurates relaunch for the construction of the East Coast Rail Link. In: lok-report.de. July 26, 2019, accessed July 27, 2019 .

- ↑ China's charm offensive , tagesschau.de, April 26, 2019, accessed on May 9, 2019

- ↑ Conference on the Silk Road ends with contracts worth billions , Die Zeit, April 27, 2019, accessed on May 9, 2019

- ↑ China Promises Better Silk Road , taz, April 26, 2019, accessed May 9, 2019

- ↑ Xuan Liu, Tim M. Blackburn, Tianjian Song, Xianping Li, Cong Huang, Yiming Li: Risks of Biological Invasion on the Belt and Road. In: Current Biology. January 24, 2019, accessed January 24, 2019 .

- ↑ China's “new silk road” threatens ecosystems. In: www.nzz.ch. January 24, 2019, accessed January 24, 2019 .

- ↑ See Peter Rásonyi: China's project of the century challenges the West in Neue Zürcher Zeitung from July 21, 2018.