Bertha von Suttner

Bertha Sophia Felicita Freifrau von Suttner , née Countess Kinsky von Wchinitz and Tettau , pseudonyms: B. Oulot , Jemand (born June 9, 1843 in Prague ; † June 21, 1914 in Vienna ), was an Austrian pacifist , peace researcher and writer . In 1905 she was the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Early years

Bertha von Suttner, a native Countess Kinsky von Wchinitz and Tettau, came from a Bohemian aristocratic family. Her father Franz Joseph Graf Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau, who died before she was born at the age of 75, was a general, her maternal grandfather was captain of the cavalry . She grew up with her mother Sophie Wilhelmine (née von Körner, distantly related to the poet Theodor Körner ) in the aristocratic environment of the Austro-Hungarian k.k. Monarchy and its militaristic background. As a child and teenager, she learned several languages, occupied herself with music and traveled a lot.

After her father's inherited fortune had largely been used up (not least because of her mother's passion for gambling), Bertha took a position as governess with the industrialist Karl Freiherr von Suttner in Vienna in 1873 and gave the four daughters of the family lessons in music and language. During this time she fell in love with Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner , who was seven years her junior and the youngest son of the Suttners. In 1876 she traveled to Paris, where she was Alfred Nobel's private secretary for almost two weeks . Arthur's mother had fired Bertha in order to end the relationship between Bertha and her son. However, she got her the job at Nobel in order not to throw her penniless out of the house. Nobel was soon called to his homeland by the Swedish king .

Bertha returned to Vienna and secretly married Arthur Gundaccar on June 12, 1876, against his parents' wishes. Thereupon Arthur Suttner was disinherited, and the couple moved for more than eight years, from 1876 to 1885, to Princess Jekatarina Dadiani of Mingrelia in the Caucasus in Georgia . There the two lived from casual jobs under difficult financial circumstances. Bertha made a living as a language teacher, wrote entertainment novels and translations. The translation of the Georgian national epic The Recke in a tiger skin into German remained unfinished . Arthur drew plans and wallpaper samples. The last years of their stay in Georgia, which Bertha von Suttner later remembered as a happy time despite the difficult circumstances, they lived in Tbilisi .

In 1877, with the beginning of the Russo-Turkish War , Arthur began to publish reports about the war and about the country and its people in German weekly newspapers. Bertha von Suttner also began her journalistic activities in 1877 and , like her husband, had great success under the pseudonym B. Oulot. She wrote short stories and essays for Austrian newspapers , her husband wrote war reports and travel stories. In 1885 they returned to Vienna together, reconciled with the family and moved into the family castle in Harmannsdorf (municipality of Burgschleinitz-Kühnring) in Lower Austria .

Journalistic and writing activity

After her return, Bertha von Suttner remained active as a journalist, focusing on a more peaceful society and devoting herself to the subject of pacifism . In 1886 she wrote the book High Life , in which she addressed the issue of respect for people and their free decision-making power. Shortly afterwards, through a discussion with the French philosopher Ernest Renan , she learned of the existence of the International Arbitration and Peace Association , which the British Hodgson Pratt had founded in 1880.

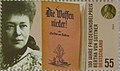

"Down with the weapons!"

In the autumn of 1889, at the age of 46, she published the pacifist novel The Arms Down! , which caused a sensation and made Bertha von Suttner one of the most prominent representatives of the peace movement . She described the horrors of war from the perspective of a wife and hit the nerve of society, which at that time was engaged in heated discussions about militarism and war . This book became her greatest literary success. It was published in 37 editions and has been translated into twelve languages. In her obituary for Bertha von Suttner, Marie Eugenie delle Grazie wrote about this novel: “Perhaps one day we will know little or just so much more about that novel than the literary powers decree. But his title is already on the first page of a new world history! "

With the novel, Suttner participated in the pacifist discourse of the time. She defined peace as a normal state guaranteed by natural law, which the war faces as a consequence of human “delusional delusions”. This makes the right to peace enforceable under international law. Suttner refers to a dynamic historical conception of the Darwinian theory of evolution, which has been applied to the social, and assumes a constant higher development of mankind in the sense of a selection of the “noblest” (belief in progress).

The couple spent the winter of 1890/91 in Venice. Bertha von Suttner and others suggested the establishment of a “Venice Peace Society”. This is how she got to know the Marchese Benjamino Pandolfi, through whom other representatives of the "Interparliamentary Conferences" were introduced to her. From 1910 onwards, the Interparliamentary Conferences were called “Interparliamentary Union”.

Peace and women's movement

On September 3, 1891 Bertha von Suttner demanded in an article in the Neue Freie Presse the establishment of an "Austrian Society of Friends of Peace" with the words:

"That is why it is necessary that wherever there are supporters of peace, they should also publicly acknowledge themselves as such and participate in the work according to the measure of their strength."

The success of this call was overwhelming. Bertha von Suttner was immediately appointed the first female president of the Austrian Society of Friends of Peace, which she remained until her death in 1914. In November 1891, on the occasion of the World Peace Congress in Rome, she was elected Vice President of the International Peace Office and in 1892 founded the German Peace Society , which within a short time had over 2,000 members. As a result, she took part in several international peace congresses, for example in Bern in 1892 , in Antwerp in 1894 and in Hamburg in 1897 . On June 3, 1897, she presented Emperor Franz Joseph I (1830-1916) with a list of signatures with a plea for an international arbitration tribunal.

In 1898 Bertha von Suttner turned against animal experiments with her writing Schach der Qual (at that time: vivisection ). One of their reasons was that pity, "this infallible attribute of noble humanity", is a strong hope of social progress and only compassionate people would work to eradicate oppression, abuse of violence, cruelty and misery: "Anyone who stifles pity somewhere, who gives hard-heartedness a privilege, harms the world and posterity far more than can be used by any physiological and medical - problematic - results." Physiologists compared von Suttner with hunters and war leaders they as "our refined cruel perpetrators" who acted for a motive "which is so strong in its power of habit or duty that it drowns out any other understanding in them".

In 1899 she was involved in the preparations for the First Hague Peace Conference in The Hague , at which government representatives dealt with issues of national and international security, disarmament and the establishment of an international arbitration tribunal. However, the results expected by the initiators were not achieved. Armed conflicts could be settled, but an end to all hostilities or a reduction in armaments and the establishment of international arbitration tribunals did not prevail.

"Religion does not justify the stake, the concept of fatherland does not justify mass murder, and science does not sanctify animal torture."

Because her husband was unable to travel due to a serious illness in 1902, Bertha von Suttner took part alone in a peace congress in Monaco , but then traveled to Bohemia with her husband to relax . Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner died on December 10, 1902 in Harmannsdorf. As a result, the Suttner couple's estate had to be auctioned off due to over-indebtedness, and Bertha von Suttner moved back to Vienna , where she continued to publish (including in the German-language Hungarian newspaper Pester Lloyd ). In 1903 she traveled again to Monaco and took part in the opening of the "Institut International de la Paix", which Prince Albert I (1848-1922) had founded.

In June 1904 Bertha von Suttner was one of the most important participants in the “International Women's Conference” of the International Women's Council in Berlin . This conference ended with a peace demonstration in the Philharmonie , where Bertha von Suttner gave a lecture. In the same year she toured the United States of America . The reason for this was the World Peace Congress in Boston ( Massachusetts ). She traveled from town to town and gave up to three lectures a day. Her reputation had preceded her, and so she was invited to the White House in Washington DC to meet President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) . The "Peace Bertha", as she was called somewhat disparagingly in German national circles, came back enthusiastically from the USA. Their seven-month trip had been a triumphant advance, and it had become clear that the peace movement in the USA was much more advanced than in Europe. According to newspaper and magazine reports at the time (according to the Czech Ženský svět ) , she was surprised by the general peace activities and peace teaching in American schools.

Nobel Peace Prize and Late Years

On December 10, 1905, Bertha von Suttner received the Nobel Peace Prize that she had suggested , which she accepted on April 18, 1906 in Kristiania . Although Alfred Nobel had already thought of Bertha von Suttner as the winner of the first award in 1901, she was only considered in this fifth prize round.

In her speech to the Nobel Prize Committee, she outlined the three program points that she had developed for overcoming conflicts between states without violence:

- Arbitration treaties to resolve conflicts between states by peaceful means

- a peace union of all states , which must repudiate every attack of one state against another with common strength

- an international institution that acts as a court of justice on behalf of the peoples

In 1907 she was also present at the second peace conference in The Hague, which more than in 1899 was focused on regulations of martial law rather than on the question of a stable peace order. As a result, she tried increasingly to provide information about the dangers of international armament and the interests of the arms industry. In 1908 she drew attention to the danger of an international war of annihilation with a very far-sighted and consistent analysis :

“We have such powerful forces of annihilation that any battle waged by two opponents would be nothing but double suicide. If you can pulverize any mass of people or houses with the push of a button, at any distance, then I don't know which tactical and strategic rules could be used to carry out a peoples duel with such means. "

In 1912 she went on a second trip to America, which took her as a lecturer from the east coast to the west coast in over fifty cities.

Death and inheritance

On June 21, 1914, a few weeks before the start of the First World War , against which she had repeatedly warned, Bertha von Suttner died of cancer . The next World Peace Congress was scheduled for autumn 1914. It should have taken place in Vienna. Alfred Hermann Fried passed on her last words in his obituary: “Put down your arms! - - tell many - many. "

Bertha von Suttner was a member of the Austrian association “Die Flamme”, which promoted cremation . She sponsored the construction of the first German crematorium in Gotha and decreed in her will that her body should be transferred to Gotha and cremated there. The urn with its ashes is kept in the Columbarium in the Gotha Crematorium .

Her estate is mainly kept in the Bibliothèque des Nations Unies in Geneva ; individual documents can also be found in the Missouri Historical Society Collections ( St. Louis ) and in the Federal Archives in Koblenz. Parts of the estate are exhibited in the Krahuletz Museum in Eggenburg . The only surviving recording of her voice from 1904 - certified by a diary entry - is kept in the Austrian media library .

Appreciations

In a speech at the opening of the International Women's Congress on International Understanding in 1917 in Bern , Stefan Zweig paid tribute to her memory. On the 70th anniversary of her death in 1984, the GDR Peace Council laid a wreath in the Gotha Columbarium, and the church historian Walter Bredendiek gave a commemorative speech.

Numerous cities in Austria and Germany keep their memory by naming schools, squares and streets as well as renaming the Schönau Bridge in Graz to Bertha-von-Suttner-Friedensbrücke. The GDR in particular had streets and public institutions named after her. In January 2018, a total of 167 streets and squares in Germany were named after her, including squares in Düsseldorf and Bonn . Bertha-von-Suttner-Platz in Bonn celebrated its 70th anniversary in August 2019. Among the schools that bear her name are grammar schools in Andernach , Neu-Ulm , Oberhausen, Potsdam-Babelsberg, Vienna and Berlin-Reinickendorf, comprehensive schools in Kaiserslautern, Dormagen and Siegen, secondary schools in Essen, Cologne-Vogelsang, Osnabrück and Stuttgart- Mühlhausen and other schools in Geesthacht, Windecken, Mörfelden-Walldorf , Ettlingen and Graz. Asteroid (12799) from Suttner in the asteroid belt was named in her honor in 2001.

Portraits of Bertha von Suttner can be found on the Austrian 1000 Schilling banknote from 1970, on the Austrian 2 euro coin and on a commemorative coin of the Federal Republic of Germany in 2005. Her portrait can also be found on postage stamps, including a special stamp designed by Gerhard Voigt GDR from 1964 For the world peace , a stamp of the Deutsche Bundespost published in 1991 in the series Women of German History and a German special stamp published on the 100th anniversary of the Nobel Prize in 2005 .

In the Vienna district of Wieden there is a monument created by Siegfried Charoux in 1959 . In 1963 a memorial plaque was placed on the house where she died at Zedlitzgasse 7 in Vienna. On World Day of Peace 2013, a 2.50 meter high stainless steel stele by the Finnish artist Sirpa Masalin was unveiled in her honor on Bertha-von-Suttner-Platz in Bonn.

Since 1993 the Bertha von Suttner Foundation of the DFG-VK has been committed to projects to “promote international understanding, peace and international cooperation”.

On December 10, 2019 Bertha von Suttner was honored with a doodle by Google .

reception

Suttner's calls for peace and disarmament met with broad social resonance throughout Europe. Reading "Die Waffen Nieder" inspired many people - like Helene Stöcker - to become peace activists. In his history of the First World War , the historian Jörn Leonhard found that Bertha von Suttner had become a figure of identification of that direction of pacifism that “qualified the war as immoral”, in contrast to a direction represented by Johann von Bloch and Norman Angell , which the Tried to refute the rationality of war with scientific methods.

music

Franz von Suppè wrote down the choir Die Waffen for the World Peace Congress in Bern in 1892 after Bertha von Suttner's main work (text: Julius Steinberg).

A text from Bertha von Suttner's “A Testament” is based on Alexander Doents composition Heilig ist die Freude for mixed choir and violin, which premiered on May 11, 2014 in Eggenburg - near Harmannsdorf Castle.

Movies

The director Harald Braun filmed Suttner's life in 1952 in Heart of the World with Hilde Krahl in the lead role. In 2014, several television productions were made in her memory, including the biopic A Love for Peace - Bertha von Suttner and Alfred Nobel (Madame Nobel) , which was produced by ORF , Degeto and Bayerischer Rundfunk , and the series Die Waffen Down! , produced by Think INK Group, Okto , which premiered between March 8th and December 26th, 2014.

Fonts

A bibliography by Suttner created by Gerhard Lindenstruth in 1993 is freely available (last updated in 2014).

- A bad person. Munich 1885.

- Daniela Dormes. Munich 1886.

- High life. 1886

- The machine age. 1889.

- Down with the weapons! 1889. (Reprint: Deutsche Literaturgesellschaft, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-940490-45-2 . English edition Longmans Green, London 1892)

- as editor: Put down your arms! Monthly Magazine, 1892–1899. Digitized editions

- Before the thunderstorm. Vienna 1894.

- Lonely and poor. Dresden 1896.

- Chess of Agony. 1898.

- The Hague Peace Conference. Pierson, Leipzig 1900.

- Martha's children (= Put down your arms. Part II). 1902.

- Franzl and Mirzl. Leipzig 1905.

- The development of the peace movement. Leipzig 1907.

- Eva Siebeck. 1892.

- Marginal glosses on contemporary history. 1892-1900 and 1907-1914.

- Armor and overarming. Berlin 1909.

- Memoirs. Stuttgart 1909.

- Thoughts of humanity. Berlin 1911.

- The barbarization of the air. Berlin 1912.

- Carmen Sylva , Alfred Hermann Fried (ed.): The struggle to avoid the world war. Marginal glosses from two decades on the events before the disaster. 2 volumes Orell Füssli, Zurich 1917 ( digitized from volume 2).

- Liselotte von Reinken (Ed.): Memoirs. C. Schünemann, Bremen 1965. (Reprint: Severus, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-86347-443-0 )

literature

- Irwin Abrams: Bertha von Suttner and the Nobel Peace Prize. In: Journal of Central European Affairs. Volume 22, 1962, pp. 286-307. (see also his lecture of the same name from 2005, [1] (PDF))

- Valentin Belentschikow: Bertha von Suttner and Russia (= comparative studies on the Slavic languages and literatures. ). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 2012, ISBN 978-3-631-63598-8 .

- Claus Bernet : Bertha von Suttner. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 24, Bautz, Nordhausen 2005, ISBN 3-88309-247-9 , Sp. 1435-1471. Progress - Women. Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bertha von Suttner at Harmannsdorf Castle. Lit, Vienna 2007, p. 45 ff.

- Edelgard Biedermann : Not just " Put your arms down" !: Bertha von Suttner. In: Karin Tebben (Ed.): German-speaking women writers of the fin de siecle. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1999, ISBN 3-534-14484-8 .

- Laurie R. Cohen (Ed.): "Precisely because you are a woman ...". Explorations about Bertha von Suttner, the unknown Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Braumüller, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-7003-1522-8 .

- Ilse Kleberger : The vision of peace - Bertha von Suttner. Klopp, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-7817-7112-1 .

- Maria Enichlmair: Adventurer Bertha von Suttner. The unknown Georgia years 1876 to 1885. Ed. Roesner, Maria Enzersdorf 2005, ISBN 3-902300-18-3 .

- Stefan Frankenberger (concept / music): The unknown soldier - In memory of Bertha von Suttner . Mono-Verlag, Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-902727-52-7 .

- Christian Götz : The rebel Bertha von Suttner - messages for our time. Klein & Blechinger, Dortmund 1996, ISBN 3-927658-48-0 .

- Brigitte Hamann : Bertha von Suttner - A life for peace. Piper, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-492-23784-3 .

- Leopold Katscher : Bertha von Suttner, the “enthusiast” for goodness . E. Pierson's Verlag, Dresden 1903.

- Beatrix Kempf : Bertha von Suttner. Writer - politician - pacifist. Heyne, Munich 1987 (first 1964).

- Beatrix Kempf: Bertha von Suttner and the “bourgeois” peace movement. In: Peace - Progress - Women. Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bertha von Suttner at Harmannsdorf Castle. Lit, Vienna 2007, p. 45 ff.

- Ilse Kleberger : The vision of peace - Bertha von Suttner. Klopp, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-7817-7112-1 .

- Beatrix Müller-Kampel (Ed.): "War is murder on command". Bourgeois and anarchist peace concepts. Bertha von Suttner and Pierre Ramus . Grassroots Revolution , Nettersheim 2005, ISBN 3-9806353-7-6 .

- Johann Georg Lughofer, Milan Tvrdík (Ed.): Suttner in context. Interdisciplinary contributions to the work and life of the Nobel Peace Prize laureate (= contributions to recent literary history [third part]. Volume 349). Winter, Heidelberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-8253-6552-3 .

- Simone Peter: Bertha von Suttner (1843–1914). In: Bardo Fassbender , Anne Peters (Eds.): The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2012, pp. 1142-1145 (preview) .

- Peter Sprengel : History of German-Language Literature 1870–1900. From the founding of the empire to the turn of the century. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44104-1 , pp. 51, 210-213 and 218.

- Peter Sprengel: History of German-Language Literature 1900–1918. From the turn of the century to the end of the First World War. Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-52178-9 , pp. 268 and 572.

- Harald Steffahn: Bertha von Suttner. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-499-50604-1 .

- Irene Stratenwerth : Why aren't you doing anything, you young people? In: Charlotte Kerner : Madame Curie and her sisters - women who got the Nobel Prize. Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 1997, ISBN 3-407-80845-3 .

- Marianne Wintersteiner : The Baroness. Bertha von Suttner. A narrative biography. Stieglitz, E. Händle, Mühlacker / Irdning / Styria 1984, ISBN 3-7987-0222-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Bertha von Suttner in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Bertha von Suttner in the German Digital Library

- Entry on Bertha von Suttner in the Austria forum

- Works by Bertha von Suttner at Zeno.org .

- Bertha von Suttner. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Works by Bertha von Suttner in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Bertha von Suttner in the Internet Archive

- Bertha von Suttner in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (English)

- Works by and about Bertha von Suttner at Open Library

- Bertha von Suttner - Biographical. In: Nobelprize.org , last updated in 2014, and information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1905 award ceremony for Bertha von Suttner (English)

- Sibylle Duda: Bertha von Suttner. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations). First published in 1992, updated in 2006 and 2014.

- Jutta Duhm-Heitzmann: June 21, 1914 - Anniversary of the death of Bertha von Suttner WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

Individual evidence

- ^ Editors: Bertha von Suttner Biography . TheFamousPeople. Retrieved January 18, 2018. (English)

- ↑ 1914 / 2014- 1914/2014 - Bertha von Suttner's last traces in the Caucasus are disappearing . In: Tyrolean daily newspaper . 17th June 2014.

- ↑ The personality of Berta v. Suttners .. In: Neue Freie Presse , June 23, 1914, p. 11 (online at ANNO ). .

- ↑ Helen G. Morris-Keitel: (R) Evolution: From noblemen to precious people - Bertha von Suttner's Pathway to Peace. In: Seminar. A Journal of Germanic Studies. Volume 50, 2014, No. 1, pp. 34-50, doi: 10.3138 / SEM.50.1.34 .

- ^ Bertha von Suttner: The next peace congress in Rome. In: Neue Freie Presse, Vienna. September 3, 1891, accessed December 10, 2019 (p. 1).

- ^ Bertha von Suttner: The next peace congress in Rome. In: Neue Freie Presse, Vienna. September 3, 1891, accessed December 10, 2019 (p. 2).

- ↑ Bertha von Suttner: Schach der Qual. In: Manuela Linnemann (Ed.): Brothers, Bestien, Automaten: The animal in occidental thinking. Harald Fischer Verlag, Erlangen 2000, pp. 247-253, here p. 251.

- ^ A b Bertha von Suttner: Schach der Qual. In: Manuela Linnemann (Ed.): Brothers, beasts, automatons: The animal in occidental thinking. Harald Fischer Verlag, Erlangen 2000, pp. 247-253, here p. 252.

- ↑ Bertha von Suttner: Nobel Lecture: The Development of the Peace Movement. April 18, 1906. In: Nobelprize.org , accessed November 21, 2015. See also Bertha von Suttner: Memoirs. Bremen 1965, p. 519.

- ^ Berta von Suttner: Peace in 100 years . In: Arthur Brehmer (Ed.): The world in 100 years . Buntdruck publishing house, Berlin 1908.

- ^ Alfred Hermann Fried : Berta v. Suttner. A sheet of remembrance. In: Neue Freie Presse , June 23, 1914, p. 10 (online at ANNO ). . For the relationship between the two Bernhard Tuider: Alfred Hermann Fried - an Adlatus or Inspirer of Bertha von Suttner? New perspectives on the relationship between two leading figures of the Austrian peace movement. In: Viennese magazine for the history of modern times . Vol. 9, 2009, No. 2, pp. 134-162.

- ^ Bertha von Suttner (1843–1914). In: Gotha.de .

- ^ Suttner, Bertha Freifrau von (1843–1914). In: Nachlassdatenbank.de , accessed on November 21, 2015.

- ↑ Bertha von Suttner. In: Literaturhaus Wien , accessed on November 21, 2015.

- ^ Conversation with Aunt Boulotte (Bertha von Suttner). In: Mediathek.at , accessed on February 7, 2011 (May 23, 1904, Ebenfurth).

- ↑ Article in the CDU newspaper Thüringer Tageblatt , June 22, 1984.

- ↑ For an example of the memory of Suttner in the GDR see Walter Bredendiek : Bertha von Suttner - pioneer for a world without war, voice of humanity in inhuman times. In: Ann-Charlott Settgast (ed.): Risk of a woman. Berlin 1967, pp. 231-246.

- ^ Search for Bertha von Suttner. In: Time Online , How Often Is Your Street There?

- ↑ GA BONN: Named 70 years ago: How Bertha-von-Suttner-Platz got its name. Accessed January 1, 2020 .

- ^ Website of the European high school Bertha-von-Suttner in Berlin-Reinickendorf.

- ^ Bertha von Suttner Realschule in Stuttgart-Freiberg, Mühlhausen district

- ↑ Suttner memorial plaque in Zedlitzgasse. In: Rathauskorrespondenz. April 19, 1963.

- ↑ 2.50 meter high stainless steel sculpture commemorates the peace activist. In: General-Anzeiger . 22nd September 2013.

- ↑ Website of the Bertha von Suttner Foundation.

- ↑ In honor of Bertha von Suttner. In: Google.com. December 10, 2019, accessed December 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Jens Minor: Bertha von Suttner: A nice Google doodle in honor of the Austrian Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In: GoogleWatchBlog. December 10, 2019, accessed December 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs. Edited by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin and Kerstin Wolff . Böhlau, Cologne 2015, p. 308.

- ↑ Jörn Leonhard: Pandora's box. History of the First World War. CH Beck, Munich 2014, p. 74.

- ^ Suppé, Franz von. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online , accessed on June 13, 2014.

- ↑ Franz Zeitelberger: work premiered. In: Niederösterreichische Nachrichten . May 21, 2014.

- ^ Günter Wirth: The Hauser Chronicle. Der Morgen, Berlin 1982, p. 90.

- ^ Bertha von Suttner in the Internet Movie Database , accessed on January 4, 2015.

- ↑ Bertha von Suttner. A bibliography. Giessen 1993/2014 (PDF).

- ↑ Rolf Löchel: God-alienated Culturweiberthum - Johann Georg Lughofer and Milan Tvrdík have published "interdisciplinary contributions to the life and work" of Bertha von Suttner. In: Literaturkritik.de . 5th December 2017.

- ^ Konstantin Kountouroyanis: Review of Suttner in context - interdisciplinary contributions to the work and life of the Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In: Institute for Literary Research Prague . 23 May 2018.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Suttner, Bertha von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Suttner, Bertha Sophia Felicita Freifrau von (full name); Kinsky von Wchinitz and Tettau, Bertha Sophia Felicita Countess (maiden name); B. Oulot (pseudonym); Someone (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian peace activist and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 9, 1843 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prague |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 21, 1914 |

| Place of death | Vienna |