Cowboy money

Kauri money is a historical form of simple money ( primitive money) that was widespread in Africa , East and South Asia and the South Seas as a pre-coinage means of payment or natural money (commodity money made from natural objects) and is still used traditionally and ritually in places today . Consisting of or made from the shells of cowrie shells , cowrie money was the most widespread mussel or snail shell money in terms of space and time ( also known as mollusc money in coinage ). The cowrie shells were mostly drawn on bast threads and traded as money strings, for even larger quantities there were basket-shaped hollow measures in some areas . Kauris circulated in parts of Africa, India , Afghanistan , Southeast Asia , China, and many islands in Melanesia .

In Africa it was almost always and exclusively exchange or trade money . Kauri money was the first universal money and played a major role in national trade. Kauri money existed before metal coins and in some cases it was used in parallel with metal coins. Since transport and trade used to be very easy, the cowrie snails became more valuable the further inland they were transported. The snail shells were mainly collected in the Maldives and around the Gulf of Thailand .

The small, egg-shaped, very stable cowrie shells with their brightly colored shells with a shiny enamel coating were made around 2000 BC. BC, so still in the Bronze Age , used until the late 19th century. They circulated as a forgery-proof international " currency " around half the globe. Strictly speaking, Kauri money was not money in the sense of currency, because there was no government supervision and no banking system for it; Kauri money, however, served as a store of value. At first the cowboy money found distribution in South Asia and Southeast Asia, China and India, later also in East Africa , in Central Africa and in tropical West Africa , as well as in the South Seas. In many regions of Asia and Africa, the cowrie shell was both a commodity and a means of payment.

In the pre-metallic monetary system, cowrie money stood on the border between money and non-money, since cowrie shells were also used as jewelry. Kauri money was a drawn currency (made from animal components), just like fur money or leather money .

After its heyday in China, this pre-coinage currency was also used in India and on the islands of the Indian Ocean as divisional coins , from where merchants brought it to Africa. Because of its relatively low value, kauri money was used as small change . In South Asia the use ended in the 19th century, in West Africa at the beginning of the 20th century.

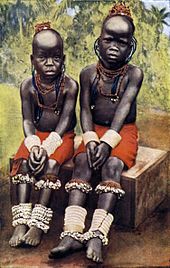

A single Kauri case itself was of little value, which is another reason why large quantities of it were used as currency. In colonial Germany this means of payment was also called " Negro money ". Cowry money was a popular topic in the accounts of explorers and travelers.

The size and weight of the traded cowrie snail species are fairly uniform. The average weight of a cowrie snail is between 0.8 and 3.5 grams. The market value of the cowrie shell was based on mutual agreement and was independent of its size - each cowrie shell had the same monetary value . The exchange rate between the Kauri money and the coins that were often in circulation at the same time fluctuated according to supply and demand. In most cases , cowrie money was not legal tender because there was no legal claim to have to accept cowrie shells as a means of payment.

Cowries

The shell of young cowrie snails has a short, pointed thread (to be seen in the top right of the picture) and a large end turn. In the course of growth, the end turn overgrows the thread, while the growth margin thickens and teeth form on both sides of the narrowed mouth.

Originally the shell ( exoskeleton ) of the historically significant money cowrie shell was used as a means of payment. The money cowrie shell comes from the cowrie shell family , genus Monetaria . The cowrie snails are also known as porcelain snails because their shell resembles light-colored porcelain.

The scientific name of the money cowrie shell is Monetaria moneta (Linnaeus, 1758). An outdated synonym is Cypraea moneta ( Linnaeus , 1758). Other outdated synonyms for the money cowrie snail are money snail and Erosaria moneta.

English names for the ring cowrie shell are money cowrie or money cowry . The French name is Porcelaine monnaie and the Dutch money kauri . In Japan they were called Africa Kiiro-Dakara and in Hawaii Leho palaoa or Leho puna .

Historical names for the money cowrie shell were in the 18th century Guinean coin (French Monnoie de Guinée ), Mohr coin , Cauris or in Dutch Gemeene geele Kauris ("common yellow cowrie").

The generic name Cypraea was derived from the island of Cyprus , where the goddess of love Aphrodite (nickname Kýpris ; Latin Cypria; "Kyprosgeboren") was worshiped as the goddess of fertility (see also below ).

Later the shell of the ring cowrie shell was also used ( Latin Monetaria annulus ; annulus "ring"; Linnaeus 1758); outdated synonyms: Cypraea annulus Linnaeus (1758); Cypraea annularis; Cypraea annulata; Cypraea annulifera . However, the ring cowrie shell was not given the same value as the money cowrie shell.

An outdated synonym for the money cowrie shell is Erosaria annulus . English names for the ring cowrie shell are ring cowrie, golden ring cowry, golden ring cowrie, gold ringer or ring top cowrie . The French name is Porcelaine anneau d'or and the Dutch ring kauri . Historical names for the ring cowrie shell in the 18th century were yellow ring or gold ring and common cowries , French pucelage ou cotique blanc , Dutch slechte cowries .

Cowrie snails are herbivorous or omnivorous sea snails (saltwater snails ) that live on coral sticks and rocks in the warm waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans . Cowrie snails live under rocks and crawl out to eat at night. They can be found in shallow water in the intertidal zone , on stone beaches, on soft bottoms under stones or in seagrass, where they wander around during the day and can be easily collected.

Both types of cowrie shells are similar with their oval shell ; the mouth is narrow, slit-shaped and toothed because of the distended, knotty lip edges; Sawn slot on the underside and flat hump on the top. The shell of the money cowrie shell is egg-shaped, shiny yellowish, porcelain-like and up to 3 cm long. The shell of the ring cowrie shell is lined with gray-bluish and orange-colored; it is up to 3 cm long.

Since the 17th century, when researchers began to systematize nature according to scientific criteria, the cowrie shells were given names according to their economic function. Nigritarum moneta "Money of the Nigritians" was the name given to the species by the English naturalist Martin Lister in 1685. This is the oldest zoological name. The British naturalist James Petiver named the snail Moneta nigretarum in 1702 .

The Swedish taxonomist Carl von Linné classified it in 1758 as Cypraea moneta in his Systema naturae . Due to the establishment of the genus Monetaria in 1863, its scientific name is today Monetaria moneta ( Linnaeus , 1758).

Since there are transitional forms between the money cowrie snail and the ring cowrie snail, it is also discussed whether and to what extent both types of porcelain snail can really be separated from each other.

The range of both species overlaps. The ring cowrie shell occurs on the east African coast to the Red Sea and Iran . The money cowrie shell comes from the Red Sea and Mozambique in the west, along the Persian Gulf , in the Indian Ocean, to Sri Lanka, in the Chinese Sea to Indonesia and the Philippines , in northern Australia , in southern Japan . In the east their distribution area extends to Hawaii , Easter Island and the Galápagos Islands . There are no cowries in the Atlantic.

Cowrie shell

The term “cowrie shell”, which is widely used in popular literature and colloquial , is not biologically correct. Even so, cowrie money is often incorrectly referred to as shell money , even though cowrie snails are not clams , but snails .

There is also real mussel money, but not made from cowrie shells or "cowrie shells". Shell money was used on some South Sea islands until the 20th century.

The shell of the cowrie snail does not look like a typical shell of other snails, since the shell edge of the living animal grows over the shell from both sides. A line forms in the pattern where the edge of the coat meets on the back.

Mollusc money

From a zoological point of view, cowry money is to be assigned to mollusc money. Mollusks ( mollusks ) include both mussels and snails. The term “ snail shell money”, which is occasionally used for cowrie money, is also biologically correct. Another snail shell money widespread in Melanesia was Diwarra (from the land snail Nassa camelius ); it was the customary currency in the Bismarck Archipelago around 1900.

The zoological name mollusks summarizes the animal phylum of the molluscs , whose various species of the genus snails (Gastropoda), mussels (Bivalvia) and burial pods (Scaphopoda) became relevant in monetary history. The shell of snails (especially porcelain snails : cowrie snails ) and the shells of mussels (mother-of-pearl) and grave feet (dentalium) form the material from which the mollusc money was made. The mollusc money usually consists of small, rounded discs that are pulled on strings and rated according to their length. Sometimes the strings of pearls were provided with measuring beads of different colors at regular intervals, which made it easier to measure the length of the money strings concerned.

Names

The Portuguese word buzio (from Latin bucina ) was also adopted in an adapted form in the other European languages spoken on the west coast of Africa. In English, buzio was adapted to booge , probably influenced by the French bouge . Other forms were buji and bousie . From 1700 the English word cowrie gradually took the place of booge .

The name of the cowrie shell is derived from the Indian Hindi word kaurī and was adopted into English as cowrie , Dutch Kowers , coris , bouge , Spanish bucio , cauri or buzio , French porcelaine . With the Arabs they were called kauri , with the Sudanese Kanuri kungena and with the Nigerian Hausa kerdi .

porcelain

European traders called the Kauris porcelains ("little pigs"). The term " porcelain " also goes back to the Italian name for cowrie snails, which are also called porcelain snails. After Marco Polo (allegedly) brought the first Chinese porcelain to Europe, it was believed in 15th century Italy that Chinese porcelain was made from the crushed yellowish-white shells of cowrie shells, which in Italian were called porcellana . This goes back to porcellano (actually "piggy", from Latin porcellus ) for the external sexual organ of the woman, as the shape of the snail shell reminds of it (compare clams : Concha Veneris ).

origin

The cowrie money has its origin on the islands of the Maldives in the Indian Ocean; from there it spread to the entire Asian region, later also to Africa and various South Sea islands. It gained importance in ancient China, where it was used from 1500 BC. It was a recognized reserve currency until 200 AD (see Early Chinese Currency ).

Asia

Kauri money was available in China, India , India , Japan , Indonesia and Oceania .

Maldives

The islands of the Maldives became the main source of the cowrie shell trade. From there they were shipped to India and then transported to the vast areas of China. The cowrie shell was bred in the Maldives, where it served as money, as an object of exchange and as an export product. The further they were transported from the sea, the higher their value.

In the early 14th century, cowrie shells were used as money in the Maldives. Arab traders exported them from there to Africa.

The Arab trader Suleiman al-Tajir made several trips from his hometown of Siraf to China of the Tang Dynasty and to India from the year 850 . His reports are the oldest Arabic reports from China and were written over 400 years before Marco Polo's reports. Al-Tajir visited the port of the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou in 851 , which had trade relations by sea with South Asian countries such as India and Arabia. There he saw the production of porcelain, the Guangzhou mosque, grain houses and how the city government worked. In addition, al-Tajir reported that there was a very beautiful and wealthy queen in the Maldives. After she had used up her treasure trove of cowrie shells, she sent women out to collect large palm fronds from coconut palms . These palm fronds were then laid out in shallow water. Soon thousands of cowrie snails crawled on the leaves and were pulled out of the water with them. They were dried to kill them and then the queen's treasury was replenished with them. This report by Suleiman al-Tajir about the cowries in the Maldives was also confirmed by al-Mas'udi , an Arab historian who lived in Baghdad in the 10th century.

François Pyrard was shipwrecked in the Maldives in 1602 and stayed there for two years. He wrote: “They called them Boly [Kauris] and exported them in infinite quantities. In a year I've seen 30 or 40 ships fully loaded with them only - with no other cargo. Everyone goes to Bengal , because only there is a demand for large quantities at a high price. The people of Bengal use them as common money even though they have gold and silver and other metals in abundance. And it is even stranger that kings and high princes have built houses that are only intended to store these shells there and treat them as part of their treasure. "

Jean (John) Barbot (1655–1712), the general agent of the Compagnie royale d'Afrique in Paris in the 17th century , also reported on the cowrie shell: “The Boejies or Kauris, which the French call bouges, are small, with Milk white skins and usually the size of small olives. They are collected between the shallows and rocks of the Maldives islands. The kauris vary in size, the smallest are barely larger than an ordinary pea, while the largest are as large as an ordinary walnut and elongated like an olive. "

The Maldives and the Lakshadweep Islands 400 km further north (today part of India) supplied the money cowrie shell for most of world trade until the 18th century. In return for the cowries, the Maldives imported rice, among other things. Without this rice, the Maldives would have been difficult to inhabit. The snails were primarily exported to Bengal. European traders then bought them from Indian traders, shipped them to Europe, and then used them to buy slaves in West Africa.

From a historical perspective, the money cowrie shell is the main marine invertebrate in the Maldives. Although the cowrie shell was widespread throughout the Indo-Pacific, the Maldives has always been the center of the lucrative trade in these snails. The reason for this is not only that they were found in abundance there, but also that the Maldives has developed a simple and effective method of collecting them. For this purpose, bundles of coconut palm fronds were laid out in the shallow water of the lagoons , and the cowries then accumulated on them. It is believed that the cowrie shells, which inhabit shallow water, feed on the detritus ( organic matter that breaks down ) that has accumulated on the palm fronds. After a certain time, the bundles of palm fronds were pulled onto the beach, where the cowries died in the hot sun and could then be shaken by the palm fronds. The dead cowrie shells were then buried with their shells in pits, the meat rotted - also due to the action of invertebrate saprobionts (detritivores) - and what remained were the clean, empty shells of the cowrie shells, which only had to be collected. Almost all of the early travelers who wrote about the Maldives mentioned the importance of exporting the cowrie shells.

The traveler Ibn Battuta , who had visited the Maldives in 1343/44 and 1346, also described the Maldives as the center of the kauri trade. By the middle of the 14th century, when Ibn Battuta visited the Maldives, the cowrie money had expanded its range to West Africa . Ibn Battuta reported on its use in Mali . They were probably imported through Cairo . Whole shiploads of these snails were shipped from the Maldives until, in the mid-19th century, the Maldivian cowrie snails lost their importance and were replaced by larger specimens from Zanzibar and Mozambique .

Today the once so important trade in cowrie shells no longer exists, only very small quantities of cowrie shells are exported from the Maldives. However, the historical significance of this animal is remembered in the Maldives, for example with a pair of cowrie shells on every Maldives banknote.

From the 9th to the 19th century at the latest, the rulers of the Maldives controlled the supply of cowrie shells. They were exported from the Maldives to Bengal , Southeast Asia and the Arabian Peninsula .

A contract signed in 1515 allowed Portuguese traders to ship 24 tons of cowrie shells from the Maldives to West Africa every year. After that, the Portuguese dominated the kauri trade until almost the 16th century.

After the Europeans had reached the Maldives and the Portuguese occupied the islands of the Maldives in 1558, the export of cowrie shells increased significantly. They were taken on board as ballast by Portuguese ships and later also by Dutch and English ships and transported to Europe. There they were filled into sacks and taken to West Africa by ship.

In the early 17th century, the British East India Company began exporting cowrie shells from the Maldives. With the decline of Portuguese power in the Indian Ocean, the British became the main supplier of cowrie shells for the slave trade in the 18th century.

The use of the cowrie shell as money and jewelry prompted the Portuguese to use it as ballast, instead of stones, sand, or rusty iron, which could not be used to make money.

On various atolls of the Maldives, the money cowrie snails grew relatively pure, with only very small admixtures of the less valued ring cowrie snail. The very time-consuming sorting of the two types of snail was no longer necessary. However, later, when the Zanzibar ring cowrie shell competed with the Maldives money cowrie shell, no distinction was generally made between the two. Both species can often be found together in Asia and Africa.

In addition , because of the favorable combination of the correct water temperature and water depth, the Maldives' lagoons grew on average significantly smaller money cowries than elsewhere. This combination of small cowries, their large numbers and the ease with which they could be collected gave the Maldives an incomparable advantage as the main supplier of cowries. Fifty people were able to “harvest” over 50 kg of cowrie snails from the corals and aquatic plants in one day - at low tide. The live cowries were then buried in shallow pits for a few weeks. They were then washed with sea water to remove the dead organic matter and then in a second wash with fresh water to restore their bright color and shine .

China

- antiquity

Cowrie shells, called bèi in China , were the earliest form of money in China. Their use in China is documented by archaeological finds from the Neolithic ( Majiayao culture ; 馬 家窯), the finds are numerous from 2200 BC. The ancient Chinese word pong for neck jewelry made of shells later became the name for a unit of value shell money. The cowboy money was a sensible solution for change. Cowrie shells were only found in the sea, far from China. Cowrie shells were found in graves of that time, sometimes in very large quantities. One of the first written references to cowrie money was given by the Chinese historian Sima Qian , who mentioned that cowrie shells served as a means of payment during the Shang and Zhou dynasties .

They were only used north of the Yangtze River , especially in the north-west and for the Western Chou in the Shaanxi plains - they were not found in the southern provinces in antiquity. The westernmost site before 650 BC. Is Hami . Neolithic imports were most likely made via the Mongolian steppe, from the Persian Gulf . Even during the Yangshao Warm Period (around 8000-3000 BC), the environmental conditions were insufficient for their occurrence in the South China Sea. About the origin of the Kauri found as grave goods in Yunnan before its incorporation into the Han Empire in 69 BC. There is still no clarity.

With the introduction of bronze coins, the use of kauris ceased with the beginning of the early Han dynasty. For the first time 335 BC. Kauris banned because they competed with copper coins. A big problem was that very large amounts of cowries were required for larger transactions. Since the same value was attached to the money cowrie shell ( Monetaria moneta ) and the ring cowrie shell ( M. annulus ), one sometimes made do with specimens of larger species of cowrie, such as B. the tiger cowrie shell, Cypraea tigris and the turtle cowrie ( Chelycypraea testudinaria ), represented a higher value.

- middle Ages

The later uses of the T'ang and Qing dynasties in Yunnan - they were kept there as a means of payment until the end of the 19th century - emerged independently of ancient usage. Marco Polo claimed that the Kauris were imported from India into the Yunnan Province, although an import via inland routes, probably along the major rivers Saluen and Irrawaddy with its tributary Ruili Jiang, appears plausible.

After the kauri currency had become common again in the 10th century - taxes could still be paid in China with kauris up to the 14th century - it was not repealed in China until 1578, under Emperor Wan-li ( Ming dynasty ). The first Chinese paper money was issued around the year 1000 . In 1402 this was abolished in China due to high inflation. In the 14th and 15th centuries, when paper money continued to spread in China, the population stubbornly resorted to cowrie money.

Later in China, cowrie money was replaced by bronze coins. However , they persisted in Yunnan Province until the end of the 19th century.

Just as the cowrie shells were machined to have a hole so they could be threaded, the cash coins customary after the cowries in China also had a hole and were also worn on money strings, which was probably inspired by the centuries-old use of cowrie money.

Imitations of cowrie money

Already during the Shang dynasty there were imitation kauri made of various materials in addition to the real kauri.

Later, however, imitations of the cowrie snail came into use as a successor to cowrie money; they were made of stone, bone, jade , clay, ivory , copper, bronze, silver or bronze covered with gold. Cowries imitated from bones were the first man-made money. Over time, in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256 BC), the cowrie shell was replaced as a means of payment by imitations of the cowrie shell made of bone and metal. Even so, real cowrie shells were still used until the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) and the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) - in parts of Yunnan Province.

Archaeological finds from the early Zhou dynasty (1122–221 BC) provide evidence of such pieces. Whether it is in these imitations only to funeral money (English money burial or burial coins ) acted, is hard to say. Images can only be seen on imitation bronze cowries from Chu state .

Kauris were made between 1100 and 800 BC. Chr. In China in short supply, therefore replicas were made.

The scarcity of cowrie shells led the Chinese to imitate them with other materials : in wood, stone, jade , other semi-precious stones , bones, bronze and even gold or silver. These imitations then led to the ants nose money (or "ants noses" coins; engl. Ant nose money ; Chinese Yi Bi Qian or Pi Ch'ien ) in the Song Dynasty . The “coins” had figures that resembled ants with a human nose. These coins were used as burial money that served as grave goods. During the Warring States Period (475-221. Chr.), The state of Chu ant nose money bronze used (yi bi qian) (also called "ghost face-money" called gui lian qian , English ghostface money ).

From 581 to 221 BC In China there was the ghost face money, bronze kaurin replicas with characters. It became 221 BC. Abolished again by Emperor Qin Shihuangdi .

Later, replicas of kauri appeared in other countries. In Thailand there were imitations of lead kauri . Imitation kauri made of gold were found as grave goods in ancient tombs in Cyprus and made of bronze in Etruscan tombs. Some also see the cowrie shell as a model for the misshapen ancient Greek coins . The Getty Museum has a necklace of cowrie shells reproduced in gold, dating from around 220–100 BC. Was made in the Egyptian-Greek Alexandria .

Already in pre-ancient Cyprus in the 2nd millennium BC The daughters of the rulers wore a belt or an apron on which gold or silver imitations of cowrie shells were sewn - probably as an amulet to protect against sterility.

Characters

→ Main article: Radical 154

During the Shang Dynasty, officials were honored to receive cowries from their superiors. The modern Chinese word for “give” ( 賜 / 赐 , sì ) still has the symbol for “snail shell” ( 貝 / 贝 , bèi ) as a component ; likewise “prosperity” ( 財 / 财 , cái ), “trade” ( 貿 / 贸 , mào ) and “goods” ( 貨 / 货 , huò ) contain the symbol for “snail shell”.

The Chinese character for "money" as well as numerous Chinese characters that have to do with money (valuable, value, moral value, physical value, in combination with other characters, the symbol for kauri / money can mean: wealth, fortune, donate, support , generous, cheap, poor, poverty, tax, thief, corruptible, etc.) contain a radical (basic graphic component of a Chinese character) that represents a stylized cowrie shell. Today's traditional symbol for bèi ("Kauri, money") is 貝 , the short symbol 贝 .

In the earliest form, the archaic Chinese script, which developed into seal script, the character bèi was a rough image of the ventral (belly side, located on the belly) side of the cowrie shell. The character 貝 / 贝 was so important that it was included in the written Chinese language as one of the 214 radicals. Today 84 Chinese characters are based on the 貝 / 贝 .

Ceylon

On Ceylon (from 1972 Sri Lanka ) cowrie money was used until the beginning of the 20th century.

India

The cowboy money spread from China to India, among other places. Cowrie money appeared in India over 2000 years ago. Kauri money became an important currency in India. It was most widespread there in the 4th to 6th centuries AD and remained in circulation until the mid-19th century. In the 17th century, kauris were used as currency throughout India and the Philippines.

Treasure finds in India (especially in Punjab ) testify that cowrie money was still in circulation in pre-Christian times when metal coins were already in use.

In India, cowries were found along with coins. The finds were dated to the 1st century AD.

In India, Bengal and Orissa in particular were large customers for the Maldives' cowries.

The kauri currency was suspended in India in 1872.

Verrier Elwin wrote in 1942 that there are still many old people in India who could remember the use of cowrie money and that cowrie shells were used to pay tax debts.

The association of the cowrie shell with Lakshmi , the Hindu goddess of happiness and beauty, is of economic origin. In ancient times the cowrie shell was probably the only currency in India and in the Indian books of the Hindus the value is often given in cowrie shells.

For southern India, there is no evidence that cowries were used in ordinary purchases and sales, although rice from Malabar (south-west India) was exported to the Maldives in significant quantities and although the Muslim Mophla traders who operated from the Malabar coast did one had a strong share in coastal trade in Bengal and Orissa . The Mophla traders dominated the kauri trade until the first half of the 17th century. Thereafter the cowrie shell was traded directly by Bengali traders. In Bengal and Orissa the importance of cowrie money was very important, as there were no copper coins there. During the period of the Mughal Empire , the cowrie shell remained the means of payment for transactions of lesser value in Bengal, partly because the rulers of the Mughal Empire failed to introduce a system of trimetallism (three different coin systems with three differently valuable metals) in this province . In Bengal the cowrie shells were three to four times higher than in the Maldives. In the 16th century, the Portuguese began shipping cowrie shells to Bengal. Later, the British and especially the British East India Company entered the kauri trade. Some of them shipped the Kauris to Bangalen, others via the port of Chittagong to Europe.

Philippines

In the Philippines, cowrie money was replaced by copper coins around 1800.

Thailand

The kauri currency was no longer recognized in Siam in 1881.

New Guinea

In the Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land (German New Guinea) in 1914, the Reichsmark was considered a valid means of payment, while the traditional Kauri shell money was still in circulation among the indigenous peoples .

In Papua New Guinea , cowrie money was traded into the highlands. Then, between 1930 and 1960, the kauri inflation bubble burst. This period coincides with the influx of Australian workers for the gold mines in Papua New Guinea and the simultaneous increase in imports of the cowrie shell as a means of payment. Especially during the establishment of the Mount Hagen base between 1933 and 1940, up to 10 million cowrie shells were introduced into the highlands of Papua New Guinea. With the cowrie snails, among other things, the labor was paid. The Second World War interrupted the import of cowrie shells, which then increased again sharply.

Oceania

Cowry money is only found sporadically in Oceania , as there was strong competition there from different types of shell money.

Although cowrie shells were found on most of the Pacific islands, they did not embody a standard of value there, as in Asia or Africa, where cowrie shells took the place of money.

On the islands of the Pacific there were different forms of mussel money and snail money.

Azerbaijan

In Azerbaijan , cowrie shells were to be found in their quality as cowry money until the 17th century.

Africa

Cowrie shells were found in the pre-dynastic graves in Egypt (5000 BC) and in the dynastic graves of Egypt (approx. 4000–3200 BC).

Kauri money was available in Africa by the 10th century at the latest, a few centuries before the beginning of the European colonial era in Africa. Before the Kauri money, coins had been in circulation in Africa since the 5th century BC.

For Timbuktu in the Sahara , the use of the shell of cowrie shells as money has been proven as early as the 11th century. Sixteenth-century sailors found cowrie money along the coasts of West and East Africa.

Kauri money has existed in East Africa and Central Africa since 1300 AD .

Arab traders, and later Venetian merchants as well, brought the cowrie shell via the caravan routes to the then large African trading center of Timbuktu , located on the Niger River. There, too, the handy, beautiful shells became a means of payment.

Leo Africanus (490 - approx. 550) reported unminted gold coins in Timbuktu , and that they use certain snails that came from the Kingdom of Persia in matters of little value. 400 of these snails corresponded to the value of one ducat .

A major driving force for the spread of cowrie money in Africa was the development of the Atlantic slave trade , which took off in the 16th century when the sugar cane plantations in America urgently needed a great deal of labor. Portuguese, Dutch and English traders bought the cowrie shells on the coasts of India, transported them with their ships - with detours - to Guinea, where the cowrie shells were sold at a profit. With this money slaves were bought and sold for profit in America (→ Atlantic triangle trade ).

In the Middle Ages, Venice controlled the supply of cowrie shells to North Africa, it monopolized the cowrie trade and was the main supplier until the 15th century.

Because of their shape, cowrie shells were often viewed as symbols of female sexuality in Africa and elsewhere. In Africa, it was a widespread myth associated with the slave trade that cowrie shells feed on killed slaves that were submerged in the water as bait. In Nigeria, Benin and Togo, the living cowrie shells were also said to suck the blood of their prey - the submerged people (" vampire kauris").

As in China, cowries were also placed in the grave of the dead as grave goods as "travel money" in Africa.

East Africa

Cowries were exchanged for gold and ivory by Arab traders along the East African coast in the 9th and 10th centuries, and later by the Europeans until the end of the 19th century.

Arab traders brought the cowrie shell from the East African coast, Sudan, to Upper Guinea and via Mauritania and to the Berbers in the Atlas Mountains .

Cowboy money was widespread in East Africa until well into the 19th century, especially in Zanzibar and Ethiopia .

Seychelles

The cowries were bought cheaply in the Seychelles from the company "O'Swald & Co" and then brought to West Africa via Zanzibar , bypassing the intra-African intermediate trade. For this purpose, a trading post was established in Lagos in 1849 . The owner of the company "O'Swald & Co" was the family of William Henry O'Swald , who had made their fortune in the early days by exporting cowrie shells from Zanzibar to the west coast of Africa.

The company "O'Swald & Co" had started trading activities in Zanzibar, Lagos and Palma. The main office was in Zanzibar. The company's cowrie snail trade was particularly successful. The cowrie shells, which are rare in West Africa, were bought cheaply in the Seychelles, where they were plentiful, and then sold at great profit to African middlemen who were involved in the slave trade . At that time, the port of Zanzibar was the main hub for slaves in East Africa.

Cowries also played a role in the trade, especially in linen, between Zanzibar and Hamburg. Export goods from Hamburg to Zanzibar were manufactured goods and spirits, later also coal and steamships for the Sultan. In return, spices, palm kernels, rubber and hides were shipped to Hamburg.

Zanzibar

Zanzibar has long been the main trading center for cowrie shells.

After the money cowrie snail became rare because of the high level of exploitation in its natural distribution areas, the cowrie money trade shifted to the extraction of the very similar ring cowrie snail. The ring cowrie shell was "produced" in huge quantities on the coast of Zanzibar.

From 1844 onwards, the Germans and French also exported the ring cowrie snail from Zanzibar.

Uganda

Before the introduction of cowrie money , the Baganda in Uganda had blue pearls - called nsinda . One pearl has been equated to the value of 100 cowries. Even before the pearls there were small ivory discs - called singa . One slice was also equated to the value of 100 cowries. During the reign of Ssemakookiro Nabbunga Wasajja, 27th King of Buganda (1797–1814), goods such as dark blue cotton clothing, copper wire and cowrie shells reached the Buganda hinterland from the East African coast.

The indigenous people in Uganda were allowed to pay their taxes in kauris under colonial rule. From March 31, 1901, however, cowries were no longer accepted by the British colonial powers for paying taxes. The exchange rate at that time was one rupee for 800 kauris. After it became known on July 8, 1901 that whole boatloads of cowrie shells from German East Africa (today mainly Tanzania ) were on their way to Uganda, all further imports of cowrie shells to Uganda were prohibited. Nevertheless, the cowboy money was only slowly being displaced. Kauri money did not disappear completely until 1909, it was used especially for retail trade, parallel to the Indian rupee , which had come to Uganda via Kenya, and later the silver rupee of the Imperial British East Africa Company was added.

The total value of more circulating cowries was the equivalent of 20,000 pounds sterling appreciated.

Sudan

Kauris were used as money throughout most of Sudan . Because of the inflation of the cowrie money , where the cowrie money was once highly valued, the cost of transport exceeded the value of the cowrie shell at some point. The slaves that the cowrie shells had to transport over the very long distances in Sudan were ultimately more expensive to maintain than the value of the cargo transported.

The peoples west of the upper Nile ( A'ali an-Nil in Sudan) often wore cowrie jewelry. Until 1860 there was a lively trade in kauri from Khartoum to the upper Nile (A'ali an-Nil) and Bahr al-Ghazal .

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia , cowries were still in use for a very long time in remote parts of the country.

Central Africa

Missionaries also introduced cowrie money in the Congo Basin.

West Africa

The use of cowrie money in some areas of West Africa dates back to at least the 11th century. When the Arabs invaded Africa as slave traders, they brought the kauri with them from East Africa. In the 19th century the use of cowrie money in the slave trade decreased again, instead the cowrie money was used more and more in the trade in palm oil .

In West Africa, cowrie shells only circulated in a limited area: the Niger River basin . The coast of Upper Guinea and the area to the north of it were excluded from this , although many cowries have their natural habitat on the coast of Gambia . The cowrie shell was imported to West Africa from the Maldives via Morocco and, to a lesser extent, via East Africa.

But although the flow of cowrie shells to West Africa increased, cowrie money retained its value as it encountered a rapidly expanding trade. Until the final collapse of payments with cowrie money in West Africa at the end of the 19th century, there were meanwhile periods in which cowrie money was rejected.

The use of cowrie money in West Africa began between 1290 and 1352. Gold and metal coins had been in use in this region long before that. Polanyi (1966) sees the introduction of the kauri currency as an instrument of tax collection. Local reports also tell that cowrie money was an invention of the state. For example, in the markets of the Kingdom of Dahomey, the king forced the introduction of cowrie money, and in Bornu in 1840 cowrie money was introduced as a tax on the initiative of the state.

Duarte Pacheco Pereira wrote in his book Esmeraldo De Situ Orbis in 1505 : “The negroes of these islands take small mussels ... which they call 'zinbos'. They are used as money in the country of Mani-Congo . In Benin they use shells they call 'iguou' ... they use them to buy all things and whoever has the most of them is the richest. "

After 1500 the English and Dutch began to import the money cowrie snail from the Maldives by sea to Upper Guinea , from 1844 the Germans and French also imported the ring cowrie snail from Zanzibar.

From 1971 to 1986 the Cauri was the subunit of the Syli in Guinea . The Syli was divided into 100 Cauri. The name of the Cauri was derived from the Kauri money. The front of the 50 Cauri coin was depicted as a cowrie shell.

It is controversial whether cowrie money was officially established as state money in West Africa or whether it spread out of control. In any case, the expansion limits of the cowrie money in West Africa looked as if they had been drawn by an administrative authority.

In West Africa the cowries were not available in unlimited quantities. They did not have their natural habitat there and the state prohibited the free importation of shipments of cowrie shells.

Kauri money was already in use in large parts of West Africa more than a century before the Atlantic slave trade of the Europeans. However, the increase in the slave trade in the 18th century was a major reason why the import of kauris reached record levels over the same period.

The Dutch dominated the kauri trade until 1750, after which the Dutch kauri trade declined until 1796 and was discontinued by them because the coalition wars ruined the Dutch trading activities. The British then controlled the kauri trade until 1807, until the slave trade on British ships was banned in 1807 ( abolitionism ). After that, the kauri trade (from India to Europe and from Europe to West Africa) temporarily collapsed , until the demand for cowrie snails in return rose sharply due to the increase in palm oil exports from West Africa. Palm oil was used in the rapidly growing European industry during the founding period, among other things, as a basis for lubricants . Between 1700 and 1790, 11,436 tons of cowrie shells were shipped from the Dutch and British to West Africa, which corresponds to 10 billion cowrie shells. The kauri trade reached its peak around 1840-1870. In 1840 the British exported 205 tons of kauri to West Africa; In 1845 the absolute peak was reached with 569 tons. Between 1851 and 1869, five German and French companies shipped a total of 35,000 tons of cowries to West Africa. Thereafter, the dramatically falling kauri prices made the kauri trade unattractive, so it was discontinued. From 1851 the share of the money cowrie shell from the Maldives in the cowrie trade fell in favor of the somewhat larger ring cowrie shell from Zanzibar. The Zanzibar ring cowrie brought traders a 1000 percent profit compared to 100 percent profit from trading the Maldives money cowrie.

The inflation caused by the importation of thousands of tons to West Africa and the transport costs of the cowrie shell, which was becoming worthless and worthless, made the cowrie change, which was previously only "change", impractical.

The kauri currency was introduced in the Bornu Empire (today Nigeria) in 1845.

Guinea

In the middle of the 19th century, French and Hamburg merchants began trading the ring cowrie shell (Monetaria annulus) in Guinea with great success.

Ghana

Originally, pearls, iron sticks, brass and cowrie shells belonged to the currency in Ghana. But after the 17th century these were replaced by the more valuable gold dust as a means of payment. In 1899 the use of gold dust as a means of payment was banned by the British for abuse.

Ghana had other means of payment that were used as primitive money at various times in the 17th century, such as gold dust, slaves, and various forms of iron currency.

The name Cedi , Ghana's official currency since 1965, is derived from the Akan word for Kauri - "sedie".

The import of cowrie money into the Ashanti Empire was banned in order to prevent competition with the gold dust currency.

Europe

Even if in small quantities, the cowrie money also reached Central Asia and even Europe.

According to other authors, the monetary function of the cowrie shells in Europe is doubted and they are only granted a decorative function in Europe and Central Asia.

Some species of cowrie shells such as Cypraea tigris (tiger kauri) and Cypraea pantherina (panther kauri) came to Europe in large numbers during the Roman Empire and in the early Middle Ages, where they were worn by women as amulets and, after death, also ended up in the graves as gifts.

The cowrie shells did not reach West Africa directly from the Maldives, and later also Zanzibar, but via a detour via Europe. This only apparent detour was due to the routes of the sailing ships of the time. Because of the prevailing winds, the ships sailed far out into the West Atlantic on their return voyage after circumnavigating the Cape of Good Hope (the Suez Canal was only opened in 1869) . Calling at the West African coast was not very practical in terms of sailing technology. That is why the cowrie shells were brought to the markets in Europe and only shipped from there to West Africa. The price of cowries in Europe indirectly determined the value of a slave who was then shipped across the Atlantic to America.

Important European cities for the international kauri trade in the 17th and 18th centuries were London, Lisbon , Hamburg and Amsterdam. Amsterdam had the largest kauri market. The main supplier was the Dutch East India Company . Over time, the Dutch had wrested control of the European kauri trade from the Portuguese. The main buyers of the cowrie shell on the European market were the British Royal African Company and private merchants who were involved in the African trade. The kauris were transported by land through the Sahara or by sea to West Africa, where they were traded for slaves and palm oil.

In 1873 a ship ran aground in the fog off the coast of Cumberland , on its way to Liverpool and carrying 600 bales of money kauris. After that, the money kauris washed up on the British coast for years, so that some believed that the kauris were native to the area.

The English verb to shell out in the sense of generously distribute or pay , also for sheet metal, shell out , wages , is derived from the monetary function of cowries and other forms of mollusc money and shell money.

Russia

In the 12th and 14th centuries were in Kievan Rus cowries as money floating around, under the name Uschowka (Russian ужовка "little grass snake"), Schukowina (russ. Жуковина ) Schwernowka (russ. Жерновка ) or Smeinnaja golowka ( змеинная головка " Snakehead ").

In the north-west of the Russian territories, kauris replaced money during the coinless times from the 12th to 14th centuries. They were found in archaeological excavations as burial money in the area of Veliky Novgorod and Pskov , and depot finds of cowries are known in the region.

In addition to cowboy money, glass beads were also used for small amounts of value, which can also be found in deposits. Silver bars were used to pay for larger values.

In north-eastern Europe and also in Russia, money kauris were sometimes found in hoards together with Arabic coins and western European coins.

America

Cowrie shells have been found in mounds (Indian burial mounds ) and early burial sites in North America. Cowrie shells were also a sacred symbol among the Anishinabe Indians and the Menominee people (west of the Great Lakes ) and were also used in initiation ceremonies.

The Hudson's Bay Company traded cowries with the Cree and other Indians before the time of Lewis and Clark (1806). Cowrie shells, which were found in a mound near Peterborough, Ontario, probably came from this barter . Five money cowrie shells were found in a mound in Alabama that was probably built before Europeans came to the region. It is believed that the first Spaniards who came to America - perhaps even with Christopher Columbus' expedition - carried the money kauris with them as barter goods. Columbus does not mention cowries in his diaries. Since he originally set out on his expedition to India, it cannot be ruled out that, knowing the kauris traded there, he also took them with him as a means of payment.

European settlers and traders brought the cowrie shells from the Indo-Pacific, both Monetaria moneta and Monetaria annulus , to North America, where they were readily accepted in barter by the indigenous peoples. However, according to other sources, cowrie shells were never used as money in the US , at least there is no evidence of this. However, another snail played a major role : wampum belts made from the Venus buccinum snail gradually became a means of exchange and payment for the Indians.

Advantages and disadvantages of the cowboy money

Money must be durable, it must be easy to carry ( stone money, for example, is almost impossible to carry), it must be divisible and it must be difficult to forge .

advantages

These criteria were best met by precious metals . But the cowrie shell also met these criteria and, because of its beautiful appearance with the white porcelain sheen, could also be used as decoration or for decorative purposes (also for amulets ), for prophecies or as a game piece.

The advantages of cowrie money were that the shell of the cowrie snail is very durable. It almost never breaks and can therefore be passed on or inherited over several generations. It can be poured, shoveled, bagged and stored in large piles without breaking. Cowrie snails are light, small and handy and almost always the same size.

Because of their relatively high weight per unit of value, cowrie shells cannot be lost as easily through theft as is the case with paper money or gold coins.

Another advantage of the cowboy money was that there was only a limited source of supply, the Maldives, which was also far from Africa or China.

The advantage of the cowrie shells over metal coins was that it was almost impossible to forge them, even then the production costs for a forgery would have been higher than the original cowrie shells, because cowries were used especially as "change" for shops of lower value. Only after the invention of porcelain in Europe would it theoretically have been possible to counterfeit porcelain snails.

Another advantage of the cowrie money was its large distribution area over Asia and Africa. The cowrie money was accepted across national borders, a currency exchange was not necessary, only the value of the cowries varied from country to country.

disadvantage

The disadvantage of the cowrie snail is the low exchange value per mass fraction. Because of their weight, cowrie shells were only really useful when it came to small amounts. For valuable things you had to pay thousands or tens of thousands of kauris, which beforehand had to be somehow counted. A good snail counter could count 250,000 to 300,000 snails in one day. The amount of cowrie money could not only be determined by counting, but also by measuring volume or weighing (880 cowries per kilogram).

Because of the laborious counting and heavy weight, cowries were not very convenient money. Therefore, especially in Africa, cowry money was mostly only in circulation as small change that existed in parallel with another currency - with gold dust also being used as "money" for smaller values . Kauri money only existed temporarily as the exclusive currency in smaller areas.

Except as jewelry or game pieces, cowries had no real use value. In contrast to precious metals, the cowrie shell is also not divisible.

A fundamental disadvantage of primitive money, which also includes cowry money, is that it can be produced and put into circulation by many producers. The scarcity of the Kauri money was ensured by their expensive transport over long distances. However, once transportation became more effective, cowrie shells became oversupplied, leading to inflation.

With the cowboy money there was no control over the money supply . The growth of the money supply was simply left to nature in the case of cowrie money .

Another disadvantage of cowrie money was the time-consuming counting of cowrie snails ( cowrie arithmetic ). There were two common methods for doing this: on the one hand, the cowries were counted individually in groups of a certain size, and on the other hand, they were strung on strings in a certain number, which differed depending on the region. In Cameroon, for example, 100 cowries per line. If cowrie shells were ground flat on one side, they got a hole there and could easily be threaded, transported and counted in large numbers on strings.

The West African people of the Dagaare counted cowries in groups of five without a string , which was also the smallest unit of value used. Four groups of five were combined into a group of 20. Five groups of 20 to form a group of 100 and ten groups of 100 to form a group of 1000.

In the 17th century, the standard denomination in Bengal was 12,000 kauris wrapped in a leaf of the coconut palm , their value was around 1.5 rupees .

The Igbo people in Nigeria counted their cowries in groups of six and threaded ten groups of six on a string. In the Maldives, cowrie snails were not counted individually, but measured with a spatial measure.

value

The market value of the Kauri money fluctuated depending on the place and time, on supply and demand , but was also seasonal. Over the years it decreased faster and faster. Likewise, the value of cowrie money increased with distance from the sea.

In the early days of cowrie money, this fact brought astonishing profits. Arab traders in the Maldives bought cowries for one gold dinar each and brought them to Nigeria , where they fetched one gold dinar for one thousand cowries - a thousand times the purchase price.

There was a time when you could buy a woman for two cowries in Uganda, but because of the importation of large quantities of cowries, the price for one woman rose to 10,000 cowries. When the French and English became aware of the enormous trade profits from the sale of cowrie shells, they also devoted themselves to the trade in cowrie shells and also exchanged cowrie shells for slaves, which they then sold to America.

A slave on the coast of Cameroon was rated 60 to 70 kauris in 1624 . On the lower Guinea coast (today between the Ivory Coast and Nigeria) a slave was valued at 80 pounds of cowries, fourteen iron rods or 60 pounds of guinea cloth in 1679. Up to 50,000 cowries were required for a slave on the West African Guinea coast in 1725. In 1794, 500 slaves were sold in West Africa for 120 quintals of cowries.

Around 1875, Arab traders exported 8 million cowrie shells worth 51,000 pounds sterling annually from Ras Hafun in the Horn of Africa to the west coast of Africa . This trade then almost came to a standstill.

For British India around 1830 the (day-dependent) conversion ratio was 1 anna (1/16 rupee) = 5 puns, 1 puns = 20 gundas, 1 gunda = 4 kauri. So 400 kauri per Anna. In Bastar , central India , the conversion rate was 240 Kauri = 1 Dogani in 1862; 10 dogani = 1 rupee .

A cowrie shell in Sudan in 1850 was worth a handful of beans; For 8 kauri you got an egg, for 100 kauri you got a laying hen, for 1000 kauri you got a sheep, for 3200 kauri you got a Maria Theresa thaler and for 6000 to 7000 kauri you got an ox.

In a Dutch report from 1864 about a collection in Abeokuta , today a major city in Nigeria , the collection result of 246.55 guilders is broken down by currency . In addition to English, French, American and Dutch coins, 222,000 kauris worth 83.25 guilders were donated to "Negro money", "which had to be carried away by eleven strong men."

The British-American African explorer Henry Morton Stanley was able to cover the daily diet of a porter with six cowries on his famous journey through Africa around 1870, one chicken for three cowries and 10 corn cobs for two cowries.

On the Gold Coast, 16,000 kauris were worth £ 1 in 1859 . To count the sum of £ 2,500 in cowries (40 million cowries), 80 people were employed for a full day.

In Uganda, during the reign of Ssuuna II. Migeekyamye Kalema, the 30th King of Buganda (around 1832–1857), a cow could be bought for 2500 kauris, five goats corresponded to the value of one cow.

In the kingdom of Dahomey , which exclusively used cowrie money as currency, the exchange rate was a constant 32,000 cowries for 1 ounce of gold (28.3 grams; corresponding to 1130 cowries = 1 gram of gold). In the kingdom of Dahomey, which was conquered by French colonial troops until 1894 and then belonged to French West Africa , tax debts could be paid in 1907 with 1 sack of 20,000 cowries per 7 francs.

In the second half of the 19th century in Lagos, Nigeria, six “old” pennies corresponded to 2,000 cowries.

4000 Kauris were often referred to as a Kabeß (English cabess or trade cabess ). The Europeans equated 4 Kabeß to half an ounce of gold (around 14 grams; corresponding to 1140 Kauris = 1 gram of gold).

In 1870 a slave could be bought in West Africa for 40,000 to 50,000 cowries. By 1760 the price of a slave rose to the equivalent of 80,000 cowries and in 1770 to 160,000 to 176,000 cowries. Since 176,000 cowries weighed about 200 kilos, eight porters were needed to carry the purchase price for a slave. However, slaves were not exclusively, but only partially paid with cowries. The rest was paid for in other goods, the value of which was calculated in cowrie shells. Kauris were usually used to pay half of the purchase price, and in the 18th century only 30 percent or less of the purchase price was usually paid in kauris. The sole predominance of cowrie money was largely limited to the so-called slave coast .

In Idda (Nigeria) an additional "coin" with an even lower value was created with the peanut: 1 cowrie snail corresponded to the value of 4 to 5 peanuts.

Meyer's Konversationslexikon stated the value for 100 kauri in Asian Siam as 2.6 to 4 pfennigs around 1890 .

In 1896 in Togo, Africa, 4,000 kauris were worth 1 mark . In 1880 in inland Tanzania 4,000 to 5,000 cowries were worth 1 Maria Theresa thaler . Around 1900, 30,000 to 60,000 cowries in the Congo were equivalent to the value of a male slave . In 1924 in New Guinea you got a little pig for 5 cowries.

Among the Baganda people in East Africa, a chicken cost 25 cowries, a goat 500, a cow 2500 and a slave 20,000 to 50,000 cowries.

In India, larger transactions were also made with cowrie money, for example the purchase of a house could be paid for with millions of cowries.

Decline in value and end of the Kauri money

The value of the shells of cowrie shells fell as a result of inflation. Around 75 billion cowrie shells have been imported into Africa since 1800.

Asia

In South Asia the use of cowrie money ended in the 19th century, in West Africa at the beginning of the 20th century.

Africa

The Maldives' cowrie shells were replaced by the cheaper ones from Zanzibar, which were being shipped to Africa in increasing numbers. As a result of the possession of the coasts of Africa by European states, the cowrie money has been pushed back more and more into the interior of Africa.

With the arrival of the Europeans, there was an oversupply of cowries. By 1850 the cowrie shells were so numerous and cheap that it threatened trade. Counting cowry money, for example 500,000 cowries, became more and more time-consuming. Cowrie snails were packed in bags of 20,000 pieces for the wholesale trade. But for the retail trade, the cowries had to be counted individually. To do this, they were counted in groups of five and then piles of 200 or 1000 were formed.

According to traders' records, over 75 billion cowrie shells were transported to West Africa in the 19th century alone, with a total weight of 115,000 tons. The Dutch alone brought a total of 4.7 billion cowrie shells to Africa from 1660 onwards. The constant influx of cowrie shells into West Africa led to their decline in value and ultimately to hyperinflation .

In the 18th century, kauri imports into Africa averaged 110 tons per year. Due to the many years of mass supply from African countries, the market was overcrowded with cowries.

During the 19th century, the increased use of metal coins led to a relatively rapid decline in the kauri trade. After the Kauri money, the currencies of the colonial powers arrived along the rivers very quickly in inland Africa and prevailed there.

With the appearance of the European colonial powers, cowboy money disappeared more and more, but often retained its importance as small change. Even so, they were still in use in remote regions of West Africa for a few more decades. Kauri money almost completely disappeared, but reappeared during the Great Depression from 1929.

According to Yengoyan, it was not the oversupply of cowrie shells that was responsible for the decline in the value of cowrie money, but the falling demand for them. The colonial powers had implemented their own currency as the new rulers, the resistance of the population, who had invested their fortune in cowboy money, lasted for a while, but ultimately the new currency took up more and more space in trade and displaced the demand for it traditional cowboy money. In India, for example, the British colonial power no longer accepted payment in cowrie shells. Cowrie shells were not only the modest change of the masses, as is sometimes shown. There were great fortunes in cowboy money among the big landowners, moneylenders, slave traders and merchants, all of whom were vehemently opposed to the new legal currency of the colonial powers.

From 1901 onwards, cowries were no longer allowed to be used for tax payments in Africa and in 1923 cowries were banned as a means of payment by the colonial governments in Africa. According to other sources, the bans were issued by the colonial governments between 1904 and 1932.

Occasionally, cowry money was used later in markets in remote areas that were beyond currency control. From 1955 there was no more cowrie money in Africa.

Environmental degradation

As early as 1875, the destruction of the environment by collecting cowrie shells was reported: "By collecting all the cowrie shells, they ruined the corals."

Non-monetary use

Jewelry and game pieces

Cowrie shells served not only as a means of payment but also as jewelry and were processed into jewelry or other handicrafts. Cowrie shells were used as ornaments along with other valuable materials such as pearls .

In traditional African cultures, cowries had a religious significance. In Africa the cowrie shell was seen in connection with its symbolic character for fertility (see above ). Cowrie shells worn around the neck should facilitate conception and childbirth . Cowrie snails were worn as a fertility amulet to protect against sterility .

Cowries were a symbol of femininity , fertility and childbirth because of their shape , and a symbol of wealth and power because of their importance as money .

In Southeast Asia, South India and East Africa, cowries were also used as tokens (stakes, tokens ) in games of chance and as game pieces in various Mancala variants, including z. B. Bao La Kiswahili and Congkak . Likewise, cowries were in gambling as a game cube used.

Cowrie shells were also used for stick maps to indicate the location of islands.

Grave goods

Cowries were also used as grave goods : among others in China, Africa and Europe.

Cowrie shells were used as grave goods in prehistoric Latvia and Anglo-Saxon England, but these were not always the money cowry and the ring cowry. The American Indians also knew the cowries before the arrival of the Europeans.

To what extent the grave goods of cowries had the function of money, so the function of funeral money (English burial money or burial coins ) or had "travel money", can be hard to tell security. The function of these grave goods may also have differed from culture to culture.

Example: Dagaare

For example, among the West African people of the Dagaare (Dagaaba) in Ghana , the non-monetary use of the cowries ( libipilaa ) can be divided into three categories: jewelry, commercial purposes and for spiritual and religious purposes.

From an economic point of view, the Kauris are used by the Dagaare for their cultural purposes as barter goods and not as money. The need for kauris for their cultural and ethnic purposes makes the kauris a useful commodity, but not money.

For spiritual / religious purposes, cowries can serve as the embodiment of traditional shrines or gods, or as medicine containers. They are also used for divination and medical diagnosis, and to treat and prevent diseases. Kauris can also represent part of the paraphernalia (in ritual magic, the tools and objects required for a magical act) that are required for a healing process.

The kauris play a role in funeral ceremonies, and they are also part of the “reward” for the xylophone players and drummers at the funeral; The owners of these musical instruments, who lend their instruments for funerals, also receive kauris. So it is a kind of “ritual payment” with cowries.

The taboo shell money of the Tolai people in New Guinea has similar cultic, religious and spiritual meanings, also for funerals .

Bride price

It is disputed whether the Dagaare's wedding gift or " bride price " (called Lobola in southern Africa ), which is given by the groom to the bride's family in the form of cowrie shells , is a gift of goods or a gift of money, i.e. whether the The cowries handed over represent a purchase price or a payment to the family or not. Some authors doubt that paying the bride price with cowries is a purely financial transaction.

The amount of kauris to be given as a wedding gift is a fixed number. Their number does not vary over time or with economic conditions like a normal commercial transaction. In addition, cowries are only one component of the Dagaaba wedding gift. Attempts to replace the kaurian portion of the wedding gift with cedi (the Ghanaian currency) have not been successful in the past.

Wedding favors are the outward sign of a serious relationship between the two families involved. In the eyes of the two families, they bind the man and the woman together. The wedding gift is a symbol of the marriage covenant and seals the marriage. This wedding gift is not to be seen as a payment (purchase price) for the woman, but an expression of the man's respect for the woman's parents.

African terms for the practice of wedding favors are mostly different from the words used to refer to buying or selling something in the market.

Kauri money in older reference books

Meyers Konversations-Lexikon

The Meyers Konversations-Lexikon wrote in 1885 on the keyword Kauri:

“Kauri (snake's head, otter's head, Cypraea moneta L.), a yellowish-white porcelain snail 1-2.5 cm in size (see below ). It is found in large quantities on the Maldivian islands and is exported to Bengal and Siam , but preferably to Africa and England (for African trade). It has been used as a coin by many peoples since ancient times. Cowries have been found in the facial urns of Pomerania , in Sweden, and between Anglo-Saxon antiquities in England; they are still used here and in Upper Egypt to adorn leather goods, and among the West Asian peoples of the Russian Empire the women adorn themselves with cowries. In the 17th century they were still used as money in India and the Philippines , and in Siam today (100 K. = 2 2/3 - 4 pfennigs ). The cowrie money is most widespread in Africa; it goes through most of the Sudan and is also used on the coasts; Zanzibar is the main staging area for the kauri trade. "

Brehm's animal life

Brehms Thierleben wrote about the cowrie shell in 1887:

“It occurs in great abundance on the Maldivian Islands, where, according to older information, it is collected twice a month, three days after the new moon and three days after the full moon . It should probably also be available on the other days of the month. From there it is shipped partly to Bengal and Siam , but preferably to Africa. The main staging area for the African cauri trade is Zanzibar . For millennia, large caravans have been going inwards from the east coast of Africa with this article, which is money and commodity. Whole shiploads, in turn, are picked up by European ships from Zanzibar and exchanged on the west coast for the local products, gold dust, ivory and palm oil. ... Their worth is of course subject to the course and depends on the supply and the distance. Usually hundreds of them are strung on strings to shorten the payment business. In some places, however, this is not the fashion and the thousands have to be counted out individually. "

Schneider (page 121) contradicts the assertion that "from the east coast (!) Of Africa [...] for millennia large caravans with this article, which is money and commodity, [have]" contradicted and points out "rather that first and for a long time the main movement of the cowries in Africa in Sudan and in the Congo ran from west to east. "

Kaurigeld in the Russian encyclopedia Brockhaus-Efron

The Russian encyclopedic dictionary Brockhaus-Efron writes in the edition 1890–1907 under the keyword Kauri :

“About 30,000 to 40,000 cowrie snails weighed 100 kilograms. On the slave coast you can see the cowboy money in every grocery store: 40 pieces on a string form a chain or 'snur', 50 chains form a head, 10 heads form a sack. On the Niger River , 800 of these mussels are worth around three francs . Kauris were sometimes used as money in China and Siam ; in Siam they were called bia . In the Siamese currency, baht or tical, one baht was about 6400 cowries (bia), but the cowries had no fixed value. "

See also

- Primitive money (overview of pre-coinage means of payment)

literature

- Wolfgang Bertsch: The Use of Maldivian Cowries as Money According to an 18th Century Portuguese Dictionary on World Currencies . Newsletter No. 165, Oriental Numismatic Society, Fall 2000, pp. 16-19.

- Anirban Biswas: Money and Markets From Pre-colonial to Colonial India. Aakar Books, New Delhi 2007, ISBN 978-81-89833-20-6 , pp. 143–162: Chapter 6 The Characteristics, Circulation and Decline of the Cowrie Currency (English; page views in the Google book search).

- Peter Hofrichter: Kauri cultural history. 25 years of the Hanseatic Coin Guild 1969–1994. Hamburg 1994, pp. 127-222.

- Jan Hogendorn, Marion Johnson: The Shell Money of the Slave Trade (= African Studies Series. Volume 49). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-54110-7 (English-language standard work on the history of the cowrie money; reading sample in the Google book search; original: 1986).

- Marion Johnson: The Cowrie Currencies of West Africa Part I. In: The Journal of African History. Volume 11, Cambridge University Press, 1970, pp. 17-49 (English).

- Marion Johnson: The Cowrie Currencies of West Africa Part II. In: The Journal of African History. Volume 11, Cambridge University Press, 1970, pp. 331-353.

- Paul Lunde: The Seas of Sindbad. In: Saudi Aramco World. July 2005, pp. 20–29, here pp. 27–29: Of Cowry Shells and Coir (English; online at saudiaramcoworld.com; the author is a British historian and Arabist).

- Andrew Ngai Ngong: The Importance of Cowries and Kolanuts in the Western Grasslands of Cameroon. Autre institution internationale, 1990 (English).

- Charles J. Opitz: Cowrie Shells. First Impressions Printing, Ocala 1992 (English).

- Alice Hingston Quiggin: A Survey of Primitive Money, the Beginnings of Currency. Emphasis. AMS, New York 1979, ISBN 0-404-15964-8 (English; original from 1949 online in the Internet Archive ).

- Yu-Ch 'Uan Wang: Early Chinese Coinage. Sanford J. Durst 1980, ISBN 0-404-15964-8 (English).

- Berliner Zeitung of July 18, 2009, publisher supplement p. 13.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Snake's head: The Russian name for the cowries, which were known in Kievan Rus in the 12th to 14th centuries , has a connection with snakes: Uschowka ( ужовка "small grass snake") and Smeinnaja golowka ( змеинная головка "snake's head").

- ↑ In the time around full moon and new moon the tides reach their maximum value.

- ↑ 40 pieces = 1 chain or cord ; 50 chains = 1 head; 10 heads = 1 sack: 40 × 50 × 10 = 20,000 pieces.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Alice Hingston Quiggin: A Survey of Primitive Money, the Beginnings of Currency. Methuen, London 1949, pp. ?? ( online in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ A b c d e f Wilhelm Gerloff: The emergence of money and the beginnings of the monetary system (= Frankfurt scientific contributions. Volume 1). 3rd, revised edition. University of Frankfurt, Frankfurt 1947, p. 105 ( side view in the Google book search).

- ^ Roderich Ptak: The maritime silk road. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-56189-4 , p. 98 ( side view in the Google book search).

- ↑ a b c René Sedillot: Shells, coins and paper. The story of money. Frankfurt / New York 1992, ISBN 3-593-34707-5 , p. 42.

- ↑ a b c Fischhaus Zepkow: Family Cypraeidae - porcelain snails. In: Snails & Mussels. Own website, 2014, accessed on August 15, 2014 (detailed descriptions of the subspecies).

- ↑ World Register of Marine Species : Monetaria moneta (Linnaeus, 1758).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i John Reader: Africa: A Biography of the Continent. 1999, ISBN 0-679-73869-X , pp. ??.

- ↑ World Register of Marine Species: Monetaria annulus (Linnaeus, 1758).

- ↑ World Register of Marine Species: Cypraea annulus Linnaeus, 1758.

- ↑ Entry: Monetaria annulus annulus. In: gastropods.com.

- ↑ Martin Lister: Historiae conchylioeum liber primus. London 1685, p. 59: Plate 709, quoted from Ramón de la Sagra: Histoire physique, politique et naturelle de l'île de Cuba. Paris 1842, p. 92 (French; side view in Google book search).

- ^ So also Janine Brygoo, Edouard Raoul Brygoo: Cônes et porcelaines de Madagascar. Antanarivo 1978, p. 127 (French). See also the collection of documents in Johann Samuel Schröter: Introduction to the Concyle Knowledge according to Linnaeus . Volume 1, Halle 1783, p. 120 ( side view in the Google book search).

- ↑ James Petiver: Gazophylacium naturae et artis. S. 8, plate 97, quoted from Ramón de la Sagra: Histoire physique, politique et naturelle de l'île de Cuba. Paris 1842, p. 92 (French; side view in the Google book search; however not detectable in a digitized version of the 1702 edition).

- ^ Carl von Linné: Systema naturae. 10th edition. Stockholm 1758, p. 723 ( online at bsb-muenchen-digital.de).

- ^ Joey Lee Dillard: Perspectives on black English. Mouton, The Hague 1975, ISBN 90-279-7811-5 , p. 206 ( side view in Google book search).

- ^ Gerhard Rohlfs : Across Africa. 1874, Chapter 12: The capital Kuka, the market and the realm of Bornu ( online at Projekt Gutenberg-DE ).

- ^ Friedrich Kluge , Elmar Seebold : Etymological dictionary of the German language . 24th, revised and expanded edition. Gruyter, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-1101-7473-1 , p. 713.

- ↑ Selma Gebhardt: From the cowrie shell to the credit card. Money development in the civilization process. 2nd, revised edition. Rosenholz, Kiel 1998, ISBN 3-931665-10-0 , pp. 81-85.

- ↑ Abu Zayd Hasan ibn Yazid Sirafi: Voyage du marchand arabe Sulaymân en Inde et en Chine rédigé en 851, suivi de remarques par Abû Zayd Hasan, vers 916. Editions Bossard, Paris 1922 (French; online in the Internet archive ; English translation of the title : Sulayman, the merchant ).

- ^ Janice Light: Shell money. Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland, January 2012, accessed August 15, 2014.

- ↑ Wiki entry: Kauri shells. In: Moneypedia. March 22, 2007, accessed August 15, 2014.

- ↑ a b c Anirban Biswas: Money and Markets From Pre-colonial to Colonial India. Aakar Books, New Delhi 2007, ISBN 978-81-89833-20-6 , pp. 143–162: Chapter 6 The Characteristics, Circulation and Decline of the Cowrie Currency (English; page views in the Google book search).

- ↑ finds in Ashkabad the time of Djeitun Culture 7000-6000 v. BC, with connections to Neolithic cultures in the Middle East are proven: VM Masson, VI Sarianidi: Central Asia: Turkmenia Before the Achaemenids. Praeger, 1972, pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Bin Yang: Horses, Silver, and Cowries: Yunnan in Global Perspective. In: Journal of World History. Volume 15, No. 3, University of Hawai'i Press, 2004, pp. 281-322, here pp. ??.

- ^ A b Ke Peng, Yanshi Zhu: New Research on the Origin of Cowries in Ancient China. In: Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 68, May 1995, p. 12: Phase 5: Disappearance of cowry-use ( PDF file; 1.2 MB, 30 pages ).

- ↑ a b c d Ardis Doolin: Money Cowries. In: Hawaiian Shell News. Volume 33, No. 6, June 1985, p. 7 ( online at internethawaiishellnews.org).

- ↑ Exhibit: Gold Beads in the Shape of Cowrie Shells. ( Memento of the original from August 14, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Collection of the Getty Villa Malibu, accessed August 15, 2014.

- ↑ Edouardo Fazzioli: Caractère chinois. Flammarion, 1987, p. 177 (French).

- ↑ a b c Chris A. Gregory: Cowries and Conquest. Toward a Subalternate Quality Theory of Money. In: Aram A. Yengoyan (Ed.): Modes of Comparison. Theory & Practice. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 2006, ISBN 0-472-06918-7 , pp. 193-219, here p. 196 ( side view in the Google book search).

- ^ Verrier Elwin: The Use of Cowries in Bastar State , India. In: Man. Volume 72, 1942, pp. 121-124, here pp. ??.

- ↑ Abhay Charan Mukerji: Hindu Fasts and Feasts. The Indian Press, Allahabad 1918, pp. 149-150.

- ↑ Elizabeth Allo Isichei: Voices of the Poor in Africa. University of Rochester Press, Rochester 2002, ISBN 1-58046-107-7 , p. 68 (English; side view in Google book search).

- ^ Gustav Nachtigal: Sahara and Sudan. Volume 3: The Chad Basin and Bagirmi. Hurst, London 1987, ISBN 0-905838-47-5 , p. 392 (English, translation of the German original edition Sahara und Sudan , Volume 3, 1889; side view in the Google book search).

- ^ A b John Roscoe: The Baganda: An Account Of Their Native Customs And Beliefs. Macmillan, London 1911.

- ↑ a b c d Oskar Schneider: Shell money studies. Geography Association in Dresden. Commissioned by E. Engelmann's Nachfg., 1905, p. 157.

- ^ Marion Johnson: A Note on Cowries. Research Review 2 (1), pp. 37-40. Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana

- ↑ a b c d Karl Polanyi: Dahomey and the Slave Trade; An Analysis of an Archaic Economy. University of Washington Press, Seattle 1966 (Reprinted by Ams, 1990, ISBN 0-404-62900-8 ).

- ↑ Mathew Forstater: Keynes and the Social Sciences. Contributions outside of Economics, with Applications Economic Anthropology and Comparative Systems. In: Robert W. Dimand, Robert A. Mundell, Alessandro Verselli (Eds.): Keynes's General Theory After Seventy Years. Palgrave McMillian, London 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-23599-1 ( PDF file; 1.2 MB; 8 pages ).

- ↑ picture 1 ; picture 2

- ↑ a b Paul Einzig: Primitive money in its ethnological, historical and economic aspects. 2nd edition Pergamon Press, Oxford 1966.

- ↑ Иван Георгиевич Спасский: Русская монетная система. Издательство Государственного Эрмитажа; 1970 (Russian; German translation of the title: IG Spasskij: The Russian coin system ).