Death joint

Death fugue is a poem by the German-speaking poet Paul Celan , which uses lyrical means to address the Nazi extermination of the Jews . It was written between 1944 and the beginning of 1945 and was first published in Romanian translation in May 1947. The German original version was published in Celan's first collection of poems, Der Sand aus den Urnen , in 1948 , but only achieved greater public awareness after being included in the subsequent volume Mohn und Gedächtnis in 1952 . Characteristic of the poem are a polyphonic structure based on the musical fugue , the motifs repeating and varying, as well as the use of paradoxical ciphers such as “Black Milk of the Morning”, which indicate the historical events without naming them specifically.

Death fugue is Celan's best-known poem, has been reprinted in numerous anthologies and school books, quoted at commemorations and often artistically adapted . But the poem also sparked controversy. Alleged and actual forerunners were discovered for his pictorial formulas. Against the background of Theodor W. Adorno's statement " to write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric ", critics accused Celan that the "beauty" of the lyrical implementation did not do justice to the subject of the extermination of the Jews. The death fugue nevertheless achieved international status as one of the most important poems commemorating the victims of the Holocaust, and became characteristic of the poetics of Holocaust poetry .

shape

Paul Celan

Todesfuge

Link to the full text of the poem

(please note copyrights )

Paul Celan's death fugue begins with the verses :

"Black milk of the morning we drink it in the evening

we drink it at noon and in the morning we drink it at night

we drink and drink

we dig a grave in the air because you don't lie close"

Then the perspective changes from the lyrical “we” of the prisoners digging their own grave to a look at a “he”, their overseer, who is writing letters to his beloved:

"A man lives in the house who plays with the snakes, who writes,

who writes when it gets dark to Germany

your golden hair Margarete"

The structure is reminiscent of the musical compositional principle of a fugue , in which different voices follow one another in imitations of one or more themes . Like Dux and Comes in the musical fugue, two voices stand opposite each other in the poem: the “we”, the chorus of the victims, the “he”, the actions of the perpetrator figure. They are played through in modifications, variations and new approaches and are interwoven and interwoven in such a way that a "dramatic structure" results "between the deadly master from Germany and the Jews who live and work or make music in anticipation of their death". The confrontation gradually intensifies, up to and including annihilation.

The death fugue is interpreted by different interpreters as a double fugue with “we” and “he” theme or as a triple fugue with the third theme “death is a master from Germany”. Another possibility is the tracing back to a single theme, which is formulated in the "we sections", while the "he sections" form a counterpoint characteristic of the fugue . The topic in the “we part” is only changed slightly; in counterpoint, on the other hand, the motifs change and give the static compositional principle of the fugue a progressive sequence and development. It leads to a juxtaposition of the closing verses reminding of the principle of counterpoint:

"Your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Sulamith"

Another musical principle that the poem makes use of is that of modulation . The “grave in the earth” changes to “grave in the air”, to “smoke in the air”, “grave in the clouds” and “grave in the air”. According to Ruth Klüger , the fugue-like composition pattern has the effect that listener and reader are torn between “a world that has fallen apart and one that fits together like a fugue and provides musical consolation.” Celan, however, deliberately denied “composed according to musical principles " to have. He gave the poem the title Death Fugue only afterwards.

The poem is thematically divided into stanzas . The total of 36 verses are divided into four parts: nine verses in the first stanza, six and three verses in the following two stanzas, five and three verses in the fourth and fifth stanzas as well as the eight verses of the sixth stanza and the detached final Couplet. Each part begins with the leitmotif "Black Milk of the Morning", which holds the poem together as a formal bracket. The metaphor appears a total of four times and is varied by the sequence of the time adverbs “evening”, “noon”, “morning” and “night” as well as the change from the third (“she”) to the second (“you”) person. In the fourth section, the allegorical picture “Death is a master from Germany” interrupts the process so that the short line “we drink and drink” is disturbed and recombined in a long line .

The sentences of the poem follow a uniform sentence model and are arranged paratactically . There is no punctuation . The 36 verses of the poem consist mainly of long lines, which are interrupted by shorter verses. As a meter of the rule Daktylus and amphibrach ago. While in the dactyl there are two unstressed syllables after a stressed syllable, in the Amphibrachys a stressed syllable stands between two unstressed ones, for example in “we drink and drink”. The passages of the central metaphor “Black Milk of the Morning”, on the other hand, are shaped by the Trochäus . Numerous enjambements and anaphoric repetitions underline the flowing movement. Instead of a classic metric, the rhythm of speech and open expression are based on the “contrapuntal construction” and the “metaphorical lines” of the poem. For Helmuth Kiesel and Cordula Stepp, the fugue of death stands in the tradition of free- rhythmic and rhyming, dynamically urgent classical hymns , "which primarily served to reflect on the encounter with the numinous, the sublime, the dangerous and the fateful". Jean Firges , on the other hand, refers to the plaintive and accusatory choral singing of ancient drama .

interpretation

"Black milk of the morning"

The central, leitmotif metaphor of the poem - "Black milk of the morning" - is an oxymoron . While the noun “milk” is generally used with positive connotations, this expectation is canceled out by the adjective “black” and turned into the opposite. The milk does not give life here, but becomes the “milk of death” that brings spoilage. The "Early" is so Theo Buck , not for days but for the indefinite zone between life and death. The image “Black Milk of the Morning” becomes a symbol of the Shoah , without explicit mention of gas chambers or crematoria . It translates the reality of the mass extermination of human beings, which cannot be put into words, in an alogical picture and thus brings it to language.

In his drafts for the Büchner Prize speech (later under the title The Meridian ) Celan emphasized this relation to reality: “Black milk of the early days” is not a “genitive metaphor as it is presented to us by our so-called critics”, “it is neither a figure of speech nor a figure Oxymoron more , that's reality . ”He found the reality of his metaphor confirmed in a newspaper article on the Auschwitz trials, which he provided with underlines:“ ' My milk was black, ' replied Klehr , which he apparently meant to say that he had the milk organized […]. ”A similar transformation of the terrible reality of the annihilation ovens into a poetic expression is the“ grave in the air ”. It is in mirror image contrast to the “grave in the earth” that the doomed have to dig themselves. In a letter to Walter Jens Celan wrote: "The 'grave in the air' [...], that is, in this poem, God knows neither borrowing nor metaphor".

The tripartite metaphor “Black Milk of the Early” now serves as a prime example of the style figure of the bold or absolute metaphor, in which the tertium comparationis can hardly be recognized. For their understanding, reference is therefore made to possible origins and analogies of the figure. Traces lead to poems by other poets from the Bukovinian Circle of Friends (see section: Influences ), in which the metaphor is echoed or literally appears in a different context. In this context, philologists speak of a “metaphor network” or a “wandering metaphor”. Georg Trakl (“black frost”, “black snow”), Franz Werfel (“black mother's milk of the end”) and Arthur Rimbaud (“lait du matin et de la nuit”) also used comparable pictorial formulas . The title of the poem “Black Flakes”, which Celan wrote in 1943 on the death of his father and in memory of his mother, is a preliminary form of the metaphor. The pictorial transformation from white to black can be traced back to the lamentations of Jeremiah in the Old Testament: “Their young men were purer than snow, / whiter than milk, their bodies rosier than corals, / their veins sapphire blue. / They look blacker than soot, / you can't see them on the streets [...]. "( Klgl 4,7–8 EU )

"Your golden hair Margarete / your ashen hair Sulamith"

The polyphonic and contrapuntal form of the fugue-like poem is clearly expressed in the two final lines . On the one hand, the metrically identically shaped “twin motifs” are put together in parallel, on the other hand they stand against each other in terms of content. Kiesel and Stepp therefore describe this close interweaving as "false polyphony", John Felstiner sums up: "- but the harmony is discordant". While most of the poems have exhausted their pictorial power at the end, the death fugue ends with a close-up of the biblical Sulamith from the Song of Songs of the Old Testament . But she is not the bride-to-be, whose splendor of hair resembles purple royal robes ( Hld 7,6 EU ); Sulamith's "ashy hair" is a picture of the Jewish victims of the Shoah under National Socialist rule . The image of suffering is preceded by a close-up of a familiar female figure from German classical and romantic poetry, who is surrounded by the aura of Germanism: Margarete, Gretchen , lover of Goethe's Faust : “your golden hair Margarete”, with the echo of Heinrich Heines Lore-Ley : "She combs her golden hair".

The allegorical female couple Margarete and Sulamith stand in the long Christian pictorial tradition of depictions of the beaten, blind synagogue and the triumphant Ecclesia , which is also embodied by Mary , the mother of Jesus: in “side by side and against one another”, “in stone allegories on old church portals: images of pain and memories of Judeo-Christian, Judeo-German history ”. Such a juxtaposition of the allegorical fateful sisters Sulamith and Maria can still be found in romantic art, for example in the pictures of the Nazarene Franz Pforr and Friedrich Overbeck . Celan took over the contrast between the “ideal brides” of the Old and New Testaments, but according to Theo Buck he made a “paradigmatic change” in that Margaret used the New Testament Mary or the figure of Ecclesia, the German “ideal image of the golden-haired girl”, replaced.

The comparison of the two women in Celan's poem is mostly interpreted as an accusation. The female figures appear in opposition, not in common. John Felstiner summed it up: “The German and Jewish ideal will not exist side by side.” For Buck, too, the poem ends with the closing verses in tension between cultures, in dissonance instead of harmony. Despite the efforts of National Socialism for an Aryan identity, the last word is reserved for Sulamith. After the final look at her ashen hair, there was silence.

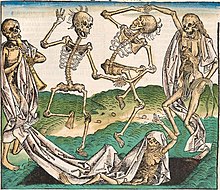

Due to the compositional interweaving of the two female figures through the contrapuntal narrowing of the ending, it is occasionally pointed out that Gretchen was also a victim, was seduced by Faust's rhetorical duplicity and ended up in dungeon as a madwoman. Margarete in the final verse is also a lover, who receives testimonies of love: "A man [...] writes your golden hair Margarete when it gets dark to Germany". The lover is at the same time the terrible annihilator, embodiment of death who whistles out his Jews and lets them play to dance. The poem is thus in the tradition of the dance of death poems , in which death is addressed as a master, but also in the tradition of musical works with the motif Death and the Maiden . Felstiner recalls the compositions of the same name by Franz Schubert , the song from 1817 based on the poem Der Tod und das Mädchen by Matthias Claudius and the string quartet No. 14 in D minor, D 810, for whose set of variations Andante con moto he used the song's theme. But he also refers to the connection between death and music in Richard Wagner's Liebestod der Isolde and Gustav Mahler's Kindertotenlieder . This aestheticization through covert quotations from the history of literature and music makes the horror of historical events particularly blatant.

Dieter Lamping, who in his study on the death fugue particularly emphasizes the Jewish tradition of text form, sees the dance motif in the Song of Songs as pre-formed ( Hld 7.1 EU ). In addition to the motifs of the name, hair and dance, those of milk, gold and drinking are also biblically anchored. Thus the Song of Songs is not only a source of the fugue of death; it is their model , the modern poem is a counterfactor of the biblical text. The biblical motifs are “incorporated into the complex of motifs of mass death: the milk turns black, the hair is ashy, the round dance becomes a dance of death. The gold, an attribute of Solomon and Sulamith in the Song of Songs, is now one of Margaret. The changes in the motifs go hand in hand with the change of genre: the love song becomes a lament for the dead ”. Celan emphasized this concern of having written a lament for his mother, who was murdered in a German concentration camp in the winter of 1942/43, in a letter to Ingeborg Bachmann dated November 12, 1959: “You know - no, you knew - and so now I have to remind you that the death fugue is this for me too: a grave inscription and a grave. [...] My mother also only has this grave. "

"A man lives in the house"

Throughout the poem, victims - the "we voices" - and perpetrators - the "he voice" - are juxtaposed and linked by the common theme - being killed - and its counterpoint - killing. The nameless perpetrator living in the house gives orders: "He whistles", "He orders", "He calls". He “plays with the snakes”, that is, with evil, the motive of temptation in the fall . He “whistles for his males”, who stand for the hound dogs of the hunt as well as for the adjective “rude” in the sense of rough and ruthless. He lets the victims play to dance, perverting the beauty of the music to horror. The maxim “Death is a master from Germany” also addresses the transition from a masterly craftsmanship to the perverse perfection of a killing machine.

In a letter to Walter Jens, Celan emphasized the “archetypal transformation” from Margarete's hair to the snakes: “Hair (and here, with the Gretchen figure, you also think of braids) often (in fairy tales and myths ) transforms into Snakes. "Firges extends this archetype to the figure of the perpetrator himself. For him, the sadist in the eyes of the victims slips into a modern allegorical mask of death:" The German as master of music, the German as master in the perfect killing of innocents a million times over - highest culture and shameful barbarism: both connotations coincide in the allegorical figure of the 'Master from Germany' and give this language creation its memorable power and suggestive aura. "

But the man whose activities are richly unfolded in the scenery is not just a demonic figure of evil . He “writes to Germany when it gets dark”, letters to his lover Margarete. He looks up to the sky and loves the music. His sentimental allusions extend to an aestheticization of the murder process. Celan portrays the perpetrator as a mixture of romanticism and brutality, subservience and arrogance , idealism and nihilism . His "eyes are blue", but when he kills he squeezes one thing: "his eye is blue". This passage is emphasized by the only rhyme in the poem: "it hits you exactly". In a poem near the graves , also written in 1944, Celan conjured up in memory of his mother “at home / the quiet, the German, the painful rhyme”. In the fugue of death , the “painful German rhyme” has become fatal. Even Peter von Matt points out in his interpretation that Celan was referring to the death of his mother, who loved the German poet and was shot by a German.

At the moment when the perpetrator steps in front of the house and whistles his males, "the stars flash". On the basis of this passage, Buck and Felstiner develop a broad “range of associations”. It ranges from Eichendorff's “So star-clear was the night” ( Mondnacht ) to Puccini's line of arias “And the stars flashed” from the opera Tosca to the Landser song Heimat, your stars , popular in the Third Reich , the sentimental hit, the “SS -Let officers play the Auschwitz camp orchestra ”. For Felstiner, Hitler's Blitzkrieg can also be heard . It is just as realistic to think of military insignia. Felstiner adds that “a Star of David can also be seen above this line”. In connection with Celan's method of covert quoting and networking, Neumann emphasizes that an isolated consideration of individual linguistic expressions is forbidden, the connection between Jewish and German images has its contrapuntal and historical sense. Buck also points out the relation to reality of these associations when here the poet umpole the form and attitude of the “traditional evening poem” to the image “of a darkly shaded 'night', which corresponds to the 'ashy hair of Sulamith'”.

In connection with the figure of the “banal prototype” of the “master race that kills with“ mastery ”, allusions were repeatedly made to Hannah Arendt's realization of the banality of evil , which Celan had metaphorically anticipated as an allegory. In addition, since the knowledge of the role of prisoner music in the death camps , interpreters have supported the reality of this scene through documentary references to the use of the camp chapels, which, among other things, had to play during the extermination campaigns, and to the authentic figure of the "conductor" (see section History of origin ). According to Firges, sentimental excitement is paired with aesthetic sensitivity and sadistic lust in this passage, which is celebrated in the “ritual of the dance of death”.

"We drink and drink"

The poem is spoken by a choir in the first person plural, the "we". It stands for the suffering, the victims of the German extermination of the Jews. "He", the perpetrator, is portrayed from their perspective. The constant repetitions of the choir of passions intensify the event until it is concluded in the last two verses with the comparison of perpetrators and victims, Margaret and Sulamith. In his notes Celan wrote: “The dying speak - they speak | only as such - death is | you sure - you speak | as dead and dead. You | speak to death, from death. They drink from death ”. In his Büchner Prize speech too , Celan emphasized the dialogic character of the poem as "conversation - often it is a desperate conversation".

The poem preserves the story of suffering of the dying beyond their death. According to Theo Buck, the choir wants to be understood as a memorial to the dead , a dialogue aimed at the reader, a haunting message from the dead to survivors and future generations. In addition to other ways to keep the German murder of Jews in memory forever, for example through witness reports and documentations, Celan set his way, the artistic way of a poem. Emphasizing Jewish influences such as Jeremiah's Lamentations and Psalm 137 as well as the Song of Songs, Lamping sees a liturgical element in the identity-creating choral speech . As a poem about the extermination of the Jews, the fugue of death continues the Jewish tradition of “remembering a historical trauma”.

History of origin

Celan's hometown Chernivtsi , part of Romania since the First World War , was occupied by the Soviet Union in June 1940 as a result of the Hitler-Stalin Pact . After the attack by the German Reich on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the German Wehrmacht invaded Bukovina . Under the renewed sovereignty of Romania, there were massive crackdowns against the local Jews , who were driven to a ghetto and deported . Also Celan's parents were deported in 1942: the mother was shot on the way, the father died in Transnistria (Romanian occupation zone) to typhoid . Celan himself was sent to a labor camp , where he had to do forced labor in Romanian road construction, was later used as a translator until he regained his freedom in February 1944 and - before the Red Army - returned to Chernivtsi.

Friends from Bukovina stated that Celan was working on the death fugue as early as 1944 . Celan himself wrote to the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt that he had " written the poem in Bucharest in the spring of 1945 ". Theo Buck assumes that the first drafts were made in autumn 1944, but that the death fugue did not take on its final shape until the following spring. He judges that with this poem Celan overcame his epigonal beginnings and for the first time found his own unmistakable expression.

Two years later, on May 2, 1947, the Romanian translation of the poem by Celan's friend Petre Solomon appeared in the magazine Contemporanul under the title Tangoul morții (Death Tango ) . It was Celan's first publication. The print was accompanied by a comment by the editor-in-chief, who reduced the poem to a realistic basis and thus protected it from a possible charge of formalism : “The poem, the translation of which we are publishing, goes back to facts. In Lublin and other death camps' of the Nazis became a part of the condemned forced aufzuspielen while another graves dug. "John Felstiner goes on to say that an SS lieutenant in the concentration camp Janowska , near Czernowitz, the prisoners at executions and torture I ordered the playing of a tango called "Death Tango". Likewise, in Auschwitz and other camps, music accompanying executions was described as "death tango".

In formal terms, too, pebbles and quilts make the poem and tango similar . The death fugue does not express grief and lament in the same emphatic way as the dance, but it also tells a story with a dramatic course, speaks to the listener directly and reminds the rhythm of the rapid movement of the tango with its interspersed syncopation . The reasons why Celan ultimately decided against the title Death Tango and for Death Fugue are unknown. Kiesel and Stepp speculate that Celan had recognized the formal proximity of the poem to the fugue as greater, that the fugue placed greater emphasis on the contrast between the sophistication of the perpetrators and the barbarity of their deeds, or that the European view of tango as an erotic dance would have brought an unintentionally frivolous undertone into the recording of the poem.

When Celan, after leaving Romania, published his first collection of poems, The Sand from the Urns , in 1948 , the poem under the changed title Death Fugue formed the climax and conclusion of the volume. The collection was only published in small editions and was also so distorted by printing errors that Celan withdrew and destroyed it. It was not until 1952 that the poem became known to a wider public as part of his second collection of poems, Mohn und Gedächtnis . In this edition, too, it was highlighted as a separate chapter in the middle of the book.

Celan's estate is in the German Literature Archive in Marbach . The typescript of the fugue of death , still in the version of the tango of death , can be seen in the permanent exhibition along with other parts from Celan's estate in the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach.

Influences

Literary scholars have examined the influences of earlier poems on Celan's death fugue , which range from the works of Arthur Rimbaud , Georg Trakl , Franz Werfels to those of Alfred Margul-Sperber . Rose Ausländer claimed the authorship of the metaphor "Black Milk", which she formulated in her poem Ins Leben , written in 1925 but not published until 1939 . However, she emphasized: “It is my honor that a great poet found inspiration in my early work. I didn’t use the metaphor casually, but he elevated it to the highest poetic expression. She has become a part of himself ”. In contrast, Claire Goll raised allegations of plagiarism against Celan throughout her life . She saw the death fugue influenced by her husband Ivan Goll's Chant des Invaincus , published in 1942 . In the so-called Goll affair distorted quotations and especially with subsequently processed by Claire Goll texts was manipulated data, argues. Celan saw the plagiarism allegation as a denial of his own life story and thus, according to a letter to Siegfried Lenz on January 27, 1962, “as the subsequent completion of the ' final solution ' to himself”.

It was not until 1970 that Immanuel Weissglas , a childhood friend of Celan's youth, published his poem ER , which was written before the fugue of death and which had partially anticipated its motifs and metaphors. Weissglas already linked death with playing the violin, spoke of a "house with snakes" and "Gretchen's hair" and ended with the statement that "death was a German master." Heinrich Stiehler, who was the first to examine the relationship between the two poems , judged: “The dependence of the fugue of death on these verses of the friend, written only a few months earlier, is obvious.” The philologist Jean Bollack , a friend and companion of Celan, cites two hypotheses that explain the similarity of the two poems : According to the first, the use of the same literary material goes back to a common fund, which included the literary and cultural traditions of the region as well as the influence of the presence of the Holocaust, while the second hypothesis assumes that Celan was the predecessor of Weissglas and the fugue of death is to be seen as an answer to ER . Bollack joined the second argument and ruled Celan arrange "his constituents new about without adding extra: there are the same elements, but from which he does something completely different." Juergen Wertheimer agrees that all motives of Death Fugue by ER anticipated be, but also “that each of these motifs in Celan's text reveals an incomparably greater density, intensity and ambivalence, precisely because Celan (only he) develops a system of signs specifically directed towards death from various metaphors of death, which expresses the totality of Let destruction become tangible. "

Barbara Wiedemann, the editor of the newly annotated complete edition of the poems, however, emphasizes with regard to these discussions about the genesis that there is no evidence, "that the poem Er , published shortly before Celan's death, by his Czernowitz colleague Immanuel Weißglas, which contains some clear parallels to the death fugue , earlier than this was created. "

John Felstiner pointed out that Celan used "broken world word material to which the poem testifies" in every line of the death fugue . The references from music, literature and religion ranged from Genesis to Johann Sebastian Bach , Richard Wagner , Heinrich Heine , the tango, Faust's Gretchen ("Margarete") to the virgin Sulamith from the Song of Songs. Theo Buck adds the lamentations of Jeremiah , medieval dances of death , the practice of the Mastersingers , elements of the Baroque , Giacomo Puccini (see section “A man lives in the house” ), Charles Baudelaire , Arthur Rimbaud, Rainer Maria Rilke and Georg Trakl as well the German hit home your stars . He sees the intertextual transformation as well as the bitter parody as an essential part of Paul Celan's form of expression and emphasizes that there is no epigonality in such quotations , rather Celan questions the quotation through its use, examines the traditional references and partially annuls them. Dealing with traditional materials is a central part of Paul Celan's artistic process: “The poetically transformed 'quotations' serve to combine concreteness and simular character that he strives for. Because working with the language and image formulas adopted from the canon allowed the author to desubjectify the topic that was existentially relevant to him. ”In addition, Neumann explains that the only way to get there is to cite“ beauty ”in this text too”. According to Felstiner, the reconstruction of these traces helps "to recognize the poem which speaks its verdict about the whole so-called Judeo-Christian culture."

reception

Reading in group 47

Celan's death fugue remained largely unknown to the public until the publication of Poppy and Memory in December 1952. A reading by Celan at the Group 47 meeting in May 1952, which came about through the mediation of the Viennese friends Ingeborg Bachmann , Milo Dor and Reinhard Federmann , was a failure. Walter Jens remembered the reading in 1976 in conversation with Heinz Ludwig Arnold : “When Celan appeared for the first time, they said: 'Hardly anyone can hear that!', He read very pathetically . We laughed at it, 'He reads like Goebbels !' Said one. [...] The death fugue was a failure in the group! That was a completely different world, the neorealists couldn't keep up. " Hans Weigel added," that afterwards some colleagues scorned: 'Black milk of the early ...' "and Hans Werner Richter criticized Celan had" in read to a chant like in a synagogue ”. Celan himself commented in a letter to his wife Gisèle: "So those who do not like poetry - they were in the majority - rebelled." After all, during the reading, the chief editor of the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt became aware of Celan, which she pointed out published Poppy and Memory in December . Ernst Schnabel organized a reading in the NWDR after the conference .

Contemporary reviews

After its publication, Mohn und Gedächtnis received benevolent reviews, but with a few exceptions they ignored the historical background of the death fugue . The predominant voices were those who concentrated on formal aspects and wanted to recognize in the poems a metaphor that had grown out of French surrealism . Heinz Piontek wrote about Celan: “His lyric poetry is pure poésie , magical montage , comparable to the pictures of Marc Chagall ”. Helmuth de Haas recognized “surrealist traits” in the fugue of death : “There is [...] the lift of everything representational, the sucking rhythm, the romanticizing metaphor, the lyrical alchemy ”. Celan is “a surrealist who controls his spontaneity and renounces the automatic texture.” Paul Schallück ended his review in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung with the imprint of the death fugue and the prognosis: “But we will [...] remember that we have never read such verses before. "

After the magazine Contemporanul had already sent the comment in 1947 to the reprint of the Romanian translation that Celan's poem conjured up historical facts, seven years later the “(already famous) fugue of death ” sang for Hans Egon Holthusen “one of the most terrible and significant events of the most recent History, the massive cremation deaths of Jews in German concentration camps in a language [...] that is true and pure poetry from the first to the last line, without a trace of reportage, propaganda and reasoning. ”He understood this transformation as a form of aesthetic coming to terms with the past : “Drinking is dying as the ultimate self-realization, sacrificial death, ascending to a 'grave in the air'. With just a few simple paradoxes , Celan was able to master a theme that bursts all human grasp and transcends all limits of artistic imagination: by making it very 'easy', by making it transcend in a dreamy, overreach, in a sense already otherworldly language , so that it can escape the bloody chamber of horrors of history in order to ascend into the ether of pure poetry. "With this work-immanent interpretation , which named the historical reference in Celan's poem, but" immediately dissolved it into a transcendental aesthetic sphere ", was the contemporary interpretation of the Poem essentially set.

The Celan biographer John Felstiner comments on this interpretation by Holthusen and the prevailing reception in Germany in the 1950s: “But what rose into the ether in Celan's poem was the Jews, not the poem; It was not death fugue that wanted to escape the 'bloody horror chamber of history', but the German readers of the poem. And so they turned Celan's poem into an apotheosis : 'one of the greatest poems of our time', praised Holthusen. "

Ute Harbusch distinguishes three positions in dealing with the reality content of Celan's visual language. Once you read that Celan is completely turning away from reality, another time, he transforms reality into pure poetry, and a third time, he creates a " mimetic relationship to reality" precisely through his non-naturalistic way of lyrical speaking . She sees in it "positions that are not only dependent on the authors' aesthetic convictions, but also on their more or less pronounced 'inability to mourn'."

Adorno's verdict

A few years after Celan had written his death fugue , but before it became generally known, Theodor W. Adorno published his essay Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft in 1951 , in which he expressed the now famous thesis: " To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric " . Adorno's dictum accompanied the recording of the death fugue in the years and decades that followed ; According to Ruth Klüger, it became “the focus” of Adorno's sentence. As it was about “the legitimation of their own writing, the defense of the poem”, the poets in particular felt provoked. Wolfdietrich Schnurre reacted with sharpness : “Did the self-related poems by Andreas Gryphius withstand the atrocities of the Thirty Years' War or not? They withstood them just as Celan's fugue of death withstands the files of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial ”. Human language is not there to be silenced, "it is meant to be spoken".

Celan's relationship with Adorno was determined by an intensive reading of his writings, so he - as stated in the Celan Handbook - critically received Adorno's verdict for his poetry and followed very closely how the philosopher later concretized and softened his misunderstood word. Celan rejected Adorno's thesis most clearly in his materials on Atemwende (1967): “What is assumed here as an idea of a poem? The arrogance of those who hypothetically speculatively consider Auschwitz from the nightingale or song thrush perspective or to report ”. Adorno later withdrew his earlier verdict “under the impression above all of Celan's Holocaust poetry”, with the awareness: “Celan's poems want to express the utmost horror by keeping quiet”: “What the sadists in the camp told their victims: tomorrow you will be Smoke from these chimneys to meander into heaven calls the indifference of life of every individual towards which story is moving […] Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as the tortured man to roar, so it may have been wrong to go to Auschwitz no more writing a poem. "

With the volume of poems Sprachgitter and his “depoetizing aesthetics”, Celan reacted consciously as a poet to the discussion initiated by Adorno. Engführung , the final poem of the volume, is considered to be the “rewriting of the 'death fugue' with other poetic means” and “radicalization of the death fugue”. The term “ narrowing ” also refers to the form principle of the joint. Single words like “star” and “ash” repeated three times, but above all the lines “none / smoke soul rises and plays with” are echoes of the fugue of death . However, they are not only to be understood as a reminder of the victims of Auschwitz, but also conjure up, as Celan explained in a letter to Erich Einhorn, “the ravages of the atomic bomb”. After Kiesel und Stepp, a text landscape in a “grayer language” emerges as a result of the “renouncement of verbal jewelry” than a “landscape of devastation, destruction and death from which almost all words of beauty are banished”. The linguistic theoretical basis of this new form of his poetry can be found in Celan's answer to a survey by the Parisian Librairie Flinker from 1958: The language of German poetry has become “more sober, more factual, it distrusts 'beautiful', it tries to be true . "

Poetological discussions

According to Peter Horst Neumann , the death fugue is “an important element of the political intellectual history of the Federal Republic” of Germany. Dieter Lamping recalls that until today (1998) the poem has been exposed to various aesthetic, moral and historical criticisms. From the perspective of a dramatist of the documentary theater, Rolf Hochhuth criticized in the foreword to the fifth act of his play Der Stellvertreter that Celan had “completely translated the gassing of the Jews into metaphors”, which poetized reality into a legend and an apocalyptic fairy tale. In contrast, Lamping states that the success of the death fugue is not only based, "as is often suspected, in its suggestiveness and problematic musicality, but also in its poetic radicalism."

In his publication Problems of Literary Valuation (1965), Walter Müller-Seidel refers to the unbridgeable gap between the present inhumanity on the one hand and the claims and possibilities of art on the other. In his fundamental considerations on the question: “Can art still be if there is inhumanity on such dimensions?” He explicitly refers to Reinhard Baumgart , who in 1965 had concretized Adorno's objection to Celan's death fugue in Merkur : “Celan's 'death fugue' for example and their motifs [...], composed in a refined score - didn't it already prove too much enjoyment of art, of the despair that it had made 'beautiful' again? ”On the other hand - according to Müller-Seidel - the sonic beauty of the poem was misunderstood when“ im Hearing the beautiful sound the horror “is not considered. Those who find Celan's poem too beautiful should be answered: “A poem - even a modern one - cannot be beautiful enough if it just doesn't gloss over anything”. Celan's fugue of death is far removed from any glossing over . In order to justify the beauty of Celan's fugue of death , Lamping agrees with Neumann's assessment: “The poem,” he claims, “has the most macabre enjoyment of art on its subject. Whose? 'The Master from Germany'. - No historical horror is glossed over here: Rather, the historically beautiful, the art of the fugue and with them Celan's poem are set into one with horror: not as the beauty of horror, but as an abomination of beauty. "

Death fugue and Holocaust poetry

The death fugue serves as a central example for the thematic and formal clarification of the term “ Holocaust poetry ” in the sense of poetics . According to Lamping, “turning to the victims” is at the center of the characteristics. The pluralistic speaking from the we perspective in the “Canon of Jewish voices before they fall silent” is considered to be “a sign of the special human commitment” of this poetry . Above all, the artistically demanding examples of Jewish poets aim to identify with the victims. As role poems from the victim's perspective, as rescued or escaped, they lament the “fault of (co) humanity”. In this context, Lamping speaks of “poetic grief work ” and a “poetic judgment”. In addition to the pronominal form of utterance in pairs of opposites, for example of “we” and “he”, as well as other oppositions (for example golden hair-ashen hair, Margarete-Sulamith, dead-living, the world outside-the world within the extermination camps) and negations Above all, the forms of alienation , especially through “bold metaphor ”, shape the style. They combine language signs from the realm of death and destruction with those from the world of security and healing. “Metaphors of this kind have in common that they show the totality of destruction, the omnipresence and all-embracing of (annihilating) death”. A dissolving or "damaged" syntax and structure as well as the mutilation of words are typical means of approaching the horrific reality of extermination. “Key points” on the effect of Holocaust poetry, which Lamping gained from Adorno's statements, are: “'Shock' through hermeticization; 'Shame' in the face of suffering; 'Extreme horror' expressed by hiding ”.

The mentioned style and form features stand in contrast to demands for a sparse, realistic language, such as was raised by Gert Mattenklott : "Appropriate 1945 would have been an extreme sobering up of the poetic language". The found language of the death fugue and other Holocaust poems, especially of Jewish origin, replaces "the literary historical paradigm of mimesis , the exact reproduction of reality, with the paradigm of deixis , leading to the unspeakable".

Lamping examines further examples of artistically demanding Holocaust poetry of international standing, always using the death fugue as a typological comparison. The style and shape features can vary, contrast or sharpen in detail, but they are always integrated into the theme of the memory of the dead or the lament for them. More realistic accents than Celan's fugue of death are set by poems whose titles name the places of extermination or which use the perspective of a specific speaker instead of the choral “we”. Some works already begin with negations, such as Richard Exner's text with the mutilated title Dtschld , whose first word is “No”, others end emphatically with negations such as Różewicz's posthumous rehabilitation : “The dead will not rehabilitate us”. According to Lamping, Holocaust poetry has basically found a formal and linguistic possibility to “lend a voice to suffering (perhaps more than those who suffer)” and in doing so has shown “artistically and morally as sensitive as it is radical”.

In addition to the death fugue , Lamping mentions :

- Paul Celan: Chymic

- Nelly Sachs ' cycle: In the Apartments of Death

- Michael Hamburger : Treblinka

- Randall Jarrell : A Camp in the Prussian Forest

- Yevgeny Yevtushenko : Babiy Yar

- Tadeusz Różewicz : Posthumous rehabilitation

- Czesław Miłosz : Poor Christian sees the ghetto

- Richard Exner : Dtschld

The Shoah Recource Center Yad Vashem attaches inestimable educational value to Holocaust poetry. As one of the most powerful poems about the extermination of Jews in concentration camps, the death fugue found its way into Yad Vashem's educational and e-learning program, along with other poems from many countries .

Impact history

After the death fugue had found inclusion in numerous school books and anthologies and, in Celan's own opinion, had been “threshed ready for reading”, the author finally resisted that it was used for school books and memorial lessons and no longer read it publicly. Otto Pöggeler judges: “The poem should not become a cheap alibi for a lack of personal efforts to find out about its origins and the past.” However, when Hans Mayer evaluated the later poem Engführung as a corrective and taking back the fugue of death , Celan declared: “I never take back a poem, dear Hans Mayer. "

The meaning of the poem remained unbroken even after Celan's death. The death fugue not only became the “best-known example of Holocaust poetry”, but for Winfried Freund it became “the most famous poem of classical modernism ”. The Celan biographer Wolfgang Emmerich evaluates: “His death fugue is a, yes, perhaps the poem of the century”, and his colleague John Felstiner calls the death fugue the “ Guernica of European post-war literature”. She had "received more passionate attention than any other poem that was written during the war" and had "become an actor in history itself": "No poem brought the misery of its time to language as radically as this one".

With regard to Adorno's thesis in 1967, Peter Härtling restricted: “Poems were written after Auschwitz, but not about Auschwitz; Celan's death fugue also paraphrases the echo of the death screams incomparably. She does not make the murder visible. We have not found any poetics that reflect the horror of our contemporaries. "In the afterword to his anthology " Resistant is the easily vulnerable " , Wulf Kirsten explains that his selection on Death Fugue , the" most important and momentous poem of the era (Harald Hartung) ", taper in steps and break off with it. At the same time, it is “at the beginning of a post-work on a verbally manageable story and a 'grief work' that will never be manageable.” Ruth Klüger concludes her interpretation as follows: “The 'death fugue' has proven itself. According to Aristotle 's definition, tragic art brings about purification through fear and pity , better translated as misery and horror, and that makes the past we carry with us a little more bearable. "

Adaptations

Lecture

Due to its musical structure, the death fugue is particularly suitable for lectures. There is a recording of Celan himself, which was published by Günther Neske as part of the speech record edition Lyrik der Zeit . Later, however, Celan refused to read his poem, and in 1970, when asked about setting it to music, he replied: “This poem must now remain in its entirety for a long, long time. I myself no longer read it publicly either. ”In the German Bundestag , Ida Ehre presented the death fugue immediately before Philipp Jenninger's speech on November 10, 1988 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the November pogroms in 1938 , as a result of which the German Bundestag President resigned. In retrospect, Jenninger also attributed the negative effect of his speech to her connection to Ehre's recitation, which was "very moving": "It was probably not the ideal setting for a sober historical lecture."

literature

Epic scenes

The aesthetic effect of the death fugue was thematized in the prose works of Marie Luise Kaschnitz , Heinz Piontek and Hermann Lenz , in which Celan appears as a literary figure . He appears consistently as “a person of charismatic aura” and a stranger. The respective autobiographical background of this prose and the literary life of the time can be verified through authentic records such as diary entries and correspondence with comments.

Marie Luise Kaschnitz's short story The Departure was written in 1950. It is a reflection of the conversations with Celan on the occasion of an international writers' meeting in October 1948 in the Abbey of Royaumont . In the labyrinth of a surreal dream tale, the stray soul of the first-person narrator encounters the young “poet from the East”. He, "the homeless man with the calm, melancholy look", asks her not to leave yet: "Wait until I have read to you, my fugue of death, your golden hair Margarete, your ashen hair, Sulamith!"

Heinz Piontek had the main character Reichsfelder meet Celan in a café in his novel Dichterleben from 1976, in which the literary scene in Munich in the 50s is captured. The poet, who feels persecuted as “wild”, assures him that the death fugue is in the tradition of German dance poems, the verse refers to a poem from the 16th century in which death is addressed as a master . The literary conversation of the scene between the fictional character of the novel and the real character Celan is completely under the spell of what the "Air of the Chosen" surrounds.

Hermann Lenz created a “particularly touching representation of Celan” in the fifth of his autobiographical novels A Stranger in the figure of the poet “Jakob Stern”. The novel is largely devoted to the deep aesthetic understanding and friendship between Eugen and Jakob and between his "half-Jewish" wife Hanne and the Jewish poet. “From the star” - it is said - “emanated a radiation force; of him and his verses ”. In Hannes' thoughts the reverberation of the “fugue of death” read connects with the portrait of the poet: She thought “of the great poem she had read of him and, because he was not a tall man with a boldly torn face, wondered how she had imagined him reading. Instead, he looked like someone who would previously have been called cultivated or refined; and actually it didn't fit into this present ”.

Verses as quotations

In his novel monologue Kaddisch for an unborn child, Imre Kertész took up the motif of the cloud grave as a leitmotif and developed the quotations from the death fugue into a confession about his writing after the Shoah . As a writer, the narrator of this funeral prayer sees it as his concern to reflect on his refusal to create and pass on life after Auschwitz. His task as a survivor is basically nothing more than digging on at the cloud grave, which is as much the scene of redemption as of damnation: "Cloud grave: the book that contains the endless list of names of the dead and the never-born". To do this, the narrator had to look up into the clouds into which he was digging his grave with the ballpoint pen, “diligently like a slave laborer whom one whistled out day after day, that he prick the spade deeper, that he made the violin darker and death played sweeter ".

Tadeusz Różewicz dedicated his poem portrait Death is a Master from Germany to the memory of Paul Celan. It bears the subtitle "But what remains of the poet in poor time". The Polish original text also has the programmatic German-language title, which is repeated twice in italics in the poem. The quote accompanies Celan's meeting with Martin Heidegger.

music

In addition to Bertolt Brecht , Paul Celan became the “most widely written lyric poet of the 20th century”. According to Hartmut Lück, musicians in particular felt particularly challenged by musical titles such as Death Fugue or Narrowing , but no less by the “deeply moving linguistic power with which Celan, who escaped the Holocaust by chance, pressed the subject of the persecution of the Jews into lyrical images”. By 1991 ten compositions based on the death fugue had been created . The Gema database recorded 35 titles in 2010.

The later expatriate DDR - composer Tilo Medek set to music the poem in the 1960s as a work for soprano and sixteen-voice choir, which was internationally respected and honored. In 1972, the death fugue was set to music for mixed choir with baritone solo and organ by Hans-Jürgen von Bose , who dedicated this work to his grandfather Herbert von Bose , who was murdered by the SS in 1934 because of his opposition .

For Peter Ruzicka , the composer of the opera Celan. Music theater in seven drafts (libretto Peter Mussbach , 2000), Celan's poetry is at the center of his work. The death fugue for voice, speaker, chamber ensemble and tape (1969/70) by the then twenty-year-old artist marked the beginning of his musical exploration of Celan's work. In a letter dated July 7, 1955 Hanne and had Hermann Lenz Paul Celan to the setting of Death Fugue by Wilhelm Keller out. A later arrangement for five male voices can be found together with other poems by Celan and other authors in his sound and vocal composition Carmina Humana . It was premiered in June 1994 by the Ensemble Singer Pur at the German Music Competition in Bonn.

In England, Celan's poems were set to music by Harrison Birtwistle . In the composition Pulse Shadows. Meditations on Paul Celan for soprano, string quartet and ensemble (1996), a nine-movement song cycle of poems is juxtaposed with another nine-movement instrumental cycle that meditates reflectively on the texts. Only the first and last movements of the 18-movement cycle are directly bracketed with the singing voice. Birtwistle saw the composition as an architectural frieze whose individual sound blocks relate to one another. In the penultimate frieze , the fugue of death , Birtwistle completely dispensed with the singing voice and instead lets the quartet play a splintered fugue.

Visual arts

For Theo Buck, the visual power of Celan's poetry is one reason why visual artists grapple with his poetry and develop the language of their images from the linguistic images of the poet. The “pictorial reflection” on the leitmotifs of the poem broadens the scope of interpretation because it has an effect on the text, in line with Franz Mons's formulation : “Text becomes image becomes text”. In many of these works, “written quotations or characters similar to writing” are included in such a way that they become “an integral part of the image compositions”. This is particularly true of the death fugue , when artists like László Lakner or Anselm Kiefer take up the “crystallization metaphors of Celan's poem” and literally inscribe the images as quotations. László Lakner presented a series of four large-format pictures on the subject of “Black Milk” in the context of his “Recitations” cycle from the 1980s, in which the quotation of this guiding metaphor was sprayed onto the colored background of the entire surface.

The Celan Handbook lists Anselm Kiefer's work as the “most prominent artistic oeuvre” of Celan's texts, which “largely” starts from the fugue of death . Between 1980 and 1983, Kiefer dealt intensively with Celan's poem as part of his examination of the myths of German history, especially those of fascism . The exhibition catalog of the Folkwang Museum Essen (1982) shows 15 Margarethe and 9 Sulamith paintings on the allegorical female figures in the closing verses. Kiefer developed his series of images from the naked female figure with oversized hair, who is exposed to a gloomy landscape of civilization, to an apocalyptic landscape of devastated and burned fields in which only a bent strand of yellow straw stuck to Margaret's golden hair or the outline of a broken one Mandorla remembers. A large black arc of shadows is often painted parallel to this straw collage. This “presence of black” has been interpreted “as an indirect presence of Sulamith”, especially since, conversely, straw is also found in the painting material of the Sulamith pictures. In these adaptations, dense diagonal black-white-gray hatching of the hair on a blackened landscape reminds of the destruction of the Jewish Sulamith.

Two lead books with the title Sulamith come from 1990 . This time, large-format soldered, shimmering colored lead plates, on which a lock of human hair and ashes are fixed, served as relief-like image carriers. The concrete materials and the engraved name “Sulamith” are, according to Buck, “the only 'realities' of aesthetic construction”. This material basis represents a reflex of the National Socialist extermination of the Jews. With the relic of the woman's hair and traces of ashes, Kiefer not only cites the final verse "Your ashen hair Sulamith", he also interprets it as a relic of remembrance.

The work Sulamith from 1983 reduces the poem to its last word. Outside the field of vision, the name “Sulamith” is scratched in with tiny white characters in the picture of an almost lightless interior. The architectural lines of the vault and the perspective of the floor slabs run towards the sevenfold flames of the menorah of a small "altar" in the background. The painting is modeled on a crypt planned by Wilhelm Kreis for the graves of German war heroes of the “High Command of the Army” . “Sulamith”, however, is not a “peripheral memory”, but the symbolic beginning of an imaginary list of victims: the beginning of a book of the dead , such as in the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem. According to Buck, with this version, Kiefer dismantles the “Nazi Heroes' Crypt” and “Heroes Honor” and transforms the place into a “ skull ”. In the recess of the Sulamith figure her suffering is revealed in the final analysis.

From the Munich artist Beate Passow originated installation A man living in the house .

Cultural references

According to Claus-Michael Ort, no other German-language poem from the post-war period became part of a public canonization to a comparable extent , which elevated it as a whole and individual pictorial formulas to the linguistic expression of the Holocaust. Metaphors such as “Death is a Master from Germany” or “Your aschenes Haar Sulamith” became the title of documentaries and anthologies. This is how Lea Rosh and Eberhard Jäckel called their 1990 documentary about the murder of European Jews Death is a Master from Germany . The punk band Slime referred to Celan's poem in their eponymous title. Rüdiger Safranski called his biography about Martin Heidegger a master from Germany . In the foreword he explains the title quote: The thinker from the school of the mystic Meister Eckhart has "through his political activities also something of that 'master from Germany' that is mentioned in Paul Celan's poem." The anthology German history after 1945 leaves the death fugue immediately follows the photo of Willy Brandt's kneeling in Warsaw in front of the memorial of the heroes of the ghetto . In 1987 the writer and filmmaker Frieder Schuller shot the feature film In the South of My Soul in Romania, which deals with the creation of the poem Death Fugue and Paul Celan's years in Bucharest.

literature

expenditure

- The sand from the urns. A. Sexl, Vienna 1948.

- Poppy seeds and memory. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt , Stuttgart 1952.

- The sand from the urns. Poppy seeds and memory. Edited by Andreas Lohr with the collaboration of Holger Gehle in conjunction with Rolf Bücher. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003 (= Paul Celan, Werke. Historisch-Kritische Ausgabe , I. Department, 2nd / 3rd volume).

- Death joint. With a comment by Theo Buck. 2nd Edition. Rimbaud, Aachen 2002, ISBN 3-89086-795-2 .

- The poems - annotated complete edition in one volume. Edited and commented by Barbara Wiedemann. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-41390-2 ; TB edition: 2005, ISBN 3-518-45665-2 .

Secondary literature

Text interpretations

- Alwin Binder : The masters from Germany. To Paul Celan's death fugue . In: Germanica . 21 [ From Celan to Grünbein. On the situation of German poetry in the late twentieth century ]. 1997. pp. 51-71.

-

Theo Buck : Paul Celan: "Death Fugue". In: Hans-Michael Speier (Ed.): Poems by Paul Celan. Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-017518-6 , pp. 9-27.

- dsb .: The “death fugue” or poetry after Auschwitz. In: mother tongue, killer language. Celan studies 1. Rimbaud, Aachen 1993, ISBN 3-89086-917-3 , pp. 55-92.

- dsb .: death fugue. Commentary Theo Buck; 5 gouaches by KO Götz . Rimbaud, Aachen 1999 Series: Texts from the Bukowina, Vol. 7, ISBN 3-89086-795-2 .

- Wolfgang Emmerich : Paul Celan's path from the “beautiful poem” to the “gray language”. The skewed reception of the “death fugue” and its consequences. In: Hans Henning Hahn & Jens Stüben Ed .: Jewish authors from East Central Europe in the 20th century. Frankfurt 2000, pp. 359-383.

-

Jean Firges : " I cross the Acheron ..." Introduction to the poetry of Paul Celan. Four motifs from Paul Celan's poetry: travel, death, dream, melancholy. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1998, ISBN 3-86057-067-6 , pp. 85-96.

- Streamlined version: Paul Celan: The two doors of the world. Poetry interpretations. Exemplary series Literature and Philosophy 3, Sonnenberg, Annweiler 2001, ISBN 3-933264-06-5 , pp. 24–33.

- Did Paul Celan's "death fugue" become doom? In Bruno Kartheuser, ed .: Kraut und Pflaster. For the 25th birthday of the literary magazine Krautgarten . Edition Krautgarten, St. Vith 2007, ISBN 2-87316-026-8 , pp. 31–37.

- John Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography. CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-45919-6 .

- Heinz Forster & Paul Riegel: The Post-War Period 1945–1968. German literary history. Vol. 11th series: dtv 3351, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-423-03351-7 , pp. 405-422.

- Eric Horn: Poetry after Auschwitz. Paul Celan's "Death Fugue". In: Gerhard Rupp (Ed.): Classics of German literature. Epoch signatures from the Enlightenment to the present. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1999, ISBN 3-8260-1517-7 , pp. 251-271.

- Wilfried Ihrig : Celan's death fugue in the wilderness. In: Ders .: Paul Celan and ... Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-7485-5229-1 , pp. 69–81.

- Helmuth Kiesel & Cordula Stepp: Paul Celan's Horror Music. In: Udo Bermbach & Hans Rudolf Vaget Hgg .: Baptized on music. Festschrift for Dieter Borchmeyer . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3398-1 , pp. 115-131.

- Ruth Klüger : Paul Celan: The death fugue. In dsb .: painted window panes. About lyric. Wallstein, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-89244-490-9 , pp. 127-139.

- Lech Kolago: Paul Celan: Death fugue. In: Musical forms and structures in the German-language literature of the 20th century. Müller-Speiser, Anif 1997, ISBN 3-85145-040-X , pp. 201-208.

-

Dieter Lamping : From Kafka to Celan. Jewish Discourse in 20th Century German Literature. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-525-01221-7 , pp. 99-112.

- dsb .: Poems from Auschwitz, about Auschwitz. In: Poetry of the Apocalypse . Published by Gerhard R. Kaiser, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1991, ISBN 3-88479-570-8 , pp. 237-255.

- dsb .: Are poems about Auschwitz barbaric? About the humanity of Holocaust poetry. In: dsb .: literature and theory. About poetological problems of modernity. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-525-01217-9 , pp. 100-118.

- Otto Lorenz: Poems after Auschwitz or the perspective of the victims . In: Inventory of contemporary literature . Published by Heinz Ludwig Arnold , edition text + kritik , Munich 1988, ISBN 3-88377-284-4 , pp. 35–53.

- Wolfgang Menzel: Celan's poem "Death Fugue". The paradox of a fugue about death in Auschwitz. In: Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift, Neue Episode 18, 1968, pp. 431–447.

- Peter Horst Neumann : Beauty of horror or horror of beauty? In: History in a Poem. Texts and interpretations. Ed. Walter Hinck. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1979 (= edition Suhrkamp 721), ISBN 3-518-10721-6 , pp. 229-237.

- Thomas Sparr : Time of the death fugue. Reception of the lyrics by Nelly Sachs and Paul Celan . In: Stephan Braese, Holger Gehle, Doron Kiesel, Hanno Loewy (eds.): German post-war literature and the Holocaust . Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 1998, ISBN 3-593-36092-6 , pp. 43-52.

- Thomas Sparr: Death fugue - biography of a poem. DVA, Munich 2020, ISBN 978-3-421-04787-8 .

- Heinrich Stiehler: The time of the death fugue. At the beginning of Paul Celan's . In: Akzente , Heft 1 (1972), pp. 11-40.

Celan's death fugue in contemporary music

- Robert Adlington: In the Shadows of Song. Birtwistle's Nine Movements for String Quartet . In: Peter O'Hagan (Ed.): Aspects of British Music of the 1990s . Ashgate, Aldershot 2003, ISBN 978-0-7546-3041-8 , pp. 47-62.

- Axel Englund: “Strokes the violins darker.” Berio and Birtwistle in Dialogue with Celan . In: Siglind Bruhn (Ed.): Sonic Transformations of Literary Texts. From Program Music to Musical Ekphrasis . Pendragon, Hillsdale 2008, ISBN 978-1-57647-140-1 , pp. 119-41.

- Ute Jung-Kaiser : “We are digging a grave in the air” ... On the (im) possibility of aesthetic education in the face of the Shoah. In: Michaela Schwarzbauer and Gerd Hofbauer (eds.): Polyesthetics in the 21st century: Chances and limits of aesthetic education . Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-56806-4 , pp. 149-173.

- Arnold Whittall: The Mechanisms of Lament. Harrison Birtwistle's “Pulse Shadows” . In: Music & Letters, No. 1 (1999), pp. 86-102.

Celan's death fugue in the fine arts

- Theo Buck: Imagery. Celan motifs by Lázló Lakner and Anselm Kiefer . Celan Studies II. With three illustrations each by Lázló Lakner and Anselm Kiefer. Rimbaud Verlag, Aachen 1993, ISBN 3-89086-883-5 .

- Andreas Huyssen: Anselm Kiefer: Myth, Fascism and History . In: Art and Literature after Auschwitz . Edited by Manuel Köppen. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-503-03070-0 , pp. 137-150.

- Walther K. Lang: Death and the Image. Evocations of death in contemporary art 1975–1990 . Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1995, pp. 211-228 (Anselm Kiefer and the death fugue by Paul Celan). ISBN 3-496-01144-0 .

- Andréa Lauterwein: Anselm Kiefer / Paul Celan. Myth, Mourning and Memory . With 157 illustrations, 140 in color. Thames & Hudson, London 2007. ISBN 978-0-500-23836-3 (with detailed text interpretation and rich image material on Kiefer's examination of the death fugue).

Web links

- Reading of the death fugue by Paul Celan on lyrikline.org

- Media and art project with text of the poem

- Revealed: For the first time, the sources from which Paul Celan wrote his death fugue are revealed. By Barbara Wiedemann in: Die Welt from October 9, 2010.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c The full text of the poem, which cannot be reproduced here for copyright reasons, with a reading by Paul Celan can be found at Paul Celan: Todesfuge on lyrikline.org .

- ^ Helmuth Kiesel , Cordula Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik . In: Udo Bermbach , Hans Rudolf Vaget (Hrsg.): Baptized on music. Festschrift for Dieter Borchmeyer . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3398-1 , pp. 115–131, here p. 117; with detailed discussion of fugal elements.

- ↑ On this Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , pp. 120–122, who speak out in favor of the third interpretation.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Klüger: Paul Celan. Death fugue , p. 130.

- ↑ Paul Celan to Herbert Greiner-Mai , February 23, 1961, here quoted from Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , p. 117.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , p. 19.

- ↑ See: Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , pp. 120–121.

- ↑ On the (seldom named as such) Amphibrachys in Celan cf. z. B. Christoph Perels: On Paul Celan's poem "Frankfurt September" . In: Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift 54 (1973), pp. 56–67, here p. 61.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , pp. 18-20.

- ↑ Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , p. 116.

- ↑ Firges: “I am crossing the Acheron ...” , p. 90.

- ↑ See section: Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , pp. 20-22.

- ↑ Kurt Ernenputsch, Boger was afraid of poison , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , June 15, 1964. Quoted and commented in: Paul Celan: Die Gedichte . Edited and commented by Barbara Wiedemann. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005 (= Suhrkamp Taschenbuch 3665), ISBN 3-518-45665-2 , p. 608.

- ↑ Quoted from: Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , p. 22.

- ↑ Compare: Harald Weinrich : Semantik der kühnen Metaphor [1963]. In: Anselm Haverkamp (Ed.): Theory of Metaphor . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1996, ISBN 3-534-13152-5 , pp. 316–339, here pp. 326–328.

- ↑ In the language of the murderer. A literature from Chernivtsi, Bukowina . Exhibition book. Developed by Ernest Wichner and Herbert Wiesner. Literaturhaus Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-926433-08-6 , p. 163 (with illustrations and text examples).

- ^ Wolfgang Emmerich: Paul Celan . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-50397-2 , p. 53.

- ^ Buck: Mother tongue, murder language , p. 74.

- ↑ Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , p. 121.

- ^ A b c John Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 69.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , p. 24.

- ↑ Lang: Death and the Image , p. 213.

- ^ Neumann: Beauty of Horror or Abomination of Beauty , p. 236.

- ↑ Lang: Death and the Picture , p. 213 and Buck: Mutterssprach, Mörderssprache , p. 75.

- ↑ Buck: Mother tongue, murder language , p. 75.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , pp. 24-25.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen: The chamber music. The new genre style: 1824–1826 In: Walther Dürr, Andreas Krause (ed.): Schubert-Handbuch. Metzler, Stuttgart 2010, p. 490.

- ↑ John Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 61.

- ^ Forster, Riegel: The post-war period 1945–1968. German History of Literature, Volume 11 , p. 410.

- ^ Lamping: From Kafka to Celan . Pp. 99-112.

- ^ Lamping: From Kafka to Celan , p. 106.

- ↑ cardiac time. Ingeborg Bachmann – Paul Celan. The correspondence . Suhrkamp-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-518-42033-1 , p. 127.

- ↑ Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , p. 123.

- ↑ See section Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , p. 20.

- ↑ Quoted from: Paul Celan: Die Gedichte . Annotated complete edition. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag 2005 (= Suhrkamp Taschenbuch 3665), ISBN 3-518-45665-2 , p. 608.

- ↑ a b Firges: I cross the Acheron ... , p. 92.

- ↑ Quoted from Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 49.

- ↑ See section Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , pp. 23-25.

- ↑ Peter von Matt : How is the gold so darkened . In Marcel Reich-Ranicki (ed.): Hundred poems of the century . Insel, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-458-17012-X , pp. 306-308.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celans 'Todesfuge' , p. 23.

- ↑ John Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 66.

- ↑ a b Peter Horst Neumann: Beauty of horror and abomination of beauty? , P. 234.

- ↑ Buck: Paul Celans 'Todesfuge' , pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Compare to this: Buck: Mutterssprache, Mörderssprache , p. 83.

- ↑ Firges: I cross the Acheron ... , pp. 65 and 91.

- ↑ For example: Firges: I cross the Acheron ... , pp. 91–92; Felstiner: Paul Celan. Eine Biographie , pp. 57–58, Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , p. 116; Emmerich: Paul Celan , pp. 51-52; Horn: Poetry after Auschwitz. Paul Celan's 'Death Fugue' , pp. 268-271.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , p. 25.

- ↑ Quoted from: Paul Celan: Die Gedichte . Annotated Complete Edition, p. 607.

- ↑ Paul Celan: The Meridian . Edited by Bernhard Böschenstein and Heino Schmull. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , p. 26.

- ↑ In Luther's translation: “We sat by the waters of Babel and wept when we remembered Zion. We hung our harps on the willows that are there. For there welcomed us singing that held us captive, and be merry in our howling, 'Sing us one of the songs of Zion' "(! Ps 137.1-3 LUT )

- ^ Lamping: From Kafka to Celan , p. 112.

- ^ Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , pp. 36, 40, 42, 48.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , pp. 116, 118.

- ^ Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , pp. 57-58.

- ↑ Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , pp. 124–125.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , pp. 13-14.

- ^ Jean Bollack : Poetry against poetry: Paul Celan and literature . Wallstein, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-8353-0080-4 , pp. 50-52.

- ↑ Quoted from: Arturo Larcati: Final observations (PDF file; 190 kB). In: Klaus Müller-Richter, Arturo Larcati: Metaphor and History . Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-7001-3886-0 , p. 228.

- ^ Bollack: Poetry against poetry: Paul Celan and literature , p. 53.

- ↑ Celan Handbook, Life-Work-Effect . Edited by Markus May, Peter Großens, Jürgen Lehmann. Verlag JB Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2008, ISBN 978-3-476-02063-5 , p. 22.

- ↑ Text of the poem ER by Immanuel Weissglas .

- ↑ Quoted from: Barbara Wiedemann-Wolf: Antschel Paul - Paul Celan . Niemeyer, Tübingen 1985, ISBN 3-484-18086-2 , p. 80.

- ^ Bollack: Poetry against poetry: Paul Celan and literature , p. 47.

- ^ Jürgen Wertheimer : Paul Celan and the multilingual culture of Bukowina . In: Horst Förster, Horst Fassel (eds.): Cultural dialogue and accepted diversity? Romania and Romanian language areas after 1918 . Steiner, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-515-08295-6 , p. 183.

- ↑ Paul Celan: The Poems. New annotated complete edition. With the accompanying etchings by Gisèle Celan-Lestrange . Edited and commented by Barbara Wiedemann, Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, p. 688.

- ↑ a b Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 53.

- ^ Buck: Paul Celan: Todesfuge , pp. 15-16.

- ↑ John Felstiner, Paul Celan. A biography , p. 53.

- ^ Heinz Ludwig Arnold : The group 47 . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2004, ISBN 3-499-50667-X , p. 76.

- ^ Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 98.

- ^ Arnold: Die Gruppe 47 , p. 77.

- ↑ Paul Celan: Fugue of Death. With a comment by Theo Buck . 2nd Edition. Rimbaud, Aachen 2002. ISBN 3-89086-795-2 , p. 85.

- ↑ Erich Fried or Andreas Donath, compare: Celan-Handbuch , pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Quoted from: Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 106.

- ↑ Helmuth de Haas: Poppy and memory . In: About Paul Celan . Edited by Dietlind Meinecke. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1970 (= edition suhrkamp 495), pp. 31-34.

- ↑ Paul Schallück : Black milk of the morning . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of April 25, 1953.

- ^ Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 56.

- ^ A b Hans Egon Holthusen: Five young lyric poets . In: Dsb .: yes and no. New critical attempts . R. Piper & Co Verlag, Munich 1954, pp. 124-165, p. 164.

- ^ Sparr: Time of the 'death fugue'. Reception of the poetry by Nelly Sachs and Paul Celan , p. 45.

- ^ Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 115.

- ^ Ute Harbusch: Opposite translations: Paul Celan's transmissions of French symbolists . Wallstein, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-881-7 , p. 33.

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno: Cultural Criticism and Society . In: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 10.1: Cultural Criticism and Society I, “Prisms. Without a mission statement ". Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-518-07172-6 , p. 30.

- ↑ Klüger: Paul Celan. 'Death Fugue' , p. 134.

- ↑ Kiedaisch: Poetry after Auschwitz ?, P. 11.

- ↑ Wolfdietrich Schnurre: The shadow photographer. Notes , pp. 454–457: Thirteen theses against the claim that it is barbaric to write a poem after Auschwitz . Paul List Verlag, Munich 1978, 5th and 6th thesis.

- ↑ Celan Handbook , p. 259.

- ^ Robert Weninger: Disputeable literati. Controversies and scandal in German literature from Adorno to Walser . Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51132-5 , p. 38.

- ^ Lamping: From Kafka to Celan , p. 104.

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno: Aesthetic Theory . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 3-518-27602-6 , p. 419.

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno: Negative Dialektik , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 3-518-06572-6 , p. 355.

- ↑ Kiesel, Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , p. 128.

- ↑ Celan Handbook , pp. 260 and 274.

- ↑ Engführung , verses 132 and 133. In: Paul Celan: Die Gedichte . Annotated complete edition. Edited and commented by Barbara Wiedemann. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003 (= st 3665), ISBN 3-518-45665-2 , pp. 113-118.

- ↑ Quoted in: Jürgen Lehmann (Ed.): Commentary on Paul Celan's 'Sprachgitter' . Heidelberg, Universitätsverlag Winter 1997, ISBN 3-8253-5136-X , p. 478.

- ↑ Quoted from: Jürgen Lehmann (Ed.): Commentary on Paul Celan's 'Sprachgitter' , p. 25.

- ^ Neumann: Beauty of horror or abomination of beauty? , P. 231.

- ↑ Lamping: From Kafka to Celan , pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Quoted in Lamping: Von Kafka bis Celan , p. 110.

- ^ Lamping: From Kafka to Celan , p. 111.

- ^ Walter Müller-Seidel : Problems of literary evaluation. About the scientific nature of an unscientific topic . Metzler, Stuttgart 1965, p. 176.

- ↑ Müller-Seidel: Problems of literary valuation, p. 177.

- ↑ Quoted in Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 291.

- ↑ Müller-Seidel: Problems of literary valuation , pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Müller-Seidel: Problems of literary valuation , p. 180.

- ^ Neumann: Beauty of horror or abomination of beauty? , P. 236 .; quoted by Dieter Lamping: Are poems about Auschwitz barbaric? About the humanity of Holocaust poetry . In: Dsb .: literature and theory. Poetological Problems of Modernity . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, ISBN 3-525-01217-9 , pp. 100–118, here p. 117.

- ^ Lamping: Are poems about Auschwitz barbaric? On the humanity of Holocaust poetry , especially pp. 106–118.

- ^ Lamping: Are poems about Auschwitz barbaric? On the humanity of Holocaust poetry , p. 110.

- ^ Lamping: Are poems about Auschwitz barbaric? On the humanity of Holocaust poetry , p. 113.

- ^ Lamping: Gedichte nach Auschwitz, about Auschwitz , p. 240.

- ^ Gert Mattenklott: On the representation of the Shoah in German post-war literature . In: Jewish Almanac 1933 of the Leo Baeck Institute . Published by Jakob Hessing. Frankfurt am Main 1992, pp. 26–34, here p. 31.

- ↑ Lorenz: Poems after Auschwitz or The perspective of the victims , p. 39.

- ^ Lamping: Are poems about Auschwitz barbaric? On the Humanity of Holocaust Poetry , pp. 106–118, cites and interprets the examples. Compare the anthology with the programmatic title: Dieter Lamping (Hrsg.): Dein aschenes Haar Sulamith. Poetry about the Holocaust . Piper, Munich and Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-492-11506-3 , with the full, translated texts and other examples.

- ^ Lamping: Are poems about Auschwitz barbaric ?, P. 111.

- ^ Lamping: Are poems about Auschwitz barbaric ?, P. 116.

- ^ The Value of Holocaust Poetry in Education , Yad Vashem .

- ^ Felstiner: Paul Celan. A biography , p. 299.

- ↑ Christoph Jamme, Otto Pöggeler : The glowing blank text . Fink, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7705-2810-7 , p. 70.

- ↑ Jörg Thunecke: German-speaking Exillyrik from 1933 to the post-war period Rodopi, Amsterdam 1998, ISBN 90-420-0574-2 , p. 367.

- ↑ Dieter Lamping: We live in a political world. Poetry and Politics since 1945 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 3-525-20859-6 , p. 37.

- ↑ Winfried Freund: Deutsche Lyrik. Interpretations from the baroque to the present . Fink, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-7705-2649-X , p. 179.

- ^ Wolfgang Emmerich : Paul Celan . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1999, ISBN 3-499-50397-2 , p. 7.

- ↑ Quoted from: Weninger: Streitbare Literaten , p. 32.

- ↑ Wulf Kirsten (Ed.): “The easily vulnerable is constant”. Poems in German from Nietzsche to Celan . Ammann Verlag, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-250-10535-0 .

- ↑ Kirsten (Ed.): “The easily vulnerable is constant” , pp. 932–933.

- ↑ Klüger: Paul Celan. 'Death Fugue' , p. 135.

- ↑ Reading of the death fugue by Paul Celan on lyrikline.org .

- ^ Helmuth Kiesel, Cordula Stepp: Paul Celans Schreckensmusik , p. 127.

- ↑ a b Claus-Michael place: Remembering the “unspeakable”. On the poetic topic of the Holocaust from Celan to Eisenman . In: Hans Krah (Ed.): All-Gemeinwissen. Cultural communication in popular media . Ludwig, Kiel 2001, ISBN 3-933598-22-2 , pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Quoted from: Aleida Assmann : The long shadow of the past. Culture of remembrance and politics of history . Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-406-54962-5 , p. 165.

- ↑ Celan Handbook, p. 362.

- ↑ Compare: Marbacher Magazin 95/2001; Marie Luise Kaschnitz 1901–1974 on her 100th birthday , pp. 51–52; and above all: Paul Celan, Hanne and Hermann Lenz: Correspondence . With three letters from Gisèle Celan-Lestrange. Edited by Barbara Wiedemann (among others). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2001.

- ^ Marie Luise Kaschnitz: Collected works . Edited by Christian Büttrich and Norbert Müller. Fourth volume. The stories. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt 1983, pp. 48–56.

- ↑ Marbacher Magazin 95/2001, p. 52.