Büdinger forest

| Büdinger forest | ||

|---|---|---|

| Highest peak | Hammelsberg ( 416 m above sea level ) | |

| location | Wetterau and Main-Kinzig districts , Hesse | |

| Part of the Greater Region (3rd order) | Odenwald, Spessart and Südrhön | |

| Classification according to | Handbook of the natural spatial structure of Germany | |

|

|

||

| Coordinates | 50 ° 16 ' N , 9 ° 14' E | |

| rock | Basalt and red sandstone | |

| surface | 201.68 km² | |

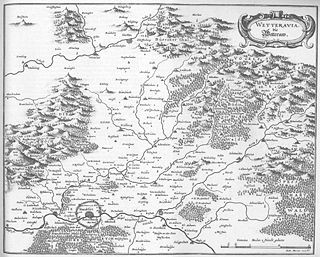

The Büdinger Forest is a forest landscape, a natural area in the southeast of Hesse . Broken by roads or rivers, there are further extensive forests in the north, east and south ( Spessart ). The northwestern smaller part belongs politically to the Wetteraukreis , the larger southeastern part to the Main-Kinzig-Kreis ; historically and politically the area belonged to the Wetterau .

The Büdinger Forest has little to do with Büdingen apart from the naming. Historically, as the imperial forest, it was an accessory to the royal palace in Gelnhausen . However, it was already in the Middle Ages as an imperial fiefdom to the Burgraves of Gelnhausen (and at the latest between 1461 and 1511 to Ludwig II, Count of Ysenburg , Lord of Büdingen and Birstein) and after more than 300 years under the administration (1812, after the allodification , the authenticity of the allodification certificate is disputed) came into the property of the Counts of Ysenburg and Büdingen or their special lines (subsidiary lines). The land register owner has been the forest company Constantia Forst GmbH since 2006 .

The Büdinger Counts (since 1725 three special lines : in Büdingen , in Meerholz and in Wächtersbach ) were members of the Wetterau Counts Association at the time of the old German Empire and after its dissolution after 1803 in the 19th century they were rank lords between 1806 and 1813 in the Principality of Isenburg and from 1816 in the two states of the German Confederation under the Grand Dukes of Hesse-Darmstadt and the Electors of Hesse-Kassel (after the unification - annexation - of the Electorate of Hesse with Prussia, from 1868 to the Prussian province of Hesse-Nassau ) and the Prussian kings.

After the state upheaval in 1918/19 (as a result of the November Revolution ), the northwestern part remained in the Büdingen district ( Upper Hesse province of the People's State of Hesse ) and the southeastern part in the Gelnhausen district (Hesse-Nassau province of the Free State of Prussia ) until 1944 and after the dissolution of this province from July 1, 1944 to the Prussian province of Nassau (adaptation to the structure of the Reich defense districts ); the district membership did not change even after the formation of Greater Hesse on September 18, 1945 and Hesse (1946) as a new state in the US occupation zone (the occupation statute did not end until May 5, 1955). The district affiliation remained unchanged until the municipal area reform in 1972/74, after which the Büdingen district in the Wetterau district and the Gelnhausen district in the Main-Kinzig district were added .

Limits

The boundaries of the natural spatial Büdinger Forest are different from those of the historical Reichswald:

In terms of natural space, the Büdinger Forest denotes the area south of the continuous basalt shield of the Vogelsberg to the valley of the Kinzig between Steinau (east) and Gelnhausen (south) and over the eponymous town of Büdingen protruding to the northwest to the area of Stockheim and Glauburg . Although orographically the Vogelsberg-Südabdachung, the Büdinger Wald (north of the Kinzig) geologically represents a north-westerly continuation of the adjoining sandstone spike to the south-east .

The landscape, historically known as the Büdinger Forest, differs slightly from this and does not extend quite as far, especially in the north-west and east, but is somewhat more extensive in the central part. It covers the area within the boundaries of the former Reichslehens ( forest of the realm ) under the counts (after the fall of the old German Empire as landlords in Büdingen in 1840 and princes in Wächtersbach in 1865 ) of Ysenburg and Büdingen between the cities of Büdingen, Wächtersbach and Gelnhausen. Its boundaries are essentially historically determined by the Grenzweisum of 1377. They are watercourses: In the north the Seemenbach, which now flows through the town of Büdingen (in the Middle Ages, it was the southern boundary of the town), in the east the Bracht (municipality of Brachttal and town of Wächtersbach), in the south the Kinzig ; the western border is not exactly marked, but runs almost on the federal highway 457 north of Gründau-Lieblos to Büdingen.

The administrative division and allocation of the different parts of the forest was earlier (until the 20th century) to a lesser extent the villages in and around it as a community mark, and to a greater extent the various manor districts (the manorial [manor] farms and the Forest plots were assigned to unincorporated areas . Most of the manor districts were dissolved in the 20th century and incorporated into the municipal landmarks.

geography

Natural space

In terms of nature , the Büdinger Forest is classified as one of six main units (code number 143) of the Odenwald, Spessart and Südrhön group (14). The 201.68 km² natural area forms a fairly uniform structure and - as one of only very few main units in Germany - is not further divided into sub-units.

geology

Within the south-west German layer level country ( large landscape of the 2nd order), the Büdinger Forest - like most of the Odenwald-Spessart group - represents the layer level of the red sandstone . Zechstein deposits only come to light on the edge of the step . The Oberrotliegend step of the Ronneburg hill country adjoining it to the west is towered over by around one hundred meters.

The Breitenborn basalt quarry in Breitenborn A. W. (from 1972 district of Gründau) was the largest in the old federal states with 143 hectares. In the meantime, parts are no longer used and are backfilled before renaturation .

The area is rich in sandstone quarries in the south. The fractures from Gründau-Lieblos via Gelnhausen to Wächtersbach are striking and can be seen from the railway (Frankfurt-Fulda) as well as from the federal highway 66 . Sandstone used to be quarried inside the forest, and basalt in Gettenbach (Eichelkopf) and Breitenborn .

Geologically, the smaller northern part is assigned to the Vogelsberg ( basalt ), the larger southern part to the Spessart ( sandstone ).

landscape

As the southern roof of the Vogelsberg , which is a few hundred meters higher , the Büdinger Forest is not a mountain range; but it clearly towers above Kinzig and Ronneburger hill country. The very recent uplift axis of the Büdinger Forest runs parallel to the edge of the step. It rises from 320 m in the west to 380 m. To the west of Wächtersbach, the greatest heights are around 420 m, while the plateau in the east of the Brachttal falls again by around 50 m. The eastern elevations are covered by flood basalts, which either represent isolated lobes or extend in a tongue-like manner from the Vogelsberg. On these igneous rocks mainly medium to shallow, stony soils have developed, which have a sandy-gritty to clay texture. The greater part of the Büdinger Forest, however, is taken up by the sandstone table of the plateau, which forms the base rock for the medium to deep loamy and loamy sands there. The valleys have an alluvial clay cover.

The deeply cut rivers and brooks coming from the Vogelsberg (see list below ) divide the wooded red sandstone into different ridges. The highest elevations are in the section between the Gründau and the Bracht , which extends south to the Kinzig valley ( Hammelsberg 415.6 m, Vier Fichten 406.2 m). In general, the core area lies between Seemenbach (north-west), Kinzig (south) and Bracht (north-east) and between Büdingen (north-west), Gelnhausen (south), Wächtersbach (south-east) and Wittgenborn (north-east). Starting from this base, which is 11 to 12 km in diameter, a 4 to 5 km wide strip extends perpendicular to the valleys to the north (north) west and a tapering strip along the right bank of the Kinzig to the north-east, from which a slightly wider red sandstone line extends at the Brachttal pulls north on both sides of the bank. Due to this conspicuous shape, the natural area can also be easily identified on aerial photographs, as it meets only island-like wooded areas in the west and north and the Kinzig valley in the south-east is also a narrow border wide unforested.

The contiguous forest area of the Büdinger Forest that characterizes the landscape today has an area of 8,500 hectares , which is in the municipal areas of Ortenberg (north), Kefenrod (smaller parts in the east north), Büdingen (center), Gründau (southwest of the center), Gelnhausen (South), Wächtersbach (east), Brachttal (north of it), Bad Soden-Salmünster (northeast) and Steinau an der Straße (extreme northeast). The forest is composed (2010) proportionally of the tree species beech (34%), spruce (29%), Douglas fir (11%), larch (9%), oak (6%), colored hardwood (3%) and other hardwoods ( 8%) together. The area of approx. 9250 ha (total) managed by Constantia Forst GmbH includes 300 ha of meadows, 125 ha of stone quarries, 35 ha of arable land, 25 ha of water, 500 km of paved forest paths and eight forest huts.

history

Reichswald

The Büdinger Forest has been a closed area since the Middle Ages. An establishment as a Reichsforst is set for the last third of the 12th century, at the same time with further Staufer foundations in the Wetterau and the building of the imperial palace Gelnhausen . The Hohenstaufen saw themselves as heirs of the Counts of Selbold (ancestral seat Langenselbold ), who are later also referred to as the Counts of Gelnhausen (died out in 1155). The medieval forest rights are described in detail in the Weisthum des Büdinger Wald in 1380 .

The Büdinger Forest was a forest assigned to the empire (similar to the other imperial forests, such as Aachen, Dreieich , Kaiserslautern, Kleve , Nuremberg , Unterelsaß). The wording in the forest wisdom daz das riche supreme merker sii ubir den walt ties in with the wisdoms of the other imperial forests and allows various conclusions to be drawn with regard to the details. The rights associated with the imperial fiefdom, especially the right to clearing , allowed the Lords of Büdingen to build a coherent area of dominion between Vogelsberg and Wetterau around the castles of Büdingen , Ortenberg and Staden in the north, and Wächtersbach and Gelnhausen in the south.

The Ysenburgers and the Trimbergers (extinct in 1376), who were no longer involved soon after, were named as lords in the WaldWEISum of 1380 . The right of the Ysenburger as the main heir of the Büdingen (Ludwig 1258-1302 or 1318 a son of Heinrich the Younger of Isenburg-Grenzau was married to Hedwig, the heiress of Büdingen) seems to be an office over the forest as a district of jurisdiction (in the earlier sense, as it is today in international law: administration and jurisdiction). Their main task was to protect the forest, without any possession or property in the current sense of the word. The forestry shows that the main rights of use lay with the forester and the twelve forest riders on horseback.

Only later was able to Isenburgern the rights (the fief) of the forester (by the family forester from Gelnhausen to bring) and the forester gradually itself and the forestry authority to acquire (territorial sovereignty, territorial violence). This process was completed by the end of the 15th century. For centuries, the second largest forest ownership in Hesse was the so-called sub-property of the counts and later princes of Ysenburg and Büdingen (after the county or principality was divided into the main parts: " Ysenburg and Büdingen in Büdingen ", " Ysenburg and Büdingen in Meerholz " and "Ysenburg and Büdingen in Wächtersbach ”). Only after the transfer of sovereignty ("exerceront tous les droits de souveraineté" ... exercise all sovereignty rights ... ) to Prince Carl Friedrich zu Isenburg in Offenbach (according to Article 24, Paragraph 11 of the Rhine Confederation Act of 1806: "sur les possessions des Comtés d´Isenbourg -Budingen, Waechtersbach et Meerholz “ ... about the possessions of the Counts of Isenburg-Büdingen, Wächtersbach and Meerholz ), the sovereign is said to have converted the fief into an allod (= family estate subject to no restrictions) of his landlords on December 31, 1812 through the allodification , later a family fideikommiss . Rather, the social situation of the residents of the eligible parishes had been aggravated by other circumstances. After two of the three “special lines” (secondary lines) died out, the forest (apart from the clearing for the forested villages) has been in one hand again since 1941 (Isenburg / Ysenburg and Büdingen / from 2006, after the bankruptcy, the Constantia forest company Forst GmbH). The borders of the former Reichswald have largely been preserved to this day.

Wild spell

In addition to the royal forest mark (Reichswald) of the Staufer from the Middle Ages, there was also a hunting and game ban ( Bannforst ) belonging to this forest , which went far beyond the boundaries of the Reichswald, but was nevertheless referred to as the Wildbann Büdinger Wald.

The boundaries of the ban forest are as follows: From the mouth of the Gründau into the Kinzig west of Langenselbold following the Kinzig upwards to the east to the mouth of the Salz near Salmünster . In the east, following the salt to the heights of the Vogelsberg in the court of Burkhards , from there to the west to the Nidder and following this down to the Nidder bridge to Altenstadt in the west. From there the border follows the "Roman pile ditch" ( Limes ) to the south to the confluence of the Gründau with the Kinzig. When it was first demarcated in the Middle Ages, the Wildbann area did not belong to the empire, but to very different lords, to a large extent also to the farmers of the villages, even though there were several manorial farms.

In the west, the Bannforst was only a few kilometers from the eastern border of the Dreieich Wildbanns (the Ysenburgs also acquired a large part of this fief in 1420), which in turn connected to other imperial forests and wildbans in the south and west. Immediately to the south was the Spessart, also Bannforst. The story shows similarities to the nearby former Reichsforst Dreieich (the northern part is now the Frankfurt City Forest ) and the wildbann surrounding it.

In the ban forest only the king or those appointed by him had the right to hunt, with the exception of wild animals (bears, boars, wolves), which anyone was allowed to kill. The foresters were responsible for pursuing the hunting offenses. If there were traces of grinding, the forest staff was allowed to pursue the wrongdoers to the gates of the four imperial cities Friedberg, Frankfurt am Main, Gelnhausen and Wetzlar. The area of responsibility of the various fiefdoms shows the size of the area of influence of the Büdinger Forest in the entire Wetterau.

Palaces and castles around the Büdinger Forest

In addition to the four moated castles in Büdingen , Wächtersbach , Gelnhausen and Spielberg, there are two other castles in the Büdinger Forest: once the courtyard , which was already mentioned in 1252 and 1377 ( Hube , the forest huts comprised 25 hectares of land with a house, barn and stable), one of the twelve riding horses Förster (until the end of the Middle Ages the low-nobility de Knusse forestry family ) in Gettenbach and the iron hammer (with blast furnace) built in 1707 , which was supposed to process the ore extraction from the Schächtelburg mining site (Neuenschmidten district of the Brachttal community).

A hunting lodge was built on the grounds of the Forsthof in Gettenbach between 1841 and 1857 , which housed an outsourced hospital from 1944 to 1957 (Orthopedic University Clinic Frankfurt am Main) and a home for the female Reich labor service during World War II . Since 1958 it was initially a rehabilitation center, today a dormitory for disabled people.

Eisenhammer Castle was built in 1723 as an administrative building for the iron industry. After being leased to Buderus for many years , a sawmill was built there in 1875, which later became a furniture factory. The castle is empty today (2011).

Forest use: timber rights and other authorizations

“In older times, forest law was also called (as a subjective right ) the legal authority to use wood, mast, pasture, litter, grass, pest, etc. in another forest. to exercise other uses or to be allowed to demand certain quantities of forest products from the forest owner annually or periodically (construction and timber depending on requirements, firewood allowances, fattening allowances, game allowances, etc.) ". The rights (formerly also called righteous, righteous or similar) of the "forested" villages (after the regional reform in Hesse in the 1970s mostly merged into newly created large municipalities) are of different nature, mainly grazing and foliage rights and timber rights .

Traditional forest use by the village population

- Food and clothing: berries, mushrooms and venison and hides

- House and yard: construction and firewood

- Livestock farming: leaves, grass, litter , “ plague chop ” for fertilization, forest pasture

The most important authorizations are specifically mentioned in the old documents:

- Right to forest pasture (Hutung)

- Pasture for cattle (for the most privileged villages Gettenbach , Hain-Gründau and Haitz in the period from 15 April to 15 June pasture on the three large pastures Heselersgraben , Rudolfisgraben and Steinulfisgraben )

- Driving in flocks of sheep and fattening pigs (Eckern, acorns, etc.),

- Driving in flocks of goose,

- Right to leaves as litter (straw substitute in stables) and a.,

- Right to collect certain softwood ( primeval wood ) and lying wood (storage wood) for personal use (firewood for heating in winter and cooking); mostly it was Shaped steady wooden excluded from the rights that belonged Eychenholtz ( oak ), Buchholtz ( Book ) Aernholtz ( maple ), Eschholtz ( ash ), Arnsbeumen ( serviceberry ) Kyrsbeumen ( cherries ), Appelbeumen ( apples ), Byrbeumen ( Pear ), Haselbaumen ( hazelnut ), Nuszbaumen ( walnut ), Erlinholtz ( alder ),

- Right to construction timber for personal use (oak logs for sleepers , runners, ridge columns , ridge beams ).

In detail, these authorizations had different designs, e.g. In the 19th century, for example, the residents of Gelnhausen, Gettenbach and Haitz were still allowed to “make” wood for six days, which from Breitenborn , Hain-Gründau u. a. only two days a week; Gelnhausen was allowed to pull or beat beechnuts and acorns from the trees with an iron pick ( sow tooth ), the other authorized persons were not even allowed to use wooden poles. There were also such special features in other forests with timber permits; This type of permissions seems to have existed not only in the German legal area (e.g. the wooden villages in the Stormarn district), but throughout Europe, e.g. B. also in the Muslim-dominated part. What they all had in common was that the rights could not be exercised on public holidays and not in the setting period from May 12th to June 12th and the rutting season ( rut ) from September 12th to October 12th.

The circle of those entitled :

The forest dwelling of 1380 names 13 forested villages (with different authorizations). The following five villages (which were within the boundaries of Weistum) had the most extensive rights:

Gettenbach , Haitz , Hain-Gründau , Husenbach (a submerged place) and (Ober-) Wolferborn .

Outside the boundaries of Waldweise were:

Allenrod, Büdingen (castle men and residents of the first settlement in front of the castle), Hitzkirchen ("this side of the brook"), Hellstein , Höfen (for Burgbracht "this side of the brook"), Kefenrod , Vonhausen (only the Frohnhof), (Unter-) Wolferborn .

The "Burg von Gelnhausen" is mentioned separately, meaning the small originally independent community around the Kaiserpfalz Gelnhausen (incorporated into the city of Gelnhausen at the end of the 19th century). Attention is drawn to the rights of the city of Gelnhausen itself. As early as 1755, the city reached a settlement with the Ysenburgers about their rights after centuries of sometimes violent conflicts.

Locations added later:

- Clearing settlements from the 13th to the 16th century: Helfersdorf , Hesseldorf , Leisenwald , Neuenschmidten (with Schächtelburg), Schlierbach , Spielberg , Streitberg , Wittgenborn and Wächtersbach,

- Targeted start-ups by the Counts of Isenburg: Breitenborn (glassworks) and Waldensberg ( Waldensian settlement),

- Equal opportunities for the places Udenhain and Weilers (left of the Bracht, outside the Weistumsgrenzen) and Wirtheim (left of the Kinzig, Kurmainzisch and outside the Weistumsgrenzen, district of Biebergemünd ),

- individual farms: Baumieser Hof, Bruderdiebacher Hof and Bruderdiebacher Mühle (outside the Weistumsgrenzen, today belong to the town of Langenselbold ), the Thiergarten and Salinenhof and the paper mill in Büdingen, the Hühnerhof (within the Weistumsgrenzen, district Gettenbach von Gründau), the Hof Kaltenborn (within the wisdom boundaries, Haitz von Gelnhausen district).

Forest use by industry and commerce

In the 18th and especially in the 19th century it was also used for industrial purposes. The proceeds from this did not benefit the subjects with old rights, they went exclusively to the new authorizations created since the beginning of the 19th century, to the owners (absolute real right ):

- Construction (house, industrial and railway construction): lumber

- Mining: pit wood

- Soap factories, glassworks, bleaching: potash

- Lime and brick factories, breweries, salt pans: firewood

- Iron industry, smelters, hammer mills : charcoal

- Tanneries: Lohe (oak bark, etc.)

Replacement of rights

In the 19th century, almost all German states tried to “replace” the rights from the time of the old empire . The old empire collapsed in 1806 with the resignation of the last German emperor and in its place a number of sovereign states of the modern type emerged between the Rhine and Elbe (in the sense of Napoleon , who was also the protector of these states and the federation they formed in Paris had): the states of the Rhine Confederation . The state to which the Büdinger Forest belonged was the Principality of Isenburg . Whose sovereign is to the forest in 1812 allodifiziert have and its cousins, the heads of isenburgischen "special lines", the Count of Ysenburg and Büdingen ( in Budingen , in the sea timber and in Wächtersbach , as they called themselves later) property transferred. After the fall of this state in 1815, Isenburg was divided between Hessen-Darmstadt and Hessen-Kassel in 1816 . The legal basis for the detachment was in the Grand Duchy of Hesse (to the northwestern part of the Büdinger forest since 1816 belonged to) the meanness division -order of 1814, in Prussia in 1867 annexed (which included the southeastern part of the forest) Kurhessen was the Prussian Regulation of 1867 and the amendment and amendment law to the ordinance of July 25, 1876. In 1880, “theoretically” 3333 families (= approx. 12,000 inhabitants) were entitled, whose needs were calculated as 17–20 cubic meters of loose wood. According to Prussian law, primarily a monetary compensation was provided, according to the law of Hessen-Darmstadt a division of the forests burdened with the rights. After the negotiations in the replacement commissions, there were 17 recesses in the years 1879 to 1889. Before the supplementary law of 1876, there were also forced replacements through decisions of the replacement commissions.

Bankruptcy and end of Ysenburg property

In 1989 Otto Friedrich Fürst zu Ysenburg and Büdingen brought the Büdinger Forest into a forest enterprise Fürst zu Ysenburg und Büdingen GbR , further shareholders were his sons Johann Ernst and Christian Albrecht and his grandson Kasimir Alexander. Shortly before Otto Friedrich's death, they also acquired his shares. Later the shares of Otto Friedrich's two sons were transferred to the grandson, who ran the forest management as a limited partnership (KG) . During this time, the Büdinger Forest was loaned beyond its market value.

In 2005 insolvency proceedings were opened against the assets of the Fürst zu Ysenburg and Büdingen GbR, Büdingen . The insolvency administrator refused to fulfill the recessions that had been concluded between 1879 and 1889. The timber rights have not been used since then. On May 31, 2006, the insolvency administrator sold the Büdinger Wald to ILAG-Forst GmbH , based in Frankfurt am Main, which later became Constantia Forst GmbH. Two investor families from Vienna are behind the specially founded GmbH .

In order to ensure the continuation of the settlements (recesses) concluded between the municipalities and the Ysenburg princes and the count in the years 1879 and 1889, for themselves and their beneficiaries (community members' property , § 119 Hessian community regulations (HGO) ) inexpensive or free wood from the In order to obtain Büdingen Forest, the city of Büdingen and the municipality of Kefenrod have reached a largely upright judgment before the Higher Regional Court in Frankfurt am Main after a legal dispute regarding the entry of the lot wood rights as a real burden in the land register for the forest of the Büdinger root part.

Infrastructure

Streets

Only a few traffic routes, apart from non-public logging routes, cut through the forest. A single road from Langenselbold up through the Gründautal leads to an older forester's house near the Weiherhof on the road between Wittgenborn and Waldensberg , now part of the city of Wächtersbach .

Old streets

A number of old roads led through the wooded area in Celtic times until the spread of modern art roads before around 1850 , which are no longer traffic routes today. Old roads are characterized by different criteria than the modern artificial roads: They do not lead through valleys, but over longer ridges (because of the wind not on the ridge, but on the upper slope and on the drier south side); they also do not lead through places, mostly directly to the destination and, if possible, avoiding unnecessary ups and downs. The following old roads lead through the Büdinger Forest:

Antsanvia : As a historic street, the Antsanvia leads through the northern Büdinger Forest, an old Franconian street that led from Mainz in the west to Eisenach and then to Leipzig and Warsaw in the east. The part that leads through the Büdinger Forest is also called Reffenstraße , or Recht Kinzigstraße . In 1945 (when the US troops had already occupied the Gründau and also the villages north of Wächtersbach on the "Platte") it was once again the scene of warlike events. At this time, part of the 9th SS Mountain Division North, who had returned from Finland via Norway (as a so-called wandering basin), made their way to the Vogelsberg, and on April 2, 1945 (Easter Monday), they caught the weak American garrison of Waldensberg by surprise the goal of fighting their way further south from there, but this was thwarted by the US troops advancing from all sides (including a tank division that advanced on Reffenstrasse). Waldensberg and part of Leisenwald "went up in flames".

Bergstrasse : Anyone wishing to travel from Gelnhausen to Büdingen had to use an old road through the Büdinger Forest, the Bergstrasse , or travel via the villages of Lieblos , Mittel-Gründau , Vonhausen and Lorbach until around 1840 .

Rennstraße : It leads from Glauberg to Franconia and crosses the Büdinger Forest between Breitenborn and Wächtersbach in the forest area of Gettenbach and, after crossing the Kinzig, gains the height between Orbbach and Aufenau .

Gelnhäuser Straße : Another old street is Gelnhäuser Straße from Gelnhausen via Wittgenborn, Streitberg and Hitzkirchen to the north.

Jewish lane : The Jewish residents from Breitenborn are said to have used this lane to come to the synagogue in Gettenbach and to bring their deceased to the Jewish cemetery that still exists there today . However, this fact has not been proven and is unlikely because of the detour.

Totenweg : In this way, the residents of Haitz and the Kaltenborn farm had to take their deceasedover the mountain and through Gettenbach to the cemetery at the mountain church in Niedergründau . They also had to walk the arduous and long way to the church services. As Reformed ( Calvinists ) they were not allowed to pass through the Lutheran Gelnhausen.

In contrast, the modern art road ( Chaussee , today's B 457) leading from Lieblos to Büdingen on the western edge of the forest was only built around 1840. The road construction project meant that a road was built from the Hühnerhof via the village of Gettenbach to the Eichelkopf (386 m above sea level), because there was a basalt quarry there at that time. This break should not only provide the building material ( gravel , grit and paving stones ) for the new Chaussee, but also for the structural maintenance of the Chaussee from Langenselbold to Gelnhausen in the valley of the Kinzig valley (above the Kinzig valley - on the heights north of the Kinzig) an old street, the Via Regia or the Reiches Straße from (Paris via) Mainz, Frankfurt am Main, to Leipzig (and on to Breslau and Novgorod )).

Power lines

The forest is cut by a route built in 1952 for a 220 kV high-voltage line coming from the Staudinger power station from the west from the Hain-Gründau field boundary, following the Gründau floodplain to the outskirts of Breitenborn and then ascending north of the village to the forest-free Sellenstruth, then on northeast over the Hintersten Vogelkopf and Bubenrain towards Leisenwald and from there to the north.

Airways

With the growth of the Rhine-Main region and its Frankfurt am Main airport in the second half of the 20th century, the volume of air traffic rose sharply. New runways ( runway west , opening 1984) and runways ( runway northwest , opening 2011) increased the volume further. For decades there have been protests by citizens, communities and districts against the aircraft noise of low-flying commercial aircraft (e.g. city of Offenbach or communities in the Offenbach district, Main-Kinzig district). The most frequently used flight route ran in an east-west direction over the Kinzig valley from Gelnhausen via Hanau , Offenbach, Neu-Isenburg to the runways. Before the Northwest runway went into operation, Deutsche Flugsicherung GmbH “optimized” the approach routes. This led to a noise-intensive lowering of the previous flight routes over the Büdinger Forest in the north and the Spessart in the south, which then reach the previous approach routes at a low altitude between Wächtersbach and Gelnhausen via the Kinzig and Hanau. There were numerous protests by citizens and communities and a petition signed by 40,000 people to the Hessian state parliament. The Main-Kinzig-Kreis and numerous municipalities have decided to bring an administrative action.

Wind turbines

The company Renertec, Brachttal, founded in 1995, built twelve wind turbines (WKA) on the Vier Spichten in the southeast of the Büdinger Forest in 2013-14 ; the company operates around 60 wind turbines (2013), 42 of them in the Main-Kinzig district. The wind turbines have a hub height of 140 m and a rotor diameter of 110 m, for a total height of 195 m. Seven of them are in the districts of Wächtersbach, five in the Gründauer districts.

On the Hammelsberg near the Vier Fichten (the highest point in the Büdinger Forest), the operator Renertec is allowed to have five more Vestas V wind turbines (WKA) after the immission control approval issued by the Darmstadt regional council on October 30, 2019 150-5.6 MW with a total height of 241 m (hub height 166 m and rotor diameter 150 m) and a nominal output of 5.6 MW each and operate until December 31, 2049. At the same time, it ordered the immediate execution of the approval, citing Section 80a (1) No. 1 in conjunction with Section 80 (2) No. 4 of the Administrative Court Code (VwGO), so that an appeal against the approval notice has no suspensive effect .

Wild

Until the 16th century it is almost exclusively in Büdinger forest deer , barely deer and little wild boars have given. Through a connection to the Nassau Count Wilhelm, who later became Prince of Orange, some specimens are said to have come from the Breda fallow deer park to the Büdinger Forest. The fallow deer are said to have increased significantly by 1848 . Roe deer had already been nearly wiped out by lynxes and wolves . In order to curb the poaching associated with the revolution of 1848/49 , the Büdinger Forest was almost completely fenced in and controlled by foresters , hunters , forest runners and forest rangers (“Fear must guard the forest!”).

Because of the strong increase and as a result of the "peeling damage" ( game browsing on young trees), the red deer was shot down as planned from 1928, which led to an increase in the fallow deer . 1930 mouflon (the European mouflon) was introduced, which has increased good to 1945th The remains of the animals that were not killed by the US occupation troops formed a population of 100 until the mid-1980s. 1956 of the forest near the village was on the southern edge New Wirtheim (municipality Biebergemuend ) established a Saupark to the wild boar population to increase as planned. In 1964 the princely forest administration set up another game reserve in Gettenbach (district of Gründau ) to reintroduce Hungarian fallow deer and southern English red deer ("Valley of the White Deer"), so that in the second half of the 20th century red deer, fallow deer and roe deer in the Büdinger forest were native. After the transfer of ownership from the noble family zu Ysenburg and Büdingen to a forest company in 2006, mouflon is to be decimated and hunting opportunities for red deer and fallow deer are to be sold.

water

Rivers and streams

The watershed between the two main rivers, the Nidda and the Kinzig , runs relatively centrally over the Büdinger Forest , through which all the streams and rivers that cross and flow to the Main drain.

The Seemenbach , which leaves the forest area in Büdingen, flows into the Nidder , the Nidder into the Nidda, and this at Frankfurt-Höchst into the Main. The Bracht and Gründau flow into the Kinzig, which flows into the Main near Hanau-Kesselstadt . While most of the larger rivers and streams come from the Hohen Vogelsberg, the Gründau rises in the historic Büdinger Forest and in the immediate vicinity of the natural area of the same name. The latter is formed from several source streams near the Weiherhof near Wittgenborn (district of Wächtersbach ), the main artery is the Litterbach, which comes from the Weiherhof's large pond and takes in the Waschbach near Breitenborn (district of Gründau ). It flows through a meadow valley (field name: Stoppelwiese), is now called Gründau from Hain-Gründau and takes up the Gettenbach coming from the left immediately upon leaving the Büdinger Forest.

The following rivers leave the Büdinger Forest (in the following, arranged counterclockwise from the northwest):

- Laisbach (northwest border ; to the Nidda)

- Nidder (to the Nidda )

- Bleichenbach (to the Nidda)

- Wolfsbach (to the Seemenbach)

- Kälberbach (to the Seemenbach)

- Seemenbach (zur Nidder) - northern border of the historic Büdinger Forest

- Salzbach (to the Seemenbach; source in the Büdinger Forest)

- Waschbach (to Gründau; mouth already in the Büdinger Forest)

- Gründau (to the Kinzig)

- Gettenbach (to Gründau; source in the middle of the Büdinger Forest, flows into the Gründau in the area of the Gründau district of Hain-Gründau)

- Katzengraben (source in the Büdinger Forest, flows into the Gettenbach in the locality of Gettenbach)

- Hühnerflüsschen (source in the southwest of the forest area near the boundary of the Gründau district of Lieblos, but flows north and flows into the Gründau in the district of the Gründau district of Hain-Gründau)

- Bracht (directly on the southeast edge of the Büdinger Forest to the Kinzig) - Eastern border of the historic Büdinger Forest

- Salt (only on the narrow Kinzig edge in the far east in the natural area, outside the historic Büdinger Forest)

- Ulmbach (only a narrow edge)

- Kinzig (south-east and south border of the historical and natural Büdinger forest)

- Würgebach (source in the forest area of the Gelnhausen district of Haitz and there flows into the Kinzig)

Groundwater

Since 1970 the underground waters, the groundwater , have received greater public attention . The city of Frankfurt am Main has been promoting drinking water from 139 springs near Fischborn in the Vogelsberg (district of Birstein ) and 39 springs near Bieber and Kassel in the Spessart on the left of the Kinzig (districts of Biebergemünd ) since 1873 and channeling the water underground in the 70 km long Vogelsberg spring pipeline through the Kinzig valley and north of the Main into the elevated reservoir on Friedberger Landstrasse (colloquially: water park) in Frankfurt am Main, which was built in the same year . In 1902, the Frankfurt water supply company built a water tank with groundwater pumping station in the southeast of the Büdinger Forest on the Aspenhainer Kopf for the new extraction area near Wirtheim (district of Biebergemünd). By the beginning of the Second World War, 60 water extraction systems are said to have been built in the western Vogelsberg and Hessian Spessart region (roughly between Gießen and the Hessian-Bavarian border in the Main-Kinzig district).

While the city of Frankfurt am Main initially met its increasing drinking water needs from other sources after 1945, these were no longer sufficient after the population growth in the Frankfurt / Rhine-Main conurbation during the 1950s (overall, in the west of the Vogelsberg / Hessian Spessarts are in the In the 1950s and 1960s, another 175 water extraction systems were built), so that at the end of the 1960s and 1970s the upper water authority tried to designate new water extraction areas in all of southern and central Hesse (two out of five of these areas in southeast Hesse were in or on the Büdinger Forest: Breitenborn (district von Gründau) and Neuenschmidten (district of Brachttal)).

Even in the 1970s, 72 water extraction systems were built. a. Systems in the area of the Büdinger Forest in Brachttal and Kirchbracht , in Gettenbachtal (municipality of Gründau) and in Würgebachtal (city of Gelnhausen ) belonged. On the other hand, both the municipalities and environmental associations, especially over two decades, turned against two citizens' initiatives under the motto "Frankfurt drinks the Vogelsberg empty" (The output in Gettenbach in 1989 roughly corresponded to the consumption of Frankfurt Airport, the largest consumer in the field of public utilities after the US Army Frankfurt am Main ). A broad citizens' movement emerged which prompted the municipal authorities and the municipal utilities in Frankfurt am Main to save on drinking water consumption. Due to an extremely low level of new groundwater formation in the 1970s with a simultaneous steady increase in water extraction and sharply decreasing groundwater potentials, a number of problems arose in the Vogelsberg extraction areas, including the settlement of the terrain (including on houses) and the drying up of springs, wetlands and streams . In Brachttal, the 63 measuring points in the community area showed serious groundwater lowering in eight deep wells due to the funding of the Kinzig water association (the largest lowering was 34 m.) The funding intentions in Breitenborn were abandoned after test drilling and instead funded in Gettenbach. The sources of the Gettenbach dried up in 1974 and 1993 after the flow rate from the six Gettenbach deep wells was increased from 1.2 to 2.4 million cubic meters as part of an approved pumping test. The stream fell dry, so the fire brigade tried to save fish and crabs with water from the drinking water pipe. Due to this development, no groundwater was extracted in a number of other fully developed water catchment areas.In the late 80s and early 90s of the 20th century, the official water policy changed in the sense of an overall view of water extraction in South and Central Hesse (water balance) and groundwater management. That should have borne fruit, because the earlier critics are now sitting at the same table with the earlier "water robbers".

literature

- History Association Büdingen (Hrsg.): District Büdingen, essence and becoming. Büdingen 1956. ( Contributions to the monuments, communities and landscapes in today's Wetteraukreis ).

- Walter Nieß: Langenselbold - A cultural nucleus in the Kinzig valley and the Wetterau, the socio-economic development of a landscape from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period , Greiserdruck, Rastatt 2002.

- Walter Nieß: The wisdom of the Büdinger Forest - Forest legislation from 1380 . In: Bulletin of the Natural History Office of the Main-Kinzig-Kreis, (5th year, issue 3) 1993.

- Lothar Nitsche / Sieglinde Nitsche: Nature reserves in Hessen. Protect - experience - care. Volume 1 - Main-Kinzig-Kreis and City of Hanau. Published by the Naturschutzring Nordhessen e. V. and the Hessian Society for Ornithology and Nature Conservation e. V., Main-Kinzig working group. Cognitio, Niedenstein 2002, ISBN 3-932583-05-1 , p. 17f.

- Hans Philippi : Territorial history of the county of Büdingen. Writings of the Hessian Office for Historical Regional Studies 23 , Elwert, Marburg 1954, esp. Pp. 50–65.

- Alfred Pletsch: Hessen. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft (= Wissenschaftliche Länderkunden 8; Federal Republic of Germany and Berlin (West) 3 ), Darmstadt 1989, ISBN 3-534-06206-X , pp. 41–46.

- Peter Prinz-Grimm, Ingeborg Grimm: Wetterau and Mainebene. Borntraeger (= collection of geological guides 93 ), Berlin / Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-443-15076-4 , esp.p. 7.

- Martin Schäfer: Homeland book of the Gelnhausen district. District administration Gelnhausen 1950. ( Numerous individual articles for the monuments, communities and landscapes in today's Main-Kinzig district )

- Gustav Simon: A history of the royal ban forest of the Büdinger forest and the Dreieich . Sauerlander, Frankfurt 1860.

- Gustav Simon: Contributions to the history of forestry and hunting in the Middle Ages . Sauerlander, Frankfurt 1862.

- Christian Vogel: Forest rights in the Büdinger Forest from the High Middle Ages to today. In: Büdinger history sheets. 20, 2007/2008, pp. 281-350. ( Revised and expanded version as a book, Büdingen 2008 )

Web links

- Landscape profile Büdinger Forest of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation ( information )

- Search for Büdinger Forest in the German Digital Library

- Search for “Büdinger Wald” in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Information on Büdinger Forest in the HeBIS portal

- Constantia Forst GmbH

Individual evidence

- ↑ Land divorce for forest and freedom of the Büdinger forest. From March 25, 1377. In: Friedrich Battenberg: Isenburg documents, regestations on document holdings and copies of the princely archives in Birstein and Büdingen, 947-1500. Vol. 1, Darmstadt / Marburg 1976 (Repertories of the Hessian State Archives Darmstadt, 7, 1), No. 823

- ^ Heinrich Reimer: Hessisches Urkundenbuch. Volume 4, Leipzig 1897, No. 50.

- ^ Gustav Simon : The history of the imperial house of Ysenburg and Büdingen Third volume: The Ysenburg and Büdingen'sche document book , No. CXCIII., Heinr. Ludw. Brönner's Verlag, Frankfurt a. M .: p. 200, digitized

- ↑ z. B. the forest land in the forest districts near the city of Büdingen: Section 4 of the Act on the incorporation of parish-free land in the Darmstadt administrative district of July 4, 1966 , coming into force on January 1, 1967

- ^ A b Emil Meynen , Josef Schmithüsen : Handbook of the natural spatial structure of Germany . Federal Institute for Regional Studies, Remagen / Bad Godesberg 1953–1962 (9 deliveries in 8 books, updated map 1: 1,000,000 with main units 1960).

- ↑ Map and legend of the natural areas of Hesse (online copy of Die Naturraum Hessens , Otto Klausing 1988) in the Hessen Environmental Atlas of the Hessian State Office for Environment and Geology

-

↑ Various authors: Geographische Landesaufnahme: The natural spatial units in single sheets 1: 200,000 . Federal Institute for Regional Studies, Bad Godesberg 1952–1994. → Online maps

- Sheet 139: Frankfurt a. M. (Brigitte Schwenzer 1967; 35 pages)

- Sheet 140: Schweinfurt (Brigitte Schwenzer 1968; 43 pages)

- ↑ a b Numbers from Armin Gerstenhauer: 143. Büdinger Wald. In: Handbook of the natural division of Germany into major regions. P. 235f.

- ↑ a b Map services of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation ( information )

- ^ Christian Vogel: Forest rights in the Büdinger Forest from the High Middle Ages to today. In: Büdinger Geschichtsblätter 20, 2007/2008 p. 281.

- ↑ Walter Nieß: Langenselbold - A cultural nucleus in the Kinzigtal and the Wetterau, The socio-economic development of a landscape from the late Middle Ages to the early modern era , Rastatt (Greiserdruck) 2002, p. 21, with reference to Wolfgang Hartmann: Vom Main zur Burg Trifels - From Hirsau Monastery to Naumburg Cathedral, On the traces of the Franconian noble family of the Reginbodonen , series of the Geschichts- und Kunstverein Aschaffenburg e. V., Volume 52, Aschaffenburg, 2004.

- ^ Heinrich Reimer: Hessisches Urkundenbuch. Section 2, document book on the history of the Lords of Hanau and the former province of Hanau. Vol. 4 1376–1400, publications from the royal Prussian state archives (Hirzel), Leipzig 1897 no. 217.

- ^ Gerhard Köbler : Lexicon of European legal history, keyword: Reichswald. CH Beck, Munich 1997.

- ↑ Gustav Simon: The history of the imperial house of Ysenburg and Büdingen Third volume: The Ysenburg and Büdingen'sche document book , No. CXCVII. a., Heinr. Ludw. Brönner's Verlag, Frankfurt a. M .: pp. 205 ff., Digitized

- ^ A b Christian Vogel: Forest rights in the Büdinger Forest from the High Middle Ages to today. In: Büdinger history sheets. 20, 2007/2008, p. 287.

- ↑ Angela Metzner: Reichslandpolitik, aristocracy and castles - studies on the Wetterau in the Staufer time. In: Büdinger history sheets. 21, 2008/2009, pp. 113-119.

- ↑ Johann St. Reck: History of the Counts and Princely Houses of Isenburg, Runkel, Wied, connected with the history of the Rhine valley between Koblenz and Andernach, from Julius Caesar to the most recent times for friends of patriotism. Publishing house of the Grand Ducal Saxon Privil. Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, Weimar 1825, panel III; also at http://www.dilibri.de/rlb/content/zoom/557403 ;

- ^ Hermann Grote: Stammtafeln Leipzig 1877, Reprint Leipzig 1988, p. 146

- ^ Eduard Vehse : History of the German Courts since the Reformation Volume 44, Sixth Department, Part Tenth, Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1858, p. 169

- ↑ Clemens Dasler: Wildbann and forest sovereignty in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns (August 3, 2011)

- ^ Gerhard Köbler: Lexicon of European Legal History, keyword: Untereigentum , CH Beck, Munich, 1997.

- ^ Norbert Breunig: The gentlemen in Gründau - The Ysenburger as gentlemen in Gründau from 1806 to 1866 . In: Grindaha, Issue 27, publications of the Geschichtsverein Gründau e. V., Gründau 2017 p. 1 ff. ISSN 2194-8631

- ^ Text by Eduard Ellenberger: Memorandum on the replacement of authorizations in the Büdinger Walde. Büdingen 1876, p. 108. The authenticity of this document was (calculated) by the legal representative of one of the beneficiaries (the Count of Ysenburg and Büdingen in Meerholz), before the royal commission for the redemption of the rights (real loads) of the residents of in and around the communities lying in Büdinger Wald (1876) claims, s. Norbert Breunig: Allodification of the Büdinger Forest of December 31, 1812 - A forgery ?. In: Grindaha (Issue 29), Publications of the Geschichtsverein Gründau 2019, ISSN 2194-8631 , p. 10

- ↑ Norbert Breunig: 1813. A fateful year for the Gründau villages: Full of worries - Napoleon and the Grande Armée, burdens of war, robbers, epidemics, soldiers . In: Grindaha, Jahreshefte des Geschichtsverein Gründau (issue 23), Gründau 2013 p. 25 ff.

- ↑ Winfried Schenk: clearing . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria (April 12, 2012)

- ↑ Walter Nieß: Das Weistum des Büdinger Waldes - A forest legislation from the year 1380. In: Bulletin of the natural history office of the Main-Kinzig-Kreis. 5th year, (volume 3) 1993, p. 2.

- ↑ The dissertation by Walter Nieß is more comprehensive: The forest history of the Bannforst Büdinger Wald. From the origin of forestry to sustainable use. (Dissertation University of Freiburg i. Br.) 1952.

- ↑ A map of the prohibited forest area can be found in Walter Nieß: Langenselbold – Selbold - A cultural nucleus in the Kinzigtal and the Wetterau - The socio-economic development of a landscape from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period, Greiserdruck, Rastatt, 2002 p. 18

- ↑ Walter Nieß: Das Weistum des Büdinger Waldes - A forest legislation from the year 1380. In: Bulletin of the natural history office of the Main-Kinzig-Kreis. 5th volume, issue 3, 1993, p. 12.

- ↑ Walter Nieß: Das Weistum des Büdinger Waldes… In: Mitteilungsblatt der Naturkundstelle des Main-Kinzig-Kreis. 5th volume, issue 3, 1993, p. 13.

- ↑ Orthopedic University Clinic Frankfurt am Main, Friedrichsheim Foundation, http://www.orthopaedische-uniklinik.de/unsere-fachklinik/geschichte/

- ↑ Only evidence on the Internet: Archive link ( Memento from August 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Peter Hug (Ed.): Forest Law. In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon. Volume 16, p. 16.351. (online at: elexikon.ch , accessed on March 22, 2012)

- ^ Gerhard Henkel : The village - country life in Germany - yesterday and today. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2541-9 , p. 70.

- ↑ Walter Nieß: Das Weistum des Büdinger Waldes… In: Mitteilungsblatt der Naturkundstelle des Main-Kinzig-Kreis. 5th volume, issue 3, 1993 p. 9.

- ^ A b Karl Bode: Authorizations of the citizens of Breitenborn in and in the princely forests and their replacement . In: Grindaha 13, publications of the history association Gründau e. V., Gründau 2003 p. 71 f.

- ^ Christian Vogel: Forest rights in the Büdinger Forest from the High Middle Ages to today. In: Büdinger Geschichtsblätter 20, 2007/2008, Büdingen 2008 (book edition), p. 31 ff.

- ^ Eduard Eichler: The judiciary of Bosnia and Hercegovina. Vienna 1889, p. 293 ff.

- ↑ northwest of Hain-Gründau near the noise mountain (formerly: Kreischberg), which must not have existed at the end of the Middle Ages at the latest

- ↑ on the history of Hitzkirchen here ( Memento from September 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Comparison of the right of the city of Gelnhausen to claim rights with the high count houses of Ysenburg zu Büdingen, Wächtersbach and Meerholz: completed on October 3, 1755, Gelnhausen 1837, 16 pages

- ↑ Adolf Schmitt-Weigand A comparison between Gelnhausen and the Isenburg house in: Between Vogelsberg and Spessart, Heimat-Jahrbuch des Kreis Gelnhausen 1964, Der Landrat des Kreis Gelnhausen, Gelnhausen 1963, p. 136 f.

- ↑ Christian Vogel: Waldrechte im Büdinger Wald… Büdingen 2008 (book edition), p. 21 ff.

- ^ Gerhard Henkel : The village - country life in Germany - yesterday and today. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2541-9 , p. 70.

- ^ Norbert Breunig: Allodification of the Büdinger Forest of December 31, 1812 - A fake ?. In: Grindaha (Issue 29), Publications of the Geschichtsverein Gründau 2019, ISSN 2194-8631 , p. 10

- ^ Ordinance because of the common divisions for the provinces of Starkenburg and Hesse from September 7, 1814 in: Collection of the in der Großherzogl. Hessische Zeitung of 1814 published ordinances and higher orders, Darmstadt: Verlag der Großherzoglichen Invaliden-Anstalt 1815, LV, p. 43 ff .; Digitized

- ↑ Ordinance on the replacement of servitutes , the division of communities and the amalgamation of properties for the former Electorate of Hesse of May 13, 1867, Prussia GS 1867, pp. 716–726.

- ^ Eduard Ellenberger: Memorandum on the replacement of authorizations in the Büdinger Walde. Büdingen 1876, p. 162 ff.

- ↑ Eduard Ellenberger: Memorandum on the replacement of the authorizations in the Büdinger Walde. Büdingen 1876, p. 56.

- ^ Christian Vogel: Forest rights in the Büdinger Forest from the High Middle Ages to today. In: Büdinger history sheets. 20, 2007/2008, Büdingen 2008 (book edition), p. 35 f.

- ^ Eduard Ellenberger: Memorandum on the replacement of authorizations in the Büdinger Walde. Büdingen 1876, p. 117 ff.

- ^ Christian Vogel: Forest rights in the Büdinger Forest from the High Middle Ages to today. In: Büdinger history sheets. 20, 2007/2008, Büdingen 2008 (book edition), p. 73 f.

- ^ Christian Vogel: Waldrechte im Büdinger Wald… Büdingen 2008 (book edition), p. 81 f.

- ^ Insolvency reports from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) from April 19, 2005

- ↑ Commercial register at the Frankfurt am Main District Court HRB 76480; Relocation of the headquarters to Gründau by resolution of the shareholders' meeting on June 6, 2006; http://www.historische-eschborn.de/ to sell the forest

- ↑ c-forst.de

- ↑ Commercial register at the local court of Hanau HRB 91810; Christian Vogel: Forest rights in the Büdinger Forest from the High Middle Ages to today. In: Büdinger history sheets. 20, 2007/2008, Büdingen 2008 (book edition), p. 82

- ↑ For the sale of the forest s. Anita Strecker: Büdinger Wald has been sold - citizens fear for their wood rights / Viennese investors acquire the second largest property in Hesse. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. June 14, 2006, (digitized at: Historische-eschborn.de )

- ↑ On the prehistory of the intention of the recession with the "25 municipalities authorized in Büdinger Walde" of the Meerholz share in the 19th century to replace the real burden; Eduard Ellenberger: Memorandum on the replacement of the authorizations in the Büdinger Walde. Büdingen 1876

- ^ Gelnhauser Neue Zeitung. September 29, 2012 and October 5, 2012.

- ↑ K. Th. Ch. Müller (retired chamber director): Old streets and paths in Upper Hesse . In: Communications of the Upper Hessian History Association. NF Vol. 28, Giessen 1928. First part. Map supplement, map No. 3: The old roads and their relationship to settlement and territorial formation. Quoted from Walter Nieß: Langenselbold – Selbold - A cultural nucleus in the Kinzigtal and the Wetterau - The socio-economic development of a landscape from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period , Greiserdruck, Rastatt, 2002 p. 18

- ↑ Christian Vogel: Old streets in the Kinzigtal . In: Between Vogelsberg and Spessart 2016, Gelnhäuser Heimat-Jahrbuch, annual calendar for people in town and country between Vogelsberg and Spessart, published by the District Committee of the Main-Kinzig District, Gelnhausen 2015 p. 32 ff. ISBN 978-3-9808424- 7-1

- ↑ Walter Nieß: Langenselbold ... p. 19.

- ↑ REFFENSTRASSE. Hessian field names. (As of November 1, 2012). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- ↑ Karl Schmerbach: The old streets in Vogelsberg were often witnesses of great historical events . In: Between Vogelsberg and Spessart 1979, Gelnhausen Heimat-Jahrbuch, annual calendar for the people in town and country between Vogelsberg and Spessart, published by Main-Kinzig-Kreis, Gelnhausen 1978 p. 43

- ↑ RENNSTRASSE. Hessian field names. (As of November 1, 2012). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- ↑ Christian Vogel: Old streets in the Kinzigtal . In: Between Vogelsberg and Spessart 2016, Gelnhausen Heimat-Jahrbuch, annual calendar for people in town and country between Vogelsberg and Spessart, published by the district committee of the Main-Kinzig district, Gelnhausen 2015 p. 35

- ↑ ON GELNHAEUSER STRASSE. Hessian field names. (As of November 1, 2012). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- ↑ JUDENSCHNEISE. Hessian field names. (As of November 1, 2012). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- ↑ Eberhard Gömmer: VHC hike to the “Vier Fichten” wind farm . In: The Vogelsberg, magazine for home, hiking and nature of the Vogelsberger Höhen-Club e. V., 98th year, AS-Druck und Verlag Schotten (No. 3 May 2015), 2015 p. 12

- ^ Heinrich Georg Semmel: Der Judengrund and the Judenschneise in Gründau In: Grindaha, Heft 27, publications of the Geschichtsverein Gründau e. V., Gründau 2017 p. 121 ff. ISSN 2194-8631

- ↑ Eberhard Gömmer: VHC hike to the “Vier Fichten” wind farm . In: The Vogelsberg, magazine for home, hiking and nature of the Vogelsberger Höhen-Club e. V., 98th year, AS-Druck und Verlag Schotten (No. 3 May 2015), 2015 p. 12.

- ^ Wilfried Günther: Expansion of the road from Lieblos to Büdingen. In: Grindaha 22, publications of the history association Gründau e. V., Gründau 2012, ISSN 2194-8631 , pp. 121-130

- ↑ ACORN HEAD. Hessian field names. (As of November 1, 2012). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- ↑ in Sellenstruth. Hessian field names. (As of November 1, 2012). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- ↑ DFLD Radar ( Memento of the original from January 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ On the Internet: Archived copy ( Memento from December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) | In the (very) last line of this page there is a link (underlined in blue) “Current information on airport expansion” | click there!

- ↑ renertec-gmbh.com

- ↑ Millions for new mills - There are alternative plans in many municipalities. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. March 14, 2012; Twelve wind turbines planned on the four spruce trees - Renertec wants to generate renewable energy in the Büdinger Forest. ( Memento from December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: Gelnhäuser Neue Zeitung. January 18, 2012; Wind power is taking shape. ( Memento from April 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: Gelnhäuser Neue Zeitung from September 24, 2011.

- ↑ Clear the way for five new wind turbines - regional council approves project on Hammelsberg near Breitenborn In: Gelnhäuser Neue Zeitung (GNZ) of November 5, 2019

- ↑ Otto Friedrich Prince of Ysenburg and Büdingen: The game and its development in the Büdinger forest. In: Allgemeine Forst Zeitschrift. Vol. 39, 1984, p. 940.

- ^ On law and justice in the forests of Kurhessen and the criminal law and penal system in Kurhessen s. Norbert Breunig: crime scene Franzosenhau, quarreled Gettenbachers and a criminal case in the forest. In: Grindaha annual books of the Gründau e. V., issue 21, 2011, p. 80 ff.

- ↑ Constantia Forst GmbH http://www.c-forst.de/

- ↑ Water map service of the Hessian Ministry for the Environment, Climate Protection, Agriculture and Consumer Protection ( information )

- ↑ A travel guide praises the "great and highly worth seeing galleries of the Frankfurt water pipeline", which can compete with "many water pipelines of antiquity": New guide through Gelnhausen and the surrounding area. Gelnhausen 1910. (2nd edition. Home office of the Main-Kinzig district, Gelnhausen 1984, p. 34 f.)

- ↑ Herbert Glasauer, Konstanze Arndt: The development of the drinking water supply - illustrated using the example of the city of Frankfurt am Main. P. 16 and 19. (online at: uni-kassel.de )

- ^ District President in Darmstadt: Drinking water from the Vogelsberg. Darmstadt 1976, p. 13.

- ↑ Christoph Möbus: Groundwater management systems - the coupling of databases, geographic information systems (GIS) and groundwater models using the regional example of the Queckborn / Hesse extraction area. Dissertation. Univ. Giessen, 2007, p. 55.

- ↑ Stadtwerke Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurt builds up, documentation on the post-war period 1945–1965. ( Memento from December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: On the structure of the water supply in the Rhine-Main area ). (PDF; 2.5 MB), Hessenwasser (subsidiary of Mainova AG, Frankfurt, HSE AG, Darmstadt and ESWE AG, Wiesbaden)

- ^ Stadtwerke Gelnhausen GmbH

- ^ Stadtwerke Gelnhausen GmbH

- ↑ Christoph Möbus: Groundwater management systems ... p. 55 f.

- ^ Protective community Vogelsberg: Vogelsbergwasser

- ↑ naturfreunde-hessen.de ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Georg Chichorowski, Jürgen Fiedler, Bernhard Michel, Wulf Rüthrich (Cooperative, Infrastructure + Environment): Rational water use in Frankfurt am Main. Darmstadt / Frankfurt am Main, December 1991.

- ↑ Brachttal municipality (Heidrun Berressem, Marc Röder): Groundwater in Brachttal, a documentation of 15 years of water abstraction, data and diagrams of wells, sources and measuring levels. Brachttal, October 1992.

- ↑ Darmstadt Regional Council: Groundwater extraction for public water supply. (Status 2008), updated in the environmental report of the Main-Kinzig district, online here: [1]

- ↑ Is the Gettenbach drying up? In: Gelnhauser Tageblatt. February 21, 1974.

- ↑ Doing business with water at the expense of fish and crabs in the Gettenbach, increased funding from the Gelnhausen municipal utilities destroys a previously intact biotope. In: Gelnhäuser Neue Zeitung. 5th July 1993.

- ↑ Christoph Möbus: Groundwater management systems ... p. 56.

- ^ Hessian Ministry for the Environment, Energy, Youth, Family and Health: Environmentally friendly water production in the Vogelsberg. 1st edition. Wiesbaden June 1997.

- ↑ Stephan Kümmel: First Molotow, then with each other - the Kinzig water association and the Vogelsberg protection association cooperate in water extraction in the northern district. In: Gelnhäuser Neue Zeitung. 4th May 2013.