Brazilian literature

Brazilian literature is the literature from Brazil written in the Portuguese language . A distinction must be made between the literature before and after independence in 1822. Pre-independence literature was mostly shaped by Portuguese, many of whom were born in Brazil but considered themselves Portuguese. The most famous representative was the "Apostle of Brazil" António Vieira . After the country gained independence in 1822, Brazilian literature, which has been perceived as independent since the middle of the 19th century, also made reference to the African and indigenous minorities and has expanded strongly to this day, but is less noticed in Europe than the literature of the Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America. This is largely due to the fact that the Portuguese language is limited to four countries (besides Brazil), three of which are in Africa.

Beginnings: Colonial times from 1500

General see also:

First travel reports

For the period from 1500 to 1700 mainly travel reports and especially mission reports from Portuguese sources have come down to us. Pero Vaz de Caminha , the helmsman of the Portuguese navigator and Brazilian explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral , was the first European to describe Brazil and the landing of the fleet on the coast of Salvador da Bahia in a 27-page letter, the Carta a el-rei D. Manuel sobre o achamento do Brasil , known for short as the "Letter of Pero Vaz de Caminha", in 1500 to the Portuguese King Manuel I.

Many Portuguese travelers such as Manuel da Nóbrega (1517–1570) or Gabriel Soares de Sousa (1540–1591) in his Notícia do Brasil , which only appeared in full as Tratado Descriptivo do Brasil in 1587 in 1851 , described Brazil from an ethnological , anthropological and biological point of view. Her works give insights into the flora , fauna and the first contact with the native Indians in Brazil in the 16th century.

The descriptions of the German military and mercenary commander Hans Staden are the first of a non-Portuguese on the subject. In it he described his experiences in the service of the Portuguese governors in Brazil, mixed with stories about the indigenous people of the country. Fernandes Brandâo, on the other hand, described Brazil's agricultural potentials from the perspective of the slave-holding colonists in 1618.

The baroque period

The Jesuit José de Anchieta (1537–1597) wrote popular mystery plays for the Indians, in which they themselves participated. Several works are ascribed to the Portuguese Bento Teixeira (1561? - July 1600) who emigrated to Brazil . His authorship is only proven for the first Baroque epic in Brazil, Prosopopeia (1601), in which he described the deeds of the then governor of Pernambuco , Jorge de Albuquerque Coelho, and his brother Duarte in Africa and Brazil, possibly in anticipation of financial donations. He wrote the work in a Portuguese monastery where he had fled because of the murder of his wife. This had accused him of blasphemy and the practice of Jewish rituals. At this time the Cristãos-novos , the converted Jews, were persecuted. He eventually confessed to being a Jewish believer, but the death penalty was averted and he died in prison. The five-part form of the work corresponds to the Portuguese national epic Os Lusíadas (1572) by Luís de Camões ; it is written as a ten-syllable and is complicated by a Latinized syntax . The work first shows (in the description of Pernambuco) the Brazilian nativismo , which is later found mainly in the Arcadian and Romantic description of the landscape.

In the struggles against the English and Dutch (the latter had established themselves in Pernambuco from 1630 to 1654 and also granted freedom of religion to the Jews), an early feeling of nationality among the Brazilians awoke that suppressed the feeling of complete cultural dependence on the motherland. It was reflected in the História da custódia do Brasil (1627) of the Franciscan Vicente do Salvador (1564-1636). At that time, the capital, São Salvador de Bahia, was the country's cultural center. Bahians were also the poet Manuel Botelho de Oliveira (1636–1711), who wrote the main lyrical work of the Baroque with Música do Parnaso (1705), the prose poet Nuno Marques Pereira (1652–1728) and Gregório de Matos (1636–1696). This applies with his sonnets , where he worshiped black women and mulattos and nobility and clergy criticized the first of the major poets of Brazil and representatives of Gongorism , an extremely verschraubt- mannered style. He was nicknamed Hell's Mouth because of his sharp satires and had to go into exile to Angola for a time because of his critical attitude .

Padre Antônio Vieira , who immigrated from Portugal and was accused of heresy but rehabilitated, emerged as a preacher, opponent of the Inquisition and critic of colonial ills . The forerunner of liberation theology was apparently also influenced by Jewish messianism . In his only seemingly paradoxically titled “History of the Future” (because this was fixed from the beginning of time) he called for freedom of settlement for Jews, since their conversion to Christianity would take place anyway in the face of the impending apocalypse .

The late 18th century: arcadismo

In the 18th century, the differences between Brazil and the motherland intensified. In Brazil there was a printing ban from the middle of the 18th century until 1808, as writings by authors persecuted by the Inquisition had been printed here. For decades there was neither a printed press nor book publishers. The ban wasn't lifted until the royal Portuguese family fled Napoleonic troops to Brazil. Therefore, no independent colonial literature emerged in the second half of the 18th century; rather, the focus was on Europe again.

In the late 18th century, the cultural focus shifted to the gold mining area of Minas Gerais . A separatist-republican movement had formed there in Ouro Preto . The poets who belonged to it acted more politically. The beginning of this movement is set on the publication date 1768 of the anacreontic poetry Obras poéticas by Cláudio Manuel da Costa (1729–1789), who founded an academy in Ouro Preto. The cultural influence of Portugal declined as a result, the influence of France - especially of neoclassicism and the bucolic of French rococo , here called Arcadismo - increased. One of the authors of the Escola Mineira , Tomás Antônio Gonzaga (1744-1810), was at the head of the Inconfidencia Mineira freedom movement, which was suppressed by the government . He became known as the most important lyric poet of the time through his work Marília de Dirceu and is considered the author of the anonymously published satirical work Cartas Chilenas (Chilean Letters), which paints a portrait of colonial society. He died in his exile in Mozambique . The monk José de Santa Rita Durâo (approx. 1722–1784) describes in his heroic epic Caramurú (1781) the discovery of Bahia around 1510, the life of a shipwrecked Portuguese among the Indians and the founding of Rio de Janeiro in the meter of the Luisaden . In his blank verse epic O Uraguay (1769), José Basílio da Gama depicts the struggle of the Portuguese against an Indian rebellion in Uruguay , fueled by the Jesuits , the story being embedded in lyrical descriptions of nature.

From the 1770s onwards, other academies, seminars and, in some cases, short-lived literary societies such as the Sociedade Literária do Rio de Janeiro were created , which were initially images of the corresponding institutions in the motherland - albeit with a certain lack of modernity - but which became collecting tanks for the critical and Masonic Creole intellectuals . The thoughts of the Enlightenment cherished there influenced the slave revolt of Bahia in 1798. Above all, however, they prepared the revolt of Pernambuco in 1817, which was directed against the presence of King João VI . He ruled the United Kingdom of Portugal and Brazil from Rio der Janeiro , but neglected the northeast of the country, which was suffering from hunger after crop failures, and disappointed the hopes of São Salvador da Bahia to become the capital again.

From independence to 1900

Brazil gained independence from Portugal in 1822 and has since flourished as an independent nation. The 19th century in particular brought very famous Brazilian authors such as José de Alencar (1829–1877), Casimiro de Abreu (1839–1860) or Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1839–1908), probably the most important Brazilian writer in the 19th century, emerged.

The 19th century was shaped by several sub-periods of Romanticism (Romantismo), from the second half of the century by Naturalism (represented by Aluísio Azevedo , for example) , Realism (Realismo) - founded by Machado de Assis - and Symbolism (Simbolismo). Brazil is going through these eras, so to speak, in fast motion by adopting European models, but adapting them to its own requirements.

Literature during the Empire: Romanticism and Indianismo

While the European romantics often turned thematically to the Middle Ages, Brazilian writers thematized their own history, whereby the situation of the native "noble savages" was strongly idealized ( Indianismo ). The internal contradictions of society were expressed in a broad spectrum of political statements, ranging from the defense of the feudal order to the proclamation of revolutionary ideals. Romanticism began in Brazil at the time of the Empire around 1830; its founder is considered to be the doctor, politician, psychologist and poet Domingos José Gonçalves de Magalhães , Count of Araguaia (1811-1882), who wrote the first literary history of Brazil and - following the example of the Schlegel brothers - started various magazines. With Antônio Gonçalves Dias (1823–1864) romantic poetry reached its first climax. The historical-patriotic poetry collection Primeiros cantos (1846) was followed by two more volumes. Dias was the son of a Portuguese father and mother who had Indian and black ancestors. He suffered from his experience of exclusion and is considered an early representative of Indianismo , who also researched the indigenous population, their languages and myths of origin and thus contributed to the mythologization of the arid wasteland of the Brazilian northeast, the Sertão .

“ The first mass in Brazil ”, historicizing painting by Victor Meirelles , 1860

The late Romanticism, influenced by Byron's work , was concentrated in São Paulo and its Weltschmerz was cultivated primarily at the law school. The main work of Casimiro de Abreu (1839-1860), who died early, is the collection of poetry As primaveras (Spring) , published in 1859 . The socially committed Escola Condoreira ( Condoreirismo ) was created in response to romantic subjectivism . These included the poet Antônio de Castro Alves (1847–1871), who worked in Os escravos (posthumously) as well as the philosopher and publicist Tobias Barreto (1839–1889) from Recife, who was committed to rationalism and positivism .

By José de Alencar , a representative of the influenced of France romantic but not idealistic novel, was published in 1857 one of his most important works, O Guarani , the first in a novel trilogy about the indigenous people of Brazil, the 1865 Iracema (an anagram of " America ”), a book that creates identity for the Brazilian people, and in 1874 Ubirajara followed. These works are less impressive because of the fate of their indigenous, highly idealized heroes and heroines, but rather because of their choice of words, their richness of images and, above all, the musical rhythm of their language. The Indianismo remained artistic expression of a feudal upper class; he ignored the problem of slavery as well as urban life. Antônio de Almeida (1830–1861) described in his novel Memórias de um sargento de milícia (1854/55), first published anonymously as a sequel, the life of the common people in Rio de Janeiro from the point of view of a police officer and thus approached realism and naturalism .

The Viennese Romanist and librarian Ferdinand Wolf (1796–1866) was the first representative of his subject to recognize that an independent literary development was emerging in Brazil. He presented this view in a work written in French, which he dedicated to the Emperor of Braislien ( Le Brésil littéraire , 1863).

Antônio Gonçalves Dias , around 1860

Machado de Assis , 1890

Olavo Bilac (date unknown)

Realism and naturalism

With the growing independence of Brazilian literature, poets and writers turned more and more away from the feudal Portuguese past and towards Brazilian society, with European models such as Emile Zola and Eça de Queiroz playing an important role. This is especially true of Artur Azevedo , who wrote more than a dozen plays, and Júlio Ribeiro , author of the anti-clerical novel A carne (1888), in which he refers to Darwinism . After the end of the Empire in 1889, European influence increased even further. Interest in the situation of black slaves on the plantations also grew during this time; Brazil was the last country in the western world to finally abolish slavery only in 1888. Perhaps precisely because of this, the influence of African culture, especially in the northeast of the country, proved to be permanent.

The lawyer Herculano Marcos Inglês de Sousa (1853-1918) published the first naturalistic novel in Brazil in 1877 ( O Coronel Sangrado ). In O Missionário (1891), a work influenced by Emile Zola, he meticulously describes life in a small Amazonian town. Raul Pompeia , who first dealt with the problems of adolescents in his novel O Ateneu (posthumously 1888), shows himself to be influenced by Gustave Flaubert . Also Aluísio Azevedo was for romantic beginnings with the novel O mulato a representative (1881) of naturalism.

Standing: Rodolfo Amoedo , Artur Azevedo , Inglês de Sousa , Olavo Bilac , José Veríssimo , Sousa Bandeira , Filinto de Almeida , Guimaraes Passos , Valentim Magalhães , Rodolfo Bernadelli , Rodrigo Octavio , Heitor Peixoto .

Sitting: João Ribeiro , Machado de Assis , Lúcio de Mendonça , José Júlio da Silva Ramos .

Joaquím Machado de Assis broke the dogmatic corset of naturalism. His tone of giocoserio is somewhere between funny and cocky and melancholy. His late works cannot be clearly assigned to any genre. above all his metafictional funny-tragic life review from the afterlife Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas (1880; Ger. The subsequent memoirs of Bras Cubas only 2004), which is reminiscent of the memoirs of Tristram Shandy . In it, Machado des Assis reflects on his own means and methods in a highly ironic way while writing. He not only became the initiator and most important narrator and novelist of Brazilian realism, but also a harbinger of magical realism. Carlos Fuentes called him the "Brazilian Cervantes ". Machado de Assis was co-founder and first president of the Academia Brasileira de Letras in 1896 .

Parnassianismo brasileiro

In poetry, a short epoch of European-influenced simbolismo (representatives , inter alia, João da Cruz e Sousa ) in the late 19th century was followed by its special Brazilian form of Parnasianismo brasileiro ( Parnassianism ). Teófilo Dias , Alberto de Oliveira , Raimundo Correia and Olavo Bilac , a forerunner of modernism who, through his sonnets , belonged to this movement, which in 1878 declared war on Romanticism in the pursuit of formal perfection and called for the "Battle of Parnassus" e.g. Vanitas ) became known. The work of the representatives of Parnassianismo was characterized by aesthetic perfection, impersonality and orientation towards ancient models (preference for the sonnet , rigorous metrics ), but also by pessimism and disillusionment.

The 20th century

In general, 20th century Brazilian authors followed the tendencies of Latin American literature . Right at the beginning of the century, this included the socially critical reappraisal of one's own history and becoming a state and the discovery of the impoverished northeast of the country for literature. This period until 1922 is known in Brazil as the time of pré-modernismo . Euclides da Cunha became known for his book Os Sertões , published in 1902 , which dealt on a documentary basis with the destruction of the Canudos settlement in Sertão by the Brazilian military.

Euclides da Cunha , around 1900

João do Rio , 1909

Lima Barreto , 1917

The cronistas brasileiros

As in other Latin American countries, the variety of forms used by Brazilian authors who had to work as journalists because they could not make a living from writing was characteristic. This is how a special genre of narrative journalism emerged from the end of the 19th century that has been cultivated up to the most recent times: the crônica , which can be classified between the features section and the short story. The narrative style is journalistic, sometimes humorous or sentimental; the language is simple; often the texts are illustrated. The work by Afonso Henriques de Lima Barreto , which includes essays, columnist articles, short novels and sometimes bitter satires ( Triste Fim de Policarpo Quaresma 1911), is an example of this genre . João do Rio is a typical chronicler of the Belle époque . The explosive growth of Brazilian cities at the beginning of the 20th century is expressed in the work of Benjamim Costallat (1897–1961). He picked up sensational topics such as sex and crime ( Mistérios do Rio , 1920) and also published works by other cronistas . The genre of Crônica has continued until the 1980s, such as in the works of Millor Fernandes (1923-2012), Lêdo Ivo , a critic of the military regime, and Rubem Braga .

Modernismo

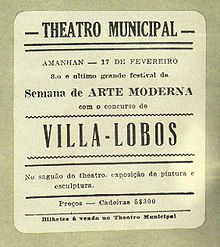

The first avant-garde generation of Modernismo brasileiro , the "Generation 22", named after the strong impression made by the art, literature and music festival Semana de Arte Moderna in São Paulo (February 1922), was mainly represented by Oswald de Andrade , who developed counter-actions against the supposedly destructive European culture that were close to futurism and sought to free language from the fetters of syntax. His narrative style, which is experimental in structure and often realistic in detail (especially in Miramar , 1924) borrows from the satires Machados and da Cunhas as well as Marinetti . Instead of importing culture from Europe, Oswald demanded an export of the “primitive” Brazilian everyday culture: “What is Wagner against the Carnival in Rio?” Oswald de Andrade published the Manifesto da Poesia Pau-Brasil in 1924 and the surrealist Manifesto antropófago of the so-called man- eater movement in 1924 , which paid homage to a rather artificial primitivism and also had an impact on the visual arts. Critics tried to convict him of imitating Dada and German Expressionism .

The rejection of the European models was also fueled by the enthusiasm for the Indians. The right-wing intellectual Plínio Salgado learned Tupi in the 1920s and tried to “Indianize” Brazilian literature from a political and civilizational perspective. H. to give it a new identity based on the Tupi mythology. In the 1930s he rallied the Brazilian supporters of fascism.

The formally modernist main work by Mário de Andrade , his important novel Macunaíma - The Hero Without Any Character from 1928, is shaped by the living environment and mythology of the indigenous people of northeastern Brazil. In addition to the peculiarities of the local language, Andrade takes on numerous customs and elements of the popular belief of the indigenous people, which already refers to the magical realism. His goal is to paint a picture of the unsettled, always youthful and flexible Brazilian character, which of course shows ethical deficits.

Manuel Bandeira was also part of the avant-garde . This - albeit a subtle poet and prose writer - gave modernismo socially critical and dramatic accents and was productive until the 1950s. However, the modernist movement soon split up into small groups.

Regionalismo and Neorealismo: The Generation of the 1930s

Henrique Maximiano Coelho Neto persisted with his traditional narrative style and his choice of “folkloric” themes from the Amazon region in opposition to modernism. This was replaced after the revolution of 1930 by the Regionalismo brasileiro . The novel A Bagaceira by José Américo de Almeida is considered to be the initial work of this movement, which can be viewed as a Brazilian variant of neorealism . The representatives of this movement such as José Lins do Rego , Graciliano Ramos ( Vidas Secas 1938, filmed in 1963, German edition “Karges Leben” 2013) and the early Jorge Amado , who published his first book at the age of 19, addressed them - inspired by the work of Sociologist and anthropologist Gilberto Freyre - the persistent misery of the workers and landless in Sertão, the north-east of Brazil, which has been further impoverished by the global economic crisis . In the 1930s, many authors joined the Communist Party, including Ramos, Jorge Amado, and Rachel de Queiroz . From a psychological point of view, the actors in her work are drawn much more simply than the complex subjects of Modernismo.

Under the dictatorship of the anti-communist and anti-Semitic populist Getúlio Dornelles Vargas , the so-called Estado Novo , many authors like Freyre left the country in the 1930s, while Brazil at the same time proved to be a relatively generous country of exile for German and Austrian emigrants (e.g. for Stefan Zweig and Willy Keller , who later translated many books from Brazilian Portuguese into German). Patrícia Rehder Galvão (pseudonym: Pagu or Pagú ) (1910–1962), who temporarily lived with Oswald de Andrade and went into exile in Paris in 1935, also continued to represent the position of an aesthetic avant-garde as a militant communist.

Graciliano Ramos, who is regarded as a representative of the psychological novel in the successor of Dostoyevsky and as a forerunner of existentialism , penetrates psychologically much deeper than the other representatives of the generation of 1930 . In his novel Angústia (1936, Eng . "Angst", 1978), published during his stay in prison (he was imprisoned as an opponent of Vargas ), he addresses existential fear, the suffering from the inescapable mediocrity that the first-person narrator down to Loss of reality leads. Many of his works are shaped by autobiographical experiences. In 1953 his prison memories appeared posthumously in four volumes. Here the compulsion to write appears as a means of self-preservation in the face of borderline experiences such as treason, torture, murder and rape, whereby Ramos makes the behavior of the guards and fellow prisoners understandable from the circumstances and their social role.

Érico Veríssimo continued working on social issues in the 1940s. He was one of the important representatives of a second phase of Modernismo ( Neomodernismo ). The Crônica also continued to develop in the 1940s and 1950s, particularly through Rubem Braga, who was arrested several times for his controversial articles. The polyglot novelist João Guimarães Rosa can be regarded as a representative of magical realism or better (because of his recourse to European, non-indigenous myths): a literatura fantástica ( Grande Sertão , 1956). The head of cabinet Kubitschek and later diplomat Murilo Rubião , a main exponent of magical realism, wrote Kafkaesk fantastic short stories .

After the Second World War

The post-war generation ("Generation 45") completely turned away from romanticism and sentimentalism and looked for new forms of expression. These include above all the representative of Neomodernismo João Cabral de Melo Neto (1920–1999), who, alongside Carlos Drummond de Andrade as the greatest modern poet in Brazil, deals with the social problems of his homeland Pernambuco in his metaphoreless, sober poems , as well as the poet Ferreira Gullar and the author of avant-garde novels influenced by the Nouveau Roman Osman Lin , who can be considered a representative of magical realism. Also Clarice Lispector overcame already with her first novel Perto do coração selvagem (1943, dt. "Near the Wild Heart") the regionalismo by analyzing the confusing inner life of its heroine. In the narrative prose of these authors, realistic, fantastic and absurd elements merge. As with Lispector, the worldview of many other writers is characterized by chaos, pessimism and rebellion against social conventions.

In the 1950s, under President Juscelino Kubitschek, a new Brazilian national consciousness ( Brasilidade ) awoke ; In turning away from foreign models, new aesthetic standards were sought. In São Paolo, under the influence of structuralist linguistics, Concretismo , the Brazilian Concrete Poetry, developed . It was created largely independently of European developments (e.g. Gerhard Rühm ) as part of the Noigandres artist group founded in 1952 with Augusto de Campos , Décio Pignatari , José Lino Grünewald and Haroldo de Campos , an outstanding Dante translator. Its members, who also published magazines, were among the most emphatic advocates of the principle of concrete poetry, in that they put the sound and word material of language in direct aesthetic relation to the printing surface.

One of the outstanding poets is the 2010 Prémio Camões laureate Ferreira Gullar , who in 1959 with the painter Lygia Clark , the sculptor and filmmaker Lygia Pape , the sculptor Amilcar des Castro and other artists oriented the group towards geometric rigor and expressiveness at the same time Neo-Concrete ( Neoconcretismo ) founded. The social historian and essayist Sérgio Buarque de Holanda wrote important essays on the development of the Brazilian national identity.

The time of dictatorship

In the early 1960s, the modernization euphoria in Brazil had reached a second peak after the Vargas era. But in 1964 the military dictatorship led to severe restrictions. Ferreiro Gullar, who headed the cultural foundation in the new capital Brasília , had to go into exile. He shared this fate with the anthropologist and writer Darcy Ribeiro , who had developed a theory of civilization using the example of the largest “neo-Latin” country, Brazil. The magical realist and connoisseur of the culture of the northeast João Ubaldo Ribeiro also went into exile for a short time. With his novel Sargento Getúlio (1971; German 1984, film adaptation 1983), a manic inner monologue of someone overwhelmed by illegal orders, he persecuted someone for an act of truth Policemen who continued the story of the archaic sertão begun by Ramos and thus continued the regionalist tradition. In 1985 his novel Viva o povo brasileiro followed , a story of the rebellion of the predominantly black Bahian people, deeply rooted in African traditions, against large landowners, government soldiers and the money aristocracy from the 17th to the 20th century.

The poet and prose writer Thiago de Melo and the musician, pop star (known worldwide through A banda 1966), novelist and well-read theater poet Chico Buarque (a son of Sérgio Buarque), whose protest song Apesar de Você only went into exile, went into exile was discovered by the censors. Ignácio de Loyola Brandão had to publish some of his books, which dealt critically with the military regime, abroad.

In the early days of the dictatorship, the movement of tropicalism ( tropicália , named after a work by the sculptor and environmental artist Hélio Oiticica ), based on anarchist ideas by Oswald de Andrade, emerged. The movement found expression above all in music (mainly through Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso ), but also in film ( Glauber Rocha ) and in literature ( Torquato Neto , 1948–1972) and was initially directed against the old anti-imperialist left . When it increasingly challenged the military government, it was smashed in 1968.

In the “post-tropicalist” 1970s, shorter texts were often distributed using mimeographic processes or as a transfer , and later as photocopies in order to circumvent censorship. The poet Ana Cristina Cesar (1952–1983) and Waly Salomão were among the young representatives of this geração mimeógrafo ("Generation of Multipliers ") . The works of these resilient authors, mostly from Rio de Janeiro, outside the mainstream are known as poesia marginal because they have been ignored by the publishers.

Moacyr Scliar (“The Centaur in the Garden”, German edition 2013), whose works have been translated into numerous languages, dealt with the issues of exile, the diaspora and the identity of Jewish migrants in Brazil . The socially committed Lygia Fagundes Telles became known through her stories. Her book As meninas (1970; Eng . "Mädchen am Blaue Fenster", 1984) describes the life of young girls under the military dictatorship. Raduan Nassar ( The Patriarch's Bread , 1975, German 2004), son of Lebanese immigrants, retired to the countryside in the early 1980s. This was also done by Hilda Hilst , author of plays, novels and short stories, who can be counted among the representatives of magical realism with her penchant for the supernatural, the peculiar and the obscene. Gilberto Freyre, however, supported the military dictatorship.

Augusto Boal (2008)

João Ubaldo Ribeiro (2009)

The Brazilian theater in the 20th century

There have also been some outstanding authors in drama since the end of the 19th century, such as Artur Azevedo with his comedies , Nelson Rodrigues with a total of 19 plays and Jorge de Andrade , who had firsthand experience of the breakup of the big landowning families in the southeast. He was the first really successful modern playwright in Brazil.

The Vargas dictatorship favored the emergence of amateur theater as the major commercial theaters were censored. In 1938 the Teatro do Estudante do Brasil in Rio de Janeiro was founded by Carlos Magno . Nelson Rodrigues (1912–1980), with Vestido da Noiva (“The Wedding Dress”, 1943), is considered the most important innovator of Brazilian theater. After the Second World War, the trend was reversed: the Teatro Brasileiro de Comédia (TBC) in São Paulo was created to meet the needs of wealthy citizens.

A counter-movement quickly set in: The play Eles nicht usam black-tie (“They don't wear black ties”, 1958) by Gianfrancesco Guarnieri was the first to deal with the life of industrial workers and in the favelas .

Influenced by Jesuit theater was Ariano Suassuna , who founded the Teatro Popular do Nordeste in Recife together with Hermilo Borba Filho in 1959 and whose popular pieces aimed at arousing strong emotions can be attributed to the literary neo-baroque .

The popular culture movement of the early 1960s under President João Goulart led to the establishment of the Centros Populares de Cultura (CPC) . There and in universities, at union evenings and on the streets, political agitation pieces were performed: "Arte para o povo e com o povo." In 1964 the CPC was banned. With the passing of the Institutional Act AI-5 in 1968, the legal basis for repression of any kind and the mass persecution of alleged opponents was created. From then on, the avant-garde theater in particular was considered an enemy of the state in Brazil. The most important theaters closed during the military dictatorship: in 1974 the Teatro de Arena under José Celso , who went into exile in Portugal, and in 1971 the Teatro Oficina under Augusto Boal , who achieved worldwide effects with his theater-pedagogical concepts such as the Theater of the Oppressed suffered from numerous censorship orders.

Popular music remained a means of expression for the opposition. Chico Buarque became known as the poet of bossa nova at the time of the military dictatorship with ambiguous and allusive texts. Tropicalismo in the theater (represented by O Rei da Vela by Oswald de Andrade and Roda Viva by Chico Buarque), a consumer-critical movement of the 1960s and 70s that originally emerged in popular music, later left its mark on the theater and took away the saturation of the Bourgeoisie on the grain.

After the military dictatorship

The world's best-known writer in Brazil has remained for many years until today the novelist Paulo Coelho , who was also occasionally persecuted by the military regime in the 1970s , whose magical realism-influenced books often deal with the search for spiritual meaning and became bestsellers in many countries (first O Alquimista 1988, German The Alchemist 1996).

The spread of television in the 1980s and 1990s meant that the previously popular chronicles lost their importance. With increasing urbanization and the development of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro into megacities , magic realism based on regional coloring and rural myths lost its importance towards the end of the 20th century. Everyday urban issues have dominated ever since. Caio Fernando Abreu (1948–1996), novelist, storyteller, playwright and screenwriter, described the countless contradictions of urban Brazil and combines these with personal confessions. He was the first Brazilian author to address AIDS . He received the Prêmio Jabuti twice. The former patrol officer and lawyer Rubem Fonseca , who was productive well beyond the age of 80, addressed the social pathologies, hatred and violence of rapidly growing cities ( Os prisioneiros , 1963; O cobrador , 1979; Carne crua , 2018). He also took up topics from the national past such as the suicide of Getúlio Vargas and the subsequent state crisis ( Agosto , Eng. "Murder in August", 1990). Milton Hatoum , son of Lebanese immigrants, links autobiographical family conflicts in his novels, the failure of migrants in the periphery of the Amazon and the resistance of students against the military dictatorship ("Emilie or the death in Manaus", 1992; "Zwei Brüder", 2002; "Ash from the Amazon", German 2008).

Silviano Santiago , who had already dealt with the Vargas dictatorship in 1981 with his formally outstanding novel Em Liberdade , published Heranças (“Inheritance”) in 2008, a melacholic-cynical story of the 20th century. The political scientist and journalist Bernardo Kucinski , who comes from a Polish-Jewish immigrant family and had to go into exile in London for two years, worked on the legacy of the dictatorship in several publications a. a. over the death squads . In “K. or The Disappeared Daughter ”(2013) he draws parallels between the resistance against the German persecutors and that against the Brazilian dictatorship. In the wide- ranging oeuvre of the narrator, essayist and literary scholar Luiza Lobo (* 1948), feminist topics play a major role. Also Cíntia Moscovich (* 1958) explores with their stories, the rooms where today women in various social contexts of Brazil act.

21st Century: Diversity, Migration and Urban Violence

The authors of the generation that began to write around 2000 used the computer as a writing tool and to create cross-media relationships, for hard cuts and text montages. This includes Joca Reiners Terron (* 1968), who presented the work of this generation in several anthologies.

The more recent Brazilian literature is consistently fascinated by the big city, which has a tendency to expand infinitely and at the same time to fragment. The often hopeless struggle for individual success in a competitive society, for the search for identity and advancement in urban chaos becomes a constant topic, at the same time the plurality of voices and literary forms increases. The metafictional texts by Sérgio Sant'Anna with their mix of styles (* 1941) embody this type of urban literature particularly succinctly.

In Chico Buarque's parable-like novel Estorvo ("The Hunted", German 1997), which is set in an anonymous location, someone flees from stalking, the reasons for which he does not know. Is it political opponents, is it the drug cartel or an intrigue of spurned love? In Leite Derramado (2009; Eng . Vergossene Milch 2013) he addresses the extremely conflict-laden multiculturalism of Brazil, which is reflected in the contradicting memories of the centenary main character in the novel Eulálio. In 2019 Buarque received the Prémio Camões .

Rural Brazil is being marginalized and mostly only exists as a scenario of the past; but many authors think back to what has disappeared and try to reconstruct it. Luiz Ruffato (* 1961), grandson of illiterate Italian immigrants, formerly a locksmith, textile worker and journalist, attempts to work on the history of the Brazilian proletariat in literature. He tells the life of immigrants from the country who end up in the slums of São Paulo and all of them fail. His five-volume cycle Inferno próvisorio (German: Provisional Hell ) is also published in German. Ruffato tries to recreate the vernacular in literary terms. In 2013 he was the literary opening speaker at the Frankfurt Book Fair. In view of the Brazilian economic crisis since 2014, his novel I was in Lisbon and thought of you (German 2015), translated into German, is very topical. It deals with the disappointments of migrants from rural Brazil, who are now increasingly looking for their fortune in the repellent Portugal. Paulo Scott describes fates "on the fringes of racial and class society".

João Paulo Cuenca at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2013

A well-known representative of the literatura marginal , which gives authentic speakers from the periféria a voice , is the author, rapper and activist Ferréz (Reginaldo Ferreira da Silva, * 1975) who lives in the gang-dominated favela Capão Redondo in São Paulo. In this subculture, the search for identity develops aggressive forms. The autobiographical novel Reservado (2019) by Alexandre Ribeiro , set in the rapper and hip-hop scene, refers to the young victims of violence and racism. Daniel Galera , also known as a translator, is considered one of the best young authors; It deals with topics such as machismo, the inability of men to communicate ( Flut , Ger. 2013) and the identification and lack of prospects of younger people. T. in a village past. Even Fred Di Giacomo Roman Desamparo (2019) deals with the historical victims of the Portuguese colonization of the region around São Paulo.

Bernardo Carvalho (* 1960) walks the fine line between fiction and reality in Amazonia with his detective novel Nine Nights (2006), which has been awarded the Prêmio Machado de Assis and the Prêmio Jabuti . At times he was visiting professor in Berlin (“Berliner Tagebuch”, 2020). The multiple award-winning Michel Laub (* 1973) wrote in his novel Diary of a Fall (German 2013) about remembering and forgetting after Auschwitz . Two novels by João Paulo Cuenca (* 1978) have so far been translated into German. Cuenca has been on reading tours in Germany several times and has also stayed as a guest author in other European countries, Japan and the USA. He has edited numerous anthologies and written plays and scripts. Under many pseudonyms, Julio Emilio Braz writes crime novels, comics and western stories as well as screenplays and youth books such as the children's book “Kinder im Dunkeln”, which was translated into German in 2007, about Brazilian street children .

Carola Saavedra , born in Chile in 1973, writes novels and short stories about the search for meaning in everyday life, which have found readers beyond Brazil. Biographically based transcultural influences such as Carola Saavedra can also be found in Paloma Vidal (* 1975 in Argentina) and Rafael Cardoso (* 1964), a great-grandson of the banker and art patron Hugo Simon , who went into exile after 1933. Cardoso lives in Berlin today. Adriana Lisboa (* 1970), who lives temporarily in the USA, is fascinated by the diversity that Brazilians encounter outside of their familiar culture. Valéria Piassa Polizzi (* 1971) writes in her autobiography Depois daquela viagem (1997) about her experiences as an HIV-infected person. This book has been translated into several languages and sold 300,000 times in Brazil and 100,000 times in Mexico.

The literatura gay is getting more and more resonance. Santiago Nazarian's novel Feriado de mim mesmo (Vacation from Myself, 2005) is a novel about the failing life plan of a young man who goes mad because he seems to suppress his homosexuality (which was not addressed at the beginning of the book). Natalia Borges Polesso (* 1981) deals with love and friendship between women in her novels ( Amora , 2015).

Other genres and sub-genres such as the adventure novel, the women's crime fiction and a special “football literature” have also found widespread use in prose. Luís Fernando Veríssimo , a popular master of the Crônica (short, often satirical everyday texts), newspaper and crime author, had sold five million books by 2006. In view of the variety of literary forms, the novel as the flagship of middle-class literature has not yet completely served its purpose, but it is subject to tendencies towards hybridization. In the interior of the novel, there are often forms that point beyond the genre, e.g. B. in Luiz Ruffato's city prose. Typical of the current Brazilian literature, however, is the mostly actively involved, auto- or intra- diegetic , constantly present or fictitious editor acting first-person narrator, often accompanied by intertextual experiments.

- Poetry

After the neo-avant-garde movement of concrete poetry had subsided, lyric poetry as an actually "quiet", reflective medium has largely withdrawn to niche areas today - or it moves across borders in the rap or hip-hop scene, where it uses favela topoi and puts the bandido in the place of the bourgeois. Interactive cyber poetry has shifted Eduardo Kac . However, texts that are not too complicated and easy to decipher dominate today.

- theatre

In the 1990s, the theater scene revived, especially in São Paulo. However, the importance of theater lags behind the international rank of the art of storytelling and essay writing by Brazilian authors today; the cinema and telenovelas as well as music have largely taken over its role.

Kulturkampf since 2019

Since 2019, under the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro , numerous intellectuals have protested against the restrictive cultural policy, against attempts at censorship and the evangelicals' homophobia. Musicians, writers and artists who had fought against the military regime in their youth, such as Chico Buarque, and Brazilians living abroad such as Rafael Cardoso, became spokesmen for the opposition.

Afro-Brazilian literature

In addition to the mulatto classics of Brazilian literature such as Machado de Assis and other authors of the 20th century, from the 1960s there was an increased preoccupation with the situation of authors of African origin, the Afro-Brazilians . It was not only important to determine the characteristics of these literary achievements, but also to work out the elements of one's own black consciousness . So many words from African languages have found their way into Brazil's vocabulary. Memories of other cultural elements of African origin such as the Candomblé are also reflected in the literature. Since the late 1990s, more and more authors from the precarious periferias of São Paulo have had their say, expressing themselves in oral and jargon-influenced texts on topics such as poverty, discrimination and violence. Well-known representatives of Afro-Brazilian literature are Geni Guimarães (* 1947), Lepê Correia (* 1952), Paulo Lins , who in Cidade de Deus (1997; German “The City of God” 2006) describes the downgrading of a social settlement to a favela, and Cuti , who in his work Consciencia negra do Brasil (2002) presented the works that are generally considered to be major works for the development of an Afro-Brazilian consciousness. The feminist author Marilene Felinto (* 1957) appeared as a critic of social exclusion . Alberto Mussa (* 1961) ties in with Afro-American, Arab, but also indigenous narrative traditions and myths. In his book series Compêndio Mítico do Rio de Janeiro of five detective novels (1999-2018), he deals with the history of crime in Rio de Janeiro since the 17th century.

Afro-Brazilian literature now has its own magazines such as Afrodiásora . An introduction to contemporary Poesia Negra , published by Moema Parente Augel, is available in German and Portuguese . Augel had previously edited an anthology with prose negra translated into German .

Indigenous literature

As early as 1957, Alberto da Costa e Silva published an anthology with Indian myths. But the indigenous Brazilian literature only made itself felt in the 1970s. The indigenous Brazilian literature includes both the poetry of its representatives who have entered Brazilian society and the promotion of the written fixation of previously oral tradition , the knowledge of "the ancients" that must be passed on to younger generations. This is now institutionalized and takes place with corresponding political and ecological demands, so at Kaká Werá .

An important representative is Daniel Munduruku , a member of the Munduruku who has written over 50 books, many of which are books for children and young people. In 2013 he was the only indigenous author to be present at Brazil's guest country appearance at the Frankfurt Book Fair. The indigenous feminist activist Eliane Potiguara (* 1950) is also active in literature .

Literary life

Reading is a minority phenomenon in Brazil. In 2008, a statistical mean of just 1.8 books was read per capita, including advice literature. Few large publishers are in the hands of family businesses.

The most important institution for literary academic life is the Academia Brasileira de Letras (ABL). Regional language and literature academies exist such as B. the Academia Catarinense de Letras . The Prêmios Literários da Fundação Biblioteca Nacional are awarded in several categories. The highly renowned Prêmio Machado de Assis , awarded since 1941 by the Academia Brasileira de Letras for the life's work of a Brazilian writer, is endowed with R $ 100,000. The most important Brazilian literary prize, the Prêmio Jabuti de Literatura , has been awarded by the Brazilian Chamber of Booksellers Câmara Brasileira do Livro (CBL) since 1959 in 21 categories. The Prêmio Juca Pato , awarded since 1963 by the Folha de São Paulo and the Brazilian Writers' Association União Brasileira de Escritores (UBE), honors the book that best expresses Brazilian culture; the author also receives the honorary title Intelectual do Ano .

Internationally known is the most important Brazilian literary festival, Festa Literária Internacional de Paraty , which has been taking place since 2003 and is now also attended by German authors such as B. Ingo Schulze participate. In 2011 there was a heated discussion there about how Brazilian literature, for B. could internationalize through translation funding programs. Through these and other activities such as scholarships and colloquia, the literary environment has become considerably more professional in recent years. Marcelo Backes (* 1973) translated more than 15 authors of German-language literature into Brazilian, including works by Goethe, Heine, Nietzsche, Kafka, Schnitzler, Brecht, Günter Grass, Ingo Schulze and Juli Zeh, and wrote A arte do combate (2003), a history of German literature.

After the financial crisis of 2008/09 and the economic crisis of 2014, the indebtedness of many publishers and bookstores grew. Small self-publishers are gaining in importance.

Publishing and book trade

The Brazilian book market is now the ninth largest in the world. Brazil produces 50% of all books in Latin America. In 2011 over 58,000 titles appeared. Around 20 million members of the new middle classes have discovered the book for themselves since 2000. Yet every Brazilian reads an average of only four books a year. The government supports translators and foreign publishers in the transmission and publication of Brazilian literature. In 2013, 132 million books will be distributed to 120,000 schools through the Programa Nacional do Livro Didático . The Brazilian e-book market is said to be one of the largest in the world; Estimates assume 11,000 to 25,000 domestic titles.

Every year around 15 book fairs take place in Brazil, the largest of which takes place alternately in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo ( Bienal do Livro de Rio de Janeiro and Bienal do Livro de São Paulo ). The 2013 fair in Rio de Janeiro attracted 750,000 visitors (for comparison: Frankfurt Book Fair 2012: 280,000). Every child receives a voucher for a book with the entry ticket. In addition, various reading promotion and other student programs take place. There are also book fairs in the northeast, such as the Pernambuco Biennale , the third largest in the country. In 2013, Brazil was the guest country at the Frankfurt Book Fair for the second time since 1994 .

Around 500 publishers can be found on the Brazilian book market, with Portuguese and Spanish publishers still dominating at the moment. The largest Brazilian companies include Companhia das Letras , Martins Fontes , Sextante , Grupo Editorial Record , which operates a joint venture with the Canadian Harlequin Books , and Objetiva .

A special form are the small-format booklets known as Literatura de Cordel , the folhetos , with Brazilian folk literature : small strophic stories and news that were often the only mass medium available in parts of the country. The name of this form of literature is derived from the fact that these folhetos are offered for sale with brackets on strings. Even comics play an important role, the author of the short story Luis Fernando Veríssimo.

The Internet is becoming increasingly important as an inexpensive medium for distributing literature, especially small forms such as creative blogs, series feuillitons and novels. Indigenous literature is also increasingly being disseminated via the Internet.

See also

literature

Bibliographies

- Klaus Küpper : Bibliography of Brazilian Literature. Prose, poetry, essay and drama in German translation. With a foreword by Berthold Zilly . Edited by the Archives for Translated Literature from Latin America and the Caribbean. Küpper, Cologne, Ferrer de Mesquita, Frankfurt / M. 2012, ISBN 978-3-939455-09-7 (TFM). + 1 CD-ROM.

- Rainer Domschke u. a. (Ed.): German-language Brazilian literature. 1500-1900. Bibliographic Directory. Editoria Oikos, São Leopoldo 2011, ISBN 978-85-7843-158-7 .

Collections of articles

- Wolfgang Eitel (Ed.): Latin American literature of the present in single representations (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 462). Kröner, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-520-46201-X .

- Mechtild Strausfeld (ed.): Brazilian literature. (= Suhrkamp Taschenbuch. 2024). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-518-38524-0 .

Anthologies

- The herons. Brazil in the tales of its best contemporary authors. Selection and translation: Curt Meyer-Clason . (= Spiritual encounters. Vol. XVIII.) Erdmann Verlag, Herrenalp 1967.

- Erhard Engler (Ed.): Explorations. 38 Brazilian storytellers. Volk und Welt publishing house, Berlin 1988.

- Christiane Freudenstein (Ed.): Brazil tells. Fischer paperback, Frankfurt 2013.

- Aluísio de Azevedo, Lima Barreto, Machado de Assis: The blue monkey: and other Brazilian stories. Special edition 2013.

Lexica, literary history, literary criticism

German

- Susanne Klengel, Christiane Quandt, Peter W. Schulze, Georg Wink (eds.): Novas Vozes. On Brazilian literature in the 21st century. Frankfurt a. M. 2013.

- Michael Rössner (ed.): Latin American literary history. 2nd ext. Edition. Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, pp. 93 ff., 124 ff., 190 ff., 225 ff., 372 ff., 482 ff.

- Thomas Sträter : The Brazilian Chronicle (1936–1984). Studies on modern short prose. Edições UFC, Fortaleza 1992, ISBN 85-7282-001-9 . ( Cologne writings on the literature and society of the Portuguese-speaking countries. 5).

- Dietrich Briesemeister (ed.): Brazilian literature of the time of military rule (1964–1984). Vervuert, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-89354-547-6 . ( Bibliotheca Ibero-Americana. 47).

- Dietrich Briesemeister: The Reception of Brazilian Literature in German-Speaking Countries , in: José Maria López de Abiada, Titus Heydenreich (ed.): Iberoamérica: historia, sociedad, literatura: homenaje a Gustav Siebenmann. Munich 1983, pp. 165-192; Revised version in: Miscelânea de estudos literários: homenagem a Afrânio Coutinho , Rio de Janeiro, pp. 141–164, with the title A recepção da literatura brasileira nos países de língua alemã .

- Ulrich Fleischmann , Ellen Spielmann: The Brazilian literature. In: Critical lexicon for contemporary foreign-language literature - KLfG. Edition text + kritik , Munich. Loose-leaf edition. ISBN 978-3-86916-162-4 .

- Wolfgang Geisthövel : Brazil. A literary journey . Horlemann, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-89502-355-2 .

- Brazilian literature. In: The Brockhaus Literature. Vol. 1. Mannheim 1988. pp. 287-289.

Portuguese

- Palmira Morais Rocha de Almeida: Dicionário de autores no Brasil colonial. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Colibri, Lisboa 2010, ISBN 978-989-689-045-2 .

- Assis Brasil : História Crítica da Literatura Brasileira. 4 volumes. Companhia Editora Americana, Rio de Janeiro 1973.

- Antônio Cândido : Presença da Literatura Brasileira. Difusão Européia do Livro, São Paulo 1968.

- Afrânio Coutinho (Ed.): A Literatura no Brasil. 6 volumes. Ed. Sul Americana, Rio de Janeiro, 1956 ff.

- A Literatura Brasileira. 6 volumes. Ed. Cultrix, São Paulo 1964 ff. - Volume 1: J. Aderaldo Castello: Período Colonial. Volume 2: Antônio Soares Amora: O Romantismo. Volume 3: João Pacheco: O Realismo. Volume 4: Massaud Moisés: O Simbolismo. Volume 5: Alfredo Bosi: O Pré-Modernismo. Volume 6: Wilsons Martins: O Modernismo.

- Luiza Lobo: Guia de escritoras da literatura Brasileira. EdUERJ, 2006. ISBN 978-857-511-099-7 .

- José Veríssimo : História da literatura brasileira. De Bento Teixeira (1601) a Machado de Assis (1908). Livraria Francisco Alves, Rio de Janeiro; A Editora, Lisboa 1916. (Most recently: Letras & Letras, São Paulo 1998, ISBN 85-85387-78-5 ). ( dominiopublico.gov.br PDF; 1.37 MB).

- Nei Lopes: Dicionário literário afro-brasileiro. Pallas, Rio de Janeiro 2011, ISBN 978-85-347-0412-0 .

English

- Irwin Stern (Ed.): Dictionary of Brazilian literature. Greenwood Press, New York 1988, ISBN 0-313-24932-6 .

Publishing

- Hallewell, Laurence: O livro no Brasil: sua história. São Paulo: EdUSP 2005.

Web links

- Brazilian literature , short introduction, in German, on Brazilportal.ch

- LiteraturaDigital. Biblioteca de Literaturas de Língua Portuguesa. Retrieved on April 30, 2019 (Portuguese, contains: information on over 20,000 authors, over 7,200 digitized works, as of 2019).

- biblio.com.br. A Biblioteca Virtual de Literatura. Biografias dos maiores autores de nossa língua. Retrieved April 30, 2019 (Portuguese, contains: biographies and digital copies as online texts).

- Fundação Biblioteca Nacional. Biografias de Autores. Retrieved April 30, 2019 (Portuguese, contains: biographies and digital copies as online texts).

- Enciclopédia literatura brasileira. Itaú Cultural, accessed April 30, 2019 (Portuguese, contains: biographies and bibliographies, terms, works).

- Jornal Rascunho , magazine on Brazilian literature

- Digitized earlier works

- Facsimile of Hans Staden's Historia , Marburg 1557 .

- Gabriel Soares de Sousa: Tratado Descritivo do Brasil in 1587. Laemmert, Rio de Janeiro 1851 .

- Casimiro de Abreu: As primaveras. 1859 in the Portuguese WikiSource.

Individual evidence

- ↑ A transcription in the original and today's writing can be found in the Portuguese WikiSource.

- ↑ Hans Staden: Warhaftige Historia. Two trips to Brazil (1548–1555). Historia de duas viagens ao Brasil. Critical edition by Franz Obermeier; Fontes Americanae 1; Kiel 2007, ISBN 3-931368-70-X .

- ^ Franz Obermeier: Images of cannibals, cannibalism in pictures. Brazilian Indians in Pictures and Texts from the 16th Century (PDF; 114 kB). In: Yearbook of Latin American History. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna, 38. 2001, pp. 49–72.

- ↑ Bento Teixeira in: Enciclopedia Itaú Cultural (Portuguese)

- ↑ a b Brazilian literature. 1988, p. 287.

- ^ Brazilian literature in the Brazil portal, accessed September 19, 2013.

- ↑ Heinz Krumpel: Enlightenment and Romanticism in Latin America. A contribution to identity, comparison and interaction between Latin American and European thinking. Bern u. a. 2004, p. 236 f.

- ↑ a b c Brazilian literature. 1988, p. 288.

- ↑ Dietrich Briesemeister: THe Brazil studies in Germany. German Lusitanist Association V., first published in 2000, accessed August 7, 2010.

- ^ Rössner: Latin American literary history. 2002, p. 230 ff.

- ↑ Thelma Guedes, Pagu - Literatura e Revoluçao . Atelié Editorial 2003

- ↑ [N.Hi .:] Graciliano Ramo: Memórias d cárcere , In: Kindlers new literature lexicon, Munich 1996, vol. 13: Pa – Re, p. 930 f.

- ^ Regina Célia Pinto: The NeoConcrete Movement (1959–1961). ( Memento of June 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: www.arteonline.arq.br, English [accessed on November 29, 2018].

- ^ Augusto Boal: Theater of the Oppressed: Exercises and games for actors and non-actors. edition suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1989

- ^ Anne Vogtmann: Augusto Boals Theater of the Oppressed: Revolutionary Ideas and Their Implementation. An overview. (PDF, 370 kB). In: Helikon. A Multidisciplinary Online Journal. (1), 2010, pp. 23-34. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ↑ Modern Brazilian Theater. (Excerpt, section theses, University of Cologne).

- ↑ Jens Jessen: The violence of modernity. In: The time. No. 41, September 2013, zeit.de

- ↑ Ulrich Rüdenauer: Don't trust anyone over 100. In: Der Tagesspiegel , October 9, 2013 ( tagesspiegel.de ).

- ↑ Finally, the fourth volume: The Book of Impossibilities. Berlin, Hamburg 2019.

- ^ So the TAZ : taz.de

- ↑ Literature Festival 2015

- ^ German: Landscape with Dromedary , 2013.

- ↑ Friedrich Frosch: A polyphony with an uncertain route: Brazil's literature today. In: Klengel u. a. 2013, p. 40 ff.

- ↑ Uta Atzpodien: Scenic negotiation: Brazilian theater of the present. Transcript, 2005.

- ↑ Brazil's U-turn in culture , conversation by Peter B. Schumann with Bernardo Carvalho on dlf.de, April 5, 2020.

- ↑ Patricia Weis-Bomfim: Afro-Brazilian literature - history, concepts, authors , Kempen 2002.

- ↑ MP Augel (eds.), Black Poetry - Poesia Negra: African Brazilian seal of the present. Portuguese - German , amazon Kindle, 2013

- ↑ Blog: Mundurukando (Portuguese).

- ↑ Friedrich Frosch: A polyphony with an uncertain route: Brazil's literature today. In: Klengel u. a. 2013, p. 23.

- ↑ Klengel u. a. 2013, introduction to the ed., P. 10.

- ↑ a b On the jump into the world. In: NZZ. International edition, September 18, 2013, p. 23.

- ↑ Camila Gonzatto: The Brazilian publishing industry: Growth and digital media , on the website of the Goethe-Institut Brazil July, 2013.

- ↑ Eliane Fernandes Ferreira: From bow and arrow to the "digital bow": The indigenous people of Brazil and the Internet. transcript Verlag 2009. ISBN 978-3-8376-1049-9 .

- ↑ a b Klaus Schreiber: Review in: Information resources for libraries IFB 12-4 ( ifb.bsz-bw.de PDF; 42 kB)

- ↑ Maria Eunice Moreira: História da literatura e identidade nacional brasileira. In: Revista de Letras. Volume 43, No. 2, 2003, pp. 59-73. ISSN 0101-3505 , JSTOR 27666775 .