Salvador (Bahia)

| Município de Salvador Salvador da Bahia |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Coordinates | 12 ° 59 ′ S , 38 ° 31 ′ W | ||

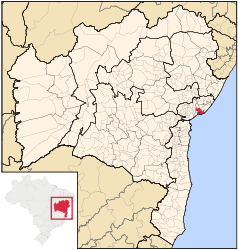

Location of the municipality in the state of Bahia Location of the municipality in the state of Bahia

|

|||

| Symbols | |||

|

|||

| founding | 29th March 1549 (age 471) | ||

| Basic data | |||

| Country | Brazil | ||

| State | Bahia | ||

| ISO 3166-2 | BR-BA | ||

| Metropolitan area | Salvador metropolitan area | ||

| structure | 10 prefectures (since 2016), 163 bairros (2017) |

||

| height | 8 m | ||

| Waters | Atlantic | ||

| climate | tropical, Af | ||

| surface | 693.8 km² | ||

| Residents | 2,675,656 (2010) | ||

| density | 3,856.4 Ew. / km² | ||

| estimate | 2,872,347 (July 1, 2019) | ||

| Parish code | IBGE : 2927408 | ||

| Post Code | 40010-41950 | ||

| Telephone code | (+55) 71 | ||

| Time zone | UTC −3 | ||

| Website | salvador.ba.gov.br (Brazilian Portuguese) | ||

| politics | |||

| City Prefect | ACM Neto (2017-2020) | ||

| Political party | DEM | ||

| Culture | |||

| City festival | March 29th (foundation festival) | ||

| economy | |||

| GDP | 62,717,483 thousand R $ 21,231 R $ per person (2017) |

||

| HDI | 0.759 (high) (2010) | ||

Salvador , officially Município de Salvador , is the third largest city in Brazil after São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro . The historic name of the coastal city is São Salvador da Bahia de Todos os Santos (Holy Savior on All Saints Bay ). The name goes back to the day the first seafarers arrived, November 1, 1501. The name Bahia was also in use for the city until the middle of the 20th century.

Salvador has an estimated population of around 2.87 million as of July 1, 2019, is the capital of the northeastern state of Bahia and was the capital of Brazil until 1763. Salvador is the archbishopric of the Archdiocese of São Salvador da Bahia . It is an internationally recognized commercial and economic center with an oil and sugar refinery as well as cotton, tobacco and cocoa processing.

geography

Salvador is built on different levels of a mountain range that divides the city into an upper town (cidade alta) and a lower town 70 meters below (cidade baixa) . To get from one part to the other, you can use the Lacerda elevator or one of the many bus routes.

climate

| Salvador de Bahia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Salvador de Bahia

Source: wetterkontor.de

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

history

The best-known Indians of this coastal region until the European occupation were the Tupinambá and even earlier Indians from the Tupi , Tupina and Tupinae tribes , as reported by the early seafarers Martim Afonso de Souza and Simão Alcazaba in 1533 and 1535. On November 1, 1501, there was already trade between the Portuguese seafarers under the direction of Gonçalo Coelho and the Indians of the Eurotupinambá tribe at a place on the coast that was called the "place of the patron ", today's Barra lighthouse . It is due to the influence of the Jesuits that the Indios were spared slavery and instead Angolan Africans were kidnapped and taken to Brazil. The first 50 African slaves lived in Bahia as early as 1551 and thus laid the foundation stone for a city of Salvador that is still influenced by Africa today.

The occupation of Brazil

Long before Salvador was granted city rights, the region had been populated around 1510 by the survivors of a shipwrecked French ship. Its crew also included Diogo Álvares Correia, the famous Caramuru (translated: lamprey ) or "son of thunder" - he earned the respect of the Indians with his rifle when he shot a flying seagull with it. The chief Morubixava Taparica gave him his eldest daughter, Paraguaçu, as his wife. In 1534 the chapel Nossa Senhora das Graças (Our Lady of Grace) was built because Diogo Álvares and his wife, Catarina Paraguaçu, lived there. In this church, in the Graça district of the same name, Catarina Paraguaçu was buried standing near the altar. This place is clearly visible with a grave slab. About the grave of Caramuru there is only the assumption that it could be in the "Mosteiro de Jesus", the former Jesuit monastery and today's cathedral .

In 1536 the Portuguese Francisco Pereira Coutinho reached the area, which was given to him by the Portuguese King John III. when property was awarded. This area is located roughly in what is now the Barra district. The Indians living there revolted against Francisco Pereira Coutinho several times because he treated them cruelly and unjustly. Escape and return followed, and in the end he was killed by the Indians in 1547 and eaten during a great festival.

The first bishop of Brazil, Dom Pedro Fernandes Sardinha, had a no less dramatic end. He was appointed Bishop of Salvador in 1552, but died a gruesome death in 1556. After his inauguration, he quickly fought with the Jesuits, including a. because he disapproved of the practice of allowing Indian instruments to be used by children raised by Christians and of using native melodies in Christian cults. But it was precisely here that the Jesuits saw the opportunity to win Indians over to the Christian faith. His quarrel with the Jesuits ended with his death on July 16, 1556. He was shipwrecked off the coast of Alagoa and was eaten by the Indios Caetés. Furthermore, the Catholic official church criticized the increasingly rampant polygamy :

“The married men who came to Brazil without their families indulged in the same immoral life as everyone else: all over the [Brazilian] coast you can find men who are married in Portugal and they live here in great sin great disadvantage for their wives and children ... "

The city was founded on March 29, 1549 by Tomé de Sousa . The numerous freshwater springs, many of which still function today, were decisive for the founding of the city at this point. Caramuru had been commissioned by the Portuguese crown to give Tomé de Sousa all possible assistance in this mission. A fortress called São Salvador was built on the orders of the Portuguese king. With Tomé de Sousa, Salvador reached more than a thousand Portuguese. Among them the first Jesuits , Manuel de Nóbrega , João Aspilcueta Navarro, Leonardo Nunes and others. In addition to various disputes between the French and Portuguese, Salvador was occupied by the Dutch in 1598, 1624 to 1625 and 1638. The main means of export in the 17th century was sugar. The slaves had to work on the plantations and sugar cane fields in the surrounding area, the so-called Recôncavo . Due to the sugar trade, Salvador was the largest city in the southern hemisphere until 1650. One of the larger revolts against the oppressors arose in 1835 by Muslim slaves. Salvador's first bloom ended when the city lost its role as the capital of Brazil to Rio de Janeiro in 1763.

Salvador in the 18th century

The Tailors Revolt (Revolta dos Alfaiates)

Inspired by the French Revolution of 1789 , the idea of independence from the Portuguese crown spread across all layers of Baian society. Unlike the revolutionary beginnings in Minas Gerais in 1792, whose leader Tiradentes was murdered by representatives of the Portuguese crown, the Baian revolution in 1798 continued with the demand for the end of slavery. But this uprising, also known as the “Baian Conspiracy” (Conjuração Baiana), ended in 1799 with the execution or deportation of the leaders. All the upper-class sympathizers of the idea of independence, such as the journalist and doctor Cipriano Barata, who was at the forefront of inciting ordinary people against Portuguese oppression, and the priest Agostinho Gomes pulled their heads out of the noose in good time.

Taxes on the Portuguese crown were too high and the common people wanted better living conditions, because since the country's seat of government was moved from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro in 1763, they had led a life in miserable conditions. Bahia was caught in an economic crisis, and crime and looting were rampant.

All over Salvador, the demands of the freedom thinkers could be read through notices that came from the pen of the soldier Luís Gonzaga das Virgens:

- Independence of Kapitanats Bahia

- Introduction of a republic

- Independence for trade and the opening of all ports

- a pay of 200 Réis per day

- and the end of slavery

Gonzaga was arrested on August 24, 1798. An attempt at liberation, led by the soldier Lucas Dantas de Amorim and the tailors João de Deus do Nascimento and Manuel Faustino de Santos Lira, failed.

The movement was supported by the "public relations work" of the Masonic lodge "Cavaliers of Light". But when the names of their members appeared in indictments, they all bought themselves off through false witnesses and alibis. Unlike the Freemasons, the free and enslaved blacks remained loyal to the movement; their hopes for the end of their oppression were too great.

After Gonzaga's arrest, Queen Maria I of Portugal interrogated 59 people, many of whom were tortured. 34 of this group were tried, 4 blacks were sentenced to death. They were driven through the streets of Salvador to their place of execution on November 8, 1799. 80% of the onlookers were blacks, who quietly paid their heroes the respect they deserved. The delinquents Manuel Faustino and Lucas Dantas refused the sacraments. In contrast to their accusers and the Portuguese queen, they are free from guilt.

On November 8, 1799, Manuel Faustino, Lucas Dantas, João de Deus and Luís Gonzaga were hanged on the Praça da Piedade, where slaves and criminals were regularly pilloried or hanged, and their heads and other body parts were put on sticks on display throughout the city. All those not sentenced to death were deported after receiving 500 lashes in the pillory. It may only be a coincidence, but the head of Manuel Faustino, who had renounced the sacraments of death by the Franciscan clergyman, was put on impaled on the Cruzeiro de São Francisco right in front of the Franciscan church. Five days later, members of the Santa Casa de Misericordia Hospital, an institution for the destitute that was also responsible for their funerals, were allowed to bury the body parts in an undisclosed location.

At every corner of the Piedade square there is a bronze bust in memory of the four who were executed.

Salvador in the 19th century

On December 29, 1812 the battle of the USS Constitution against the HMS Java took place off the coast of Salvador .

At the end of the 19th century, the cityscape changed radically when it was filled in for the purpose of port construction. Even the customs building, which now houses the Mercado Modelo, was partially surrounded by the sea. When visiting the lower town, note that the old buildings from the colonial era are located at the foot of the upper town. Towards the sea there are only buildings from the time after the embankment. This can be seen well on the panorama picture. You can also see the old cathedral, which had to give way to the tram in 1933. When the picture was taken in 1860, it was in serious disrepair and had no towers. After its demolition, the former Jesuit church was converted into a cathedral. On the right of the picture you can see the São João Theater, which was badly damaged during the bombing and torn down years later after a fire.

First shipload of ice arrives in Salvador

In 1834 the first shipload of ice blocks from Boston reached the port of Rio de Janeiro. Around the same time, ice cream was also being sold in the lower town of Salvador, near the former gold market. A billboard pointed out its valuable medicinal effect:

Hope "[...] We, the audience in the consumption of this great that antidepressant used to be, which is a great way to alleviate the large number of occurring here gastric diseases. Many other ailments can be cured with it, according to top university scholars. In addition to its medicinal properties, it is extremely refreshing to take with drinks in a country as warm as ours. [...] "

The price of ice cream was exorbitantly high due to transportation and complicated storage. Initially, it was buried in the ground with an insulating coat made of wood wool and could thus be preserved for up to five months.

Revolt of Muslim slaves (Revolta dos Malês)

The word Malê comes from the Yoruba language and means Muslim . These slaves were also known as nagô in Bahia . The word "nagô" comes from a language that is spoken in Benin - the country of origin of their abduction. The revolt was prepared, but betrayed, in the basement of house No. 2 in Ladeira da Praça (street that runs between Praça Municipal and the fire department of Baixa dos Sapateiros). There were many of these houses where males met for meals and spoke Arabic. This house was known as such a meeting place. The uprising was planned for January 26, 1835, but inevitably began on the evening of January 25, 1835 when a judge, a policeman and two soldiers investigated the charges and stormed the house in question. They were not a little surprised to be overrun by over 50 Malês, most of whom were armed with sabers. Many Malês fled through the garden and alerted their like-minded fellows.

Now the storming of the town hall, in whose cellar the prison was housed, began to free the compatriot Pacífico Licutan. He was locked up there because his “master” was in debt and Pacífico was being kept as a “pledge” for auction. The storm failed; there were deaths on both sides, with the Malês with their sabers clearly at a disadvantage. The Malês withdrew and ran screaming to Campo Grande to mobilize another group that had settled there. Forte São Pedro and various police stations were attacked. Over the Pelourinho and the lower town they tried to regroup with slaves from the sugar cane plantations, but were stopped and massacred by the military in Água de Meninos; many refugees drowned. In the end, 70 rebels and 10 soldiers were killed. At the time, Salvador had 65,000 inhabitants, 40% of whom were slaves. So the fear of a new revolt persisted for a long time.

Eduardo Baraúna Carigé and the end of slavery in Bahia

From 1878 voices against slavery became louder all over Brazil and began to concentrate in Salvador in 1883 with the establishment of the Baian Liberation Society (Sociedade Libertadora Baiana). The medical school at Pelourinho did not play an insignificant role in the fight against slavery. Their opponents now met from all walks of life; the most militant among them was the doctor and journalist Eduardo Baraúna Carigé (Iô Iô Carigé) (1851–1905). Even if the society only had 30 members, they had enormous social influence with well thought-out strategies against the so-called ruling class.

The name Carigé appears again and again in newspaper reports and official police documents. So on April 10, 1883, when he and like-minded people knew how to prevent the transport of the slave Lino Caboto to Rio de Janeiro, as it was forbidden by law to transport slaves from one province to another. But first and foremost, Carigé owed hundreds of slaves their freedom because he gave them legal advice and found them well-meaning lawyers. The main focus was on formal errors such as the lack of parent information or a registration number. In addition, a law of 1831 made it illegal to import slaves into Brazil.

The so-called masters of the slaves did not attend to the court hearings, but only reacted to the publications of the judgments in the Gazeta da Bahia. Appeals before the next higher instance were not always unsuccessful. But even if the prospects for freedom fought for in court became increasingly rare, more and more slaves felt motivated to take the legal route in favor of a better fate.

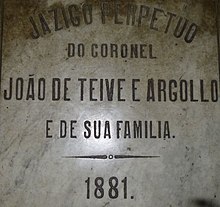

Carigé often argued polemically with the gentlemen, for example with the family of João de Teive e Argollo, whose grave slab can be found on the right side of the altar of the Franciscan church. In addition to sugar plantations, this family owned the Fazenda Água Cumprida, which later became the town of Simões Filho . His son, also João de Teive e Argollo, was reported by the slave Silvestre in 1887 that he had killed the slave Damião with a club. Carigé intervened and called for a police investigation on behalf of the Liberation Society, but this did not produce any evidence against Argollo. Even an investigation requested by a public prosecutor did not provide any evidence that the slave Damião was actually killed. It is possible that the slave Silvestre used the death of Damião (who probably died from a chronic illness) as an excuse to free himself from slavery, a form of revolt by slaves against their masters that was becoming more and more common at the time.

Eduardo Baraúna Carigé was repeatedly threatened with death and accused of having enriched himself with the slaves' little money. In fact, however, he died impoverished at the age of 54. In folk songs that are still known today, he is celebrated as a hero against slavery.

Salvador in the 20th century and modern

Bombing of Salvador

In 1910 a dispute broke out between the region's quarreling oligarchs over the upcoming election as governor of Bahia. This political dispute had the consequence that the governor João Ferreira de Araújo Pinho left office prematurely in 1911. José Joaquim Seabra and President Hermes da Fonseca , with whose help Seabra should be lifted into office, were in charge of this actually political move . Contrary to plan, however, it was not Seabra but his opponent Aurélio Rodrigues Viana who became the 13th governor of Bahia. This assumption of office was controversial, and so Viana occupied the parliament of Bahia and moved its seat to his birthplace Jequié in order to avoid sanctions by President Fonseca. Viana also had strategic points in the city occupied by the police and the military because the federal judge Paulo Martins Fontes declared all of Viana's actions to be illegal.

The armed conflict was programmed and Judge Martins tasked or intimated President Fonseca with restoring law and order in Bahia. On January 10, 1912, the responsible general Sotero de Menezes asked Viana for the last time to obey the supreme court judgment, but at 1:00 p.m. Viana responded that he would remain in office. At 1:30 p.m. Menezes announced that armed force would restore public order. At 1:40 p.m., the first two cannon shots (initially powder shots) were fired from Forte São Marcelo. The four-hour bombing of the city began at 2 p.m. The number of dead and injured was never determined. In addition to the destruction of public government buildings such as the Palácio Rio Branco at the Lacerda elevator and other historical buildings, the library with the city archive burned down. Original documents about the development of the city were lost forever. A day later, on January 11, 1912, Aurélio Rodrigues Viana gave in to pressure and resigned.

The bombing of Salvador as a sanction provoked an outcry in Brazil. This forced the Supreme Court to reinstate Viana as governor through a habeas corpus . This, in turn, completely unexpectedly resulted in the citizens of Salvador revolting against the authorities, attacking the police in Baixa dos Sapateiros and marching via Barroquinha to Castro Alves square to force its removal. Viana resigned a second time and took refuge in the Venezuela consulate. The President of the Regional Court of Bahia, Bráulio Xavier, took over government until the election of the new governor. From this election José Joaquim Seabra emerged as the 15th Governor of Bahia.

Pelourinho

One of the tourist centers is the Pelourinho , in English pillory, in the historic core of Salvador. Once a thoroughfare from the Jesuit monastery to the Carmel (Convento do Carmo), a pillory (Pelourinho) was erected there, as in many other parts of the city, where slaves were primarily flogged and displayed. However, other city residents, for example because of homosexual offenses or theft, could also be tied up there for a certain period of time. On the Pelourinho you can visit the Igreja do Rosário dos Pretos (Church of the Black Rosary). Today, many artists such as filmmakers, musicians, painters and writers live on and around the square.

Demographics

growth of population

Salvador is the largest city in the northeast and the eighth largest in Latin America. Only São Paulo , Mexico City , Buenos Aires , Lima , Bogotá , Rio de Janeiro and Santiago have more inhabitants .

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| 1872 | 129.109 |

| 1900 | 205.813 |

| 1940 | 290,443 |

| 1960 | 649.453 |

| 1980 | 1,501,981 |

| 2000 | 2,440,828 |

| 2010 | 2,676,606 |

| 2019 | 2,872,347 |

crime

The city's crime rate is comparatively high. In 2013, 2234 people were murdered in Salvador, which equates to a murder rate of 57.51 per 100,000 inhabitants (total Brazil: 27.1, Germany: 0.8). This makes Salvador the 13th most violent city on earth in 2014 (another ten Brazilian cities among the top 30), and in 2015 Salvador was 14th (out of 50 cities worldwide). Due to the growing demand despite the crime rate, hotel prices rose by up to 317% for the time of the soccer World Cup in 2014 .

Apart from a few pickpockets in the tourist areas of the city, the violence tends to take place in the peripheral districts late at night or early in the morning. 69% of the reasons for these excesses of violence are rivalries between drug gangs, unpaid bills by drug users, or disputes among crack addicts. Even bystanders occasionally get into shootings. Even then, the victims are almost exclusively favela residents . In the first weeks of February 2014, the number of bystanders peaked with five children between the ages of 1 and 14 killed.

Culture

The African influence on Salvador is still visible, in hardly any other region is the position of Afro-Brazilians so strong. This is particularly evident in the kitchen, music and religion. The Candomblé , which developed from the religion of the Yoruba and elements from other African faiths such as Bantu and Ifé and which has ostensibly syncretized with Catholicism, is the most widespread Afro-Brazilian religion and has its origin in Bahia. After the candomblé was banned until the 1970s, but the cult and rituals were still practiced, the Orixás , the revered deified heroes from the African myths of origin, had to find their equivalent in Catholic saints. So each and every Orixá was assigned a saint. Each Orixá is assigned certain characteristics, natural elements, food, minerals, colors, skills and mythical figures from African history. For example, the color red is assigned to Saint Barbara or the Orixás Oyá , Yansa or Xango . We owe detailed lists to the French ethnologist Pierre Verger .

religion

Salvador is the seat of the Archdiocese of São Salvador da Bahia .

Candomblé

Mãe Stella de Oxóssi, the spiritual director ( Iyalorixá ) of one of the most important institutions of the city's Candomblé , the Axé Opó Afonjá , vehemently advocates desyncretizing the Candomblé from Catholicism. In popular Catholicism, which is also very widespread, elements of Candomblé are adopted. The veneration of saints with its bombastic festivals Senhor do Bomfim and Santa Barbara is of great importance in the city's many churches.

An example of popular belief are the colorful ribbons (Fitinhas), which are offered to tourists and tied around the arm. In earlier times, the believer chose the ribbon with the color of the Orixá to which he was subordinate or the Orixá to be remembered that day. The band was attached to the right wrist with three knots. The recipient could wish for something for each node. The tape could no longer be removed, and if it fell off on its own, the three wishes were fulfilled.

In a country with many contrasts, it is not surprising that a Catholic church became the cradle of Candomblé. The Brazilian anthropologist Renato da Silveira explains that many slaves were brought to Brazil through the kingdom of Oyo . These Yoruba were sold by Africans from the north, Hausa , Tapa or Nupe and Bariba , until there was an uprising between 1820 and 1830 and Muslim traders now sold Yoruba. The kingdom of Oyo fell apart, and so members of royal families, priests and priestesses were enslaved to Brazil by Muslims. Through them, the African candomblé, which had been practiced for centuries, became a new religion in Brazil.

Ijexá , Ochosi , Shango and other deities are worshiped in the rite by the Shango priestess Iyá Nassô in the black district of Barroquinha. In the church of Barroquinha (see photo) an association of former slaves had been set up, the Sisterhood of the Good Jesus of Martyrdom. In their rooms inside the church the candomblé was practiced, hidden from the white society.

Capoeira

The Capoeira is a legacy of the time of slavery, and Salvador is considered the center of this fight (dance) sports.

Slaves and going to church

There was no prohibition on attending services in Catholic churches for slaves, because they only had access to a few churches. Here, too, they were not allowed to sit in the benches with the citizens of the city, which is reminiscent of the practice of South African apartheid . The panorama picture above, taken in the Igreja São Francisco , shows the room in the back of the building, near the entrance, where the slaves were allowed to stand. For this reason, “their” saints were also placed on altars near them. Here Benedict the Mohr on the left and the Virgin Iphigenia on the right.

Barroco na Bahia

The German-Brazilian project Barroco na Bahia has been working in Salvador since 1993 in the field of youth work with classical music. The socio-cultural approach of the project tries to convey the values of humanism in joint work with young people from middle and lower classes of the population with the help of vocal and choral music as well as joint work on larger projects up to opera.

Fonte Nova, Arena Fonte Nova and World Cup

The Arena Fonte Nova stadium was called Fonte Nova until 2013 and was previously called Estádio Octávio Mangabeira, named after the Governor of Bahias (1947–1951). The stadium held 60,000 people and was closed in 2007 after a tragedy. On November 25, 2007, part of the higher stand collapsed. Seven people fell 40 meters to their deaths. One day after the accident, 20 injured were treated in hospitals. Construction defects in the form of falling concrete parts and precarious hygiene had already been shown in the past. The stadium was demolished on August 29, 2010. The Arena Fonte Nova stadium, newly built for the 2014 World Cup , was opened on April 7, 2013 with the match between Bahia and Vitória (result 1: 5).

carnival

The Carnival in Salvador is the largest street carnival in the world with the Carnival in Rio and lasts six days and six nights. The festival in the carnival stronghold of Brazil begins on the Thursday evening before Ash Wednesday, and is advertised with annually changing slogans. The mayor hands over the city key to fat Rei Momo, the carnival king. Then one and a half million people flock to the streets - until Ash Wednesday. 19 kilometers will be cordoned off for the main train along the waterfront and through the city center. Large trucks with loudspeaker boxes (so-called " trios elétricos ") the size of a shipping container drive through the city, on top is the stage of a music group whose fans dance in the stream through the streets. Many well-known musicians from Salvador take part, including Olodum , Daniela Mercury , Timbalada and Ivete Sangalo . A second procession rolls through the narrow streets of the old town of Pelourinho during Carnival .

Attractions

Besides the carnival season, Salvador is a popular destination for tourists, including those from Germany. The city has a wealth of attractions:

- The old town around the so-called Pelourinho belongs since 1985 to the World Heritage of UNESCO .

Churches:

- The Church of Nosso Senhor do Bonfim : The most important religious center of Bahia for the Catholics of Salvador. The Christ statue Nosso Senhor do Bonfim (Our Lord of the Good End) and Nossa Senhora da Guia (Our Lady of the Leadership) came from Portugal in 1745.

- The São Francisco Church , built between 1686 and 1755, with magnificent interior decorations made of baroque Talha dourada and a large collection of blue tile paintings ( azulejos ), allegedly a gift from King John V of Portugal . The tiles representations of the cross passage provide in the upper floor hunting, marine and shepherd's scenes . The lower are a reproduction of the painting by the Flemish painter Otto van Veen and represent a natural ethics that the verses of Horace is removed. The church and monastery were to be restored in years of restoration from 2014. The church facades have been illuminated since the end of 2012.

- Not far from there is the Igreja da Ordem Terceira de São Francisco, known for its baroque facade .

- St. Sebastian Basilica

Additional:

- the Casa do Comerçio

- Monument to Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof , the founder of the international language Esperanto , in the city center.

- Elevador Lacerda : With the construction of this hydraulically operated elevator, the Lacerda family wanted to expand thecity center,which was originally located in the lower town ( Cidade Baixa ), to the south, i.e. into the districts behind the historic core of the upper town (Cidade Alta). It initially consisted of only two cabins. A tunnel was driven into the mountain range for access to the lower town. Antônio Lacerda could no longer witness the success of his building; he died impoverished. It was not until 1930 that the elevator was expanded with two additional cabins to form four, just as it is today in the silhouette of Salvador.

- The Escolar Restaurant . A restaurant on Pelourinho where young people can train to be waiters. Every evening there is a buffet with all the typical dishes of the region.

- Mercado Modelo : Former customs clearance building into which the Mercado modelo was relocated after it was decommissioned. Its market hall fell victim to a fire in 1969 and had to be completely demolished. In its place there is now an imposing monument by Mário Cravo Junior. The basement of the former customs clearance building has never been, as the popular saying goes, a dungeon for arriving slaves who stood knee-deep in the water, chained to rings in the walls. In reality, perishable food was stored there. Today the building is used as a tourist market with over sixty shops where many Brazilian souvenirs can be bought. It is located right on the edge of the center (Comercio).

- The Barra lighthouse at the entrance of the Baía de Todos os Santos , where you can watch the sunset.

- The zoo in the Ondina district.

- Palácio de Ondina : Seat of the Governor General in the Ondina district near the zoo .

Celebrations and memorial days

The outstanding festivals and memorial days of Salvador are mostly of a religious nature due to the Catholic character of Brazil.

- January 1st: In the Bom Jesus dos Navegantes (Lord Jesus the Navigator ) procession , on January 1st, boats and ships sail through the Baia de Todos os Santos to the Boa Viagem chapel (Bon Voyage). On board a ship is the statue of Christ from the Conceição da Praia church.

- 2nd Thursday in January: In a procession that counts up to a million participants dressed in white, people march through the streets of Salvador on an eight-kilometer route. Many people wear vases on their heads filled with perfumed water and white flowers. In front of the church Nosso Senhor do Bonfim (Our Lord of the Good End) the stairs are ritually cleaned with the water from the vases.

- 14 days before Carnival, the church is cleaned from Itapuã beach.

- June 24th: St. John's Festival . Singers from all over the country meet in the exhibition park for an exuberant party.

- July 2nd: Bahia becomes independent from the Portuguese crown. The parade took place for the first time in 1824 to draw attention to the continuing social injustices.

- September 27th: Feast of the brothers Saints Cosmas and Damian . The believers prepare Caruru (see below) and give sweets to the children. The festival takes place around the Santa Barbara market on the famous Baixa dos Sapateiros street, also Avenida José Joaquim Seabra, in the historic center of Salvador. The believers of Candomblé also celebrate this like most other festivals.

- November 29th to December 8th: Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception) memorial day. This festival takes place in a church of the same name at the foot of the Lacerda elevator. Many stalls serve dishes and drinks with the sounds of reggae , pagoda and samba .

- December 4th: Saint Barbara . Many believers, especially those of Candomblé, wear red clothes.

- December 13th: Saint Lucia of Syracuse

kitchen

Bahia's cuisine clearly shows Creole and African influences. Its basic ingredients include Dendê palm oil, coconut milk, prawns and mussels, local spices such as pepper and green coriander. Typical dishes include:

- Vatapá : a kind of puree made from dried and fresh crabs and small pieces of fish. Other ingredients are cashew nuts, peanuts, onions, fresh coriander, fresh ginger root, palm oil, beans and coconut milk. The dish is served with a porridge made from rice flour and coconut milk and topped off with pepper to taste.

- Moqueca : a stew made from fish (de peixe), squid (de lula) or dried fish (de bacalhau) and coconut milk, palm oil, coriander, parsley, tomatoes, red peppers, garlic and onions. Rice and pimenta, a spicy seasoning sauce, are served with it.

- Acarajé : a ball made from black bean pulp and shrimp , fried in hot palm oil. In Salvador you can get it on almost every street corner.

- Sarapatel: The liver and heart of pork or mutton are cooked with fresh blood. Tomatoes, peppers and onions also belong in the Sarapatel.

- Carurú: Crabs are combined with a hot sauce made from red pepper and okra.

- Churrasco : next to the feijoada the favorite dish of the Brazilians, not only in Bahia. Beef and other pieces of meat or even a whole ox are grilled on a spit over an open coal fire. A kind of vinaigrette with lots of chopped tomatoes and onions as well as rice and beans is served with it.

economy

traffic

With the Salvador-Magalhães airport, the city has an international airport with direct connections to North America and Europe .

Local public transport is largely based on buses.

tram

In the lower town wagons drove, in whose construction the companies Siemens , Falkenried (Hamburg) and Böker & Co (Berlin-Lichterfelde) were involved. Popular uprisings are associated with the existence of the tram . On October 5, 1909, a blind man was hit by a tram; a mob then destroyed 14 trains as well as numerous street lights, a substation and a natural gas distributor. In the 1950s a tram derailed on the Praça Municipal at Elevador Lacerda , broke through the wall of the Cubanas ice cream parlor and stopped with its front wheels over the slope. The accident ended without injuries.

In an incident in the Roma district in 1952 in which a tram collided with a bus and caught fire, twelve people were burned to death. A group of nuns, including Irmã Dulce , who was beatified in 2011, smashed the windows of the tram, rescuing those trapped . Wagons that drove from the lower to the upper town were regularly the victims of children who rubbed the tracks with soap at the steepest points.

The first electric tram was inaugurated in 1897 and replaced the wagons that had been pulled by donkeys since 1860. The electric tram ran for the last time in 1961. There is no longer any record of the exact end. The route network consisted of 37 lines on which, in addition to the usual wood class, a salon tram for celebrations, an ambulance tram and a funeral tram ran.

Tram, elevator Lacerda and Plano Inclinado Gonçalves were public transport under North American control and performed their service under the name Companhia Linha Circular de Carris da Bahia . Anti-Americanism that had been smoldering for a long time broke out when it was discovered that foreign workers from the Chiristiani & Nielsen company were said to have draped a toilet block with a Brazilian flag during the renovation of Plano Inclinado Gonçalves. The uprising broke out in front of the Franciscan monastery in the evening of October 6, 1930. The next day, 83 wagons were burned out.

In 1933 the old cathedral had to give way to a turning loop for the tram. Many residents of the city were against the attitude of the city administration and the archdiocese of having approved the demolition; The term “crime against the history of Salvador” was used for this demolition. The tram stopped operating 20 years later. The artist Mário Cravo created the "fallen cross" (Cruz caída) on the site of the old cathedral as a reminder against forgetting one's own history. It was erected in 1999 and the decorations made of Portuguese stone from the colonial era disappeared under granite slabs. The sculpture Brunnen an der Markthalle (Fonte da Rampa do Mercado), where the original Mercado Modelo once stood, is by the same artist .

metro

The residents of Salvador refer to the newly built metro as a ruin. This is unfair, but the thought comes to mind when you consider that the groundbreaking ceremony was done in 1997, the wagons arrived in the port of Salvador in 2008, they were put on the rails in August 2010, but no forecast at all until March 2013 it was possible to determine when the first passengers would be transported. On March 8, 2013, the city administration handed over responsibility for the operation of the metro to the state. From now on, the railway system will also be organized at state level. Even more because with the Acesso Norte it practically ends in nowhere instead of driving from the center of Lapa directly to the urban center of Pirajá. In addition to the tram network that worked until the 1950s, the map shows the first five stations of the metro (Lapa to Acesso Norte), which could most likely be connected to the network if those responsible continue with the project. After the Acesso Norte, the connection looks mostly like this.

Line 1 with the Lapa to Piraja connection has now been in operation for several years. A second line runs from Acesso Norte to the airport and will be fully operational in the first quarter of 2018 with the last station, Estacione Aeroporto.

Especially at peak times, a bus trip that takes 30 minutes on a day with little traffic can take up to two hours. The number of buses is not the problem. There are too many private cars on the streets, causing traffic jams and hindering buses. In addition, the heavy buses are sluggish through the steep districts of São Caetano, Liberdade and São Marcos. Schoolchildren, students and workers meet in a confined space in a bus that barely moves. As a result, thousands of students protested in 2011 to commemorate twelve years of building the twelve kilometers with no demonstrable success.

The completion of the first twelve kilometers was planned for 2003, but was then delayed until 2012, when test drives with sandbags were made in the middle of the year. During one of these test drives, Mayor João Henrique, known not very promising:

“We don't have any trained specialists for a project of this complexity. The train driver who is driving the cars has come from the south. But we will train our specialists here. "

Bicycle paths and beach promenade

First visible changes in the cityscape since the inauguration of the new mayor ACM Neto . Since mid-September 2013, cyclists have been able to use bike stations modeled on other cities such as São Paulo and Recife . By registering on the Internet and paying by credit card, bicycles can be borrowed and returned to the appropriate stations. On Sundays and public holidays, a cycle path consisting of hundreds of warning cones is painstakingly built by hand. These are guarded from strategic points and thus protected against theft. This cycle path starts at Cathedral Square and stretches across the entire Avenida Sete de Setembro and ends after about five kilometers at the Barra lighthouse .

Since September 28, 2013, traffic between the Barra lighthouse and the Barra Center has been suspended in favor of the pedestrian-friendly beach promenade. In addition to intensive car traffic, 76 bus routes had to be diverted. After the end of construction, probably in May 2014, cars with a max. Speed of 20 km / h. For many years, residents and tourists have complained about the shabby section of the beach, where restaurants and tourists are regularly attacked and robbed. Numerous institutions have already given up this location because of its dangerousness. The city administration and tourism authority hope that the renovation will result in increased visitor numbers for the city.

Personalities

sons and daughters of the town

Connected to the city

- Jorge Amado , one of the most important Latin American authors of the 20th century, member of the language academy, lived and died in Salvador (1912–2001)

- Ernst Widmer (1927–1990), Swiss-Brazilian composer

Magazine articles

- The collapse of the city of Bahia . In: Illustrirte Zeitung . No. 25 . J. J. Weber, Leipzig December 16, 1843, p. 391-392 ( books.google.de ). .

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Cultural project - Baroque in Bahia

- Travel reports about Salvador

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Salvador - Panorama. In: cidades.ibge.gov.br. IBGE , accessed August 31, 2019 (Brazilian Portuguese).

- ↑ IBGE Censo 2010 ( Memento from June 20, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ wetterkontor.de

- ^ Índios em Salvador (identidade, memória e alteridade). (PDF; 242 kB) In: IV ENECULT - Encontro de Estudos Multidisciplinares em Cultura. 2008, accessed December 15, 2012 (Portuguese).

- ↑ http://www.caestamosnos.org/efemerides/148b.jpg

- ↑ http://www.fotografiaecultura.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/catharina_teto.jpg

- ↑ en: Caramuru in the English language Wikipedia

- ^ Diogo Alvares Correa, o Caramuru. In: Resumo de Luc Ramos. Retrieved January 29, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-9omM2_noRo0/T4wW56oz-hI/AAAAAAAAAy8/4YBDCNy5mBY/s1600/DSCF0439b.jpg

- ↑ Célebres fúnebres ou defuntos famosos? October 7, 2009, accessed January 29, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Celebração foi realizada na igreja da Graça, onde o corpo da esposa de Caramuru foi sepultado. In: Correio da Bahia. January 27, 1999, accessed January 29, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ^ Francisco Pereira Coutinho

- ↑ So Historia. In: Historia do Brasil. Retrieved January 29, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ A no less dramatic ending

- ↑ Ação educacional jesuítica no Brasil colonial. (PDF; 166 kB) In: Amanda Melissa Bariano de Oliveira. 2011, accessed January 29, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Pero Fernandes Sardinha in the Portuguese language Wikipedia.

- ↑ Thales de Azevedo: Povoamento da Cidade do Salvado. Publicação da Prefeitura Municipal do Salvador Comemorativa do IV Centenario da Cidade . Salvador 1949, ISBN 978-85-61458-16-4 , p. 109.

- ↑ RIGS / Aucimaia de Oliveira Tourinho, Nicholas Carvalho de Almeida Costa: As Fontes na Cidade de Salvador ( Memento from August 31, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (“Fresh water sources in Salvador”; PDF; 4.6 MB) from January / April 2012 , accessed December 26, 2014.

- ↑ A revolta dos Alfaiates. In: Brasil Escola. Retrieved February 5, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ A Conjuração Baiana. In: Mundo Educação. Retrieved February 5, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Conjuração Baiana. In: Info Escola. July 7, 2010, accessed February 5, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Conjuração Baiana. In: Historia Brasileira. December 18, 2009, accessed February 5, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ A revolta dos Alfaiates ou dos Búzios. História. In: Brasil Cultura. November 7, 2009, accessed February 5, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Santa Casa de Misericordia

- ↑ Conjuração baiana in the Portuguese-speaking Wikipedia.

- ↑ Jorge Hage: lei atual not manda rico para a cadeia. (No longer available online.) In: Terra Magazine. September 11, 2008, archived from the original on August 11, 2011 ; Retrieved February 5, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ http://salvadorhistoriacidadebaixa.blogspot.com.br/2012/11/meu-bairro-querido-cais-do-ouro.html

- ↑ http://www.ibahia.com/a/blogs/memoriasdabahia/files/2012/08/O-anuncio-do-gelo-em-Salvador.jpg

- ^ O dia em que os baianos conheceram o gelo. Então preconizado como remédio. In: Nelson Cadena. August 31, 2012, accessed February 2, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-vgC1g4JOkyQ/TXqMbxOCM6I/AAAAAAAADcE/5f0G-NlJCbo/s1600/Nova%2BImagem%2B%252841%2529.png

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento from December 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://farm5.staticflickr.com/4088/4952212579_9a1550c720_z.jpg

- ↑ http://historiasdopovonegro.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/camara-municipal.jpg

- ^ Histórias do povo negro. In: Agnes Mariano. Retrieved February 9, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-54W5yWdePq8/TzcUNh8rWOI/AAAAAAAAAnA/EV1W0ffbYBU/s1600/DSC06186a.jpg

- ^ Forte São Pedro

- ↑ http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_rZxtUb7v96Y/SwG6F4P7CKI/AAAAAAAAA9w/JB9m2gdTx1k/s1600/Nova+Imagem+%287%29.png

- ↑ A revolta dos malês. (PDF; 475 kB) (No longer available online.) In: João José Reis. 2002, formerly in the original ; Retrieved February 9, 2013 (Portuguese). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ http://de.slideshare.net/uranoandrade/processo-eduardo-carig

- ↑ Eduardo Barauna Carige (1851-1905): O Antonio Bento Baiano. (PDF; 273 kB) In: Ricardo Caires. July 2011, accessed February 4, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ^ Agenor Bandeira de Mello, Sílvio Batalha: Cartilha Histórica da Bahia, Salvador, 5th edition, 1990.

- ↑ Luís Henrique Dias Tavares : História da Bahia . EDUFBA / UNESP, Salvador / São Paulo, 10th edition, 3ª tiragem, 2006.

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from January 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8462/8071055693_88d0358169_z.jpg

- ↑ http://www.historia-brasil.com/imagens/bombardeio-salvador.jpg

- ↑ http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_rZxtUb7v96Y/SygFTpgXduI/AAAAAAAABgY/-ij6-lxjdpo/s320/Nova+Imagem+%2851%29.png

- ↑ http://www.bahia-turismo.com/imagens/igreja-barroquinha.jpg

- ^ Castro Alves Square

- ↑ http://secbahia.blogspot.com.br/2008_07_01_archive.html

- ^ António Martinho Baptista - O Pelourinho do Soajo. Terra de Val de Vez, Boletim Cultural, GEPA - Nº1, 1980.

- ↑ World: largest cities and towns and statistics of their population. (No longer available online.) In: World Gazetteer. 2012, archived from the original on May 11, 2013 ; accessed on February 24, 2013 .

- ^ Süddeutsche Zeitung: There is poverty in Salvador, the murder rate is high. January 25, 2014.

- ↑ YouTube: Welcome to murder capital of Brazil January 25, 2014 (English).

- ^ Mail Online: Children who carry guns through Salvador's slums. January 25, 2014 (English).

- ↑ As 16 cidades mais violentas do Brasil. ( Memento of February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) January 25, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Taxa de homicidios. January 25, 2014 (Portuguese).

- ↑ The statistics portal. , January 25, 2014.

- ↑ Salvador está entre as cidades mais violentas do mundo, port., January 26, 2014.

- ↑ Salvador é a 14ª cidade mais violenta do mundo. Lista leva em conta o número de homicídios por 100 mil habitantes. ( Memento from October 29, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: iBahia. January 26, 2016, accessed October 31, 2016 (Portuguese).

- ↑ G1 Bahia: Diarias de hotéis já variam 317%. January 25, 2014 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Principais ocorrências policiais ( Memento of February 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (Portuguese), January 25, 2014.

- ↑ 69% dos homicídios em Salvador estão ligados ao tráfico de drogas. January 25, 2014 (Portuguese).

- ↑ 2-year-old boy fatally hit in IAPI (Salvador). January 25, 2014 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Crianças são mortas em guerra entre facções em Salvador, February 15, 2014 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Adolescente morre e duas pessoas ficam feridas em tiroteio na avenida Ogunjá

- ↑ iyá Nasso ( Memento of 9 May 2013 Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://www.flickr.com/photos/mcorreiacampos/4609087088/lightbox/

- ↑ http://www.bahia-turismo.com/salvador/igrejas/igreja-barroquinha.htm

- ^ Grandes reportagens do Correio da Bahia. Publicação do Jornal Correio da Bahia - Etnias diferentes partilham crenças . Salvador, October 6, 2002, p. 53.

- ↑ http://www.zeno.org/Heiligenlexikon-1858/A/Iphigenia,+S .

- ↑ Seven dead in a stadium accident in Brazil. In: Hamburger Morgenpost. November 26, 2007, accessed February 8, 2013 .

- ↑ https://prezi.com/m/ltvtnjgfwuso/casa-do-comercio/

- ↑ Álvaro Pinto de Carvalho Jr .: O Barão de Jeremoabo ea Política de seu Tempo . Salvador: SECT, 2006. ISBN 85-7505-147-4 .

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento from January 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ photo

- ^ Correio da Bahia: Grandes reportagens do Correio da Bahia. Publicação do Jornal Correio da Bahia - Trilhos da saudade, Salvador, October 6, 2002, p. 32 ff.

- ↑ http://www.tramz.com/br/sv/sv02.html

- ↑ http://www.tramz.com/br/sv/sv19.html

- ↑ http://www.tramz.com/br/sv/sv18.html

- ^ The Tramways of Salvador Bahia state Brazil BY Allen Morrison. In: ORF . 1999, accessed January 30, 2013 .

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento from January 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Correio da Bahia: Grandes reportagens do Correio da Bahia. Publicação do Jornal Correio da Bahia - Trilhos da saudade, Salvador, October 6, 2002, p. 44.

- ↑ http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-Piu7_IRG4XY/UDQfxyo6taI/AAAAAAAAATY/xum8ueWSPZ8/s1600/plano+inclinado+gon%C3%A7alves.jpg

- ↑ http://cdn-locations-images.tripomatic.com/img-poi29164-ogjvVj-m.jpg

- ^ Sé (Salvador) in the Portuguese language Wikipedia. A Cruz caida de Mário Cravo ( Memento of January 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://mw2.google.com/mw-panoramio/photos/medium/36615904.jpg

- ↑ http://observarte.zip.net/images/old-mercado-modelo.jpg

- ↑ http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-Qt5iCOcl3LY/Tk2xoxiMg0I/AAAAAAAAARc/d-Dy1dbSwng/s1600/2011_03_2315_06_3081090metro.jpg

- ↑ Metrô realiza viagem teste até a Estação Aeroporto. CCR Metro Bahia, December 21, 2017; accessed February 23, 2018 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Estudantes marcam ato para protestar contra falta de metrô em Salvador. In: ORF . August 11, 2011, accessed January 31, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Metrô de Salvador testa viagem pela 1 ° vez após 12 anos em construção. In: G1. December 22, 2011, accessed January 31, 2013 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Archived copy ( memento of October 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive )