Worms-Horchheim

|

Horchheim

City of Worms

|

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 49 ° 36 ′ 37 ″ N , 8 ° 19 ′ 4 ″ E | |

| Height : | 102 (98-116) m |

| Residents : | 4712 (December 31, 2018) |

| Incorporation : | April 1, 1942 |

| Postal code : | 67551 |

| Area code : | 06241 |

|

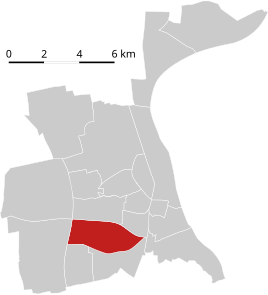

Location of Horchheim in Worms

|

|

Horchheim [pronunciation ˈhɔʁçˌhaim , in the dialect ˈhɔiʃəm or moderate ˈhɔʁʃəm ] is a village in the Rheinhessen Eisbach valley . Incorporated to Worms in 1942 , the district connects to the south-west of the outer city center.

geography

overview

Horchheim is located on the north side of the Eisbach valley, shortly before the valley ends and the brook emerges from the Rheinhessen hill country onto the lower terrace of the Rhine plain. The foothills of the hill country between Eisbachtal in the south and Pfrim valley in the north is called "Hohensülzener Riedel". The Riedel is a hill that gradually descends towards the Rhine , is covered with loess and loess loam and is very fertile. At the edges of the Riedel and in the Eisbach lowlands one can find less productive sand and gravel soils. The place extends about 1800 meters on the southern slope of the Riedel, which rises only about ten to 15 meters above the valley floor.

Above the village, on the edge of the Riedel, the "Eisenberger Straße", a branch of the important long-distance route from the Rhine to Gaul , ran in pre-Roman times . This old long-distance connection from Worms via Kaiserslautern to Metz had a branch in the Worms area that went through the Eisbach valley via Eisenberg to Kaiserslautern. The path through the Eisbachtal on Eisenberger Straße only lost its importance in the course of the Middle Ages or at the beginning of the modern era. The main traffic axis of the place is today the L 395, which coming from the northeast of Worms crosses Horchheim as "Wormser Straße", "Untere Hauptstraße" and "Obere Hauptstraße" and leads from the western end of the village to Worms-Heppenheim . The inhabitants call the upper village the western part of the village on the upper main street, which is slightly higher than the lower part of the lower main street. The townscape is dominated by three churches, namely the old Catholic church, which is now used as a cemetery chapel , and the Protestant Gustav Adolf Church , which tower over the upper village, and the Catholic Holy Cross Church on the Goldberg above the center of the village, which can be seen from afar . In addition to Oberdorf and Unterdorf, the residential areas adjacent to the east, Nikolaus-Ehlen-Siedlung and Zollhaussiedlung, are now administratively part of the Horchheim district, although they are not in Horchheim, but in Worms.

Settlement geography

Place form

Horchheim is a street village . The main axis of the place is the main road running halfway up the slope above the brook valley, on which the court riders are lined up on both sides in close succession. This created the elongated outline of the living space . The village is located on the gently sloping Riedel slope on the border between the dry arable land and the damp brook valley. The narrow border between dry and moist ecotope on half the slope is a particularly favored settlement area, which has a moderate climate, is flood-proof and at the same time offers easy access to the water. In addition, the central location ensures short distances on the one hand to the fields and on the other hand to the gardens and night pastures in the meadow. On the oldest map of Horchheim from 1710, there were only a few properties in the side streets. At the western end of the village, Dorfstrasse turned off in front of Fronberg and led through "Hohl" ("Wilhelm-Röpcke-Strasse") up to "Eisenberger Strasse". The breakthrough on the Fronberg, which the main road uses today, was only created in 1838/39. Since the 18th century, the development has moved further and further along the main street towards the city of Worms. Since the 19th century, first the cross streets and then the streets parallel to the main street were gradually built with houses. As a result, the local form develops in the direction of a clustered village with a main street running through it. Due to the influx of resettlers from the middle of the 20th century, two non-linear, closed districts emerged at the eastern end of the village with the Nikolaus-Ehlen-Siedlung and the Zollhaus-Siedlung, which pushed the development into a cluster village further.

Corridor shape

The agriculturally used area ("corridor") of the Horchheim district lies mainly north of the village. It is a sheltered hallway , i. H. the corridor consists of a number of tubs and each tub of strip-shaped, parallel parcels with different owners. The mixed property is no longer consistently reflected in the different planting of neighboring plots. The few still active farmers today grasp parcels of land from different owners through operational cooperation and exchange of use, e.g. B. by means of sub-lease, together to form larger fields. Most of the corridor, which lies on the Riedel plateau, is fairly evenly divided into block-shaped troughs 350-500 m long and 160-190 m wide, each of which is parceled out transversely into strip-shaped parcels extending from south to north. On the Riedel slope, in the immediate vicinity of the village and at the municipal boundaries in the west and east, the tubs are cut unevenly due to the slope and the boundaries of the corridor and parceled out in alternating directions. On the oldest district map from 1710, the Krummgewann was still a huge, transversely parceled broad strip, which may indicate an earlier ownership unit, e.g. B. points out as Herrenland. In 1710, the western border of the district was taken up by two elongated parcels of land, bounded in the south by the "Anthaupten", which means "plow turning point". These are apparently traces of a long strip complex with a field length of more than 1000 m. Also the tubs "Im Mondschein", "Untere Langgewann" and "Obere Langgewann" could formerly have belonged to a coherent long stripe association. In the area around Worms there are remnants of earlier long strip complexes in other districts, including a. in Weinsheim , Wiesoppenheim , Heppenheim , Pfeddersheim and Pfiffligheim . There is the thesis that the long strips are traces of a planned land division of the imperial estate from the early Middle Ages. Although an essential basis of this theory, namely the notion that there was a state of "royalty free", hardly finds approval today, the assumption is still plausible that the relics of long strip corridors in the Worms area relate to the early medieval structures of large manors, especially the imperial estate , are due.

House shapes

The townscape in the old village center on the upper and lower main roads is determined by small and medium-sized agricultural properties of the small farm type . It is mainly about two-sided courtyards and hook courtyards . In between are some three-sided courtyards . The transverse residential buildings are mostly facing the street without the gable and the courtyard entrance is often closed by a high courtyard gate with a roof. This creates the street scene of the "half-open gable row". The transverse barn forms the rear end of the homestead. Most farms have been shut down in the past few decades. The street scene changes in the center of the village. Many of the buildings here have their eaves facing the street. On the one hand, there are special buildings with no previous agricultural history, namely former community and school buildings and the old post office, and on the other hand, former craftsmen's houses and a former inn. The local expansions in the 19th century are characterized by small farms and workers' houses. There are only a small number of buildings from the 18th century left in the village; most of the houses date from the 19th and 20th centuries. Facades made of red and yellow bricks are characteristic of the buildings of the 19th century. In the 20th century, construction was preferred on the side streets and in the two settlements; The plots open to the street are typical of the modern properties. The oldest view of the town from 1710 shows the structural condition a few years after the destruction of the Palatinate War of Succession . The rectory was the only two-story building at that time. In the vicinity of the upper mill there were two larger farms, a three-sided farm and a hook farm. Otherwise certain smallholder Einfirsthöfe and small houses the image. Separate stables or barns were rarely found. In some houses the thatched roofs were decorated with gable posts .

geology

Horchheim is located in the northern Upper Rhine Graben on the intermediate clod between the western edge clod of the trench and the actual grave clod. The fault that separates the edge floe and the intermediate floe is identical to the so-called "western Rheingraben main fault" at the level of Worms, which moves from Oppenheim in a south-south-west direction via Guntersblum , Bechtheim , Worms-Pfeddersheim , Dirmstein , Freinsheim to Bad Dürkheim . The jump height of the fault at Dirmstein is about 500 meters, i. H. the base of the tertiary layers is around 500 m deeper at the intermediate floe than on the edge floe. The places Pfeddersheim, Heppenheim and Dirmstein are on the intermediate floe , while Monsheim and Offstein are already on the marginal floe. The eastern border of the intermediate floe runs from Osthofen via Worms-Herrnsheim to the city center of Worms and from there via the Weinsheimer Zollhaus , Kleinniedesheim , Heßheim to Lambsheim . The height of this fault at the Weinsheim customs house is approx. 35 meters (upper edge of the Pliocene ).

| Geological structure up to the Pliocene in the Horchheim-Weinsheim-Wiesoppenheim area | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leading horizons according to Schneider u. cutter | Wiesoppenheim (intermediate clod) | Weinsheim (intermediate clod) | ||||

| system | series | Leading horizon | Temporal allocation | Age (thousand years ago) | Top edge | Top edge |

| quaternary | Pleistocene | Leithorizont 9 (tone series) | Eem interglacial | 126-115 | 91 m above sea level | is missing |

| Leithorizont 7 (tone series) | Holstein interglacial | approx. 340-325 | 75 m above sea level | 76 m above sea level | ||

| Leading horizon 5 (tone series) | Cromer interglacial | approx. 850-475 | 41 m above sea level | 52 m above sea level | ||

| Leading horizon 3 (tone series) | Tegelen interglacial | approx. 2000-1600 | 22 m above sea level | is missing | ||

| Tertiary | Pliocene | Leading horizon 1 (tone series) | no assignment | until approx. 2600 | 5 m above sea level | 12 m above sea level |

The tertiary layers in the Horchheim area have not been explored by drilling. In 1988, a seismic reflection depth profile DEKORP 9N was recorded for the intermediate floe, which extends in an east-west direction from the Odenwald to the Saar-Nahe basin and crosses the Oberrheingraben and Rheinhessen . The DEKORP-9N profile runs at the level of Herrnsheim through the intermediate clod and shows u. a. is the depth of the tertiary base and several tertiary layers in TWT seconds.

Floors

The Horchheim district consists of the Riedel plateau in the north, the Eisbach valley in the south and the Riedel slope between the plateau and the brook valley. On the Pleistocene loess sediments of the Riedel surface, extensive areas of black earth soils (Tschernoseme) developed in the Holocene . In between there are a few small pieces of colluvium from loess, from Pararendzina from loess and from Regosol from Pleistocene-deposited terrace sand. In the Kreuzgewann and on the Riedel slope there are areas of parabraunerde made of eroded drifting sand. Most of the Riedel slope is covered with loess colluvium. On the western edge of the village there is a small zone of holocene sand colluvium. The lowland is covered with Auengley and brown floodplain . The black earth soils are extremely fertile. The Pararendzina and Kolluvium soils that emerged from loess are also quite fertile, as are the floodplain soils of the brook valley. The Parabraunerde has only a medium productivity and is used almost exclusively for vineyards. The Regosol soils are not very fertile, but only cover small areas. All in all, the Horchheim district is very fertile and, due to the high proportion of black earth, is one of the most productive growing areas in Germany. This is also the reason for the early dense settlement of the area. As in other old settlements , the protection of valuable arable soils from degradation z. B. by surface sealing , a special meaning.

history

overview

The oldest archaeological finds in the district come from the Neolithic (New Stone Age). Some remains have also been found from the Bronze Age , La Tène Period and the Roman era . Horchheim is mentioned for the first time in 766 on the occasion of a donation to the Lorsch Monastery in a document from the Lorsch Codex . In the Franconian period there was a royal estate in Horchheim and the neighboring towns of Wiesoppenheim and Weinsheim , which belonged to the imperial estate district (fiscus) Worms. The known parts of this imperial property came into the possession of the bishopric of Worms through royal donations until the end of the Carolingian era . Donation deeds from Emperor Arnulf dated June 8th and August 7th, 897 are known. The bailiffs of the bishopric were gradually able to take control of many of the bishopric's possessions. So the so-called Worms Rhine villages, including Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim, came to the Counts of Saarbrücken , who were high bailiffs of the Worms church in the 12th century. Through an inheritance distribution around 1180/1190, the Rhine villages came to the Counts of Zweibrücken , who later linked this property with the Stauf rule (near Kirchheimbolanden ), which they had acquired from the Counts of Eberstein .

In 1378 the last Zweibrücker, Count Eberhard, sold half of the Stauf estate to Count Heinrich II. Von Sponheim-Dannenfels and in 1388 also the other half. After the death of Count Heinrich II, the rule of Stauf was inherited in 1393 by the Counts of Nassau- Saarbrücken. After the Nassau-Saarbrücken line died out in 1574 , Nassau-Weilburg inherited the Stauf rule with the Rhine villages. The Counts of Saarbrücken and their successors only owned the Rhine villages as a fiefdom of the Worms Monastery. A condominium from Nassau and Hochstift over the Rhine villages has been documented since 1427 . This condominium existed until 1706, when the splintered rulership rights were cleared up in an area swap between Nassau-Weilburg, the Electoral Palatinate and the Hochstift Worms . Since 1706 the Hochstift Worms had unrestricted rule over the villages of Bobenheim , Roxheim , Mörsch , Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim . The part of the bishopric of Worms on the left bank of the Rhine had been under French occupation since 1797/98. Horchheim belonged to the Donnersberg department (Département du Mont-Tonnerre) during French rule , to the Grand Duchy of Hesse after 1815 and to the People's State of Hesse from 1918 to 1945 . Horchheim was incorporated into the city of Worms in 1942 .

prehistory

There were very few finds in the Horchheim area from the prehistoric epochs of the Stone Age , Bronze Age and Iron Age . The oldest finds were two bell beakers from the last phase of the Neolithic ( end Neolithic around 2200 BC). The bell-cup people were farmers. After that there was a huge gap until the Late Bronze Age ( urn field culture around 1350–800 BC), from which a bronze sword was found, allegedly in a grave between Horchheim and Pfeddersheim. Some graves from the La Tène period (450–30 BC) have been found.

Roman times

More finds came to light from Roman times. Roman coins from the late 1st century to the end of the 4th century have been found. A coin of Elagabal (218–222 AD) was found near the church (ie today's cemetery church) and several Roman gold coins from the 4th to 6th centuries were found in a field by this church, the last of Justinian (527–565 AD), probably a coin treasure. A late Roman grave with a wooden coffin was also found near the cemetery church. In 1932 a Roman cremation grave with two urns, two jugs and a bronze bell was discovered in Untere Hauptstrasse 77 . In 1887 the remains of a Roman estate (“ villa rustica ”) were found in the “Auf der Platt” area near the Roman road (so-called Eisenberger Strasse) . In 1966 a Roman cremation was found in the upper village in the “In den Kesselwiesen” district. In a stone column drum there was a glass urn with a handle and other gifts. A Roman god stone was also found in Horchheim. Finally, in 1976, three Roman pointed trenches were found, which formed the southeast corner of a right-angled complex. On the east side of the facility, two trenches were uncovered five meters apart. It may be the remains of a march or training camp. Presumably the area of Horchheim was inhabited during the entire Roman period. It was not a village, however, but a few far apart farms that must have been located on the southern slope of the Riedel , ie north of the Eisbach and near the Roman road.

Migration of peoples and the Frankish period

For the history of Rheinhessen in the 5th century, the tradition is extremely sparse. It is very difficult to get a reasonably consistent picture from the incomplete sources of how Roman rule and settlement in the areas on the left bank of the Rhine dissolved and how the Germanic migrations and settlements took place. Since the great Germanic invasion of 406/407 AD, the Roman military rule in the province of Germania was greatly weakened. The Roman civilization also continued in Rheinhessen into the second half of the 5th century. At first the tribe of the Burgundians seems to have settled on the Rhine in the area of Worms. The Burgundians probably moved on to the Rhône after 436/437. From 455 AD to around 476 AD, the Roman rule and economic structures gradually collapsed. Older researchers were convinced that from 455 AD there was an Alemannic conquest in Alsace, the Palatinate and southern Rheinhessen. In recent research, the Alemannic settlement in the Palatinate and in southern Rheinhessen is questioned in terms of intensity and extent. Confrontations between Franconia and Alamanni, especially in the years around 500, led to an expansion of Franconian influence on the Upper Rhine. At least since then, Rheinhessen was ruled by the Franks.

In the first decades of the 6th century, the intensive settlement of Rheinhessen by Franconian tribal groups began. This can be seen above all at the beginning of the occupancy of the Merovingian row grave cemeteries. The first Franconian settlements were single farms or small farm groups. In the course of the 7th century, additional settlements were created (so-called “early Franconian expansion”). The sources for the Franconian settlement of Horchheim are very poor: there are individual grave finds from the 7th century for the Merovingian period (middle of the 5th century to 751 AD) and for the Carolingian period (751 to 911 AD). only a few taciturn written sources from the 8th and 9th centuries. Archaeological finds and written records cannot therefore be directly related. It cannot be determined when Franconian settlers settled in Horchheim. It is certain that today's village Horchheim goes back to a Franconian settlement.

Horchheim did not emerge from Roman or older roots. There were probably at least two settlements on today's site in Horchheim during the Frankish period. A settlement was probably near the Franconian graves that were uncovered in 1910 and 1950 on Höhlchenstrasse. The grave finds on Hölchenstraße begin with SD phase 8 di approx. 600–620 AD. It is possible that Horchheim was not settled in the 6th century, like Wiesoppenheim, but only in the expansion phase. The settlement on Höhlchenstrasse was abandoned at an unknown point in time. Grünewald and Koch ( following Koehl ) suspect another settlement core in the area of today's market square. Koehl suspected a Frankish burial ground above the center of the village on Goldberg. To the north of the town, in an open field, “... a skeleton with a 'saber' was once found ...” There, Koehl searched for the cemetery without success. A note from 1910 also states that “In the western part of Horchheim on the height next to the path that leads to Pfeddersheim ... years ago a Frank. Grave to day ... “came. The settlers in Rheinhessen normally set up their farmsteads halfway up the slope between cattle pastures in the damp brook lowlands and the higher-lying farmland. At first, livestock farming was even more important than agriculture, but this soon gained in importance in the fertile land. The burial site was usually located a little above the settlement on the slope. The exact location of the first settlement cannot be deduced from later circumstances. The location of the medieval parish church (on the site of today's cemetery church) cannot be used to determine the location of the Merovingian founding courtyard. The location of the watermill mentioned in 766 cannot be determined. Even if the location of the mill were known, it would not be possible to infer the location of the settlement. Mills were often isolated and at a greater distance from settlements.

The first Franconian settlement Horchheim probably consisted of only one or a very small number of farms with only a few residents. The houses were not built of stone as in Roman times, but of wood. The buildings were therefore rebuilt when the wood had rotted. It was customary to relocate settlements. Since the 7th century, a significant increase in population can also be assumed for our area, which is accompanied by expansion and the establishment of new settlements. In the course of time there has been a tendency for individual farmsteads and small settlements to move closer together into larger units. Churches have been built since the 8th century, often in the cemetery above the settlement. The fixed location of the churches made a significant contribution to the fact that the settlements became permanent. Nothing is known about the landlords in Horchheim during the Merovingian era. It is believed that the Franconian conquest in Rheinhessen was initiated and directed by the Merovingian kings. The settler groups were presumably led by noble followers of the king. Even in the early days, the property was not grouped into large complexes. Instead, there was a coexistence of different landlords even in individual settlements and also a regular change of properties between king, nobility and church. The first written reports about Horchheim come from the Carolingian era. The place is mentioned for the first time in a deed of donation for the Lorsch monastery from the year 766. In this deed we hear from two landowners in Horchheim named Nither and Madelgis. Nither donates a riding court (mansus) with a mill on the Eisbach and a meadow that he bought from Madelgis to the Lorsch monastery. The next document for Horchheim dates from 834. Emperor Ludwig the Pious gives his loyal Adalbert goods in Horchheim, namely a Fronhof (mansus dominicatus) and five associated farms ( Hufen ), which Adalbert had previously owned as fiefs . It is well established that here Graf Adalbert of Metz from the powerful clan of hattonids is meant 841 as commander Emperor Lothair I. fell in the battle of the Wörnitz.

The royal estates of the Reichsgutbezirks (fiscus) Worms were recorded in the so-called Lorsch Reichsurbar from approx. 830–850. The main courtyard of the Fiscus was the royal court in Worms, to which side courtyards in Mörstadt and Wiesoppenheim were subordinate at that time. The side yard in Wiesoppenheim was rather small with 31 days of Salland's work and 30 loads of hay. In Horchheim, too, there was originally a side courtyard, but at that time it had already been lent or given away to Count Adalbert. We don't know the size of the Horchheim Fronhof. The Reichsurbar counts to the Fiscus Worms a total of 242 daily work (iurnales) Salland and 580 loads (carradae) hay from meadows and 30 loads of wine from vineyards in self-management through the main courtyard and the side courtyards. In addition, the Fiscus Worms belonged to the Fiscus Worms as a land of interest, namely, 40 free hooves (Ingenualhufen, mansi) and 24 Hörigenhufen (Servilhufen, sortes). In addition, 15 mills appear to have been subject to tax. A significant part of the Zinsland was in Wiesoppenheim, Horchheim and Weinsheim. This emerges from two documents from Emperor Arnulf from 897, in which the emperor gave away 27 hooves in Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim as well as other imperial goods in the three places that had been given to the royal court cleric Willolf to the bishop's church in Worms . In the Lorsch Reichsurbar, a hoof was between 17 and 24 days of work. A day's work would have been 0.3 to 0.5 hectares. The age of the Worms Königsgut complex is not known; It can be assumed, however, that at the latest since Charlemagne's accession to power, there had been extensive fiscal holdings in the area around Worms. From 770 to 791, the Palatinate in Worms was Charlemagne's most frequent and important residence. Even after the fire in the Palatinate in 791, the king kept the Worms estate together. It was only under Ludwig the Pious that goods from the Worms Fiscus began to be awarded, and in 897 Emperor Arnulf gave the remaining possessions to the diocese of Worms. Under Emperor Arnulf and King Ludwig the Child , Bishop Thietlach von Worms (before 891–914) was entrusted with the representation of royal interests and the administration of royal estates. The Worms Wall Building Regulations, which is also assigned to Bishop Thietlach and which was probably created around 900 due to the risk of Norman attacks, stipulated, among other things, that the residents of the towns on the Eisbach as far as Mertesheim should take care of the maintenance of a section of the Worms city wall.

High and late Middle Ages

In 940 the Fulda monastery left a certain Emicho, vassal of Count Konrad, goods in Horchheim for life, namely five hooves with accessories, five servants (mancipia) and 56 yokes (iugera) Salland for an annual payment of one pound and in exchange against a hoof in Alsheim Presumably we see again parts of the royal fron yard mentioned in 834 with its five hooves. It seems as if this part of the Horchheim Reichsgut was given away to Fulda. Fulda also owned Weinsheim . The Fulda monastery did not keep its possessions in Horchheim and Weinsheim. The churches of St. Cross and St. Bonifatius, which are believed to belong to these estates, came to the Bishopric of Worms; the property must have taken the same route. This was a normal process, because the Fulda monastery and the diocese of Worms endeavored when establishing their sovereignty to establish a spatially cohesive territory in the vicinity of the respective ruling center. Litter and remote holdings were of less importance and were often lost or exchanged or sold.

In the high Middle Ages, there was a significant structural change in rural settlements against the background of population growth, land expansion, upswing in markets, trade and monetary systems and technical improvements. The older manorial rule, which was characterized by spacious, centrally managed villications, was replaced by the pension manorial system: the goods were now given out as fiefs or leased, the ties between the hooves and the Fronhof were loosened and the compulsory labor was replaced by taxes. In Rheinhessen this change began in isolated cases as early as the 11th century and was well advanced by the 13th century. In Horchheim, the clerical landlord's own management of the Fronhof was probably replaced by a lease of the Fronhof in the 13th century at the latest. In a document from the year 1261 a "Dierich von Horchheim called Im Hof" appears, which is probably identical with the Diderich mentioned in 1272 as mayor in Horchheim and Wiesoppenheim. We are probably looking at the self-employed tenant of the Fronhof, who at the same time served the rulers as mayor. And in 1496 a “Veltin ime Hoff ... ime gemeyne (n) gude” was recorded in the tax register of the common penny, to which six maidservants belonged as servants. The "common good" probably refers to the former Fronhof.

The loss of importance of the manor farms made possible "a village-related life and economy" and the emergence of the actual village community. In Horchheim, the village community ("universitas") first appeared in a document in 1353.

Surname

As Old High German form of the name suspected Ramge "daz horaga home," which roughly means "the swampy home". The place name therefore does not go back to the personal name of a founder, but refers to the marshy Eisbach lowland. There are a large number of place names from the early Middle Ages, which are formed with names for bog or swamp, in the Worms area z. B. also Hohen-Sülzen and Mörstadt. In those days there was much more wet and swampy terrain than there is now. This marshland may have been fascinating or even frightening to the people of the time. A particularly humid zone is likely to have been the area around the Kämmererwiese and the area from there towards Wiesoppenheim. The field names "Bieberling", "im Bruchweg" and "Entensee" are reminiscent of beavers that were formerly native to the area, of swamps and one or two lakes.

population

Until the middle of the 19th century, the residents of Horchheim lived mainly from agriculture. The agricultural employment opportunities were limited by the small size of the district, the ownership structure and the sales opportunities for agricultural products. Several times since the 14th century epidemics and wars led to a significant decline in the number of inhabitants, the last time at the end of the 17th century in the Palatinate War of Succession . The population grew slowly in the 18th century. The Worms area was not able to catch up with industrial development until the middle of the 19th century due to poor transport links and constricting customs barriers. From the middle of the 19th century, large factories were set up in Worms, especially for the leather industry. From this time on, the population of Horchheim grew strongly. The place developed from a farming village to a place of residence for externally employed workers and employees. With the construction of the Nikolaus-Ehlen-Siedlung (since 1950) and the Zollhaus-Siedlung (since 1964) Horchheim was able to increase its population considerably and now has over 4,500 inhabitants.

|

|

|

(Sources below)

(Sources below)

Religions

Catholic parish

The first churches for the rural population were own churches of the landlords , e.g. B. of the king, of nobles or churches of monasteries and dioceses. In the Diocese of Worms, such own churches have been attested since the 8th century. However, it is certain that as early as the 7th century, on the initiative of the bishops, the flat land began to be covered with a network of lower churches. The local bishops were mostly not the rulers of their own church; many lower churches were in the hands of monasteries and nobles or belonged to the imperial estate. Not all rural churches became parish churches with baptism and burial rights. After Charlemagne prescribed tithing as an annual fee to the relevant parish church, it became common around the year 800 to define fixed parish districts for the parish churches. The parish church of St. Martin in Wiesoppenheim goes back to a royal own church that already existed in the 8th century. Presumably, the Martins Church was initially responsible for the entire association of people who belonged to the Reichsgut in the Eisbach towns of Wiesoppenheim, Horchheim and Weinsheim. The churches of St. Bonifatius in Weinsheim and Heilig-Kreuz in Horchheim probably go back to the own churches of the Fulda monastery . St. Bonifatius is the pertinence patronage for Fulda churches and clearly points to the Fulda Abbey. The Holy Cross Patronage should also be assigned to Fulda. Since the beginning of the 9th century, Fulda was allowed to collect tithes on its property for its own churches due to special privileges, even if the property was in the parish of a foreign parish church. The tithe rights were so profitable for the monastery that they built their own churches even on smaller estates. From the 11th century onwards, the bishops were increasingly taking action against the Julien tithe privileges and were able to wrest many tithe rights from the monastery. The churches in Horchheim and Weinsheim were transferred from Fulda to the Worms Monastery in the High Middle Ages. The separation of the parish Horchheim-Weinsheim from the old parish Wiesoppenheim must have taken place at the latest when ownership is transferred to the bishopric. A pastor from Horchheim is mentioned for the first time in 1234. Weinsheim was probably never an independent parish. In the Worms Synodal of 1496, Weinsheim is, as it has been since then, a branch of Horchheim. The Worms cathedral chapter had patronage over the parish of Horchheim . The parish belonged to the Deanery Dirmsteim in the Archdeaconate of the Dompropst. The Wiesoppenheim parish was impoverished in 1496, perhaps also a consequence of the separation of Horchheim and Weinsheim. The Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche in Horchheim surely stood on the site of today's cemetery church in the Fulda time. Because of the usual spatial proximity of the Fronhof and the church, the royal Fronhof, which later fell to Fulda, can also be located in the upper village. The first Holy Cross Church must have been a small wooden church without a tower. In the 11th century at the earliest, a simple stone church with a tower was built instead of the wooden church . The cemetery lay in their shadow . As can be seen on the local view of the geometer Pabst from 1710, the church had a 5/8 choir in the west. Wested village churches were still very rare at the beginning of the 18th century. A connection with the Carolingian tradition of the Fulda Monastery to build western churches can probably be ruled out. Probably the Horchheimer Church in the Middle Ages faces east . The enlarged nave with west choir was probably not built until the middle of the 16th century, when the east facing of the church building had lost its importance after the Council of Trento . The reason for the reorientation to the west was probably the insufficient space next to the old tower for the construction of a large east choir. The church was dilapidated in the 18th century and became too small for the larger community. Therefore, the west choir and nave were demolished in 1724–1726 and replaced by a spacious, unadorned hall church with an east-facing choir. The steeple of the old church was retained. In 1801 the deaneries of the Worms diocese on the left bank of the Rhine came to a short-lived French diocese of Mainz and finally in 1814/1821 to the new diocese of Mainz . In 1835 the cemetery was moved up to the open field. At the end of the 19th century the church was again too narrow due to the steady population growth and also in need of renovation. In the years 1908–1910 a spacious neo-Gothic church was built on the Goldberg. The old church was later converted into a cemetery church. Wiesoppenheim became a branch of the parish Horchheim in the 17th century, but has been independent again since 1927. The two parishes of Horchheim-Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim have had a common pastor since 1982.

Evangelical parish

At the beginning of the 19th century there were only a few inhabitants of Protestant denomination in Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim . Since 1824 they had been assigned to the parish of Heppenheim ad Wiese . Since the middle of the 19th century, the number of Protestants in the three towns increased sharply, mainly due to the influx of workers from Worms companies. In 1873 a Protestant religious community for Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim was formed in Horchheim, which was initially a branch of Heppenheim ad W., but in 1874 it joined the evangelical parish of Worms, which is closer to home. The services took place in a prayer room in the Horchheimer Obermühle until 1875, then in Schwender's inn and in the Weinsheim customs house. These makeshift arrangements ended in 1878 with the acquisition and conversion of the former Horchheim synagogue into a Protestant prayer house. When the Worms parish was divided up in 1892, the Horchheim branch became part of the Andreas community. As the number of parishioners in the branch grew steadily, it was soon no longer possible to take care of the parish from Worms. In 1898 Horchheim was therefore raised to an independent parish, and Weinsheim to a branch parish of Horchheim. The prayer house became too narrow for the growing congregation in the 1890s. After lengthy preparations, the congregation began building the Gustav Adolf Church in Horchheim in 1907, which was inaugurated in 1908. In 1948 the parish of Horchheim became a member of the Protestant community of Worms.

Jewish community

A small Jewish community had existed in Horchheim since the 18th century. In 1815 a synagogue was mentioned. A synagogue was built at 33 Oberen Hauptstrasse from 1845 to 1847. In the decades that followed, almost all Jews left Horchheim. The Jewish community dissolved in 1873. The synagogue was later acquired by the evangelical community and converted into a prayer house.

Politics and administration

Local advisory board

A local district was formed for the Worms-Horchheim district . The local council consists of eleven members, the chair of the local council is chaired by the directly elected mayor .

For the local council see the results of the local elections in Worms .

Community leader

A mayor for Horchheim is mentioned for the first time in the 13th century. The mayor was a head of the village community appointed by the rulers. For the older time only a few names of mayors have been identified. It was not until the middle of the 18th century that there was an almost complete series of officials. After the French Revolution, the community leaders were no longer called Schultheiss, but from 1798 "Agent Municipal" and from 1800 "Maire". The mayor was appointed by the prefect of the department. The Hessian municipal code of 1821 created the mayor for whom candidates were initially chosen, from which the Hessian government then selected the mayor. Later the mayor could be directly elected. Since the incorporation in 1942, Horchheim no longer has a mayor, but a mayor.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the local elections on May 26, 2019 , Volker Janson was confirmed in office with 62.1% of the vote.

Municipal coat of arms

Blazon : In a black field two crossed silver keys with a downward facing beard, raised by a golden cross .

It is unclear when the municipality adopted this coat of arms . Village coats of arms did not appear in Germany until the end of the 19th century and became generally in use from the 1920s. The figures and their arrangement are taken from the oldest Horchheim court seal (proven from 1470); in the seal, however, it is still a passion cross , not a common cross . The colors black, silver and gold are borrowed from the coat of arms of the bishopric of Worms .

The keys are the attribute of St. Peter ( Key Petri ) and obviously stand for the Worms cathedral chapter , which was the church patron of the Horchheim parish church. The cross probably refers to the church patronage "Holy Cross".

Administration of justice

A wisdom from 1489 reports that the court for a high court was in Horchheim, which was responsible for Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim. Three times a year there was an unsolicited (real) thing on the Tuesday after the eighteenth (January 13th), after Georgi (April 23rd) and after Natal Joannis (June 24th or maybe August 29th). This dish may go back to a count court of the Frankish times. Based on the immunity of the Worms Church, the bishopric and its bailiffs gained high jurisdiction in the course of territorialization . There is evidence of a gallows in Horchheim since 1374. In the 18th century there was still an executioner in Horchheim. In addition to the high court, there was a village court in Horchheim. Both courts may have met in the same place; In 1353 a session of the village court "an deme angel" is mentioned. The Horchheim courts were abolished in 1798.

Culture and sights

Art and cultural monuments

The Protestant and Catholic parish churches are artistically significant.

The Protestant Gustav Adolf Church and the directly adjoining rectory are elevated on a walled terrace, to which two flights of stairs lead. The church and rectory were built in 1907/08 in neo-baroque and art nouveau shapes and form an impressive ensemble. The church is a North-oriented hall building with a towering above the gabled facade roof skylights -Turm. The Art Nouveau painting of the choir is by the Worms painter Fritz Muth (1865–1943).

The Catholic Holy Cross Church was built in 1908/1910 as a neo-Gothic basilica high above the village on the Goldberg according to plans by the regionally known church builder August Greifzu . The polygonal choir facing east is flanked by a single 54 m high tower with a rich structure. The church is 44 m long and 21.5 m wide. The central nave is 15 m high, the side aisles are 7.5 m high. Above the western side aisle yokes are transverse extensions at different heights, which give the west facade a stately appearance. Inside there is a neo-Gothic interior with colored carved altars.

The most important work of art in the Holy Cross Church was a figure of Our Lady of the "Beautiful Madonnas" type from the early 15th century, which was stolen on November 26, 1985 along with two other sculptures.

The cemetery chapel (former Catholic Holy Cross Church), an unadorned building from 1724/26, is of interest only as a cultural monument. The basement of the tower dates from the Middle Ages.

The former school building at Obere Hauptstrasse 12 was built in 1827/28 according to plans by the grand ducal master builder Schneider from Mainz. In the Grand Duchy of Hesse, the construction of schools has been pushed since the school reform of 1823. The classical building was restored in 1989.

schools

As early as the 16th century there were first elementary schools for parish children in some villages. These denominational village schools became more common in the 17th century and were common practice in the 18th century. A school house in Horchheim is first mentioned in 1758. It was on the Fronberg at the corner of Wilhelm-Röpcke-Straße and was still made entirely of wood. This house was renovated in 1758. Between 1782 and 1826 the existing building at Bahnhofstrasse 1 served as a school and community center. Since 1828 the school was housed in the newly built school building at Obere Hauptstrasse 12. In 1887 another school building was built on the market square (Ob. Hauptstraße 6, today local administration), which was expanded in 1910/1912 by the annex Backhausgasse 7. In 1939 the schools in Horchheim and Weinsheim were merged. From 1971 the Kerschensteinerschule was built as a new elementary and secondary school at Neubachstrasse 57. In 1972, the old school buildings were moved to the Kerschenstein School, which was converted into an integrated comprehensive school (Nelly-Sachs-IGS) in 2008/2009 .

Museums

A local museum has been housed in the community center on the old market square since 1985. It presents finds from prehistory and early history , the bones of mammoths and woolly rhinos , stone axes , Roman coins , but also objects of daily use, documents and pictures etc. from the last centuries.

dialect

The local Horchheim language is commonly referred to as "Platt" by the locals. Horchheim belongs to the Rhine-Hessian dialect area. The Rhine-Hessian belongs to the group of the Rhine-Franconian dialects. For the Worms dialect there is a current description by Alfred Lameli, which is also valid for the closer Worms area. For Horchheim itself, the Wenker questionnaire from 1879/80 with the 40 standard sentences for the linguistic atlas of the German Empire is available.

Festivals

Horchheim summer day

On the fourth Sunday of Lent (Laetare) in Horchheim, as in many other communities in Rheinhessen, South Hesse, Palatinate and Electoral Palatinate, the summer day is celebrated. In addition to the common elements, such as the children's move with summer days, the "Ri, Ra, Ro" song and the burning of winter, the Horchheim customs have some very unusual features, namely the Fronberg legend about the wake-up foundation, the procession of the children to the Fronberg with prayer on the Fronberg, the distribution of the trident alarms to the children and the casting of the remaining trident alarms among the assembled crowd. The starting point of the special Horchheim tradition was undoubtedly an old wake-up foundation for the children on Laetare Sunday. Such bread donations were not uncommon and were often redeemed on the Mid-Fast Sunday Laetare (Gospel of the wonderful multiplication of bread). The old age of the Horchheimer Weckstiftung is documented by a municipal bill from 1753. The Fronberg legend is related to this foundation. The legend reports that a woman killed her child on Fronberg and was executed there. To save her soul, she donated her fortune for the annual distribution of bread to the village children. A dramatization of the Fronberg legend comes from Ernst Kilb . Kilb places the events in the years 1515/1516 because he wants to embed the fate of the child murderer whom he calls "Elsbeth" in a social drama about the oppression of the peasants and the emergence of peasant resistance. As further motifs Kilb brings the killing of the child in the well and the execution by drowning in the same well. Kilb may have drawn the fountain motifs from an oral tradition. It cannot be decided whether the Fronberg saga describes a true event or is just a founding saga created by popular fantasy . The events reported could well have happened that way and fit into the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries. It is conceivable that the bread foundation goes back to a Seelgerät foundation. Such foundations were naturally directed towards the churches. When it was first mentioned in 1753, the foundation was administered by the secular community. The transition of a bread foundation from the ecclesiastical to the secular community can also be proven for Iggelheim. Later tradition reports that the village community received some fields from the estate of the executed woman. The lease income was spent on the summer wakes. The Weckäcker were later sold and the purchase price invested with interest. Now the annual interest income, which in the 19th century was seven guilders, was used for the wake. The Dreizackweck, originally simply called "Sommerweck", only occurs in Horchheim. It is unknown how long and why the Horchheim summer wake is baked in this form. The casting of the Dreizack-Wecken is a custom element borrowed from the carnival. The summer parade probably emerged from the children's fiery walks, as they are still documented for Weinsheim . There have been decorated floats for the summer procession since 1935.

Horchheim notch

The parish fair is traditionally celebrated in Horchheim on the second Sunday in August. The date of the secular parish fair no longer coincides with the anniversary of the religious parish fair (August 29, 1728).

Economy and Infrastructure

Agriculture

The Franconian immigrants, who settled in the lower Eisbachtal at the beginning of the 6th century, lived primarily from livestock farming. Agriculture played a minor role. As the row grave cemetery in Wiesoppenheim, which began with the conquest, shows, one of the first settlements was there. In Wiesoppenheim, the Franconian settlers found good grazing grounds with easy access to the water and, in some places, easily workable sand loess soils. In the beginning only a small part of the available land was cultivated as arable land. Because of the strong population growth since the 7th century, an expansion and intensification of agriculture became necessary. Expansion sites emerged when the new corridors were too far away from the first settlement. Horchheim was at the latest at the beginning of the 7th century. populated. The three-field economy with the alternation of fallow, winter grain and summer grain is an organizational improvement that was introduced particularly early in Rheinhessen and was widespread there as early as the 10th century. Another improvement was the formation of tubs , which is documented in Horchheim as early as the 13th century. The corridor was heavily parceled out, which made it difficult to work economically. The Gewann was a newly created "large unit [of fields] for the purpose of similar and simultaneous cultivation". Viticulture is first documented in Horchheim in 1223. In the high Middle Ages, three -field farming was abandoned in Horchheim and its neighboring towns and replaced by a cell-bound farming system with winter grain and fallow fields. In 1260 a western zone towards Heppenheim and an eastern zone towards Worms are mentioned for Horchheim . With the upswing of cities, trade and finance, there was an increasing demand for winter cereals (mostly rye), while summer cereals brought in less and were at risk from summer drought. The abandonment of summer cereals made it possible to enlarge the fallow pasture and to "expand manure and labor-intensive viticulture". By 1300 most of the Horchheim district must have been cultivated. Triggered by hunger crises and epidemics, there was a massive population decline in the 14th century, which ushered in a centuries-long agricultural depression. Less fertile and remote fields have been abandoned. While grain sales fell, lucrative specialty crops such as fruit growing also experienced an upswing in Horchheim.

Business

The most important industrial company in Horchheim was the chicory coffee substitute and coffee essence factory Pfeiffer & Diller G. m. b. H., which had its headquarters on the site of the former Horchheimer Obermühle from 1875 to 1952. The factory was originally founded in 1843 by Johann Valentin Jungbluth and was initially located in the Mariämünster mill in the Speyer suburb of Worms. The first Jungbluth chicory factory in the Mariämünster mill burned down completely in June 1845. When roasting and grinding chicory roots, the chicory can easily ignite. Jungbluth then relocated his business to the former mountain monastery in Worms Andreasvorstadt. In June 1856 there was another fire there, which destroyed an entire wing of the building. In the factory were u. a. Coffee surrogates made from chicory and acorns and various coffee blends. In October 1872 the company was taken over for 37,000 guilders by the Cologne manufacturers Julius Diller († December 5, 1894) and August Pfeiffer († April 30, 1897). In January 1873 a fire broke out in the mill room of the factory, which burned out completely. In 1874 the owners sold the premises in the former mountain monastery to the leather manufacturer Nikolaus Reinhart, who built the Villa Bergkloster there. With the proceeds, Messrs Pfeiffer and Diller bought the Obermühle in Horchheim and set up their chicory factory there. The factory in Horchheim began in 1875. Chicory substitute coffee blends and, since 1884, a coffee additive essence were produced. This so-called "Diller Essence" became a very well-known branded product valued for its productivity. The essence consisted mainly of caramelized beet sugar and was used to stretch and improve the taste of coffee beans and malt coffee. A roasting plant, essence boilers, storage and packaging building and an office building on Obere Hauptstrasse were built on the factory site. On the slope above the company, Diller had a representative manufacturer's villa built from 1902–1906 by the well-known master builder Heinrich Metzendorf .

Since the 1890s, Pfeiffer & Diller's products have been advertised through elaborate tin cans, advertising stamps, collective pictures and posters. The advertising figure and registered trademark was the "coffee uncle" with a house cap, a symbol of old-fashioned thrift and comfort. After the heyday of the prewar years, there was a shortage and forced management of raw materials for coffee surrogates and coffee essences in the First World War from 1916. This led to the closure of many businesses. In this context, the shares in Pfeiffer & Diller were acquired in 1916 by Heinrich Franck Söhne G. m. b. H in Ludwigsburg. After the war, sales soon returned to pre-war levels. The products were not only sold in Germany, but also abroad and overseas. In 1930 150 people were employed in the company. The care for the workforce was considered exemplary, and there was even a company health insurance company. In the upswing of the 1930s, advertising was also modernized: In 1937 a cinema advertising film "Der Kaffeeunkel sein" was made. In 1943, Pfeiffer & Diller and Emil Seelig AG (Heilbronn), another Franck subsidiary, became the company "Seelig and Diller A.-G." (Heilbronn) merged. Important factory buildings were destroyed in the bombing of Horchheim on February 21, 1945. In 1947, with 35 employees, only 25% of pre-war production could be achieved. The factory finally closed its doors in 1952.

Public facilities

Water supply and sanitation

There were numerous wells in Horchheim for the supply of drinking water . From some public wells, e.g. B. at the Obermühle, in the Angelgasse and in the back alley everyone was allowed to fetch water. Many, but not all, of the houses had private wells. In 1855 there were well communities of neighboring households who shared a well. In 1929 Horchheim and Weinsheim merged to form a water supply association and built their own small waterworks . From 1945 to 1949 the Horchheim waterworks contributed to the emergency supply of the city of Worms. Since 1955, Horchheim has received its water from the Bürstadt waterworks of Stadtwerke Worms (since 2002: EWR AG ). The waste water - sewage system was completed in Horchheim 1976th

power supply

After the Rheinhessen (EWR) electricity works was founded in Worms in 1911 , Horchheim was connected to the EEA power grid in 1912 . The low-voltage local network receives electricity via a 20 kV medium voltage - transmission line from the substation Osthofen the EWR AG. 1950 Horchheim was to the gas grid of Stadtwerke Worms connected. City gas was initially supplied , followed by natural gas later .

Railroad and bus

Since 1886 Horchheim was connected to the rail traffic by a single-track railway line Worms-Grünstadt . The railway was operated by SEG until 1953 , then by Deutsche Bundesbahn . The branch line was managed at Horchheim station until 1953. City buses have been running from Horchheim and Weinsheim to Worms since 1949. As a result, there were heavy losses in passenger transport by rail. Horchheim station was closed in 1968 for passenger traffic and in 1969 for goods traffic. The tracks in Horchheim were dismantled at the end of the 1970s.

post Office

The oldest postal rate in Germany, the so-called Dutch postal rate , ran right past Horchheim since the 16th century. The street name "Postweg", which was first mentioned in 1710, describes a section of the path that the post rider took between the post stations of Bobenheim and Hangen-Weisheim . The Hangen-Weisheim post office already existed in 1570 and was moved to Alzey in 1703. The Bobenheim Poststation already existed in 1540, it was relocated to Worms in 1707. At the beginning of the 16th century, the route through Rheinhessen was not yet permanently fixed, but was changed several times: in 1506 Heppenheim an der Wiese and in 1522 Pfiffligheim were given as the post office. It can therefore be assumed that the mail route had been running near Horchheim since the beginning of the 16th century. Since 1703/1707 the postal rate no longer ran via Horchheim, but via Worms.

Horchheim itself only received mail from around 1799, when a messenger service for the canton of Pfeddersheim was set up in the Donnersberg department . The messengers carried the official mail to and from the mayor's offices of the canton on foot and also carried private mail for a tip. The messenger system for service mail was continued by the new Hessian administration in 1816 and reorganized in 1825. From 1825 the messengers were called Bezirksboten and went on a tour of Horchheim twice a week. The postage was now precisely set for private shipments. In 1861 the state messenger system was taken over and improved by the private Thurn-und-Taxis-Post : Horchheim received its first mailbox, which was attached to the parish hall. In 1865 the country postman came to Horchheim six times a week. The postal service was transferred to the Prussian Post in 1867 , to the North German Federal Post Office in 1868 and to the Reichspost in 1871 . Horchheim received its own post office in 1886 when the place was connected to the Worms-Offstein railway line , which was equipped with telegraph in 1888 . The post office was located at Oberen Hauptstrasse 24. Horchheim had an independent post office since 1900 , which was responsible for Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wies-Oppenheim. The post office was in Oberen Hauptstrasse 1. Telephones were probably only available in Horchheim after 1900. In 1928 Horchheim was attached to the Worms post office as a branch post office. In 1976 the company moved to Untere Hauptstrasse 63-65. The 1995 postal reform turned the post office into a post office, which was closed at the beginning of 1999. Since 1999 there is only one post agency of the Deutsche Post AG in Horchheim .

Streets and paths

The oldest routes in the Horchheim district are two old long-distance routes, on the one hand Eisenberger Strasse , which led from Worms through the Eisbachtal to Kaiserslautern, and on the other hand the Hochstrasse , also known as Bockenheimer Weg , which formed the boundary between Horchheim and Pfiffligheim and from Worms went to Kleinbockenheim. Eisenberger Straße must have served as a long-distance connection as early as the late Bronze Age. Presumably this long-distance path originated from footpaths that were perhaps already used in the Neolithic. The prehistoric long-distance path was fortified in Roman times; H. expanded to " street ". Today the route is only known for sections of the paved path. Eisenberger Straße, which was an important traffic connection in the Franconian era, had lost its importance by the end of the 13th century and had fallen back to the rank of a local connection between Horchheim and Worms. Instead, the road to Kaiserslautern now ran via Weinsheim, Wiesoppenheim and Dirmstein. The second old long-distance route near Horchheim, the Hochstraße , came in the Middle Ages as the Breiter Michelsweg from the Michaelspforte in Worms, formed the border between Horchheim and Pfiffligheim as an Hochstraße , ran as Bockenheimer Straße along the southern edge of the Pfeddersheim district to Hohen-Sülzen and from there as Wormser Straße to Kleinbockenheim and further into the Eisbachtal. This path probably dates back to at least Roman times. The route of the old elevated road on the Horchheim - Pfiffligheim border is now under the B 47n and the Worms junction of the A 61 . The B 47n and A 61 in the Horchheim area were built from 1973 and opened to traffic in 1975.

Personalities

Sons and daughters of the place

- Johannetta (Jeannette) Hirsch Meier (1843–1925), entrepreneur, wife of Aaron Meier, the founder of the former department store group Meier & Frank in Portland (Oregon)

- Karl Noll (1883–1963), member of the Hessian state parliament

- Hermann Schmitt (1888–1974), grammar school teacher, Rheinhessen church historian and local researcher

- Alois Seiler (1909–1997), historian and educator

- Alois Seiler (1933–1992), archivist and historian

- Harald Braner (* 1943), football player

People who have worked here

- Konrad Schredelseker (1774–1840), village school teacher and land surveyor

- Matthias Erz (1851–1899), Cath. Clergyman, alternative practitioner and archaeologist, chaplain in Horchheim 1875–1883

- Ernst Kilb (1896–1946), teacher, historian and poet, Lord Mayor of Worms 1945–1946

- Ulrich Neymeyr (* 1957), Catholic from 2000 to 2003 Pastor of Horchheim, since 2014 Bishop of Erfurt .

literature

- W. Schredelseker: Horchheim. A compilation of everything remarkable from his past and present. Worms 1896.

- Karl Johann Brilmayer : Rheinhessen in the past and present. History of the existing and departed cities, towns, villages, hamlets and farms, monasteries and castles in the province of Rheinhessen along with an introduction. Giessen 1905. ND Würzburg 1985.

- Hermann Schmitt : History of Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wies-Oppenheim. Worms 1910.

- Edmund Heuser: Horchheim - Weinsheim. o. O. [Worms-Horchheim] o. J. [1978] and Edmund Heuser: Worms-Horchheim-Chronik. o. O. [Worms-Horchheim] o. J. [2005].

- Georg M. Illert: The prehistoric settlement picture of the Worms Rhine crossing. Worms 1952 (= Der Wormsgau , supplement 12).

- Hellmuth Gensicke: The inhabitants of the Worms Rhine villages in 1496. In: Palatinate family and heraldry. 1 (1952), pp. 56-61.

- Hermann Schmitt: Heiligkreuz in Horchheim near Worms. Pastor and parish in the 18th century. In: Archive for Middle Rhine Church History, Volume 17 (1965) pp. 294–333 (= Part I) and Volume 18 (1966), pp. 329–365 (= Part II).

- Hermann Schmitt: Jakob Sauer from Bingen, pastor in Horchheim near Worms (1816–1827). Mainz [1965] (printed as a manuscript).

- Valentin Kulzer: Priests and religious from the parish Heilig-Kreuz Worms-Horchheim. Bürstadt 1990.

- Michael Zuber: On the history of the Evangelical Church Community Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim. o. O. [Worms-Horchheim] o. J. [1998].

- Ernst Wörner: Art monuments in the Grand Duchy of Hesse. Province of Rheinhessen. District of Worms. Darmstadt 1887. Chap. 22, Horchheim pp. 87-88.

- Georg Dehio: Handbook of the German art monuments . Rhineland-Palatinate Saarland. Edit v. Hans Caspary et al. a., Darmstadt 1985, p. 1187.

- Cultural monuments in Rhineland-Palatinate. Vol. 10 City of Worms. Edit v. Irene Spille. Worms 1992. pp. 234-241.

- Walter Hotz : The "Beautiful Madonna" from Horchheim and the art of her time in the Worms landscape . In: The Wormsgau . tape 14 , 1986, pp. 101–111 ( [26] [PDF; 1.6 MB ; accessed on April 18, 2011]).

- Hans Ramge: The settlement and field names of the city and district of Worms. 2nd edition, Giessen 1979 (= contributions to German philology, vol. 43). On the place name “Horchheim” p. 31–32.

Web links

- News about Horchheim on the website of the city of Worms

- Maps and aerial photos of Horchheim in the LANIS landscape information system

- Stadtarchiv Worms: Stock 02 Incorporated suburbs 042 Municipality archive Horchheim

- Regional history

Individual evidence

- ↑ Residents of the city of Worms by type of residence (PDF; 14 kB), residents with main residence in Worms (or suburbs) on the respective survey date

- ^ Hartmut readers: Regional history guide through Rheinhessen. Berlin / Stuttgart 1969, map 4 after p. 62, p. 64 f., P. 117 and p. 136; Rhineland-Palatinate - State Agency for Geology and Mining - online soil map: .

- ↑ Dieter Berger: Old ways and roads between Moselle, Rhine and Fulda. In: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 22 (1957) pp. 176–191, therein p. 179 (Römerstrasse No. 12), p. 181 (overview map), p. 182 and 187–189. Theo Uhrig: Palatinate and Diocese of Worms in Carolingian times. In: Middle Rhine contributions to the Falzes research. (Workshop in Speyer 1963), Mainz 1964, pp. 46–70 and discussion pp. 71–76, therein pp. 49 f., 71 f. Michael Gockel, Karolingische Königshöfe am Mittelrhein, Göttingen 1970, p. 13 f., Ramge p. 340. Another branch of the road from Worms to Kaiserslautern led through the Pfrim valley, cf. Ramge p. 338–340, Ernst Christmann, The Franconian Königshof-System der Westpfalz, in: Mitteilungen des Historischen Verein der Pfalz, 51 (1953) p. 129–180, therein p. 137–139, Heinrich Büttner, Das Bistum Worms and the Neckar area during the early and high Middle Ages, in: Archiv f. middle rhine. Church halls 10 (1958) pp. 9-38, therein p. 20.

- ↑ Geoportal of the city of Worms. Retrieved January 31, 2016 . there: topics => districts and borders.

- ↑ The area of the city of Worms was divided into districts in 1974. Up until this reorganization in 1974, the district boundaries served as the boundaries of the incorporated suburbs. When designing the city districts, the old district boundaries were deliberately deviated from when other dividing lines (streams, traffic routes, etc.) appeared more suitable as administrative boundaries, cf. Detlev Johannes: Pfiffligheim and its district and new political borders . In: Heimatverein Worms-Pfiffligheim e. V. (Ed.): Annual issue 2007: Pfiffligheimer streets and alleys . S. 9-11 .

- ↑ Type of dense street village: Heinz Ellenberg: Farmhouse and landscape from an ecological and historical perspective . Stuttgart 1990, p. 161, 181 f., 185, 399 f .

- ↑ Hansjörg Küster: History of the landscape in Central Europe . Munich 1995, p. 159 f., 176 f .

- ↑ The stream is not far from the village. Wells only need a shallow depth.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Nitz: The local and corridor forms of the Palatinate . In: Willi Alter (ed.): Pfalzatlas . Text volume I. Speyer 1964, p. 204-224, therein p. 216 .

- ↑ Heuser 1978 p. 57 f.

- ↑ On street village and closed village or Haufendorf cf. Martin Born: Geography of the rural settlements. The genesis of rural settlements in Central Europe . Stuttgart 1977, p. 32-34, 117 ff., 141-148 .

- ↑ For the chronological sequence of the development cf. Cultural monuments in Rhineland-Palatinate p. 234.

- ↑ On floor forms in general and on Gewannflur: Martin Born: Geography of rural settlements. The genesis of rural settlements in Central Europe . Stuttgart 1977, p. 34-38, 170, 173-182 .

- ↑ Horchheim real estate cadastre in the LANIS landscape information system. Retrieved October 2, 2014 .

- ↑ See Erich Otremba: History of the development of the corridor forms . In: Hans-Jürgen Nitz (Ed.): Historical-Genetic Settlement Research . Darmstadt 1974, p. 81-107, therein p. 99 .

- ↑ Ramge, p. 62.

- ↑ Turning the plow, which was covered with draft animals, was laborious, especially with multiple covering, which is to be expected in stony, heavy or steep fields. In the Middle Ages, long-striped fields were therefore often more practicable than short fields, cf. Alois Gerlich: Historical regional studies of the Middle Ages . Darmstadt 1986, p. 195 f .

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Nitz: Orts- und Flurformen der Pfalz . In: Willi Alter (ed.): Pfalzatlas . Text volume I. Speyer 1964, p. 204-224, therein pp. 221-223 . , Commented Hans-Jürgen Nitz: Map 38: Village and hallway of the Palatinate I . In: Willi Alter (ed.): Pfalzatlas . Map volume I. Speyer 1963.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Nitz: Regular long strip corridors and Franconian state colonization . In: Hans-Jürgen Nitz (Ed.): Historical-Genetic Settlement Research . Darmstadt 1974, p. 334-360, therein pp. 341-348 .

- ^ Karl S. Bader, Gerhard Dilcher: German legal history . Berlin 1999, p. 89-91 .

- ^ Franz Staab: Investigations into society on the Middle Rhine in the Carolingian period . Wiesbaden 1975, p. 229-232 . and Gerlich, Geschichtliche Landeskunde , p. 180.

- ↑ Justin Bender makers: village forms in Rhineland-Palatinate . Cologne 1981, p. 10–15,87,130–133,144 (The center of Horchheim has similar homestead types to the town of Freimersheim described on p. 130 ff.).

- ^ Cultural monuments in Rhineland-Palatinate, pp. 234 ff.

- ↑ For the house type "Einfirsthof" cf. Ellenberg p. 42 ff.

- ↑ For house type "small house" cf. Rolf Reutter: House and yard in the Odenwald . 2. verb. Edition. Heppenheim 1994, p. 95 ff .

- ^ Dietrich Maschmeyer: Geckpfahl - Husbrant - Brantstang. A puzzling roof ornament . In: The wooden nail . Vol. 31, 1 (Jan / Feb), 2005, pp. 18-26 .

- ↑ The gable post appears in the Worms area as early as the 17th century: on the view of Hochheim on the map of the camp of the von Waldmannshausen regiment from 1621/1622 (Worms City Archives: Collections - Graphic Collection - City Views - Inv-No. 6 / 54) gable posts can be seen in many houses. See Fritz Reuter: Peter and Johann Friedrich Hamman . Worms 1989, p. 30–31 (ill. On p. 31). An enlarged section with the view of Hochheim printed by: Detlev Johannes: Worms-Hochheim and Worms-Pfiffligheim. Old villages - new districts . Alzey 1998, p. 136 .

- ↑ a b Hubert Heitele, Volker Sonne: Geological overview . In: Geological State Office Rhineland-Palatinate (Ed.): Soil map of Rhineland-Palatinate 1: 25000. Explanations sheet 6315 Worms-Pfeddersheim . Mainz 1989, p. 9-11 .

- ^ Karl RG Stapf: On the tectonics of the western edge of the Rhine rift between Nierstein am Rhein and Wissembourg (Alsace) . In: Annual reports and communications from the Upper Rhine Geological Association . NF 70, 1988, p. 399-410 (therein p. 404 f. And Fig. 1).

- ^ A b Wilhelm Weiler: Pliocene and Diluvium in southern Rheinhessen. Part II. The Diluvium . In: Notes of the Hessian State Office for Soil Research in Wiesbaden . F.6 Vol. 81, 1953, pp. 206–235 (therein p. 223 ff. Obsolete but detailed representation of the tectonics in the Worms area).

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Scharpff: Geological map of Hessen 1: 25,000. Sheet 6316 Worms . Ed .: Hessian State Office for Soil Research. Wiesbaden 1977.

- ^ A b Eckart Fr. Schneider, Hans Schneider: Synsedimentary fracture tectonics in the Pleistocene of the Upper Rhine Valley rift between Speyer, Worms, Hardt and Odenwald . In: Münster research on geology and palaeontology . Issue 36, 1975, pp. 81-126 (therein pp. 88 f., 91-93, 105-109, 112 plate I, 115 plate IV, 118 plate VIII).

- ↑ Bore GÖ2

- ↑ Hole 1018

- ↑ F. Wenzel, J.-P. Brun: A deep reflection seismic line across the Northern Rhine Graben . In: Earth and Planetary Science Letters . tape 104 , 1991, pp. 140-150 .

- ↑ Christian E. Derer, Markus E. Schumacher, Andreas Schäfer: The northern Upper Rhine Graben: basin geometry and early syn-rift tectono-sedimentary evolution . In: International Journal of Earth Sciences . tape 94 , no. 4 , 2005, p. 640-656 (therein p. 643 Fig. 3 seismic section S2). on-line

- ↑ Jochen Ottenstein, Athanasios Wourtsakis: Soil map of Rhineland-Palatinate 1: 25000. Sheet 6315 Worms-Pfeddersheim . Ed .: Geological State Office Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 1988.

- ↑ M. Körschens, M. Altermann, I. Merbach, J. Rinklebe: Soils as our basis of life. Black earth is the soil of the year 2005. (PDF; 1.3 MB) pp. 3–5 and 26–28 , accessed on November 1, 2016 .

- ↑ Minst, Karl Josef [transl.]: Lorscher Codex (Volume 3), Certificate 900, in the year 766 - Reg. 90. In: Heidelberg historical stocks - digital. Heidelberg University Library, p. 39 , accessed on April 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Rudolf Kraft: The Reichsgut in Wormsgau. Darmstadt 1934, pp. 125-127, 132-134. Uhrig, Pfalz and Diocese of Worms pp. 55–59. Gockel, Königshöfe pp. 34, 38 f., 47, 174, 205 f.

- ↑ MGH DD Arn No. 153 and No. 158

- ↑ Schmitt 1910 p. 7; Alois Seiler, Das Hochstift Worms in the Middle Ages, Worms 1936 (= Der Wormsgau Beih.4), pp. 19–23, esp. P. 22; Hans Werle, studies on the Worms and Speyer high priests in the 12th century, in: Blätter f.pfälz.Kirchengesch.u.relig.Volkskunde 21 (1954) pp. 80–89, therein pp. 82 f .; Meinrad Schaab: The Diocese of Worms in the Middle Ages. in: Freiburger Diözesan-Archiv 86 (1966) pp. 94–219, therein pp. 148–151; Karl Heinz Debus: Article Saarbrücken, Grafschaft in: Gerhard Taddey (Hrsg.): Lexicon of German history. Stuttgart 1979, pp. 1047-1048.

- ^ Johann Georg Lehmann: The county and the counts of Spanheim of the two lines Kreuznach and Starkenburg up to their extinction in the fifteenth century. Kreuznach 1869, ND Vaduz 2002, pp. 111, 114, 117-119; Schmitt 1910 pp. 7-8; Schaab pp. 150-151.

- ^ Gerhard Köbler : Historical Lexicon of the German Lands. The German territories and imperial immediate families from the Middle Ages to the present. 6th, completely revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-44333-8 , therein: p. 417: article Nassau-Saarbrücken and p. 418–419: article Nassau-Weilburg .

- ↑ Alois Seiler: The wisdom of the villages Roxheim, Bobenheim, Mörsch, Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim. In: Der Wormsgau Vol. 2 Issue 5 (1941), pp. 297-300; Schmitt 1910 pp. 8-9; Adolph Köllner: History of the rule Kirchheim-Boland and Stauf. Wiesbaden 1854, therein pp. 308–313 on the Worms Rhine villages; Rolf Kilian: The exchange of territory from 1706 between the Hochstift Worms, the Electoral Palatinate and Nassau. In: Der Wormsgau Vol. 3, 1951/58, pp. 404-405.

- ↑ Friedhelm Jürgensmeier (ed.): Das Bistum Worms , Würzburg 1997, pp. 254-259.

- ↑ For the prehistoric finds in Horchheim, Weinsheim and Wiesoppenheim see: Georg M. Illert, Siedlungsbild p. 90, 99-102, 110 f., 117, 126, 133 and 140. For the finds from Horchheim see: Heuser 1978 p. 5. For the absolute chronology of the prehistory in southern Rheinhessen cf. the time table in the anthology "Archeology between Donnersberg and Worms", Regensburg 2008, pp. 278–281.

- ^ Mainzer Archäologie Online 9 [1] No. 5946.

- ↑ On the Neolithic in southern Rheinhessen see: Birgit Heide, Andrea Zeeb-Lanz: Das Neolithikum, in: Archäologie between Donnersberg and Worms, Regensburg 2008, pp. 43–54, therein p. 52.

- ↑ Georg M. Illert: The prehistoric settlement picture of the Worms Rhine crossing. Worms 1952, Heuser 1978 p. 5, Edmund Heuser: Heimatmuseum Worms-Horchheim. o. O. [Worms-Horchheim] 1985 p. 7 Figure below left. Ludwig Lindenschmit (ed.): The antiquities of our heathen prehistory. Vol. 1, Mainz 1864, therein booklet 1, plate 2 swords (ore) No. 8 [2] (in the PDF: p. 28 f.). Gustav Behrens: Land documents from Rheinhessen. Mainz 1927, p. 28, no. 102. John David Cowen: An introduction to the history of the bronze hilted swords in southern Germany and the neighboring areas, in: Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute. [36]. Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 1955, Berlin 1956, pp. 52–155, therein pp. 96 and 144. On p. 144 it says: “Although supposedly 'from a grave', this seems unlikely in view of the excellent state of preservation, and the In reality, the circumstances of the find are unknown. ”Copy in Museum Worms (Inv.-No. BE 144). On the late Bronze Age in southern Rheinhessen, see: Dirk Brandherm: The late Bronze Age, in: Archeology between Donnersberg and Worms, Regensburg 2008, pp. 65–76.

- ↑ Georg M. Illert: The prehistoric settlement picture of the Worms Rhine crossing. Worms 1952; one of them in the "Hindenburgstraße" (today: Untere Hauptstraße), of the other graves the place of discovery is unknown. There is no assignment of the finds to a Latène stage. On the Latène period and the Celts in southern Rheinhessen cf. Leif Hansen, Martin Schönfelder: The Iron Age in southern Rheinhessen, in: Archeology between Donnersberg and Worms, Regensburg 2008, pp. 77–84.

- ↑ Mainzer Archäologie Online 9 [3] Nos. 5942, 5943, 5944, 5945, 5948.

- ↑ Gerold Bönnen (Ed.): Geschichte der Stadt Worms, Stuttgart 2005, p. 77.

- ↑ Hans Gebhart, Konrad Kraft (Hrsg.): The coins found in the Roman period in Germany. Dept. IV Rhineland-Palatinate. Vol. 1 Rheinhessen. Edit v. Peter Robert Franke, Berlin 1960 (hereinafter cited as: Franke, Fundmünzen), p. 417 no. 1221, Heuser 1978 p. 5.

- ^ Franke: Fundmünzen p. 417, Mathilde Grünewald, Erwin Hahn, Klaus Vogt: Between Varus Battle and Völkerwanderung , 2 vols., Lindenberg 2006, vol. 2, p. 414, Heuser 1978 p. 5.

- ↑ Mathilde Grünewald, Erwin Hahn, Klaus Vogt, Between Varusschlacht und Völkerwanderung, 2 vols., Lindenberg 2006, vol. 2, p. 414, Mathilde Grünewald's article "Worms-Horchheim", in Heinz Cüppers (ed.): Die Römer in Rhineland-Palatinate , Stuttgart 1990, p. 680. Heuser 1978 p. 5 there but “1937”.

- ^ Heinrich Bayer, The rural settlement of Rheinhessen and its peripheral areas in Roman times, in: Mainzer Zs., 62 (1967) pp. 125–175, therein p. 175; Franke, Fundmünzen p. 417; Heuser 1978 p. 5.

- ↑ Heuser 1978 p. 5, Heuser 2005 p. 5 there incorrectly to “Around 500 BC. Chr. "Dated. A glaze in a stone container is to be addressed as Roman. In Heuser, Heimatmuseum Worms-Horchheim, objects from this cremation grave from “In den Kesselwiesen” are clearly shown on p. 7 in the top right illustration. Unfortunately, the photo is labeled incorrectly. A villa rustica may also have been located near this rich burial.

- ^ Franke, Fundmünzen p. 417

- ^ Mathilde Grünewald Art. "Worms-Horchheim", in Heinz Cüppers (Ed.): The Romans in Rhineland-Palatinate, Stuttgart 1990, p. 680. Helmut Bernhard , The Roman History in Rhineland-Palatinate, ibid. P. 87. Bönnen, History of the City of Worms p. 66. Mainzer Archeology Online 9 [4] No. 5944.

- ^ Bönnen: History of the City of Worms. P. 77. Peter Haupt: Settlement archeology of Roman times in southern Rheinhessen. In: Archeology between Donnersberg and Worms. Regensburg 2008, pp. 93-96. Helmut Bernhard, Die Römerzeit in the northern Front Palatinate and in the North Palatinate Bergland, ibid. Pp. 97-105, especially p. 100. Hansjörg Küster, Geschichte der Landschaft in Mitteleuropa, Munich 1995, p. 159 f.

-

↑ Helmut Bernhard: The Roman History in Rhineland-Palatinate, in: Heinz Cüppers (Ed.): The Romans in Rhineland-Palatinate, Stuttgart 1990, pp.