History of typography

The history of typography provides a chronological overview of the development of the writing culture. Today the focus is primarily on the historical development of the various types of printing .

Subjects of the history of typography

- The focus of the history of typography is the historical development of the different types of fonts ( antiqua , sans serif and display fonts) up to today's typography on the Internet. The manuscripts before the invention of printing, on the other hand, are usually counted as prehistory. For the historical development of writing , see also History of writing and palaeography .

- The western history of typography is naturally limited to the catchment area of the Latin alphabet - that is, western and central Europe, North and South America and the central and southern areas of the African continent. The focus is mostly on the developed countries of Western Europe and the USA. For the development of the different alphabets worldwide see Fonts of the World , Alphabet and Alphabet Font .

A subject closely related to the history of typography is the history of graphic design as well as the history of graphic styles . In contrast to graphic design, which deals with general design principles, typography focuses more on the use of fonts and typographic conventions. The history of typography deals primarily with

- the historical development of printed matter,

- technical innovations insofar as they are relevant for the use of fonts (letterpress, lead , machine and photo typesetting , desktop publishing ; OpenType ),

- the historical development of typographical conventions and systems of measurement.

Handwritten prehistory of Latin pamphlets

(see in detail palaeography - history of the Latin script )

From the advent of writing as such in antiquity to the beginning of printing at the end of the Middle Ages , the creation of documents and books was a handwritten affair. The shape of the Latin script changed several times during this period. The most important pre-forms of printed scripts known to us today are: Roman capitalis , early medieval uncial scripts , the Carolingian minuscule and the Gothic-fractional scripts of the high and late Middle Ages. These pre-forms are relevant to typography history for three reasons:

- the merging of uppercase and lowercase alphabet over the course of a millennium ,

- the formal development towards the current letter forms and finally

- As a historicizing reference option: Unlike the print prototypes still used today, such as the Garamond from the 16th century, digital Capitalis, Uncial or Textura fonts are primarily used to set historical epochs in the spotlight with typography.

Roman capitalis

The preforms of today's Latin alphabet came from the Etruscans and Greeks in the course of the first millennium BC. To the Romans . The Roman alphabet already largely corresponded to that used today. However, it was an all-uppercase alphabet. The capitalis monumentalis is now considered to be the capital of the Roman Empire . The best-known historical document of this monumental script are the inscriptions on the Trajan's Column, erected in 113 AD . In addition to the monumental fonts , mainly carved in stone, there were also more informal font variants such as the Capitalis quadrata , the Capitalis rustica as well as the older Roman italics and the younger Roman italics . In addition to being used as a book font, they were primarily used to cope with informal, everyday correspondence.

Uncial scripts

In the Roman Empire, too, the scriptures were subject to a slow process of change. The writing culture of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages was characterized by uncial and semi- uncial script . Their origin was derived from the more informal writing variants of the Roman script (older Roman italics, younger Roman italics). In the Anglo-Saxon area, characters from runic scripts were added for individual sounds ( thorn for th ). The uncial script has an uppercase alphabet; the semi-uncial, which has been used since the 3rd century, also uses ascenders and descenders to distinguish letters and therefore has a lowercase alphabet.

In addition to the uncial and semi-uncial, a number of regional writing forms developed from the Roman italics. As they were primarily of local importance, they are also grouped under the generic term national scripts, whereby their use is not determined by ethnicity or politics, but primarily has a geographical reference. In terms of development history, the writings of the early Middle Ages are the immediate forerunners of the Carolingian minuscule.

The uncial is still used today in Christian contexts, for example for inscriptions in churches or on tombstones. Modern reinterpretations of the uncial script such as the American Uncial can be found in the fantasy area or in the esoteric scene. A well-known application example can be seen in the film adaptation of the Tolkien bestseller The Lord of the Rings .

Carolingian minuscule

With the support of the Carolingians , who had ruled large parts of Central Europe since the end of the 8th century , the Carolingian minuscule spread across Europe. The main trigger for their widespread establishment were the educational reforms of Charlemagne (the so-called Carolingian reform). The last time the script penetrated Spain ( Visigoth minuscule ), Great Britain ( Insular scripts ) and southern Italy ( Beneventana , Curialisca ).

The Carolingian minuscule is the model for the lowercase alphabet in its form that is still used today. The copies of ancient authors (for example Horace , Virgil , Homer ) in monastic scriptoria led Renaissance scholars to believe that the Carolingian minuscule was the original script of antiquity . From the 14th century onwards, based on the Carolingian scripts in Italy, the humanistic minuscule was created , which became the model for the first Renaissance scripts ( Venetian Renaissance Antiqua , from around 1470). In contrast to the contemporary high medieval fonts (the Textura and the Rotunda), this new font was called "antique" (Latin antiquus) in order to differentiate it from the fonts that were created later. The term "Antiqua" is derived from this.

Gothic fonts

From the late Carolingian minuscule, the Gothic book scripts developed in the High Middle Ages . Its numerous variants were all characterized by a regular, strict, closely written typeface. The curves of the letters were broken, which is why these fonts are also referred to as broken fonts - especially to distinguish them from the later antiqua fonts . The main feature of the Gothic or broken fonts was a tight, dark typeface, the structure-like shape of which is strongly reminiscent of woven fabrics; hence the name Textura is derived for the most famous font of this era.

At the same time, an alternative form of Gothic script developed in Italy, Spain and, to a lesser extent, Germany: the rotunda or round Gothic. With the round Gothic script, the shapes are wider and the letters have curves instead of hard angles. This made the writing more legible. Both fonts were adopted by the early printers of the so-called incunable period . By the middle of the 16th century, however, they were largely superseded by other scripts.

Another development of the high medieval Gothic were preforms of today's italic fonts . Italic fonts were adapted for use in books and so developed into the so-called Bastarda fonts . In Central Europe, the Fraktur emerged as a continuation of the Textura at the end of the Middle Ages . The Gothic fonts that emerged at the beginning of the 16th century were successful and also provided the models for the font designs by Albrecht Dürer and Johann Schönsperger . The Schwabacher , which also emerged at the beginning of the 16th century, is a crude, folk development of the Textura . Together with Fraktur, it determined the print image in Germany well into the 20th century. In the countries around the Mediterranean, the main distribution area of the Rotunda, however, the Antiqua typefaces prevail.

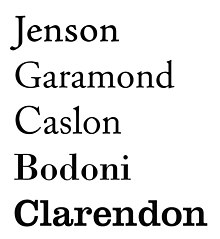

History of publications up to the 20th century

In contrast to the historical typefaces described so far, the typefaces developed from the early modern period are not written typefaces, but printed fonts. The main model, the Antiqua , which emerged from around 1450 , forms the basis of currently used fonts to this day. The fine-tuning of antiqua fonts, on the other hand, went through several stages of development since the Renaissance era. The typeface classification divides these into the main groups Renaissance antiqua , baroque or transitional antiqua and classical antiqua . From the 19th century as more fonts came serif linear Antiqua and sans serif sans serif fonts added.

Origin of the Antiqua

In the course of the early Renaissance , there was also a renewed interest in the written forms of antiquity. The center of development was Italy . Unlike in the north, the moderately Gothic model of the rotunda was established here early on. Gutenberg's 42-line Bible from 1455 was based on the best Gothic manuscripts. Just ten years later, German printing masters in Subiaco (Italy) and Venetian successors such as Nicolas Jenson and Aldus Manutius recognized that the new technology also made a different design possible. Following the example of Italian humanist manuscripts, they combined the "revised" lowercase letters of the Carolingian minuscule with the uppercase letters of the Roman capitalis. This created a two-alphabet font that clearly stood out from the broken fonts of the High Middle Ages - the so-called "Antiqua".

The image of the first antiqua typefaces was still heavily influenced by medieval, Gothic elements. The development towards the uppercase and lowercase letters used today only took place slowly in the course of the following centuries and varied from country to country. In addition, the type designers and die cutters of the Renaissance integrated two further character components into their contemporary fonts: on the one hand, the Arabic numerical system , originally from India, and on the other hand, italics . The latter were Bastarda variants, which some typists of the late 15th century adapted to the appearance of the Antiqua. The Antiqua italics, also known as "Italics", only developed into integrated typefaces of complete typeface families in the course of the following centuries .

Renaissance (1400 to 1600)

The Renaissance Antiqua (other names: Old Style Antiqua or older Antiqua) can be divided into two stylistically clearly delimited groups: the Venetian Renaissance Antiqua and the French Renaissance Antiqua .

In the Venetian Renaissance Antiqua, the stylistic features of which developed between 1455 and 1485, the derivation of late medieval Rotunda and Bastarda scripts can still be recognized to a greater or lesser extent. The best-known exhibit of this group is the Jenson Antiqua , created by Nicolas Jenson around 1470 ; a contemporary interpretation is the 1996 Adobe Jenson by Robert Slimbach . The line widths of this type are relatively uniform. The calligraphic style of drawing emerges clearly. Unlike later antiqua typefaces, early antiquas of this type create a more or less pronounced historicizing, late medieval impression and are therefore rarely used in today's typesetting.

Antiqua achieved its classic form, which is still valid today, with the Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius and his die cutter Francesco Griffo . The Bembo , named after a contemporary cardinal and built around 1495, is considered the prototype of this phase. It is still used regularly in book typesetting to this day. Another Griffo innovation was the development of italics. Overall, the fonts created between the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century, although largely originated in Italy, are already included in the model of the French Renaissance antiqua. Some writing historians also refer to the Italian writings of the early modern period as " Aldinen " - as a delimitation term to the Garalden type , which emerged in the 16th century and characterizes the writings from the era of Claude Garamond.

The Parisian die cutter Claude Garamond (1499 to 1561) is now the most famous representative of the French Renaissance Antiqua. By 1600 the typeface he designed had become the predominant book typeface in Europe. It is characterized by a calm, harmonious and light typeface and has pronounced ascenders and descenders. Because of its formal qualities and good legibility, it is still used today and offered in various recuts by numerous font manufacturers. A contemporary of Garamond was the Lyon-based die cutter Robert Granjon (1513 to 1589). Based on historical scripts, Granjon tried, among other things, the ambitious Lettre de Civilité script project . The Civilité planned as a new French general writing failed due to a lack of acceptance.

Baroque (1600 to 1760)

At the beginning of the 17th century, the center of font development increasingly shifted to the Netherlands. The main initiators were the two merchants and publishers Christoffel Plantijn (1520 to 1589) and Louis Elzevir, born in 1540 . The Antwerp- based Plantijn obtained numerous matrices and templates from Garamond's legacy; Among other things, he employed the French die cutter Jakob Sabon (or Jacques Sabon ; * 1535, † between 1580 and 1590). Christoffel van Dijck (1601 to 1699), one of the most important die cutters of his era, worked for the company founded by Elzevir in Leiden (later: The Hague ) . Other important typeface designers of the 17th century are the German Anton Janson and the Hungarian Mikolós Tótfalusi Kis (also Miklós Tótfalusi Kis or Nicholas Kisz; 1650–1702). For the 18th century, Johann Michael Fleischmann (1701–1768) from Nuremberg , who was also temporarily active in the Netherlands, should be listed.

In general, the transition between Garamond's typefaces and the Dutch antiqua typefaces took place slowly and continuously - which is why the typefaces of this era are also known as transitional antiquas. The Dutch typefaces looked simple, often tough and, above all, proved to be usable. Digital recuts of the writings by Janson, Van Dijck, Kisz and Fleischmann are also still regularly used in book typesetting. The Plantin, a reminiscence of the Dutch baroque typefaces by the American type designer Frank Hinman Pierpont (1860–1937) from 1913, ultimately served as a template for the design of what is probably the best-known baroque antiqua of all - the Times , created between 1931 and 1935 .

Compared to the older Renaissance antiqua typefaces, the Dutch and British transitional antiquities of the 17th and 18th centuries appear more sober. On the other hand, the contrasts between the base and the hairline gradually come to the fore; the fonts appear more contrasting overall. One of the main reasons for this development: unlike the font designs of the 16th century drawn with a broad pen, the font designers of the 17th and 18th centuries were increasingly inspired by the precise forms of contemporary copperplate engravings.

The baroque or transitional phase of Antiqua is formally brought to a close by British typefaces of the 18th century. In the beginning, their designers were strongly based on Dutch models. The most famous type designer of this era was William Caslon . From a stylistic point of view, Caslon's writings brought little innovation. For this they were popular and ultimately so widespread that they were used by the British royal family as well as in the drafting and distribution of the US Declaration of Independence . Caslons Epigone was the British printer and die cutter John Baskerville . In contrast to Caslon, Baskerville was considered a perfectionist; his high-contrast typefaces, such as the Baskerville , which were heavily influenced by copperplate engraving , also had a strong influence on the classicist type designers.

Classicism (1760 to 1830)

The development of the Antiqua reached its preliminary end in classicism. Due to technical developments, the letters became more and more contrasting, the serifs more and more delicate. Fonts were constructed with rulers and compasses in order to meet the ideal of clarity and norm. Because of this, they are also much more difficult to read than their predecessors from the Renaissance and Baroque. Justification and central axis were retained as forms of typography. The typographers' task was to choose a suitable font and structure the text. Book decorations were used sparingly. Lavishly illustrated initials gave way to initials in the basic font. At the end of classicism, the first grotesque and Egyptienne typefaces appeared. Another innovation of this era was the establishment of the typographic point system .

The most important type designers of the era were the Italian Giambattista Bodoni , the French die cutter family Didot and the German Justus Erich Walbaum . Bodoni's writings in particular, documented in the Manuale Tipografico published after his death , are considered to be outstanding due to their precision and elegance. Firmin Didot's Didot of the same name, on the other hand, is known as the font of the French Enlightenment because of its slimmed-down, cool, often characterized as cold precision. In addition, the family company Didot dominated French typography with its fonts and designs until well into the 19th century. The Walbaum , the third prototype of the classicist era, on the other hand, is often described as cozy, and negatively as Biedermeier. In Germany, however, it advanced to become the authoritative script of the classical and romantic epoch .

At the beginning of the 19th century, the design features of classicist antiqua typefaces were also transferred to the appearance of the Fraktur , which continued to shape the typographic appearance in Germany. In addition to Walbaum, the printer Johann Friedrich Unger was also involved in this stylistic renewal . Walbaum Fraktur and Unger Fraktur eventually developed into models for other Fraktur designs from the Wilhelmine era , such as the Fette Fraktur or the Wilhelm Klingspor Gotisch , created in 1911 . Even with other fonts such as the cursive scripts that emerged from the chancellery , the classicist influences became increasingly obvious. In the first half of the 19th century, classicist typography tended more and more towards purely formal and increasingly embellished solutions. In terms of style history, the classicist phase of typography finally culminated in the historicism of the Victorian era, which was heavily charged with pomp and pathos .

The era of industrialization (1830 to 1890)

The 19th century brought few fundamental innovations in style. The main innovation was the appearance of serif-reinforced fonts. Forerunners were so-called Egyptienne fonts , which were used increasingly at the beginning of the 19th century. Its name is probably derived from the enthusiasm for the Orient of the Napoleonic era , which in turn was triggered by Napoleon's Egyptian campaign. Serif-reinforced fonts such as Clarendon from 1845, on the other hand, were usually newspaper fonts whose serifs were reinforced so that they did not break out when printing. In terms of style, the serif-reinforced mid-century appeared very robust and otherwise mostly had more or less strong classicistic design features. This changed in the following years: By transferring the design elements serif reinforcement and serif attachment to more and more fonts, an independent intermediate group of quite heterogeneous fonts gradually emerged in the course of the 20th century. Slab serifs or serif- reinforced fonts are now listed as an independent group in most current font classification systems - alongside the other two main groups Serif (traditional Antiqua fonts) and Sans Serif (sans serif sans serif fonts such as Helvetica ).

The 19th century was particularly innovative in terms of technology. Machine manufacturing processes changed both printing and illustration graphics. The illustration of printed matter could be standardized considerably through the lithography technique invented by Alois Senefelder . Another invention was photography , the establishment of which at the end of the century led to the first simple screening and reproduction processes. The gradual emergence of a modern mass society ensured a growing demand for printed products. In book design, this often meant that the book as a mass product was based in its typography on the handicrafts of the Baroque . An abundant equipment with decorative elements testifies to this. In addition to traditional book printing, approaches to a newspaper landscape as well as a broad market for publications, advertising prints and posters of all kinds developed. The challenges had changed: If printing and typography had remained a manageable craft for centuries, they now had to face the challenges of an industrially determined mass society.

Lead and photo typesetting in the 20th century

The roughly 90 years between 1890 and 1980 shape the image of typography up to the present day. The printing trade became an industry , and typography became a part of it too. Both stylistically and technologically, this era was sometimes quite turbulent. The following new developments were decisive:

- The manufacture and use of fonts were increasingly determined by industrial manufacturing methods. The main stages in this process were the invention of the metal typesetting machine by Ottmar Mergenthaler ( Linotype model , 1886) and Tolbert Lanston ( Monotype model , 1887), and photo typesetting a few decades later. Result: The recording and typographical design of the text could increasingly be done using keyboard-controlled mechanisms instead of by hand.

- A subsequent aspect of the industrialization process was the previously unknown number and distribution of new fonts. Whether digital versions by Garamond and Bodoni or new, contemporary typeface designs such as Futura , Times and Helvetica : Almost all of the typefaces currently in use either come from the subsequent computer typesetting era, which continues to this day, or are based on designs from this era. The basis was the development of large type foundries and type manufacturers. The result: Successful typefaces could quickly acquire branded product status - and were thus in turn able to give products or publications an unmistakable “ branding ”.

- In addition to traditional book typography, graphic design developed as a more or less independent division. The interrelationship between these two branches, which was not free of tension, also had a decisive influence on the stylistic development of typography in the 20th century.

Art Nouveau and New Book Art

The modern art styles since Impressionism also found their echo in graphics and typography. Art Nouveau became popular in 1890 . Its floral decorative elements, the curved shapes and the graphic design also inspired the type designers at the turn of the century. A well-known Art Nouveau font was Eckmann , designed by the graphic artist Otto Eckmann ; Moreover, the Art Nouveau influence also expressed in numerous book illustrations and bookplates -designs.

Overall, a return to the roots of book art became increasingly noticeable around the turn of the century. This was initiated by the British typographer, socialist and small press publisher William Morris as well as by the Arts and Crafts Movement, which referred to him . Essentially, this movement initiated three things: a return to the Antiqua models of the Renaissance, clarity and simplicity in book illustration, and manageable manual processes in the creation of printed matter. A direct consequence of the Arts and Crafts movement was the emergence of a small press movement that was more or less committed to Morris' ideals and some of the remnants of which have been carried over to the present day. An established meeting point for this scene in Germany is the Mainz mini press fair , which currently takes place every two years.

Strongly influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement , the New Book Art movement , which began to emerge in the decade before the First World War , was particularly influenced . The young typeface designers of the prewar period, including Fritz Helmuth Ehmcke and Friedrich Wilhelm Kleukens , rejected both the typographical late classicism and the ornamentation of the popular Art Nouveau. The new ideal was a tidy, no-frills book typography that was strongly committed to the ideas of the Renaissance. As trainers, Walter Tiemann in Leipzig, FH Ernst Schneidler in Stuttgart and Rudolf Koch in Offenbach were the main mentors of this type of typography. In book typesetting, it remained decisive until well after the Second World War .

See also: Book Art Movement

Establishment of sans serif fonts

The beginning of the 20th century was also the hour of birth of the last important typeface to date: the sans serif grotesque . Its origins can be traced back to the end of the 18th century, but sans serif fonts have only been used across the board since the advent of advertising . The fact that the new font had a polarizing effect on many contemporaries is demonstrated in particular by the designation “grotesque”, which dates back to the early 19th century. Two early grotesque models were the 1904 Akzidenz Grotesk series produced by the Berlin type foundry Berthold and the American Franklin Gothic by Morris Fuller Benton . Similar to the Antiqua typefaces, different design directions developed over time with the Grotesk as well:

- a school strongly oriented towards the classical theory of forms. In addition to the two fonts mentioned, it mainly includes Helvetica , Arial and Univers . This design style can be observed in its purest form in the last three writings; In terms of time, it overlaps strongly with the temporary dominance of Swiss design concepts in the 1950s and 1960s. The American grotesque, such as Franklin Gothic, is considered a moderate form of this trend .

- a school derived from the Renaissance Antiqua. The main features of this design school are calligraphic, mostly freer design methods and slightly varying line widths. This type of grotesque became popular primarily through Edward Johnston ( Johnston Sans ), the designer of the London Underground signage, and the Gill Sans by Eric Gill , which appeared in the late 1920s. In the long run, this type, also known as “humanistic”, became the most successful and most widely used model.

- a geometric-constructivist school. It had its climax especially in the field of elementary typography in the 1920s. The best- known representative of this direction is the Futura by Paul Renner and the universal typeface by the Bauhaus typographer Herbert Bayer, also known as Bauhaus . Later reminiscences such as the Avant Garde from 1970 played a role above all in the zeitgeist and fashion typography. Geometric construction elements are also often used as style quotations in post-modern fonts.

The new font quickly became popular, especially in advertising. In the further course of the 20th century, sans serifs became more and more popular and are now considered - alongside antiquas (serif fonts) and serif fonts (slab serifs) - as the third basic type in the field of text fonts.

Avant-garde and elementary typography

The new sans serif fonts were used extensively, especially in the context of elementary typography from the mid-1920s. Elementary or New Typography was closely linked to the Bauhaus concepts. Its origins can mainly be traced back to trends in the contemporary avant-garde. The contemporary art movements Expressionism , Dadaism and Russian Constructivism also had a strong influence on typography after the First World War. The influence of Expressionism was particularly noticeable in book design. In some cases it also inspired the work of traditional typeface designers such as the Offenbach School around Rudolf Koch . Dadaism and Constructivism, on the other hand, left their traces above all in graphic art, in printed matter, political calls and finally in poster design. The two graphic artists Kurt Schwitters and John Heartfield should be mentioned here .

The Dutch graphic group De Stijl ( Theo van Doesburg ) and the Bauhaus founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius were also influenced by constructivism . The Bauhaus combined different approaches from architecture, industrial design, art, graphic design and typography into a decidedly modernist approach. The institution has been controversial since its inception. Continuous attacks by the political right led to the move from Weimar to Dessau in 1925 , and finally to resettlement to Berlin in 1932 . The graphic concept of the Bauhaus was significantly influenced by the native Hungarian Lázló Moholy-Nagy and the graphic designers Joost Schmidt , Josef Albers and Herbert Bayer. In the mid-twenties, Bayer designed the universal font later known as Bauhaus .

The New Typography developed into an influential and polarizing current during the 1920s and early 1930s. Essential design elements were sans serif fonts, geometric shapes, the collage-like use of photo elements, layout grids and the propagation of the radical small font , which was also introduced in the Bauhaus publications in 1925. Jan Tschichold advanced to become the spokesman and theoretician of elementary typography ; The 1928 Futura by Paul Renner , which developed from the environment of the New Frankfurt into one of the best-selling typefaces of all time, is also strongly influenced by her design concepts. The intermezzo of typographical modernism was forcibly ended when the National Socialists came to power in 1933. A number of graphic artists and type designers, including Jan Tschichold and Herbert Bayer, went into exile for political and existential reasons. Others were forced to flee due to increasing racist reprisals; still others, such as Paul Renner, had to accept considerable professional restrictions or chose the path of adaptation on their own initiative. In the epoch of the Weimar Republic , the declaration of belonging to a certain typographic school was often associated with the approach of influencing people with the means of their own typography. The Fraktur-Antiqua dispute experienced its first climax in the 1920s.

The conservative era of the thirties

Internationally, the decade of the 1930s was dominated by conservative and moderately modern approaches. New book art had developed into the international standard in book design. In advertising and poster art, on the other hand, the influence of Art Déco was becoming increasingly noticeable. Art Déco took up the decorative and ornamental elements of Art Nouveau and created a design style that was as pleasing as it was sophisticated and modern on the basis of constructive-geometric design elements. His influence was also evident in the field of advertising literature. Some of the fonts from this era that are still in use today are Broadway , Binner and Peignot .

In the Western European countries, the return to typographic traditions mainly led to the development of new text fonts. The best known is the Times . It was created in the early 1930s on the occasion of a relaunch of the British newspaper of the same name. Another well-known font from this era is the Rockwell . In the USA, the arrival of numerous European exiles led to a noticeable modernization of graphic design. Lázló Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937 ; After the Second World War, the pictorial typography inspired by the Bauhaus influenced advertising design. This in turn had a strong impact on Europe through the Swiss design school of the fifties and sixties.

In Germany, the situation was largely shaped by the traditional two-letter font. The dispute between supporters of the Fraktur and supporters of the Latin script went back in principle to the era of the Reformation . Initiatives to adopt the roman script, which is known as the Latin script, presented by MPs from the SPD and the liberal parliamentary groups, repeatedly failed in the Reichstag of the German Empire. The Fraktur, politicized by the political right as German script in the course of the 19th century, was the dominant font until well into the 1930s: after 1928, over half of all book titles published in Germany were printed in Fraktur. The Latin script was mainly used in scientific publications and areas of art and technology. The Gothic script, on the other hand, was found in almost all school and children's books, as well as in classical and popular literature, which often appeared with a very high number of copies. Taken together, the number of books in German print was an estimated 90 percent or even more.

Also ridiculed by political opponents as "bootleg grotesque", broken grotesque fonts with sometimes martial names such as Tannenberg , National or Germany were established in the early thirties . With the so-called “ normal writing decree ” in 1941, the National Socialist regime made an unexpected U-turn. While numerous experts tried in the previous years to prove that only broken fonts were “truly German”, they were suddenly defamed as “Schwabach Jewish letters” in a decree signed by Martin Bormann and the use of Antiqua typefaces made mandatory. The two typography experts and contemporary witnesses Hans Peter Willberg and Albert Kapr consider pragmatic reasons as the most likely possible reasons for this unexpected change: The rulers of the Third Reich needed a traffic script that could also be understood in the parts of Europe they occupied. The fracture proved unsuitable for this task. Nevertheless, due to its prehistory, the Fraktur has not been able to free itself from its right, German nimbus to this day. The result: both in the Federal Republic of Germany and in the GDR, the Antiqua was generally adopted as a traffic font after the Second World War.

Post-war typography and Swiss functionalism

Post-war typography in Germany was initially conservative and dominated by book art. A typographical new beginning took place only gradually. The Darmstadt-based Hermann Zapf ( Palatino , 1948 and Optima , 1964) made a name for itself through innovative but nonetheless classic new fonts ; to mention continue to Georg Trump and Jan Tschichold . Tschichold now lived in Switzerland , where he had become a staunch advocate of traditional book typography. His numerous publications identify him to this day as one of the most important typographers of the 20th century. His 1967 Garamond reinterpretation Sabon is widespread in the book typesetting genre.

In Switzerland in the 1950s a new concept of typography was developed, strongly influenced by the Bauhaus and contemporary industrial design. Its main characteristics, which in many ways claimed scientific character, were typography-dominated designs, generous use of white spaces, geometric layout arrangements, the stringent use of design grids and the use of neutral-looking, factual sans serif fonts. Leading graphic artists and typographers at the Swiss design school were among others. a. Josef Müller-Brockmann , Emil Ruder or Max Bill . The Helvetica from Haas'schen Schriftgiesserei in Basel and Univers by Adrian Frutiger (both 1957) became famous as functionalist fonts . The Univers was created as a counterpart to the Helvetica; Frutiger defined the widths and thicknesses of his font using a number system. In Germany itself, the functionalist typography concepts were largely promoted by the Ulm School of Design (HfG) and its founder Otl Aicher . Aicher, who was best known for his work in the areas of corporate design and the development of pictograms and signage systems , also produced the Rotis font clan , published by AGFA in the late 1980s . The functionalist typography concepts were particularly well received in corporate culture . However, the factual, unadorned design of the Swiss school has called numerous counter-movements on the scene since the sixties - especially from the field of youth and pop culture.

Letters and photo typesetting

The influence of Fluxus , Pop Art and the psychedelic style of the hippie - youth subculture documented especially in the promotional literature of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. In the 1960s, some Art Nouveau and Art Deco fonts experienced a renaissance in poster design. The British company Letraset and the New York-based International Typeface Corporation (ITC) were in charge of the development of fonts for headlines, posters and outdoor advertising . With Herb Lubalin , Tom Carnase and the graphic artist and former jazz musician Ed Benguiat , the ITC brought together the best display font designers of this decade. The fashion and zeitgeist grotesque Avant Garde came from Lubalin and Carnase ; With the designs for ITC Souvenir (1972) and ITC Tiffany (1974), Benguiat supplied two of the most popular advertising fonts of the seventies. The text fonts of this era often had an unusual design note: for example, the Eurostile by Italian Aldo Novarese (1962) or the Antique Olive by French graphic artist and type designer Roger Excoffon (1969). Other well-known font designers in the 1970s and 1980s included a. Milton Glaser with the Glaser Stencil or Seymour Chwast .

An essential prerequisite for the dissemination of new fonts explicitly intended for graphic design was phototypesetting , which from the early 1970s onwards more and more replaced the traditional lead type. The main innovation was that the text components of a printed matter were no longer composed of lead letters or lines, but were obtained using reprographic exposure techniques - similar to photography. Invention and first experiments with the photo typesetting technique were already some decades ago. The photo typesetting machines of the seventies and eighties, however, were increasingly equipped with components from computer technology and thus more and more suitable for volume typesetting. Another invention of the time were rub-off letters, as they were marketed especially by the British company Letraset. The typesetting and typography genres underwent a fundamental change from the mid-1980s onwards with the emergence of desktop publishing (DTP). The so-called DTP revolution of the 1980s and 1990s turned all modes of production within media production inside out and also created the technical foundations in the field of typography that are still valid today.

See also: repro technology

The DTP era

From the mid-eighties, the set of media products shifted increasingly to so-called desktop computers. Initially burdened by numerous teething troubles and limited by a notorious shortage of working memory (RAM), storage space and relatively slow processors, home computers had already become generally established in media production in the mid-1990s. They were characterized by the following innovations:

- visually oriented operating systems ( Mac OS from Apple and Windows ) and mouse-based working methods according to the motto: "What you see is what you get", also called WYSIWYG in DTP technical jargon ,

- Merging of typesetting, graphics and image design, with which the job description of the typesetter increasingly changed to that of today's media designer ,

- the "new media" such as the Internet , with which multimedia applications for fonts and text are becoming increasingly important,

- Comprehensive, generally applicable font formats such as PostScript and TrueType , which completely replaced the proprietary font formats in photo typesetting and subsequently provided an unprecedented wealth of fonts (a further development is the 16-bit and Unicode- based OpenType format ).

First computer fonts

An essential prerequisite for the triumphant advance of desktop publishing was the establishment of special font formats that could be used on desktop computers. In the beginning, bitmap fonts (on raster graphics screens ) and vector fonts (outline fonts or outline fonts on vector graphics screens and for output on pen plotters) were used. The PostScript format developed by the Californian manufacturer Adobe enabled much better scalability than raster fonts. Advantages: The use of the respective font files was only restricted by the operating system used, connected exposure devices were no longer absolutely necessary for the typesetting. Another universally applicable font format was the TrueType format developed by Apple and Microsoft, which is still predominant under Windows and in home office environments today because the fonts are freely scalable and, in contrast to PostScript fonts, only require one file.

The development of new lead fonts and phototypesetting fonts introduced into the new computer font formats PostScript and TrueType changed the scene of the providers from the mid-eighties. Computer companies like Adobe expanded their font libraries in quick succession and marked the twilight of the gods of old, established type foundries. There were also new companies such as the US provider Bitstream or the font distributor FontShop AG, which was co-founded by Erik Spiekermann . URW Type Foundry and the subsidiary Elsner + Flake have established themselves as further labels for quality fonts in Germany . Of the type foundries and photo typesetting providers that were once dominant in the sector, only the internationally operating companies Linotype and Monotype were able to successfully survive the DTP era. Other traditional companies such as the Berlin H. Berthold AG , however, finally closed their doors.

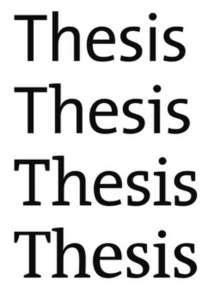

Still, the first decade of desktop publishing brought a number of new text fonts. Stylistically, they were strongly based on the existing basic groups; In addition, they came up with a sometimes quite extensive inventory of different styles. Examples are the Frutiger by Adrian Frutiger, which is in particularly high demand in Germany , the Myriad , the new set antiqua Minion , the Meta and font clans composed of various group variants such as Sans Serif, Serif and Slab Serif, such as Stone by Sumner Stone , Lucida by Charles Bigelow and Kris Holmes , the thesis of Lucas de Groot or the Rotis by Otl Aicher.

Postmodern and Techno

In terms of style, two main influences can be cited for the 1990s: on the one hand, postmodern design approaches in different forms, and on the other hand, the creative input of techno culture . Postmodern designers emphasized the design of fonts and layouts more than before: Instead of a consistent style, the focus was more on the variety of possible style quotations. The British graphic artist and typeface designer Neville Brody represented a graphic direction that was strongly based on the zeitgeist layout and typography . He also derived some known display fonts such as Blur, the Insignia, the Arcadia or FF Harlem. More deconstructivist, visually emphasized concepts that undermine the classic separation between image and text came from the American David Carson and the father of deconstruction design, the Chicago professor Edmund Fella . The Californian typographic magazine Emigre in particular became the center of postmodern influences in early computer typography . The publishers were the Czech-American type designer Zuzana Licko and her partner Rudy Vanderlaans . Her font label Emigre of the same name published a number of avant-garde design fonts, including the well-known Licko fonts Matrix and Triplex , the Template Gothic by Barry Deck and the Remedy by the Swabian graphic artist Frank Heine .

In the typography of the 1990s, the influence of various contemporary youth cultures became more noticeable than before. This development was favored by the new possibilities of the Internet. Downloads and online purchases also made it possible for small, independent labels to sell their fonts. In addition, there was a flood of so-called shareware and freeware fonts that were relatively quickly shared with programs such as B. Fontographer were generated and their technical and design quality for professional media designers are in most cases undisputed. Nonetheless, the acceptance and frequency of use of unconventional fonts have increased significantly since the early 1990s: They have become an indispensable design element, especially in the field of pop culture , and the design of record and CD covers , posters and flyers is now indispensable.

The techno scene provided particularly strong creative input. The big font manufacturers jumped on the train of zeitgeist trend fonts quite early. However, original, unused designs can mainly be found on the websites of small manufacturers. The British Rian Hughes with his label Device Fonts caused a sensation as a designer ; The Dutch designers Erik van Blokland , Jan van Rossum and Max Kisman as well as the strongly retro-style fonts of the US label House Industries are also to be listed .

The gender-specific job description of the type designer has also changed during this decade. Although type designers are still clearly in the minority today, professional women like Zuzana Licko , the type designer Carol Twombly who works for Adobe and is also responsible for the text fonts Myriad and Adobe Caslon , the advertising type designer Cynthia Hollandsworth , Jean Evan , Freda Sack , Kris Holmes (Co-design of Lucida) and the Berlin graphic artist Verena Gerlach have contributed to the fact that the profession of type designer is no longer a purely male domain.

Simplification of classic fonts

In this context, the term “simplification” has nothing to do with the so-called simplified bastard fonts , the “bastarda”. With the advent of Postscript and True-Type fonts, there has been an increasing simplification of classic fonts over the years, such as the sans serif fonts (Futura, Helvetica, Univers, etc.), the serif fonts (Baskerville, Garamond or Times) and an " Anglicisation "Classical Fraktur fonts as" Black Letter "took place; The latter only use the final s as the “ English Fraktur ” and not the long s that is common in classical Fraktur . Furthermore, ligatures such as the ß or umlauts are missing in many computer-generated new creations .

Font clans, OpenType and the Internet

In the case of text fonts, there has been an increasing trend towards large font families across groups since the early 1990s. So-called typeface clans or typeface clans not only cover one basic stylistic type such as antiqua, sans serif or serif, but two, three or even more. The basic idea behind this design concept is the easier mixing of different fonts and thus the easier creation of typographic appearances “from a single source”. Overall solutions of this kind are increasingly in demand, especially among large corporations and media publishers. One example is ARD , which has been using the thesis of the Dutch type designer Lucas de Groot, who lives in Berlin, since the 1990s . Since the 1990s, more and more font families have emerged. Examples are the FF Scala and the FF Nexus by Martin Majoor , the FF Quadraat by Fred Smeijers or the new syntax by Hans Eduard Meier .

Open type

Another current development is the establishment of the OpenType font format based on 16-bit data depth and the Unicode mapping scheme . Unlike conventional PostScript or TrueType fonts, OpenType fonts are not limited to around 200 characters, but can potentially contain thousands of them. Another advantage is that the same font files can be used on any operating system. In addition to the OpenType Standard format, which is the platform for fonts with very different features in terms of drawing technology, there is the OpenType Pro format, which is promoted primarily by the software manufacturer Adobe. With OpenType Pro fonts, the aim is to have a character inventory that covers all the needs of demanding typesetting and also contains the character inventory for setting texts in Central European languages (Polish, Hungarian, Czech, etc.). Some Pro fonts also contain characters to cope with Cyrillic or other character systems.

Monitor and pixel fonts

A current question as early as the 1990s was the development of special fonts for the monitor. On the one hand, medium-specific features such as the comparatively coarse screen resolution must be taken into account. In addition, internationalization, which is also facilitated by the Internet, is becoming increasingly important - a requirement that current operating systems are trying to solve, especially with proprietary 16-bit font formats. A typical example of a modern system font is Lucida Grande under Mac OS X; Another modern font for monitor applications is the Verdana by the American type designer Matthew Carter . A "paradoxical" step back to the beginning of the bitmap fonts made the typography with the pixel fonts , which especially very small for accurate representation of font sizes have been developed on the monitor and found mainly in web application (such. As in Flash animations ). Pixel fonts can usually only be displayed in a certain font size (7, 8, 9 point etc.).

The current status

In this section some additional aspects of the history of typography and the current state of typographic conventions are presented. These include:

- the question of country-specific features in typographical development,

- the current status with regard to the application of typographic rules and

- current attempts at font classification.

Country-specific features

The main historical stages - the emergence of the antiqua up to the 20th century and the more recent developments up to the present day - apply to all countries within the scope of the Latin alphabet. In addition, there are a number of national and local characteristics. Historically the most significant is certainly the different importance of the broken scripts. While they were replaced by antiqua fonts quite early in Italy and France and faded into the background, the writing culture in Germany until the end of the Second World War was characterized by the coexistence of two different fonts.

In addition, each country developed specific national traditions in the creation and use of fonts. Caslon, Baskerville and Gill naturally enjoy a particularly high priority in the British writing tradition; The same applies to the Didot type-maker dynasty in France, the influence of Bodoni on Italian typography and the influence of the Bauhaus concepts in Germany and Switzerland. By and large, the history of Western typography also applies to the United States . The actual founding father of US typography is the print shop owner Benjamin Franklin ; The two typographers and type designers Frederic Goudy and Morris Fuller Benton, who worked at the beginning of the 20th century, are essential for the overall pragmatic and less theoretical typography of the United States . In Latin America and the African countries south of the Sahara, on the other hand, it is only in recent years that independent currents have become increasingly heard.

Current typography conventions

Typography of the 20th century was strongly influenced by traditional book typography (New Book Art) and functionalist design concepts (Bauhaus, Swiss graphics). In the course of the last few decades, different syntheses of these two main directions have become generally established: the natural use of sans serif fonts, a freer approach to mixing and the use of fonts in general, modern layouts and working with design grids are generally accepted. In the area of microtypographic design, on the other hand, conventions from the book typesetting tradition come into play. Overall, they strongly emphasize the aspect of readability. What is striking in current typography is the attention to detail and the use of various typographic special characters - a development that is not insignificantly promoted by the current OpenType format and the Unicode standard. The question of whether the quality of printed matter has got better or worse as a result of technical developments is being asked less and less.

Current attempts at writing classification

The DIN 16518 classification scheme, which dates from 1964, is considered unsatisfactory by most of the specialists, designers and type manufacturers currently involved in typography. A key factor in the current discussion is the question of how rigid or how wide-meshed a font scheme has to be in order to do justice to the ever-increasing variety of fonts. Current approaches are currently:

- Classifications of writers. The cataloging scheme of the Berlin font distributor FontShop AG only subdivides text fonts into the main groups Serif, Slab Serif and Sans Serif. For the remaining fonts, the groups Script (cursive fonts), Display, Blackletter and Pi & Symbol are added. The type manufacturer Linotype is currently offering a similarly coarse subdivision system.

- Dynamic and static fonts according to Willberg. Hans Peter Willberg's classification approach is based on microtypographical investigations and primarily focuses on the appearance of the text line. Dynamically - regardless of whether it is an antiqua, a slab serif or a sans serif font - largely corresponds to humanistic design principles (Renaissance, Baroque), while static, on the other hand, corresponds to classicistic and geometric principles.

- The Beinert matrix by Wolfgang Beinert provides an additional subdivision of the text fonts for the three main groups Serif, Sans Serif and Slab Serif. Other special features are separate main categories for fonts (corporate typography) and screen fonts.

- Form classification according to Vox . After the French typographer Maximilien Vox .

- A Cartesian grid by the typographer Max Bollwage : The scheme presented in the Gutenberg Yearbook 2000 offers a system that is primarily based on the central characteristics of a font. Historical assignments tend to take a back seat. Main groups according to Bollwage are humanistic, classical, free and written forms; The main criteria of each of the five subgroups are the strength and character of the line contrast.

See also

literature

- Phil Baines, Andrew Haslam: Desire for writing . Schmidt, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-87439-593-6 .

- Axel Bertram: The well-tempered alphabet. A cultural story . Faber & Faber, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-936618-38-0 .

- Rainer Falk, Thomas Rahn (ed.): Typography and literature. Stroemfeld, Frankfurt a. M., Basel 2016, ISBN 3-86600-053-7 .

- Friedrich Friedl, Nicolaus Ott, Bernhard Stein: Typography. when who how . Könemann, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-89508-473-5 .

- Albert Kapr: Fonts. History, Anatomy and Beauty of the Latin Letters . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1981. New edition: Philo Verlagsgesellschaft, 2006, ISBN 3-364-00624-5 .

- Albert Kapr: Fraktur. Form and History of the Broken Scriptures . Schmidt, Mainz, ISBN 3-87439-260-0 .

- Manfred Klein, Yvonne Schwemer-Scheddin, Erik Spiekermann: Types & Typographers . Edition Stemmle, Schaffhausen 1991, ISBN 3-7231-0419-3 .

- Claudia Korthaus: Basic course in typography and layout . Galileo-Press, Bonn 2014, ISBN 978-3-8362-2818-3

- Georg Kurt Schauer (Ed.): International book art in the 19th and 20th centuries . Maier, Ravensburg 1969.

- Daniel Sauthoff, Gilmar Wendt, Hans Peter Willberg: Recognizing fonts . Schmidt, Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-87439-418-2 .

- Günter Schuler: The Typo Atlas . Smart Books, Kilchberg (Switzerland) 2000, ISBN 3-908490-28-6 .

- Günter Schuler: bodytypes. Compendium of typesetting: Serif, Sans Serif and Slab Serif . Smart Books, Kilchberg (Switzerland) 2003, ISBN 3-908492-69-6 .

- Hans Peter Willberg: Signpost writing. First aid for dealing with fonts, what fits, what works, what disturbs. Schmidt, Mainz 2001, ISBN 3-87439-569-3 .

- Hans-Jürgen Wolf: History of Typography. Hand and machine typesetting through the centuries . Historia publishing house. Ulm-Wiblingen 1999. ISBN 3-9805533-0-2 .

- Annemarie Willers: "The Art of Writing", Dresden 1959

Web links

- Graphically prepared overview with timeline

- Typography Wiki

- Web portal of the Berlin typographer Wolfgang Beinert ( typolexikon.de )

- Phillip Strahl: A Brief History of Typography . Youtube animation video

- Broadcast with Thomas Maier about the history of the Chaosradio typography

glossary

Note: The glossary only contains definitions of terms for a better understanding of the main article. For more information, see the corresponding links in the article.

- Antiqua: originally: script of antiquity. Formerly a general term for Latin scripts; currently usually a term for serif fonts.

- Font: Name for digitally available font file.

- Broken fonts: Generic term for those fonts whose style goes back to the Gothic of the High Middle Ages. The broken fonts (also: blackletters) include: Textura, Rotunda, Schwabacher and Fraktur.

- Grotesque: sans serif fonts (also: sans serif antiquas). Often referred to as sans serif in the current font classification.

- Basic strokes and hairstrokes: Vertical, diagonal and horizontal stroke elements of letters can vary greatly in fonts. This is especially true for Antiqua typefaces. In sans serif fonts, they usually only vary slightly. The character trait resulting from different line widths is also known as line contrast.

- Capital letters, capital letters: capital letters. Uppercase Alphabet: Uppercase Alphabet

- Lowercase letters : lower case letters. Lowercase Alphabet: Lowercase Alphabet

- Serifs: feet, roofs and extensions for Antiqua fonts. Depending on the presence and characteristics of serifs, the three main text font groups are also referred to as serif, sans serif and slab serif.

- Slab Serif: modern term for serif antiquas.

Individual evidence

- ^ Bruckmann's Handbook of Scripture