Jim Thorpe

| Jim Thorpe | |

|---|---|

|

Position (s): Back |

Jersey numbers: 31, 21, 2, 1 |

| born on May 22, 1887 in Prague , Oklahoma | |

| died on March 28, 1953 in Lomita , California | |

| Career information | |

| Active : 1915 - 1928 | |

| College : Carlisle | |

| Teams | |

|

player

Trainer

|

|

| Career statistics | |

| Stats at NFL.com | |

| Stats at pro-football-reference.com | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

|

|

| Pro Football Hall of Fame | |

| College Football Hall of Fame | |

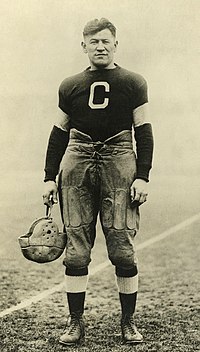

James Francis "Jim" Thorpe (* probably on May 22, 1887 near Prague in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma ) as Wa-Tho-Huck ; † March 28, 1953 in Lomita , California ) was a successful American athlete in various Sports. He won Olympic gold medals in pentathlon and decathlon , was a professional player in American football and baseball, and also played basketball . His Olympic medals were stripped of him because he had played in a semi-professional baseball league for two years before the 1912 Olympic Games and thus violated amateur regulations.

After losing his amateur status, Thorpe played from 1913 to 1919 in Major League Baseball , including with the New York Giants . In 1915 he also joined the Canton Bulldogs , who in 1920 were a founding member of the National Football League . He himself headed the predecessor of this professional league for two years as nominal president. In total, Thorpe played for seven different football teams by 1928. He also founded a basketball team composed entirely of Indians . He was active as a professional athlete up to the age of 41, the end of his career coincides with the global economic crisis . Thorpe tried his hand at acting, but increasingly struggled to make a living. He suffered from alcoholism and spent the last years of his life in poverty. In 1983, thirty years after his death, the International Olympic Committee rehabilitated him .

Due to the fact that Thorpe practiced several sports at the highest level, he is considered one of the most outstanding athletes in modern sport. The Associated Press calls him the best athlete of the first half of the 20th century. As one of the very first players, he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963. A small town in Pennsylvania is named after him.

biography

Childhood and youth

Information about the circumstances of Thorpe's birth, his full name, and his ethnic origin vary depending on the sources. It is known that he was born in Indian territory , but his birth certificate can not be found. According to several matching biographies, it is most likely that he was born on May 22, 1887 near the town of Prague in what is now the state of Oklahoma . Jacobus Franciscus Thorpe is the name on his baptism certificate from the Roman Catholic Church . Thorpe himself wrote in a 1943 note to the local newspaper The Shawnee News-Star that he was born on May 28, 1888, “near and south of Bellemont in Pottawatomie County, on the banks of the North Fork River ... I hope that will be the inquiries clarify my place of birth. ”Bellemont was a small town on the border of Pottawatomie Counties and Lincoln Counties that no longer exists.

His father, Hiram Thorpe, had an Irish father and a mother from the Sauk - Fox Indian tribe . His mother, Charlotte Vieux, had a French father and a Potawatomi mother. Thorpe grew up according to the traditions of the Sauk-Fox, his Indian name was Wa-Tho-Huck ("Light Path"). As usual with the Sauk-Fox, it was named after an event during his birth. In his case, it was the sun that shone on the path to the hut in which he was born. Both parents belonged to the Roman Catholic denomination, and Jim Thorpe himself followed this his entire life.

He and his twin brother Charles attended elementary school in Stroud , Oklahoma, at a facility of the Sauk Fox Indian Agency. Charles helped him with school material until he died of pneumonia at the age of nine . Jim Thorpe coped poorly with his brother's death and skipped school several times. The father then sent him to the Haskell Institute in Lawrence , Kansas to prevent further truancy. When the mother died of a miscarriage two years later, Thorpe suffered from depression . After several arguments with his father, he left home to work on a horse ranch.

In 1904 the then 16-year-old Thorpe returned to his father and decided to attend the Carlisle Indian Industrial School , a renowned boarding school for Indians in Carlise , Pennsylvania . It was there that Glenn “Pop” Warner, one of the most influential coaches in the early stages of American football , discovered his athletic talent. When his father died in the same year of gangrene that he contracted in a hunting accident, Thorpe dropped out of school again. He worked on a farm for a while and then returned to Carlisle.

Start of sports career

Legend has it that Thorpe's sports career began in Carlisle in 1907. He is said to have passed the athletics facility and in normal street clothes beat the high jumpers of the school with a spontaneous jump over 1.75 m. Whether this is true cannot be established, but his first recorded results in athletics actually date back to 1907. Thorpe also played American football, baseball, and lacrosse . He also participated in courses for standard dances , winning in 1912 the school dance championship.

In 1911 Thorpe was in the national public eye for the first time. As a running back , defensive back , kicker and punter , he scored all field goals for the football team at his school in a surprising 18:15 win over Harvard University (one of the best teams in the NCAA ) . The following year he was instrumental in ensuring that Carlisle won the national college championship. In twelve games he scored 25 touchdowns and 198 points.

A special game was the 27-6 victory over the United States Military Academy team when Thorpe scored a touchdown after a run of 97 yards (89 m). The future US President Dwight D. Eisenhower was one of his opponents at the time. He said of Thorpe in a 1961 speech: “Here and there there are some people who are extremely talented. My memories lead me to Jim Thorpe. He never trained in his life and he could do everything better than any other football player I have ever seen. " (Here and there, there are some people who are supremely endowed. My memory goes back to Jim Thorpe. He never practiced in his life, and he could do anything better than any other football player I ever saw.)

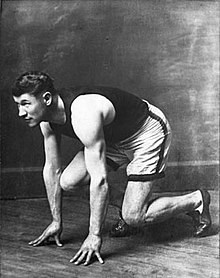

In 1911 and 1912 Thorpe was elected to the All-Star Team. Football was and remained his favorite sport and he only occasionally took part in athletics competitions. Even so, it was athletics that would later bring him the greatest fame. In the spring of 1912 he began to train for the Olympic Games in Stockholm . He had previously limited his efforts to jumps, hurdles and shot put, but now added pole vault, javelin throw, discus throw, hammer throw and weight throwing to the training program.

Olympic Games 1912

In Stockholm two new all-around disciplines were on the program, the pentathlon and the decathlon . A pentathlon based on the ancient model had been played at the unofficial Olympic Intermediate Games in 1906 , while the more modern variant consisted of a long jump , javelin , 200 meter run , discus throw and 1,500 meter run . The decathlon was a whole new Olympic discipline. However, it had been practiced in the United States since the 1880s and one version had been part of the program for the 1904 Olympic Games . The new Olympic version was slightly different from the American one. Both competitions were tailored to Thorpe's versatility. Thorpe competed in the Celtic Park in New York for the Trials, the American qualification. In the pentathlon, he won three sub-disciplines. Because the number of participants was too low, the preliminary round in the decathlon had to be canceled and he would therefore play his first and - as it turned out later - only decathlon in the Swedish capital. The American pentathlon and decathlon team also included the later IOC President Avery Brundage .

Thorpe's competition schedule at the Olympics was packed. In addition to the decathlon and the pentathlon, he also took part in the individual competitions in the long jump and high jump . He made his first appearance on July 7th in the pentathlon: He was the outstanding athlete and won four of the five sub-disciplines; in the javelin throw he reached third place, although he had never practiced this discipline before 1912. The competition was rated primarily according to the number of place numbers, but there were also points for the performance achieved in the individual disciplines. Thorpe received 4041,530 points, over 400 more than the second-placed Norwegian Ferdinand Bie . On the same day that he won the gold medal in the pentathlon, Thorpe qualified for the high jump final, finishing in fourth place. On July 12th, he was seventh in the long jump.

Thorpe's last assignment was the decathlon from July 13th to 15th, which was expected to be a tough duel with the Swede Hugo Wieslander . But even Wieslander was not a yardstick for Thorpe and scored almost 700 points less (Thorpe himself achieved 8412.955 points). The American was at least fourth best in all ten disciplines. Thorpe's performance was also remarkable because shortly before the competition his shoes were stolen. He had to compete with two mismatched replacement shoes, one of which he found in a trash can. In addition to athletics, Thorpe also played two baseball games to present the sport, which is still little known in Europe; the American team consisted entirely of track and field athletes.

As was customary at the time, the medals were presented to the athletes on the last day during the closing ceremony. In addition to the two gold medals, Thorpe also received two challenge cups, which had been donated by the Swedish King Gustav V and the Russian Tsar Nicholas II for the winner of the decathlon and the pentathlon. When handing over the trophy King Gustav supposed to have said: "You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world." (You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world.) Thorpe should then with "Thanks, King" (Thanks , King) have responded. Whether this exchange actually took place is doubtful, especially since contemporary sources are lacking. This anecdote first appeared in a newspaper in 1948 and in a book four years later.

Thorpe's successes had not gone unnoticed in his homeland and when he returned he was the main attraction of a confetti parade on Broadway in New York . He later wrote about it: "I heard people shouting my name and I couldn't believe that a guy can have so many friends." (I heard people yelling my name, and I couldn't realize how one fellow could have so many friends .)

Loss of amateur status

At the beginning of the 20th century, strict amateur regulations were in place for athletes who took part in the Olympic Games. Athletes who had received prize money for competitions, were sports teachers or had previously competed against professionals were not considered amateurs and were not eligible to participate in Olympic competitions. There were various back doors, but these presupposed that the responsible association was committed to its athletes. But that's exactly what the AAU , led by Avery Brundage , even decathletes and inferior to Thorpe, did not.

In late January 1913, the Worcester Telegram newspaper of Worcester , Massachusetts published an article alleging that Thorpe was a professional baseball player. Various other newspapers picked up this story. Thorpe had actually played in the Eastern Carolina League for Rocky Mount , North Carolina in 1909 and 1910 , with the amount of money received for it fluctuating between two dollars per game and 35 dollars a week. College players were often under contract with professional teams in the summer season, but in contrast to Thorpe they used pseudonyms.

While the public did not seem particularly interested in Thorpe's past, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), and especially its secretary James E. Sullivan, took the matter very seriously. Thorpe wrote a letter to Sullivan in which he admitted that he was a professional baseball player: “I hope that I will be partially excused by the fact that I was simply an Indian boy and did not know all about such things. I didn't know I was doing wrong, because I was doing something I knew other college students did too, except that they didn't use their own names… ” (I hope I will be partly excused by the fact that I was simply an Indian schoolboy and did not know all about such things. In fact, I did not know that I was doing wrong, because I was doing what I knew several other college men had done, except that they did not use their own names ... )

His letter did not help: The AAU decided to revoke Thorpe's amateur status retrospectively and asked the IOC to follow suit. That same year, the IOC unanimously decided to revoke Jim Thorpe's Olympic titles, medals and awards and declared him a professional. Thorpe had actually played for money, but his disqualification did not comply with the rules. The regulations for the 1912 Olympic Games stated that all protests had to be made no later than thirty days after the closing ceremony. The first newspaper reports appeared six months after the Stockholm Games. There is evidence that Thorpe's professional status was known even before the Games. But then the AAU is said to have deliberately ignored this fact until it was confronted with it in 1913. The only positive thing for Thorpe about the affair was that soon after the newspaper reports came out, he received offers from several Major League Baseball (MLB) teams .

Baseball career

| Jim Thorpe | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Outfielder | |

| Born: May 22, 1887 Prague , Oklahoma |

|

| Died on: March 28, 1953 Lomita , California |

|

| Suggested: right | Threw: right |

| Debut in Major League Baseball | |

| April 14, 1913 with the New York Giants | |

| Last MLB assignment | |

| September 25, 1919 with the Boston Braves | |

| Batting average | , 252 |

| Home runs | 7th |

| Hits | 176 |

| RBI | 82 |

| Teams | |

|

|

|

The last minor league team that Thorpe was under contract was disbanded in 1910. He was thus one of the few free agents at the time and was free to decide which MLB team he wanted to play for. In January 1913, he refused a permanent starting place with the St. Louis Browns and signed with the New York Giants , even if he was there only in the reserve for the time being. Immediately after losing the World Series in October 1913, the Giants went on a world tour with the Chicago White Sox . Wherever the team played, whether in the US or abroad, Thorpe was undoubtedly the star of the event. It attracted media attention and high audience revenues. The highlights of the world tour included audiences with Pope Pius X and Abbas II , the last Khedive of Egypt ; in London he played in front of 20,000 spectators, including King George V.

For three years Thorpe was sporadically used as an outfielder with the Giants . In 1916 he played a season with the Milwaukee Brewers in a minor league and then returned to the Giants. During the early stages of the 1917 season, he was sold to the Cincinnati Reds . In the "double no-hitter " between Fred Toney of the Reds and Hippo Vaughn of the Chicago Cubs , Thorpe managed the decisive run in the tenth inning . Almost at the end of the season, it was sold back to the Giants. In 1918 he continued to play sporadically for this team before moving to the Boston Braves for one season on May 21, 1919 in exchange for Pat Ragan . During his professional career, which lasted until September 25, 1919, he scored 91 runs, 82 run batted in and a batting average of .252 in a total of 289 games. Until 1922 Thorpe played for various teams in the minor leagues.

American football and basketball

During his time as a professional baseball player, Thorpe was also active as a football player. In 1913 he was a team member of the Pine Village Pros from Warren County , Indiana . In 1915 he signed a contract with the Canton Bulldogs of Canton , Ohio . He then received $ 250 per game, a huge amount for the time. Before Thorpe's signing, the Bulldogs had an average of 1,200 viewers per game, and over 8,000 were seen on his debut against the Massillon Tigers . The team was successful and won the regional championship in 1916, 1917 and 1919. The decisive game of the 1919 season decided Thorpe from the five-yard line with a wind-assisted punt of 95 yards.

In 1920 the Canton Bulldogs were among the 14 founding members of the American Professional Football Association (APFA), which two years later became the National Football League (NFL). Thorpe was nominally the first president of APFA, but continued to play for and train the Bulldogs. After a year he was replaced by Joseph Carr as president. From 1921 to 1923 Thorpe played for the Oorang Indians from La Rue , Ohio. It was a team composed entirely of Indians. It was not particularly successful and lost more games than it won - the record was 3-6 in the 1922 season and 1:10 in the 1923 season. Thorpe's own performance, however, was so good that the Green Bay Press-Gazette put him in in 1923 elected the first NFL All-Star Team (officially recognized by the NFL in 1931). From 1920 to 1928 he was under contract with six different professional teams, but never won a championship title. At the age of 41 and after 52 NFL games, he resigned.

Until 2005, most biographers did not know that Thorpe had also played basketball - until they found a ticket hidden in an old book with his name printed on it. From 1926 he was the main attraction of the World-Famous Indians ("the world-famous Indians") from La Rue, who played in several states until 1928. This period of his life is not well documented, although some local newspapers reported about it.

Marriages and offspring

Thorpe was married three times and had eight children. In 1913 he married Iva M. Miller, whom he had met while at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. They bought a house in Yale , Oklahoma, and lived in it until 1923. It is now a national register of historic places and houses a museum. The couple had four children named James Jr. (died at the age of two), Gail, Charlotte and Frances. Miller filed for divorce in 1925, citing malicious departure as the reason.

In 1926 Thorpe Freeda married Verona Kirkpatrick. She worked for the manager of the football team he was playing for at the time. The second marriage resulted in four sons: Phillip, William, Richard and John (called Jack). After being married for 15 years, Kirkpatrick divorced Thorpe. After all, he was married to Patricia Gladys Askew for the third time from 1945, with whom he lived until his death.

Further life and death

After the end of his sports career, Thorpe struggled to support his family. He didn't get along well with work outside of sports and never stayed long in one job. Especially during the Great Depression he kept afloat with odd jobs, including as an extra in Hollywood . He was usually seen as an Indian chief in western films . In the 1932 comedy Always Kickin ' , Thorpe had a larger speaking role, portraying himself as a coach teaching young football players to dropkicks. A year earlier he had sold the rights to his life story to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for $ 1,500 . In 1940 Thorpe played a football referee in the movie Knute Rockne, All American . In the 1950 movie Wagon Master , he starred as a Navajo tribal member.

The rights to his life story passed to Warner Bros. after a few years . This film studio produced the film Jim Thorpe - All-American, directed by Michael Curtiz in 1951 . Thorpe was played by Burt Lancaster . Rumors circulated that Thorpe had received no money. In fact, Warner Bros. paid him $ 15,000, while the studio's marketing director added an additional $ 2,500 for a pension. The film contained archive footage of the 1912 and 1932 Olympics, in one scene Thorpe had a cameo as a football coach.

Thorpe also worked on construction sites and as a doorman and security guard. In 1945 he joined the merchant navy for a short time . Towards the end of his life he was chronically ill with alcohol . He ran out of money and became impoverished. When he had to be hospitalized in 1951 because of a cancerous tumor on his lips, he was accepted as a social case. At a press conference, his wife, Patricia Askew, asked for help and said, “We're broke ... Jim has nothing but his name and memories. He spent money on his own people and gave it away. It was often taken advantage of. ”On March 28, 1953, Thorpe suffered a third heart attack while having lunch with his wife in his trailer in Lomita . He was able to be resuscitated, but shortly thereafter passed out and died at the age of 64.

Victim of racism

Thorpe's father and mother were both of semi-European descent, but he himself grew up according to Indian traditions. Its successes came at a time of massive racial inequality in the United States. It has often been claimed that his medals were revoked because of his ethnicity. While this is difficult to prove, public opinion at the time largely reflected this view. When Thorpe won his gold medals, not all Indians were recognized as US citizens ; citizenship was not granted to everyone until 1924.

During Thorpe's time at Carlisle Industrial School, the student ethnicity was used for marketing purposes. The football team was named Indians . A 1911 photo of Thorpe and the football team highlighted the ethnic differences between the competing athletes; the inscription on the most important match ball of the season reads: "1911, Indians 18, Harvard 15". In addition, the school and journalists often portrayed sporting encounters as conflicts between Indians and whites. Headlines such as “Indians scalp army 27-6” or “Jim Thorpe is running amok” were deliberate play on words based on stereotypes about the ethnic background of the Carlisle players based. The first headline about Thorpe in the New York Times read: "Indian Thorpe at the Olympics: Redskin from Carlisle Going for a Place on the American Team." Throughout his life, other newspapers and sports journalists described his accomplishments in a similar racial context.

legacy

Olympic rehabilitation

Over the years there have been various attempts to recognize Thorpe's Olympic achievements, but American sports officials, above all IOC President Avery Brundage , blocked each of them. Brundage once said: “Ignorance is no excuse.” Most tenaciously for Thorpe's rehabilitation, the author Robert Wheeler and his wife Florence Ridlon campaigned. Wheeler was able to prove in a biography published in 1975 that Thorpe's disqualification had been unlawful. The couple persuaded the Amateur Athletic Union and the United States Olympic Committee to overturn their resolution and restore Thorpe's pre-1913 amateur status.

Wheeler and Ridlon set up a foundation called the Jim Thorpe Foundation in 1982 and managed to get US Congress support . With this backing and with evidence that Thorpe's disqualification had occurred after the 30-day period had expired and thus violated the provisions of the time, they submitted the case to the IOC for reassessment. On October 13, 1982, the IOC Executive Council approved Thorpe's rehabilitation. At the same time she declared him the joint Olympic champion with Ferdinand Bie and Hugo Wieslander , whereby both had always emphasized that Thorpe was the only real winner. Two of Thorpe's children, Gail and William, were presented with replicas of the 1912 gold medals from IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch in a ceremony held on January 18, 1983 . The originals were exhibited in museums, but were then stolen and have disappeared to this day.

Honors

Journalists received Thorpe's services with great acclaim both during his lifetime and since his death. In a 1950 Associated Press (AP) poll of 400 sports journalists and reporters, he was named the Most Outstanding Male Athlete of the First Half of the 20th Century. Another poll conducted by AP that same year named him the most outstanding football player of the same period. Also, a 1999 AP poll found Thorpe to be the third best athlete of the century, behind Babe Ruth and Michael Jordan . The television channel ESPN placed him in seventh place in the list of the best North American athletes.

In 1963, Jim Thorpe received the National Football League's highest honor , induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame , as one of 17 players in the first round of awards. A larger than life statue commemorates him at the Pro Football Hall of Fame exhibit in Canton, Ohio. He is also a member of college football , the American Olympic teams, and track and field athletes. In 2018 he was one of the first twelve to be honored by the National Native American Hall of Fame.

Authorized by Joint Senate Resolution 73 , President Richard Nixon declared April 16, 1973 Jim Thorpe Day to promote its national recognition. In 1986 the Jim Thorpe Award was presented for the first time ; he goes to the best defensive back in college football. On February 3, 1998, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp to commemorate Thorpe. An international competition between decathletes and heptathletes from the United States and Germany, introduced in 2007, bears the name Thorpe Cup in his honor .

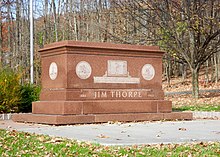

Jim Thorpe (Pennsylvania)

Thorpe's body was railroaded from California to Shawnee , Oklahoma. The funeral service took place there in the Catholic St. Benedict Church, the burial in the Fairview cemetery. Friends and relatives started a donation campaign in order to be able to erect a memorial in his honor in the city's athletics facility. Local officials sought support from the state legislature, but Governor Johnston Murray vetoed a bill that included $ 25,000 in funding. In the meantime, without the knowledge of the rest of the family, the widow had the body exhumed and transferred to Pennsylvania. She had learned that the small towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk in Carbon County were looking for new tourist sources of income. The widow then signed a contract with the local authorities: Thorpe's remains were for sale and the residents of both cities decided in a referendum to merge and name the new community Jim Thorpe , although the namesake himself was probably never there. The monument on the outskirts of Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania includes his tomb, two statues depicting him in athletic poses and several memorial plaques.

Jim Thorpe's daughters subsequently gave their consent and visited the place named after their father several times. His son Jack, however, filed a federal lawsuit in June 2010 for seeking to bring his father's remains back to Oklahoma. Based on the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), he argued that the only legal burial site was on the reservation in Oklahoma, next to the graves of his father and his sisters and brothers, about a mile from the place of his birth. He alleged that the agreement between his stepmother and Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania city authorities was made against the wishes of other family members. Before the case could be heard in the first instance, Jack Thorpe died at the age of 73 in February 2011.

A judge at the United States District Court ruled in April 2013 that the monument in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania was equivalent to a museum within the meaning of NAGPRA and that the remains would therefore have to be returned if a direct descendant so wished. The lawyer for Thorpe's living sons Richard and William, who had disagreed with Jack's action, then announced an appeal. The United States Court of Appeals of the third district overturned the judgment of the lower court on October 23, 2014 and ruled in favor of the city of Jim Thorpe. According to the jurisprudence of the state of Pennsylvania, there must be clear and valid reasons for a new reburial, which is not the case here. On October 5, 2015, the United States Supreme Court declined to hear the case, effectively closing the litigation.

literature

- Kate Buford: Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe . University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2010, ISBN 978-0-8032-4089-6 .

- Ceane O'Hanlon-Lincoln: Chronicles: A Vivid Collection of Fayette County, Pennsylvania Histories . Mechling Bookbindery, Butler (Pennsylvania) 2006, ISBN 0-9760563-4-8 .

- Robert W. Wheeler: Jim Thorpe, World's Greatest Athlete . University of Oklahoma Press, Oklahoma City 1979, ISBN 0-8061-1745-1 .

- Glen Jeansome: A Time of Paradox: America Since 1890 . Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham (Maryland) 2006, ISBN 0-7425-3377-8 .

- David S. Neft, Richard M. Cohen, Rick Korch: The Complete History of Professional Football from 1892 to the Present . St. Martin's Press, New York City 1994, ISBN 0-312-11435-4 .

- Kay Schaffer, Sidonie Smith: The Olympics at the Millennium: Power, Politics and the Games . Rutger University Press, New Brunswick (New Jersey) 2000, ISBN 0-8135-2820-8 .

Web links

- Jim Thorpe in the database of Sports-Reference (English; archived from the original )

- Profile on the side of the Pro Football Hall of Fame

- Profile on the College Football Hall of Fame page

- Player information and statistics Baseball Reference (English)

- Short biography on the IOC website

- Jim Thorpe in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b O'Hanlon-Keane: Chronicles. P. 129.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Jim Thorpe Is Dead On West Coast at 64. The New York Times , March 29, 1953, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Wheeler: Jim Thorpe, World's Greatest Athlete. P. 291.

- ^ "Ghost" town of Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma. Rootsweb, archived from the original on October 26, 2011 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ America at Large: Bizarre coda to Olympian Jim Thorpe's epic life. The Irish Times , August 3, 2016, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Jim Thorpe Leaps To Fame On Carlisle Athletic Field. The Washington Post , December 15, 1912; accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ O'Hanlon-Lincoln: Chronicles. P. 131.

- ↑ a b Jim Thorpe - Olympic Hero and Native American. Olympics30, archived from the original on June 21, 2011 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e Greg Botelho: Roller-coaster life of Indian icon, sports' first star. CNN , July 14, 2004, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Jim Thorpe cruelly treated by authorities. Sports Illustrated , August 8, 2004; archived from the original on May 15, 2009 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Jean Some: A Time of Paradox. P. 60.

- ↑ Sam Richmond, Jim Thorpe leads Carlisle to upset of Harvard in 1911. National Collegiate Athletic Association , August 8, 2004, archived from the original on November 11, 2015 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Thorpe, Jim. USOC , 2004, archived from the original on September 30, 2007 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Buford: Native American Son. Pp. 112-114.

- ↑ Buford: Native American Son. Pp. 127–128.

- ^ Sally Jenkins: Why Are Jim Thorpe's Olympic Records Still Not Recognized? Smithsonian Magazine, July 2012, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Jim Thorpe. Sports Reference, 2016, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Robert Dodge: Which Chosen People? Manifest Destiny Meets the Sioux: As Seen by Frank Fiske, Frontier Photographer . Algora Publishing, New York City 2013, ISBN 978-1-62894-029-9 , pp. 145 .

- ↑ Buford: Native American Son. Pp. 158-161.

- ^ Sports in Brief. In: Amarillo Daily News, March 13, 1948, p. 2.

- ^ John Durant, Otto Bettmann: Pictorial History of American Sports, from Colonial Times to the Present. AS Barnes, 1952, p. 143.

- ↑ a b c Ron Flatter: Thorpe preceded Deion, Bo. ESPN , accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Buford: Native American Son. P. 121.

- ↑ Arnd Krüger : Whose Amateurism? The international standardization of the 'amateur' in the later 19th and early 20th centuries . In: Angela Teja, Arnd Krüger & James Riordan (eds.): Sport e Culture - Sport and Cultures. Atti del IX Congreso internazionale dell 'European Committee for Sport History (CESH) . Ed. di Convento, Calopezzati 2005, ISBN 88-7862-003-3 , p. 294-307 .

- ↑ Jim Thorpe Admits He Is Professional, and Retires from Athletics. In: The Washington Post , Jan. 28, 1913, p. 8.

- ↑ a b Dave Anderson: Jim Thorpe's Family Feud. The New York Times , February 7, 1983, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Schaffer, Smith: The Olympics at the Millennium. P. 40.

- ^ Buford: Native American Son. P. 167.

- ↑ Thorpe, Jim. United States Olympic Committee , 2004, archived from the original on September 30, 2007 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Buford: Native American Son. P. 162.

- ^ M. Jacque Rogge, Michael Johnson, Matt Rendell: The Olympics: Athens to Athens 1896-2004 . Sterling Publishing, New York City 2004, ISBN 0-297-84382-6 , pp. 60 .

- ^ Thorpe is to Play Ball with Giants. The New York Times , February 13, 1913, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Sox and Giants on World's Tour. The New York Times , July 27, 1913, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Tom Clavin, The Inside Story of Baseball's Grand World Tour of 1914. Smithsonian Institution , March 21, 2014, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Jim Thorpe's Speed Big Hit In AA The Janesville Daily Gazette, July 10, 1916, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Arthur Daley: Baseball's Ten Greatest Moments. The New York Times , April 17, 1949, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Jim Thorpe. Baseball Reference, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Buford: Native American Son. P. 232.

- ^ NFL History by Decade 1911-1920. National Football League , accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Neft, Cohen, Korch: The Complete History of Professional Football from 1892 to the Present. P. 18.

- ^ Neft, Cohen, Korch: The Complete History of Professional Football from 1892 to the Present. P. 20.

- ^ Neft, Cohen, Korch: The Complete History of Professional Football from 1892 to the Present. P. 34.

- ^ Neft, Cohen, Korch: The Complete History of Professional Football from 1892 to the Present. P. 40.

- ^ Neft, Cohen, Korch: The Complete History of Professional Football from 1892 to the Present. P. 41.

- ↑ Jim Thorpe. Pro Football Reference, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ History Detectives - Episode 10, 2005: Jim Thorpe Ticket, Jamestown, New York. (PDF, 115 kB) Public Broadcasting Service , 2005, accessed on April 1, 2019 (English).

- ↑ Buford: Native American Son. Pp. 253-254.

- ^ National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Registration Form. (563 kB) National Register of Historic Places , 1971, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ List of marriages, divorces, births, and deaths. Time , April 6, 1925, archived from the original on September 30, 2007 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Athlete Thorpe's 2nd wife, Freeda, dies at 101. Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 7, 2007, archived from the original on October 17, 2012 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Buford: Native American Son. P. 366.

- ^ A b O'Hanlon-Lincoln: Chronicles: A Vivid Collection of Fayette County, Pennsylvania Histories. Pp. 144-145.

- ^ Michael Hilger: Native Americans in the Movies: Portrayals from Silent Films to the Present . Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham (Maryland) 2015, ISBN 978-1-4422-4002-5 , pp. 324 .

- ^ Buford: Native American Son. P. 356.

- ^ Charles Thorp: 8 Olympic Movies That Medal. Men's Journal, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Jean Some: A Time of Paradox: America Since 1890 S. 61st

- ↑ Thorpe Has Cancerous Growth Removed From Lip in Hospital at Philadelphia . In: The New York Times , November 10, 1951.

- ^ Schaffer, Smith: The Olympics at the Millennium. P. 50.

- ↑ Kenneth Lincoln, Al Logan Slagle: The Good Red Road: Passages into Native America . University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln (Nebraska) 1997, ISBN 0-8032-7974-4 , pp. 282 .

- ↑ Jim Thorpe Photo Collection. (PDF, 63 kB) historicalsociety.com, accessed on April 1, 2019 (English).

- ^ John Bloom: There is a Madness in the Air: The 1926 Haskell Homecoming and Popular Representations of Sports in Federal and Indian Boarding Schools . In: Elizabeth S. Bird (Ed.): Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture . Westview Press, Boulder (Colorado) 1996, ISBN 0-8133-2667-2 , pp. 97 .

- ^ Indian Thorpe in Olympiad; Redskin from Carlisle Will Strive for Place on American Team. The New York Times , April 28, 1912; accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Jim Thorpe cruelly treated by authorities. Sports Illustrated , archived from the original on November 14, 2007 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ David Wethe, Michael Whiteley: Legends lunches begin this fall with Bob Lilly. Dallas Business Journal, July 21, 2002, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ O'Hanlon-Keane: Chronicles. P. 132.

- ^ Claire Hickey: Jim Thorpe: Greatest American Athlete of the 20th Century. Communities Digital News, August 27, 2016, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Top 100 athletes of the 20th century. USA Today , December 21, 1999, archived from the original on March 12, 2008 ; accessed on April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Top N. American athletes of the century. ESPN , accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Hall of Famers by Year of Enshrinement. Pro Football Hall of Fame , accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Debra Krol: National Native American Hall of Fame names first twelve historic inductees. Indian Country Today, October 22, 2018, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Proclamation 4209 — Jim Thorpe Day. The American Presidency Project, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Buford: Native American Son. Pp. 367-369.

- ^ Wheeler: Jim Thorpe, World's Greatest Athlete. Pp. 228-229.

- ↑ O'Hanlon-Keane: Chronicles. P. 148.

- ↑ Thom Loverro: Jim Thorpe sleeps on - for now - in town where everyone knows his name. The Guardian , August 2, 2013, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Jim Thorpe's son sues town of Jim Thorpe over location of athlete's remains. The Patriot-News, June 24, 2010, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Al Zagofsky: Jim Thorpe's son Jack dies. tnonline.com, February 24, 2011, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Judge Sides With Sons About Legendary Athlete Jim Thorpe's Remains. KOTV-DT, April 21, 2013, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ John Thorpe (et al) v. Borough of Jim Thorpe, No. 13-2246. (PDF, 260 kB) United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, October 23, 2014, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ John Branch: Supreme Court Declines to Hear Jim Thorpe Appeal. The New York Times , October 5, 2015, accessed April 1, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Thorpe, Jim |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wa-Tho-Huck (maiden name); Thorpe, James Franciscus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American athlete |

| DATE OF BIRTH | uncertain: May 22, 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prague (Oklahoma) |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 28, 1953 |

| Place of death | Lomita |