Georg Philipp Telemann

Georg Philipp Telemann (born March 14, jul. / 24. March 1681 greg. In Magdeburg , † 25. June 1767 in Hamburg ) was a German composer of the Baroque . He shaped the music world of the first half of the 18th century significantly through new impulses, both in composition and in musical perception.

Georg Philipp Telemann spent his youth in Hildesheim from 1697 . Here he received significant funding, which decisively shaped his musical development. In the four school years at the Andreanum grammar school he learned several instruments and it was here that he composed Singing and Sounding Geography . After that he received numerous commissions for other compositions.

Later he learned the music largely in self-study . He had his first major compositional successes while studying law in Leipzig , where he founded an amateur orchestra, directed opera performances and rose to be music director of the then university church. After brief employment at the courts of Sorau and Eisenach , Telemann was appointed city music director and conductor of two churches in Frankfurt am Main in 1712 , and he also began self-publishing works. From 1721 he occupied one of the most prestigious musical offices in Germany as Cantor Johannei and Director Musices of the city of Hamburg, and a little later he took over the management of the opera. Here, too, he was still in contact with foreign courts and organized regular public concerts for the urban upper class. With an eight-month stay in Paris in 1737/38 Telemann finally achieved international fame.

Telemann's musical legacy is extraordinarily extensive and encompasses all musical genres that were common at the time . Typical for Telemann are vocal melodies, imaginatively used timbres, especially in the late work also unusual harmonic effects. The instrumental works are often strongly influenced by French and Italian, and occasionally by Polish folklore. In the course of the changed cultural-historical ideal, Telemann's work was viewed critically in the 19th century. Systematic research into the complete works did not begin until the second half of the 20th century and is ongoing due to its large size.

Life

Childhood and youth

Telemann came from an educated family; his father and a number of other ancestors had studied theology. Apart from Telemann's great-grandfather on his father's side, who was temporarily cantor , none of his family had any direct connection to music. His father, Pastor Heinrich Telemann, died on January 17, 1685, only 39 years old. The mother, Johanna Maria Haltmeier, was also born in a pastor's house and was four years older than her husband. Of the six children, only the youngest son, Georg Philipp, and Heinrich Matthias Telemann, born in 1672, reached adulthood. This brother died in 1746 as an Evangelical Lutheran pastor in Wormstedt near Apolda .

Georg Philipp attended high school in the old town and the school at Magdeburg Cathedral , where he received lessons in Latin , rhetoric , dialectics and German poetry . The young student Telemann performed particularly well in Latin and Greek. His self-composed German, French and Latin verses, which he reproduced in his later autobiography, testify to his comprehensive general education. Telemann also mastered Italian and English well into old age.

Since public concerts were still unknown in Magdeburg at the time, the secular music performed in the school complemented the church music. In particular, the old town school, which had concert music instruments and regularly organized performances, was of great importance for the town's music maintenance. Even in the smaller private schools that Telemann attended, he learned various instruments such as the violin , recorder , cyther and clavier in self-study . He showed considerable musical talent and began composing his first pieces at the age of ten - often in secret and on borrowed instruments. He owed his first sound musical experience to his cantor Benedikt Christiani. After just a few weeks of singing lessons, the then ten-year-old Telemann was in a position to represent the cantor who preferred composing rather than teaching in the senior classes. Apart from a two-week piano instruction, he received no further music lessons. His zeal was dampened by his mother, widowed since 1685, who disapproved of his occupation with music because she considered the music class to be inferior.

At the age of only twelve Telemann composed his first opera , Sigismundus , based on a libretto by Christian Heinrich Postel . In order to dissuade Georg Philipp from a musical career, his mother and relatives confiscated all of his instruments and sent him to school in Zellerfeld at the end of 1693 or beginning of 1694 . She probably did not know that the local superintendent Caspar Calvör occupied himself intensively with music in his writings and promoted Telemann. Calvör had attended the University of Helmstedt with Telemann's father. He encouraged Telemann to take up music again, but not to neglect school either. Almost every week Telemann composed motets for the church choir . He also wrote arias and occasional music that he presented to the town piper.

In 1697 Telemann became a student at the Andreanum grammar school in Hildesheim . Under the direction of the Director Johann Christoph Losius he perfected his musical training and learned - again, mostly as an autodidact - organ , violin , viola da gamba , flute , oboe , shawm , double bass and bass trombone . He also composed vocal works for school theater. He received further composition commissions for the church service in St. Godehardi Monastery from the Jesuit church music director of the city, Father Crispus.

Telemann was also influenced by the musical life in Hanover and Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel , where he came into contact with French and Italian instrumental music. The experience gained at this time was to shape large parts of his later work. He also got to know the Italian-influenced styles of Rosenmüller , Corelli , Caldara and Steffani during secret music lessons .

Years of study in Leipzig

In 1701 Telemann finished his education and enrolled at the University of Leipzig . Under pressure from his mother, he resolved to study law as planned and no longer bother with music. At least that's what he affirmed in his autobiography; Nevertheless, the choice of the city of Leipzig , which was considered the bourgeois metropolis of modern music, does not seem to have been accidental. On the way to Leipzig Telemann stopped in Halle to meet Georg Friedrich Handel , who was then sixteen . With him he established a friendship that would last his entire life. Telemann wrote that he initially kept his musical ambitions a secret from his fellow students. Allegedly, however, Telemann's music-loving roommate found, thanks to a (probably fictitious) chance, a composition under his hand luggage, which he had performed on the following Sunday in the St. Thomas Church. Then Telemann was commissioned by the mayor to compose two cantatas per month for the church.

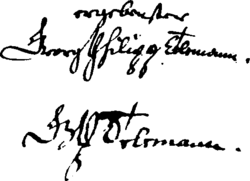

|

Telemann's signature (1714 and 1757) |

Only one year after joining the University, he founded the musical student, a 40-member amateur orchestra ( Collegium Musicum ), gave even public concerts, and which in the newly consecrated Neukirche occurred. In contrast to similar student institutions of this type, the Collegium remained in existence after Telemann's departure and was continued under his name. Under the direction of Johann Sebastian Bach , from 1729 to 1739, the "Telemannische" Collegium Musicum performed in Café Zimmermann with concerts of works by Bach and other contemporary composers who had a great influence on the city's musical life.

In the same year Telemann directed performances of the opera house , in which many members of the Collegium also took part and whose main composer he remained until it closed. At the performances he played the figured bass and occasionally sang. Confused by Telemann's growing reputation, the official city music director Johann Kuhnau accused him of having exerted too much influence on sacred music with his secular works, and refused to allow his choristers to participate in opera performances. In 1704 Telemann was hired as music director after a successful application by the Paulinerkirche , the then university church of the city. However , he gave the associated organist position to students.

Telemann made two trips to Berlin from Leipzig . In 1704 he received an offer from Count Erdmann II von Promnitz to succeed Wolfgang Caspar Printz as Kapellmeister at the court of Sorau in Niederlausitz - it is unknown why he drew the count's attention to himself. The city, which valued the new compositional style, then offered Telemann the Thomaskantorat and the successor to Kuhnau. It is possible that the tensions that developed between Kuhnau and Telemann prompted the latter to leave Leipzig early.

Sorau and Eisenach

In June 1705 Telemann began his work in Sorau. The count was a great admirer of French music and saw in Telemann a worthy successor to the Versailles music school, which was shaped by Lully and Campra , of whose compositions he brought back a few copies on a trip to France and which Telemann was now studying. In Sorau Telemann met Erdmann Neumeister , whose texts he later set to music and whom he was to see again in Hamburg . On trips to Krakow and Pless he learned to appreciate the Polish and Moravian folklore, as it was probably performed in taverns and at public events.

In 1706 Telemann left Sorau, which was threatened by the invasion of the Swedish army, and went to Eisenach , probably on the recommendation of Count Promnitz, who was related to the Saxon ducal families . There he became concertmaster and cantor at the court of Duke Johann Wilhelm in December 1708 and founded an orchestra . He often made music together with Pantaleon Hebenstreit . Telemann also met the music theorist and organist Wolfgang Caspar Printz as well as Johann Bernhard and Johann Sebastian Bach. In Eisenach he composed concerts for various ensembles, around 60 to 70 cantatas as well as serenades , church music and “ operettas ” for festive occasions. He usually wrote the text for this himself. There were also around four or five years of cantatas for the church service. As a baritone he was involved in the performance of his own cantatas.

In October 1709 Telemann married Amalie Luise Juliane Eberlin, a lady-in-waiting of the Countess von Promnitz. Shortly before, he was appointed secretary by the Duke - a high distinction at the time. Telemann's wife, a daughter of the composer Daniel Eberlin , died in January 1711 of childbed fever while giving birth to their first daughter .

Frankfurt am Main

Perhaps because he was looking for new challenges, perhaps to be independent from the nobility, Telemann applied in Frankfurt am Main . There, in February 1712, he was appointed municipal music director and conductor of the Barfüßer Church and a little later also of the Katharinenkirche . He completed the cantatas he began in Eisenach and composed five more. He was also responsible for teaching some private students. As in Leipzig, Telemann was not satisfied with these obligations in Frankfurt. In 1713 he took over the organization of the weekly concerts as well as various administrative tasks for the elegant lounge society Zum Frauenstein in the Braunfels house on the Liebfrauenberg , where he also lived. In addition, the Eisenach court appointed Telemann as Kapellmeister "by default", so that he kept his title, but only delivered cantatas and occasional music to the court and the churches. This happened until 1731.

During his time in Frankfurt Telemann composed, in addition to the cantatas, oratorios , orchestral and chamber music , much of which has been published, as well as music for political ceremonies and wedding serenades. However, he did not find an opportunity to publish operas, although he continued to write for the Leipzig Opera.

In 1714 Telemann married 16-year-old Maria Catharina Textor (1697–1775), the daughter of a Ratskornschreiber . From the following year he published his first printed works himself. On a trip to Gotha in 1716 Telemann was offered a position as Kapellmeister by Duke Friedrich . The Duke not only promised him that he would retain his position as Kapellmeister for the Eisenach court, but also had the Duke of Saxe-Weimar promise Telemann another position as Kapellmeister. With that Telemann would have become, as it were, chief conductor of all Saxon-Thuringian courts.

A letter to the Frankfurt council in which Telemann politely issued an ultimatum regarding his salary proves his diplomatic skill. He stayed in Frankfurt and got a 100 guilders salary increase . Together with his income from the Frauenstein Society and fees for occasional compositions, Telemann's annual income amounted to 1,600 guilders, making him one of the best paid in Frankfurt.

During a visit to Dresden in 1719 he met Handel again and dedicated a collection of violin concertos to the violin virtuoso Pisendel . Telemann continued to write works for Frankfurt every three years until 1757 after he had left the city.

Started in Hamburg

In 1721 Telemann accepted the offer to succeed Joachim Gerstenbüttel as Cantor Johannei and Director of Music for the City of Hamburg. Probably Barthold Heinrich Brockes and Erdmann Neumeister suggested his name. Telemann had come into contact with the Hanseatic city earlier, however, as he had already participated in one or two operas for the opera on Gänsemarkt . As the city's musical director, Telemann worked, among other things, at the five large Protestant Lutheran city churches - with the exception of the cathedral , for which Johann Mattheson was responsible. Telemann's solemn inauguration took place on October 16. It was only here that his 46-year-long main creative phase began with the opportunity to compose and perform works of all forms . The obvious translation of Telemann's official title as “Cantor” is misleading in that the actual cantor's work at the Johanneum was limited to occasional cantatas and the musical equipment of the other school acts.

In his new position Telemann committed himself to composing two cantatas per week and one passion per year, but in later years he used earlier works for his cantatas. In addition, he composed numerous pieces of music for private and public occasions, such as memorial days and weddings. The office of Cantoris Johannei was also associated with an activity as a music teacher at the Johanneum; Telemann did not, however, fulfill his obligations to extra-musical lessons himself. He also rebuilt the Collegium musicum, which was founded by Matthias Weckmann in 1660 but has since ceased to perform . He personally sold the tickets.

In his new hometown, Telemann did not let the connections to Thuringia be severed at first. He served the Duke of Saxony-Eisenach as an agent from 1725 and reported to the Eisenacher Hof about news from Hamburg. Not until 1730 did he hand over the position to the doctor Christian Ernst Endter .

In Hamburg Telemann resumed his work as a publisher. To save costs, he stabbed himself either the copper plates, or he used a 1699 by William Pearson developed and until then in use in England alone process in which he with pencil mirrored the notes on a sheet of pewter chronicled. The printing plate was then scraped and peeled off from another. Telemann managed nine to ten records a day. By 1740 he had self-published 46 music works, which he sold to booksellers in several German cities as well as in Amsterdam and London . You could also order scores from the composer himself ; Until 1739, catalogs were regularly updated to keep music lovers informed. Among the works are, for example, Twelve Fantasies for viola da gamba solo , which he printed in 1735.

However, Telemann had more trouble in the Hanseatic city than he had expected. The council printer refused to allow Telemann to participate in the sales of the cantatas and Passions booklets. Telemann was not to emerge victorious until 1757 from the lengthy legal dispute that followed. In addition, the senior elders complained when Telemann wanted to perform some cantatas in an elegant inn in 1722 (meaning the tree house in the Hamburg harbor). Together with the inadequate pay and his apartment that was too small, these incidents led him to apply for the position of Thomaskantor in Leipzig after Kuhnau's death . He was unanimously elected from among the six applicants, whereupon he submitted a resignation on September 3, 1722, which, in contrast to his letter to the Frankfurt Council, appears quite serious. Since the Hamburg council now increased his salary by 400 marks in Luebisch , Telemann turned down the position as Thomaskantor a little later and stayed in Hamburg. His total annual income thus amounted to around 4,000 marks in Luebisch.

New start in Hamburg

Only now did Telemann's activity in Hamburg flourish in all areas. In the same year he took over the management of the opera for an annual salary of 300 thalers. He continued this office until the house was closed in 1738. Most of the 25 or so opera works from this period have been lost. In 1723, Telemann also took on a position as a musical director for the court of the Margrave of Bayreuth . From time to time he delivered instrumental music there as well as an opera annually. Telemann's concerts mostly took place in the "Drillhaus", the parade hall of the Hamburg vigilante, and were reserved for the higher classes due to the high admission price. Telemann delivered almost exclusively his own compositions for his performances - apart from those in the opera house.

In 1728 Telemann founded the first German music magazine together with Johann Valentin Görner , which also contained contributions by different musicians. The faithful music master was supposed to encourage music-making at home and appeared every two weeks. In addition to Telemann and Görner, eleven other contemporary musicians, including Keizer , Bonporti and Zelenka , contributed to the magazine with their compositions. Further collections for teaching purposes followed.

In twelve years Telemann's wife Maria Catharina gave birth to nine children, two of whom died. With an almost permanent pregnancy, she had to take care of a growing household with up to twelve people, including Georg Philipp Telemann's daughter from his first marriage and three other people (presumably a maid, a private tutor and a student of Telemann) as well as Telemann himself. Ten years after the birth of the The couple separated from their last child after Telemann discovered that his wife had lost 5,000 Reichstaler (15,000 marks in Luebisch) in a game of chance . It is believed that the divorce was pronounced because of Maria Catharina's adultery. She returned to Frankfurt in 1735, while rumors spread in Hamburg that she had died. Without Telemann's knowledge, some Hamburg citizens had a fundraising campaign organized to save him from bankruptcy. The fact that Telemann nevertheless managed to satisfy his most urgent creditors mainly out of his own pocket and that he made several spa stays in Bad Pyrmont - obviously approved by the city - shows that he was a wealthy man.

Trip to Paris and later years

Following a long-cherished wish, Telemann visited Paris in autumn 1737 after being invited by a group of musicians there ( Forqueray , Guignon and Blavet ). During his absence Telemann was represented by Johann Adolf Scheibe . Seven of Telemann's works were already reprinted in Paris. After a four-month stay, the king granted him an exclusive right to his publications for 20 years, which was intended to protect against pirated prints . With several performances of his works Telemann finally achieved international fame. He was the first German composer to introduce himself at the Concert Spirituel , which gave public concerts. In May 1738 Telemann, whose reputation had also been increased in Germany by the trip, returned to Hamburg. In 1739 he was accepted into the Corresponding Society of Musical Sciences , founded by Lorenz Mizler , which dealt with questions of music theory.

In a newspaper advertisement published in October 1740, Telemann offered the printing plates of 44 self-published works for sale because he now wanted to concentrate on the publication of textbooks. Comparatively few compositions have survived from the following 15 years. Telemann increasingly used unusual instrument combinations and novel harmonic effects. Outside of his duties, he devoted himself to collecting rare flowers.

From the period from 1755 three large oratorios and other sacred and secular works have survived. Telemann's eyesight deteriorated noticeably, and he also suffered from leg problems. More and more often he called on his grandson Georg Michael, who was also composing, to help him with his writing. Telemann's humor and innovative strength did not suffer from his tiredness. He composed his last work, a Markus Passion , in 1767. On June 25th, at the age of 86, Telemann died of complications from pneumonia . He was buried in the cemetery of the St. John's Monastery , where the Rathausmarkt is located today . There is a memorial plaque to the left of the entrance to the town hall to remind him of him. His successor in office was his godson, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach .

More details have survived about Telemann's life and work than about many of his contemporary colleagues. In addition to around 100 letters, there are also poems, forewords and various articles by the composer. The most important text sources, regardless of their errors, are his three autobiographies, which he wrote at the request of the music scholars Mattheson (1718 and 1740) and Johann Gottfried Walther (1729). The periods of life in Sorau and Eisenach and after the publication of the last autobiography are barely described in the text sources from Telemann himself, but can be roughly reconstructed through indirect references in various other documents.

Work and creation

influence

Several contemporary musicians - including Telemann's student Johann Christoph Graupner , Johann Georg Pisendel and Johann David Heinichen - took up elements of Telemann's work. Other composers like Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel soon emulated them. Other students from his time in Hamburg, to whom Telemann did not teach the instrumental craft, but rather "stylistics" are Jacob Wilhelm Lustig , Johann Hövet , Christoph Nichelmann , Jacob Schuback , Johann Christoph Schmügel , Caspar Daniel Krohn and Georg Michael Telemann. Telemann's Polish influences inspired Carl Heinrich Graun to imitate them; Johann Friedrich Agricola learned from Telemann's works at a young age. Even Johann Friedrich Fasch , Johann Joachim Quantz , and Johann Bernhard Bach mentioned Telemann explicitly as a model for some of their works. Notes from his own hand with which he added Telemann's manuscripts show that Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach studied and performed many of his compositions. Telemann's lively friendship with Handel was not only expressed in the fact that Telemann performed several of Handel's stage works - some with his own interludes - in Hamburg, but also in the fact that in later years Handel often used Telemann themes in his own compositions. Johann Sebastian Bach made copies of several of Telemann's cantatas and introduced his son Wilhelm Friedemann to his music in a piano book specially designed for him. The music book created by Leopold Mozart for Wolfgang Amadeus contains eleven minuets and a piano fantasy by Telemann. Both the piano style of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart are sometimes reminiscent of Telemann's spelling.

In addition to his achievements as a composer, Telemann had an influence on the bourgeois attitude towards music. Telemann was the founder of a dynamic Hamburg concert life by enabling regular public performances outside of any aristocratic or ecclesiastical framework.

Works

Audio sample: Concert suite in D major TWV 55: D6 for viola da gamba, strings and figured bass

|

With over 3,600 works, Telemann is one of the most productive composers in music history. This large scope is partly due to his fluid way of working, partly to a very long creative phase at the age of 75. Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg gave an impression of Telemann's way of working. He reported that when he was Kapellmeister at the Eisenacher Hofe, Telemann had only been given three hours to write a cantata due to the imminent arrival of a distinguished visitor. The court poet wrote the text, and Telemann wrote the score at the same time, usually finishing the line before the poet. After a little over an hour the piece was finished.

Telemann's legacy includes all genres that were widespread in his time . However, many compositions are lost. Only a few works have survived from Telemann's early days; the majority of the surviving pieces date from Frankfurt and Hamburg. The work is listed in the Telemann works directory (TWV, 1984–1999) by Martin Ruhnke , which includes the Telemann vocal works directory (TVWV, 1982–1983) by Werner Menke .

Telemann demonstrated flexibility by composing according to the changing fashions of his time as well as according to the music of different nations. In his main creative phase, he turned to the sensitive style , which, in terms of art history, is more closely related to the Rococo than the Baroque and built a bridge to the Viennese classicism ; he often combined this gallant style with contrapuntal elements.

At the center of Telemann's creative principle is a vocal ideal melody . He himself repeatedly emphasized the fundamental importance of this compositional element; Mattheson also characterized Telemann during his lifetime as a composer of beautiful melodies.

In harmony, Telemann penetrated into areas of sound that were unfamiliar at the time. He made deliberate use of chromatics and enharmonics , often using shifts , unusual (excessive and diminished) intervals, and altered chords . The expressive dissonances emerge particularly clearly in his late work . The reliable use of major / minor parallel tones and leading tone change sounds goes back in part to Jean-Philippe Rameau . In the sensitive style, the upper part, accompanied by chords, was of great importance. Telemann therefore considered pronounced polyphony to be out of date and only used it where it seemed expedient to him.

In contrast to many of his colleagues, Telemann did not play a virtuoso musical instrument, but was familiar with a large number and mastered all the common ones. The insight he gained into the different effects of different timbres explains his treatment of the instrumentation as an essential compositional element. Telemann probably valued the transverse flute and oboe most, especially the oboe d'amore . Telemann, however, rarely used the violoncello outside of its figured bass function . Occasionally, as in an aria from the St. Luke Passion from 1744, he prescribed scordatura . Telemann showed no interest in compositions with particularly difficult or fast instrumental playing; he also wrote textbooks with a deliberately low level of technical difficulty.

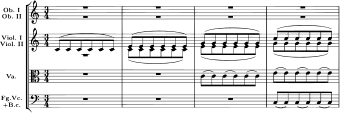

| Example of tone painting in Telemann's music (from the water overture in C major for 2 recorders, piccolo recorder, transverse flute, bassoon, strings and figured bass, TWV 55: C3). At the beginning of the 7th movement, which is titled The Storming Aeolus , the louder wind is implemented with successive instruments: |

In addition to the musical implementation of moods of the soul , which was widespread in the Baroque and especially in the sensitive style , Telemann often operated meticulously worked out tone painting . In vocal works he used painting figures, coloratura and word repetitions to underline text passages . In both secular and sacred vocal works, Telemann attached great importance to declamation and musical interpretation of words, especially in recitatives .

Since the literary currents of the Age of Enlightenment influenced Telemann's intellectual orientation, poetry is of particular importance in his musical work. The texts for the vocal works were partly written by himself, partly by the most famous German writers of his time, including Brockes , Hagedorn , König , Klopstock , Neumeister and others. Telemann gave the lyricists his expectations of suitable texts and their internal structure. Occasionally he made subsequent changes to the libretti according to his ideas.

To specify the character of a piece of music accurately, but rather because of its affiliation with the poet Association Teutschübende society , sat Telemann - 100 years before Robert Schumann - for using German lecture and expression names (such as "kindly", "innocent." or "daring"), but without having found imitators.

Instrumental works

Telemann's instrumental music includes around 1,000 (of which 126 have been preserved) orchestral suites as well as symphonies , concerts, violin solos, sonatas , duets , trio sonatas , quartets , piano and organ music .

The instrumental works often have strong influences from various national styles; this style is sometimes referred to as "mixed tastes". Some pieces are entirely written in the Italian or French style. The latter exerted a particularly great influence on Telemann and can be found in lively, fugitive movements , dance suites and French overtures . The tone painting is also partly of French origin.

| Example of Eastern European influences in Telemann's music (from the Concerto Polon in G major for 2 violins, viola and figured bass, TWV 43: G7). The second movement, Allegro, is based on Moravian music:

|

| The third sentence, headed Largo , is a mazurka :

|

Telemann was the first German composer to integrate elements of Polish folk music on a large scale. In contrast to other composers such as Heinrich Albert , he did not limit himself to familiar elements and dance forms, but shaped both orchestral and chamber music with Slavic melodies and rhythms . The latter is expressed in syncopation and frequent tempo changes. At times, albeit less often, Telemann included folkloric elements from other peoples such as Spanish in his works.

Telemann contributed to the emancipation of certain instruments. He wrote the first major solo concert for viola and used this instrument for the first time in chamber music. Unusual for the time was a composition ( Concert à neuf parties ), in which two double basses were used. He also composed - without naming it that way - the first string quartet . Simultaneously with and independently of Johann Sebastian Bach, Telemann developed a type of sonata in which the harpsichord no longer appeared as a continuo , but as a solo instrument. In his Nouveaux Quatuors , Telemann had the cello performed on an equal footing with other instruments for the first time in music history . Often his instrumental works show an unusual guidance of the melody parts; In some pieces, for example, as an alternative to the recorder, he also provided a violoncello or bassoon played two octaves lower .

In some instrumental works, the humor expressed in tone painting plays a major role. The final movement "L'Espérance du Mississippi" of the La Bourse overture, for example, with its ups and downs, alluded to the crash at the Paris stock exchange in 1720. Another example is the concert Die Relinge , which musically implements the love game of a frog couple.

Telemann's most popular instrumental works today include those published in the Getreuen Music-Meister and Essercizii Musici (1739/40), as well as the Wassermusiken Hamburger Ebb 'und Fluth (1723) and the Alster Overture , the Tafelmusik (1733) and the Nouveaux Quatuors ("Paris Quartet", 1737). In Telemann's time, the music collections Singe, Spiel- und Fig. Bass exercises (1733) and Melodische Frühstunden (1735) were also well known. In 1730 he published his almost general evangelical-musical songbook , which contains over 2000 hymn melodies in various variants and was intended for organists.

Sacred vocal works

Telemann's 1,750 church cantatas represent almost half of his entire estate. In addition, he wrote 16 masses , 23 psalm settings , over 40 passions, 6 oratorios as well as motets and other sacred works.

Telemann's cantatas break away from the older type, which only set chorales and unchanged biblical passages to music. Earlier than Johann Sebastian Bach and to a completely different extent, Telemann adhered to the form developed by Erdmann Neumeister , in which an introductory Bible verse (dictum) or chorale recitatives , arias and possibly ariosi follow and usually lead to a final chorale or the repetition of the opening chorus. As a rule Telemann wrote solo arias, duets comparatively rarely; there are only individual examples of solo dzettas and quartets.

In addition to four-part choirs, there are also examples of three or five-part choirs, rarely double choirs. As in instrumental music, Telemann prefers fugal sections to fully worked fugues. However, the permutation fugue is represented quite numerous.

Drama and detailed tone painting determine Telemann's oratorios. He uses a variety of forms of expression such as repeated recitatives, frequent use of instruments to underline moods and situations, as well as short concertante phrases . The choirs kick in vehemently and confidently, sometimes in unison . The harmony is usually simpler, but more vivid and tailored to the respective situation than in the older baroque style.

The Brockes Passion (1716), the Blessed Consideration (1722), the Death of Jesus (1755), the Thunder Ode (1756), Das were among the most popular sacred works by Telemann at that time - measured by the verifiable performances and preserved copies of the sources Liberated Israel (1759), The Day of Judgment (Written by Christian Wilhelm Alers ) (1762) and The Messiah (1759). In order to meet the requirements of the very numerous smaller churches as well as the teaching purposes for domestic use, Telemann also published cantata collections with chamber music instrumentation, such as Der harmonische Gottesdienst (1725/26; continued 1731/32).

Telemann also wrote numerous funeral music for high-ranking personalities of his time - for example for August the Strong ( Immortal Nachruhm Friederich Augusts , erroneously also Serenata eroica , 1733), George II of Great Britain (1760), the Roman-German Emperor Charles VI. (1740, lost), Karl VII. (1745) and Franz I (1765, lost), nine more for various Hamburg mayors (including the so-called Schwanengesang for Garlieb Sillem , 1733), two for the pastor couple Elers and the Cantata that cannot be dated, but is perhaps the best-known, but you, Daniel, go there and seven more, some of which have only survived in fragments or in the textbook.

Secular vocal works

Telemann's secular vocal works can be divided into operas, large-scale celebratory music for official purposes, cantatas commissioned privately, and cantatas in which he set dramatic, lyrical or humorous texts to music (“Oden”, “Canon”, “Songs”).

Most of the traditional operas turn to the comic genre. Romain Rolland described Telemann as the composer who made the Opéra comique more popular in Germany.

In contrast to Handel, who limited himself almost exclusively to solo arias, Telemann made use of extremely diverse stylistic devices in his operas. These include differently crafted recitatives, da capo arias , dance motifs, singspiel-like arias, arie di bravura and voices from bass to castrato . Telemann consistently portrayed characters and situations with coordinated melodies, motifs and instrumentation; Here too he made imaginative use of various picturesque figures.

The formerly most popular and now some of the 50 operas that have been rediscovered include The patient Socrates (1720), Sieg der Schönheit or Gensericus (1722), The Newfangled Lover Damon (1724), Pimpinone or The Unequal Marriage (1725) and Emma and Eginhard (1728). The opera Germanicus was long lost except for a few arias; Arias from a collection could be assigned to her a few years ago (2005?) And have since been performed and recorded.

The festival music includes the Hamburg Admiralty Music and the 12 Captain's Music, 9 of which have been preserved in full and 3 in part. These works are characterized by musical splendor and particularly vocal melodies.

Telemann's last secular compositions show a high degree of drama and unusual harmony; the cantatas Ino (1765) and Der May - Eine Musicalische Idylle (around 1761), but also the late sacred work The Death of Jesus, are reminiscent of the music of Christoph Willibald Gluck because of their extreme emotions . The secular cantata Trauer-Music of an art -experienced canary bird ("Canary cantata") is one of his most famous compositions. The so-called “schoolmaster cantata” ( the schoolmaster in the singing school ), which was considered a work by Telemann for a long time, actually comes from Christoph Ludwig Fehre .

In his songs Telemann took up the work of Adam Krieger and developed it further in terms of text and melody. The melodies are kept simple and often divided into irregular periods . Telemann's songs represent the most important link between the songwriting of the 17th century and the Berlin Liederschule.

Music theoretical works

In his later creative phase Telemann planned several music-theoretical treatises, including one on the recitative (1733) and a theoretical-practical treatise on composing (1735). None of these writings has survived, so it must be assumed that they were either lost or were discarded again by Telemann.

In 1739 Telemann published the description of the Augenorgel , an instrument designed by the mathematician and Jesuit father Louis-Bertrand Castel , which Telemann visited during his trip to Paris. There is also a tradition of a mood system that Telemann was working on a month before his death and which apparently was based on the work of Johann Adolph Scheibe . There were a number of disputes within the Corresponding Society of Musical Sciences about this New System, which was presented in Mizler's Musical Library , mainly because this description was incomprehensible from a music-theoretical point of view. Telemann had suggested dividing the octave into 55 micro-intervals of equal size. This division is relatively complicated with the associated mathematical task. Only Georg Andreas Sorge succeeded in his work detailed and clear instruction to rational calculation , Telemann's system based on logarithms to describe accurately. In contrast to other contemporaries, Telemann was not interested in solving such questions because , in contrast to the older musical thinking, the representatives of the gallant style rejected the study of musical mathematics .

Reception history

In the entire history of European art music , the reputation of no other musician has been subject to such radical change as that of Georg Philipp Telemann.

While Telemann enjoyed a great reputation during his lifetime, which also radiated beyond national borders, the esteem faded just a few years after his death. His recognition reached a low point during the Romantic period , when the mere criticism of the work gave way to an unfounded defamation that also affected his person. Musicologists of the 20th century, initially hesitantly, gave more room to assessments based on work analysis and finally initiated a rediscovery of Telemann, which is accompanied by sporadic criticism.

Fame in lifetime

In addition to the prestigious positions and offers from courtly and urban surroundings, sources from artistic and popular circles also testify to Telemann's high, steadily growing reputation. While Telemann was already known far beyond the city limits in Frankfurt, his fame reached its peak in Hamburg. In addition to the fact that he pushed new, popular musical developments, his business acumen and the audacity he showed towards high-ranking people had contributed to his unparalleled career.

The fact that Telemann was a European celebrity is shown, for example, by the order lists for his table music and his Nouveaux Quatuors , in which names from France, Italy, Denmark, Switzerland, Holland, Latvia, Spain and Norway as well as Handel (from England) are listed. Invitations and composition commissions from Denmark, England, the Baltic States and France also prove his international reputation. As an offer from Saint Petersburg to build a court orchestra from 1729 shows, the court of the Russian tsar was also interested in Telemann's talent. Copies and pirated prints were made of Telemann's most popular works everywhere for performance and study purposes.

Shortly after Telemann took office in Hamburg, Johann Mattheson, who published regularly as an “art judge”, reported that “so far, as a result of the great skill and hard work that befell him, spiritual music has been extremely important, and with very good progress well, as well as private concerts, to animate anew [...]; so one has recently begun to experience almost the same happiness in the local operas ”.

In addition to Telemann's expressiveness and melodic ingenuity, his internationally influenced work was also valued. Johann Scheibe claimed that Johann Sebastian Bach's works were “by no means of such emphasis, conviction and reasonable thinking [... as those of Telemann and Graun ...] The reasonable fire of a Telemann made this foreign music genre known and popular in Germany too [...] This clever one Man has very often made good use of it in his church affairs, and through him we have felt the beauty and grace of French music with no little pleasure ”. Also Mizler , Agricola and Quantz praised Telemann's use of foreign influences.

During his life in Hamburg, after Handel had emigrated to England, Telemann was considered the most famous composer in the German-speaking world. His sacred music was particularly valued, not only in his places of work, but also in many other north, central and south German communities, sometimes also abroad. The music critic Jakob Adlung wrote in 1758 that there was hardly a German church in which Telemann's cantatas were not performed. Some church cantatas that were ascribed to Johann Sebastian Bach in the Bach works directory have since been identified as works by Telemann, such as the cantata BWV 141 “That is certainly true” and BWV 160 “I know that my redeemer lives”. - Friedrich Wilhelm Zachariä described Telemann in a comparison with Bach as the “father of sacred music” . After some unsuccessful initial resistance, the “theatrical” style of the church composer also met with general approval.

One of the critically viewed aspects of Telemann's work was the musical implementation of impressions of nature, which Mattheson disapproved of. In contrast to the criticism of tone painting that began after Telemann's death, Mattheson was primarily concerned with preserving music as a human form of expression from the description of "unmusical" nature. The unusual harmony was received differently, but was generally accepted as a means of underlining the expression. The comedy and lack of “shamelessness” (Mattheson) of Telemann's operas were partially criticized, as was the mixture of German and Italian texts that was common at the time.

Change in perception of music

The prevailing esteem during Telemann's lifetime did not last long after his death. Just a few years later, criticism of his work was mounting. The reason for this change lay in the transition from the Baroque to a time of Sturm und Drang and the beginning of the Viennese Classical period with the associated change in fashion. The task of music was no longer “storytelling”, but rather the expression of subjective feelings. In addition, the connection between music and certain occasions was loosened; so-called casual music has been replaced by compositions that were made “for its own sake”.

On the one hand, the texts of the sacred music by Telemann and other church composers were viewed critically, because these, too, now had to submit to the modern rules of poetry. On the other hand, Telemann's particularly consistent implementation of textual ideas such as palpitations, angry pain and the like in music was heavily criticized. In addition, comic opera was seen as a sign of an alleged decline in music.

The following statement by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing is representative of the now prevailing, changed perceptions of composition and poetry :

"Telemann also often exaggerated his imitation into the absurd by grinding things that the music shouldn't grind at all"

Further criticism from the musician came from Sulzer , Kirnberger , Schulz and others. Telemann's reputation dwindled rapidly, and other composers like Graun, who were said to have a more “tender” taste, became fashionable.

In 1770, the Hamburg literature professor Christoph Daniel Ebeling first expressed the conclusion that was later used very often that the enormous scope of Telemann's work suggests a poor quality of the opus by explaining Telemann's “harmful fertility” on the grounds that “polygraphs are rare [ Prolific writers] many masterpieces ” attacked.

Telemann's secular and instrumental work was able to assert itself in front of the critics for some time, but the criticism soon spread to his entire work.

The composer and music critic Johann Friedrich Reichardt complained that Telemann's tone painting was accompanied by courtesy:

“If he [Telemann] learned from the French to be too comfortable to suit the taste of the nation or the people among whom one lived, then I also have a lot of negative things to say about the trip. He really often made himself comfortable after people of the worst tastes, which is why one finds so much mediocre work among his excellent works, and in these the monstrous and silly descriptions "

|

|

An appreciation of the work in the awareness of a changed taste took place only occasionally. John Hawkins, for example, described Telemann in his work A General History of the Science and Practice of Music ..., Volume the Fifth (1776) as "the greatest church musician in Germany"; and Daniel Schubart praised Telemann explicitly.

Ernst Ludwig Gerber has little good things to say about Telemann in his famous music dictionary (1792). He also objects to the text-bound declamation of the "polygraph". Gerber was often quoted later in his assertion that the artist's best creative period was between 1730 and 1750.

After his death Telemann's scores passed into the possession of his grandson, who was later called to Riga and performed several works there. In doing so, he often made edits that were felt to be indispensable - sometimes beyond recognition - in order to “save” his grandfather's work. Nevertheless, interest in Telemann was now almost historical; his works were only occasionally performed in the churches of Hamburg and a few concert halls. Last performances in Paris until 1775 can be proven. From around 1830, apart from a few performances, there was no knowledge of Telemann's work based on personal listening experience.

Regardless of this, there are some examples of personalities who showed interest in Telemann's work. The writer Carl Weisflog mentioned in Fantasy Pieces and Histories that he was impressed by an isolated performance of the Thunder Ode in 1827 .

Systematic defamation

Characteristic of the music-historical mentions of Telemann in the 19th century is the lack of well-founded analysis based on the works and the intensified continuation of previously mentioned points of criticism. Telemann's sacred compositions in particular were accused of a lack of seriousness, which one apparently expected from a German composer. Carl von Winterfeld regarded the text on which the works were based as flat and pathetic, as "tiresome monotony" . Furthermore, he described Telemann's work as "easily and quickly thrown down" , the expression of the spiritual vocal works as faulty and unworthy of the Church:

"An unmistakable talent has apparently only achieved the absurd when it comes to real success and was sufficiently compensated by the brilliant applause of contemporaries, who, however, can never justify the absurd"

In the meantime Telemann's scores by Georg Michael had passed into the possession of the music collector Georg Poelchau . In 1841, after Poelchau's death, they were bought with Poelchau's collection at the “Musical Archive” at the “Royal Library of Berlin”, today's State Library , where they were available for source research.

By the end of the 19th century, the choice of words for Telemann's criticism steadily tightened; according to Ernst Otto Lindner , he created "no artistic creations but factory goods" . The criticism carried over to his person; Lindner, for example, condemned Telemann as vain for his autobiographies and the choice of his anagrammatic pseudonym Signor Melante . Eduard Bernsdorf expressed further critical views , who described Telemann's melodies as "very often stiff and dry" ; here too, many other music critics adopted this formulation.

In the 19th century there was a cult of genius , whereby lonely masters believed to be far ahead of their time were glorified; Audience favorites were viewed with skepticism. In the music world, Carl Hermann Bitter , Philipp Spitta and others initiated the Bach renaissance in the course of their research . This also began a period of disparaging evaluations of many other composers, regardless of the fact that, if at all, one only acquired knowledge of a small fraction of the complete work and, moreover, never carried out any serious work analyzes. In Telemann's case, musicologists oriented themselves primarily to what Ebeling and Gerber said. Some Bach and Handel researchers intensified their criteria with regard to Telemann's creative principles in order to clarify the qualitative difference to these composers:

“Church music after Bach's death flattened out unspeakably, it was not he and Handel who were the models to be pursued, but Telemann and even more Graun and Hasse; Influences from Italian opera paired with contrapunct that had become purely conventional to create a mixture of sensuality and dryness, the forms froze because there was nothing that would have given them drive and life from within. [...] according to Bach, instrumental music begins to sacrifice that objective devotion to tone and its inherent general poetry and sensation content [...]. "

“... just because his [Telemann's] talent for the great was not very productive, he also stays here in everyday life, or with the convulsive, unvoiced and choral treatment of the singing [...] only brings it to the caricature. [... The composition falls] completely against the high originality and swelling freshness of Bach's music. "

“The direct connection established in Telemann's person between the opera and the church immediately exerted its disastrous influence […] Telemann, Fasch and other productive contemporaries were flatter talents, and in this respect their work does not offer a sufficient standard for that of Bach. [... In choral choirs] Bach could not and would not accept anything from Telemann and Telemann would not have been able to do the same even from afar. "

“Can you think of something more unnatural? If the good Telemann had already had an inkling of what Bach had created beautifully, he would hardly have published such nonsense. "

The Bach biographer Albert Schweitzer couldn't believe that Bach apparently uncritically copied entire cantatas by Telemann. In the course of his analysis of the cantata I know that my redeemer lives ( BWV 160), Spitta came to the following judgment: “What Bach made of it is a real gem of moving declamation and wonderful melodic traits.” Later it turned out that this cantata was composed by Telemann. Schweitzer made a similar misstep when, while looking at the cantata I live, my heart, to your delight (BWV 145), he was particularly impressed by the opening chorus “So you with your mouth”, which came from Telemann.

Furthermore, Telemann was accused of conventionality from the 1870s. Lindner wrote that Telemann, coming from the "well-tried school" , would never have achieved actual independence; Hugo Riemann described him as "the archetype of a German composer ex officio" , who had little claim to a revival.

At the end of the 19th century, Telemann's reputation in music-historical circles reached an all-time low.

“Telemann can write horribly leisurely, without strength and juice, without invention; he dumbles down a piece like the other. "

"In reality he was just a talent of the shallowest kind."

rehabilitation

The first attempts at a more thorough examination of Telemann's work took place at the beginning of the 20th century. Above all, the more intensive preoccupation with the source material led to a renewed, almost imperceptible change in Telemann reception.

One of the first musicologists to formulate a more impartial assessment of Telemann's works was Max Seiffert , who in 1899 took a more descriptive than judgmental attitude when analyzing some of his piano compositions. In 1902, Max Friedlaender paid tribute to Telemann, in whose songs full of “witty and piquant melodies” he showed himself to be a “peculiar, amiable, interesting composer who likes to emancipate himself from the stencil of contemporary taste”. In doing so, he claimed the exact opposite of the frequently voiced criticism of the "dry" melodies and the "stencil-like". On the other hand, he also found great inequality in his work. Arnold Schering's verdict on Telemann's instrumental concerts was as follows:

"Telemann's concerts are not free from conventional phrases, but contain a lot of original ideas and artistic sample sentences and above all express an inexhaustible imagination."

The foundations for the rediscovery of Telemann were only provided by Max Schneider's publications and others. Schneider was the first to attack the practice of unfounded criticism of Telemann and tried to understand it in its own historicity. In 1907 he published the oratorio The Day of Judgment and the solo cantata Ino in the monuments of German music art . In his commentary on Telemann's autobiographies, he pointed to the unprecedented change in Telemann's understanding of the past centuries. Schneider particularly criticized the accusation of the “superficiality” of the work and the “sham investigations” carried out on it. He demanded "to avoid deliberately" bon mots "and vague talk about a master who for two generations has been counted among the first in his art by the entire educated world and who is entitled to find proper appreciation in the history of music. "

Subsequently, Romain Rolland and Max Seiffert published detailed work analyzes and editions of Telemann's works.

“[Telemann] has contributed to German music adopting the intelligence and expressiveness of French art and overcoming the danger of becoming pale and expressionless under masters like Graun in an abstract ideal of beauty. [...] At the same time he brought the original verve [...] of Polish and modern Italian music with him. That was necessary: German music in all its size smelled a little of moder. […] Without this, the great classics would appear like a miracle, while on the contrary they only closed the natural development of an entire century of ingenious gifts. "

"Unbelievable to have such wealth and to leave it carelessly gathering dust in the corner!"

For the time being, however, these statements were not noticed by the general public.

Telemann today

Only after the Second World War did work on methodical research into Telemann's oeuvre begin. In the course of the more frequent works on the composer, the assessment of music history also changed. In 1952, Hans Joachim Moser stated:

“Just a few years ago he was regarded as a flat, prolific writer who 'produced more than Bach and Handel put together' and who is said to have boasted that he could compose the goal sheet himself . Today, thanks to many new editions, he stands right behind Bach and Handel as the interesting master of that powerful generation. "

In 1953, the Society for Music Research published the first volume of the selected edition of Telemann's works. Since 1955 this project has been supported by the Music History Commission .

In 1961 the working group "Georg Philipp Telemann" eV was founded in Magdeburg , which was mainly dedicated to research. In 1979 it became a department of the Georg-Philipp-Telemann-Music School under the name Center for Telemann Care and Research , which in turn was renamed the Georg Philipp Telemann Conservatory in September 2000 . In 1985 the Telemann Center became an independent institution.

Since 1962, the city of Magdeburg, together with the “Georg Philipp Telemann” working group, has organized the internationally acclaimed Telemann Festival every two years , with numerous events and conferences aimed at music lovers, musicians and researchers alike. The city also awards the Georg Philipp Telemann Prize every year . Registered associations were formed in several cities that deal with both research and practice. These include the Telemann companies in Magdeburg, Frankfurt and Hamburg.

In addition to editions of works and other publications, sound carrier publications and radio broadcasts soon reached the public. Telemann's first work recorded on record was a quartet from table music , which was published in the French series Anthologie sonore in 1935 . Thanks to the success of the long-playing record in the 1960s and in the course of the discovery of the economic potential of baroque music, around 200 works by Telemann had been published on sound carriers by 1970, which corresponds to only a small part of the entire work. Even today his instrumental music is best developed.

The historical performance practice proved to be crucial in view of the proportion of the instrumentation of Telemann's works as indispensable. Modern instruments completely distort the sound image intended by the composer due to different timbres, so that the “romantic” performance practice often practiced at the beginning delayed an adequate rediscovery of Telemann's work among music lovers. The Telemann cultivation of the 20th and 21st centuries was able to counteract the image of the composer, which was established especially in the 19th century, with partial success.

In March 1990 the asteroid (4246) Telemann was named after him.

On May 8, 2011, the Hamburg Telemann-Gesellschaft eV opened a museum in Hamburg that is dedicated to the composer. The Hamburg Museum is the first Telemann Museum in the world. It serves to promote culture and education in Hamburg, and one of its tasks is to impart extensive knowledge about the Hamburg Director Musices, the cantor of the five main churches from 1721 to 1767 and the director of the Hamburg Opera from 1722 to 1738. The Telemann Museum is located at Peterstraße 31 (in the so-called composers' quarter ) and in the same building as the Johannes Brahms Society and Museum.

The Telemann Foundation was established in 2013 to provide permanent and exclusive support to the Hamburg Telemann Museum. Board of Directors: Erich Braun-Egidius (Chairman), Marcus Buschka, Esther Hey, Mathias v. Marcard, François Maher Presley . In the garden house in the Klosterbergegarten in Magdeburg the exhibition Listen, Telemann! shown on the life and work of Telemann.

See also

literature

- Monographs

- Karl Grebe: Georg Philipp Telemann. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2002 (10th edition), ISBN 3-499-50170-8

- Gilles Cantagrel: Georg Philipp Telemann ou Le célèbre inconnu (= Mélophiles 14). Éditions Papillon, Genève 2003, ISBN 2-940310-15-7

- Eckart Kleßmann : Georg Philipp Telemann . Hamburg heads. Ellert and Richter, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-8319-0159-7

- Werner Menke: Georg Philipp Telemann: Life, work and environment in picture documents. Heinrichshofen, Wilhelmshaven 1987, ISBN 3-7959-0399-8

- Richard Petzoldt : Georg Philipp Telemann - life and work . VEB German publishing house for music, Leipzig 1967.

- Siegbert Rampe : Georg Philipp Telemann and his time . Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2017, ISBN 978-3-89007-839-7

- Erich Valentin : Georg Philipp Telemann . Bärenreiter, Kassel-Basel 1952.

- Further literature and document collections

- Robert Eitner: Telemann, Georg Philipp . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 37, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1894, pp. 552-555.

- Wolfgang Hirschmann : Telemann, Georg Philipp. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 26, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-428-11207-5 , pp. 12-15 ( digitized version ).

- Günter Fleischhauer: The music of Georg Philipp Telemann in the judgment of his time. In: Handel yearbook. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1967/68, pp. 173–205, 1969/70, pp. 23–73.

- Hans Große, Hans Rudolf Jung (Ed.): Georg Philipp Telemann, correspondence. All available letters from and to Telemann. German publishing house for music, Leipzig 1972

- Annemarie Clostermann: Georg Philipp Telemann in Hamburg (1721–1767): Documents tell stories. An exhibition by the Hamburg Telemann Society and the Hamburg State and University Library, August 19 to October 2, 1998. With a foreword by François Maher Presley . [Ed .: Hamburger Telemann-Gesellschaft eV] “Culture in Hamburg”, publishing company mbH, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 978-3-930727-08-7

- Christine Klein: Documents on Telemann reception 1767 to 1907 . Series of publications on Central German music history. Ziethen, Oschersleben 1998, ISBN 3-932090-31-4

- Gabriele Lautenschläger: Telemann, Georg Philipp. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 11, Bautz, Herzberg 1996, ISBN 3-88309-064-6 , Sp. 622-625.

- Jürgen Neubacher: Georg Philipp Telemann's Hamburg church music and its performance conditions (1721–1767): organizational structures, musicians, casting practices (= Magdeburg Telemann Studies 20). Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 2009, ISBN 978-3-487-13965-4

- Annemarie Clostermann: Georg Philipp Telemann: The Hamburg years. Edited and with texts by François Maher Presley . in-Cultura.com , Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-930727-41-4

- Annemarie Clostermann: Georg Philipp Telemann: A Hamburg foundation. [Ed .: Telemann Foundation. Photographs, texts (art and artists) and design: François Maher Presley . Scientific texts: Annemarie Clostermann]. in-Cultura.com, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-930727-41-4

- Werner Rackwitz : Georg Philipp Telemann - Singing is the foundation of music in all things. A collection of documents . Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1967, 1981, 1985.

- Bernhard Jahn, Ivana Rentsch (eds.): Extravagance and business acumen - Telemanns Hamburger Innovations , Hamburg Yearbook of Musicology, Volume 1, Münster New York, Waxmann 2019, ISBN 978-3-8309-3997-9 .

Complete CD recordings

- Telemann: Complete Trumpet Concertos: 2005 - Otto Sauter - trumpet - Chamber Orchestra Mannheim - Nicol Matt - conductor

- Telemann: Tafelmusik: Musica Amphion & Pieter-Jan Belder

- Telemann: Tafelmusik Complete: 2008 - Brüggen, Frans, Coam - Concerto Amsterdam - Frans Brüggen

- Telemann: Complete Tafelmusik: Freiburg Baroque Orchestra - Petra Müllejans , Gottfried von der Goltz

- Telemann: Complete Violin Concertos, Vol. 1 by Georg Philipp Telemann (April 24, 2004): 2004 - Elizabeth Wallfisch - L'Orfeo Barockorchester - Michi Gaigg

- Telemann: Complete Violin Concertos, Vol. 2 (February 27, 2007): 2007 - Elizabeth Wallfisch - L'Orfeo Barockorchester

- Telemann: Complete Violin Concertos Vol.3: 2010 - The Wallfisch Band & Elizabeth Wallfisch

- Complete Violin Concertos Vol.5: 2012 - Elizabeth Wallfisch - The Wallfisch Band

- Telemann: Complete Violin Concertos, Vol. 6: Elizabeth Wallfisch - The Wallfisch Band

- Telemann: Complete Overtures, Vol. 2: Collegium Instrumentale Brugense & Patrick Peire

- Telemann: Complete Concertos and Trio Sonatas: 2015 - Cristiano from Contadin & Ensemble Opera Prima

- Telemann: Complete Trio Sonatas: 2008 - Trio Sonatas for Violin, Flute & BC - Trio Sonatas for Oboe, Recorder & BC - Fabio Biondi, Alfredo Bernadini, Lorenzo Cavasanti - Ensemble Tripla Concordia

- Telemann: Complete Suites and Concertos for Recorder: Erik Bosgraaf Ensemble Cordevento

- Telemann: Complete Orchestral Suites: 2012 - Pratum Integrum Orchestra

- Telemann: Organ Music - Complete Edition (Arturo Sacchetti): 1988 - Arturo Sacchetti

- Telemann: Sivori - The Complete Trios, Romances, Phantasias - Bruno Pignata, Riccardo Agosti, Franco Giacosa: Giuseppe Nalin - Der Harmonische Gottesdienst (Vol. 1)

- Telemann: Complete Orchestral Suites Vol. 1: 2009 - Pratum Integrum Orchestra

- Telemann: V 2: Complete Recorder Music by Georg Philipp Telemann (December 6, 1995): 1987 - Rachel Podger - The Duets, Volume II - Glas Pehrsson and Dan Laura, recorders

- Telemann: Complete Orchestral Suites by Georg Philipp Telemann / Pratum Integrum Orchestra (2SACD) (2011) Audio CD: 2011 - Pratum Integrum Orchestra

Web links

- Works by and about Georg Philipp Telemann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Georg Philipp Telemann in the German Digital Library

- Literature on Georg Philipp Telemann in the bibliography of the music literature

- Documents on Telemann at www.telemann-archiv.de

- Telemann, Georg Philipp. Hessian biography. (As of May 9, 2020). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- Telemann, Georg Philipp in the Frankfurter Personenlexikon

- Institutions

- Telemann in Magdeburg

- Telemann Society e. V. (International Association)

- Frankfurt Telemann Society

- Hamburg Telemann Society

- Works

- Sheet music and audio files from Telemann in the International Music Score Library Project

- Sheet music in the public domain by Georg Philipp Telemann in the Choral Public Domain Library - ChoralWiki (English)

- Telemann's catalog of works at Klassika.info

- Telemann works directory (French)

- Digital copies of more than 600 cantatas by Telemann in the music manuscript collection "Frankfurter Kirchenmusik" of the Johann Christian Senckenberg University Library

- Anniversary events for the 250th year of Georg Philipp Telemann's death in 2017 in Europe

swell

- ↑ When Telemann was born, the Julian calendar was still in effect in Magdeburg . Telemann was born in the Heilig-Geist-Kirche in Magdeburg on March 17th . baptized, see the copy of the baptism entry in the monograph by W. Menke.

- ^ Siegbert Rampe: Georg Philipp Telemann and his time. Laaber Verlag, Laaber 2017. S. 111ff.

- ↑ Michael Maul (Ed.): Germanicus (1704/1710). Critical edition of the preserved 41 arias by Georg Philipp Telemann and the libretto by Christine Dorothea Lachs (= The sources of the Leipzig Baroque Opera [1693–1720] 1). Ortus Musikverlag, Beeskow 2010, ISMN M-700296-58-2

- ^ Lutz Felbick : Lorenz Christoph Mizler de Kolof - student of Bach and Pythagorean "Apostle of Wolffian Philosophy" . Georg-Olms-Verlag, Hildesheim 2012, ISBN 978-3-487-14675-1 (University of Music and Theater “Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy” Leipzig - Writings; 5), pp. 278–299.

- ^ Johann Mattheson: Critica Musica I , Hamburg 1722, p. 24. Quoted in Fleischhauer 1967/68, p. 180

- ^ Johann Scheibe: Der critische Musikus , 2nd edition, 1745, p. 146f. Quoted in Fleischhauer 1967/68, p. 182

- ^ Peter Wollny: Johann Sebastian Bach, Apokryphe Cantatas. Booklet to the CD "Apocryphal Bach Cantatas II" (Alsfeld Vocal Ensemble, conducted by Wolfgang Helbich). cpo , 2004

- ↑ Friedrich Wilhelm Zachariä: The times of day (1754). In: Poetic Writings , Vol. II, Braunschweig 1772, p. 83. Quoted in Fleischhauer 1969/70, p. 41

- ↑ Gotthold Ephraim Lessing: Collektaneen for literature. Edited and continued by Johann Joachim Eschenburg. Volume Two K-Z. Berlin 1790, p. 173. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 28f.

- ↑ Christoph Daniel Ebeling: An attempt at a selected musical library. In: Conversations. Vol. X, 4th piece. Hamburg, October 1770, p. 316. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 25

- ^ Johann Friedrich Reichardt: Letters from an attentive traveler regarding music ... , Zweyter Theil. Frankfurt and Breslau 1776, p. 42f. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 51

- ↑ Carl von Winterfeld: The Protestant church song and its relationship to the art of tone setting ... , third part. Leipzig 1847, p. 209. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 126

- ^ Ernst Otto Lindner: The first standing German opera ... Berlin 1855, p. 116. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 139

- ^ Eduard Bernsdorf (Ed.): New Universal Lexicon of Tonkunst. Third volume. Offenbach 1861, p. 707. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 145

- ↑ Arrey von Dommer : Handbuch der Musikgeschichte… Leipzig 1868, pp. 506f., 557. Quoted in Klein 1998, pp. 169f.

- ↑ Philipp Spitta: Johann Sebastian Bach… first volume. Leipzig 1873, pp. 50, 493. Quoted in Klein 1998, pp. 189, 194

- ^ Philipp Spitta: Johann Sebastian Bach ... , second volume. Leipzig 1880. pp. 27, 180, 244. Quoted in Klein 1998, pp. 217, 220

- ↑ Otto Wangemann (arr.): History of the oratorio from the first beginnings to the present ... Third edition. Leipzig 1882, p. 188. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 235

- ^ Hugo Riemann: Musik-Lexikon… Leipzig 1882, p. 907. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 228

- ^ Robert Eitner : Cantatas from the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th century. In: Monatshefte für Musikgeschichte , XVI, 4:46, Leipzig 1884. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 237

- ↑ Salomon Kümmerle (arrangement and ed.): Encyclopedia of Protestant Church Music… Gütersloh 1888–1894, Third Volume, 1894 p. 594. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 264

- ↑ Max Seiffert: History of Piano Music. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1899

- ^ Max Friedlaender: The German song in the 18th century. First volume, first Abth., P. 77. Stuttgart and Berlin 1902. Quoted in Klein 1998, p. 288

- ^ Arnold Schering: History of the instrumental concert up to the present ... Leipzig 1905, p. 120 f.

- ↑ Max Schneider: Introduction. In: Georg Philipp Telemann. The day of judgment ... Ino. In: Monuments of German music art. First episode. Vol. 28 Leipzig 1907, p. 55

- ^ Romain Rolland: Memoirs of a Past Master. In: A musical journey into the land of the past. Translation from French. Rütten & Loenig, Frankfurt am Main 1923, pp. 103-145

- ↑ Max Seiffert: G. Ph. Teleman - Musique de Table. Comments on volumes LXI and LXII of the monuments of German music art, 1st episode. Supplement to the Monuments of German Music Art II, p. 15. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1927

- ^ Hans Joachim Moser: Georg Philipp Telemann. In: Music history in 100 life pictures. Reclam, Stuttgart 1952. Quoted in Grebe 2002, p. 152

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 16045

- ↑ Telemann Museum on telemann-hamburg.de, accessed on May 1, 2019.

- ↑ http://www.telemann-stiftung.de

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Joachim Gerstenbüttel |

Cantor et Director chori musici in Hamburg 1721–1767 |

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Telemann, Georg Philipp |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German baroque composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 24, 1681 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Magdeburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 25, 1767 |

| Place of death | Hamburg |