Property theories

Property theories are systematic attempts to explain the emergence and justification of the social institution of property .

The right to personal belongings is usually not called into question. However, there are controversial positions with regard to the ownership of land and, since industrialization , the ownership of the means of production . The question of whether and to what extent ownership arises from social responsibility is often discussed under the heading of “ social responsibility of property ” . Theories of property are therefore often part of political philosophy , especially of state theories . With the differentiation of the sciences since the 19th century, independent perspectives have developed in economics , political science and sociology .

Property is at the same time an object of theological social ethics , the science of history or social anthropology . As a legal term, property is subject to both private and public law .

Systematics

Depending on the point of view, the authors of property theories orient themselves more towards the economic community , the political structures of a society or the cultural traditions ( religion , ethics , law ). One can often distinguish theories of property according to whether they are individualistic or collectivistic . Some theories assume that by nature , or in prehistory and early history , there was no private property. It is further asserted that individual property ( private property ) is the main cause of wars and other violent conflicts. Among the collectivist property teachings include various utopias of Plato's Politeia about the traditions of the founder of Stoicism Zeno of Kition , Thomas Morus ' Utopia up to the sunshine state of Tommaso Campanella rich. With industrialization , anarchist or socialist models of society emerged in the modern age , especially those of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Karl Marx , which criticized above all the ownership of the means of production and the unequal distribution of goods . In addition to the protagonists of actually existing socialism , religious groups such as some Anabaptist groups such as the Hutterites , the Jesuits in Paraguay , Shaking Quakers or the kibbutz movement tried to put these ideas into practice.

Most authors of property theories assume a right to private property. This is based either on a practical agreement, as with Aristotle , Thomas Aquinas , David Hume and the advocates of the theory of rights of disposal, or on a natural law , as for example with Samuel von Pufendorf and Hugo Grotius , on the human right , as John Locke assumed or after Immanuel Kant on the law of reason . Concepts of property are often linked to theories of social contract and constitutional law. After the establishment of a legitimate origin of property, one differentiates between the following theories:

- original occupation

- Primary acquisition takes place through the appropriation of abandoned objects (compare original property acquisition and occupation economy ). All other acts are derived acquisition ( exchange , purchase , inheritance , robbery ).

- Acquisition through work

- The real value of natural resources is low. The creation of the value of a good is connected with the work that is put into changing and using the good. So the right to property is given to those who invest their labor in an object.

- Legalization of existing conditions in the state

- Ownership claims have developed historically in social practice. The institution of property serves to create security, includes the recognition of existing structures and regulates the transfer processes.

The occupation theory is historically the oldest conception that can be traced back to antiquity . Its disadvantage is that it is politically largely neutral and can be used both for the establishment of a liberal state and for an absolutist rule and for an order following the community principle. For this reason, John Locke drafted the concept of labor theory , because on its basis an interference by the state in individual rights could no longer be justified. This theory prevailed in the Enlightenment and became a dominant paradigm into the modern age. Only recently did a pragmatic view, as in Hume's work , and the Kantian “law of reason” gain importance. In contemporary literature, Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld and Tony Honoré 's view of property as a “bundle” of rights and duties in a democratic constitutional state is increasing . It comprises different components depending on the author, for example:

- "The right to own ( English right to possess ) - the only physical control over a thing. If the thing is incorporeal, possession can also be understood metaphorically ;

- The right to use ( English right to use ) - the personal use of the thing in the narrower sense, ie excluding points three and four;

- The administrative right ( English right to manage ) - the right to determine the use of the property, eg by way of the granting of a license ;

- The right to the income from the use of property ( English right to the income );

- The right of the consumption or the destruction ( English right to consume or destroy );

- The right to modify or change the property ( English right to modify );

- The right of disposal ( English right to alienate ) - transfer "inter vivos" or Dereliktion ;

- The right to security ( English right to security ) - protection against expropriation ;

- The right of inheritance ( English incident of transmissibility );

- The absence of time barriers ( English incident of absence of term );

- The prohibition of (deliberately) harmful use ( English prohibition of harmful use );

- The seizure ( English liability to execution ) - the realization of the property by way of foreclosure ;

- The other, supplementary provisions ( English residuary character ) - there are those standards that have expired or abandoned property rights to the reversion of (temporary) rules (provisions on the legal succession, the adverse possession , the whereabouts of the discontinued property and the like.. ). "

The task of a property system is to determine which of the elements come into play and to what extent, who may be the owner (only natural or legal persons ) and what should be considered property (personal property, means of production, intellectual property , yes or no).

In many constitutions of the modern age, the protection of property is treated as a fundamental right , i. H. the constitution contains the protection of property as a principle, without determining its content. The material content of the rights and obligations associated with property as well as the limits of property use is left to the determination in the individual laws. This also includes determining the extent of the social liability of property .

Such a constitutional regulation enables the content of the concept of property to be updated within laws according to changed social conditions and values , without having to intervene in the constitutional principle as such. Characteristics of property are not only the assignment of an object to a person and the arbitrary power of disposal, but also the demarcation of the respective property system. “When speaking of the content of property, it is based on the idea that the legal system stipulates the extent to which the owner must allow interference with his rights, that is, property only takes shape through the interference norms. Only these constitute property as a legal entity. "

history

When considering the theories of property in history, the economic, legal and political framework conditions of the time are important. The authors had a certain worldview or social model in mind and usually wanted not only to explain and justify the phenomenon of property, but also intended to create an ideal image within the framework of more tense political theories and to influence social development.

Antiquity

The traditional reflection on the meaning of property begins with the works of Plato and Aristotle in ancient Greece . Society at that time was still predominantly organized on an agricultural basis. Even in the polis of Athens the people were more involved in agriculture than three quarters. Society was dominated by the nobility and large landowners , even if the reforms of Kleisthenes had enabled the citizens to participate in the decisions of the polis. The family households ( oikos ) were the social and economic core . This household also included slaves who were bought or who had come to Athens in the course of colonization. The debt slavery was by the laws of Solon abolished. In the Oikos everything was subordinate to the householder, who exercised the rights of the owner over the entire property , wife, children and slaves, but was also responsible for their well-being. A special feature was the social order in Sparta , where property was allocated by lot and was inalienable. Instead of gold and silver, iron was used as money , and there were communal meals for the Spartians ( Syssitia ).

The ancient Greek philosophers were strongly anchored in the community of all free citizens within the polis. This and the idea of integrating people into a harmoniously ordered cosmos was what they oriented their thinking about the good life . The modern, freedom-oriented perspective of individualism was alien to them. While the sophists and Socrates were still actively involved in political discourse, Plato and Aristotle concentrated on teaching and developing their theories. With Plato the question of the right order in the community was in the foreground, which he answered with the concept of an ideal state . The role of the individual was hardly important. The constitution of property is tied to the structure of the social order. Justice comes from doing right . Aristotle was more skeptical about educability. He tried to develop right structures and rules from the given, which should become generally binding. Property is therefore a question of the purposeful, reason-based human thought and action.

The philosophy that followed in Hellenism was influenced by the great empires of Alexander and Rome . Even if the cities remained largely unaffected in their internal administration, the socially and politically significant environment became much larger and more complex. There was no longer any direct influence of the philosophical schools on politics. The Stoa accordingly concentrated on the personal attitude of the individual, to whom it advised a cosmopolitan attitude to life guided by reason and serenity . In the Roman Republic, legal issues came to the fore when it came to the regulation of property.

Plato

Plato's examination of property in the Politeia does not refer to the actually existing society, but is the blueprint for a just , successful state called utopia as an analogy to the just, happiness-oriented soul - i.e. an alternative to the real conditions. In this ideal state, every adult person occupies the appropriate position. So there is the subsistence level of the craftsmen and farmers who also have property in this state. The guards (armed forces) ensure the cohesion of the state. They have no property because the pursuit of property does not serve the community. Rather, the guards get their livelihood from society, and in return their entire area of life, including their home, is accessible to the public. Even the philosophers (apprenticeship), who are suitable for Plato after education and training to lead the state, remain without property. In his late work, the Nomoi , Plato dealt with the question of what the state order of a colony that was yet to be founded should look like. Here he deviated from his ideal and envisaged a distribution of the property. This is, however, even, and the land cannot be sold, it can only be inherited or transferred to someone who does not own land.

Aristotle

Similar to Plato, for his student Aristotle the goal of human life was good , not wealth, which is only a means to achieve this goal. Aristotle rejected the acquisition of wealth for its own sake, the art of making money ( chrematistics ). The institute of property does not come from the natural order, but is the result of human reason . Ownership was not required in the original oikos. Only when the population grew to specialize, did the exchange between households arise. In village communities and in the polis, individual property is preferable to communal property, because personal property results in greater care for property. Second, private property corresponds to the principle of performance. Furthermore, ownership clearly regulates responsibilities so that disputes can be avoided. Personal property is for enjoyment in the community and is a prerequisite for the virtue of freedom of movement. Common ownership therefore only makes sense where it is used jointly and requires joint financing.

Roman Empire

The earliest codification of law in ancient Rome was the Twelve Tables Law , which had the purpose of regulating the conflicts between the landowning patricians and the plebeians . Purchase contracts were regulated here in a very formalized way as libral files . As in Greece, Roman society was organized in households ( dominion : property, right of possession). The landlord, the Pater familias , was the unrestricted owner. Adult sons were also not legally competent if they lived in their father's house, even if they were married and had children. The pater familias was even able to sell his children into slavery. He could inherit his property without restriction by will. If there was no will, the succession was in the male line.

There was no formal definition of property in Roman law, but there were various forms of property. In addition to the domination related to the household, a distinction was made between property linked to the person, the proprietas. Furthermore, there was a right of participation (ius in realiene) that allowed certain uses. A distinction from property was possession (possessio). In principle, property was absolute in terms of having, possession, use and fruiting (habere possidere uti frui licere) and also unlimited in the air and underground (usque ad coelum et inferos). From the description “meum esse aio” (I claim that it is mine) it can be deduced from practice that the definition in § 903 sentence 1 BGB largely corresponds to the content provision at the time of Cicero .

Cicero dealt with the establishment of property. For him, private property originally arises through occupation :

- “But there is no private property through nature, but either through earlier occupation (as with those who once came to unoccupied areas) or through victory (as with those who seized it in war) or through law, agreement, contract or go ”.

The Romans regarded the land of the conquered provinces as the property of the Roman people and thus established the right to a land tax ( tribute ). The Romans already knew of an immission ban (see § 906 BGB), i. H. someone could not use his property arbitrarily if he thereby impaired the property of others, e.g. B. by drainage ditches, the water of which drained on unfamiliar ground.

In the philosophy school of the Stoa , a reason-oriented, measured life was emphasized. External values are of secondary importance for a meaningful life . Wealth was not regarded as a suitable measure of the importance and dignity of a person, which are of the same nature regardless of class and origin. Seneca clearly described this attitude:

- “No one else is worthy of God than someone who despises wealth. I do not forbid you to own it, but I want to make sure that you own it without trembling: You can achieve that in one single way, if you are convinced that you can live without it, if you always regard it as almost disappearing. "

Above all, wealth arises from greed and is the cause of some evils.

Patristic

In the early church in Jerusalem , according to Acts 2 and 4, property was given up in favor of a community of property . However, when the near expectation of the Christian return did not come true, property arose again in the early Christian communities. However, a new view of property developed in patristicism through the spread of Christian-Jewish ideas, according to which natural law is to be equated with divine law. In the Old Testament the land is handed over to man for administration - but it remains the property of God. For the church fathers like Clement of Alexandria , the question of the correct use of property, taken from the Stoa , was in the foreground. Critical to the ownership of land expressed as Laktanz . Basil of Caesarea , John Chrysostom or Ambrose of Milan emphasized that wealth stands in contrast to the fact that earthly goods are given to all people in the same way. Basil shaped the image of a seat in the theater. This is a common good, even if someone who has just taken possession of it calls it his own. On the other hand, the commandment to give to those in need implies that property exists at all. As a consequence, many church fathers demanded that property that goes beyond their own needs be passed on to the poor. According to Pauline teaching, the rich in the community have a duty of care towards the poor. ( "One carries the burden of the other" , Gal. 6, 2)

middle Ages

Among the Teutons , the status of the fortified farmers and the institute of the commons had developed. This structure was replaced in the early Middle Ages at the time of the Carolingian Empire by the formation of the knighthood , through which central rule could be better secured. The medieval ownership structure was shaped by manorial lords , which existed either as fiefdoms (right of use granted by the sovereign) or less widespread as allodies (inheritable property). Property in the cities, but also the sometimes very large property of the monasteries, was mostly property (allod). Agriculture was usually self-sufficient. There were free and unfree peasants. The bulk of the people lived as servants or day laborers . There was the form of bondage linked to the person as serfdom and the basic bondage linked to the ground. While in Italy the cities gained a counterweight to the landowners early on, urban structures only gradually emerged north of the Alps. Trade and market law developed in the cities, and fairs , merchants' guilds and craftsmen's guilds came into being in Flanders . A high point in the High Middle Ages was the founding of the Hanseatic League .

Property was or is often identified by so-called house brands , for example coats of arms and brands . The boundary stones dating back to the Hermes cult are used to mark real estate . William the Conqueror introduced what is probably the first land register for land in England in 1086 , the Domesday Book . Independently of this, the medieval German cities kept city registers , forerunners of today's land registers.

The revival of Roman law was of particular importance for legal history in the Middle Ages, initiated by research by lawyers at universities, above all at the University of Bologna . This also had an influence on the canonical church law represented by the decretists , which was systematically summarized in the Decretum Gratiani . In the 14th century, a definition of property that corresponds to the modern understanding is found for the first time. For the Italian lawyer Bartolus , property was "the right to fully dispose of a physical thing (land or movable property), unless a law forbids it."

Due to the diverse performance obligations in the inconsistent feudal system, the concept of land ownership in the Middle Ages can hardly be compared with the modern understanding of the term. Fiefdoms had the upper property (dominium directum) and received a basic rent in kind, services or money, but had to let their farmers and tenants do it if they fulfilled their duties. The tenants as owners had sub-property or usable property (dominium utile) and found legal protection through so-called trades . The legal relationship originally consisted of the personal relationship between masters and dependents. It was only gradually replaced by the right bound to the thing with (hereditary) possession, use and burdens. There were shared ownership as the modern leasehold similar right to use the emphyteusis , the separation of ownership of the building and on the ground ( Superficies ) or borrowing from country ( precarium ). Intangible property existed in the form of rights (" righteous ") such as the sovereignty of the courts and regalia . The first corporations ( Societas Maris in the 13th century and Karat-Gesellschaft in the 15th century) emerged in Genoa , in which ownership in the form of shares was no longer geared towards the disposal of the property, but towards the income (similar to the basic rent) . The legal protection of the property was u. a. expanded by the " embarrassing neck court order " of Charles V , with which, above all, legal certainty in criminal law was strengthened.

The great thinkers of the Middle Ages were primarily theologians who dealt with the relationship between faith and the world. They were all trained through church education and members of religious orders who did not know an individual wealth, in some cases even rejected it. Beginning with the investiture dispute , the Middle Ages were shaped by the conflict over supremacy between secular rulers and the church. The discovery of the Aristotelian scriptures in the western world had a great influence on thought. Above all, the Dominicans around Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas tried to integrate these into the church's teachings. The determination of the relationship between faith and reason led to intensive discussions about the interpretation of divine law, natural law and civil law, a subdivision that was already known in the Stoa (lex aeterna, lex naturalis and lex humana). The Franciscans, more oriented towards Augustine , with Duns Scotus and Ockham as outstanding representatives, were more skeptical of the idea of integration . They emphasized the different spheres of faith (theology) and knowledge (philosophy) that must be brought into the right relationship. The shaping of positive law and thus of property rights became more of a political task for them. All parties agreed, however, on the Christian imperative of social responsibility for property and called for generosity towards the poor. In the late Spanish Scholastic period, the Salamanca School dealt particularly with questions relating to the flourishing economy at the time. In the property question, she refined the teachings of Thomas, took into account the criticism of Duns Scotus and above all linked the idea of the first acquisition with the idea of the social contract.

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas did not develop his own theory of property, but dealt with the subject in his Summa Theologica in the context of the question of law and justice . He took a mediating position between the teaching of Aristotle and the conceptions of patristicism. Accordingly, property is not to be justified by natural law :

- “Everything that is against natural law is prohibited. But according to natural law all things are common property; but this commonality contradicts own ownership. So man is not allowed to acquire an external thing. "

However, property is still permissible based on the law of reason :

- "That is why own possession is not against natural law, but is added to natural law on the basis of the discovery by human reason."

Thomas named three reasons of reason for property that can already be found in Aristotle: On the one hand, property leads to greater care for things. Second, ownership clearly regulates responsibilities. And finally, a property system ensures legal security. Since property is divine according to natural law, earthly property is committed to the common good. and there is a strict duty to give alms. Human need takes precedence over property rights.

Ockham

An important step in the development of the conception of property is the teaching of Wilhelm von Ockham , who defined as property what can be sued in court. The biblical authority to use things establishes an individual right to create property that is protected from unauthorized access. Property is acquired through the subjective decision of the person. It is thus detached from divine natural law, which man can only recognize within the framework of his limited reason, and is based on agreement. The legitimation of property does not come from natural law, but from positive international law (ius communis). The only natural right that Ockham recognizes is the right to preserve oneself. From this arises the claim of the poor to receive at least as much from the rich as they need to live. Natural law also means that all people are free, even if international law permits slavery. Especially with regard to slaves and the position of women, he opposes the tradition since Aristotle, which was still represented by Thomas Aquinas.

Spanish late scholasticism

As a bridge between the Middle Ages and modern times, considerations about property of the Spanish late scholasticism , especially the school of Salamanca , played an important role. Their representatives were in the tradition of Thomas Aquinas, whose teachings they further developed, especially in questions of economics. Francisco de Vitoria stated in a comment on Thomas that property is based neither on divine nor on natural law, but on human law. According to Vitoria, private property serves to implement the natural law requirement to live in peace. Therefore private property is an implementation of natural law, even if it cannot be derived directly from it. With this thesis he wanted to resolve a contradiction in Thomas' thinking, in which the earth was given to humans by nature as common property, while on the other hand reason suggests the expediency of private property. From Duns Scotus , Vitoria took the idea of the social contract and linked it to the question of property by starting from an initial (not explicit) partition contract by which people had agreed on the principle of private property through occupation.

Similar to Vitoria, Luis de Molina also argued that private property does not contradict common property under natural law. It can be agreed voluntarily, it is not necessary. Accordingly, Molina classified the initial occupation as an unnecessary agreement. After that, private property can also be abolished again by agreement. Property regulations are subject to human disposition. Joseph Höffner emphasized the importance of the Spanish late scholasticism for the modern age in 1947: “With the deeper understanding of the Spanish scholastics, it will become increasingly clear that they were the most important source for Hugo Grotius , and that Grotius even derived not a few of his system-forming thoughts from them has scooped. The fame of Grotius is largely due to the disappearance of the Spanish scholastics. "

Early modern age

The growth of cities that began in the late Middle Ages, the increasing number of universities being founded, the invention of printing , the discovery of America , the Renaissance and humanism characterize structural changes in society at the beginning of the early modern period . Thought became more secular , the Church resisted with the Inquisition , but had to accept its loss of power through the Reformation , the development of the natural sciences and the formation of the nation states. The dominant form of rule in the 17th and 18th centuries was absolutism . The subsistence economy began to disintegrate. The structures of feudalism were gradually softened by city rights , village regulations and the transfer of jurisdiction to the parishes. In rural areas, groups of resettlers such as heuerlings or Kötter and Bödner emerged . The economy became more complex with pre-industrial modes of production such as home work and first manufactories and an expanding market economy . The differentiation of natural law led to a more individual legal understanding of property. The transition to mercantilism and physiocratism developed . During this time, intellectual property emerged as a new form of property, initially as privileges , then also protected by patent law (Venice 1474, Great Britain 1623, France 1790). The mountain orders of the 15th and 16th centuries also fall under the scope of privileges . The questions copyright were first settled in the 18th century.

Criticism of property in 17th century England can be found among the Levellers , who advocated greater equality in parliament. Even more radical were the Diggers with their leader Gerrard Winstanley , who tried to establish a Christian form of early communism in the country.

With the secularization of the early modern period there is an effort to base the arguments solely on reason. An important impulse came from Hugo Grotius , who tried to systematize his legal doctrine according to the “mathematical method”, drawing on the various legal traditions of canon law and Roman and Germanic law . Other important thinkers in this line were Samuel von Pufendorf , whose textbook was regarded as a basic work up to the time of Kant, and the school educator Christian Wolff , for whom property formed the basis of the system of natural law, on which contract law, family law and building up domestic law, constitutional law and international law. For the natural rights activists, the acquisition of property through occupation was still a matter of course. Their aim was to use systematic legal principles to achieve greater legal certainty and thus greater independence of law from the church as well as from the arbitrary setting of positive law by the absolutist rulers.

In contrast, the political philosophy of Thomas Hobbes , for whom the law was an instrument to limit people's striving for power, is without recourse to tradition and consistently rationalistic . From personal experience, peace and security were more important to him than freedom and justice. He did not recognize an over-positive right . The limits drawn by Hobbes by absolutism were increasingly repressed by the claim to individual rights in the course of the Enlightenment. With John Locke there is a strong subjectivation of natural law (live, liberty & property as human rights). With his theory of the creation of property from work, directed against absolutist claims, as formulated by Robert Filmer , he took into account the fact that on the one hand land was distributed and recorded in cadastres and on the other hand the bourgeoisie, like himself, built property through successful economic activity . Accordingly, Thomas Paine pointed out critically that the inherited privileges of the nobility and the royal family were based on original violence. The orientation of property to the common good no longer played a role with Hobbes, and hardly with Locke. Rousseau is quite different, who made the right to private property dependent on the service of the common good and on the general will. In this contrast between Locke and Rousseau, the modern conceptions of property are reflected: the greatest possible freedom of ownership as the predominant dogma in the USA, limitation of property rights through social obligations in continental Europe. In the Scottish school, on the other hand, especially with David Hume and Adam Smith , the question of the usefulness of property was in the foreground. They renounced an idealizing justification through natural law and thus became forerunners of utilitarianism and masterminds of a market economy . A further strengthening of the subjective perspective can be found in Immanuel Kant , for whom personal freedom is expressed in property as external mine and yours. Locke's labor theory of property, which he had drafted as an argument against interference by an absolutist government, met with major criticism from Kant. For the latter, the organization of property rights was solely a question of a reasonable republican order.

reformation

Martin Luther , who particularly emphasized the importance of the Bible as a basis (sola scriptura), concluded from the commandment “You shall not steal” that property is a fundamental part of Christian life. Those who have nothing cannot give anything to the poor either. At the same time, however, he emphasizes that nobody should hang his heart on property.

- “Your goods are not yours; you are a conductor, set about distributing them to those who need it. "

True faith breaks away from worldly things.

- "Yes, there must be a great fervor and fiery love that burns so that man can let go of everything, house and farm, wife, child, honor and property, body and life, yes, despise and trample on that he only keeps the treasure, which he does not see and is despised in the world, but is carried forward only in the mere word and believed with the heart. "

What one has should be enjoyed as God's gift.

- "Oh yes, that would truly be a fine life, eat and drink what God bestows, until [be] happy with your wife, just don't let it go as if that were your consolation."

Luther was also a sharp critic of the abuse of property by usury .

John Calvin made a stronger distinction than Luther between divine laws and secular rule, which are "two completely different things". The connection is made through faith. Through conscience man is so overwhelmed by the “power of truth that he cannot help but affirm the legal principles of what is just and just.” The earthly area of law is based on natural law, according to which the rights to life and property are inviolable . Calvin also saw a justification in the eighth commandment, which requires that the property (suum cuique) of the other be left untouched. What is special about Calvin's teaching is the teaching of predestination . Through a godly life, man can obtain the grace of God. The expression of such a life is the worldly success achieved with a sense of duty and work. In his work The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism in the Early 20th Century, Max Weber derived the thesis that the pursuit of profit and capitalism were promoted in a special way from this attitude .

Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes , who philosophically supported absolutism , advocated the thesis in the Leviathan that as a result of the war everyone against everyone in the original state “there is neither property nor rule, nor a certain mine and yours, but that everyone only owns what they gain can, and for as long as he can claim. ”A strong ruler is required to enforce property and justice, which for Hobbes are primarily expressed in legal certainty and freedom of contract . Such a position arises in the Hobbesian social contract , in which the individual transfers his or her freedom rights to a central, all-powerful ruler. As the absolute ruler, he lays down laws and enforces them. The legal positivism , which was still limited by the ability to know the reason in Occam, becomes the sole scale. No one other than the sovereign can restrict the right of the owner . But the citizen has no right to prevent him from doing so. Hobbes' idea of the original state as a thought model and the social contract resulting from it signifies a revolution in legal and political philosophical thinking that influences the discussion up to the present day.

Grotius

For Hugo Grotius , natural law meant that man can recognize the commandments of God, the creator of nature, with the help of “right reason” (rectae rationis). Therefore there are legal rules with all civilized peoples. The right to one's own person is innate , while property is an acquired right. Grotius assumed an original condition with community of property, which dissolved because people no longer lived on the basis of charity . The state was formed through a contract that could also be concluded tacitly.

- “[T] he society has the purpose of using common forces and working together to preserve everyone's own (ut suum cuique salvum sit). Obviously, this would also take place if property (dominium), as we now understand it, were not introduced. Because life, limbs and freedom (vita, membra, libertas) would then also belong to everyone, so that they cannot be attacked by another without unjustly. Likewise, the right of the owner would be (ius (...) esset occupantis) to use the things at hand. "

Grotius stood in the tradition of the theory of occupation, based, like Hobbes, on the idea of the social contract, but equated property with the right of the person to freedom and life. With Grotius, political philosophy was still compatible with absolutism as long as the ruler observed and upheld the rights attached to the person.

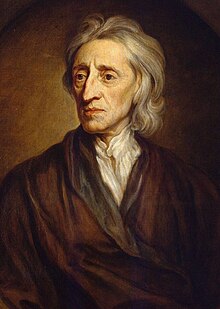

Curl

After the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution (1688), the bourgeoisie in England, despite setbacks, had grown so strong that it was able to enforce the sovereignty of Parliament against the king with the Bill of Rights . The two treatises on the government of John Locke form a pamphlet against the power of the king in favor of the bourgeoisie, written 1680–1682 and published anonymously only in 1690 for security reasons. According to Locke, God has given the world to human beings for common use and "also given them the reason to use it for the greatest advantage and convenience of their lives." (II § 23) Reason commands "that no one else, there everyone." are equal and independent, are supposed to damage one's life and property, one's health and freedom. ”(II § 6) Locke saw the position of property as a fundamental right in a similar way to Grotius or Samuel von Pufendorf . However, property does not arise from a contract, but is based solely on positive natural law.

In the justification of property, Locke went a completely new way with his theory of work. Man is by nature entitled to appropriate a part of nature for the purpose of self-preservation. This also results from the divine instruction to subdue the earth . He fulfills this commandment through work. By working on a natural good, man brings part of himself into the object. Natural goods have little value without work. In nature, water does not belong to anyone, but in a jug it has undoubtedly become property. (II § 29) The value of the land also arises largely through work. (II § 43) The acquisition of property, that is, the appropriation of nature finds its limits where man can no longer consume what nature has gained through work.

- “As much land a person plows, plants, tills, cultivates and as much of the yield he can utilize, that much is his property. Through his work he sets it apart from the common good. ”(II § 32) Contrary to what Marx interpreted later, Locke's labor theory assumes that a free man's own work can also be sold for a certain period of time for wages. (II § 85) This means that the worker becomes the property of another. (II § 28)

In a second step, Locke explained the creation of wealth. Decisive for this are the possibility of exchange and the institution of money. By exchanging the result of the work, for example apples for nuts, people get something less perishable. He is allowed to own this, even if he does not use it directly. This is especially true for non-perishable goods such as gold, silver and diamonds. (II, § 46) Through the money an agreement was reached between the people, according to which the property can be kept indefinitely. The protection of the property thus created has a fundamental function for the formation of the state:

- "The great and main goal, why people form a state and place themselves under a government, is the preservation of their property." (II § 124)

So property already exists before the formation of a state. Accordingly, the state treaty does not mean that the ruler can dispose of the property of his citizens at will.

In contrast to Hobbes, with Locke the natural rights to life, liberty and property bind state power. Interventions in property by the state always require the consent of the citizens. (II § 139) Locke explained the different wealth with different industriousness and different individual requirements of the people.

Locke's labor theory does not contain any justification of the social obligation of property as it was previously demanded by the church fathers, Thomas Aquinas or Grotius. It accommodated the liberal theorists of the subsequent period because economic growth harmonized with it in the developing market economy , while the occupation theory assumed a fixed stock of goods, but had no explanation for their increase and the resulting distribution issues.

Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau had a critical view of property, but considered it indispensable for freedom . The formation of property leads to the fact that the person leaves the original state.

- “The first one who fenced in a piece of land and said boldly: 'This is mine' and found such simple-minded people who believed that became the true founder of civil society. How many crimes, wars, murders, sufferings and horrors would one have spared the human race if he had torn out the stakes or filled the ditch and called out to his peers: 'Don't listen to this deceiver. You are all lost if you forget that the fruits belong to everyone and the earth to none. '”(Discourse, 173)

Rousseau characterized property as the cause of “unrestrained passions”: “Competition and rivalry on the one hand, conflict of interests on the other, and always the hidden desire to make one's profit at the expense of others: all these evils are the primary effects of property and the inseparable wake of emerging inequality ”. (Discourse, 209) On the other hand, he describes property as “the most sacred of all civil rights, in certain respects even more important than freedom itself [...] because property is the true foundation of human society and the true guarantor of the citizens' obligation. "

Due to the increasing industrialization and the effects of absolutism in France, Rousseau was confronted with a significantly greater inequality than before Locke, from whom he adopted some theoretical elements, but also clearly distanced himself from him. He diagnoses: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains” (CS I 1) Rousseau, in contrast to Aquin or Grotius, for example, renounces a teleological “determination” of man through divine or natural law. The amalgamation through a social contract is based solely on the weighing of reason. As a free person, no one will agree to an order that takes away his freedom, as was still possible in the concepts of Hobbes and Grotius. The task is:

- "'Find a form of association that defends and protects the person and property of each individual member with all its common strength and through which everyone, by uniting himself with everyone, obeys only himself and remains just as free as before." That is the fundamental problem, the solution of which is the social contract "(CS I 6., p. 18)

Possession, which can only be secured through individual violence, becomes a right in the social contract that is limited, but which in the bourgeois state is free from the arbitrariness of others, i.e. civil freedom is only granted.

- “What man loses through the social contract is his natural freedom and an unlimited right to everything he longs for and what he can achieve; what he receives is civil liberty and ownership of all that he has. In order not to be mistaken in this balancing act, it is necessary to clearly distinguish natural freedom, which finds its limits only in the strength of the individual, from civil freedom, which is limited by the common will , and property, which is only one The consequence of the strength or the right of the first owner is that of property that can only be based on an explicit title. "(CS I 8)

Rousseau justifies the creation of property in a similar way to Locke on the basis of work: “Only the work that gives the farmer a right to the product of the field that he tilled gives him a right to the land, at least until the harvest, and so from year to year - which, since it creates uninterrupted possession, easily turns into property. ”(Discourse, 203) Property is therefore not an original, but an acquired object. The original owner is the community, which only allows the citizen to own it. (CS I 9, pp. 23-24) This requires a justification:

- “In order to justify the right of first ownership of any piece of land, the following conditions are generally required: First, that this area has not yet been inhabited by anyone; second, that one only takes as much property as one needs to subsist ; and thirdly, that one does not take possession of it through an empty ceremony, but through work and cultivation , the only property that must be respected by others in the absence of legal titles. "(CS, III 369, I 9)

In the republican state of Rousseau, civil liberty is limited by the common good. Correspondingly, a democratic decision can intervene in the distribution of income and progressive taxes can create greater distributive justice .

- “He who only has what is simply necessary does not have to contribute anything; the taxation of those who have superfluous things can, in an emergency, go up to the sum of what exceeds what is necessary for them "

Paine

The book "Common Sense" by Thomas Paine from 1776 contributed significantly to the American independence movement and influenced the Declaration of Independence of the United States of July 4, 1776. Paine called for a constitution analogous to the Magna Carta . “Freedom and property, but above all the free exercise of religion according to the dictates of conscience, must be secured for all people.” In the text “Rights of Men” he rejected any form of slavery: “Man has no property People, any generation still has ownership of the following generations. "

Paine made a distinction between natural rights that humans have because of their existence and civil rights that they confer on society under the constitution. Through this transfer, every citizen becomes the owner of the company and is entitled to its benefits ("rightly draws on the capital") In a text proposal for the French National Assembly, he formulates:

- “The preservation of the natural and non-statute-barred human rights is the ultimate purpose of all political associations; these rights are freedom, property, security and resistance to oppression. ”And:“ Since the right to property is inviolable and sacred, no one can be deprived of it unless the public, legally established need so requires and under the Condition of a fair and predetermined compensation. "

For Paine, monarchical governments emerged from robbery and violence and derive their legitimacy from this. Therefore he rejects a hereditary monarchy in principle: "A hereditary crown, a hereditary throne or whatever fantastic name one may give the thing, allows no other interpretation than that people are inheritable property."

Paine continues to polemic against the interests of the House of Lords :

- "For the same reasonable reason you could make a legislative house entirely of people whose business is renting out real estate, you could also make one of tenants, or bakers, brewers, or any other class of citizens."

According to Paine, property or taxes should not be a criterion for giving someone the right to vote: “When we consider the number of ways in which property can be acquired without merit or lost without crime, we should consider the idea of making it a criterion of rights, spurn. "

French Revolution

Much as Locke is credited with influencing the American constitutions, particularly the Virginia Bill of Rights of 1776, Rousseau's writings influenced the French Revolution . Article 17 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 states:

- "Since property is an inviolable and sacred right, it cannot be deprived of anyone unless it is clearly required by the public necessity established by law, and just and prior compensation is given."

This liberal idea of property rights was enforced by smashing the privileges and the traditional property rights of the clergy and the nobility , and the third estate freed itself from the burden of feudal rights. The private property of the clergy and many noble families was confiscated, the upper ownership of the king and the nobility was abolished and feudal power structures were smashed. The French Revolution thus fought for civil property rights as an expression of individual freedom at the expense of the property rights of the previously privileged classes.

Robespierre took Rousseau's position in a well-known speech on property, but also stressed that regardless of the poor, the constitutional article on property seems to favor the "rich, speculators , usurers and tyrants ". His proposal to amend the constitution, although not implemented, read:

- “Article 1 - Property is the right of every citizen to freely dispose of that part of the property that is guaranteed to him by law.

- Article 2 - The right of property, like any other right, is limited by the obligation to respect the rights of one's neighbor.

- Article 3 - Property must not affect the security, freedom, existence or property of our fellow human beings.

- Article 4 - Any property or trade that violates this principle is unfair and immoral. "

Hume

The skeptic David Hume explained the transition from the natural state to the rule of law with reference to Cicero and explicitly against Hobbes from historical practice as an evolutionary process. Accordingly, he interpreted the creation of property as a social and psychological process. Property is the expression of scarcity and habituation. When someone has owned an object for a long time, familiarity and a sense of possession arise. Laws are the legalization of social practice in the state, whose task it is to ensure justice through the protection of freedom and property. Laws about property must not be arbitrary, but must reflect human life. Complete equality is destructive.

The institutions of property and inheritance are designed to promote useful customs and skills in society, enliven trade that increases wealth, and are based on trust that promises will be kept. By stating that nature knows neither mine nor yours, Hume opposed Locke. Analogies to the establishment of property are not valid. On the one hand, property arises from original possession. Second, from long-term possession as common law . Civil law regulations are aimed at expediency. This includes the rules of inheritance and contract as the only permissible ways in which property, once acquired, can be transferred.

Kant

Immanuel Kant's property theory is systematically integrated into his moral philosophy, so it is based on the categorical imperative and is carried out in the first part of the Metaphysics of Morals , in the Metaphysical Foundations of Legal Doctrine . To determine property, Kant distinguished between the internal and external "mine and yours". The inner mine and yours is the right to one's own person, which is expressed in freedom and exists by nature. Characteristics of the inner mine and yours are equality, self-possession, innocence and freedom of action . Property as the external mine and yours does not exist from nature, but is acquired, because it requires the consent of another, because property affects the other's sphere.

- "What is legally mine (meum iuris) is that with which I am so connected that the use that another would like to make of him without my consent would harm me." (RL, AA VI 245) Property differs from sensual possession by being an intelligible property that can only be imagined by the mind.

It is theoretically possible to regard any external object as property; for otherwise “freedom would deprive itself of its arbitrary use of an object by setting usable objects beyond all possibility of use.” (RL, AA VI 245) According to Kant, the first acquisition is therefore an occupation, a possession , in such a way that something is declared property on the basis of an arbitrary act. However, this is only a theoretical consideration, a thought model. Kant was not interested in the empirical origin of property. For property rights, it is irrelevant whether an item is in physical possession or whether it is necessary for self-preservation. It is crucial that a physical act, be it the first grasping, be it the formation through work, per se does not justify a right against another person. If one declares an object to be mine, this means "imposing an obligation on all others that they would not otherwise have." (RL, AA VI 247)

The right to property thus also includes the restriction of the rights and freedoms of all other people. Therefore, no object can become property without the consent of all others. What is needed is the mutual imposition and recognition of duties , an " a priori united will of all". (RL, AA VI 223) Property is therefore primarily not a relationship to a thing, but rather expresses a relationship between people. Things as such are incapable of any liability; they have no rights. Kant did not recognize the arguments for the establishment of property through work alone.

- "When it comes to the question of the first acquisition, the processing is nothing more than a sign of possession, which can be replaced by many others that require less effort." (RL, AA VI 265) The working theory going back to Locke is based on a "secretly prevailing deception to personify things and as if someone could make them binding through work related to them, not to serve anyone other than him, to think of a right against them directly;" (RL, AA VI 269)

Because property, as an expression of freedom, excludes others from the power of disposal , a right is required with which one can enforce the claim. “So there can only be an external mine and yours in a civil state.” (RL, AA VI 256) Property without state authority is only provisional . Property is not legitimized if it restricts others in their freedom without their consent, so that it is "not determined by any public (distributive) justice [distributive justice] and is not secured by any power exercising this right." (RL, AA VI 312) From this it follows that the formation of property necessarily leads to a republican state. Property as a result of the law of common sense can be shaped through due process in a republican state. It becomes a “bundle” of positive rights and duties.

Modern

At the turn of the 19th century, following the USA and France, a number of states adopted a republican constitution based on fundamental rights . In Prussia , peasant bondage was abolished in state domains in 1799 . With the Prussian reforms of 1807, the ministers Stein and Hardenberg laid the basis for personal freedom and free property through the edict on the liberation of the peasants . In a number of countries, civil law has been adapted to new needs on the basis of Roman law (law of reason ). This corresponded to the desire of the liberal movement for greater legal security and limitation of the decrees of the ministries. However, the free rights of disposal over property formulated therein did not mean the abandonment of the social connection of property. Rather, the common good of property was retained in a large number of public law regulations (tenancy law, forest law, neighborhood law, etc.).

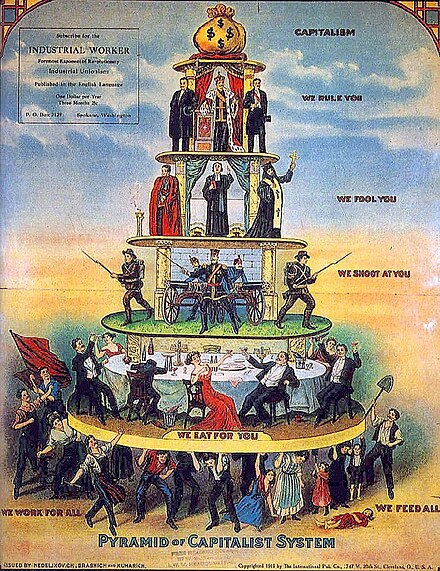

The advancing industrialization created a workforce in the cities that worked in factories , but also in mines and large metal processing companies. Inadequate social conditions led to a pauperization of increasing parts of the population and the emergence of the social question . The feudal class society developed into a class society in which ownership of the means of production made a significant impact on one's position in society. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that social legislation began and has been progressing since then gradually reducing the conflict situation between the haves and the haves in the western industrialized countries, and with increasing prosperity people began to talk more about classes and later also about milieus . A broader middle class emerged, which in turn formed wealth and property.

In Russia, on the other hand, the revolution of 1917 led to the formation of a socialist state in which ownership of the means of production was suppressed. In addition, after the Second World War the Soviet Union expanded its sphere of influence to include a number of Eastern European countries and the People's Republic of China was established . These forms of government, which were based essentially on state property , were also associated with considerable restrictions on individual freedom and ultimately could not prevail against the open societies of the western industrialized countries.

In addition to the property right, which only relates to physical objects, the rights to intellectual creations, the so-called intellectual property , have been gaining in importance since industrialization . At the present time, this applies beyond the question of copyright law to the ownership of natural processes in genetic engineering or of immaterial goods such as software.

The economic dynamism that set in with the liberalization of the markets also shifted theoretical discussions about property. Already in the second half of the 18th century there were vehement critics of the property structures with the early socialists . The philosophers of German idealism , Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel , deviated from liberalism and assigned the state a constructive role in civil society. The exclusively liberal state in the sense of Locke, Adam Smith , Jean Baptiste Say or David Ricardo is an “emergency and intellectual state” (Hegel, Grundlinien , § 183). In this, on the one hand, there is an "accumulation of wealth" (§ 243), on the other hand, through the "sinking of a large mass below the level of subsistence", the feeling of "right, justice and the honor of surviving through one's own work" , lost. (§ 244) For Hegel, the state combines morality and law at the highest level and is thus the “reality of the moral idea”. Its function is therefore not only to secure the realization of interests and freedom, but also to limit and coordinate the individual freedoms in the state community. While Fichte conceived a highly dirigistic state to establish distributive justice, Hegel hardly had any socio-political consequences. The critical reaction of the anarchists ( Pierre-Joseph Proudhon , Mikhail Alexandrowitsch Bakunin , Pjotr Alexejewitsch Kropotkin ) and especially the communists around Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels , whose social counter-concept called for the abolition of property, was quite different .

In the first 70 years of the 20th century, there were no fundamentally new theories of property, but a more differentiated view. Liberalism finds its counterpart in utilitarianism , in welfare economics or in the Austrian school . In sociology, Max Weber , Bourdieu and Luhmann examine the function of the institution of property and work out the connection between social power and wealth. Only the Theory of Justice (1971) by John Rawls triggers a new debate in political philosophy in which the question of property is discussed in connection with (social) justice. The moderate " egalitarian liberalism " of Rawls is contrary to both liberals ( Robert Nozick , James Buchanan ) and by the oriented to the common good communitarianism . Similar to Rawls, Catholic social teaching and the empowerment approach mediate between individualism and collectivism. In economics, the influence of property on economic activity is particularly emphasized by the New Institutional Economics.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the dispute over the question of property has turned more into a question of distributive justice and the permissible scope of private property. Labor law, co-determination, tenancy law, environmental legislation and public control represent clear barriers to the power of disposal over property. In the discussion between egalitarianism and liberalism , property and the basic principles of social legislation are mostly assumed.

Early socialists, cooperative members and others critics of private property

At the end of the 18th century, criticism of the developing capitalist conditions began. The social philosopher William Godwin called for an even distribution of property. Thomas Spence campaigned for the socialization of the property. William Thompson criticized the fact that the distribution of ownership of the means of production prevented workers from enjoying the fruits of their labor and suggested cooperative solutions. The British entrepreneur Robert Owen is counted among the early socialists . At first he carried out important social reforms in the inherited New Lanark cotton mill and called for the means of production to be socialized. He tried to implement his utopian model in the experimental, cooperatively organized community settlement (“New Harmony”). Important French early socialists were Henri de Saint-Simon , founder of the influential school of thought of Saint-Simonism named after him and pioneer of Catholic social teaching, and Charles Fourier , who in his writings called for the economy to be organized on a cooperative basis while at the same time developing new forms of libertarian life . Romantic philosophers, such as Franz von Baader , also criticized the social situation of workers. In the USA, advocates of the idea of equality such as the labor leader Thomas Skidmore ( The Rights of Man to Property , 1829) or the radical liberal Orestes Brownson ( The Laboring Classes , 1840) called for a confiscatory inheritance tax because everyone should have the same starting position from birth.

Spruce

In the subject philosophy elaborated by Johann Gottlieb Fichte , the individual's right to self-determination is emphasized even more than in his predecessors Locke and Kant:

- “We are our property: I say, and I assume something twofold in us: an owner and a property. The pure I in us, reason, is the master of our sensuality, of all our mental and physical powers; she may use them as a means for any purpose. "

In an early work in 1793, Fichte followed the theory of work unreservedly, according to which the formation of form represents submission to one's own purposes: "This formation of things under one's own strength (formation) is the true legal basis of property."

A few years later he emphasized in the text "Basis of Natural Law" that it is part of the essence of man to live together. Therefore, the "principle of legal assessment" reads:

- "Everyone restricts his freedom, the scope of his free actions through the concept of freedom of the other, (so that the other, as free at all, can exist.)"

The reason for property is no longer work, but the right to one's own person, through which someone naturally determines an object (as an original right) for his own purposes. The natural relationship of property results solely from the relationship of the rational subject to an object. Limiting the right to property means limiting the right to freedom of a subject. This is only possible with the consent of the subject. Subsequently, Fichte developed a three-stage contract theory based on the property contract. Second, it is agreed that the law can also be enforced. In the third stage, the right to enforce is finally transferred to the state.

The original right to one's own person enables people to influence the objective world through their actions. To be free means to be in control of your actions. Fichte therefore does not see property as a right to an object, but as a right to act. The limit of freedom determines the limit of property ownership. Real estate, for example, arises from power. The limit is the extent to which the state allows the use of land. This means that several people can have ownership of an object.

With this action-oriented concept of property, Fichte anticipated the fundamental ideas of the theory of rights of disposal . The action-theoretical dimension of property, as sketched by Fichte, can also be found in the case law of the Federal Constitutional Court together with the labor theory term Lockes: “Within the framework of fundamental rights, property has the task of ensuring freedom for the bearer of the fundamental right in the area of property law and thus to enable him to shape his life independently (BVerfGE 24, 367 [389]). The guarantee of ownership complements the freedom of action and design (BVerfGE 14, 288 [293]), in that it primarily recognizes the stock of assets acquired through their own work and performance. "( BVerfGE 30, 292 [334])

From man's original right to his personality and freedom it follows at the same time that he has a non-relinquishing right to his own existence: "Being able to live is the absolute inalienable property of all people." the transfer of the security of life: "It is the principle of every reasonable state constitution: Everyone should be able to live from his work." From this, Fichte concluded that the state has the task of ensuring the subsistence level of the individual:

- “Everyone owns his civil property only insofar and on the condition that all citizens can live on theirs; and it ceases to the extent that they cannot live, and it becomes their property. "

According to Fichte, the poor person has a statutory right to such support. In return, the state can monitor “whether everyone in his sphere works as much as is necessary to live.” On this basis, Fichte later developed detailed proposals for the establishment of distributive justice by the state in the “commercial state” and other writings would lead to the cessation of foreign trade and a state-socialist planned economy .

Hegel

In the basic lines of the philosophy of law , Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel described property as an end in itself, which is an expression of the outer sphere of freedom. (§ 41) For him, the power of disposal made the difference between property and possession:

- "The side, however, that as free will I am in possession of an objective and only hereby real will, constitutes what is truthful and legal in it, the determination of property." (§ 45)

He made a distinction between common property and private property, a term he coined. Private property has priority.

- “The idea of the Platonic State contains the injustice against the person, being incapable of private property, as a general principle. The idea of a pious or amicable and self-enforced fraternization of people with a community of goods and the banishment of the private property principle can easily be presented to those who misunderstand the nature of freedom of spirit and justice and do not grasp it in its specific moments. "(§ 46).

However, Hegel saw the possibility that objects of property “must be subordinated to higher spheres of law, a community, the state”. (§ 46) He rejected demands for fair distribution and minimum standards of care because they could not be justified objectively:

- “One cannot speak of an injustice of nature through the unequal distribution of property and property , because nature is not free and therefore neither just nor unjust. That all people should have their livelihood for their needs is partly a moral and, expressed in this vagueness, well-intentioned, but, like the merely well-intentioned in general, nothing objective; partly livelihood is something other than property and belongs to a different sphere , civil society. "(§ 49)

Originally, according to Hegel, property arose partly through "taking possession", through "direct physical seizure", "formation" or "mere designation". (§ 54) The shaping through work is "the most appropriate taking of possession of the idea because it unites the subjective and the objective". (§ 56) In a developed society, the forms of original appropriation largely disappear. The acquisition of property takes place according to positive law by contract.

- “Just as right in itself becomes law in bourgeois society, so too does the direct and abstract existence of my individual law, which has just been transposed into the meaning of being recognized as an existence in the existing general will and knowledge. The acquisitions and actions of property must therefore be undertaken and endowed with the form which that existence gives them. The property is now based on a contract and on the formalities that make the same of evidence capable and legally binding. "(§ 217)

A special feature of Hegel is that he spoke on the question of intellectual property.

- "Knowledge, sciences, talents, etc., are of course peculiar to the free spirit and an internal part of it, not an external one, but just as much it can give them an external existence through expression and alienate them (see below), whereby they come under the determination of Things are set. So they are not first something immediate, but only become so through the mediation of the spirit, which reduces its interior to immediacy and exteriority. "(§ 43)

The mental achievement that a person acquires is first of all part of the inner personality. Property only arises when it is transferred to the external world, not through the work itself, but through labeling as one's own. Hegel thereby distances himself from the widespread theory that intellectual property is based on work. Copyrights can be partially released for use and yet remain essentially the property of the author. Copyright serves in particular to promote intellectual achievements:

- “The merely negative, but very first advance of the sciences and arts is to secure those who work in them against theft and to allow them to protect their property; how the very first and most important promotion of trade and industry was to secure it against robbery on the highways. "(§ 69)

Proudhon

The anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was best known for the catchphrase “property is theft”. In his book “What is property? Investigations into the foundations of law and rule ” (1840) he criticized the traditional theories about property as a prerequisite for income without work :

- Property is not based on natural law because many are excluded from property and it is the subject of constant social conflict. There is no substantively acceptable justification for the transition from the original common property to civil individual property.

- The first occupation is no justification for property, because if the number of the population increases, this division would have to be carried out again, otherwise the distribution would be unjust.

- Invested labor does not lead to property, because the fruits of labor (for example the harvest) are not to be equated with property itself (land, means of production).

- The established civil law gives no justification for property because it cannot name a cause.

Both the theory of occupation and the theory of work initially assume equality. But property has the property that it leads to inequality. Therefore Proudhon's basic thesis is: "Property is impossible because it is the negation of equality."

Proudhon is particularly critical of the fact that one can profit from property without doing anything. However, value is created solely through work. Profits that are not based on work therefore represent an exploitation of people by people. Cooperation creates higher added value than the sum of the individual actions. The capitalist takes advantage of this by not passing on the cooperation agreement but keeping it. That is why ownership of the means of production leads to unjust enrichment. Property is rigid through inheritance and distributed in support of the hierarchical order. Greater justice is obtained if one distributes property evenly and adjusts the distribution to the prevailing circumstances. He therefore suggested that the ownership of the land should be left with the municipalities as superior ownership and that it should be given to smaller tenants for a limited period.

Much less radical than the Marxists, he turned against their communism:

- “Communism is inequality, but in the opposite sense than property. Property is the exploitation of the weak by the strong; Communism is the exploitation of the strong by the weak. "

According to Proudhon, communism primarily endangers freedom. He saw the solution in a society that is organized according to the principle of reciprocity ( mutualism ). There is no central government there and the only obligation is to comply with treaties. In doing so, he primarily had “voluntary workers' associations” in mind, which form a self-administered “federal” property. The demand of other anarchists such as Bakunin or Kropotkin for the collectivization of land and means of production cannot be found in Proudhon. In his polemic against Proudhon, “ The Misery of Philosophy ” , Karl Marx criticized him as a “petty-bourgeois ideologist” who neglected the historical dimension in particular.

Marx

For Karl Marx, property was originally common property:

- "Because the human being does not originally face nature as a worker, but rather as the owner, and it is not the human being, qua single individual, but rather, as soon as one speaks to some extent of the human existence of the same, tribal person, horde person, family person, etc."

Marx's criticism was primarily aimed at ownership of the means of production, not personal property.

- “Private property, in contrast to social, collective property exists only where the equipment and the external conditions of work belong to private people. Private property has a different character depending on whether these private individuals are workers or non-workers. "

For Marx, property has historically been the instrument that established the relationships of power. So the father, who has regarded the family as property since primitive society, the slave owner the slaves, the landlord the serfs in feudal society, so also the capitalist the dispossessed worker in capitalism.

Capitalist society is preceded by a process of transformation from feudalism :

- “The process that creates the capital relation can therefore be nothing else than the process of separating the worker from property in his working conditions, a process that on the one hand transforms the social means of life and production into capital and, on the other hand, transforms the direct producers into wage laborers. So- called original accumulation is nothing but the historical process of separating producer and means of production. It appears as "original" because it forms the prehistory of capital and the mode of production corresponding to it. "

Marx described this prehistory as the violent repression of feudal rule by capitalism .

- "The immediate producer, the worker could have his person only after he had left off, tied to the soil and another person serf or hearing to be. In order to become a free seller of labor who carries his goods wherever there is a market, he also had to have escaped the rule of the guilds, their apprenticeship and journeyman regulations and restrictive work regulations. [...] The industrial capitalists, these new potentates , for their part had to displace not only the guild master craftsmen, but also the feudal lords who were in possession of the sources of wealth. From this point of view their rise presents itself as the fruit of a victorious struggle against feudal power and its outrageous prerogatives as well as against the guilds and the fetters that they put on the free development of production and the free exploitation of man by man. "

In bourgeois society, property is the cause of the alienation and exploitation of the worker: “Capital has agglomerated the population , centralized the means of production and concentrated property in a few hands. The workers, who have to sell themselves piece by piece, are a commodity like any other article of trade and are therefore equally exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition and all fluctuations in the market. "

Marx and Engels therefore saw communism primarily as a project for the "abolition of private property".

In addition, Marx opposed the linking of the concepts of freedom and property. The traditional liberal concept of freedom, as represented by Locke or Smith , includes the freedom of the possessing citizens, the bourgeoisie , but not the freedom of the citizens (citoyen). This egoistic freedom is based on the interests of the capitalists.

- “The freedom of the egoistic person and the recognition of this freedom is rather the recognition of the unrestrained movement of the spiritual and material elements, which form the purpose of his life. Therefore man was not freed from religion, he received religious freedom. He was not released from property. He received freedom of property. He was not freed from the selfishness of trade, he was given freedom of trade. "

According to Marx, freedom only arises in a community when everyone has the means “to develop their talents in all directions. […] In the real community, individuals gain their freedom in and through their association [union] at the same time. ”Freedom does not offer a state-free individual sphere, but participation in the community in which there is no longer any ownership of the means of production.

Weber

The sociologist Max Weber viewed property from the perspective of social relationships , which he described as "open" when nobody is prevented from participating in social activity . If, on the other hand, this participation is restricted or subject to conditions, he spoke of “closure”. A closure always takes place when those involved expect an improvement in their chances of satisfying their needs. A closure inwards, that is, within a group, is what Weber called Appropriation . For him, rights were therefore an appropriation of opportunities.

- "Chances appropriated hereditary to individuals or to hereditary communities or societies should mean: 'property' (of individuals or communities or societies), externally appropriated: 'free property'."

Ownership is thus an instrument for regulating procurement competition. This restricts the power of disposal over goods.

Kelsen

Even for the prominent representative of systematic legal positivism , Hans Kelsen , there was no natural law, but only legal rules that arose in the course of social development. For Kelsen , the theory of subjective law had an ideological function that primarily had the purpose of protecting the rule of the haves. By institutionalizing property as a right in rem, i.e. related to a thing, the fact that it has a social effect is obscured by excluding others from using a thing.