German minority in Poland

The German minority in Poland is since 1991 recognized national minority in Poland , whose rights by the Constitution of the Republic of Poland are guaranteed. The settlement area of these Germans is mainly in Upper Silesia between the cities of Opole (German Oppeln , Silesian Uppeln ) and Katowice (German Kattowitz , Schlonsakisch Katowicy ). There they make up 20 to 50 percent of the population in several municipalities, the center with most members of the minority is in the Opole Voivodeship . The German language is widespread there and in the Silesian Voivodeship , but nowhere in Poland is German a language of everyday communication. The predominant domestic or family language (colloquial language) of the German minority in Upper Silesia is Silesian (Polish dialect) or Silesian (German dialect) .

The German minority takes part in elections with an election committee and is represented in politics and administration. In the municipalities with at least 20 percent German population, German is the second official language and the place names are given in German.

With the results of the censuses of 2002 and 2011, in which the population was personally interviewed, the first figures on the German minority in Poland were available. In 2011, the number of people who only stated a German nationality was around 45,000 (which, however, has so far been based on an extrapolation). 103,000 people indicated another nationality or ethnicity in addition to the German, the majority of them Polish. The total number of 148,000 people comes close to the result of the 2002 census, in which 152,897 people of German nationality were recorded. At that time, however, only one nationality or ethnicity could be specified. In addition, 5,200 people in Poland were exclusively German and 239,300 people were Polish and German.

At the time of the 2002 census, the two largest organizations of the German minority, the SKGD in Opole and the SKGD in Katowice , had a total of around 239,000 members; in 2008 there were only around 182,000 members.

According to the German Embassy in Warsaw , the German minority estimates their number between 300,000 and 350,000 people.

history

Until the 1st partition of Poland (1772)

After the Great Migration, the historical regions of Silesia , East Brandenburg and Pomerania were settled by Slavic tribes. In the High Middle Ages , the German East settlement began in these regions ; the autochthonous Slavic population or, in the case of East Prussia, the Baltic population ( Prussia ) was assimilated linguistically and mostly also culturally in the course of a few centuries, and in some cases completely ousted. Family and place names that end in -ski, -itz, -lau, -ow and sometimes also -a are evidence of a Slavic origin. In Masuria and Upper Silesia , a mixed culture with the Masurian and (German-Slavic) Silesian language and local customs was able to establish itself as integrative features.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, numerous Lutheran German left in hauländer -Dörfern along the Vistula down and their tributaries.

Poland divided (1772 to 1918)

In the years 1772, 1793 and 1795 the dual state of Poland-Lithuania was divided between the neighboring powers Russia , Austria and Prussia .

In the Russian part there were significant German-speaking parts of the population in the regions of Courland , Lithuania and Volhynia .

In the Austrian part ( Galicia ) the proportion of Galician Germans and Jews increased during this time. As a traditional multi-ethnic state, Austria at the time was very tolerant of the different ethnic groups and religions, which relativized the disproportionate German-speaking influence in the military, administration and education. Due to the Prussian expansion, there were repeated armed conflicts between the two German powers Austria and Prussia, also around Silesia .

In the 19th century, after the partitions of Poland , the Germans took part in the expansion of cloth production in Greater Poland .

From 1880, the German Empire pursued a more stringent Germanization policy in divided Poland . According to Bismarck, the creation of the “Prussian Settlement Commission” was intended to create a “living wall against the Slavic flood”. In the course of the emigration of large parts of the population from the economically weak eastern parts of Prussia (referred to as eastward flight ), Germans settled in the province of Posen.

Over 3000 places in the former part of Poland, which today belongs to Ukraine , also had German residents. Many Germans in particular stayed in Volhynia after the First World War .

Second Polish Republic (1918 to 1939)

After the establishment of the Second Polish Republic in 1918, large numbers of Germans were forced to leave the country; This mainly affected Germans in the territory of the Polish corridor , i.e. in the Pomeranian Voivodeship (which until 1938 included all parts of the former West Prussia that had become Polish ) and almost the entire former Province of Posen (from 1919 the Posen Province ).

Before the Second World War , the majority of Germans in Poland lived in the Polish Corridor , in the area around Posen and in Eastern Upper Silesia , which was ceded to Poland in 1922 as the Autonomous Silesian Voivodeship , and also in the region around Łódź (Lodsch) and Volhynia . Around 250,000 Germans had settled in Volhynia by 1915.

Politically, the Germans in Poland organized themselves in a large number of parties that were represented both at national level in the Sejm and Senate and in the Silesian Parliament in the Silesian Autonomous Voivodeship .

In the Polish National Constituent Assembly (1919–1922) Germans were represented by the German People's Party , the DP Association and the ZAG and a total of eight members.

In the Sejm from 1922 onwards, it was primarily the Deutschtumsbund to protect minority rights (or, after their ban, the German Association in the Sejm and Senate for Posen, Netzegau and Pomerania), the Catholic People's Party , the German Socialist Labor Party of Poland (DSAP) and the Germans Party that could unite the votes of the German minority. For central Poland, the German People's Association was represented in Poland in the Sejm and Senate.

The strongest political association of the German minority in the 4th and 5th electoral terms of the Sejm (1935 to 1939) was the Young German Party in Poland , which was founded in 1931 and had around 50,000 members in the mid-1930s. The other parties (apart from the DSAP, which (unsuccessfully) drew up a joint list with the Polish PSP ) were merged in the Council of Germans in Poland (RDP).

With the help of a few ethnic Germans, Amt II of the Security Service of the Reichsführer SS (SD) created the special search book for Poland with around 61,000 names of Poles from May 1939 . The people named in the book were either to be arrested or shot after the occupation of Poland .

Second World War (1939 to 1945)

At the beginning of World War II occurred in Bromberg to pogroms against " ethnic German " in which to 8 September 1939, 400 members of the German minority were killed by the third. The Bromberg Bloody Sunday played an important role in Nazi propaganda , among other things, the number of victims was intentionally multiplied. For a long time, the causes and the number of victims were hotly disputed between Germans and Poles. There are now more differentiated studies.

After the attack on Poland in 1939, the Volksdeutsche Selbstschutz was founded , a paramilitary organization that mainly recruited its members from members of the German minority and was involved in numerous mass murders of the Polish and Jewish population. Of the roughly 740,000 members of the German minority in pre-war Poland, men of military age were recruited as soldiers; in addition, around 80,000 to 100,000 belonged to the Volksdeutsche Selbstschutz.

After the attack on Poland (and later the attack on the Soviet Union ), the interpretation and the situation of the German minority in the area under the control of the Third Reich changed fundamentally. It was declared a racially superior Aryan population group, whereas the Polish (Slavic and Jewish) ruling class living there until then systematically murdered Poland by the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD and the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz as part of the Tanneberg company and the AB-Aktion on the basis of the special wanted list were. As part of the General Plan East , the local plan established the procedure for the settlement of ethnic Germans. The Umwandererzentralstelle ("Office for the Resettlement of Poles and Jews") was responsible for the expulsion of the original inhabitants, the Main Trustee East or the "Treuhandstelle für den Generalgouvernement " for the utilization of the property left behind, and for the resettlement of ethnic Germans under the propaganda term " Heim ins Reich “the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle .

Corpses of dead ethnic Germans, Bydgoszcz Blood Sunday , 1939

Polish teachers are brought to execution by the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz in Death Valley near Bromberg, 1939

Expulsion of Poles from Wartheland in 1939

“Moving” of Jews to the Litzmannstadt Ghetto , Wartheland, March 1940

In March 1941 the "Ordinance on the German People's List and German Citizenship in the Integrated Eastern Regions" was issued. In it, people in four categories were assigned to the German nationality, each with graded rights:

- Volksliste 1: Confessional Germans who had campaigned for the German nationality in Poland even before the attack on Poland.

- People's list 2: People who had stuck to their German origin and culture without having been a member of a minority organization.

- People's list 3: "Tribal Germans" who no longer spoke German and certain minorities (including Kashubians , Masurians , Schlonsaken )

- People's List 4: Renegades who were of German descent, but “slipped into Poland”.

The German Reich generously included people in the people's list as they helped to increase the number of conscripts. The inclusion in the people's list was also seen as an opportunity to escape disenfranchisement and deportation. In contrast to the Polish population or the unregistered people, they could keep their property or get it back; they received better ration cards, were entitled to German social benefits, and their children were allowed to go to school. Members of group 3 were also conscripted, while members of group 4 were not.

After the liberation of Poland, these people were viewed and treated as collaborators by the Polish side . In the Federal Republic of Germany these people and their descendants, who were initially admitted to the occupation zones (with the exception of the French zone), were recognized by courts as having German nationality, so that they were accepted into the Federal Republic as repatriates .

Westward displacement of Poland - flight, displacement and resettlement

At the Tehran Conference from November 28 to December 1, 1943, the heads of government of the main allies Roosevelt , Churchill and Stalin decided, without the participation of Polish representatives, the " Polish shift to the West " and the resettlement of the Polish population from eastern Poland, which was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939 . To compensate for the loss of Polish territory, it was agreed to occupy German eastern territories, which were to be placed under Polish administration. This led to the expulsion of the German population from the East German areas east of the Oder-Neisse line .

In retaliation for the atrocities perpetrated by Germans in World War II, expellees and ethnic Germans and Reich Germans who remained in Poland were often subjected to acts of violence. In former prisoner-of-war and concentration camps , such as in Łambinowice , Zgoda or the NKVD camp in Toszek , civilians were interned because of their German origin or for the purpose of later resettlement. Abuse of camp inmates and the poor conditions in prison resulted in numerous deaths.

After about 8.5 million Germans had fled or expelled from this area between 1944 and 1950, a large-scale " de-Germanization " (Polish odniemczanie ) began in the former German eastern areas , in which an attempt was made to erase all references to the German past . German-language inscriptions on buildings, cemeteries or monuments were made unrecognizable, German (family) names were Polonized and the use of the German language in public was prohibited. The remaining Germans lived mainly in rural areas in Upper Silesia and Pomerania as well as the Lower and Upper Silesian industrial areas . In addition to the settlement of Polish repatriants and new settlers, long-established residents ( autochthons ), especially Upper Silesians and Masurians , were allowed to remain as Polish citizens after positive “verification”. In this way, from 1951, according to false information from the Polish authorities, there were no longer any Germans in Poland and the actual remaining German population was suppressed, which, however, was denied externally.

In Upper Silesia alone, more than 700,000 Germans lived after the Second World War, making up half of the population. According to the 1950 census, there were still 84,800 former Reich citizens living in Lower Silesia (Breslau Voivodeship) . They lived mainly in the hard coal area around Waldenburg , where they were needed as skilled workers for industry and were therefore held back. Since they were supposed to leave the country after a transition period, German organizations and German-language classes were permitted here.

In the rest of Poland, in view of the forced assimilation and discrimination of people of German origin, a cultural development of the German minority was impossible and their long-term existence was endangered.

From 1955 to 1959, families reunited for the first time between those who had fled or were displaced at the time and the Germans who remained in Poland. Around 250,000 Germans were relocated to West Berlin and around 40,000 to the GDR . The number of the German-speaking population was less than 50,000 in 1960.

Further Germans left the country due to a renewed family reunification as a result of the " Warsaw Treaty " of 1970. According to Polish statistics, there were around 500,000 to 1 million people willing to resettle at the end of the 1970s, who emigrated en masse, especially in the 1980s. In the years between 1950 and 1989, a total of around 1.2 million people from Poland came to the Federal Republic of Germany as repatriates under the Federal Expellees Act .

Legal recognition and infrastructure

At the beginning of the 1950s, the Germans living in Poland were mainly seen as indispensable workers, legal discrimination ended and around 250,000 Germans were recognized as a minority in the Oder-Neisse areas. Since family reunification was made possible from 1955 through the mediation of the Red Cross, more and more emigration took place, which undermined the cultural life of the German minority: Poland stopped promoting German cultural policy in 1960 and was the only country under Soviet rule to deny it until 1989 Existence of a German minority.

As a result of the prohibition of German language and culture and the discrimination against people of German origin, everything German had disappeared from public life - many people of German origin in the post-war generations no longer spoke their German mother tongue as their first language. Therefore, the rebuilding of the public activities of the German minority turned out to be difficult after the fall of the Wall and was largely carried out by members of the older generation.

Only after the conclusion of the German-Polish Neighborhood Treaty of June 17, 1991 did the German minority receive full rights as a national minority according to the CSCE standard and a representation in the Polish parliament (Sejm) .

The majority of the German minority in Poland are long-established Silesians of German descent who have declared themselves Germans in statistical surveys.

According to the Polish Minorities Act of 2005, municipalities with a minority share of at least 20% can be officially recognized as bilingual and can introduce German as a so-called auxiliary language. The results of the Polish census from 2002 are used, according to which 28 municipalities have this proportion of Germans in the total population: Biała / Zülz , Bierawa / Birawa , Chrząstowice / Chronstau , Cisek / Czissek , Dobrodzień / Guttentag , Dobrzeń Wielki / Groß Döbern , Głogówek / Oberglogau , Izbicko / Izbicko , Jemielnica / Himmelwitz , Kolonowskie / Kolonowskie , Komprachcice / Komprachcice , Krzanowice / Kranowitz , Lasowice Wielkie / lasowice wielkie , Leśnica / Leschnitz , Łubniany / Gmina Łubniany , Murów / Murow , Olesno / Rosenberg OS , Pawłowiczki / Pawlowitzke , Polska Cerekiew / Groß Neukirch , Popielów / Poppelau , Prószków / Proskau , Radłów / Radlau , Reńska Wieś / Reinschdorf , Strzeleczki / Klein Strehlitz , Tarnów Opolski / Tarnau , Turawa , Ujazd / Ujest , Walce / Walzen and Zębowice / Zembowitz . With the exception of Kranowitz , which belongs to the Silesian Voivodeship , all municipalities are in the Opole Voivodeship .

Legal basics and everyday life

2002 census

According to the 2002 census, 152,897 residents of Poland stated that they belonged to Germany. Most of them live in the Upper Silesian Voivodeship Opole , where with 106,855 people they make up 10.033% of the population. In the other voivodships, the proportion of the German population is between 0.005% and 0.672%. Furthermore, 204,573 people stated that they speak German in their private life, of which 100,767 are Polish, 91,934 German and 11,872 of other nationalities.

| Voivodeship | population | Of these Germans | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opole | 1,065,043 | 106,855 | 10.033 |

| Silesia | 4,742,874 | 31,882 | 0.672 |

| Warmia-Masuria | 1,428,357 | 4,535 | 0.317 |

| Pomerania | 2,179,900 | 2,319 | 0.106 |

| Lower Silesia | 2,907,212 | 2.158 | 0.074 |

| West Pomerania | 1,698,214 | 1,224 | 0.072 |

| Lebus | 1,008,954 | 651 | 0.064 |

| Kuyavian Pomeranian | 2,069,321 | 717 | 0.034 |

| Greater Poland | 3,351,915 | 1,013 | 0.030 |

| Łódź | 2,612,890 | 325 | 0.012 |

| Mazovia | 5,124,018 | 574 | 0.011 |

| Lesser Poland | 3,232,408 | 261 | 0.008 |

| Podlaskie | 1,208,606 | 85 | 0.007 |

| Subcarpathian | 2,103,837 | 116 | 0.006 |

| Lublin | 2,199,054 | 112 | 0.005 |

| Holy Cross | 1,297,477 | 70 | 0.005 |

| all in all | 38.230.080 | 152.897 | 0.381 |

2011 census

According to initial projections, 45,000 Polish residents gave an exclusively German identity. A German ethnicity alongside another, mostly Polish, indicated 103,000 people. 97.6% of these people are Polish citizens. 58.9% live in rural areas, 41.1% in cities. 96,000 stated that they spoke German at home, of which 33,000 only stated a Polish identity. Almost a fifth of these German speakers are over 65 years old. 58,000 people stated German as their mother tongue, of which around 68.5% only stated a German identity.

The results according to voivodships:

(People who only gave a German nationality and also gave a different ethnicity)

| Voivodeship | population | Of these Germans | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opole | 1,016,212 | 78,595 | 7.73 |

| Silesia | 4,630,366 | 35,187 | 0.76 |

| Warmia-Masuria | 1,452,147 | 4,843 | 0.33 |

| Pomerania | 2,276,174 | 4,830 | 0.21 |

| West Pomerania | 1,722,885 | 3,535 | 0.21 |

| Lebus | 1,022,843 | 1,846 | 0.18 |

| Lower Silesia | 2,915,241 | 5,032 | 0.17 |

| Kuyavian Pomeranian | 2,097,635 | 2,507 | 0.12 |

| Greater Poland | 3,447,441 | 3,421 | 0.10 |

| Łódź | 2,538,677 | 1,489 | 0.06 |

| Mazovia | 5,268,660 | 2,937 | 0.06 |

| Lesser Poland | 3,337,471 | 1,315 | 0.04 |

| Podlaskie | 1,202,365 | 438 | 0.04 |

| Lublin | 2,175,700 | 819 | 0.04 |

| Subcarpathian | 2,127,286 | 590 | 0.03 |

| Holy Cross | 1,280,721 | 430 | 0.03 |

| Poland | 38,511,824 | 147.814 | 0.38 |

Dissemination and analysis

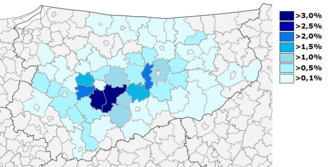

Most Germans live in Upper Silesia and Masuria . Outside of these regions, the proportion of the German minority in the total population does not exceed the 1 percent mark in any municipality. With around 115,000 German residents, Upper Silesia makes up the majority of the 150,000 Germans in Poland.

While in Upper Silesia the proportion of Germans in some municipalities is over a fifth, there are only a few municipalities in Masuria that have more than 1% German residents. The highest proportion there is in a municipality at 7%.

Today Germans live mainly in areas that used to be part of the German Empire : After Upper Silesia and Masuria, these are Pomerania , Lower Silesia and Eastern Brandenburg . Some Germans still live in the former Prussian areas that came to Poland after the First World War , most of them (3421) in the Greater Poland Voivodeship . While there was a strong German minority in these areas until 1945, their current share of the total population is no longer significant.

Political importance

As a political organization of a national minority, the election committee of the German minority is exempt from the 5 percent threshold and has been consistently represented in the Polish parliament since 1991 - most recently with one member.

In the last local elections in 2010, 23 mayors and community leaders were elected from the German list. In addition, the German minority in the districts of Groß Strehlitz, Oppeln and Rosenberg hold the majority of the mandates. In the Sejmik of the Opole Voivodeship, it is the second largest force with 6 seats and has been part of the government since 1998.

Bilingual communities

Are officially bilingual since 2006 municipalities Biala / Zülz , Chrząstowice / Chrząstowice , Cisek / Gmina Cisek , Izbicko / Izbicko , Jemielnica / Himmelwitz , Kolonowskie / Kolonowskie , Lasowice Wielkie / United Lasso joke , Leśnica / Leschnitz , Prószków / Proskau , Radłów / Radlau , Reńska Wieś / Reinschdorf , Strzeleczki / Klein Strehlitz , Ujazd / Ujest and Walce / Walzen , since 2007 Bierawa / Birawa , Tarnów Opolski / Tarnau and Zębowice / Zembowitz , since 2008 Turawa . The municipalities of Murów / Murow , Dobrzeń Wielki / Groß Döbern and Głogówek / Oberglogau have been bilingual since April 22, 2009 and the municipality of Dobrodzień / Guttentag since May 13, 2009 .

Bilingual place-name signs

Bilingual place-name signs may only be set up in the above-mentioned municipalities if the German place names or street names have been officially approved in accordance with the ordinance on bilingual place and location names (Dwujęzyczne nazewnictwo geograficzne) . For this, the municipal council must approve the introduction of the German names and the approval of the voivode and the Polish Ministry of the Interior (MSWiA) must be available. A survey of the community population is only necessary if the proportion of Germans in the population is less than a fifth; however, even municipalities with more than 20% mostly rely on voluntary surveys.

German-language place-name signs had already been allowed since 2005, but it wasn't until 2008 that 250,000 zlotys were planned for the production and installation of signs for the first time .

As a result, the first German-language place-name signs were put up in autumn 2008: On September 4th in Łubowice / Lubowitz , on September 12th the Polish municipality of Radłów / Radlau followed with a ceremonial unveiling and on September 15th the municipality of Cisek / Czissek . In Chrząstowice / Chronstau , signposts with German place names were installed for the first time in addition to place-name signs and, in 2009, bilingual information boards were installed on all public buildings. Finally, Tarnów Opolski / Tarnau was the first municipality to put up signs without asking the population beforehand.

Bilingual place signs are therefore placed in the following municipalities and cities: Radłów / Radlau , Cisek / Gmina Cisek , Leśnica / Leschnitz , Tarnów Opolski / Tarnów , Chrząstowice / Chrząstowice , Izbicko / Izbicko , Dobrodzień / Guttentag , Jemielnica / Himmelwitz , Kolonowskie / Kolonowskie , Krzanowice / Kranowitz , Ujazd / Ujest , Biała / Zülz , Zębowice / Zembowitz , Strzeleczki / Klein Strehlitz , Komprachcice / Comprachtschütz , Dobrzeń Wielki / Groß Döbern , Głogówek / Oberglogau and in Łubowice / Lubowitz , a district of Rudnik .

The bilingual place-name signs are, like the previous ones, green and white. Below the Polish place name is the German name in the same font size.

In the municipality of Cisek / Czissek , separate German-language signs were placed under the place-name signs. Whether this corresponds to the Polish minority law is debatable.

No municipality has yet applied for additional street names in German. Since the political change in 1989, there have been more privately financed bilingual welcome boards.

Bilingual station signs

On October 30, 2012, the first bilingual signs (Polish / German) were put up at train stations in Poland. These signs are located along the Czestochowa - Opole railway in the Chronstau municipality , Opole Voivodeship .

The following train stations are given an additional designation in German:

Controversy

In the eastern German territories that fell to Poland in 1945, the communist leadership tried to erase written evidence of German history by removing inscriptions or monuments. In the Opole region, the German minority tried to limit these actions - in Lasowice Małe (Klein Lassowitz), for example, the local war memorial was buried in front of the Polish authorities. The German war memorials that have been preserved have now become the hallmarks of the Opole region and its German minority. After the fall of the Wall, existing monuments were restored or added memorial stones for the victims of the Second World War.

Depictions of the German military, such as iron crosses , a symbol from the early 19th century, or soldiers' helmets on the monuments are also controversial . Some politicians and the media associated these symbols with National Socialism and called for them to be removed from historical monuments as well. Especially for the monuments erected after 1990 to commemorate the victims of the Second World War, a government commission was convened, which recorded the war memorials in the Opole region and instructed the affected communities to make the following adjustments: In principle, historical monuments should be supplemented by Polish information boards. If the Iron Cross was depicted on new monuments or if the local citizens who fell in World War II were referred to as fallen , this had to be removed. Place names introduced in 1933-45 had to be made illegible on all monuments, even if the place name was official at the time the monument was created. The monuments that were criticized were later re-inspected in order to verify that the changes made were implemented.

Even leading Polish daily newspapers occasionally produce controversial reports on the German minority; alleged scandals are regularly "uncovered", such as an incident in the village of Szczedrzyk / Sczedrzik in the urban and rural community of Ozimek / Malapane , where the plastered lettering of the then introduced place name Hitlersee reappeared after cleaning the memorial for the fallen in 1934 ; the German minority was blamed for this in the media.

Finally, the naming of the bilingual school in Rosenberg / Olesno in honor of the Silesian Nobel Prize winners, proposed by local representatives of the German minority, was given up after public protests. The stumbling block was the Nobel Prize winner Fritz Haber , whose research had also served chemical warfare in the First World War. In the media he was nicknamed "Doctor Death".

Public symbols of bilingualism and the German minority are still controversial in Poland today. The bilingual place-name signs in the municipalities of Radłów / Radlau , Cisek / Czissek and Tarnów Opolski / Tarnau were damaged shortly after they were set up, and there were also other damaged signs. In 2010, three place-name signs were stolen in the community of Guttentag.

Opponents of the minority laws saw their fears confirmed in 2004 that the minority would undermine the state sovereignty of Poland in the Opole region, when the Starost (District Administrator) of Strzelce Opolskie / Groß Strehlitz - himself a member of the minority - the obligatory Polish national coat of arms on his office building with the district coat of arms and replaced a bilingual information sign. In Poland, this approach seemed strange, especially since removing state emblems from official buildings is a criminal offense and the incident led to a heated debate in the Polish parliament. In federal Germany, the use of state emblems is more restricted and uncommon at district or municipality level.

There is also criticism of the association's orientation within the German minority. The criticism of Henryk Kroll's authoritarian leadership style, especially from younger members, resulted in a generation change at the top of the association in April 2008. The new chairman, Norbert Rasch , who was 37 years old at the time, promised the delegates a realignment, less politicization, but more language and culture support in the work of the association.

Criticism from representatives of the German minority

At a meeting with the delegates of the "Advice of Europe's Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities" on 4 December 2008 and criticized the Association of the German social-cultural societies in Poland (VdG) u. a. Too little German lessons in schools, a lack of objectivity in history lessons, difficult access to mass media, unfavorable broadcasting times for minority programs on public television and radio and the lack of minority programs outside the Opole Voivodeship. In addition, the limited use of the German language in authorities and problems with the use of German first and last names were addressed. The inability to use bilingual names outside the municipal level, for example at the level of the districts and voivodeships, was also criticized.

German nationality

By 2005, around 288,000 citizens in Poland, especially in Upper Silesia and Masuria , had received confirmation that they had German citizenship from birth.

The German citizenship at the request of the Federal Office of Administration found.

education

In the border area with Germany, for example in Stettin , and in the main settlement areas of the German minority in the Voivodeships of Opole and Silesia , there are kindergartens with German lessons. But all of these are private initiatives.

In the eastern part of the Opole Voivodeship, where the German minority makes up the majority of the population, the schools offer "native-language German lessons". In practice, this means that students have one hour more German per week than the curriculum for the Polish majority provides. As a rule, it is three instead of two hours of German per week, which the representatives of the minority criticize as completely inadequate. All other subjects, on the other hand, are taught in Polish. The elected representatives of the minority strive for a bilingual high school in all districts in the eastern part of the Opole Voivodeship.

Organizations of the German minority

The German minority in Poland is organized in several associations , clubs and other associations, the largest and most important of which is the Social-Cultural Society of Germans in Opole Silesia, with its headquarters in Opole. Regional companies exist in Allenstein , Breslau , Bromberg , Gdansk , Elbing , Hirschberg in the Giant Mountains , Liegnitz , Lodsch , Oppeln , Posen , Schneidemühl , Stettin , Stolp , Thorn and Waldenburg as well as in the Silesia district ( German Friendship Circle in Silesia District ). The Silesia district is divided into the districts of Beuthen OS , Gleiwitz , Hindenburg OS , Kattowitz , Loslau , Orzesche , Ratibor , Rybnik , Tichau and Teschen . The Social-Cultural Society in Opole has district associations in all districts of the Opole Voivodeship; in total there are eleven district associations.

The umbrella organization for most of the German associations is the Association of German Social-Cultural Societies in Poland (VdG).

Young people organize themselves in the Association of Young People of the German Minority (BJDM) .

Despite strong financial support from Germany (Berlin had made 150 million euros available since 1990), the number of members fell from around 170,000 in 1991 to around 45,000 in 2008.

Another important organization is the German Reconciliation and Future Community based in Katowice , which, according to its own information (2002), has 11,112 contributing members and is not financially supported by the German federal government .

Both organizations differ significantly in goals and principles ; For example, the German Reconciliation and Future Community is also open to non-German members (around 4.2%), while the Social-Cultural Society only accepts members of German origin.

In the regional and central elections in Poland, the German minority is represented by the German Minority Election Committee , which received 32,094 votes (0.2%) in the 2019 parliamentary elections and - since there is no 5% hurdle for the German minority - since then sent a member (currently Ryszard Galla ) to the Polish Parliament (Sejm) .

Institutions

- House of German-Polish Cooperation in Gliwice and Opole

- Foundation Upper Silesian Eichendorff Culture and Meeting Center in Lubowitz

- Chamber of Commerce Silesia

- Silesian Self-Government Association

- German education society

- Silesian Federation of Municipalities and Districts

- Foundation for the Development of Silesia and Promotion of Local Initiatives

Cultural

The annual events of the German minority, the VDG or other institutions include a. the Christmas market in front of the cathedral in Opole and the German Cinema Week in Opole.

For a few years now, the BJDM has been organizing the “Big Sledding” in Opole, where children and young people can skate for free .

Current

In 2015, before the parliamentary elections in Poland, there were isolated attacks on the German minority in Silesia by Polish nationalists. In Krapkowice (German Krappitz ) in the Opole Voivodeship, PiS politicians disrupted an event of the German minority because German songs were sung there, and the politicians demonstrated against the bilingual place-name signs. The German minority association considers this action to be punishable. Every year around 8,000–9,000 people emigrate from Germany to Poland. Poland is number 5 on the list of German emigrants.

Media of the German minority

radio

The first attempt to establish a radio station for the German minority at the end of the 1990s failed because the station was not granted a license. Since 2006 there has been a German-Polish internet radio called Mittendrin . The German minority from the Opole Voivodeship is currently working on a new radio station. The name "Radio HERZ" is planned. For this purpose, a building has already been moved into on the Pascheke in Opole. Those involved wanted to apply for a frequency in 2011 and start in 2012.

Broadcasts:

- Silesia Currently on Radio Opole

- Nasz home on Radio Opole

- Present on Radio Katowice

- The German voice on Radio Vanessa

- Right in the middle of it on Radio Vanessa

- Press review on Radio Plus

- Unique on Radio Plus

- Coffee gossip on Radio Park

- Allensteiner Welle on Radio Olsztyn

- Meeting point Gdańsk on Radio Gdańsk

watch TV

A regular television broadcast of the German minority since 1992 has been the weekly 15-minute magazine Schlesien Journal , which is broadcast on the TVP Opole and TVP Katowice TV channels . Schlesien Journal also had a youth program called Schlesien Journal Jung . The program Schlesien Journal was also broadcast on TVS and could therefore be seen across Europe for several months via the Eutelsat Hotbird 13 ° East satellite. However, this broadcast was discontinued due to a shift to an IP TV broadcast.

newspapers and magazines

The largest newspaper of the German minority is the weekly Schlesische Wochenblatt, renamed Wochenblatt in January 2011 ; the newspapers are published by Pro Futura . The Schlesisches Wochenblatt also published the youth magazine Vitamin de .

See also

- Association of the youth of the German minority

- Forest Germans

- History of the Germans in the Łódź area

- Germans in the Czech Republic

- Poland in Germany

literature

- RM Douglas: Proper transfer. The expulsion of the Germans after the Second World War . Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-40662294-6 .

- Paweł Popieliński: Młodzież mniejszości niemieckiej na Górnym Śląsku po 1989 roku [Youth of the German minority in Upper Silesia after 1989]. Warsaw 2011, ISBN 978-83-60580-62-2 .

- Ingo Eser: People, State, God! The German minority in Poland and their school system 1918–1939. Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-447-06233-6 .

- Manfred Raether: Poland's German Past. Schöneck 2004, ISBN 3-00-012451-9 . Updated new edition as a free e-book (2009).

- Till Scholtz-Knobloch: The German minority in Upper Silesia - self-reflection and the political-social situation with special consideration of the so-called "Opole Silesia (West Upper Silesia)". Görlitz 2002, ISBN 3-935330-02-2 .

- Alastair Rabagliati: A Minority Vote. Participation of the German and Belarussian Minorities within the Polish Political System 1989–1999. Krakow 2001, ISBN 83-88508-18-0 .

- Marek Zybura : Niemcy w Polsce [Germans in Poland]. Breslau 2001, ISBN 83-7023-875-0 .

- Thomas Urban: Germans in Poland - Past and Present of a Minority. Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-45982-X .

- Mathias Kneip: The German language in Upper Silesia. Dortmund 1999, ISBN 3-923293-62-3 .

- Mads Ole Balling: From Reval to Bucharest - Statistical-Biographical Handbook of the Parliamentarians of the German Minorities in East Central and Southeast Europe 1919-1945 . 2nd Edition. tape 1 . Copenhagen 1991, ISBN 87-983829-3-4 , pp. 177 ff .

- Maria Brzezina: Polszczyzna niemców [The Polish language of the Germans]. Warsaw / Krakow 1989, ISBN 83-01-09347-1 .

- Piotr Madajczyk: Poles, the displaced and the Germans who stayed in their home areas since the 1950s. Help - contacts - controversies ( online ).

- Piotr Madajczyk: Niemcy polscy 1944–1989 (Poland-German 1944–1989). Warsaw 2001.

- Adam Dziurok , Piotr Madajczyk, Sebastian Rosenbauer (eds.): The German minority in Poland and the communist authorities 1945–1989 (2 tab.). Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2017, ISBN 978-3-506-78717-0 .

Web links

- Association of German Social-Cultural Societies in Poland (VdG)

- Social-Cultural Society of Germans in Opole Silesia (SKGD)

- German Social-Cultural Society in Breslau (NTKS)

- Association of Youth of the German Minority (BDJM)

- Collection of historical maps on German-Polish history

- Upper Silesian State Museum in Ratingen

- Upper Silesian State Museum in Ratingen: The situation of the German minority in Poland ( Memento from June 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Federal Agency for Civic Education: The Germans in Poland.

- German Embassy Warsaw: German minority.

- German minority , www.polen-diplo.de , website of the Federal Foreign Office.

Footnotes

- ^ A b German representations in Poland: German minority ( memento from January 15, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), publication by the German representation in Poland; accessed on January 14, 2016

- ↑ Tomasz Kamusella : A Language That Forgot Itself. In: Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe . Vol. 13, No 4, 2014, pp. 129-138 ( online ).

- ↑ Niemcy w województwie opolskim w 2010 roku. Pytania i odpowiedzi. Badania socjologiczne członków Towarzystwa Społeczno-Kulturalnego Niemców na Śląsku Opolskim. Projekt zrealizowano na zlecenie Uniwersytetu Osaka w Japonii [Germans in Opole Province in 2010: Questions and Answers: The Sociological Poll Research on the Members of the Social-Cultural Society of Germans in Opole Silesia: The Project Was Carried Out on Behalf of Osaka University, Japan.] Dom Współpracy Polsko-Niemieckiej, Opole / Gliwice 2011.

- ^ Polish Statistics Office: Results of the 2011 census (January 2013). ( Memento from February 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Polish Statistics Office: Results of the 2011 census ( Memento of August 3, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Polish Statistical Office, pp. 270–272 ( Memento from January 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 3.0 MB).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society, 3rd volume 1849-1914. Vol. From the "German double revolution ..." to the beginning of the First World War. ISBN 978-3-406-32263-1 , p. 964.

- ^ Wacław Długoborski : Second World War and Social Change , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen 1981, p. 309.

- ↑ Second World War: What Happened on the Bydgoszcz Blood Sunday , die Welt, April 18, 2012, accessed September 15, 2014.

- ^ "Self-protection" in the Internet portal Deutsche & Polen of Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (rbb) .

- ↑ ikgn.de Article in the Internet portal of the Institute for Culture and History of Germans in Northeast Europe eV (IKGN) at the University of Hamburg.

- ↑ Isabel Heinemann: Race, settlement, German blood. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-89244-623-7 , p. 225 ff.

- ^ Online encyclopedia on the history and culture of German in Eastern Europe - Deutsche Volksliste. Publication by the University of Oldenburg ; accessed on January 17, 2016.

- ^ Helmut Neubach : Review of: Arno Herzig: Geschichte Schlesiens. From the Middle Ages to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2015. ISBN 978-3-406-67665-9 . In: Medical historical messages. Journal for the history of science and specialist prose research. Volume 34, 2015, pp. 300–306, here: p. 304.

- ↑ Printed matter 12/2680 on the small question from the SPD of June 16, 1992 (PDF).

- ^ Location of the monument in Mechnice

- ↑ Manfred Goertemaker: The Potsdam Conference 1945. In: Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens Berlin-Brandenburg (Ed.): Cecilienhof Palace and the Potsdam Conference 1945. Berlin 1995 (Unchanged reprint 2001), ISBN 3-931054-02-0 , p 61.

- ↑ Magdalena Helmich, Jakub Kujawinski, Margret Kutschke, Juliane Tomann: " De-Germanification " and Polonization. The transformation of Wroclaw into a Polish city. Publication on the website of the Chair for Polish and Ukrainian Studies at the European University Viadrina; accessed on January 16, 2016

- ^ Franz-Josef Sehr : Professor from Poland in Beselich annually for decades . In: Yearbook for the Limburg-Weilburg district 2020 . The district committee of the district of Limburg-Weilburg, Limburg-Weilburg 2019, ISBN 3-927006-57-2 , p. 223-228 .

- ^ Theses paper on the development strategy of the German minority (DMI) in Poland ( Memento from December 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) in the Internet portal "House of German-Polish Cooperation" from January 2001.

- ^ Winfried Irgang: History of Silesia. In: Dehio - Handbook of Art Monuments in Poland: Silesia. Berlin 2005.

- ↑ Commentary ( memento of June 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) in Schlesisches Wochenblatt.

- ^ The Germans in Poland - Fate after 1945. Publication Federal Agency for Civic Education; accessed on January 16, 2016

- ↑ The figures from the 2002 census ( Memento from March 26, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Polish Main Statistical Office (GUS). ( Memento of May 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Polish Statistical Office: Results of the 2011 census (PDF; 3.5 MB).

- ^ Article in the Schlesisches Wochenblatt and the Nowa Trybuna Opolska.

- ↑ See Geografia Wyborcza 2010.

- ^ List of the Polish Ministry of the Interior.

- ↑ Approach via place-name signs - New Normality. on the internet portal n-tv .de from September 12, 2008.

- ↑ Lubowice and Lubowitz - With Polish-German town signs history. in the ZDF lunch magazine from September 12, 2008

- ↑ Source: Polish Ministry of the Interior.

- ↑ Chrząstowice, czyli Chronstau. Polsko-niemieckie tablice na dworcach pod Opolem Nowa Trybuna Opolska | NTO, October 30, 2012 (Polish).

- ^ First bilingual signs on train stations Social-Cultural Society of Germans in Opole Silesia | SKGD, October 30, 2012 (Polish).

- ↑ lasowice.eu.

- ↑ Article in the Internet portal NaszeMiasto.pl (Polish).

- ↑ "Wandale zniszczyli tablice dwujęzyczne w Radłowie" - "Vandals destroyed bilingual place-name signs in Radlau" in Nowa Trybuna Opolska.

- ↑ “Zniszczono niemieckie tablice w gminie Cisek” - “German place-name signs in the municipality of Czissek were destroyed” in Nowa Trybuna Opolska.

- ↑ "Bazgrzą sobie po tablicach" - "They smear on the signs" on the website NaszeMiasto.pl (Polish).

- ↑ kradzież dwujęzycznych tablic w Bzinicy Nowej koło Dobrodzienia.

- ↑ Contribution to the Internet portal HOTNEWS.pl (Polish).

- ↑ contribution.

- ↑ Antenne West ( Memento from June 26, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ vdg.pl ( Memento from September 14, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) in the VdG internet portal from December 17, 2008.

- ↑ Commentary ( memento of June 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) in Schlesisches Wochenblatt.

- ↑ http://agmo.de/publikationen/studie .

- ↑ 20 lat TSKN na Śląsku Opolskim. 20 years of the SKGD in Opole Silesia. Gg. Soyial / Cultural Society of Germans in Opole Silesia. Opole 2009, pp. 261-264.

- ↑ Internet portal of the Social-Cultural Society of Germans in Opole Silesia.

- ↑ German-Polish Chronicle, April 2008 ( memento from March 31, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) in German-Polish Calendar from May 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Here is Poland" - Polish politician interrupts German singing duo. Article from October 19, 2015 on focus.de ; accessed on January 15, 2016

- ↑ Emigration to Poland. Article on Woin-auswandern.de ; accessed on January 15, 2016

- ↑ Gazeta.pl: Niemcy chcą swojego radia na Opolszczyźnie. ( Memento from October 22, 2011 in the Internet Archive )