Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff and von Hindenburg (born October 2, 1847 in Posen , † August 2, 1934 at Gut Neudeck , East Prussia ) was a German field marshal and politician. During the First World War , the Supreme Army Command he led exercised dictatorial power from 1916 to 1918. Hindenburg was elected second Reich President of the Weimar Republic in 1925 . In 1932 he was re-elected and remained president until his death. On January 30, 1933, he appointed Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor .

Life

family

On his father's side, Paul von Hindenburg came from an old East Prussian noble family, the von Beneckendorff and von Hindenburg families . He was born in 1847 as the son of the Prussian officer and landowner Hans Robert Ludwig von Beneckendorff and von Hindenburg (1816–1902) and his civil wife Luise Schwickart (1825–1893). His brother Bernhard von Hindenburg , who was eleven years his junior , wrote the Field Marshal's first biography in 1915.

First Paul von Hindenburg was engaged to Irmengard von Rappard (1853–1871) from Sögeln ( Bramsche ), who however died of consumption before the wedding at the age of 17 (until the end of his life he sent a wreath to the grave on every day of his death). On September 24, 1879, Hindenburg and Gertrud von Sperling (1860–1921) married. From this marriage the children Irmengard Pauline Louise Gertrud (1880–1948), Oskar (1883–1960) and Annemarie Barbara Ilse Ursula Margarete Eleonore (1891–1978) emerged. The older daughter married Hans Joachim von Brockhusen (1869–1928) in 1902 , the younger Christian von Pentz (1882–1952) in 1912 and the son in 1921 Margarete von Marenholtz (1897–1988). Hindenburg adopted his nephew Wolf von Beneckendorff (1891–1960), who would later become an actor, after his parents died.

Military career

As the son of a Prussian officer , Hindenburg also embarked on a military career. After attending the community school (elementary school) and the Protestant grammar school in Poznan for two years , he attended the cadet institute in Wahlstatt in Silesia from 1859 to 1863 and the main cadet institute in Berlin from Easter 1863 . In 1865 he was assigned to Queen Elisabeth , the widow of the late Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. , As a personal page. In April 1866 he was accepted as a lieutenant in the 3rd Guards Regiment on foot and took part in the Battle of Königgrätz .

Hindenburg fought in the Franco-German War in 1870/71 . On January 18, 1871, he represented his guards regiment at the imperial proclamation in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles . From 1873 to 1876 he attended the War Academy in Berlin, which he left with the qualification for the general staff . In 1877 he was transferred to the General Staff and promoted to captain the following year . In 1881 he served in the General Staff of the 1st Division in Königsberg and was promoted to major . In March 1888, he was among the officers who on out body Kaiser I. William vigil held.

In 1890 he headed the II. Department in the War Ministry and became a lieutenant colonel the following year . In 1893 he commanded the Oldenburg Infantry Regiment No. 91 and on March 17, 1894 he was promoted to colonel .

On August 15, 1896 he was appointed Chief of the General Staff of the VIII Army Corps in Koblenz and the following year on March 22, 1897 he was appointed major general. On July 9, 1900, he was promoted to lieutenant general and appointed commander of the 28th division in Karlsruhe . On January 27, 1903 he was appointed commanding general of the IV Army Corps in Magdeburg and on June 22, 1905 promoted to general of the infantry . In March 1911 he was adopted into retirement and was awarded the Order of the Black Eagle .

As a pensioner, Hindenburg moved to Hanover for the first time and moved into the Villa Köhler , Am Holzgraben 1, as a tenant in the Oststadt .

Hindenburg's rise during the First World War

On August 22, 1914, Hindenburg became Commander-in-Chief of the 8th Army . The next morning he went to East Prussia , where he four days later at the Battle of Tannenberg for Colonel was promoted. On September 2, 1914, the emperor awarded him the order Pour le Mérite . From September 6 to 14, he took part in the Battle of the Masurian Lakes . He was promoted to Commander-in-Chief East on November 1, 1914, and Field Marshal General on November 27, 1914 . On February 23, 1915, Hindenburg was honored with the oak leaves for the Pour le Mérite for winning the winter battle in Masuria . On August 29, 1916 he was appointed Chief of the General Staff of the Field Army. He was honored with the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross on December 9, 1916 . On March 25, 1918, Hindenburg received the special level for the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross, the so-called Hindenburg Star . On June 25, 1919, he resigned as Chief of the Army General Staff. On July 3, 1919, the mobilization provision was repealed.

At the beginning of the First World War , Hindenburg initially tried in vain for a command. It was only when the situation on the Eastern Front threatened to get out of control that he was appointed Commander in Chief of the 8th Army , with Major General Erich Ludendorff as Chief of Staff. Under his command, the Russian Narew Army, which had invaded East Prussia, was defeated in a battle of encirclement and extermination that lasted from August 26 to 30, 1914. This victory was crucial for Hindenburg in two ways. On the one hand, it was the beginning of the close cooperation with Ludendorff, whose strategic skill the victory was primarily due to - Hindenburg himself hardly made any decisions and repeatedly mentioned that he slept very well during the battle. On the other hand, he established Hindenburg's extraordinary prestige, which was to make him the most powerful man in Germany in the further course of the war. He himself actively worked on this political myth , which should revolve around himself and victory. Immediately after the battle, he got it to be named Tannenberg after the place affected by the fighting on the edge . In the Battle of Tannenberg (Polish: Battle of Grunwald) in 1410, a Polish-Lithuanian army defeated the Teutonic Order , a "notch" that Hindenburg, who was keen on publicity, tried to erase by naming it. The triumphant victory was subsequently attributed to Hindenburg by the public and brought him the appointment of General Field Marshal and the award of the star to the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross. His and Ludendorff's role in the establishment of the military state “Land Ober Ost ” from 1915 onwards was of great importance and aftereffect .

Hindenburg's role in World War I was based primarily on the myth as the “Sieger von Tannenberg”, less on his actual military achievements. In August 1916 he took over the Supreme Army Command with Ludendorff , which quickly gained influence on the politics of the German Empire and practically disempowered Wilhelm II . Hindenburg was (partly) responsible for setting the course in the war, such as the opening of the unrestricted submarine war , the rejection of a mutual agreement and the dictated peace of Brest-Litovsk and Bucharest . The power of Hindenburg and Ludendorff was so great that various contemporaries such as Max Weber , Wilhelm Solf and Friedrich Meinecke spoke of a real " military dictatorship " of the third OHL. This term has been adopted by various historians. Other historians such as Gregor Schöllgen and Hans-Ulrich Wehler , on the other hand, point out that the exercise of power by the OHL cannot be viewed in the strict sense as a military dictatorship, since it has never assumed responsibility for political leadership and has also reached its limits domestically. Wehler emphasizes, however, that "the indirect, nonetheless massive, 'factual exercise of power' of the 3rd OHL clearly came to light". Wolfram Pyta characterizes Hindenburg's rule, as it has been exercised since 1916, as a special form of charismatic rule .

After the military defeat in 1918, Hindenburg advised Wilhelm II to leave the country. By working with the new republican government, he tried to counteract unrest within the army. With the conclusion of the Versailles Treaty in July 1919, President Friedrich Ebert Hindenburg said goodbye at his request. Before the investigative committee of the Weimar National Assembly he spread the stab- in-the-back legend according to which the German army remained "undefeated in the field" and had been "stabbed from behind" by the November revolutionaries by means of an armistice .

1919–1925 retired in Hanover

On June 25, 1919, Hindenburg resigned from his post as Chief of the Army General Staff and left his last place of work in Kolberg . He chose Hanover , which had made him an honorary citizen in August 1915 and gave him a villa in the Zooviertel for lifelong usufruct , as his retirement home. From there he made many journeys through the Reich, especially through East Prussia, where he enjoyed great popularity as the liberator of East Prussia. In 1921 he became chairman of Deutschehilfe and honorary boy of the Corps Montania Freiberg .

After no candidate had achieved an absolute majority in the first ballot for the presidential election on March 29, 1925, the right-wing parties asked the non-party Hindenburg to run. The 77-year-old was hesitant at first, but eventually agreed.

On November 23, 1925, his son Oskar von Hindenburg became first and Wedige von der Schulenburg second military adjutant. In the course of time, his son became the personal assistant of the Reich President and thus effectively the link between the head of state and the Reichswehr Ministry in Bendlerstrasse.

Hindenburg as President of the Reich

In the first ballot of the Reich presidential election, Duisburg's Lord Mayor Karl Jarres , who ran for the right-wing Reich Citizens' Bloc, received a relative majority with 10.8 million votes, but in the second ballot he waived in favor of Paul von Hindenburg. On April 26, 1925 Hindenburg was as a representative of the anti-republican "Reich block", the Wilhelm Marx by Republican "people block" faced, in the second ballot at the age of 77 years as the successor of Friedrich Ebert was elected the President and sworn in on 12 May. To this day, he is the only German head of state who has ever been directly elected by the people.

In England his election was calmly received. The Daily Chronicle wrote that there had been no breach of the peace treaty and that Germany had to be judged by its actions, not its elections. The Times said the voters had chosen the old soldier as the typical and best representative of the nation, and that it would be best for Germany and Europe if the head of the state was a man of honor and energy. People were more critical in France. Le Temps noted that a former army leader had been elected, indicating that Germany did not want to admit its defeat in the war.

Research is divided in the verdict on Hindenburg's administration up to the beginning of the global economic crisis . Hagen Schulze, for example, emphasizes Hindenburg's loyalty to the Weimar Constitution , which as a monarchist he was distant from, but which he upheld until 1930 "like the Prussian field service regulations ". Hindenburg felt that he was strictly bound by his oath of office and therefore never used her emergency article 48 until 1930 . Schulze's Berlin colleague Henning Köhler confirms that Hindenburg complied with the constitution until 1930, but draws attention to the fact that the power-conscious president thwarted attempts to limit his official powers by means of an executive law under Article 48. He also had a significant influence on the composition of the cabinets and "clearly preferred conservative politicians".

Beginning of the presidential cabinets

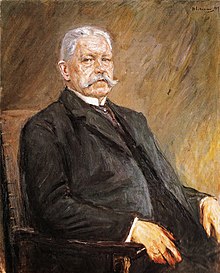

In the anti-Semitic camp , Hindenburg received criticism in 1927 for having himself painted by “the Jew Liebermann” for a state portrait. After he had signed the Young Plan in 1930 , which the right-wing parties presented as an obligation to enslave the people for decades , his former political friends increasingly moved away from him. Hindenburg decided to replace the currently ruling grand coalition under Chancellor Hermann Müller (SPD) with an anti-Marxist and anti-parliamentary government. The opportunity arose after the grand coalition broke up over the question of the rate of contributions to unemployment insurance. On March 29, 1930, he appointed Heinrich Brüning (center) as Chancellor of a minority cabinet without consulting parliament. This began the era of the presidential cabinet , in which the respective chancellor should mainly depend on the confidence of the president. The planned elimination of parliament, however, did not entirely succeed, since the Reichstag could repeal the emergency ordinances issued by the government under Article 48 of the Reich constitution at any time. When he did that in June 1930, Hindenburg disbanded him without further ado - a decision with serious consequences, because this Reichstag was the last in which the democratic parties had a majority. Since the beginning of the global economic crisis had radicalized large parts of the electorate, the proportion of votes of the two extreme parties, the KPD and above all the NSDAP, increased . Thus the political emergency, which according to the meaning of the constitution should actually be remedied by the application of Articles 48 and 25, was only brought about by Hindenburg's policy.

In order to prevent further dissolution of parliament, the SPD decided to tolerate the Brüning government in future, that is, to vote against further motions by the extremist parties to repeal the emergency ordinances. The second part of Hindenburg's plan had thus failed: the government remained dependent on parliament and the social democrats hated by Hindenburg.

In the 1932 presidential election , Hindenburg was confirmed in office for a further seven years. This is thanks to the fact that all democratic parties, including the Social Democrats and the Center , backed the staunch monarchists in order to prevent Hitler from being president. During the election campaign in the Reichstag, the NSDAP MP Joseph Goebbels declared that Hindenburg "according to his name, his past and his achievements [belongs] to us and not to those who are ready to vote for him today."

The Eastern Aid Scandal

Hindenburg was to get the old Gut Neudeck family estate as a gift from a group of friends around Elard von Oldenburg-Januschau for his 80th birthday in 1927 , after the Hindenburg family could no longer hold it for financial reasons. However, the funds collected were far from being sufficient and were increased through collections in associations, but above all through donations from business, so that the amount of 1 million Reichsmarks was finally reached. In order to save inheritance taxes, it was immediately transferred to his son Oskar . This behavior, legal in principle, but disreputable for a man in his position, damaged his reputation. There were also allegations of corruption against Hindenburg in connection with the "East Prussia Act" passed two years later, which economically favored the group of donors and other Junkers . These events and the subsequent arguments and investigations went down in history as the Osthilf scandal . Historians suggest that these entanglements may have influenced Hindenburg's decision in favor of Hitler.

From Papen to Schleicher

After the election, Hindenburg came under the influence of the camarilla , a circle of friends and companions of the political right , even more than before . This included, among others, Oskar, the "son of the Reich President not provided for in the constitution" (a much-quoted quip by Kurt Tucholsky ), his neighbor on Neudeck Elard von Oldenburg-Januschau as well as Lieutenant General Kurt von Schleicher and finally Franz von Papen . This persuaded Hindenburg to dismiss Brüning and instead appoint von Papen as Reich Chancellor, who should rule more to the right . (Hindenburg's biographers, especially Wolfram Pyta and his former biographer Dorpalen, emphasize that Hindenburg made these decisions on his own responsibility. Both biographies and memoirs of those involved - e.g. State Secretary Meißner - relativize the influence of the advisors and emphasize Hindenburg's personal responsibility in these decisions ). When this did not lead to success, the district briefly considered a coup d'état to establish an authoritarian regime, but Schleicher refused to make the Reichswehr available for it.

Ultimately, the Reich President was only faced with the alternative: Either he would reinstate a presidential government without the support of the people, which could possibly lead to a civil war, which the Reichswehr - as corresponding simulation games commissioned by Reichswehr Minister Schleicher showed in his ministry in early December 1932 - could not win, or he formed a majority government in the Reichstag or a government that was formally a minority government, but would have a reasonable prospect of gaining a majority in the Reichstag. Since the elections in July and November 1932, this was no longer possible without the participation of the National Socialists. On November 6, a “German Committee” spoke out in favor of the Papen government, for the DNVP and against the NSDAP under the heading “With Hindenburg for people and empire!”. A total of 339 people signed this appeal, including several dozen large industrialists such as Ernst von Borsig , the chairman of the mining association Ernst Brandi , Fritz Springorum and Albert Vögler . On November 19, 1932, Hindenburg received opposing submissions from twenty industrialists, medium-sized entrepreneurs, bankers and agrarians with the request to appoint Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor . However, on December 2, 1932, Hindenburg appointed Kurt von Schleicher as Reich Chancellor. He was still trying to move parts of the NSDAP around Gregor Strasser away from Hitler into a cross front , but this failed. When Schleicher then proposed for his part to dissolve the Reichstag and not to have a new one elected until further notice in violation of the Reich constitution, Hindenburg withdrew his support.

Appointment of Hitler and political end

Despite his initial personal aversion to Hitler, whom he disparagingly called the “ Bohemian private ”, Hindenburg came more and more into his sphere of influence. On January 30, 1933, Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor (so-called seizure of power ). Apart from Hitler, there were only two National Socialists in the new Hitler cabinet: Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick and Hermann Göring, who were ministers without a portfolio . On February 1, 1933, he dissolved the Reichstag. The ordinance to dissolve the Reichstag is signed by Hindenburg, Hitler and Frick. In the course of February a whole series of measures such as the “ Ordinance of the Reich President for the Protection of the German People ” and (immediately after the Reichstag fire of February 27, 1933) the “ Ordinance of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State ” were enacted the fundamental rights have been suspended until further notice (in fact until the end of the Second World War ). As a result, there were mass arrests of supporters of the KPD and the SPD.

On March 21, 1933, the so-called Potsdam Day , the newly elected Reichstag was opened in the Potsdam Garrison Church , the burial place of Frederick the Great . The state act was by no means prepared by Joseph Goebbels, as is often assumed, but was in charge of the Reich Ministry of the Interior with the participation of a number of other actors, not least Hindenburg and Hitler himself. By the place and date of the celebration, the numerous guests of honor from the old Reichswehr as well Hitler's bow to the aged Reich President established a symbolic continuity between the imperial era and the Third Reich , and Hindenburg's high reputation for the new regime was instrumentalized and captured. At the end of his speech, Hitler skillfully praised Hindenburg's life and achievements. Hindenburg reacted to tears when he paid homage to Hitler and the leaders of the Reich who were present. The "final breakthrough in the personal relationship between Hitler and Hindenburg" had been achieved.

The Enabling Act passed by the Reichstag on March 23, 1933 by a two-thirds majority repealed the Reichstag's sole legislative power as laid down in the Weimar Constitution . Now the government was able to enact laws itself and was no longer dependent on the right of the Reich President to issue an emergency ordinance, although the right to issue an emergency ordinance remained unaffected at the request of the bourgeois parties, above all the Center, as a condition for their approval of the Enabling Act.

In 1933, Hindenburg received endowments totaling one million Reichsmarks from the Reich government and the Prussian government .

At the beginning of March 1934, Papen approached Hindenburg, asking him to write a political will in order to avoid a "chaotic situation" in the event of the incapacity to govern. Hindenburg was supposed to recommend the introduction of a monarchy to the German people. At that time Papen believed that Hitler was not averse to the monarchical form of government, and considered himself a suitable Reich President. He drafted a draft based on Hindenburg's report in Out of My Life . At the end of April 1934, Hindenburg informed the Vice Chancellor that he did not want to make an official recommendation on the form of government. Instead, he would personally recommend the monarchy to Hitler in a letter. At the beginning of May 1934, Hindenburg had his second adjutant Wedige von der Schulenburg create a fair copy based on Papen's draft, which also contained the last chapter from Hindenburg's memoir and his personal letter to Hitler. The documents were deposited in Hindenburg's study. Previously, on April 4, 1933, Hindenburg had urged Hitler in a letter to include a combatant clause in the law for the restoration of the civil service .

He himself left for East Prussia in June and was no longer present in Berlin. At the end of June 1934, after much preparation by Hitler and his allies, the murder actions took place as part of the alleged " Röhm Putsch ". Alleged opponents of Hitler inside and outside the SA were killed on the grounds that they wanted to take part in an attempted coup led by the SA leader Ernst Röhm. Whether the aged Hindenburg, together with Reichswehr Minister von Blomberg, encouraged Hitler to take action by verbal requests on the occasion of his visit on June 21, is disputed among historians. Wilhelm von Ketteler , an employee of the Vice Chancellery and himself endangered as a potential victim of the persecution, drove himself to East Prussia during the house arrest of his superior Franz von Papen and indirectly persuaded the Reich President to order the end of the shootings, which Hitler followed.

In July 1934, Hindenburg's health deteriorated further. Until then, he had performed his official duties as President of the Reich. Even in the final phase of his bladder ailment, “Hindenburg remained in full possession of his intellectual powers. Only twenty hours before his death did he lose his consciousness, but recognized Hitler when he visited the dying man again on the afternoon of August 1st. "

Death and burial

On the morning of August 2, 1934 at 9 a.m., Hindenburg died at Gut Neudeck. He was supposed to be buried there, but Hitler organized a burial in the monument to the battle of Tannenberg .

On August 1, the day before Hindenburg's death, the Hitler cabinet passed a law on the merging of the offices of Reich Chancellor and Reich President in the person of Hitler. This law came into force with the death of Hindenburg. Oskar von Hindenburg withheld the documents of his father's political will for a week. Papen received it on August 9th, and handed it over to Hitler on August 14th. Hitler had already been informed of the content in advance by Papen. Hitler withheld the letter addressed to him personally and presumably had it destroyed later. The other documents were published on August 15 as "Hindenburg's political testament". From the circumstances of the publication it can be concluded that Hitler, Papen and Oskar von Hindenburg had agreed not to publish the will until shortly before the referendum on the head of state of the German Reich on August 19, 1934, so that Hitler could benefit from it, although Hindenburg had not named him as his successor. The day before the election, Oskar von Hindenburg gave a radio speech in which he claimed that his father saw Hitler as "his immediate successor as head of the German Reich". In the referendum, almost ninety percent of the voters approved the law on the head of state of the German Reich .

When the Red Army approached in January 1945, the Wehrmacht brought Hindenburg's and his wife's coffin from the Tannenberg memorial to the light cruiser Emden , to be transported from Königsberg to Pillau and from there on the Pretoria passenger ship to Stettin . Then together with the coffins of the Prussian kings Friedrich II and Friedrich Wilhelm I , the flags and standards of the German army from 1914–1918, the files of the Foreign Office, pictures from Prussian state museums , the library of Sanssouci and the Prussian crown jewels in At the end of April 1945, she tracked down the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Section of the US Army in a salt mine used as an ammunition store in Bernterode, Thuringia, and had them transported to the American occupation zone in Marburg before the change of occupation to the Red Army . There Hindenburg and his wife found their final resting place in the north tower chapel of the Elisabethkirche .

Honors and their withdrawal

Honorary citizenships

Hindenburg already became an honorary citizen of several cities and municipalities during the First World War . The number grew in particular from 1933 until his death in 1934 to a total of 3824 honorary citizenships. Since the 1970s, there have been citizens' discussions on remembrance culture and historical-political initiatives to revoke Hindenburg's honorary citizenship in many cities and municipalities.

Since the end of the Nazi regime, numerous municipalities such as Dortmund, Cologne, Karlsruhe, Leipzig, Munich, Münster, Stuttgart and Konstanz have deleted the honorary citizenship, which no longer existed after death, as a Nazi burden. In other places there were corresponding initiatives that did not succeed. In January 2020, Berlin removed Hindenburg from the list of honorary citizens.

see also: Paul von Hindenburg as an honorary citizen

Honorary doctorates

Hindenburg was an honorary doctor of all four faculties of the University of Königsberg , the law and political sciences of the University of Breslau , the law and philosophy faculty of the University of Bonn and the law faculty of the University of Graz . At the same time, Hindenburg was Dr.-Ing. E. h. of all technical universities of the Weimar Republic and the Free City of Danzig as well as Dr. med. vet. hc from the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover . He was also an honorary citizen of the Universities of Göttingen , Königsberg, Cologne and Jena as well as the Technical University of Stuttgart and the Forestry University of Eberswalde .

medal

Hindenburg was awarded the following medals (selection):

- Black Eagle Order

- Grand Cross of the Iron Cross with the Golden Star

- Pour le Mérite with oak leaves

- Grand Cross of the Austrian Military Maria Theresa Order

- Order of Saint Tamara

He was honorary commander of the Order of St. John and dean of the Brandenburg cathedral monastery.

Name sponsorships, discussion and withdrawal

Numerous streets, squares, bridges and public facilities such as schools or barracks were named after him, as was the Hindenburgdamm in Sylt, which he inaugurated in 1927 . The town of Zabrze in Upper Silesia was renamed Hindenburg on February 21, 1915 in recognition of its services . In 1933, Ramsau near Berchtesgaden renamed the oversized linden tree, previously known as the "Large Linden tree", into " Hindenburglinde ". In 1948, the French military government ordered the Hindenburg sculpture to be covered up in the Hindenburg Memorial Church in Stetten . In 1980 this was exposed again.

Ships and airships were also named after Paul von Hindenburg. During the First World War, a Derfflinger-class battle cruiser , the SMS Hindenburg , bore his name. The Kriegsmarine allegedly planned to give one of the planned battleships of the H-class the name Hindenburg . The airship Hindenburg , with which German passenger airship travel reached its peak and ended in 1937, when the Hindenburg burned in the Lakehurst disaster, became better known .

Several decades after the end of the Nazi regime, public places named after Hindenburg were renamed in numerous municipalities because of its Nazi burden. In April 2009 the Hindenburg-Gymnasium Trier changed its name to Humboldt-Gymnasium . The Anton-Leo-Schule in Bad Säckingen was the last school named after Hindenburg, it was renamed in 2013. This had previously failed despite several initiatives.

In March 2012, the City Council of Münster decided to rename Hindenburgplatz to Schlossplatz. Corresponding initiatives had repeatedly failed in the post-war decades, most recently in 1998. A referendum against the council decision was ultimately unsuccessful; in a referendum in September 2012, almost 60 percent of Münster's voters refused to rename the square again in its old name Hindenburgplatz.

In Ludwigsburg , the city administration's submission to rename Hindenburgstrasse failed on July 30, 2015 due to the rejection of the CDU parliamentary group, the Free Voters parliamentary group and the Republican City Council . In addition, a city council of the FDP rejected the proposal.

In 2014, the city of Hanover appointed an advisory board made up of experts to check whether people who gave their names to streets “had active participation in the Nazi regime or serious personal actions against humanity”. He suggested the renaming of the street named after Hindenburg. According to the presentation of this advisory board, Hindenburg "paved Hitler's way to power and supported all of Hitler's political measures". This could not be put into perspective by the fact that Hindenburg was "no longer in control of his decisions", because the theses in this regard have been refuted.

See also: Hindenburgallee , list of Hindenburgstraßen , Hindenburgplatz , Hindenburgbrücke , Hindenburgschule , Hindenburg barracks , Hindenburgufer , Hindenburgschleuse , Hindenburgpark

Postage stamps

The postage stamp years from 1928 to 1936 of the Deutsche Reichspost contained two postage stamp series with the portrait of Hindenburg. After his death, the serial stamps were overprinted with a black border from the beginning of September 1934 .

Fonts

- Out of my life. Hirzel, Leipzig 1920 ( digitized in the Internet Archive ).

- Letters, speeches, reports. Edited and introduced by Fritz Endres. Langewiesche-Brandt, Ebenhausen 1934.

-

Forewords wrote Hindenburg to:

- Heinrich Beenken (ed.): What we have lost. Torn away but never forgotten German land. Zillessen, Berlin 1920.

- Gerhard Schultze-Pfaelzer: From Spa to Weimar. The story of the German era. Grethlein & Co, Zurich 1929.

See also

literature

- Andreas Dorpalen: Hindenburg in the history of the Weimar Republic. Leber, Frankfurt am Main 1966.

- Walther Hubatsch : Hindenburg and the state. From the papers of the Field Marshal General and President of the Reich from 1878 to 1934. Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen 1966.

- John Wheeler-Bennett: The Wooden Titan. Paul von Hindenburg. Wunderlich, Tübingen 1969.

- Werner Conze : Hindenburg, Paul von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , pp. 178-182 ( digitized version ).

- Werner Maser : Hindenburg. A political biography. Moewig, Rastatt 1989, ISBN 3-8118-1118-5 .

- Walter Rauscher: Hindenburg. Field Marshal and President. Ueberreuter, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-8000-3657-6 .

- Harald Zaun : Paul von Hindenburg and German Foreign Policy 1925–1934. Böhlau (also dissertation, Cologne 1998) Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-412-11198-8 .

- Jesko von Hoegen: The hero of Tannenberg. Genesis and function of the Hindenburg myth (1914–1934.) Böhlau, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-17006-6 .

- Wolfram Pyta : Hindenburg. Rule between Hohenzollern and Hitler. Siedler, Munich, 2007, ISBN 978-3-88680-865-6 .

- Anna von der Goltz: Hindenburg. Power, Myth, and the Rise of the Nazis. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2009, ISBN 978-0-19-957032-4 (Oxford Historical Monographs).

Movies

- Ostpreussen und seine Hindenburg , D 1916, directed by Gustav Trautschold , Richard Schott

- The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin , USA 1918, directed by Rupert Julian , with Jay Smith as Paul von Hindenburg.

- Yankee Doodle in Berlin , USA 1919, directed by F. Richard Jones, with Bert Roach as Paul von Hindenburg.

- Tannenberg , D 1932, directed by Heinz Paul , with Klaus Koerner as Hindenburg.

- Stresemann , FRG 1956, directed by Alfred Braun , with Arthur Malkowsky as Hindenburg.

- The song of the sailors , GDR 1958, director: Kurt Maetzig , with Eduard von Winterstein as Hindenburg.

- Hindenburg . D 2013, documentary film, 90 min, written and directed by Christoph Weinert.

Web links

- Literature by and about Paul von Hindenburg in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Paul von Hindenburg in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Paul von Hindenburg in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Paul von Hindenburg. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Hindenburg in the Prussian Chronicle ( Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg )

- Filming of Hindenburg with Ludendorff while studying maps during the First World War

- Rally of the Reich Government to the German people! (August 2, 1934)

- Songs about Hindenburg

- Historical footage of Hindenburg on the European Film Gateway

- Sound recording by Paul von Hindenburg in the online archive of the Austrian Media Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Detlef HO Kopmann: Wedekindstrasse - From the villa district to the thoroughfare . In: Eckhard von Knorre, Achim Sohns, Uwe Brennenstuhl (eds.): Oststadt Journal , February 2007 edition, hannover-oststadt.de ( Memento from September 1, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (District Information System Hannover-Oststadt), accessed on February 25, 2013.

- ^ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century. Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Leipzig 2002, pp. 90 ff.

- ^ Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius : Land of War in the East. Conquest, colonization and military rule in the First World War. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-930908-81-6 , p. 33 ff.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 . CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 112 f.

- ↑ see for example Walter Görlitz : The German General Staff . Verlag der Frankfurter Hefte, Frankfurt am Main 1950, p. 255; Hajo Holborn : German history in modern times, Vol. III: The age of imperialism . Oldenbourg, Munich 1971, p. 258; Hans-Ulrich Wehler: The German Empire 1871-1918 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1973. p. 213; Martin Kitchen, The silent dictatorship. The politics of the German high command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff 1916-1918 . Taylor & Francis, London 1976 Hagen Schulze : Weimar. Germany 1917–1933 . Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1994, p. 146; Hans Mommsen , Rise and Fall of the Republic of Weimar 1918–1933 , paperback edition, Ullstein, Berlin 1998, p. 14.

- ↑ Gregor Schöllgen: The Age of Imperialism . Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, p. 159.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 . CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Wolfram Pyta: Hindenburg. Rule between Hohenzollern and Hitler. Siedler, Berlin 2007, pp. 285–293.

- ^ Enno Meyer: Twelve events in German history between the Harz Mountains and the North Sea. 1900 to 1931 . Lower Saxony State Center for Political Education, Hanover 1979, p. 88; Wolfram Pyta: Hindenburg . Siedler, Munich 2007, p. 441.

- ^ Eugene Davidson: The Making of Adolf Hitler. The Birth and Rise of Nazism . Univ. of Missouri Press, Columbia MO 1997, pp. 219 f.

- ^ Hagen Schulze: Weimar. Germany 1917–1933 (= The Germans and their Nation. Volume 4.) Siedler, Berlin 1994, p. 298.

- ^ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century. Hohenheim / Stuttgart / Leipzig 2002, p. 109.

- ^ Information ( memento of August 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) from the House of the Wannsee Conference on the portrait

- ^ Speech of February 25, 1932 in the German Reichstag

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär , Winfried Vogel : Serving and earning. Hitler's gifts to his elites. Frankfurt 1999, ISBN 3-10-086002-0 .

- ^ Henry A. Turner, The Big Entrepreneurs and the Rise of Hitler , Siedler Verlag Berlin 1985, p. 357.

- ↑ "The Reich President was never a puppet" , interview of January 9, 2008 by Sven Felix Kellerhoff with Wolfram Pyta on Welt Online

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: Chronicle of an event that was regarded as unsuccessful at the time. Seventy years ago, the new German government under Hitler made its political peace with President Hindenburg on the “Day of Potsdam” . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . March 15, 2003, p. 41 .

- ↑ Christoph Raichle: Hitler as a symbol politician . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2013, p. 83-86 .

- ^ Pyta: Hindenburg . 2007, p. 824 ff .

- ↑ Horst Mühleisen: Hindenburg's testament from May 11, 1934 . In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 44 (1996), 3, pp. 355–371, cited above. P. 358 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Ralf Oberndörfer : "... are to be retired." On the persecution of Jewish judges and public prosecutors in Saxony during National Socialism. . Documentation by the Saxon Ministry of Justice , Dresden 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Daniel Koerfer: Vice Chancellery group against Hitler. In: FAZ , April 10, 2017, accessed on April 14, 2017.

- ^ Wolfram Pyta: Hindenburg. Rule between Hohenzollern and Hitler. P. 855.

-

↑ Law on the Head of State of the German Reich , August 1, 1934:

Ҥ 1. The office of Reich President is combined with that of Reich Chancellor. As a result, the previous powers of the Reich President are transferred to the Fuehrer and Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler. He appoints his deputy.

§ 2. This law comes into force with effect from the time of the death of the Reich President von Hindenburg. ”( PDF ). - ↑ Horst Mühleisen: Hindenburg's testament from May 11, 1934 . In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 44 (1996), 3, pp. 355–371, cited above. P. 371. ( PDF ).

- ^ Werner Maser : Hindenburg. A political biography. 2nd Edition. Moewig, Rastatt 1990, p. 376.

- ↑ karlsruhe.de: Honorary Citizens of the City of Karlsruhe (1900 - 1964)

- ↑ https://www.konstanz.de/141717.html

- ^ Honorary citizenship of Hindenburg. Munster said no. Bonner Rundschau, September 17, 2012.

- ↑ Hindenburg no longer an honorary citizen of Berlin after 87 years

- ↑ The old Hindenburg School is now called the Anton Leo School. Badische Zeitung , September 6, 2013.

- ↑ The Hindenburg School wants to realign itself. Badische Zeitung, November 23, 2010.

- ^ Hindenburg School: Renewed demand for a new name. Südkurier , April 19, 2010.

- ^ Referendum in Münster. Spiegel Online , September 16, 2012.

- ^ [1] Stuttgarter Zeitung

- ↑ These ten streets are to be renamed. In: Online edition of Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung , October 2, 2015, accessed on October 3, 2015.

- ↑ Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung of October 2, 2015, p. 18.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kruse: Review in H-Soz-u-Kult , March 16, 2010.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hindenburg, Paul von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Beneckendorff and von Hindenburg, Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German Field Marshal General and politician, President of Germany during the Weimar Republic |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 2, 1847 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Poses |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 2, 1934 |

| Place of death | New deck |