New York Public Library Main Branch: Difference between revisions

→History: add picture: architectural rendering of front facade |

URL |

||

| (587 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Library in Manhattan, New York}} |

|||

{{Infobox_nrhp | name =New York Public Library |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

| nrhp_type = nhl |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=February 2023}} |

|||

| image = New York Public Library 030616.jpg |

|||

{{Use American English|date=July 2022}} |

|||

| caption = Often simply called the "New York Public Library", the official name of the main branch is the "Humanities and Social Sciences Library" |

|||

{{Infobox library |

|||

| location= [[New York, NY]] |

|||

| name = Stephen A. Schwarzman Building |

|||

| lat_degrees = 40 | lat_minutes = 45 | lat_seconds = 11.93 | lat_direction = N |

|||

| native_name = Main Branch |

|||

| long_degrees = 73 | long_minutes = 58 | long_seconds = 56.34 | long_direction = W |

|||

| native_name_lang = en |

|||

| area = |

|||

| image = New York Public Library - Main Branch (51396225599).jpg |

|||

| built =[[1897]]–[[1911]] |

|||

| image_size = |

|||

| architect= [[Carrère and Hastings]] |

|||

| caption = The main entrance on [[Fifth Avenue]] |

|||

| architecture= Beaux Arts |

|||

| country = United States |

|||

| designated= [[December 21]], [[1965]]<ref name="nhlsum">{{cite web|url=http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=393&ResourceType=Building |

|||

| type = [[Research library]] |

|||

|title=New York Public Library|date=2007-09-16|work=National Historic Landmark summary listing|publisher=National Park Service}}</ref> |

|||

| scope = |

|||

| added = [[October 15]], [[1966]]<ref name="nris">{{cite web|url=http://www.nr.nps.gov/|title=National Register Information System|date=2007-01-23|work=National Register of Historic Places|publisher=National Park Service}}</ref> |

|||

| established = {{Start date|1911|05|23}} (opened to public) |

|||

| governing_body = Local |

|||

| architect = [[Carrère and Hastings]] |

|||

| refnum=66000546 |

|||

| location = 476 [[Fifth Avenue]], [[Manhattan]], New York 10018 |

|||

| service_area = |

|||

| mapframe = no |

|||

| branch_of = [[New York Public Library]] |

|||

| items_collected = Approximately 2.5 million ({{as of|2015|alt=2015}}){{efn|name=items-collected}} |

|||

| website = {{URL|https://www.nypl.org/locations/schwarzman|nypl.org/schwarzman}} |

|||

| module = {{Infobox historic site |

|||

| image_map = {{Maplink|frame=yes|plain=yes|frame-align=center|frame-width=260|frame-height=180|zoom=10|type=point|title=Main Branch, New York Public Library}} |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|40|45|11|N|73|58|55|W|type:landmark_region:US-NY|display=inline,title}} |

|||

|embed=yes |

|||

| built = 1897–1911 |

|||

| architecture = [[Beaux-Arts architecture|Beaux-Arts]] |

|||

| designation1 = NHL |

|||

| designation1_date = December 21, 1965<ref name="nhlsum">{{cite web |url=http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=393&ResourceType=Building |title=New York Public Library |date=September 16, 2007 |work=National Historic Landmark summary listing |publisher=National Park Service |url-status = dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071205070817/http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=393&ResourceType=Building |archive-date=December 5, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

| designation1_number = 66000546 |

|||

| designation2 = NRHP |

|||

| designation2_date = October 15, 1966<ref name="nris">{{NRISref|2007a|dateform=mdy}}</ref> |

|||

| designation2_number = 66000546 |

|||

| designation3 = NYSRHP |

|||

| designation3_date = June 23, 1980<ref name="Cultural Resource Information System">{{cite web | title=Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS) | publisher=[[New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation]] | date=November 7, 2014 | url=https://cris.parks.ny.gov/ | access-date=July 20, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

| designation3_number = 06101.000079 |

|||

| designation4 = NYCL |

|||

| designation4_date = January 11, 1967 |

|||

| designation4_number = 0246 |

|||

| designation4_free1name = Designated entity |

|||

| designation4_free1value = Facade<ref>{{harvnb|ps=.|Landmarks Preservation Commission|1967}}</ref> |

|||

| designation5 = NYCL |

|||

| designation5_date = November 12, 1974 |

|||

| designation5_number = 0880 |

|||

| designation5_free1name = Designated entity |

|||

| designation5_free1value = Interior: Astor Hall, Stairs, and McGraw Rotunda<ref>{{harvnb|ps=.|Landmarks Preservation Commission|1974}}</ref> |

|||

| designation6 = NYCL |

|||

| designation6_date = August 8, 2017 |

|||

| designation6_number = 2592 |

|||

| designation6_free1name = Designated entity |

|||

| designation6_free1value = Interior: Rose Main Reading Room and Public Catalog Room<ref>{{harvnb|ps=.|Postal|2017}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Stephen A. Schwarzman Building''' (commonly known as the '''Main Branch''', the '''42nd Street Library''', or just the '''New York Public Library'''{{Efn|As the flagship building of the New York Public Library system, the Main Branch is often referred to as just the '''New York Public Library'''. The branch was originally called the '''Central Building'''<ref>{{cite book |title=Handbook of the New York Public Library |publisher=New York Public Library |page=[https://archive.org/details/handbooknewyork01librgoog/page/n7 7] |date=1921 |url=https://archive.org/details/handbooknewyork01librgoog |quote=The Central Building of The New York Public Library |access-date=January 10, 2016}}</ref> and was later known as the '''Humanities and Social Science Center'''.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1976/12/15/archives/library-will-get-3-million-grant-from-us-fund.html |title=Library Will Get $3 Million Grant From U.S. Fund |last=Cummings |first=Judith |date=December 15, 1976 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref>}}) is the flagship building in the [[New York Public Library]] system in the [[Midtown Manhattan|Midtown]] neighborhood of [[Manhattan]] in [[New York City]]. The branch, one of four [[Research library|research libraries]] in the library system, contains nine separate divisions. The structure contains four stories open to the public. The main entrance steps are at [[Fifth Avenue]] at its intersection with East 41st Street. {{As of|2015}}, the branch contains an estimated 2.5 million volumes in its [[Library stacks|stacks]].{{efn|The number of items varies widely between 1.8 and 4 million, and a figure of 3.5 million is often cited. However, in 2015, the New York Public Library said that the Main Branch's collection numbered 2.5 million.<ref name="NYTimes-SlipperyNumber-2015">{{cite web |title=A Slippery Number: How Many Books Can Fit in the New York Public Library? |website=The New York Times |date=November 28, 2015 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/28/arts/design/a-slippery-number-how-many-books-can-fit-in-the-new-york-public-library.html |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref>|name=items-collected}} The building was declared a [[National Historic Landmark]], a [[National Register of Historic Places]] site, and a [[New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission|New York City designated landmark]] in the 1960s. |

|||

The '''Humanities and Social Science Library''' of [[New York Public Library]], more widely known as the library system's '''"Main Branch"''' is the flagship building in the system and a prominent historic landmark in Midtown [[Manhattan]]. The branch, opened in [[1911]], is one of four research libraries in the library system. |

|||

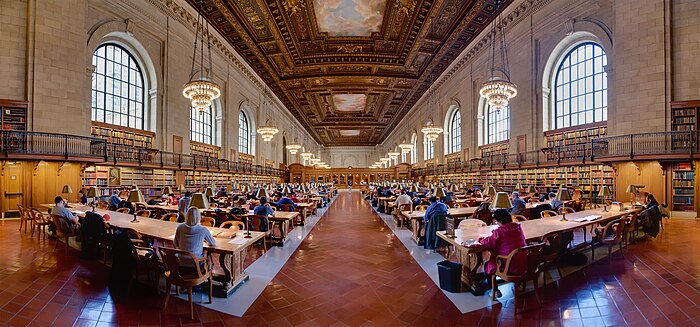

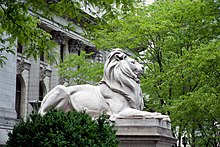

The Main Branch was built after the New York Public Library was formed as a combination of two libraries in the late 1890s. The site, along Fifth Avenue between 40th and [[42nd Street (Manhattan)|42nd Streets]], is located directly east of [[Bryant Park]], on the site of the [[Croton Distributing Reservoir|Croton Reservoir]]. The architectural firm [[Carrère and Hastings]] constructed the structure in the [[Beaux-Arts architecture|Beaux-Arts]] style, and the structure opened on May 23, 1911. The marble facade of the building contains ornate detailing, and the Fifth Avenue entrance is flanked by a pair of stone lions that serve as the library's icon. The interior of the building contains the Main Reading Room, a space measuring {{convert|78|by|297|ft|m}} with a {{convert|52|ft|m|adj=mid|-high}} ceiling; a Public Catalog Room; and various reading rooms, offices, and art exhibitions. |

|||

The famous main reading room of the library (Room 315) is a majestic 78 feet (23.8 m) wide by 297 feet (90.5 m) long, with 52 feet (15.8 m) high ceilings. The room is lined with thousands of reference books on open shelves along the floor level and along the balcony, lit by massive windows and grand chandeliers, and furnished with sturdy wood tables, comfortable chairs, and brass lamps. It is also equipped with computers providing access to library collections and the Internet as well as docking facilities for laptops. Readers study books brought to them from the library's closed stacks. There are special rooms for notable authors and scholars, many of whom have done important research and writing at the Library. But the Library has always been about more than scholars, during the Great Depression, many ordinary people, out of work, used the Library to improve their lot in life (as they still do).<ref name=plhist/> |

|||

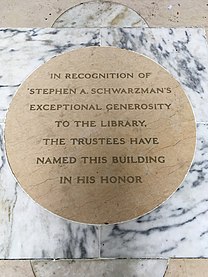

The Main Branch became popular after its opening and saw four million annual visitors by the 1920s. It formerly contained a [[circulating library]], though the circulating division of the Main Branch moved to the nearby [[Mid-Manhattan Library]] in 1970. Additional space for the library's stacks was constructed under adjacent Bryant Park in 1991, and the branch's Main Reading Room was restored in 1998. A major restoration from 2007 to 2011 was underwritten by a $100 million gift from businessman [[Stephen A. Schwarzman]], for whom the branch was subsequently renamed. The branch underwent another expansion starting in 2018. The Main Branch has been featured in many television shows and films. |

|||

The building was declared a [[National Historic Landmark]] in 1965.<ref name="nhlsum"/> |

|||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

|||

==The building== |

|||

==History== |

|||

Marble on the library building is about three feet thick, and the building is marble and brick all the way through. The exterior is comprised of 20,000 blocks of stone (each one numbered in preparation for a renovation announced in 2007). It stretches 390 feet along Fifth Avenue.<ref name=nyt1>Pogrebin, Robin, "A Centennial Face-Lift For a Beaux-Arts Gem: Restoration of Library Facade Begins With Visions of a Nightly Sectacle", article, ''[[The New York Times]]'', page B1, [[December 20]], [[2007]]</ref> |

|||

[[File:Remnant of Croton Distribution Reservoir.jpg|thumb|left|A remnant of the Croton distribution reservoir, seen at the foundation of the South Court in 2014]] |

|||

The consolidation of the [[Astor Library|Astor]] and [[Lenox Library (New York City)|Lenox]] Libraries into the [[New York Public Library]] in 1895,<ref name="nycl1 p. 2" /><ref name="Lemos p. 288">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=288}}</ref> along with a large bequest from [[Samuel J. Tilden]] and a donation of $5.2 million from [[Andrew Carnegie]],<ref>{{Cite news |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1901/03/17/117957380.html |title=City Will Accept Mr. Carnegie's Libraries: Formal Action by the Board of Estimate to Be Taken Tomorrow |date=March 17, 1901 |work=The New York Times |access-date = July 25, 2017}}</ref> allowed for the creation of an enormous library system.<ref name="NYTimes-NewLibraryReady-1910" /> The libraries had a combined 350,000 items after the merger, which was relatively small compared to other library systems at the time.<ref name="Postal p. 2">{{harvnb|ps=.|Postal|2017|p=2}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|ps=.|Hewitt et al.|2006|p=415}}</ref> As a point of civic pride, the New York Public Library's founders wanted an imposing main branch.<ref name="nycl1 p. 2">{{harvnb|ps=.|Landmarks Preservation Commission|1967|p=2}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|ps=.|Reed|2011|pp=1–10}}</ref> While the [[American Museum of Natural History]] and the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]]'s [[The Met Fifth Avenue|Fifth Avenue branch]] were both located on prominent sites facing [[Central Park]] in [[Manhattan]], there was no such site available for a main library building; furthermore, most of the city's libraries were either private collections or small branch libraries.<ref name="Lemos p. 287">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=287}}</ref> |

|||

Two stone lions lie at either side of the stairway to the entrance. The famous lions guarding the entrance were sculpted by [[Edward Clark Potter]]. Their original names, "Leo Astor" and "Leo Lenox", in honor of the library's founders, were transformed into Lord Astor and Lady Lenox (although both lions are male), and in the [[1930s]] they were nicknamed "Patience" and "Fortitude" by Mayor [[Fiorello LaGuardia]]. He chose these names because he felt that the citizens of New York would need to possess these qualities to see themselves through the [[Great Depression]]. Patience is on the south side (the left as one faces the main entrance) and Fortitude on the north.<ref name=plhist/> |

|||

== |

=== Development === |

||

==== Site and design selection ==== |

|||

[[Image:New York Public Library Wikipedia.jpg|thumb|right|350px|New York Public Library Elevation]] |

|||

Several sites were considered, including those of the Astor and Lenox Libraries.<ref name="Postal p. 1">{{harvnb|ps=.|Postal|2017|p=1}}</ref> In March 1896, the trustees of the libraries ultimately chose a new site along Fifth Avenue between 40th and 42nd Streets, because it was centrally located between the Astor and Lenox Libraries.<ref name="Postal p. 2" /><ref>{{cite web |date=March 26, 1895 |title=Public Library's Home: A Strong Feeling in Favor of the Fifth Avenue Reservoir Site |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1895/03/26/archives/public-librarys-home-a-strong-feeling-in-favor-of-the-fifth-avenue.html |access-date=December 17, 2018 |website=The New York Times |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 286">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=286}}</ref> At the time, it was occupied by the obsolete [[Croton Distributing Reservoir|Croton Reservoir]],<ref name="Postal p. 2" /><ref name="Lemos p. 286" /> remnants of which still exist on the library floor.<ref name="fny">{{cite web | last=Carlson | first=Jen | title=This Massive Reservoir Used To Be In Midtown | website=Gothamist | date=January 16, 2015 | url=https://gothamist.com/arts-entertainment/this-massive-reservoir-used-to-be-in-midtown | access-date=July 18, 2022}}</ref> The library's trustees convinced mayor [[William L. Strong]] to give them the reservoir site, after they gave him studies showing that the size of New York City's library collection lagged behind those of many other cities.<ref name="Lemos pp. 288–289">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|pp=288–289}}</ref> Dr. John Shaw Billings, who was named the first director of the New York Public Library, had created an early sketch for a massive reading room on top of seven floors of book-stacks, combined with the fastest system for getting books into the hands of those who requested to read them.<ref name="Postal p. 3">{{harvnb|ps=.|Postal|2017|p=3}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 289">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=289}}</ref> His design for the new library, though controversial for its time,<ref name="Lemos pp. 289–290">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|pp=289–290}}</ref> formed the basis of the Main Branch.<ref name="Postal p. 3" /><ref name="Lemos p. 289" /> Once the Main Branch was opened, the Astor and Lenox Libraries were planned to close, and their functions were planned to be merged into that of the Main Branch.<ref name="Postal p. 2" /> |

|||

In May 1897, the [[New York State Legislature]] passed a bill allowing the site of the Croton Reservoir to be used for a public library building.<ref name="Postal p. 2" /><ref name="NYTimes-LibraryBlocked-1898" /> The [[Society of Beaux-Arts Architects]] hosted an [[architectural design competition]] for the library, with two rounds. The rules of the competition's first round were never published, but they were used as the basis for later design competitions.<ref name="Lemos pp. 290–291">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|pp=290–291}}</ref> Entrants submitted 88 designs,<ref>{{cite web |title=New York Public Library: Eighty-Eight Designs Submitted for the Building—Twelve Will Be Selected |website=The New York Times |date=July 17, 1897 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1897/07/17/archives/new-york-public-library-eightyeight-designs-submitted-for-the.html |access-date = December 17, 2018}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 291">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=291}}</ref> of which 12 were selected for a semi-finalist round and six went on to a finalist round.<ref>{{cite web |title=Public Library Designs: Competition Closed, and the Jury Will Select Three Plans |website=The New York Times |date=November 2, 1897 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1897/11/02/archives/public-library-designs-competition-closed-and-the-jury-will-select.html |access-date = December 17, 2018}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 291" /> About a third of the designs, 29 in total, followed the same design principles outlined in Billings's original sketch. Each of the semifinalist designs were required to include specific architectural features, including limestone walls; a central delivery desk; reading rooms with large windows; and stacks illuminated by sunlight.<ref name="Lemos p. 291" /> The six finalists were selected by a jury composed of library trustees and architects. The jury relaxed the requirement that the proposals adhere to a specific floor plan after [[McKim, Mead & White]], which had received the most votes from the jury, nearly withdrew from the competition.<ref name="Lemos pp. 291–292">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|pp=291–292}}</ref> All of the finalist designs were in the Beaux-Arts style.<ref name="Lemos p. 291" /> |

|||

The consolidation of several libraries into the New York Public Library in 1901, along with the large Tilden bequest and the Carnegie donation, allowed for the creation of an enormous library system befitting the nation's largest city, but the founders also wanted an imposing main branch. A prominent, central site for it was available at the two-block section of Fifth avenue between 40th and 42nd streets, then occupied by the [[Croton Distributing Reservoir|Croton Reservoir]], which was obsolete and no longer needed. Dr. John Shaw Billings who was named first director of the New York Public Library seized the opportunity. He knew exactly what he wanted there. His design for the new library became the basis of the landmark building that became the central Research Library (now known as the Humanities and Social Science Library) on [[Fifth Avenue]].<ref name=plhist>[http://www.nypl.org/pr/history.cfm]Web page titled "History" at the New York Public Library Web site, accessed [[December 20]], [[2007]]</ref> |

|||

Ultimately, in November 1897, the relatively unknown firm of [[Carrère and Hastings]] was selected to design and construct the new library.<ref name="nyt-1897-11-12">{{Cite news |date=November 12, 1897 |title=The New Public Library; Carrere & Hastings's Design for a Great Building Adopted by the Trustees |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1897/11/12/archives/the-new-public-library-carrere-hastingss-design-for-a-great.html |access-date=January 20, 2023 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 292">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=292}}</ref> The jury named the firm of [[Howard & Cauldwell]] and McKim, Mead, & White as runners-up.<ref name="Lemos p. 292" /> Carrère and Hastings created a model for the future library building, which was exhibited at [[New York City Hall]] in 1900.<ref>{{cite web |title=Model of the New Library: Now on Exhibition in the Governor's Room at City Hall |website=The New York Times |date=December 30, 1900 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1900/12/30/archives/model-of-the-new-library-now-on-exhibition-in-the-governors-room-at.html |access-date = December 17, 2018}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 296">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=296}}</ref> Whether [[John Mervin Carrère]] or [[Thomas Hastings (architect)|Thomas S. Hastings]] contributed more to the design is in dispute, but both architects are honored with busts located at the bottoms of each of Astor Hall's two staircases.<ref name="Postal p. 3" /> In a later interview with ''The New York Times'', Carrère stated that the library would contain "twenty-five or thirty different rooms", each with their own specialty; "eighty-three miles of books" in its [[Library stack|stacks]]; and a general reading room that could fit a thousand guests.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1909/02/14/archives/where-a-thousand-may-read-architect-carrere-describes-future-new.html |title=Where a Thousand May Read: Architect Carrere Describes Future New York Public Library |date=February 14, 1909 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 18, 2018}}</ref> During the design process, Hastings had wanted to shift the library building closer to Sixth Avenue, and he also proposed sinking 42nd Street to create a forecourt for the library, but both plans were rejected.<ref name="Lemos p. 306">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=306}}</ref> The [[New York City Board of Estimate]] approved Carrère and Hastings's plans for the library in December 1897.<ref>{{cite web |date=December 2, 1897 |title=The New Public Library: Board of Estimate and Apportionment Approves the Carrere & Hastings Design |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1897/12/02/archives/the-new-public-library-board-of-estimate-and-apportionment-approves.html |access-date=December 17, 2018 |website=The New York Times |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 294">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=294}}</ref> |

|||

Billings's plan called for a huge reading room on top of seven floors of bookstacks combined with the fastest system for getting books into the hands of those who requested to read them. Following a competition among the city's most famous architects, the relatively unknown firm of [[Carrère and Hastings]] was selected to design and construct the new library. The result, regarded as the apex of Beaux-Arts design, was the largest marble structure up to that time in the United States. The cornerstone was laid in [[May]] [[1902]].<ref name=plhist/> |

|||

[[Image:NYPL portals.JPG|thumb|left|Cross-view of classical details in the entrance portico]] |

|||

==== Construction ==== |

|||

Work progressed slowly but steadily on the Library which eventually cost $9 million to build. During the summer of [[1905]], huge columns were put into place and work on the roof was begun. By the end of 1906, the roof was finished and the designers commenced five years of interior work. In 1910, 75 miles of shelves were installed to house the collections that were set to make their home there, with plenty of space left for future acquisitions. It took a whole year to move and install the books that were in the Astor and Lenox libraries.<ref name=plhist/> |

|||

Construction was delayed by the objections of mayor [[Robert Anderson Van Wyck]], who expressed concerns that the city's finances were unstable.<ref name="NYTimes-LibraryBlocked-1898">{{cite web |title=Public Library Blocked: Mayor Van Wyck Opposes an Issue of $150,000 in Bonds to Prepare the Site |website=The New York Times |date=March 24, 1898 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1898/03/24/archives/public-library-blocked-mayor-van-wyck-opposes-an-issue-of-150000-in.html |access-date = December 17, 2018}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 2952">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=295}}</ref> As a result, the planned library was delayed for a year.<ref name="Lemos p. 2952" /> The Board of Estimate authorized a bond measure of $500,000 in May 1899.<ref name="Postal p. 2" /> The next month, contractor Eugene Lentilhon started excavating the Croton Reservoir,<ref name="Lemos p. 2952" /><ref name="nyt-1899-06-08">{{Cite news |date=June 8, 1899 |title=A Woman Sues John J. O'Brien; Maude L. Curran Seeks to Recover $1,608.75 from the ex-Aiderman. |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1899/06/08/archives/a-woman-sues-john-j-obrien-maude-l-curran-seeks-to-recover-160875.html |access-date=January 20, 2023 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> and workers began digging through the reservoir's {{convert|25|ft|m|adj=mid|-thick}} wall.<ref name="Postal p. 2" /> After spending seven weeks tunneling through the wall, Lentilhon determined that the floor of the reservoir could only be demolished using dynamite.<ref name="Lemos p. 2952" /> Work on the foundation commenced in May 1900,<ref name="NYTimes-NewLibraryReady-1910" /><ref name="Postal p. 4">{{harvnb|ps=.|Postal|2017|p=4}}</ref> and much of the Croton Reservoir had been excavated by 1901.<ref name="Postal p. 2" /><ref name="Lemos p. 2952" /> In November 1900, work was hindered by a water main break that partly flooded the old reservoir.<ref>{{Cite news |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1900/11/15/archives/big-water-main-bursts-pipe-in-fortysecond-street-breaks-but-causes.html |title=Big Water Main Bursts |date=November 15, 1900 |work=The New York Times|access-date=August 13, 2019}}</ref> [[Norcross Brothers]] received the general contract,<ref name="Postal p. 4" /><ref name="Lemos p. 296" /> although this was initially controversial because the firm was not the lowest bidder.<ref>{{cite web |title=Trouble over the Library Contract: The Lowest Bidder Asserts that He Was Unjustly Treated |website=The New York Times |date=June 26, 1901 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1901/06/26/archives/trouble-over-the-library-contract-the-lowest-bidder-asserts-that-he.html |access-date = December 18, 2018}}</ref> After a private ceremony to mark the start of construction was held in August 1902,<ref name="Postal p. 4" /> a ceremonial [[cornerstone]] was laid on November 10, 1902.<ref name="Gray 1911 p. 563">{{cite magazine |last=Gray |first=David |date=March 1911 |title=A Temple of Modern Education: New York's New Public Library |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9UhDAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA563 |magazine=Harper's Monthly Magazine |volume=122 |issue=730 |pages=562–564 |access-date=December 20, 2018}}</ref><ref name="Lemos p. 2952" /><ref>{{cite web |title=Senator Dubois Explains Idaho Republican Victory: It Is Attributable to Passage of Irrigation Act by Last Congress, He Says |website=The New York Times |date=November 11, 1902 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1902/11/11/archives/senator-dubois-explains-idaho-republican-victory-it-is-attributable.html |access-date = December 18, 2018}}</ref> The cornerstone contained a box of artifacts from the library and the city.<ref name="NYPL-Facts">{{cite web |url=https://www.nypl.org/about/locations/schwarzman/facts |title=Stephen A. Schwarzman Building Facts |date=November 10, 1902 |website=The New York Public Library |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> The architects awarded the contract for the library's stacks to [[Snead & Company]]; for drainage and plumbing to M. J. O'Brien; for interior finishes to the John Peirce Company; and for electric equipment to the Lord Electric Company.<ref name="Lemos p. 296" /> |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

On [[May 23]], [[1911]], the main branch of the New York Public Library was officially opened. The ceremony was presided over by President [[William Howard Taft]] and was attended by Governor [[John Alden Dix]] and Mayor [[William J. Gaynor]].<ref name=plhist/> |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| width = 250 |

|||

| image1 = Exterior marble work - NYPL - crop.tiff |

|||

| caption1 = Progress on the marble work, {{circa|1903}} |

|||

| image2 = New York Public Library 1908c.jpg |

|||

| caption2 = Front elevation in 1908; the lion statues at the Main Branch had not yet been installed. |

|||

}} |

|||

Work progressed gradually on the library: the basement was completed by 1903, and the first floor by 1904.<ref name="Postal p. 4" /> However, exterior work was delayed due to the high cost of securing large amounts of marble, as well as frequent labor strikes.<ref name="Lemos p. 296" /> When the Norcross Brothers' contract expired in August 1904, the exterior was only halfway completed.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26320473/extension_of_contract_not_asked/ |title=Extension of Contract Not Asked |date=August 25, 1904 |work=New-York Tribune |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=4 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> During mid-1905, giant columns were put into place and work on the roof was begun; the roof was finished by December 1906.<ref name="NYTimes-NewLibraryReady-1910">{{cite web |title=New Library Ready Early Next Year: That Is, the Great Marble Structure Will Open if There Are No More Delays |website=The New York Times |date=May 2, 1910 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1910/05/02/archives/new-library-ready-early-next-year-that-is-the-great-marble-struc.html |access-date = December 16, 2018}}</ref> The remaining contracts, totaling $1.2 million, concerned the installation of furnishings in the interior.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26320632/last_library_work/ |title=Last Library Work |date=January 28, 1907 |work=New-York Tribune |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=4 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> The interior and exterior were largely constructed simultaneously.<ref name="Lemos p. 296" /> The building's exterior was mostly done by the end of 1907.<ref name="Postal p. 4" /><ref name="Lemos p. 296" /> The pace of construction was generally sluggish; in 1906, an official for the New York Public Library stated that some of the exterior and most of the interior was not finished.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26320323/more_library_delay/ |title=More Library Delay |date=December 16, 1906 |work=New-York Tribune |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=24 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:NYPL CatalogRoom.JPG|thumb|Entrance to the Public Catalog Room]] |

|||

Contractors started painting the main reading room and catalog room in 1908, and began installing furniture the following year.<ref name="Postal p. 4" /> Starting in 1910, around {{convert|75|mi|km}} worth of shelves were installed to hold the collections that were designated for being housed there, with substantial room left for future acquisitions.<ref name="plhist">{{cite web |title=History of The New York Public Library |url=https://www.nypl.org/help/about-nypl/history |access-date=December 17, 2018 |website=The New York Public Library}}</ref> It took one year to transfer and install the books from the Astor and Lenox Libraries.<ref>{{cite web |title=Moving a Million Books into the New Library: Transfer of the Lenox and Astor Library Contents to the Beautiful New Building at Forty-Second Street and Fifth Avenue a Big Undertaking |website=The New York Times |date=April 16, 1911 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1911/04/16/archives/moving-a-million-books-into-the-new-library-transfer-of-the-lenox-a.html |access-date = December 16, 2018}}</ref> Late in the construction process, a proposal to install a municipal light plant in the basement of the Main Branch was rejected.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1909/03/20/archives/city-light-plant-for-library-beaten-board-of-estimate-votes-it-down.html |title=City Light Plant for Library Beaten: Board of Estimate Votes It Down After Proof That it Would Save $27,000 Yearly |date=March 20, 1909 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 18, 2018}}</ref> By late 1910, the library was nearly completed,<ref name="nyt-190-12-11">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1910/12/11/archives/new-yorks-fine-new-library-nearly-completed-will-be-ready-before.html |title=New York's Fine New Library Nearly Completed: Will Be Ready Before the Contract Time, and Needs Only the Interior Furnishings |date=December 11, 1910 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> and officials forecast an opening date of May 1911.<ref>{{Cite news |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1910/11/26/archives/new-library-nearly-done-contractors-now-expect-to-complete-their.html |title=New Library Nearly Done: Contractors Now Expect to Complete Their Work by May 1 |date=November 26, 1910 |work=The New York Times |access-date = December 18, 2018}}</ref> Carrère died before the building was opened, and in March 1911, two thousand people viewed his coffin in the library's rotunda.<ref>{{Cite news |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1911/03/04/archives/2000-view-body-of-john-m-carrere-prominent-men-and-women-in-throng.html |title=2,000 View Body of John M. Carrere: Prominent Men and Women in Throng That Passes Coffin in New Public Library Rotunda |date=March 4, 1911 |work=The New York Times |access-date = December 18, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

The following day, [[May 24]], the public was invited. The response was sensational. Tens of thousands thronged to the Library's "jewel in the crown." The opening day collection consisted of more than 1,000,000 volumes. The New York Public Library instantly became one of the nation's largest libraries and a vital part of the intellectual life of America. True to Dr. Billings' plan, library records for that day show that one of the very first items called for was N. I. Grot's ''Nravstvennye idealy nashego vremeni'' ("Ethical Ideas of Our Time") a study of [[Friedrich Nietzsche]] and [[Leo Tolstoy]]. The reader filed his slip at 9:08 a.m. and received his book just six minutes later.<ref name=plhist/> |

|||

===Opening=== |

|||

[[Image:MApDivision6618.JPG|thumb|left|The Map Division]] |

|||

On May 23, 1911, officials held a ceremony to open the main branch of the New York Public Library. U.S. president [[William Howard Taft]] presided over the ceremony, whose 15,000 guests included governor [[John Alden Dix]] and mayor [[William Jay Gaynor]].<ref name="NYTimes-Opened-1911">{{cite web |title=City's $29,000,000 Library Is Opened: Golden Key of the Marble Structure Delivered, President Taft Making the Principal Address |website=The New York Times |date=May 24, 1911 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1911/05/24/archives/citys-29000000-library-is-opened-golden-key-of-the-marble-structure.html |access-date = December 16, 2018}}</ref><ref name="n26326242">{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26326242/new_yorks_public_library_opened/ |title=New York's Public Library Opened |date=May 23, 1911 |work=Buffalo Commercial |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=2 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref><ref name="Lemos pp. 296–297">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|pp=296–297}}</ref> The public was invited the following day, May 24,<ref name="Lemos p. 285">{{harvnb|Hewitt et al.|2006|ps=.|p=285}}</ref><ref name=nyt-1911-05-25>{{Cite news|date=May 25, 1911|title=50,000 Visitors See New Public Library; Attendants Busy Preventing Confusion as They Inspect the Great Building.|language=en-US|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1911/05/25/archives/50000-visitors-see-new-public-library-attendants-busy-preventing.html|access-date=January 20, 2023|issn=0362-4331}}</ref> and tens of thousands went to the Library's "jewel in the crown".<ref name="plhist" /> The first item called for was ''Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded'' by [[Delia Bacon]], although this was a publicity stunt, and the book was not in the Main Branch's collection at the time.<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /><ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1961/05/26/archives/library-tricked-on-first-request-clerk-reveals-failure-in-11-was-a.html |title=Library Tricked on First Request: Clerk Reveals 'Failure' in '11 Was a Publicity Stunt |last=Anderson |first=David |date=May 26, 1961 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> The first item actually delivered was N. I. Grot's ''{{lang|ru|Nravstvennye idealy nashego vremeni}}'' ("Ethical Ideas of Our Time"), a study of [[Friedrich Nietzsche]] and [[Leo Tolstoy]]. The reader filed his slip at 9:08 a.m. and received his book seven minutes later.<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /><ref name="Postal p. 5" /> |

|||

The Beaux-Arts Main Branch was the largest marble structure up to that time in the United States,<ref name="plhist" /> with shelf space for 3.5 million volumes spread across {{Convert|375000|ft2|m2}}.<ref name="n26326242" /> The projected final cost was $10 million, excluding the cost of the books and the land, representing a fourfold increase over the initial cost estimate of $2.5 million.<ref name="n26326242" /><ref>{{Cite news |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1910/05/02/archives/new-library-ready-early-next-year-that-is-the-great-marble-struc.html |title=New Library Ready Early Next Year: That Is, the Great Marble Structure Will Open if There Are No More Delays |date=May 2, 1910 |work=The New York Times |access-date = December 18, 2018}}</ref> The structure ultimately cost $9 million to build,<ref name="nycl1 p. 1">{{harvnb|ps=.|Landmarks Preservation Commission|1967|p=1}}</ref><ref name="NYTimes-Opened-1911" /> over three times as much as originally projected.<ref name="Postal p. 5">{{harvnb|ps=.|Postal|2017|p=5}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|ps=.|Hewitt et al.|2006|p=322}}</ref> Because there were so many visitors during the first week of the Main Branch's opening, the New York Public Library's directors initially did not count the number of visitors, but guessed that 250,000 patrons were accommodated during the first week.<ref>{{Cite news |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1911/06/01/archives/great-crowds-at-library-three-interesting-exhibitions-mark-the.html |title=Great Crowds at Library: Three Interesting Exhibitions Mark the Second Week in the New Building |date=June 1, 1911 |work=The New York Times |access-date = December 18, 2018}}</ref> The construction of the Main Branch, along with that of the nearby [[Grand Central Terminal]], helped to revitalize Bryant Park.<ref name="Postal p. 4" /> |

|||

Over the decades, the research collection grew until, by the 1970s, it was clear that eventually the collection would outgrow the existing structure. So it was decided to make the library bigger by burrowing underground toward [[Bryant Park]]. In the [[1980s]] the central research library added more than 125,000 square feet (12,000 m²) of space and literally miles of bookshelf space to its already vast storage capacity to make room for future acquisitions. This expansion required a major construction project in which Bryant Park, directly west of the library, was closed to the public and excavated. The new library facilities were built below ground level. The park was then restored on top of the underground facilities and re-opened to the public. |

|||

=== 20th-century growth === |

|||

On [[July 17]], [[2007]], the building was briefly evacuated and the surounding area was cordoned off by New York police because of a suspicious package found across the street. It turned out to be a bag of old clothes.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://twitter.com/BreakingNewsOn/statuses/154583392 | title=New York Public Library being evacuated | date=17 July, 2007 | accessdate=2007-07-17 | work=Twitter}}</ref> |

|||

The Main Branch came to be regarded as an architectural landmark. As early as 1911, ''Harper's Monthly'' magazine praised the architecture of "this interesting and important building".<ref name="Gray 1911 p. 563" /> In 1971, ''New York Times'' architectural critic [[Ada Louise Huxtable]] wrote, "As urban planning, the library still suits the city remarkably well" and praised its "gentle monumentality and knowing humanism".<ref>{{Cite news |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1971/01/24/archives/library-as-friend.html |title=Architecture |last=Huxtable |first=Ada Louise |date=January 24, 1971 |work=The New York Times |access-date = December 20, 2018}}</ref> Architectural historian Kate Lemos wrote in 2006 that the library "has held a commanding presence at the bustling corner of 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue as the neighborhood grew up around it".<ref name="Lemos p. 285" /> |

|||

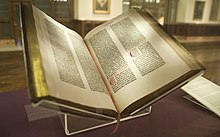

The Main Branch also took on importance as a major research center.<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /><ref name="n26438806">{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26438806/ |title=The Tuition Is Free at 'Every Man's University' |date=August 14, 1976 |work=Democrat and Chronicle |access-date = December 22, 2018 |location=Rochester, NY |page=8 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> [[Norbert Pearlroth]], who served as a researcher for the ''[[Ripley's Believe It or Not!]]'' book series, perused an estimated 7,000 books annually from 1923 to 1975.<ref name="n26438806" /> Other patrons included First Lady of the United States [[Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis]]; writers [[Alfred Kazin]], [[Norman Mailer]], [[Frank McCourt]], [[John Updike]], [[Cecil Beaton]], [[Isaac Bashevis Singer]], and [[E. L. Doctorow]]; actors [[Helen Hayes]], [[Marlene Dietrich]], [[Lillian Gish]], [[Diana Rigg]], and Princess [[Grace Kelly]] of Monaco; playwright [[Somerset Maugham]]; film producer [[Francis Ford Coppola]]; journalists [[Eliezer Ben-Yehuda]] and [[Tom Wolfe]]; and boxer [[Joe Frazier]].<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /> The Main Branch was also used for major works and invention. [[Edwin H. Land|Edwin Land]] conducted research at the building for his later invention, the [[Land Camera]], while [[Chester Carlson]] invented [[Xerox]] photocopiers after researching [[photoconductivity]] and electrostatics at the library.<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /><ref name="n26438806" /> During [[World War II]], American soldiers decoded a Japanese [[cipher]] based on a Mexican phone book whose last remaining copy among [[Allies of World War II|Allied]] nations existed at the Main Branch.<ref name="n26438806" /> |

|||

[[Image:NYC Public Library Research Room Jan 2006.jpg|thumb|center|500px|A panoramic view of the Rose Main Reading Room, facing south.]] |

|||

==== 1920s and 1930s ==== |

|||

In the three decades before 2007, the building's interior was gradually renovated. In December 2005, for instance, the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division space, with richly carved wood, marble, and metalwork, was restored.<ref name=nyt1/> |

|||

[[File:New York Public Library 1910a.jpg|thumb|Back elevation, 1910s|alt=]] |

|||

Initially, the Main Branch was opened at 1 p.m. on Sundays and 9 a.m. on all other days, and it closed at 10 p.m. each day. This was to encourage patrons to use the new library.<ref name="Postal p. 5" /><ref name="Central Building Guide p. 7">{{harvnb|ps=.|Central Building Guide|1912|pp=7, 9}}</ref> By 1926, the library was heavily patronized, with up to 1,000 people per hour requesting books. The library was most used between 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. and 3:30 to 5:50 p.m., and from October through May. The most highly requested books were those for economics and American and English literature, though during [[World War I]] geography books were the most demanded because of the ongoing war.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/58194013/ |title=Behind the Scenes at the Library |last=Gee |first=Henrietta |date=April 18, 1926 |work=Brooklyn Daily Eagle |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=107 |via=Brooklyn Public Library; Newspapers.com}}</ref> It was estimated that 4{{nbsp}}million people per year used the Main Branch in 1928, up from 2{{nbsp}}million in 1918<ref name="Barnard 1928">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1928/09/16/archives/the-silent-adviser-of-all-new-york-the-public-library-serving-every.html |title=The Silent Adviser of All New York: The Public Library, Serving Every Tongue and Quest, Will Expand Its Outgrown Fifth Avenue Building |last=Barnard |first=Eunice Fuller |date=September 16, 1928 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> and 3{{nbsp}}million in 1926.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1929/06/13/archives/3000000-visited-library-in-year-10877171-books-issued-for-home-use.html |title=3,000,000 Visited Library in Year: 10,877,171 Books Issued for Home Use in the City, Report Shows |date=June 13, 1929 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> There were 1.3{{nbsp}}million books requested by nearly 600,000 people through call slips in 1927.<ref name="nyt-1928-08-24">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1928/08/24/archives/library-to-build-5th-av-extensions-plans-two-wings-and-new-unit-in.html |title=Library to Build 5th. Av. Extensions: Plans Two Wings and New Unit in Bryant Park Subject to City's Approval |date=August 24, 1928 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> By 1934, though annual patronage held steady at 4{{nbsp}}million visitors, the Main Branch had 3.61{{nbsp}}million volumes in its collection.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26434418/ |title=Readers Utilizing Leisure Hours Increase Library Attendance 40% |date=September 6, 1934 |work=The Sun and the Erie County Independent |access-date = December 18, 2018 |location=Hamburg, NY |page=8 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> |

|||

On December 20, 2007, the library announced it will undertake a three-year, $50 million renovation of the building exterior, which has suffered damage from weathering and automobile exhaust. The Vermont marble structure and the scuplture elements on it were to be cleaned, 3,000 cracks were to be repaired, and restoration work would also be done on the roof, stairs, and plazas. All of the work was scheduled to be completed by the centennial in 2011.<ref>[http://www.nypl.org/press/2007/FacadeRestor.cfm]Web page (news release?) titled "The New York Public Library Will Restore its Fifth Avenue Building's Historic Facade / Project to be Completed in Time for Building's 2011 Centennial / (New York City, December 20, 2007)" at the New York Public Library Web site, accessed [[December 20]], [[2007]]</ref> New York Mayor [[Michael R. Bloomberg]], on behalf of the library, asked the mayor of Paris to lend to New York the services of [[François Jousse]], the city engineer responsible for lighting Paris' monuments, structures and official buildings. "My ambition is for this to be the building you simply must see in New York at nighttime because it is so beautiful and it is so important," library director [[Paul LeClerc]] said in 2007.<ref name=nyt1/> |

|||

Due to the increased demand for books, new shelves were installed in the stockrooms and the cellars by the 1920s to accommodate the expanded stacks. However, this still proved to be insufficient.<ref name="nyt-1928-08-24" /> The New York Public Library announced an expansion of the Main Branch in 1928.<ref name="Barnard 1928" /> Thomas Hastings prepared plans for new wings near the north and south sides of the structure, which would extend eastward toward Fifth Avenue, as well as a storage annex in Bryant Park to the west.<ref name="nyt-1928-08-24" /> The expansion was planned to cost $2{{nbsp}}million, but was never built.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/59868662 |title=$2,000,000 Annex to Public Library in New Projects |date=September 30, 1928 |work=Brooklyn Daily Eagle |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=47 |via=Brooklyn Public Library; Newspapers.com}}</ref> After Hastings died in 1929, it was revealed that his [[Will and testament|will]] contained $100,000 for modifications to the facade, with which he had been dissatisfied.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1929/11/07/archives/hastings-will-asks-change-in-library-architect-of-building-on-fifth.html |title=Hastings Will Asks Change In Library: Architect of Building on Fifth Avenue Wanted Its Facade Improved |date=November 7, 1929 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

As of 2004, streaks were already blackening the white marble and pollution and moisture were corroding the ornamental statuary, causing architectural details to erode, including the edges of cornices and features on carved faces. "Tiny particles of rubber scattered by passing car tires have accumulated on the building, mixing gradually with water to turn the marble into gypsum, which causes the outer layer to crumble in a sugaring effect," according to an article in ''The New York Times''.<ref name=nyt1/> |

|||

A theater collection was installed in the Main Reading Room in 1933.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/59974200/ |title=Stage History |date=June 4, 1933 |work=Brooklyn Daily Eagle |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=22 |via=Brooklyn Public Library; Newspapers.com}}</ref> Two years later, the Bryant Park Open-Air Reading Room was established, operating during the summer. The reading room was meant to improve the morale of readers during the [[Great Depression]], and it operated until 1943, when it closed down due to a shortage of librarians.<ref name="Collins 2003">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/27/nyregion/leaves-of-grass-anyone-a-reading-room-returns-to-bryant-park.html |title='Leaves of Grass,' Anyone? A Reading Room Returns to Bryant Park |last=Collins |first=Glenn |date=May 27, 2003 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> In 1936, library trustee George F. Baker gave the Main Branch forty issues of the ''[[New-York Gazette]]'' from the 18th century, which had not been preserved anywhere else.<ref>{{cite web |title=Library Acquires Lost City History; It Is Contained in 40 Copies of The New-York Gazette |website=The New York Times |date=June 8, 1936 |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1936/06/08/archives/library-acquires-lost-city-history-it-is-contained-in-40-copies-of.html |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> In 1937, the doctors [[Albert Berg (surgeon)|Albert]] and Henry Berg made an offer to the library's trustees to donate their collections of rare English and American literature. After Henry died, the collection was dedicated in his memory.<ref name="NYPL-Berg">{{cite web |url=https://www.nypl.org/about/divisions/berg-collection-english-and-american-literature |title=About the Berg Collection |website=The New York Public Library |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> The Berg Reading Room was formally dedicated in October 1940.<ref name="nyt-1940-10-12">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1940/10/12/archives/berg-memorial-room-which-was-dedicated-yesterday.html |title=Berg Memorial Room Which Was Dedicated Yesterday |date=October 12, 1940 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

By late 2007, library officials had not yet decided whether to try to restore damaged sculptural elements or just clean and "stabilize" them. Cleaning would be done either with lasers or by applying poultices and peeling them off.<ref name=nyt1/> |

|||

During the 1930s, [[Works Progress Administration]] (WPA) workers helped maintain the Main Branch. Their tasks included upgrading the heating, ventilation, and lighting systems; refitting the treads on the branch's marble staircases; painting the bookshelves, walls, ceilings, and masonry; and general upkeep.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/52640519 |title=Library Branches Renovated by 1,300 On Rolls of WPA |date=September 5, 1935 |work=Brooklyn Daily Eagle |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=16 |via=Brooklyn Public Library; Newspapers.com}}</ref><ref name="nyt-1935-06-30">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1935/06/30/archives/relief-workers-repair-libraries-all-citys-buildings-including-that.html |title=Relief Workers Repair Libraries: All City's Buildings, Including That at 5th Av. and 42d St., Are Being Renovated |date=June 30, 1935 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> The WPA allocated $2.5{{nbsp}}million for the building's maintenance.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1935/08/22/archives/2500000-wpa-fund-for-public-library-grant-to-be-used-for-repairs.html |title=$2,500,000 WPA Fund for Public Library: Grant to Be Used for Repairs and Improvements at Main Building and Branches |date=August 22, 1935 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> In January 1936, it was announced that the Main Branch's roof would be renovated as part of a seven-month WPA project.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1936/02/19/archives/wpa-to-build-new-roof-for-the-public-library.html |title=WPA to Build New Roof For the Public Library |date=February 19, 1936 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

==The NYPL in popular culture== |

|||

[[Image:New York Public Library 060622.JPG|thumb|At the entrance to the New York Public Library.]] |

|||

=== |

==== 1940s to 1970s ==== |

||

In 1942, the main exhibition room was converted into office space and partitioned off.<ref name="nyt-1981-12-25">{{Cite news |last=Carmody |first=Deirdre |date=December 25, 1981 |title=Main Library to Revive Unused Exhibition Area |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/12/25/nyregion/main-library-to-revive-unused-exhibition-area.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> During World War II, the fifteen large windows in the Main Reading Room were blacked out, though they were later uncovered.<ref name="Reif 1999" /> In the following years, the Main Reading Room became neglected: broken lighting fixtures were not replaced, and the room's windows were never cleaned.<ref name="Reif 1999">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/04/arts/art-architecture-seeing-a-familiar-haunt-again-but-in-a-new-light.html |title=Art/Architecture: Seeing a Familiar Haunt Again, but in a New Light |last=Reif |first=Rita |date=April 4, 1999 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 20, 2018}}</ref><ref name="n26442935">{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26442935/ |title=New York Public Library restored to grandeur |agency=Associated Press |date=September 29, 1998 |work=Press and Sun-Bulletin |access-date = December 22, 2018 |location=Binghamton, NY |page=10 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> Unlike during World War I, war-related books at the Main Branch did not become popular during World War II.<ref>{{Cite news |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1940/03/14/archives/war-books-losing-favor-at-library-demand-for-such-works-far-less.html |title=War Books Losing Favor At Library: Demand for Such Works Far Less Than That Recorded in 1914 and 1915 |date=March 14, 1940 |work=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> A room for members of the [[United States Armed Forces]] was opened in 1943.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1943/02/11/archives/service-folk-get-room-in-library-special-retreat-is-set-aside-where.html |title=Service Folk Get Room in Library: Special Retreat Is Set Aside Where Men and Women in Uniform May Read |date=February 11, 1943 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> In 1944, the New York Public Library proposed another expansion plan. The stacks' capacity would be increased to 3 million books, and the circulating library in the Main Branch would be moved to a new [[53rd Street Library]].<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1944/06/30/archives/library-additions-planned-for-city-central-building-to-be-greatly.html |title=Library Additions Planned for City: Central Building to Be Greatly Expanded and New One Put Up in Fifty-Third Street |date=June 30, 1944 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> The circulating library at the Main Branch was ultimately kept for the time being, though its single room soon became insufficient to host all of the circulating volumes.<ref name="Campbell 1970">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1970/10/21/archives/dream-of-library-realized-dream-of-a-new-library-is-realized.html |title=Dream of Library Realized |last=Campbell |first=Barbara |date=October 21, 1970 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> Subsequently, in 1949, the library asked the city to take over responsibility for the Main Branch's circulating and children's libraries.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26435066/ |title=Ask City to Take Over Public Library Branch |date=May 6, 1949 |work=New York Daily News |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=408 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> As part of the modernization of the Main Branch, newly delivered books started being processed in that building, rather than at various circulation branch libraries.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1949/12/01/archives/in-the-book-processing-center-of-the-public-library.html |title=In the Book Processing Center of the Public Library |date=November 1, 1949 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref>[[File:Mid Manhattan Library Jul 2020 07.jpg|thumb|The [[Mid-Manhattan Library]], which opened in 1970 and replaced the circulating library at the Main Branch]] |

|||

The building has frequently appeared in feature [[film]]s. It serves as the backdrop for a central plot development in the [[2002]] film ''[[Spider-Man (movie)|Spider-Man]]'' and a major location in the [[2004]] [[apocalyptic science fiction]] film ''[[The Day After Tomorrow]]''. It is also featured prominently in the [[1984]] film ''[[Ghostbusters]]''—a librarian in the basement reports seeing a ghost, which becomes violent when approached. In the [[1978]] film, ''[[The Wiz]]'', Dorothy and Toto stumble across the Library and one of the Library Lions comes alive and joins them on their journey out of Oz. |

|||

The rear of the library's main hall was partitioned off in 1950, creating a bursar's office measuring {{cvt|42|by|13|ft}}.<ref>{{Cite news |date=October 22, 1950 |title=Library Main Hall Soon to Be Altered |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1950/10/22/archives/library-main-hall-soon-to-be-altered.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> Minor repairs at the Main Branch occurred during the 1960s. The city government allocated money for the installation of fire sprinklers in the main branch's stacks in 1960.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1960/08/26/archives/library-will-get-fire-sprinklers-board-of-estimate-allocates-fund.html |title=Library Will Get Fire Sprinklers: Board of Estimate Allocates Fund to Guard 4 Million Volumes at 42d St. |date=August 26, 1960 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> In 1964 contracts were awarded for the installation of a new floor level above the south corridor on the first floor, as well as for replacement of the skylights.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1964/07/20/archives/library-renovation-starting.html |title=Library Renovation Starting |date=July 20, 1964 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> By the mid-1960s, the branch contained 7 million volumes<ref name="n26438462">{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26438462/ |title=Five Sites Listed as Landmarks |agency=Associated Press |date=December 21, 1965 |work=The Post-Standard |access-date = December 18, 2018 |location=Syracuse, NY |page=17 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> and had outgrown its {{Convert|88|mi|km}} of stacks.<ref name="Anderson 1987" /><ref name="Stern (2006) p. 538">{{harvnb|Stern|Fishman|Tilove|2006|ps=.|p=538}}</ref> |

|||

The circulating facilities at the Main Branch continued to grow, and in 1961, the New York Public Library convened a group of six librarians to look for a new facility for the circulating department.<ref name="Campbell 1970" /> The library bought the [[Arnold Constable & Company]] department store at 8 East 40th Street, at the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 40th Street across from the Main Branch.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1961/10/20/archives/5th-ave-building-sold-library-buys-property-at-40th-st-for.html |title=5th Ave. Building Sold: Library Buys Property at 40th St. for Investment |date=October 20, 1961 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> The Main Branch's circulating collection was moved to the [[Mid-Manhattan Library]] in 1970.<ref name="Campbell 1970" /> |

|||

Other films in which the library appears include ''[[42nd Street (film)|42nd Street]]'' (1933), ''[[Portrait of Jennie]]'' (1948), ''[[Breakfast at Tiffany's]]'' (1961), ''[[You're a Big Boy Now]]'' (1966), ''[[Chapter Two]]'' (1979), ''[[Escape from New York]]'' (1981), ''[[Regarding Henry]]'' (1991), ''[[The Thomas Crown Affair]]'' (1999), and [[The Time Machine (2002 film)|''The Time Machine'']] (2002). |

|||

During the 1970s, the New York Public Library as a whole experienced financial troubles,<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1970/02/13/archives/crisis-on-42d-street.html |title=Crisis on 42d Street |date=February 13, 1970 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref> which were exacerbated by the [[1975 New York City fiscal crisis]].<ref name="n26438806" /> As a cost-cutting measure, in 1970, the library decided to close the Main Branch during Sundays and holidays.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1970/12/04/archives/42d-st-library-to-close-on-sundays-holidays.html |title=42d St. Library to Close On Sundays, Holidays |date=December 4, 1970 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref> The library also closed the Main Branch's science and technology division in late 1971 to save money, but private funds allowed the division to reopen in January 1972.<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1972/01/18/archives/library-division-reopens.html |title=Library Division Reopens |date=January 18, 1972 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref> The lions in front of the Main Branch's main entrance were restored in 1975.<ref name="nyt-1975-11-13">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1975/11/13/archives/the-library-lions-get-mudpacks-as-part-of-the-full-beauty-treatment.html |title=The Library Lions Get Mudpacks as Part of the Full Beauty Treatment |date=November 13, 1975 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref> By the end of the decade, the Main Branch was in disrepair and the NYPL trustees were raising money for the research library's continued upkeep.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 538" /><ref name="nyt-1979-02-04">{{Cite news |last=Fraser |first=C. Gerald |date=February 4, 1979 |title=The Library Starts Fund Drive With Ad Campaign on Buses |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1979/02/04/archives/the-library-starts-fund-drive-with-ad-campaign-on-buses-reason-is.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> The NYPL system was so short on funds that the research library was only open 43 hours a week until 1979, when Time Inc. and the Grace Krieble Delmas Foundation jointly donated $750,000 to extend the branch's operating hours.<ref name="nyt-1979-02-04" /> |

|||

===[[Television]]=== |

|||

*The NYPL was featured in the pilot episode of ABC's hit series [[Traveler (TV series)|Traveler]], as the Drexler Museum Of Art, most often as backdrop or a brief meeting place for characters. |

|||

==== 1980s and 1990s ==== |

|||

*In the episode "[[The Day the Earth Stood Stupid]]" in the animated [[television]] series ''[[Futurama]]'', the giant brain is confronted by [[Phillip J. Fry|Fry]] in the library. |

|||

[[Vartan Gregorian]] took over as president of the New York Public Library in 1981.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 538" /><ref>{{Cite news |last=McFadden |first=Robert D. |date=April 16, 2021 |title=Vartan Gregorian, Savior of the New York Public Library, Dies at 87 |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/16/nyregion/vartan-gregorian-dead.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref name="DM p. 89">{{harvnb|Dixon|Morton|1986|ps=.|p=89}}</ref> At the time, many of the Main Branch's interior spaces had been subdivided and extensively modified, with offices in many of the spaces.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 538" /><ref name="DM p. 89" /><ref name="nyt-1982-04-25">{{Cite news |last=Goldberger |first=Paul |date=April 25, 1982 |title=Architecture View; Restoring the Public Library to Its Original Splendor |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1982/04/25/arts/architecture-view-restoring-the-public-library-to-its-original-splendor-p.1.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> The main exhibition room had been turned into an accounting office; the reading room's furniture had metal brackets screwed onto them; and there were lights, wires, and ducts hung throughout the space.<ref name="nyt-1982-04-25" /> Gregorian organized events to raise money for the library, which helped raise funds for the cleaning of the facade and the renovation of the lobby, roof, and lighting system.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Carmody |first=Deirdre |date=July 8, 1982 |title=Public Library, Under Gregorian, Celebrating a Good Year |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1982/07/08/nyregion/public-library-under-gregorian-celebrating-a-good-year.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> Architectural firm [[Davis Brody Bond|Davis Brody & Associates]], architect [[Giorgio Cavaglieri]], and architectural consultant Arthur Rosenblatt devised a master plan for the library.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 538" /><ref>{{Cite news |last=Goldberger |first=Paul |date=May 25, 1984 |title=Inside and Out, Library Recaptures Its Splendor |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/25/nyregion/inside-and-out-library-recaptures-its-splendor.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> Before the master plan was implemented, the D. S. and R. H. Gottesman Foundation gave $1.25 million in December 1981 for the restoration of the main exhibition room,<ref name="nyt-1981-12-25" /> which was redesigned by Davis Brody and Cavaglieri.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 538" /> |

|||

Workers erected a temporary construction fence around the library's terraces in 1982.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Freedman |first=Samuel G. |date=August 21, 1982 |title=G.M. Stuns a Village by Layoffs |language=en-US |page=26 |work=The New York Times |url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1982/08/21/099110.pdf |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref name="Rosenblatt p. 3">{{harvnb|Rosenblatt|1984|ps=.|p=3}}</ref> As part of a greater renovation of Bryant Park, [[Laurie Olin]] and Davis Brody redesigned the terraces, while [[Hugh Hardy]] redesigned the kiosks within the terraces.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 538" /><ref>{{Cite news |last=Carmody |first=Deirdre |date=December 1, 1983 |title=Vast Rebuilding of Bryant Park Planned |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1983/12/01/nyregion/vast-rebuilding-of-bryant-park-planned.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> Several rooms were restored as part of the plan.<ref name="Rosenblatt p. 3" /> The first space to be renovated, the periodical room, was completed in 1983 with a $20 million gift from ''[[Reader's Digest]]'' editor [[DeWitt Wallace]].<ref name="nyt-1983-04-06">{{Cite news |last=Carmody |first=Deirdre |date=April 6, 1983 |title=Library Restores Periodical Room's Splendor |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1983/04/06/nyregion/library-restores-periodical-room-s-splendor.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> The exhibition room reopened in May 1984 and was renamed the Gottesman Exhibition Hall.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 539">{{harvnb|Stern|Fishman|Tilove|2006|ps=.|p=539}}</ref><ref name="Carmody 1984">{{Cite news |last=Carmody |first=Deirdre |date=May 25, 1984 |title=Exhibition Hall Opens With a Flourish |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/25/nyregion/exhibition-hall-opens-with-a-flourish.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> The Catalog Room was restored starting in 1983.<ref name="Postal p. 10">{{harvnb|ps=.|Postal|2017|p=10}}</ref><ref name="nyt-1983-07-01">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1983/07/01/nyregion/new-york-day-by-day-009129.html |title=New York Day by Day |last1=Johnston |first1=Laurie |last2=Anderson |first2=Susan Heller |date=June 1, 1983 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> Ten million catalog cards, many of which were tattered, were replaced with photocopies that had been created over six years at a cost of $3.3 million.<ref name="nyt-1983-07-01" /><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26439522/ |title=Computer Age Invades Library |agency=Associated Press |date=August 14, 1976 |work=The Post-Star |access-date = December 22, 2018 |location=Glens Falls, NY |page=24 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> In addition, room 80 was renovated into a lecture hall called the Celeste Bartos Forum in 1987.<ref name="nyt-1987-09-23">{{Cite news |last=Jones |first=Alex S. |date=September 23, 1987 |title=42d Street Library Opens 400-Seat Bartos Educational Forum |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/23/nyregion/42d-street-library-opens-400-seat-bartos-educational-forum.html |access-date=July 12, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref name="Stern (2006) pp. 539-540">{{harvnb|Stern|Fishman|Tilove|2006|ps=.|pp=539–540}}</ref> Offices were relocated to former storage rooms on the ground level.<ref name="DM p. 89" /> Other divisions were added to the Main Branch during the 1980s, such as the Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle in 1986,<ref name="NYPL-Pforzheimer">{{cite web |url=https://www.nypl.org/about/divisions/pforzheimer-collection-shelley-and-his-circle |title=About the Pforzheimer Collection |publisher=New York Public Library |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> and the Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs in 1987.<ref name="NYPL-Wallach">{{cite web |url=https://www.nypl.org/about/divisions/wallach-division |title=About the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs |publisher=New York Public Library |access-date = December 22, 2018}}</ref> The terraces on Fifth Avenue reopened in 1988 after they were restored.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 539" /> |

|||

*In an [[The Library (Seinfeld episode)|episode]] of ''[[Seinfeld]]'', [[Cosmo Kramer]] ([[Michael Richards]]) dates an NYPL librarian, [[Jerry Seinfeld]] is accosted by a library cop ([[Philip Baker Hall]]) for late fees, and [[George Costanza]] ([[Jason Alexander]]) encounters his high school gym teacher living homeless on the building's stairs. |

|||

[[File:New-York - Bryant Park.jpg|thumb|[[Bryant Park]], underneath which additional stacks were constructed in the late 1980s]] |

|||

*The NYPL is the setting for much of '"The Persistence of Memory," the eleventh part of Carl Sagan's ''[[Cosmos: A Personal Voyage|Cosmos]]'' TV series. |

|||

Meanwhile, the library was adding 150,000 volumes to its collections annually, which could not fit within the stacks of the existing building.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 539" /><ref name="Anderson 1987" /> In the late 1980s, the New York Public Library decided to expand the Main Branch's stacks to the west, underneath Bryant Park.<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /><ref name="Anderson 1987">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1987/10/27/nyregion/library-starts-road-to-84-mile-shelves-under-park.html |title=Library Starts Road to 84-Mile Shelves Under Park |last=Anderson |first=Susan Heller |date=October 27, 1987 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref> The project was originally estimated to cost $21.6 million and would be the largest expansion project in the Main Branch's history.<ref name="n26442406">{{cite news |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26442406/ |title=Library, Bryant Park branching out |last=White |first=Joyce |date=October 16, 1987 |work=New York Daily News |access-date = December 18, 2018 |page=155 |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> It was approved by the city's [[New York City Public Design Commission|Art Commission]] in January 1987,<ref>{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1987/01/13/nyregion/bryant-park-project-approved.html |title=Bryant Park Project Approved |date=January 13, 1987 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref> and construction on the stacks started in July 1988.<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /> The expansion required that Bryant Park be closed to the public and then excavated, but because the park had grown dilapidated over the years, the stack-expansion project was seen as an opportunity to rebuild the park.<ref name="n26442406" /> The library added more than {{convert|120,000|sqft|m2}} of storage space and {{Convert|84|mi|km}} of bookshelves under Bryant Park, doubling the length of the stacks in the Main Branch.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 539" /><ref name="Anderson 1987" /> The space could accommodate 3.2 million books and a half-million reels of microfilm.<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 539" /> The new stacks were connected to the Main Branch via a tunnel measuring {{cvt|62|ft}}<ref name="Stern (2006) p. 539" /> or {{Cvt|120|ft}} long.<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /> Once the underground facilities were completed, Bryant Park was completely rebuilt,<ref>{{cite news |title=Bryant Park to bloom again |date=December 28, 1980 |work=New York Daily News |pages=[https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26442164/ 645], [https://www.newspapers.com/clip/26442144/ 647] |via=Newspapers.com}}</ref> with {{Convert|2.5|or|6|ft|m}} of earth between the park surface and the storage facility's ceiling.<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /><ref name="Weber 1992">{{cite web |issn=0362-4331 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1992/04/22/nyregion/after-years-under-wraps-a-midtown-park-is-back.html |title=After Years Under Wraps, A Midtown Park Is Back |last=Weber |first=Bruce |date=April 22, 1992 |website=The New York Times |access-date = December 23, 2018}}</ref> The extension was opened in September 1991 at a cost of $24 million;<ref name="NYPL-Facts" /> however, it only included one of two planned levels of stacks.<ref name="NYTimes-BookTrain-2016" /> Bryant Park was reopened in mid-1992 after a three-year renovation.<ref name="Weber 1992" /> |

|||

===[[Novels]]=== |

|||

*Lynne Sharon Schwartz's ''The Writing on the Wall'' (2005), features a language researcher at NYPL who grapples with her past following the [[September 11, 2001 attacks]]. |

|||