Kalkum Castle

The Kalkum Castle is a moated castle in the same district in the north of Düsseldorf, about two kilometers northeast of Kaiserswerth and an extraordinary example of the neoclassical palace in the Rhineland . Together with the associated park , it has been a listed building as a whole since January 18, 1984 .

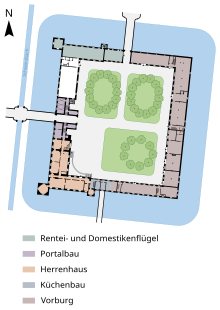

Originating from one of the oldest knight seats in the region, the ancestral seat of the knightly lords of Kalkum , the property came to the lords of Winkelhausen around the middle of the 15th century , who were to determine the fortunes of the complex for the next 300 years or so. In the 17th century, changed to a baroque style palace , the complex got its current external appearance mainly through a classicistic reconstruction between 1808 and 1814 based on designs by the Krefeld master builder Georg Peter Leydel . He connected the outer bailey and the manor house by adding intermediate structures to form a closed four-wing complex. At the same time, under the direction of the landscape architect Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe, a palace park in the English landscape style was laid out . In 1817 the main gate was enlarged by the architect Johann Peter Cremer . The interior of the palace was designed by the decorative painter Ludwig Pose .

Kalkum became known far beyond the borders of Prussia through the divorce war between the castle owner Count Edmund von Hatzfeldt and his wife Sophie , which lasted from 1846 to 1854 , when she was represented as a lawyer by Ferdinand Lassalle, who was only 20 at the time . Today a memorial in a tower-like pavilion on the eastern wall of the palace gardens commemorates him . After the Second World War , the buildings were initially used as refugee accommodation and then as a training center for home workers. After that, the facility was restored from 1954 to 1966 and converted for use as an archive . The classicist living and common rooms of the mansion were restored.

Today the castle is empty because the branch of the North Rhine-Westphalia State Archives , which had been located there for a long time , moved to the new building of the State Archives in Duisburg at the end of 2014 . The facility is still used for classical concerts and other cultural events. The approximately 19 hectare park is open to the public.

history

Beginnings and the Kalkum feud

According to the rhyming chronicle created by Eberhard von Gandersheim from 1216 to 1218, a royal court already existed in Kalkhem in 892 , which the later Emperor Arnolf of Carinthia donated to the Gandersheim monastery in that year : “I could still have a riken hof to Gandersem, de is gone Kalkhem ; unde sin bi deme Rine. ”Kalkum was first mentioned as Calechheim in 947, when Emperor Otto the Great confirmed this donation. The Gandersheim property, however, was not a predecessor of today's castle, but probably the part of Kalkum known today as Niederhof in Unterdorf . In 1176 , the lords of Kalkum were first mentioned in a document with the noble Willelmus de Calecheim , a ministerial of the Meer monastery . You were the owner of a knight's seat in Kalkum. Members of the family later called themselves von Calichem , Caylchem , Calgheim and von Calcum . The seat of the knights was a first permanent house in the part of Kalkum called Oberdorf , which up to now could not be dated or localized more precisely, but was probably at the site of the present-day castle. From the 14th century, the lords of Kalkum were in the service of the Bergisch counts and later dukes. Peter von Kalkum held the office of Bergisch Hofmeister in 1360 and was ducal Landdrost from 1361 to 1383 .

By the 14th century, the Kalkum knight's seat had developed into a castle-like complex, probably consisting of a manor house and an outer bailey separated from it by a moat . According to earlier tradition, this complex was besieged and destroyed by Cologne troops in 1405 , because members of the family of the Lords of Kalkum were in feud with the city of Cologne from the end of the 14th to the beginning of the 15th century , which is known as the Kalkum feud in Rhenish history received. However, contemporary chronicles only report the destruction of the house of Arnold von Kalkum ( heren Arnols huyss ) and not explicitly about the Kalkum castle. Recent research suggests that the house that burned down was not the Kalkum Castle, but the Remberg house south of Duisburg .

Kalkum under the von Winkelhausen family

The lords of Kalkum rebuilt their burnt knight seat after the feud was over. A map from around 1600 shows it as an ensemble of three houses connected by corridor-like structures, which were surrounded on all sides by a shared moat. However, the complex did not remain in the possession of the lords of Kalkum for long, because around the middle of the 15th century the male line of the Kalkum family died out, and the castle came as an inheritance to the von Winkelhausen family, their ancestral seat, the Haus Winkelhausen , a few kilometers north of Kalkum. When exactly this happened has not yet been clearly established. It is documented that Grete von Kalkum bequeathed her property in the parish of Kalkum to Hermann von Winkelhausen in 1443. The Kalkum House could also have been among them. It is documented that the castle at that time was owned by Winkelhausen in 1465, because that year Herrmann von Winkelhausen designated Kalkum as the widow's residence for his wife Agnes on October 27th . Also in the 17th century the facility was used several times to care for widowed members of the family. After the inheritance in the 15th century, the von Winkelhausen family moved their permanent residence to Kalkum. Around 1500 the owner was Johann von Winkelhausen. The system first came from him to his son Ludger and, in 1556, to his nephew of the same name. This Ludger von Winkelhausen was Jülich-Bergischer councilor, stable master and marshal as well as bailiff from Hückeswagen , Bornefeld and Mettmann . In 1553 his family was privileged by Emperor Ferdinand III. also been raised to the baron class.

Ludger had the old Gothic moated castle rebuilt and expanded into a representative baroque castle by 1663, partially using the old structure . The stately home on the southwest corner of the complex, known as the upper house , not only received large rectangular windows and a new roof, but also a square corner tower with a curved hood and architecture was added to its two wings, which abut at right angles . The main focus of the work was on enlarging the outer bailey building. Ludger had the old economic buildings completely laid down and then erected a new four-winged outer bailey that was more than twice the size of its predecessor. Together with the manor house, the castle now had its square floor plan, which has been preserved to this day, and was surrounded by a newly dug moat. A drawing by the Walloon painter Renier Roidkin from around 1720/1730 shows Kalkum Castle after the renovation and expansion work. A palace chapel to the north of the two-story mansion was part of the existing building stock at that time . A roof turret shown on the Roidkin drawing indicates this no longer preserved building . In addition, a stone foundation that was found at the corresponding location suggests an altar . At the northeast corner of the outer bailey was a polygonal corner tower with a double-curved baroque dome, which is no longer preserved today. A wooden bridge led across the southern moat to a square tower with a gate .

After Ludger von Winkelhausen's death in 1679, his son Philipp Wilhelm took over the inheritance. During his time as lord of the castle, Kalkum was almost constantly involved in acts of war due to its proximity to the strongly fortified Kaiserswerth. In the course of the Palatinate and the subsequent War of the Spanish Succession , the complex was badly affected. In 1688 soldiers of the Sun King Ludwig XIV occupied Kaiserswerth. The French minister of war Louvois asked Philipp Wilhelm to demolish his property by backfilling the moat and removing all of the defensive walls . When these demands were not met immediately, French troops occupied the facility and devastated it. Their stay on Kalkum did not last long, however, because the German imperial princes had come together to drive the French from the Lower Rhine. The French soldiers finally had to vacate the castle and flee from the advancing allied troops of Brandenburg, Münster and Holland, some of whom then moved into quarters in the castle themselves. The change of crew was accompanied by constant bombardment of the system, which caused considerable damage to the masonry and roofs. The billeting of the soldiers - only Lieutenant Colonel von Kalkstein from the Brandenburg regiment came with 40 horses and 200 foot soldiers - impaired the structure of the building. Despite the uncertainties, the von Winkelhausen family stayed at Kalkum Castle during this time. Kalkum also found himself involved in the fighting during the War of the Spanish Succession, in the course of which Kaiserswerth was again captured by French troops at the end of November 1701 and besieged and recaptured in 1702 by allied imperial troops of Holland and Prussia under the leadership of Elector Johann Wilhelm II . Again soldiers moved into quarters in the castle. This time the buildings were not damaged by acts of war, but gardens, fields and meadows were devastated by fortification work and could no longer be cultivated. In addition, the occupiers had removed or destroyed numerous equipment and furniture from the castle.

Transfer to the von Hatzfeldt family and new quarters

The von Winkelhausen family was raised to the rank of imperial count by Elector Johann Wilhelm in his capacity as imperial vicar on behalf of the emperor on October 2, 1711 . Philipp Wilhelm's son from his marriage to Anna Maria von Hompesch , Count Franz Carl, died in 1737. When his only son Karl Philipp died shortly afterwards in 1739, the Kalkum line of the Counts of Winkelhausen in the male line became extinct. Philipp Wilhelm's daughter Isabella Johanna Maria Anna, who married Edmund Florenz von Hatzfeldt- Wildenburg - Weisweiler on November 17, 1703, became sole heir to the property . Through her the castle came to her husband's family. But she not only inherited the castle, but also the associated debts of 77,000 Reichstalers . The family managed to re-establish a stable financial position through clever management. Initially, however, the von Hatzfeldts rarely stayed in Kalkum. The complex was only inhabited by a rentier and the tenant of the agricultural land belonging to the castle. A chief forester administered the extensive forest property. Because the manor house was mostly uninhabited, its structural condition deteriorated noticeably. This made it more difficult to billet soldiers again during the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War . It was used by French soldiers from 1741 to 1742 under Marshal Jean-Baptiste Desmarets . In the Seven Years' War it was initially French again who set up camp at Kalkum Castle by April 18, 1758. They were followed in June by Hanoverian troops under General von Wangen, who were relieved by soldiers from the allies, before a French regimental staff again confiscated the castle for their purposes in November. No exemption certificate , which the French Marshal Charles de Rohan , Prince of Soubise , had issued for the castle, was of any help against his billeting . He was simply ignored. The changing billeting ceased at the end of the Seven Years' War, but by then the building fabric had suffered greatly. From 1747 to 1755 major alterations were made to the farm buildings, including the expansion of the horse stables and the establishment of a saddle room. In 1778 the lord of the castle considered enlarging the house, but this plan was not carried out.

Conversion to a classicist castle

Only at the beginning of the 19th century was Kalkum Castle to be used as a permanent residence again. In 1806 Maria Anna von Kortenbach , the widow of the recently deceased Jülich Land Marshal Edmund Gottfried von Hatzfeldt (1740–1806), came to Kalkum to use the castle as a widow's residence. Her daughter-in-law Frederike Maria Hubertine von Hersell (1758–1833), who was widowed in 1799, and her grandson Count Edmund von Hatzfeldt, born in 1798, came with Maria Anna . However, because they found the castle uninhabitable, they temporarily moved to Kinzweiler , before moving to the tenant apartment at Kalkum Castle from autumn. They spent the subsequent winter of 1806/07 in the Hof von Holland in Düsseldorf and in the spring they moved into quarters again in Kalkum Castle, this time in a small room in the rent master's apartment. The widow quickly realized that extensive construction work would be required to be able to use Kalkum as a residence in the future. In July 1805, her deceased husband had turned down an offer from a Swedish colonel who was looking for a suitable country estate to lease Kalkum Castle and restore it to a habitable state. Maria Anna hired the Krefeld master builder Georg Peter Leydel to convert the run-down baroque palace into a spacious residence in the classicism style. Leydel left almost all of the buildings inside unchanged, but made the exterior of the complex more symmetrical . So he abolished the separation of mansion and outer bailey by filling in the dividing moat and closing the gaps with intermediate structures. In addition, the western part of the outer bailey was demolished and replaced by a copy of the baroque manor house. The relocation of the main access from the north to the west side completed Leydel's conversion plans.

Repairs to the outer bailey in 1808 marked the start of the following six-year construction work on the castle, which Leydel initially calculated to only take four years. From November 1809, the manor house underwent only a relatively minor external renovation: ceilings and roofs as well as the wall crown were repaired and the building on the western front was extended from six to eight window axes. A newly built, low central building with a portal connected the manor house with its recently built counterpart on the northwest corner of the complex. Like the original, this counterpart of the manor house had two wings; the western wing was completely redesigned after the outer bailey wing was demolished; the northern wing , later called Rentei and Domestiken wing , consisted of the former Halfenhaus , which in 1812/1813 was increased by one storey on three floors and thus to the height of the west wing. As early as 1811, the north-western corner tower - at the same time as the tower at the north entrance - was laid down and rebuilt. With the completion of the central portal building in the same year, Kalkum Castle had a symmetrically designed, representative front. The western part of the previous wing of the outer bailey in the south was torn down in September 1810 and the gap there was closed by the so-called kitchen building, a two-story intermediate building with three window axes. Its height was initially determined by the stable adjoining it to the east. After all the work on the outer bailey was finished , it was painted a light ocher paint, while the white exterior color of the rest of the castle was not changed. From 1810, craftsmen were involved in redesigning the interior of the mansion in the strict Empire style . From this initial furnishing of the living rooms with elaborate stucco work , valuable wallpaper and magnificent wall paintings , hardly anything has been preserved through subsequent redesigns. Engelbert Selb from Krefeld was responsible for the stucco work. The wallpaper was supplied by the upholsterer J. G. Lentzen from Aachen. During the work he carried out in November 1811, not only paper wallpapers were used, but also sometimes very expensive fabrics, for example in the so-called tower room , which has a wall covering made of Chinese silk . The wall paintings were made by the Düsseldorf decorative painter Ludwig Pose , who later also worked in Jägerhof Palace and Rheinstein Castle . In April 1813, the mansion was so far completed that the von Hatzfeldt family could move into it. Only a few months later, in early 1814, Russian billeting was in the castle for a few months after it had driven away the French soldiers previously stationed there.

Meanwhile there had been a quarrel between the countess and her builder, and the two went their separate ways. From 1815 onwards, Leydel no longer appeared in the count's building bills, but the palace renovation was still unfinished at that time. To make matters worse, Leydel never submitted plans for the renovation, so that Maria Anna von Kortenbach had to have new designs made for the further construction. It was taken into account that the previous design was too simple and not representative enough for the lady of the castle. The first smaller renovation took place in 1817, when the west portal was supplemented by a risalit according to plans by Johann Peter Cremer , who shortly afterwards designed the Aachen City Theater and was a close collaborator of Adolph von Vagedes . In 1819 the lady of the castle had August Reinking , who had previously worked at Oberhausen Castle , work out a proposal for the redesign of the simple Leydel central building in the west wing into a stately corps de logis . He envisaged the extension of the building and its deepening on the inner courtyard side. The flat roof was to be crowned by a dome and hidden behind a wide balustrade . Reinking also planned to demolish the third floor of the two corner towers and replace it with a low mezzanine floor in order to deprive the towers of their dominance on the west facade. However, Reinking's unexpected death just months after submitting the drafts thwarted the implementation of the plan. Countess Maria Anna was forced to look for architects again and chose Friedrich Weinbrenner from Karlsruhe as his successor. Weinbrenner was staying in Düsseldorf at the time because he was working on plans for the new building of the Düsseldorf theater. In 1820 he also presented the countess with a design for the redesign of the western palace facade; But since Weinbrenner's plans to build the Düsseldorf theater failed, he went back to his hometown, and so his plan for Kalkum was not carried out either.

Another architect had been working on the palace since 1818: Anton Schnitzler , a Vagedes student. According to his plans, the kitchen in the south wing was extensively changed in 1821. He added a second, low upper floor to the building in order to match the height of the mansion adjoining it to the west. From then on, the new floor served as staff accommodation. The design of the outer facade was also changed with a flat projecting central projection and new windows. Schnitzler resorted to a trick: In order to adapt the facade of the three kitchen floors to the two-story mansion, the lower row of high arched windows not only illuminated the ground floor, but also the lower mezzanine floor above. In the course of this renovation work, the south entrance was probably relocated from the flanking square tower to the kitchen wing. Around the same time, around 1820, houses were built for the castle servants on the southern edge of the castle park. Up until the 1820s, the northern west wing of the palace and the upper floor of the renting and domestics wing were only partially completed. Now their interior work has been started. The reason for this was the lack of space that had arisen due to the birth of several children in the Hatzfeldt family. On August 10, 1822, Maria Anna's grandson Edmund married the 17-year-old Sophie von Hatzfeldt-Schönstein, who was related to him, in the chapel of Allner Palace . Two days after the marriage, the family organized a pompous wedding for the couple at Kalkum Castle, where the two newlyweds then lived. The billiard room was completely overhauled especially for this party . In the days after the celebration, numerous window panes in the castle had to be replaced because they broke during the evening fireworks at the event.

Until 1833 there was a slender square tower with a double-curved baroque hood, which served as a pigeon tower , at the northeast corner . That year it was demolished and the gap that arose was closed by a wall. Countess Maria Anna von Kortenbach died in September of the same year. Her grandson Edmund succeeded her as the castle owner. In 1836, he hired the Essen city master builder Heinrich Theodor Freyse as the leading architect to redesign the rooms in the manor house. Under him, who had previously been responsible for the new construction of Heltorf Castle , the so-called state rooms were created from 1837 onwards . These living and social rooms were given an elaborate late-classicist décor based on Freyse's plans by 1841. With Ludwig Pose and the upholsterer Lentzen, two of the experts who had already been responsible for part of the interior decoration under Leydel were used. The stucco work was carried out by the Cologne master plasterer Lenhardt and his journeyman Moosbrugger. The sculptural jewelry came from the workshop of the Düsseldorf sculptor Dietrich Mein (h) ardus . In 1841/42 the work came to an end when the west wing of the castle and the other fronts of the manor house and the pension wing were given a new plastering , which was painted light pink according to Freyse's proposal.

At the same time as the renovation work from 1808, Countess Maria Anna had a new castle park laid out in the English landscape style. The plans for this were provided by Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe , who coordinated them with Georg Peter Leydel on his building project. It was probably even Leydel on whose recommendation Weyhe received the contract. To the west of the palace there was already a small park from the Baroque period, which was to be redesigned and enlarged. In order to be able to carry out the expansion, plots of land west of the castle were acquired by swap. On November 18, 1807 Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe visited Kalkum for the first time to get an impression of the location and to carry out a survey. As early as January 26th, he delivered his plans for the redesign and redesign of the Kalkum Park to the lady of the castle, the originals of which have not survived today. The Düsseldorf court gardener managed the gardening work in Kalkum until 1819 (in that year the complex was essentially completed), whereby the original plan was repeatedly supplemented with new elements in the course of implementation, so that the work continued until 1825. Under Weyhe's direction, not only was a new landscape garden designed, but also kitchen gardens as well as a park pond and a riding arena north of the castle. Together with Leydel, on June 12, 1809, he set the final boundaries of the English garden and from then until 1819 went to Kalkum once a month to assess the progress of the work. By 1818, 7572 trees and bushes had been delivered to Kalkum for the design of the gardens and parks. Weyhe had the Schwarzbach canalized, which still feeds the castle graves today , so that it flows in a straight line from south to north on the west side. He used the excavation of the pond north of the castle square to raise a hill on the northern edge of the landscaped garden between November 1812 and May 1813, on which a small temple in the tradition of the chinoiserie was built by 1818 . In the following year, a shooting range was set up in the south-western area of the park and the nearby ice cellar was renovated at the same time . To the south of the palace building, at the level of the mansion wing in front of the water supply, there was an older formal garden , traditionally designed with a cross , which Weyhe rededicated as a kitchen garden . The part of the trench adjacent to this garden was filled in in 1825 and the area gained as a result was added to the south garden. A luxurious greenhouse called the flower house was built on this area in 1835 on the south side of the south-west tower according to Weyhe's plans . In addition, an orangery over 20 meters long was built in the eastern area, leaning against the southern outer wall, and parallel to it in the summer of 1838 the so-called pineapple house .

After the work on the palace buildings was finished and the gardens were completed, the palace was only rarely used as a residence by the Hatzfeldt family. She stayed mostly in Düsseldorf. The agricultural operation as well as the pig and cattle sheds were given up as early as 1840. Kalkum served almost exclusively as the seat of Hatzfeldt's main administration, which was under the direction of a rent master. Nevertheless, the complex moved into the public eye again during the 19th century when Countess Sophie von Hatzfeldt separated from her husband Edmund in 1846. The marriage of the two was concluded in 1822 for purely family policy reasons and was not a happy relationship. The matter degenerated into a veritable war of divorce and was waged with bitter severity on both sides. The countess was represented by the young Ferdinand Lassalle as a lawyer. The divorce process was brought before six courts before the parties agreed in a settlement in 1854 that Sophie von Hatzfeldt would get her allode back and thus become financially independent.

Changing uses and decline

Under Edmund's and Sophie's son Alfred and his wife Gabriele von Dietrichstein-Proskau-Leslie, some minor construction work was carried out in the castle in the second half of the 19th century, for example the installation of several porcelain ovens in 1867 . Shortly thereafter, around 1870, there were changes to the interior decoration, as a result of which the classicist furnishings were lost in all living rooms with the exception of the music hall . Nevertheless, Prince Alfred and his wife spent little time on Kalkum. Alfred, who was elevated to the Prussian prince's status on May 10, 1870 , was inherited by his nephew Paul Hermann von Hatzfeldt in 1911 . Under him, the castle was finally given up as a residence and in 1912 the Hatzfeldtsche Rentei relocated to Crottorf , the main residence of Paul Hermann and his wife Maria von Stumm . The mansion was then rented out, the castle owners only reserved a few rooms for temporary stays in Kalkum. The tenants included the von Spee , von Stumm and von Benningsen families . Since, in addition to the rentmaster, some families in the service of the prince kept their apartments in the castle, the building and park were still well cared for. That did not change when in 1915, during the First World War, a recruit depot was set up in the castle and after the end of the war, first a soldiers' council and then Spartacists moved into quarters in the complex. The painter Richard Gessner lived there from 1938 to 1945 . He recorded his impressions of the complex in numerous paintings that can be seen today in the Düsseldorf City Museum, among other places .

The structural condition of the facility, which had been good up to then, changed with the Second World War. To secure the nearby Düsseldorf airport , a flak tower was built in the courtyard of the palace . Air defense crews and officers moved into the castle building, while anti-aircraft helpers were housed in a barrack built especially for them on the area of the riding arena in the northern park area. Kalkum Castle did not receive any direct bomb hits during the war, but frequent impacts in the area caused massive structural problems in the roof beams . The improper use as soldiers' quarters and as storage space for Düsseldorf companies was also detrimental to the building fabric. In addition, the fragmentation effect of the flak bullets caused severe damage to the trees in the castle park, which gradually overran the lack of labor. After the end of the war, English occupation troops confiscated the facility and converted the mansion into an officers' mess. For reasons of hygiene, they removed many of the valuable wallpaper and burned them. In 1946 the British cleared the castle again.

Sale to North Rhine-Westphalia and conversion to an archive

After the British soldiers moved out, the then owner Maria von Hatzfeldt offered the castle, including the park and surrounding agricultural areas, to the newly founded state of North Rhine-Westphalia for 750,000 Reichsmarks . The state accepted this offer. The corresponding sales contract, in which the lady of the castle reserved some rooms in the pension wing for herself and her employees until 1951, is dated November 15, 1946. The state government confirmed this on February 3, 1947 in order to set up a craft training and work center for war refugees in the castle buildings, because at the time of the sale the facility served as accommodation for over 100 displaced persons at times. The model for the project was the association for arts and home work in the Rhineland, which had been around for around ten years and pursued the goal of training refugees and severely disabled people for home-based arts and crafts. Kalkum Castle was repaired for this purpose in 1948/1949, whereby the focus was not on monument protection , but on making it usable for living and working purposes. The work, estimated at 20,000 Reichsmarks, also included breaking out new windows. The refugee aid plan ultimately fell victim to the currency reform , and activities related to it were discontinued on June 30, 1950. Now those responsible were looking for a new use. Among other things, the use as a retirement home for displaced persons, household school, police station and state fire brigade school was discussed. This was just as never realized as the plans to set up an administrative office or conference center in the castle or to use the building as a hotel. During these numerous considerations and suggestions, the neglected facility deteriorated more and more. In the end, the mansion even had to be cleared because the roof structure was completely rotten due to moisture and the half-timbered walls were no longer strong enough. In 1952, an emergency situation gave rise to a new use perspective: notary files from the main state archive , which had been relocated to Schloss Linnep and Schloss Gracht during the war, were to be returned to Düsseldorf and merged. The space required for this was provided by the north and east wings of the Kalkum outer bailey, in which a provisional auxiliary store was set up. From this makeshift solution, the plan arose to use Kalkum Castle as a branch archive of the main state archive in the long term.

In order to meet the requirements of an archive, extensive renovation and restoration work was necessary on the buildings, which began in April 1954 under the auspices of the Düsseldorf State Building Authority . In a first phase, up to March 1955, the north and east wings were redesigned into a newly furnished warehouse, garages were set up and a heating system was installed. By August 1956, in a second phase, the southern wing of the outer bailey was expanded to three apartments and a special archive, for which the corresponding building section had to be completely gutted. In addition, a police apartment was expanded in the north wing. Steel structures inside gave the walls, which were no longer stable, support. The castle was also given a new roof, and the window openings that had only been broken out in the late 1940s were closed again. At the same time, the castle moat was desludged in 1954, during which not only the foundations of the former pigeon tower, but also large quantities of live ammunition from both world wars were found. Not only the structure but also the sewer system had to be renewed; During excavation work in the inner courtyard of the palace at the end of November 1954, remains of the foundation made of field fire bricks and trachyte blocks were found that had been left over from the demolition work at the beginning of the 19th century. It was the foundation walls of two late medieval building phases, which archaeologically prove that the mansion of the Kalkum complex had always stood on today's southwest corner. However, these remains of the foundation remained accidental finds; systematic excavations were not possible during the entire restoration work.

From October 1956 to mid-1960, the restoration of the manor house and the adjoining kitchen took place in a third construction phase , so that the administration rooms of the archive could then be accommodated on the upper floor. On the ground floor of the manor house, unexpectedly many remains of the former classicist room decorations were found, so that it was decided to restore the furnishings of the magnificent living rooms. The wall and ceiling paintings were reconstructed from the remains of the original wallpaper and the remaining painting. In a fourth construction phase, which lasted from November 1958 to December 1962, the rentier and domestics wing was expanded and converted in order to be able to install a five-story compact magazine system there. The three-storey north front of the building was aligned with its two-storey west front. Finally, the entire western front, including the facades of the manor house and the Rentei and Domestiken wing, was given a new pink-colored lime- casein paint ( caput mortuum in lime and oil). From 1962 on, the fifth and final construction phase included the design of the remaining external facades and the restoration of the palace gardens by Franz Josef Greub. The work ended in autumn 1967 when the southern trench , dredged again the year before and provided with a modern concrete bridge , was filled with water. The total costs of the 13-year restoration and renovation work came to a total of 4,675,000 DM . This was not yet completed when the branch archive of the main state archive started operations in 1962 with around 3400 m² of floor space and 25 kilometers of shelves.

Kalkum Castle to this day

After the extensive work in the 1950s and 1960s, the palace only saw comparatively small maintenance measures. This included the renewal of the exterior paintwork in the years from 1980 to 1981 and in 1995 the new excavation of a small park pond north of the Rentei and Domestiken wing that had been there before. In addition to the Rhineland department of the State Archives, Kalkum Castle has also housed part of Vester's Archives, Institute for the History of Pharmacy , a collection founded in 1937 by the pharmacist Helmut Vester. The part kept in Kalkum comprised a specialist library on the subject of pharmacy as well as pictures and maps on pharmacies and their history. There were also around 400 sight glasses filled with raw drugs. In 1993, Vester's archive moved to the Pharmaceutical History Museum at the University of Basel in Switzerland .

The elaborately reconstructed classicist lounges in the manor house are now used by the North Rhine-Westphalian Ministry of Culture for occasional receptions. The necessary supply rooms are located in the neighboring kitchen . Sometimes art exhibitions are held there and one of the halls can be used for meeting purposes. In the mid-2000s, a citizens' initiative campaigned to make another area of the palace accessible to the public: Its members wanted to redesign the orangery in the southeastern area of the palace park, which was then only used as a storage room, for cultural purposes and offer young artists an event forum there. However, the plan did not materialize.

The archive, which was housed in the castle for a long time, moved to the new location of the State Archive in Duisburg at the end of 2014 . The move had become necessary to deal with space and capacity problems in the main state archive. At the same time, synergies should be developed with the amalgamation of the previous Landesarchiv branches .

The state of North Rhine-Westphalia also planned to sell the property for a single-digit million amount, while ensuring that at least the Kalkum Palace Park remains accessible to the public. In January 2019 it became known that a preferred investor from Kalkum Castle, with the assistance of the architect David Chipperfield , wants to establish an academy for music and art.

The castle was sold in March of the same year to the project developer Peter Thunissen, who wanted to turn it into the music academy with the help of Chipperfield. To finance the redevelopment, he planned to convert the arable land west of the castle park into a residential area. However, after protests from citizens, these plans had to be abandoned. As of March 2020, the future of the project is still open.

description

The outer

Kalkum Castle is a closed four-wing complex made of brick masonry with square corner towers on the northwest and southwest corners. Its wings enclose an almost square inner courtyard and are surrounded on all sides by a moat. The classicist palace, the core of which dates back to the baroque era , stands in the middle of an extensive park . The manor house is located on the southwest corner , the two wings of which meet at right angles. The two wings only take up part of the west and south wings. The other tracts of the castle were formerly occupied by the outer bailey and buildings for the estate administration. Brick was used as building material for the masonry as well as trachyte , Ettringer tuff and Ratinger limestone for the walls of windows and doors.

Farm yard

The farmyard, also known as the outer bailey, made of exposed brickwork, used to occupy the eastern part of the north and south wings as well as the entire east wing of the complex. On the ground floor there were cattle, sheep, wild animals and horse stables as well as the stately horse stable, tack room, coachman's room and cleaning room. After the abandonment of agriculture, some stables were converted into a carriage shed and riding hall as well as a wood store. On the upper floors were the accommodations for horse and cattle men, stable staff and other servants such as the head forester, whose apartment was furnished in 1807. They were converted into apartments in the 1960s. There was also a large grain barn in the eastern wing of the bailey. At the southeast corner of the building there is a small bay window on the upper floor , which can already be seen in the Roidkin drawing from the 18th century and is therefore part of the baroque complex. In the past it was probably higher than the roof and served as a lookout. The southern and eastern exterior is the eaves and base cornice with a simple tooth frieze decorated, which is found to some extent on the courtyard side facades. It used to be used on all sides of the farm yard.

Western part

The western part of the castle consists in the south-western area of the manor house with corner tower, its structural counterpart on the northwest corner of the complex and a central building that connects the two parts and at the same time accommodates the main portal. Because the residential and administrative rooms of the castle were located in this area, the more than 100 meter long western section is particularly representative and forms the front side. This is expressed, for example, in the fact that it is plastered and painted pink and is also higher than the commercial buildings.

The northern part of the west wing was occupied on the first floor by storage space, storage and ancillary rooms before it was rededicated as an archive room. On the upper floor there were stately living rooms, bedrooms and guest rooms. Outwardly, this part of the castle resembles the west wing of the manor house. The western part of the north wing is called Rentei- und Domestikenflügel or, for short, just Renteiflügel . Its ground floor is the former Halfmannshaus , while the upper floor, which was added later, used to house the rooms of the rentier and the renter's apartment. Like the north part of the west wing, the building has a pan- roofed hip roof . Today the Renteiflügel, together with the north west wing, houses a file magazine of the State Archives. At its eastern end there is a slender, square two-story tower, closed off by a hipped roof. It has an almost identical counterpart at the east end of the manor house. The outer facades of the two wings are divided into eight axes by windows, with four of the eight ground floor windows each having a segmental arch roof . This emphasis on the axis is repeated in the attic with small hatches . The windows of the mansion are - like almost all the windows of the west - with gray shutters provided. The segmental arches can be found above the ground floor windows of the two three-story corner towers, while the openings above on the first floor are crowned by triangular gables. Both towers have curved domes that are closed off by a lantern surrounded by a gallery . The Kalkums tower domes are thus somewhat similar to those of Clemensruhe Castle in Bonn-Poppelsdorf . The manor house has two courtyard-side entrances, both of which have their own small outside staircase . These were connected to each other by a common platform in 1824. Next to the entrance in the west wing, a bronze plaque commemorates the “red countess” Sophie von Hatzfeldt.

The middle of the western front is occupied by an intermediate building with the main portal of the castle. In contrast to the windows of the other parts of the castle, the building on the ground floor has round arched windows without shop, surrounded by blind arcades . Although it is also two-story, it is lower than the other parts of the western part due to its flat hipped roof. The lantern motif of the corner towers is repeated on the roof by a small turret that was erected there in 1967. It is modeled on a predecessor that was destroyed by lightning and is crowned by a trumpet angel from the workshop of Joseph Jaekel . The wide access avenue, christened “Kalkumer Schloßallee” on September 18, 1931, runs in a straight line for a stretch of a little more than a kilometer towards this portal building . Shortly before the three-arched bridge over the moat, the driveway crosses the Schwarzbach over a small plastered brick bridge from 1809, which is flanked by two statues of reclining lions. They were made in 1652 by the master sculptor Johann from Kaiserswerth. The round-arched west gate, also known as the English Gate , is located in a central projectile built according to plans by Johann Peter Cremer with a joint cut and a flat triangular gable. It is flanked by dorising columns . A richly decorated relief with the coat of arms of the von Hatzfeld-Wildenburg family can be found above the archway . It shows the Hatzfeld coat of arms (black wall anchor in gold) in fields 1 and 4, and the Wildenburg coat of arms (three red roses in silver) in fields 2 and 3. The relief was created in 1854 by the Düsseldorf sculptor Dietrich Mein (h) ardus , who also designed the western entrance door of the manor house, richly decorated with carvings .

North gate, kitchen and inner courtyard

Until the classicist renovation at the beginning of the 19th century, the main entrance to the castle was in the north of the area. Accordingly, the castle gate in the middle of the north wing was designed more elaborately than the rest of the north wing. A four-arched bridge leads to it, the first three arches of which are made of trachyte blocks, while the last is made of bricks and documents that the gate once had a drawbridge . Wall anchors in the form of the year 1775 bear witness to the construction of the bridge in that year, which at the time replaced a wooden predecessor. The roles of the former drawbridge are still preserved in the semicircular archway, and the cover for the bridge is still clearly visible. Furthermore, two loopholes for hook rifles on the sides of the gate, framed by bosses made of Ratinger limestone, testify to its former strength. In the keystone of the archway is the coat of arms of the Winkelhausen family, framed by auricle and scrollwork and crowned by a count's crown . In the past it was probably colored. Among them is the only partially preserved year 1663, which thus heralds the year of construction of this piano.

The former gap between the south wing of the manor house and the south wing of the farm yard has been closed by the so-called kitchen wing (also known as the kitchen wing ). The name of the three-axis intermediate building shows that a kitchen has always been located there. Its three floors - the two upper floors are much lower than the ground floor - are of a shallow pitched roof completed. On the ground floor of the kitchen there is a side door, to which a modern concrete bridge now leads. In the past, the southern moat was spanned by a wooden bridge, which led to the neighboring, slim square tower and the gate there. Its foundations were found during repair work in 1948.

The courtyard-facing facades of the palace are all kept very simple and convey more the impression of a manor than that of a princely residence. The only special feature of the inner courtyard are three linden rings that take up three quarters of the courtyard area. The fourth area facing the manor house is designed as a paved courtyard. The trees were planted in 1825 according to Weyhe's plans .

Today's interiors

Kalkum Castle offers a total of 6500 square meters of usable space. The main entrance on the courtyard side with its walls made of Ratinger marble leads the visitor into the vestibule in the west wing of the manor house. Called the Marble Hall because of its black and white marble flooring , this room is the first in a series of living and state rooms , which are now also known as state rooms . This sequence of rooms, consisting of the marble hall , brown room , green room , billiard room and music room as well as the former dining room and library, was - with the exception of the former dining room - restored from 1956 to 1960 with its late classicist furnishings and then furnished with historical furniture and matching chandeliers . The rooms present themselves today with the restored or reconstructed wall and ceiling paintings, splendidly designed stucco work and precious parquet floors with inlays . Only two mirrors and two candlesticks (one of them in the billiard room ) remain in the castle from the original 19th century furnishings .

The ceiling painting of the marble hall is still original and comes from Ludwig Pose . In six fields it shows hunting and autumn motifs in muted colors. In the middle of the ceiling there is a large stucco rosette , which, in addition to elaborate friezes, supraports and a lunette above the marble fireplace, is part of the rich stucco decoration of the room. It was made by Lenhard and Moosbrugger. The fireplace has on both sides of its mouth pilasters with bräunierten brass - capitals . In contrast to the ceiling, the decoration of the walls consists only of empty fields, because there was no evidence of the original decoration for a reconstruction.

The Green Room , whose name comes from the color of its walls, can be reached from the Marble Hall . Like the neighboring brown room , it has a large stucco ceiling rose as the dominant ceiling element. What it has in common with the brown room and the billiard room is the elaborate design of the frieze, which is a combination of stucco work and wall painting. In the Green Room , the painted frieze elements show ears of corn and tendrils, while in the Brown Room they consist of pilaster capitals and flat arches. The paintings there could be reconstructed particularly splendidly because the painting was best preserved in this room. The billiard room can be reached through a door in the north wall of the brown room . There the painted elements of the wall frieze consist of depictions of griffins . In addition, this room has a lush ceiling decoration in the form of squares painted transversely to the longitudinal direction as a frieze and a painted, rectangular cartridge instead of a stucco rosette in the middle of the ceiling, which repeats the motifs of the wall frieze.

The south wing of the manor house is occupied by two large three-axis halls on the ground floor. The eastern one was in the 1950s without any findings of original furnishings, so that it was repaired in simple forms and can now be used as a conference room. Only its stucco rosette comes from earlier times (around 1870). In contrast, the western hall was almost completely restored to its old splendor from 1836 to 1841. However, its original ceiling paintings have been lost. It is called the music hall after the motifs in the wall panels depicting lyres . Above the marble fireplace on the long side opposite the windows there is a wall mirror framed by ornate stucco ornaments . A stuccoed ceiling frieze and surrounding arabesques as wall paintings complete the lavish furnishings of this room, the highlight of which is the floor with a flooring made of precious wood with inlaid mother-of-pearl . Here, too, Ludwig Pose was responsible for the decorative paintings, while Lenhard and Moosbrugger created the stucco. The library on the ground floor of the south-west tower can be reached through a wallpaper door in the western wall of the music hall . The originally square room was redesigned to form an octagon with walls drawn in over a corner . Glass shelving cabinets, which were installed there in 1854, stand on three of the four drawn-in walls. The ceiling painting of the room imitates a coffered ceiling , while the inlaid floor is characterized by a star motif.

The upper floor of the manor house - the former residential floor of the building - is now home to modern administrative offices, a library, a user room and the restoration workshops of the State Archives, which moved there in July 1958. With the exception of some stucco work by the Krefeld plasterer Eugen Selb, the original furnishings from the first half of the 19th century are no longer preserved. The only room that still dates from the Hatzfeld era is the so-called tower room . This is probably the bedroom of Countess Maria Anna in the southwest corner tower, which was designed in Empire style according to plans by Leydel .

Castle Park

Weyhe's new installation

Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe's design for the Kalkum Palace Park dates back to 1808. He envisaged a landscape garden in the English style as the central element , which had the typical components of this park form: visual axes, curved paths, groups of trees and solitary trees. The old castle mill from the 18th century on the southern edge of the park was included in the design. Weyhe also included the existing gardens on the west and south sides of the palace in his plan. The south garden can already be seen on the Roidkin drawing of the 18th century and is connected to the castle buildings by a wooden bridge. The strictly symmetrical garden followed baroque models and was divided into four equally sized squares by two paths crossing at right angles in the middle. At the intersection there was a roundabout planted with trees , the paths were bordered by hedges. Weyhe converted it into a kitchen garden . To the east of the castle, across the street, he had a large, geometrically structured orchard planted, for which apricot , cherry, apple and pear trees were purchased. They stood along paths that ran in a star shape towards a central roundabout. In the vegetable garden to the south there were fruit trees as well as sweet chestnuts and chestnuts. Weyhe created two rectangular compartments on the north side of the castle . The eastern one was supposed to accommodate a riding arena as a formal garden element, but this was only realized as a rectangular lawn. The western compartment consisted of a tree-lined, elongated pond with a small island, which is also called the English pond . It was bordered by a ribbon of lawn and a path running around it.

The existing small garden on the west side of the complex was enlarged considerably and the western central axis of the castle was extended through the castle avenue to Kaiserswerth. Weyhe bought a large number of different types of trees and shrubbery to transform it into an English landscape garden, including weeping ash , weeping willow , red fir , acacia , white pine , sweet chestnut , Canadian poplar , Dutch elm and red cedar. This area of the palace park also included a bowling alley set up in 1812, which can be seen on the Pesch map as a cross-shaped construction in the southern part of the park, a shooting range that consisted of a long rampart with a small hill at the end, and an ice cellar that already existed in 1809 on the southern part Park edge. A small temple with a hexagonal floor plan, which was surrounded by eight columns and had an eight-column tower, was built on a hill created by the castle pond excavation.

With his park design, Weyhe created spatially and functionally separate garden spaces, which communicated with the neighboring castle wings and whose size and design were determined by their architecture. Each of the garden rooms was designed differently and served a different purpose. While the landscape garden and the northern compartments were devoted to pastime, sport and fun, the south and east gardens served practical purposes as kitchen gardens, whereby aesthetic and practical concerns were mixed there, in that the orchards and vegetable gardens also had decorative elements to a certain extent .

The park today

From the palace park laid out by Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe , the basic structures of the semicircular English landscape garden on the west side, the northern compartments and the basic layout of the southern kitchen garden have been preserved. In the park, the terrain of which rises and falls in wavy lines, there are mostly indigenous trees and only a few exotic ones. For example, the Schlossallee leading to the west portal is lined with linden trees. From this access road in the central axis, two smaller, curved paths branch off, which lead around the landscape park , which is delimited to the outside by hedges and woody plantings , until they meet the canalized Schwarzbach at the southwest and northwest corner of the castle and this via smaller ones Cross bridges. The Schwarzbach feeds the moat of the castle and the northern castle pond. Coming from Wülfrath , it enters the castle park in the south, crosses it by flowing a large stretch parallel to the western castle moat - separated from it only by a dam with a narrow path - to flow north of the castle park at Wittlaer into the Rhine . On the southern edge of the park there is the ice cellar , which has been guaranteed for the beginning of the 19th century and is still accessible. Nearby, in the area of the south-western park meadow, there is a small hill with masonry. These are the remains of the shooting range established in 1819. On the opposite northern edge of the park there is still the artificially piled-up Temple Mount , the Chinese wooden temple of which is no longer preserved.

At the edge of the southern moat there is a small orangery on the eastern perimeter wall , which replaced the large orangery built under Weyhe. It was completely overhauled in 1965/66. A little south of it, the former garden pavilion, also known as the summer house and tea house , leans against the east wall from the inside. The small, tower-like plastered building, like the castle, is painted pink and is closed off by a baroque tail hood with a lantern. The exact time of its creation is unknown; it may go back to plans by Georg Peter Leydel . What is certain is that it was not built in connection with Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe's parking plans, but already existed at that time. During the major renovations in the first half of the 19th century, work was carried out in the pavilion several times. For example, his painting comes from Ludwig Pose, who was also responsible for the wall and ceiling paintings in the manor house. The garden house was converted into a memorial for Ferdinand Lassalle in 1975 on the occasion of Ferdinand Lassalle's 150th birthday . The interior of the building is designed as a cenotaph . A block of green Italian marble has the form of a sarcophagus , over it is on a marble console the bust Lassalle. On the north outer wall of the pavilion hang in two flat niches panels made of the same marble with a saying by Ferdinand Lassalle and information about his life and work.

literature

- Walter Bader (Ed.): Kalkum Castle . DuMont, Cologne 1968.

- Georg Dehio , Claudia Euskirchen (edit.): Handbook of German Art Monuments . North Rhine-Westphalia . Volume 1: Rhineland. Deutscher Kunstverlag , Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-422-03093-X , pp. 332–333.

- Günther Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to its building history. In: Düsseldorfer Jahrbuch . No. 47, 1955, ISSN 0342-0019 , pp. 199-234.

- Ludger Fischer : The most beautiful palaces and castles on the Lower Rhine. Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2004, ISBN 3-8313-1326-1 , pp. 44-45.

- Robert Janke, Harald Herzog: Castles and palaces in the Rhineland . Greven, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-7743-0368-1 , pp. 182-185.

- Benedict Mauer: Kalkum Castle . In: Kai Niederhöfer (Red.): Burgen Aufruhr. On the way to 100 castles, palaces and mansions in the Ruhr region . Klartext, Essen 2010, ISBN 978-3-8375-0234-3 , pp. 112-114.

- Karl Emerich Krämer : From Brühl to Kranenburg. Castles, palaces, gates and towers that can be visited . Mercator, Duisburg 1979, ISBN 3-87463-074-9 , pp. 90-93.

- Karl Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum (= Rheinisches Kunststätten , issue 178). 2nd edition, Neusser Druckerei und Verlag, Neuss 1995, ISBN 3-88094-800-3 , pp. 4–25.

- Rolf Watty: Kalkum Castle. A guided tour through the outer palace complex as part of a study trip on May 15, 2004 . In: Heiligenhauser Geschichtsverein (ed.): Cis Hilinciweg. Brochure of the Heiligenhauser Geschichtsverein e. V. No. 8, 2005, pp. 32-34.

- Fritz Wiesenberger: Castle romance right next door. Palaces and castles in Düsseldorf and the surrounding area . 2nd Edition. Triltsch, Düsseldorf 1983, ISBN 3-7998-0007-7 , pp. 47-52.

- Hermann Maria Wollschläger: Castles and palaces in the Bergisches Land . 2nd Edition. Wienand, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-87909-242-7 , pp. 124-127.

- Jens Wroblewski, André Wemmers: Theiss-Burgenführer Niederrhein . Konrad Theiss , Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1612-6 , pp. 84-85 .

Web links

- Jens Friedhoff's entry on Kalkum Castle in the " EBIDAT " scientific database of the European Castle Institute

Footnotes

- ↑ L. Fischer: The most beautiful palaces and castles on the Lower Rhine , 2004, p. 44.

- ↑ entry of the castle in the list of monuments of the city Dusseldorf ( Memento of 29 December 2013 Web archive archive.today ) access on April 23, 2014.

- ↑ Margaret Ritter: Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe 1775-1846. A life for garden art (= sources and research on the history of the Lower Rhine . Volume 7). Droste, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-7700-3054-5 , p. 126.

- ↑ a b c Anja Tischendorf: That could be yours. Looking for a new lord of the castle for Kalkum . Article of 21 February 2014 bild.de .

- ↑ Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH). German chronicles and other history books of the Middle Ages . Volume 2. Hanover, Hahnsche Buchhandlung 1877, pp. 408-409, verse 830-832 ( online ).

- ↑ Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH). Arnulfi Diplomata . Weidmann, Berlin 1940, pp. 159-160, no. 107a ( online ).

- ↑ Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH). The documents of the German kings and emperors . Volume 1. Hanover, Hahnsche Buchhandlung 1879–1884, pp. 171–172, No. 89 ( online ).

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ a b Entry by Jens Friedhoff on Kalkum Castle in the scientific database " EBIDAT " of the European Castle Institute

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 20.

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet : Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine . Volume 1. Wolf, Düsseldorf 1840, pp. 318-319, No. 453 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c Walther Zimmermann , Hugo Borger (ed.): Handbook of the historical sites of Germany . Volume 3: North Rhine-Westphalia (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 273). Kröner, Stuttgart 1963, DNB 456882847 , p. 324.

- ↑ a b B. Maurer: Kalkum Castle , 2010, p. 112.

- ↑ Jens Friedhoff states in his EBIDAT article as well as Jens Wroblewski in the Theiss Burgenführer Niederrhein that the Lords of Kalkum were already in the Bergisch service in the 13th century.

- ↑ Dietmar Ahlemann: House Remberg. In: Bürgererverein Duisburg-Huckingen eV (ed.), Heimatbuch (Volume III), Duisburg 2015, pp. 175–196.

- ^ A b c G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to its building history , 1955, p. 201.

- ↑ G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 108.

- ↑ G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 125, note 2.

- ↑ Margaret Ritter: Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe 1775-1846. A life for garden art (= sources and research on the history of the Lower Rhine . Volume 7). Droste, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-7700-3054-5 , p. 127.

- ↑ a b G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 109.

- ^ A b W. Bader: On the problems of history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 46.

- ^ K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Heinrich Ferber: "The manors in the Angermund office". In: Contributions to the history of the Lower Rhine. Yearbook of the Düsseldorf History Association . Volume 7. 1893, here pp. 103-104 ( online ).

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to its building history , 1955, p. 202.

- ↑ G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 111.

- ↑ G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Kalkum Castle , 1968, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 113.

- ↑ a b G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 114.

- ↑ a b G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 115.

- ^ A b W. Bader: On the problems of history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 53.

- ↑ G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ a b c K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , 1995, p. 10.

- ^ A b G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 211.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 52. In his publication, however, Pfeffer states that the increase only took place after Leydel left (and thus at the earliest in 1815). See K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , p. 13.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 51.

- ↑ a b c W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 68.

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 214.

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 215.

- ↑ a b c K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , 1995, p. 15.

- ^ F. Wiesenberger: Schloßromantik next door , 1983, p. 50.

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 221.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 61.

- ^ A b c W. Bader: On the problems of history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 72.

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 223.

- ^ A b G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 222.

- ↑ Harald Herzog: Rheinische Schlossbauten in the 19th century (= Landeskonservator Rheinland. Arbeitshefte . Volume 37). Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1981, ISBN 3-7927-0585-0 , p. 67.

- ↑ a b F. Wiesenberger: Schloßromantik next door , 1983, p. 52.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 122.

- ↑ a b c d Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 143.

- ↑ a b c Rita Hombach: Landscape gardens in the Rhineland. Recording of the historical inventory and studies of garden culture of the "long" 19th century (= contributions to architectural and art monuments in the Rhineland . Volume 37). Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2010, ISBN 978-3-88462-298-8 , p. 157.

- ^ Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 145.

- ↑ a b K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , 1995, p. 18.

- ↑ Margaret Ritter: Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe 1775-1846. A life for garden art (= sources and research on the history of the Lower Rhine . Volume 7). Droste, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-7700-3054-5 , p. 128.

- ↑ Margaret Ritter: Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe 1775-1846. A life for garden art (= sources and research on the history of the Lower Rhine . Volume 7). Droste, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-7700-3054-5 , pp. 133-134.

- ^ Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 148.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 65.

- ^ R. Watty: Kalkum Castle , 2005, p. 33.

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 233.

- ^ Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 153.

- ↑ a b Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 150.

- ↑ Gregor Spohr, Ele Beuthner: How nice to dream away here. Castles on the Lower Rhine . Pomp , Bottrop / Essen 2001, ISBN 3-89355-228-6 , p. 32.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 124.

- ↑ a b William Stüwer: Castle Kalkum as a branch archive of the Düsseldorf State Archives . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 261.

- ↑ a b K. E. Krämer: Von Brühl bis Kranenburg , 1979, p. 92.

- ↑ a b William Stüwer: Castle Kalkum as a branch archive of the Düsseldorf State Archives . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 262.

- ↑ Dieter Schiffer: The restoration of the painting in the basement of the classicist mansion . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 224.

- ^ A b c d Wilhelm Stüwer: Kalkum Castle as a branch archive of the Düsseldorf main state archive . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 264.

- ↑ a b K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , 1995, p. 22.

- ^ Helmut Blasberg: The structural restoration of Kalkum Castle after the Second World War . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 173.

- ↑ a b Helmut Blasberg: The structural restoration of Kalkum Castle after the Second World War . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 181.

- ↑ a b K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , 1995, p. 7.

- ↑ a b Helmut Blasberg: The structural restoration of Kalkum Castle after the Second World War . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 183.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 44.

- ^ Helmut Blasberg: The structural restoration of Kalkum Castle after the Second World War . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 186.

- ^ Helmut Blasberg: The structural restoration of Kalkum Castle after the Second World War . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 189.

- ↑ a b Helmut Blasberg: The structural restoration of Kalkum Castle after the Second World War . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 191.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 70.

- ↑ a b Helmut Blasberg: The structural restoration of Kalkum Castle after the Second World War . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 192.

- ^ Fritz Holthoff: Foreword . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 8.

- ↑ William Stüwer: Castle Kalkum as a branch archive of the Düsseldorf State Archives . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 278.

- ^ History of the Rhineland Department of the State Archive of North Rhine-Westphalia on archive.nrw.de , accessed on July 19, 2015.

- ↑ G. Dehio, C. Euskirchen (edit.): Handbook of German Art Monuments. North Rhine-Westphalia . Volume 1: Rhineland, 2005, p. 332

- ^ Wilhelm Avenarius, Bernd Brinken: Düsseldorf and Bergisches Land. Landscape, history, folk, culture, art . Glock and Lutz, Heroldsberg 1982, p. 244.

- ^ Wilhelm Avenarius, Bernd Brinken: Düsseldorf and Bergisches Land. Landscape, history, folk, culture, art . Glock and Lutz, Heroldsberg 1982, p. 245.

- ↑ Çà et là . In: Revue d'histoire de la pharmacie . Vol. 81, No. 298, 1993, pp. 302-303 ( online ).

- ^ Herbert Slevogt: Open Kalkum Castle! In: Düsseldorfer Hefte . Volume 50. VVA Kommunikation, Düsseldorf 2005, ISSN 0012-7027 , pp. 48-49.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Kirfel: "There is no better location" . In: Rhein-Erft Rundschau . Edition of October 10, 2007 ( online ).

- ↑ Wolfgang Berney: Castles are looking for new masters . In: Rheinische Post . Edition of October 3, 2007 ( online ).

- ↑ AS: Kalkum Castle is to become an Academy for Music and Art. Westdeutsche Zeitung , January 14, 2019, accessed on March 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Julia Brabeck; Uwe-Jens Ruhnau: The sale of Kalkum Castle has been completed. March 19, 2019, accessed on June 17, 2020 (German).

- ↑ Dieter Sieckmeyer: The fields at Kalkum Castle in Düsseldorf remain undeveloped. In: Westdeutsche Zeitung. November 12, 2019, accessed June 17, 2020 .

- ↑ Julia Brabeck: Kalkum Castle in Düsseldorf: The future of Kalkum Castle is still open. Retrieved June 17, 2020 .

- ^ Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 144.

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 204.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 47.

- ^ Fritz Holthoff: Foreword . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 7.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Schroff: Kalkum - district with moated castle . In: Jan Wellem . No. 4, 2008, p. 6 ( online ).

- ^ K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , 1995, p. 13.

- ↑ G. Engelbrecht: Kalkum Castle, its historical significance and structural development . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 110.

- ↑ Margaret Ritter: Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe 1775-1846. A life for garden art (= sources and research on the history of the Lower Rhine . Volume 7). Droste, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-7700-3054-5 , p. 132.

- ^ W. Bader (Ed.): Kalkum Castle , 1968, p. 98, black and white board 49.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 49.

- ↑ B. Maurer: Kalkum Castle , 2010, p. 113.

- ^ F. Wiesenberger: Schloßromantik next door , 1983, p. 51.

- ^ W. Bader (Ed.): Kalkum Castle , 1968, p. 198, black and white board 48.

- ^ W. Bader (Ed.): Kalkum Castle , 1968, p. 238, black and white board 66.

- ↑ Dieter Schiffer: The restoration of the painting in the basement of the classicist mansion . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 226.

- ↑ William Stüwer: Castle Kalkum as a branch archive of the Düsseldorf State Archives . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 273.

- ^ W. Bader: On the problem of the history, preservation of monuments and the classification of the landscape of Kalkum Castle . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 64.

- ↑ L. Fischer: The most beautiful palaces and castles on the Lower Rhine , 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 142.

- ^ Rita Hombach: landscape gardens in the Rhineland. Recording of the historical inventory and studies of garden culture of the "long" 19th century (= contributions to architectural and art monuments in the Rhineland . Volume 37). Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2010, ISBN 978-3-88462-298-8 , p. 160.

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 232.

- ^ Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 147.

- ↑ a b Georg Fischbacher: The castle park, its history and restoration . In: W. Bader (Ed.): Schloss Kalkum , 1968, p. 149.

- ↑ Margaret Ritter: Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe 1775-1846. A life for garden art (= sources and research on the history of the Lower Rhine . Volume 7). Droste, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-7700-3054-5 , p. 131.

- ^ Rita Hombach: landscape gardens in the Rhineland. Recording of the historical inventory and studies of garden culture of the "long" 19th century (= contributions to architectural and art monuments in the Rhineland . Volume 37). Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2010, ISBN 978-3-88462-298-8 , p. 164.

- ↑ a b K. Pfeffer: Düsseldorf-Kalkum , 1995, p. 21.

- ^ G. Engelbert: Kalkum Castle near Düsseldorf. A contribution to his building history , 1955, p. 234.

Coordinates: 51 ° 18 ′ 15.2 " N , 6 ° 45 ′ 27.5" E