State crisis in Egypt 2013/2014

After recurring protests against President Mohammed Morsi since November 2012 had become increasingly violent in June 2013 , the military staged a coup on July 3, 2013 , overthrew the government, suspended the constitution and took power. Protests by opponents of the coup, especially supporters of the ousted president, have continued for months since the coup. There were bloody clashes and mass killings, in which well over a thousand people, mostly coup opponents, have died.

That the Military Council chief Abdel Fattah El-Sisi led military described the coup as a "second revolution", claiming the overthrow Mursi was willed by people who had been dissatisfied with political and economic grievances. The generals also accused the Muslim Brotherhood of following a US and EU agenda while pursuing a policy of terror by supporting the Islamist insurgents who fought the military in Sinai . Western media reported that Morsi was deposed after he disappointed many Egyptians' hopes for democratization after the fall of Mubarak in 2011. Supporters of the ousted President Morsi and human rights groups accused the military of having overthrown the elected president in a coup and of wanting to return to the regime of the long-time ruler Mubarak .

An alliance of the military, the judiciary and the security apparatus worked together in the fall of Morsi. The coup was led by the Coptic patriarch , Pope Tawadros II , the imam of Cairo's al-Azhar University , Grand Sheikh Ahmed Tayeb , representatives of the Tamarod protest movement and, at least initially, by the left-liberal leader of the opposition alliance National Salvation Front , Mohammed el-Baradei , and representatives of the Salafists Party-only officially endorsed and welcomed.

Before and after the establishment of a partially civil, anti-Islamist and unelected transitional government under interim prime minister Hasim al-Beblawi by the military in July, the situation escalated again into mass killings of members of the Muslim Brotherhood by Egyptian security forces. A high point of the violence was the bloodbath caused by the security forces during the evacuation of the pro-Mursi protest camps on Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya and Nahda Squares in Cairo on August 14, 2013. When the two protest camps in Cairo were stormed According to the military-backed transitional government, at least 378 people were killed and thousands more injured on the following day, according to recent reports by international human rights organizations and Western media around 1000 and according to the Muslim Brotherhood more than 2000 pro-Morsi demonstrators. Almost all of the more than 1,000 people killed in July and August were civilians who had demonstrated against military chief Sisi and were shot dead by the security forces. In the summer of 2013 alone, the ruthless crackdown on the anti-coup protests in Cairo by the security forces killed at least 1,400 people, some of them through systematic shootings.

The state of emergency, imposed by the military-backed transitional government on August 14 and extended by two months in mid-September to mid-November 2013, gave authorities and emergency services special rights in dealing with protests and gatherings and made it difficult for the media to work in the country. The Vice President Mohammed el-Baradei, who resigned in protest, fled abroad to avoid arrest. Freedom of the press has been restricted, the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood has been imprisoned and thousands of Muslim Brotherhood arrested. All Muslim Brotherhood organizations have been banned and their property has been confiscated. The ban was seen as an indication that the Muslim Brotherhood should be excluded from the military-installed transitional government promised for 2014. Following a court order, the interim government declared the end of the state of emergency on November 14th.

The ousted President Morsi has been held in an undisclosed location since the coup on July 3rd until his trial began on November 4th. He and 14 other leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood were tried for inciting violence. They face life imprisonment or the death penalty . The upcoming trial sparked concerns at home and abroad that the army led by military chief Sisi would turn the country, which had been hoping for a democratic course since the fall of Mubarak in 2011 , back into a police state .

By the beginning of October, the number of people killed since the coup had risen to 2,000 and continued to grow every week. The series of violence that has continued since the fall of Morsi has been interpreted as an indication of a growing instability in Egypt. In the months after the coup, significantly fewer tourists came to Egypt. On October 9, the US government, which initially justified the coup, froze parts of its military aid to Egypt for the time being.

At the end of March, military chief Sisi officially announced that he would run for the presidential election. He will resign from his post as army chief and step down as defense minister and vice prime minister. There was only one other candidate for office, Hamdin Sabahi. Sisi received almost 97 percent of the votes cast.

A few weeks before the presidential election, Egypt, which was in fact ruled by the military, was classified by scholars and observers as an increasingly repressive military dictatorship or as a repressive system in which democracy, the rule of law and human dignity were practically eliminated. At that time, the US stuck to the resumption of its previously limited military aid to Egypt, which had already been decided .

Overview

chronology

The fall of Mubarak:

- January 25, 2011: For the first time tens of thousands demonstrate nationwide against the regime of Hosni Mubarak and demand the resignation of the autocratic President Mubarak in Cairo after the uprisings in Tunisia . The state power under Mubarak is using force against the protesters. Hundreds of demonstrators were killed as a result.

The Tantawi Military Government:

- February 11, 2011: After 30 years of authoritarian rule and an 18-day revolt, Mubarak resigns from mainly young people and appoints his Prime Minister Ahmed Shafiq as head of cabinet. The crowd in Tahrir Square responded to the announcement with “God is great” shouts. The Supreme Military Council takes power . In the West, despite his authoritarian regime, Mubarak was recognized as a guarantor of stability and a fighter against radical Islamists. The military dissolves parliament and suspends the constitution, as the demonstrators demanded. Mubarak is arrested.

- February 14, 2011: The ruling military officers present a timetable according to which constitutional amendments are to be worked out and put to referendum and a new government elected within six months. The day before, the military had consolidated its power by dissolving the weak parliament and overriding the constitution, sparking a debate about the military's long-term intentions.

- 2011: Tourism, which offers almost three million people direct jobs and accounts for 20 percent of state currencies, begins to collapse. The more lucrative cultural tourists in particular are reluctant to return to Egypt over the next two years. While the police, ubiquitous under Husni Mubarak, had stopped sexual harassment from public places, the withdrawal of the security forces in the next two years since Mubarak's resignation has led to a surge in sexual assaults against women in the open air. In spring 2013 this led to violent disputes about those responsible for this development.

- March 8, 2011: The military council sets up a transitional government, which is subsequently reorganized again and again due to popular dissatisfaction.

- Spring 2011: Since spring, the anger of the population has shifted increasingly to the military council, which is accused of disregarding freedom of expression, of having tried 12,000 civilians in military courts, of wanting to anchor the power of the military in the constitution and the security forces brutally oppose it to let protesting demonstrators go ahead.

- March 19, 2011: The Egyptians vote in a constitutional referendum for a constitutional amendment that limits the president's term of office to a maximum of eight years and makes the declaration of a state of emergency subject to parliamentary approval.

- October 9, 2011: The Coptic Maspero protests , taking place against the background of sectarian tension , lead to the most serious outbreak of violence since Mubarak's resignation in February 2011. At least 25 people are killed, according to eyewitness reports, some of them by deliberately being run over by army vehicles. The Supreme Military Council blames foreign "conspiracies", sectarian tensions or the demonstrators.

- November 1, 2011: While the election date is being postponed, the military, which a few months previously had been hailed as the savior of the Mubarak regime, is seizing more and more power, preventing freedom of the press and banning demonstrations. Since many people no longer trust traditional media, people are increasingly getting information via Facebook, blogs and online newspapers.

- November 21, 2011: The interim government under Essam Sharaf resigns. The military council then appoints Kamal al-Ganzuri as head of government. The efforts of the opaque military council in the previous months are seen as an attempt to secure the power of the military in Egypt for the period after the elections on November 28th. The military council is accused of prescribing the guidelines for the still-to-be-drafted constitution and of wanting to prevent the parliament, which consists of the lower house and the Shura council, from gaining control over the military budget. The actions of the military council are supposed to be more brutal than the Mubaraks. The state of emergency is still not lifted.

- November 22, 2011: The Military Council announces the presidential election for June 2012. Shortly thereafter, the military allegedly wants to give up power. The street fights between the demonstrators and the military continue.

- November 28, 2011 to 3rd / 4th January 2012: The Muslim Brotherhood wins almost half in the parliamentary elections , the ultra-conservative Salafists get a quarter of the seats in the lower house, so that the Islamists have 70 percent of the seats. The liberal Wafd party took third place with 8 percent. The election of the upper house (Shura Council) as the second chamber of parliament was also won by the Islamists (Muslim Brotherhood with 38 percent, party-only with 16 percent), while the liberal Wafd party received five percent.

- January 2012: Mohammed el-Baradei withdraws his presidential candidacy on the grounds that democracy in the country is not yet ready for him to run with a clear conscience.

- January 25, 2012: The state of emergency that has existed since 1981 is lifted.

- February 1, 2012: 74 people died as a result of riots at Port Said football stadium . The military council and the police are suspected, among other things, of specifically promoting this and other riots in order to cement the desire of the population for solid leadership.

- March 24, 2012: Both chambers of parliament elect a constitutional commission to revise the constitution one more time.

- April 10, 2012: In response to a complaint by liberal parties, a court declares the constitutional commission illegitimate because the parliament exceeded its powers in putting together the commission.

- 23/24 May 2012: In the first round of the presidential election, Mohammed Morsi, candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood, and Ahmed Schafik, the last head of government under Mubarak, achieve the best results and reach the runoff election.

- June 2, 2012: A criminal court in Cairo sentenced the ousted Egyptian President Mubarak to life imprisonment for the ordered killing of over 800 demonstrators with a guilty verdict that state television referred to as the “verdict of the century”. The defense announces that they will appeal. In several cities, thousands of people are protesting against what they consider to be too mild a judgment.

- June 12, 2012: Both chambers of parliament elect a new constitutional commission, which is dominated by Islamists. Decisions should be made with a two-thirds majority.

- June 14, 2012: The Supreme Constitutional Court declares the election of the lower house to be invalid and decides to dissolve parliament two days before the runoff to the presidential election. Court President Faruk Sultan declares that the Military Council will take over the legislature until new elections for a new House of Commons have taken place. At the same time, the court decides that Ahmad Schafiq , who is preferred by the military as a candidate , can run for the runoff election, the air force commander, aviation minister and last prime minister of President Mubarak, who the Muslim Brotherhood suspect as a representative of the military council. The parliament had previously passed a law against the political activities of officials of the old regime, but the supreme electoral commission had declared it to be inconsistent. After the two rulings, protesters clash with the security forces before the Constitutional Court. Egypt now has neither a parliament nor a constitution, while the Supreme Military Council controls both legislative and executive powers. The event is rated as a "silent coup by the military". Mohammed Morsi later declared the judgment null and void as the new president, but the Constitutional Court upheld it and Morsi relented.

- 16./17. June 2012: Former Muslim Brother Mohammed Morsi wins the runoff election against Ahmad Schafiq in the presidential election with 51.7% of the vote.

- June 24, 2012: Mohammed Morsi becomes the first democratically elected president as the candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood after the runoff election . However, due to the powers conferred on it by the most recent constitutional amendments, the Military Council controls the legislative process, the budget, the composition of the Constituent Commission and the contents of the new constitution, and thus de facto the entire constituent process.

- June 29, 2012: Mursi takes the oath of office as President on Cairo's Tahrir Square in the presence of his supporters in an unofficial procedure and opens his jacket to show that he is not wearing a bulletproof vest. The unofficial oath is seen by various commentators as an artifice by Mursi to defy the Supreme Military Council, which, through a constitutional declaration of March 2011 and an amendment during the presidential election of June 2012, reserved large parts of power for itself.

Mursi's Presidency:

- June 30, 2012: Morsi was officially sworn in as President after his election victory before the Supreme Constitutional Court in Cairo instead of before the People's Assembly in the lower house. The Supreme Military Council had previously ordered the dissolution of the People's Assembly in June, in which the Muslim Brotherhood held a majority, after the Supreme Constitutional Court ruled that a legal error had been committed in the election to the People's Assembly.

- July 9 to July 11, 2012: Morsi orders that the dissolved people's assembly be reinstated, which is to exercise its function until another people's assembly has been elected two months after a constitution to be drafted. On July 11, the President accepted a July 10 order from the Supreme Constitutional Court suspending Morsi's decision to reinstate the House of Commons, citing his respect for judicial decisions as a reason for accepting the court decision. Morsi's re-convening of the democratically elected parliament, which had been dissolved by the generals following an urgent court decision, was followed by an escalation of the power struggle between the Muslim Brotherhood and the military in July. The Supreme Court of Egypt and the generals reject Morsi's order, but in disregard of the Supreme Court and the military, Parliament rallies and votes to appeal the court decision. What follows is a jumble of opposing judicial authorities and jurisdictions. The power struggle reflects competing claims in emerging Egyptian politics, with each side trying to portray the debate as a contest of ideals, legitimacy and democracy.

- July 19, 2012: Mursi orders the release of 572 detainees who had been detained by the military during the transition period led by the Supreme Military Council after the January 2011 revolution. A broad campaign called "No to Military Courts" had previously called for the release of all those arrested through military tribunals or sentenced to prison terms.

- July 30, 2012: Morsi pardons 26 Islamist convicts in his capacity as president, most of whom belong to al-Jamāʿa al-islāmiyya and other hard-line Islamist groups as well as the Muslim Brotherhood. Some had been sentenced to the death penalty by State Security Courts.

- August 2, 2012: Morsi appoints Hisham Kandil , the Islamist-leaning Minister for Irrigation and Water Management of the expiring government of Prime Minister Kamal al-Ganzuri , as Prime Minister. For the first time in Egyptian history, Kandil appoints a cabinet that includes ministers from the Muslim Brotherhood and allies.

- August 8, 2012: After an attack by unknown militants on a security checkpoint , in which 16 Egyptian soldiers were killed, Morsi orders a restructuring of the security area and dismisses the secret service chief Murad Muwafi , the governor of North Sinai and various officials from the Interior Ministry .

- August 12, 2012: Morsi amends the March 2012 constitutional declaration, significantly restricts the prerogatives of the military in power since the overthrow of the former ruler Husni Mubarak and overrides constitutional amendments of the Supreme Military Council, which restricted the power of the president in favor of the military . Lawyers criticize that he has exceeded his competencies. With the same decree, Morsi sends the Chief of the Supreme Military Council and Defense Minister Field Marshal, Mohammed Hussein Tantawi , as well as the second most important figure in the Military Council, Sami Enan , into retirement and appoints the military intelligence chief Abd al-Fattah as-Sisi as the future Defense Minister to head the armed forces .

- August 14, 2012: Mursi awards Tantawi the highest state award and Enan a state award. Both will now become advisors to the President following the decree that retired them. The move is described as a “soft coup” against the military, but some opposition activists criticize that the Supreme Military Council should be held accountable for violence against demonstrators during the military regime.

- August 15, 2012: On his second state visit to Saudi Arabia - the only country visited by the Egyptian President until then - Morsi calls for an end to the rule of President Bashar al-Assad in Syria, where a "civil war" between the Syrian military and armed forces Insurgents rages.

- August 23, 2012: Morsi enacts a law that prohibits journalists from pre-trial detention for media-related violations.

- August 27, 2012: President Morsi appoints personal advisors, including Christians, Liberals, Salafists and many members of the Muslim Brotherhood.

- August 30, 2012: In a move causing concern in the US, the Egyptian President visits Iran - for the first time in 30 years - to attend a meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement . Morsi criticizes Iran's support for the Syrian regime.

- October 9, 2012: Morsi, in his capacity as president, issues amnesty to citizens arrested for acts in support of the revolution between the beginning of the January 25th revolution and June 30th, 2012.

- October to November 2012: Legal disputes and constitutional declaration.

- October 12, 2012: Riots broke out in Cairo because former Mubarak people, who are believed to be responsible for camel attacks on demonstrators in 2011, were acquitted. Mursi then wants to dismiss the attorney general, but ultimately it does not come to that.

- November 21, 2012: Morsi receives US praise for his role in brokering a ceasefire between Hamas, ruling Palestinian Gaza, and the government of Israel after over 160 people were killed in Israeli air strikes and Palestinian rocket attacks within a week .

- November 22, 2012: Morsi decides to restrict the powers of the judiciary with a constitutional amendment and tries to dismiss Prosecutor General Abdel Meguid Mahmud by appointing him as Egyptian ambassador to the Vatican state. After Mahmud and other judges challenge Morsi, who under Egyptian law does not have the power to dismiss the attorney general, Morsi gives in. Public unrest is forcing Morsis to reverse some of the proposals.

- 29./30. November 2012: The constitutional commission, dominated by Islamist representatives and boycotted by the opposition, pushes through its draft of a new constitution in an urgent manner. Women's rights activists, Christians and liberals criticize the constitutional text. The mass protests continue.

- 8/9 December 2012: Mursi gives in to the conflict with the opposition after massive pressure and revokes his special powers, which were extended by decree.

- 15./22./24. December 2012: Almost two thirds of the population vote for the Egyptian government's draft constitution. While mainly secular critics describe the document as a fraud in the revolution, the Islamists disagree. Mass protests followed, with some fatal violence.

- December 29, 2012: As stipulated in the new constitution, Morsi officially hands over authority to the Upper House of Parliament in one language before the now complete Shura Council. He emphasizes the right to vote of the House of Representatives (formerly the People's Assembly, the lower house of Parliament) as urgent.

- January 24, 2013: On the second anniversary of the uprising against Mubarak, over 50 people were killed in one week.

- January 25, 2013: The Tahrir Square in Cairo is once again a focal point of Egyptian protesters. On the second anniversary of the start of the revolt against Mubarak, the angry crowd calls on President Morsi to resign.

- January 6, 2013: Mursi carries out his promised government restructuring, 10 new ministers are sworn in, including key positions in the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Finance. Contrary to calls for a less partisan government, the new cabinet includes eight FJP members instead of five prior to the restructuring. The new finance minister, Morsi El Sayed Hegazy, is an Islamist financial expert.

- 26./27. January 2013: In Cairo, judges sentenced 21 people to death for their involvement in football riots that killed 74 people in Port Said in February 2012 . Many consider the February 2012 event to be a “massacre” of fans of the football club orchestrated by the then ruling Supreme Military Council in complicity with the Ministry of the Interior. Following the verdict, violent football fans organized rioting in Port Said, leading to an escalation of violence with dozens of dead and hundreds of injuries. Mursi imposed on 27./28. January the state of emergency over Port Said, Suez and Ismailia on the Suez Canal. Nonetheless, the unrest continues.

- January 28, 2013: The most important opposition alliance, the National Salvation Front , refuses to enter into a dialogue with Morsi. Opposition leader Mohammed el-Baradei says the National Salvation Front rejects a “fake” dialogue.

- January 29, 2013: Military chief Sisi announces that national security is threatened and that the state is threatened with collapse.

- January 30th: On a short trip to Europe, which was canceled due to the escalating violence in Egypt, Morsi's attempt to obtain debt relief in Germany and to strengthen the confidence of German investors in Egypt failed.

- February to March 2013: Loss of the Salafists as the main allies of the Peace and Justice Party.

- February 5, 2013: Morsi welcomes Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad , who wants to attend a meeting of the Organization for Islamic Cooperation in Egypt, at Cairo Airport. It is the first such visit since the worsening Egyptian-Iranian relationship in 1979. Egyptian Salafists criticize the visit and warn of Shia influence in Egypt.

- February 11, 2013: Over ten thousand Egyptians demonstrate on the second anniversary of Mubarak's resignation. Violent protests continued in several cities in the weeks that followed.

- February 21, 2013: The Egyptian President announces that the first post-constitution election for the lower house of the House of Representatives will be held in April while the House of Lords Shura Council prepares a new electoral law.

- February 26, 2013: Another meeting of the “national dialogue” with Morsi to discuss the upcoming parliamentary election is boycotted by the National Salvation Front . Disagreements between the President and the Muslim Brotherhood, on the one hand, and the Nur party's former allies emerged when Nur party leader Younis Makhioun criticized Morsi's decision to announce a date for the election without the Nur party or the most recent joint Having consulted the initiative of the Nur party with the National Salvation Front. Makhioun accuses the Muslim Brotherhood of trying to monopolize state institutions.

- March 6, 2013: The Egyptian administrative court rejects Morsi's decree calling for parliamentary elections to be held in April on the grounds that an article of the electoral law needs to be re-examined by the constitutional court. In a statement, the President declares that he will respect the court's decision.

- March 8, 2013: The election commission joins the decision of the Constitutional Court and decides to postpone the parliamentary election planned for April . A few days later, Mursi appeals against it. A broad alliance of Egyptian opposition parties had called for an election boycott. The opposition has repeatedly criticized the electoral laws, which they claim give the Islamic parties an advantage.

- March 24, 2013: Numerous attacks on Freedom and Justice Party's offices and clashes between supporters and opponents of the president in Egypt seem to indicate a rise in sentiment against the Muslim Brotherhood.

- March 28, 2013: State news agencies report that Morsi hopes the general election will take place in October.

- April to May 2013: Diplomatic tensions and solidification of the opposition.

- April 10, 2013: Morsi orders the withdrawal of all legal complaints against Egyptian journalists when his regime is attacked to investigate media personalities for "insulting the president".

- April 20, 2013: Morsi announces an upcoming restructuring of the government.

- April 21, 2013: The Supreme Administrative Court of Egypt rejects the President's appeal against the decision to suspend the parliamentary elections.

- May 7, 2013: Mursi reshuffles his cabinet, but fails to appease the opposition. The number of ministers belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood increases by three to eleven from 35.

- June 2, 2013: The Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt denies the legitimacy of the upper house of parliament, which is dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists . The constitution enforced by Mursi declares it to have not come into existence under legal circumstances.

- June 4, 2013: The judiciary issued prison sentences of several years in some cases against 43 domestic and foreign employees of non-governmental organizations, including the CDU-affiliated Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, for illegal activities. International protests follow.

- June 6, 2013: According to media reports , the anti-Morsi signature campaign Tamarod , which was founded in May and aims to force Morsi out of office, allegedly wants 15 million signatures for the petition to withdraw trust in the president Millions more than he received votes in the election). Tamarod announces plans for mass demonstrations and sit-ins at the presidential palace for June 30, the first anniversary of Morsi's inauguration, to enforce their demands.

- June 17, 2013: Morsi appoints seven Muslim Brotherhoods to the posts out of 16 newly appointed provincial governors. Critics refer to this as an example of an Islamist attempt to monopolize power and exclude other forces from the decision-making process, as 27 of the Egyptian provinces are under the control of governors with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. Among the newly filled posts is the Provincial Governor of Luxor, a member of the former terrorist group Gamaa Islamija . The Gamaa Islamija member later resigns under public pressure. The appointments sparked a wave of protests and clashes between supporters and opponents of the Muslim Brotherhood in various governorates. This contributes to the general unrest in the country when clashes broke out across the country between supporters of Morsi and supporters of the Tamarod campaign in the run-up to the June 30 demonstrations.

- June 20, 2013: The Tamarod campaign wants to force Mursi to resign. Media reports that she apparently collected several million signatures.

- June 21, 2013: Tens of thousands of people demonstrate in the streets in support of Morsi.

- June 23, 2013: The military threatens military intervention if the protests escalate.

- June 24th, 2013: The Freedom and Justice Party confirmed on Friday (June 28th) before the nationwide planned protests of June 30th of the "unlimited demonstration" "Legitimacy is a red line" to participate. The sit-in is to take place at Cairo's Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Mosque in Nasr City, a traditional meeting place for supporters of Mursi.

- June 28, 2013: Thousands of Egyptians take to the streets in the run-up to new large-scale demonstrations to demand the resignation of Morsi. At least three people, including a US citizen, die in clashes. After the killing of the US citizen, the US government allows some of its embassy staff to leave Egypt.

- June 29, 2013: The opposition Tamarod campaign declares that it has collected more than 22 million signatures for Morsi's resignation.

- June 30, 2013: On the occasion of the one-year existence of President Morsi's term of office, hundreds of thousands of people gathered for mass protests after the signature campaign of the “Tamarod” campaign to demand Morsi's resignation. The media also speak of "millions" of protesters. At the same time there are solidarity rallies for Mursi. Eight people are killed in clashes and shootings in front of the Muslim Brotherhood headquarters in Cairo.

The Sisis military coup:

- July 1, 2013: Opponents of the government storm and devastate the headquarters of the Muslim Brotherhood in Cairo. Tamarod sets Mursi a resignation ultimatum until the following day. The military gives President Morsi an ultimatum to reach an agreement with the opposition within 48 hours. Otherwise the military will push through its own solution.

- July 2, 2013: Mursi refuses to resign and lets Tamarod's ultimatum expire.

- July 3, 2013: Morsi refuses to resign from the military even after the ultimatum has expired. The military decides that the country has reached a political impasse, removes President Morsi, places him under arrest, repeals the constitution and orders a technocratic interim government. Military chief General Abd al-Fattah as-Sisi appoints the President of the Supreme Constitutional Court , Adli Mansur, as transitional president. Mursi is taken to an unknown given location. Muslim Brotherhood leaders are arrested. Tens of thousands of Mursi supporters take part in permanent sit-down protest camps at the Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Mosque in the Nasr City district of Cairo and on Nahda Square in Giza.

- July 4, 2013: The highest constitutional judge, Adli Mansur, is sworn in as interim president. Cairo's Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Mosque becomes the scene of ongoing bloody battles with security forces as a protest camp for pro-Mursi supporters. Many people die in clashes with the military. Leading Muslim Brotherhoods are arrested.

- July 5, 2013: Interim President Mansur dissolves the House of Lords (Shura Council) as the first official act as the last representative body in which Islamist parties had won a clear majority through elections. Dozens of people die in clashes between pro and anti-Morsi groups. US President Barack Obama and other world leaders are urging Egypt to swiftly restore civilian government. Supporters of the ousted President Morsi accuse the new interim authorities of brutally acting against their remaining leaders.

- July 7, 2013: Hundreds of thousands protest across Egypt for and against the overthrow of Morsi by the military. A spokesman for interim president Mansur denies previous reports that Mohammed el-Baradei will become head of the interim government as interim prime minister. Instead, el-Baradei is given the post of vice-president.

- July 8, 2013: Security forces shoot 53 Mursi supporters at a protest camp on the grounds of the Republican Guard in the bloodiest state carnage since the fall of Hosni Mubarak in 2011 , where Morsi is rumored to be held. Mansur presented a timetable for a revision of the constitution and election of a new president as well as parliamentary elections for mid-February. The Muslim Brotherhood rejects the proposals and insists on the reinstatement of Morsi.

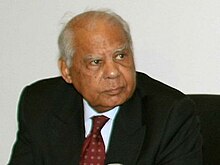

- July 9, 2013: Mansur appoints the opposition leader Mohammed el-Baradei as deputy president and the economist Hasim al-Beblawi as interim prime minister. The Egyptian military supports the appointments. Mansur announces the holding of parliamentary and presidential elections after a previous referendum on a revised draft constitution for 2014 at the latest.

- July 12, 2013: Thousands of Mursi supporters demonstrate in mass protests across the country. The German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle demands the release of the detained ex-President Mursi.

- The Sisis Military Government / Transitional Government

- Mansur Presidency - Beblawi Cabinet:

- July 16, 2013: An interim government without the participation of Islamist parties is sworn in. The Muslim Brotherhood does not participate in the government and reject it as illegitimate. The military has a strong political role in the cabinet. The army chief Sisi, who was responsible for the overthrow of Morsi, is appointed as deputy to interim prime minister Hasem al-Beblawi. At least seven people are killed and more than 200 injured in riots in Cairo.

- July 19, 2013: The British daily The Guardian publishes research according to which the military targeted attacks and apparently shot 54 people at the protest rally in front of the headquarters of the Republican Guard in Cairo on July 8, 2013. The Muslim Brotherhood is signaling its willingness to accept the EU as a mediator.

- July 20, 2013: Interim President Mansur instructs a committee of legal experts to revise the Egyptian constitution.

- July 24, 2013: Army chief Sisi calls on the Egyptians to show their solidarity with the military through demonstrations in a fight against “terrorism”. His speech is interpreted as a request for a "mandate" for crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood and its allies. The Muslim Brotherhood calls on its supporters to counter protests and describes Sisi's statements as an “invitation to civil war”.

- July 26, 2013: Prosecutors announce that Morsi is being investigated on a number of charges, including murder and treason by conspiracy with members of Palestinian Hamas for a prison break during the 2011 revolution. Remaining detained in an unknown location, Morsi arrives thus formally in pre-trial detention on judicial instruction. Depending on the source, hundreds of thousands or millions of opponents and supporters of Morsi take to the streets for rival rallies across the country. The Morsi opponents respond to General Al-Sisi's army appeal to give the military leadership a “mandate to fight terrorism” to end “potential terrorism” through Morsi supporters. Five people are killed in clashes between pro and anti-Mursi groups. Previously, the Egyptian military gave the Muslim Brotherhood an ultimatum and announced tougher action against "extremists".

- July 27, 2013: Police kill 95 pro-Mursi protesters on a street leading to the Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya mosque in Cairo. The media sometimes speak of clashes between security forces and armed men in civilian clothes on the one hand and Mursi supporters on the other in the protest camp in front of the Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya mosque in Cairo. According to witness statements, the demonstrators were unarmed and ambushed.

- July 28, 2013: Interim President Mansur issues a decree that allows the military to arrest civilians. At the same time, the military-backed transitional government is threatening the Morsi supporters with “decisive and tough measures” in the event that the “violent” protests continue.

- 30 July 2013: EU Foreign Affairs Representative Catherine Ashton met with officials and opposition leaders, including - in a secret location - Mursi. Ashton, as well as John McCain and Lindsey Graham, are among the international envoys visiting Egypt on an arbitration mandate. Germany, the USA and France again demand Morsi's release.

- July 31, 2013: The military-backed transitional government resolves to forcefully evacuate the two sit-ins on Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Square and Nahda Square in Cairo, which Mursi supporters have been maintaining for weeks. Amnesty International sees the resolution as a "template for a disaster" and the US government calls on the coup leaders to respect freedom of assembly. The prosecution brought charges against the fugitive head of the Muslim Brotherhood, Muhammad Badi'e, and two imprisoned leaders, on charges of “inciting murder” in late June 2013.

- August 1, 2013: US Secretary of State Kerry defends the military coup of July 3 as a restoration of democracy, in which not the military but a civil transitional government took the lead, and justifies it with popular displeasure. He is criticized for this statement.

- August 4: Prosecutors announce the start of a trial of six Muslim Brotherhood leaders for "incitement to murder" on August 25.

- August 7th: The Egyptian interim president Mansur declares the efforts of international diplomats for a peaceful solution between the military-backed interim government and the Muslim Brotherhood to have failed and holds the Muslim Brotherhood responsible. The EU Foreign Affairs Representative Catherine Ashton and US Secretary of State John Kerry do not want to end their diplomatic attempts. The interim government is threatening to crack down on pro-Morsi demonstrations after showing restraint during Ramadan, a holy month for Muslims. She has announced several times that the largest protest camps with thousands of Morsi supporters will be forcibly cleared. The international community fears new bloodshed in the event of an evacuation.

- August 8, 2013: At the end of the fasting month of Ramadan, tens of thousands of demonstrators demand the reinstatement of Morsi. At the entrance to their central protest camp in front of the Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Mosque, the Muslim Brotherhood erect barricades to prevent the camp from being evacuated.

- August 11, 2013: The security forces threatened the demonstrators to disband the ongoing pro-Mursi protest camps at the Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Mosque and Nahda Square within 24 hours. In preparation for a police action, the protesters are strengthening their barricades around their tent camps at the Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Mosque and on Nahda Square.

- August 12, 2013: Authorities postpone planned actions against demonstrators, saying they would like to avoid bloodshed after Morsi supporters fortified their positions and thousands more demonstrators stepped up their sit-ins. Morsi's pre-trial detention is extended for another 15 days. This led to renewed protests and clashes between the two camps.

- August 14, 2013: After a week of false alarms, bloodbath during the forcible evacuation of two protest camps with over hundreds of pro-Mursi protesters killed in Cairo, during which riot police drove protesters out of the extensive protest camps. According to a well-known local human rights group, the police and military killed at least 904 people during the evacuation of the protest camp in Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Square. A few armed demonstrators fight back and kill nine police officers. The interim government imposed a one-month state of emergency in Egypt and a night curfew in over ten provinces. Resignation of the interim vice-president Mohammed el-Baradei in protest against state power. A wave of arrests of high-ranking Muslim Brotherhood begins. Retaliatory attacks by radical Islamists on police stations in several Egyptian cities, including a bloodbath of 11 police officers in Kerdasa. Retaliatory attacks on Christians and Christian property by radical Islamists and pro-Morsi groups, mainly in Upper Egypt, claim at least four lives after the Christian minority is held responsible for the overthrow of Morsi. The largest wave of violence in recent Egyptian history unleashed with over 1,000 deaths within a week, most of which were Islamists killed by the security forces.

- August 15, 2013: The Egyptian security forces were given permission to shoot at people in the event of the use of force. In a televised address, interim Prime Minister Hasem el-Beblawi defends the crackdown and the dissolution of protest camps of the Muslim Brotherhood.

- August 16, 2013: Pro-Mursi groups march through Cairo in protest of the massacre in Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Square and are gunned down by police in the fourth mass killing of Morsi supporters since the fall of Morsi. 95 people are killed in Cairo alone. Beblawi proposes to legally dissolve the Muslim Brotherhood. The international criticism of the military leadership is getting sharper. According to EU Foreign Affairs Representative Catherine Ashton, the transitional government is primarily to blame for the violence.

- August 17, 2013: The police cleared the Fetah Mosque in Cairo from anti-coup protesters trapped in the building after a day-long siege with shootings, tear gas volleys and attacks by the mob on the protesters. According to official figures, at least 173 people have been killed since August 16. According to a report in the Washington Post, military chief Sisi allegedly failed a few days earlier a peace agreement brokered by the USA and its partners from Europe and the Gulf States between the warring parties, as the bloodshed with hundreds of deaths could have been avoided.

- August 18, 2013: 37 detainees on remand arrested on August 14 at the Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya protest camp died from suffocation in police custody during a prisoner transport after a police officer shot CS gas into the police vehicle carrying the prisoners. Most of the prisoners are said to have been supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood. Authorities arrest senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood, including chief Muhammad Badi'e. The interim vice-president Mohammed el-Baradei, who resigned in protest, evaded arrest by fleeing to Vienna. For the first time since Morsi's fall, General Sisi addressed the Egyptians in a speech. He calls on the population not to tolerate any further violence, and he urges the anti-coup protesters to “revise their national position”. The Muslim Brotherhood cancels two demonstrations planned for this day at short notice and justifies this with concerns for the safety of the demonstrators and military snipers allegedly located on the roofs along the route. According to the military-backed transitional government, almost 900 people have died in the four days of unrest since the protest camps were cleared.

- August 19, 2013: Reports announce the imminent release of former autocratic President Husni Mubarak from custody. Public prosecutors are investigating Morsi for responsibility for the killing of demonstrators in December 2012. Later a charge of libel follows. Presumably Islamist extremists kill 25 police officers on the Sinai Peninsula near Rafah. Islamist extremists kill 25 police recruits in a massacre in Sinai as the riot escalates there. The number of attacks on security officers and soldiers in the Sinai Peninsula is increasing. If there were attacks in the following months, at least 100 police officers and soldiers died in similar attacks.

- August 20, 2013: As one of the last leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood to be found at large, Muhammad Badi'e is arrested by security forces on the orders of the military-led government.

- August 21, 2013: The European Union stops arms deliveries to Egypt. Civil aid programs are to continue for the time being. A court orders the release of Mubarak. The next day, he is transferred to a military hospital and remains under house arrest.

- August 25, 2013: The trial of Badi'e and about three dozen other Muslim Brotherhood begins. The indictment is incitement to violence, which is said to have led to the deaths of Morsi opponents on June 30, 2013. The trial is adjourned to October almost immediately.

- August 30, 2013: Nine people are killed in clashes between supporters and opponents of Morsi. In Egypt, Islamist coup opponents regularly protest on Fridays after midday prayer.

- September 5, 2013: The Egyptian Interior Minister survived a bomb attack in the Nasr City district of Cairo when the jihadist uprising spilled over from the Sinai Peninsula to the continent.

- September 7, 2013: Beginning of the largest military offensive in recent history on Sinai against Islamist extremists .

- September 11, 2013: Two suicide attacks committed by the militant group Jund al-Islam on a local headquarters of the Egyptian security forces and a checkpoint of the military claimed at least six lives.

- September 12, 2013: Extension of the state of emergency over 14 provinces for another two months.

- September 16, 2013: Police regain control of the town of Delga, held since August 14 by hard-line Islamist raiders who looted churches in the town.

- September 23, 2013: A court in Cairo rushed to declare the Muslim Brotherhood and all branches of the organization illegal and order the confiscation of their assets.

- October 1, 2013: For the first time since the coup at the beginning of July, a march of supporters of Morsi reached Tahrir Square again to demonstrate.

- October 4, 2013: The Muslim Brotherhood began three-day protests against the military coup. At least four Muslim Brotherhood members are shot dead in the largest demonstrations since the evacuation of the protest camps in Cairo on August 14.

- October 6, 2013: In the nationwide protests of the Muslim Brotherhood that began on October 4 and at the same time the Yom Kippur War was celebrated by supporters of the military , police officers in Cairo and two southern provinces killed at least 57 people in the fifth mass killing since the fall of Morsi. Mursi supporters as they march through West Cairo. According to witness reports, the demonstrators were said to have been unarmed. UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon strongly condemns the violence.

- October 7, 2013: 18 members of the army and police are killed in nationwide attacks.

- October 9, 2013: The USA announced that it would freeze part of its military aid to Egypt for the time being. The Egyptian interim government has now also revoked the status of the Muslim Brotherhood as a non-governmental organization.

- October 11, 2013: After Friday prayers, thousands of supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood again took to the streets across the country to protest against the military and the coup that took place 100 days ago.

- October 20, 2013: In Cairo violent clashes broke out between students and security forces, who were demanding the reinstatement of Morsi.

- October 22, 2013: Sections of the banned Muslim Brotherhood want to reorganize. A group called “Brothers Without Violence” applies to the Ministry of Social Affairs in Cairo for approval as a charity.

- October 28, 2013: Mursi contests the legality of the court a week before the trial against him begins.

- October 29, 2013: The judges in the Badi'e trial against the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood put down the case for incitement to murder and declare themselves biased after security forces refused to allow the accused to be in the courtroom during the proceedings.

- November 3, 2013: US Secretary of State John Kerry declares on his first visit to Egypt since the coup against Morsi that the US government is obliged to cooperate with the Egyptian interim rulers.

- November 4, 2013: The criminal trial begins in Cairo against Morsi, who is charged with inciting the murder of protesters in front of his presidential palace in December 2012. In his first public appearance since his fall and his stay in solitary confinement since July 3, Morsi refuses to recognize the court and causes a tumult among the attending lawyers and journalists. Supporters had called for protests in advance.

- November 6, 2013: An appeals court upheld the ban on the Muslim Brotherhood.

- November 14, 2013: The Egyptian business tycoon and billionaire Naguib Sawiris calls on the Reuters news agency for an immediate one-year ban on all protests, as otherwise the total collapse of Egypt is imminent. He is ready to invest a billion dollars for 2014.

- 24./25. November 2013: Interim President Mansur signs a controversial restrictive demonstration law, according to which demonstrations must now be announced three days in advance. The introduction of the law leads to fears that the transitional government is now striving, as before, mainly Islamists, to also sharply fight secular activists.

- November 27, 2013: Arrest warrants against highly respected secular activists of the anti-Mubarak uprising of 2011 such as Alaa Abd el-Fattah and Ahmed Maher , who also called for the overthrow of Morsi in June 2013, confirm in the eyes of many that the transitional government is striving to each Eliminate form of dissenting opinion.

- December 1, 2013: Completion of the draft constitution, on the contents of which a referendum is scheduled for January 2014. While the previous version, written under Morsi, was perceived by critics as pioneering religious rule, the new draft lacks some religious paragraphs and is praised for several new additions, but critics complain that it continues to grant the army too many privileges.

- December 14, 2013: It is announced that interim president Adli Mansur will hold a referendum on the newly drafted constitution on January 14th and 15th.

- December 18, 2013: New charges are brought against Morsi, accusing him, despite traditionally difficult relations between Shiite Iran and the Sunni Brotherhood, of masterminding an elaborate seven-year plot that includes the Palestinian Hamas and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard .

- December 24, 2013: At least 15 people died in the deadliest bomb explosion by militant assassins against security forces since the coup against Morsi in July 2013. The second attack on a police headquarters north of Cairo is the worst attack outside the anarchic Sinai and once again raises doubts as to whether the transitional government will be able to guarantee security a few weeks before the referendum on the draft constitution.

- December 25, 2013: The Egyptian interim government officially classifies the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. She justifies the terror classification with the bomb attack in Mansura the day before, although the jihadist-Islamist group Beit Ansar al-Makdess , which comes from Sinai and is closely related to the terrorist organization al-Qaeda, had previously claimed responsibility for the bomb attack on December 24th in Mansura.

- January 12, 2014: Army chief Sisi announces that he will run for the presidency if the Egyptian people and the army so choose.

- 14./15. January 2014: Constitutional referendum held. The constitution put to the vote does not differ radically from the constitution drawn up under Morsi. Formally it contains more rights for citizens than previous constitutions, but privileges the military. The Muslim Brotherhood calls for a boycott. With a turnout of 38.6 percent, according to a later announcement by the electoral commission, 98.1 percent of the votes are in favor of the constitution. The transitional government hailed the election victory as a clear demonstration of support for its policies after the fall of Morsi. However, the turnout, which corresponds to over 20 million Egyptians, is rated as low in view of the repression of constitutional critics.

- January 24, 2014: In Cairo, a city that has been one of the most stable in the Arab world for decades, on the eve of the third anniversary of the uprising against Mubarak, four independent bomb explosions, apparently all against the police, kill at least six people and injure more as 70. Apparently the attacks sparked spontaneous gatherings of supporters of General Sisi.

- January 25, 2014: On the third anniversary of the revolution against Hosni Mubarak, dozens of people died in pro-Morsi and anti-government demonstrations across the country, including 64 in Cairo and Giza, of whom at least 58 were shot. In the Matariya district of Cairo alone, 26 people were killed during the violent breakup of a pro-Mursi demonstration by the police. According to independent information, however, 108 people were killed.

- January 27, 2014: The head of the military junta, General Sisi, gives himself the title of Field Marshal and takes the first formal step to become the new Egyptian President, while insisting on "free choice of the masses" and the " Call of Duty ”to add. The highest military institution gives the military chief approval for the presidential candidacy.

- January 28, 2014: Morsi faces trial on a prison break allegation that released more than 20,000 prisoners from Egyptian prisons in 2011, including Morsi himself.

- February 11, 2014: Third anniversary of Mubarak's deposition.

- February 13, 2014: Russian President Vladimir Putin said he would support a presidential candidacy from Army Chief Sisi.

- February 16, 2014: Several people are killed in an explosion in an attack on a tourist bus on the Sinai near the Israeli border. Mursi is being tried in an espionage case in which allegations in the trial relate to the deaths of at least 10 people who attended rallies outside the presidential palace in December 2012.

- February 19, 2014: Mubarak and his two sons are charged again with corruption allegedly wasting millions of dollars in public money renovating presidential palaces.

- February 22, 2014: Six police officers were acquitted of charges of killing 83 protesters during the 2011 uprising.

- 24./25. February 2014: On February 24, 2014, the Beblawi cabinet submitted its resignation to interim president Adli Mansur, which was accepted the following day. To the on Hazem Al Beblawi following, designated cabinet chief is Ibrahim Mahlab made, which is entrusted with the formation of a successor government.

- February 26, 2014: A court sentenced 26 people to death convicted of attacking ships as a "terrorist group" while they were crossing the Suez Canal.

- February 27, 2014: 21 students from Al-Azhar University in Cairo are sentenced by a Cairo court to three years' imprisonment each for illegal pro-Mursi demonstrations on the university campus, which occurred in late 2013.

- The Sisis Military Government / Transitional Government

- Presidency of Mansur - Mahlab's cabinet:

- March 1, 2014: Official swearing-in of a new cabinet under Prime Minister Ibrahim Mahlab.

- March 4, 2014: The Palestinian Hamas group, which is active near the Gaza Strip, is legally banned from all activities in Egypt, its property is confiscated and its offices are ordered to close.

- March 22, 2014: More than 1,200 people are brought to justice as supporters of Mursi.

- March 24, 2014: An Egyptian criminal court sentenced 529 people to death after a single session of a mass trial that the court found guilty of killing a police officer during the riots in Minya city in the summer of 2013 that followed Morsi's fall. Legal experts call the case the largest mass litigation in Egypt's recent history. Another court is continuing the trial in Cairo of several Al Jazeera journalists who are accused of misreporting the riots in Egypt as part of a conspiracy to overthrow the new government.

- March 26, 2014: General Sisi, who had previously given himself the title of Field Marshal, officially declares that he is retiring from the army and running for president. It is almost universally expected that he will win the election and give formal form to his current de facto power.

- The Sobhis Military Government / Transitional Government

- Presidency of Mansur - Mahlab's cabinet:

- March 27, 2014: Sisi's successor at the top of the army and as defense minister will take over as Chief of Staff Sidki Sobhi , who will be sworn in for both offices on March 27.

- March 28, 2014: Four people, including the Egyptian journalist Mayada Ashraf, are killed in Cairo during police “clashes” with demonstrators protesting against the presidential candidacy of the former army chief Sisis.

- March 30, 2014: The Election Commission announced May 26th and 27th as the date for holding presidential elections.

- April 3, 2014: Former President Mubarak declares his support for Sisi's presidential candidacy, describes Sisi as the “best” candidate and describes his challenger, Hamdin Sabahi, as “useless”.

- April 28, 2014: In the largest mass trial in Egyptian history, 683 people are sentenced to death by a court in Minya, including leading members of the Muslim Brotherhood such as its chairman, Mohammed Badie.

- May 3, 2014: Start of the presidential campaign campaign.

- May 21, 2014: A criminal court sentenced Husni Mubarak, who lived in a military prison, to three years in prison for embezzling millions of dollars in public funds for private use in private homes and palaces. His sons Gamal and Alaa each received a four-year sentence for their role in embezzlement. According to lawyers, the current interim prime minister and the espionage chief could also be involved in the case.

- 26./27. May 2014: Start of the originally two-day presidential election vote, the winner of which is generally expected to be former army chief Sisi against the only challenger Hamdin Sabahi.

- May 28, 2014: The vote is extended by one day in an attempt to increase the low turnout, which threatens to undermine the credibility of the election, the likely winner of which is former Army Chief Sisi.

- May 30, 2014: Former army chief Sisi wins the presidential election in what was described as a "landslide" victory by gaining over 90 percent of the vote. His only challenger, Hamdin Sabahi, only receives 3 percent of the vote. He admits defeat after declaring that the vote was unfair.

- June 3, 2014: The electoral commission declares Sisi the next Egyptian president and states that he received 96.91 percent of the valid votes in the presidential election.

- June 6, 2014: The outgoing interim president, Adli Mansur, issued a decree declaring sexual harassment a criminal offense in Egypt, punishable by up to five years in prison.

- June 8, 2014: General Abd al-Fattah as-Sisi, who had previously awarded himself the title of field marshal and had led the military's takeover almost a year earlier, is sworn in as president of the constitutional court. Previously, he had won the “ pro forma presidential election” (New York Times) with almost 97 percent of the votes cast. The turnout of 47 percent of the electorate was far lower than he had aimed for as a mandate for leadership and was below the turnout of 52 percent in the 2012 election, which was won by Mohammed Morsi, who was ousted by Sisi in 2013. According to foreign observers, the election won by Sisi did not meet international standards.

- June 9, 2014: Resignation of the military-backed transitional government. Interim head of government Ibrahim Mahlab said after his resignation that the new head of state Sisi should be given the opportunity to put together a cabinet of his confidence.

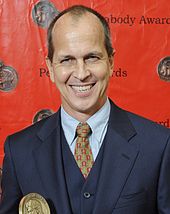

- June 23, 2014: After a month-long trial of four accused foreigners and 16 Egyptians in Cairo, three journalists from Al Jazeera's English-speaking service , Mohammed Fahmy , Peter Greste and Baher Mohammed , are sentenced to long prison terms by an Egyptian court. The court found the convicts guilty of "supporting a terrorist organization" or conspiracy with the Muslim Brotherhood and of "spreading false news" about civil unrest in Egypt. The convictions come one day after US Secretary of State John Kerry's visit to Cairo, during which Kerry said that President Sisi had given him “a very strong sense of his commitment” to “a reassessment of human rights law”. The court judgments later condemned in the western media as “arbitrary judgments” in “show trials” (Die Zeit) are commented on by the New York Times as “a potentially embarrassing turnaround for the US government”. Kerry later called the sentence "creepy" and "draconian", the UN Human Rights Commissioner Navi Pillay criticized the Egyptian judicial practice as "disgusting". In July 2014, Sisi will finally admit for the first time that the judgment was a mistake and that it had seriously damaged Egypt's international reputation.

Interim reports on the development of the crisis and the death toll

The ruthless repression of the military-backed transitional government since the military coup of July 3 did not lead to a stabilization, but to a destabilization of the situation in Egypt (as of early April 2014). The country was considered bankrupt, almost ungovernable and increasingly insecure. In a hotspot ranking as the indicator assessments of political risks (security and stability) of the country analysis company Economist Intelligence Unit were taken over, Egypt is in the first half of 2014, together with Kosovo , Libya , Syria , the Lebanon and the Ukraine to the six countries in the neighborhood of the European Union whose situation is classified as very risky.

| Cause of deaths | January to June 2013 (during Morsi's presidency) |

July to December 2013 (during Mansur's interim presidency) |

|---|---|---|

| Political disputes | 153 | 2273 |

| Denominational disputes | 29 | 32 |

| Violence in detention centers | 24 | 62 |

| Terrorist attacks | 4th | 200 (including 36 civilians) |

A comparison of the development of violence shows a drastic increase after the military coup in 2013. According to the website Wiki Thawra (also "Wiki Thaura"), whose statistics a group of 14 human rights groups referred to in early January 2014, lost in 2011, at 18 days Uprising against Mubarak, 1075 people lost their lives. During Mohammed Morsi's one-year term in office, there were a total of 470 victims. By contrast, since Morsi was overthrown on July 3, 2013, 2,665 people were killed by the end of 2013 alone, over 1,000 of them in the bloody evacuation of the two Pro Mursi protest camps on August 14, 2013 in Cairo.

The biggest death toll within a single day since the start of the popular uprising in 2011 was the break-up of two pro-Morsi protest camps on August 14, 2013 by the military-backed transitional government, which according to official figures, had at least 650 civilians, called the “Rābiʿa massacre” by various human rights organizations were killed. Both before and after the breaking up of the Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya sit-in , further serious human rights violations occurred in 2013.

In their 195-page report, "All According to Plan - The Rab'a Massacre and Mass Killings of Protesters in Egypt," published on August 12, 2014 after more than a year of research, Human Rights Watch counted six extrajudicial mass executions by the Egyptian security forces for that period alone July and August 2013 and came to the conclusion that the "systematic, large-scale killings of at least 1,150 demonstrators by Egyptian security forces in July and August 2013" are likely crimes against humanity . In the evacuation of the protest camp in Rabaa-al-Adawija Square on August 14, Human Rights Watch said, "the security forces calculated several thousand deaths and, without a doubt, killed 817, probably at least 1,000 people." According to Kenneth Roth, Executive Director of Human Rights Watch , the Egyptian security forces "committed one of the most brutal mass executions of demonstrators in recent world history in one day in Rabaa Square."

| date | Place of the main event | Participating forces | Casualty (civil) | Fatalities (emergency services) | Human Rights Watch data as of August 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th July 2013 | In front of the headquarters of the Republican Guard in Cairo | military | 5 protesters | - | Extrajudicial mass execution. One of the people executed had only tried to put a Mursi poster on a fence outside the headquarters. There are video recordings of the execution. |

| July 8, 2013 | In front of the headquarters of the Republican Guard in Cairo | military | 61 protesters | 1 soldier, 1 policeman | Extrajudicial mass execution. Police and soldiers opened fire on a group of Mursi supporters who were demonstrating peacefully in front of the headquarters. Two police officers and at least 61 protesters were killed. |

| July 27, 2013 | Nasr Street in Cairo | police | 95 demonstrators | 1 policeman | Extrajudicial mass execution. Police attacked a demonstration by Morsi supporters near the Manassa monument in eastern Cairo, killing at least 95 people. A police officer died in the clashes. |

| August 14, 2013 | Muslim Brotherhood sit-ins on Nahda and Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya Squares in Cairo | police | Up to 1000 demonstrators (according to interim Prime Minister Hasim al-Beblawi) | 9 policemen | Extrajudicial mass executions. Security forces evacuated the protest camps in Rābiʿa Square and Nahda Square and killed at least 817 people, probably at least 1,000 people in Rābiʿa Square and at least 87 people in Nahda Square. Eight police officers died in the clashes in Rābiʿa Square and two in Nahda Square. |

| August 16, 2013 | Clashes at the center of the protests in Ramses Square in Cairo and on the protest marches to the square | police | At least 120 people | 2 policemen | Extrajudicial mass execution. Police shot hundreds of protesters near Ramses Square in central Cairo, killing at least 120 people. Two policemen died. |

| October 6, 2013 | Dissolution of the marches from Dokki and Ramses Square to Tahrir Square in Cairo | Police and military | At least 57 protesters | - |

| Cause of deaths | Civilians | police officers | soldiers | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demonstrations and clashes | 2528 | 59 | 1 | 2588 |

| terrorism | 57 | 150 | 74 | 281 |

| Other acts of violence | 274 |

While the number of people killed by the coup in July 2013 to early March 2014 rose to 3,000, according to human rights organizations, that of the injured to 16,000 and that of the arrested to 22,000, the ruthless action of the security forces did not stop the growing wave of protests in the country demanded the restoration of democracy, accused the military-dominated regime of reestablishing a police state with police brutality, mass imprisonment and torture and, according to observers, felt provoked to counter violence.

In the first eight months since the military overthrew President Morsi, Egyptians suffered the highest intensity of human rights violations and terrorism in their recent history. The extent of the violence has been largely masked due to the lack of reliable data, but estimates suggest that more than 2,500 Egyptians have been killed, over 17,000 wounded and more than 16,000 arrested in demonstrations and clashes since the military coup on July 3, 2013 (as of end of March 2014). In addition, hundreds were killed in terrorist attacks. These numbers exceeded even Egypt's darkest period in terms of human rights violations since the military coup in Egypt in 1952, and reflect an unprecedented use of violence in Egypt's recent political history. In the 1950s, the number of political prisoners under Gamal Abdel Nasser had at times assumed similar dimensions, but the police repression against street protests at that time hardly claimed any victims.

The number of people arrested by the police since the fall of Morsi rose according to data from Wiki Thawra or according to the count of the "Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights" (ECESR) until May 15, 2014, a good ten months after Coup, to over 41,000. The website, which is considered to be independent, only evaluated arrests that took place under the responsibility of the transitional government of the former military chief and later Egyptian President Sisi. The figures are aggregated data from several independent non-governmental organizations such as the ECESR. The report only evaluated arrests made on charges of political, social or “denominational” activities or “terrorist acts”. On the massacre of Rābiʿa-al-ʿAdawiyya in mid-August 2013, for which Sisi was responsible, in which, according to human rights activists, more than 900 demonstrators were killed by security forces - most of them with targeted shots in the head, neck, heart or thighs - and that of Amnesty International rated “the most serious unlawful mass killings in the modern history of Egypt”, followed by a growing wave of terrorism by jihadist groups close to al-Qaeda, killing over 500 police officers and soldiers within ten months.

Democracy / autocracy rating for the period before and after the coup

In the months preceding the July 3, 2013 military coup, many Egyptian and Western analysts claimed that Morsi's one-year term in office had been manifestly “undemocratic”. Morsi was described with terms such as "new pharaoh", "budding dictator" or as a pioneer for a new, dangerous form of "fascism". A study of the reign of Mohammed Morsi by the US Middle East experts Shadi Hamdi and Meredith Wheeler from the Brookings Institution , who used the popular Polity IV index with parameters of democracy customary in political science for the development of transition societies after the fall autocratic regime, on the other hand, resulted in the finding that in a global comparison, despite mistakes caused by presumptuousness and incompetence, Morsi had an average record, i.e. Egypt was not placed in the lower range on the scale between democracy and autocracy during his tenure . While Egypt under Morsi showed average values of the democracy measurement compared to other countries that went through a “positive regime change” or a “democratic transition”, according to the experts it cut in the more relevant comparison with other countries that had a “social Transition process ”, during which not only elites but also ordinary citizens got into political and social turmoil, were significantly more positive than the average. Morsi had proven to be an incompetent politician, but he was not responsible for serious human rights violations or systematic repression and imprisonment of the opposition. The military coup was therefore legitimized “by a fundamental misinterpretation and distortion of what happened before”.

For the transitional government that the military installed after the military coup of July 3, 2013, Hamdi and Wheeler used the same procedure to determine that the new regime would operate in the months after the coup on the Polity IV, which ranges from +10 to −10. Index scale compared to Morsi's reign by six full points and, in the event of the widely expected official consolidation of Sisi's power, fell by eight points in the direction of autocracy. Unlike Morsi, and even in contrast to Husni Mubarak and Anwar as-Sadat , the post-coup military government under Sisi presided over both mass arrests of political opponents and mass killings such as the crackdown on the pro-Morsi protest camps on August 14, 2013 , in which at least hundreds died. In addition, there was a law effectively preventing oppositional demonstrations and the continued use of deadly force against demonstrators by the security forces. After the coup, political competition was only tolerated within the regime's own political coalition. The development of Egypt towards autocracy in the months after the coup was seen by analysts as a typical and predictable development of a country after a military coup. In view of the particular peculiarity of the ideological split in Egypt, the international toleration and downright support for the coup, as well as the pronounced anti-Muslim Brotherhood mood of a significant part of the population, the fall of Morsi deviated from the usual and led into a more repressive phase than it did the majority of modern coups are the case, making the situation in Egypt comparable to that of Chile and Argentina in the 1970s or that of Algeria in the 1990s.

Power political actors

In the western perspective, the political power struggle in Egypt was often understood as a confrontation between one camp that was determined to establish a dictatorship , while the other camp was fighting for “ freedom ” and “ democracy ”. However, even before the military coup against President Mohammed Morsi, political scientists such as Nagwan El Ashwal from the Science and Politics Foundation (SWP) were of the opinion that all politically relevant Egyptian parties acted in a way that was unsuitable to avert a state crisis in Egypt. Political and Islamic scholar Loay Mudhoon, Middle East expert at Deutsche Welle, took the view that the question of identity about the secular, liberal or Islamic orientation of the Islamic countries in question was not a real but a one in the revolutionary wave subsumed in the West as the “Arab Spring” constructed subject of dispute. Islamists have put the question of identity on the agenda to distract from their economic and political ineptitude. In fact, it was mainly about "bread, freedom and social justice", which are summarized in Arabic as "Karama" (German: "dignity"). The citizens would have asked for their point of view to be taken into account politically by the elites, who since the era of the post-colonial military dictatorships had the privilege of sole control of politics.

While Islamist groups initially benefited most from the collapse of the Mubarak regime, many Egyptian and international observers saw the danger of an “Islamization of Egypt” or in the fundamental social and political development processes that were initiated after the political upheaval called the revolution in Egypt an "Islamist counter-revolution". It was often overlooked that after the fall of Mubarak, the leitmotif of those who were attributed to Islamism was political pragmatism and that no closed group of “Islamists” existed. In Egypt in particular, the spectrum of Islamist actors was very heterogeneous. The Islamist organizations and groups were busy agreeing on their political agendas and developing party structures. They were also subject to a large number of restrictions in their political approach and had to assert themselves against other political forces and state and semi-state institutions.

military

The leadership of the Egyptian military is social and very homogeneous in terms of their background. Some families have been employed in the military for decades and have occupied the officer ranks there as a separate “political class” since the time of Gamal Abdel Nasser , for example at the level from middle to upper middle class. The attitudes and attitudes of the lower ranks and those doing military service have not been researched, but dissent within the military is severely punished.

From 1981 until the revolution of 2011 , Egypt was ruled by Hosni Mubarak . His predecessor Anwar as-Sadat was assassinated in Cairo in 1981 after he signed the Camp David Agreement brokered by US President Jimmy Carter in 1978 . In 1979, the agreement led to the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel and later to the withdrawal of Israeli troops from the Sinai Peninsula and brought Sadat the Nobel Peace Prize in 1978 and Egypt initially brought about political isolation within the Arab states. Mubarak ruled Egypt for 30 years in an authoritarian manner and in a permanent state of emergency as a country marked by corruption , unemployment and poverty, backed by constant financial support from the USA alone of 1.3 billion dollars in military aid. Votes were manipulated, critics of the regime were tortured and murdered by the state security, companies and associations paid homage to Mubarak in the style of leader cult, around 2,500 employees of the US embassy , some of whom worked for the US intelligence service CIA , exerted political influence over the country, while Western democracies always the regime again certified progress in "political reforms" until Mubarak was overthrown on February 11, 2011 with the participation of mass uprisings.

After Mubarak's fall, the ruling structure, often personalized as the “Mubarak System”, turned out to be military rule that allowed Mubarak or his family to act as long as it was beneficial to the generals' own interests. In the Egyptian system, the boundaries between the military, politics and economics blended into one another or were often nonexistent. The military was intertwined with politics, justice, economy and administration to form a "deep state". The state institutions were controlled and abused by these powerful groups of actors, for whom the focus was not on the common good but on maximizing the profits of the groups themselves.

After the fall of Mubarak, the military took over or retained power in the form of military rule, but did not pursue the “goals of the revolution” as emerged in the mass protests against Mubarak, whereupon the street protests soon turned against the military. At the time, the protest movement accused the military of authoritarian governance, a desolate economic and social situation and “theft” of the revolution, similar to what it did in 2013 against Morsi's government, which in turn was put into a coup by the military supported by the protest movement.