Summertime

When DST opposite is time zone usually presented by one hour time indicated that during a certain period in the summer months (and slightly beyond and often) as the legal time is used. Such a regulation is used almost exclusively in countries in the temperate zones .

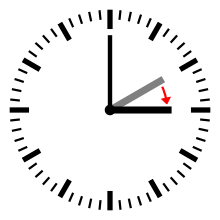

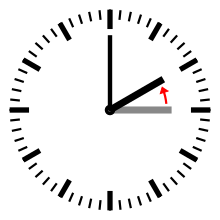

Central European summer time begins on the last Sunday in March at 2:00 a.m. CET , with the hour count being advanced by one hour from 2:00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m. It ends on the last Sunday in October at 3:00 a.m. CEST by setting the hour count back one hour from 3:00 a.m. to 2:00 a.m.

Basics

The local solar time , which is defined by the hour angle of the sun , has served as the time system for everyday use since ancient times . This means that it is 12:00 noon (time of the highest position of the sun ) and 12:00 a.m. at midnight . In order to eliminate the location dependency of time - a geographical longitude difference of one degree corresponds to a time difference of 4 minutes - within a country , a global system of 24 time zones with an east-west was established at the international meridian conference of 1884, based on the Greenwich prime meridian -Extension of about 15 ° geographic difference in length created. Each time zone was assigned a zone time which (according to the definition at the time ) was equal to the mean solar time of the mean meridian of the zone with the geographical longitudes 0 °, 15 °, 30 °, ... east and west of Greenwich. The zone times of two adjacent zones differ by exactly one hour. A zone time expires uniformly and is uniform within the countries in the same time zone. If these conditions are observed, it deviates as little as possible from the local solar time. The difference between the local solar time and the zonal time of a place is negative east of the central meridian and positive west of it, and if the boundaries of the time zones roughly coincide with their natural position - which is often no longer the case today - the amount of this difference is the annual mean nowhere much longer than half an hour.

The legal times of the individual countries are defined as the zone time of the time zone to which the country belongs according to its geographical longitude . So which is Central European Time (CET), the time zone in the Central European time zone with the reference meridian of longitude 15 degrees East. It differs from the Coordinated Universal Time UTC , which is related to the Greenwich Prime Meridian, by 1 hour: CET = UTC + 1 hour.

Due to economic and political considerations one of these was repeated in many countries each for limited periods during the summer months normal legal time by an hour prior DST introduced as legal time. The summer time is thus the same as the zone time of the time zone adjacent to the east, i.e. about Central European Summer Time (CEST) = UTC + 2 hours (= Eastern European Time (EET)). The difference between the local solar time and the legal time increases by one hour with the introduction of summer time. The first and second world wars and the oil price crisis in the 1970s were reasons for the introduction of summer time . Similarly, in the winter of 1946/47 in Czechoslovakia there was a winter time to save energy in the morning, i.e. , in reverse to summer time, the legal time was set back by one hour compared to the normal legal time (CET).

To distinguish it from daylight saving time, the zone time , which is normally used as legal time, is called normal time or standard time . Since summer time has been introduced every year in many European countries since around 1980 and normal time was therefore only used in the winter half-year, the term winter time has also become commonplace.

history

Benjamin Franklin stated in the Journal de Paris in 1784 that the extensive nightlife wastes energy through artificial light. On the other hand, getting up and going to bed earlier helps. The idea of a state-mandated summer time came up at the end of the 19th century. Independently of each other, George Vernon Hudson in 1895 and William Willett in 1907 proposed a seasonal time shift. The entomologist George Vernon Hudson first presented his idea in a lecture to the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1895 . Neither his lecture nor the publication of his ideas three years later met with approval, so that he was soon forgotten.

Due to practical difficulties such. B. In the case of cross-border rail traffic, it is no coincidence that the first introduction of summer time falls during the First World War :

“The idea of better adapting the way of life during the summer months or during the period of validity of the summer timetable to the time of daylight has so far not gained any validity because of the great difficulties involved in a uniform approach by the countries involved in European rail transit traffic. With the outbreak of the great war, these difficulties for the Central European countries were essentially eliminated, while the need to save fuel and lighting materials by making the greatest possible use of sunlight was asserted more than usual. The railroad traffic to the hostile states was completely interrupted by the war. Even after the neutral states, the passage of passenger cars had to be restricted or completely stopped in consideration of the surveillance of border traffic, which is necessary for military reasons. "

The time change was first introduced on April 30, 1916 in the German Empire and Austria-Hungary . The summertime should support the energy-intensive " material battles " of the First World War: This promised to save energy with artificial lighting on long summer evenings. In response, numerous other European countries, including the warring Great Britain and France , introduced daylight saving time in the same year. In 1919, Germany abolished the unpopular war measure during the Weimar Republic .

Great Britain was the only country that continuously persisted in shifting the hours in summer between the two world wars. France also continued daylight saving time, but ended it due to protests by farmers in 1922. In 1923 it was reintroduced. Other countries only experimented with daylight saving time for a short period of time, Greece only for two months in 1932. In Canada and the United States , daylight saving time was regulated regionally or locally rather than nationally, which resulted in different times being used within a city. The Soviet Union put the clocks one hour forward in 1930, but not back again.

In 1940 , during World War II , Germany reintroduced summer time in anticipation of energy savings. The clocks in the occupied and annexed areas were also synchronized with Berlin . At the end of the war, the Allied Control Council in Germany agreed on a uniform clock changeover during the warm season. From May 11th, 1947, a double daylight saving time was introduced. H. a deviation of two hours, prescribed in order to make maximum use of daylight. Seven weeks later (June 29th), simple daylight saving time was reverted to. In 1949 , the year the two German states were founded, an agreement was reached between the Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR to end the annual clock change. In the other countries, summer time was also on the decline after World War II.

The 1973 oil price crisis hit Europe hard. Due to high energy prices, Europe fell into a recession and had to save. But only one Western European country introduced summer time to save energy: France in 1976. For all other member states of the European Community , the integration and harmonization of the common internal market was the driving force behind the reintroduction of summer time. MEP Liesel Hartenstein had already summed up the advantages during the time law debate in the Bundestag in 1977: “The simplification in cross-border traffic, the harmonization of timetables and flight schedules, [...] speaks for it. It is [...] about the question of uniformity in the European Community and ultimately [...] about European integration. ”Although other states of the European Community followed after France, the Federal Republic of Germany hesitated. One did not want to divide Germany additionally in terms of time. The GDR did not comment on the issue. In 1979, the GDR surprisingly announced the introduction of summer time for the following year. By ordinance, it came into effect in both German states from 1980. Many neighboring countries, which had previously acted with wait and see, have now followed suit. As the last country in the middle of Europe, Switzerland joined the summer time in 1981.

By 1996, the different summer time regulations in the European Union were standardized. Since then, the uniform summer time has been in force in all EU member states, including their parts of the country near Europe, from the last Sunday in March at 2:00 a.m.CEST (3:00 a.m.CEST) to the last Sunday in October at 3:00 a.m.CEST (2:00 a.m. CET). However, those parts of the country that are not on the territory of the European continent itself, such as French Guiana, are excluded .

Germany

In the German Empire there was a summer time for the first time during the First World War in the years 1916 to 1918:

| year | Beginning of summer time | End of summer time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1916 (a) | Sunday April 30, 1916 | 23:00 CET | Sunday October 1, 1916 | 1:00 CEST |

| 1917 | Monday April 16, 1917 | 2:00 CET | Monday, September 17, 1917 | 3:00 CEST |

| 1918 | Monday April 15, 1918 | 2:00 CET | Monday, September 16, 1918 | 3:00 CEST |

- a The provision for the first introduction read: “May 1, 1916 begins on April 30, 1916 at 11 o'clock in the afternoon according to the current calendar. September 30, 1916 ends one hour after midnight within the meaning of this ordinance. "

There was no time change between 1919 and 1939. Summer time was reintroduced in 1940, the year of the war . Originally it was supposed to end on October 6, 1940, but this was suspended four days before it expired: "The [...] by ordinance [...] will remain in place until further notice."

However, summer time was interrupted three times from 1942 onwards by so-called “ordinances on the reintroduction of normal time”. Thus, in the war years there were periods that did not follow a clear pattern:

| year | Beginning of summer time | End of summer time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940–1942 (a) | Monday April 1, 1940 | 2:00 CET | Monday November 2, 1942 | 3:00 CEST |

| 1943 | Monday March 29, 1943 | 2:00 CET | Monday 4th October 1943 | 3:00 CEST |

| 1944 | Monday April 3, 1944 | 2:00 CET | Monday October 2, 1944 | 3:00 CEST |

| 1945 | Monday April 2, 1945 | 2:00 CET | (b) | |

- a In 1940 and 1941 there was no change back to CET following the enactment of the “Ordinance on the Extension of Summer Time”; the summer time therefore applied continuously from April 1940 to November 1942.

- b In the ordinance of 1944 an end was not determined. After the end of the war, the legal time in Germany was set by the occupying powers.

In 1945, immediately after the war, and in the following years, the occupying powers determined the annual changeover to summer time. There was the Central European Midsummer Time (MEHSZ) as well as separate regulations for the Soviet occupation zone and Berlin. The post-war regulations are shown below:

| year | Beginning of summer time | End of summer time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 ( western zones ) | Sunday September 16, 1945 | 2:00 CEST | ||

| 1945 ( Soviet Zone , Berlin) | Sunday November 18, 1945 | 3:00 CEST (a) | ||

| Thursday May 24, 1945 | 2:00 CEST | Monday, September 24, 1945 | 3:00 CET (b) | |

| 1946 | Sunday April 14, 1946 | 2:00 CET | Monday, October 7, 1946 | 3:00 CEST |

| 1947 | Sunday April 6, 1947 | 3:00 CET | Sunday October 5, 1947 | 3:00 CEST |

| Sunday May 11, 1947 | 3:00 CEST | Sunday June 29, 1947 | 3:00 CET (c) | |

| 1948 | Sunday April 18, 1948 | 2:00 CET | Sunday 3rd October 1948 | 3:00 CEST |

| 1949 | Sunday April 10, 1949 | 2:00 CET | Sunday October 2, 1949 | 3:00 CEST |

- a In the Soviet occupation zone and Berlin , summer time in 1945 lasted two months longer than in the rest of Germany.

- b In the Soviet occupation zone and Berlin, Central European high summer time (MEHSZ; so-called "double summer time") was in effect from May 24, 1945 to September 24, 1945, which coincided with the then valid Moscow time UTC + 3, with a time difference of plus two hours to CET; after the end of this period, CEST continued until November 18, 1945.

- c Between May 11 and June 29, 1947, the MEHSZ was in effect throughout Germany.

The summer time regulations at that time ended in 1949. From 1950 to 1979 there was no summer time in Germany.

The renewed introduction of summer time was decided in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1978, but did not come into force until 1980. On the one hand, they wanted to adapt the time change to the neighboring countries to the west, which had already introduced summer time in 1977 as an aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis for reasons of energy policy . On the other hand, an agreement had to be reached with the GDR on the introduction of summer time so that Germany and Berlin in particular were not divided in time. The Federal Republic of Germany, with the exception of the Büsingen exclave on the Upper Rhine , and the GDR therefore introduced summer time at the same time. Büsingen oriented itself towards Switzerland and did not introduce summer time until 1981.

In the GDR, the time system regulated the changeover in conjunction with the ordinance on the introduction of summer time valid for the respective year (for the first time that of January 31, 1980). How politically charged the topic was in the situation at the time became clear in the fall of 1980 when the GDR suddenly announced that it wanted to abolish summer time after the first year. This plan caused a certain turbulence (it was understood in the Federal Republic of Germany as a demarcation from the West ), although in the end the agreed approach was retained.

In 1981 the start was brought forward. Finally, in 1996, the different summer time regulations in the European Union were standardized. This means that summer time in Germany is one month longer; since then it has lasted 30 or 31 weeks.

| year | Beginning of summer time | End of summer time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Sunday April 6, 1980 | 2:00 CET | Sunday 28th September 1980 | 3:00 CEST |

| 1981-1995 | last Sunday in March | 2:00 CET | last Sunday in September | 3:00 CEST |

| since 1996 | last Sunday in March | 2:00 CET | last Sunday in October | 3:00 CEST |

Austria

Daylight saving time was introduced in Austria-Hungary in 1916. It was valid in Austria until 1920, with the exception of 1919, and in Hungary until 1919. The legal basis until 1920 was the authorization of the government to make economic decisions based on the state of war ( Cisleithanien : RGBl. 274/1914, RGBl. 307/1917 ; Bosnia and Herzegovina : GVBl. 167/1914).

The national legislation was carried out separately for Cisleithanien, Transleithanien and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which belongs to both. While all of the Cisleithan crown lands referred to the Reichsgesetzblatt, provided that they published the resolution for summer time in the Landesgesetzblatt and added an implementation instruction, this was not the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In 1918 the date of introduction was changed at short notice. First, on March 7th, it was decided to introduce summer time, but with a different start and end than in Germany (start on the first Monday of April and end on the last Monday of September); shortly thereafter the period was adjusted to that of the allied Germans (DE: resolution: March 7th; Cisleithanien: resolution: March 7th, edition: March 9th, change: March 25th, edition: March 26th; Bosnia and the Hercegovina: B: March 19, A: March 22, A: March 26, A: March 28). In 1919 the decision to introduce summer time was withdrawn after nine days; the change was issued two days before the planned start.

In 1920 summer time began as planned. On April 28, the Salzburg state parliament decided to refrain from summer time from May 1; the issue took place two days before the date. The state railways continued to operate in Salzburg after summer time.

| year | Beginning of summer time | End of summer time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1916

(a) (like DE) |

Sunday April 30th | 23:00 CET | Sunday October 1st | 1:00 CEST |

| 1917 (like DE) | Monday April 16 | 2:00 CET | Monday 17th September | 3:00 CEST |

| 1918 actually planned (like DE) |

Monday April 15th |

2:00 CET |

Monday September 16th |

3:00 CEST |

| 1919 canceled |

|

|

|

|

| 1920 1920 - Salzburg |

Monday April 5th | 2:00 CET | Monday September 13th, Saturday May 1st |

3:00 CEST 1:00 CEST |

- a The provision for the initial introduction read: “For the period from May 1 to September 30, 1916, a special calendar (summer time) will be introduced. According to this, May 1st, 1916 begins on April 30th at 11 o'clock in the evening of the previous time calculation, September 30th ends 1 hour after midnight of the time calculation specified in this ordinance. "

After the Anschluss , the same regulations applied in Austria from 1940 as in the rest of the German Reich (Berlin period) . With the arrival of the Allies in 1945, many National Socialist regulations were reversed. After the war there was a summer time in Austria up to and including 1948, whereby the orientation was based on West Germany, but no midsummer time was introduced.

| year | Beginning of summer time | End of summer time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | Monday April 2nd | 2:00 CET | in Vienna April 12, elsewhere at the latest April 23 |

|

| 1946 (like DE) | Sunday April 14th | 2:00 CET | Monday October 7th | 3:00 CEST |

| 1947 (like DE, without MEHSZ) | Sunday April 6th | 2:00 CET | Sunday 5th October | 3:00 CEST |

| 1948 (like W-DE) | Sunday April 18th | 2:00 CET | Sunday 3rd October | 3:00 CEST |

In 1976, the Time Counting Act created the basis for the government to reintroduce summer time by ordinance . The reasons for the introduction could be the saving of energy and the coordination with other countries. Daylight saving time has to be between March 1st and October 31st and start and end on a Saturday or Sunday. At that time it was determined that the clocks would be set back at the beginning of 0:00 to 1:00 a.m. and at the end of 24:00 to 23:00.

In 1981 this precise definition was repealed and left to regulation. As since 1917, when you finish, the first of the double hour is to be designated as "A" and the second as "B".

In 1980, as in Germany, summer time was reintroduced for the period from March to September. The respective EU directive has been implemented since 1995 , and in 1996 summer time was extended to the end of October, as in the entire EU.

| year | Beginning of summer time | End of summer time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 (a) | Sunday April 6th | 0:00 CET | Saturday September 27th | 24:00 CEST |

| 1981-1995 | last Sunday in March | 2:00 CET | last Sunday in September | 3:00 CEST |

| since 1996 | last Sunday in March | 2:00 CET | last Sunday in October | 3:00 CEST |

- a The first version of the Time Counting Act stipulated: “Section 2 (4) Daylight saving time must begin on a Saturday or Sunday. On this day, the clocks are put forward from 0:00 to 1:00. // (5) Daylight saving time must be ended on a Saturday or Sunday. On this day, the hour from 23:00 to 24:00 is to be counted twice. The first of these double-appearing hours is to be designated as 23 A, 23 A 1 minute etc. to 23 A 59 minutes, the second as 23 B, 23 B 1 minute etc. to 23 B 59 minutes. ”The 1979 ordinance stipulated: "In the 1980 calendar year, daylight saving time begins on Sunday, April 6, 1980, at midnight and ends on Saturday, September 27, 1980, at midnight."

Switzerland

In Switzerland in 1941 and 1942, summer time was in effect from the beginning of May to the beginning of October. In 1977 a law passed the introduction of daylight saving time at the same time as the neighboring states. Above all, the peasants resisted this; signatures were collected for a referendum , and in the referendum on May 28, 1978, the daylight saving time law was clearly rejected.

Since Switzerland and the German enclave Büsingen were now a "CET time island" in the midst of countries with summer time in the summer of 1980, Parliament passed the government- required time law of March 21, 1980, on the basis of which the following year summer time as in was introduced in neighboring countries. After being passed by parliament, the law was again subject to an optional referendum . However, the 50,000 signatures required for a referendum could no longer be obtained. The law came into force on January 1, 1981. A repetition of the chaos of time that arose in 1980, z. B. on cross-border railway timetables, avoided.

A popular initiative launched in 1982 (by Christoph Blocher, among others ) to abolish summer time did not materialize. Since 1981 the same daylight saving time regulation has been in effect in Switzerland as in its neighboring countries: from 1981 to 1995 from the end of March to the end of September, since 1996 from the end of March to the end of October, with the changeover every Sunday at 2:00 a.m. UTC). Later political attempts to abolish summer time failed, for example on September 10, 2012, a motion in the National Council by Yvette Estermann with 143 to 23 votes. The clear reason given by the Federal Council was that summer time was not introduced for energy-saving or similar reasons, but "in order to be able to match the time regulations in our country with those of neighboring countries."

Italy

In Italy , the clocks were first put forward by one hour on May 25, 1916, during the war, which remained in use until 1920. Between 1940 and 1948 different time changes were made several times due to the war. The longest time in a row was from June 17, 1940 to November 2, 1942. During the time of the Italian Social Republic , the same time sometimes did not apply throughout the country. The time change in Trieste was also prohibited by the Yugoslav occupying forces.

From 1965, the possibility of summer time changeover for times of energy crisis was provided for by law, which was used for the first time in 1966, and so there was a one-hour time difference that year from May 22nd to September 24th. Summer time had to be confirmed annually by the government, which remained so until 1979. The clocks were changed at midnight . The law stipulated the period starting from March 31st to June 10th and ending from September 20th to October 31st. In order to change the clocks in 1980 at the same time as the other European countries, the law was amended by decree and the start was made possible on March 28th. Two years later, the earliest point in time to start was set on March 15, in order to be able to comply with the EC regulation without any further changes to the law.

France

As a result of the 1973 oil crisis, the “heure d'été” was (re) introduced in France on March 28, 1976. The period was set to the period from the last weekend in March to the last weekend in September. From 1976 to 1979, France was the only country with summer time in Central Europe during the months of April and May, as Italy did not change over until the end of May. In the summer months from June to September, both countries had the same time again.

Summer time regulations

Common European summer time

| violet |

Azores ( UTC − 1 ) Azores, daylight saving time ( UTC ± 0 ) |

| Light Blue | Western European Time ( UTC ± 0 ) |

| blue |

Western European Time ( UTC ± 0 ) Western European Summer Time ( UTC + 1 ) |

| red |

Central European Time ( UTC + 1 ) Central European Summer Time ( UTC + 2 ) |

| yellow | Kaliningrad Time ( UTC + 2 ) |

| ocher |

Eastern European Time ( UTC + 2 ) Eastern European Summer Time ( UTC + 3 ) |

| light green | Moscow time ( UTC + 3 ) |

The European summer times ( WEST , CEST , OESZ ) are regulated for the EU in Directive 2000/84 / EC on the regulation of summer time and the supplementary communications 2001 / C 35/07 and 2006 / C 61/02.

Some associated countries, such as Switzerland, the European Economic Area except Iceland, and some other countries also use this regulation. The daylight saving time procedure was confirmed in 2007.

After the 1973 oil crisis , France was the only country in Central Europe to reintroduce summer time on the grounds of saving energy. But this argument was already considered highly questionable at the time. German estimates from 1974 had shown that only around 2 per thousand of energy could be saved with summer time, too little to justify the burden on farmers and other interest groups due to the time change. The introduction of summer times in all Central European countries by 1981 was not a consequence of the energy crises of 1973 and 1979/80, but a measure on the way to the creation of a uniform European internal market. The standardization of the validity periods came from the European Economic Community (EEC) . The first drafts from 1976 (1976 / C79 / 38, 1976 / C131 / 12) then came into force with Directive 1980/737 / EEC, which initially referred to the period 1980/81. The daylight saving time was from the last Sunday in March to the last Sunday in September, time change at 1:00 UTC (2:00 CET ↔ 3:00 CEST), so that the first common daylight saving time on April 6, 1980, 2:00 CET lasted until September 28, 1980, 3:00 CEST. (Switzerland did not follow suit until a year later.) For the time being, these rules were regularly re-established until Directive 2000/84 / EC introduced a regulation that was valid for an indefinite period. The current rule was introduced in 1996.

Western European Summer Time

The time difference between Western European Summer Time (WEST) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) (formerly Greenwich Mean Time , GMT / Universal Time , UT) is one hour ( UTC + 1 ), while Western European Time (Standard Time) deviates from UTC by zero hours ( UTC ± 0 ). In international usage, Western European Summer Time is also referred to as Western European Summer Time (WEST) or Western European Daylight Saving Time (WEDT, American also WET DST), in Great Britain as British Summer Time (BST).

central European Summer Time

In the zone of Central European Time (CET) DST is the Central European Summer Time (CEST) in English Central European Summer Time (CEST, British) or Central European Daylight Saving Time (CEDT, CET DST, American) or Middle European Summer Time (MEST). While CET corresponds to the mean solar time on the 15th eastern longitude, on which, for example, Görlitz , Stargard in Poland and Gmünd in Lower Austria are located, CEST corresponds to the mean solar time on the 30th eastern longitude, on which, for example, Saint Petersburg and Kiev are.

The time difference between Central European Summer Time (CEST) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) (formerly Greenwich Mean Time, GMT / Universal Time, UT) is two hours ( UTC + 2 ), while Central European Time (Standard Time) deviates from UTC by one hour ( UTC + 1 ).

Central European summer time begins on the last Sunday in March at 2:00 a.m.CEST, with the hour count being advanced by one hour from 2:00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m., and ends on the last Sunday in October at 3:00 a.m.CEST, by setting the hour count back one hour from 3:00 a.m. to 2:00 a.m. The hour from 2:00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m. appears twice in autumn. The first hour (from 2:00 am to 3:00 am CEST) is designated as "2A" and the second hour (from 2:00 am to 3:00 am CET) as "2B". This means that on the night of the changeover in spring, for example, the time "6:00 am" is already five hours after midnight, whereas in autumn it is only seven hours after midnight. In a sense, the hour “saved” in spring is “given back” in autumn.

The Central European Midsummer Time (MEHSZ = UT + 3) - also called double summer time - was a special time zone in 1945 and 1947 in Germany. It corresponded to the British Double Summer Time (UT + 2) as the summer time of War Time (UT + 1).

Eastern European summer time

The time difference between Eastern European Summer Time (EESZ) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) (formerly Greenwich Mean Time, GMT / Universal Time, UT) is three hours ( UTC + 3 ), while Eastern European Time (normal time) deviates from UTC by two hours ( UTC + 2 ). In international usage, Eastern European Summer Time is also referred to as Eastern European Summer Time (EEST) or Eastern European Daylight Saving Time (EEDT, also EET DST in American).

Russia stopped using daylight saving time on October 26, 2014.

Legal regulation of the time change to daylight saving time and back

See § 2 of the German Summer Time Ordinance.

- The changeover from normal to summer time takes place on the last Sunday in March at 1:00 a.m. UTC, i.e. from 2:00 a.m. CET to 3:00 a.m. CEST in the Central European time zone.

- The changeover from summer to normal time takes place on the last Sunday in October at 1:00 a.m. UTC, i.e. from 3:00 a.m. CEST to 2:00 a.m. CET in the Central European time zone.

In order to be able to distinguish between the double appearing hours from 2:00 a.m. CEST to 3:00 a.m. CET at the end of daylight saving time, the hour before the time changeover is designated as 2:00 a.m. and the hour after the changeover as 2:00 a.m. Such a distinction with A and B was already practiced in Germany in 1917 according to § 3 of the announcement on summer time. It must not be confused with the internationally customary abbreviation of the time zones, after 2:00 a.m. CEST they are designated as 2: 00B and 2:00 a.m. CET as 2: 00A.

Implementation in Germany

In Germany, the time change is determined by ordinance. Section 5 of the Unit and Time Act (EinhZeitG) authorizes the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy to issue corresponding ordinances. Up to and including 2001 the time ordinance from 1997 was in effect, until then in 2002 with § 1 summertime ordinance the summertime was introduced for an indefinite period. According to § 3 of the Summer Time Ordinance, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy announces the start and end of summer time, most recently for the years 2016 to 2020.

The Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) in Braunschweig is responsible for the technical implementation of the time changes . The PTB controls the pulse-generating atomic clocks in Braunschweig. Their time is compared with the clock on the long-wave transmitter DCF77 in Mainflingen near Frankfurt am Main , which transmits time signals from there. These go to all public and private radio-controlled clocks , the control technology of power stations and substations , the clocks of Deutsche Bahn AG, the driving control of the subways and around 50,000 traffic lights.

In 2021, daylight saving time lasts from March 28th to October 31st.

Regulations outside of Central Europe

The Western European Time and Eastern European Time are - absolutely - switched to daylight saving time at the same time as Central European Time, i.e. at 1:00 a.m. and 3:00 a.m. respectively.

In Russia, too, summer time began and ended on the same days as in Central Europe. There the clock was put forward by one hour, but as a result by two hours compared to the respective zone time, because the so-called decree time, which continued to apply from Soviet times , stipulates the addition of one hour to the respective zone time for the whole year. Summer time has not been postponed since 2011. In October 2014, however, Russia switched back to normal time and will not use summer time every six months in the future.

The Ukrainian parliament passed an ordinance in autumn 2011 that abolished the change to normal time. This measure was reversed a few weeks later. The change between summer and normal time has been carried out in Ukraine since 1981 at the same time as most European countries.

Other countries with daylight saving time have different changeover dates. The summer time begins in March or April and ends in September, October or November (in the states in the southern hemisphere the other way around).

North America

The US first used daylight saving time in World War I until the end of it. During the Second World War , a War Time was the same year-round as summer time .

In the summer of 1946, many states and areas returned to daylight saving time. Since 1966, a federal law has stipulated when summer time can begin and must end.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 determines in Sec. 110 with the title Daylight Savings , that summer time begins in 2007 on the second Sunday in March and ends on the first Sunday in November. It starts three or four weeks earlier and ends a week later than before.

There is no daylight saving time in the states of Arizona (with the exception of the Diné area , the Navajo Nation Reservation ), Hawaii and most of the US American suburbs, nor in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan , part of a region in British Columbia ( Peace River Regional District ) and the Mexican state of Sonora bordering Arizona .

In Mexico , daylight saving time begins on the first Sunday in April, one week later than in Europe. Regions close to the border with the USA have pragmatically adopted the changeover date of the neighboring country, which has been customary since 2007. Daylight saving time ends on the last Sunday in October, the same day as in Europe. In the USA and Mexico, the clocks are not changed at the same time as in Europe, but are set in March / April at 2:00 local time (e.g. 10:00 UTC in California , 7:00 UTC in New York ), and in October / November reset to 1:00 a.m. at 2:00 p.m. local daylight saving time.

Near the equator or the pole

On the tropics the time of sunrise fluctuates less than ± ¾ hours per year, and on the equator it fluctuates by less than ± 20 minutes (due to the equation of time ). For comparison: In Flensburg it fluctuates by around ± 2½ hours, based on the mean value during the equinoxes in March and September. Summer time, i.e. a (partial) adjustment of the beginning of the clear day to the time of sunrise, is therefore not (no longer) practiced by many equatorial states (see map). There is currently no summer time anywhere directly on the equator.

In the polar circles , switching back and forth by one hour per year would not be sufficient by far, because the time of sunrise there fluctuates by six hours. Beyond the polar circles, a summer time would no longer be an adjustment of the beginning of the clear day to the time of sunrise, because the clear day in the polar summer can be 24 hours long (at the poles for half a year).

List of all states with daylight saving time

The information is based on data for 2019.

- All member states of the European Union

- States and areas in which daylight saving time applies in the same period as in the EU (until 2020):

- in Europe: Albania , Andorra , Bosnia and Herzegovina , Faroe Islands , Gibraltar , Kosovo , Liechtenstein , Moldova , Monaco , Montenegro , North Macedonia , Norway , San Marino , Switzerland , Serbia , Ukraine (not in Crimea , " Donetsk People's Republic ", " People's Republic Luhansk ”), Vatican City

- outside Europe: Lebanon

- States and areas that have daylight saving time in a different period (all are outside Europe)

- in the northern hemisphere (summer time also applies to the northern summer solstice around June 21 and the middle of the year):

-

- Bahamas , Bermuda , Greenland (partially), Haiti , Iran , Israel , Jordan , Canada (partially), Cuba , Mexico (partially), Palestinian Territories , St. Pierre and Miquelon (to F), Syria , Turks and Caicos Islands , USA except Arizona , Hawaii , American Samoa , Guam , Northern Mariana Islands , Puerto Rico , United States Minor Outlying Islands , US Virgin Islands

- in the southern hemisphere (summer time also applies to the southern summer solstice around December 21 and the turn of the year):

Advantages and disadvantages

Use of daylight

Boundary lines of the yellow field (light day): time of day of sunrise (below, black) and sunset (above, blue);

green and red line: sunrise and sunset in summer time.

The time change intends to adjust the rhythm of life to the time of daylight, so that people can spend and use a larger part of their waking state in sunlight. In midsummer, for example, the time of sunrise is no longer around 3:30 a.m. normal time, but around 4:30 a.m. daylight saving time. Accordingly, the time of sunset shifts from approximately 9:00 p.m. normal time to 10:00 p.m. summer time. Today most people orient their daily routine more according to the time than the position of the sun; the majority of people still sleep at 3:30 a.m. in the morning, but not yet at 10:00 p.m. in the evening. Therefore, the waking phase associated with the time of most people corresponds more closely to the time of daylight. Leisure activities in the afternoon and evening are also possible longer in sunlight and more pleasant outside temperatures, including: in popular sport.

For professional activities that take place outside, it is also in the morning, for example. B. on hot summer days cool for an hour longer. On the one hand, the longer daylight in the evening in connection with a higher temperature can be perceived by people who have to go to bed early as disturbing when falling asleep, on the other hand, the night's rest is not impaired by an early sunrise. The consequences of a lack of adaptation are illustrated by the development in Russia, where permanent summer time was initially introduced in 2011, but in 2014 a change to permanent normal time took place due to the late sunrise in winter. Since then, there has been an unnecessary loss of daylight hours in the evening and sleep disturbances due to too early sun exposure in the morning.

Energy requirements

One of the official reasons for the introduction of summer time at the beginning of the 20th century was to save energy (especially lighting ). However, this argument has always been controversial. Because compared to other influences, the effect of the time difference on energy consumption is negligible. As early as the autumn of 1916, a head of a municipal energy company pointed out that gas consumption was not only dependent on summer time, but also on the following factors: “Limitation of public lighting, cool and wet weather, decline in business life, earlier business hours, restrictions industry, poor economic situation, simplification of kitchen operations due to the rise in food prices and the lack of long-cooking foods (meat), operational restrictions for bakers and butchers, reduction in tourism, introduction of coin operated gas meters. "

Although it was clear very early on that summer time could not have a decisive influence on energy consumption, this argument persisted in the public's consciousness. But especially with the reintroduction of summer time in the Central European countries between 1976 and 1981, possible energy savings - if at all - played only a subordinate role compared to the argument of a Europe-wide standardization of times.

Summertime can have opposite effects on regional energy consumption. In parts of Indiana, for example, after the introduction of summer time in 2006, it rose by approximately 1%, which shows a comparison of the electricity consumption of almost 224,000 households. The originally pursued goal of saving energy could not be achieved. On the contrary, the energy balance turned out to be unfavorable, since “minor savings in spring contrasted with even greater power consumption in late summer and autumn”. In particular, increased demand for heating in the early morning hours and greater use of air conditioning in the longer afternoons and warm summer evenings increased overall energy consumption, for which the residents of the parts of Indiana examined paid around 8.6 million US dollars more per year. The authors also calculated the cost of increased pollution to society at between $ 1.6 million and $ 5.3 million annually.

However, the data from this study only related to private households. Industrial plants and other economic sectors were not included. The authors suspected, however, that most companies adhere to normal working hours in daylight and are therefore less affected by the daylight saving time change than private households.

In response to a request from the FDP parliamentary group in 2005, the federal government confirmed that hardly any energy was saved in Germany due to the seasonal time change. However, they want to stick to the changeover as long as the member states of the EU do not jointly intend to abolish summer time.

The Federal Environment Agency also found no positive energy-saving effects, since the savings in electricity for lighting are "overcompensated" by the increased consumption of heating energy by bringing the main heating time forward. The increasing use of energy-saving lamps would further intensify this effect in the future. The Federal Association of Energy and Water Management comes to a similar assessment . In 2009, going it alone was again rejected because a uniform time regulation was "essential for the smooth functioning of the internal market".

Alternatives to the intended energy savings through summer time

Particularly in the centrally controlled planned economies of the Eastern Bloc, slightly staggered working hours were introduced in some countries (start of work in the various companies 7 a.m. to 9 a.m.) in order to reduce electricity consumption in the morning. After all, it is not only the total consumption that is decisive for securing the power supply, but also the consumption peaks, for which additional power plant capacities would be required as reserves. The public transport of people and the private car traffic with the morning rush hours was also distributed and relieved somewhat.

Regardless of the summer time, in some industries and companies a different position of the working hours in summer and winter was handled long before - which also required a change in the sleep and wake rhythm in the respective season.

In the GDR, all school lessons were postponed by two hours at the beginning of 1969 in order to save energy. However, this practice was given up after a week, as the morning energy savings were canceled out by energy consumption in the afternoon hours.

Human biology

Summertime advocates argue that today's lifestyle has changed. It is therefore advantageous for many people to be able to spend longer leisure time in the evening in daylight, which increases their productivity. Critics argue that when the time changes, the adjustment to the new daily rhythm takes at least several days, is harmful to health and reduces productivity during the changeover phase. It states that physiological studies, according to which some circadian fluctuating hormone levels, similar to that of the stress hormone cortisol , up to four and a half months needed to fully adapt to the new situation (the change in the spring more problems ready). However , it has not been proven whether these hormone level fluctuations alone have a disease-promoting effect.

Deviation from the position of the sun

The midday of today's no longer in use true local time (WOZ) divides the period between sunrise and sunset almost symmetrically : The sun has its highest position at 12 o'clock. after this point in time. The more evenly running mean local time (mean solar time), which became necessary through the use of mechanical clocks , differs from the true local time only by the equation of time , which fluctuates between −14 and +16 minutes over the year.

Additional deviations have existed since the use of zone times: ideally up to ± 30 minutes from the mean local time. Larger values could be avoided by using the previous / next zone time. d. As a rule , national and domestic territorial boundaries running midway between the reference meridians of the time zones and by politically motivated choice of the time zone are prevented. In countries with Central European Time (CET; reference meridian: 15 ° East) these additional deviations are +36 minutes on the western border of Germany and +96 minutes on the western border of Spain ( Galicia ). China , which extends far to the east-west, is not divided into several time zones, which is why this additional deviation on its western edge is more than +3 hours from the official time (reference meridian: 120 ° East). (However, China does not use daylight saving time nationwide.)

During summer time, these positive deviations, some of which are already considerable, increase by a further hour in the part of a time zone west of the reference meridian; Sun noon is 1:36 p.m. on the western edge of Germany and 2:37 p.m. on the western edge of Spain. In the part of a time zone east of the reference meridian, on the other hand, the negative deviations either decrease in amount by one hour or they change their sign; For example, in north-east Norway in Grense Jakobselv, sun noon is reached at 11:57 am instead of 10:57 am during normal time. All information does not take into account the equation of time (see above).

Technical effort

All clocks have to be changed twice a year. More and more clocks are now set automatically via a radio signal ( radio clock ), but many still have to be changed manually, especially in private households. Computer clocks can also be set automatically via a function of the operating system . However, there are computer programs with real-time functions that do not use the operating system function for daylight saving time and have to be reconfigured manually. There is the same problem with leap seconds .

When switching, watches that are initially forgotten, for example in photo cameras, can later cause confusion. The event recordings of such clocks that are supervised by an authorized group of people can be problematic if the changeover is only carried out a few days later and the stored times and the evaluations based on them are therefore incorrect.

No linear timescale

With summer time, a time scale that runs evenly - for a certain area - is abandoned and two leaps are introduced per year . In spring, at the time of the first change per calendar year (assumption: northern hemisphere), coordinates in an interval of 60 minutes are missing from the legal time scale . When resetting in autumn, time coordinates of an equally long interval are found twice. So the scale becomes ambiguous , arithmetically it has a gap and an overlap.

In Central Europe, for example, it is necessary to specify the time. B. October 28, 2018, 2:33 a.m. additionally the indication of which scale the time coordinate refers to: CET or CEST. This means additional programming and computing effort and a possible source of errors. To determine the changeover days , the weekday calculation to determine the last Sunday of the month in March and October is necessary.

Worldwide, time comparisons and time coordination based on local time information across country and zone borders can only be achieved by consulting tables that change over time - politically -; therefore certainly only for the past.

Effects of the change

Psychology and medicine

According to a study by Imre Janszky and Rickard Ljung, switching to summer time increases the risk of heart attacks . Other psychologists and doctors have found negative effects of the time change, as the adaptation of the organism's chronobiological rhythm can be problematic. Especially people with sleep disorders or organic diseases seem to have greater difficulties here. In a representative survey by the DAK in October 2019, 29% of the participants stated that the changeover caused them complaints.

In the course of the discussion about a future abolition of the time change, several sleep researchers and chronobiologists, including representatives of the Charité , the University of Groningen and the University of Regensburg , plead for a permanent retention of normal time. In the case of permanent summer time, they see the risk that the synchronization of the human internal clock will be impeded by the late sunrise in the winter months and the lack of daylight in the morning. Even the evening brightness in summer is judged by some to be difficult for people who have to get up very early. Scientists at the University of Salzburg, on the other hand, consider the negative consequences to be insufficiently researched and proven to be able to derive a general recommendation for or against summer time. They also refer to the flexibility of people's individual sleeping habits in modern society.

The "International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems" ( ICD ) contains the clinical picture of non-organic disturbance of the sleep-wake rhythm (ICD-10 code: F51.2), comparable to jet lag .

Animals and agriculture

It is known from agriculture that dairy cows need about a week to adapt to the new milking times . Especially with the time change in autumn, the changed daily routine on the farms can be clearly seen by the loud mooing of some cows in the morning. With the spring changeover, the milk yield is lower for a few days. Most farmers spread the time change for milking over several days in order to mitigate the consequences. The change in the human daily rhythm can also affect the feeding behavior of pets. Experts therefore recommend a slow change by postponing the daily routines by 10 to 15 minutes.

Night shifts

While the clock change for most citizens takes place “in their sleep”, so to speak, it poses more or less major problems for various institutions. Facilities with night-time on-call duty have to struggle with the fact that either the duty is one hour longer or the rest time is shortened by one hour and thus possibly no longer meets the legal requirements. Therefore, separate duty rosters often have to be created for the day of the time change, which causes additional costs.

Road traffic

It is not clear whether the time change has an impact on the number of traffic accidents in the changeover phase; Investigations on this came to different results. The accident rate is generally lower during summer time. After the changeover in autumn, there is a warning of an increased risk, as the evening rush hour traffic then coincides more with the deer crossing at dusk.

Public transportation

When switching from normal to summer time, the trains run to the destination station with a delay of one hour. On the digital clocks of Deutsche Bahn , the display shows 3:00 after 1:59 a.m. The analog station clocks are brought forward by additional half-minute clock pulses. It takes about five minutes to change the analog clock.

Trains that are on the move during the changeover to summer time (usually freight trains, night trains and S-Bahn trains in the metropolitan areas) are missing an hour. Whenever possible, freight trains are sent on their way before the scheduled departure time so that they reach their destination with little or often no delay. S-Bahn trains that would only be on the move within this hour are canceled. Night trains often have longer stops according to the schedule, which can be shortened. Where this is not possible, the trains arrive late on that day.

In the opposite case, i.e. when the clocks are set back in autumn, the hour is available twice between 2:00 and 3:00. Trains that are en route during this hour will be stopped at a suitable station for one hour. As a result, the train arrives on time according to the timetable, but the actual travel time still increases by one hour. This stopping rule is only used for trains that have a long way to go. Trains that run every hour or more often, whose scheduled departure time is between 2:00 and 3:00 a.m., must depart twice. This increases the number of vehicles and personnel required. In addition, special timetables have to be created for this time change, because this "duplicate" train with the same train number would lead to error messages in the signal box electronics.

This procedure is used by Deutsche Bahn, the Swiss and Austrian Federal Railways and other European railway companies.

aviation

The aircraft , which usually flies over multiple time zones and is coordinated, still working with the Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) , which from the Daylight savings time is not affected. So there are no airplanes waiting anywhere, as is the case with the railroad. Only the conversion to local time is shifted by one hour - i.e. the boarding and disembarking time for passengers, which is given in local time at the airports. This may lead to aircraft arriving at the destination in the morning before the end of a night flight ban in effect in local time. Such flights usually leave later the evening before.

science and technology

Data recordings that use the legal time as a time stamp can only be evaluated if the daylight saving time regulation valid at the time of recording is known.

Information technology

IT systems must be equipped or maintained for the changeover.

Many operating systems use a system based on Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) (such as Unix time ) as the system time and for stored time stamps . Since these systems do not have daylight saving time, daylight saving time has no effect on operations; this is only taken into account when calculating the legal time for a user-friendly display. There are also operating systems that instead use the legal time as the system time and for stored time stamps, but do not store any information in these time stamps about whether this is normal time or daylight saving time. As a result, in addition to the hour gap at the beginning and double time stamps at the end of daylight saving time, there is another problem: What is the appropriate time for saved time stamps in local time in Coordinated Universal Time, and how are saved time stamps (e.g. on files) when active Daylight saving time on the one hand and normal time on the other hand - and which of the two displays is correct?

If standards such as UTC are not used, the following problems arise when switching from daylight saving time to normal time:

- Apparently non-chronological log entries (after 2:59 a.m. - after resetting from 3:00 a.m. to 2:00 a.m. - again 2:00 a.m.),

- Apparently duplicate entries (one hour after 2:14 a.m. comes again at 2:14 a.m.),

- Jobs that are accidentally executed twice (a job scheduled for e.g. 2:30 a.m. expires twice),

- Data that - in networked IT systems - appears to arrive earlier than it was sent if the sending system is not switched over at the same time as the receiving system. (Example: The non-converted external system sends a message at 3:01 a.m., which arrives at the converted main system at 2:01 a.m.) Architectures in which data stored locally and on the server side are synchronized on the basis of the time stamp lead to differences in the Time stamp for a time and resource consuming copying of all data, although this would not be necessary.

This can mess up evaluations. Database systems that are closely tied to the date and time can become inconsistent .

The change in time usually depends on the operating system. Some need manual intervention, others can make the change automatically. However, the time jump does not always take place at the legally stipulated time, but "depending on the implementation" maybe a few minutes later. Even with the fully automatic changeover, incorrect implementation of the daylight saving time regulation repeatedly results in incorrect time information and incorrect behavior of the devices over a longer period of time.

Complex software systems can also have a “time management” that differs from the operating system. So there are z. In newer SAP systems, for example, there is a "time expansion" in which the "SAP time" runs more slowly from 2:00 CEST to 3:00 CET, thereby completely avoiding the time jump. With such solutions, however, the coordination with other systems whose time runs differently remains open.

Due to the change in daylight saving time in the USA, Canada and Brazil (see above), adjustments to many software systems were necessary for the changeover to daylight saving time in 2007. For systems that are no longer fully maintained by the manufacturers, this could lead to problems with the automatic time changeover. The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority maintains a constantly updated list of daylight saving time and time zone changes in all areas of the world in its database. This database is integrated in all modern operating systems (e.g. via the package tzdataunder Linux ).

Practice of religion

The time change also leads to problems in the practice of religion. Jewish and Muslim times of prayer and fasting depend on the position of the sun. Summer time regulations therefore change the time between morning prayer and the start of work or the end of work and evening prayer or the breaking of the fast. Because of this, there have always been conflicts between religious and secular Jews. Therefore, since 2005, summer time in Israel has ended before Yom Kippur (strict fasting day). In 2011, the Palestinian Authority suspended summer time between August 1st and 29th for Ramadan so that the waiting time before breaking the fast in the evening was not too long; in the Gaza Strip it was ended entirely.

The rules that have been in force since 1852 on the use of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem by the various denominations do not provide for summer time. Therefore, the opening and prayer times in summer are still based on normal time, while outside the church, summer time applies.

Political development

Germany

In April 2014, the German ruling party , the CDU, passed the party congress resolution to campaign for the abolition of the time change and a uniform new regulation within the EU. In January 2017, the CDU / CSU parliamentary group took up this decision. Nevertheless, as part of the grand coalition , the Union parties voted in March 2018 against the FDP's motion in the German Bundestag to support an end to the time changeover at EU level.

In a representative survey by YouGov in March 2016, 60% of those questioned rejected the time change. In a further representative survey on behalf of the health insurance company DAK in spring 2018, 73% of the participants spoke out against the time change.

Since the European Union sought to abolish the previous regulation, surveys about the preferred time in Germany have come to different results. While two surveys by the Kantar Group in October 2018 and March 2019 were in favor of summer time, in a YouGov survey commissioned by the Market and Social Research Initiative in September 2018, a majority voted for normal time, using the terms winter and summer time were deliberately not used.

Apart from requests to speak from individual politicians, the German government has so far not taken a united stance on this issue. The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi), whose head Peter Altmaier , spoke out in favor of permanent summer time in October 2018, is in the lead. However, the ministry is still in a coordination process with German associations, other ministries and the EU states in order to achieve a harmonized solution.

Statements from the business world and various associations have not yet yielded a uniform picture of opinions. In a survey of more than 1,300 companies carried out by the Ifo Institute for Economic Research between April and June 2019, both normal time and summer time were both 38% popular. The remaining 24% were undecided by then. Many companies from the energy sector were more in favor of normal time, while retail and hospitality in particular preferred summer time. In September 2018 , the German Hotel and Restaurant Association (DEHOGA) advocated permanent summer time. Sharp contradiction came from the German Teachers' Association (DL), which in March 2019 demanded permanent normal time and considered permanent summer time to be irresponsible. At the end of March 2019, the Federation of German Industries (BDI) called for a uniform EU regulation in order not to damage the logistics of the European internal market . The Central Association of the German Construction Industry (ZDB) feared a foreseeable chaos and advocated maintaining the time change.

Balearic Islands

In October 2016, the regional parliament of the Balearic Islands unanimously accepted the request of the left-wing ecological party Mes de Menorca to maintain summer time throughout the year. At the same time, it was against the reverse efforts of the central government of Spain to abolish summer time, i.e. to introduce normal time all year round. After the application has been accepted, the regional government wants to work with the central government in Madrid and the European Union to ensure that the Balearic Islands may suspend the time change in future. The year-round maintenance of summer time (CEST) would bring "health, economic and social benefits" with it.

Poland

In Poland , the opposition peasant party Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe won approval from all Sejm factions in 2017 after its chairman Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz called for Central European summer time to be introduced for the whole year from October 1, 2018. The project also met with approval from the PiS government. A spokeswoman for the Polish Ministry of Economics rejected the project: “Going it alone would mean that we would have to change the clock six months a year if we crossed our western or southern border. The consequence would be a mess in the cooperation with our closest partners, also for tourists. ”In addition, the EU Commission is dealing with the demands for an EU-wide abolition of the time change.

European Union

On February 8, 2018, the contracted EU Parliament , the EU Commission at 384: 153 votes in order "to present in-depth evaluation of the Directive on summer-time arrangements and to submit any proposals for its revision" one. From July 5 to August 16, 2018, more than 500 million EU citizens were able to express themselves online about their experiences with summer time and the question of whether or not to keep or abolish the time change. According to the Commission, more than 4.6 million responses were received, which is a record compared to other public surveys. In the survey, 84% of the participants were in favor of abolishing the time change. The survey is not considered representative .

Participation in the survey was highest in Germany , where 3.79% of the population took part. Austria (2.94%), Luxembourg (1.78%), Finland (0.96%) and Estonia (0.94%) came next . The lowest participation was recorded in the United Kingdom (0.02%), Italy , Romania (0.04% each), Denmark (0.11%) and the Netherlands (0.16%). In two of the 28 EU Member States, the majority of participants were in favor of keeping the clock change, namely in Greece (56%) and Cyprus (53%). In all other EU countries, the majority of the participants spoke out in favor of abolishing the time change. Survey participants in Finland and Poland had the highest approval rate for the abolition of the clock change (both 95%). In the event of the changeover being abolished, most of the participants across the EU were in favor of “permanent summer time”. A similar picture emerged in Germany and Austria.

Afterwards, when the survey results were announced on August 31, 2018 , EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker announced that the EU Commission would aim to abolish the time change in accordance with the determined will of the people. This required the approval of the EU Parliament (which was considered safe and was later granted, see below) and still requires the approval of the EU member states. Lithuania , Estonia , Latvia and Finland had previously spoken out in favor of abolishing the time change.

The British government said after the vote that it "currently has no plans to abolish the clock change". Norbert Hofer , Transport Minister of Austria, who led the EU Council Presidency in the second half of 2018 , said on December 3, 2018 that the time changes would be abolished in 2021 at the earliest in order to allow longer coordination during implementation.

On March 26, 2019, 410 members of the EU Parliament voted for the abolition of the clock change, 192 against. The last changeover should take place in 2021. The member states can then decide for themselves whether they want to keep normal time or the previous summer time. However, the individual states have difficulties with the abolition of summer time for various reasons, especially since the time change in most countries (with the exception of Germany and Austria) is not an issue that concerns the masses. In addition, many governments fear a patchwork of different time zones and are calling for a more detailed impact assessment. In addition to the already existing three time zones within Europe, things could get even more complicated if, for example, of two neighboring countries, the eastern one decides for Central European time and the western one for Eastern European time.

When and whether an agreement could be reached at all was still largely unclear at the end of October 2019. While many countries have apparently not yet taken a clear position on the question of what time should apply to them from now on, Portugal and Greece are more inclined to maintain the biannual change. If the previous compromise regulation was abandoned , a change in the current time zone division is now considered to be inevitable, because otherwise the daylight phases would change too drastically, especially at the edges of the large Central European zone. In the north-west of Spain, for example, with permanent summer time in winter, the sun would not rise until after 10 a.m., in eastern Poland with permanent normal time in summer it would already rise around 3 a.m. Since even with the current regulation the sun sets in Warsaw in December before 3:30 p.m., a large part of the population in Poland and across party lines in parliament advocate permanent summer time.

The Benelux countries want to coordinate their next steps and are considering a joint referendum. It is still uncertain whether the French government will follow the vote of a citizens' survey initiated by the National Assembly in February 2019, in which 59% of the more than 2 million participants voted for permanent summer time.

See also

literature

- Michael Downing: Spring Forward. The Annual Madness of Daylight Saving Time. Shoemaker & Hoard, Washington, DC 2005, ISBN 1-59376-053-1 .

- Johannes Graf, Claire Hölig: Who turned the clock? The story of summer time. German Clock Museum, Furtwangen 2016.

- David Prereau: Why We Put the Clocks Forward. Granta Books, London 2005, ISBN 1-86207-796-7 .

- Peter Spork : Wake up! Departure to a good rested society. Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-446-44051-7 .

Web links

- www.zeitzonen.de - Information on the handling of daylight saving time in all countries with current time information

- www.timeanddate.com - current news about time zones

- Sources for Time Zone and Daylight Saving Time Data - international database for summer time including historical data (English)

- www.ptb.de - List of local times in many countries at the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt, working group 4.41 "Time standards"

- www.medizinfo.de - medical facts about the time change

- BT-Drs. 18/8000 Balance of Summer Time - Report of the Committee for Education, Research and Technology Assessment of the German Bundestag on the effects of summer time on energy consumption, the economy, health and the legal framework; Berlin, March 30, 2016

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b § 4 Unit and Time Act of the Federal Republic of Germany.

-

↑ Sbírka zákonů a nařízení republiky Československé, částka 92/1946 Law and Ordinance Gazette of the Czechoslovak Republic, No. 92/1946, p. 140/1239, of November 27, 1946:

No. 212: Zákon ze dne 21. listopadu 1946 o zimním čase (law of November 21, 1946 on winter time)

No. 213: Vládní nařízení ze dne 27. listopadu 1946 o zavedení zimního času v období 1946/1947 (regulation of November 27, 1946 introducing winter time in 1946/1947 ). - ↑ Ústavodárné Národní shromáždění republiky Československé 1946 Government proposal for a winter time law with justification, November 15, 1946.

- ^ Benjamin Franklin: Aux Auteurs du Journal. In: Journal de Paris. No. 117, April 26, 1784.

- ↑ Time change: Summer time - a bad joke. Spiegel online , March 26, 2016.

- ^ GV Hudson: Art. LVIII. On seasonal time. Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand, Vol. 28, 1895, p. 734 (online) .

- ^ W. Willett: The Waste Of Daylight. Sloane Square, London 1907 ( online ).

- ^ GV Hudson: Art. LVIII. On seasonal time. Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand, Volume 31, 1898, p. 577 (online) .

- ^ Victor von Röll : Summertime (lexicon entry). In: Encyclopedia of Railways. 2nd edition, Urban & Schwarzenberg, Berlin / Vienna 1912–1923. 1923, Retrieved April 8, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Announcement about the bringing forward of the hours during the period from May 1 to September 30, 1916 from April 6, 1916, RGBl., P. 243.

- ↑ RGBl. No. 111/1916: Ordinance of the entire ministry of April 21, 1916, regarding the introduction of summer time for the year 1916. In: RGBl. for the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council. LVI. Piece, issued on April 22, 1916, p. 247 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ In Great Britain daylight saving time was introduced on May 17th, 1916, in France on the night of June 14th to 15th, 1916. Compare: Johannes Graf, Claire Hölig: Who turned the clock? The story of summer time. Furtwangen 2016, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Ordinance on the introduction of summer time of January 23, 1940, RGBl., Pp. 232–233.

- ↑ RGBl. I, February 9, 1940, p. 298.

- ↑ The confusion of time after the end of the war and the introduction of a uniform daylight saving time or a double daylight saving time in 1947 describes: Johannes Graf, Claire Hölig: Who turned the clock? The story of summer time. Furtwangen 2016, pp. 62–68.

- ^ German Bundestag, 8th electoral period, 25th session Bonn, May 5, 1977, p. 1749.

- ↑ a b c Yvonne Zimber: Summer times and high summer times in Germany up to 1979. Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt, Arbeitsgruppe Zeitnormale 2003 - The Scheidemann cabinet> Volume 1> Documents> No. 14 b Cabinet meeting of March 15, 1919> VII. Summer time , on federal archive .de.

- ↑ a b Announcement about the bringing forward of the hours during the period from April 16 to September 17, 1917 from February 16, 1917, RGBl., P. 151.

- ↑ Announcement about the bringing forward of the hours from April 15 to September 16, 1918 from March 7, 1918, RGBl., P. 109.

- ↑ a b Ordinance on the introduction of summer time of January 23, 1940, RGBl., Pp. 232–233.

- ↑ a b c Ordinance on the extension of summer time of October 2, 1940, RGBl., P. 1322.

- ↑ a b c Ordinance on the reintroduction of normal time in winter 1942/1943 of October 16, 1942, RGBl., Pp. 593-594.

- ↑ a b c Ordinance on the reintroduction of normal time in winter 1943/44 of September 20, 1943, RGBl., P. 542.

- ↑ a b c d Ordinance on the reintroduction of normal time in the winter of 1944/45 of September 4, 1944, RGBl., P. 198.

- ^ Minutes of the 47th meeting of the Allied Control Council .

- ^ Minutes of the 113th meeting of the Allied Control Council.

- ^ Minutes of the 135th meeting of the Allied Control Council.

- ^ Minutes of the 140th meeting of the Allied Control Council.

- ^ After Grimm, Hoffmann, Ebertin, Puettjer: The Geographical Positions of Europe. Ebertin-Verlag, Freiburg 1994, summer time only began in 1949 at 3 a.m. CET (quoted from the Braunschweiger Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt ).

-

↑ The Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt Braunschweig (PTB) reports in its compilation of summer times and midsummer times in Germany up to 1979 : “The following list was kindly made available to PTB by the German Hydrographic Institute in Hamburg. With one exception (for 1945), the data coincide with those in Grimm, Hoffmann, Ebertin, Puettjer: The Geographical Positions Europe, Ebertin-Verlag, Freiburg 1994 (GHEP). In GHEP the relevant editions of the Reichsgesetzblatt and the meetings of the Control Council are given for the individual years. Therefore, the information from GHEP has always been included in the table. According to the GHEP, in 1945 and in some cases afterwards, different regulations applied to the western and / or the Soviet zone including Berlin, which are specified under c). ”Under c) it is stated:

“ c) Different regulations for the Soviet zone and Berlin according to GHEP

May 24th 1945, 2 a.m. CET (?) Changeover to CET by September 24, 1945, 3 a.m. CET (?), Then CEST by November 18, 1945, 3 a.m. CEST (?).

(According to the archive for journalistic work (Munzinger archive) 652 (time system) from November 25, 1961, 8670, there was also midsummer time from May 31 to September 23, 1945, without location information. " - ↑ a b nonsense of the people . In: Der Spiegel . No. 22 , 1980, pp. 157 and 160 ( online - May 26, 1980 ).

- ^ Ordinance on the determination of normal time in the GDR (Zeitordnung) of September 30, 1977, Journal of Laws of I, p. 346.

- ↑ Lost time . In: Der Spiegel . No. 45 , 1980, pp. 40 and 42 ( online - November 3, 1980 ).

- ↑ Tobias Kaiser: How the GDR set the clocks in Bonn. In: Welt am Sonntag. March 28, 2010.

- ↑ In Hungary there was summer time again from 1941 to 1949.

- ↑ RGBl. No. 274/1914: Imperial ordinance of October 10, 1914, with which the government is authorized to make the necessary dispositions in the economic field on the occasion of the extraordinary circumstances caused by the state of war. In: Reichsgesetzblatt for the kingdoms and countries represented in the Reichsrat. CLIV. Piece, issued on October 13, 1914, p. 1113 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ RGBl. No. 307/1917: Law of July 24, 1917, with which the government is empowered to make the necessary decisions in the economic field on the occasion of the extraordinary circumstances caused by the state of war. In: Reichsgesetzblatt for the kingdoms and countries represented in the Reichsrathe. CXXX. Piece, issued on July 27, 1917, p. 739 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ GVBl.-BH No. 167/1914: Law of 7 December 1914, with which the state government is empowered to make the necessary decisions in economic areas on the occasion of the extraordinary circumstances caused by the state of war. In: Law and Ordinance Gazette for Bosnia and Hercegovina. LIV. Piece, issued on December 12, 1914, p. 613 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ a b StGBl. No. 244/1919: Execution order of the state government of April 24, 1919, regarding the repeal of the execution order of April 15, 1919, St. G. Bl. No. 236, on the introduction of summer time. In: State Law Gazette for the State of German Austria. 84th issue, issued on April 26, 1919, p. 585 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ a b StGBl. No. 107/1920: Execution instruction of the state government of March 4, 1920 on the introduction of summer time for the year 1920. In: Staatsgesetzblatt für die Republik Österreich. 39th issue, issued on March 18, 1920, p. 190 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ a b LGVBl. for Salzburg 71/1920: Announcement of the provincial government in Salzburg of April 29, 1920, Zl. 1872 / Pres., regarding the resumption of summer time in the province of Salzburg. In: State Law and Ordinance Sheet for the State of Salzburg. LXII. Piece, issued on April 29, 1920, p. 199 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ a b RGBl. No. 111/1916: Ordinance of the entire ministry of April 21, 1916, concerning the introduction of summer time for the year 1916. In: Reichsgesetzblatt for the kingdoms and states represented in the Reichsrat. LVI. Piece, issued on April 22, 1916, p. 247 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ a b GVBl.-BH No. 38/1916: Ordinance of the state government for Bosnia and Hercegovina of April 25, 1916, line 4183 / Pres., Regarding the introduction of summer time for the year 1916. In: Law and Ordinance Gazette for Bosnia and Hercegovina. XXIII. Piece, issued on April 26, 1916, p. 93 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ RGBl. No. 115/1917: Ordinance of the entire Ministry of March 9, 1917, regarding the introduction of summer time for the year 1917. In: Reichsgesetzblatt for the kingdoms and states represented in the Reichsrat. L. Stück, issued on March 18, 1917, p. 279 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ GVBl.-BH No. 29: Ordinance of the state government for Bosnia and the Hercegovina of March 29, 1917, Z. 4930 / Pres., Regarding the introduction of summer time for the year 1917. In: Law and Ordinance Gazette for Bosnia and the Hercegovina. XVI. Piece, issued on April 2, 1917, p. 155 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ RGBl. No. 87/1918: Ordinance of the entire ministry of March 7, 1918, concerning the introduction of summer time for the year 1918. In: Reichsgesetzblatt for the kingdoms and states represented in the Reichsrat. XLII. Piece, issued on March 9, 1918, p. 231 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ GVBl.-BH No. 28: Ordinance of the state government for Bosnia and Hercegovina of March 19, 1918, Z. 3426 / Pres., Regarding the introduction of summer time for the year 1918. In: Law and Ordinance Gazette for Bosnia and the Hercegovina. XIV. Issue, issued on March 22, 1918, p. 63 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).

- ↑ Change with RGBl. No. 106/1918: Ordinance of the entire ministry of March 25, 1918, regarding the introduction of summer time for the year 1918. In: Reichsgesetzblatt for the kingdoms and states represented in the Reichsrat. L. Stück, issued on March 26, 1818, p. 267 ( online at alex.onb.ac.at ).