Carnuntum (military camp)

| a) Carnuntum legionary camp b) Carnuntum equestrian camp |

|

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Canunto , b) Carnontum , c) Carnunto , d) Arrunto , e) Carnuto |

| limes | Upper Pannonia |

| section | Route 2 |

| Dating (occupancy) |

a) Claudian-Neronian, around 70 AD to the end of the 4th century b) Domitian, 1st to 3rd century AD. |

| Type |

a) Legion camp and naval station b) Alenkastell |

| unit |

a)

b) |

| size |

a) 490 × 400 meters b) 225 × 178 meters |

| Construction | Wood-earth / stone |

| State of preservation |

a) The legionary camp is completely under agricultural land, only the southern flank tower of the east gate is still visible. b) The camp bath and sections of the southern and eastern fortifications are still visible. |

| place | Petronell-Carnuntum |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 6 ′ 58 " N , 16 ° 51 ′ 30" E |

| height | 109 m above sea level A. |

| Previous | Aequinoctium fort (west) |

| Subsequently | Small fort Stopfenreuth (east) |

Carnuntum is the name for a multi-period legionary camp , an auxiliary fort and a camp town that served to protect the Upper Pannonian Limes. From the 2nd century AD, the civil town of Carnuntum was also the administrative center of the Roman province of (Upper) Pannonia . It is the most important and most extensively researched ancient archaeological site in Austria and is located in the municipal areas of Petronell-Carnuntum and Bad Deutsch-Altenburg , Lower Austria . It is also the only legionary camp between Regensburg and Belgrade that has not been built over in a modern way and thus one of the most important archaeological monuments on the Danube Limes.

The region around a still unlocated Celtic settlement and power center, which the historian Velleius Paterculus referred to as "Carnunto, qui locus regni Norici" (in the Kingdom of Norikum), became a gathering point for the from the 1st century AD Expansion of the Romans into free Germania ( Barbaricum ) . There, an important connection to the south branched off from the Limes Road. On the foothills of the Little Carpathians , one of the most important settlement and defense areas in the northern provinces of the empire soon developed. Together with the auxiliary camp in Győr, the legion camp in Carnuntum is one of the oldest Roman fortifications on the Pannonian Limes . Carnuntum owed its rapid rise, among other things, to its favorable location at the intersection of two old transcontinental trade routes as well as the legionary and auxiliary camp, in which up to 6500 men were stationed at times. The coexistence of legions and auxiliary troops, in particular, emphasized the military and political rank of this location for the Romans. The forts of Carnuntum were repeatedly the focus of important political and military events during the Roman rule over Pannonia.

The oldest archaeological evidence from Roman times date to the middle of the 1st century AD. After the establishment of a temporary winter camp under the then general and later Emperor Tiberius (14–37), a solid piece of wood was created during the reign of Claudius (41–54) -Earth camp and two civil settlements. At the beginning of the 2nd century, around 50,000 people were already living there. The legionary camp was rebuilt in stone around 100 AD. In the middle of the 2nd century a cavalry fort was also built. During the Marcomann Wars , Emperor Marc Aurel (161-180) led his campaigns from Carnuntum into the tribal areas north of the Danube. At the end of the 2nd century, the governor of Upper Pannonia, Septimius Severus (193–211), was proclaimed emperor by the Danube regions; this resulted in another massive economic upswing for Pannonia. In late antiquity, a base for the Danube fleet was set up in Carnuntum. In 308 AD the tetrarchs held the Carnuntum Imperial Conference there . A severe earthquake devastated the region in the middle of the 4th century. This natural disaster combined with the steady reduction in the number of border troops and the disastrous effects of the great migration finally ushered in its economic and demographic decline. In the late 4th century, the already very dilapidated place served Emperor Valentinian I (364-375) as an army camp for a campaign against Transdanubian tribal groups. In the course of the 5th century the legionary camp was abandoned and abandoned by its Romanesque inhabitants. The so-called Heidentor , a partially preserved triumphal monument from the 4th century, is located between Limes and Bernsteinstrasse , today the landmark of the Carnuntum region.

Surname

The name Carnuntum / Karnuntum was taken over from the Celtic predecessor settlement and would refer to the Celtic deity Cernunnos in one of his name forms, since the common root of the names means carn horn. It could also be derived from an Illyrian idiom and mean 'stone wall, stone building, stone city, settlement on the rock or on the stone', which is now assumed to be outdated.

He was

- for the first time with the chronicler Velleius Paterculus ,

- later also in two places in Pliny ,

- with the geographer Claudius Ptolemy ,

- in the self-contemplations of Marcus Aurelius,

- in the Historia Augusta ,

- in the Notitia dignitatum ,

- with the late antique chronicler Ammianus Marcellinus ,

- in the Codex Theodosianus ,

- in the Annales regni Francorum ,

and in the main geographic sources,

- in the Itinerarium Antonini

- and in the Tabula Peutingeriana

mentioned.

location

The village of Petronell-Carnuntum is located between Vienna (Vindobona) and Bratislava on the Danube and Leitha rivers. The ancient Carnuntum was located about 40 kilometers east of Vienna, directly on the southern bank of the Danube (Danuvius) at the Danube breakthrough through the Little Carpathians , past which the river flows through the Hainburger Pforte (Porta Hungarica) near the mouth of the March . The steep bank of the Danube is interrupted at Pfaffenberg near Deutsch-Altenburg by the valley of a small stream, which provided an easily passable access to the Danube. The Braunsberg, the 480 meter high Hundsheimer Berg and its foothills, the Pfaffenberg, offered an excellent all-round view of the Marchfeld, the Danube floodplains and the mouth of the March. At Carnuntum, the Amber Road, coming from the north through the Marchtal, also crossed the Danube.

The ancient, ten square kilometers large populated area reached in the west from Petronell-Carnuntum to the Pfaffenberg near Bad Deutsch-Altenburg in the east. In the north it came across dense riparian forests. In the south, the settlement area extended to about the route of today's federal highway 9. Due to the natural edge of the terrain in this section, the camp was about 40 meters above the southern bank of the Danube. The topography and hydrology of the banks of the Danube have changed steadily since ancient times. The area at Carnuntum was also subject to constant changes. The reason for this is that the current has repeatedly sought new routes through the country and, with its debris and floods, has influenced the flora and fauna by creating new river loops. At that time the main stream probably ran a little further north.

Carnuntum was initially part of the neighboring Noricum. However, under Tiberius it was incorporated into its section of Pannonia because of the constant danger from barbarian incursions. After the province was divided into Pannonia superior (Upper Pannonia) and Pannonia inferior (Lower Pannonia) under Trajan (98–117), the place first came to Pannonia Superior and from the imperial reform of Diocletian (284–305) belonged to the newly founded Pannonia Prima (Diocese of Illyria) .

function

The possession of Carnuntum as the crossing point of two heavily frequented, transcontinental main trade and traffic routes was strategically extremely important for the Romans. At that time the Danube was the fastest connection between the west and the east of the Roman Empire. From the legionary camp, in addition to controlling the river, its crossings ( Stopfenreuth , Burgberg von Devin) and the mouth of the March to the north, traffic on the Amber Road leading from the north ( Baltic Sea ) to the south (Italy) could be monitored. As a result, in addition to customs revenue, import bans, export embargoes, etc. could also influence the economy. The other tasks of the crew included border security and signal transmission on the Danube Limes . From the camp plateau you also had a good view of the Marchfeld .

Road links

The legionary fort as the center of the Carnuntum area played an important role in the development of the road network. Like the camps in Vindobona and Arrabona , it was located at the end of important highways, two of which met at Colonia Claudia Savaria and from there continued to Italy.

The Amber Road was an important trade route that connected the then inhospitable, underdeveloped northern Europe ( Baltic States ) with the old trade and craft centers in Italy on the Adriatic and the rest of the Mediterranean. It probably crossed the Danube near the Pfaffenberg , at Stopfenreuth , and reached the city limits in the southwest. From there it was identical to the so-called grave route, since since the early imperial era graves were preferred to be laid outside of the settlement area. It then ran along the west bank of Lake Neusiedl and connected Carnuntum with the nearest town of Scarbantia ( Sopron ), as found in milestones near Oslip and Bruck an der Leitha attest.

The Limes Road (via iuxta Danuvium) connected Gaul and the Rhine provinces with the middle and lower Danube and subsequently with the Greek east of the empire. There are different assumptions about their course. In the direction of Vienna it probably followed the bank of the Danube. It is unclear whether a road down the Danube, in the direction of Fort Gerulata / Rusovce, also belonged to the main strand of the Limes Road or whether it led directly out of the south gate and then continued to the southeast. About 150 meters south of the railway line, a junction from the Limes road was discovered. It led through the depression of the Altenburg brook to Prellenkirchen and from there to the forts of Gerulata and Ad Flexum ( Mosonmagyaróvár ). A second led at right angles to Gräberstrasse and then to Hundsheim and Edelstal . Parcel and field boundaries are still based on their route. Presumably it has existed since the 1st century AD.

Ceramic finds on the territory of Slovakia suggest that Carnuntum was also directly connected to the Waag valley area by a road . Their route probably led over the eastern slopes of the Little Carpathians from the Danube crossing near Bratislava to Trnava .

The west-east camp road is largely identical to the course of the federal highway 9. Its north-south counterpart continued - with the exception of its north side - also outside the camp. To the east it runs parallel to today's federal road to the outskirts of Deutsch-Altenburg. There, however, their traces are lost because of the dense development. It probably led over the Kirchberg to the foot of the Pfaffenberg and from there to the mouth of the March .

Research history

The remains of the legionary camp are likely to have been clearly visible until the 15th century. In 1668, the court librarian of Emperor Leopold I , Peter Lambeck (1628–1680), reported on “… old masons standing high above the earth, the collapsed vault, or the old cellar, the four portals and crossroads.” The areas of the camp, which stood directly on the steep bank of the Danube, fell into the river through erosion over the centuries. Due to the river regulation at the end of the 19th century, these landslides have largely come to a standstill. In contrast to most of the other legionary locations on the Rhine and Danube Limes, the Carnuntine camp is a completely unobstructed ground monument. Its area was used exclusively for agriculture and offers ideal conditions for large-scale archaeological prospecting projects such as geophysical measurements and, in particular, aerial archaeological investigations. Since the 1960s, the aerial photo archive of the Institute for Prehistory and Protohistory at the University of Vienna has had more than 1,500 vertical and oblique photographs from the Carnuntum region. Their evaluation yielded a large amount of information on the ancient buildings and infrastructure of the camp city. If you bring all the excavation and prospecting results together, you get a very detailed overall plan of the legion camp and the canabae legionis . The barracks, the central building principia (staff building), praetorium (accommodation of the legionary legate), the valetudinarium (camp hospital), three of the six tribune houses (officers' quarters) and three larger farm buildings in the eastern half of the camp were almost completely excavated .

18th century

Until the late 18th century, the ruins of the "heydnian [n] Statt" were torn down by the peasants as they hindered field work. The stones were reused as building material, the marble burned to lime. The officer and scholar Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli (1658–1730) made a rough sketch of the legionary camp for his work Danubius pannonico-Mysicus in 1726 . During this time there were obviously still larger, coherent remains of the wall of the camp, which were popularly known as "The old castle". The east gate in particular should have been relatively well preserved at that time. On the occasion of a journey through the Danube in 1736–1737, the English educational travelers Jeremiah Milles (1714–1784) and Richard Pococke (1704–1765) also paid a visit to Carnuntum and mentioned it in their travel report A description of the east and some other countries . It was u. a. also reported of numerous remains of walls, grassy hills made of bricks in the interior and a larger ruin in the center of the camp.

19th century

Around 1821, the Prague magazine Hespererus reported on farmers from Deutsch-Altenburg who were digging and breaking old bricks as a lucrative sideline and sold them "by the fathom". In the same year the numismatist and archaeologist Anton von Steinbüchel (1790-1883) initiated the first targeted excavations, but this was only a one-man business. Interest in further research into Carnuntum awoke with a report by the art historian Eduard von Sacken (1825–1883), with which he informed the Austro-Hungarian Central Commission about the discovery of Mithräums I during blasting work on the Pfaffenberg. Sacken had the finds recovered with great care and brought to the cabinet of antiquities in Vienna. When Roman inscriptions were found in the quarry of Deutsch-Altenburg in 1852, the first excavations began, but were still mainly limited to collecting ancient finds. The exposed walls (military bath) were filled in again. In the same year Sacken reported that not a single remnant of the wall of the legionary camp was visible above ground. From 1877 systematic archaeological investigations began under the ancient historian Otto Hirschfeld (1843-1922), which initially concentrated on the legionary camp and to a lesser extent on the canabae legionis and lasted (with brief interruptions) until the outbreak of the First World War. 4/5 of the camp could be exposed. In 1884, under the patronage of Crown Prince Rudolf von Habsburg, the Carnuntum Association was founded with the aim of promoting the scientific investigation of local ancient sites. In 1885 the curator Alois Hauser (1841-1896) and in 1908 the archaeologist Maximilian von Groller-Mildensee (1838-1920) dug in the legion camp and on the Pfaffenberg. In 1888, the amphitheater of the camp city (Amphitheater I) was discovered in a depression next to the legionary camp. It was uncovered by Hauser by 1896. Archaeological research into the Roman aqueduct on the Solafield south of the Canabae began in the 1890s. Between 1885 and 1894, the cemetery on Bernsteinstrasse west of the legion camp of Groller-Mildensee was uncovered. Eugen Bormann entered the positions of the individual graves on a cadastral map. In August 1894 the building researcher Josef Dell (1859–1945) and Carl Tragau († 1908) examined the Mithraeum III. In the same year the KK Archaeological Institute was established. From then on, this and the Limes Commission attached to the Austrian Academy of Sciences were in charge of research into Carnuntum.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, Groller-Mildensee examined the area south of the theater, the buildings of which were oriented towards the Limesstrasse. In 1904, the Carnuntinum Museum was opened to present the increasing number of finds in Bad Deutsch-Altenburg . In the subsequent excavation campaigns, the archaeologist Eduard Novotny (1862–1935) was able to uncover a large part of the legionary camp by 1914, so that it was possible to reconstruct its structure and structure. Between 1913 and 1914, the director of the Carnuntinum Museum at the time, Josef Bortlik, organized another large-scale excavation campaign along Gräberstrasse in order to keep the finds of the last unplundered graves safe from treasure graves. Since the 1950s, land consolidations, the expansion of infrastructure, large-scale material mining, the industrialization of agriculture, etc. have led to the destruction of large areas of found land. All these circumstances made rescue excavations necessary, which were, however, under great time pressure. The last excavations in the legionary camp were carried out between 1968 and 1977 by the Austrian Academy of Sciences in cooperation with the Austrian Archaeological Institute . They enabled the (still valid) periodization of the legionary camp and provided essential knowledge about the wood-earth and the late antique stone camp. The eastern part of the praetentura (northern part) of the camp has remained largely unexplored to this day. In 1977 on the eastern outskirts of Petronell-Carnuntum the trench of the equestrian camp was cut during the construction of a housing estate (the so-called Schneider settlement). In 1978 the archaeological excavations began under the direction of Herma Stiglitz . However, some sections of the fort were irretrievably lost due to the overbuilding. In order to save the remainder, the castle grounds were placed under monument protection by the Austrian Federal Monuments Office. Up to 1988 it was possible to examine the western half of the area in particular, partly with search cuts, but also over a large area. The function, the four construction periods and the dimensions of the cavalry camp could be determined. In addition to the fortifications, a number of the internal structures from the different construction periods were also examined. After Stiglitz retired in 1989, Manfred Kandler was entrusted with continuing the excavation work. He also included the southern apron of the fort in his investigations. Mainly tools, weapon parts and cooking utensils and dishes were discovered in the cavalry fort. Some of the most notable finds include the face mask of a rider's helmet and a parade helmet that was used in tournaments. The stone monuments from this excavation area can be viewed in the lapidarium of the cultural center in the municipality of Petronell-Carnuntum. The ruins and finds of the temple area on the Pfaffenberg were documented before their final destruction in the period from 1970 to 1985 by rescue excavations carried out by the University of Vienna and thus saved for posterity.

21st century

Up until 2004, the Austrian Archaeological Institute was able to use rescue excavations to examine large sections of the Reiterkastell before the modern development was completed and save them from final destruction. In 2012 the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archeology started the project “ArchPro Carnuntum” in cooperation with other partner organizations, which was commissioned by the State of Lower Austria. Through the systematic use of non-invasive archaeological prospecting methods (remote sensing and geophysics), the researchers mapped most of Carnuntum with high-resolution measurements. Within three years they were able to examine an area of around 10 km² across the board. With the help of aerial photographs, a preliminary overall plan of the ancient remains hidden in the ground was drawn up by 2013. The archaeological structures extend over several square kilometers and show, among other things, a dense development on the area of the canabae and structures of the water supply. With the help of the results of the old excavations and a reassessment of the current state of research, a scale model of the Roman Carnuntum was produced. The research in the legionary camp has come to a complete standstill due to the current negative attitude of the landowner.

development

The development of the two forts and the camp town was closely related to the constant defensive battles against the Germanic tribes on the other side of the Danube, which required the permanent stationing of a large number of soldiers. As a result of this, the section of the border near Carnuntum repeatedly moved into the focus of imperial politics, which can be seen particularly in the frequency of the presence of important Roman emperors and generals in the city.

1st century BC Chr.

In the 40s of the 1st century BC The Boier were subjugated by their eastern neighbors, the Dacians under Burebista , who also burned their large oppidum near today's Bratislava . After this defeat, the now largely abandoned Boian territory ( deserta Boiorum , roughly today's Vienna Basin and Burgenland ) fell to the Noriker . Their settlement areas also belonged to the Kingdom of Norikum (regnum Noricum) at the end of the first century BC . 15 BC The Kingdom of Norikum was integrated into the Roman Empire as one of the few new areas of the empire without a violent conquest.

1st century AD

In the Roman written sources Carnuntum was mentioned for the first time in connection with war events before the Pannonian-Dalmatian uprising (bellum dalmaticum) , an uprising of the indigenous tribes against Roman rule, from 6–9 AD. According to the chronicler Velleius Paterculus , a 40,000-strong Roman army under their general Tiberius set up a temporary winter camp (castra hiberna) in order to a. to subjugate the Marcomanni under their king Marbod , which north of the Danube u. a. settled in the area of today's Bohemia and Moravia . The location of this camp has not yet been localized; it was either near Hainburg , on Bratislava Castle Hill or at the mouth of the March . Pliny wrote of the layout of the camp in the "Germanic border area"; so Carnuntum was not yet officially part of the Roman Empire at that time.

The consolidation of Roman rule encountered far greater difficulties in Pannonia than in the neighboring Norikum. Marbod endangered the Roman expansion into Central Germany, as he had a force of 70,000 men, drilled on the Roman model (including 4,000 horsemen). Emperor Augustus therefore gathered twelve legions (80,000 men) on the Rhine and Danube and subordinated them to his stepson Tiberius. He was to cross the Danube at Carnuntum with six legions and advance further north along the March. At the same time the second army group marched from Mogontiacum / Mainz under the leadership of Sentius Saturninus to the east in order to pinch the Marcomanni. The Pannonian rebellion, presumably instigated by Marbod, ultimately thwarted the further advance of Rome into free Germania. Tiberius, who had already reached the far north, as far as today's Weinviertel , had to turn back immediately, not only to put down the uprising, but also to prevent him from being cut off from his supplies from Italy. Despite the large number of troops, the Pannonians could only be subdued after three years. After the loss of three legions in the Teutoburg Forest , Augustus finally renounced further expeditions of conquest into the Germanic tribal areas and established the imperial border on the rivers Rhine and Danube.

By 8 AD at the latest, the region around Carnuntum should have been incorporated into the Roman Empire. After Augustus' death, unrest broke out in the summer camp (castra aestiva) of the legions ( Legio VIIII Hispana , Legio XV Apollinaris and Legio VIII Augusta ) stationed in Pannonia in the summer of 14 AD . Drusus the Younger was able to calm down the angry soldiers quickly, whereupon they moved to their winter quarters according to the orders. Inner Germanic disputes caused Marbod, defeated by Arminius , with his entourage to ask for asylum in the Roman Empire in 19 . He was followed a little later by his adversaries Catualda and the quadruple ruler Vannius (regnum Vanianum) , who were settled in the Leithagebirge. Under Emperor Nero (54 to 68 AD) the province of Pannonia was formed from the north of Illyria, to which Carnuntum was now added. Initially, Roman troops were only stationed at particularly endangered points on the new border line. The main defenses in Upper Pannonia were opposite the mouth of the March and on the border between Vindobona (Vienna) and Brigetio (Komarom). At no border section of the Roman Empire was there such a strong concentration of troops. During the reign of Claudius , according to the historian Tacitus, the construction of permanent military camps and watchtowers along the Danube began to secure the new border. The oldest traces of Roman settlement were found for the period between 40 and 50 AD (finds from Upper Italian Terra Sigillata ), when the Legio XV was permanently stationed on the Danube in connection with the expulsion of Vannius and its second camp after Vindobona in Carnuntum related to the Pannonian Limes (corridor at Burgfeld). During this period of time the ancient Celtic oppida were also abandoned; the subjugated indigenous population ( dedictii ) was settled in the plain around the new legionary camp for better control. The earliest known inscription from Carnuntum (53 or 54 AD) reports on construction work in the legionary camp. At the same time, a settlement ( canabae legionis) consisting of irregularly laid out simple dwellings developed around the camp, leaving out a free area for the assembly of the army . On a grave stele, which was made around the middle of the 1st century, a Roman soldier is shown supervising a Celtic carter. This suggests that the local population was also increasingly involved in the numerous construction projects during this period.

Since Augustus' policy of conquest was rejected by his successors, the Flavian emperors began to set up a border security organization. Under Vespasian (69–79) the wood and earth camp was replaced by a stone building. The western flank of Carnuntum was protected by the legionary camp in Vindobona. Under his successor Domitian , a fort for a cavalry unit of 500 men was built about 1.2 kilometers southwest of the camp . It should ensure greater mobility of the troops in border surveillance. Between 85 and 86 the Romans suffered a defeat against the Dacians . The fighting subsequently spread to the region around Carnuntum. Domitian therefore felt compelled to appear personally in Pannonia in order to coordinate the defensive measures. During a campaign against Marcomanni and Quadi in the years 89 and 90 , the emperor was probably also in Carnuntum. On his orders, further troops were moved to Pannonia to reinforce the Danube army, for which new forts also had to be built. The cavalry camp should also have belonged to this. In 97 the war, the so-called bellum Germanicum et Sarmaticum , ended with a victory for the Romans.

2nd century

In 106 or 117 one of the Rhine legions, Legio XIIII , was moved from Vindobona to Carnuntum by order of Trajan, where it remained stationed until the end of Roman rule over Upper Pannonia. The expansion of the legionary camp was completed under Trajan. Between 110 and 120 there were also fundamental innovations in the area of the Reiterkastell. The changes there may also have been related to a change in crew. After the demolition of the old wood and earth fort, the Thracian cavalry unit built a stone camp at the same place. Due to increased immigration, encouraged by the presence of the Legion, which guaranteed the highest level of security, and stable economic growth, Carnuntum continued to grow steadily in the course of the 2nd century. An additional driving force behind the rapid development of the military city was the extremely lucrative long-distance trade with free Germania.

After the province was divided into two in Upper Pannonia and Lower Pannonia under Trajan , Carnuntum became the official seat of the consular governor (legatus Augusti pro praetore provinciae Pannoniae) between 103 and 107 , to which all Upper Pannonian legions were subordinate from then on. In order to be able to repel attacks by the Germanic tribes better, outposts on the Marchtalstrasse in Stampfen and Thebes were established north of the Danube, opposite Carnuntum, as part of an early warning system. The devastating for the Roman Empire Marcomannic wars in the 160's and 170 years ended abruptly the hitherto steady upward trend Carnuntum. The invasion of 6000 warriors from a coalition of Lombards, Marcomanni and Obiern could still be repulsed by the Upper Pannonian governor. In 167, however, a campaign against some Trans-Danubian Germanic tribes (Marcomanni, Quadi, Narist and other small peoples) failed. The Limes was then stormed and breached by them. Up to 20,000 Roman soldiers and the governor are said to have died while trying to repel them. This catastrophe was made worse by the outbreak of the Antonine Plague , brought in by a Roman army returning from the east, which decimated soldiers and civilians in the Limes. The intruders advanced to Aquileia in northern Italy. However, when they returned to the Limes with their booty, the Roman forces were waiting for them there. After bitter fighting, the invaders succeeded in stealing most of the loot and pushing them back across the Danube. In the course of the Roman counter-offensive to the devastation of the Germanic tribal areas north of the Danube, Emperor Mark Aurel opened his headquarters in Carnuntum for three years (171–173) and wrote some chapters of his self- reflections there before his death in 180 . The reliefs of the Marcus Aurelius column in Rome show some details from the Carnuntum of that time. During this campaign the Romans penetrated far into free Germania as u. a. Brick stamps of the Legio XIIII, which were found near Staré Město and Hradischt, 120 km north of Carnuntum, attest. The legionaries must have set up a checkpoint there on Bernsteinstrasse.

Surprisingly, during the excavations in Carnuntum, no greater horizon of destruction could be proven archaeologically for this period of time. The legionary camp and cavalry fort was also continuously occupied in the second half of the 2nd century and by no means, as initially assumed, was destroyed in the fighting. The cavalry camp now served as an advanced supply and supply warehouse for the front and was then also equipped with workshops and warehouses. Marcus Aurel's successor, Emperor Commodus (180–192), finally concluded a peace treaty with the Germanic peoples and was probably also in Carnuntum for this purpose. The peace treaty was followed by a period of stability and reconstruction in the Pannonian provinces, during which, among other things, the amphitheater of the camp town was rebuilt in Stein. The most important historical event for Carnuntum took place on April 9, 193. The incumbent Upper Pannonian governor Septimius Severus (193–211) was proclaimed by the Danube regions as counter-emperor to Didius Julianus and later also confirmed by the Senate in Rome. He founded the ruling house of Severus , which brought the empire another massive military and political upswing.

3rd century

Septimius Severus proved to be a generous patron of Pannonia and raised the civil city to the rank of Colonia (Colonia Septimia Aurelia Antoniniana Carnuntum) . This made it the most important city in Pannonia superior . The result was another intensive construction activity lasting several decades. Under the Severans (193–235) the location reached its economic / cultural heyday and maximum expansion. Only riders were stationed in the auxiliary troop camp again.

The last decades of the 3rd century were marked by internal unrest, constant defensive battles against invaders and rapidly changing rulers on the imperial throne (so-called imperial crisis of the 3rd century ). Carnuntum remained an important base on the central Danube Limes. In 260, during the reign of Gallienus (253-268), the Carnuntine troops proclaimed the governor of Pannonia superior, Regalianus , to be anti-emperor; but he was not recognized by the Senate in Rome. His influence never grew beyond the Limes strip between Carnuntum and Brigetio. During his brief reign he had coins minted with his image and that of his wife Sulpicia Dryantilla, some of which were found in Carnuntum. Six months later, both were murdered by their own soldiers. Towards the end of the 3rd century, the cavalry fort was given up - probably as a result of the military reforms carried out under Gallienus. The legion riders previously stationed at the Limes were brought together at Mediolanum (Milan) to form a powerful cavalry army. In the event of a crisis, it was supposed to operate as a rapid reaction force directly subordinate to the emperor, was a forerunner of the later mobile comitatenses (mobile field armies) and initially consisted primarily of Illyrian (Pannonia, Moesia and Dacia) and Moorish (North Africa) units. Presumably the riders of the Carnuntine Legion were also assigned to her. With Diocletian's accession to power in 284 the long period of instability among the soldier emperors ended . In 288 he stayed on the Danube Limes and had the fortifications reinforced with new camps, small forts and Ländeburgi or the old fortifications modernized. Upper and Lower Pannonia have now been split into four administrative units. In 295 Carnuntum was the starting point of a campaign by Caesar Galerius against the Marcomanni.

4th century

The political conflicts between his successors after his abdication prompted Diocletian, who wanted to prevent the collapse of his system of rule, to convene a meeting of all parties to the dispute in Carnuntum in 308 in order to settle the conflicts peacefully and to revive the tetrarchy. With this conference within its walls, Carnuntum once again moved into the center of imperial politics. The city was probably chosen as a venue for the appropriate accommodation of the delegates because of its location near the border between the western and eastern parts of the empire and also because of its representative buildings and well-developed infrastructure. In this historically significant meeting, the Augusti Diocletian, Galerius , Licinius and Maximinus Daia succeeded in putting the distribution of power in the Roman Empire on a new stable basis (so-called fourth tetrarchy ). On the occasion of the restoration of a Mithras shrine (Mithraeum III), the participants donated an altar, which is now kept in the Museum Carnuntinum .

During this time, however, more and more soldiers were withdrawn from their old garrison types on the Limes and lined up in newly established mobile field armies ( Comitatenses ) to protect the heartlands of the Western Roman Empire . The stationary border troops ( Limitanei ) of Ufernorikum and Pannonia I were now under the command of a Dux limites . In the middle of the 4th century (350) Carnuntum was shaken by a severe earthquake, which caused considerable damage to the infrastructure and can be archaeologically proven (especially in the Canabae) by layers of destruction on the large public buildings. A large part of the civilian population probably emigrated as a result of this catastrophe and because the climate began to deteriorate in the late 4th century. Due to the progressive impoverishment of the provincial population through the continuous withdrawal of soldiers, trade and the circulation of money were also severely impaired. Am Limes came with the beginning of the Great Migration also increasingly to attacks and looting of the East, which in turn in front of the ever expanding westward through the herandrängende nomadic tribes Huns were forced to flee and would thus force their settlement in the Roman Empire.

Under Valentinian I, Carnuntum was once again the starting point for a campaign of revenge against the Quads and Jazygens in 374 . He probably also had the last verifiable modifications made to the legionary camp. It was u. a. a useless sewer in the northern part of the camp was quickly filled with spoil . On the orders of this ruler, extensive construction work was carried out on the rest of the Danube Limes, which were to modernize the already largely dilapidated fortification system and thus compensate for the endemic shortage of soldiers. How urgently the forts on the Limes needed such revitalization measures can be guessed from a passage in the writings of Ammianus Marcellinus . Although it was still of great strategic importance, the emperor found the city on his arrival as a "neglected, dirty nest" and largely deserted. In the last decades of the 4th century, however, extensive construction activities can still be demonstrated both in the civil town and in the legion camp, which is no longer used exclusively for military purposes. For the greatly reduced occupation - as was often observed on the Danube Limes - two small fortifications (remaining fort or burgi ) were probably built. Large parts of the former settlement area were abandoned and only used as a cemetery.

After the catastrophic defeat of the Eastern Roman army against a barbarian coalition in the Battle of Adrianople in 378, Huns, Alans and Goths invaded the empire unhindered and finally had to be recognized by Rome as federates or granted the right to settle in Thrace. By 380 the Ostrogoths and Alans reached Pannonia under Alatheus and Safrac and were enlisted in the provincial army there. In the year 395 the Pannonian Limes collapsed on a broad front; the unfortified civilian settlements were largely abandoned. The residents of Carnuntum at that time withdrew either to the legionary camp, to the Forum thermal baths (palace ruins) or to quarters of the civil town that were still habitable. The patrol ships and Liburnari of Legio XIIII were moved to neighboring Vindobona. In the same year the Marcomanni, Quads, Goths, Alans and Vandals invaded Pannonia without encountering any resistance worth mentioning, but presumably spared the city. In the following year, 396, at the instigation of the regent in the west, Stilicho , the Marcomanni were settled to defend the Limes between Carnuntum and Klosterneuburg . These Marcomannic auxiliary troops appear in the Notitia dignitatum under the command of a tribunus gentis Marcomannorum . Presumably they were also involved in the last major construction work in the legionary camp.

5th to 11th centuries

Until the early 5th century, Westrom managed to maintain its upper and middle Danube border with great effort. According to the Notitia Dignitatum, a Praefectus still resided there around the middle of the 5th century, who had a cohort of the Legio XIIII and some naval soldiers under his command. The last traces of Roman settlement could be observed in Carnuntum until the first half of the 5th century. They were concentrated in the legionary camp, where the rest of the Romanesque civilian population had meanwhile withdrawn. In 433 AD the Pannonian provinces were founded by Valentinian III. left to the administration of the Huns under Attila . The Carnuntum metropolitan area remained inhabited throughout the migration period. Two years after Attila's death, Emperor Avitus tried to return Pannonia to the imperial union, but failed due to the resistance of the Goths, who now ruled the province. After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the settlement in the former legionary camp was finally abandoned. The Lombards and Avars occupied the country between 546 and 568 . Remarkably, there are no finds from the interior of the camp, either from the Lombards or from the Avar rule. In the early 9th century Carnuntum marked the northernmost end point of an Avarenkhaganat . Carnuntum was last mentioned in 805 in the Annales regni Francorum . After that, it was forgotten. At the same time as a large early medieval ramparts on the Kirchenberg near Bad Deutsch-Altenburg existed during the 9th / 10th. For a short period of time, a smaller settlement was built inside the legionary camp. Since the Carolingian period , some farming families have probably settled in the core of the former camp town. At the turn of the millennium there was a small village here, but the name is unknown. The focus of the settlement finally shifted eastward to Hainburg an der Donau around the middle of the 11th century . The legion camp and the civilian settlements were destroyed by systematic stone robberies in the centuries that followed.

| 3d plan of the military city |

|---|

| Website Roman city Carnuntum |

|

Link to the picture |

Legion camp

The legionary camp (castra legionis) stood on the outskirts of Petronell, on the area between Bundesstraße 9 and the bank of the Danube. The history of the warehouse can essentially be narrowed down to one wood-earth and two stone phases. During the excavations, however, a total of up to eight find layers could be distinguished from one another. The medieval stone fort was built on the same site as the earlier wood and earth warehouse. Its diamond-like, irregular floor plan was a result of the topographical features of the plateau. Rock ribs on the steep slope of the Danube made it possible for the camp to be built very close to the banks of the Danube. From here you had a good view of the Marchfeld. While the camp in nearby Brigetio had to be relocated a little away from the Danube bank due to erosion in Hadrianic times, the north side of the Carnuntine camp seems to have remained stable throughout its use phase. On the other three sides there were hollows and depressions in places, to which the course of the wall had to be adapted. The west side buckled inwards in the gate area. In contrast, the east wall bulged far outwards and receded sharply inwards in the gate area.

The camp could hold up to 6000 men (miles legionis) . Its interior development included the headquarters (principia) , the camp commandant's house (praetorium) , the hospital (valetudinarium) , the camp bath (thermae) , barracks (contubernien) , workshop building (fabrica) and storage building (horrea) . After countless broken glass was found, at least these buildings were probably fitted with glazed windows. The archaeologists also uncovered a massive layer of destruction that could be dated to the end of the 4th century. After the excavations, it was filled in again because its area is used for agriculture. Its remains stand out from their surroundings as a clearly recognizable plateau with the surrounding depressions of the fortification trenches. Above ground, only small remains of the wall of the fence at the east gate and the foundations of its southern flank tower, which are heavily overgrown by vegetation, can be seen.

Wood-earth warehouse

Little is known of the early wood-earth camp (period I). Its traces could only be proven in a few places of the completely excavated successor building of the 2nd and 3rd centuries. It was probably built between 40 or 50 AD and measured 195 × 178 meters including the moat. The fortifications consisted of an inner, about five meters wide, earth wall serving as a battlement and an outer wooden plank wall with vertically embedded beams and wooden towers on four posts. A double pointed ditch six meters wide ran around the camp. The inner walls had been raised with the excavation of the trenches and served as battlements. Not much is known of its interior construction either. Most of the warehouse buildings were probably still built using truss technology. Since the oldest findings were not exposed over a large area and the ancient buildings left severe damage, it was impossible to reconstruct coherent floor plans. Only in the northern area could traces of a barracks barracks about four meters wide and running from north to south be found. A few signs of construction were also observed in the southern storage area. It is assumed that during the reign of Vespasian the Principia, the Praetorium and the camp thermal baths, which were presumably located to the east of the via Praetoria, were already built in stone.

Steinlager I

From the 1970s onwards, the camp was gradually rebuilt in Stein (Period II). These building measures confirm several building inscriptions uncovered in the center of the camp. It was in the same place as its predecessor, but its plan was slightly shifted to the northeast. Two major building periods and several smaller building phases were identified for the stone warehouse. The fortification measured 207 × 177 meters and covered an area of approximately 17.5 hectares. At the time of Trajan, the wood-earth wall in the east and west was replaced by a stone wall. Numerous centurion stones were also built into the camp wall. The building blocks were labeled, which marked the construction lots assigned to the individual Centuries and gave the names of the officer responsible and the legion. The camp was renovated several times afterwards, but its basic features remained intact until the beginning of the rule of the Severan imperial dynasty. Around the year 200 extensive changes were made to the site plan, but these were probably limited to the praetentura (front). The newly built barracks were no longer based on the floor plans of the wooden previous buildings. Between 260 and 270 the camp was badly damaged in barbarian invasions.

Stone Camp II

Under Valentinian I, significant changes were made to the building structure of the legionary fortress from 375 onwards, as evidenced by a late antique building inscription from the western Raetentura and the excavation findings. On the west side of the raetentura , next to the hospital or prison, a small or remnant fort was built after 380, into which the guards who remained in the camp retreated. Presumably a similar weir system ( burgus ) was built on the Danube Abortion . Furthermore, there were also a noticeable number of spoils in the masonry of this construction phase. The rest of the camp area was left to the civilian population. In the eastern praetentura , three to four-room houses were built using dry construction technology and demonstrated with hose heating. Significant structural changes were also made to some of the tribune houses.

Baking ovens, pottery ovens, some building structures that could probably be interpreted as cisterns, and other, albeit no longer interpretable, findings were uncovered throughout the camp. In the majority of the cases it was likely to have been a matter of late antique fixtures. During the excavations in the praetentura (eastern part) a large early medieval oven came to light, which was built in the last settlement phase, in the 9th or 10th century.

The very simply designed new buildings of the post-military settlement phase, which began at the beginning of the 5th century, consisted only of wood, earth and clay and were no longer based on the old building regulations that corresponded to military requirements. With the departure of the last regular soldiers, presumably around the middle of the 5th century, the camp finally lost its original function. In the early Middle Ages, a group of Slavs settled within its walls . Judging by the pottery finds, its area was still inhabited into the 9th or 10th century. It was then abandoned and over the centuries it was torn down by stone robbery until it was almost completely gone.

Wall and moat

As already mentioned, the wall was drawn in somewhat in the west towards the camp gate and swung in wide arches on both sides in the east in front of the camp gate there. The only straight line was the south wall running from the acute-angled south corner. The course of the north wall is largely unknown.

In phase 1 the wall was 1.10 to 1.20 meters thick, in phase 2 it was 1.90 to 3.40 meters with much deeper and more massive foundations. The rising masonry was still up to 1.25 meters high in some places. Its core consisted of mortared rubble stones, the outer sides were faced with carefully cut stone blocks. In phase 2 it was later widened in places on the outside or completely rebuilt in some places. At the top it was most likely finished with a crenellated wreath . An approx. 25 meter wide strip of the northern front of the camp has slipped into the Danube or has sunk. At the northeast corner there was still a remnant of the wall, which was supported by a buttress. There the fort wall had a width of two meters and was directly against the barracks. The fort was protected on its north, east and west side by a 20 meter wide ditch and in the south by two ditches whose profiles were designed differently. The outside was rather flat, 12.50 meters wide, the inside narrow with a steep slope and measured only 5.40 meters. The width of the berm was 0.90 to 4.50 meters. The inner ditch may have been filled in again later. The appearance of the defenses in the late antique building period is not sufficiently clarified. During this time, however, the imperial wall in the NE was apparently additionally reinforced by an extension attached to the outside. What is certain is that the double trench system was still maintained at this time, as indicated by the filling of the outer trench with a coin from 310-311, which dates back to the middle third of the 4th century.

Intermediate towers

The wall was reinforced with square, irregularly spaced intermediate towers, six of which have been archaeologically proven in the south. Five are known in the east, only one was found in the west. One of the corner towers could be excavated in the southeast. Presumably such a tower was also present in the southwest corner. Wall thickness and side length were measured differently in some specimens.

Gates

The legionary fortress could be entered through four gates of different sizes in the north, south, west and east. Three of the four camp gates were dug. The east and west gates were built on the deepest cuts in the plateau. All were flanked by two slightly projecting towers and had double passages. Some of the facades of the gate systems were richly decorated with architectural elements.

| Illustration | Gate structures | Description / condition |

|---|---|---|

| Porta praetoria | Nothing was left of the north gate, as it fell into the Danube due to the centuries-long washout of the bank area. | |

| Porta decumana | The two-phase south gate was eight meters wide, in the middle there was an approximately one meter wide supporting pillar (spina) . The eastern, two-storey flank tower measured 6.8 × 6.6 meters. The foundations of the west were still preserved. The two passages were each 3.75 meters wide. In phase 2 the gate towers were enlarged a little, the support pillars were extended to five meters. | |

| Porta principalis dextra | Probably the main gate of the legionary camp. It could be defended well by the camp wall protruding far on both sides. The foundations of the southern flank tower (7 × 9 meters) were uncovered from this 13 meter wide gate structure. He jumped about 2.80 meters from the camp wall. Evidence of a central pillar showed that the gate could be passed through two passages. | |

| Porta principalis sinistra | Its last remains were destroyed in the early 18th century by road construction and subsequent stone robbery. The rising masonry consisted of rectangular blocks, which were connected to one another by iron clips cast in lead. On the outside of one of the blocks, an oversized phallic symbol was carved to ward off demons. The facade decoration consisted u. a. of capitals and cornices in Corinthian style. In 1898, only the southern flank tower of the multi-phase west gate could initially be located. He measured 8.8 × 7.5 meters and jumped 1.37 meters inwards or 2.50 meters in front of the camp wall. In 1899 the northern flank tower was found. The north tower of phase 1 had a circumference of 7.40 × 9 meters. In phase 2 it was no longer rectangular, but rounded at the southwest corner. The floors inside consisted of brick panels. Large amounts of broken dishes were found in the corners between the flank towers and the camp wall. Although no central pillar could be found, it is believed that the gate system also had two passages. The total width of the gate was 15.40 meters. A building inscription from the time of Emperor Valentinian I, a fragment of which was found near the gate, testifies to the last construction work in the camp. | |

| Failure gate | Not far north of the west gate, during the excavations, an underground vault with several manholes in front of the barracks was found. The archaeologists initially thought it was a canal. When you followed its course further, you came to a cross passage that ended directly behind the foundation of the camp wall. From there a passage under the wall led to the glacis. It probably served as a kind of hatch for crew failures during sieges. The gate was on his discovery by cast masonry blocks and spoils barricaded. However, the stones were only carefully piled up but not mortared together. |

Interior constructions

Command building

In the center of the camp, south of the via principalis , was the command or staff building (60 × 90 meters), the Principia , with the flag shrine (aedes) and various administrative and assembly rooms (officia) , which had only been superficially researched . Based on the model of a forum, it was laid out around a 42 × 38 meter square paved with sandstone slabs. Around it ran a colonnade (porticus) , which was provided with a channel for the rainwater to run off. In one of the corners of the courtyard a round walled well shaft and a stone relief depicting an archer were found. From the portico one could enter numerous chambers that were probably used as administrative rooms and armamenta or similar.

To the south of it stood the 16-meter-wide transverse hall (basilica) , the facade of which was set in front of 12 pilasters . It is no longer possible to precisely reconstruct what its south facade looked like. It probably consisted of several arched passages that were lined up and flanked by columns. The three-quarter pillars may once have been up to 11 meters high and stood 1.30 meters apart. The distance between the two central pillars was 3 meters. There was probably a slightly higher arch or the main entrance to the transept here. It was exactly in the axis of the courtyard entrance that led out to via Pricipales . Of the central pillars that supported the roof structure, the remains of five copies were still present during the excavations.

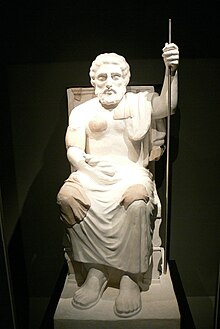

The 10 × 10 meter, heated camp shrine (sacellum) was located exactly in the central axis of the basilica. The most famous ancient stone sculptures of Carnuntum were found between the hypocaust pillars. One of the consecration altars was dedicated to the patron god ( genius ) of the camp. The sculptures mostly depicted gods or emperors. Some of the rooms were also decorated with wall paintings. The excavators were able to uncover two more rooms to the west and east of the Sacellum. The eastern one contained the statue of Hercules, believed to have been made in Virunum . The second room, to the west and a little lower from the floor level, was preserved up to the window approaches. The wall painting represented u. a. a sacrificial servant clad in a white tunic and contained an altar for Iuppiter and one for the camp genius. In the vestibule of the camp shrine there was also a fragment of a statue from the 3rd century, which probably represented a ruling couple. Maybe Alexander Severus and his mother Julia Mamaea .

Praetorium

The representative, 70 × 58 meter residential building ( peristyle house ) of the legionary legate was attached to the principia in the south . Presumably the high representatives of the empire were also accommodated there when they were in the camp. This building, too, has only been researched very superficially. The rooms were grouped around a 48.70 × 27.60 meter courtyard. In the east wing there were probably the living quarters and a bathing area. The legate's office or representative rooms were probably housed in the other rooms. Due to the high degree of destruction of the building, details could no longer be determined.

Tribune houses

North of via Principalis, near the west gate, were the three spacious peristyle houses of the tribunes (staff officers), the most senior officers of the Legion after the camp commandant and his deputy, the Praefectus castrorum . This section of the camp area was called scamnun tribunorum . It has been little examined. There were possibly three other officers' quarters there. The buildings were constructed like the Praetorium but were somewhat smaller (40 × 40 meters, around 1200-1300 square meters). The inner courtyards were paved with stone slabs. One of them was covered with a 1.5-meter-high layer of mortar in late antiquity. The buildings were used until the 5th century and have been rebuilt several times until then. Apparently they were all similarly furnished (facade decorations, mosaic floors, marble slabs, wall paintings, bathrooms, etc.). In one of these houses one of Carnuntum's most beautiful ancient sculptures was discovered in 1886, the marble figure of the so-called dancing maenad, probably an import from Italy in the 2nd century. The tribune houses each had their own wells up to 6 m deep. Between two of the officers' houses you came across a gently sloping brick concrete pavement. Along its longitudinal axis, three cisterns with bevelled edges caught the rainwater flowing down from the roofs.

House S directly on the western wall reached up to the street front. It went through four construction periods and instead of an inner courtyard had a three-aisled portico and a bathing area. The portico was divided into small chambers with half-timbered walls in the late 4th century. The two eastern houses R and T were set back a little to the north and shielded from traffic by a series of taberna chambers. In the late 4th century, House T was demolished and not rebuilt.

Barracks

The camp had a total of 30 double barracks to accommodate its men, each with space for 160–220 soldiers. The barracks of the first cohort were lined up to the right and left of the Principia , the remaining cohorts were in quarters on the front (praetentura) of the camp on the banks of the Danube and on its rear (raetendura) . Some of the barracks on the north wall had already slipped into the Danube. The mid-imperial team quarters (period 2) consisted of double barracks, which were built with their back wall against each other. They offered space for five or six parlor communities ( contubernien , eight men each) of the common legionaries, the milites gregarii . The living rooms consisted of a 13.50 square meter bedroom (papilio) and an anteroom with 7.50 square meters (arma) . Simple fireplaces (dome stoves) were used for cooking and heating. A two-meter-wide covered walkway standing on wooden posts was attached to the street front of the building. Between the buildings there was a five-meter-wide yard with gravel pavement. The barracks of the first cohort were six meters wide in the east; further west, because of the triple room division, 8 meters. They covered an area of 120 × 100 meters. At the top there were larger buildings, consisting of five to six rooms, which served as accommodation for the centurions . The centurion houses of the barracks of the first cohort had twice as many rooms. In the rooms at the opposite end of the barracks blocks, the special forces of the Legion ( immune ) were probably quartered. During the excavations in 1885, a 1.80 × 2.50 meter cellar with a staircase was discovered under one of the barracks.

In the eastern part of the praetentura , the team barracks were also renewed as part of the last major construction work in the camp. The external appearance of the barracks remained largely unchanged. The structural changes only affected the interior structure. The division of the contubernia into an accommodation area and an anteroom was abandoned. Instead, three rooms were created through the introduction of around 1.20 m wide corridors in the vestibules. The area was used as a location for barracks until the early 4th century. At the end of the 4th century, they were partially demolished and replaced by three to four-room houses with wall and floor heating, which were no longer based on the old floor plans.

Camp hospital and animal hospital

The multi-phase, 83.50 × 79.50 meter hospital ( valetudinarium ) was located to the west of the praetorium and was by far the largest building within the legionary fort. Three rows of chambers were arranged around the inner courtyard, which served as hospital rooms, bathrooms, toilets, etc. It could be entered via a staircase with well-worn steps. The rows of chambers were separated from each other by corridors between 3.30 and 4.50 meters wide. In addition, short crossways in between ensured sufficient ventilation and lighting in the individual rooms. Some of the sickrooms were heated. The hospital kitchen was in the east wing. In the center of the building was a small sanctuary, probably for the healing gods Hygieia or Aeskulap , donated by the capsarii (paramedics) of Legio XIIII and in the middle of its western front was a podium with a staircase. Column fragments and richly structured cornice pieces testify to the lavishly designed facade of the building.

The rooms of a 56 × 27 meter building west of the hospital were arranged around a 39 × 19 meter courtyard. Perhaps the animal hospital (veterinarium) was housed there.

Storage tavern

In the northern part of the camp, the excavators came across a building whose only room was paved with bricks. The room was a little lower than street level and could be entered from the south via two steps. The east wall was still preserved in several stone layers and had a small, vaulted opening in the middle, in front of which a stone slab was set into the ground. The culvert led to a basement 1 meter lower, the floor of which was made of rammed earth. Large quantities of wall painting fragments and fragments of drinking vessels were found in the rubble of the main room. To the south of the opening were four square plinths. On two of them there were still consecration altars for Liber / Libera and Merkur / Fortuna. They were once donated by two released Greeks, Dionysius and Archelaus. Both were assistants (subadiuuam) of the highest-ranking centurion in the camp (Primus pilus) , who was also responsible for overseeing the fort's commercial operations. In the rubble we also came across two bony dice . The excavators therefore interpreted the building as a camp tavern . The opening probably served as a hatch through which full wine jugs from the cellar into the taproom.

Functional buildings

The camp also had some functional buildings east of the praetorium with farm buildings such as food and weapons stores ( horreum , armamentaria ) and workshops (fabrica) . Two multi-phase courtyard buildings right next to the praetorium were identified as workshops.

workshops

The western, building C, with 65.70 × 56.20 meters probably served as a kind of building yard and also for the storage and repair of weapons of all kinds and their accessories. Among other things, 54 slingshot balls and unlabeled consecration altars were discovered there. The pillars of the gate entrance were badly worn by cart wheels. You also came across large stacks of roof tiles, a wicker basket filled with hardened mortar and loose heaps of sand for building projects.

In the eastern building D, with a floor plan of 66.30 × 49 meters, mainly metals and bones were worked. Also in the tabernae along the main streets of the camp there were probably numerous other such workplaces. The grain store and the weapons of the late antique garrison (5th century) were probably housed in a massive warehouse on the western wall. There was certainly also its own bathing building (therme or balineum) , which was probably located between the barracks in the northern part of the area.

Weapons store

In four chambers of a warehouse that was presumably subordinate to the armorer of the fort ( custos armorum ) , a considerable amount of weapon fragments was uncovered during excavations. It was a well-stocked range of

- Shield humps and arrowheads (chamber 1),

- Lance tips (chamber 2),

- Rail armor (lorica segmentata) and helmets (chamber 3) and

- Scale armor (Lorica squamata) (Chamber 4).

In the latter, the post prints of the wooden shelves on which the tanks were stored had been preserved in the floor. Most of these weapons had been smashed or broken in ancient times. In addition to the usual team helmets, the remains of equestrian helmets richly decorated with gold, silver or bronze were also found there. In the corner of one of the chambers, the remains of a large store of leather were found, probably cowhide, some of which were dyed a dull pink or cobalt blue . The arsenal also had a heated administration or lounge area, which was illuminated with a coupled window with a stone pillar in the middle. It was the only surviving window found in the camp. All the chambers were plastered, and incised figures or figures could be seen in the plaster fragments.

Armored sheds were also found in other areas of the camp. When they were found, some of them were clumped together to form large clumps of conglomerate. Remains of the leather or linen undergarment could still be found on some. Artillery ammunition such as slingshot balls the size of a fist or head made of stone or clay could be recovered from several places in the camp (north bastion at the east gate). One of these depots contained up to 34 copies. Some had a plug hole. The sling balls at the east gate had been hand-shaped into egg-sized pieces flattened on two sides, provided with two holes, and then burned. Several times outside or inside of the camp, iron ankles consisting of four forged tips were encountered (see amphitheater).

Storage bakery with pantry

This functional building ( clibanae ) was directly connected to the weapons store. Its exceptionally wide, carefully crafted walls were still two meters high when they were discovered. A passage led from the bakery into the grain store, which still contained the remains of barley, peas and millet. The bakery was equipped with six vaulted ovens that were heated with charcoal. The rods of a sweeping broom were still in one of them. From the inventory there were still two stone troughs, a hand mill and the iron bands surrounding a baking trough, probably a hollowed-out tree trunk.

Granary

The spacious warehouse / Horreum (Building E) stood near the east gate, measured 86 × 38.50 meters and had a long rectangular floor plan. Its walls were up to 1 meter wide.

Shield factory

In contrast to the early and middle imperial period, the warehouse area was used more for workshops in the first half of the 4th century, which were built especially along the south-eastern battlement retaining wall , directly on the via sagularis . These systems consisted of at least eight round pools made of air-dried mud bricks and sealed with stone chippings, which were closely lined up and each provided with a roof. They were uncovered between 1968 and 1977 and are believed to have only been in use for a short time - around the first half of the 4th century. They were later filled up again. During the old excavations, two comparable, better preserved basins on the southern front of the camp had already come to light. They were probably used for tanning leather, which was required as a cover for a fabricae scutariae (shield factory) - mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum for Carnuntum . It was probably set up in Carnuntum from the Diocletian period (284–305 AD) to ensure the need for such protective weapons centrally for the province of Pannonia . Carnuntum is one of the few places where such facilities can be archaeologically proven. Since the demand for leather is likely to have increased enormously due to the establishment of the shield factory in Tetrarchic times, one was dependent on additional production facilities for the raw materials required. It was probably located northeast of the Praetorium. The buildings there were interpreted by the first excavators as warehouse and workshop buildings, primarily because of their floor plans. The material waste discovered there also supported this assumption. In particular in building D, which was characterized by numerous small rooms grouped around a large inner courtyard with a central water basin, evidence of workshops was found during the first excavations. In two rooms in the north, numerous pieces of sheet bronze, rivets and pieces of wire and over a hundred smaller and larger pieces of sawn deer antlers came to light.

Camp prison

To the southeast of the hospital, four consecration altars were found in a building, and a fifth lay smashed on the floor. Two were dedicated to Mercury and Nemesis. The latter was donated by the prison administrator Caius Pupilius Censorinus (ex optione custodiarium, clavicularii) in the early 3rd century. The excavators therefore interpreted the building as a prison (carcer castrorum) . Its screed floors had been renewed twice over the centuries. The room served as the administrator's office and lounge for the guards. The dungeon could be entered through a narrow door.

Warehouse streets

The axial road system of the camp was designed in such a way that the main roads led directly to the most important buildings (e.g. Principia, Praetorium, camp thermal baths). The starting point of the two main streets of the camp were the gates on Limesstraße and Bernsteinstraße. The via principalis formed the cardo and the via praetoria , which was called decumana in the rear , the decumanus . The 334-meter-long via principalis , running from northeast to southwest , roughly below today's Bundesstraße 9, ran through the narrow side of the camp. According to the remains of the foundations on the roadside, it was accompanied by colonnades on both sides. It is noticeable that it deviates by approx. 36 degrees from the east-west direction to the northeast. This deviation was not caused by the topographical conditions, but is probably a result of the alignment of the street with the rising point of the sun on the day of the summer solstice. The second main road of the camp, the via decumana , stretching from north to south , was interrupted by two buildings (principa and praetorium) . The via vicinariae in the southern section of the camp ran parallel to the via principalis . Along the camp walls there was also a rampart road that was laid out via sagularis , which established a connection to all sections of the camp and made it possible for the crew to reach the battlements quickly in the event of an alarm. At the same time, it served as a buffer zone against projectiles fired by besiegers. In many places the excavators encountered cauldron-shaped depressions in the streets, which presumably served as camouflaged pitfalls and were intended to stop attackers who had entered the camp. Most of the streets of the camp were lined with walled sewers. The main sewer emerged on the eastern front of the fort and had a barrier to prevent faeces from backing up during floods.

Water supply / sewer system

The supply of fresh water to the camp was carried out via wells, cisterns and draw wells on the main roads. But traces of underground water pipes and canal systems ( cloaca ) could also be detected on the camp area. Cables made of wooden or lead pipes were laid to the individual tapping points. At the praetorium, the principia and the tribune houses, the remains of an apparently technically very high-quality water supply and disposal system were found. The remains of the main sewers could be observed especially at the camp gates. The main canal began at the south gate and ran around the entire warehouse area in two separate strings under Wallstrasse. It was accessible through several manholes. The main entrance was also provided with stone stairs and a work platform. It drained directly into the Danube, as could be determined in 1899. Numerous secondary canals also ran into the main canal, which ran under the storage alleys and received the sewage from the house canals and rivulets. It was noteworthy that one of them had been reinforced on all sides with thick iron plates in one section.

Auxiliary fort (equestrian camp)

This fort is one of the best-researched camps on the Norico-Pannonian Limes. The auxiliary troop camp on the western edge of the camp city was able to accommodate a 500-man cavalry unit (ala quinquenaria) . The pre-Roman times of the fort area is documented by some settlement pits that may have been built around the birth of Christ. Some graves also located under the fort mark the oldest Roman horizon. This includes a tombstone destroyed during the construction of the first camp for a member of the legio XV Apollinaris whose name is unknown . He stood on the extensive burial ground that accompanied the Limes road leading to the legionary camp for a length of several kilometers. A dome furnace with a rectangular charging pit also originated in the fort area from the time it was built . Perhaps it served as an oven for the soldiers involved in the construction. A total of four construction phases could be distinguished during the excavations. When the housing estate was built, the entire fort was not destroyed. A modern overbuilding could be prevented in the area of the fort baths as well as in two sections of the southern and eastern wall.

Castle I.

The early camp was almost entirely made of wood. The front was directed against the legionary camp to the northeast. Three sides of the fort could be examined by excavations. The course of the rest of the fort wall is only known from the aerial survey. The full extension of the fort was 178 × 225 meters, so it covered a total area of around four hectares.

Defense: The fortification consisted of a double trench. His excavated material was piled up to form an earth wall, on the crown of which there was presumably a wooden palisade as a parapet. The gate, intermediate and corner towers, which were almost certainly made of wood, have not yet been archaeologically proven.

Interior development : So far, the only interior structures known are the team barracks lined up at the rear (raetendura) of the camp, the camp commandant's house (praetorium) and some sections of the command building (principia) . At the rear of the courtyard in the principia , which was presumably paved with stone slabs, five adjacent rooms were arranged, the middle of which probably served as a flag sanctuary (aedes) . In the ground there were still some iron lance shoes for the military standards (signum, vexilla) that were once set up there. A shallow pit, presumably used to store the troop coffers, was also preserved.

Water supply / sewerage: The water supply for the fort crew was probably ensured by wells. The horses must have been watered outside the camp. A few cisterns were also set up to collect rainwater. One of them was found in the courtyard of the commandant's house. The rainwater that ran off the roofs of the buildings had been drained off in shallow trough-shaped gutters that ran 0.40 meters from the walls of the house. Other such eaves were located at the rear of the barracks. The waste water then flowed into the main canal under the via sagularis (Wallstrasse). It led to the outside through one of the warehouse gates and presumably consisted of a simple wooden channel, which was also framed by architectural pieces that were used a second time.

Castle II

The warehouse had a playing card-shaped floor plan and was rotated by about 90 ° when it was rebuilt. The Praetorial Front was now oriented towards the Danube bank and aligned in the same way as the legionary camp. The storage area was reduced to 178 × 205 meters (3.65 hectares).

Enclosure: The stone wall was 0.90 meters wide, reinforced with rectangular intermediate and corner towers and also surrounded by a ditch. Of the four trapezoidal corner towers, only the one on the southeast corner could be examined. Corner and intermediate towers did not protrude beyond the line of the wall. Only the rectangular side towers of the camp gates clearly stood out from the fence. The top of the wall could be walked on on a rampart made of earth. The south-east corner was fastened with wooden planks that lay on pillars attached to the fort wall.

Interior development : Barracks, the military hospital, the officers' houses and the command building are known in the interior. Even in this period they were made entirely of wood. Sometimes air-dried clay bricks were also used as building material. Some of the buildings had pillar structures in front of them (portikus) . Their wooden supports rested on foundations made of rubble stones. The team barracks had a long rectangular floor plan and consisted of two rows of rooms standing next to each other. Two rooms each formed the accommodation for a common room (contubernia) . The front rooms of some of the barracks were used as horse stables and offered space for a maximum of three mounts. Presumably, part of the cavalry unit had to fulfill the task of a rapid reaction force, for whose deployment they had to be available to the soldiers as quickly as possible.

Therme: The only building that was built in stone masonry was the bath on the western front of the fort. The camp bath was equipped with a cold water basin, heated rooms and two hot water tubs.