Qin Shihuangdis mausoleum

| Qín Shǐhuángdìs mausoleum | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| View into the covered first pit |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | i, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference No .: | 441 |

| UNESCO region : | Asia and Pacific |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1987 (session 11) |

Location of the mausoleum within the boundaries of today's China |

The Qín Shǐhuángdìs mausoleum is an early Chinese tomb, built for the first Chinese emperor Qín Shǐhuángdì . The construction began in 246 BC. And the emperor became in 210 BC. Buried in it. It is one of the world's largest tombs and is best known for its large soldiers, the so-called " Terracotta Army".

The mausoleum has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1987 .

Location in China

The mausoleum is located in central China , about 36 kilometers northeast of Xi'an , the capital of the former Qin Kingdom , on Linma Road . It is both near the capital of China during the Qin period, Xianyang , and at the foot of Lishan Mountain . The Sha , a 84-kilometer-long right tributary of the Wei River (Wèi Hé), flows about 1.3 kilometers east of the facility . The urban settlement nearby is the district of Xi'an Lintong , the center of which - in a slightly south-westerly direction - is just under five and a half kilometers away. The settlement area extends into the former mausoleum area today.

From the former imperial capital Xi'an , 13 imperial dynasties - from 221 BC. BC to 907 AD - the Chinese Empire ruled. There are therefore numerous imperial tombs from this era in the river plain of the Wei River valley and along the mountain slopes. Mount Li was rich in gold and jade , which were mined in ancient China .

construction

Construction of the complex began immediately after Ying Zheng was crowned king. Scientists and archaeologists speculate that more than 700,000 workers from all over China were involved in the construction. When he became Emperor of China after many long campaigns (221 BC), he used the retired soldiers to build his tomb, but also for other projects. There were also slaves and prisoners of war, which the Han -Groß historian Sima Qian called punished by castration or sentenced to forced labor. In the same year Shǐhuángdì also started the construction of a new throne hall south of the Wei River . This magnificent building was later given the nickname Epang Palace , the dimensions of which were given in historical reports as 675 meters long and 112 meters wide. The number of workers mentioned - more than twice as many as for the construction of the Great Wall of China - was reportedly employed for both construction projects . As a result, in some areas of China only women and children lived, many villages and farms were deserted and agricultural production stagnated. The common people were starving. Of the approximately 30 million subjects, two million died from forced labor or execution alone.

West of the village of Zhaobeihu, southwest of the outer mausoleum wall and about 1.6 km from the burial mound, two burial grounds were discovered. Workers from the tomb were buried here. One had been destroyed a long time ago, the other was better preserved. A total of 93 small graves were identified through prospection bores, almost half of which were subsequently exposed. All were elongated shaft graves from 1.10 to 1.76 m long and 0.50 to 0.76 m wide. They were 0.20 to 0.76 m below today's ground level. Usually two to three skeletons were found. The deceased, often young men, were buried in a squatting position. Eighteen broken bricks with incised characters were found on the skeletons. It is then reported that the convicts were sentenced to work, some of whom came from lower civil servant or aristocratic classes. Those found came from six kingdoms in Shandong . These findings confirm that convicts were used to build the tomb. Archaeologists also found around 100 graves of forced laborers, recognizable by iron ankle shackles. According to the account of the great historian , the emperor was a cruel tyrant who locked craftsmen and workers in his burial chamber after they had finished their work.

All the shafts for the terracotta warriors were built in a stable manner. The outer walls and the walkways between the parallel corridors are made of tamped earth. The inner side walls were made of upright wooden beams, which also supported the ceiling beams. When the pits were built, the ceilings were given three-meter-thick layers of mortar and earth. The ground of rammed earth is still partly hard as cement and was covered with bricks. Calculations showed that nearly 130,000 cubic meters of earth were moved to create the pits. In addition, there were around 8,000 cubic meters of lumber for the wooden structures in these.

Pit 4 of the “Terracotta Army” was built, but it did not contain any figures and remained unequipped, as was the entire grave complex in parts. When the emperor 210 BC Died, work on the site was abruptly stopped. In the following year, the builders piled earth over the alleged burial place of the emperor to form a tumulus .

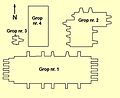

In ancient China, for example, an army was made up of three parts and an additional command post. Pit no. 1 and 2 represent two units of troops, pit no. 3 is known as the command post or command post. A third part is missing; this could possibly have found space in pit 4 if the system had been completed.

The account of strange things (Bowu zhi) by the Jin poet Zhang Hua (232–300 AD) describes in poetic form how the rulers of the Qin period ordered stone from Ganquan (today's Chunhua county town , Shaanxi province).

Archeology professor and longtime head of excavations, Duan Qingbo, doubts that the first emperor drove the construction for 37 years, as Qian wrote. Because all the clay figures and objects that they found are in the same style and they all had seals with which the craftsmen were liable for the quality of their products. The style of the pots and utensils has not changed. This would be very unusual for the length of time indicated. He therefore estimates that the tomb was essentially built over a period of ten years.

construction

Ancient Chinese believed that they had souls. According to their imagination, after death the soul left the human body in another world and continued to exist there. The grave offered a dwelling place for the soul. Qin Shihuangdi probably strived to have everything he owned during his lifetime with him after his death. That is why he probably had a city of the dead filled with many grave goods built as his underground realm.

The entire mausoleum complex covers an area of around 56 square kilometers. A wide processional street is laid out in it. The walled part of the grave complex consists of a rectangular, outer surrounding wall, similar to the palaces in the cities of that time. This measures over two kilometers on both long sides and almost one kilometer in width. Watchtowers stood on the four corners and watchtowers opened on the four sides. This is followed by the inner wall, which measures 1.2 kilometers in total length and over half a kilometer in width. Both are made of tamped earth, are eight meters thick and were originally eight to ten meters high. In the large space between the walls, a horse stable, a pit with limestone armor and helmets, the houses of the mausoleum officials, the houses of the guards, a pit with rare bronze animals and birds and a pit with figures - interpreted as dancers and artists . The clay figure of a woman in a coat is shown in a dance step. Figures interpreted as weightlifters, zookeepers, scholars, scribes, fools and musicians were also found. The "Pit of the Bronze Water Birds", in which a park-like brook landscape was imitated, was equipped with sculptures by musicians in addition to rare depictions of birds.

Located to the north of the tumulus , there used to be a large, rectangular hall enclosed by a covered corridor, 57 meters wide and 62 meters deep. Written sources describe this as an audience hall , which contained the emperor's robes, his crown, his armrest and his walking stick. Archaeologists found a magnificently designed carillon. He was the first ruler to have such an audience hall built in his necropolis, making it clear how important the ancestral cult was to him, which he expected for himself.

The inner rectangle is dominated by the burial mound. The emperor is said to have been buried in this artificially raised mountain, constructed in the shape of a pyramid. The hill has lost much of its original height over the centuries. The hill is surrounded by pits with accompanying burials, side halls, a living hall, a pit with figures of civil servants, and a 3025 square meter pit with magnificently designed bronze carriages.

There are two more pits about 310 meters east of the outer enclosure. One contains accompanying burials, the other clay horse replicas. Another 300 meters east of this - east of the Sha - four pits were also dug. In the first, which has an area of over 14,000 square meters, there are around 6,000 impressively large terracotta soldiers and 40 four-horse war chariots with horses made of bronze or clay. The pits of the terracotta fighters are laid out underground. In the pits, the figures were placed in corridors, which were separated from each other by areas made of rammed earth. The second pit contains 1200 terracotta figures and 89 Streit wagons on an area of around 6000 square meters. A third pit was empty, in the fourth smaller one there were 78 figures and a chariot, the so-called command center. The wooden chariots that have been proven so far have all crumbled, but left clear marks in the ground. According to excavation findings, the covered wooden structures of the pits were already finished when the sensitive terracotta figures were placed in them: At the front of one of the pits, the typical ramps were identified, via which the figures were carried down into the long corridors, which were probably lit by torches. That means that nobody, not even the emperor, has ever seen the arrangement of the clay fighters in their monumental effect - as it is possible today.

The ruler did not allow himself to be buried with his entire court. A development had already begun in the Chinese region that fundamentally changed the burial culture: people or horses, for example, were gradually being replaced by depictions of humans and animals. Early examples of wood and clay are from the 6th century BC. Occupied. Constructive changes followed later. Tombs from early Chinese prehistory were simple pits. Already in the 5th century BC Then some Chinese tombs resemble the living quarters more and more.

Chinese archaeologists have found that there are over 500 burial pits scattered around the tomb. The contents of the pits and records in traditional scriptures show that the finds in the complex also in a certain way reflect life at the time of the Qin. The very complex structure of the mausoleum had a major influence on the imperial mausoleum system in ancient China.

Discovery of the "Terracotta Army"

The exact location of the imperial tomb had been known for a long time. And later also in the western world, for example the French archaeologist Victor Segalen traveled to China from 1909 to 1914 and also visited the burial mound. However, the discovery of the "Terracotta Army" happened purely by chance in 1974 when farmers from Xiyang Village tried to dig a well. On March 29, they encountered a hard, scorched layer of earth. Pieces of clay came to light at a depth of four meters, followed by a brick-lined floor, a bronze crossbow mechanism and bronze arrowheads. Neither the great Han historian Sima Qian nor any other historical source mentioned the terracotta figures. The news of the find spread to Lintong County Town . The officer responsible for protecting ancient cultural objects traveled to the site with experts, and after various examinations of the partially broken figures, it was found that they were valuable finds from the Qin period. The figurines were taken to the Lintong County Culture House and restored there. Information about the find was attempted to be kept secret. However, a journalist from the Xinhua News Agency learned of the find and wrote a report about it, so that it became known to the people of China . A few months later, a group of archaeologists went to the area of the tomb and began a closer investigation. In the course of this, the underground "Terracotta Army" was discovered in the grave complex. The discovery was officially announced on July 11, 1975. The farmers were forbidden to dig any further in the area.

To date, around a quarter of the entire system has been completely exposed. The burial mound itself is archaeologically untouched. Chinese archaeologists want to open it later.

The "Terracotta Army"

The estimated number of almost 8,000 figures as well as the orders of the soldiers indicate that the term "Terracotta Army", which has already become established, is misleading. One can only speak of different parts of an army. Historical works of the same age - not to be taken literally - tell of armies that were several tens to over a hundred thousand strong. So there are far too few grave warriors to be able to describe them as a nearly full-fledged army. There is therefore much to be said for interpreting the groups of figures as a garrison of a unit. The position of the warriors, which is remote from the burial area, also supports this interpretation. The Chinese name for the figure constellations, known as the Terracotta or Tönerne Army , is Bingmayong (Chinese: 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng) and literally means “soldiers-horses-dead figures”.

The manufacture of the terracotta warriors probably only began after Qin Shihuangdi had ascended the imperial throne. Compared to men during the Qin dynasty, the clay armed forces consist of larger than average soldiers (foot, riding and charioteer soldiers, officers and generals), their horses and chariots. The simple soldier figures are at least 1.85 m tall and those of the generals up to 2 m tall.

It is a realistic representation of something like a complete garrison of that time. The overall arrangement in military formation and the various branches of service can be classified historically. The different ranks can be recognized by different pieces of clothing and armor . The painting of the materials shown was very realistic. On the shoulders of figures, for example, it seems as if the patterns of the painted clothes are somewhat warped - almost like in reality. In the case of surfaces that were supposed to represent fabrics with colored patterns, these were finely scratched in some cases and then redrawn in color. Differences in outer garments, belts with buckles and the wearing of boots also represented non-Chinese minorities in the clothing of the figures. For example, officers of the national minorities were depicted in their national costumes - under the long scale armor with straight ends. Warrior figures with curled up mustaches generally have high cheekbones and show physical similarities to the ethnic minorities living in northwest China.

Well-preserved paintwork on general figures shows patterns on the upper torso. Loops, a colored jacket, cuffs and the armored lacing could be recorded. A surprising delicacy in the design became visible. A bird pattern fabric with a black background is shown on an upper body. The borders have a pattern with diamond lattices and colored filling patterns. On the upper parts of the figure, special lacing of the armor plates could also be documented. The imitated lacing straps show extremely fine patterns in purple, red and light green, which perhaps represent decorative cords. Crossing decorative ribbons are painted in cream white and pink with a width of about 0.4 mm. Fine red and blue lines or patterns can be seen on the thin cream-white ribbons.

In the main pit, the terracotta soldiers were lined up in battle order. The first three rows (204 archers) form the vanguard . Behind it follows the main troop section, which probably consists of 6,000 grave warriors. Since the entire pit has not yet been excavated, the experts can often only estimate the total number based on the "density of figures" of the areas that have already been excavated. These main forces were secured on the left and right by the flank cover . The wooden chariots, at regular intervals in the center, served as command stations for the foot soldiers, so to speak. The discovery of two bells in the pits and historical reports show that the officers transmitted their commands via acoustic signals, probably also via drums. In the end, the rear followed . The main troops were protected on all sides by crossbowmen pointing outwards.

In the second pit there were figures of infantrymen , riders with horses, archers and chariots . Due to the large number of chariots and cavalrymen found there, the display of figures from pit no. 2 is interpreted as a rapid attack force. The archers were upstream, in the direction of the assumed enemy contact.

In the third pit, the excavators found figures which experts identified as military command staff based on their set-up and equipment (e.g. ceremonial weapons) ; it is therefore commonly referred to as the command center. At 17.6 × 21.4 m, it is the smallest pit and has a U-shaped floor plan. From the east side, down the dug main access ramps, one encounters the remains of a quadriga in the pit. Behind her were three armored soldiers with long staff weapons and the figure of a command officer. The team seems to have been ready to leave the underground parking space immediately to the east. Further armored dagger ax and lance bearers were found in the southern and northern limbs of the pit. Unlike most of the warriors - including those of the two other pits - these were not aligned to the east, but stood opposite each other with their backs to the shaft wall. They looked at each other as it were. The excavators came across offerings consisting of deer antlers and animal bones, which were probably used to conjure up victory.

There were four-horse wooden wagons in all three warrior pits in varying numbers. The illustrated crew of these single-axle teams was usually composed of one of these three types of soldiers: charioteer, command officer and heavily armed protection soldier. But these were mostly placed behind and not on top of the chariot. Three larger-than-life warrior figures side by side were probably too heavy and too wide for the roughly 1.4 m narrow car body.

It can be seen from the finds that a mass army consisting of peasants, mainly recruited for infantry, had replaced an army of elite fighters. This took place from 600 BC. In all feudal states of China, but most radically in Qin. Here civil and military organizations were heavily dependent on one another. A military unit consisted of five soldiers who could be collectively punished for failure of individuals on the battlefield. The rise of the individual in the system of military and social ranks, the amount of land that beckoned him as a state reward and the amount of a possible civil servant's salary increased with the number of enemies he was able to kill. Individual soldiers' figures and groups of these were organized in their intended function within the underground armed forces like set pieces.

All figures have been individually designed so that no two are identical in posture, facial features or equipment details. Noses, ears, hair, beards and the waist size also differ considerably. In the Qin period, great care was taken with hairstyles and beards. Adult men of the time usually grew beards, and all but a few Terracotta Warriors have beards. Shearing head hair or parts of a beard was, according to chronicles, a form of national punishment and, conversely, was severely punished - for example in a private argument. In all figures, with caps on their heads, hairpins are depicted in the hairstyle, as is generally the case with warriors, clasps, headscarves, colored hairbands, and artistic bunches and braids. The hairstyle was tailored to the wearing of a helmet or other headgear and the functions of the soldiers. Ordinary soldiers did not even wear caps on their heads, but heavily armored infantrymen in battle had heavy helmets. However, neither helmets nor shields were found in the pits of the terracotta figures. Written sources and archaeological finds prove this for the Qin troops. At least a partially broken and painted protective shield was found on one of the horse-drawn carts. The artifact depicts one of the shields of the Qin Dynasty soldiers. These were generally two feet long and forty wide, with red, green, and white geometric designs.

The first question that remained unanswered was whether actual soldiers had been reproduced or whether the creators freely designed the different figures. Eight different face shapes can be fundamentally distinguished in the terracotta warriors and can also be found in living people, but they are strongly associated with local features. In their implementation, they reflect a realistic representation of the Qin warriors of that time. The soldiers of the Qin Army were mostly recruited from the Qin population in the Guan-Zhong area, but also from other areas. The basic shape of the heads was made by modeling , then face details were designed. This made production comparable to manufacture in factories possible, but at the same time also the representation of different types and characters . The different face types suggest that a variety of such negative forms were used. Fingerprints found on the inside of the heads confirmed the production with models, whereby the shapes were each composed of two hemispherical halves. The seams ran vertically over the skull, sometimes in front of and sometimes behind the ears. With heads from one and the same two-part model, appearance and facial expressions still differ due to the different design of the facial features as well as the hair and beard costume. The ears are also pre-formed from models and attached. The beards are very elaborately modeled, and occasionally cut directly into the raw form. The various types of beard define the age and character of the grave warriors depicted. The hands were also preformed in models using four manufacturing methods and then inserted into the sleeve ends. Among the thousands of hands there are only two types, those with straight fingers and those with crooked fingers. Their dimensions are standardized, the same hand could be used in different functions. This production of set pieces , i.e. standardized components, also applies to the other parts from which the figures were put together. Only a system of set pieces made the large number of different figures possible. This enabled productivity to be increased to such an extent that the task could be fulfilled with the available material and in good time.

The production groups all worked according to the same scheme and put the figures together from identical basic shapes. There were variations, and parts of the figures were sometimes formed from rolled clay plates or from clay beads, but the structure of the figures always remained the same.

In the 714 terracotta warriors that were first excavated, eight types of physique could already be distinguished. The effect of the characters is generally outstanding, strong, heroic and elitist. The modeling of the bodies is simple but clever. Contours and lines are kept strict here, ornamentation has mostly been avoided. Although the body proportions are usually correct, some warriors have arms that are too short or of different lengths. Sometimes feet are too small or hands too big. This shows that the manufacturers did not all have the same artistic level. The main feature of the realistic style of the Terracotta Force is the faithful imitation of real people and objects. The figures are not portraits of individuals. The definition of a portrait includes the intention to achieve a detailed similarity with a certain individual . The manufacturing process alone - which divided all workpieces into individual work processes - shows that production was not based on a concept of the individual.

When executing the figures, the designers strove to be realistic. The figures were added to the grave instead of living people so that they would serve the soul of the deceased in the afterlife. Figures made of wood or clay from other tombs are much smaller and coarser and do not achieve the same degree of reality as the tomb figures of Qin Shihuangdi.

Artistic methods of exaggeration and abstraction were also used in the modeling. Certain features were overemphasized. For example, the thickness of the eyebrows was sometimes exaggerated, and cheekbones were modeled square and angular. This form of exaggeration emphasized the characters of the terracotta warriors.

Both court and craftsmen from the people made the figures. Many names have been passed down through stamped and engraved inscriptions on the warrior and horse figures. But there were also serial numbers . Because of the different origins, the artistic style is also different. Figures designed by the court craftsmen are figures of strong men. They appear like guardians of the imperial palace in their time. Figures of simple craftsmen are more varied. The technique of the court craftsmen is more skilful, more uniform and strict in style. That of the others is inconsistent and the style different, but livelier and fresher. Various reasons for these differences are conceivable, but essentially the differences are presumably determined by the different life experiences of the craftsmen. The artisans from the people associated with the people of the lower classes, from whom the Qin army was generally recruited. So they took familiar people from their own environment as a template. The court craftsmen worked in teams, which means that their technology is more uniform. The common craftsmen were of different origins and had learned from different masters, style and technique are different with them. It is understandable that the court craftsmen were no simple potters . You must have had certain experiences in order to burn figures in these dimensions and quantities. These were available in the field of building ceramics - at the manufacturers of sewer pipes in the palace workshops. Extensive canal systems made of clay have been found, for example, under the office of costume master in the necropolis and under the imperial palace. In size and proportion, these tubes resemble the legs of the terracotta warriors. The manufacturing technology must also have been very similar. Inscriptions confirm this theory: the foremen of the palace workshops used to stamp their names on the floor and roof tiles. Some of these names were also found on the terracotta figures. After 85 masters had been identified in this way, projections could be made: the Chinese archaeologists assume that each of the masters led a group of ten to twelve workers. These could have directed a workforce of around a thousand people. During the time when he was emperor, they would have had eleven years for the more than 7,000 figures, so they had to produce an average of almost 700 figures a year. It was therefore quite possible.

Simple craftsmen and sometimes convicts made the terracotta figures. It turns out that among the numerous warrior figures - radiating authority in their posture and facial expression - there are some with completely different expressions. The differences are not only in the tired facial expression and thin body of these grave warriors, but also in their sad appearance. Some craftsmen apparently dared to show their displeasure.

The grave warriors are made of burnt loess , which was extracted in the vicinity, and the pits of the mausoleum complex were also dug in loess soil. Analyzes show that the raw material used for the figures is very uniform and is identical in its composition to the soil on the northern slope of Li Mountain - near the grave complex. The figures, which are hollow on the inside, were all fired in ovens at between 900 and 1050 ° C. At these temperatures the unglazed clay remains porous. Therefore, when it comes to the material, experts speak of terracotta - baked earth. About 200 meters southeast of shaft 1, fragments of figures suggest one of the kiln sites. Experts estimate that two horses or six soldiers' figures could be burned in it at the same time. The figures were made using a process that is still used in China today, reduction firing. This creates the gray iron oxide characteristic of the unpainted terracotta figures . Standing terracotta warriors weigh between 150 and 200 kg. They consist of seven main parts, the plinth as a base, the feet, the legs below the garment, the torso , the arms, the hands and the head. Firing clay figurines of such dimensions had many pitfalls, especially since the wall thickness fluctuated greatly. The figures shrank by about 10 percent during the fire, this had to be done evenly everywhere, otherwise cracks would appear.

The art of the Qin terracotta figures marks the increasing maturity of early Chinese art in plastic design in ancient Chinese.

The depicted clothing of the warrior figures

Since the Qin soldiers wore private clothing, there was no uniform uniform. The clothes shown on the figures therefore give good information about the general clothing habits of the Qin society. The soldiers' figures were shown wearing a mixture of clothing styles used by the Chinese of the time as well as the equestrian peoples and tribal associations of the Eurasian steppe . The state of Qin was close to the border with non-Chinese peoples such as the Rong in the north or Di in the west. In the Qin period, the soldiers came from lower social classes, mostly farmers. They generally had to provide their own clothing for military service. Presumably there were special uniform regulations only for cavalrymen . The clothing of the foot soldiers and adjutants on the chariots probably corresponded to the usual peasant clothing. Written sources such as the Qin-era bamboo strip books from the Shuihudi grave find show that the consumption of fabric for the manufacture of typical clothing and armor was immense during the Qin era. Approximate calculations made on the terracotta figures largely confirm this. The majority of the Qin people and their common soldiers used silk for clothing, people from the lowest social classes mostly used cheap hemp .

The warrior figures usually wear belts at the waist, which are designed in a realistic and detailed manner in length, different widths, knot type of belt, shape of belt hook and type of anchoring of the belt ends on the belt hook. They are shown with or without decoration and leather-like. There are hook holes at the ends of the straps. In the chapter Shuolin xun of the philosophical work Huainanzi (Master from Huainan ) of the Han period it says: “If you look at the belt hooks of all the people in the room, they are all different. But they all wear the same belt. ”The terracotta figures reflect the fact that during the Qin period people also attached great importance to the decoration of the belt fasteners. The belts, which should probably hold the clothing together, are usually located under the stomach, so that it appears a bit pushed up and pushed forward. This custom was maintained until the beginning of the Tang Dynasty . Round bellies and a pronounced waist are depicted as the ideal of beauty for men in the Qin period.

The soldiers were generally depicted in shoes made of hemp, the cavalrymen in boots - leathery with laces. The shoes of the officer and soldier figures differed only in the shape of the shoe tips. The boot shape with shafts down to the lower leg came from the equestrian peoples. The cost of making boots was much higher than that of shoes, but they were stronger, more durable, and more comfortable. The cavalrymen therefore only wore boots. Some of these were then later taken over by other soldiers, as the finds also showed.

Color fragments of the robes and trousers show that they were monochrome. Headgear, belts, and armor were also decorated with various ornaments. Little was previously known about the ornamentation of the Qin period. The wooden chariots from the pits were also painted with fine, ornate ornaments, but only a small number of them have survived. The clothing reflects military and social rank differences.

Unarmored warrior figures

Basically, two types of armed forces can be distinguished in the three pits equipped with soldiers' figures: cavalry and infantry. The latter include the figures with an angled arm whose hand seems to be grasping a weapon that is no longer in existence. Even without their weapons, a viewer can easily identify these figures as generally carrying weapons. Some seem to have held a sword in their second hand. Still others - in almost identical appearance and posture - acted as crossbowmen. This could be seen from the remains of the crossbows and the bronze crossbow bolts that were found in the immediate vicinity of the shooters. The archers also belong to this class of troops and are the only group of figures that have not been found modeled in a frontal view. They were shown in the step position with the torso slightly leaning forward and turning to the side. To ensure a firm, steady stance, the rear leg was turned 90 degrees outwards. One arm stretched from shoulder to hand pointed down, while the other was bent at chest level. The fingers of his hand were bent slightly inward, as if they were grasping an arrow. Sometimes the position of the left hand seems a bit unrealistic, as it was lowered too low and the arm was sometimes too long as a result. Even without their bows and arrows, which are missing today, they can be recognized as archers. They look as if they have just drawn their bows with an arrow each and are able to shoot immediately at a target that presents themselves. Their thickly lined jackets, which end above the knees and which can be seen on the right side of the body with indicated belts and hooks, seem to want to give them sufficient freedom of movement. In addition, their thick lining makes them suitable to offer a certain protection from arrows flying downwards. The light and simple clothing of the archers enabled speed and mobility.

Lightly armed, unarmored infantry figures wore a round bun on the right half of the top of the head. It was probably related to the Qin time custom to reserve the right side for the place of honor that the knots on the right of the head were often worn. In the biography of the rebel leader Chen She in Shiji (grand historian records) these customs are referred to in general. Only some of the armored infantry figures and the depictions of the infantrymen with headscarves also had a round knot on the right half of the head. Round buns on the top of the head were often found in hairstyles in China. Figures from the spring and autumn period to the early days of the Warring States also wear round knots, but they always sat in the middle of the top of the head. The terracotta figures of Shihuangdi, however, had the round knots on the right side. This indicates that the hair knots on the right of the head were probably only used in the military, as they are nowhere, except here, archaeologically proven. Figures, reliefs and wall paintings from the later Han to Tang dynasties show buns in the middle of the head.

Armored warrior figures

Soldiers depicted with pieces of armor had to perform comparable tasks; many of the figures previously held long cutting and stabbing weapons for long-range combat in their hands. Dagger axes and lances once measured safely 3 meters and more. Some of the tank warriors were additionally equipped with a sword - for possible close combat. Unlike their unarmored counterparts, the armored archers were not ready to shoot, but seemed to kneel in wait. Remains of wooden bows and bronze arrowheads were also found lying on them. On the torso of these figures, the collars of knee-length robes could be seen under the armor. The legs of the armored and unarmored figures were wrapped in trousers - sometimes depicted with a leather-like shin guard, for example in the case of the standing archers. In other cases, modeled gaiters wrap around the lower legs of the characters. The depicted warrior feet dressed either modeled rectangular low shoes or boots with high shafts. The vividly designed scale armor has protruding shoulder protection and extends from the chest to over the hips. In this way, their bodies were partially protected. Much of the armor shown was kept a little shorter at the back, for example to allow more freedom of movement when walking. Cavalry figures also wore simulated armor and flat caps tied under the chin - which were supposed to fit tightly when riding. The armored charioteers were easy to identify as such by their position and posture. They stood upright between the other two types of figures, as if they wanted to grab the reins of the horse with their hands with their forearms stretched forward. Protruding flaps on the sleeve ends of the armor of some drivers provided hand protection from arrows flying downwards. Other trailer drivers had to make do with sleeveless breastplates. Armored soldiers to protect the war teams are regularly to be found on the right of the charioteers. Her pose shows that she is carrying a long polearm and a sword. The command officers, often referred to as "generals", are positioned to the left of the charioteers. At first glance, a figure from pit 1 appears to be unarmed. The position of her flat left hand at the level of the belly button suggests that she once rested on the pommel of a sword. A handle of such a weapon found on a figure confirmed this impression. The right hand lay loosely on top of the left. The officers pointed to their subordinates in front of them with outstretched forefingers. They were at the top of the strict hierarchy of the armed forces and made sure that they functioned. The different ranks of the grave warriors were primarily characterized by the headgear. The command officer's lavishly folded cap - often called the "pheasant cap" - stood out noticeably from those of the simpler figures of the charioteers. The higher rank of the officer could not only be read from his clear command. The hierarchical differences became even clearer when comparing the teams assigned to the wagons with the unarmored archers. The heads of these shooters wore no caps, instead the hair here on the back of the head is braided in several strands and artfully brought together in a bun on the side of the skull. Several types of hairstyles can be identified in the hairstyle of the terracotta warriors. Even if this looks like an expression of individuality today, it was rather another means of showing the subtleties of the ranking. A comparison of an armored commando officer and a simple, unarmored foot soldier or figures with different types of armor also shows that the type of armor protection also strongly depended on the military status of the wearer. The generals can be divided into three types: Type I , shown with hands crossed in front of the stomach, supported on a sword, with upper arm protection. Generals II with outstretched hands with similarly decorated armor, but without upper arm guards. Type III generals are only identified as generals by their caps and do not wear armor. Officers with straight armor, which is open not only on the left shoulder but also on the left side and closed there by pulling the edges and can be slipped in from the side, represent a specialty Shown connected to one another, but the cut similar to that of the officers' figures with a smooth upper part and surrounding borders, the lower end hanging down to the thighs and straight. Because of this "exotic" type of tank, these officer figures have been interpreted as representing ethnic Chinese minorities.

The terracotta generals wore a cap with pheasant feathers painted on it. The painters highlighted the spring structures from the background with the help of their brushstrokes. In this way feathers were generally reproduced. The armor has elaborately tied armor plates, clothing trimmings with patterns and layers of fabric on the chest and back made of silk. The armor of the wagon officers only extends below the stomach area and is locked on the back with crossed straps. They also wear caps with a square, angled stripe on their heads.

The tanks of some warrior figures were painted with elaborate patterns. The ornaments can be roughly divided into geometric shapes, such as diamonds and stars, but also flower and zoomorphic motifs such as birds, dragons and phoenixes . The tanks show four ranks, from the lowest for simple soldiers to that for high-ranking officers. Armored foot soldiers - all formerly with a spear in their right hand and possibly a sword in their left - are the most common. There is generally only a relatively small repertoire of types for all individual parts of the figures. Excavation reports distinguish between two types of armor, each with three sub-types, in terms of shape and design.

Coloring of the terracotta figures

First of all, a not yet identified barrier layer was applied to the terracotta. Without this measure, the later paint primer would have penetrated more deeply. Although this would have resulted in better adhesion of the paint layer, the paint consumption would also have increased significantly.

The color scheme of the terracotta figures was built up with pigmented layers over a one or two-layer dark brown primer made of East Asian lacquer , which was obtained from the sap of the lacquer tree as a viscous, gray-yellow product. This Qi varnish has always been valuable because its extraction is complex and the trees can only be exploited to a limited extent. Analyzes also showed that mostly valuable materials were used for painting. Since Qi varnish is waterproof, heat-resistant and also resistant to acids, it is generally good for protecting and decorating surfaces. Weapons and leather armor were painted with it very early in ancient China.

Many years of work and countless hands were used to color the figures. The paint was applied to all figures with a brush. The characteristic way the artist paints, also the peculiarity, the characteristic of the artistic design, in particular the lines, can still be seen in many fragments. In general, the choice of color shows a preference for intense, unbroken colors. The colors of the soldier's clothing shown indicate that there were no fixed rules for the use of certain colors and that hierarchical differences were therefore not decisive in the choice of color. The clothes were vermilion, purple, rust red, dark green, light green, violet, dark purple, white, light blue and brown. The colors of the figures are strong and the colors clear. Colorful color combinations were clearly preferred. Red and green or purple and light blue predominate in warrior clothing. Lacing straps for shoes and boots as well as chin straps for headgear were also colored. In addition, great emphasis was placed on decorations. The different colors stood for certain emotions: red provoked enthusiasm , joy, courage, love and fighting spirit; Green symbolized peace, permanence, aliveness and happiness; Violet was associated with grace and elegance; Blue touched deep and steadfast sensations. The colors of the terracotta figures expressed warmth, joy and liveliness and tried to convey prudence and courage. They underlined and emphasized the shape of the figures, which expressed bravery, courage and steadfastness. The entire modeling of the figures, which make them look like pagodas today , conveyed a calming and unshakable force. In general, the colors of the figures' clothing appear warm and lively, in no way depressed or sad. The color scheme of the figures is understood by research to imitate the real clothing of the army of Qin Shihuangdi. Examination of the painting of the faces and hands reveals that the individual figures show a differentiated image of the skin incarnate. Possibly for a clearer characterization of the imperial army, which was recruited from various ethnic groups of different kingdoms. Fragments found generally showed pink flesh tints and dark pink skin mountings to the figures. A figure head from pit 2 also has a green face painting.

Basically, there was no colored tinting of the individual surfaces, but rather a very elaborately designed, individual polychromy of each figure with precise flesh tones, lips and eyes, beard and detailed execution of fingernails or clothing details. Different eye colors and neck hairs were even shown. Every belt strap, every armored scale and every connecting element was precisely colored. Fine and detailed painted patterns adorned the borders and hems of the garments. The use of rare and high-quality colorants aroused an image of radiant wealth and great power. Even the sparse remnants of former splendor that have survived here today represent the largest stock of ancient colors on sculptures - elsewhere, on the other hand, there are only traces or written sources from ancient times . Lots of vermilion was used for the color scheme. Approximate extrapolations based on the figures suggest that the craftsmen processed at least 2,000 kg of vermilion in the Terracotta Force. If the experts now assume a kilo price of 2,000 euros for high-quality cinnabar in Germany, or a tenth of that in today's China, the mathematical result in both cases is enormous sums of money. Coating thousands of large figures with varnish and painting them down to the last detail was an amazing challenge in itself. But it was obviously not beyond the demands of an emperor who once even thought of having the city walls of his capital completely painted.

Naturally and artificially produced pigments were detected. Furthermore, not only the painting materials used, which characterize the color of the terracotta figures, but also the elaborate painting technique, which was selected for painting an estimated total figure surface of 16 square kilometers, are important. The targeted and coordinated use of pure pigments or mixtures for painting or differentiating individual parts of the figures, as well as the partly one-layer, partly multi-layer structure of the coloring, prove the high quality of the then very advanced painting technique. The many color gradations of the flesh tones and depicted clothing are in harmony with the silky smooth, brown surface of the East Asian lacquer. In addition, the thinly applied varnish shines. In contrast, the color versions are thicker and matt. The black, shiny hair against bright red but silky matt hairbands and the dark, shiny pupils against matt pink skin create further contrasts.

Natural pigments were lead carbonate , kaolinite , cinnabar , malachite , azurite , auripigment, and yellow and red ocher . Man-made were opposed leg white, white lead , red lead and a violet pigment, the so-called Han-violet .

The weapons of the grave warriors

Real weapons were found: swords made of bronze, arrowheads and spearheads made of bronze and iron , as well as crossbows with bronze trigger mechanisms. The terracotta warriors' weapons, dated with a stamp, date - among other things - from the first years of the reign, when Qin Shihuangdi was still king. So they had already been used by real soldiers before they were put into the hands of the earthen soldiers. These weapons from the state-owned factories are the earliest products in China, which according to the law had the manufacturer's name noted. The purpose was not burgeoning individualism or signatures as an expression of the producers' personal pride in their work, but an opportunity for quality control. There were also serial numbers. Each piece was of consistently high technical quality, although inscriptions on the weapons show that large numbers of them were manufactured in state factories.

The weapons found by the grave warriors are similar in type and shape to those of the six conquered empires, but they are made almost exclusively of bronze. At first only one spear, one iron arrow and two bronze arrowheads with an iron shaft were discovered on weapon parts made of wrought iron. The regions were already during the Warring States Period known to some extent for the production and use of iron weapons components. Already in the 4th century BC The processing of iron initially developed in defense techniques: The oldest preserved and restored iron armored helmet comes from Xiadu (grave M 44). Fighting with crossbows and iron and steel weapons did not begin until the last half of the clashes between the “Warring States”, and for their warriors armor and helmets were initially made of iron. The earliest known iron sword in China dates from the 8th century BC. BC (early Chunqiu period , 722 to 481 BC). Based on the analysis of the finds from the tomb, experts argue that the development of iron weapons stagnated in the Qin period. However, many iron tools were found in the tomb. In contrast, lamellar armor with movable leather scales, which the figures show in various designs, are considered to be a new development in weapons technology from the Qin period . The state of Qin was generally backward in terms of weapons technology , but was ultimately able to annex all adversaries. According to their inscriptions, the weapons from the pits were manufactured in the centrally organized imperial workshop Sigong . Fittings for the imperial chariots and horse bridles were also produced here. The dates in the inscriptions indicate from the third year of reign - still as king - an almost continuous production, with interruptions, until almost the last imperial years of Qin Shihuangdi. Before the seventh year of manufacture (240 BC), its Chancellor Lü Buwei was the chief official responsible for the control. After that, the name of the person supervising is missing and only the names of the craftsmen who produced in the central workshop are found. This shows a weakening of the Chancellor's power and thus a strengthening of the emperor's centralized power .

Kneeling shooters were shown tightening their crossbows, the leather lamellas of their armored tunics are reproduced in detail in clay. The structure of the exposed shoe sole has also been worked out. The Chinese crossbow used was developed as early as the Warring States Period (around 475 BC). Unlike the more well-known European crossbows, it does not have a shaft for a shoulder stop, but only a handle. The bow was made of wood or horn, the shaft of wood. The trigger mechanism was made of bronze and was already standardized in series production during the Qin period . It consisted of four individual parts and was manufactured so precisely that it could be taken into the field as a spare part by the Qin troops and easily replaced if necessary. The precision of the moving parts, cast exactly into one another, was only a fraction of a millimeter. It can be assumed that this accuracy in the manufacture of weapons contributed to Qin's success against the rival feudal states .

The tendon restraint was designed to be simple and functional. With the help of series production, the military command was able to quickly equip large numbers of soldiers. The penetration power of these crossbows was not as high as that of the later used by the Europeans, but the quantity made possible compensated for this disadvantage. Early forms can be found in China, for example to equip simple fortified farmers with it in the event of an impending invasion by equestrian peoples from the northwest.

The initial assumption that the builders of the tombs had already protected the weapons against decay by means of a chromium salt solution, turned out to be a mistake according to a study published in 2019; the chrome finds on the weapons are therefore contamination from immediately adjacent paint colors. The good state of preservation is probably due to the moderately alkaline pH value and the very small particle size of the earth as well as the composition of the bronze.

Photo gallery

Pit No. K 9801, with flagstone helmets and armor

In one of the earth shafts (identification code K9801 ) in the walled mausoleum area, individual pieces of stone slab armor that had fallen apart were discovered in 1998. Since then, vast quantities of tiles of stone armor and helmets have been excavated over an area of 145 square meters. The armor for the warrior's body was once made from hundreds of pieces of stone, which were connected with bronze wire to form protective shirts like fish scales. According to knowledge, armor consisted of around 600 individual parts. With a working day of eight hours - as one of the assumed calculation factors - there are estimates of the completion time for an armament of almost a year. According to other estimates, the grave shaft contains more than five million tiles. This indicates gigantic activity and a multitude of labor and arms production facilities required. After more than ten years of work, Chinese archaeologists have restored some of the stone armor.

The lengthy manufacturing process would have been too expensive for simple foot soldiers, so only higher officials and officer ranks came into question as porters or soldiers from a special protection force of the emperor. The limestone armor was not suitable for active offensive combat - it was too heavy for that - a protective function for passive warriors is conceivable. In addition, the leather armor used at that time seems to have served as a template for the stone people. The scale construction generally allowed a high degree of mobility. The armor left enough room to move around the joints of the body. Most of the armor is of the same type: the stone discs have different geometric shapes, with non-overlapping edges and are partly artistically decorated. But there are also some tanks made of very thin stone plates and with a fish scale design. Stone armor for war horses has also been archaeologically proven. The armor was originally attached to wooden stands and placed in the pits.

On the basis of field studies and further research, the mausoleum archaeologists conclude that the stone quarrying took place in the northern mountain regions in Fuping County ( Shaanxi Province ). In fact, the Shi Ji history book mentions that stone material was extracted from the mountains in the north. In terms of material, the armor plates are made from brown-gray to dark-gray slivered limestone (slab limestone). It is characterized by foliation , which allows easy splitting into relatively thin platelets (from 3–5 mm). The cleavage surfaces are dark and slightly brown. It is an extremely dense limestone.

In a Qin-era well near the tomb, utensils that were used to make the connecting wires of the limestone armor were found together with unfinished or broken armor plates. Among them was a clay model that can be used to explain the work technology and manufacturing mechanisms of the wires. The mold, which was about 10 cm long and 4 cm wide, was perforated along its length. The holes were close together and in cross-section showed the exact shape and size of the original plate wires. The wires were probably all cast in a short time and not - as was common in Europe at the time - driven. Clay mold casting is a technological advance to gravity die casting and melt mold casting ("lost wax method"). The first finds of cast wires date back to the late Neolithic period of China.

When examining a plate drill hole with the scanning electron microscope , fine drill abrasion could be detected along the wall. A material analysis showed iron abrasion. It could be assumed that the drill used must have been a forged iron drill. However, only a few drill bits from the Qin period have been found elsewhere. Bronze drills were initially also considered as drills - since in China during the Qin period the use of bronze was more common than the use of iron - but the service life was too short compared to hand-forged iron drills. There are no representations, descriptions or finds of complete drills from that time. It is also likely that racing spindles or a fiddle bit were used. The vast numbers of holes with which the limestone slabs were drilled suggest that the manufacturing process had to be streamlined. Previous tests showed that production using a simple hand drill - just a single hole - took up to 20 minutes. With the help of a simple bow of fiddle , 5 mm stone plates - corresponding to the thickness of the armor - could be removed in 2-3 minutes. be drilled. An extrapolation just for the drilling time of all armor plates would result in a very high amount of time.

Round and various polygonal holes were discovered in the stone platelets, which also points to the use of pointed and flat drill heads with different numbers of cutting edges in the "fiddle technique".

The extremely complicated surface designs of the objects found elsewhere from the Warring States' era already speak for the use of the first iron tools. The introduction of mechanical workbenches took place as early as the Eastern Zhou Era (770 BC to 256 BC). Rotating cutting instruments, drills and grinding heads were used. It is assumed that children were already up to the various tasks and were used for the lengthy work steps. Specialization within the individual production workshops is also typical. The objects - which required a lot of effort and skill - were never made by individuals, but went through various stone armor workshops in which the different work steps such as sawing, grinding, drilling and polishing were divided. Existing knowledge about traditional jade processing in ancient Chinese could be adopted by the researchers, as the principles of the various processing steps of this fibrous and tough gemstone could easily be applied to other rocks such as limestone. From the period of the Warring States , the influence at the time of important warriors can be seen in the jade. Now the stone was also used as jewelry for people and weapons. The following Qin dynasty did not develop significantly with regard to this jade art, nor did it develop an independent style.

The excavations indicated that the shaft may have been a weapon arsenal for Qin's underground force. The renowned archaeologist and former director of the mausoleum, Yuan Zhongyi , initially speculated in 2002 that the uncovered objects were probably only pure models that had been created especially for the grave.

Pit No. K 9901, "Artistengrube"

Lighter clad terracotta sculptures revealed this pit in the walled mausuleum area, depicted with colorful lumbar wraps in precious, multicolored patterned imitation silk. In contrast to other figures, the figure bodies of the "artists" were partially exposed. The eleven figures stood upright on their plinths. Some held up an arm or raised the heel of a foot, giving the impression of movement. Others, however, kept their arms crossed over their stomachs as if they were waiting for their intervention. Some are tall and strong, while others are shown small and narrow. All figures were found broken, six were initially restored. The manufacturing process for these figures was basically the same as that for the terracotta soldiers, so the restoration method was also identical. Four horseshoes and a stone bridle from a horse-drawn cart were found in the pit. In addition, weapons such as spear and arrowheads, and armor tanks. A decorated bronze kettle weighing 212 kg was also recovered. The builders divided the pit into three corridors, which were aligned in an east-west direction.

It is believed that acrobatics are portrayed here. However, based on the evidence, one can only speculate about the type of demonstration that was supposed to entertain the emperor for posterity. Maybe they played musical instruments, did gymnastics or practiced in physical competitions.

In 2006, the skirt patterns of the artist figures were examined, which differ from those of the terracotta soldiers in terms of painting technique in that they are monochrome and three-dimensional. The geometric shapes used are partly similar, for example the broken rhombuses, angled ornaments and eight-pointed “heavenly bodies” (mostly interpreted as “sun”), but sometimes also different, with curved shapes or rosette-like applications . Similarities can mainly be demonstrated to archaeologically proven textiles from Mawangdui near Changsha . There fabrics were found that have almost identical patterns of broken diamonds in staggered rows. It is silk gauze and a damask fabric . Fabric representations with rosette-like decorations could represent embroidery, damasks or velvety textiles. Especially the rosette-like decorations, which are reminiscent of scattered flowers, are unclear as to their origin, as there are no documented floral ornaments from this time in China. The origin of these forms remained unclear.

While in the warrior figures bones and muscles are hidden under the multilayered layers of the imitated wide garments and thick imitations of armor and they appear awkward and stiff, although at one time a lifelike representation was clearly sought, and a viewer sees the very realistically shaped hands or head and neck sections off, this viewer of the possibly dancer and acrobat figures, on the other hand, gets the impression of a predominantly realistic body representation. The figures are usually only dressed in a loincloth , which allows a view of the body anatomy . The Qin sculptors endeavored to harmonize the figure's body with - naturally existing - bones, joints and the associated muscles. The upper body of a figure, for example, in which perhaps a dancer was depicted, shows a well-developed chest and stomach area, while the legs are modeled in an anatomically correct manner - with knee joints and kneecaps that can be sensed underneath. A second alleged dancer figure, also with a raised arm and legs in a crotch position, shows ribs under the taut skin of the chest. The Qin artisans' precise understanding of the body becomes even clearer in a figure with a stocky and muscular build that may have modeled an acrobat or a weight lifter. His body parts showed numerous anatomical details such as biceps and internal tendons were suggested. It has never been portrayed in China before. If the lifelike painting is now taken into account, it can be imagined that for the Chinese, who were generally unfamiliar with realistic sculpture, the figures would have looked like real people.

The shoulder axes of the dancers, which remain horizontal in spite of a raised arm, and the stiff and unmodeled knees of the weightlifter prove that there was no such thing as a “Greek” understanding of the human body in art, which is probably unknown to the Chinese . The fact that there was no tradition of large-scale sculpture in China at that time that could have led to these lifelike depictions of people, i.e. that these were the first attempts at lifelike handling of the subject of the human body in plastic representation, is surprising. In ancient Greece, where realistic representations of the human body had been the focus of interest for generations of sculptors, the art of creating credible body sculptures required two hundred years of intensive development. The discovery of human anatomy was also an intellectual process that took place slowly and led through many individual steps from archaic to classical Greek sculpture.

In China until the end of the 3rd century BC, No special effort was made to depict anatomically correct human bodies. The innovation came abruptly. After the reign of the first emperor, the realization of lifelike or realistic sculptures was not pursued any further. In any case, these did not exist in the everyday Chinese population. For several generations, large-scale sculptures were still made for the graves of the Han dynasty in a certain local proximity to the Qin Shihuangdis tomb complex. In side pits of the imperial graves of the early West Han period (206 BC to 9 AD), 50–80 cm tall naked figures were found, which depicted summarily formed, barely formed human bodies and originally wore clothing made of fabric. Later, the craftsmen generally only modeled small, incomparable statuettes and for centuries no new attempt was made to show the anatomically correct structure of a person in a sculpture.

The first test excavations, within the part of the mausoleum that was once walled, took place in 1999. October 2011, K9901 was made available to the public.

Pit No. K 0007, "Pit of the bronze water birds"

The grave pit was created about 900 meters northeast of the east corner of the outer mausoleum wall. A second animal pit with bird burials was found about 500 meters away in 1996. Both pits were located near old fish ponds and in some way linked to their environment.

The pit has been excavated since 2001, in which a park-like stream landscape was imitated, around which bronze cranes , geese and swans were grouped. The tunnel-like facility measures almost 1000 square meters. The walls and ceiling were once covered with wooden boards, the tunnel floor was criss-crossed by a branched stream about 60 meters long and 1.4 meters wide. A total of 47 water bird sculptures were found in the pit by 2002. Technically fascinating and unique, the birds were depicted with lifelike plumage. The differently designed types of feathers, such as fluff , down and wing feathers , and their arrangement on the sculptures show that the artisans of the Qin period had studied living birds very carefully before they made these figures. The life-size sculptures were executed as hollow bronze casts and each completely provided with a multi-layered paint finish. The finds are the oldest surviving evidence of life-size, hollow bronze sculpture in China. A large crane held a small fish in its beak as if it had just caught it. None of the animals had the same head posture, each was held in natural motion: they stretched their necks in the air or bent them towards the water, they shoved, and their beaks opened they seemed to chatter. The birds originally stood on pedestals. The swans are about 0.90 meters long, the cranes and wild geese are about 1.3 and 0.5 meters long.

All birds were severely damaged, caused by the early partial destruction of the mausoleum pit, by fire and vandalism, by a later ceiling collapse and an ingress of groundwater. As part of the German-Chinese cooperation in the field of cultural property protection funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research , some sculptures were restored between 2003 and 2005. The objects were processed in the restoration workshops of the Shaanxi Province Archaeological Institute in Xi'an. The measures were carried out by restorers from the Roman-Germanic Central Museum together with Chinese colleagues from the institute there. The restoration turned out to be very complex due to the condition of the find of the figures. The heavily corroded bronze birds showed thick layers of corrosion combined with remnants of the paint. The several years of work were accompanied by intensive analyzes of the former manufacturing technique of the sculptures. With regard to the casting technique of that time, these did not show a homogeneous picture in detail, but clearly referred to a casting using the lost wax process . In addition, the binder used in the paint and the pigments on the residues were analyzed and tests were carried out on the paint application technique used at the time. The structure of the surface of the color version also originally corresponded to the plumage of the real water birds that served as a model. For example, down feathers in the chest area and the large plumage on the wings were reproduced. The lifelike impression was reinforced by the colorful design of the frame, which, however, has only survived in small areas. It can be clearly stated that all cranes were designed in white, all geese in black and the swans in both color variants; In addition, tiny traces of red paint could be discovered in the head area.

Terracotta musicians also came to light here; they were once in wood-paneled niches in the side walls of the pit. Their clothing was shown with knee-length robes and trousers. On the heads of the sculptures, simple imitation hats covered the modeled hair parts and knots on the back of the heads. Seven figures were shown kneeling, one of their arms was angled up to head height during the modeling, while the other was made hanging down and reaching slightly forward. Eight figures sat on the floor with their legs outstretched. The palms of their forward-facing arms were made to point once down and once up during manufacture. This physical expression in particular suggested that they should represent zither players . Remains of mostly decayed wooden musical instruments discovered nearby identified the figures quite clearly as musicians. One of the clues found is a small opening pick . The total of 15 terracotta figures were depicted in long robes with folds from left to right, tied with a leather-like belt. Attached to the belt on each right is a small rectangular pocket, shown hanging down. The figures have imitation shoe socks and are without shoes. All are mustache bearers. One of the figures is only 86 cm high and 38 cm shoulder width. More than 260 small objects were found in an area close to the figure. Including a piece of silver shaped like a fingernail, over two hundred bronze objects shaped like awls and nine differently shaped pieces of bone material.

Even the waves should be visible in the watercourse of the brook; the archaeologists found water waves formed from clay . The grave pit differs from the other pits in many areas, in particular the representation of the stream, the exhibition platforms for the bronze water birds, the double roofs made of mats with herringbone patterns, the wall panels with tongue and groove connections and the wall niches. A special place was created for all objects. The archaeologists recognize an artistic necessity in the design of the grave pit.

Pit No. K 0006, "Official Pit"

In 2000, a pit with terracotta figures interpreted as four civil servants and four charioteers was found at the southwest corner of the inner walls of the tomb complex. The painting on the faces was still in good condition, there were no military weapons. All "officials" were probably once standing there with folded hands, hidden in their clothing sleeves. These figures were each depicted with a knife in connection with a sharpening steel - hanging from a strap of the belt. These correction tools were used to scrape off the text on writing strips made of wood or bamboo, from the material that was written on during the Qin Dynasty. This way of carrying developed into a real fashion among the writers during the Qin period. The - presumably - official figures could have been modeled on an intermediate level of the courts of the Qin period, as some archaeologists assume. Some believe that the pit was intended to be an underground stable for the emperor and that the objects were intended to prepare for the emperor's future journey.

The pit is five meters deep, extends in an east-west direction and contains a front and a rear chamber. The walls are 2.7 meters high, made of compacted earth. The floor and ceiling were made of wood during construction. Traces of a wooden horse-drawn cart were found in the western part of the pit. First nine skeletons of adult horses were excavated in the rear chamber. Based on the location of the finds, it was estimated that a total of 20 horses are buried in the pit.

In October 2011, K 0006 was made available to the public.

The splendid bronze horses

In 1978 excavators discovered a large pit with horse and carts as grave goods 20 meters west of the emperor's burial mound . During the later test excavation on a small area, two bronze carriages came to light from this 7.8 meter deep pit. In addition, large amounts of hay that were once laid out for the draft horses. They are the earliest, largest, and most technically advanced team of horses known in China.

The bronze horses actually stood in a wooden shrine . Since the shrine had become unstable due to the time and the pit collapsed, the two teams were badly affected during the excavation. After a time-consuming restoration , the second team has been open to the public in its original form since October 1, 1983. The other team could only be seen eight years later because it was too badly damaged. Both teams have been produced in an extremely complex manner in about half their real size. They are decorated with numerous silver and gold elements. 1,720 decorations, made from over three kilograms of gold and four kilograms of silver, were attached to the second team.

Investigations showed that manufacturing required processes such as casting , carving , soldering , riveting , inlaying , filing and grinding . Rigid connections were made, among other things, by welding, edging - by means of sleeves and inserting. Movable connection technologies such as push-button connection and articulation were used on the car . A high level of artistry was achieved in each procedure . The bridle is, for example, composed of alternating silver and gold tubes by soldering, but there is hardly any soldered seam on the bridle. The reins , on which the articulated connection technique was used, are still movable today. Most of the components were manufactured using the casting process, which most clearly shows the state of the art at the time. The thinnest parts of the umbrella, which serves as the car cover, are only 2 millimeters thick, the thickest 4 millimeters. The composition of the alloy is almost in accordance with today's standard. By regulating the content of copper , tin and lead , bronze components with different degrees of hardness were achieved.

Just like the terracotta figures in the mausoleum, the two bronze spans are also shown true to life in every detail . The horses and charioteers look alive because their body proportions have been anatomically matched and all the details match the anatomy . Face, short beard, eyelashes, hand lines, hair and nails of the team leader are reproduced in a lifelike manner. The charioteers of the bronze cuboid were depicted with brightly decorated braids on the sleeves of their double jackets. The jackets were kept in green, the borders were executed with geometric patterns of fine black and red lines on a white background. The rank of officer can be read off the charioteer figures. In contrast to this way of working, the painting on the car body is not designed to be natural. Tiger , dragon and phoenix patterns are painted in very bright colors on the white base color on the outside and inside . The edge of the box is decorated with colorful, stylized ornaments . Each of the draft horses was adorned with a tassel made of fine bronze threads, each less than 1 mm in diameter. The question of whether these were cast, cold drawn or hot rolled has so far remained unanswered.

The two teams originally stood one behind the other in one of the pits and are also exhibited in the mausoleum museum in this way. They are drawbar teams with four horses and a steering officer. Each combination weighs over 1.2 tons and consists of more than 3,000 individual parts.

The front team is the so-called high car , as its occupants had to stand upright. Unlike a normal chariot , an artfully decorated umbrella serves as a roof for this chariot. War implements can be seen in the car body: a bronze quiver with 50 sharp arrows and one with 12, a crossbow and a bronze shield . Only one figure, the officer, can be seen on this team. He holds the reins in his hand, has a sword by his side and looks forward. Judging by his appearance, he represents a general . On the driver of the bronze car no. 1, a white disk with dots imitates a bi-disk made of jade with the typical grain pattern. The figure shows that the ritual discs were worn as belt pendants. Similarly structured white spaces on the peak this Bronze Warrior recall inlays , for example, the silver and gold Tauschierungen qinzeitlicher bronze objects. The modeled belt buckles (in reality made of bronze or silver) and the hair clips and toggles (in nature made of bone) on the terracotta warriors show that silver and leg objects were depicted with white paint. The plastic weighs over a ton. It is also called "The Inspection Car".

The rear team is the so-called pleasant car . Such a team was available as a passenger car for members of the imperial family and nobles. The horses have different sizes: from 65 to 75 centimeters. The charioteer is 51 centimeters tall when seated. With the horses, the whole team is 3.28 meters long and 1.04 meters high. This team has an ornate and painted car body, which is divided into two rooms. In the front room the charioteer sits on his heels, he wears a high hat, the reins are in his hand and a sword by his side . The closed back room has a roof cover in the shape of a turtle shell , inside the traveler could lie on the well-padded floor or sit comfortably on the bench. The car body is provided with a window at the front and on both sides. Through high-tech, diamond-shaped holes, inmates could see inside out, but not outside in. Since the car cabin is ventilated, it is also called "The Air-Conditioned Car".

The chariot and the passenger car belonged to the imperial motorcade as escorts. The chariot served as a guard car on the journey, the passenger car for women or ministers as an imperial escort. While the terracotta warriors are seen as a protective force for the underground empire of the emperor, the bronze carriages in the tomb complex are seen as the travel vehicles for the emperor's soul, seen from the overall concept.