Albrecht Count von Bernstorff

Albrecht Theodor Andreas Graf von Bernstorff (born March 6, 1890 in Berlin , † probably April 23 or 24, 1945 there ) was a German diplomat and resistance fighter against National Socialism . He was one of the most important members of the resistance from the environment of the Foreign Office and was an outstanding leader of the bourgeois- liberal opposition.

Bernstorff worked at the German Embassy in London from 1923 to 1933 , where he made lasting contributions to German-British relations. In 1933 he was put into temporary retirement by the Nazi rulers - he had rejected National Socialism from the start. In 1940 the National Socialists arrested Bernstorff and deported him to the Dachau concentration camp , from which he was released a few months later. Until he was arrested again in 1943, he helped persecuted Jews and was a member of the Solf Circle , a bourgeois-liberal resistance group. Bernstorff established the relationship between the Solf circle and the Kreisau circle through Adam von Trott zu Solz . In addition, through his international contacts, he was able to establish connections with influential circles for the resistance, which served in preparation for the assassination attempt of July 20, 1944 .

After he was arrested again, Bernstorff was imprisoned in the Gestapo headquarters and since February 1944 in the Ravensbrück concentration camp . In December 1944 he was transferred to the Lehrter Strasse cell prison in Berlin-Moabit , where he was interrogated by the Gestapo almost every day. At the end of April 1945 Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff was murdered by the SS.

origin

Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff came from the Mecklenburg nobility . The noble family von Bernstorff had produced important statesmen and diplomats over generations. They had achieved particular importance in Denmark , where Johann Hartwig Ernst von Bernstorff had decisively promoted the Enlightenment as Minister of State in the 18th century . In 1740 he acquired Stintenburg and Bernstorf am Schaalsee , on the border between the Duchy of Lauenburg and the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin . His nephew, Andreas Peter von Bernstorff , represented Denmark's interests as Foreign Minister at the end of the 18th century. Despite the rural aristocratic living conditions, the Bernstorff family never completely belonged to the arch-conservative Junkers in East Elbia , but always looked abroad: the diplomatic family tradition had produced a unique cosmopolitanism , combined with a generally rather liberal worldview.

Bernstorff's grandfather, Albrecht von Bernstorff (1809–1873), had been Prussian Foreign Minister and German Ambassador in London . His father, Andreas Graf von Bernstorff (1844–1907), was also in the Prussian state service and represented the interests of the Lauenburg constituency as a member of the Reichstag for the German Reich Party . He was also very religious and raised his children in the spirit of pietism . He took up his role as church patron intensely. In addition, he participated in the establishment of the German YMCA and the German Evangelical Alliance . In 1881 Andreas Graf von Bernstorff married Augusta von Hottinger , who came from the Hottinger patrician family in Zurich . The first child, Albrecht, was only born after nine years.

Childhood and Adolescence: 1890–1909

The identity-creating places of his youth were Berlin and the family seat of Stintenburg. He received his school education mainly through home tuition in the capital. Although the father's strict religiosity shaped everyday life, Albrecht did not adopt any of this trait. Instead of the moral rigor that he exemplified, he found liberality and tolerance towards those who think differently as early as his youth . The contrast with the father's way of life often intensified this development, which sometimes led to tensions between father and son. In contrast, the relationship with the mother was extremely intimate. It was only shortly before her death that this relationship became upset when Bernstorff tried to lead his life independently and independently of his mother. His emotions testify to a very close bond with his mother.

Bernstorff spent his youth mainly in the metropolis of Berlin, he only knew the Stintenburg family seat from holidays. As a schoolboy training was tutor by a short visit to the Empress Augusta High School completed in Berlin. There he passed his Abitur in 1908. He was particularly interested in learning foreign languages, especially English , which he has spoken fluently since his youth. When his father died in 1907, Count Albrecht von Bernstorff became head of the family and lord of the Stintenburg estate at the age of only 17, but under the tutelage of his uncle until his 25th birthday. After passing his Abitur, Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff began an agricultural apprenticeship on a castle estate in the province of Brandenburg .

Rhodes fellow at Oxford 1909–1911

In 1909 Bernstorff received the news that he had been awarded a Rhodes scholarship . Since 1902 the Rhodes Foundation has awarded full scholarships to young people from Great Britain , the USA and Germany, which enables them to study at the renowned University of Oxford . Bernstorff broke off his agricultural training and enrolled on October 8, 1909 as a student of economics at Trinity College . Most of his services there were rated as “eminently satisfactory” . Bernstorff used the excellent opportunities that Oxford offered him to prepare as well as possible for a possible diplomatic career. In 1911 he was one of the co-founders of the "Hanover Club" , a German-British debating club that was supposed to promote mutual understanding. The first battle of words concerned the subject of "Anglo-German Relations" and was led by Bernstorff. Bernstorff always held a special position among the German scholarship holders at the University of Oxford, also because of his relationship with the "German Oxford Club" , the German alumni organization of the Rhodes Foundation, before which he was in December 1909, a few months after his matriculation , reported on his experiences. At the conclusion of his study visit Bernstorff gave a speech to the name of all scholars Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner , the Governor of the Cape Colony , and the Counselor of the German Embassy London , Richard von Kuhlmann .

In Oxford, ATA, as Bernstorff was called by his first name in Great Britain, made numerous friendships: His fellow students included Adolf Marschall von Bieberstein , the son of the German ambassador to Constantinople , Alexander von Grunelius , an Alsatian nobleman and also later a diplomat, Harald Mandt , later businessman and also a Rhodes scholar, and the Briton Mark Neven du Mont , who rose to become an influential publisher after graduating. Although Bernstorff suffered from severe hay fever , he rowed for his college. At Oxford he developed a deep affection for the British way of life and consolidated his liberal views. Characteristic for this is the strong emphasis on the term “free competition” : In a free competition it should become clear which idea or which person is more suitable or better - not only in business. He had found his political home early on, to which he remained lifelong.

In 1911 Bernstorff graduated in "Political Science" and "Political Economy" . As the essence of his experience in Oxford, he also wrote the text “Des Teutschen Scholaren Glossarium in Oxford” with Alexander von Grunelius , which gave future scholarship holders advice on studying at Oxford and tips on English peculiarities in a humorous way. He not only described the uncomplicated tone and a certain feeling of superiority of belonging to an elite , he made it his own over the years.

Studied in Berlin and Kiel: 1911–1914

The return from Great Britain was not easy for Bernstorff. He first enrolled as a law student at the Friedrich Wilhelms University in Berlin. But from October 1, 1911, he had to do his military service. As a one-year volunteer , he went to the renowned Guard Cuirassier Regiment . After only six months, he was discharged because of hay fever and asthma attacks that resulted from a horse hair allergy. In any case, Bernstorff approached the military with great distance. He went to the Christian Albrechts University in Kiel , where he was able to continue studying law, political science and economics. After the impressions from Oxford, however, Kiel had a provincial effect on Bernstorff. He tried to escape the city as often as possible: He was able to use Stintenburg as a refuge, where he had invited numerous friends since the summer of 1912. He also looked after Friedrich von Bethmann Hollweg , the son of Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg . In addition to Stintenburg, Bernstorff often stayed in Berlin, where he had his first political talks with his uncle Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff . Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff was an influential diplomat and foreign policy advisor to Bethmann Hollweg and at the time the German ambassador in Washington . His liberal views and his experience in diplomacy made him a role model for his nephew Albrecht. “Perhaps the role of the uncle will have a major impact on my life. Everything that I have strived for since I was a child, he actually represents. "

In April 1913 Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff traveled to Great Britain. In addition to visits to Oxford and London, he spent a few days on the Isle of Wight . He became more and more self-doubtful and was afraid that he would never be able to meet the expectations placed on him. The stay in Oxford, in particular, was very emotional for him, which almost resulted in suicide . “As a young man he was soft, easily discouraged and accessible to gloomy thoughts.” Later on, too, he repeatedly suffered from depression and deep-seated fear of not being good enough or of “not leading the right life” . He then tried to compensate for his emotions through increased activity. It was precisely at this time that he decided to become a parliamentarian one day.

As much as Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff saw his years in Kiel as useless, it was then that the deepest relationship of his life developed. He got to know Elisabeth Benvenuta Countess von Reventlow, called Elly, who was married to Theodor Graf von Reventlow, the lord of Altenhof (near Eckernförde) . Bernstorff was frequently visiting Altenhof and he developed a very close relationship with Elly Reventlow. She is "the woman of my life, the great experience of my being" . Even if the two had no love affair - Reventlow was married and loyal to her husband - they managed to maintain a deep friendship between them for a lifetime.

Bernstorff had already presented himself to the Foreign Office on November 1, 1913, where he was advised to come back after his exams. He was able to take this on June 16, 1914 at the University of Kiel and began his legal clerkship at the Gettorf District Court a few days later , which would last until 1915. He tried to be accepted into the diplomatic service after his traineeship, also in order to forestall a threatened military service despite his limited health. On July 14, 1914, he sent his application for admission to the personnel department of the Foreign Office; his uncle Percy Graf von Bernstorff also took influence in his favor. Nevertheless, it was not until January 8, 1915, before Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff was able to start his service: His first post was that of an attaché at the German Embassy in Vienna .

First World War in Vienna: 1914–1917

On August 1, 1914, the First World War broke out. While this put the majority of his contemporaries in a patriotic high spirits, the thought tormented him that he might have to fight himself. “Since I am somewhat lacking in enthusiasm - the war is the specter of my life - against my western neighbors, I do not know whether it is my duty to leave before I am called. [...] It still seems like a bad dream to me that there really is war. ” Bernstorff tried to be able to distract himself by becoming more interested in art. He read the British authors John Galsworthy , Robert Louis Stevenson and HG Wells . He also attended the world premiere of George Bernard Shaw's " Pygmalion " . He found access to German Expressionism through René Schickele and Ernst Stadler , while on stage he was primarily interested in the Art Nouveau poet Karl Gustav Vollmoeller . Bernstorff also dealt with the works of Stefan George , but he rejected his mythical-sacred ideas. He read works by the philosopher Henri Bergson and admired the poems of the Indian Rabindranath Thakur . He was also enthusiastic about Hasidism , a mystical movement in Judaism .

Diplomatic apprenticeship: 1914–1915

Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff was happy to take up his post in Vienna and was happy to be abroad again. The German embassy was headed by Heinrich Leonhard von Tschirschky and Bögendorff , with whom he initially had less to do. After Bernstorff was initially entrusted with purely bureaucratic tasks, he increasingly wished to be able to take on more political tasks. During the first few weeks of his activity in Vienna, he understood that the German representation played a prominent role in the World War. From there, German diplomacy influenced the opinion-forming of the Austrian government and vice versa. In Vienna, Bernstorff experienced the outgoing Habsburg monarchy ; on January 27, 1915, he was presented to the aged Emperor Franz Joseph , whose “aura” deeply impressed him. In addition, he soon got to know influential politicians in Austria-Hungary, including Foreign Minister Stephan Baron Burián , Hofmeister Alfred von Montenuovo and Prime Minister Karl Stürgkh . In terms of content, Bernstorff dealt primarily with Italy in the first few months , which initially remained neutral, but then sided with the Entente with the London Treaty in April 1915 . The embassy tried in vain to prevent Italy from entering the war.

In the winter of 1915, Bernstorff addressed a petition to the Reichstag , naming his function as attaché , in which he requested, on behalf of all German Rhodes scholarship holders, particularly good treatment of all former students from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge who were in German captivity . Bernstorff was admonished for this deliberate breach of duty. His relationships with decision-makers in the Foreign Office and the Reich Chancellery, in particular with Julius Graf von Zech-Burkersroda , Kurt Riezler and Richard von Kühlmann , made a great impression on him, which is why the offense in no way shook his position. In addition, his immediate superior, Ambassador Tschirschky, praised him as an exceptionally gifted young talent and regularly rated him positively.

Politically, he oriented himself towards the bourgeois-democratic Progressive People's Party and, since the outbreak of World War I, supported the truce policy of Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg , whom he viewed with clear sympathy and in whom he had great hopes. As with many liberals, however, Bernstorff's view also changed when Bethmann Hollweg made too great concessions to the Pan-Germans . In the winter of 1915/1916 numerous Austrian dignitaries and German politicians stayed at the embassy, in addition to the Austrian heir to the throne Karl , Kaiser Wilhelm II twice . The events of German liberal politicians, including Bernhard Dernburg and above all Friedrich Naumann, made a special impression . Bernstorff dealt intensively with Naumann's book “Central Europe” , in which he sketched a liberal vision of peaceful competition between nations, but at the same time wanted German hegemony in Europe.

Overall, his political worldview was strengthened by the war: the Battle of Ypres and, from 1916, the Battle of Verdun with its incredible number of victims led to a sharp rejection of the war. Bernstorff wrote: "Whether the social state of the future will not really limit itself to economic struggles, not to organized meanness?" He strongly condemned the views of the military: He called Alfred von Tirpitz 's naval policy "pan-German terrorism" and wanted Tirpitz to the gallows. He feared not only economic misery in the post-World War II period, but also the possibility of political extremes: “The injury on both sides was so infamous that it will never be completely forgotten and the lowest instincts of the masses will always explode Have to be on the lookout. ”In terms of foreign policy, he hoped for a compromise peace with the USA as mediator. Internally, the empire was to be fundamentally reformed and democratized. But that would have required a large, democratic conservative force that could have formed a government together with the liberals. In his opinion, however, the conservatives would have had to distance themselves much more from the growing pan-German nationalism.

“There are moments when I ask myself whether I can stay in the civil service if it goes on like this - it is impossible for me to represent this kind of Germanness, and only the wish not to let myself be sidelined […] and hope holds you in other times. "

On the way to himself: 1915–1917

For Albrecht Bernstorff, Vienna meant much more than politics and diplomacy. During this time he made numerous acquaintances and tried to find his own spiritual path by dealing with art and literature. The circles in which he moved were consistently elitist and characterized by great cultural zeal. He often met with the Austrian liberal politician Josef Redlich , the writers Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Jacob Wassermann, and the banker Louis Nathaniel von Rothschild and his brother Alphonse. Bernstorff was often on the Rothschild estates in Langau in Lower Austria . The young attaché was familiar with von Hofmannsthal's poetry even before he met the poet. Bernstorff was happy about the friendship with him and enjoyed the spirited conversations that strengthened his interest in poetry. The same applies to acquaintance with Aquarius, whose self-discipline he admired. Overall, this period can be described as Bernstorff's “aesthetic years” .

This culminated in a two-week round trip that first took him to Bad Gastein in the summer of 1916 , then to Altaussee , where he met his friends Redlich, Wassermann and Hofmannsthal together with the poet Arthur Schnitzler . Then he went to Salzburg , which he had the writer Hermann Bahr show him. The trip ended in Munich , where he visited Rainer Maria Rilke . This encounter was a formative experience for Bernstorff. Impressed, he acquired all of the poet's works - the basis for his later extremely extensive collection of modern poetry. Until November 1917, Bernstorff saw Rilke several times and then stayed in correspondence with him for longer. He subscribed to the Neue Rundschau and attended classical concerts almost every day, especially Richard Strauss , whose acquaintance he made in October 1916, captivated him. In addition, he observed the works of the young composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold .

In contrast, Bernstorff showed less interest in the fine arts. Only one painter could really inspire him: The Viennese Victor Hammer also created several portraits of the diplomat in 1917, one of which was exhibited at the Vienna Secession . He also traveled a lot: in the three years alone, he took ten vacations to leave Vienna. His destinations were Linz , Marienbad , Pressburg , Budapest , Dresden or Berlin, from where he always made trips to Stintenburg and Altenhof. These happy days of hunting and enjoying nature stood in sharp contrast to his melancholy, lonely disaffection: "There are hours of desperation - not of depression, but of wondering about the seeming senselessness of things, of life." This attitude towards life, the uncertainty about it, whether he was living the “real life” almost drove him to suicide in 1913 and also plagued him in Vienna. He only shared his thoughts with his girlfriend Elly Reventlow, from which he took refuge in work and literature.

In November 1916, Emperor Franz Joseph died , with which Bernstorff's epoch since the French Revolution came to an end, which was later called the long 19th century . He was proud to have met the “last Chevalier” three more times. He also had a positive impression of the young emperor Karl I. After the change of the throne, the new German State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Arthur Zimmermann and Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff traveled to Vienna for his inaugural visit to win the allied Danube Monarchy for unrestricted submarine warfare . Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff tried to influence the views of his uncle Johann Heinrich , at that time the German ambassador in Washington , because the proponents of a negotiated peace resolutely opposed submarine warfare because the United States might enter the war. The decision for the submarine war of January 9, 1917 disappointed Bernstorff deeply; his uncle left Washington after the United States declared war and took up his new post in Constantinople .

In July 1917, Bethmann Hollweg resigned as Reich Chancellor. Bernstorff, who had hoped for more from the Chancellor, initially viewed this as progress. However, he saw the appointment of Georg Michaelis and, three months later, Georg von Hertlings as a political victory for the military and the longer the war lasted, the stronger Bethmann Hollweg again appeared to him in a positive light. He saw the Russian February Revolution as "the beginning of the end [...] of civil society" and feared effects on the German Empire. Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff said that Germany should carry out reforms for democratization as an advance payment for a possible peace of understanding internally - this is the only chance to end the war and at the same time preserve the monarchy. In his opinion, the power to make this possible could only come from southern Germany, “where that Germanism which Goethe embodies for us most still exists, [...] the profound abundance of life, poetry, music, humanity, philosophy, art . ” Bernstorff had developed into a “ realpolitical pacifist ” .

The young diplomat in Berlin and Koblenz: 1917–1922

Foreign Office until the Revolution: 1917–1918

In 1917 the Foreign Office called Bernstorff for further training at the Berlin headquarters. He first got into the legal department, which seemed to make his efforts to get into the economic policy department in vain. Bernstorff went to the State Secretary Richard von Kühlmann , who ordered a transfer to the economic policy department. There Bernstorff dealt with the preparation of a stronger economic cooperation between the German Reich and Austria-Hungary based on the "Central Europe" idea. A little later, however, he was transferred to the political department under Leopold von Hoesch , where from now on he worked in the immediate vicinity of Kühlmann. At this point in time, the department was mainly busy preparing the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty . Bernstorff was not directly involved in the negotiations as an attaché, but stayed in Berlin. There he became a member of the German Society in 1914 , where the prospects of a post-war Germany were discussed across political directions. The elite club was chaired by the liberal diplomat Wilhelm Solf . In addition, together with friends, he visited the former chancellor Bethmann Hollweg several times, to whom he now again attached high statesmanlike skills and basic ethical values, at his retirement home in Hohenfinow . In addition, in 1917, as a young landlord, Bernstorff was elected to the Lauenburg district council according to the three-class suffrage, to which he belonged until its dissolution in March 1919.

In April 1918 he accompanied Richard von Kühlmann on his inaugural visit to the court in Baden . On this occasion, Bernstorff also met the liberal Prince Max von Baden . The following month he was a member of the German delegation to the peace negotiations with Romania in Bucharest , which he valued as the greatest diplomatic success of the Central Powers. There he acted as personal aide to the State Secretary. At the beginning of June 1918, Kühlmann stood before the Reichstag to demand stronger support for a negotiated peace from the left, which Bernstorff welcomed. At a reception following the Reichstag session, he met numerous influential parliamentarians, including the Social Democrats Friedrich Ebert , Philipp Scheidemann , Albert Südekum and Wolfgang Heine , the liberal Conrad Haussmann and the center politician Matthias Erzberger .

At the beginning of October 1918, Bernstorff traveled to Vienna, where he was present for the cabinet draft of the last kuk government. His friend Redlich took over the finance department in Max Hussarek von Heinlein's government . When he returned to Berlin, the October reform had transformed the Empire into a parliamentary monarchy . The new foreign state secretary was Wilhelm Solf, the previous head of the Reich Colonial Office , whom Bernstorff described as follows: “Solf is of course a pleasure for me - if I were 10 years older, I would be in the government too .” Until his resignation, he worked more personally as Solfs Adjutant. The affairs of government were run by Max von Baden, in whom Bernstorff, like many liberals, placed great hopes on the preservation of the monarchy in a liberal-democratic empire ( "The old German line that led to Paulskirche and broke off in 1848. " ). In the last days of the Hohenzollern Empire, on November 8, 1918, Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff was appointed secretary of the legation and thus taken over into the civil service after completing his training.

November Revolution and DDP 1918–1920

The November Revolution refused Albrecht von Bernstorff initially off when he saw his democratic ideas realized in a parliamentary monarchy. He could not gain anything from the revolutionary, even if he realized that no peace agreement could be reached with Wilhelm II. For him, with the failure of Prince Max von Baden, the ideas of liberalism in a monarchy had been buried, and now it was necessary to fight for a bourgeois party within the republic. A group of diplomats was formed around the young Foreign Office employee, Kurt Riezler , who wanted to give democracy more salary against the radical forces. Since they still refused to found their own party, Bernstorff, like his uncle Johann Heinrich, planned to join the Progressive People's Party and run for it, but this was not implemented. On November 16, 1918, the group addressed the public with the appeal “To the German Youth!” In the Berliner Tageblatt, invoking the “spirit of 1848” and calling for the end of all class privileges. In addition to Bernstorff and Riezler, the signatories also included Oskar Trautmann and Harry Graf Kessler .

Instead of receiving the status of the big liberal party, as planned at the beginning, the Progressive People's Party was instead given the newly founded German Democratic Party , which Bernstorff now joined with his uncle. He was proud of this new bourgeois party and the Democrats had prominent names in their ranks, including Solf, Haußmann, Payer and Dernburg . In his typical humor, Bernstorff wrote ironically: “Founding of Uncle Johnny's Democratic Club, which promises to become really Semitic-capitalist. We younger people will represent the radical anti-capitalist left. ” On December 18, 1918, under pressure from the USPD , Wilhelm Solf handed over the official duties to Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau . Relations with Rantzau worsened when the latter refused to transfer Bernstorff to the German embassy in Paris . Instead, he was offered a transfer to the German embassy in Prague , which he did not like. When Solf was discussed as ambassador in London in June 1919, Bernstorff also tried to profit from it. By spring 1920 he had held at least five different positions in the Foreign Office since leaving Vienna, which does not speak in favor of a forward-looking personnel policy.

On September 10, 1919, Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff was sworn in to the Weimar Constitution . He had recognized that there was no going back for Germany and developed into a Republican of reason . At the beginning of 1920 he took over the foreign trade office of the Foreign Office, which had been in existence for a year, where he dealt with the economic expert Carl Melchior . However, he always expected to be transferred abroad soon. The paperwork and the little political work annoyed him, but overall he now had more leisure again. Only the Kapp putsch , which he called a “stupid boy prank” , ensured that the government authorities were temporarily relocated via Dresden to Stuttgart for a few days. For him, however, even this seemed "very exciting and very entertaining" .

Diplomat in his own country: Koblenz 1920–1921

In mid-April 1920 Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff went to the " Inter-Allied Rhineland Commission " in Koblenz as legation secretary and employee of the secret legation councilor Arthur Mudra . In the first few weeks of his activity at the occupation authority of the victorious powers , he still represented his superiors before he was appointed the new "representative of the Foreign Office at the Reich Commissioner for the Occupied Rhenish Territories" on May 11th . Bernstorff was now able to do his work more freely. “Have good rapport with the British and Americans - I do a lot of politics and few files.” He also enjoyed getting to know West Germany, which was largely unknown to him. On business, he often traveled to Darmstadt , Frankfurt and Cologne . In addition, he gave regular lectures to Reich Foreign Minister Walter Simons and Chancellor Constantin Fehrenbach . "People in Berlin seem to be very satisfied with me, they also support me, want to leave me there for the time being, were generally very appreciative."

His duties in Koblenz included taking part in the meetings of the “Parliamentary Advisory Council for the Occupied Rhenish Territories” and its economic committee. Diplomatically, he was clearly oriented towards the line of German foreign policy. However , he was critical of the London ultimatum and the reparation payments, as he found it paradoxical to continue the policy of compliance until the entire economy was collapsed in order to then present the result of the reparations claims to the victorious powers. For this reason, he hoped for a gradual departure from the policy of compliance and an alternative settlement with the Entente. In this spirit, Foreign Minister Friedrich Rosen sent him to London in June 1921, where he attempted to influence the Foreign Office in a number of talks . He also met with the head of the opposition liberals, former Prime Minister Herbert Asquith . Before his trip there had been rumors that Bernstorff was to be appointed consul to Glasgow . But since the London ambassador Friedrich Sthamer had concerns about the name Bernstorff, because Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff had advocated an understanding during the World War and thus against a British victory peace, this idea was dropped again. So it was easy for Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff to increase his independence from the Foreign Service at this point in time, when he was sure to remain in Koblenz. On July 27, 1921, he therefore applied for a year's leave of absence for a traineeship at the bank "Delbrück, Schickler & Co." . Although attempts were initially made to dissuade him from this plan, it was finally accepted. At the same time, Minister Friedrich Rosen praised Bernstorff's large “radius of action” and regarded his work in Koblenz as extremely successful.

Delbrück, Schickler & Co .: 1921–1922

His work at the Delbrück, Schickler & Co. bank began on November 28, 1921. However, he had no specific tasks at the bank, as he was only supposed to find out about the various departments and not work himself. Due to numerous social obligations, he still felt rushed and "eaten up" . He stayed with Kurt Riezler, where he also met his father-in-law Max Liebermann , Hermann von Hatzfeldt , Gerhard von Mutius and the State Secretary in the Reich Chancellery Heinrich Albert . Bernstorff was part of the capital's “high society” - despite his sometimes precarious financial situation .

Bernstorff called the conclusion of the Treaty of Rapallo on April 22, 1922 a "stupidity" . He jokingly wrote about Foreign Minister Rathenau : “Walther does not protect against foolishness.” However, when Rathenau fell victim to a fememide just a month later , Bernstorff spoke of a “beast that is caused by the excessive incitement of the right” . Employment at the Delbrück bank had only been planned for one year from the start, and when that time ended, Bernstorff hesitated to return to the diplomatic service. The alternative for him was a permanent job in a bank abroad. But when the human resources department of the Foreign Office offered him a position at the German embassy in London , he accepted.

Diplomat in London: 1923–1933

"Bernstorff did more than any other German personality to ensure that English-German relations were constantly improving."

The first years: 1923–1928

Representative of the Weimar Republic

Bernstorff arrived in London on January 20, 1923. His departure had been delayed several times by the occupation of the Ruhr . He took over the post of 2nd secretary under Ambassador Friedrich Sthamer. From the beginning he was dissatisfied with this position. In the following years he was repeatedly shown opportunities for advancement at other embassies, for example in Copenhagen under Ulrich von Hassell . However, Bernstorff insisted on remaining in London, often threatened to leave the diplomatic service and also accepted a rather slow career.

After a few months he found Sthamer to be an unsuitable man: he had done a good job in the years after the World War, but was now too cautious and represented nothing socially. Bernstorff proposed Harry Graf Kessler as his successor. However, it took years before a successor was appointed. Over a long period of time, Bernstorff undermined the ambassador's authority in correspondence with the Foreign Office, since he considered him unsuitable and also longed for his departure because of his own hopes for advancement. A wage cut of 10 percent because of the tight budget situation in the empire created additional difficulties for Bernstorff, who was already suffering from financial problems due to the poor running of the estate in Stintenburg. As a result, he has now been forced to borrow money from relatives or to sell family-owned jewelry. The hyperinflation also contributed to the financial woes. Bernstorff did not try to limit his luxurious lifestyle either.

His area of responsibility was in the political department, where he worked with Otto Fürst von Bismarck . The central issue was the attempt to draw closer to Great Britain in order to end the occupation of the Ruhr as early as possible and at the same time to isolate France politically. In order to achieve this, Bernstorff believes that Germany must join the League of Nations “for tactical reasons” . He also advertised this position in an article in the newspaper "Deutsche Nation" . Bernstorff expected that the occupation of the Ruhr would continue for years, which is why he welcomed a gradual withdrawal of the troops. After a careless statement in this direction, which was printed in a press release as the official position of the Reich government, Bernstorff received a reprimand from the ambassador. In early 1924, Bernstorff represented the Weimar Republic in the German-British aviation negotiations that were part of the disarmament of the German Empire. He remained preoccupied with this matter for months. In addition, Bernstorff worked on behalf of the "Economic Political Society" in numerous campaigns to improve the German image with regard to the economy, including book publications, trips by prominent Germans to London or the British to Berlin (e.g. Graham Greene ) or financial support for the work of the journalist Jona von Ustinov , with whom he was also a friend. In 1927 Ustinov visited Stintenburg with his wife and son Peter .

From July 16 to August 16, 1924, the London conference on a new reparations agreement took place. From August 6th, German delegates also sat at the negotiating table: Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Marx , Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann with State Secretary Carl von Schubert , Finance Minister Hans Luther and Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht . Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff took part in the conference as a representative of the German embassy. The negotiations concluded with the Dawes Plan , which Bernstorff considered to be progress, although it was not entirely satisfactory. In April 1925, he judged the possible election of Paul von Hindenburg as Reich President extremely critically with a view to the foreign policy perspectives: “The entire capital of trust that has been accumulated between Germany and England over the course of five years will only be gained if Hindenburg is elected go to the rushes all too quickly and Germany will [...] once again be the embarrassed one. ” But despite the election of Hindenburg , his foreign policy pessimism was initially not confirmed. Instead, the rapprochement succeeded in culminating in the Locarno Treaty , which he recognized as a great achievement of Stresemann. In 1926 he became chairman of the German pro-Palestine committee , which campaigned for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine.

Personal contacts as the basis of diplomacy

His numerous personal contacts were important for the work of the diplomat Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff: In addition to the old friendships from his Oxford study days, he continued to cultivate his connections with the Foreign Office, especially with Kurt Riezler and Friedrich Gaus ; next to Wilhelm Solf, meanwhile German ambassador to Japan , whose wife Hanna visited him with daughter Lagi in London, also to Hjalmar Schacht , Theodor Heuss and Siegfried von Kardorff . Contacts with Foreign Office staff and members of the House of Commons , such as Philip Snowden and Herbert Asquith, were particularly important . New friendships often led Bernstorff to Cambridge , where he a. a. met the influential literary critic Clive Bell . He belonged to the upscale Toby's Club in London and played tennis at the Queen's Club . Through the embassy's cultural work, he met Lion Feuchtwanger , John Masefield and Edith Sitwell . The Ascot horse race , the Chelsea Flower Show and the Wimbledon Championships were, of course, highlights of social life for Bernstorff. All in all, he was one of the few Germans among the welcome guests of the British elite and was also able to use this for diplomacy.

On the upper level of world politics: 1929–1933

Chargé d'affaires of the embassy

At the beginning of 1929 there was movement in personnel policy when Ambassador Sthamer, now 72 years old, announced his resignation and the Foreign Office was now officially looking for a successor. In conversation were Harry Graf Kessler, the conservative Reichstag member Hans Erdmann von Lindeiner-Wildau , the previous ambassador in Stockholm Rudolf Nadolny and the ambassador in Rome Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath . The choice fell on the latter, who took office in London on November 3, 1930. At the same time as Sthamer, the Counselor Dieckhoff was withdrawn, whose representation was taken over by the Counselor II. Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff. He hoped for a permanent appointment to this post and thus for his ascent into the “innermost engine room of the diplomatic world machine” . On February 12, 1931, the intended promotion actually took place, in which he was able to jump a rank of the diplomatic career ladder.

In German foreign policy, Foreign Minister Julius Curtius put more emphasis on the revision of the Versailles Treaty , which led to a departure from the Stresemannian understanding with France. At the same time, Bernstorff observed the rise of National Socialism with concern. In Great Britain, the June 1929 election had left things unclear: for the first time, the Labor Party appointed Ramsay MacDonald as prime minister in a minority government tolerated by the liberals . In view of the global economic crisis , however, this proved to be completely overwhelmed, which is why the three big parties, Conservatives, Liberals and Labor, formed a coalition. MacDonald's so-called "National Government" developed into an almost purely conservative government due to numerous party withdrawals on the part of the left. These events also caused unrest in the German embassy, as they led to great uncertainty in German-British relations.

In 1930 the fleet conference took place in London , at which representatives from the USA, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and Great Britain were involved. There, the great powers extended the construction break for warships until 1936 and banned the use of submarines entirely. Overall, however, the foreign policy sentiment was different than in Locarno: “We have reached a point where a policy of understanding, with the best will of the leaders, is made impossible by the yelling of the masses. […] That can end tragically for Europe. ” In October 1930, an article by Bernstorff appeared in the Daily Herald under the title“ All in a Diplomat's Day ”. In a gloss of the same paper, Bernstorff was described as the foreign diplomat who had best integrated into London society. "Everyone knows him because he wants to know everyone himself."

Ambassador Neurath had been on vacation since the beginning of August 1931, which is why Bernstorff took over the business for several months. He enjoyed the independence that he had as chargé d'affaires. In January 1932 Neurath fell ill for four months and Bernstorff was again able to act as chargé d'affaires. In addition, rumors from Berlin increased that after Foreign Minister Curtius Neurath would be acting as his successor after the resignation . First of all, Chancellor Heinrich Brüning himself took over the external department. But after the change of government, Neurath traveled to Berlin on June 1, 1932 to negotiate his entry into the Papen cabinet . Two days later he returned to London to take his leave at the embassy. His two years of service in London were largely absent. Until a new ambassador was appointed, Bernstorff was once again the embassy's chargé d'affaires. His social and political contacts had already made the connoisseur of English conditions the real master of the embassy.

Re-establishment of the Rhodes Scholarships

Since his return to Great Britain, Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff has been busy restoring the Rhodes scholarships for German students. Since 1916, when Great Britain was at war with the German Empire, the Rhodes Foundation had suspended scholarships for German students. Although the former scholarship holders continued to be invited to events in Oxford and friendly contacts were maintained, the desire for new German scholarship holders met with strong resistance.

Bernstorff was able to use his contacts effectively to reestablish the scholarships: The foundation member Otto Beit and the influential journalist and politician Philip Kerr, 11th Marquess of Lothian , particularly promoted the idea. On the German side, the industrialist Carl Duisberg supported the project. Richard von Kühlmann and Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, also promised to raise funds in Germany and Great Britain. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Rhodes Foundation in June 1929, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin announced the establishment of two new scholarships for two years. The fact that these were officially two new scholarship places meant that a parliamentary debate could be skilfully avoided. Crown Prince Edward agreed to this step. This event was very well received by the British public. At the same time, the Rhodes Foundation informed the old German scholarship holders in confidence that there should be a purely German selection committee and that the number of scholarships would be increased to five in the long term.

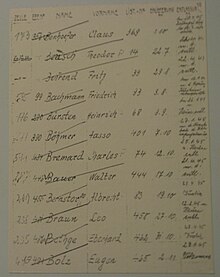

On July 15, 1929, Bernstorff sent a memorandum to Oxford in which he made suggestions for the composition of the selection committee: In addition to four former scholarship holders, three independent members were to be appointed; for this post he recommended Friedrich Schmidt-Ott , the last royal Prussian minister of culture, Adolf Morsbach from the board of directors of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and his own sponsor Wilhelm Solf. In September, Bernstorff modified his proposal and brought other names into the discussion. The trustees largely followed his recommendations and on October 10, 1929 appointed Schmidt-Ott, the former Foreign Minister Walter Simons , Adolf Morsbach, the lawyer Albrecht Mendelssohn-Bartholdy , the political scientist Carl Brinkmann and Bernstorff's college friend Harald Mandt . For his unauthorized approach, Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff had to take harsh criticism from the former German scholarship holders. In addition, the Oxford graduate and German national Reichstag member Lindeiner-Wildau feared that the DDP would have too much influence on the selection committee. Well-known politicians were always invited to the meetings of the committee, which took place annually from now on: Reich Chancellor Brüning appeared in 1930, Foreign Minister von Neurath and Finance Minister Graf Schwerin von Krosigk came in 1932 . This shows the importance that politics attached to the Rhodes Foundation and what diplomatic success Bernstorff had achieved against this background.

At the meeting of the selection committee in 1930 he met the young Adam von Trott zu Solz , who was applying for a scholarship. Bernstorff liked the "really very special routine" , whose skills he recognized and promoted. A friendship developed between the two, which they deepened through regular meetings in Oxford and conferences in Cambridge . The Rhodes Foundation brought together two men who later actively resisted Nazism as uncompromising opponents and were executed for it.

Turning point in 1933

"I cannot represent a Germany that is being transformed into a barracks yard abroad."

At the beginning of 1933 Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff was able to celebrate his tenth anniversary of service at the Embassy in London, which was honored with an article in the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung . But the rise to power of the NSDAP on January 30, 1933 was a great shame for Bernstorff: He is now ashamed to be German, since “this Austrian munchkin” Adolf Hitler had succeeded in “seducing” the German people . Bernstorff now wrote numerous letters to the Foreign Office in which he wanted to show the chief diplomats the negative effects of the seizure of power: Almost all politicians who were formerly pro-German politicians railed against the Reich, and public opinion in Great Britain was said to be raging because of a single factor, the Anti-Semitism , don't improve again. Because of his oppositional stance, journalists from Völkischer Beobachter blackened Bernstorff on March 26th against Nazi foreign politician Alfred Rosenberg .

Contrary to the assumption widespread among contemporary witnesses, Bernstorff did not quit the service himself, although he thought about it intensively in March 1933. In May 1933 he took a two-week vacation to meet his friends Eric M. Warburg and Enid Bagnold on Stintenburg . About a month after he had resumed his work in London, news reached him on June 24, 1933 that he would be recalled from his post. Bernstorff was surprised by this decision and extremely depressed. His dismissal met with strong coverage in the British press: The Times , The Observer , Daily Telegraph , Morning Post , Evening Standard, Daily Express and Daily Herald reported on it and spoke of the beginnings of a political cleansing in German diplomacy. Articles about Bernstorff's departure were also found in the German press, namely in the Vossische Zeitung and the Frankfurter Zeitung - extremely unusual for a counselor and proof of Bernstorff's prestige and success.

On the other hand, he did not see himself as a victim of the National Socialists, but attributed his recall to an intrigue in the Foreign Office to enable Otto Fürst von Bismarck to rise to his post. After a trip to Berlin, he gave several farewell dinners in London at the end of July 1933. The culmination of this farewell was his reception by Prime Minister MacDonald on August 8th - an honor normally reserved exclusively for outgoing ambassadors. He was then given a further month's leave before he found out at the end of August that he would either be the consul general in Singapore or that he would be given temporary retirement. Although the latter took place in autumn 1933, Bernstorff hoped for several months to receive better job offers from the Foreign Office and to return to the diplomatic service as soon - despite persistent political reservations. It was not until December that he realized: “Now the die has been cast. [...] The Foreign Office is far too afraid to offer me even one position. "

Period of National Socialism: 1933–1945

“Intellectual honesty is more important to me than a career. National Socialism is directed against everything that I have always stood up for: 'Spirit', tolerance, insight and humanity. "

Inner emigration and AE Wassermann

Bernstorff had never felt comfortable in Berlin, but now the capital seemed to him to be his exile, where he could only “vegetate” , no longer “live” . Although he continued to cultivate his numerous friendships, he took refuge from the political situation in Germany, mainly on trips abroad. At the beginning of 1934 he returned to Great Britain to meet friends again and to hold talks for the Rhodes Foundation, then he traveled to his uncle Johann Heinrich, who - himself a staunch opponent of the Nazi regime - had emigrated to Switzerland. For Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff, however, emigration never seems to have been an alternative, as he felt obliged to Germany and especially to his home town of Stintenburg. Despite his mental depression, Bernstorff succeeded in 1933 and 1934 in making more and more acquaintances with women of the same age and in considering marriage.

A previous relationship was also revived. In 1922 he met the then actress Ellen Hamacher in the spa town of Weißer Hirsch near Dresden. She had been married to the composer and conductor Rudolf Schulz-Dornburg (1891–1949) since 1926, and in 1929 the couple also had a son, Michael. Nevertheless, there were still contacts between Bernstorff and Ellen Schulz-Dornburg; in March 1937 a second son was born, Stefan. Bernstorff unofficially confirmed paternity. Even if he never officially recognized the child - probably out of consideration for the continued marriage of the Schulz-Dornburgs - the circumstances in both families had been known by 1942 at the latest; Bernstorff supported the Schulz-Dornburgs financially and considered the illegitimate son in his will with a sum of money. Stefan Schulz-Dornburg himself only found out about Bernstorff's paternity in 1962.

It didn't take long before he found a new job and ended his inner emigration. On March 1, 1934, Count Bernstorff entered the service of the traditional Berlin bank AE Wassermann . The company headquarters was at Wilhelmplatz No. 7, right next to the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda . A decisive factor in joining the bank was Bernstorff's personal acquaintance with co-owner Joseph Hambuechen, whom he met in London in 1931. The private bank AE Wassermann had a turnover of 13 million Reichsmarks in 1937, which indicates a relatively small institute. The bank, with branches in Berlin and Bamberg, was still majority owned by the Jewish Wassermann family. When the managing director Max von Wassermann died in October 1934 and his son Georg took over the post, Bernstorff was promoted to “General Manager” of the bank on May 1, 1935 . Now he was the only non-family member in the company's management to have a high fixed salary and was hoping to found a branch or subsidiary in London or Washington, which he could manage.

In addition to the uncertain situation since leaving the diplomatic service, the need to help Jewish friends was also important for his entry into the private bank. Entering a non-Aryan bank according to the Nuremberg race laws was an act of refusal to accept the Nazi ideology and therefore associated with considerable dangers. Since the seizure of power, AE Wassermann brokered business for the Palestine Treuhand-Gesellschaft , which granted cheap loans to emigrants to Palestine through currency trading . In addition, the Treuhand-Gesellschaft enabled money to be transferred to Palestine by buying and selling goods in different currency zones. Together with the former center politician and diplomat Richard Kuenzer , Bernstorff supported the Alija Bet and helped to save Jewish capital from the Nazi regime.

From 1937 AE Wassermann got into trouble because of its Jewish owners, which is why most of the family members left the board and were replaced by external, “Aryan” partners. However, this basically did not change the situation and in June 1938 the bank gave in to the pressure of a threatened full Aryanization . Bernstorff was now a co-owner, but saw himself as a “trustee” who would return the company's business to the rightful owners after the end of National Socialist rule. The forced exit of the Jewish business partners weighed heavily on him. On March 24, 1937, Bernstorff was put into permanent retirement from the diplomatic service at his request. He now traveled frequently through Germany on business, not least as a member of the supervisory boards of numerous companies: AG for medical products (Berlin), exhibition hall at Zoo AG (Berlin), Concordia-Lloyd AG for building society savers and basic loans (Berlin), "Eintracht" lignite works and briquette factory ( Welzow ) and Rybnik Coal Company ( Katowice ). In 1937 he attended the World Exhibition in Paris .

Resistance to the regime

“[…] And the nameless misery of the Jews, who are now being transported eastwards in certain batches every night, people without property or names, from whom everything is taken away. The beast is racing. "

Open rejection

Bernstorff had recognized the danger of a National Socialist takeover of power before 1933, but expected the dictatorship to collapse quickly in the first years of Nazi rule. He believed in the possibility of a quick return to the republic or even a parliamentary monarchy. Crown Prince Wilhelm continues to receive more applause than the "philistine dictatorship" . He felt that those in power were ridiculous and made fun of them in conversations and letters, which increasingly put him in danger. He always called Adolf Hitler "Aaron Hirsch" in correspondence with friends . The staged Röhm putsch gave Bernstorff the impression that the end of the regime was imminent. For him, the methods of the National Socialists were the same as those of the Soviet Cheka , and he did not trust the German people to tolerate such a regime in their country for long.

The more the National Socialist dictatorship consolidated, the greater Bernstorff's desperation became. National Socialism was the "triumph of the mediocre man" and he could hardly see any differences between fascism and communism . Bernstorff was certain that the outbreak of war would not be delayed for long. The invasion of Austria and the attack on Poland on September 1, 1939 confirmed his fears and his rejection of those in power. In his circle of friends in Germany and Great Britain he told jokes about the leading representatives of the dictatorship: “Why does Adolf Hitler fail every woman? - He is waiting for Saint Helena ” ; “A bomb hits Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin . Who survived - Europe. ” While most of the Nazi-critical Germans only told such jokes behind closed doors, Bernstorff did it publicly and without hesitation. It was precisely through this that he tried to relativize the view of those in power while at the same time bringing himself into the field of vision of the Gestapo .

Contacts with resistance groups

Bernstorff had a large number of contacts in the offensive resistance against National Socialism. The friendship with Adam von Trott zu Solz was his most important contact with active forces who wanted to overthrow the Nazi dictatorship. Trott and Bernstorff were in contact simply through their joint activities on the Rhodes Committee, but Trott was also a regular guest at Bernstorff and received recommendations and contacts from him that were useful for his career, such as the placement of a traineeship with the lawyer Paul Leverkuehn . In addition, Bernstorff sought connections to Nazi-critical journalists such as Paul Scheffer and Friedrich Sieburg . After all, he was also connected to the Kreisau Circle through Trott and maintained contacts with conservative critics of the war against Russia around Ernst von Weizsäcker .

Bernstorff had already been a regular guest in the SeSiSo Club in the 1920s and was now also a member of the Solf Circle , which had formed around the widow of the former Foreign Secretary, Hanna Solf . The individual participants in the tea societies in the Solf's house on Alsenstrasse in Berlin had contacts with other resistance groups and helped the persecuted. While Trott only appeared now and then, Bernstorff belonged to the core of the circle, which, although no overturning plans were developed in the Solf circle, is one of the most important groups of the bourgeois-liberal and aristocratic opposition to National Socialism. Many former colleagues from the Foreign Office also came together in the Solf Circle. The members included a. Richard Kuenzer, Arthur Zarden , Maria Countess von Maltzan , Elisabeth von Thadden , Herbert Mumm von Schwarzenstein and Wilhelm Staehle . The members of the district were only indirectly involved in the planning for the attempted coup of July 20, 1944 . Bernstorff himself sought closer contact with the Kreisau Circle through Trott, whose progressive ideas interested him. But precisely the qualities that were useful to him as a diplomat, his openness, talkativeness and sociability, precluded participation in the circle of conspirators on July 20: Helmuth James Graf von Moltke and Adam von Trott rated him as a security risk for the resistance and Bernstorff's direct involvement in Kreisau or in the circle around Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg did not materialize.

Contacts abroad

Bernstorff continued to have numerous connections abroad and tried to help the British, Americans, Dutch, Danes, Swiss and French to gain a truthful image of Germany. For example, he tried to report on the crimes of the National Socialists in the Evening Standard . Concern for his safety, however, Bernstorff's British friends prevented the publication. He warned the Danes and Dutch of the impending raids. Together with Adam von Trott, Bernstorff tried until the outbreak of war to protect the Rhodes Foundation's selection committee from interference by those in power, which did not succeed. The British in particular, especially Lord Lothian, a leading head of appeasement politics, underestimated the risk that Nazi Germany posed. Bernstorff also kept in touch with the former Chancellor Joseph Wirth, who was living in exile in Lucerne, and saw himself as a liaison between him and the Kreisau Circle.

Support for the persecuted

Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff actively helped people who were persecuted by the National Socialist regime - not only through his work in the bank “AE Wassermann” , but also through direct help, such as keeping Jewish friends hidden. His support for his long-time friend Ernst Kantorowicz , whom Bernstorff had stayed with since he had heard that the Reichspogromnacht was to take place, is well documented. With his support, Kantorowicz managed to leave Germany in 1938 and survive the Holocaust in America. He also hid Jona von Ustinov (1892–1962) with his wife Nadja and his son Peter in his Berlin apartment and on Stintenburg . Bernstorff also helped out when the Liebermann villa , which once belonged to Max Liebermann , the deceased father-in-law of Kurt Riezler, who has now emigrated, was sold. He also tried to obtain visas and passports for Jewish Germans, including Martha Liebermann - in this case ultimately unsuccessful: she committed suicide before she was threatened with deportation to the Theresienstadt concentration camp . The full extent of Bernstorff's help for those persecuted by the National Socialists has only been researched in part and therefore cannot be adequately reconstructed.

Imprisonment in Dachau concentration camp

On May 22, 1940, Count Bernstorff returned to Berlin from a trip to Switzerland on which he had also met Joseph Wirth, where he was arrested by the Gestapo in his apartment. After he was first taken to the Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse prison, he was transferred to the Dachau concentration camp on June 1, 1940.

The official justification for his detention in various sources is the allegations of alleged foreign currency offenses in connection with an alteration of his will (not personally affecting him), an allegation of homosexual acts and his return a few days late, which were already raised during an interrogation on May 3rd called Switzerland. What is certain is that he was not accused of his connections abroad and related activities in the previous months, which could have been viewed as treason.

Bernstorff himself was convinced that his arrest had been carried out by his sister-in-law, Ingeborg Countess von Bernstorff (1904–1982). She was the widow of his younger brother Heinrich (1891-1935). From the marriage came a son born in 1929 - the only (officially recognized) male descendant of the Bernstorff-Stintenburg line. When the land law was changed in 1938 and the family entailment commission no longer existed, the whereabouts of the Stintenburg property, which until then automatically fell to this nephew Bernstorff's inheritance, was no longer clarified. Bernstorff's sister-in-law feared for her son's inheritance and felt that this assumption was confirmed by the fact that her son was not included in the will of an aunt Bernstorff (Helene von Hottinger) who died in January 1940. In the case, she accused Bernstorff of influencing her son.

Ingeborg Gräfin von Bernstorff, a member of the NSDAP since April 1933, had good contacts with leading National Socialists. Heinrich Himmler was a benevolent acquaintance of her. She had a particularly close relationship with the SS officer and head of the Adjutantur of the Reichsführer of the SS, Karl Wolff , whom she had met in 1934 and whose lover she had become after her husband's death; In 1937 she had given birth to a son and in 1943 she was to marry Wolff. Karl Wolff had already created a file on Bernstorff in 1935, which contained a number of documents on the question of inheritance. Since 1939 at the latest, he has been supporting Bernstorff's sister-in-law in her attempts to secure Stintenburg as her son's heir. According to prevailing opinion, Bernstorff's arrest on May 22, 1940 was the result of denunciation and instructions from Countess von Bernstorff and Wolff.

Immediately after his arrest, Bernstorff's sisters and Countess Reventlow tried to get him released. A lawyer initially engaged was unsuccessful. Bernstorff's friend Hans-Detlof von Winterfeldt then entrusted Carl Langbehn with the matter. Langbehn negotiated several times with the Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler , with Reinhard Heydrich and Wolff. When it became clear that the conclusion of an inheritance contract was a condition for a release, Langbehn persuaded the imprisoned Bernstorff to sign. After he made his promise to give up the resistance against his sister-in-law, he was released on Friday, September 27, 1940, and on Tuesday, October 1, 1940, a contract of inheritance was concluded that favored his nephew. In his later will, Bernstorff did not change the favoritism of the nephew, but described the contract of 1940 as "blackmailed", made the property subject to the execution of the will until the nephew's 30th year (1959) and gave the executors the duty to Ingeborg Countess von To deny Bernstorff access to Stintenburg until her death. In 1964, Karl Wolff was charged in Munich with numerous crimes during the Nazi era; In these proceedings Winterfeldt confirmed the involvement of Bernstorff's sister-in-law and Wolffs in the arrest and release of Bernstorff in 1940. Only the statute of limitations saved Wolff from being charged in this case.

After his release, Bernstorff immediately resumed work in the bank, despite his physical and mental changes since his imprisonment in the concentration camp. Traveling abroad was now only possible with special permits, as he had to hand in his passport. Until his death, Bernstorff traveled twice to Switzerland. Otherwise he gave his acquaintances letters to friends abroad and received information in this way. These connections abroad came together in the circle around Hanna Solf, to which Bernstorff belonged. Bernstorff now met again with Adam von Trott, who reported on the ongoing planning for the assassination attempt on Hitler . Via Richard Kuenzer , the Solf Circle also had contacts to Carl Friedrich Goerdeler , who would have been appointed Chancellor after a successful coup. Although Bernstorff now had to be more cautious because he was being watched by the Gestapo, he continued to meet with leading conspirators on July 20: he met the foreign politician Ulrich von Hassell , Otto Kiep , an employee of Wilhelm Canaris , and Rudolf von Scheliha on a regular basis. He also continued his humanitarian aid for the persecuted whenever he could.

Again imprisonment and murder

When Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff returned from his last trip to Switzerland in July 1943, he was arrested by the Gestapo and, like three years before, taken to the prison on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse . There is no conclusive evidence of the reasons for his arrest. It is initially suspected that there was a connection with the statements of clergyman Max Josef Metzger , extorted under torture , who was arrested while trying to deliver a pacifist memorandum to the Swedish bishop of Uppsala and who was interrogated and a. Richard Kuenzer weighed heavily. Kuenzer's arrest took place on July 5, 1943, and Bernstorff's 25 days later. Other reasons could be the investigations against several members of the Abwehr under Canaris, such as Hans von Dohnanyi , or the activities of Carl Langbehn. The increasing observation of the Solf circle by the Gestapo also comes into consideration.

Bernstorff's biographer Hansen considers the continuation of the dispute with Ingeborg Countess von Bernstorff to be conceivable as a reason for his second arrest. Bernstorff's defender, Hellmuth Dix, indicated this possibility. There had been disputes over Stintenburg between the two even after the contract of inheritance was signed (1940). Bernstorff himself reported in 1941 that his sister-in-law was still inciting against him on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse (headquarters of the Gestapo and SS). During his time in the Ravensburger concentration camp, Bernstorff also stated that he had been arrested because Wolff wanted his property.

In the later indictment, Bernstorff is accused of belonging to the Solf circle and of his anti-state views expressed there. The Nazi authorities had been investigating Hanna Solf for some time, and Metzger's arrest had clearly reinforced the suspicion. On September 10, 1943, the “tea party” around Hanna Solf was dissolved due to denunciation by the Gestapo spy Paul Reckzeh . Since Bernstorff was already in custody at this point in time, it seems unlikely that he as an individual member would have been denounced by the informant and therefore arrested by the authorities before this date. A final clarification of the reasons for his second arrest on July 30, 1943 is not possible due to the limited sources.

It was not until September 1944 that the six defendants Hanna Solf, Richard Kuenzer, Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff, Friedrich Erxleben , Lagi Countess Ballestrem and Maximilian von Hagen were questioned. The investigation was led by Herbert Lange , who hoped the interrogations would provide information about the active resistance. Bernstorff and Kuenzer, who cultivated these contacts more than the other defendants, almost exclusively incriminated people who were already in custody or were already dead: Wilhelm Staehle , Otto Kiep, Nikolaus von Halem , Herbert Mumm von Schwarzenstein , Arthur Zarden and others their own co-defendants. On November 15, 1944, Bernstorff and the others named were charged before the People's Court of undermining military strength , favoring the enemy and high treason . Kuenzer also accused the Nazi judiciary of treason . When describing the facts, only 21 lines are attributed to Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff. While the other defendants cited specific accusations, the allegations against Bernstorff remained of a general nature. Roland Freisler set the main hearing for January 19, 1945, but postponed it to February 8. On that date, however, Freisler had been dead for five days.

Until his murder, Bernstorff spent almost two years in Nazi prisons and camps under inhumane conditions. On February 7, 1944, he and Helmuth James Graf von Moltke , the head of the Kreisau Circle, Otto Kiep and Hilger van Scherpenberg were admitted to the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp , where they were held in a special department for prominent political prisoners. In the room next to Bernstorff was Puppi Sarre from the Solf circle, and next to Sarre was Moltke. Isa Vermehrens was below Sarre's cell . Although the prison conditions initially seemed better than in Prinz-Albrecht-Straße, Bernstorff's most cruel period of suffering began: During interrogation, the National Socialists tortured him, which made him very physically weak and also susceptible to disease. He also fell into depression and kept himself mentally alive with the dream that when it was all over, to hold a big party in Stintenburg. Isa Vermehren reported after the war that Bernstorff had been treated particularly badly on the one hand because of his intelligence, on the other hand because of his "soft vulnerability" .

On October 19, 1944, the National Socialists Bernstorff and Lagi transferred Countess Ballestrem to the Lehrter Strasse cell prison in Berlin, where numerous conspirators of the unsuccessful assassination attempt on July 20 were held and had to wait for their trial before the People's Court. Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff was now fighting desperately for his life: he instructed his sister to make a donation from his assets to the local branch of the NSDAP, and he asked his business partner Joachim von Heinz to try to bribe Herbert Lange. His sisters should also try again to influence his sister-in-law Ingeborg Countess Bernstorff; she could now make up for earlier mistakes. But since December 1944, when the conditions of detention reached a terrible climax with the freezing cold, Bernstorff had been preparing for his imminent death: he wrote detailed instructions to his executor. In addition to the cold, which led to severe rheumatism and colds at Bernstorff , the prisoners suffered from the Allied bombing attacks, to which they were defenseless. When some prisoners were released from prison on April 21, 1945, friends and relatives hoped that Bernstorff could also be released soon.

On the night of April 22nd, a section of the SS came to the prison and took a total of sixteen prisoners from the cellar, where they were crammed together because of the danger posed by Allied bombers. The group was taken to a nearby rubble site at Lehrter Bahnhof and shot there without judgment. Richard Kuenzer and Wilhelm Staehle, Klaus Bonhoeffer , Rüdiger Schleicher , Friedrich Justus Perels and Hans John were among those murdered . The rest of the prisoners now took on shifts to watch the approaching Soviets, between 8 and 10 a.m. on April 23, Bernstorff took over this task. As the battle line drew closer and closer to the prison, the Gestapo closed the prisoner's book on April 23 and officially turned the prisoners over to justice. The prisoners were then returned to their cells, but after several hits by the Red Army, they returned to the cellar. On the night of April 23rd to April 24th, a special detachment from the Reich Main Security Office appeared and took Ernst Schneppenhorst , Karl Ludwig Freiherr von und zu Guttenberg and Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff with them. Schneppenhorst, Guttenberg and Bernstorff were never seen alive again. There is a suspicion that the execution order for these three prisoners came from Heinrich Himmler personally. It is very likely that they were shot by SS members south of the prison in the Lehrter Strasse area. Their bodies were never found. The other inmates of the Lehrter Strasse cell prison were released the next day, April 25, around 6 p.m.

memory

In the Federal Republic of Germany the life and work of Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff were recognized soon after the collapse of the Nazi regime. In 1952, Elly Countess Reventlow published a commemorative publication entitled “Albrecht Bernstorff in memory” , followed in 1962 by Kurt von Stutterheim with “The Majesty of Conscience. In Memoriam Albrecht Bernstorff ” , with a foreword by Theodor Heuss .

Stintenburg on the island in the Schaalsee, which had been under the administration of Nazi officials since Bernstorff's second arrest, was located directly on the border of the occupation zones , but had been part of the Soviet occupation zone from November 1945 onwards from the Barber-Lyashchenko Agreement . So the estate came to the GDR , where Bernstorff's performance as a liberal nobleman and a democrat in the opposition to Hitler did not agree with the anti-fascist state doctrine and therefore remained largely unknown. The Bernstorff family lived in West Germany, cut off from their former Stintenburg estate. After the fall of the Wall , Stintenburg came back into the family's possession. 1989 also opened the German Resistance Memorial in Bendlerblock its permanent collection, is thought in the Bernstorff. In 1992, the German Embassy held a memorial event for Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff in London. Ambassador Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen and representatives of the German Historical Institute and the University of Erlangen paid tribute to Bernstorff's services to German-British relations in their speeches. Their contributions were published as a memorial lecture on the occasion of Bernstorff's 50th anniversary of his death in 1995 . A plaque commemorates him in the German Embassy in London.

In 1996 the first Bernstorff biography appeared with Knut Hansen's dissertation "Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff: Diplomat and Banker between the Empire and National Socialism" . In 2000, the Foreign Office - now back in Berlin - erected a memorial plaque for members of the diplomatic service who lost their lives in the resistance against National Socialism. Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff is also honored in this way by the Foreign Office. On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the murder of Bernstorff, a memorial cross was erected for him in front of Gut Stintenburg. Marion Countess Dönhoff was also present at the wreath-laying ceremony there by the Foreign Office and the Prime Minister of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania . In 2004, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the assassination attempt on July 20 on the Stintenburg, the exhibition of the Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania Festival made possible by the Robert Bosch Foundation took place, which also commemorated Bernstorff. In this context, memorial concerts were held in the Lassahn parish church , formerly the family's patronage church . There is a plaque donated by Eric M. Warburg to Bernstorff.

Despite the numerous honors and the general recognition of his life's work, to this day neither a street, a square nor a school are named after Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff.

literature

- Werner Graf von Bernstorff: The Lords and Counts v. Bernstorff. A family story . Self-published, Celle 1982, pp. 339-351.

- Rainer Brunst: Three light trails in the history of Germany . Rhombos, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-937231-32-3 . Contains biographical portraits of Albrecht von Bernstorff, Otto von Bismarck and Gustav Stresemann.

- Eckart Conze: Of German nobility. The Counts of Bernstorff in the 20th century. German publishing company, Stuttgart / Munich 2000.

- Marion Countess Dönhoff : For the sake of honor. Memories of the Friends of July 20, Siedler, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88680-532-8 . (On pages 59 to 69 contains a chapter on Bernstorff, see also the section on the book in Lemma Dönhoff .)

- Knut Hansen: Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff. Diplomat and banker between the German Empire and National Socialism. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1996, ISBN 3-631-49148-4 .

- Eckardt Opitz: Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff. Fundamental opposition to Hitler and National Socialism . In: Ernst Willi Hansen u. a. (Ed.): Political Change, Organized Violence and National Security. Contributions to the recent history of Germany and France. Festschrift for Klaus-Jürgen Müller . Oldenbourg, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-486-56063-8 (= contributions to military history, 40), pp. 385-401.

- Elly Countess Reventlow (ed.): Albrecht Bernstorff in memory . Self-published, Düsseldorf 1952

- Kurt von Stutterheim: The Majesty of Conscience. In memoriam Albrecht Bernstorff . Foreword by Theodor Heuss . Christians, Hamburg 1962

- Kurt von Stutterheim: Bernstorff, Albrecht Graf von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1955, ISBN 3-428-00183-4 , p. 137 ( digitized version ).

- Antje Vollmer , Lars-Broder Keil Ed .: “National Socialism is directed against everything I stood up for” in: Stauffenberg's companions. The fate of the unknown conspirators. Hanser, Berlin 2013 ISBN 978-3-446-24156-5 ; TB dtv, Munich 2015, ISBN 3-423-34859-3 ; Softcover: Federal Agency for Civic Education , Series 1347, Bonn 2013

- Uwe Wieben: Albrecht von Bernstorff (1890–1945) , in: Personalities between the Elbe and Schaalsee. cw-Verlagsgruppe Schwerin, 2002 ISBN 3-933781-32-9 , pp. 94-105.

- Johannes Zechner: Ways to Resistance. July 20, 1944 in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania , in: Mecklenburgia Sacra. Yearbook for Mecklenburg Church History, Vol. 7, 2004, pp. 119–133.

Web links

- Literature by and about Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff in the catalog of the German National Library

- Resistance from traditional elites. Federal Agency for Civic Education : Information on Civic Education , Issue 243

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernstorff, p. 339ff.

- ↑ Hansen, p. 24.

- ↑ Hansen, p. 25.

- ^ Opitz, p. 387.

- ↑ a b Reventlow (Ed.), Contribution by Harald Mandt , p. 26