Emil Zatopek

|

Emil Zatopek |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Full name | Emil Ferdinand Zatopek | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| nation |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| birthday | September 19, 1922 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| place of birth | Kopřivnice | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| size | 182 cm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 72 kg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| job | Shoemaker | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| date of death | November 21, 2000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of death | Prague | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| discipline | Long distance running | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Best performance |

5000 m : 13: 57.0 min 10,000 m : 28: 54.2 min Marathon : 2: 23: 03.2 h |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| society | SK Bata Zlín Botostroj ATK Praha (Army Sports Club) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trainer | Jan Haluza | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National squad | since 1946 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| End of career | 1957 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medal table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Emil Zatopek Ferdinand (born September 19, 1922 in Kopřivnice , Okres Nový Jičín , Czechoslovakia ; † November 21, 2000 in Prague , Czech Republic ) was a Czechoslovak athlete who was primarily successful as a long-distance runner.

Zátopek's running career began in 1941. Under the guidance of coach Jan Haluza, he developed into an exceptional athlete within a few years, and in 1945 he became national champion for the first time. At the 1948 Olympic Games in London , he won gold and silver medals, respectively, in the 10,000 and 5000 meters, and at the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki he won three gold medals. He was also three times European champion. Between 1949 and 1955, Zátopek set numerous world records. In 1957 he retired from high-performance sport after setting 18 world, 3 Olympic and 51 national records.

Zátopek was a signatory to the 2000 Words Manifesto during the Prague Spring 1968 , after which he was dismissed from office and publicly discredited. From 1974 he, who was considered a folk hero in Czechoslovakia, was first gradually reintegrated into society and rehabilitated after the Velvet Revolution in 1990.

Zátopek's unusual training methods, especially the frequent repetition of interval runs, are considered revolutionary. His unorthodox running style has caused controversial discussions to this day about whether it makes sense to run economically and cleanly .

Early years

Parental home and childhood

Emil Zátopek was born on September 19, 1922 in Kopřivnice, northern Moravia, as the son of František († 1963) and Anežka († 1962) Zátopek. He had six older siblings and one younger brother. His father worked as a carpenter in the body department of the Tatra works . As a sideline, he made furniture. The mother was a laborer in a brick factory, later a housewife and was considered loving, while the father occasionally chastised his children.

The family lived in a semi-detached house on the northern outskirts of Kopřivnice and cultivated a garden with animals for self-sufficiency. Zátopek, who was left-handed by the way, attended the local elementary school and was considered hardworking. In later years he spoke numerous foreign languages, including French, English, Russian, German, Hungarian, Spanish, Finnish, Indonesian and Serbo-Croatian. He spent his childhood carefree. He loved frolicking and liked to bathe in the Lubina River . He avoided sporting activities as much as possible. Zátopek, who was perceived as weak and uncoordinated by his surroundings, played football like almost all of his friends, but rather listlessly and mostly barefoot to protect his only pair of shoes.

education

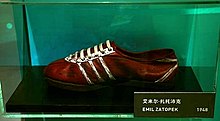

According to his parents' wishes, Zátopek, who had left school in 1937, should become a teacher, which failed because of the university fees that they could not afford. Instead, he trained as a shoemaker at the Baťa works in Zlín and lived in the company's own boarding school. After two years in the assembly line production, Zátopek was admitted to the higher trade school thanks to his high level of comprehension and transferred to the chemical research institute of the plant. After the annexation of the Sudetenland by National Socialist Germany as part of the Munich Agreement in October 1938 and the smashing of the rest of the Czech Republic in March of the following year, the production capacities of the Baťa footwear were made available to the Wehrmacht , and the German rulers punished resistance with sometimes draconian penalties . Zátopek was aware of this and submitted to the regime.

Athletic career

Beginnings

In the spring of 1941, the management of the Baťa works organized a local company run for all men of military age in the fourth year of study. Zátopek, who until then had not thought much of the sport and tried in vain to evade it through a feigned injury, contested his first street race. He finished the 1400-meter run, surprisingly for him, in second, for which he received a fountain pen as a prize. A few weeks later, in the meantime Zátopek had been accepted into the works team, he again achieved second place in a 1,500 meter run in Brno. That year, Jan Haluza , one of the country's greatest running talents, became aware of Zátopek at an athletics event. Haluza's offer to train with him under professional guidance - he became his only coach - Zátopek accepted. Haluza began to develop Zátopek into a top athlete. He radically changed Zátopek's diet and lifestyle, instructed him in interval training and spurred him on to better and better performance through even harder training. Under Haluza's guidance, Zátopek led the 4-by-1500-meter relay at the national championships in 1942 to a new record, and in the autumn of 1943 he won his first 1500-meter victory in Prague on the occasion of the Bohemia versus Moravia competition. In that year he had graduated from the Baťa-Werke technical college and was now employed in their chemical department. In 1944, Zátopek broke three records within 16 days - in the 3000 meter run (8: 38.8 min), over 5000 meters (14:55 min) and on October 1 over 2000 meters (5: 33.4 min) . Since then, Zátopek has preferred to train alone, especially since Haluza believed he had taught him everything about running.

Ascent

1945: New national records

In the last months of the war, regular training was out of the question. In November 1944, the Baťa works had been bombed by Allied aircraft and were mostly in ruins. The German occupiers intensified their reprisals against the civilian population and arbitrarily arrested residents who they accused of sabotage or collaboration with the enemy. During this phase, Zátopek was driven only by the thought of surviving the war. After the liberation of Zlín on May 2, 1945 by the Red Army , Zátopek saw no more professional prospects for himself in the Baťa works. So it was convenient for him that he was called up for military service in the same month with the Czechoslovak Army , which was being established on May 20, 1945. His basic training took place in the 27th Infantry Regiment in Uherské Hradiště . Here, with the support of his superiors, he found enough time to train. On June 1st of that year Zátopek broke the national record over 3000 meters (8: 33.4 min) and a month later on the occasion of the Czechoslovak Championships that over the 5000 meters (14: 50.8 min). In the summer he decided to become a professional soldier. His two-year officer training took place in Hranice , later with the 11th tank brigade in Milovice and at the military academy in Prague.

1946: European Championships in Oslo

In June Zátopek improved the national record over 5000 meters to 14:36 minutes. This opened up a real chance for a medal at the European Athletics Championships in Norway in August . After further tightening of training and a few preparatory runs, Zátopek traveled with four other representatives of the Czechoslovak national team to Oslo, where the 5000-meter run took place on 23 August in the Bislett Stadium there. Here he met for the first time on international running greats such as Slijkhuis , Nyberg , Reiff , Heino and Pujazon as well as the favorite Wooderson . A total of 18 runners took part in the race, 14 of whom reached the finish. To his surprise, Wooderson, whom Zátopek wanted to use as a guide, dropped back after the start. Confused by this, he placed fifth, then caught up with the leading group and was third at times. The constant changes in position and pace caused general confusion in the runners' field, so that the inexperienced Zátopek could not gain any control over the race. Wooderson finally picked up the pace on the final lap, passed the lead and won ahead of Slijkhuis. At this point, Zátopek was in third place, but was overtaken by Nyberg and Heino in the last few meters, making him fifth with a new national record (14: 25.8 min).

He then competed in other races: In Berlin he was the only representative of Czechoslovakia to be ridiculed by the public at the Allied Sports Championships, but celebrated after a superior victory in the 5000 meter run. In London he won the 6-mile cross-country run as part of the Britannia Shield - a multi-sporting event that was intended to highlight the military ties of the former allies.

1947: Further national records

|

Split times (Evžen Rošický Memorial Run 1947) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rd. | Split | total time | distance |

| 1 | 30.2 s | 30.2 s | 200 m |

| 2 | 64.5 s | 1: 34.7 min | 600 m |

| 3 | 67.5 s | 2: 42.2 min | 1000 m |

| 4th | 64.5 s | 3: 46.7 min | 1400 m |

| 5 | 67.5 s | 4: 54.2 min | 1800 m |

| 6th | 67.0 s | 6: 01.2 min | 2200 m |

| 7th | 69.0 s | 7: 10.2 min | 2600 m |

| 8th | 68.0 s | 8: 18.2 min | 3000 m |

| 9 | 70.0 s | 9: 28.2 min | 3400 m |

| 10 | 69.0 s | 10: 37.2 min | 3800 m |

| 11 | 70.3 s | 11: 47.5 min | 4200 m |

| 12 | 68.7 s | 12: 56.2 min | 4600 m |

| 13 | 72.0 s | 14:08.2 min | 5000 m |

After a superior victory over the 10,000-meter distance at the Allied Sports Championships held in Hanover in spring 1947 , Zátopek ran a national record (8: 13.6 min) in the city competition between Zlín and Bratislava in the 3000-meter run. In the subsequent Evžen Rošický memorial run in Prague's Strahov Stadium , he broke the national record over the 5000 meters with 14: 08.2 min. The competition of the year, however, was the 5000 meter race in Helsinki, Finland, on June 30th, where Zátopek and Heino fought a thrilling duel that he could only win in the final sprint. In the following international matches against the Netherlands (July 12), Italy (July 19) and France (August 16), he won over the same distance, as well as on August 2 at the national championships. On August 17, Zátopek was appointed lieutenant after having passed officer training , and as such a tank commander. The following day he ran in Brno with 8: 08.8 minutes over the 3000 meter distance and on August 21 in the 2000 meter run in Bratislava (5: 20.5 minutes) again national records. At the subsequent Academic Summer Games in Paris, victories in the 1,500 and 5,000 meter races followed. He contested the next races in France, Belgium and Poland, all of which he won with the exception of the race in Brussels. Zátopek finished the season in December with the "Journal d'Algier" in Algeria , where he won another victory on December 25, 1947 in the 3000 meter run. In total, Zátopek competed in twelve 5000 meter races that year, all of which he had won. He already had his next sporting goal in mind - participation in the 1948 Olympic Games in London.

Highlights

1948: Olympic Games in London

|

Split times (10,000 meter run) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rd. | Split | total time | distance |

| 1 | 67.0 s | 1: 07.0 min | 400 m |

| 2 | 71.6 s | 2: 18.6 min | 800 m |

| 3 | 71.2 s | 3: 29.8 min | 1200 m |

| 4th | 70.0 s | 4: 39.8 min | 1600 m |

| 5 | 72.8 s | 5: 52.6 min | 2000 m |

| 6th | 70.6 s | 7: 03.2 min | 2400 m |

| 7th | 71.8 s | 8: 15.0 min | 2800 m |

| 8th | 73.4 s | 9: 28.4 min | 3200 m |

| 9 | 73.6 s | 10: 42.0 min | 3600 m |

| 10 | 72.0 s | 11: 54.0 min | 4000 m |

| 11 | 72.6 s | 13: 06.6 min | 4400 m |

| 12 | 74.2 s | 14: 20.8 min | 4800 m |

| 13 | 74.4 s | 15: 35.2 min | 5200 m |

| 14th | 73.8 s | 16: 49.0 min | 5600 m |

| 15th | 72.0 s | 18: 01.0 min | 6000 m |

| 16 | 70.8 s | 19: 11.8 min | 6400 m |

| 17th | 71.0 s | 20: 22.8 min | 6800 m |

| 18th | 71.8 s | 21: 34.6 min | 7200 m |

| 19th | 72.4 s | 22: 47.0 min | 7600 m |

| 20th | 73.0 s | 24: 00.0 min | 8000 m |

| 21st | 73.4 s | 25: 13.4 min | 8400 m |

| 22nd | 71.6 s | 26: 25.0 min | 8800 m |

| 23 | 74.8 s | 27: 39.8 min | 9200 m |

| 24 | 73.2 s | 28: 53.0 min | 9600 m |

| 25th | 66.6 s | 29: 59.6 min | 10,000 m |

|

Split times (5000 meter run) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rd. | Split | total time | distance |

| 1 | - | 33.0 s | 200 m |

| 2 | 66.2 s | 1: 39.2 min | 600 m |

| 3 | 68.8 s | 2: 48.0 min | 1000 m |

| 4th | 68.4 s | 3: 56.4 min | 1400 m |

| 5 | 67.6 s | 5: 04.0 min | 1800 m |

| 6th | 69.0 s | 6: 13.0 min | 2200 m |

| 7th | 70.0 s | 7: 23.0 min | 2600 m |

| 8th | 71.0 s | 8: 34.0 min | 3000 m |

| 9 | 70.2 s | 9: 44.2 min | 3400 m |

| 10 | 67.8 s | 10: 52.0 min | 3800 m |

| 11 | 68.0 s | 12:00, 0 min | 4200 m |

| 12 | 68.0 s | 13: 08.0 min | 4600 m |

| 13 | 69.6 s | 14: 17.6 min | 5000 m |

In spring, Zátopek's training was geared towards his first participation in the Olympics , regardless of the Communist takeover by the KPČ in the course of the February revolution . For this he increased his training in an extraordinary way. He won all of the compulsory build-up races from May to June. It is worth mentioning his new Czechoslovak record over the 10,000 meters on May 29 in Budapest (30: 28.4 min), which he undercut a good month later on June 17 in Prague (29: 37.0 min). The last yardstick before the games was the three-country battle between Czechoslovakia and the Netherlands and Hungary in Prague on June 22, where Zátopek clearly won the 5000-meter race in 14: 10.0 minutes.

At this time Zátopek was already in a relationship with the javelin thrower Dana Ingrová (1922-2020), who was born on the same day as him and who gave him the nickname Topek . The couple married on October 24 of the same year in Uherské Hradiště ; the marriage remained childless.

A few days before the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games , the Czechoslovak national team arrived in London. Zátopek was housed in a makeshift barrack of the Royal Air Force in the West Drayton district. Despite these adverse conditions, he won gold in the 10,000 meter run - the first ever Olympic triumph for the ČSSR. In the run-up to the race, Zátopek had calculated a lap time of 71 seconds, which resulted in a possible victory time of 30 minutes. In order to stay in the finish window during the run, he agreed with his trainer that he would be able to detect it visually from the stands. White gym shorts held up to Zátopek signaled that the pace was faster than required for the lap time, and a red jersey that the times were above the target time. The items of clothing should be swirled when the times were better or worse by more than 10 seconds. The race started at a fast pace, with all athletes suffering from the summer heat. Zátopek initially held back and lined up in fifteenth place, as the white gym shorts held up showed him that the top was going too fast. After the sixth lap he was even seventeen. In the ninth lap, the red jersey showed him that the top had slowed down their pace. At that moment, Zátopek started an intermediate sprint, initially moved up to fourth place and finally took the lead. After his Finnish rival Heino gave up on lap 16, who left the race completely exhausted, the way was clear for the “Czech locomotive”, as the press later dubbed it. Zátopek won in a time of 29: 59.6 minutes, which was an Olympic record, with almost 48 seconds ahead of second-placed Alain Mimoun from France, who later became known as the “shadow of Zátopek” and with whom he had a close friendship throughout his life Association. On the last lap he had the time to give the lapped French Ben Saïd Abdallah encouraging words.

In the 5000-meter run on a rain-soaked cinder track, however, Zátopek fought a duel with Gaston Reiff with extreme commitment . The lead had changed several times in the course of the race until Reiff hurried out of the field on the fourth lap. Zátopek struggled to keep up with the set pace and had to let go because he had previously made the mistake of accepting the challenge of an opponent in advance and completely exhausting himself in the process. In the last lap, he mobilized his remaining strength and, to the frenetic applause of the spectators, pushed himself steadily towards Reiff. In what is now a legendary final sprint, the two opponents were separated by only two tenths of a second with the happier outcome for Reiff, who won with 14: 17.6 minutes.

Zátopek rose to national hero through his unexpected Olympic successes; President Klement Gottwald honored the athlete with a reception at Prague Castle . The new "sport idol" then contested a dozen endurance races between 3,000 and 10,000 meters in Brussels, Amsterdam, Ostend, Prague, Brno, Paris, Bucharest, Bologna and Milan, which he won with the exception of two races. At the end of the year, Zátopek was unable to act and was shocked by the arrest of his long-time coach and friend Haluza, who had been arrested as a member of the opposition on the basis of the February revolution and sentenced to long term labor after a show trial. The existing friendship between the two men suffered considerably as a result, but did not break.

1949: First world record runs

| World record run (June 11, 1949) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | distance | comment |

| 2: 54.5 min | 2: 54.5 min | 14: 39.5 min | 1000 m | |

| 2: 54.5 min | 5: 49.0 min | 2000 m | ||

| 2: 54.0 min | 8: 43.0 min | 3000 m | ||

| 2: 57.7 min | 11: 40.7 min | 4000 m | ||

| 2: 58.8 min | 14: 39.5 min | 5000 m | ||

| 2: 59.5 min | 17: 39.0 min | 14: 48.7 min | 6000 m | |

| 2: 58.0 min | 20: 37.0 min | 7000 m | ||

| 3: 00.0 min | 23: 37.0 min | 8000 m | ||

| 2: 59.0 min | 26: 36.0 min | 9000 m | ||

| 2: 52.2 min | 29: 28.2 min | 10,000 m | WR | |

| World record run (October 22, 1949) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | distance | comment |

| 2: 55.0 min | 2: 55.0 min | 14: 38.0 min | 1000 m | |

| 2: 55.9 min | 5: 50.9 min | 2000 m | ||

| 2: 54.1 min | 8: 45.0 min | 3000 m | ||

| 2: 57.0 min | 11: 42.0 min | 4000 m | ||

| 2: 56.0 min | 14: 38.0 min | 5000 m | ||

| 2: 58.0 min | 17: 36.0 min | 14: 43.2 min | 6000 m | |

| 2: 57.5 min | 20: 33.5 min | 7000 m | ||

| 2: 59.5 min | 23: 33.0 min | 8000 m | ||

| 2: 57.5 min | 26: 30.5 min | 9000 m | ||

| 2: 50.7 min | 29: 21.2 min | 10,000 m | WR | |

The Zátopeks moved to Prague in 1949, where they lived in a two-room apartment at 8 Půjčovny Street until they moved into their own home. After a number of different build-up races, Zátopek ran 22 races from May to September. His first world record run over the 10,000 meters on June 11 at the Army Championships in Ostrava, where he improved Viljo Heino's previous record by seven seconds to 29: 28.2 minutes, caused an international stir. For this first world record in Czechoslovakia, Zátopek was promoted to captain. A week later he - at this point already suffering from a severe leg muscle injury - ran to victory in the same place and over the same distance on the occasion of the international match against Romania. After that, he was sidelined for several weeks because of this injury. After his recovery, Zátopek flew to Finland for an international competition in the early summer of 1949, where he competed in four races (one 10,000, two 5000 and one 3000 meters) within six days and won them all. Further international battles in the Soviet Union, Hungary and Romania followed. In July, Zátopek won the 5,000 and 10,000 meter distances in Moscow. He succeeded in repeating the whole thing in Budapest at the end of August and ran another double in Bucharest in September.

In the meantime, Heino had beaten Zátopek's world record over 10,000 meters by one second. In order to bring the lost record back to the ČSSR, the Czechoslovak Sports Federation attempted another world record on October 22nd in Ostrava after the first attempt on September 17th had failed. Zátopek was under additional pressure to succeed when, shortly before the start, he saw a newspaper boy who was already carrying the printed special about his success under his arm. Undeterred, he ran another world record in front of 20,000 spectators with 29: 21.2 minutes.

1950: European Championships in Brussels

| World record run (August 4, 1950) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | distance | comment |

| 2: 58.0 min | 2: 58.0 min | 14: 37.0 min | 1000 m | |

| 2: 53.8 min | 5: 51.8 min | 2000 m | ||

| 2: 54.2 min | 8: 46.0 min | 3000 m | ||

| 2: 55.5 min | 11: 41.5 min | 4000 m | ||

| 2: 55.5 min | 14: 37.0 min | 5000 m | ||

| 2: 54.0 min | 17: 31.0 min | 14: 25.6 min | 6000 m | |

| 2: 53.0 min | 20: 24.0 min | 7000 m | ||

| 2: 56.0 min | 23: 20.0 min | 8000 m | ||

| 2: 55.0 min | 26: 15.0 min | 9000 m | ||

| 2: 47.6 min | 29: 02.6 min | 10,000 m | WR | |

Following an invitation from the Soviet Union, the Zátopeks spent the preparation for the season together in the training camp in Sochi . After this development phase, Zátopek made his debut on the occasion of a youth festival for the first time in the area of the young GDR , where he won the 5000 meter distance in East Berlin. This was followed by further expansion runs in Prague, Brno, Bratislava and Brussels in June and July. The army championships in Ostrava, which were scheduled for the beginning of August, had to be canceled by Zátopek due to a start obligation in Finland. There he ran 5000 meters in Helsinki on August 3 with a time of 14: 06.2 minutes and the day after that he ran a world record of 29: 02.6 minutes in Turku over the 10,000 meter distance.

As a result, Zátopek was treated as a title contender from the start at the European Athletics Championships in Brussels at the end of August and actually ran outside of any competition. He won both over 10,000 meters and over 5000 meters with new European championship records. In the 5000 meter race, Reiff took the lead immediately after the start. Zátopek held back the first two laps and was second to last at times. On lap three he took the lead, which he had to give back to Reiff two laps later, who in turn accelerated the pace enormously. Its lead was quickly 10 meters and more. But Zátopek could not be shaken off. He hung himself in Reiff's slipstream and put all remaining strength into the final sprint with the start of the last lap. Zátopek passed Reiff, who could no longer counter his attack, and won with about 130 meters ahead of Mimoun, who had caught the completely exhausted Reiff in the last few meters. Back home, Zátopek won over the same distances in the international match against Finland and the Soviet Union as well as in other competitions in Erfurt and Dresden . Shortly before the European Championships, Zátopek suffered severe food poisoning, which did not prevent him from continuing his training in the hospital garden and from discharging himself early in order to just catch the plane to Brussels. From that year on, he worked in the Ministry of Defense in Prague, where he rose to the rank of colonel until 1968. Among other things, he developed concepts for the physical training of soldiers there.

1951: New world record runs

| World record run (September 15, 1951) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | 10 km split | distance | comment |

| 3: 04.7 min | 3: 04.7 min | 15: 35.6 min | 31: 05.0 min | 1000 m | |

| 3: 08.3 min | 6: 13.0 min | 2000 m | |||

| 3: 08.2 min | 9: 21.2 min | 3000 m | |||

| 3: 15.8 min | 12: 37.0 min | 4000 m | |||

| 2: 58.6 min | 15: 35.6 min | 5000 m | |||

| 3: 07.4 min | 18: 43.0 min | 15: 29.4 min | 6000 m | ||

| 3: 05.0 min | 21: 48.0 min | 7000 m | |||

| 3: 04.8 min | 24: 52.8 min | 8000 m | |||

| 3: 06.8 min | 27: 59.6 min | 9000 m | |||

| 3: 05.4 min | 31: 05.0 min | 10,000 m | |||

| 3: 02.8 min | 34: 07.8 min | 15: 09.0 min | 30: 10.8 min | 11,000 m | |

| 3: 01.0 min | 37: 08.8 min | 12,000 m | |||

| 3: 00.6 min | 40: 09.4 min | 13,000 m | |||

| 3: 03.4 min | 43: 12.8 min | 14,000 m | |||

| 3: 01.2 min | 46: 14.0 min | 15,000 m | |||

| 3: 03.0 min | 49: 17.0 min | 15:01.8 min | 16,000 m | ||

| 3: 01.2 min | 52: 18.2 min | 17,000 m | |||

| 3: 01.8 min | 55: 20.0 min | 18,000 m | |||

| 3: 03.0 min | 58: 23.0 min | 19,000 m | |||

| - | 1 h | 19,558 m | WR | ||

| 2: 52.8 min | 1: 01: 15.8 h | 20,000 m | WR | ||

| World record run (September 29, 1951) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | 10 km split | distance | comment |

| 2: 58.0 min | 2: 58.0 min | 14: 57.4 min | 29: 53.4 min | 1000 m | |

| 2: 57.0 min | 5: 55.0 min | 2000 m | |||

| 3: 01.2 min | 8: 56.2 min | 3000 m | |||

| 3: 00.2 min | 11: 56.4 min | 4000 m | |||

| 3: 01.0 min | 14: 57.4 min | 5000 m | |||

| 3: 00.0 min | 17: 57.4 min | 14: 56.0 min | 6000 m | ||

| 2: 58.6 min | 20: 56.0 min | 7000 m | |||

| 2: 59.0 min | 23: 55.0 min | 8000 m | |||

| 2: 58.2 min | 26: 53.2 min | 9000 m | |||

| 3: 00.2 min | 29: 53.4 min | 10,000 m | |||

| 2: 58.6 min | 32: 52.0 min | 15:01.2 min | 29: 58.4 min | 11,000 m | |

| 2: 59.0 min | 35: 51.0 min | 12,000 m | |||

| 3: 01.0 min | 38: 52.0 min | 13,000 m | |||

| 3: 00.0 min | 41: 52.0 min | 14,000 m | |||

| 3: 02.6 min | 44: 54.6 min | 15,000 m | |||

| 3: 01.4 min | 47: 56.0 min | 14: 57.2 min | 16,000 m | ||

| - | 48: 12.0 min | 10 mi | WR | ||

| 3: 00.2 min | 50: 56.2 min | 17,000 m | |||

| 3: 01.8 min | 53: 58.0 min | 18,000 m | |||

| 3: 02.0 min | 57: 00.0 min | 19,000 m | |||

| 2: 51.8 min | 59: 51.8 min | 20,000 m | WR | ||

| - | 1 hour | - | - | 20,052 m | WR |

In the winter of 1951, Zátopek tore a tendon while skiing, which prevented any training until April. After the subsequent construction phase, it took until June that he was able to run the 5000 meters in under 15 minutes again. In the following months, a documentary about the life of Zátopeks was shot under the title "One from the relay", the recording work had such an unfavorable effect on the training schedule that he lost a 3000 meter race against Václav Čevona . As a result, work on the film had to be interrupted for the time being. After resuming regular training, Zátopek came by August, just in time for the start of the III. World Youth Festival in East Berlin , back in shape. There he won the 5000 meters with a personal best for the year. Further first places in the international match against Hungary in Budapest followed.

On September 15, 1951, Zátopek ran in the context of the army championships held in Prague in a 20,000-meter run with a world record of 1: 01: 16.0 h, while at the same time he improved the world annual best in the hour to 19,558 meters. The results confirmed that he was the first person to be able to run the 20 kilometers under an hour. For example, another world record attempt was set for September 29 in the Houšťka stadium in Stará Boleslav , in which, besides himself, 16 other runners took part. Under ideal external conditions, Zátopek set three world records in one run: he improved the distance covered in the hour run to 20,052 m, the time over 20,000 meters was noted as 59: 51.8 min and the world best in the 10-mile race to 48: Pressed for 12.0 min.

1952: Olympic Games in Helsinki

| World record run (October 26, 1952) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | 10 km split | distance | comment |

| 3: 07.0 min | 3: 07.0 min | 15: 48.0 min | 31: 43.6 min | 1000 m | |

| 3: 12.0 min | 6: 19.0 min | 2000 m | |||

| 3: 08.4 min | 9: 27.4 min | 3000 m | |||

| 3: 08.0 min | 12: 35.4 min | 4000 m | |||

| 3: 12.6 min | 15: 48.0 min | 5000 m | |||

| 3: 00.0 min | 18: 48.0 min | 15: 55.6 min | 6000 m | ||

| 3: 20.4 min | 22: 08.4 min | 7000 m | |||

| 3: 12.6 min | 25: 21.0 min | 8000 m | |||

| 3: 17.0 min | 28: 38.0 min | 9000 m | |||

| 3: 05.6 min | 31: 43.6 min | 10,000 m | |||

| 3: 10.4 min | 34: 54.0 min | 15: 51.4 min | 31: 31.6 min | 11,000 m | |

| 3: 12.0 min | 38: 06.0 min | 12,000 m | |||

| 3: 11.8 min | 41: 17.8 min | 13,000 m | |||

| 3: 08.6 min | 44: 26.4 min | 14,000 m | |||

| 3: 08.6 min | 47: 35.0 min | 15,000 m | |||

| 3: 07.2 min | 50: 42.2 min | 15: 40.2 min | 16,000 m | ||

| 3: 04.6 min | 53: 46.8 min | 17,000 m | |||

| 3: 08.0 min | 56: 54.8 min | 18,000 m | |||

| 3: 10.6 min | 1: 00: 05.4 h | 19,000 m | |||

| 3: 09.8 min | 1: 03: 15.2 h | 20,000 m | |||

| 3: 09.0 min | 1: 06: 24.2 hours | 15: 56.6 min | 32: 08.6 min | 21,000 m | |

| 3: 11.2 min | 1: 09: 35.4 h | 22,000 m | |||

| 3: 11.2 min | 1:12: 46.6 h | 23,000 m | |||

| 3: 12.6 min | 1: 15: 59.2 h | 24,000 m | |||

| - | 1: 16: 26.4 h | 15 mi | WR | ||

| 3: 12.6 min | 1: 19: 11.8 h | 25,000 m | WR | ||

| 3: 11.8 min | 1: 22: 23.6 h | 16: 12.0 min | 26,000 m | ||

| 3: 14.2 min | 1: 25: 37.8 h | 27,000 m | |||

| 3: 15.4 min | 1: 28: 53.2 h | 28,000 m | |||

| 3: 18.0 min | 1: 32: 11.2 h | 29,000 m | |||

| 3: 12.6 min | 1: 35: 23.8 h | 30,000 m | WR | ||

|

Split times (5000 meter run) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | distance |

| 2: 47.0 min | 2: 47.0 min | 1000 m |

| 2: 50.4 min | 5: 37.4 min | 2000 m |

| 2: 53.0 min | 8: 30.4 min | 3000 m |

| 2: 54.4 min | 11: 24.8 min | 4000 m |

| 2: 41.8 min | 14: 06.6 min | 5000 m |

|

Split times (10,000 meter run) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | distance |

| 2: 52.0 min | 2: 52.0 min | 1000 m |

| 2: 59.0 min | 5: 51.0 min | 2000 m |

| 2: 57.0 min | 8: 48.0 min | 3000 m |

| 2: 57.6 min | 11: 45.6 min | 4000 m |

| 2: 57.8 min | 14: 43.4 min | 5000 m |

| 2: 55.8 min | 17: 39.2 min | 6000 m |

| 2: 54.8 min | 20: 34.0 min | 7000 m |

| 5: 54.0 min | 26: 28.0 min | 9000 m |

| 2: 49.0 min | 29: 17.0 min | 10,000 m |

|

Split times (marathon run) |

||

|---|---|---|

| distance | sequence | time |

| 5000 m | 1. Peters 2. Cox 3. Jansson 4. Zátopek | 15:43 min 16:02 min 16:02 min 16:02 min |

| 10,000 m | 1. Peters 2. Jansson 3. Zátopek | 31:55 min 32:11 min 32:12 min |

| 15,000 m | 1. Peters 2. Jansson 3. Zátopek | 47:58 min 47:58 min 48:00 min |

| 20,000 m |

1. Zátopek 2. Jansson 3. Peters |

1:04:27 h 1:04:27 h 1:04:37 h |

| 25,000 m |

1. Zátopek 2. Jansson 3. Peters |

1:21:30 h 1:21:35 h 1:21:58 h |

| 30,000 m |

1. Zátopek 2. Jansson 3. Peters |

1:38:42 h 1:39:08 h 1:39:53 h |

| 35,000 m |

1. Zátopek 2. Jansson 3. Gorno |

1:56:50 h 1:57:55 h 1:58:46 h |

| 40,000 m |

1. Zátopek 2. Gorno 3. Jansson |

2:15:10 h 2:17:25 h 2:17:36 h |

| 42,195 m |

1. Zátopek 2. Gorno 3. Jansson |

2: 23: 03.2 h 2: 25: 35.0 h 2: 26: 07.0 h |

In the winter of 1951/1952, Zátopek devoted himself exclusively to preparing for the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki , where he was assigned the role of favorite in the 5000 and 10,000 meters. He was affected by a severe cold, the consequences of which he overcame six weeks before the start of the games. Zátopek met the training deficit with numerous build-up races in the GDR, Hungary and the Soviet Union, where he finished third in the 5000-meter distance and first in the 10,000-meter run in Kiev. However, he found the times achieved so bad that he seriously considered canceling his participation in the games. The victory times in the 5000- (14: 17.6 min) and 10,000-meter run (30: 28.4 min) at the national championships convinced him to compete.

In the run-up to the big event, Zátopek first came into conflict with the Czechoslovak government when he learned that his compatriot Stanislav Jungwirth was to be excluded from the games because his father had been arrested for distributing leaflets critical of the regime. Thereupon the extremely popular Zátopek threatened to not start and forced Jungwirth to participate because of expected medal wins and fear of loss of prestige. The arrest of a large part of the Czechoslovak national ice hockey team ( world champion 1947 ) in 1950 - two years earlier - had shown that such daring steps could lead to disadvantages : the "state-endangering agitation" had been sentenced to long imprisonment and labor terms. Zátopek did not remain unmolested. After the games, General Václav Kratochvíl (1903–1988) invited him to a hearing at the Ministry of the Interior, who had a letter accusing Zátopek of insubordination . Ultimately, the allegation was dropped because of Zátopek's sporting successes.

After this incident, Zátopek and Jungwirth did not arrive at the Olympic village in Otaniemi until July 11th and immediately intensified his training. Overall, Zátopek won gold three times: he won the 10,000 meters as the favorite with 29: 17.0 minutes, clearly ahead of his opponents Mimoun and Anufrijew . His victories over 5000 meters and in the marathon are considered unparalleled.

Three 5000-meter prelims were held, from which the first five qualified directly for the finals. Zátopek was drawn into the third run and easily reached the final with a time of 14: 26.0 min. Herbert Schade, who was considered the favorite, took the lead right after the start . From the middle of the race onwards, Zátopek temporarily took the lead in order to be able to reduce the previously high speed. With two laps to go, the top field was still close together. At the end of the last corner, Briton Chris Chataway took the lead, closely followed by Schade, Mimoun, Zátopek and Pirie. Now Zátopek increased the pace, first knocked Mimoun down on lane two and shortly after overtook Schade and Chataway on lane three, who stumbled over the cement edging of the track and fell while trying to keep up the pace. At the exit of the last bend, about 100 meters from the finish, Zátopek made the decisive final spurt and won ahead of Mimoun. It was only shortly before the closing date that he decided to take part in the marathon, which he had never run in a competition before. Here too, as in the other two competitions, he won with an Olympic record (2: 23: 03.2 h). His entrance to the stadium turned out to be a unique spectacle in the history of sports when Zátopek completed the last lap solo and crossed the finish line to the thunderous applause of almost 70,000 spectators and cheered on by euphoric "Zá-to-pek" shouts. The Times then hailed him as the "greatest long-distance runner of all time" and the later IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch later recalled that at that moment he understood what the Olympic spirit meant.

Zátopek's return home - his wife had also won a gold medal by throwing a javelin and almost at the same time - was triumphant. Numerous receptions were held in his honor. He received honors and eulogies from high-ranking military and politicians; the national and international press celebrated him. The now 30-year-old Zátopek was promoted to major in recognition of his sporting achievements and received the Order of the Republic on September 20 . Zátopek's most successful year of his sports career ended on October 26th in the Houšťka stadium in Stará Boleslav, where he broke three world records at once during a 30,000-meter run, in addition to the 30-kilometer (1:35:23, 8 h) undercut the existing best times in the 15-mile (1.16: 26.4 h) and 25,000-meter run (1.19: 11.8 h). On December 12th, together with Otto Peltzer, he was a guest speaker at the Vienna People's Congress for Peace, where both athletes spoke to a large audience about their respective Olympic experiences.

1953: Further world record runs

| World record run (November 1, 1953) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | distance | comment |

| 2: 52.8 min | 2: 52.8 min | 14: 34.8 min | 1000 m | |

| 2: 55.8 min | 5: 48.6 min | 2000 m | ||

| 2: 55.2 min | 8: 43.8 min | 3000 m | ||

| 2: 55.8 min | 11: 39.6 min | 4000 m | ||

| 2: 55.2 min | 14: 34.8 min | 5000 m | ||

| 2: 53.8 min | 17: 28.6 min | 14: 26.8 min | 6000 m | |

| 2: 55.4 min | 20: 24.0 min | 7000 m | ||

| 2: 55.6 min | 23: 19.6 min | 8000 m | ||

| 2: 57.2 min | 26: 16.8 min | 9000 m | ||

| - | 28: 08.4 min | 6 mi | WR | |

| 2: 44.8 min | 29: 01.6 min | 10,000 m | WR | |

At the beginning of the year, dental, tonsil and sciatica complaints led to high training deficits. Zátopek did not contest his first 5000 meter run until May, the time (14: 33.0 min) of which failed to achieve the expected top form. In the mid-July international match against Hungary in Prague and the subsequent national championships, Zátopek won again with mediocre times in the 5000 and 10,000 meter races there. An improvement in his form only became apparent at the World Youth Festival in Bucharest at the beginning of August, where he won the 5000 meters on the opening day in very hot temperatures (14: 08.0 min). In the 10,000-meter run (29: 25.8 min) that took place two days later, he defeated the top-class Soviet delegation, which had started at high speed as usual, with a tactical championship run.

After intensified training, Zátopek ran a world record of 29: 01.6 minutes over the 10,000 meters in the Houšťka stadium on November 1st and at the same time set the world's best performance over the 6-mile distance to 28: 04.4 minutes. He was given a special honor at the end of the year, when Zátopek was invited to the Brazilian International New Year's Run in São Paulo . Even at the airport, the “world star” experienced an onslaught of countless journalists. His hotel was then besieged by numerous fans. A relaxed training lap with his fellow runner Adolf Gruber had to be secured by a motorized police escort. 2140 runners from 16 nations took part in the actual race. Zátopek won confidently on the 7300 meter long road course and set a new course record with 20:30 minutes.

1954: European Championships in Bern

|

Split times (10,000 meter run) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rd. | Split | total time | distance |

| 1 | 68.8 s | 1: 08.8 min | 400 m |

| 2 | 70.8 s | 2: 19.6 min | 800 m |

| 3 | 69.1 s | 3: 28.7 min | 1200 m |

| 4th | 68.1 s | 4: 36.8 min | 1600 m |

| 5 | 69.0 s | 5: 45.8 min | 2000 m |

| 6th | 69.1 s | 6: 54.9 min | 2400 m |

| 7th | 68.7 s | 8: 03.6 min | 2800 m |

| 8th | 68.6 s | 9: 12.2 min | 3200 m |

| 9 | 69.8 s | 10: 22.0 min | 3600 m |

| 10 | 69.9 s | 11: 31.9 min | 4000 m |

| 11 | 69.9 s | 12: 41.8 min | 4400 m |

| 12 | 70.6 s | 13: 52.4 min | 4800 m |

| 13 | 70.4 s | 15: 02.8 min | 5200 m |

| 14th | 70.0 s | 16: 12.8 min | 5600 m |

| 15th | 69.4 s | 17: 22.2 min | 6000 m |

| 16 | 70.6 s | 18: 32.8 min | 6400 m |

| 17th | 71.0 s | 19: 43.8 min | 6800 m |

| 18th | 70.8 s | 20: 54.6 min | 7200 m |

| 19th | 70.4 s | 22: 05.4 min | 7600 m |

| 20th | 69.6 s | 23: 15.0 min | 8000 m |

| 21st | 71.3 s | 24: 26.3 min | 8400 m |

| 22nd | 69.1 s | 25: 35.4 min | 8800 m |

| 23 | 71.3 s | 26: 46.7 min | 9200 m |

| 24 | 68.8 s | 27: 55.6 min | 9600 m |

| 25th | 63.0 s | 28: 58.0 min | 10,000 m |

|

Kuz 'split times (5000 meter run) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | distance | |

| 2: 44.0 min | 2: 44.0 min | 1000 m | |

| 2: 52.7 min | 5: 36.7 min | 2000 m | |

| 2: 47.2 min | 8: 23.9 min | 3000 m | |

| 2: 48.4 min | 11: 12.3 min | 4000 m | |

| 2: 44.3 min | 13: 56.6 min | 5000 m | |

| World record run (May 30, 1954) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | distance | comment |

| 2: 47.1 min | 2: 47.1 min | 1000 m | |

| 2: 47.2 min | 5: 34.3 min | 2000 m | |

| 2: 49.0 min | 8: 23.3 min | 3000 m | |

| 2: 50.0 min | 11: 13.3 min | 4000 m | |

| 2: 43.9 min | 13: 57.2 min | 5000 m | WR |

| World record run (June 1, 1954) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | distance | comment |

| 2: 47.8 min | 2: 47.8 min | 14: 27.6 min | 1000 m | |

| 2: 56.4 min | 5: 44.2 min | 2000 m | ||

| 2: 54.0 min | 8: 38.2 min | 3000 m | ||

| 2: 55.8 min | 11: 34.0 min | 4000 m | ||

| 2: 53.6 min | 14: 27.6 min | 5000 m | ||

| 2: 55.4 min | 17: 23.0 min | 14: 26.6 min | 6000 m | |

| 2: 53.4 min | 20: 16.4 min | 7000 m | ||

| 2: 55.2 min | 23: 11.6 min | 8000 m | ||

| 2: 55.8 min | 26: 07.4 min | 9000 m | ||

| - | 27: 59.2 min | 6 mi | WR | |

| 2: 46.8 min | 28: 54.2 min | 10,000 m | WR | |

In the spring of 1954, Zátopek's training focused entirely on defending his title in the 5000 and 10,000 meter races at the European Athletics Championships in Bern in August . In March and April alone, he ran 1845 kilometers. He also competed in numerous preparatory races, for example over 5000 meters in the Stade de Colombes in Paris on the evening of May 30th, where Zátopek surprisingly set a world record in a time of 13: 57.2 minutes. Two days later he duped his opponents in a 10,000 meter run in Brussels, broke the “magical” 29-minute mark (28: 54.2 min) and, in addition to setting a new world record over this distance, also achieved the sixth record Miles. He also won over the 5000-meter distance at the national championships in Prague in early August, where he waived the 10,000-meter run in favor of the upcoming European championships in Bern.

Zátopek was a clear favorite for Bern. In the floodlit 10,000 meter race scheduled for August 25th, he won an undisputed victory in a high-class field of competitors ahead of his Hungarian rival József Kovács and Briton Frank Sando with a new European championship record (28: 58.0 min). Contrary to his usual tactic of initially observing the field from midfield, Zátopek took the lead right at the start of the race. On lap ten, his lead over Schade was about 45 meters, which in turn was followed by Kovács, Sando, Mihalić, Driver and the rest of the field. At five kilometers he was already 100 meters ahead of Schade, who in turn was hard pressed by Sando and Kovács. On lap 22 Schade fell back to fourth place. While Zátopek was victorious, Kovács sprinted over his British rival Sando and finished second before him. In the run-up to the 5000 meter race on the following day, Zátopek only managed to qualify for the final with difficulty. The final took place on August 29th in scorching heat and was dominated from the start by the rising Soviet "superstar" Volodymyr Kuz , who gave his opponents no chance and won with a new world record (13: 56.6 min). Zátopek also had to admit defeat to Chataway and finished third.

Zátopek experienced another defeat on October 23, when he lost a 5000 meter run on home soil for the first time since 1948 in the international match against the USSR, again against Kuz. The next day he won the 10,000 meter distance. In total, Zátopek had run 7888 km this year and was awarded the honorary title "Master of Sports".

descent

1955: setbacks

| World record attempt (May 15, 1955) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Split | total time | 5 km Split | distance |

| 2: 51.0 min | 2: 51.0 min | 14: 26.2 min | 1000 m |

| 2: 53.8 min | 5: 44.8 min | 2000 m | |

| 2: 53.0 min | 8: 37.8 min | 3000 m | |

| 2: 54.0 min | 11: 31.8 min | 4000 m | |

| 2: 54.4 min | 14: 26.2 min | 5000 m | |

| 2: 55.8 min | 17: 22.0 min | 15: 06.8 min | 6000 m |

| 2: 58.4 min | 20: 20.4 min | 70000 m | |

| 3: 04.0 min | 23: 24.4 min | 80000 m | |

| 3: 05.0 min | 26: 29.4 min | 9000 m | |

| 3: 03.6 min | 29: 33.0 min | 10,000 m | |

The defeats of the previous year had shown the sporting competition that the dominance of Emil Zátopek, who had previously been considered unbeatable, could be broken. In particular, the “young and wild”, as the now 32-year-old Zátopek called the crowd of urging talents - especially from Eastern Europe - trained mainly according to his principle and achieved top running scores within a very short time. In addition to the Soviet runners Kuz and Anufrijew and the Hungarian Sándor Iharos, this also included compatriot Ivan Ullsperger , who was traded as a possible successor to Zátopek. Regardless of this, he continued to train in the usual manner, planning new world record attempts over the 6-mile distance, the 10,000-meter run in the first half of the year and over the 15 miles and 25,000 meters in the second half of the year due to the lack of international championships.

On May 14, 1955, the world record event over the 6 miles or 10,000 meters took place in the Houšťka stadium in Stará Boleslav. The weather was rough on race day, and Zátopek did not meet his expectations. Ullsperger, who was supposed to act as a pacemaker, hurried away from his mentor from kilometer eight. In the end, both world record targets were missed. Ullsperger also clearly beat Zátopek on May 28 in Brno and on June 9 in Prague over the 5000 meters. On June 16, he crossed the finish line in Belgrade over the same distance as fifth and at the subsequent World Youth Festival in Warsaw only sixth. However, Zátopek showed no signs of resignation and on 24/25. In August 1955 he won the 5000-meter run in the international match against France with a personal best of the year (14: 24.4 min). A week later, he defeated his opponents in the 5000 and 10,000 meter run in the international match against Poland. In the following international match against the United Kingdom in mid-September, he won the 10,000-meter distance from Pirie, but was defeated in the 5000-meter run. In the mid-October city battle between London and Prague, Zátopek was third in the 10,000 meter run; Pirie defeated him again in the 5000 meter race. On October 29 of this year, on the occasion of the opening of the Stadium of Peace in Čelákovice , Zátopek ran his two world records set at the beginning of the year over the 15 miles (1: 14: 01.0 h) and the 25 km (1: 16: 36.4) h), which lasted for almost ten years and was not undercut by Ron Hill until 1965 .

1956: Olympic Games in Melbourne

| Split times | ||

|---|---|---|

| distance | sequence | time |

| 5 km | 1. Kanuti 2. Lee 3. Davis 4. Kotila 5. Mimoun 6. Filine 7. Ivanov 8. Norris 9. Oksanen 10. Karvonen … 17. Zátopek | 16:25 min " " 16:28 min " " " " 16:30 min " ... 16:34 min |

| 10 km | 1. Kotila 2. Mimoun 3. Filine 4. Ivanov 5. Norris 6. Karvonen 7. Kanuti 8. Mihalić 9. Oksanen 10. Perry 11. Nyberg 12. Zátopek | 33:30 min 33:32 min " " 33:34 min " " 33:35 min " " 33:37 min " |

| 15 km | 1. Mimoun 2. Filine 3. Kelley 4. Kotila 5. Norris 6. Mihalić 7. Ivanov 8. Nyberg 9. Karvonen 10. Fontecilla 11. Zátopek | 50:37 min " " 50:38 min " 50:39 min " " 50:40 min " 50:42 min |

| 20 km | 1. Mimoun 2. Mihalić 3. Karvonen 4. Filine 5. Ivanov 6. Kelley 7. Nyberg 8. Perry 9. Kotila 10. Zátopek | 1:08:03 h " " " " " 1:08:11 h 1:08:16 h 1:08:20 h 1:08:26 h |

| 25 km | 1. Mimoun 2. Mihalić 3. Karvonen 4. Kawashima 5. Nyberg 6. Zátopek | 1:24:35 h 1:25:25 h " 1:25:45 h 1:25:53 h 1:25:27 h |

| 30 km | 1. Mimoun 2. Mihalić 3. Karvonen 4. Kawashima 5. Zátopek | 1:41:47 h 1:42:59 h " " 1:43:50 h |

| 35 km | 1. Mimoun 2. Mihalić 3. Karvonen 4. Kawashima 5. Zátopek | 1:59:34 h 2:00:50 h 2:00:58 h 2:01:36 h 2:01:56 h |

| 40 km | 1. Mimoun 2. Mihalić 3. Karvonen 4. Kawashima 5. Lee 6. Zátopek | 2:17:30 h 2:18:44 h 2:19:37 h 2:20:35 h 2:20:46 h 2:21:15 h |

| 42.195 km | 1. Mimoun 2. Mihalić 3. Karvonen 4. Lee 5. Kawashima 6. Zátopek | 2:25:00 h 2:26:32 h 2:27:47 h 2:28:45 h 2:29:19 h 2:29:34 h |

At the turn of the year 1955/56, Zátopek tried to compensate for his dwindling superiority by intensifying training again. Here he pulled a lesion of the groin, which had to be treated surgically in July, which is why he could only compete in a handful of preparatory races for the upcoming Olympic Games in Melbourne , in which he aimed to defend his title in the marathon . In the same month he lost his world records over the 6 miles and 10,000 meters to the Hungarian Iharos.

Therefore, after his arrival in the Olympic village, Zátopek was quite pessimistic that he could build on the performance of 1952. The start of the marathon took place on December 1st at 3:15 p.m. local time at a temperature of over 30 ° C. 46 runners from 23 nations took part in the marathon. The track offered its runners little shade, which is why Zátopek, who started in midfield, wore light headgear. After running about 10 kilometers, a ten-headed group formed, which was followed by a second group, led by Zátopek. After about 15 kilometers, the two groups united. At this point, nine opponents had already given up because of the enormous heat. Mimoun continued to lead, with a lead of about one minute over sixth-placed Zátopek from kilometer 25. This one had problems of his own. The soles of his shoes began to dissolve through the scorching asphalt, causing his residue to grow. With badly aching and bleeding feet, he finally crossed the finish line in sixth place in a time of 2:29:34 hours, more than 4½ minutes behind Mimoun. The audience accompanied him on the last round of the stadium with ovations, at the finish the completely exhausted Zátopek collapsed on the grass. He later announced to the press that this was his last race.

1957: resignation

In March 1957, the now 34-year-old Zátopek announced his intention to retire from active sport at the end of the year. At the same time, he revised his statement last year that he no longer wanted to contest races. He ran a total of nineteen competitions over the 5000 and 10,000 meter distances, of which he won nine - for example in late June in Krakow, where he won the 10,000 meter race in Poland's international match against Czechoslovakia. At his last national championships in late August in his native Prague, he finished second over the same distance. At the beginning of September, Zátopek fulfilled a promise made in 1952 to his former rival Schade and ran another 10,000 meter race in his hometown of Solingen. In this and the following month he also played his last three international matches. The start of this took place on September 14th in Prague, where he finished second against a Hungarian selection in the 10,000 meter run. On September 22nd he won over 10,000 meters in East Berlin, and in the subsequent "second round" a month later on October 12th in Brno he ran over the same distance as second (29: 25.8 min) over the Finish line. In total, he had run more than 80,000 km (over 50,000 miles) during his ten-year running career.

In the following year, Zátopek was still a guest starter at a cross-country event in San Sebastián, Spain, as well as a 10,000-meter run in Beijing . Then he decided against working as a trainer and devoted himself to his service duties in the Ministry of Defense. From 1960, various foreign delegations took the Zátopek couple to China, Korea, Vietnam, Egypt, Tunisia, Syria and Cuba, followed by an almost one-year stay in Indonesia in 1963. In addition, the most prominent Czechoslovakian sports couple was visited by former comrades-in-arms, companions and up-and-coming young sports talents, with whom Zátopek corresponded by letter in addition to personal conversations.

Prague spring

Personal role

Zátopek took an active part in the Prague Spring , a reform movement that tried to initiate the liberalization and democratization of Czechoslovakia. Together with his wife, the ski jumper Jiří Raška and the gymnast Věra Čáslavská , he was one of the four Olympic champions who signed the 2000 Words Manifesto with other high-ranking personalities from the country , especially because he felt connected to the basic ideals of socialism.

On the night of the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops on August 20-21, 1968 in Prague, which put an end to reform efforts, Zátopek was on his way home from a celebration. In the early morning of August 21, he hurried in civilian clothes to Wenceslas Square , where thousands of demonstrators had already gathered to stand in the way of the Russian tanks that had been driven out. Once there, he spoke from the pedestal of the Wenceslas statue to his fellow citizens and a handful of Western journalists and condemned the invasion in the strongest possible terms. The situation escalated when the tanks were attacked with cobblestones by angry crowds and Soviet troops stormed the premises of Radio Praha and displaced its employees at gunpoint. During the day there were numerous dead and injured on both sides. Zátopek then decided to use his popularity to talk to Soviet soldiers. So he climbed onto a Soviet tank in uniform and appealed to its crew to go home again. In the following days he looked for further dialogues with Soviet officers and tried in vain to persuade them to use the argument of “peaceful coexistence” in the spirit of the upcoming 1968 Olympic Games to be moderate.

Zátopek then stepped up his activities and, for example, pasted walls with protest posters. On August 22nd, he spoke again to a large crowd in Wenceslas Square. Among other things, he demanded the exclusion of the Soviet Union from this year's Olympic Games. In addition, he accused the Soviet armed forces of deliberately and unlawfully violating the sovereignty of a peaceful socialist brother state . After another public conversation, this time via an illegal free radio station on August 23, Zátopek, who stayed in different houses during these critical days in order to avoid a possible arrest, came under the sights of the KGB and the Czechoslovakian secret service StB . At this point, Zátopek knew that his military career would be over.

On August 24, in a printed newspaper interview, he repeated the demand to exclude the Soviet Union from the Olympic Games, to which he and his wife had already been invited as guests of honor. For this reason he feared no reprisals for the time being. On August 26th, he gave a final interview to a French film crew, in which he once again granted the Czechoslovak people the right to sovereignty and sharply condemned the Soviet intervention. The Moscow Protocol , which effectively ended the Prague Spring, was ratified on the same day . Subsequently, Zátopek and his wife traveled unscathed to Mexico City , where they attended the games together. In interviews there, Zátopek held back with critical statements towards the Soviet Union or the Czechoslovak government and was diplomatically cautious. After the Games, the Zátopeks returned to Prague at the end of October 1968, where government officials prevented any contact with foreign media representatives. When British journalists there offered the couple an escape to Great Britain, he refused. In November 1968, Zátopek was ordered by the Ministry of Defense under threat of official consequences to refrain from further criticism of the system and to submit to the regulations and rules of the army.

defamation

At the beginning of 1969 Zátopek began to be publicly discredited - with a statement by the East German long-distance runner Friedrich Janke , who accused him of being able to change his "political convictions like a shirt", and with an article in the sports magazine Sovetsky Sport in which Zátopek was called " Traitor ”. After the self-immolation of the student Jan Palach on January 19, 1969 in protest against the crackdown on the Prague Spring and other imitators, Zátopek sought contact with angry students on the street. Among other things, he received an official reprimand from the Ministry of Defense on January 19 and was relieved of his post. At the same time he was transferred to the post of youth coach at FK Dukla , which amounted to a demotion.

On February 20, 1969, Vilém Novy , a member of the Central Committee of KSČ, claimed that Palach had been persuaded to take his action by a group of conspirators and that they accepted his death. In addition to Zátopek, the accused included the writers Vladimír Škutina and Pavel Kohout , the chess player Luděk Pachman and the student leader Lubomír Holeček . Four weeks later, the accused filed a defamation suit against Novy's absurd allegation, which was unsuccessful. After Zátopeks made further derogatory remarks, including that the expenses for the Czechoslovak army would have been better used for education, he was suspended from his work as a youth coach on April 21, 1969. A military judicial proceeding was initiated against him, in which he was accused of illegal political activities, dissemination of false reports and refusal of orders. He denied all allegations and declared in front of press representatives that he was not an enemy of the state or a counter-revolutionary. However, Zátopek was made a scapegoat, discharged from the army with effect from October 1 of that year and at the same time expelled from the party in which he had supported the democratic wing. A prison sentence was waived because of his earlier achievements and because of objections by letters from Western athletes and friends to the government, which would have meant an immense loss of prestige for the country. His discharge from military service was part of a nationwide wave of political cleansing that cost around 11,000 officers and 30,000 NCOs their jobs by the mid-1970s.

consequences

Deprived of his financial income and sporting activities, Zátopek made his way through as a persona non grata first as a garbage collector before he, with the help of friends, found a job in the large company Stavební Geologie , which explored natural resources on behalf of the state. In addition, the company, which had more than 1000 employees, was active in well, trench and underground construction as well as in the drilling business. Zátopek worked here as a migrant worker until 1973, sometimes under extremely difficult working conditions. The often weeks-long missions led to family differences and severe alcoholism. The construction crew, to which Zátopek belonged, was housed in ordinary construction trailers, called maringotka. When a Spanish sports official came to see him at work, he was shocked by the physical decline and the treatment of the former world star. However, Zátopek endured the tasks assigned to him, which also included tunnel work in the former uranium mine Důl Svornost , with sporting ambition. On one of his rare visits to his home in Prague, he was beaten up in the street by members of the army. He endured this and other reprisals such as the erasure of his name from school books and the renaming of the stadium in Houšťka that was named after him with indifference and resigned himself to the given situation; he earned relatively well, lived undisturbed in his house and had friends who stood by him. During this time, Zátopek must have undergone a certain kind of purification, which is supported by his statement: "I was ready to go to the edge of the abyss, but not to jump into it!"

Zátopek was invited as a guest of honor to the Olympic Games in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1972 , which put the Czechoslovak government under pressure. On the one hand, it was difficult to convey to western countries why a former top athlete in the country was treated like a criminal worker. On the other hand, people were aware of Zátopek's outstanding sporting achievements and their propaganda benefits. On the other hand, there were fears that Zátopek might use the trip to escape. The acceptance of the invitation was finally granted to Zátopek on the condition that his wife had to remain in Prague as a bargaining chip. Zátopek accepted this and traveled to the Bavarian capital of Munich in the summer of 1972. There he met numerous former and active athletes, companions and politicians such as the incumbent Chancellor Willy Brandt . He refrained from making political statements. To close friends, however, he admitted that during these days he felt that he was being treated as a person again. The games were overshadowed by the hostage-taking of Munich , which Zátopek deeply shocked as an advocate of the Olympic idea. Hundreds of autograph hunters awaited him at Munich Airport on the day of his departure.

New beginning

In the summer of 1973 the relationship between the state leadership and Zátopek slowly began to normalize, especially since he had already publicly revoked his signature on the 2000 Words Manifesto two years earlier . This counter-declaration and other state-loyal declarations met with incomprehension on the part of the dissident movement . In October 1973 Zátopek was allowed to travel to Helsinki for the funeral services of his idol Paavo Nurmi . At around the same time, the restrictions on him were gradually lifted in the course of Czechoslovak normalization , as it was assumed that Zátopek would no longer pose a threat to the state and the party. In 1974 he got a job at the Sports Documentation Center in Prague and was again allowed to visit friends and acquaintances abroad on a regular basis. His small office was in a side wing under the Strahov Stadium . There he was entrusted with the screening and evaluation of foreign sports publications. Zátopek described the work as undemanding and modest and saw himself in the role of a "sports spy". His new field of activity, which he carried out until he retired in 1982, was largely perceived positively internationally.

In 1975 Zátopek received the “Fair Play Prize” from UNESCO in Paris and in 1977 the “First Class Diploma” from the President of the National Association for Physical Exercise. In the same year he was a guest of honor at the New York City Marathon and had an appearance in the film series M * A * S * H , where Zátopek played himself in the episode The M * A * S * H Olympics . Zátopek, shaped by his experiences in 1968, did not take part in the country's liberalization movement, which began in 1977 under the name Charter 77 . In the following years he was a guest at numerous sporting events, including 1980 in Switzerland and Japan and in 1981 as the starter for the Frankfurt Marathon . In 1983 he was present at the World Athletics Championships in Helsinki and then attended a street race named after him in Melbourne. He turned down the IOC's invitation to the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles as part of the boycott by the Warsaw Pact states. Zátopek, who had been suffering from cardiovascular problems for several years, suffered a heart attack in 1986, which was due, among other things, to his unhealthy lifestyle during his years as a migrant worker and to excessive alcohol consumption. In 1987 he was again the starter, this time for a fun run in London's Hyde Park . The following year he played a major role in the first friendship run between the twin cities of Wuppertal and Košice .

Turning times

rehabilitation

With the Soviet policy change under Mikhail Gorbachev to perestroika and glasnost and the renunciation of Soviet hegemony in East Central Europe , far-reaching reform and democracy movements occurred from autumn 1988/89, first in Poland, later in Hungary, Bulgaria and the GDR, which in the end collapsed of the respective regime and ended in a system transformation . In Czechoslovakia this happened from October 1989 under the term of the Velvet Revolution . Zátopek, burdened by the experiences from 1968, reacted cautiously to the political upheavals in his country. The first riots broke out in Prague on November 17, 1989 when a student demonstration was beaten up by police officers. Protests, strikes and mass demonstrations with several 100,000 participants followed. The government resigned on November 30th. Václav Havel , who later became the first President of the Czech Republic, immediately announced free elections. On December 1, 1989, over a million people gathered on the Letná Plain outside Prague, including the Zátopeks, who had previously only followed the events on television. After Havel took office in December 1989, a far-reaching declaration of amnesty for the politically persecuted followed; Zátopek was officially rehabilitated on March 11, 1990. The new Defense Minister Miroslav Vašek also apologized publicly for Zátopek's dismissal from the army.

With the democratization and opening of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic towards the West, Zátopek's popularity and thus media interest rose by leaps and bounds. He conducted countless interviews and discussions with Western journalists and former companions and friends. Zátopek made use of the new freedom to travel, visited friends in Argentina and the United States and was a guest at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona, Spain .

Last years of life

Zátopek was a guest at the 1994 European Athletics Championships in Helsinki. During a trip to Greece in 1995, he suffered a minor stroke at Athens Airport, from which he was able to recover quickly. As a result, Zátopek, who was now very overweight, became increasingly depressed, which was exacerbated by the loss of most of his siblings and close friends. These included, for example, Gordon Pirie († 1991), Gaston Reiff († 1992) and Reinaldo Gorno († 1994). In June 1995, Zátopek was a guest starter in the Prague Marathon . A little later he had a cameo appearance in a commercial for his long-time sponsor Adidas , who had equipped him with shoes and clothing during his active time. In September of that year he traveled to the ISTAF Berlin , where the filmmaker Hagen Boßdorf accompanied him and made a documentary about it. From 1996 onwards, Zátopek's health continued to deteriorate. Walking became increasingly difficult for him, and at times he was dependent on a walking stick. In addition, senile dementia started in 1997 . In the same year he was voted “Athlete of the Century” in the Czech Republic. In 1998, President Havel awarded him the Gold Medal of Merit , whereas other sources mention the Order of the White Lion . That year Zátopek suffered a second stroke that led to temporary loss of speech. In 1999 he gave one final interview to a British newspaper reporter.

Death and burial

After suffering from severe pneumonia and further strokes, Zátopek was taken to the Central Military Hospital in Prague in late summer 2000, where he died of the effects of his last stroke on November 21, 2000. Zátopek's death caused dismayed reactions in the media both nationally and internationally. The funeral ceremony with 800 guests from all over the world and high-ranking representatives such as Prime Minister Miloš Zeman took place on December 6, 2000 in the Prague National Theater. The state funeral proposed by Havel was kept simple at the widow's request. After the funeral, the coffin, covered with the state flag and carried by the highest athletes in the country, was transferred to a crematorium for cremation. On the same day, Zátopek was posthumously awarded the Pierre de Coubertin Medal for exceptional athletic behavior by the IOC and the Golden Order of Merit by the IAAF . His urn was buried in the Valašský Slavín cemetery in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm .

reverberation

Appreciations

Two years after his death, a monument to Zátopek was inaugurated in Prague. Two other statues of him can be found at the stadium in Zlín and on the grounds of the Olympic Museum in Lausanne. The asteroid (5910) Zátopek , discovered in November 1989, was named after him in 1996. In December 2006, the Czech State Railways named an express train after him, and in 2016, Škoda Transportation named the Škoda 109E locomotive . Jean Echenoz published in 2011 under the title Laufen (original title: Courir ) a novel biography about Zátopek. In 2012, he was one of twelve athletes in the first selection of the newly created IAAF Hall of Fame . In February 2013 the journalists of Runner's World magazine voted him “Greatest Runner of All Time”. Several schools have also been named after him, such as the elementary school in Kopřivnice and schools in Zlín and Třinec . At the 2016 Olympic Games , every Czech athlete wore stick figures that were modeled on him in memory of Zátopek on their sportswear. In his honor, the performance artist David Černý exhibited plastic replicas of Zátopek's legs in Prague, Rio and other cities around the world in connection with the games.

Relationship to the state security service

After the previous Czechoslovak security authorities were dissolved in the system transformation from 1990, the files of the former State Security Service (StB) were made accessible to the public; from 1998, allegations were publicly discussed that Zátopek might have worked as an informant.

In the existing documents, Zátopek is led under the code names “Atlet” and “Macek”, although there are no handwritten records from him. Zátopek never made any public statements about any activity as an informant. Theses about a precise activity are therefore speculative. As a member of the army, Zátopek may have written notes for the StB during his numerous trips abroad, none of which have survived. It is also possible that his mentions by name are based on observation reports by StB employees or that Zátopek - in whatever form - was forced to cooperate. The only statement clearly incriminating Zátopek comes from the former tax agent Josef Frolík (1928–1989), who accused him in his 1976 memoir Frolik Defection of having worked for the tax office and as a targeted agent provocateur at the Prague Spring. However, the accusations are difficult to reconcile with the drastic repression against Zátopek from 1969, which makes Frolík's credibility appear questionable. If Zátopek was involved in the state security service, it cannot be clarified based on the current state of knowledge.

Relationship to the state party

Zátopek was from December 1953 a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), with whose goals he could only partially identify. According to his own statements later, he only became a party member because he was forced to do so as an officer and member of the army. Probably for this reason, as early as the early 1950s, he was certified as having a lack of political awareness, which is why he was delegated to a political school. His political activities were limited to the bare minimum, but occasionally he let himself be called in as a “model athlete” for political speeches on his trips abroad. It was not uncommon for Zátopek to have to draw blank sheets of paper, which were only filled with propagandistic phrases after his signature. Nevertheless, Zátopek was also promoted and conducted by the KSČ. Otherwise he did not skimp on criticism of the party and thus of the government, even if this had to be presented rather cautiously until 1968. The first tougher confrontation with the party and state leadership had occurred in the run-up to the 1952 Olympic Games in the "Jungwirth" affair, in which Zátopek was ultimately able to prevail due to his popularity with his demand for his participation. In the following years he behaved diplomatically with caution or ended any interviews that drifted to a political level, as otherwise he would have to expect imprisonment. In this context, his statement has been handed down: “I'll stop talking now, else they'll lock me up!” (Eng. “I'll stop talking now, otherwise they'll lock me away!”). After the events of the Prague Spring in 1968, Zátopek was expelled from the party.

Relation to the Milada Horáková case

| Zátopek's open letter from Rudé právo |

|

|---|---|

| original | translation |

|

Rozsudek vynesl všechen československý lid Slova pana presidenta, která pronesl na I. sjezdu ČSM, když citoval starou revoluční píseň "Nechť zhyne starý, podlý svět, my nový život chcem na zemi!", Jsou pro nás vlastně myšlenky, které nás váseded Vždyť my již nový život budujeme. A přece se našly zrůdy, které chtěly zničit naši výstavbu a cestu k socialismu.

Počinání všech špionů a zrádců je hanebné a stejně tak pošetilé, protože náš lid, který si vybojoval lepší podmínky pro život, se jich nikdy nevzdá a dějinný vývoj se neví do star jižát. Lidé se přesvědčili o štěstí socialismu, o shodě a spolupráci a nedají si nikdy svá práva vyrvat z rukou. Diversanti se odsoudili sami svými činy - rozvratnictvím a přípravou války proti vlastnímu národu. Rozsudek je výstrahou pro všechny, kteří by u nás v Českolovenské republice hledali působiště pro své hanebné cíle. Všichni naši pracující budují společně svůj lepší život a každý, kdo by chtěl narušit naši společnou práci, skončí tam, kde skončila banda špionů a diversantů. Rozsudek vynesl všechen československý lid. Jako příslušník československé armády vidím, že rozsudek - toť přikaz, který vyplývá z poctivé práce všech našich délníků pro nás vojáky, aby pokojný život byl zachován. Kpt. Emil Zátopek |

The verdict was pronounced by the entire Czechoslovak people The words of our President, which he uttered at the 1st Congress of the ČSM when he quoted the old revolutionary song “May the old, vile world perish, we want a new life on earth!”, Are also our own thoughts lead us forward. Because we are already building a new life. And yet there were monsters who wanted to destroy our construction and the path to socialism.

The behavior of these spies and traitors is both shameful and foolish, for our people, who have fought for better living conditions, will never give up their historical development and will never return to the old days. People are convinced of the benefits of socialism, harmony and cooperation and will not allow them to take their rights from them. The subversives have condemned themselves through their actions - through their disruptive activity and through their preparation for war against their own nation. The judgment is a warning to all those who are looking for a field of activity in the Czechoslovak Republic for their wicked goals. All of our working people are building a better life together and anyone who wants to disrupt our work together ends where this bond of spies and divers ended. The verdict was pronounced by the entire Czechoslovak people. As a member of the Czechoslovak Army, I recognize - that the peaceful coexistence that results from the hard work of all our workers and soldiers was preserved by this judgment. Captain Emil Zátopek |

The personal role of Zátopek in the case of the Czechoslovak opponent Milada Horáková , who was executed on June 27, 1950, is still the subject of controversy. The judicial proceedings initiated after her arrest turned into a show trial that was unique in the country to date, initiated and controlled in every detail by the KSČ. The trial was broadcast nationwide through all media; even in schools, universities, at work, in specially convened meetings or via street loudspeakers. It was not uncommon for those present there to be forced to sign prepared petitions, which explained Horáková's guilt and betrayal of the socialist cause. Later, these agitations were extended to intellectuals and cultural workers, but also athletes, in order to be able to stage the condemnation as being borne by the entire people. In this context, two days after Horáková was sentenced to death on June 8, 1950, a letter signed by Emil Zátopek appeared in the party newspaper Rudé právo (“Red Law”), which disapproved of Horáková's behavior and branded her as a spy and traitor of socialism. The "subversive elements", as well as Horáková there were other defendants, are to be brought to justice.