Rail transport in Japan

The rail transport in Japan is an important mode of transport in passenger transport . The rail network in Japan is one of the densest in the world. In 2015 it had a length of 27,311 km, of which 20,534 km were electrified.

The network is currently (2017) divided between 127 railway companies. Almost three quarters of the entire (predominantly Cape-gauge ) route network is accounted for by six companies of the JR Group , which were established in 1987 after the privatization and division of the Japanese State Railways . Five of these companies are involved in the operation of the Shinkansen high-speed trains, which run at speeds of up to 320 km / h and whose standard-gauge route network extends over the three largest islands in the country. The “big 16” , highly profitable private railways in the metropolitan areas of Tokyo , Osaka and Nagoya are also important . Despite their intensive use and high traffic density, Japanese railways are considered to be extremely punctual.

Systematics of rail transport in Japan

JR group

The Japan Railways Group , commonly known as the JR Group ( JR グ ル ー プ , Jeiāru Gurūpu ), is the umbrella term for seven legally independent railway companies that succeeded the privatized Japanese State Railways on April 1, 1987 . The JR Group is at the heart of the Japanese rail network; it operates almost the entire supraregional express train traffic and a significant part of the local rail passenger traffic in the metropolitan areas.

The passenger transport companies of the JR Group each serve a specific geographic region, but also operate long-distance trains beyond the borders of these regions. They are:

- Central Japan Railway Company (JR Central; English for JR Tōkai)

- East Japan Railway Company (JR East; JR Higashi-Nihon)

- Hokkaido Railway Company (JR Hokkaido)

- Kyushu Railway Company (JR Kyushu)

- Shikoku Railway Company (JR Shikoku)

- West Japan Railway Company (JR West; JR Nishi-Nihon)

The rail freight is by the Japan Freight Railway Company (JR Freight; JR Kamotsu) performed. All have the legal form of a private stock corporation ( kabushiki-gaisha ; English translation generally arbitrary, in the case of the JR companies only "Company"). But of the JR group companies, only JR Central, JR East and JR West are fully privatized. The rest are owned by the Japan Railway Construction, Transport and Technology Agency (English for the tetsudō kensetsu, un'yū shisetsu seibi shien kikō 鉄 道 建設 ・ 運輸 施 設 整 備 支援 機構 ), a self-governing body ( dokuritsu gyōsei hōjin , English "Independent Administrative Corporation "and the like) under the supervision of the MLIT . There are also two downstream companies that provide joint services for all JR companies.

With the exception of JR Shikoku, all passenger transport companies in the JR Group are involved in the operation of the Shinkansen high-speed network. It comprises seven routes with a total length of 2764.7 km (as of 2016), which can be traveled at speeds of up to 320 km / h. The Tōkaidō Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka , which opened in 1964, was the world's first railway line designed specifically for high speeds. This was followed by the San'yō-Shinkansen from Osaka to Fukuoka (1972-1975), the Tōhoku-Shinkansen from Tokyo to Aomori (1982-2010), the Jōetsu-Shinkansen from Ōmiya to Niigata (1982), the Hokuriku-Shinkansen from Takasaki to Kanazawa (1997-2015), the Kyūshū Shinkansen from Fukuoka to Kagoshima (2004-2011) and the Hokkaidō Shinkansen from Aomori to Hakodate (2016). The latter uses the Seikan Tunnel , which went into operation in 1988 and which was the longest railway tunnel in the world until the Gotthard Base Tunnel opened in 2016. Under construction is u. a. the Chūō-Shinkansen from Tokyo via Nagoya to Osaka, which is designed as a magnetic levitation train and should enable a speed of 505 km / h.

Important private railways

Japan has a large number of private railway companies, some of which already existed during the early stages of state railway operations. They proved to be far more profitable, especially in the metropolitan areas, and acquired an excellent reputation through efficient management. The government encouraged competition between private companies, both among themselves and with the state railways. They were able to set their own tariffs, but also received no subsidies. For this reason, they were forced early on to diversify into other business areas and to develop large-scale property developments in the catchment area of their routes .

Especially after the Second World War, the large private railways were able to build densely built-up planned settlements with residential, business, industrial and shopping areas in their traffic corridors and thus generate a transport demand that optimally benefited their vertically integrated corporate groups. For these reasons, most private railways in the metropolitan areas of Japan are financially independent and rail operations are generally profitable - a striking contrast to many transport networks in other countries.

The most important of these private railways are grouped under the name “the big 16”. They are:

Other railways

In addition to the “big 16”, there are several dozen small private railways in Japan in rural and suburban areas, most of which only operate one or two lines. The railways in the so-called “third sector” ( 第三 セ ク タ ー , daisan sekutā ) represent a specialty . These are collaborations between the public sector and private companies. These can be divided into five groups:

- Lines operated by (or the construction of which has been started) by the Japanese State Railways and which have been transferred to a third-sector rail company;

- Old lines parallel to Shinkansen high-speed lines that were sold by companies of the JR Group when they opened;

- loss-making lines of private railways that no longer want to operate them and surrender them to the public sector;

- Freight railways that were newly built for the development and access to port areas;

- isolated local transport routes in urban areas.

Legal basis

In a legal sense, there are two types of rail transport systems in Japan (with several subcategories): railways ( 鉄 道 , tetsudō ) and trams ( 軌道 , kidō ). Every rail transport system with public transport is classified as either a railroad or a tram, whereby the choice between the two legal bases is in certain cases arbitrary and does not necessarily correspond to the usual idea. For example, the Osaka Subway is legally a tram, but the subways in other cities are not.

Railways and trams are regulated in the Railway Business Act ( 鉄 道 事業 法 , tetsudō jigyō hō ; English "Railway Business Act") of 1986 and in the Tram Act ( 軌道 法 , kidō hō ) of 1978.

Common characteristics in passenger transport

Gauge

The Japanese railway network has lines with the following gauges (as of 2015):

- 1067 mm ( Cape gauge): 22,207 km, of which 15,430 km are electrified. Standard gauge in Japan for general passenger and freight traffic.

- 1435 mm ( standard gauge ): 4,800 km, all electrified. Used on high-speed lines, subways and suburban lines.

- 1372 mm (Scottish gauge): 124 km, all electrified. Used on Keiō Dentetsu routes and on trams.

- 762 mm: 48 km, all electrified: used on rural branch lines.

- Three- rail tracks 1067 and 1435 mm: 132 km, all electrified.

The fact that the Cape Gauge became the Japanese standard gauge is due to the British engineer Edmund Morel , who was responsible for building the first line between Tokyo and Yokohama . In doing so, he relied on experience he had gained in building railways in New Zealand .

electrification

The first electric rail vehicle ran in 1890 on a temporary demonstration route in Ueno Park in Tokyo. After initially various tram companies had permanently introduced the new type of traction , the Kōbu Tetsudō followed as the first railway company in 1904 , which electrified a section of the Chūō main line (for more on this see rail electrification in Japan ).

Today there are five main traction power systems .

- 1500 V DC voltage : With a share of over 60%, it is the most widely used traction current system. Use on main and branch lines of JR Central, JR East, JR Kyushu, JR Shikoku and JR West as well as on many private rail lines.

- 20 kV 50 Hz alternating voltage : main and branch lines from JR East in the Tōhoku region, JR Hokkaido, isolated private railways in eastern Japan;

- 20 kV 60 Hz alternating voltage: Main and branch lines from JR Kyushu, isolated private railways in western Japan;

- 25 kV 50 Hz AC voltage: Shinkansen high-speed lines in eastern Japan;

- 25 kV 60 Hz AC voltage: Shinkansen high-speed lines in western Japan.

Overhead lines are mainly used, while busbars are only used in underground trains. A few private railways use a direct voltage of 600 V or 750 V.

Clearance profile

The clearance profile on the Shinkansen network has a maximum width of 3,380 mm and a maximum height of 4,485 mm. This allows the use of double-deck high-speed trains. On the conventional route network, the clearance profile is 3,000 mm in width and 4,100 mm in height. On some lines of the JR Group, which were built by private companies before nationalization at the beginning of the 20th century, the clearance profile is slightly smaller with a height of 3,900 mm. This affects the main Chūō line west of Takao , the Minobu line and the Yosan line west of Kan'onji . However, advances in the development of pantographs have largely eliminated the need for different vehicles in these regions. The private railways have very different clearance profiles.

Signals

The Japanese railroad signals are set out in a 2001 MLIT ministerial decree . In the beginning, Japan took over British railway signaling technology. This includes the route signaling, which shows the driver whether and where he is allowed to go. He had to know for himself how quickly he could be there. Later, the Japanese railway companies oriented themselves more towards the USA, where speed signaling predominates, i.e. the highest permitted speed is indicated, but different routes can be released by the same signal. This created a mixed system of route and speed signaling.

A special feature is the safety measure known as Shisa kanko , in which locomotive and railcar drivers point to signals and other important things and call them out loud. This is to avoid errors, increase awareness and reduce reaction times.

Series

The first nationwide uniform numbering and classification scheme for steam locomotives was introduced in 1909 (previously the railway companies had their own, incompatible schemes). As it was soon no longer sufficient to also include electric and diesel multiple units, an expanded scheme came into force in 1928, the main features of which have continued to this day.

The Association of Railway Friends ( 鉄 道 友 の 会 , Tetsudōyū no kai ) has been awarding the Blue Ribbon Award for rail vehicles with outstanding design every year since 1958 .

Train types and names

Several types of train ( Zug 列車 別 , ressha shubetsu ) usually run on suburban lines and long-distance lines , depending on how many stations are served on the way. In addition to the Japanese, they also have English names.

To travel on a passenger train ( 普通 列車 , futsū-ressha or 各 駅 停車 , kakueki-teisha ) stopping at all stations, all you need is a ticket at the basic rate. Faster trains are called "Rapid" ( 快速 , kaisoku ), "Express" ( 急 行 , kyūkō ), "Limited Express" ( 特急 , tokkyū), Home Liner ( ホ ー ム ラ イ ナ ー ) or similar and require, depending on the tariff provisions of the respective Railway company, a surcharge on the base rate. Railway companies with many train types use prefixes such as “semi-”, “rapid-”, “section-” or “commuter-”.

In long-distance transport , railway companies give the trains specific names for easier identification (a rare exception is Kintetsu ). When booking tickets, the train names are used instead of the train numbers. Train numbers are almost only important for internal use.

Night trains once ran on numerous lines, but due to the aging of the rolling stock and growing competition from night long-distance buses and low-cost airlines , their number has steadily decreased since the beginning of the 21st century. Since the spring of 2016, only the Sunrise Izumo and the Sunrise Seto from Tokyo to Izumo and Takamatsu have existed .

Names of the railway lines

The names of all railway and tram lines in Japan are determined by their operators. In principle, a route section only has one name (with a few exceptions). The line name can be derived from a destination or a city along the line. For example, the Takasaki line goes to Takasaki . Other possibilities are a traversed region (e.g. the Tōhoku main line in the Tōhoku region ), an abbreviation of provinces or cities (e.g. the Gonō line connects the cities of Goshogawara and Noshiro ), or the direction of a line ( Tōzai- Line means "east-west line").

Tickets, tariffs and supplements

The fare is based on the base rate ( 普通 運 賃 , futsū-unchin ) based on the distance traveled, to which numerous types of surcharges can be added. For the companies of the JR Group, these are, for example:

- Express surcharge ( 急 行 料 金 , kyūkō ryōkin )

- Limited express surcharge ( 特急 料 金 , tokkyū ryōkin )

- Express surcharge without reservation ( 自由 席 特急 料 金 , jiyūseki tokkyū ryōkin )

- Surcharge for seat reservations ( 指定 席 料 金 , shiteiseki ryōkin ) on all trains except Limited Express

- Green Fee ( グ リ ー ン 料 金 , gurīn ryōkin ) for seats in special first-class cars called "Green Car"

- Shinkansen surcharge ( 新 幹線 料 金 , shinkansen ryōkin ) for trips on Shinkansen high-speed trains

- Sleeper surcharge ( 寝 台 料 金 , shindai ryōkin )

Two special offers are also available from companies in the JR Group. The Japan Rail Pass is aimed at tourists and is only available in travel agencies outside of Japan. It is valid for 7, 14 or 21 consecutive days on the entire route network of the participating companies. The Seishun 18 Kippu enables nationwide journeys on regional trains; Although it is only valid during the university's non-teaching hours and the offer was originally intended for students, there are no restrictions on use.

Most passengers buy their tickets from machines ; They are checked and canceled at automatic platform barriers . The conductors on the trains only check the supplements. Electronic tickets based on the FeliCa system developed by Sony , which uses RFID technology , are widely used . Such cards are available for practically every metropolitan area ( e.g. Suica in the Tokyo area), and these are usually compatible with one another.

punctuality

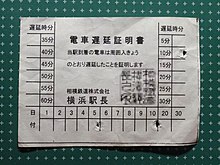

Japanese rail transport is known for its extremely high level of punctuality , more than in any other country. For example, the average delay of a train on the Tōkaidō-Shinkansen high-speed line operated by JR Central was just 0.2 minutes in 2016 (including natural disasters). If a train is five minutes or more late, the conductor makes an announcement and apologizes to the passengers for the inconvenience this caused. The railway company then issues a train delay certificate ( 遅 延 証明書 , chien shōmei sho ), which can be presented to the school or the employer. There are also certificates in electronic form that can be printed out if necessary.

There are several reasons for punctuality. Speed limits are unknown, as maintenance work is almost always carried out during the nightly shutdown. High quality standards apply to the development and maintenance of vehicles. The operational processes are largely automated (only a small part of the route network is controlled by non-automatic signaling systems). Stepless entry and exit, the marking of the door position on the platform and centrally controlled opening and closing of the doors ensure short stopping times. Despite a number of capacity expansions, the trains are often overcrowded during rush hour and oshiya (“pushers”) are used to push passengers into the cars. In this way, the passenger switching time should be reduced, which also contributes to punctuality.

The railway workers do their work with great discipline, which at the same time puts them under great pressure. In the event of mistakes or small delays, it is not uncommon for you to endure degrading disciplinary measures. A particularly extreme form of this error culture is seen as the cause of the Amagasaki railway accident on April 25, 2005, in which 107 people were killed: a train driver wanted to catch up with a delay due to excessive speed for fear of punishment, causing the train to turn in a tight curve was thrown off the track.

Urban rail transport

Subways

Nine Japanese cities have a subway network. The largest is the Tokyo subway . Two companies, Tōkyō Metro and Toei , operate a total of 13 lines with a total length of 304.1 km. Opened in 1927, the Ginza Line is the oldest subway line in Asia. The first line of the Osaka subway followed six years later ; today it has six lines with a total length of 129.9 km. Seven more subways were added from the late 1950s. They are located in Fukuoka , Kobe , Kyoto , Nagoya , Sapporo , Sendai and Yokohama .

Subways in Japanese cities are usually by directing companies operated the respective municipality and therefore seldom cross the city limits. In many cases, this disadvantage is offset by the fact that underground lines and the connecting railway lines to the surrounding area are connected to one another without having to change trains .

Trams and light rail vehicles

Japan's first electric tram ran in Kyoto in 1895 . Numerous other cities followed shortly afterwards. Although some smaller businesses were closed after the First World War, there were still 83 businesses in 67 cities in 1932, which together operated a route network of 1,480 km in length. After a wave of shutdowns in the 1960s to 1980s (as a result of mass motorization ), fewer than a quarter of the companies remained, whose route networks had also shrunk significantly.

Today there are still 17 tram companies in Fukui , Hakodate , Hiroshima , Kagoshima , Kōchi , Kumamoto , Kyōto , Matsuyama , Nagasaki , Okayama , Osaka / Sakai , Ōtsu , Sapporo , Tokyo ( Toden-Arakawa-Line and Tōkyū Setagaya-Line ), Toyama and Toyohashi . The largest network with a length of 35.1 km is located in Hiroshima. The renaissance of the tram has so far mainly been noticeable with the introduction of low-floor vehicles, while new routes are still rare. New light rail operations (on old railroad lines) are the Man'yōsen in Takaoka and the Toyama Light Rail . The Utsunomiya light rail has been under construction since May 2018 and is due to open in March 2022.

Other railways

Japan has the largest number of monorails after the USA . In contrast to other countries, their task is not limited to that of a short airport shuttle or an attraction in an amusement park, but often also opens up densely populated urban districts and converted port areas. The Tōkyō Monorail , which opened in 1964, is most successful with over 300,000 passengers a day. Other significant systems are the Chiba Monorail , the Kitakyushu monorail , the Okinawa Monorail , the Tama monorail, and the Osaka Monorail .

People mover systems of various types are also widespread . Examples are the Astram in Hiroshima, the Linimo east of Nagoya as well as the Nippori-Toneri Liner and the Yurikamome in Tokyo.

Two dozen funiculars and two trolleybus operations ( Kanden Tunnel Trolleybus and Tateyama Tunnel Trolleybus ) serve primarily tourist purposes .

Freight transport

In contrast to Europe or North America, rail freight transport is of little importance in Japan. In 2015, its share of total inland freight transport was only 5% of tonne-kilometers , while coastal shipping accounted for 44% and trucks for 50% . In 1965, the share of rail freight traffic was 31% of tonne-kilometers, by 1998 it had fallen to 4%. A shift in traffic from trucks to freight trains has been observed since the 2010s . On the one hand, this is due to the government's climate policy measures to reduce CO 2 emissions . On the other hand, there is a serious shortage of truck drivers, who are also increasingly over-aged. The MLIT aims to increase the volume of goods transported by rail by a fifth by 2020.

99% of the rail freight transport is carried out by the Japan Freight Railway Company (JR Freight), which was established in 1987 as part of the privatization of the state railways. It is the only railway company operating in all of Japan. However, it has only a few of its own tracks, mainly access roads to freight yards and loading points. Otherwise, it rents the required rail infrastructure from the other companies in the JR Group. In 2014, JR Freight transported a total of 30.3 million tons of goods, of which 71% was containerized . In addition to JR Freight, there were eleven other freight transport companies in 2015, with a combined share of 1%. These are usually short branch lines in ports and industrial zones. Such companies are usually jointly owned by JR Freight and shipping companies.

history

Development of the rail network and industry

As in 1853, the Black Ships in the Bay of Edo landed and the end of Sakoku forced, let Commander Matthew C. Perry perform a miniature railway, which attracted great interest. The political prerequisites for the railway construction did not exist until 1868 in the course of the Meiji restoration . In 1870, work began on the first line between Tokyo and Yokohama , which went into operation on June 12, 1872.

To modernize the country, the government hired numerous Western experts , mainly British in the railway sector, to pass on their knowledge. In 1878 the first graduates from an engineering school were commissioned to build the Kyōto - Ōtsu rail link ; two years later, the first line built under Japanese management was completed. Soon enough local skilled workers were available to replace the foreign ones. A significant exception was Richard Francis Trevithick , who helped build the locomotive industry until 1904. In Hokkaido , where from 1880 significant coal -Occurrence were opened, dominated American engineers and technology.

Due to a lack of money and high inflation, the construction of the railway made slow progress, which is why the government allowed the establishment of private railway companies. The first was the Nippon Tetsudō in 1881 . The state then limited itself to railway construction in central Japan. In 1888 the first railway line was opened on Shikoku , followed by the first on Kyūshū in 1889 . From 1901, a train journey over the entire length of the main island of Honshū was possible.

In 1892, parliament passed a Railway Construction Act that laid down binding routes that were to be built either by the state or by private individuals (Hokkaidō had its own Railway Construction Act four years later). While only British steam locomotives were imported in the first few years , American and German models were increasingly added from 1890 onwards. Passenger cars had been produced in Japan since 1875, the first locomotive from local production was built in 1893. The import share fell continuously and from 1912 Japanese companies produced almost all large steam locomotives themselves (with the exception of some imported models that were copied).

Nationalization of the most important private railways

Since the suppression of the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, in which the railroad played an important role, the Imperial Japanese Army has been one of its most important sponsors. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894/95, and in particular the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/05, reinforced the opinion that a uniform national rail network was necessary for efficient troop transport. Economic advantages were also promised. After Parliament passed the Railway Nationalization Act in March 1906, the 17 most important private railways went into state ownership by October 1907. The Railway Office, created in 1908, was subordinate to the Cabinet and was converted into the Railway Ministry in 1920 .

In 1887, the army suggested for the first time, the railways of Cape gauge (1,067 mm) standard gauge (1435 mm) switch tracks . For the time being, nothing happened and the army decided in 1898 to advocate nationalization instead. Gotō Shimpei , Director General of the Railway Authority , wanted to get the state to provide funding for the re-gauging of several main lines in 1911, but the project met with bitter resistance from the opposition around Hara Takashi , who preferred the expansion of the route network. Gotō made another attempt a few years later, but failed again in 1919 because of Hara, the then Prime Minister.

Branch lines, standardization and electrification

Private companies were largely restricted to short branches or cities. In the country there were a number of hand-operated trams that were powered by human muscle power, while extensive tram networks were built in the cities . In 1910 a law for the promotion of small railways came into force. Many of the routes that followed used the 762 mm gauge. As the locomotive industry was at full capacity, numerous small railroad locomotives were imported. Despite subsidies and low construction costs, many small railways soon found themselves in financial need and were replaced by buses from the 1920s.

In the meantime, all of the main lines established in 1892 had been built. The new railway construction law passed by parliament in 1922 comprised branch lines of over 10,000 km in length. It did not contain any specifications about their priority or binding completion dates, so that the construction sequence was subject to political influence. Although the gauging of the main lines had failed, as many advantages of the standard gauge as possible should be used. Clearance profile , track spacing , bridge specifications and other standards were standardized on this basis. Numerous steep sections also disappeared due to leveling and the construction of longer tunnels. Further improvements could be achieved through standardized wagons and locomotives.

In 1904, the Kōbu Tetsudō was the first railway company to switch a route from steam traction to electrical operation - an 11 km long section of the Chūō main line that passed into state ownership two years later. Initially, almost exclusively local transport routes or particularly steep mountain railways such as the section of the Shin'etsu main line over the Usui Pass were electrified . Tokyo Station , which opened in 1914 , was one of the most important infrastructure projects of the Taishō period and was accessible by electric trains from the start. The Yoshima Kleinbahn in Fukushima Prefecture first used diesel multiple units in 1921 ; the Ministry of Railways followed this example from 1929.

While the state was very reluctant to introduce electric traction, rapidly expanding private railways (the later “big 16” ) used this technology much more resolutely and thus promoted suburbanization . These companies tried to diversify as broadly as possible. A pioneering role played Kobayashi Ichizō , the director of Hankyū Dentetsu , who expanded the company by opening a central department store in Osaka as well as tourism and leisure facilities (e.g. the music theater group Takarazuka Revue and the film studio Tōhō ). His management methods were considered innovative and became generally accepted in the 1950s.

Situation in the Japanese colonies

With the expansion of the Japanese Empire , rail lines in the colonies were added. In 1895, China had to cede the island of Taiwan , where the first railway line had opened two years earlier. The Japanese government created a separate ministry for the Taiwanese railways. Several important routes were created, including a continuous connection along the west coast from Keelung via Taipei to Kaohsiung . Branch lines were mainly used to transport raw materials (see also: Taiwan under Japanese rule # railways ) .

Sakhalin was occupied in 1905 ; the southern half of the island became Japanese property with the Treaty of Portsmouth as Karafuto Prefecture . The army then built a railway line from Ōdomari ( Korsakow ) to Toyohara ( Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk ) in just two months . In 1907 the prefecture administration took over the business. Until the 1930s, routes with a total length of around 700 km were built.

When Korea (Japanese Chōsen ) became a Japanese protectorate in 1905, rail lines had only existed there for nine years. They were built mainly with Japanese capital and came under army administration in 1906. After the final annexation of Korea in 1910, they came under the Railway Office of the General Government of Japan. In contrast to the railways on Taiwan and Sakhalin, the Korean routes were mostly standard gauge. While the state was building the main lines, it left the construction of branch lines to private companies (see also: Rail transport in Chōsen ) .

In 1905 the southern part of the East China Railway in Manchuria also came under Japanese control. A year later, operations were transferred to the private South Manchurian Railway (Mantetsu). The existing lines built in Russian broad gauge were changed to the standard gauge common in China and Korea. The Mantetsu expanded the route network further and was also involved in the development of various branches of industry that exclusively served Japanese interests. The puppet state of Manchukuo , founded in 1932, created a "Manchurian State Railroad" in the north of the territory a year later, but this was under the full influence of the Mantetsu and Kwantung Army .

Railway operations during the Pacific War

In July 1937 the Pacific War broke out. All railway companies had to increase their freight transport performance significantly, but suffered from material bottlenecks. In 1939, the Ministry of Railways planned to build a standard gauge "new trunk line" (shinkansen) between Tokyo and Shimonoseki to facilitate freight traffic to the Asian mainland. Construction work began in September 1940, but the project had to be abandoned after a short time. From 1941, the railways almost had a transport monopoly, as petrol was no longer available for private vehicles. The construction of the Kammon Tunnel between the islands of Honshu and Kyushu, which began in 1936, was completed in July 1942.

During the war, the state deployed millions of slave labor in Japan and the occupied territories , mostly in the construction of railroad lines and other infrastructure projects. The working conditions were inhumane and are considered a war crime . Between 1939 and 1945 around 60,000 Korean forced laborers died in Japan alone , mostly of exhaustion and malnutrition. The number of dead forced laborers on the Korean peninsula and Manchuria is estimated at 270,000 to 810,000. From June 1942 to October 1943 the army had the Thailand-Burma railway built. She used 65,000 Australian, Dutch and British prisoners of war and more than 300,000 Southeast Asian slave labor. Around 94,000 civilians and 14,000 prisoners of war died during the construction of the 415 km long route.

The government pushed the construction of steam locomotives and allowed the overloading of freight wagons in order to further increase the transport capacity in freight traffic. On the other hand, it gradually restricted passenger traffic from 1942 onwards and temporarily shut down branch lines so that excess material could be used in other locations. Some private railways, whose lines were of high military value, were nationalized in 1943/44. In November 1943, the Ministry of Railways was merged into the new Ministry of Transport and Communication, which, in view of the worsening course of the war, was given supervision over all traffic and communication routes.

The Allied air raids on Japan began in April 1942 and caused great damage to the rail network, especially in the metropolitan areas. In Okinawa , it was completely destroyed in 1945 and later not rebuilt. Elsewhere, rail traffic almost came to a standstill because of the damage, lack of maintenance and staff shortages. Collisions and derailments increased and the systems were in poor condition. 4403 railroad workers died in air raids, while 1,494 passengers were killed or injured. Despite everything, trains continued to operate on August 15, 1945, the day of Japan's surrender .

Restructuring, Shinkansen, end of the steam locomotive

At the beginning of the occupation , the Department of Transportation took over the supervision of the railways under the instructions of the American occupation forces. The rail network was massively overloaded: while less than a third of the pre-war capacity was available, significantly more passengers had to be transported. At the same time, the repair work was slow and accidents often occurred. General Douglas MacArthur instructed the government in July 1948 to convert the previously directly managed state railways into a public company and justified this measure with the threat of infiltration by communist trade unionists. The Japanese State Railways (JNR) began operations on June 1, 1949.

In 1950 only 8% of the JNR route network was electrified and the government set itself the goal of converting the main routes to electrical operation as quickly as possible. The Tōkaidō main line , which at that time handled 24% of the total traffic volume, had the highest priority . The electrification of this line was completed in 1956. On September 26, 1954, the JNR railway ferry Tōya Maru sank between Honshū and Hokkaidō. The accident claimed 1,128 deaths and is considered to be a decisive factor in the planning of the Seikan tunnel under Tsugaru Street .

Since the Tōkaidō main line continued to reach its capacity limits due to the onset of the economic boom, JNR President Sogō Shinji energetically pushed forward the project of a standard-gauge high-speed line from 1958. It was financed, among other things, with a loan from the World Bank . The budget was massively exceeded: Sogō had deliberately set the original cost estimates far too low to gain approval at the political level. When the scandal was exposed in 1963, he drew the consequences and resigned. Notwithstanding this, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka was inaugurated on October 1, 1964 after a five-year construction period, with Japan taking over the global leadership role in rail technology.

In the 1960s, freight traffic on non-electrified routes continued to be handled to a significant extent by steam locomotives. The development of high-performance diesel locomotives was delayed, for which in particular the severe restrictions on the axle load on the Japanese Cape Gauge Network were responsible. The last passenger trains hauled by steam locomotives ran in 1975, for shunting freight trains they remained in use until 1976.

Structural problems and state railroad privatization

Based on the total volume of traffic, the private railway companies and the state railway together had a market share of 92% in passenger and 52% in freight in 1950. Due to the mass motorization (which started about a decade later in Japan than in Western Europe) this proportion fell continuously to 40 and 8% respectively in 1980. However, the traffic volume increased significantly overall and the JNR had great difficulty with the demand in to keep pace with the expanding metropolitan areas .

While the JNR could count on financial support from the state to expand its capacity, the private railways were largely on their own. The state imposed regulations on fares for them, but also refused subsidies, so that they were dependent on income from non-rail business areas. They mainly invested in expanding the stations so that longer trains could be used. Although public corporations planned large planned cities , new routes were initially largely not built, as the private railways could not expect any profit from them. That changed in 1972 when the state began subsidizing the construction of non-JNR railway lines through the Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation (JRCPC). The JRCPC also sponsored the construction of additional tracks and direct connections to underground lines. The road traffic authorities were responsible for replacing ground-level sections with dams and viaducts, as the freedom from crossings contributes to smooth and safe road traffic.

1964 was the last year in which the JNR made a profit. She tried in vain to return to profitability. For example, in 1976 it increased fares by 50%, which resulted in a marked shift to motorized individual transport and in rural areas led to numerous route closures. On the other hand, the unions protested against downsizing with long strikes . As the government continuously cut subsidies, the mountain of debt grew. Still, the JNR had to bow to political pressure and use loans to make large investments, including building more Shinkansen routes. To prevent the financial collapse of the JNR, the government set up the "Commission for the Rehabilitation of the Japanese State Railways" in 1983, which presented a comprehensive report two years later. On this basis, Parliament decided on April 1, 1987 to privatize the state-owned enterprise and split it up into seven independent companies of the JR Group .

Further development

In 1988, two islands received a permanent rail link to the main island of Honshū within one month: after a construction period of almost ten years, the Seto-Ōhashi Bridge to Shikoku was opened in March . In April, almost 24 years after the start of construction, the 53.85 km long Seikan tunnel to Hokkaidō was opened, which was then the longest railway tunnel in the world.

The JNR had amassed a mountain of debt of 37 trillion yen (approx. 455 billion German marks ). Only the three passenger transport companies on Honshū ( JR Central , JR East and JR West ) could be expected to operate profitably, while the four others ( JR Hokkaido , JR Kyushu , JR Shikoku and JR Freight ) could, at best , achieve a balanced operating result ran out of. The three companies on Honshū took over 31% of JNR's debts, a state rescue company carried the rest. The privatization has only been partially completed to date: while JR Central, JR East and JR West are highly profitable and their shares are freely traded on the stock exchange the other four companies are still indirectly owned by the state and rely on support through cross-subsidization .

The revision of the Railway Business Act in 2000 further liberalized rail traffic and increasingly led to the closure of smaller private railways or their replacement by bus lines. However, these closures are also due to the population decline in rural areas. To stop this trend, a law passed in 2007 gave local authorities the opportunity for the first time to support local transport networks and to introduce cross-company ticket offers. It is also now possible, as in Europe, to legally separate ownership of the railway facilities and the operation of trains.

The Tōhoku earthquake on March 11, 2011, the strongest ever recorded in Japan, together with the subsequent tsunami, caused great damage to the rail network. 325 km of railway lines and 23 stations were destroyed, seven trains derailed. JR East had to interrupt operations on almost all routes due to bent rails or torn down contact lines. While operations in the Tokyo area went back to normal after a few days, the repair of the Tōhoku Shinkansen took 49 days. Several routes on the Pacific coast were not rebuilt; instead, the route was paved and BRT systems were installed on it. The Jōban line , which was interrupted due to the Fukushima nuclear disaster , is expected to be open to traffic again in 2020.

Railway museums and nostalgia

The first Japanese Railway Museum was provisionally set up at Tokyo Station in 1921 and moved to Manseibashi Station (the starting point of the Chūō Main Line ) in 1936 . It remained the only museum of its kind during the pre-war period. Serious efforts to preserve historic rolling stock began in the 1950s. After three major museums opened in 1962, numerous more followed over the next few decades. Likewise, non-profit organizations were formed that take care of the maintenance of individual locomotives and wagons.

The largest railroad museums in the country which include Railway Museum Saitama in Saitama (joined 2007, the successor of the museum in Tokyo Manseibashi on), the Railway Museum Kyoto in Kyoto , the Ōme Railroad Park in Ōme which SCMaglev and Railway Park in Nagoya , the Mojiko Retro in Kitakyushu , the Keio Rail Land in Hino , the Tōbu Museum in Tokyo and the Municipal Museum of Otaru . Other objects from Japanese railway history can be found in the Meiji Mura open-air museum in Inuyama . There are also dozens of smaller museums of local importance. Numerous cultural assets relating to the history of the railway are protected as Japanese railway monuments.

Actual museum railways , the infrastructure of which is maintained for the purpose of allowing historical vehicles to run, are rare. These include the Usui-tōge Tetsudō Bunkamura , the Sagano Kankō Tetsudō , the Sakuradani Keiben Tetsudō and the Shuzenji Romney Railway . Far more frequent are special trips on routes that continue to serve normal passenger traffic. Well-known examples are the Ōigawa Main Line in Shizuoka Prefecture and the Yamaguchi Line in Yamaguchi Prefecture . The joyful trains ( ジ ョ イ フ ル ト レ イ ン , joifuru torein ) are also widespread . These are excursion trains that consist of specially converted cars. In some cases they are very luxurious or dedicated to a specific cultural theme.

See also

- List of Japanese Railway Companies

- List of railway lines in Japan

- List of former railway lines in Japan

- Traffic in Japan

literature

- Dan Free: Early Japanese Railways 1853-1914: Engineering Triumphs That Transformed Meiji-era Japan . Turtle Publishing, Clarendon 2014, ISBN 978-4-8053-1290-2 .

- East Japan Railway Culture Foundation (Ed.): A history of Japanese railways 1872-1999 . Shibuya 2000, ISBN 4-87513-089-9 .

- East Japan Railway Culture Foundation (Ed.): Japanese railway technology today . Shibuya 2001, ISBN 4-330-67201-4 .

Web links

- Kitayama Rail Pages (English)

- Description in the Encyclopedia of Railways by Victor von Röll , 1914

- Detailed map of the Japanese rail network from 1927 (University of Toronto)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Japan. In: The World Factbook . Central Intelligence Agency , 2015, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Takahiko Saito: Japanese Private Railway Companies and Their Business Diversification. (PDF, 2.0 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review 10th East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, January 1997, accessed on October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ John Calimente: Rail integrated communities in Tokyo . In: University of Minnesota (Ed.): The Journal of Transport and Land Use . tape 5 , no. 1 . Minneapolis 2012, p. 19-31 ( psu.edu [PDF]).

- ↑ Kenichi Shoji: Lessons from Japanese Experiences of Roles of Public and Private Sectors in Urban Transport. (PDF, 573 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review 29th East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, December 2001, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Oliver Mayer: More stagnation than hope: An overview of third-sector railways in rural Japan . In: College of Education Aichi (ed.): The Bulletin of Aichi University of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences . No. 66 . Kariya 2017, p. 135-144 ( handle.net ).

- ↑ MLIT (Ed.): Tetsudō Kyoku . Denkisha Kenkyūkai, Tokyo 2005, ISBN 4-88548-106-6 , p. 228 (Japanese).

- ^ English translation of the tetsudō-jigyō-hō (translation 2009 after last change in 2006) in the Japanese Law Translation Database of the Ministry of Justice

- ↑ 鉄 道 事業 法 , current text (last change in 2016) in the e-gov law database of the Sōmushō

- ^ Railway Business Act. (PDF, 388 kB) MLIT , December 4, 1986, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ↑ 大 正 十年 法律 第七 十六 号 軌道 法. elaws.e-gov.go.jp, accessed October 27, 2017 (Japanese).

- ^ Peter Semmens: High Speed in Japan: Shinkansen - The World's Busiest High-speed Railway . Platform 5 Publishing, Sheffield 1997, ISBN 1-872524-88-5 , pp. 1 .

- ↑ a b Yasu Oura, Yoshifumi Mochinaga, Hiroki Nagasawa: Railway Electric Power Feeding Systems. (PDF, 1.1 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review 16. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, June 1998, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Hiroshi Kubota: 鉄 道 工 学 ハ ン ド ブ ッ ク . Railway technology manual. Grand Prix, Chiyoda 1997, ISBN 4-87687-163-9 , pp. 148 .

- ↑ 鉄 道 に 関 す る 技術上 の 基準 を 定 め る 省 令. elaws.e-gov.go.jp, accessed October 27, 2017 (Japanese).

- ↑ This is why Japanese train drivers make strange pointing movements. watson.ch , August 26, 2018, accessed on August 26, 2018 .

- ↑ Types of trains in Japan. Travel Happy, 2016, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ Night trains. japan-guide.com, 2017, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Types of tickets. East Japan Railway Company, 2017, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Japan Rail Pass. JR Group, 2017, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Seishun 18 Kippu. japan-guide.com, 2017, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Annual report 2016. (PDF, 9.6 MB) Central Japan Railway Company, 2017, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ↑ 東 急電 鉄 、 「遅 延 証明書」 を ネ ッ ト 発 行 -JR 東 と 同時 開始 へ. Shibuya Keizai Shinbun, January 1, 2007, accessed October 27, 2017 (Japanese).

- ↑ Oliver Mayer: Learning from Japan means learning quality. (PDF, 82 kB) In: The Passenger. Pro Bahn , February 2004, accessed on October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Subway pusher of Japan. Amusing Planet, April 6, 2017, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Anne Schnepfen: The unpunctual are humiliated and punished. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , April 29, 2005, accessed on October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Kiyohito Utsunomiya: When will Japan Choose Light Rail Transit? (PDF, 714 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review 38th East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, March 2004, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ^ Utsunomiya light rail line breaks ground. Metro Report, May 30, 2018, accessed November 28, 2018 .

- ↑ 会 社 概要. Tōkyō Monorail , 2017, accessed October 27, 2017 (Japanese).

- ↑ a b Freight Rail Overview & Freight Management in Japan. (PDF, 3.9 MB) Japan Freight Railway Company, 2015, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ^ A b Kazushige Terada: Railways in Japan — Public & Private Sectors. (PDF, 424 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review 27th East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, June 2001, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ^ Japan firms shifting to trains to move freight amid dearth of new truckers. The Japan Times , January 17, 2017, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ Katsuji Iwasa: Rail Freight in Japan — The Situation Today and Challenges for Tomorrow. (PDF, 1.7 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review 26th East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, February 2001, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ^ Perry Expedition and the Opening of Japan (Part 9): The Treaty of Kanagawa. Exploring History, January 17, 2017, accessed April 30, 2016 .

- ^ A b c Eiichi Aoki: Japanese Railway History: Dawn of Japanese Railways. (PDF, 629 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, March 1994, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ A b Eiichi Aoki: Japanese Railway History: Expansion of Railway Network. (PDF, 1.5 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, June 1994, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ Eiichi Aoki: Japanese Railway History: Growth of Independent Technologiy. (PDF, 1.5 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, October 1994, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Mitsuhide Imashiro: Japanese Railway History: Nationalization of Railways and Dispute over Reconstruction to Standard Gauge. (PDF, 247 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, March 1995, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ A b c Eiichi Aoki: Japanese Railway History: Construction of Local Railways. (PDF, 615 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, July 1995, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ A b Shinichi Kato: Japanese Railway History: Upgrading Narrow Gauge. (PDF, 1.7 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, December 1995, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ Teruo Kobayashi: Progress of Electric Railways in Japan. (PDF, 2.1 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, December 2005, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ Shinichi Kato: Japanese Railway History: Development of Large Cities and Progress in Railway Transportation. (PDF, 252 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, September 1996, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ A b c Yasuo Wakuda: Japanese Railway History: Wartime Railways and Transport Policies. (PDF, 817 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, November 1996, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ RJ Rummel: Statistics of Japanese Democide: Estimates, Calculations, and Sources. University of Virginia, Rutgers University, 1997, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ GF Kershaw: Tracks of Death: The Burma-Siam Railway . Book Guild Publishing, Leicester 1992, ISBN 0-86332-736-2 .

- ↑ a b c Mitsuhide Imashiro: Japanese Railway History: Dawn of Japanese National Railways. (PDF, 1.6 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, January 1997, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ A b c Yasuo Wakuda: Japanese Railway History: Railway Modernization and Shinkansen. (PDF, 1.7 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, April 1997, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ Roderick A. Smith: The Japanese Shinkansen . In: The Journal of Transport History . Volume 24, No. 2 edition. Imperial College, London 2003, pp. 222-236 .

- ↑ a b Mitsuhide Imashiro: Japanese Railway History: Changes in Japan's Transport Market and JNR Privatization. (PDF, 784 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, September 1997, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ Yasuo Wakuda: Japanese Railway History: Improvement of Urban Railways. (PDF, 900 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, June 1997, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Yoshitaka Fukui: Twenty Years After. (PDF, 131 kB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, March 2008, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Kiyohito Utsunomiya: Recent Developments in Local Railways in Japan. (PDF, 2.1 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, October 2016, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ^ Elisabeth Fischer: How Japan's Rail Network Survived the Earthquake. railway-technology.com, June 28, 2011, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Fukushima: Joban railway line fully open from 2020. Nuclear Forum, August 2, 2017, accessed October 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Takahiko Saito: The Preservation of Railway Heritage in Japan: An Outline History and General View. (PDF, 1.1 MB) In: Japan Railway & Transport Review 30. East Japan Railway Culture Foundation, March 2002, accessed on October 27, 2017 (English).

- ^ Japanese Railway Museums. kisekigo.com, accessed October 27, 2017 .