Architecture in Heilbronn

The architecture in Heilbronn ( Baden-Württemberg ) ranges from the Middle Ages to the 21st century. Numerous typical buildings from different epochs of architectural history have been preserved, but much has been lost.

Examples of medieval architecture in Heilbronn are a Romanesque chapel of the Teutonic Order Minster of St. Peter and Paul and the Gothic hall choir of the Kilian's Church . In modern times , the west tower of Heilbronn's Kilian Church was built in the Renaissance style. The splendor of the baroque is reflected in the facade of the Great Deutschhof . When the war of 1870/71 was won , the economy experienced an upswing and a large number of buildings in the style of historicism were built during the founding period . In the modern age from 1900, English country house architecture was evident in Heilbronn. Employees' houses of the Knorr company were built in homeland security style based on the example of country house architecture . The most important building from the period before the First World War was in Art Nouveau style built Old Theater . For the architecture of modernism in the period thereafter, buildings in the style of functionalism and expressionism stand .

During the air raid on Heilbronn on December 4, 1944, the city was almost completely destroyed. The architecture of the post-war period was shaped by architecture from the pre-war period such as the Heimatschutz style and organic building . The reconstruction of the former old town of Heilbronn took place with three- to four- story plastered buildings with saddle roofs based on plans by H. Volkart , with which the Baroque style typical of the Stuttgart Schmitthenner School was resumed. According to Schweizer, Volkarts' urban planning draft is "one of the best in the country" and "this work [would] represent the missing 1st prize". Also P. Schmitthenner and J. Hoffmann decorated buildings in the former Old Town in the style of the Stuttgart school or home style. Parallel to the reconstruction, the so-called “second destruction” of Heilbronn took place, in which buildings that had survived the war were removed, such as the Heilbronner Friedenskirche and the Alte Harmonie .

The 1970s were shaped by brutalist architecture. The tallest commercial building was completed in 1971 with the seventeen-story shopping building. The Rosenberg high-rise , a twenty-storey residential high-rise, was built in the "Rosenberg" building area when it was opened in 1972/1973 . In the 1970s, the old public swimming pool on Wollhausplatz, the old theater at the north end of the avenue and the Villa Rümelin were also demolished. According to the architectural historian Hennze, they were silent witnesses who “could still be made to speak”. With the destruction of the stone witnesses, they are condemned to silence.

The Heilbronn cityscape is determined today by the postmodernism of the 1980s and 1990s and contemporary architecture of the 21st century.

Architectural history

Pre-Romanesque

In 741 the Franconian caretaker Karlmann gave a St. Michael's basilica to the diocese of Würzburg . According to older research, the Michaelsbasilika was a predecessor of the Teutonic Order Church in Heilbronn . In the years 1994/95, during renovation work in the south wall of the choir tower chapel, brickwork and under the side chapel remains of limestone foundations were found, which must be even older than the current structure. In the extension of the south wall of the tower, foundation walls made of limestone were found, and the walls of a 40 cm deep, 212 cm wide and 212 cm high niche at the apex, made of limestone and taking up two thirds of the tower wall thickness. This limestone extends to the middle of the first floor on the southeast side of the Romanesque choir tower, while the rest of the building is made of sandstone. However, the finds remained undated and their origins remain open.

Romanesque

In the southern part of Heilbronn settlement evidence from the 11th / 12th centuries could be found. Century can be proven, which are attributed to the Hanbach settlement . Parts Hanbachs became the property of the German Order of coming across that there 1225 built a Deutschordenshof. When the Teutonic Lords built a Romanesque Lady Chapel in 1230 , they came across the remains of a predecessor building made of limestone masonry, which they included as a useful preliminary contribution to the construction of their late Romanesque sandstone choir tower. The Romanesque altar from 1250 in the cross-vaulted choir tower chapel is remarkable . The strip on which the altar plate rests consists of a massive sarcophagus-like block. The parapets of the block show quadrilateral panels . At the corners and in the middle of the long side of the altar substructure there are columns with different capitals and connected by a common palmette frieze . In the corners of the tower choir there are four late Romanesque half-columns, each of which forms a calyx-bud capital at the top . Another architectural decoration of the capital was a decorated with human heads fighter stone placed. The cross vault decorated with a keystone rests on these columns . The keystone with its four-leaf quatrefoil indicates the relationship with the Johanniter Church in Boxberg-Wölchingen and the Bamberg Cathedral . The Romanesque round arch shows the old painting in black and red, as was common in the Romanesque period. Small choir tower churches with the character of a fortified church represent the most important evidence of Romanesque sacred architecture, although mostly only the choir towers of the churches have survived.

Gothic

Due to the Neckar privilege received on August 27, 1333 and the imperial city dignity of 1371, the city achieved great wealth, which was particularly reflected in the architecture. In the 15th century, numerous prominent foreign architects such as Hans von Mingolsheim , the Stuttgart Aberlin Jörg and Anton Pilgram from Vienna were entrusted with important buildings. In 1447 the council commissioned Hans von Mingolsheim, who had previously worked in Speyer and Strasbourg, to build the Carmelite monastery in the Gothic style. Between 1480 and 1487, Aberlin Jörg built the late Gothic three-nave hall choir of Kilian's Church . The origin of this hall choir indicates the relationship to the Bauhütte in Vienna and the collaboration of Anton Pilgram.

Gothic:

south portal of Kilian's Church

Renaissance

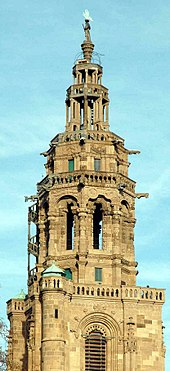

The expansion of the port with a wheel crane in 1515 brought another economic boom, which enabled the construction of the first Renaissance tower north of the Alps and the town hall with an art clock. In 1513, for example, Hans Schweiner created the tower of Kilian's Church . The architecture of the Renaissance continued in the design of the town hall between 1579 and 1583 by Hans Kurz and Isaak Habrecht . Hans Kurz was one of the most important builders of the Renaissance in Heilbronn. He also built Imlin's house . In the years 1598 to 1600 the meat house was built according to the plans of Hans Stefan on behalf of the council , whereby Jakob Müller worked as a sculptor in the design of the figures. The most important examples of the Renaissance in Heilbronn are the church tower of Kilian's Church , the old town hall , the Cäcilienbrunnenhaus and the Fleischhaus. The Dreifaltigkeitskirche , the former Katharinenspitalkirche , which emerged from an older chapel in 1483, became Protestant during the Reformation and was rebuilt in the Renaissance style after a fire in 1624 with an elaborate volute gable and portal, has been lost.

Old Town Hall , 1911

Baroque

In the second half of the 18th century, the city experienced a new cultural and economic boom as the main staging area for trade between the Rhine and the Danube area. Numerous buildings in the Baroque style were built , such as the Hafenmarktturm , which Johann Georg Meyer from Strasbourg created in 1730. For the Baroque epoch between 1600 and 1780, courtly pleasure architecture and the depiction of pomp, luxury and splendor in the architecture of the Catholic Church were characteristic. An example of the splendor of the church is the Teutonic Order Cathedral, which was made baroque by the brothers Franz and Johann Michael Keller and A. Colomba . JM Keller and his brother Franz were the pioneers of Balthasar Neumann and Fischer von Erlach . Examples of the representative, courtly architecture of the Teutonic Lords in Heilbronn include the baroque summer residence in Sontheim, which has been in Sontheim since 1688, and the large Deutschhof built according to plans by Wilhelm Heinrich Behringer in the high baroque style, which was a considerable size by Heilbronn standards and the cityscape continues to shape today. The 24-axis bent west facade and the facade of the adjoining eight-axis south wing were structured with Ionic pilasters , gables and portals with pillars.

Rococo

Examples of buildings in the Rococo style were the unicorn pharmacy , the Kraichgau archive and the old city archive . The shooting house has been preserved .

classicism

The playful style of the Baroque has been criticized as arbitrary. That is why the builders and architects of the 18th century wanted an architecture that was sober. This new architecture should be inspired by the spirit of the Enlightenment . Archaeological and architectural evidence in Italy, Greece and the Middle East were considered to be models for the new epoch of classicism . Heilbronn was a leader in the field of secular building in the classicism style. As early as the beginning of the 19th century, several stately palaces document the prosperity of the city of Heilbronn, such as the Rauch'sche Palais , which is considered an early example of classicism in Heilbronn and was restored in the Renaissance style by Robert von Reinhardt in 1877 and 1878 was. Other examples of classicism in Heilbronn are the Villa Mertz and the Villa Rauch .

Round arch style

The architecture in the transition from classicism to historicism was characterized by the so-called round arch style, an early phase of historicism that combined neo-Romanesque and classicist elements into a harmonious whole. The Wilhelmsbau with its arched windows in the central projectile and the old Heilbronn train station are examples of the arched style typical of the 1840s. The parish church of St. Alban in Kirchhausen, built by Gottlob Georg Barth , also documents the arched style.

historicism

In the architecture of historicism , a distinction from classicism was hardly recognizable. Both styles had taken details of architecture from bygone eras and mixed them with one another. The historicism of the 19th century in Heilbronn was characterized by the fact that prominent foreign artists received important building contracts. Gottlob Georg Barth from Stuttgart designed the first urban expansion plan for the city of Heilbronn in 1808, in 1829 Karl Ludwig von Zanth designed the Heilbronn main customs office, and in 1834 Gottlob Georg Barth created an expansion plan for the city. In 1835 the city tried to hire the prominent architect Ludwig Friedrich Gaab as the city architect.

Economic and historical milestones were the opening of the Wilhelmskanal , the construction of the suburbs under Millas and the Riesenstrasse under Professor Baumeister . In the same year, Karl Ludwig von Zanth built the Goppelsche House at Fleiner Tor with paintings in the Pompeian style . Although Ludwig Friedrich Gaab could not be won as a city architect, he built the main post office on the Neckar in the middle of the century . From the founding period onwards, numerous prominent foreign artists were entrusted with high-quality works: Robert von Reinhardt from Stuttgart built the Alte Harmonie as well as the Villa Adelmann , the Villa Faißt and the Villa Seelig in 1876 ; the Stuttgart city architect Adolf Wolff designed the old synagogue from 1877 , The district building inspector Theodor von Landauer , who was born in Heilbronn, built the cell prison in his hometown, the Berliners Johannes Vollmer and Heinrich Jassoy designed the Friedenskirche and the Villa Carl Knorr from 1897 . Further examples of historicism architecture in Heilbronn are the Villa Dittmar by Hermann Maute , the Schweinsberg Tower by Ludwig Eisenlohr and Carl Weigle and the villas Mayer , Villa Hagenmayer and Cluss by Theodor Moosbrugger .

View of the Villa Schliz , Hohe Strasse

Modern from 1900

Werkbund

The era of historicism in Heilbronn slowly came to an end and gave way to a new, modern conception of building that had emerged shortly before the outbreak of the First World War . As early as 1900, the chairman of the Deutscher Werkbund, Peter Bruckmann, demanded that no architecture should be designed in the medieval style. The architecture of the past and that of the future represented two opposing positions that Bruckmann tried to bridge together with Karl Luckscheiter . At the industrial, art and trade exhibition in Heilbronn, historical towers and gables could only be seen in the form of wooden backdrops. Bruckmann demanded that architecture should be a mirror image of modern commercial and industrial activity and rejected the use of historical styles in architecture. In 1907 Peter Bruckmann founded the Deutscher Werkbund together with Hermann Muthesius , Theodor Fischer and Richard Riemerschmid , which attached great importance to quality and good form. Both Hermann Muthesius and Theodor Fischer are considered pioneers of modern architecture. This new concept was also noticeable in the architecture of Heilbronn. Examples of this new era, in which building was still moderately modern, are:

Villa Pielenz

With the construction of the Villa Pielenz , the English country house architecture was introduced in Heilbronn. This was represented by Hermann Muthesius , who broke with historicism and sought the reference to the English country house architecture. With the adaptation of the country house architecture from England, Muthesius made the so-called Heimatstil known in Germany. Examples of the Heimatstil in Heilbronn are the five houses built by Theodor Moosbrugger on the north side of Heilbronn's Liebigstrasse. The Heimatstil, which emerged after 1900, had a reformist claim , was directed against the historicizing building methods of the late 19th century and required an architecture that was simple, technically solid and typical of the landscape. Feature is the gable wall covered with shingles blinded is.

Due to its high-quality architecture, the old theater was of supraregional importance and developed from Romanticism in the sense of a national movement . The appearance of the building mainly took up local building traditions, such as the forms of the Kilian tower and the town hall , and developed these traditions further in free design. The old theater "seeks connection to the building traditions of our country, which are not further developed with historical concern, but with free impartiality" . The theater was considered to be an “important architectural work” by Theodor Fischer , who, as chairman of the Deutscher Werkbund after its founding, promoted reform architecture ( “[...] historicizing motifs freely associating, but different from the strictly historicizing architecture [...]” ). This is why the Heilbronn theater building mainly took up local building traditions, such as the architecture of the so-called “Heilbronn Renaissance” . This epoch of German building history was briefly ended by the First World War and the poor economic situation that followed. Both public and private construction activity ended in 1914. The theater building is described as “probably the most important building” of architectural modernism before the First World War in Heilbronn. Due to its architectural quality, it was regarded as a "qualitatively supra-regional building" .

- Sculptures at the Old Theater

Half column with decor

- Sculptures on the tower of Kilian's Church

Half column with decor

Art Nouveau

On October 19, 1974 Werner Heim presented a list of 60 Heilbronn Art Nouveau buildings. The occasion was the demolition of the two "important Art Nouveau buildings", the villas Rümelin , Alexanderstraße 44 and Pfleiderer , Lerchenstraße 79. He intended to hand this list over to the building authorities with the aim of opening the historical museum before the buildings were demolished to inform.

On December 7, 1974, the master stonemason and sculptor Franz Hamerla showed his exhibition “Art Nouveau Houses in Heilbronn”. In addition to Villa Pfleiderer, this also included Villa Rümelin. Robert Koch, who had taken 30 photographs, intended to compile a catalog of the buildings, most of which had already been demolished.

Existing examples of Art Nouveau are Villa Schliz , the semi-detached house at Südstrasse 129, 131 , House Cäcilienstraße 58 , House Kernerstraße 60 , House Rosskampfstraße 4 . A characteristic of Art Nouveau is the "relief-like ornamentation of a geometrical kind".

Female bust Sigilgaita on the front gable of Villa Schliz

Barasch department store , design by architect A. Braunwald Heilbronn

Functionalism and Expressionism

- functionalism

The moderate modernity from the prewar period contrasted with the avant-garde architecture of the modern age from 1920, which rejected an excess of historicity and turned away from the architecture of the prewar period. Until the mid-1920s, the then mayor and architect Emil Beutinger was able to promote the expansion of the Neckar as a major shipping route. In 1926 eleven barrages were built. These buildings, described as functional, striking concrete structures, were erected in the functionalism style by Paul Bonatz . Paul Bonatz also took up the modern architecture of functionalism with the design of the port market tower in 1929 and 1936, when he created the war memorial there , a memorial for the dead of the First World War. Karl Elsäßer took the architecture of Paul Bonatz as a model when he designed the Kaiser's coffee shop in 1938 . Functionalism was a style of modern architecture that derived the external shape of the building from its function.

- expressionism

Peter Bruckmann from Heilbronn was once again one of the driving forces behind the Cologne Werkbund exhibition with the Weissenhof model estate in Stuttgart in 1927. Works from the New Building by Gropius , Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier were on view there. Walter Gropius (1883–1969) was a pioneer of the Weimar Bauhaus in the 1920s. He created the Dammerstock residential project on the southwestern edge of Karlsruhe , where arcade houses were also presented, and in 1930 a residential complex in Berlin-Siemensstadt. Based on these models, Ludwig Knortz designed the arcade house in the style of brick expressionism in Heilbronner Kornacher Strasse.

Other examples of Expressionism in Heilbronn are Haus Bohl , Haus Villmatstrasse 17 and the Böckinger water tower . Another example of Expressionism was the Augustine Church by Hans Herkommer , which was destroyed in World War II.

Laubenganghaus Heilbronn Portal Brick Expressionism

Homeland Security Architecture and Organic Architecture

During the air raid on Heilbronn on December 4, 1944, the city was almost completely destroyed. The architecture of the post-war period was characterized by the resumption of the traditional Heimat style as well as the organic building from the pre-war period. Christhard Schrenk, director of the Heilbronn City Archives, describes the architectural style of the early 1950s as a restoration , in which one remembered the good continuities from the prewar period, which many saw as a measure of normality and which had to be regained.

Heimatstil (Heimatschutzstil)

The reconstruction was characterized by the continuation of the conservative and traditional homeland style. This was due to the fact that only the Heimatstil did justice to the desire for a historicizing reconstruction. This was introduced in Germany by Hermann Muthesius in 1905 and took into account the conservative and reconstructive concept of reconstruction.

- Villa Rauch and Nikolaikirche (traditional reconstructions)

An important representative of the Heimat style in the post-war period was Hannes Mayer , who reconstructed the destroyed sacred buildings in the Heimat style. For example, Mayer created a historicizing reconstruction plan for the Nikolai Church in Heilbronn . But the reconstruction of destroyed residential buildings also followed the Heimat style. A typical example of this is the traditional reconstruction of the Villa Rauch , which was rebuilt in a reduced form by Adolf Braunwald , as well as the house at Herbststrasse No. 8 and the house at Allee 18 .

- Dresdner bank building and Jägerhaus (new or reconstruction in the local style)

Another representative of the Heimat style in the post-war period was the Stuttgart architecture teacher Paul Schmitthenner , a pioneer of conservative modernism, who built the Dresden bank building in 1952 and 1954 . The interior of the Wüba building , redesigned by Julius Hoffmann in a baroque style, is also an example of the early phase of reconstruction in the post-war period in Württemberg, which was characterized by the style of Paul Schmitthenner's Stuttgart school. An example of the domestic architecture of Schmitthenner school that was decisive for the second half of the 1940s in Württemberg after plans by Ludwig Hilmar cress built factory villa of Kurt Scheuerle. Paul Schmitthenner was of the opinion that economical building, because of the hardship and poverty in the post-war period, should not be confused with poor building. The essence of art is to create something artistically perfect even with few resources. The tradition-oriented style, which was based on the country house architecture of the Heimat style, also shaped the renovation of the Jägerhaus and was also decisive for the construction of the former Bierstorfer furniture store.

Organic building

The late 1950s were also shaped by the afterlife of organic building from the 1920s. Organic building is characterized by lively and color-affirming patterns. Examples of this are the color mosaics by Blasius Spreng on the town hall extension , which was already shown in the organic building style at the Stuttgart Liederhalle . Blasius Spreng not only adorned the pillars and parapets of the balconies of the town hall, the entire floor of the courtyard was equipped with a mosaic, so that it is also called the "jewelry courtyard".

- Schmuckhof

Town hall fountain with marble from Portugal ( Estremoz , Borba , Vila Viçosa ). Cladding on the ground floor with Mooser shell limestone panels

Three steps lead through the open hall from the market square to the jewelery courtyard, which has a mosaic floor by Blasius Spreng. The upper floors were clad with Schillkalk from Tengen .

The mosaic technique was used again in the 1950s. In 1958 Walter Maisak designed the mosaic picture Port and Industry in Heilbronn from the post-war period in the cash desk of the Kreissparkasse Heilbronn , with which he describes the reconstruction of the city. Crane, ship, house and bridge are the subject of the picture. In the same year he created the wall object Robert Mayer - Conservation of Energy . An abstract person symbolizes the energy force, which is converted into heat and represents a flame striving upwards. Wheels symbolize the warmth converted into motion. Peter Jakob Schober made a colorful metal relief from silicate paint and wrought iron for Heilbronn main station :. Traveling by train - Heilbronn and the world . Kilian's Church , grapes and industry symbolize Heilbronn and water, railway signs, sun, guitar and bridge symbolize the world. He also executed an abstract mural in the small hall of the Heilbronner Festhalle Harmonie in smooth spatula. The wall design in the small hall was one of the few non-representational works by the artist. Hans Epple worked with a combination of quarry stone mosaic and wrought iron work. His work Aufstrebende Formen from 1957 on the pavilion of the Gustav-von-Schmoller-Schule shows rows of gray and white natural stone on the one hand and colorful and irregular mosaic stones on the other. A metal mesh, which depicts several abstract hexagons as a motif , emphasizes the contours of the mosaic stones.

Facade design of the pavilion of the Gustav-von-Schmoller-Schule Heilbronn (Hans Epple)

1958 by Walter Maisak : Memorial picture to Robert Mayer

Peter Jakob Schober : Unicorn at the unicorn pharmacy

Peter Jakob Schober : Cup of coffee at the house of the former Kohout coffee roastery

Werner Holzbächer : Banister in the Kilian's Church in Heilbronn

There are many examples of the architecture of the 1950s in Heilbronn: Emil Burkhardt & Paul Barth designed the Neckar power station for the city of Heilbronn in 1955/1956 , Hellmut Kasel designed the Heilbronn main station in 1958, and Peter Salzbrenner built the Theodor-Heuss from 1956 to 1958 -Gymnasium , whereby his work is compared with buildings by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe . Stuber & Erich K. Hess built the Gustav von Schmoller School in 1960 , Rudolf Gabel built the town hall extension between 1957 and 1959 , Otmar Schär built the Einhorn pharmacy , Gustav Ernst Kistenmacher designed the Heilbronn Aukirche from 1958 . Other examples of 1950s architecture in Heilbronn are the Barthel department store by Willi Ulmer & Mühleisen and the Karl Kost furniture store by Hans Paul Schmohl & Karl Mogler from Böckingen.

Béton brut / brutalism / exposed concrete

A work in exposed concrete ( French : Béton brut : exposed concrete) is the Harmonie , inaugurated on November 29, 1958 with a ceremony , whereby Alfred Bühler designed the harmony facade with a facade relief in concrete for an artist fee of 4,000 DM.

"[...] Old photos document that the relief was not applied, but was created during the construction of the building, ie when the cladding was made"

Other buildings made of exposed concrete are the Catholic parish center St. Peter and Paul in Metzgergasse, inaugurated on January 25, 1964, and the Heilbronner Kreuzkirche , which was designed by R. Krauter and Fritz Holl and inaugurated on December 6, 1964 by Regional Bishop Erich Eichele. In addition, in 1966 the Lange Stall was a “striking” residential and commercial building in exposed concrete at the Sülmertor station, based on designs by the French architect Renaud de Girondon. Then the Heilbronn Wartbergkirche , which was completed in 1967 according to plans by Rudolf Gabel. Likewise the Pauluskirche, consecrated on December 9th 1973 . Other buildings with exposed concrete are the Frankenbacher Johanneskirche, inaugurated on December 22, 1974, as well as the Biberacher Böllingertalhalle and the Kirchhausen Teutonic Order Hall . In addition, the Horkheim weir , which was inaugurated on December 12, 1975 .

Kreuzkirche am Hohrain 2

Wartberg Church in Schüblerstraße 6

Pauluskirche at Karlstrasse 33

In the 1970s, the number of buildings built in a short period of time increased. Usually concrete high-rise buildings were built. Examples of this are the Helmut and Ernst Schaal shopping center as well as the Wollhauszentrum .

Postmodernism and Deconstructivism (1980 / 1990s)

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Heilbronn cityscape was shaped by postmodern architecture and deconstructivism . Examples are the Käthchenhof (postmodern) and the Hafenmarktpassage (deconstructivism).

Postmodernism turned against modernism and is an architecture that recalls historical models and roots. The cityscape plan ("Trieb-Plan") created by the Stuttgart city planner and architect Michael Trieb should see the " building and facade types that were created during the reconstruction ... as a design basis for further development" in order to understand the "characteristics of the rebuilt Heilbronn" to obtain. On December 17, 1987, the Heilbronn municipal council decided on the “Trieb Plan”. Gaps in the old town should be closed with buildings that have typical features of the Heilbronn urban architecture of the reconstruction.

The "Leinbach-Passage" shopping center was laid out in Neckargartach, and the Biberach parish church of St. Cornelius and Cyprian was inaugurated in 1985. In 1986/87 the “Käthchenhof” shopping arcade was built on the former Fuchs site. The Bergdoll house (Kilianscafé) was built on the corner of Kaiserstraße and Kiliansplatz. The Haux clothing store was built on Kaiserstrasse with a sandstone facade, arcade arches and bay windows. The Protestant Dietrich Bonhoeffer Church was inaugurated in Kirchhausen on September 21, 1986. On November 24, 1989, the new post office was opened on Bahnhofstrasse.

The Hafenmarktpassage, designed by Keller + Eckert in 1991, is based on the Hysolar-Haus on the campus of the University in Stuttgart-Vaihingen , which was designed by Günter Behnisch in the style of deconstructivism.

Contemporary architecture of the 21st century

Contemporary architecture is shaped by architects born in the 1940s and 1950s. Ulrich Bechler and Gerd Krummlauf designed the K3 in 2000 and the Neckar Tower in 2002 . In 2008 Matthias Müller designed the Kaiser's Tower, Gottlieb-Daimler-Straße 9, Bernd Zimmermann designed the roofed schoolyard of the Helene-Lange-Realschule in 2002 and in 2005 managed the facade renovation of the Mönchsee-Gymnasium. Franz-Josef Mattes - Sekiguchi Partner expanded the sports hall and classrooms of the Gerhart-Hauptmann-Schule in Heilbronn and designed the cloister courtyard .

Prominent foreign architects were also commissioned. Otto Steidle from Munich built the Neckarterrassen in 2003. In 2002, Auer, Weber and Partners from Stuttgart designed the roofing of the station forecourt. In March 2008, the Stadtgalerie or ECE shopping center, built according to plans by ECE architect B. Hillrichs, was opened with a black south wall with long strips of light and a glass structure facing the Deutschhof. BDA boss Matthias Müller calls the building “UFO” and says that the new building is “a foreign body in terms of urban planning” and that it “goes beyond any scale”. He hopes that the city gallery "does not [...] set new standards". He qualifies the building as "bad urban development that has absolutely nothing to do with Heilbronn". Building mayor Wilfried Hajek sees a need for subsequent revision of the facade at the entrance to the arcade in the west towards Schöntaler Gasse: "This should actually be done". According to another opinion, the black south wall is supposed to quote the Berlin Jewish Museum by Daniel Libeskind , while the facade with the colored glass windows cites works by Sauerbruch Hutton . The green exterior is reminiscent of the arched, green patinated copper domes of the old Heilbronn synagogue.

Loss of architecture

Architecture damaged during the war often fell victim to the forces of nature such as storms, rain and cold in the post-war period. Decisions of the building committee of the local council allowed in individual cases to remove the remaining ruins and to reuse their sandstones for the reconstruction of destroyed buildings. On November 19, 1948, the police headquarters had to publicly announce that the unauthorized removal of stones, wood and other property from the rubble of the destroyed buildings was to be assessed as theft. After the rubble removal had come to an end, the civil engineering department no longer left sandstone remains to private individuals, but exclusively to the public sector for the construction of public buildings. However, architecture reconstructed in the post-war period was later destroyed a second time, this time for good, by demolition or demolition. The reason for this was that many buildings were just architecture from the day before yesterday and that this was therefore an obstacle to the present and the future. Consequently, the structures had to be demolished. Not only did historical architecture get lost, but also the identification of Heilbronn citizens with their home history.

See also

Web links

swell

literature

- Marianne Dumitrache / Simon M. Haag: Archaeological city cadastre Baden-Württemberg . Volume 8: Heilbronn. Landesdenkmalamt Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-927714-51-8 .

- Roland Feitenhansl: Heilbronn railway station - its reception building from 1848, 1874 and 1958 . DGEG Medien, Hövelhof 2003, ISBN 3-937189-01-7 .

- Julius Fekete: Art and cultural monuments in the city and district of Heilbronn . Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-8062-1662-2 .

- Julius Fekete among other things: Monument topography Baden-Württemberg Volume I.5 Stadtkreis Heilbronn . Edition Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1988-3 .

- Hans Franke : History and Fate of the Jews in Heilbronn. From the Middle Ages to the time of the National Socialist persecution (1050–1945). Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1963, ISBN 3-928990-04-7 ( PDF, 1.2 MB ).

- Werner Heim, Helmut Schmolz: Archive and Museum of the City of Heilbronn in the Deutschhof Cultural Center. Their tasks and their history. For the inauguration of the III. Construction phase Deutschhof on March 12, 1977 (Small series of publications from the Heilbronn City Archives 9), Heilbronn 1977.

- Catholic parish of St. Peter and Paul, Heilbronn (ed.): Deutschordensmünster St. Peter and Paul Heilbronn . Kunstverlag Josef Fink in Lindenberg, 2000, p. 6 f., ISBN 3-933784-84-0 .

- Hans Koepf : The Heilbronner Kilianskirche and its masters . City of Heilbronn, City Archives 1961 (publications of the City Archives of Heilbronn, issue 6).

- Bernhard Lattner, Joachim Hennze: Silent contemporary witnesses. 500 years of Heilbronn architecture . Edition Lattner, Heilbronn 2005, ISBN 3-9807729-6-9 .

- Bernhard Lattner, Joachim Hennze: Heilbronn architecture of the 21st century . Edition Lattner, Heilbron 2019, ISBN 978-3-947420-14-8

- Rudolf Lückmann: Renovation of the Teutonic Order Minster in Heilbronn . In: Catholic parish of St. Peter and Paul, Heilbronn (ed.): The German Order Minster of St. Peter and Paul Heilbronn . 1995, (Festschrift on the renovation 1994/95 and the consecration of the altar on July 2, 1995), pp. 11–28.

- Max Georg Mayer: Discoveries during the renovation work on the Teutonic Minster St. Peter and Paul in Heilbronn . In: Catholic parish of St. Peter and Paul, Heilbronn (ed.): The German Order Minster of St. Peter and Paul Heilbronn . 1995, Festschrift on the renovation 1994/95 and the consecration of the altar on July 2, 1995, pp. 29–32.

- Andreas Pfeiffer (Ed.): Heilbronn and the art of the 50s. The art scene in Heilbronn in the 1950s. Situations from everyday life, traffic and architecture in Heilbronn in the 50s . Harwalik, Reutlingen 1993, ISBN 3-921638-43-7 (Heilbronner museum catalog . 43rd series Städtische Galerie)

- Alexander Renz / Susanne Schlösser: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VI: 1945-1951. Heilbronn 1995.

- Alexander Renz / Susanne Schlösser: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VII: 1952-1957. Heilbronn 1996.

- Uwe Jacobi: Heilbronn as it was . Droste, Düsseldorf 1987, ISBN 3-7700-0746-8 .

- Uwe Jacobi: That was the 20th century in Heilbronn . Wartberg, Heilbronn 2001, ISBN 3-86134-703-2 .

- Uwe Jacobi: Heilbronn - days that moved the city . Wartberg-Verlag 2007, ISBN 3-8313-1674-0 .

- Peter U. Quattländer: Heilbronn. Planning the reconstruction of the old town. Documentation for the exhibition of the City Planning Office 1994. Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1994, ISBN 3-928990-45-4 ( Small series of publications by the Heilbronn City Archives. Volume 28).

- Roland Reitmann: The avenue in Heilbronn. Functional change in a street . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1971 (Small series of publications by the Heilbronn City Archives, 2).

- Christhard Schrenk , Hubert Weckbach , Susanne Schlösser: From Helibrunna to Heilbronn. A city history (= publications of the archive of the city of Heilbronn . Volume 36 ). Theiss, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8062-1333-X .

- Christhard Schrenk, Hubert Weckbach: "... for your account and risk". Invoices and letterheads from Heilbronn companies . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1994, ISBN 3-928990-48-9 (Small series of publications by the Heilbronn City Archives. Volume 30).

- Helmut Schmolz / Hubert Weckbach: Heilbronn with Böckingen, Neckargartach, Sontheim. The old city in words and pictures . 3. Edition. Konrad, Weißenhorn 1966 (publications of the archive of the city of Heilbronn, 14).

- Helmut Schmolz / Hubert Weckbach: Heilbronn. History and life of a city . 2nd Edition. Konrad, Weißenhorn 1973, ISBN 3-87437-062-3 .

- Alois Seiler: The Teutonic Order House and the City of Heilbronn in the Middle Ages. In: Katholische Pfarrgemeinde St. Peter and Paul, Heilbronn (ed.): Das Deutschordensmünster St. Peter and Paul Heilbronn, 1995. Festschrift for the renovation in 1994/95 and for the consecration of the altar on July 2, 1995, pp. 45–59.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Fekete et al., P. 104.

- ↑ Quattländer: Heilbronn - planning the reconstruction of the old town, p. 69.

- ^ Jacobi: Heilbronn - days that moved the city . P. 23. (The second destruction)

- ↑ City of Heilbronn, City Planning Office: Heilbronn: Modern Urban Design - Development of the City 1945–1990, Mokler GmbH, Heilbronn 1991 (exhibition of the City Planning Office Heilbronn - on the occasion of the 1250 years of Heilbronn), p. 41, image no. 136 (“Rosenberg” building area).

- ^ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 90 and p. 9.

- ↑ Königshof in Heilbronn - Swabia and Franconia: Local history supplement to the "Heilbronner Voice" from July 8, 1967.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Lückmann: renovation of the German Medal Minster in Heilbronn . In: Catholic parish of St. Peter and Paul, Heilbronn (ed.): The German Order Minster of St. Peter and Paul Heilbronn. Festschrift for the renovation in 1994/95 and for the consecration of the altar . Süddeutsche Verlagsgesellschaft, Ulm 1995, p. 27 .

- ↑ a b c Christhard Schrenk , Hubert Weckbach , Susanne Schlösser: From Helibrunna to Heilbronn. A city history (= publications of the archive of the city of Heilbronn . Volume 36 ). Theiss, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8062-1333-X , p. 25 .

- ↑ Max Georg Mayer: Discoveries during the renovation work on the Teutonic Minster St. Peter and Paul in Heilbronn . In: Catholic parish of St. Peter and Paul, Heilbronn (ed.): The German Order Minster of St. Peter and Paul Heilbronn. Festschrift for the renovation in 1994/95 and for the consecration of the altar . Süddeutsche Verlagsgesellschaft, Ulm 1995, p. 31 .

- ↑ Fekete et al .: Monument topography, p. 35.

- ^ Mayer: Discoveries during the renovation work on the Teutonic Minster of St. Peter and Paul in Heilbronn, p. 31 f

- ↑ a b Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 11 f. and p. 32 f.

- ↑ Catholic parish of St. Peter and Paul: Deutschordensmünster St. Peter and Paul Heilbronn, p. 6 f.

- ↑ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 23.

- ↑ Fekete et al.: Monument topography, p. 38.

- ↑ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 13.

- ↑ Fekete et al .: Monument topography, p. 108.

- ↑ Cf. Fekete: Kunst- und Kulturdenkmale ..., p. 14: There Fekete describes that the renaissance in the cities produced “nationally important early works”. One example of this is the “groundbreaking” tower of Heilbronn's Kilian's Church.

- ↑ a b Fekete et al.: Monument topography, p. 39.

- ↑ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 14.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 23 and p. 18 and cf. Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 32.

- ^ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 24 and p. 25.

- ↑ City pastor Albert Laub: The Heilbronn Teutonic Order Church through the centuries . Self-published by the Catholic parish of St. Peter and Paul, Heilbronn 1952; Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 15 and Lattner / Hennze: Silent witnesses ..., p. 20.

- ↑ See Lückmann: Renovation of the Teutonic Order Minster in Heilbronn . P. 12.

- ^ Seiler: The Teutonic Order House and the City of Heilbronn in the Middle Ages. P. 52 and 56.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 22.

- ↑ Fekete among others: Monument topography . P. 40 f.

- ^ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., pp. 24-25.

- ↑ Helmut Schmolz / Hubert Weckbach: Heilbronn - The old city in words and pictures (1st volume), Konrad-Verlag, Heilbronn, 1966, No. 10 Kilian's Church after the renovation from the market square . 1892, p. 18.

- ^ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 16 f.

- ↑ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 18.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 112: Karl von Etzel.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 24 f. and p. 111 f.

- ↑ a b Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., pp. 32–33: "... the execution is to be kept in the style of the German Middle Ages". Lush variety of styles in historicism.

- ^ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 23 f.

- ↑ Fekete: Kunst- und Kulturdenkmale…, p. 19 f. (Historicism).

- ^ Julius Fekete, Simon Haag, Adelheid Hanke, Daniela Naumann: Monument topography Baden-Württemberg . Volume I.5: Heilbronn district. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1988-3 , pp. 136 .

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 50 f .: “Build! is the demand of the hour, building in the spiritual as well as in the material sense ”- On the way to modernity.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 9.

- ↑ The description essentially follows: Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 50 f .: “Build! is the demand of the hour, building in the spiritual as well as in the material sense ”- On the way to modernity. In addition, Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., and Fekete u. a .: Monument topography ..., used.

- ↑ The description essentially follows: Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen, p. 50 f .: “Build! is the demand of the hour, building in the spiritual as well as in the material sense ”- On the way to modernity. In addition, Fekete, Kunst- und Kulturdenkmale…, p. 18 and Fekete ao: Monument topography, p. 140 f .: Wollhausstraße 93 , were used.

- ↑ Cf. Fekete et al.: Monument topography, p. 94 f: Gutenbergstrasse 37 - Villa Dopfer .

- ↑ See Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 124: Hermann Muthesius (1861–1927) .

- ↑ See Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 59: 1911–1916 Theodor Moosbrugger .

- ^ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 126: Heimatstil .

- ↑ a b Julius Fekete et al .: Monument Topography Baden-Württemberg Volume I.5 Stadtkreis Heilbronn . Edition Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1988-3 , page 136

- ↑ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 21.

- ^ Fischer: Thoughts on the architecture of the theater .

- ↑ Schmolz / Weckbach (1966), No. 56, page 45.

- ↑ Heuss: The new theater building, p. 2.

- ↑ Volker Helas, Gudrun Peltz: Art Nouveau architecture in Dresden . KNOP Verlag for Architecture - Photography - Art, Dresden 1999, ISBN 3-934363-00-8 . , P. 26 image no. 22nd

- ↑ Heuss, Der neue Theaterbau , p. 2 and Schmolz / Weckbach (1966), No. 56, p. 45

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 45.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze, Stille Zeitzeugen , p. 50 f .: “Build! is the demand of the hour, building in the spiritual as well as in the material sense "- On the way to modernity:

- ↑ Fekete, art and cultural monuments… , p. 19 f: - Modernism

- ↑ Fekete, art and cultural monuments ... , p. 21.

- ↑ Chronik Heilbronn, Vol. X, 1970 to 1974; Entry October 19, 1974, p. 425

- ↑ Chronik Heilbronn, Vol. X, 1970 to 1974; Entry December 7, 1974, p. 441

- ^ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 127: New building .

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 51.

- ↑ a b c d e Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 19 f: Modernism .

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 23 and Fekete: Kunst- und Kulturdenkmale ..., p. 19 f.

- ↑ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 54.

- ^ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 126: Functionalism .

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen…, p. 119 (Ludwig Knortz 1879–1936 architect) and p. 90 (Modern or fashionable? The art of furnishing oneself - examples of residential architecture in Heilbronn)

- ↑ Christhard Schrenk , Hubert Weckbach , Susanne Schlösser: From Helibrunna to Heilbronn. A city history (= publications of the archive of the city of Heilbronn . Volume 36 ). Theiss, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8062-1333-X , p. 181 f .

- ^ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 59.

- ↑ Fekete et al .: Monument topography, p. 55.

- ↑ Fekete et al.: Monument topography, p. 57 and Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen…, p. 122 (Hannes Mayer 1896–1992 architect).

- ↑ Fekete et al .: Monument topography, p. 57.

- ↑ Fekete et al .: Monument topography, p. 99.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze, Stille Zeitzeugen…, p. 119: Paul Schmitthenner 1884–1972 architect.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 73.

- ↑ Heilbronner Voice, September 3, 1998 from (hoef): Hidden Gem . Wüba building classified as a cultural monument .

- ↑ Fekete et al .: Monument topography, p. 164.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 72.

- ↑ Fekete et al.: Monument topography, p. 101 f. and Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 48 f.

- ↑ Fekete et al.: Monument topography, p. 58 f. and Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 19 f.

- ^ Pfeiffer: … art of the 50s . P. 102, illustration no.139.

- ^ Pfeiffer: … art of the 50s . P. 94 and p. 96, illustration no.129.

- ^ Pfeiffer: … art of the 50s . P. 20 and p. 102, Figure No. 137 and p. 103.

- ^ Pfeiffer: … art of the 50s . P. 102 and p. 103, fig. 138.

- ^ Pfeiffer: … art of the 50s . Pp. 93/94.

- ↑ Fekete et al .: Monument topography, pp. 96 f., 52, 58.

- ↑ Fekete: Art and cultural monuments ..., p. 21.

- ↑ Inauguration of Harmony . In: Uwe Jacobi: That was the 20th century in Heilbronn . Wartberg, Heilbronn 2001, ISBN 3-86134-703-2 . P. 62

- ↑ Andreas Pfeiffer (Ed.): Heilbronn and the art of the 50s. The art scene in Heilbronn in the 1950s. Situations from everyday life, traffic and architecture in Heilbronn in the 50s . Harwalik, Reutlingen 1993, ISBN 3-921638-43-7 (Heilbronner museum catalog , 43rd series Städtische Galerie). P. 95, fig. 127, fig. 128; P. 96

- ↑ http://www.stadtsiedlung.de/fileadmin/files/Heilbronn_MZ_9_06_Ansicht.pdf

- ↑ tz: A large commercial building planned at Sülmertor. Plans for the site at the corner of Salzstrasse and Neckarsulmer Strasse / model by a young French architect. In: Heilbronn voice . No. 186 , August 14, 1964, p. 9 .

- ^ Jacobi: That was the 20th century in Heilbronn. P. 79

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., pp. 9, 72 f., 87 f.

- ↑ Lattner / Hennze: Stille Zeitzeugen ..., p. 9, p. 72, p. 73.

- ↑ Michael Trieb, Alexander Schmidt, Stephan Börries, Barbara Grunwald, Barbara Holub, Matthias Kumkar, Seog-Jeong Lee, Ruth Schaufler, Thomas Utsch, Jochen Siebenrock: Stadtbildrahmenplanung. Stuttgart 1988.

- ^ City of Heilbronn, city planning office (ed.): Heilbronn: Modern urban design - development of the city 1945-1990. Printed by Mokler, Heilbronn 1991 (exhibition by the Heilbronn City Planning Office on the occasion of the “1250 years Heilbronn” anniversary)

- ^ Spoonhardt: Heilbronn. New architecture in the city and district. P. 16

- ↑ http://www.uni-stuttgart.de/hi/gnt/campus/Stationen/vaihingen/west/info_station_l1.html

- ↑ Article in the Heilbronn voice by Bärbel Kistner of October 7, 2006: Everyone agrees on the cloister courtyard .

- ↑ Article in the Heilbronner Voice of April 29, 2004 by Dagmar Driver: Irreführung

- ↑ a b c d Article in the Heilbronner Voice of January 23, 2008 by Kilian Krauth: Such a structure needs space

- ↑ Article in the Heilbronner Voice of May 7, 2008 by Kilian Krauth: How big city is Heilbronn really? Does the ECE deserve an award?

- ↑ Article in the Heilbronner Voice of January 31, 2008 by Joachim Friedl: Neuer Kiliansplatz until the end of 2008

- ↑ Erz .: Preserving the valuable old, creating the new in the spirit of the times. Consecration of the renewed St. Peter and Paul Church . Collective work = Heilbronn voice . No. 80 , April 7, 1951, pp. 4 .

- ^ Renz / Schlösser: Chronik Heilbronn… 1945–1951, p. 281 and Renz / Schlösser: Chronik Heilbronn… 1952–1957. P. 342.

- ↑ Fekete among others: Monument topography. P. 60.