al-Khidr

Al-Chidr ( Arabic الخضر, DMG al-Ḫiḍr or al-Ḫaḍir 'the green', Turkish Hızır ) is an Islamic saint who has a permanent place in the imagination of Muslims as a symbol for the cyclically renewing vegetation and personification of the good . Some Muslims also consider him a prophet . According to popular belief, al-Khidr lives in secrecy and is only occasionally visible to individual people, although he can take on different shapes . With regard to his appearances and his ability to float through space, al-Chidr has similarities with an angel , but according to the general opinion it is not an angel, but a person from earlier times, to whom God lives beyond the ordinary Dimension has extended; only at the end of time should he die. There are various legends about the reason for this extension of life.

One of the most important foundations for the Islamic worship of Chidr is the Koranic story about the pious servant of God who puts Moses to the test ( Sura 18 : 65–82). Based on a hadith , this servant of God was identified with al-Chidr. Sufis viewed al-Khidr as an important role model because of this narrative. Al-Khidr also has a particularly close relationship with the biblical prophet Elias . According to a popular belief, the earth is divided between al-Chidr and Elias, and the two should meet once a year. In Anatolia and among various Muslim groups in the Balkans and Eastern Europe , this gathering is celebrated on May 6 with the Hıdrellez Festival.

As a vegetation and water saint, al-Chidr is also venerated by the Zoroastrians in Iran , the Yazidis in Iraq , the Hindus in Punjab and the oriental Christians in the Levant . The latter equate him with Saint George . Since the 18th century, al-Khidr has also been a popular figure in Western literature as the spiritual leader of poets and people on a mystical path. In 2016, UNESCO added the traditions associated with al- Khidr in Iraq and the Hıdrellez Festival in 2017 to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity . Within Islam, however, there is also criticism of the worship of Chidr. Various Muslim scholars have written books in which they rejected the belief in the continued existence of al-Chidr and its function as a model for antinomic behavior. One of the harshest critics of Chidr piety was the Hanbali scholar Ibn al-Jschauzī (d. 1200).

Name, surname and honorary title

While al-Ḫiḍr , which means “the green” in Arabic, was only ever understood as a laqab - epithet , there were and are very different doctrines about the real name of al-Chidr and his origins. In the medieval Maghreb it was widespread that al-Chidr was actually called Ahmad . The Egyptian scholar Ibn Hajar al-ʿAsqalānī (d. 1449), who wrote his own treatise on al-Chidr, lists a total of ten different views on the question of al-Chidr's name. Some Muslim scholars also equated al-Khidr with various Old Testament characters, including Melchizedek , Jeremiah , Elijah, and Elisha . The background for these equations was formed by various Christian and Jewish narratives, with which al-Chidr was associated in the Islamic tradition. The doctrine that has become most widespread over time is that al-Chidr, through his father Malkān, was a great-grandson of the biblical boar and was actually called Balyā. It is also propagated at the sanctuary of al-Chidr in Kataragama in Sri Lanka.

If opinions differed about al-Chidr's real name, there was broad agreement about his Kunya surname. Since the 10th century it has been given almost consistently as Abū l-ʿAbbās .

In the countries where al-Khidr is venerated, this name, which is actually just an epithet, is pronounced very differently. The Arabic lexicography already indicates that in addition to the form al-Ḫiḍr , the vocalizations al-Ḫaḍir and al-Ḫaḍr are also permitted. The name al-Ḫuḍr is pronounced in various Arabic dialects of the Syrian-Palestinian region . Due to the different pronunciation of the name in the various languages of the Islamic world as well as the use of different transcription systems when rendering these languages with Latin letters, numerous spelling variants are in circulation, for example Hızır ( Turkish ), Khijir ( Bengali ), Kilir ( Javanese ), Hilir ( Tamil ), Qıdır ( Kazakh ), Xızır or Xıdır ( Azerbaijani ), Khidr, Chidher, Chidhr, El Khoudher, Khodr, al-Jidr, Khizar, Chiser, Chisr, Kyzyr etc. In the following explanations, outside The form “Chidr” is used consistently for quotations, for the sake of simplicity without the Arabic article al- .

In some regions, Chidr's name is given honorary titles. In India, Iran, Central Asia and Anatolia the title Chodscha or Chwādscha ('teacher, master') is used for him, in Iran and Uzbekistan the title Hazrat is prefixed to his name , and in the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs he is Qıdır Ata (Қыдыр ата; "Father Chidr") titled.

The idea of the "encounter with Chidr"

Chidr's general invisibility and its appearances

Fundamental to Islamic Chidr piety is the idea of Chidr's hidden presence among people. An often quoted saying of the famous Shafiite jurist an-Nawawī (d. 1277) reads: "He (i.e. Chidr) is alive and dwelling among us". It should be enough just to say his name for Chidr to appear. Since Chidr is present as soon as he is mentioned, he should be greeted immediately in this case. From the eighth Shiite Imam ʿAlī ibn Mūsā ar-Ridā (d. 818) the statement is narrated: “(Chidr) is present where he is mentioned. Whoever of you mentions him, may speak the salvation salvation over him. "

Although Chidr is actually hidden from view of people, it occasionally becomes mysteriously visible to people who are particularly close to God. Based on a historical tradition related to the battle of Qādisiyya , this idea can be traced back to the early days of Islam. When, on the third night of this battle, when the fighting was particularly intense, a mysterious horseman mingled with the Muslim fighters and supported them against the enemy armies, the Muslims mistook him for Chidr.

Reports of such apparitions of Chidr can be found in numerous works of traditional Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Malay literature. Characteristic of Chidr's appearances in these reports is that they are described as real apparitions in the material world, whereas Chidr rarely appears in dreams . Chidr appears throughout the reports as a figure that brings good fortune. He saves people from need, works as a faith healer, frees people from captivity and comforts those who mourn. The idea of Chidr as a supernatural helper in need is also reflected in the Turkish saying Hızır gibi yetişmek ("like Chidr to come to your aid"), which is used when one wants to express that someone has appeared like a saving angel in an emergency .

The encounter with Chidr has always been understood as a divine honor. In Sufik it is considered a proof that the person who has met Chidr is one of the friends of God .

Reports of Chidr encounters in literature

Reports of encounters with Chidr can be found in the most diverse genres of Islamic literature. Such accounts are particularly common in hagiographic texts because of their importance as evidence of a person's sanctity . Such reports can also be found in biographical collections with a regional focus, historiographical works and in theological imamitic literature. A literary genre in which Chidr also plays a very important role are the so-called folk novels. These include, for example, the Arab Sīrat Saif ibn Dhī Yazin , the Persian Hamzanama , the Turkish epic about Battal Gazi and the Malay story about Hang Tuah . In all these tales, Chidr appears as a supernatural helper and advisor to the heroes. Chidr also plays the same role in Serat Menak Sasak , a shadow play developed by the Sasak people on the Indonesian island of Lombok . Here Chidr appears to the hero Amir Hamza several times in dreams and helps him out of a tight spot.

Most reports of encounters with Chidr that claim to reproduce a true event have only been put down in writing after a more or less long oral tradition . But there are individual Sufi authors who report in their works about Chidr encounters they have experienced themselves. It started with the Andalusian Muhyī d-Dīn Ibn ʿArabī (d. 1240), who tells in his extensive Sufi encyclopedia al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya how he met Chidr three times on his wandering: the first time in Seville , then in the port of Tunis and finally in a half-destroyed mosque on the Atlantic coast, each time setting an important course for his future life.

Almost all accounts of Chidr encounters involve certain basic elements. These include the description of Chidr's mysterious appearance and disappearance, the greeting of the seer by Chidr and the emergence scene, in which the person who initially meets the seer as a stranger turns out to be Chidr. In later times, various symbolic actions often appear, which underline the initiatory character of the encounter with Chidr. These include hugs, handshakes with Chidr or the award of the Sufi patched skirt ( Chirqa ) by him.

Changeability of shape and characteristics

The idea that Chidr can suddenly appear as a stranger is linked to a number of other ideas in Islamic tradition, for example that of the arbitrary changeability of his shape. For those who strive for a meeting with Chidr, the question arises as to how they can recognize Chidr. From the late Middle Ages onwards, one answer to this question has developed that Chidr has certain physical characteristics by which he can be clearly identified (e.g. equal length of index and middle finger, boneless thumb, mercury-like pupils).

Explanations for Chidr's continued life

In the reports of his appearance, Chidr appears as a diffuse figure who can float through space like an angel . As can be seen from a statement by al-Māwardī (d. 1058), there was actually already in the Middle Ages the belief that Chidr was an angel. Yet this doctrine has been rejected by most Muslim scholars as "strange" and "wrong". The only well-known Muslim scholar who defended this doctrine was Abū l-Aʿlā Maudūdī . The prevailing teaching was that Chidr is not an angel, but a person from earlier times who has remained alive. The Koran exegete ath-Thaʿlabī (d. 1036) described him in a much-quoted statement as "a prophet whose life was prolonged" (nabī muʿammar) . The designation of Chidr as "the living one" ( al-ḥaiy ) is still widespread today. In the Persian-speaking world, Chidr is often given the attribute zinda (“alive”). At the Chidr sanctuary on Beshbarmaq Mountain in Azerbaijan , Chidr is referred to as Xıdır Zində piri ("Chidr, the Living Pir ") and tells that he is almost 5500 years old.

Various aetiological legends are cited in traditional Islamic literature to explain Chidr's continued life , of which the legend of the source of life is the best known. According to this legend, the two-horned man ( Dhū l-Qarnain ), already mentioned in the Koran, once went on a search for the source of life that gave immortality, with Chidr being his companion. While the two-horned one missed his goal on this expedition, Chidr recognized the source of life from the fact that a dead fish that he washed in this source came to life. He then took a bath in this spring himself, drank its water and became immortal. As Israel Friedländer has shown in his study on the legend of the source of life, this is a late antique narrative that is already encountered in various oriental versions of the Alexander novel. While Alexander's cook Andreas achieved immortality in the late antique versions of the legend of the source of life, this role is transferred to Chidr in the Islamic versions of the narrative.

According to another tradition, which can already be found in the Arab philologist Abū Hātim as-Sidschistānī (d. 869) and which is passed on by Muslim scholars to this day, Chidr's life was prolonged because after the Flood he carried the body of Adam that Noah had carried with him buried. This tradition is an Islamic adaptation of the Melchizedech legend from the Syrian-Aramaic treasure cave .

Finally, there is a third etiological legend for the longevity of Chidr, which relates him to the Israelite prophet Jeremiah . A detailed version of this story can already be found in the world chronicle of at-Tabarī , where it is traced back to the authority of the traditionalist Wahb ibn Munabbih (d. 732). According to this legend, Chidr-Jeremiah was called by God to be a prophet before he was born; After the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar , he fled to the wild animals in the desert, where God extended his life beyond the usual lifetime. This legend, in which Chidr appears as a volatile man, is also available in different versions.

The Koranic story of Moses and the servant of God

Fundamental to the Chidr image in the Islamic scholarly tradition is his identification with the servant of God, who is mentioned in Sura 18:65: "There they found one of our servants, to whom We had given grace from Us and taught knowledge from Us". She connects Chidr with the story of Moses , his servant and the servant of God (18: 60–82), which is one of the great narrative sections of Sura 18, the so-called cave sura. This story tells how Moses goes on a journey with his servant in search of the “connection between the two seas” (maǧmaʿ al-baḥrain) . He recognizes the place he is looking for by the fact that his servant has forgotten a fish that he had taken as provisions and that it escaped into the sea. At the relevant point, where there is a rock, they come across the named servant of God, whom Moses accompanies at his own request. On the way, the nameless servant of God commits three seemingly absurd acts one after the other (he perforates a ship, kills a boy and repairs a wall in a city where the two are turned away), which Moses questions each time. At the end he receives the explanations of the three actions from the servant of God, but then has to leave him.

The basis for Chidr's identification with the servant of God named in this story are generally recognized hadiths that comment on them. They have been included in the two great collections of traditions of al-Buchari (d. 870) and Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj (d. 873), where they are traced back to the Prophet via the Kufic traditionalist Saʿīd ibn Jubair (d. 714) . The servant of God is identified in these hadiths with Chidr and Moses' servant with Joshua .

Due to the identification with the Koranic servant of God, Chidr is considered in the Islamic tradition as the owner of a special, divine knowledge, which is also called Ladun knowledge (ʿilm ladunī) . This term goes back to the description of the servant of God in verse 65, where it says: wa-ʿallamnā-hu min ladun-nā ʿilman (literally "and whom we have taught about knowledge"). In some reports of encounters with him it is told how Chidr imparts such Ladunian knowledge to people.

Theories about the origin of the narrative

Since the middle of the 19th century, a number of mainly German-speaking scholars have been investigating the origin of the Moses God's servant story. Building on her research, Arent Jan Wensinck put forward the theory in the 1920s that the Qur'anic Mose-Gottesknecht narrative came about through the confluence of three sources: During the first part of the narrative (18: 60–64) on Gilgamesh -Utnapishtim episode in the Gilgamesh epic and the legend of the source of life in the Alexander novel goes back, the second part (18: 65–82) is dependent on the Jewish legend about Elijah and Rabbi Joshua ben Levi .

However, this three-source theory, which today is widely used worldwide through unquestioned copying, cannot be upheld. If one assumes that pre-Islamic narrative material found its way into the Koran, one can deduce from the similarities of the passages mentioned in the Gilgamesh epic and the Alexander novel that they were the models for the first part of the story (18: 60-64) have served. Against the dependence of the second part of the story (18: 65–82) on the Jewish legend about Rabbi Joshua ben Levi, however, speaks that the oldest evidence for this legend, the version of Rabbi Nissim ben Jakob (approx. 990-1062) Kairouan , is considerably younger than the Koranic story. No pre-Islamic parallel text is known for the second part of the Qur'anic narrative (18: 65–82).

Localizations of the event

As early as the Islamic Middle Ages, attempts were made to localize the events described in the Koranic story in certain regions. The geographer al-Qazwīnī (d. 1283) reports that there were people who located this event in Shirvan near Derbent . They said that the rock on which Joshua forgot the fish was there and that the sea named in the story was the Caspian Sea ( baḥr al-Ḫazar ). They equated the place where Chidr had erected the wall with the city of Bādschirwān in what is now the district of Cəlilabad , and the name of the place where Chidr had killed the boy was Jairān. The Azerbaijani historian Abbasgulu Bakıkhanov (d. 1847) states that the rock where Moses and Chidr met is identical to the rock that people call the "stone of the living Chidr" ( sang-i Ḫiẓr-i zinda ) is known. He probably meant the Beshbarmaq rock near Siyəzən , which is venerated to this day under the name Xıdır Zində ("living Chidr") and on which there is a Chidr shrine.

Other scholars, however, localized the event in Ifrīqiya . In works of Tunisian local historiography, for example, it is stated that Moses and Chidr met on the eastern slope of the Zallādsch Mountain near Tunis . The ship mentioned in the Koranic story is said to have perforated Chidr on the lake of Tunis , which was formerly called the "Sea of Radès " ( baḥr Rādis ), the point between this "sea" and the Gulf of Tunis being the "connection between the two seas “Should be identical. According to this tradition, the boy was finally killed in Tunbudha, today's al-Muhammadīya, 15 kilometers south of Tunis. It is there that Chidr and Moses are said to have separated after their meeting. That's why Chidr has a particularly close relationship with this region. In a paper on the holy places of Tunis, probably written by ʿAlī ibn Muhammad al-Hauwārī in the late 13th or early 14th century, it is reported that there are said to be four places in and around Tunis that Chidr visits every day Should pay a visit, including the Ez-Zitouna Mosque and the Zallādsch Mountain in the south of the city, where the Jallāz Cemetery is located today. Chidr is said to have met quite a number of people in Tunis, including Muhyī d-Dīn Ibn ʿArabī and Abū l-Hasan al-Shādhilī (d. 1258), the founder of the Shādhilīya .

Another region in which the event has been located is the mouth of the Orontes between Antakya and the small town of Samandağ . The city, the wall of which Chidr is said to have rebuilt, is often identified with Antakya even in medieval Islamic literature. Today's population in Hatay believes that the place where Moses and Chidr met is Samandağ, the killing of the boy is said to have taken place in Latakia and that the wall was rebuilt in Antakya. The whole region around Samandağ has a particularly close relationship with Chidr. According to the vernacular, he owns 366 sanctuaries here. The largest Chidr sanctuary in the region is located on Samandağ Beach at the point where Chidr and Moses are said to have met. In the last few decades this sanctuary has been gradually enlarged.

Chidr in traditional Islamic cosmology

Chidr as a symbol for the cyclical renewal of vegetation

Muslim scholars give different explanations for Chidr's name “the green one”, for example that Chidr usually wears green clothes when he encounters people. Most authority, however, is held by the explanation that is traced back to the Prophet Muammad via Abu Huraira and which is passed on in almost all important hadith works. It says that Chidr was only called that because he sat on a white farwa , whereupon it began to move under him and turned green (fa-iḏā hiya tahtazzu min ḫalfi-hī ḫaḍrāʾ) .

|

|

|

|

On the left an olive tree in Kerak , which was venerated as a Chidr sanctuary at the beginning of the 20th century, on the right the 680 year old oak in Mahis, which is dedicated to the Chidr.

|

||

The word farwa actually means “fur” in Arabic. The Muslim scholars were not satisfied with it in this context. The Yemeni scholar ʿAbd ar-Razzāq as-Sanʿanī (d. 827) interpreted the word as “dry white grass”, the Kufic philologist Ibn al-Aʿrābī (d. 846) as “white earth on which there are no plants”. According to an-Nawawī, it was "dried up plants", according to another scholar, "the surface of the earth which, after it was bare, is green with plants". These interpretations of the word farwa , of which no trace can be found in other contexts, show that Chidr was taken early on as a symbol for the vegetation that was reviving through God's influence. The belief in Chidr's vegetative power is also shown in the fact that trees in various places were related to him. In the Jordanian town of Mahis ten kilometers west of Amman , which is known for its orchards and springs, there is a sacred grove with a Chidr sanctuary and two 490 and 680 year old oaks that are dedicated to it.

The various Chidr festivals celebrated in Anatolia and Iran in springtime are a practical ritual implementation of the traditional Islamic belief in the revitalizing, spring-initiating effect of Chidr. In the Turkish folk calendar, Chidr day (Rūz-i Hızır) on May 6th, which corresponds to April 23rd of the old Julian calendar , is the beginning of summer time, which extends from this day to November 6th, the so-called Qāsim- Day, extends. The division of the year with the help of these two dates, Chidr and Qāsim days, which can be traced back a long way with the help of Ottoman archive sources, goes back to an old folk calendar that can be traced back to different cultures, which is based on the heliacal rise and fall of Pleiades judges. May 6th is also associated with Khidr in some areas of Azerbaijan : it is considered his birthday in Siyəzən and Dəvəçi Rayons .

In various areas of the Iranian cultural area, Chidr is connected to the so-called Tschilla cycle, which structures the time from the winter solstice to the beginning of spring in the folk calendar. According to this cycle, winter is divided into three sections of different lengths: the first section with 40 days, known as the “great Tschilla”, begins with the Yalda night on December 22nd. The second section with 20 days is called “little Tschilla” and starts on January 30th and ends on February 20th. This is followed by a thirty-day period (called Boz ay = "gray month" in Azerbaijan ), which ends with the Nouruz festival. Individual days or several days within this cycle are dedicated to the Chidr and are named after him. The reason for this is the idea that at this time he visits people's homes, which also gives rise to certain rites . In many areas, a special meal is prepared for him in a separate room in the house, on which Chidr is supposed to leave his mark (see Chidr meal below). The most important date, however, is the end of little Tschilla on February 20th. Large Chidr festivals are celebrated in various areas of Iran's eastern Anatolia and Afghanistan around this date. In Azerbaijan, the four Wednesdays of the Boz-ay period are also associated with Chidr customs.

In those areas in which Chidr is particularly venerated as a vegetation saint, he is also of great importance for agriculture . In Tajikistan , northern Afghanistan and other areas of Islamic Central Asia, for example, he is identified with Bābā-yi Dihqān ("Father Farmer"), an imaginary figure who is considered the founder of the peasant professional guilds. A certain parallel to this identification is Chidr's equation with Saint George in the Levantine region. The name of the Christian saint is derived from the Greek word γεωργός, which, like the Persian word dihqān, means “farmer, farmer”.

Chidr's wandering and flying through the air

Although Chidr is particularly closely related to fertility and vegetation, it is generally accepted that his stay is not restricted to habitats with lush vegetation, but includes all areas of the world. For example, it should especially roam the deserts and be seen there. According to popular belief, Chidr is on the move. Because of this activity, the assumption was made that he was also the model for the medieval-European idea of the Tervagant .

In order to be present wherever it is mentioned, it must be able to cover great distances at lightning speed. Such an ability is usually interpreted in Sufi circles as "contraction of the earth" (ṭaiy al-arḍ) . What it looks like when Chidr hurries over the earth that is contracted beneath him is described in some reports of encounters with him: he walks with dry feet in giant steps over the sea or flies through the air “between heaven and earth”.

Chidr's constant traveling is the starting point for the idea that there are places that serve him as resting places and resting places and are therefore particularly sacred. In the Arab world these places are mostly understood as Maqām al-HIDR called ( "Stand Khidr"), in the Persian-speaking world, the term is qadamgāh-i Ḫizr ( "Fußaufsetzungsort of Khidr") common in the Turkish area they were called Hızırlık or Hıdırlık . The Syrian scholar ʿIzz ad-Dīn Ibn Schaddād (d. 1285) mentions a Chidr mosque on the citadel of Aleppo in his historical topography of Syria and notes: “A group of residents of the citadel reported that they had Chidr - above him be salvation - saw in her praying. ”Even today there is a Chidr-Maqām in the form of a cenotaph in the rise of the citadel in a niche opposite the third gate . It is one of the most famous sanctuaries in the city.

Chidr as lord of seas and rivers

Chidr has a particularly close relationship with seas and rivers. This has to do with the fact that in the Koran the “connection of the two seas” (maǧmaʿ al-baḥrain) is mentioned as the place where Moses is said to have met the servant of God identified with Chidr. A tradition traced back to the South Arabian storyteller Kaʿb al-Ahbār (d. Around 652/3) interprets this connection of the two seas as the place between the upper and lower seas and describes Chidr as a master of marine animals. It reads: “Chidr stands on a pulpit of light between the upper and lower seas. The animals are instructed to listen to and obey him and to show him the spirits (arwāḥ) in the morning and in the evening . "

It is also widely believed that Chidr is on one of the islands in the sea. The Maghreb geographer Ibn Abd al-Munʿim al-Himyarī (15th century) describes the legendary island of Sandarūsa as Chidr's stay:

“It's a big island in the ocean. It is said that people passed an island in this sea while the sea was rising and storming. Suddenly they saw an old man with white hair on his head and beard, wearing green clothes and floating over the water. He said: 'Blessed be the one who has set things in motion, knows what is in the heart, and with His power bridles the seas. Travel between east and west until you get to mountains. Stand in the middle and you will be saved by the power of God and you will remain unharmed '. They aligned themselves according to the azimuth he had given them [...] and were saved. The one who showed them the way was Chidr, whose abode is that island. It is in the middle of the great sea. "

It is conceivable that Sandarūsa is a corruption of Sarandīb, the old Arabic name of Sri Lanka, because Chidr is also closely related to this island. The Arab traveler Ibn Battūta (d. 1377) found a Chidr cave on the slope of Adam's Peak during his visit to the island , and two important Chidr shrines still exist in Sri Lanka in Kataragama and south of the city of Balangoda . Kataragama is the heart of an entire region of villages that is said to be under Chidr's protection. The island off the coast of South India, mentioned in the Malay epic Hikayat Hang Tuah , on which the eponymous hero Hang Tuah experiences an encounter with Chidr, is possibly a reminiscence of Sri Lanka with the sanctuary Kataragama. Other sea islands on which Chidr sanctuaries exist are Failaka off the coast of Kuwait and the Iranian rocky island of Hormuz on the connection between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman .

The story about the island of Sandarūsa reflects the widespread notion of Chidr as the seamen's helper. Various orientalists such as Karl Dyroff, based on this idea, took the view that the Greek sea demon Glaukos lived on in Chidr . The name Ḫiḍr was just a copy of the word Γλαῦκος ( glaukós , 'blue-shiny', 'blue-green'). Although the Chidr figure with the variety of ideas attached to it can by no means be fully derived from the Glaukos legend, the name and the relationship to the sea are actually traits that connect Chidr to Glaucos. Like Chidr, Glaucos was also known for his apparitions and prophecies.

The traditional Muslim exegesis, based on certain verses of the Koran (e.g. Sura 25:53 ), does not see two concrete seas in the two seas of the maǧmaʿ al-ba ,rain , but rather the total mass of the salt water and the fresh water stored under the mainland, which the Springs, rivers and lakes. This is probably why many mainland waters are also related to Chidr. Chidr was identified with the Oxus in Transoxania and with the Indus in Sindh . Richard Francis Burton , who stayed in Sindh for a long time at the beginning of the 19th century, performs a prayer hymn to the Indus in his geographical work on this region, which clearly shows this equation of Chidr with the river. The first verse of this hymn, which was often sung in its day, reads in its translation:

“O thou beneficent stream! O Khizr, thou king of kings! O thou that flowest in thy power and might! Send thou joy to my heart! "

“O you blessed river! O Khizr, you King of Kings! O you who pour out your strength and power [in us]! Send joy to my heart! "

A Chidr shrine is still located on a small island in the Indus between Rohri and Sukkur . British administrative records show that it enjoyed a high reputation among the population in the 19th century and that several thousand people from Sindh and the neighboring regions traveled to its annual festival (melā) . As Alexander Burnes reports, there was a widespread belief among the local population that the Palla fish, popular in local cuisine, which migrates up the Indus to the Sukkur area in spring, only does so to pay homage to Khwaja Khizr . The fish, he was told, should never turn their rear end towards him when they circle the sanctuary. In Punjab, Chidr was the patron saint of fishermen and all those who were professionally involved with water. On miniatures from Mughal India and popular lithographs from the Punjab, Khwaja Khizr is depicted as an old man standing on a fish. To this day, the belief in Chidr's miracle power is widespread among the local population. It is said that Chidr saved Rohri, Sukkur and Lansdowne Bridge from destruction during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 when they were bombed by Indian warplanes.

Due to the traditional interpretation of the two seas as salt and fresh water, especially those places where rivers flow into the sea were related to the Chidr figure. The mouth of the Orontes , where the worship of Chidr is particularly strong, has already been mentioned. Another example is the island of Abadan located in the mouth of the Karun , framed by the Shatt al-Arab in the west and the Bahmanschir Canal in the east . On this island, which is still known today as Ǧazīrat al-Ḫiḍr ("Chidr Island"), there has been a Chidr sanctuary since the Middle Ages. In a similar way, the mouth of the Nile was related to Chidr in the Middle Ages. After all, there is still an estuary sanctuary dedicated to Chidr in the east of Beirut , at the point where the Nahr Beirut, the ancient Magoras River, flows into the sea.

Chidr and the Holy Places of Islam

Mosques are the preferred places to stay for Chidr on his travels. In some places like Bosra and Mardin , small mosques named after him still exist today. Above all, Chidr's appearance is part of the sacred aura of the great Friday mosques . Various traditions tell of his regular stay in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, the Ez-Zitouna Mosque of Tunis and the Hagia Sophia , the former main mosque of Istanbul.

Chidr has a particularly close relationship with the holy places in Jerusalem. In a legend quoted by the biographer Ibn Hisham (d. 834) in his kitab at-Tīǧān in his South Arabian legend collection , Chidr appears as a prophet who resides in Jerusalem . A tradition that is traced back to the Syrian traditionalist Shahr ibn Hauschab (d. 718) specifies the place where Chidr is supposed to “live” in Jerusalem, as the place between the “Gate of Mercy” (Bāb ar-Raḥma) , which is known today as the Golden Gate , and the "Gate of the Tribes" (Bāb al-Asbāṭ) to the north of it . There are also various other places in the Holy District of Jerusalem that Chidr is said to have visited and that play an important role in popular religious practice, for example the Chidr dome (qubbat al-Ḫiḍr) on the northwest corner of the Haram platform, and the so-called "black stone slab" behind the northern gate of the Dome of the Rock .

However, Chidr's presence is not limited to Jerusalem, rather he should also visit the other holy places of Islam on a regular basis. In the tradition of Shahr ibn Hauschab already mentioned, it says:

“(Chidr) prays every day in five mosques: in the Holy Mosque (sc. Of Mecca), in the Mosque of Medina , in the Mosque of Jerusalem, in the Mosque of Qubā ' and in the Mosque of Mount Sinai . He eats every Friday two meals of celery, once he drinks from the Zamzam -water and washes himself with it another time from the Solomon Fountain, located in Jerusalem, and sometimes he washes himself in Siloam source and drink it. "

Since Chidr is said to be regularly at the holy places in Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem, they are also often the scene of reports of encounters with him. The expectation of being able to meet Chidr in the Holy Mosque of Mecca was so widespread that collective rites later even developed in this regard. The Meccan scholar īAlī al-Qārī (d. 1606) reports that in his time on the first Saturday of the month of Dhu l-qaʿda women and men used to gather at a gate of the Holy Mosque for the time of evening prayer, on the assumption that the first to come out of the mosque at that time is the Chidr.

Chidr's role in the end times

Very early on, Chidr was also assigned an eschatological role. The basis for this is the hadith, according to which at the end of time, when Dajāl roams the country and seduces people to evil , a man who is “the best of men” confronts him near Medina and calls him “ Dajal, whom the Messenger of God told us about ”. The Dajjal kills him and shortly thereafter brings him back to life, but is unable to repeat this. Chidr gets his place in eschatology by being equated with the witness of faith mentioned in this hadeeth, who is killed and resuscitated by Jajal. The Basrian legal scholar Ma Gleichmar ibn Rāschid (d. 770) is named as one of the first teaching authorities for this equation . He is said to have given this opinion in his hadith collection al-Ǧāmiʿ .

In the later Islamic accounts of the end-time events, it is not Dajāl who revives Chidr, but God. In the Qisas al- Anbiyāʾ work by al-Kisāʾī, this event is particularly impressively described as a test of strength between God and Dajāl:

“The Dajjal is a tall man with a wide chest. His right eye is blind ... He will circle the whole earth east and west until he comes to the land of Babylon. Chidr meets him there. The Dajjal will say to him: 'I am the Lord of the Worlds!' But Khidr will reply: 'You are lying, Dajjal! The Lord of the heavens and the earth is not a one-eyed man. ' Then the Dajjal kills him and says: 'If this one God had, as he claims, he would now revive him.' Immediately God brings Chidr back to life. He gets up and says, 'Here I am, Dajjal! God resuscitated me. ' It is said that he will kill Khidr three times, but God will bring him back to life each time. "

The idea that Chidr confronts and opposes Dajal at the end of time is very widespread in the Islamic world from the 13th century. In a Javanese eschatological poem from 1855, the dispute between Chidr and the Dajāl is even described as a "war".

The relationship between Chidr and Elias

Chidr has a particularly close relationship with the biblical prophet Elijah , who is usually referred to as Ilyās in Islamic sources . Since of the numerous name forms used in German for this prophet, Elias is closest to the name Ilyās used in Islamic sources, this name form will be used throughout in the following. The information on the relationship between Chidr and Elias are very different in the Islamic sources and sometimes contradict each other. Fundamental to the Islamic understanding of Elias, however, is the idea that Elias, like Chidr, is still alive and should only die at the end of time.

The division of the earth between Chidr and Elias

According to popular belief, there are four prophets in total who did not die: besides Elias and Chidr, who live on earth, Idrīs and Jesus in heaven. In most of the traditions about these four prophets, the two earthly prophets are also assigned fixed residence areas: While Chidr is on the sea, Elias travels on the mainland and in the steppes. The sea and mainland are considered to be their fixed areas of responsibility with which they are each entrusted.

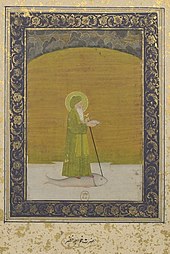

The stereotypical formula of Chidr on the sea and Elias on the mainland can be found in many sources, but also the other way round. This shows that Chidr was not given a figure with its own individuality, but a kind of doppelganger. Chidr and Elias were aligned on many points in the Islamic tradition. For example, Elias' continued life was soon attributed to the fact that he had drunk from the source of life. In Persian and Turkish painting, the scene of Elias and Chidr at the source of life was often depicted (see illustrations).

The cyclical cancellation of the separation

The idea that the separation between Chidr and Elias is canceled at cyclical intervals is also very common and old. The two should meet every year for a pilgrimage in Mecca or in the Arafat plain and in Ramadan for fasting together in Jerusalem. In Anatolia and the Balkans, the gathering of Chidr and Elias even gives rise to an independent festival. In these areas this gathering is celebrated to this day with the Hıdrellez Festival , which also takes place on May 6th. According to a widespread belief, the two figures meet somewhere on the coast the night before this festival, i.e. where the sea and the mainland meet. In addition to Hıdrellez, there is another festival associated with both saints, namely the Chidr Elias festival of the Turkmens and Yazidis in northern Iraq. However, this is celebrated in February and is in the tradition of the Iranian Chidr days of the Tschilla cycle. This festival will Dabke Dances danced and there are horse races. Special sweets are also prepared.

The traditions according to which Chidr and Elias meet at cyclical intervals can be described as myths of the “eternal return” in the sense of Mircea Eliade . Such myths, which can be found in almost all religions in the world, symbolize the periodic renewal of time. In the Turkish Hıdrellez festival, the meeting of Chidr and Elias even coincides with the return of spring and the renewal of nature. Yaşar Kemal , who created a literary memorial to this festival in his novel Bin Boğalar Efsanesi , published in 1971 , gives a picture of the ideas surrounding the Hidrellez Night:

“That night, Elias, the patron saint of the sea, and Hizir, the patron saint of the mainland, will meet. Since the beginning of time it has always been that night, once a year. Should they fail in a year, the seas would no longer be seas and the land would no longer be land. The seas would be without waves, without light, without fish, without colors and would dry up. In the country no flowers would bloom, no more birds and bees would fly, the wheat would no longer sprout, the brooks would no longer flow, rain would not fall, and women, mares, she-wolves, insects, everything that flies and crawls there, Birds, all creatures would become sterile. If they don't meet, the two of them ... then Hizir and Elias become harbingers of the Last Judgment. "

Renewal of time also means warding off the end times. In this context belong the various traditions according to which Chidr and Elias should meet every night on the wall of the two-horned man to defend him against the attacks of the eschatological peoples Gog and Magog .

Chidr in the role of Elisha

Just as Elias was often integrated into the life source legend as Chidr's companion in the Persian and Turkish language areas, there, conversely, Chidr was linked to the well-known Islamic Elias legends. Neysāburi (11th century) and the dependent Rabghūzī (14th century) identified him in their Qisas al-Anbiyāʾ works with Elias' companion Elisha and tell based on the biblical Elias stories ( 1 Kings 17 EU -18 EU ), how the two together convert a people of Baals worshipers to Islam. The story in the two Qisas al-Anbiyāʾ works, however, has some deviations from the biblical story. It is said that Chidr and Elias take power over the rain clouds through a supplication and then retreat to a mountain, where they spend the time with constant prayer. The people who worship Baals suffer a great drought and famine due to the lack of rain. After a time, the king sends a number of people to Chidr and Elias to persuade them to return to the city. Since the people are not ready to be converted to God, they are destroyed by Chidr and Elias. Only after the king and all the inhabitants of the city have gone out to Chidr and Elias and have converted to God with them, God sends rain and redeems the people from the famine.

The equation of Chidr with Elisha, which can be found in many other works, is traced back to the Balch traditionarian Muqātil ibn Sulaimān (d. 767).

The equation of Chidr with Elias

In addition to equating Chidr with Elisha, there was also the opinion that Chidr was identical with Elias himself. The Melkite patriarch Eutychios of Alexandria (d. 940) already reports on this view . In his world chronicle Naẓm al-ǧauhar , he writes in connection with the biblical story about Elias that the Arabs call him Chidr. The fact is, however, that equating Chidr with Elias was always only a minor opinion among Muslim scholars. An important representative of this lesser opinion was the Persian vizier and historiographer Raschīd ad-Dīn (d. 1318). In later times, this equation of Chidr with Elias spread, especially among the Shiites in Lebanon and Iran.

Two of the places where Elias worked as mentioned in the Bible are also related to Chidr today. One place is the Lebanese town of Sarafand 15 kilometers south of Sidon , which is identified with the biblical Sarepta, the place where Elias ate the widow (cf. 1 Kings 17.9 EU ). Here is a Chidr shrine, which is called maqām al-Ḫiḍr al-ḥaiy ("place of the living Chidr"). The other place is the Elijah Cave on the slope of Mount Carmel above Haifa (cf. 1 Kings 18.19-40 EU ), in which from 1635 to 1948 a mosque dedicated to Chidr was housed. The French barefoot Carmelite Philip of the Blessed Trinity (1603–1671), who visited the place in the 17th century, reports that Elias was called el Kader by the Arab inhabitants and the cave was inhabited by Muslim hermits . Samuel Curtiss, who visited the cave in the summer of 1901, describes it as the Chidr sanctuary and reports that it is "visited by Mohammedans, Druze, Persians (Babites), as well as Christians and Jews". Even today the cave is a place for interfaith encounters.

Merging into a double saint "Chidr-Elias"

In some places, the two figures also merge into a double saint named "Chidr-Elias". This is particularly the case in Iraq. For example, Max von Oppenheim writes in his travelogue From the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf : "The [...] personalities of Chir and Elīas are united in Baġdād in a single person who bears the name of Chiḍr-Elīas." The Chidr sanctuary of Baghdad, which is located in the Karch district directly on the banks of the Tigris, is also called Maqām Ḫiḍr Ilyās by the local population . As a sanctuary dedicated to Chidr-Elias, it is mentioned in the Baghdad Salname for the year 1312 of the Hijra (= 1894 AD), in the first place in a list in which the sanctuaries of this district are listed.

Another place in Iraq, which is called "Chidr-Elias", is the Mar-Behnam monastery southeast of Mosul with the associated village. Until it was destroyed by IS fighters in March 2015, there was a dome grave on the site of the monastery with a Uyghur inscription from around 1300 AD, in which the blessing of Chidr-Elias on the Ilkhan ruler, his court and his wives is called down. The dome tomb is venerated by the local population as the Chidr Elias sanctuary.

The double name can also be found in a similar form in several European reports on the Turks of Asia Minor from the early modern period. Georgius de Hungaria, for example, mentions the Saint Chidirelles in his tract De moribus Turcorum, which was first printed in 1481, and reports that he is called for help mainly by travelers in need. Hans Dernschwam , who visited Anatolia around the middle of the 16th century, writes in his travel diary: “The Turks do not yet know about khainem hailigen as from S. Georgen, whom we call Chodir Elles, [...] because he did not die and still live. ”Whether Chidr and Elias in Anatolia really became a single person with a double name, or whether the European travelers only wrongly concluded from the coincidence of St. George's Day and Hıdrellez festival on April 23 of the Julian calendar that the Turkish Saint, who corresponds to Saint George, has this double name, is not entirely clear.

The double name Chidr-Elias is also known in Azerbaijan , but Chidr-Elias is only one of three manifestations of Chidr. The Azerbaijani tradition divides Chidr into three persons: Xıdır Zində (“the living Chidr”), Xıdır İlyas (“Chidr-Elias”) and Xıdır Nəbi (“Chidr, the Prophet”). You are supposed to be three brothers. Xıdır İlyas is called on the water, Xıdır Nəbi on the mainland, and Xıdır Zind wenn when asked for success in performing deeds.

Chidr customs

Consecrations and sacrifices

Gustaf Dalman observed that in Palestine oil or sweets are often brought to Chidr shrines as consecration offerings (nuḏūr) . Similar customs are also recorded for Eastern Arabia. Before it was destroyed in the 1980s , the Chidr shrine on Failaka Island contained a lingam- shaped stone idol on which the sweet dishes were placed. Similar offerings are also offered at the Chidr shrine in Bahrain . This is located on a small rocky island that lies west of the beach of al-Muharraq and is called as-Sāya . At low tide, when the island is connected to the mainland, it is visited by pilgrims from all parts of Bahrain, who deposit gifts and food there. These are then washed away by the water at high tide. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, sacrifices were also offered for Chidr in Sinai , Syria and the territory of Jordan.

Deployment of light boats

In Iraq, Syria, northern India and Bangladesh, there is a custom of making small boats of lights swim down the rivers as a dedication for Chidr in the evening. In Baghdad, where this custom is mainly practiced at the Chidr Elias shrine, it is hoped that wishes such as the cure of illness or sterility will be fulfilled. In Bengal , such light boats are mainly exposed during the so-called raft festival (Bera Bhasan) , which takes place on the last Thursday of the Hindu month of Bhadra (July-August). The stronghold of the Bera Bhasan tradition is Murshidabad in West Bengal . Elaborately designed, head-high ships are equipped with lanterns and placed in the water of the Bhagirathi River with music . The festival practice is documented as early as the 18th century. Of Murshid Quli Khan , who ruled from 1717 to 1727 over Bengal, it is reported that he maintained the "Feast of the Prophet Khidr, be placed on the river at the decorated with paper lanterns Papierbote". The custom was already widespread in Bengal beforehand.

The Chidr Meal

This custom, which is called Sufrat al-Ḫa bzw.ir or Persian Sofre-ye Ḫeżr ("Chidr table") in Arabic and Hızır Lokması ("Chidr bite") in Turkish , is still in Afghanistan, Iran, Azerbaijan today in Turkey and among the Shiites in Iraq. With him, people prepare a multi-dish meal for Chidr in their own homes in the hope that he will visit their home and bless them. The room in which the food is set up is usually cleaned thoroughly beforehand and the most beautiful carpets are laid out. The room is furnished with a prayer rug on which a copy of the Koran and a rosary are placed, a basin, a jug of water and a towel for wudoo ' . When everything is prepared and the door of the room is locked, it is believed that Chidr comes into this house, performs wudoo in the basin, says the ritual prayer and reads the Koran. Then he disappears again after he has blessed the house in question. After opening the room again, look for traces that Chidr has left on the food. In Iran and Azerbaijan, the flour-like substance prepared for chidr is called qāwut and qovut, respectively . After the presented touch by Chidr, it is solemnly eaten in the family circle.

As can be seen in Adam Olearius' travelogue , this ceremony was held in Persia as early as the 17th century. He covers it in his travelogue under the title “Chidder Nebbi Sacrifice” and reports that it took place in February. At that time, the ceremony is still held in many villages in eastern Anatolia, Iran, and Afghanistan. With the Shiites of Iraq, however, the ceremony is not held on a fixed date, but spontaneously in order to fulfill a vow that has been made.

Sufi interpretations of the Chidr figure

Chidr and the friends of God

In the tradition of the Sufis , Chidr is particularly important because it embodies the Sufi ideal of friendship with God . Thus, Chidr's actions in the Qur'anic narration of Sura 18: 65-82 were used as evidence that in addition to the prophets, the friends of God can also perform miracles. Al-Qushairī (st. 1072) for example writes in a missive about the Sufik:

“What God made to happen through Chidr, the erection of the wall and other wonders and things hidden from Moses that he knew, these are all things that break the habit and that Chidr was distinguished with. And he was not a prophet, just a friend of God. "

According to the Sufi view, Chidr has a supervisory function towards friends of God. It is also considered one of the most important reasons for traveling around the earth. Proof of this notion are the words that are put in the mouth of Chidr in an Andalusian hagiographic work from the 12th century:

“I don't have a permanent place to live on earth. Wherever mine is thought, there I am. I wander through the whole world, plains and mountains, inhabited and uninhabited areas, visit friends of God and visit the pious. I do this without ceasing. "

According to the transoxan scholar al-Hakīm at-Tirmidhī (d. 910), Chidr's close relationship with friends of God is the real reason for his continued existence. In his handbook Sīrat al-Awliyāʾ , which contributed significantly to the development of the theory of friendship with God, he describes Chidr as the one who

“Who walks over the earth, over its land and sea, over its plains and mountains, in search and longing for his own kind. In relation to them (sc. The friends of God) there is a strange story about Chidr. For he had already seen at the very beginning (of creation), when the shares of fate were distributed, how they should be. Then the desire arose in him to still experience her work on earth. He was granted a long life that he will gather with this fellowship for the resurrection. "

Because of such ideas, Chidr is often referred to as the "chief of the friends of God" (naqīb al-awliyāʾ) .

Closely related to the theory of friendship with God is the idea of the so-called Abdāl ("substitutes"), who are supposed to protect the world from harm. Chidr is also closely related to this imaginary group of people. In a report on the kufic pious Kurz ibn Wabra (d. 728) Chidr is even referred to as the head (raʾīs) of the Abdāl. Since Chidr is the one who regularly ensures that when Abdāl dies, their posts are filled immediately, his continued life is a guarantee for the preservation of the earth. The Meccan traditionarian Mujāhid ibn Jabr (d. 722) is quoted as saying that "Chidr lives on until God (at the end of time) inherits the earth and its inhabitants". And the Alexandrian Sufi Abū l-Fath al-ʿAufī (d. 1501) took the view that God used Chidr to preserve the earth (kallafa Allāhu l-Ḫiḍra ḥifẓa l-arḍ) . Such statements give Chidr a unique cosmological meaning.

The idea of the "Chidr of time"

The idea that the friends of God together form a hierarchically ordered community that is led and maintained by Chidr was very widespread. Numerous theories about this hierarchy of saints came into circulation, with different names being given for the individual saints 'ranks: Aqtāb ("Pole", sing. Quṭb ), Abdāl ("substitutes"), Autād ("stakes"), Nujabā' ("noble") ) etc. As soon as members of this hierarchy of saints die, saints from lower ranks are to move up into their offices. At the top of the hierarchy is the Ghauth ("help"), which is used by Chidr himself.

Later, however, theories spread in Sufik that Chidr himself is also included in the cycle of substitutions. Ibn Hajar al-ʿAsqalānī quotes an Alexandrian Sufi of the 13th century as saying:

“When the Chidr dies, then the Ghauth prays at Ishmael's enclosure under the eaves (the Kaaba in Mecca). Then a leaf with his name falls on him, whereupon he becomes Chidr, while the Qu derb of Mecca becomes Ghauth, and so on. "

Chidr is also interchangeable within the framework of this theory and does not represent more than just a spiritual rank. This is how Ibn Hajar gives the view of some Sufis:

"That every time has a Chidr, that he is the head of the friends of God, and whenever a head dies, a head is put in his place after him and is called 'the Chidr' [...] This is not opposed by the fact that he about whom it is narrated that he is the Chidr who was a contemporary of Moses, because he was the Chidr of that time. "

However, there were some Sufis who disagreed with this doctrine, which still has its followers in a similar form, because, in their opinion, it contradicted Chidr's real survival. To those Sufis who the doctrine of the "Khidr of the time" and the "Chidrtum" (al-Ḫiḍriyya) fought as a spiritual rank, belonged to the example of the Schadhiliyya (d. 1309) -Scheich Ibn 'Ata' Allah al-Iskandarani.

Visionary journeys at Chidr's side

While the occurrence Chidrs than in most encounters reports Apparition is described in which the seer the ordinary conscious mind and the normal perception of the surrounding space remain there in Sufi milieu from the 15th century also reports of Khidr-visions. Visions differ from apparitions in that here the soul sees itself transferred to other spaces through supernatural work.

It is noteworthy that the reports about Chidr visions come from very different regions of the Islamic world. The first example can be found in the work Al-Insān al-Kāmil ("The Perfect Man") by ʿAbd al-Karīm al-Jīlī (d. 1428), a Sufi who lived in southern Arabia. It describes how a stranger named Rūh ("spirit") visits a distant region near the North Pole, which is inhabited by the "men of secrecy" (riǧāl al-ġaib) and their king Chidr. The soil of this region is made of white flour, its sky of green emerald. Chidr explains to the stranger in a conversation that only “the perfect man” can enter this world, and also explains to him the various classes of “men of secrecy” who have the greatest knowledge of God and recognize him as absolute ruler.

The idea of a supernatural rapture by Chidr can be found for the first time in the Turkish divan of Zaynīya Sheikh Mehmed Tschelebi Sultan (d. 1494) from the Anatolian city of Eğirdir . The text is also known as Hızır-nāme ("Chidr book"). In it, the poet describes how he travels to the side of all known realms of the upper and lower world. He wandered through the seven heavens, made the acquaintance of the angels and the spirits of the prophets, ascended to the divine throne and visited paradise. Further trips lead him to Mount Qāf , the Wall of Gog and Magog and of course to the source of life. Finally the poet travels with Chidr into the “world of archetypes” and sees the ray of “spacelessness” from which God calls creatures into life.

An undated Javanese manuscript tells how the famous Javanese walī Sunan Kali Jaga (15th century), who allegedly met Chidr in Mecca, entered his intestines through his left ear and took him on a journey through the cosmos. In the 16th century, the Egyptian Sufi ʿAbd al-Wahhāb asch-Schaʿrānī (d. 1565) describes how he traveled with Chidr into seclusion (ġaib) and saw the "source of pure Sharia" there.

Chidr as a symbol of religious authorization

The general popularity of Chidr can be seen in the fact that in the course of Islamic history it was used again and again by various quarters as a symbol of religious authorization.

Chidr as a transmitter of supplications and Dhikr formulas

There are several supplications that are said to have a special magical effect because they were given to a specific person by Chidr. The best known of them is the so-called Duʿā 'Kumail , which ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib is said to have received from Chidr. It is one of the most important supplications in the Twelve Shia and was read publicly at the funeral of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in Tehran.

Various Sufi orders also refer to Chidr to explain the origin of the special Dhikr formulas that characterize their own order. For example, in many works of the Naqshbandīya order it is narrated that the silent dhikr (ḏikr ḫafī) , which is specific to this order, was conveyed by Chidr to the actual founder of the order, ʿAbd al-Chāliq Ghijduwānī (d. 1220) . In a brother order of the Naqschbandīya, the Eastern Turkish Yasawiyya , conversely a loud Dhikr, the so-called “saw-Dhikr” (ḏikr-i arra) , is attributed to Chidr. In the Turkish Celvetiyye , a certain half-standing posture in Dhikr, which is called niṣf-i qiyām and characterizes the order, is associated with Chidr. ʿAzīz Maḥmūd Hüdā'ī (d. 1628), the co-founder of the order, is said to have learned it from Chidr when he visited him during prayer.

Chidr in the legends of buildings and cities

The creation of legends about Chidr often also serves to make spaces sacral. In the previous sections, several places and mosques have been mentioned that are reported to have Chidr appear at them regularly. Such legends, found mainly in works of local historiography, are attempts to give these places an aura of holiness similar to that of Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem.

In some places Chidr was also included in the founding legends of buildings and cities. An example of this is Hagia Sophia , the former main mosque of Istanbul. According to a Persian historical work written in 1480 for the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II , it was Chidr who is said to have asked the Byzantine Emperor Justinian in a dream to build this structure. According to this legend, which is an Islamic adaptation of earlier Byzantine legends, Chidr also sent him the heavenly construction plan and the name for the building and announced his future protection for the building. In later versions of the legend it is reported that Chidr assisted the builders of Hagia Sophia mainly with the construction of the great dome. According to popular belief, the space under the dome is also the place where Chidr should stay regularly. Some Turkish scholars and poets are also said to have met Chidr at this point. The Ottoman travel writer Evliya Çelebi (d. After 1683) claims that at this point "several thousand holy men were fortunate enough to speak with that great prophet."

As with Istanbul, Chidr has also been included in the founding legends of various other Islamic cities. Cities, which in this way have a particularly close relationship with Chidr, are Damascus , Tunis , Samarkand , Herat , Sayram and Edirne . The relationship between Chidr and Samarkand is shown, among other things, by the fact that there is a Chidr mosque of its own, which stands on the ruins of the walls of the predecessor town of Afrasiab . According to local tradition, it is the city's oldest mosque, with Chidr himself laying the foundation stone for it. There are also numerous legends relating Chidr to the other sanctuaries in the city. The main saint of Samarkand is the prophet-led Qutham ibn ʿAbbās. Around his sanctuary, which is still venerated today under the name Shohizinda (“The Living King”), an ensemble of magnificent mausoleums was laid out in the time of the Timurids . The legend tells that Chidr saved Qutham from the infidels during the Islamic siege of Samarkand by kidnapping him through a well into an underground royal palace, where he is said to live on until the end of time. When doubts arose in the time of Timur as to whether Qutham was really still alive, a man is said to have climbed down through the still existing well; he then saw Qutham seated on a throne in his palace, with Chidr and Elias flanking him right and left. Another legend reports that Chidr is said to have a prayer place in the Friday mosque in Samarkand and that with his prayer he once saved Samarkand from the "heresy" of the Shia .

According to a legend recorded by the German orientalist Heinrich Blochmann (d. 1878), Chidr was also involved in the founding of Ahmadabad , which took place in 1411. The reason for the founding of the city was therefore that the Sultan of Gujarat Ahmad Shah I heard from Chidr during an encounter with Chidr, which his Sheikh Ahmad Khattu had mediated, that a flourishing city called Bādānbād had once stood on the Sabarmati River , which suddenly disappeared. When the ruler Chidr asked whether he could build a new city on the site, Chidr replied that he could do so, but the city would only be safe if four people named Ahmad had never skipped the ʿAsr prayer had to get together. A search across the empire found two people who met these requirements. They were supplemented by Ahmad Khattu and the ruler, so that the four people needed were together and the city could be founded.

Legitimation of rule by Chidr

In the premodern times, Chidr also played a certain role in the legitimation of sacred power. In works of Arabic, Persian and Turkish historiography one can find reports of encounters with Chidr, according to which he is said to have predicted the fame of various Muslim rulers and dynasties and announced his protection to them. Such Chidr prophecies, all of which can be interpreted as vaticinia ex eventu , show Chidr, for example, as the protector of the Umayyad caliph ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (r. 717–720), the last Khorezm Shah ruler Jalal ad-Din who led the defensive battle against the Mongols, the Eastern Iranian Ghaznavid dynasty and the Ottomans between 1220 and 1231 .

Chidr also appears in a similar role in the history of Firishta (d. 1620 or later), the court historian of the Indian ʿĀdil-Shāhī dynasty. Here it is told that Chidr Yūsuf, the founder of this dynasty, appeared in a dream while he was still in Persia and asked him to go to India because he would come to power there. The historians of the Central Asian Mangite dynasty, who ruled the Emirate of Bukhara from the middle of the 18th century , also resorted to this model of legitimation. They said that Khidr appeared to the Jawush Bāy, the fifth ancestor of the Mangite rulers, in the form of a simple wanderer and prophesied the rise and reign of his descendants.

Chidr in Shiite apologetics

Chidr also plays an important role in Shiite apologetics . In the account of one of his apparitions, which is preserved in the great traditional collection of Biḥār al-anwār by Muhammad Bāqir al- Majlisī (d. 1111/1700), Chidr declares that he belongs to the party ( šīʿa ) of ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib , So be a Shiite.

In the Twelve Shia , Chidr is particularly important because the generally widespread belief in his continued existence and his invisibility could be used as an argument to defend the Shi'ite doctrine of the continued existence of the hidden Imam Muhammad al-Mahdī . In a report cited by the Shiite scholar Ibn Bābawaih (st. 381/991), it is said of the twelfth imam that he is like Chidr in this community, the resemblance primarily referring to the length of his concealment . There is, however, a similarity between the two in terms of their sudden apparitions. In two stories passed down by al-Majlisī it is reported that people who met the twelfth Imam thought he was Chidr.

According to the traditional Shiite view, Chidr also stays in the vicinity of the Hidden Imam. The eighth Imam ʿAlī ar-Ridā is said to have said that God used Chidr to keep the Mahdī company in his solitude. After the Shiite tradition in 984 a Shiite sheikh has the Mahdi in his hometown Dschamkarān near Qom seen accompanied Chidrs. The Mahdi sat on a throne while Chidr read to him from a book. Today there is a Chidr mosque on a mountain near the Jamkaran Mosque. It is often visited by the residents of Qom and illuminated green at night.

Chidr worship in special Muslim communities and outside of Islam

With Druze, Alawites and Alevis

Chidr is also venerated by the Druze , Syrian Alawites, and Turkish Alevis . The Druze not only venerate Chidr on Carmel, but also on various other shrines in northern Israel. The most important Druze Chidr shrine is located in the place Kafr Yāsīf eleven kilometers northeast of Akko, where a meeting of the Druze clergy takes place annually on January 25th. It was only built at the end of the 19th century. The Druze of the Golan Heights have another Chidr sanctuary in Banyas at the source of the Banyas River at the foot of the Hermon Mountains above an ancient Pan sanctuary. The Druze image of Chidr has some differences compared to the Muslim image of Chidr. The Druze clearly identify Khidr with Elias, a view that in the realm of Islam was always only a minor opinion. Furthermore, with them Chidr has the Kunya Abū Ibrāhīm, not Abū l-ʿAbbās.

The Syrian Alawites built chidr in numerous places in Jebel Ansariye , Hatay and Cilicia . In Cilicia alone there are 25 Alawite Chidr sanctuaries. Until the middle of the 20th century there was a custom in Jebel Ansariye to dedicate girls to the Chidr. About Sulaimān Murschid , who founded a revival movement among the Alawites in the 1920s, which continues to this day as Murschidīya, it is said that Chidr appeared to him and called him on a visionary journey into heaven as a prophet, who reminded the Alawites of their religious duties should. To this day, Chidr plays a very important role among the Murshidites. Sādschī al-Murschid, who headed the Murschidīya as Imam until 1998, described Chidr in an interview in 1995 as the “grace of God” (luṭf Allaah) and declared that he was higher than all prophets.

The Turkish Alevis celebrate the Hıdrellez festival on May 6th and hold a three-day Chidr fast (Hızır orucu) in mid-February , usually from Tuesday to Thursday. According to an Alevi tradition, this goes back to the fact that once ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib and his wife Fātima bint Muhammad fasted for three days for the recovery of their two sons al-Hasan and al-Husain , during which they visited Chidr every evening in the form of a poor hungry man . The three-day fast is performed in memory of this event. At the end of the fast, the Hızır Lokması (“Chidr Bite”) is prepared and a Hızır- Cem is held. In the state treaty concluded in 2012 between the City of Hamburg and the Alevi Community of Germany , the Hızır Lokması is set for February 16 and has been recognized as a religious holiday within the meaning of the Hamburg Public Holidays Act.

With Yazidis and Zoroastrians

With the Yazidis of Iraq, Chidr and Elias have merged as usual in Iraq to form the double saint Chidr-Elias. On the first Thursday in February, the Yazidis hold a Chidir Liyās festival, which is in the tradition of the Iranian Chidr days of the Tschilla cycle. Large celebrations take place on this day near the village of Bāʿadhra in northern Iraq. In addition, special hair offerings are made. Similar to the Alevis, the festival is preceded by a three-day fast. During this fast, total abstinence is maintained even at night. The Yazidis also often make pilgrimages to the Mar Behnam monastery , which they venerate as the Chidr Elias shrine.

The Zoroastrians in Iran identify Chidr mainly with their deity Sorush, but also with Bahram and more . There are a total of seven Zoroastrian Chidr shrines in Iran. All of these shrines are, or until recently were, on the edge of fields. Chidr is seen by the Zoroastrians primarily as the patron saint of the fields.

With Hindus and Sikhs

On the Indian subcontinent , Chidr is also worshiped by Hindus . The British colonial official HA Rose noted in 1919 that Khwaja Khizr was a Hindu water god in western Punjab , who was worshiped by lighting small lights at springs and eating Brahmins or by placing a small raft with holy grass and a light on it in the village pond. An overlap between Islamic and Hindu ideas occurs above all on the Indus, where Chidr is venerated by both Muslims and Hindus under the name Jinda Pir (from Pers. Zinda pīr "Living Pīr ").

The Chidr sanctuary on the Indus island near Rohri in Sindh was also maintained jointly by Hindus and Muslims in the 19th century. Every year in March and April several thousand Muslims and Hindus from all parts of Sindh came to the festival of the sanctuary. But then a dispute broke out over the property rights to the sanctuary, which was decided by the British authorities at the turn of the 20th century in favor of the Muslims. The Hindus then withdrew and built a new temple for Zinda Pir in Sukkur on the opposite side of the Indus. This temple continues to this day. The Chidr sanctuary on the Indus Island was destroyed by an Indus flood in 1956, but has since been rebuilt in a more modest form.

Chidr also plays a certain role in Sikhism , because in the legends about Guru Nanak (d. 1539), the founder of this religion, it is said that he was visited by Chidr after his vocation , who taught him all worldly knowledge. One version of the legend recorded in the early 19th century says that the teaching by Chidr took place when Guru Nanak was spending three days in a pond. According to another legend, followers of Guru Nanak believed that their master worshiped the river god Khwaja Khizr and received his power from him. After a while they met Khwaja Khizr himself in the form of a man with a fish in his hand. He informed them that he was not receiving offerings from the Guru, but that he was making such offerings for the Guru and receiving his power from him.

The equation of Chidr with St. George

In Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan, Chidr is identified with Saint George by Christians and many Muslims . Both figures are so much fused in popular tradition that their names are taken as synonyms . One of the most famous places where the Christian saint is venerated under the name al-Chidr is the Greek Orthodox Church of Saint George in the village of al-Chadir near Bethlehem , which is exclusively inhabited by Muslims. The place is mentioned as a Chidr-Maqām by ʿAbd al-Ghanī an-Nābulusī at the end of the 17th century . Until the middle of the 20th century, the Arab residents of the area brought their sick here because they hoped the icon of the saint inside the church would heal them. The insane were chained to a wire connected to the icon. In this way it was believed that the blessing power of the sacred could work on them. To this day, the oil from the oil lamps that burned down near the icon is considered to be beneficial, and sacrificial animals are slaughtered in the courtyard in fulfillment of vows . On May 5th and 6th, St. George's Day of the Eastern Church, there is a festival at the church, which is attended by both Christians and Muslims.

Other places with St. George's churches where St. George is equated with Chidr are Izraʿ and the St. George's Monastery near Homs in Syria, as-Salt in Jordan and Lod in Israel, where the tomb of St. George is also said to be. In Lod, the Muslims have built a mosque right next to St. George's Church, which is also known as the Chidr Mosque. The Chidr shrine in Beirut also originally goes back to a St. George's church. It was only finally converted into an Islamic sanctuary with a mosque in 1661. The Chidr sanctuary with the two oaks in the grove of Mahis west of Amman is venerated not only by Muslims but also by Christians, and inside it are pictures of St. George.

Inner Islamic criticism of Khidr piety

The various forms of worshiping Chidr have not been accepted without contradiction by all Muslim scholars. From the 10th century onwards, various scholars tried to show the incompatibility of the Chidr faith with the foundations of the Islamic faith. This defensive movement was initially supported primarily by representatives of the Zahirite and Hanbali schools of law. Later, however, scholars from the Shafiite school of law also formulated criticism of Khidr piety. Other scholars, on the other hand, defended the Chidr belief, so that a wide-ranging debate began that lasted for centuries and is still not completely over. Numerous Arabic treatises on Khidr were also written in the course of this debate .

The criticism of the worship of Chidr mainly concerned the following two points:

Chidr - not only friend of God, but also prophet

On the one hand, they turned against the view held by many Sufis that Chidr was not a prophet , but merely a friend of God. The point was of great relevance, because the servant of the Qur'anic tale identified with Chidr had acted against the law with his deeds (destruction of a ship, killing of a boy) according to the general opinion, and various Sufis deduced from this that they too, as friends of God, had transgressed the Sharia is permitted. Legal scholars such as the Shafiit Ibn Kathīr (d. 1373) tried to break this antinomic interpretation by defining Chidr as a prophet and pointing out that he had committed his deeds as such and not as a friend of God. The invocation of Chidr to justify violations of Sharia law was regarded by Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhāb (d. 1792) as such a gross offense that he included it in his list of Nawāqid al-Islām . The ninth item on this list reads: "Anyone who believes that some people are allowed to break the Sharia, as Chidr was allowed to break the Sharia of Moses, is an unbeliever."

However, there were also Sufi-oriented scholars who assumed that Chidr was a prophet. The Moroccan Sufi Muhammad al-Mahdī al-Fāsī (d. 1653), in his commentary Maṭāliʿ al-masarrāt, reports the view that Chidr was sent as a prophet to a people on the sea called Banū Kināna . This opinion is said to have shared by al-Jazūlī (d. 1465), the author of the well-known prayer collection Dalāʾl al-ḫairāt , which al-Fāsī commented on in his work.

The controversy over Chidr's continued life

The second point contested by the opponents of Chidr piety was belief in Chidr's continued life. Well-known Arab scholars who have opposed this idea included the Baghdad hadith scholar Abū l-Husain al-Munādī (d. 947), the Andalusian Zahirit Ibn Hazm (d. 1064) and the Hanbalit Ibn al-Jschauzī (died 1200). The latter has also written his own treatise on this question, which is only preserved through quotations in later works by Ibn Qaiyim al-Jschauzīya (d. 1350) and Ibn Hajar al-ʿAsqalānī (d. 1449).

Chidr's continued life, however, was defended by the Malikite Ibn Abī Zaid al-Qairawānī (d. 996), the two Shafiites an-Nawawī (d. 1277) and Jalāl ad-Dīn as-Suyūtī (d. 1505) and the Meccan Hanafit ʿAlī al -Qārī (d. 1606). Al-Qari has written his own Chidr treatise, in which he dealt with and refuted Ibn al-Jawzi's arguments individually. The scholar Muhammad ibn ʿAun ad-Dīn al-Mausilī, who lives in Baghdad, also wrote a pamphlet to prove Chidr's continued life. In this text, which he completed around 1750, he also rejected the view of the Anatolian Sufi Sadr ad-Dīn al-Qūnawī (d. 1274), who had taught that Chidr only in the world of images ( ʿālam al-miṯāl ) be seen.

Some scholars deliberately left the question of Chidr's survival open. The Ottoman provincial scholar Abū Saʿīd al-Chādimī (d. 1762), for example, who wrote a short treatise on the question in which he deals with the argument between two contemporary scholars about Chidr's continued life, declared the question to be undecided and recommended it to his students and readers Reluctance. The Baghdad scholar Shihāb ad-Dīn al-Ālūsī (d. 1854), who devoted a very detailed section in his Koran commentary to Rūḥ al-ma widānī in the treatment of Sura 18 Chidr, also discussed the entire doctrine of his continued existence, but gave himself no judgment on it.

One of the arguments that was most frequently put forward against Chidr's continued life was Quran verse 21:34, in which, addressed to Mohammed, it says: "And we have not given anyone before you everlasting life." Scholars convinced of Chidr's continued life were, like Ibn Abī Zaid al-Qairawānī, saw in this verse no contradiction to Chidr's continued life. They pointed out that there is a great difference between eternal life (ḫulūd) and continued life until the day of resurrection. While eternal life, which is spoken of in the Koran, also includes continued life in the hereafter, Chidr like Iblīs dies as soon as the trumpet is blown for the first time at the Last Judgment.