Richard the Lionheart

Richard the Lionheart (French Richard Coeur de Lion , English Richard the Lionheart * 8. September 1157 in Oxford , † 6. April 1199 in Chalus ) was from 1189 until his death as I. Richard King of England .

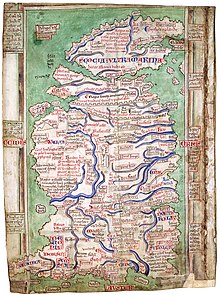

Richard's years before he took office were overshadowed by conflicts with his father Henry II and with his brothers over the inheritance. Only through the death of his older brother Heinrich and an alliance with the French King Philip II was he able to secure the English royal throne. His inherited rulership complex, the " Angevin Empire ", included England, Normandy and large parts of western France. As ruler, Richard had to hold together an economically and culturally very heterogeneous conglomerate of different territories. During his reign he stayed in England a total of only six months.

On a crusade undertaken together with Philip, which is now counted as the Third Crusade , Richard conquered Cyprus in 1191 . Then he crossed over to the Holy Land , where he successfully ended the two-year siege of Acon . However, the company's actual goal, the retaking of Jerusalem , could not be achieved. Even during the crusade, Richard and the French king fell apart. During his return by land, Richard was arrested in 1192 by the Austrian Duke Leopold V , with whom he had also fallen out, and Emperor Heinrich VI. to hand over. Thus Leopold retaliated for a violation of the honor ( honor ), inflicted during the Crusade him the English king. Richard spent around 14 months in captivity in the Upper Rhine region . The French king took advantage of this and conquered a number of castles and areas. For Richard's release, the enormous sum of 100,000 silver marks had to be obtained from all over the Angevin Empire through property sales and special taxation. Heinrich VI used the proceeds. mainly to finance the conquest of Sicily . After his release, Richard tried to recapture the territories occupied by Philip II. He died childless on April 6, 1199 during the siege of Cabrol near Limoges .

Richard's image as the ideal knight and energetic king has been glorified until the present day in literature, music and the performing arts. The formation of contemporary legends was mainly inspired by the Third Crusade. In the 16th century, this material was interwoven with the stories of the English thief Robin Hood . Historians in Protestant Great Britain from the 18th century onwards came to a completely different assessment; for them Richard was an irresponsible and selfish monarch who had neglected the island kingdom. In the wider public, however, he was considered a symbol of national greatness from the 19th century. The more recent research tries to give a more differentiated picture, whereby the tendency towards a positive assessment predominates.

Life

Origin and youth

Richard the Lionheart came from the noble family of the Plantagenets . However, this name was not used as a dynasty name until the 15th century, for the first time in 1460 by Duke Richard of York . It goes back to King Richard's grandfather Gottfried V , who was Count of Anjou , Tours and Maine . According to legend, he wore a gorse bush (planta genista) as a crest or planted gorse bushes in his lands to protect himself from the hunt.

The English King Henry I died in 1135 without a male heir. Therefore his daughter Mathilde should follow him to the throne. However, an opposition formed against her and her husband Gottfried V, which made Stefan von Blois king. The conflict led to civil war . In this tense situation, the future King Heinrich II was born on March 5, 1135, the son of Mathilde and Gottfried. Through his parents he was not only entitled to the Duchy of Normandy and the County of Anjou , but also to the English throne. In May 1152 he married Eleanor of Aquitaine . She had inherited the wealthy duchy of Aquitaine in southwestern France from her father Wilhelm X. Eleanor had married the son of the French king in July 1137 and was thereby crowned Queen of France. In 1152 she separated from her royal husband Louis VII with ecclesiastical approval . By marrying Eleonore, Richard's father Heinrich became one of the most powerful princes in Europe and the greatest rival of the French king. In May 1153, the Civil War ended with the Winchester Treaty . Stefan von Blois, whose health was weakened, remained king until the end of his life, but accepted Mathilde's son, later Henry II, as his successor.

After Stefan's death in October 1154, Heinrich was elected King of England two months later. He was crowned Eleanor at Westminster. The marriage resulted in five sons ( Wilhelm , Heinrich , Richard, Gottfried and Johann ) and three daughters ( Eleonore , Johanna and Mathilde ). As a third-born son, Richard was initially not intended for the succession to the throne. Henry II entrusted the upbringing of his sons to his chancellor Thomas Becket , at whose court the children were taught by various cultivated clergy. So Richard was thoroughly trained in the Latin language. Heinrich tried to influence the southern French region through marriage alliances. In 1159 Richard was engaged to the daughter of Raimund Berengar IV , Count of Barcelona . In this way, Heinrich wanted to win an ally against the county of Toulouse . However, the planned marriage did not materialize because Raimund died unexpectedly in 1162. Richard was around his mother. He traveled with her to Normandy in May 1165. Up to 1170 no information has been passed on about his further training or his whereabouts. He was traveling with his mother in the south of France in 1171. He got to know the language and music of Aquitaine. His father gave him the county of Poitou at an early age and gave him the administration of the Duchy of Aquitaine.

Fight for succession and coronation

Henry II decided to pass on the Angevin Empire as an undivided inheritance. He envisaged his eldest surviving son Heinrich - Wilhelm had died in 1156 - as his successor in the royal dignity. In January 1169 he met in Montmirail for peace negotiations with the French King Louis VII . There he renewed the feudal homage for the mainland property on January 6, 1169 and at the same time had his sons Heinrich and Richard recognized as heirs of the French fiefs of Ludwig. The eldest son Heinrich took the oath of fief to Ludwig for Normandy, Anjou and Maine, Richard for Aquitaine. Gottfried was confirmed as Duke of Brittany and received the county of Mortain . Johann was initially left without equipment. Richard came of age at the age of 14.

In June 1170 Heinrich had his son of the same name crowned co-king. In June 1172, at the age of 14, Richard was solemnly invested as Duke of Aquitaine in the Abbey of St. Hilaire in Poitiers . In spring 1173 Heinrich promised his youngest son Johann the castles of Chinon , Loudun and Mirebeau in Normandy. Heinrich the Younger saw this as an impairment of his rights. This was the cause of a revolt by the king's sons against their father. Because of the young age of Princes Richard and Gottfried, it can be assumed that they acted under the influence of their mother Eleanor. A strong will to power and the restriction of their rights in the Duchy of Aquitaine come into consideration as their own motives. Richard besieged towns loyal to the king like La Rochelle in the spring and summer of 1174 , but in September 1174 he had to surrender to his father. On September 29, 1174 there was a settlement in Montlouis near Tours . Richard received half the income from Aquitaine and two residences. The sons had their own income and land, but remained without influence on the politics of their royal father. Also in 1174 Richard's marriage to Alice , the sister of Philip II, who was probably born in 1170, was agreed. She was sent to the court of Henry II and was to be prepared there for her role as Richard's future wife. The king wanted to supply the youngest son John with Aquitaine, but Richard refused to leave the duchy to his brother.

As Duke of Aquitaine, it fell to him to take action against the nobles opposing there. The focus was on the siege and destruction of a large number of castles. In the only field battle at the end of May 1176 he defeated Vulgrin von Aimar. By the end of 1176 he was able to take Aixe and Molineuf , among others . In January 1177 he conquered Dax and Bayonne . But as early as 1178 new revolts broke out. In May 1179 Richard took the fortress Taillebourg, which was considered impregnable . It was mainly because of this that he gained a reputation as a brilliant warlord. With the capture of the Taillebourg fortress, Richard managed to get the opponents to temporarily stop their resistance. According to Dieter Berg, Richard limited himself to military action against rebel barons and failed to seek a political solution. The sources give no indication that Richard built up a clientele of followers loyal to the duke among the greats of his territories. Nor did he undertake any reforms in the administrative or legal system. From the summer of 1179 to the summer of 1181 nothing is known about Richard's stays. In May 1182, negotiations took place in Grandmont in La Marche in the presence of Henry II . Richard was hated as a duke by the Counts of Aquitaine because of his brutal behavior and constant violations of the law. English chroniclers took up Richard's personal misconduct. After Roger of Howden , Richard made the wives, daughters, and relatives of the subjects his concubines. After he had satisfied his lust, he then passed it on to his soldiers. The military clashes continued in the period that followed.

After the death of the eldest son Heinrich in June 1183, the line of succession was completely open again. When Heinrich II reached an agreement with Richard in 1185, Johann remained “without land”. A year later Gottfried died at a tournament in Paris. However, Henry II refused to recognize Richard as the sole heir and continued to demand that he give up Aquitaine for Johann Ohneland.

To avert disinheritance in favor of his brother John, Richard allied himself with the French king and visited Philip II in Paris in June 1187. The Capetian fed not only with Richard from the same bowl, but both also shared the bed. Eating and sleeping together in a bed were common rituals in the culture of the high medieval nobility , with which friendship and trust were visualized. The demonstratively staged closeness was interpreted in the 20th century as a sign of homosexuality. In recent research, however, such behaviors are interpreted as demonstrative gestures of solidarity and trust. With the alliance, Richard tried to put pressure on his father to recognize him as an heir. He was less able to realize his hopes for the Angevin legacy through his father than through the Capetian. On November 18, 1188 Richard demonstratively performed the homagium for Normandy and Aquitaine. The French king demanded that Henry induce the greats of England and those of the mainland possessions to swear the feudal oath to Richard as heir. Heinrich refused to finally recognize Richard as the heir to his kingdom. There was an open conflict. On July 4, 1189 Heinrich had to pay homagium for his land possessions in the Treaty of Azay-le-Rideau , give a firm promise for the marriage between Richard and Alice after the crusade, to which he had committed himself at the end of 1187, and Richard as sole one Recognize heirs. He also had to pay 20,000 marks as compensation. Richard's father died in Chinon two days later . On July 20, 1189 Richard could officially take over the rule of Normandy in Rouen . At a meeting with the French king between Chaumont-en-Vexin and Trier, he recognized the Colombières peace treaty of July 4, 1189. He also agreed to additional war indemnities and an early wedding to Alice.

Richard secured the loyalty of important barons, including the knight Maurice von Craon and Wilhelm Marshal . For his coronation he came to England for four months. He arrived in Portsmouth on August 13th . He tried to improve his reputation first with a great triumphal procession through England. On September 3, Richard was anointed in Westminster in an elaborate ceremony by Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury and then crowned. At the banquet that followed, the counts and barons took on tasks according to their court offices. Citizens from London and Winchester served in the basement and kitchen. Almost all the greats of the Angevin empire had appeared for the coronation. In connection with the coronation, there were persecutions of the Jews, which later escalated into pogroms because of inadequate punitive measures after the king had set out for the Holy Land.

Third crusade

After the defeat of the king of Jerusalem, Guido von Lusignan , against Saladin on July 4, 1187 in the battle of Hattin and the capture of Jerusalem on October 2, 1187, Pope Gregory VIII called for a crusade on October 29, 1187 . Richard committed himself to participate in the crusade in November 1187. He was personally moved by the crusade movement. His mother had participated in the Second Crusade from 1147 to 1149 . In addition, Guido von Lusignan was Richard's feudal man for his Angevin property. The first army set out in May 1187 under the leadership of Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. While crossing the river Göksu, Friedrich drowned on June 10, 1190. The majority of his army then returned home. The remaining crusaders were led by the son of the late emperor, Friedrich von Schwaben . However, he succumbed to an illness on January 20, 1191. From then on, the highest ranking crusader was the Austrian Duke Leopold V. The other two main armies were then to be led by King Philip II of France and Richard the Lionheart. Long before the arrival of the two Western European monarchs, Leopold was involved in the siege of Acon . However, he only had few resources and could hardly achieve anything.

Preparations

After Richard was crowned King of England, the crusade was a top priority. For its implementation, the securing of rule during his absence and the financing of the company were decisive. Contemporary chroniclers complained that everything was for sale to the king - offices, baronies, counties, sheriff's districts, castles, cities, lands. After Dieter Berg , Richard focused primarily on continuity when awarding offices. When filling the top positions, above all the experienced functionaries of his father were taken into account. In addition to Wilhelm Longchamp , a confidante of Richard, Hugo du Puiset, an experienced follower of Heinrich, was appointed chief justiciar . Richard Fitz Neal retained his office of treasurer . The continuity also continued in the field of earldoms . Only the king brother John for Gloucester, Roger Bigod for Norfolk and Hugo du Puiset for Northumberland and King William of Scotland for Huntingdon were newly appointed .

Within a few months, Richard was able to raise enormous sums of money and transport ships for the crusade in Regnum, England . In 1190, the year of preparation for the crusade, there was a significant increase in the revenue of the Treasury. Important barons could break their crusade vows for a fee. In addition, there were one-off payments from barons in the event of marriage or inheritance and special payments from English Jews for the royal protection of Jews. According to the chronicler Richard von Devizes, Richard would even have sold London for the Crusade if he had found a buyer for it. He was able to initially expand the fleet to 45 ships through activities at the Cinque Ports , Shoreham and Southampton and then expand it to over 200 through purchase or rental.

Parallel to the preparations for the Crusade, Richard pursued a marital connection with Berengaria of Navarre . The desired marriage alliance was part of his Aquitaine policy. He had already made contact with the royal court of Navarre as early as 1188 . The marriage with Berengaria corresponded better to his foreign policy goals than the connection with the Capetian princess Alice. The desired marriage with Berengaria should perhaps also provide for a descendant and thereby ensure the settlement of the succession in view of the dangerous crusade enterprise. With Berengaria's father Sancho VI. of Navarre , the last Iberian monarch, whose territories adjoined the Angevin possessions, was bound to Richard. To Alfonso II. Of Aragon Richard had built up for some time good contacts to the Castilian court he had through the marriage of his sister Eleanor with Alfonso VIII. Kinship. By cultivating relations with the Iberian rulers, Richard also wanted to prevent possible attacks from their side on the Aquitanian duchy.

travel

On December 30, 1189 and March 16, 1190 Richard met for talks with the French king in Nonancourt and Dreux , respectively . The two rulers took an oath not to wage war until after returning from the crusade they had been peaceful in their realms for forty days. In the event that one of them should die during the operation, it was planned that the other would take over the deceased's war chest and troops. On July 4, 1190, the kings broke up in Vézelay , because neither trusted the other enough to want to leave before him. Due to the supply situation, the two armies could not move together.

Richard arrived in Sicily on September 23, 1190. He staged his entry into the port of Messina as a solemn event, whereas hardly anyone had paid much attention to the arrival of the French king a week before. He wintered in Sicily. There, after King William II of Sicily , Richard's brother-in-law, died childless, succession battles broke out. The great had raised Tankred of Lecce , who came from the family of the Norman kings of Sicily , but was born out of wedlock. On January 18, 1190 he was crowned king by Archbishop Walter of Palermo . Tankred had arrested Richard's sister Johanna, Wilhelm II's widow, and denied her widowhood . Conflicts arose between the English and French crusaders and the local population. Richard then conquered Messina. Under the impression of this event, Tankred released Johanna immediately and proposed 20,000 ounces of gold to the English king as compensation for the Wittum. He also offered to marry one of his daughters to Richard's nephew Arthur of Brittany and pay a dowry of 20,000 ounces of gold. Richard agreed to support Tankred's kingship in October 1190.

In the event of childlessness, Richard appointed his nephew Arthur of Brittany as heir in Messina in October 1190. The three-year-old Arthur was therefore also intended as a potential heir to the throne in England. The loser of this regulation was Richard's brother Johann, who saw himself as the sole heir and thus heir to the throne in England if Richard was childless. After these agreements became known, Johann used Richard's absence to attempt to assert his own claims to the throne on the island.

Richard had sent his mother Eleanor to the Kingdom of Navarre in parallel to his preparations for the crusade to pursue his marriage project there. He explained to the French king that he could not marry Alice. His father Heinrich II is known for his extramarital affairs. Alice was Heinrich's lover and had a son by him. Canon law does not allow him to marry a woman who has had intercourse with his own father. This accusation represented a great humiliation for the Capetian. Richard paid Philip 10,000 silver marks for the termination of the marriage vows. The French king left Messina in a hurry on March 30th for Outremer , just a few hours before Eleonores and Berengaria's arrival - otherwise he might have had to attend the wedding. He arrived in Acre on April 20th. However, Lent prevented a marriage in Sicily. Richard left Messina on April 10, 1191 with a fleet of more than 200 ships. Some ships went off course in a violent storm and were stranded on the coast of Cyprus, including Johanna and Berengaria's ship. There they were disarmed by the Cypriots and placed under guard.

In April 1191 Richard turned against Cyprus, where six years ago a scion of the Comnen dynasty overthrown in Byzantium in 1185 , Isaak Komnenos , had gained independence as emperor. Within a month Richard was able to conquer the island and take Isaac prisoner. He took into account the rank of the prisoner, because imprisonment in chains was considered a special humiliation. According to various sources, Isaac only surrendered on the condition that he was not put on iron chains. Richard stuck to it and put silver chains on him instead of the usual iron chains. There is no consensus among researchers about the reason for the conquest of Cyprus. According to an older research opinion, the conquest was a consequence of chance events. According to John Gillingham, however, Richard pursued a strategic plan drawn up by the winter of 1190/91 at the latest when he captured Cyprus. Richard had intended to secure the endangered position of the Crusaders in the Holy Land by a safe rear base. According to Dieter Berg , the crusaders simply wanted to take booty and secure strategically important territory. According to Oliver Schmitt, the thesis of a previously drawn up plan cannot be proven in the sources. According to Michael Markowski, Richard was less concerned with long-term strategic goals than with the identification of himself as the ideal type of Western knight.

In Limassol Richard married his fiancée Berengaria of Navarre on May 12, 1191 . As queen, Berengaria was of no particular importance for the rest of Richard's reign. Richard left Cyprus in early June 1191. He left only a very small contingent on the island. With Richard of Camville and Robert of Turnham he had installed two of his commanders there as governors. A few weeks later, Cyprus was sold to the Knights Templar for 100,000 gold dinars . Richard's conquest was momentous, as Cyprus remained under Latin rule for nearly four centuries.

Course of the crusade in the Holy Land

Richard used the booty from Cyprus to extend his campaign in the Holy Land. On June 8, 1191, his fleet arrived in front of the city of Acre, which was besieged by the Crusaders . Philip had already arrived there in April 1191, but he had not been able to achieve military success. The siege of the city had lasted almost two years, but significant progress was not made until Richard arrived. On July 12, 1191, about five weeks after his navy arrived, Acre surrendered.

When Richard entered the conquered city, however, he made the Austrian duke a permanent enemy because of a defamation. Honor was of the utmost importance in dealing with the protagonists; Honor and a sense of honor played a central role in the ethos and mentality of the nobility, and it was imperative that consideration be given to them. Honor was not understood as a moral category; What was meant was the respect that a person could expect based on their rank and social position. According to the sources, Leopold placed his flag in a prominent place in the conquered city, with which he wanted to demonstrate his claim to booty and his rank. However, this flag was torn down by Richard, or at least with his tolerance, and trampled in the dirt. According to another tradition, Leopold erected his tent too close to that of the king, whereupon Richard collapsed the duke's tent on his own initiative. By being close to the highest ranking, Leopold wanted to publicly demonstrate and maintain his position in the political balance of power. In any case, the resentment was so massive that Leopold and Richard no longer communicated personally, but only through intermediaries. Richard gave Leopold no satisfaction. The Austrian duke left humiliated and without spoil for his homeland. According to John Gillingham, Leopold's claim to booty was out of proportion to his actual share in the conquest of Acre. Gillingham is thus following an assessment that Heinrich Fichtenau had already made in 1966.

Thousands of Accon's defenders were held prisoner for the implementation of the surrender agreement. Philip II returned to his homeland at the end of July 1191. The French king named the climate that was not conducive to his health as the reason for his departure. After the childless death of Philip I of Alsace, he also had to take care of the succession in his county of Flanders . However, research tends to assume that he withdrew because of the conflicts with the English king. Richard was henceforth the unrestricted leader of the crusader contingents. When the payment of the ransom for the approximately 3,000 Muslim prisoners was delayed after the conquest of Acon, Richard had them executed on August 20, 1191. Because of this, he was described as ruthless and brutal by later historians. In recent research, however, greater attention is paid to the fact that this procedure corresponded to the customs of the West at the time.

While advancing along the coast Richard won a victory over Saladin's army in the Battle of Arsuf on September 7, 1191, but he could not destroy it. His forays on Jerusalem in January and June 1192 were therefore in vain. At the same time, there was always diplomatic contact with Saladin. Richard proposed marriage between Saladin's brother Malik al Adil and his sister Johanna . The coastal cities between Acre and Ascalon were discussed as dowries. Because of the religious difference, however, both Johanna and al Adil refused to join. In April 1192 was Conrad of Montferrat , a contender for the throne of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and opponents King Guido de Lusignan, of assassins murdered. Richard, who had supported Guido, agreed to a compromise: Guido was transferred to the rule of Cyprus and Count Heinrich von der Champagne , Richard's nephew, was elected the new King of Jerusalem .

At the end of July 1192, Saladin took Jaffa after a brief siege . Richard, who rushed up quickly, was able to recapture the city in a coup d'état at the beginning of August 1192 and drive Saladin out in the subsequent battle of Jaffa . In the meantime Richard was ill. Given the limited available military forces and the local balance of power, he decided to end the crusade with a ceasefire. He also wanted to return home out of fear of losing territory in northern France. On September 2, 1192, Richard and Saladin signed the Treaty of Ramla, the armistice for three years and eight months. Askalon , Darum and Gaza were returned to the Muslims. The coastal cities from Jaffa to Tire were left to the Christians. Jerusalem remained under Saladin's sole control, but Christian pilgrims were allowed access to the city. Since the Christians had to forego the reconquest of the Holy City, the crusade had missed its real goal. According to Dieter Berg , Richard was primarily responsible for the failure. The army was weakened by the withdrawal of the French king because of the conflicts with Richard. Berg considers it incomprehensible that Richard nevertheless led the army twice outside the walls of Jerusalem without being able to dare to attack. John Gillingham disagrees, countering the unfavorable judgments of later historians that Richard was honored by his contemporaries as an important crusader.

On October 9, 1192 Richard started his return journey to Europe on a ship. His disease 1191/92, which is described as major or medius hemitritaeus , may have been a form of malaria tertiana .

Captivity by Emperor Heinrich VI.

On his return journey after a shipwreck, Richard was forced to take the land route via the Roman-German Empire. Fearing retaliation from his intimate enemy Duke Leopold V of Austria, he traveled in disguise and with only a few companions, including Baldwin of Béthune , Philip of Poitiers , Wilhelm de l'Etang and the chaplain Anselm. His goal was Bavaria, the sphere of influence of Henry the Lion . Even the compulsion to disguise was shameful in a ranked medieval society where honor and status were publicly demonstrated. Dieter Berg judges Richard's disguise as a "strange and at the same time amateurish game of hide-and-seek". It is unclear why Richard did not openly seek safe conduct as a crusader. Count Meinhard von Görz became aware of the tour group at the beginning of December 1192 and recognized the king, but initially he was able to escape. His escape ended a few days before Christmas 1192 in Duke Leopold's territory. The contradicting statements of the sources do not illuminate the specific circumstances of the ensuing arrest. However, all sources agree that it was Leopold's revenge for the defamation suffered. The chronicle of Otto von Freising offers the most detailed description with the continuation of Otto von St. Blasien . She is full of malice about what has happened. According to her description, Richard was disguised as a simple pilgrim and was laughed at by Leopold when he was able to capture him in Erdberg near Vienna while roasting chicken in a shabby dwelling that was not in keeping with his class. His need for representation became his undoing. As a simple servant, he roasted a chicken, but forgot to pull a valuable ring off his finger. The English chroniclers, on the other hand, based themselves on the model of chivalrous action. They stressed that Richard had behaved with dignity as king even in this difficult situation. He was surprised in his sleep, had only wanted to hand over his sword to the Duke, did not allow himself to be intimidated by the Duke's overwhelming power, or let himself be taken prisoner personally by the Duke. Many clergy in Europe viewed the capture of a crusader as a grave sin. For the chroniclers close to the Austrian duke it was justified revenge for the defamation suffered in Acre.

The English tradition, close to the court, reports quite extensively on the events between captivity and release, but the German sources are almost completely silent. John Gillingham interprets the silence as a sign that the captivity of a Crusader under the protection of the Church was considered unworthy and detrimental to Leopold's honor. According to Knut Görich , the silence is also due to the fact that there were no historians close to the court among the German chroniclers.

Richard was handed over to Hadmar II von Kuenring , one of the most powerful ministerials of the Babenberg duke , and imprisoned at Dürnstein Castle near Krems on the Danube . As early as December 28, 1192, the emperor informed the French King Philip II of the capture of Richard. He informed him that he had now arrested the "enemy of ours and the troublemaker of your empire" (inimicus imperii nostri, et turbator regni tui) . Richard's capture caused indignation at the papal curia. Pope Celestine III demanded the release and threatened with excommunication , since Richard as a crusader was under the protection of the church and had the right to return freely. Leopold was from Pope Celestine III. excommunicated in June 1194.

Emperor Heinrich VI. tried to take political advantage of Richard's captivity. He was under political pressure because of the murder of Liège Bishop Albert von Löwen , because he was charged with the failure to punish the murderers. Richard had good connections to the north German prince opposition, which could possibly be persuaded to moderate the Emperor Heinrich in return for his release. Heinrich began negotiations with Leopold in the spring of 1193 about the extradition of the English king. On January 6, 1193 Richard was transferred to Regensburg as a prisoner and presented to the emperor there. An agreement between Leopold and Heinrich VI. However, it did not take place, whereupon the Austrian Duke brought Richard back.

Richard was able to act to a limited extent despite the imprisonment. Legal documents could also be drawn up during this period. Initially only letters and writs (royal decrees) were written. After successful release negotiations, Chancellor Wilhelm von Longchamp joined Richard's personal retinue from the summer of 1193 . Since then, at the latest, royal documents have been drawn up again. From his captivity Richard operated the election of Hubert Walter as Archbishop of Canterbury . As legal counsel, Walter ensured rule during the king's absence.

When Johann Ohneland found out about his brother Richard's imprisonment, he immediately sought the support of Philip II in Paris. In January 1193, he went to his court. In this way he wanted to secure the inheritance. He was enfeoffed with Normandy by the French king. Philip supported Johann's ambitions for the English throne, and the latter made him a fief. In addition, Philip offered his protection to dissatisfied nobles in the English mainland possessions.

Heinrich and Leopold sealed an agreement in Würzburg on the conditions for release. In the Würzburg Treaty of February 14, 1193, 100,000 marks of pure silver were set as ransom, half each to Leopold and Heinrich VI. In addition, Richard should commit himself to support the next Sicilian campaign of the emperor. In March 1193, Heinrich threw on the court day in Speyer before the princes to the English king numerous crimes, including the murder of Conrad of Montferrat, a vassal of the empire, which he had caused. Richard had arrested a relative of the emperor, Isaac of Cyprus, and sold his land. He had reviled the flag of Heinrich's relative, Duke Leopold. In addition, with the support of King Tankred , he wanted to withhold the Sicilian kingdom, the legacy of his wife Constanze , from the emperor . He also disregarded his feudal duties towards King Philip. He had made a shameful peace with Saladin. The complaints were intended to show that Henry did not arbitrarily and without good reason held the English king captive. Richard was given the opportunity to refute the individual allegations in a free speech before the Princely Court. He also offered a judicial duel , but none of those present wanted to conduct it against the ruler. Richard made a lasting impression in the Imperial Assembly with the admission that he had made mistakes and with his demonstrative gesture of throwing himself to the ground in front of the Emperor and asking for mercy. Heinrich granted him this by pulling the kneeling king close to him and giving him the kiss of peace. John Gillingham explains Heinrich's behavior with the hostile atmosphere on the court day, which led him to accept Richard in mercy. Roger von Howden reports on eager negotiations the day before, in which "the emperor demanded much that Richard was not ready to be entitled to even at risk of death." However, nothing is known about the subject of the negotiations. According to Klaus van Eickels , the Staufer demanded a particularly humiliating form of submission, which Richard was not prepared to perform. With the help of numerous comparative examples, Gerd Althoff was able to show that kneeling and kissing peace did not express spontaneous emotions; rather, such scenes were staged in the Middle Ages. Dieter Berg rates the outcome of the court day as an important prestige success for Richard. However, he remained in custody and was detained at Trifels Castle until mid-April . He then stayed in the emperor's entourage, initially in the Alsatian Palatinate Hagenau .

On March 25, 1193, Richard accepted the sum fixed in Würzburg at a court day in Speyer. He had to pay 100,000 silver marks. He also had to provide 50 ships and 200 knights for a year. The requirement for personal participation in the emperor's campaign in Sicily was dropped. The details were regulated in the Worms Release Treaty of June 29, 1193. The Worms Agreement is narrated by Roger of Howden. The ransom was increased to 150,000 silver marks. 100,000 marks pure silver according to Cologne weight should be paid for the release. That corresponded to about 23.4 tons of silver. The next 50,000 marks were to be held hostage, including sixty for the emperor and seven for the duke of Austria. The ransom was to be handed over to imperial ambassadors in London, checked by them and then sealed in transport containers.

Providing the ransom, which was three times the annual revenue of the crown, was an immense challenge. A special department, the scaccarium redemptionis , was set up in the royal treasury, the Exchequer, which was charged with collecting ransom taxes . The high clergy had to give up liturgical equipment and the fourth part of their annual income. A special tax of 25 percent had to be introduced and royal property sold. The profit from wool production, which was originally intended for the Cistercians and was normally exempt from royal taxes, was confiscated. The Red Book of the Exchequer , compiled in the 13th century, reports that each holder of a knight's fief had to pay 20 shillings.

Henry VI. established January 17, 1194 as the date for Richard's release at Christmas 1193. A considerable portion of the ransom had since been obtained and brought into the empire. Richard had meanwhile spent Christmas 1193 in Speyer. Philip II and Johann Ohneland tried to prevent the release already promised by the emperor by making far-reaching financial promises. Philipp agreed to pay 100,000 marks and Johann 50,000 marks for the extradition of Richard. Alternatively, they offered 1,000 marks for each additional month of Richard's imprisonment. In view of the new offer, Heinrich had become undecided about the further treatment of the prisoner and therefore put the princes present up for discussion on the Mainz court conference in February 1194. The great ones, however, insisted on the agreed release of the English king. Richard thus benefited from his already existing personal connections with the greats that he had established over the past few months. However, Heinrich managed to force Richard to take the English regnum as a fief from the emperor and pay an annual tribute of £ 5,000. In this context, only Roger of Howden reports that Richard should be crowned King of Burgundy . This territory was nominally part of the empire, but the emperor did not exercise any real rule there. According to Knut Görich, it could be a demonstrative honor to make the transfer of fiefdom of his own kingdom more bearable for the English king.

On February 4, 1194 Richard was released from custody at the court in Mainz. He paid fiefdom for all of his dominions. 100,000 marks of silver were paid to Heinrich and the other 50,000 marks were held hostage, including the two sons of Heinrich the Lion, Otto and Wilhelm . The archbishops of Cologne and Mainz handed Richard to his mother Eleanor of Aquitaine. After his release, he spent a few days in the woods of Nottingham . The link between the legend of Robin Hood, who lived with his followers in the woods of the Sherwood Forest , with the story of Richard the Lionheart was not made until the 16th century.

The ransom payment meant for Leopold the restoration of his honor, injured by Richard on the crusade. He used it to finance the expansion of his royal seat and the founding of Wiener Neustadt and Friedberg . His sudden death on December 31, 1194 by falling from his horse was viewed by contemporaries as a divine judgment on the capture of Richard. Heinrich used his share to conquer the Norman Kingdom of Sicily. With the ransom payment, sterlings are said to have come into circulation on the European continent for the first time . In London, the king's constant demands for money led to an uprising under Wilhelm Fitz Osbert in 1196 , which was suppressed.

Restoration of rule in England

After his release, Richard set foot on English soil again for two months on March 13, 1194. Despite the long imprisonment, the Angevin administrative structures functioned well after John Gillingham. On the island he took measures to stabilize his rule and tried to get the largest possible sums of money for the planned military campaigns against the French king. Richard called a court at Nottingham for late March and early April 1194 . On the well-attended court day, in which the Queen Mother and the brother of the Scottish King also took part, numerous punitive measures against rebels and personnel changes in the administration were decided. A few days later, on April 17th, Richard showed up in the presence of his mother Eleanor in Winchester Cathedral . His coronation was intended to erase the shame of his captivity and restore his honor. William of Newburgh noted that Richard appeared like a new king at the coronation in Winchester and that the glory of the crown of his kingdom washed away the shame of his captivity.

In 1195, Richard and King William I of Scotland agreed to marry his nephew Otto, who later became Emperor Otto IV , and Wilhelm's daughter Margaret of Scotland , who was expected to become the Scottish heir to the throne. Richard wanted to extend his influence to Scotland, and for Otto's family, the Guelphs , a new power base was in prospect with the marriage project. However, Wilhelm withdrew from the agreement after learning that his wife was pregnant. Pressure from the Scottish nobility could also have been decisive in his withdrawal.

The financial and administrative apparatus played an important role in the procurement of new financial resources. Officials and functionaries who had already paid large amounts of money for their offices when Richard came to power had to pay again. In the spring of 1194 the tax and army system was comprehensively reformed. The feudal taxes like the scutagium made up 1194 41.1 percent and 1198 42.7 percent of the total income. After the introduction of a new seal in 1198, all privilege recipients had to have their documents resealed for a fee. An inventory was made of all Jews on the island in 1194. They had to document all their monetary and credit transactions in writing and deposit the evidence in document boxes , the so-called archae . These boxes were set up in 27 cities. In addition, with the Exchequeur of the Jews, a separate treasury was created for the Jews in 1194 . With these measures, the crown wanted to better assess their economic and financial activities as well as the financial strength of the Jews under royal protection. This was to prevent future pogroms from destroying Jewish promissory notes and thereby causing material damage to the kingship.

Court culture and domination practice

The Court developed from the 12th century to a central institution of royal and princely power. Even a contemporary connoisseur of the court like Walter Map mentioned in his work De nugis curialium the difficulty of a clear definition of the high medieval court. Martin Aurel , one of the best experts on the continental history of the Plantagenets, defined the courtyard as the focal point, which was both residence and central court. From the court, the Plantagenets tried to master their "mosaic of kingdoms, principalities and dominions". But the farm was also a cultural center. He established the connection to the Norman dynasty and the Arthurian saga for the Plantagenets and ensured that minstrels spread their fame.

Until well into the 14th century, medieval rule was exercised through outpatient government practice. For the Anglo-Norman kings and Anglo-Angevin rulers, this was true not only for their island empire, but also for their continental possessions. The Angevin Empire had consisted of England since 1154, the French duchies of Normandy and Aquitaine and the counties of Maine and Anjou . For their property on the mainland, the English kings were vassals of the French king. For the last Anglo-Norman ruler, Henry I , Rouen was the preferred place of residence. Under Richard's father, Henry II, the focus of the itinerary to Chinon on the Loire and thus shifted even further south. Richard has only been to England twice in his entire time as king: four months at his coronation on September 3rd and two months after his release from captivity in 1194. During the second half of his reign Richard stayed in his French possessions throughout. His wife, Berengaria, never set foot in England during her husband's lifetime or after his death. She is the only English queen who has never been to the island. Richard's itinerary did not overlap with the Berengarias, who mainly stayed in the Loire Valley in Beaufort-en-Vallée , Chinon and Saumur . Apparently Richard hardly tried to father a descendant with Berengaria. In the 20th century, historians viewed this behavior as an expression of suspected homosexuality. Klaus van Eickels , on the other hand, assumes that Richard was impotent and knew this after his numerous premarital affairs did not result in any offspring.

As a king who was constantly on the move, Richard moved in a multilingual environment. He certainly spoke Anglo- Norman , could understand and read Latin. He seldom spoke English. Provencal was his mother's language and was spoken in Aquitaine. It was in this language that he communicated with his wife Berengaria.

During the crusade and during the time of captivity, the keeping of the court was severely restricted. The affairs of state were taken over by high officials appointed by Richard in the most important provinces. The court had to travel constantly to control this system. The administrative structures were most developed in England and Normandy. Already under Heinrich I, the so-called Exchequer was an incipient and, above all, separate administration of monetary income and expenditure as a separate "treasury". In the absence of the ruler, government affairs were carried out by capable administrators such as Hubert Walter and royal institutions such as the aforementioned treasury. Hubert Walter was one of the most important officials around the king. When Richard came to power, he was raised to the vacant bishopric of Salisbury for his services . There, however, it can only be detected once in the cathedral. He accompanied Richard on the Third Crusade and negotiated with Saladin while the king was ill. Back in England, he was elected Archbishop of Canterbury. He also took care of the ransom and from Christmas 1193 exercised the reign in England as Justiciar during the king's absence. Since he also became papal legate for England in March 1195 , as representative of the king he not only had viceroyal power, but also the spiritual leadership in England. Since the spring of 1194, mainly secular barons and simple knights stayed in the vicinity of the king. They gained increasing importance through the battles against the French king. In contrast, the influence of the spiritual group decreased. Among them were the Bishops of London , Richard Fitz Neal and Wilhelm de Sainte-Mère-Église , of Durham , Hugo de Puiset , and of Rochester , Gilbert de Glanville . Recent research also highlights the importance of Richard's mother to the order and security of the Empire during her son's absence. According to Jane Martindale, Eleanor exercised royal power after 1189, first in England and then in Aquitaine. According to Ralph V. Turner, the last fifteen years of Eleanor's life were primarily about keeping the Angevin Empire intact.

For the English kings, King Arthur became the central figure of identification. Shortly after his coronation, Richard had an excavation carried out at Glastonbury Abbey . The monastery was considered one of the oldest Christian places of worship and has been identified with the legendary Avalon since the second half of the 12th century . During the excavation, according to contemporary ideas, the graves of King Arthur and his wife Guinevere were discovered. The alleged Arthurian grave is regarded as a forgery; their purpose is assessed differently in research.

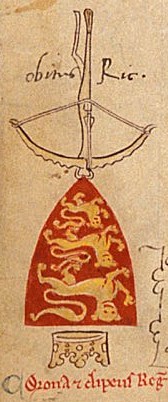

At the end of the 12th century, writing gained increasing importance as a means of rule, also in administration. Written procedural forms such as the pipe rolls , on which the annual income of the crown were recorded, established themselves in the courts of Europe . The Pipe Rolls not only offer insights into the social fabric of England, but are also an important prosopographic source. Events from everyday political life are also made clear in the accounts. Entries show that Richard had parts of the ruler's insignia taken into captivity. In the chancellery , the most important part of the court, outgoing correspondence and documents were archived and registered from 1199 onwards. On his seal, Richard is shown on a steed with a raised sword in his right hand. The seals served the English kings to represent and illustrate their own legitimacy, although they pursued different strategies than the Roman-German rulers. The English kings held an upturned sword in their right hand, the Roman-German kings preferred orb and scepter instead .

Richard's captivity was the reason for the creation of the Arthurian novel Lanzelet from the pen of Ulrich von Zatzikhoven . For a long time Richard kept a singer named Blondel at his court. The most famous troubadours of the time, such as Peire Vidal , Arnaut Daniel , Guiraut de Borneil or Bertram de Born (the elder) stayed in the vicinity of Richard the Lionheart. Only two songs have survived from the English monarch himself. Both are counted among the Sirventes . In research, however, it is assumed that his poetic oeuvre must have been more extensive. The first song, Ja nus hons pris ne dira , consists of six stanzas and has been handed down in two languages with Old French and Occitan . It deals with the experience of imprisonment and breach of faith. The composition of the song is dated around the turn of the year 1193/1194, that is, it is in the final phase of Richard's imprisonment. The second song, Daufin, je'us vuoill derainier , was written between 1194 and 1199. In it Richard criticizes the Counts of Auvergne for defending their lands only half-heartedly against the French king in his absence.

Last phase of life

Anglo-French clashes

Richard landed in Barfleur on May 12, 1194 . He renounced a severe punishment of his brother Johann Ohneland and took him back to grace. After the equalization with Johann he devoted himself to the preparations for the fight against the French king. With Richard's surprise attack on July 5, 1194, the French king could only escape by fleeing. In the process, in addition to men and equipment, he also lost his seal and the royal archive. On July 23, 1194, an armistice was concluded in Tillières near Verneuil with the support of a papal legate until November 1, 1195. Richard made major concessions in this agreement. He probably wanted to use the following months to build up further financial resources and new military forces. According to this agreement, the Capetian could dispose of large territories in Normandy, Richard, however, was only allowed to rebuild four Norman castles and was not allowed to pursue any further recuperation plans. Richard used the time gained to replenish the war chest. In 1194, a general tax of 10 percent was introduced on all exported goods. In the fight against Philip, John Gillingham was able to show that Richard, as ruler, tried to influence public opinion in Europe with embellished or forged letters.

Since the autumn of 1194, preparations for new battles had been going on on both sides. Until July 1195, however, the armistice was observed. In November / December 1195 there was a battle near Issoudun , from which Richard emerged victorious. In the peace treaty of Gaillon in 1196 he had to do without the Norman Vexin permanently , but he was able to consolidate his position in other parts of Normandy, in Aquitaine and in Berry . In 1196 Richard had Château Gaillard built in a very short time . This was supposed to block access to Normandy via the Seine valley. In June 1196, the two kings resumed fighting because they were both dissatisfied with the status they had achieved. In July 1197 Richard was able to meet the Flemish Count Baldwin IX. win as an ally and achieve an equalization with the South Welsh prince Gruffydd ap Rhys ap Gruffydd . This gave him the opportunity for a two-front war against the Capetians. In the summer of 1198 he attacked Philip again during a campaign through the Vexin. The French king tried in vain to reach Gisors castle ; the bridge over the Epte collapsed under the weight of the heavily armed knights, twenty knights drowned, the king was rescued from the water. Hundreds of knights were taken prisoner. At the Battle of Gisors in September 1198 in Normandy, Philip suffered a definite defeat.

Death and succession

The powerful Duke Heinrich the Lion was overthrown in 1180 by Friedrich Barbarossa at the instigation of several princes and had to go into English exile for several years. His children Heinrich von Braunschweig , Otto von Braunschweig , Wilhelm von Lüneburg and Richenza had lived mainly at the Angevin court since 1182 and were raised there. The childless Richard apparently temporarily considered Heinrich's son Otto as his own successor. Richard's brother Gottfried had died early. Otto was knighted by Richard in February 1196 and enfeoffed with the county of Poitou in late summer 1196 . This effectively made Otto the king's deputy in Aquitaine. Richard did not succeed, however, in getting Otto to succeed him.

The death of Henry VI. 1197 created a power vacuum in the empire north of the Alps, because Heinrich's son Friedrich was still a small child and lived far away in Sicily. In an empire without a written constitution, this led to two royal elections in 1198 and to the "German" controversy for the throne between the Staufer Philipp of Swabia and the Guelph Otto. This gave the Anglo-French conflict a further field of action. Richard supported Otto, because he wanted to have a reliable partner in the empire north of the Alps for his dispute with the French king. After John Gillingham, Richard invested a great deal of diplomatic effort and money in the anti-Staufer candidate because of his humiliating imprisonment with the late Staufer. The prisoner had Richards honor (honor) , affected what he - as Knut Görich stressed - had with vengeance to respond to the offender, because had honor key role as a mandatory standard. The Capetians, however, allied themselves on June 29, 1198 with the Staufer Philip of Swabia.

On June 9, 1198, Otto was elected king primarily because of the support of his wealthy uncle Richard. Before that, on March 8th, Philip of Swabia was elected king in Mühlhausen . The contest for the throne did not end until a few years after Richard's death with the murder of Philip.

Richard went to the Limousin in March 1199 . A revolt had broken out there by Count Ademar von Angoulême and Vice-Count Aimar von Limoges and his son Guido. When the insufficiently protected Richard approached the walls of the Châlus-Chabrol castle on March 26, 1199 , he was fatally wounded by a crossbow bolt. A doctor could only cut out the bolt. Ten days later the king died of his injury: On the evening of April 6, 1199, he died before the walls of the castle Chalus-Chabrol to gangrene . Richard is one of the few medieval rulers who, as a recognized king, lost their lives in battle. The circumstances of death inspired the creation of legends. It was said that he besieged the castle because there was treasure in it. He is said to have forgiven the crossbowman who hit him on his deathbed. In a source-critical investigation, John Gillingham was able to show that the siege was part of Richard's Aquitaine policy and should be understood as a preventive measure against the plans of the French king. Until then, the siege was explained in such a way that Richard had allowed himself to be carried away to this action with the prospect of a great treasure in the castle. However, this explanation was based on a contemporary legend.

Richard's brain and entrails were buried in Charroux in the Poitou, the heart in Rouen Cathedral , the center of English rule in Normandy. The rest of the body was buried with the royal regalia on April 11, 1199 in Fontevraud Abbey next to his father. Richard was the first King of England to be buried with his coronation insignia. The depiction of Richard's grave as a recumbent dead man with a cushion and footrest is unusual for this period. In addition to Richard's tomb, only the graves of his sister Mathilde, his mother Eleanor, his father Henry II and Henry the Lion are designed in this form. On April 21, 1199, Eleanor donated him a memorial for the year.

Richard's brother Johann Ohneland was able to prevail within a short time with the support of Eleonore against his rival and nephew Arthur I as the king's successor. On May 27, 1199 he was crowned King of England by Archbishop Hubert Walter of Canterbury. Johann kept the high tax demands. In 1200 he ended the conflict with Philip II through the Treaty of Le Goulet . In 1202, however, war broke out again with France , which in 1204 led to the loss of Normandy and other areas on the mainland. After the defeat of Otto, who was allied with Johann, in the battle of Bouvines in 1214 against the French king, Johann had to accept the losses in France and was now politically weakened. The barons of England were no longer ready to accept the arbitrariness of Johann and his financial demands. This was an essential requirement for the implementation of the Magna Carta Libertatum in 1215 .

Nickname 'lion heart'

Richard is the only English ruler whose lion attribute has been permanently anchored in historiography and legend. Numerous contemporary documents have come down to us for his nickname. Even before the assumption of power and the crusade, the Lionheart became the usual distinction in the Chansons de geste for a new type of hero, the Christian knight who had proven himself in pagan warfare. Even before he came to power in 1188, Gerald of Wales spoke of Richard as a "lion-hearted prince". The chronicler Richard von Devizes explained how the English ruler got his lion name outside of his realm. Immediately after his arrival in Messina, Richard, unlike the French King Philip II Augustus, punished crimes committed by his men against the local population. The Sicilians then called Philip a lamb, while Richard was given the lion's name. A similar comparison can be found in Bertran de Born. On Richard's arrival at Acre in June 1191, Ambroise wrote in his Chronicle of the Third Crusade (L'estoire de la guerre sainte) , which ended in 1195 , that “the excellent king, the heart of the lion” (le preuz reis, le quor de lion) had arrived .

The Middle English verse novel about Richard the Lionheart (Kyng Rychard Coer de Lyoun) from the second half of the 13th century tells another episode how Richard got his nickname: on his return from the Holy Land he was captured and had the daughter seduced by the king. When the king sent a hungry lion to Richard's cell as a punishment, Richard tore out the animal's heart. Thereupon the king described Richard as a devil who deserves the nickname the lion heart.

reception

Richard the Lionheart appeared as the ideal of the monarch and crusader in historiographical and fictional literature and among the general public. A completely different development emerged in the scientific literature. In modern research he has been judged partly as egocentric and his rule as unsuccessful.

According to Dieter Berg , at least four lines of development can be distinguished for the history of the reception of the lionheart picture. The first thread concerned the portrayal of Richard's activities on the crusade in comparison with those of his adversary Saladin. The description of Saladin's military qualities and personal bravery made it possible to glorify Richard's victories and fame all the more intensely. In the second strand, material was transferred from the Latin chronicle to the vernacular literature. The legendary elements intensified and led to a “popularization” of the ruler. The third strand was the Blondel motif that appeared in 1260 and was enriched with other narrative material. In the fourth line of development, the life story of the king was interwoven with stories about the ballad hero Robin Hood .

High and late Middle Ages

The 12th and 13th centuries were a heyday for written culture. There was a large number of historians, especially in England. Spiritual chroniclers such as Richard of Devizes , William of Newburgh and Gervasius of Canterbury and secular scribes such as Radulfus of Diceto and Roger of Howden described the rulers in detail. The contemporary Chronicle of Rogers of Howden is one of the most important historical works of Richard's time. Roger wanted to portray the history of England from Beda Venerabilis in the 8th century to his own time. For him, Richard became a bearer of hope after the years of crisis at the end of Henry II's reign. As a historian who was close to the court, Roger was well informed about the events. With Richard's death the whole world went under in his eyes: “In his death the ant destroys the lion. Oh pain, in such a downfall the world perishes ” (In hujus morte perimit formica leonem. / Proh dolor, in tanto funere mundus obit).

The tendency to glorify the monarch was permanently promoted by the crusade. Members of the English army contingents described the events in the Holy Land as eyewitnesses in their historiographical reports. In the works of Ambroise (L'estoire de la guerre sainte) and an anonymous chaplain of the Templars ( Itinerarium peregrinorum et gesta regis Ricardi ) Richard was stylized as a crusade hero who was above all far superior to the French king. Critical judgments from the Capetian side, such as Rigord and Wilhelm the Breton , who portrayed Richard as devious and unscrupulous, only increased the glorification of the English king on the Angevin side. A comparison of contemporary European historiography with the Arabic chronistics and poetry of the Third Crusade shows that Richard's chivalry was already particularly emphasized during his lifetime.

A further increase in heroism began with the sudden death of the monarch. He was especially glorified in the death suits of various troubadours. The troubadour Gaucelm Faidit was one of his companions on the crusade. He described in detail the heroic deeds in the Holy Land and in his mourning for the dead sang profusely that neither Charles nor Arthur had reached Richard. Critical voices are rare. For Gerald of Wales the sudden death of the monarch was the divine punishment for having diminished the freedoms of the church through heavy material burdens and thus exercising tyranny on the island. The alleged neglect of the island kingdom due to Richard's constant absence was not criticized by contemporaries, but only reprimanded by 19th century historians.

The Angevin rulers had no myths and ideologies of their own to legitimize their dynasty. Since their origins go back to Wilhelm the Conqueror , they could neither refer to the old English kings nor to the Carolingians . As an alternative, they particularly emphasized knightly ideals. Even during his lifetime Richard promoted the creation of legends about his life and his deeds. Unlike his father, Richard was less interested in glorifying the dynasty than in glorifying himself. He consciously placed himself in the tradition of the legendary King Arthur. According to his biographer Roger of Howden, the legendary sword of this king, Excalibur, was in Richard's possession. Richard took up a myth about his ancestor Fulko Nerra and had it spread at court as early as 1174. Fulko's wife was of unknown origin. During a forced visit to a church service, she turned out to be a devilish being. With this legend Richard emphasized the sinister and threatening in the history of his family to his own subjects.

Richard also had an excellent reputation in the German-language literature of the High Middle Ages. Walther von der Vogelweide criticized the lack of rulership of generosity (milte) with the Staufer King Philip of Swabia. He saw Saladin and Richard the Lionheart (von Engellant's) as role models for proper rulership . In the Carmina Burana , a collection of songs that was probably created around 1230 in the southern German-speaking area, a verse sung by a woman raves about Engellant's chunich . For him she would forego all possessions if Engellant's chunich were in her arms. Research suggests Richard the Lionheart behind the chunich from Engellant . Already the first medieval corrector changed the passage in the 14th century and overwritten it with the chunegien , which probably alluded to Richard's mother Eleanor.

Richard was also admired by his enemies. Despite the Acre massacre, he received praise from Muslims. John Gillingham was able to use three Arab chroniclers from close quarters of Saladin to show that they paid tribute to Richard with respect and respect. According to the historian Ibn al-Athīr , Richard was the most outstanding personality of his time in terms of bravery, cunning, steadfastness and resilience. William the Breton believed that England would never have had a better ruler if Richard had shown proper respect for the French king.

Richard the Lionheart was soon after his death the benchmark for other kings and was called "wonder of the world" (stupor mundi) . In an anonymous panegyric , Edward I , who became King of England in 1272, was praised as the new Richard (novus Ricardus) . According to Ranulf Higden , the English chronicler of the 14th century, Richard meant the same thing to the English as Alexander meant to the Greeks, Augustus to the Romans and Charlemagne to the French. Matthäus Paris , monk in the monastery of St. Albans , was the author of a great chronicle (Chronica majora) . He attributes generosity as a quality to Richard the Lionheart. Margaret Greaves was able to show that the example of the generous Richard the Lionheart remained a topos in English literature until the 17th century .

The Blondel motif first appeared around 1260 . According to the legend, while Richard was imprisoned, Blondel went in search of the imprisoned ruler. He went singing through the country and spent a whole winter as a singer in a castle. At Easter he found the ruler's attention through the first stanza of a song composed with Richard. Richard was identified by the chanting of the second verse. Blondel then traveled to England. According to one version, he initiated the negotiations of the English barons to release the king there; according to another version, he initiated them himself. There are no personal relationships whatsoever with the historically verifiable person Blondel de Nesle . The Blondel motif was processed in many literary ways well into the 19th century.

Early modern age

The Scottish chronicler John Major arranged the stories about Robin Hood in his 1521 Latin History of Britain (Historia majoris Britanniae) in Richard's time. Robin Hood stories had been around since the 13th century. John Major's classification of Robin Hood as a contemporary of Richard the Lionheart was just as speculative as that of his predecessors, but prevailed in the long term. In the 1598 drama The Downfall of Robert Earle of Huntington by Anthony Munday , the noble robber had to go into the woods as an outlaw during the tyranny of Johann Ohneland. After returning from the crusade, Richard the Lionheart restored order as a radiant hero.

Richard's image as the ideal of the western king and exemplary crusader remained dominant until the 17th century. According to Raphael Holinshed (1578), Richard was "a notable example to all princes". For John Speed (1611) Richard was the "triumphant and shining star of chivalry" ("this triumphal and bright shining star of chivalry").

Modern

Public honors

German poets played a key role in ensuring that the myth of Richard the Lionheart continued into modern times. Georg Friedrich Handel (1727) and Georg Philipp Telemann (1729) composed operas on this theme. In German romanticism , Richard the Lionheart was transfigured into a symbol of freedom. Heinrich Heine's poem in Romanzero (1851) and Johann Gabriel Seidl's text (Blondels Lied) in the setting by Robert Schumann (1842) also achieved greater fame . The image of Robin Hood and the English King Sir Walter Scott had a decisive influence on Ivanhoe (1819) for the decades to come. Ivanhoe was translated into twelve languages in the 19th century and there are 30 theatrical versions. In Ivanhoe , Robin Hood fights on the Anglo-Saxon side against the Norman occupiers and their King Richard the Lionheart. In his novel Tales of the Crusaders , published in 1825, Scott put the English king at the center of the action. Eleanor Anne Porden , Benjamin Disraeli , William Wordsworth and Francis Turner Palgrave continued the exaltation in their works.

The story of the singer Blondel found numerous adaptations in the 19th century, including operas such as Il Blondello (Il suddito essemplaro) , Il Blondello (Riccardo cuor di Leone) , Richard and Blondel , Il Blondello or Blondel . In the later reception of the Blondel motif, the person of Richard stepped back against elements such as unbreakable loyalty and friendship.

The beginning of industrialization in England brought with it not only environmental pollution but also social upheaval. In literature and art, the Middle Ages were idealized as a form of society and life. In the painting Robin Hood and his Merry Men by Daniel Maclise , crusaders and robbers sit down to eat and drink under chestnuts and oaks.

Richard the Lionheart has been a symbol of national greatness since the 19th century at the latest. During the Crimean War , England competed with France and Russia for supremacy in the eastern Mediterranean and for influence in the Ottoman Empire. The English King Richard the Lionheart appeared through his heroic deeds in the Holy Land as a suitable figure of identification for England's pursuit of primacy. In 1853 it was proposed that Richard's remains should be transferred from Fontevraud to England. During the First World War , the actions of the British Army in the Middle East under General Edmund Allenby and the capture of Jerusalem with Richard the Lionheart were associated and referred to as "last crusade" (last crusade).

The idealization also continued in art and architecture. The Italian sculptor Baron Carlo Marochetti created a large equestrian statue. The statue was originally intended for the 1851 London World's Fair and was erected in front of the Houses of Parliament in 1860 . The heroization of the rulers, however, already met with bitter criticism from contemporaries. During the Second World War, the statue was damaged in a German bombing raid in 1940. The sword, which was held in the air, was bent, but it did not break. Radio broadcasts took this as an opportunity to use the character of Richard to maintain the morale of the population. Richard became a symbol of the strength of democracy. It was only when the war changed in favor of the Allies that a member of parliament applied for the sword to be judged in October 1943. In the 1956 judgment of Winston Churchill , Richard was worthy of taking a seat at the Round Table with King Arthur and the other venerable knights .

In the 20th century, the subject of Richard's life was also used in comics and film, such as in Cecil B. DeMille's Crusader - Richard the Lionheart (1935), but his figure took a back seat to that of Robin Hood. In the films Richard is received as a multifaceted figure: as a war hero, war criminal, savior of England, fighter for justice or a loving son. Richard the Lionheart appears in the film Robin Hood (1922) as a drink-happy, overweight and always laughing king . In the films Robin Hood - King of Thieves (1991) and Heroes in Tights (1993) Richard is portrayed as a kind father figure. He only plays a subordinate role in both films. Richard also made a brief appearance in the successful blockbuster Kingdom of Heaven by Ridley Scott (2005). The film The Lion in Winter (directed by Anthony Harvey , GB / USA 1968) based on the play by James Goldman played a major role in consolidating the idea that Richard the Lionheart was homosexual. Richard Lester's film Robin and Marian (with Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn , 1976) shows Richard as a narcissistic tyrant who dies at the beginning of the film. In the 2010 Robin Hood movie , Richard is a cynical and ruthless psychopath. The film plot begins with the siege of Chalus Castle. Robin, played by Russell Crowe , reminds King Richard of the Acre massacre and is imprisoned as a result. However, he managed to break free when the king fell in the siege.

In the last few decades, as Dieter Berg notes, Richard the Lionhearted “trivialization and commercialization” took place in public. The medieval ruler was incorporated into computer games and gave his name to Camembert cheese (Coeur de Lion) or a Calvados in Normandy (Coeur de Lion) . The historical personality of the English king takes a back seat to contemporary marketing. In Annweiler , 800 years after the king was captured in 1993, a small lion heart exhibition was organized. A special bottling with Riesling Spätlese was named after the English king.

Research history

Since the 17th century, historiography saw Richard as the “bad king”. This negative view first spread in more general accounts of the history of England. In 1621, Samuel Daniel highlighted the great financial burdens of the English Empire and its neglect by Richard. Winston Churchill the Elder described Richard as a self-centered person who had neglected the island realm. Since the 18th century, the condemnation of the medieval crusades in Protestant circles in England was accompanied by severe criticism of the Catholic Church. In 1786 David Hume criticized the crusades and the military atrocities that Richard was responsible for as a crusader.

The critical point of view in historiography has been decisively influenced by William Stubbs in particular since the late 19th century . For him Richard was "a bad son, a bad husband, a selfish ruler, and a vicious man" ("a bad son, a bad husband, a selfish ruler and a vicious man"). For him it was only about waging war and glorifying himself. The tyranny of his brother Johann is the consequence of Richard's rule. This negative position remained prevalent throughout the scientific literature in the 19th century. In the 1903 portrayal of James Henry Ramsay , Richard was a "simple Frenchman". He criticized the disregard for England in Richard's political work. The ruthless exploitation and neglect of the island kingdom and the monarch's egocentrism were also highlighted by subsequent historians such as Kate Norgate (1924).

Even after World War II, the view of Richard as an irresponsible and selfish monarch remained predominant, as the influential handbooks since the 1950s by Frederick Maurice Powicke and Austin Lane Poole show. In fact, he was often seen as one of the worst rulers in England. The influential explorer of the crusade history Steven Runciman praised his military skills ("gallant and splendid soldier"), but Richard was also for him "a bad son, a bad husband and a bad king" (a bad son, a bad husband and a bad king). After the Second World War, he was also assumed to be homosexual and a homoerotic relationship with the singer Blondel. Richard's homosexuality was represented in 1948 as the first historian John Harvey in his widely distributed work The Plantagenets . A few years later this motif was used in popular scientific literature and in feature films, for example by Gore Vidal or Norah Lofts .

The negative assessment was revised in the 1980s. The fundamental work of John Gillingham in particular played a decisive role in this. His biography, published in 1999, is considered a standard work. Richard became a legend because of his warlike qualities. For Gillingham, Richard the Lionheart was an ideal monarch by medieval standards. He declared him one of the best monarchs in England at all. A large number of detailed studies and further biographies continued the tendency towards a more positive view ("lionizing Lionheart"). According to the biography of Ulrike Kessler (1995), the English king was not a politically irresponsible ruler, but a master of political tactics. On the occasion of the 800th year of death of Richard the Lionheart, an international conference on court and court life at the time of Henry II and his sons took place in Thouars, Aquitaine . The files of the conference were published by Martin Aurell in 2000. Jean Flori published a biography of Richard in 1999. He investigated the extent to which Richard corresponded to the ideal of a knightly king for his contemporaries.

In 2007 Dieter Berg presented the basic presentation in German. In his biography he again tied in with the negative judgments of older research. Berg chose “deliberately not an exclusively biographical approach” for his presentation, but intended an appreciation of Richard “in a pan-European context”. For him, Richard was primarily responsible for the "failure of the Third Crusade". He was unable to solve the structural deficits of the Angevin empire "due to the lack of uniform ruling and administrative institutions in the disparate parts of the empire". In addition, his fiscal policy had devastating effects. The very different judgments in research can be explained by the different perspectives and assessments of contemporary sources.

The Historical Museum of the Palatinate taught from September 2017 to April 2018 with Richard the Lionheart: King - Knights - prisoners for the first time in 25 years, a national exhibition of. Until then, no museum on mainland Europe had honored Richard with a special exhibition.

swell

- Ambroise, L'estoire de la guerre sainte Histoire en vers de la troisième croisade (1190–1192) (= Collection de documents inédits sur l'histoire de France. Volume 11). Edited and translated by Gaston Paris, Paris 1897 ( online ).

- Richard von Devizes, Chronicon de rebus gestis Ricardi primi. In: Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II., And Richard I. (= Rolls Series. Volume 82.3). Edited by Richard Howlett, London 1886, pp. 381–454.

- Roger von Howden, Chronica (= Rolls Series. Volume 52). Edited by William Stubbs, 4 volumes, London 1868–1871 (available online Volume 1 ; Volume 2 ; Volume 3 ; Volume 4 ).

- William of Newburgh, Historia rerum Anglorum. In: Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II., And Richard I. (= Rolls Series. Volumes 82.1 and 82.2). Edited by Richard Howlett, London 1884–1885 (available online Volume 1 ; Volume 2 ).

literature

Lexicon article

- John Gillingham : Richard I [called Richard Coeur de Lion, Richard the Lionheart]. In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861411-X , ( oxforddnb.com license required ), as of 2004

- Wolfgang Georgi: Richard the Lionheart. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 8, Bautz, Herzberg 1994, ISBN 3-88309-053-0 , Sp. 205-207.

Representations

- Ingrid Bennewitz , Klaus van Eickels (ed.): Richard Löwenherz, a European ruler in the age of confrontation between Christianity and Islam. Medieval perception and reception. University of Bamberg Press, Bamberg 2018, ISBN 978-3-86309-625-0 ( online ).