Diocese of Worms

The diocese of Worms (lat. Episcopatus Wormatiensis ) was a Catholic diocese with seat in Worms (for the diocese also lat. Wormatiensis Dioecesis ). The bishopric, founded in late antiquity , reached a peak in power and influence in the Carolingian period and in the high Middle Ages . The episcopal church was the Worms Cathedral , one of the three Rhenish imperial cathedrals . The Hochstift Worms also held secular power over the Lobdengau , a small area around Ladenburg . Due to the Reformation , the diocese lost a large part of its parishes and was dissolved around 1800 at the time of the French Revolution .

History of the diocese

Early days

The origins of the Diocese of Worms date back to Constantinian times at the earliest . In 346, for example , a bishop is mentioned for the controversial Cologne Synod , but there is no evidence of a cathedral for this period .

It was not until Frankish times that the Worms list of bishops began again with Bishop Berthulf, who took part in the Paris Synod in 614. Various evidence pointing to Metz influences make a reorganization of the diocese under the rule of the Austrasian King Childebert II (575-596) resident there likely. Only a little later the first mission centers in Worms were found on the right side of the Rhine.

middle Ages

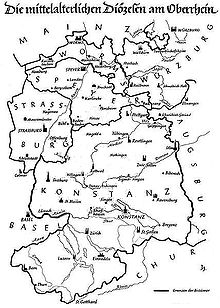

Under the Carolingians, Worms was a center of power, so that its bishops in the 8th and 9th centuries were close to the royal court and often combined their office with an abbatiate outside the diocese. The diocese belonging to the Metropolitan Association of Mainz still had considerable economic power in the 12th century and was divided into four archdeaconates . Their owners were the cathedral provost for Worms and the hinterland on the left bank of the Rhine , the provost of St. Paul in Worms for the northern part of the diocese on the left bank of the Rhine, the provost of St. Cyriakus in Neuhausen for the Lobdengau and the provost of St. Peter in Wimpfen for the Elsenzgau and the Gartachgau in the eastern part of the diocese.

The Domkapitel disposal 1270 50 prebends whose number dropped to 44 to 1291 and 1475 still 43 counted. However, the number of canons was only 35, plus there were six other prebenders whose owners were not canons and who had to be ordained a priest. Since 1281, the chapter no longer accepted any bourgeoisie into its ranks, so that its members mainly came from the Palatinate nobility.

Since the 13th century, the bishops were represented in pontifical functions by auxiliary bishops . In the 14th century the archdeacons lost their importance and the influence of the vicar general increased noticeably. In the late Middle Ages, the diocese consisted of the ten deaneries Dirmstein , Guntersblum , Westhofen , Leiningen , Freinsheim , Landstuhl , Weinheim , Waibstadt , Schwaigern and Heidelberg ; with about 255 parishes and a little over 400 clergymen within the episcopal city.

Post-Reformation period

In the 16th century, large parts of the diocese fell victim to the Reformation, so that the papal legate Commodone proposed an at least temporary union with the diocese of Mainz at the Augsburg Reichstag in 1566 , but this did not happen. Around 1600 the diocese only had 15 parishes .

In order to ensure the survival of the diocese, the cathedral chapter had already ensured that its electors had influence and benefices outside the diocese before they were elected bishop, and after the Thirty Years' War it finally renounced an election ex gremio and instead posited foreign clergy princes. This also meant that the cathedral chapter was able to gain greater influence on the administration of the diocese, as the bishop usually did not reside in the diocese.

The rebuilding of the parish system, which is now beginning, was usually carried out by religious orders, which in future also became the main sponsors of regular parish pastoral care. By 1732 the number of parishes could be increased to about 100. From 1711 the diocese again had an auxiliary bishop. Since it did not have its own seminary, Fulda was able to expand its influence for the training of secular clergy for the diocese of Worms.

The part of the diocese on the left bank of the Rhine was permanently occupied by French troops from 1797 and finally fell legally to France . With the Concordat of 1801 , the diocese boundaries were redefined in France and now corresponded to the boundaries of the respective departments . For this reason, the Worms diocese parts on the left bank of the Rhine were combined with many other ecclesiastical sub-territories in the newly formed, French Grand Diocese of Mainz; it was congruent with the new political département du Mont-Tonnerre . After these areas on the left bank of the Rhine returned to Germany in 1817, the Grand Diocese of Mainz was also divided up again. The southern part, with a large area of the former diocese of Worms (e.g. Frankenthal , Grünstadt , Kaiserslautern ) came to the restored diocese of Speyer and was politically attached to Bavaria as the Rhine district . The northern (smaller) part of the former Worms diocesan area (mainly Worms and its surrounding area) remained with the Diocese of Mainz and came to the Grand Duchy of Hesse (Hessen-Darmstadt).

The considerable part of the diocese of Worms on the right bank of the Rhine continued to exist as an independent Vicariate of Lampertheim until 1827 . When the diocese borders on the right bank of the Rhine were reorganized , the part located in the Grand Duchy of Baden came to the Archdiocese of Freiburg (mainly Mannheim and Heidelberg ), while the eastern part (Lampertheim, Bad Wimpfen ) located in the Grand Duchy of Hesse (Hessen-Darmstadt ) went to the Diocese of Mainz.

Worth knowing

Diocesan patron was the early Bishop of Worms St. Amandus , another patron of St. Peter , to whom the cathedral was consecrated and whose key ( Petri key ) was also included in the diocese coat of arms .

In the city of Oppenheim there was the curiosity that the diocesan border with the Archdiocese of Mainz divided the city: the northern part with the Katharinenkirche belonged to the diocese of Mainz, the southern part of the city to the diocese of Worms. This was based on the urban development in the 11th century: The original village of "Obbenheim" with its church, St. Sebastian, was on the northern border of the diocese of Worms. After it had received city rights in 1008 , it had expanded in a north-westerly direction to the area that originally belonged to the Niersteiner district and thus to the diocese of Mainz. The construction of St. Katharinen began around 1230. The church was in the area claimed by Mainz. This initial situation was a source of conflict. On June 8th, 1258 it was determined that each of the two churches would have its own pastor and thus the different diocesan membership was established. This lasted for centuries. Almost half a millennium later, from 1749, the two dioceses tried to completely integrate Oppenheim into a diocese by swapping territory. Since the dioceses could not agree on the exchange equivalent, the status was retained until the fall of the diocese of Worms.

History of the Hochstift Worms

The Worms Monastery was the secular domain of the Worms bishops and an imperial estate of the Holy Roman Empire .

The Bailiwick of the Diocese of Worms, connected with the office of the Burgrave , was held by the Counts of Saarbrücken until 1156 and then passed to the Counts Palatine near the Rhine . Although the bishop was of great importance during the Staufer period , he only succeeded in acquiring a small domain in the long run, the residence of which became Ladenburg in 1400 . As Prince-Bishop, the Bishop of Worms was represented with a virile vote in the Imperial Council of Dukes. The state area, which was gradually reduced in size and consisted only of exclaves , comprised only 15 villages on the left bank of the Rhine and 3 villages on the right bank of the Rhine in the vicinity of Worms from the 18th century . In 1798 the goods on the left bank of the Rhine fell to France , most recently with eight square miles and 20,000 inhabitants, which included around 8,500 guilders in annual income. The areas on the right bank of the Rhine came to Baden and Hessen-Darmstadt in 1803 .

Property in the Mittellahngebiet (Central Hesse)

Far away from Worms, the bishopric in Central Hesse (see section history) in the former Lahngau had been given extensive property by the emperors. In 993, for example, the guardianship government of the minor King Otto III. Weilburg Abbey with the associated property and rights to Worms Bishop Hildibald, the head of the royal chancellery, as a kind of compensation for the fact that the diocese of Worms in the vicinity of Worms and in the Palatinate Forest had to resign from the Salian Duke Otto. This made the diocese of Worms a political factor in the Middle Lahn area. By the year 1002, almost the entire property of the Weilburg monastery including the Weilburg settlement came to the diocese of Worms. Other property was concentrated around Frankenberg (Eder) , Marburg , Gladenbach , Haiger , Kalenberger Zent and Nassau .

Karl Ernst Demandt writes about this in History of the State of Hesse :

“Supported by the Ottonian emperors, the diocese of Worms had almost inherited the Conradin ruling house in Central Hesse, as can be seen from the large imperial estate complexes facing it in the 10th and 11th centuries.

King Konrad gave z. B. 914 the large area of the 'Haigerer Church' to the Walpurgis monastery in Weilburg. Emperor Otto III. even gave the entire Konradine property to the cathedral monastery of Worms in 993. "

However, the bailiffs of the Weilburg monastery, the Counts of Nassau , increasingly pushed back the influence of the diocese in the Middle Lahn area and in the Central Hessian area, thereby expanding and consolidating their domain.

In 1294, Adolf von Nassau , German king since 1292, acquired the Weilburg bailiwick with the Walpurgis pen through purchase. The church patronage, however, remained with the Bishop of Worms.

Country division

In the 18th century, the country was divided into the four administrative districts of Lampertheim , Horchheim , Dirmstein and Neuleiningen , with the associated official cellars as administrative headquarters, to which the Neuhausen office was added.

For the Episcopal Winery Dirmstein, the following number of administrative officials is documented in 1774, which is likely to have been similar in the other districts: "1 Amtskeller ( bailiff ), 1 clerk, 1 Oberschultheiß , 2 clerks and 2 clerks."

Official winery Lampertheim

It was actually called Kellerei Stein , but was located in the Rentamt zu Lampertheim and included the localities:

Official winery Horchheim

The villages were part of it:

Official winery Dirmstein

It was located at the Episcopal Castle in Dirmstein (the office building is still preserved) and included the communities:

Official winery Neuleiningen

She resided in the Neuleiningen Episcopal Cellar and administered the villages:

Official Neuhausen office

Responsible for the three places ceded by the Electoral Palatinate to the Hochstift in the 18th century :

See also

literature

- Hans Ulrich Berendes: The bishops of Worms and their bishopric in the 12th century . Diss., University of Cologne 1984.

- Friedhelm Jürgensmeier (ed.): The diocese of Worms. From Roman times to the dissolution in 1801 (= contributions to the history of the Mainz church. Vol. 5). Echter-Verlag, Würzburg 1997, ISBN 3-429-01876-5 .

- Bernhard Löbbert: About the written estate of Lorenz Truchsess von Pommersfelden (1473–1543) , in: Archive for Middle Rhine Church History 60 (2008), pp. 111–132.

- Ders .: Johannes Gamans (1605–1684) and the Wormser Memorialliteratur , in: Archive for Hessian History 69 (2011), pp. 265–273.

- Ders .: Historical sources on the city and the diocese of Worms. Manuscripts from the Hessian State Archive Darmstadt , in: Archive for Hessian History 62 (2004), pp. 293-300.

- Ders .: Johannes Bockenrod (1488-ca.1536). Poet, historian theologian , in: Der Wormsgau 22 (2003), pp. 109–125.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedrich von Weech: Das Wormser Synodale from 1496 , in: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine . Volume 27, Karlsruhe 1875, pp. 227-326, 385-454.

- ^ Friedhelm Jürgensmeier : The Diocese of Worms from Roman times to its dissolution in 1801 , Echter Verlag, Würzburg, 1997, ISBN 3-429-01876-5 , p. 261

- ^ Brück: The Church Past , p. 70.

- ^ Brück: The Church Past , p. 77.

- ^ Karl Ernst Demandt : History of the State of Hesse. 2nd Edition. Bärenreiter Verlag, Kassel / Basel 1972, ISBN 3-7618-0404-0 .

- ↑ Archived copy ( memento of the original from April 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Anton Friedrich Büsching : New Earth Description , 5th Edition, 3rd Part, Volume 1, pp. 1143–1147, Hamburg, 1771; (Digital scan)

- ^ Carl Wolff: The immediate parts of the former Roman-German Empire after their previous and present connection , Berlin, 1873, p. 232; (Digital scan)

- ↑ Michael Frey : Description of the royal Bavarian Rhine district , Volume 2, Speyer, 1836, p. 336; (Digital scan)

- ↑ Bärbel Jakob: From the castle to the tenement house. In: Mannheimer Morgen. August 13, 2010.