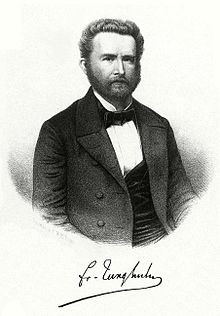

Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn

Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn (born October 26, 1809 in Mansfeld , † April 24, 1864 in Lembang on Java ) was a German doctor , geologist , botanist and surveyor . He undertook his scientific research and discovery trips to the Dutch-Indian islands of Java and Sumatra , which are now part of Indonesia .

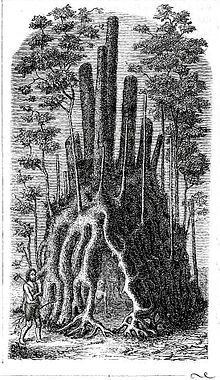

The most important achievement of this "greatest German researcher on Malay soil" was the first thorough geographical, geological and botanical exploration of the island of Java . His main work Java, which is overflowing with substance, is of lasting value , its shape, plant cover and interior design , which are supplemented with a large-format landscape atlas, the first reliable map of this island and a catalog of the geological collection "to explain the geological structure" could. In addition, he provided the first detailed topographical and ethnological description of the southern Batak lands on Sumatra . The cultivation of cinchona trees in Java was invaluable in combating malaria .

Junghuhn's works, written under the influence of his role model Alexander von Humboldt , are among the most valuable creations in geographical literature. For decades, they inspired numerous natural scientists to undertake further research. Extensive collections attest to these works: geologists and paleontologists have evaluated his rock and fossil collections, botanists and paleobotanists have evaluated his herbaria . To date, this work has not been completed.

In the opinion of the geographer Oscar Ferdinand Peschel , Junghuhn is "one of the adornments of German science" alongside Alexander von Humboldt and Leopold von Buch . It has been wrongly almost forgotten in Germany.

Junghuhn's official botanical author's abbreviation is “ Jungh. ".

Life

Preliminary remark

Many of his supporters are convinced that Junghuhn would have achieved similar successes as Alexander von Humboldt under the same conditions . However, the external conditions of the two researchers and their characters were completely opposite. As a descendant of a wealthy aristocratic family, Humboldt enjoyed the best imaginable childhood and youth education, his natural science inclinations were encouraged by understanding private teachers, his means allowed him to pursue his inclinations without restriction, and his cosmopolitanism, combined with diplomatic skills, helped him to influence how it was not assigned to a researcher either before or after it.

The development of young chickens was completely different. The son of a petty bourgeoisie was brought up with a rough hand. Contrary to his inclinations, he should support his father, who was active as a non-medical practitioner, and learn the necessary basic medical knowledge. His knowledge, which later became so multifaceted and went far beyond that, which made him one of the most outstanding universal scholars of the 19th century, he acquired autodidactically . After the rift with his parents and years of hardship, he went to the Dutch East Indies , where he worked as a botanist, geologist, paleontologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, ethnologist, meteorologist and surveyor in addition to his service as a military doctor. The abilities he possessed in all of these disciplines without ever having completed a degree are testimony to his works.

The tense relationship with his father, intensified by the assertion of his scientific interests to the limit of irreconcilability, contributed significantly to the development of his defiant and inflexible behavior. Unlike Humboldt, Junghuhn was completely undiplomatic and uncompromising to the point of stubbornness. He expressed himself disrespectfully, often with scorn and mockery, to superiors, colleagues, colonial officials and Javanese nobles, which led to constant disputes until the end of his life. In character, Junghuhn was a selfish person who was right with every means to achieve his goal. His resistance to envious contemporaries and influential critics made him an “edgy, buttoned loner” and an “uncomfortable man who did not make life easy for himself and others.” “What he hated in his soul was amateur gossip, and if you did Add to that his irresistible penchant for satire, then one can understand why his life turned into an almost incessant chain of conflicts and why his existence repeatedly came to stand on the knife edge. ”( A. Wichmann ).

Until the end of his life there was only one person whom he honored as a role model and with whom he respectfully corresponded: It was the already mentioned co-founder of geographical science, Alexander von Humboldt, forty years his senior, whose views of nature he called the "unattainable model" has designated. Otherwise, apart from subordinates or the few people who were benevolent to him, he avoided dealing with people whenever possible.

Youth and student days

Youth in Mansfeld

Junghuhn was the first child of the married couple Wilhelm Friedrich Junghuhn, a mountain surgeon, and Christine Marie, born Schiele, on October 26, 1809 in the Saxon-Prussian copper ore mining town of Mansfeld on the eastern edge of a foothills of the Harz Mountains . Of the six siblings who followed him, two died in childhood.

Little is known about the young chicken's youth. According to Karl Johann August Müller , who visited contemporaries in Mansfeld and asked about young fowl, he is said to have always been the leader in boy pranks. His boldness bordered on audacity. Among other things, it is said to have been one of his favorite inclinations to climb the most dangerous places of the ruins of the Count's Castle, which were rising above Mansfeld and not yet restored. With it he spread fear and horror: the daring climbing of an old remnant of the wall, which fell down and threatened to smash the people and houses at the foot of the Schloßberg, was particularly attractive to him. Fearlessly he crawled through the underground rooms and corridors of the castle with a string and a lantern.

Younghuhn's penchant for nature awoke very early on: In the densest forests, he collected flowers, herbs and especially mushrooms. In his endeavor to depict the plants true to life, he developed a great talent for drawing. However, this affection was suppressed in his petty-bourgeois parents' home. As a firstborn, Young Chicken was destined to pursue his father's professional career and to provide for his parents' livelihood until they died. However, Mansfeld did not have a grammar school, which is why he was tutored by a private teacher with the aim of reaching the university entrance qualification. A momentous blunder was to transfer this task to the Evangelical Lutheran Mansfeld Archdeacon This taught with such unusual severity and conservative faith in God that Junghuhn until his death turned against the Christian teachings and a supporter and advocate of Carl Ferdinand Hecht pantheism has become . His training in Latin was, however, with the same rigor and thoroughness, and in view of the plant identification carried out in this language it was probably the subject that young fowl learned with the greatest zeal. He acted with wise foresight: In the years to come, his mastery of Latin became the foundation for his varied self-taught studies.

Medical studies in Halle

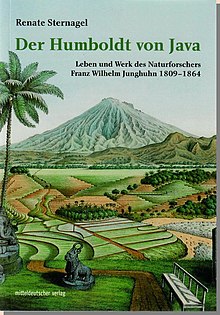

From here on, there are different and incomplete representations. The following remarks about his first years of study follow the research of the historian Renate Sternagel, which she published in her book Der Humboldt von Java .

At the end of February 1825 Junghuhn went to Halle to prepare for a degree in medicine. The lessons he received in Mansfeld were not sufficient to pass the required Abitur. Until the beginning of his studies he was taken on by the theology professor Johann Karl Thilo , from whom he presumably received private lessons. Only after passing the matriculation examination, on 1 July 1827 took place at the University of Halle-Wittenberg his enrollment .

One of Junghuhn's first biographers was the just mentioned Karl Johann August Müller, who published his 1865 lecture at the Halle trade association in the monthly magazine Die Natur , which he edited . In it you can read that young chicken “followed the siren voice of nature” and “wasted away” his medical studies with nature studies. Later biographers have apparently adopted this unchecked, and so this error has persisted into the recent past. Renate Sternagel was the first to uncover the truth about his studies in Halle by looking at Junghuhn's leaving certificate: Junghuhn not only completed all the lectures and exercises, but also attended lectures in the philosophical faculty, as medical students were one at that time for admission to doctoral studies had to take a philosophical exam. All the professors he heard from attested that he was “extraordinarily hardworking”. Young chicken was therefore making a serious effort to become a doctor of medicine.

However, Junghuhn's medical studies only served the purpose of pursuing a career as a scientifically active botanist after successfully completing it. This goal was strengthened by the influence of his nature-loving childhood friends, Oswald Heer , who was the same age, and Hermann Burmeister , who was two years his senior , who also studied entomology in Halle, among other sciences . Together they went on excursions into the surrounding area, and they often discussed the knowledge they gained with the sympathetic botanist Georg Friedrich Kaulfuss . For Junghuhn these meetings were real great moments at that time.

From 1826 onwards, training to become a “first class surgeon” was offered in Halle with practical university lectures without matriculation. The father only wanted to support financially this educational path, which was one year shorter. This would have forced his son to become a doctor, not a botanist. But after Junghuhn had enrolled for medical studies at the university against his will, he immediately stopped his financial contributions.

We don't know how young chicken in Halle managed to get on with his life for a year and a half without these donations. It was certainly a humbling time for him. He tried in vain to earn a living by doing odd jobs alongside his studies. He owed his rent and his tuition fees and had compassionate shopkeepers write down his purchases. According to Müller, he even sold his books and his bed, "from whose proceeds he could still live for a while." Finally, Junghuhn had no choice but to give up his studies on February 1, 1829 for lack of money. In his graduation certificate from the university there is the sentence formulated with academic dignity: "With regard to his behavior, it is noted that economic disorders were to be reprimanded."

Return to Mansfeld, attempted suicide

"Oscillating between fear and hope, between regret and pride, between death and life," he returned to his parents in Mansfeld. One can imagine what violent arguments he had to endure with his father. The most serious points of contention were not only his debts left in Halle, but first and foremost his steadfast resistance to training as a surgeon. A little later, the young chicken couldn't stand it at home any longer: he was botanizing, often absent for weeks, roaming Thuringia , the Harz Mountains and the surrounding area of Braunschweig , much to the displeasure of his father, who viewed botany as a useless hobby of "not earning bread" be. He now believed the future of his son to be a failure.

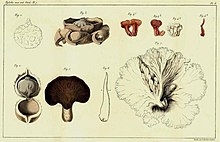

The way in which young chicken carried out its botanical forays without funds is also not known to this day. He was particularly fond of mushrooms, discovered 30 new species and wrote a scientific treatise on them in flawless Latin with two colored plates. This work by a medical student, still unknown in specialist circles, received so much recognition that it was published in the renowned botanical journal Linnaea in 1830, together with his drawings on two colored boards . That was the first "fruit" of Latin lessons from Mansfeld archdeacon Carl Ferdinand Hecht, which was probably developed to the highest degree by Professor Thilo in Halle.

Father and son remained implacable. Defiance and intransigence faced each other. Junghuhn's deep aversion to practicing as a surgeon until the end of his life in the bourgeois Mansfeld, the gloomy prospect of an uncertain future, chronic lack of money that prevented him from doing further scientific research, and - last but not least - his stubborn desire for freedom and A character striving for independence finally drove him to attempt suicide: In a vaulted cellar of the Mansfeld Castle, in front of his parents' house, he shot himself in the back of the head with a pistol.

In view of the not insignificant medical knowledge he had acquired up to then and the fact that this suicide attempt was obviously a carefully targeted grazing shot to the back of the skull, the assumption arises that young fowls do not kill themselves, but themselves just wanted to hurt, to get his father to give in and give in. However, the father felt only disappointment and regret for the seriously injured son. With the help of a doctor, he nursed him back to health. For young chicken, the time he was cared for and recovered in his father's house must have been an ordeal. The extent of Junghuhn's rift with his father can be seen from the following report: When the father was informed that a man had been wounded with a gun, he quickly dressed. But after being told that it was his own son, he put the boots back in the corner. The mayor asked him in vain to take care of his son. Only the hastily summoned district administrator succeeded in persuading the father to help. At home, the father mocked his son for the stupidity with which a budding medic had tried to shoot himself from behind. With the words “This is how he should have done it!” He tapped his forehead with his finger. - The wound that Junghuhn sustained was not without danger: In Halle a piece of skull bone "the size of a four-penny piece " had to be removed; this coin has a diameter of 30 millimeters.

Duel in Berlin, imprisonment in Ehrenbreitstein

From Easter 1830 to Easter 1833, Junghuhn was enrolled in the medical faculty of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin. Perhaps by attempting suicide his father had given up his resistance to medical school after all . Junghuhn's hope of a harmonious new beginning with him was short-lived, however, because only a few months after his matriculation an event followed that threatened to throw him completely off course.

The historian Renate Sternagel inspected the files of the Berlin Secret State Archives as follows: In a Berlin restoration, Junghuhn was called "stupid boy" by a Swiss student named Schwoerer. Young chicken replied with “infamous becket”. Schwoerer was so outraged that he asked young chicken to duel with a scimitar. Junghuhn refused because he did not belong to any of the "fighting" student associations and therefore "could not beat". They agreed to duel with pistols.

This duel took place on September 1, 1830. Junghuhn received a shot through the left thigh, while Schwoerer was uninjured. It is believed that the young chicken deliberately missed.

This act of honor was a serious offense at the time: the judiciary imposed severe penalties, not only for the opponents, but also for their seconds. Schwoerer evaded his arrest by suicide. Young chicken remained unmolested for the time being and continued his medical studies for eight months. It was only on 9 June 1831, he was the Senate of Berlin Supreme Court to ten years imprisonment convicted. At that time, however, Prussia was in a state of alarm because of unrest in neighboring countries to the west, and since Junghuhn was drafted into the military on this occasion in April 1831 and assigned to a unit of the Prussian Rhine Army in Hunsrück, the execution of his prison sentence had to be postponed. For nine months he worked as a "company surgeon" at a field battery stationed in Simmern and Laubach . His hope of a reprieve after such a long time, however, was suddenly and unexpectedly dashed: On December 25, 1831, “when the army was demobilized and put on the peacemaker” (young chicken), his commanding officer in Laubach received orders to arrest him and to transfer the Ehrenbreitstein fortress .

With this event begins Junghuhn's autobiographical report Flight to Africa , which is kindly written by his great-nephew Max Carl Paul Schmidt in his work Franz Junghuhn. Biographical contributions to the 100th return of his birthday was published (Leipzig, Verlag der Dürr'schen Buchhdlg., 1909). The text has a length of 153 pages and describes one of the most conflicted sections in Junghuhn's life in a perfectly entertaining style. To date it is the only remaining publication about this period, and that is why it is of particular value.

On January 1, 1832, young chicken was taken to the military prison at Ehrenbreitstein Fortress, bedded on straw in an open cattle wagon and taking a boat ride between ice floes across the Rhine. The worst time of his life had begun: For the ceaselessly inquiring, only 22-year-old young chicken striving for freedom and independence, for whom studying nature has been the fulfillment of his life since his early youth, there can hardly be a worse punishment than in serving a multi-year sentence in a dark dungeon in useless inactivity. What this misfortune had meant for him can only be guessed at from the following words from his work Flight to Africa :

“My pen is too weak to depict the tribulation I endured in this prison. Time crept so terribly slowly in the four bare walls, and my mind found so few points of reference in the immense solitude, so little that could be understood, that it seemed to wither [...]. One day creeps on like the other, slowly, deadly quiet, no alternation interrupts the eternal uniformity; One wakes up gloomy in the morning, only to long for the following night and to enjoy a few hours of meager sleep [...]. Since the arrest warrant had struck me suddenly and unprepared, and therefore I began my imprisonment completely bare of funds, I had to spend the months of January and February in the worst winter cold and the long evenings and nights without light, without myself on my straw under a thin blanket to be able to warm up [...]. "

In addition, there was his conviction that he was innocently imprisoned: despite his magnanimous concession, apologizing to his challenger in the event of mutual withdrawal of the insults and with this behavior according to the code of honor at the time, exposing himself as a coward, he was forced to a duel by the relentless archer. Nobody except himself was harmed in this duel. He couldn't be blamed for taking his own life after this duel. Why he should spend a considerable part of his youthful life in a dungeon under these circumstances was incomprehensible to him. Thoughts of revenge and escape arose.

After more than twelve months of imprisonment, his thoughts focused more and more on an escape. Escape from Ehrenbreitstein was impossible. Another way had to be found. At last a hopeful thought occurred to him: According to a set of rules that he knew, sick staff officers could be admitted to a hospital. Immediately he simulated a breast ailment so credibly that one felt compelled to transfer him to the Koblenz garrison hospital in the Weißer Gasse ( former Dominican monastery ) on January 20, 1833 . The living conditions were much better here, even if he was locked in a room with a barred window and a carefully locked door. Time passed faster and more pleasantly here; "[...] partly the doctors living in the hospital brought me all kinds of books and writings, partly the instruction of the surgeons' assistants, which I had taken over, scattered me [...]" (Junghuhn). However, since after months of medical treatment there were no signs of recovery, he was to be incarcerated again in Ehrenbreitstein in July 1833. In desperation, Junghuhn sent a pardon to the Prussian king. However, there was no response to this request. He then simulated a mental illness so convincingly that his relocation to Ehrenbreitstein had to be postponed indefinitely. From this point on, however, Junghuhn was aware of the impending danger of being admitted to the insane asylum in Siegburg as an incurable mentally ill .

Junghuhn owed his acquaintance with Philipp Wirtgen , who was widely recognized as a botanist in the Rhine province, to the mistrust of a military doctor . Wirtgen was asked to look at a “strange” man who had been brought from Ehrenbreitstein to the Koblenz military hospital and who showed “serious signs of mental disorder”. Since the patient was interested in the plants while walking in the garden of the hospital with an apparently scientific understanding, doubts arose as to the authenticity of his mental illness. The military doctor saw Wirtgen as the most suitable person to assess the patient's condition with the necessary specialist knowledge. As soon as the young chicken was alone with Wirtgen, he revealed himself to him and made a friendship with him that lasted until the end of his life.

Escape to France, with the Foreign Legion in Algeria

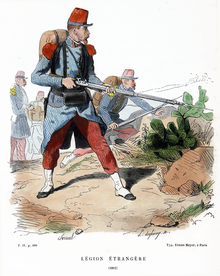

On the night of September 13-14, 1833, Young Chicken fled the hospital. He hurried to Belgium via the Hunsrück, Trier and Luxembourg, and on September 22nd he passed the French border. Only now did he feel more or less safe from being followed. He hoped in vain to get to Paris to apply for a research trip to a tropical country from the country’s scientific elite - possibly even from his role model, Alexander von Humboldt, who often stayed there. Instead, he was advised on the way to hire the Foreign Legion . In Toulon , the new goal of his 1000-kilometer escape on foot, which was full of privation, he reported to the Legion as a doctor, but was only recruited as a soldier. He had to sell his civilian clothes and put on the Legion uniform, which consisted of a red cap, blue robe, red trousers and a knapsack with a woolen blanket.

Young fowl was assigned to a department intended for use in Algeria. On December 13, 1833, together with 350 German soldiers who had almost always deserted, he went on board the sailing corvette la Fortune . Not until January 2, 1834, after 19 days at sea with violent storms, with rubble from barrels and rolling cannonballs for a life-threatening mission of the brave crew and for injuries and nausea, hunger and thirst, frost and wetness, vermin and insomnia for the Soldiers have taken care of the ship reached the north coast of Africa and anchored in the Algerian port of Bougie . Despite his stay there of only a few days, during which time he still had to help bury a deceased soldier emotionless in a quickly dug hole, we owe Young Chicken a detailed description of this place, its inhabitants and its surroundings.

On January 11, 1834, Bone was reached, the young chicken's final destination. Again we get to know Young Chicken as an observer who records everything and carefully notes: His descriptions of Bone and its inhabitants, the ruins of Hippone, Fort Caspar, the surrounding area with its vegetation, the wild and domesticated animals, Bedouin villages and those ruling Bone Diseases are among the most detailed that have ever been written about. Nothing escaped his watchful eyes, and so he described in great detail the appalling and gruesome executions of Arabs sentenced to death, whose heads were cut off with a saber. In the meantime the soldier Junghuhn had proven himself to be a knowledgeable and skilful medic: after being awarded a “doctoral diploma”, he was promoted to the rank of corporal medical officer.

An excursion into the mountains to the Phoenician aqueduct, accompanied by five armed comrades, ended after an encounter with a superior number of Arabs in a wild flight down the slope, “half flying, half falling, over gaps, undergrowth and high rock masses” and around Not to be left behind, Young Chicken had to throw away a bunch of rare plants with great regret. Another adventure was a trip for five on a boat in the Gulf of Bone, which was constantly showered by heavy surf and was in danger of being driven to an enemy shore; Younghuhn and his companions only managed to pull the sinking boat ashore with difficulty.

At the end of May 1834, the young chicken fell ill with a malignant typhoid fever with severe and very serious side effects. It was a coincidence that at the same time a French warship was anchored in the port of Bone. On June 5, after an early release due to incapacity to work, he dragged himself on board this ship and hid as deep as possible below deck because of the high risk of infection. Fortunately the wind was blowing favorably, and so the ship reached Marseille after only three days . That was the end of Junghuhn's adventure in Africa; he had European soil under his feet again.

In Marseille, young chicken was treated for eight days in a quarantine hospital and in a city hospital from June 17 to 25, 1834, until he believed he had recovered enough to want to continue his journey. With the pay for his services, he bought civilian clothes and returned his uniform to the Legion. Thanks to the attentive mediation of the conducting surgeon, who was not responsible for a trip on foot and issued receipts for the transport of a sick person, Young Chicken, still weak, traveled in stagecoaches, military transporters, on a steamship and in carts, sometimes on the paths that he took already knew from the outward journey.

As at the beginning of his escape, his destination was Paris, which he finally reached on a river steamer on July 31, 1834, after tedious detours via Toulon and Africa. In response to a request for an intermediary , he learned from the Prussian embassy there that he had long been pardoned. The pardon was issued on September 21, 1833, a few days after his escape from the Koblenz hospital. In vain was his escape, in vain his fear of being attacked as a refugee without rights, in vain his service in the Foreign Legion!

Young chicken stayed in Paris for over two months. His knowledge of French was now so advanced that he could earn a living doing translations. He hoped in vain for an opportunity to take part in a research trip as a scientist. A highlight of his botanical studies was a visit to the city's famous gardens, above all the Jardin des Plantes with its extensive collections and educational facilities.

As an enthusiastic supporter of mushroom research, it was particularly important for him to get to know the very old Dutch mycologist Christian Hendrik Persoon , whom he only found after a long search in a poor attic in a Parisian suburb. This visit proved to be trend-setting for Junghuhn's future career as a scientist: Persoon gave Junghuhn the careful advice to explore the tropical flora of the Indian archipelago; an endeavor that would take up a significant part of his life. It was probably the last, but certainly not the slightest, merit of this founder of mycology to have steered young fowl in the direction that should bring science so abundantly; two years later he died completely impoverished.

Return to Germany, start of the journey to the Dutch East Indies

On October 5, 1834, Junghuhn began his journey home to Germany. In Koblenz he went to see his friend Wirtgen. Together they went on botanical excursions to the Hunsrück, the Eifel and the Moselle valley. In November he stayed on the banks of the Laacher See . With these excursions, he bridged the waiting time for an emigration pass, which he had applied for immediately after his arrival in Koblenz. Only after two months, on December 10, 1834, was this passport given to him. Previously, Junghuhn sent an inquiry to the Netherlands, asking for information about a ride to India. The answer from the Netherlands was promising: For a voyage to explore the Moluccas, one would be prepared to take a naturalist on board.

There was no stopping young fowl: after receiving four louis dor from Wirtgen , he set off on his journey to the Dutch East Indies.

The most important source for the following remarks is: In memory of Franz Junghuhn. Letters from young chicken to Ph. Wirtgen. Provided with a foreword and notes and edited by M (ax). Koernicke. In: Negotiations of the Natural History Association of the Prussian Rhineland and Westphalia, 66th year 1909 (ed. 1910), pp. 276–326; named "Letters to Wirtgen" in the footnotes.

Junghuhn has not visited his hometown Mansfeld again. Well aware that he might never see his parents and siblings again, he went on a steamboat from Koblenz to Rotterdam. Following friendly advice from Wirtgen, he made two breaks on the way: In Bonn he met the botany professor Theodor Friedrich Nees von Esenbeck , who gave him a letter of recommendation to Professor Blume in Leiden, and in Cologne he was a guest at the court pharmacist and botanist Johann Friedrich Sehlmeyer.

The louis d' or borrowed from Wirtgen was running out, and so he had to use the cheapest and slowest means of transport from Rotterdam, a trek barge that was pulled through inland canals or pushed forward with poles. Junghuhn still had no inkling of his new hardship: he had to wait far too long in Koblenz for the emigration pass. In The Hague , he learned from the Colonial Ministry that the ship destined for the Moluccas , on which he was supposed to sail as a scientist, had left on December 6, 1834, four days before receiving this passport, and that the advance payment granted for him had been canceled. "[...] In vain did I visit Minister Van den Bosch, he was in Amsterdam and the other officials laughed at me when I talked about the advance [...]". In an express letter to Amsterdam, he asked the minister to be allowed to go on another ship to India.

How fundamentally different his life would have been if not again - for the first time before his escape - the "Prussian white-collar" trotted a little faster!

Junghuhn's cash was finally over. He hiked on foot to the city of Leiden, 22 kilometers away . On the basis of the letter of recommendation received in Bonn, he put all his hopes for further support in the director of the Leiden Imperial Herbarium , Carl Ludwig Blume . The effect of this letter was not lacking: Blume received him in the most friendly manner, gave him "advice and action", proudly showed him his magnificent work Flora Javae , led him personally through the imperial herbarium and filled his empty purse with 55 guilders advance on, "(...) he is the loveliest man in the world."

In Leiden, the colonial minister told Junghuhn that his appointment as a scientist was not possible until further notice. But the impatient young chicken was not ready to wait an indefinite period of time with insufficient income. Only as a doctor was there an opportunity to enter the Dutch-Indian service. Resigned, he wrote to his friend Philipp Wirtgen: "I had no choice but to flee under my old grandmother's petticoat, the medicine, and take an exam in Utrecht ."

This ends the confused chapter about young chicken's youth, and great deeds followed. Junghuhn's great-nephew Max Carl Paul Schmidt said: “Life's wheel was ruthlessly tinkering with it. But in the end it turned out: the brittle stone on which it cut was, despite its rough exterior, a diamond. ”.

At the end of this chapter, let me look back at the first sentence of the preliminary remark, according to which followers of Junghuhns are convinced of similar abilities as those of Humboldt. Perhaps they are not entirely wrong, because the difference between the young chicken's conflict-ridden youth and that of the well-protected Alexander von Humboldt cannot be outdone in terms of upbringing and training, two of the most important factors for a person's development. In addition, there were the various means available: Humboldt, wealthy and independent, was able to prepare his memorable trip to South America for six years with specialist scholars in Geneva, Weimar, Jena, Dresden, Vienna, Salzburg and Paris; Not only did he have the energetic botanist Bonpland at his side, he also had fifty of the most expensive and modern instruments with him, which had to be carried by six servants and nine mules. Junghuhn, on the other hand, was alone and poor at the beginning of his research, like the proverbial "church mouse": As a permanently employed paramedic in military service who had to obey the orders and instructions of his superiors, he could neither prepare nor plan his first trips, and when measuring the the first volcano he had climbed, he had to be content with a barometer made by himself from the simplest of ingredients.

Junghuhn's report Flucht nach Afrika ends with his return to his home country and closes with his stay at the Laacher See. The first chapter Journey to Holland in his work Topographical and Scientific Journeys through Java begins with his stay at the Laacher See and is thus a seamless continuation of the escape .

First stay in the Dutch East Indies (1835 to 1848)

Java (1835 to 1840)

For the destitute young chicken, the Dutch East Indies could only be reached with a job in the local army . After successfully completing a medical exam on December 27, 1834 in Utrecht, he received a permanent position as a third-class medical officer on January 12, 1835 . Financially provided with only the bare essentials, he waited for six months in Harderwijk , a meeting place for sailors, soldiers and recruited emigrants, on the scenic south bank of the Zuiderzee . The repayment of the four Louisdor borrowed from Wirtgen was a major financial burden. It was not until June 30, 1835 that the three-master Jacob Cats left Hellevoetsluis for Java , and on the morning of October 13, 1835, after a three-and-a-half month crossing, the young chicken set foot on the landing site in Batavia, today's Jakarta . It was only 13 years later that he returned to Europe - albeit temporarily - to restore his health.

- Arrival on Java

Contemporary view of the Sunda Strait in front of Anjer harbor .

Young chicken first served as a doctor in the military hospital in Batavia. However, the fact that he botanized the tropical surroundings in every free hour and recorded his impressions and observations in pictures and words soon aroused the displeasure of superiors and colleagues and brought him numerous complaints about neglect of duty.

In February 1836 he was transferred to Jogjakarta . During a vacation from May 20th to May 26th, he traveled through the karst area on the south coast of Java, known as "Gunung Sewu" ("Thousand Hills") because of its numerous cone mountains . West of Jogjakarta he studied the erosive forces of the weather on the Gunung Gamping limestone massif, and in September 1836 he began his fundamental investigations of the most dangerous volcano on Java, the Merapi , which rises north of Jogjakarta and at that time possessed a threateningly steaming cinder cone. He repeatedly climbed this almost 3,000-meter-high mountain and documented it in words and pictures down to the smallest details. He determined the heights with a self-constructed barometer, consisting of a bamboo tube and a suitably calibrated glass tube, which had to be constantly held vertically while on the move. He achieved astonishing accuracy with it. The Merapi and the 3145 m high Merbabu immediately to the north were the first volcanoes that Junghuhn climbed.

In 1837 Junghuhn's research life was finally steered on the right track: He was placed under the German doctor Ernst Albert Fritze . He was head of the health system in the Dutch East Indies and - as head of the natural history museum of the "Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen" - himself to a great extent enthusiastic about nature. Without his help and official courtesy, he would have remained a paramedic in hospitals. Fritze recognized Junghuhn's inclinations and abilities and took him on two inspection trips as an adjutant.

It can be safely assumed that the latest and best instruments were taken with them on these trips: hammers for knocking off and examining boulders, drums and boxes for collecting plants, binoculars, thermometers, barometers and psychrometers and - especially important for young fowl - All kinds of paper and pens for sketching and writing down what has been explored.

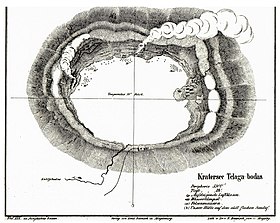

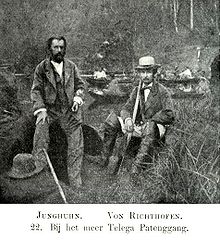

The first trip, from July 11th to August 23rd 1837, was through West Java. After visiting the lonely Wijnkoopsbaai on the south coast (today's name: Pelabuhan Ratu ) and the mountain lake Telaga Patengan, which is still surrounded by untouched forests, the volcanoes Patuha, Tangkuban Perahu , Guntur, Papandayan , Galunggung and Ciremai were climbed. The careful examination of the milky-white crater lake Telaga Bodas, which was visited after the descent from the summit of Papandayan on the other side of the valley of Garut, should be emphasized. Fritze dealt with geology, collected rocks and calculated the heights, young chicken dealt primarily with botany and recorded the results of all research with sketches and words in his diary.

- From Junghuhn's Atlas on a journey through Java

During the second inspection trip, which ran through central and eastern Java from April 12 to August 15, 1838, eleven volcanoes were examined: the Ungaran, the Lawu, the Sumbing , the Sundoro , north of Jogjakarta - one more time for young chicken. the Merapi, the Wilis, the Ringgit, the Lamongan, the Tengger Mountains with the active Bromo , the Dieng Plateau, interspersed with craters and lakes, and the second highest peak in Java, the 3428 m high Slamet . In addition, there were two mud volcanoes south of Surabaya and a non-volcanic eruption cone in a swamp near Ambarawa, which had been created by hydrostatically pushed up moor in a hard peat layer.

- Young chicken's first trips ...

Junghuhn undoubtedly acquired a basic knowledge of geology on these trips. After the end of these trips, Fritze tried to give him the opportunity to continue doing natural research without his companion. His recommendation to Pierre-Médard Diard , the head of the Natural History Commission in Batavia, gave Junghuhn an assignment to carry out scientific research in West Java. By accepting this order, young chicken was exempted from the medical service for the time being, but had to involuntarily accept the obligation to hand over the results of its investigations to the commission.

In October 1838 he climbed the Gunung Salak volcano southwest of the city of Bogor (then Buitenzorg) . The detailed report he wrote about it, which was published in the same year in Dutch and in 1840 in German, was the first publication in German translation with which Junghuhn brought the tropical nature of the island of Java to his countrymen back home.

On April 1, 1839, young chicken entered the 3,019 meter high Gunung Mandalawangi, the highest peak of the Gedé-Pangrango volcanic massif . Here he discovered, to his great joy, "... one of the greatest botanical rarities and plant-geographical peculiarities ...", a primula which - in contrast to the small Primula veris known in Europe as " cowslip " - reaches a height of one meter and only rises this mountain thrives. Immediately on the spot he named her Primula imperialis .

The second ascent of the Pangrango followed in July 1839 and the third in November 1839. In the last section of his first major work, Topographical and Scientific Journeys through Java , he recorded the discovery of the Primula imperialis as well as the botanical, zoological and meteorological observations on this massif . In between, in October 1839 before his third visit to the Gedé-Pangrango, Junghuhn examined the extensive mountain range of the extinct Malabar in the Preanger landscapes south of Bandung .

Junghuhn was very keen to publish his newly acquired knowledge as quickly as possible. He attached great importance to the fact that this should be done under his name and that no other researcher was able to distinguish himself with the results he had achieved. All the more since he learned that Carl Ludwig Blume, who had received him warmly and benevolently in Leiden and supported him with an advance payment of 55 guilders, repeatedly adopted the results of other researchers and published them under his name. Secretly, disregarding his obligations to the Natural History Commission, which Blume had constantly worked on, he sent his first reports with sketches and drawings and a small herbarium to the professor of botany Theodor Friedrich Nees von Esenbeck , whom he had met during his trip to the Rhine in Bonn . But after he died of tuberculosis during a spa stay in southern France in December 1837, Junghuhn's shipment to Breslau was forwarded to his older brother Christian Gottlieb Nees von Esenbeck , who in 1818 was elected President of the renowned Imperial-Leopoldine-Carolinian German Academy of Natural Scientists (Leopoldina) has been. However, the search for a publisher for these content-rich reports remained so long without any prospect of success that Junghuhn, fearful of losing the priorities of the first discoverer, gave up the rest of his work, starting with the description of his second journey with Dr. Fritze, in the negotiating vat het Bataviaasch Genootschap van kunsten en wetenschappen wanted to publish. Fortunately, nothing came of it, and so Junghuhn's manuscripts did not appear until 1845, but in one piece: It was his first major work Topographical and Scientific Journeys through Java , including an atlas with views, sketches and elevation maps, "promoted to print and foresaw" by Christian Gottlieb Nees von Esenbeck. There is still no coherent edition of this work in the Dutch language, and thus also the atlas belonging to it.

Not one of Junghuhn's numerous excursions would have been possible without the use of local porters. In addition to the indispensable devices and measuring instruments for his scientific observations, containers for mineral and vegetable objects, drinking water and provisions had to be taken along. For overnight stays on the peaks of the high volcanoes, in cold and drafty weather above the tree lines, firewood was needed for hot meals and for a warming fire. On his first trips in 1836, which Junghuhn undertook of his own accord in his irrepressible urge to explore, he had to pay for his helpers from his own resources; a fact that later turned into the opposite: During his travels with Dr. Fritze, and on behalf of the colonial government, each village chief had the duty to provide porters and a local guide and - if necessary - to have a walkable path laid out in difficult-to-penetrate terrain with possibly a hundred or more helpers.

Sumatra (1840 to 1842)

The death of his superior and benefactor Dr. Fritze on May 13, 1839 was a painful loss for young chicken. He was still in military service as a medical officer. His request to continue his work with the Natural History Commission was rejected. Apparently they had meanwhile been informed that he had secretly shipped scientific results out of the country; a circumstance that would have a detrimental effect on him in later years. On January 3, 1840, he completed the exam to become a "second class surgeon" in Batavia. He used a vacation from March 1st to April 3rd for health reasons to explore the Diëng Plateau in Central Java.

“However, I saw with horror the end of my vacation and the hospitals in perspective. Now that I heard that Mr. Merkus, Read of India, a very scientific and humane man whom I had met earlier, had been appointed Commissair General of Sumatra, I asked to be transferred to Sumatra, which I asked too was granted. I went to Padang via Batavia , and was so happy to be commissioned by Mr. Merkus with the topographical and natural study of the Batta lands immediately after my arrival ... ”(young chicken).

However, this order contained numerous instructions: A map was to draw young fowl of the region, research the climate and the fertility of the soil, find usable soil and other natural resources, and test types of wood for their suitability for shipbuilding. He should not only gather information from the Batak about their political attitudes, language and script, customs and traditions, but above all about their notorious cannibalism. He is supposed to report back every three months. It was an extraordinarily risky undertaking: apart from a few widely scattered Dutch military bases, which were more or less tolerated by the residents in order to protect them from Islamic conquerors, the country was still completely independent, and the prospect of an unwelcome intruder was eaten up at the time as a deterrent Becoming wasn't exactly encouraging. And yet: Exploring an unknown country was so tempting for Young Chicken that he immediately gave up the hated medical service. The natural scientist Hermann von Rosenberg was assigned to him as his assistant .

- Arrival in Sumatra

The fort on the island of Pontjang Kitjil, starting point for the trip to the Batta countries. - From: The Malay Archipelago by Hermann von Rosenberg .

Direct access through the hinterland of Padang was denied to the two researchers because of a previously suppressed uprising. Then they drove north along the west coast of Sumatra on a British merchant sailing ship. On October 2, 1840, the ship entered the bay of Tapanuli and anchored in front of a Dutch outpost that had been built for strategic reasons on the offshore island of Pontjang kitjil (today's name: Poncan ketek). Here they made their final preparations.

A short time later, Junghuhn made a serious mistake: while he was still busy with the topographical survey of the Tapanuli Bay, he sent the inexperienced "newcomer" from Rosenberg to the Dutch base in Lumut. This base could only be reached by boat across the bay and on land through dense jungle. Von Rosenberg used the waiting time until the arrival of the young chicken to go hunting in the area. On one of these excursions, on the afternoon of October 14th, von Rosenberg got lost while chasing a rare bird. Only after spending several hours alone in the forest in fear, at 11 p.m. the following night, was he found by shots and shouts from young fowl and brought back to Lumut by his servants. As a result of this shocking event, von Rosenberg had such a violent attack of fever that he had to acknowledge the accompaniment and assistance of the young chicken. This was an irreplaceable loss for Junghuhn: von Rosenberg would have been the only person in the Batta countries who had received a scientific education in his home country and with whom he could have spoken in his native language.

Without his assistant as a discoverer and scientist completely on his own, Junghuhn continued his research in the southern battal countries. Of course he wasn't really alone, he would only have survived a few days in this wilderness. Aware of entering an independent country where cannibalism is said to be widespread and in which there was a risk of being attacked by hostile tribes at any time, he had made sure that he was accompanied by a small armed force. This can be seen from the following quote:

"Since the various Radja's are seldom in agreement with one another and very often diverge in their way of thinking, so that a traveler, while being treated hostile by one, finds support from the other, the benefit of a small one comes from this armed might emerge. I therefore armored my very steady servants, who in peacetime are nothing less than soldiers but rather peaceful people (bird stuffers, insect catchers, tree climbers, plant seekers) with their percussion rifles and carried two pistols themselves in their belts. My walking stick was a lance! In addition, two Radja's accompanied me with their servants, who were also armed with rifles, so that I was able to fire ten shots at a time. Fifteen porters of my luggage, my plant paper and my instruments usually closed this train. "

The penetration and measurement of these undeveloped areas made the highest demands on his physical and mental performance. Threats from suspicious locals, who had been afflicted by warlike Malays a few years before his arrival and who refused to be intimidated by his armed force, severely hampered Young Chicken's work and prevented further advance northward.

The obstacles young chicken faced on his travels can be seen from his following words:

“In Tobah, where there are wide, completely flat spaces, I was threatened with refusing to measure base lines because this was considered to be a land survey for fortresses to be built! - For similar reasons, in Hurung I could only make my observations from the bushes, hidden and secret, - in Silindong I was forbidden from measuring the heights of the sun in an artificial horizon, because this was pure magic; I was urged to pack my sextant and pack myself out of the country. - Then there is the mountainous impassability of the country; there is no other step than to come on foot; - In a day you sometimes have to wade through 30 to 40 brooks, some of which are very warm (which are trodden in the valley floor) and others immediately afterwards (flowing close to the foot of the mountain) and, if you stand up to your armpits in the water, your own Hold instruments above your head. - In the woods one is plagued during the day by small jumping leeches, 20-30 of which suck themselves on all parts of the body at the same time and cause painful ulcers sticking through the footcloths, and at night by mosquites. Finally, with all this one must still take constant care of personal safety, and even at night in the huts, where one finds a hard bed with a little corn and potatoes, at least 6 rifles loaded and alternately keep watch with his servants to keep the natives through To scare away fear ... "

This was not long without consequences: of the 18 months that young chicken spent in Sumatra, he was ill for ten months without medical care in his camp at the military base Tobing on a southern foothill of the Lubu Radja volcano. Countless leech bites had infected his legs. There was also dysentery . He fell behind with his quarterly report. At times he felt so bad that he asked to be transferred back to Java.

All the more astonishing is what he was able to achieve in Sumatra in the remaining eight months in a reasonably healthy condition. Despite the Batak's distrust and the difficulties that this posed, he managed to explore all aspects of their culture and everyday life. The second volume of his work Die Battaländer auf Sumatra with the subtitle ethnology comprises 388 pages .

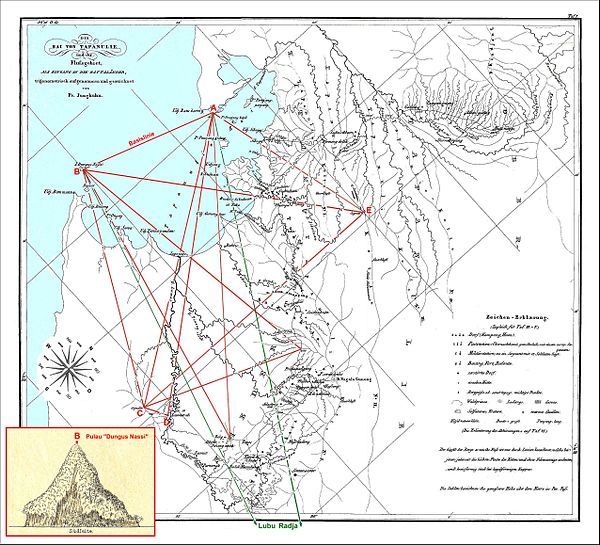

In addition, there was the surveying and mapping of the southern Batak lands. Immediately after his arrival in the Bay of Tapanuli, Junghuhn selected two prominent main points for a geodetic baseline , determined their geographic coordinates using astronomical latitude and azimuth determinations and calculated their distance, converted to the current system of measurement, to be 14.3 kilometers. On this basis, he created a geodetic surveying network through angle measurements and pole height determinations . With this achievement, which according to Montigel must be counted as "one of the greatest acts of human willpower", Junghuhn has earned the merit of having carried out the first triangulation in the Dutch East Indies. The value of this pioneering act is increased by the fact that it did not take place on the much better developed island of Java, but under incomparably more difficult conditions in the jungle-covered mountains of Western Sumatra. It was only 50 years later that the Dutch colonial government succeeded in subjugating this inaccessible area.

- "The entrance to the battalands"

Young chicken map of the Tapanuli Bay.

The sea surfaces are colored light blue; the original is not colored. The projection of the map has rotated Young Chicken by about 48 ° to the northeast; a compass rose was therefore added later.

In addition, the first trigonometric bearings are entered; these bearings are not shown on the original map. Points A, B and C represent the corners of the base triangle. B is located on the 240-meter-high island "Dungus Nassi" (today's name: Pulau Situngkus); See Junghuhn's sketch from the south at the bottom left. Point D had to be defined as an auxiliary point for a further baseline to A, since many locations could not be targeted from C. An important starting point for inland bearings was E. To the right of point A, the small island of Pontjang Kitjil is shown; the fortified trading post on this island was the starting and ending point of young chicken research on Sumatra.

The following map excerpts, which cover approximately the same area, are intended to illustrate the geographical and topographical advances made by young chicken in the battalion countries.

One of the best maps of Sumatra before young chicken explorations is that of the English historian and orientalist William Marsden , who was stationed as secretary in Bencoolen, now Bengkulu , on the west coast of Britain . For eight years Marsden collected all oral and written reports on Sumatra and summarized them in his monograph The History of Sumatra . The section shown here was photographed from the map that is in the authoritative third edition of this work published in 1811. On this map the mountain ranges are shown as they could be seen from the ship when passing the west coast; the chains drawn behind it come from the imagination. A map published by Heinrich Berghaus in 1837 did not contain any better information for the battal countries.

In contrast, the general map of central Sumatra in Junghuhn's work Die Battaländer contains a wealth of new discoveries. “It was an arduous work to produce it with primitive tools; for the time it is a significant improvement of the known and for the first time gives an accurate picture over wide stretches of unknown country ”(Wilhelm Volz). The illustration of the parallel valley "Mandaheling", whose northern continuation "Nieder-Ankola" from the extinct volcano "paved the way for later travelers, both for the Viennese Ida Pfeiffer and for the first missionaries, some of whom had to pay for their advance with their lives" Lubu Raja ”is completed. In addition, this map contains the earliest representation of Lake Toba , even if only hinted at according to reports from locals, called "Eik Daho" or "Laut Sinkara" by the young chicken. It was not until eleven years later, in 1853, that the Dutch linguist Herman Neubronner van der Tuuk was the first European to stand on the shores of this lake. In contrast, the 1200 km long chain of islands off the west coast of Sumatra, from Simeuluë in the north via Nias and the Mentawai Islands to Enggano in the south, has been omitted from this map: These islands were not explored by young fowl; this was done by Hermann von Rosenberg, the “newcomer” who had to be left behind in Lumut due to a fever attack and who, after his recovery, became one of the most successful naturalists in the Malay Archipelago.

For comparison, the map of the topographic service, which was created after decades of precise surveys, has been added.

- The battalands in Western Sumatra before and after young chicken discoveries

On the same sea route that Junghuhn had chosen for the outward journey, he left the bay of Tapanuli on March 10, 1842 on board a merchant sailing ship. The most dangerous, hardest and most deprived months that he had passed in the Dutch East Indies lay behind him. In the truest sense of the word "at the end of his strength", he returned to Padang on March 18, 1842. He was given a leave of absence until June 10 to recover from the exertions he had endured. On June 11th he went on board the steamship Nula , which reached the roadstead at Batavia five days later. Illness and exhaustion prevented him from fully completing the instructions received from Merkus. In his work Die Battaländer ... he wrote resignedly that he was heading for Sumatra with “swollen hope” and left Sumatra 20 months later with “torn sails and broken hope”.

The stay on Sumatra has undoubtedly affected the health of the young chicken and cost several years of his life. The dysentery that forced him to spend ten months in a sick bed never let go of him. He fought pain with alcohol and opium.

Java (1842 to 1848)

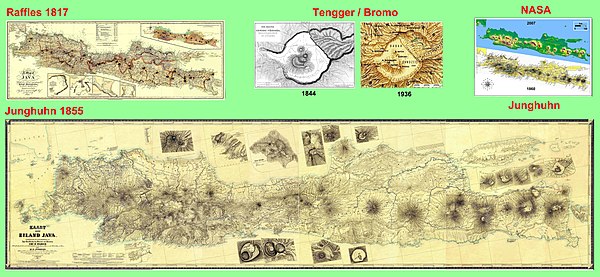

The collapse of the United East India Company in 1799 drew the attention of the British to the Dutch East Indies , and after a British fleet had blocked the port of Batavia for three months as early as 1800 and the Dutch naval power at Surabaja was destroyed in 1807, the commanded in 1808 Dutch Marshal Herman Willem Daendels requested the fastest possible preparation of an overview map of Java for strategic reasons. It was not until 1812, after this island had briefly passed into the possession of the East India Company , that this map was completed by Thomas Stamford Raffles and published in his work The History of Java in 1817 . It is mainly based on the information provided by the American researcher Thomas Horsfield . Raffles had, however, incorporated numerous map sketches with very different qualities from other travelers and colonial officials who had been instructed for this purpose. Errors and inaccuracies in putting them together were inevitable, despite all efforts. There was also the lack of a trigonometric basis. The Raffles Java card was highly decorative, but useless for the colonial administration and the colonial army.

This strategic and political background contributed to the fact that Junghuhn was not allowed to remain active as a health officer, but as a natural scientist. Pieter Merkus , appointed provisional on October 3, 1840 and definitively appointed Governor General of the Dutch East Indies on October 11, 1842, released him from hospitals until further notice. Probably the most important reason for this measure was Merkus' interest in the results of the investigations commissioned by him into young fowl in the battal countries. In order to be able to evaluate these results in peace and seclusion, the colonial government provided the young chicken with a house in the western Javanese town of Cianjur, at a climatically favored altitude east of the Gunung Gedè volcano.

He took his time: The manuscript of his work Die Battaländer auf Sumatra is dated “September 1844”. The reason for this long processing time, which was therefore more than two years, was the impatient resumption of research on Java, in which, in addition to botanical and palaeobotanical studies, the topography of the island increasingly came to the fore. For example, just a few days after his return from Sumatra in July 1842, he stayed for the fourth time, and this time for a full ten days, on the 3000 meter high summit of Pangrango. In 1843 he published articles on the history of the volcanoes in the Indian archipelago and on Hindu antiquities in West Java, with results that could only be achieved with extensive travel. In the hope of gaining more useful knowledge about the still little-known interior, young chicken was given a free hand and continued to be exempted from the unpopular medical service. The most fruitful years of his life followed.

During his first trips, Junghuhn discovered that all available Java cards were useless for him because of serious inaccuracies. The same was true of the aforementioned map, which he thought was the best: Raffles and Horsfield's Map of Java . "My first effort was [...] aimed at designing an improved position map of the volcanoes of Java on the basis of this work by Horsfield and Raffles [= the Map of Java ]" (Junghuhn, Java, Volume 1, p. 79).

This resulted in a feat of strength that is unparalleled in the history of cartography: to design a map of the largely undeveloped, over 1000 kilometers long and up to 200 kilometers wide island without trained helpers, which also provides a traveler with a map of the interior of the country provides reliable guidance. With this ambitious goal, Junghuhn was occupied with the topographical survey of West Java until August 1844, then with that of East Java. As before on Sumatra, young chicken was the first on Java to work with optical triangulation. Equipped with a bussole and a sextant , which he later replaced with a bussole theodolite, he aimed at all prominent points, particularly from the peaks of the volcanoes.

The result of this show of strength is the Kaart van het eiland Java , which, together with the large Java plant in the Netherlands, far from Java, was created from an enormous amount of written and sketched records. Only after its completion was it possible to compare the progress of this card with that of Raffles. This comparison is therefore made in the next chapter “Convalescent stay in Holland”.

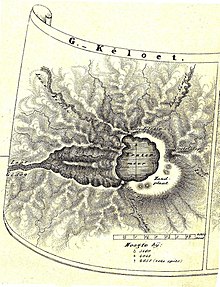

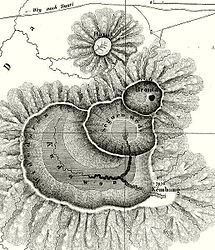

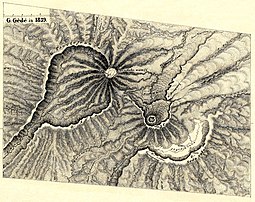

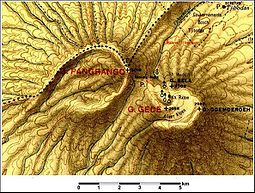

A permit had to be obtained for the trip to East Java - it was the last young hen was allowed to do on its own initiative. In September 1844 Junghuhn climbed the Kelut, which was feared by the residents in the area . This mountain looks comparatively insignificant on the map, but in the ranking of the most dangerous volcanoes in Java it took second place behind the central Javanese Merapi. In the time of the young chicken, the Kelut crater contained a lake with almost 40 million cubic meters of water. With every major eruption this lake was thrown out; the resulting devastating lahars streamed down into the densely populated lowlands and have cost the lives of around 20,000 people since the volcanic activity of this mountain began to be recorded. Only three and a half years later, on May 16, 1848, young chicken would have been irretrievably lost in the same gorge in which it climbed to the crater from the west. The next volcano we visited was the neighboring Kawi, where a Hindu temple suggested a long rest. Younghuhn then climbed Java's highest mountain, Semeru , which was almost constantly active at the time . An in-depth investigation of the already in July 1838 with Dr. Fritze visited the Tengger Mountains followed, among the results of which the map of the crater shown below can be highlighted. In the easternmost district of Java, Banyuwangi , rises the 3332 m high Raung , which the young hen climbed together with the inspector from Bondowoso on October 12, 1844; the look into the huge craters enclosed by vertical walls made him shudder involuntarily. The depiction of the Ijen plateau with the crater lake Kawah Ijen occupies an important space in Junghuhn's large Java work , especially because of the long description of the great eruption of the Ijen in 1817. On the return journey, Junghuhn visited the enormous massif of the Iyang-Argapura, On the plateau of which he discovered an animal paradise with thousands of almost tame deer, then the comparatively tiny Lamongan, which he could only view from below for the second time due to non-stop activity, and the third highest volcano in Java, the 3339 m high Arjuno .

Junghuhn's detailed recordings of volcanic peaks and mountain ranges were made with remarkable accuracy. Below are two examples: The caldera of the Tengger Mountains with the active Bromo and the Gede – Pangrango volcanic massif with the also active Gedé . Excerpts from exact maps based on surveys of the topographic service are used for comparison.

Junghuhn's attention to detail when recording areas of particular scientific interest was particularly noteworthy. Another example of this: the map of the Diëng plateau. It was not until 32 years later, in 1877, that a new map of this plateau was published by Pieter Johannes Veth; no significant progress can be seen.

- Diëng plateau

The young chicken was in mortal danger several times: on the Ringgit he stood unarmed against three tigers, on the Sumbing and on the Raung he climbed overhanging crater edges with breakneck climbing, on the summit of the Lawu he would have died of thirst and starvation if not the leader of his carrier column Had found a path leading down into the valley, on the summit of Semeru, which was then active as a Strombolian, he fearlessly determined the height of the outbreak cloud during another eruption, vividly described the dust-swirling rolling of glowing stones on the slope of the mountain and quite deliberately ignored the possibility of even one to be hit such a stone; its porters had long since left it. In this context, the "Gunung-Guntur" board in his landscape atlas should also be mentioned; the brittle crater rim with the escaping vapors fell into the depths only a few years after his visit. The investigation and measurement of the first volcano he climbed, the highly active Merapi north of Yogyakarta, was a life-threatening undertaking because of the heavily steaming cinder cone that had already been pushed up by the magma. Today this most dangerous volcano in Java is monitored around the clock with the most modern instruments.

With regard to the written and cartographic material available on Java up to that point, Junghuhn's results can be described as “groundbreaking”. With his countless bearings and laborious height measurements, the topographical and orographical knowledge of this island was placed on a new basis. In addition, Junghuhn's basic observations in the areas of botany, climatology, geology and volcanology are added. In recognition of this versatility, he was called by his admirers “pioneer in India”, “great Indian botanist”, “capable Indian geologist”, “famous discoverer of Java's mountains” and “gifted writer”. The most honorable attribute posthumously received, "Humboldt of Java", has been preserved to this day.

Driven by his desire to end his medical-military career and to be employed as a naturalist, Junghuhn published numerous monographs on Javanese volcanoes in the Tijdschrift voor Neêrland's Indië and in the Indisch Magazijn in 1843 and 1844 . These treatises, which contained a wealth of precise descriptions of mountain peaks that were still little or not yet known at the time, contributed to the fact that within a short time his skills as a nature observer were known to the highest levels of government. One of the first to step on the scene was Pieter Merkus, who had commissioned the young chicken in 1840 with the exploration of the battal countries on Sumatra. By decree of January 17, 1844, he approved a sum of 6,000 guilders for the publication of the results of the research commissioned by him. However, Merkus died unexpectedly on August 2nd, whereupon his successor withdrew this post. In addition, one remembered with full appreciation a work published as early as 1841, in which Young Chicken had recommended the higher-lying areas of Java with their moderate climate as a place of rest for Europeans suffering from tropical heat. As a result, several high-altitude health resorts emerged, including a sanatorium in the village of Tosari on the northern slope of the East Javanese Tengger Mountains as one of the first of these places.

Finally the time had come: on November 2, 1844, Jean Chrétien Baud , Minister of the Colonies in The Hague , authorized the Dutch-Indian Governor General to accept him as a member of the Natural History Commission. But it took another six months before Junghuhn's long-awaited wish was finally fulfilled: It was not until May 5, 1845 that he was honorably discharged from military service and employed as a scientist by the Natural History Commission.

With that, Young Chicken, at the age of 36, was rid of the medical career that his father had imposed on him. At the same time, however, a new phase in his research life began for him with fundamental changes: if he had carried out all scientific research on Java on his own initiative and financed it with his own resources, he had to immediately give up this independence and follow the instructions of the Dutch obey Indian colonial government. This subordination to superiors authorized to give instructions was a turning point in the life of this freedom-loving nature lover that was difficult to accept. On the other hand, Junghuhn enjoyed numerous advantages: The second-class instruments could be exchanged for the best and newest, expenses for porters and guides were compensated with generous travel expenses.

The substantial increase in salary, from 180 guilders a month, which he earned as a medical officer, to 350 guilders a month for a natural scientist, was of little consequence, since he had already received a daily allowance of 12 since his return from Sumatra - albeit without the officer's salary Had received guilders. Much more important to him was his ultimate reputation as a naturalist and the knowledge that he would never have to work in a hospital again.

Rough in personal dealings and polemical in his publications, Junghuhn made many enemies. Although a staunch supporter of the colonial system, he criticized its abuses with often biting mockery. A high point in the resulting chain of conflicts, which ran almost uninterrupted until the end of his life, was a rift with the colonial government in 1845: In an eyewitness account of tigers against buffalos and about the stabbing of tigers in the popular play Rampok allowed Junghuhn made improper remarks about the Susuhunan of Solo , with whom one had to cultivate diplomatic relations in order to prevent riots. Young chicken was given a serious reprimand: if he made any similar statements again, he would be fired and expelled from the country.

The audience described by many biographers with Governor General Jan Jacob Rochussen , to which Young Chicken is said to have been invited on this occasion, did not take place; he was not in office at the time. The main characters in this conflict were rather Wolter Robert van Hoëvell as editor, Cornelis Visscher as Dutch-Indian general secretary and the acting governor general Jan Cornelis Reijnst. Van Hoëvell came to Java in 1836 and found with regret that almost nothing had been achieved in the literary field in 200 years of colonial rule. There was still no book trade, and the only available scientific journal, which, however, appeared very irregularly and in some years not at all, was the negotiators van het Bataviaasch Genootschap . There were also only two daily newspapers, the "Javasche Courant" and the "Soerabaja Courant", scientifically undemanding organs of the colonial government. Convinced that the European population had fallen short of education in the colony, van Hoëvell asked the government for permission to publish a scientific journal. The Tijdschrift voor Neêrlands Indië, founded in 1838, was given permission with the condition not to criticize the government in any way .

In order to explain more about the aforementioned scandal with the government, it is necessary to look back in Junghuhn's Vita . In August 1844, before his employment with the Natural History Commission, Junghuhn went on a research trip to East Java. He wrote down his observations and results in twelve sequels under the title Schetsen, ontworpen op eene nieuwe reis over Java, voor topografische en natuurkundige navorschingen . The following year, van Hoëvell began to publish these “sketches” in the Tijdschrift voor Neêrlands Indië . With his second sketch, Junghuhn already provided a source of conflict that led to serious disputes between the editor and the colonial government: Van Hoëvell considered his sharp criticism of the lavish excesses of the local regent of Bandung to be so questionable that he decided to use this "sketch" for examination and assessment sent to Visscher. This immediately confiscated Junghuhn's criticism and questioned van Hoëvell's suitability as editor. With the aim of having the Tijdschrift voor Neêrlands Indië forbidden, Visscher carefully studied the continuations of Young Chicken. In the tenth sketch he finally found the material that seemed to him to be indispensable for a ban on this magazine: Young chicken's description of the court of Solo , with sarcastic remarks about the killing of the tigers and the courtly ceremonies connected with it. On June 20, 1845, only three weeks after Junghuhn was admitted to the Natural History Commission, he presented this description to the acting Governor General. Thereupon, by decree of July 4, 1845, van Hoëvell was placed under the curate and young chicken was given the above-mentioned written warning.

On September 30, 1845, almost three months later, Jan Jacob Rochussen took office as Governor General. At the request of van Hoëvell, Rochussen arranged for the decree to be withdrawn. There is no record of whether Rochussen reprimanded young fowl. If so, this reprimand must have been mild, because shortly afterwards he received a government contract from Rochussen to look for coal fields in Java that could be mined. This enabled young chicken to undertake not only topographical, but also geological, mineralogical and palaeobotanical research in the still little-visited south of the island with the best possible support . He recorded the results of these investigations in the third volume of his Java work.

Convalescent stay in Holland (1848 to 1855)

Bad health from his strenuous excursions, Junghuhn traveled to Europe on a convalescent vacation in August 1848 with the so-called "English Overland Post". From his handwritten notes about this trip it is clear that he first went to his hometown Mansfeld. Of his parents, only his mother was still alive; his father had died four years earlier.

Junghuhn first took up residence in The Hague , but shortly afterwards moved to Leiden , which with its university with a rich library and its own botanical garden offered him the best work opportunities. He sold his botanical, geological and palaeontological collections to the university, but on the condition that they could not be transferred to the Imperial Herbarium, with whose director Carl Ludwig Blume he was involved in never-ending disputes. His herbaria were therefore examined by botanists who had not been under the influence of flowers. The results of their investigations were published in the works Plantae Junghuhnianae and Plantae Junghuhnianae Ineditae .

Younghuhn himself evaluated his own notes on Java. The result is his main work, "the real work of his life": Java, its shape, plant cover and internal structure . The printing of the second section in the first volume, which describes the landscape and vegetation character of Java, was postponed until the very end, in order to be able to incorporate the botanists' botanists from Leiden up to then.

On January 23, 1850, Junghuhn married the 22-year-old officer's daughter Johanna Louisa Frederica Koch, who lived in Leiden. In the same year he traveled with her to his mother, who had moved to Fischbach in Silesia after the sale of her parents' house in Mansfeld . In Koblenz he introduced his wife to his old companion Wirtgen .

At the beginning of 1852, young chicken was commissioned by the Dutch Colonial Minister Charles Ferdinand Pahud to transfer the seeds and saplings of the cinchona tree from the South American Andes to Java. Junghuhn refused because of overwork and suggested to the colonial minister that the German botanist Justus Karl Haßkarl should be sent there. An unheard of audacity towards the Dutch authorities! With the request to be allowed to finish his Java work and, what was even more important, to add a reliable map, he got Pahud's agreement to finish his work in the Netherlands. To safeguard his rights, he took Dutch citizenship on September 30, 1852 .

Despite the work on the work and on the map, Junghuhn is said to have had time to go on study trips to almost all countries in Northern and Central Europe, to the Pyrenees, the Alps, Sweden and the Caucasus, and according to some biographers even to the Central Asian Altai. These trips must all have taken place in July 1849 and in the months May to August 1850, since these are the only periods for which the young chicken's stay in Leiden is not documented. Only trips to Germany were proven beyond doubt: to Mansfeld, Koblenz, Fischbach and Berlin. On the side, however, he put his life and world views and his free-spirited thoughts on church and religion on paper: The first delivery of the Licht- en schaduwbeelden uit de Binnenlanden van Java ... (light and shadow images from the interior of Java ... ) appeared anonymously in 1854 .

In the last paragraph of his Java work, Junghuhn announced a topographical map, "[...] on a scale of 1 to 350,000, divided into 4 sheets, of which the engraving will be completed within a year." Junghuhn kept this promise: the work appeared in 1855 , which has finally established his fame as an explorer of Java: The Kaart van het Eiland Java . This masterpiece contributed to the fact that, on the recommendation of Alexander von Humboldt , young chicken was allowed to participate in a dinner in Sanssouci Palace with the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. On August 21, 1855 .

To see the extent of the improvements in Junghuhn's map, one can compare it below with the basis for his work, the Map of Java published by Raffles in the previous chapter :

Detail from a blackboard that was exhibited in Bandung and Jakarta from November 2009 to January 2010. The full-size presentation of the Map of Java by Raffles and the Kaart van het eiland Java by Junghuhn enabled a direct comparison of both maps. - With the aim of keeping the height of the map as low as possible, Junghuhn has depicted the island of Java almost horizontally.

A comparison with sections of the same area on a scale that is as similar as possible from the interior of Java is clearer. The valley of Garut in the west of the island was chosen for this. In order to achieve the same size representation, the Raffles map had to be enlarged about 2.7 times. - The map of the young chicken has been moved to the north , as the map of het eiland Java is turned to the northeast. This map created for the Netherlands was labeled in Dutch, in which, for example, the “oe” in the German language corresponds to a “u” and “Tj” to a “C”: Goentoer = Guntur, Garoet = Garut, Tjikoerai = Cikurai.

The Raffles card cannot be used for any purpose due to serious inaccuracies. The mountains and ridges are patches and shadows in entirely inappropriate locations. The only reference points for the delimitation of this map were the place Leles in the north, the names “Mt. Talaga bodas ”and“ Galung gung ”in the east and the mountain“ Chikura ”in the south.