Freiburg (Breisgau) main train station

| Freiburg (Breisgau) central station | |

|---|---|

|

View from the Stühlingerbrücke onto the tracks and today's train station complex

|

|

| Data | |

| Location in the network | Crossing station |

| Platform tracks |

|

| abbreviation | RF |

| IBNR | 8000107 |

| Price range | 2 |

| opening |

1845 historical building |

| Profile on Bahnhof.de | Freiburg__Breisgau__Hbf |

| Architectural data | |

| Architectural style | functionalism |

| architect | Harter + Chancellor |

| location | |

| City / municipality | Freiburg in Breisgau |

| country | Baden-Württemberg |

| Country | Germany |

| Coordinates | 47 ° 59 '52 " N , 7 ° 50' 28" E |

| Railway lines | |

|

|

|

| Railway stations in Baden-Württemberg | |

The Freiburg (Breisgau) Hauptbahnhof station is the most important rail traffic hub in southern Baden . This is where the Rheintalbahn (Mannheim – Basel), the Höllentalbahn ( Freiburg –Donaueschingen) and the Breisacher Bahn (Freiburg – Breisach) meet.

With around 38,300 travelers per day, it was the fifth largest train station in Baden-Württemberg in 2005. According to Stiftung Warentest , in 2011 it was the second most punctual of 20 important train stations in Germany after Stralsund .

The main train station is on the western edge of Freiburg's old town, about one kilometer from Freiburg Minster , at Bismarckallee 5-7. The Freiburg Konzerthaus , two hotels , the Freiburg Jazzhaus and the Xpress office complex built in 2008 along the railway line on the former express property are also located on this axis to the south .

history

Construction and inauguration in the 19th century

In 1838 an extraordinary state parliament decided to build the Badische Hauptbahn from Mannheim to Basel . The first draft law, which State Minister Ludwig Georg von Winter presented there on February 13, 1838, did not contain any information about the locations to be connected. This draft was referred to a commission, which presented its results on March 5th. During the debate, MP Karl Georg Hoffmann (1796–1865) stated, among other things, that “Freiburg in particular [could not stay on its side and should an additional expenditure of 500,000 florins be necessary”). The final version of the law on the construction of a railway from Mannheim to the Swiss border near Basel , which the Grand Duke Leopold of Baden enacted at the end of March 1838, explicitly named Freiburg as an en-route station on the railway line to be built.

The “great Comtoir of traffic with the whole Oberland ”, as the deputy Johann Georg Duttlinger Freiburg called at that time, caused further political discussions and brought the planners of the railway more worries than any other city in the Grand Duchy. This statement by Karl Friedrich Nebenius referred to two major challenges that the connection of Freiburg with the initially single-track line between Offenburg and Basel presented : The city of Freiburg is not only off the relatively straight line between Mannheim and Basel, it is also located higher than all other cities connected to the Rhine Valley Railway, e.g. B. 308 Baden feet or 92.4 meters higher than Kenzingen, 25 kilometers to the north .

Alternative routes that would have led either from Riegel to Hartheim or from Kenzingen to Biengen near Bad Krozingen through the Rhine Valley without Freiburg would have been much shorter. In addition, the locations on these lines would have had a lower height difference than the solution implemented in the Freiburg Bay and up to the foot of the Black Forest . According to a statement by the Freiburg MP Karl von Rotteck (in the context of the debate about the explicit naming of cities in the law), however, it "goes without saying that it [the line] passes near Freiburg, but not past Gottenheim or Umkirch" . A net incline of 365 feet from Offenburg and a net incline of 54 feet to the Swiss border had to be overcome. Gradients of more than 0.5 percent were associated with major restrictions for the operation of the railway.

The Commission's proposal to start construction of the line in Mannheim, Freiburg and Schliengen ( Isteiner Klotz ) at the same time was not complied with at the time. They wanted to wait for the experiences from the construction of the line from Mannheim and the methods found to facilitate the work and also to maintain a certain flexibility with regard to the route. According to the law of 1838, however, the preparatory work should at least begin immediately, "so that the railway is nowhere stopped in its progress". After those responsible had ruled out an area near Lehen at the height of today's A5 motorway as being too far from Freiburg for the construction of a passenger station, they decided to relocate the track system on the flat rayon of the former Vauban fortification belt west of the city. There was enough space here for an extensive railway system. With this solution, however, the greatest incline of the Baden main line of 1: 171 (0.58%, according to other information 0.53%) was accepted. This was only possible because the leveling of the area began as early as Köndringen and this continued later to Schallstadt .

The railway line reached Offenburg on June 1, 1844, but construction of the section from Riegel to Freiburg had already begun in 1841. In 1843, when the foundation stone was laid for the Freiburg train station, the locomotive Der Rhein from the mechanical engineering company Karlsruhe was transported over the highway to Freiburg. On July 22, 1845, the first six-car train drove to Freiburg on a trial basis, pulled by the Class III c locomotive Der Kaiserstuhl . Another test drive followed on July 26th with the Kepler locomotive , a type V model that brought 700 people in 21 cars to Freiburg.

On July 30, 1845, the station was inaugurated in the presence of Grand Duke Leopold and his son Prince Friedrich . In addition to politicians such as the Baden Foreign Minister Alexander von Dusch , the Minister of the Interior Karl Friedrich Nebenius and Friedrich Rettig , officials, mayors and officers of the citizen corps from the cities that the train - led by the Zähringen locomotive - had already crossed with musical accompaniment by the guard regiment were present . When the train reached Freiburg at 12:40 p.m., Mayor Friedrich Wagner greeted the guests in the unfinished station building , while cannons shot salutes on the Schlossberg . As early as August 1845, 1,474 travelers arrived in Freiburg in the new express coach and 1,682 people left the city by train, which from then on ran five times a day. While the stagecoach line between Freiburg and Offenburg was closed with the opening of the railway line, there was three daily service between Basel and Freiburg and vice versa. One of the first famous passengers at Freiburg Central Station was probably Franz Liszt , who drove from Heidelberg to Freiburg on October 16 of the same year to give a concert there the following day . The freight transport also started in the summer 1845th

With the completion of the section in the south to Schliengen in 1847, the provisional terminal station had to give way to a through station with a second track, also in order to cope with the increased volume of traffic. The rail connection to the north to Rastatt and Karlsruhe played a decisive role in the Baden Revolution in 1848 , when troops loyal to the government and Hessian troops as well as heavy military equipment were quickly moved to Freiburg in order to suppress it in Breisgau .

Expansions up to the First World War

The “Bahnhof bei Freiburg” was initially outside the city, as the Lerch plan from 1852 shows. Initially it was only accessible via the extended Bertoldstrasse, which was called Bahnhofstrasse until the reception building was completed in 1861 . With the construction of the station, Freiburg finally grew out of the narrowness of the Vauban fortress belt, when hotels , restaurants and the central post office settled along the railway road and filled the space between the city and the station. With the development plan Hinterm Bahnhof, the city of Freiburg created the prerequisites for today's Stühlinger district . Businesses and factories soon settled there, some of which had been displaced from the districts of Herdern and Wiehre , which had meanwhile been designated as villa quarters .

During the 1870s , the Badische Bahn expanded the station to include waiting rooms , utility rooms and an atrium . In the aftermath of the annexation of Alsace after the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, they hurried to connect the Reichsland with Freiburg via the Freiburg-Colmar railway , which made a third track and a second platform necessary. The Elztalbahn branching off from the Rheintalbahn in Denzlingen was opened to Waldkirch in 1875 and continued to Elzach from 1901 .

In 1885, rail traffic in Freiburg had increased so much that two new halls were built after the old platform hall was demolished. The rail-like crossing was replaced by a bridge that - inaugurated as the Kaiser Wilhelm Bridge at the time - is now called the “ Wiwilí Bridge ”. In the course of the renovation in 1885/86, the underpasses that still exist today were also built, of which two stairs lead to each platform.

The station was given the rank of Hauptbahnhof with the commissioning of the Höllentalbahn and Wiehrebahnhof in 1887. This soon took first place for passenger traffic between Freiburg and the Black Forest , but because of the higher tariff rates compared to the main station, it was only used as a freight station for the nearby ones Districts meaning.

Towards the end of the 19th century , the freight halls and loading bays of the main train station hardly corresponded to the traffic that had increased by around 20 percent since 1878. Therefore, between 1901 and 1905, a separate freight station and the 11 kilometer long freight bypass between Gundelfingen and Leutersberg were built to relieve the main line.

Growth in the Weimar Republic

The station facilities for handling passengers have been criticized frequently since the beginning of the 20th century . There were complaints about the insufficient number of tracks, which meant that arriving and waiting trains had to share one of the three tracks more often. That this meant a source of danger was shown, for example, in 1924 when an arriving suburban train drove up to the waiting early express train. The station building was also a target of criticism, as the Freiburger Zeitung called it a “mousetrap”. In addition, the number of passengers had increased massively in line with the population development of Freiburg im Breisgau : while 1,340,954 tickets were sold in 1900, this number of tickets sold had almost doubled in 1919.

For this reason, there were already plans in 1910 for a completely new construction of the station area, in the course of which the entire platform area was to be built over. The first plans envisaged an entrance hall made of natural stone with a length of 90 meters and a depth of 8 meters, which was to be crowned by a high dome. However, the beginning of the Second World War delayed the almost completely planned new building "until further notice". The preparatory work necessary for the new building, which resulted in a complete separation of passenger and luggage traffic , could still be completed.

In addition, by 1929 it was possible to set up a storage and locomotive station between Dreisam and Basler Strasse. This made it possible to create space for additional approach tracks and platforms, as the locomotive sheds and workshops that were located west of the main train station could now be relocated there. Today is located on the site of the DB Regio - work Freiburg. The space created was used to build two more platforms in 1929 and 1938. The first of the two was eight meters wide and 270 meters long. For the first time, the water drainage on the roof was installed in the middle and no longer took place over the roof slope. The platform also brought with it the installation of a mail elevator.

In the course of the work, Basler Strasse was moved 50 meters to the side and about six meters lower. So the two tracks of the main line, a pull-out track and the two tracks of the Höllentalbahn, which was re-routed from November 8, 1934 , could be led over the street on three new bridges and no longer had to cross them. Together with those of Albertstraße (the underpass is now called Mathildenstraße ), Lehener Straße (both 1905) and Höllentalbahn (1934), the most dangerous level crossings within the city were eliminated.

Despite the cramped conditions in the station, luxury trains arrived at the station early on: the Amsterdam - Engadin Express began operating in the summer of 1901 . However, it did not have a long lifespan. Much more successful was the introduction of the “ Rheingold ” on May 15, 1928, which stopped at the main train station until the start of the war on September 1, 1939 and finally even led over the Gotthard to Naples . On May 15 of that year had the Reichsbahn one speed rail cars operating over Freiburg with the compounds Basel (DR) - Dortmund (FDt 49/50) (operation with DR 137 273 ... 858 ) and Basel- Berlin Anhalter Bahnhof (FDt 33/34) started, which was also discontinued at the beginning of the war.

Second World War and its aftermath

Through the promotion of road traffic in the Third Reich (e.g. through the construction of the Reichsautobahn ), the number of tickets sold in Freiburg had also decreased massively by the beginning of the war. This decrease increased further with the beginning of the war, when from 1940 on the government ordered the Reichsbahn itself to advertise not to use the railway. Civilian passenger traffic had to be restricted because the railway was used during the war. From March 1942, the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda threatened people who “use the Reichsbahn for pleasure, which is overloaded with essential war transports, with heavy fines and the transfer to concentration camps .

On the night of October 21-22, 1940, the Gauleitung in southern Baden had 450 Jews from Freiburg and the then Freiburg district deported from the freight hall of the train station to the Gurs camp as part of the Wagner-Bürckel campaign . A memorial on the Wiwilí Bridge has been a reminder of this since 2003 .

As in the First World War , when the air raids by the French did not cause any significant damage to the railway systems, the main station was also the target of two bombing attacks at the end of the Second World War. This time, however, the consequences were palpable: The British air raid Operation Tigerfish on the city on the evening of November 27, 1944 destroyed all of the overhead contact lines , a large part of the track system and almost the entire main building. The clock tower, which was the only component to survive the evening, collapsed after a second hit on February 8, 1945. The marshalling yard and the depot were also badly affected.

As early as 1945, the Badische Hauptbahn resumed operations under pressure from the American occupation forces, in whose occupation zone the northern part of the line was located. On September 7th, the restoration work came to Freiburg, followed by the route to Basel by November 5th . However, the French occupation troops replacing the Americans ordered the dismantling of the Offenburg – Freiburg – Müllheim and Radolfzell – Konstanz sections on a single track in order to weaken traffic on the right bank of the Rhine and thereby strengthen the importance of the French State Railways ( SNCF ). In fact, this measure was limited to the Offenburg – Denzlingen section, and so Freiburg was spared the renovation. The number of train connections that passed Freiburg on the way to Offenburg, however, was now significantly lower than that directly after the opening of the railway line, 100 years earlier. In addition, the majority of the few trains were only allowed to be used by Germans in third class until May 14, 1950. In 1952, twelve pairs of express trains were again in service on the main line.

On August 1, 1945, limited suburban traffic by freight trains with third-class passenger transport was started. Of these, only the line from Norsingen (Rhine Valley Railway going south) led to the main station; the two from Denzlingen (north) and Hugstetten (Breisacher Bahn) stopped in the marshalling yard, the line from Himmelreich (Höllentalbahn) ran from Wiehre station. Only when the damaged tracks and the Loretto tunnel of the Höllentalbahn, which had been blown up by the retreating Wehrmacht , were restored on December 19, 1950 , could the Wiehre be reached on two tracks again from the main station. Swiss negotiating skills had already made the main line passable again in October.

The state railway of the French occupiers also decided in 1945 to continue the 50-Hertz test operation on the Höllentalbahn, which had started there from 1936 to 1944. With the electrification of the Badische Hauptbahn from 1952 with 15 kV 16 2/3 Hertz , the system was divided in Freiburg from the end of May 1955. In order not to have to switch to 50 hertz locomotives, steam locomotives pulled freight trains from the Freiburg freight yard on their way to the Höllentalbahn through the main station. This system separation existed for a full five years until the trial operation on the Höllentalbahn was discontinued. The two-system operation also made it necessary to set up an eighth platform track. Since the electrification of the main line took place from Basel, the class E 10 electric locomotive , which pulled the opening train to Freiburg on June 4, 1955, had to be towed to Stuttgart by a class 38 steam locomotive one day later .

The clean-up work on the main building did not begin until autumn 1947 and progressed slowly due to a lack of personnel and materials until the currency reform in 1948 . Instead of being rebuilt, Freiburg Central Station was given a temporary reception building, which was the first in a major German city after the war. The opening took place on November 9, 1949 in the presence of the Baden State President Leo Wohleb . Between 1985 and 1986, on the occasion of the Freiburg State Garden Show, the interior of the building was extensively renovated, after work on the building had already been renewed in 1955/56.

This time, too, the debate about converting or rebuilding the station was to last several decades, and this time too the press was very critical of the existing structure. According to the Badischer Zeitung , the “building is a disgrace for the major and tourist city of Freiburg” and represents “a provincial 'nest' rather than a city with 160,000 inhabitants”.

In the period that followed, designs were created that provided for a multi-level pedestrian platform over the tracks into the city center. In addition to the long-distance railway, an underground tram and bus station were planned. The Technical Town Hall, which was later realized in Fehrenbachallee, was also to be built above the tracks, next to it 7- to 15-storey high-rise buildings with cinemas , department stores, cultural and congress centers and underground garages . A financing plan presented in 1965 by the chief construction director Hans Geiges provided for the sale and leasing of the entire site and the airspace. The Federal Railroad approved the project in 1969 in order to obtain more track area for the expansion of the Rhine Valley Railway. However, the 40 million DM project Bahnhofsplatte , for which the city had already found investors, failed in the Freiburg city council in October 1970. In the course of the discussion about the construction of a new culture and congress center, the architect Manfred Saß (who later became the master builder of the cathedral) presented the design of a new main train station with an integrated congress center . This envisaged a 115-meter-long structural slab , which was 4.5 meters above the tracks and was to accommodate 12-meter-high hall buildings. The costs, put at 86 million DM in 1978, could not be raised without additional sources of money. In the same year, the resignation of the Prime Minister of Baden-Württemberg, Hans Filbinger , who had lived in Freiburg for a long time, worsened the prospects for state funding. Since the Federal Railroad did not want to finance major projects in the wake of increasing competition from air traffic , it asked in 1980 that negotiations be suspended.

Meanwhile, operations at the station continued: the German Federal Railroad had resumed both the express railcars and the Rheingold . The fastest train to stop at the station in 1960 was the Trans-Europa-Express Helvetia , which reached a top speed of 140 km / h.

The number of tickets sold at the main train station was 1,355,590 (plus 29,491 in Zähringen and 11,745 in Herdern) roughly on the same level as at the turn of the century or in 1935. However, the sales figures were just as declining as those in the entire Karlsruhe Federal Railway Directorate. In the summer of 1960, 163 passenger trains ran on the Rhine Valley Railway (49 express trains and long-distance express trains, 25 express trains), 36 on the Breisacher Bahn (10 multiple units) and 48 on the Höllentalbahn (12 express trains) on work, Sundays and public holidays.

On September 26, 1971, with the entry into force of the winter timetable section 1971/1972 in Freiburg, the InterCity era began: the station was part of the then IC network of the Deutsche Bundesbahn from the outset with line 4 from Basel to Hamburg-Altona station .

With the inauguration of the Stühlinger Bridge south of the reception building in 1983, the tram network was also expanded. The neighboring Wiwilí Bridge was no longer sufficient for traffic. Before that, the tram also drove past the main entrance on Bismarckallee. With the new bridge, all tracks are barrier-free . Elevators lead to every platform ; the ICE platforms 1 and 2/3 are also connected with an escalator . They had been expanded for September 27, 1992, when the first Intercity Express stopped at the main train station on schedule on its way to Switzerland . Again and again they fail because of a defect.

Way to today's new building

Despite the failed plans for the station plate with the congress center, it was the final decision to build the concert hall in 1988 that set things in motion: a subsidiary of the Federal Railroad took the decision to build the new InterCity Hotel , which, as work progressed, took place in 1990 a complete redesign of the entire area was expanded. However, the authority at the time, the Deutsche Bundesbahn , saw itself unable to cope with the necessary investment volume and therefore launched an investor competition under the direction of the architect and urban planner Albert Speer junior . Nine proposals were received from seven investors. The winner was the Waldkirch architects Harter und Kanzler with the construction company Bilfinger Berger as investor. In the discussion that followed, citizens and public officials raised concerns about the draft. They criticized the plan of the closed development (block development) and its consequences for the ventilation and lighting in the Stühlinger district, the planned building heights (especially that of the two office towers), the formation of a pedestrian underpass, the overall appearance and the expected traffic load resulting from the There would be a large number of parking spaces under the station. With regard to the climatic effects on the Stühlinger, a climate report was commissioned in June 1992, which resulted in a 15% reduction in ventilation in the Wentzingerstraße area. Therefore, the city administration insisted on an approximately 14-meter-wide opening in the building, the so-called wind window, in order to ensure a better exchange of air between the city center and the Stühlinger. All of these processes meant that the design had to be revised again before the Freiburg municipal council could (re) adopt the "Bahnhof" development plan on June 22nd .

The demolition in February 1997 created space for the new building after 50 years of temporary work. Among other things, the Corinthian columns had to give way, which had supported the two platform roofs on platform 1 since the renovation in 1885/86. A complicated height adjustment of the roof stood in the way of reuse, and so the railway gave away the columns. Part of it went to the Wutachtal Museum Railway , at whose Weizen station one of the old platform roofs was completely rebuilt. The city stored the remaining columns in the building yard of the civil engineering office until they were used as decoration for a beer garden near the train station in summer 2010 . The Stühlinger Citizens' Association criticized this location: He considered the columns to be his property and would have preferred to see them in a neighboring green area.

The new main train station was opened on September 29, 1999; the entire line of the station followed on July 18, 2001. Although only intended for long-term lease , the investor Bilfinger Berger acquired the property after the new building, which was a first for Deutsche Bahn. While Deutsche Bahn takes on the leasing of the rooms adjacent to the railway area, the rest of the building complex is therefore rented out by Bilfinger Berger.

Connecting bridge in the "wind window"

VarTec Telecom Europe Ltd. , a subsidiary of VarTec Telecom Inc. from Dallas , rented office space on both sides of the "wind window". For this purpose, Bilfinger Berger installed a glass corridor on the sixth floor in 2000 without the knowledge of the city administration, which has spanned the “wind window” ever since. The city did not approve the footbridge at first and had an expert report on the impact of the footbridge on the ventilation conditions obtained at Bilfinger Berger's expense. This came to the conclusion that the footbridge “has only a relatively minor impact on ventilation compared to the overall dimensions of the structure”. These effects were quantified as 0.5% for the glazed walkway and 0.2% for a variant without glazing. Due to the slight impairment of ventilation and in order not to endanger the settlement of Vartec, which promised 400 jobs, the footbridge was not demolished. A fine procedure was initiated which resulted in the payment of 70,000 DM .

An additional condition for the preservation of the footbridge was “that the respective tenant occupies the entire area of the adjacent floors of the building sections”. At the end of 2004, the British Carphone Warehouse Group acquired VarTec Telecom Europe from the insolvent parent company. At the end of June 2005, the VarTec call center, which at that time employed over 120 people, was closed. The prerequisites for maintaining the footbridge were no longer in place, so that 2007 had to be renegotiated. The city promised to continue to tolerate the footbridge if it were to be dismantled within two months of the expiry of the rental agreements on the adjacent areas.

May 31, 2017 was agreed as the latest date for the dismantling. Since the lease was still in place, Bilfinger Berger asked the city in 2017 to continue to tolerate the footbridge. The city administration decided to legalize the footbridge if it were designed to be more air-permeable and if Bilfinger Berger accepted the construction burden of not building any further connecting footbridges . The footbridge had not yet been redesigned by spring 2020, but the new 45 meter high Volksbank building is now rising east of the wind window. The city claims this will not affect air circulation. Dirk Schindler, professor at the Institute for Environmental Meteorology at the University of Freiburg , has doubts. Because the building owner has not yet implemented the redesign of the footbridge, the building law office announced that it would examine the next steps.

Changes since the turn of the millennium

In 2001, a DB Dialog call center for over 60 employees was set up on an area of 500 m² .

In September 2002 the main station was part of the Deutsche Bahn project to set up smoking areas at the 63 largest IC / ICE stations in Germany. It was not until five years later that such areas became required by law . On January 29, 2003, at 11:00 a.m. at the main station, the ICE 3 01 was christened Freiburg im Breisgau . In 2004, the Bahn Call Center was closed along with seven other of the company's 13 call centers at the time.

In 2009, around 250 trains stopped at the main station every day, and 60,000 passengers got on or off each day. In addition, another 50 to 150 trains per day passed the station without stopping. This means that the capacity limit has largely been reached, especially since the number of travelers has doubled since 1979.

architecture

The first reception building in the arched style with neo-Romanesque elements was built in 1845; a temporary solution after its destruction in 1944/45 lasted 50 years. It wasn't until the turn of the millennium that it was replaced by an ensemble of a station hall , shopping center and hotel and office towers.

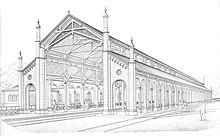

First building (1845–1945)

The two-storey reception building, built according to plans by the architect Friedrich Eisenlohr , was characterized by many neo-Romanesque building elements in the historicizing style . As with the other more important train stations, the building in Freiburg was implemented in a round arch style, which explains the preferred use of round arched wall and arcade openings. The building thus blended seamlessly into the row of train stations that Eisenlohr placed along the existing railway line:

“The representative stone entrance buildings with their block-like structures, flat hipped roofs and symmetrical facade structures are in the tradition of classicism. In the tradition of his teacher Heinrich Hübsch , Eisenlohr prefers exposed stone and uses the round arch style for wall and arcade openings. In addition to classical ornamentation , he uses Gothic ornamental forms. "

By doing without plaster, Eisenlohr intended, according to his own statement, "material that is visible everywhere and real construction that is undisguised, and the formation of forms based on it, so no pseudo-form but truth". He used reddish sandstone to highlight the protruding facade elements on the otherwise light wall background. The station building was 70 meters long, 40 of which were two-story. One reached its vestibule via one of seven arches, which were located between two side elevations and were formed by " pilasters like pilasters ". These architectural stylistic devices are also related to antiquity and the early Renaissance inspired by it. A tower clock rose above the roof turret, which in early drawings was crowned by a "graceful spire". After the spire was later removed, which can already be seen in photographs from around 1910, the monument curator Manfred Berger found the clock “even more like a foreign body on the otherwise balanced structure”. The offices of the railway employees as well as rooms for the telegraph office and the post office were on the ground floor. On the second floor there were apartments for railway employees.

Between the platform hall and the station building there was an open courtyard with a fountain, modeled on a Greek and Roman atrium . On its sides were the rooms necessary for travel, including the three waiting rooms for the first to third class. In contrast to many other station buildings at the time, this connecting structure was arranged across the tracks. So Eisenlohr managed to leave the platform hall and the station building as separate architectural units despite the connection. However, the travelers had to accept a longer walk.

The platform hall was 110 meters long, 16.30 meters wide and a ridge height of 12.30 meters, the largest in Baden. It consisted of three naves in the style of a basilica , the roofs of which could easily be drained to the outside. This was an improvement on the Mannheim main station , which consisted of only two ships and which had problems with drainage. The slate roof rested on a construction made of local wood, as Eisenlohr had decided not to use the expensive cast iron for reasons of cost. Nevertheless, this station, like many other Baden stations, was initially criticized by the estates “for its opulence”.

The front walls of the hall were also made of red sandstone, the side walls of white brick. The building was visually lengthened by arranging columns between the pillars, which doubled the number of openings. The upper cladding was continuous and partially exposed the supporting structure. The gable-sided pillars were covered with Gothic pinnacles . Its weight gave the building additional stability in order to withstand the stress caused by the wind attacking the sides. There was a turntable in the hall; Mail wagons could be loaded and unloaded directly, as the horse-drawn vehicles could drive up to the track.

When the freight station was not yet spatially separated from the passenger station, free loading had to take place using the existing loading tracks and loading lanes on both sides of the station as much as possible. On the west side of the station there were larger loading bays and the loading cranes, with the exception of a large gantry crane . The freight halls were on the east side of the station. The reception goods hall also contained the customs warehouse . The reception and dispatch hall were each 99 meters long and only 13.5 meters wide. The express goods hall had a storage area of 640 m².

The only remaining buildings of the first station complex are the two listed car halls between Wenzingerstraße and platform 8 from 1845.

Second building (1949–1999)

The lack of financial resources, building materials and construction machinery meant that an architecturally complex solution was ruled out from the start. Therefore, it was decided to continue using the foundations and the basement that had remained intact. On this basis, a floor plan was created with a solid central building and two low side wings in lightweight construction , which could later have been extended to a single storey or replaced by multi-storey buildings. The building was designed by Oberreichsbahnrat and architect Walter Lay .

The steel construction of the skylight of the old building had also withstood the attack. By reusing the component measuring 15.60 × 12.40 meters, the central part of the building could be supplied with sufficient natural light, which would otherwise not have been possible due to the height of the hall, which was only 5.5 meters. In contrast to its predecessors, the waiting rooms were no longer sorted according to ticket class, but differentiated between smokers and non-smokers. In memory of the old train station, a clock tower was placed on the roof.

The main hall, which was built between 1947 and 1949 for 300,000 DM by the construction company Bilfinger Berger , was recognized in the Badische Zeitung for its "extremely clever floor plan", in particular due to the fact that only 30 meters between the platform and the forecourt was available for construction stood. With its 520 m² area, the hall was even larger than its predecessor. The English magazine The Railway Gazette also described the building in 1950 as "not only adequate for the purpose, but also architecturally satisfactory".

Third building (since 2001)

The temporary structure was torn down and replaced by a completely new building. With a gross floor area of 40,000 m² and a gross volume of 230,000 m³, the new reception building is significantly larger than the old complex. The construction cost a total of 61.4 million euros.

Its core consists of two buildings, each with six floors (22 meters high) and a length of 275 meters on the track and 265 meters on Bismarckallee, as well as two office towers with a height of 44 and 60 meters respectively. You are across the street from Eisenbahnstrasse or Rosastrasse. The taller of the two towers is the second tallest building in the old town after the Freiburg Minster .

Above the second floor, the two buildings are connected by a glass roof, under which the reception hall and the adjoining market hall with DB travel center are located. In addition, there are a large number of restaurants and shops in the market hall and on the gallery above . The remaining floors, together with the two office towers, offer 25,000 m² of office space. The Kagan , a combination of café , bar and disco, was located on the two upper floors of the higher tower until February 2018 . The Neko (bar and club) opened there in autumn 2018 .

Escalators and a glass elevator lead from the reception hall to the basement, where there are also shops. From there, all platforms , the underground car park and the central bus station can be reached. A staircase and elevator lead to the opposite side of Bismarckallee and Eisenbahnstrasse, which leads to the city center. On the other side of the underpass there is access to the Stühlinger district via a ramp and stairs to Wentzingerstraße.

The underpass is illuminated by a skylight that rises about one meter above the space between the reception building and the InterCity Hotel. According to the architects, the free-floating canopy of the reception building quotes the roof of the concert hall; According to the investor, the two towers refer to the Freiburg Minster and the two city gates ( Martinstor and Schwabentor ). To the north of the higher tower, the third to sixth floors of the building on the track side are interrupted by the “wind window”, which is intended to ensure an improved exchange of air between the inner city and the Stühlinger.

The facade of the building largely relies on transparency through the use of glass , but the west side is kept rather dark through the use of prefabricated parts. The two towers are equipped on the south side with a photovoltaic system according to the plans of Solarstrom AG , which was made larger than planned to compensate for the connecting bridge in the wind window. It brought the Waldkirch architects Harter und Kanzler recognition at the presentation of the 2001 photovoltaic architecture prize from the state of Baden-Württemberg , which was awarded by the Energy Information Center of the Ministry of Economic Affairs:

“The photovoltaic system of the Freiburg train station tower is a sign that can be seen from afar on a building with high symbolic power, which was one of the flagship projects for the presentation of solar energy use at Expo 2000 . The building gains visual power through the visual conciseness of the solar cells. In connection with the high level of publicity, this also justifies the use of the facade for solar energy generation - despite the associated lower system efficiency due to the less favorable orientation. "

The Freiburg Planetarium is housed in the former Ufa Palace at the north end of the complex.

Track systems

The main tracks of the Freiburg main station consist of two tracks each for the Rheintalbahn and the Höllentalbahn, as well as the one track of the railway line to Breisach. Between the tracks of the Rheintalbahn and Höllentalbahn there is a depot with a storage station that supplies the Höllentalbahn, the Rheintalbahn between Basel and Karlsruhe and, since 2004, the Black Forest Railway with rolling stock . Locomotives of the series 363 , 146.1 and 146.2 and some double-deck cars are currently at home in BW Freiburg. The locomotives of the class 143 were still used on the Höllentalbahn until December 10, 2016 . The 111 series disappeared from Freiburg together with the n-type cars on June 5, 2011. There are two groups of points in the Freiburg depot, and another is located between the depot and the platforms. The tracks cross the Dreisam and several streets and lead under two bridges. The Höllentalbahn also crosses the Rheintalbahn. Deutsche Bahn has sold its post loading station, which it only used for a few years . After EK-Verlag had parked its vehicles in the halls, the Postbahnhof was demolished from January to July 2012.

Signal box technology

The L90 electronic interlocking from Alcatel (today: Thales ) has been in use on the west side of the station since September 20, 1998 . The operator stations for the electronic interlocking are now located in the DB Netz operations center in Karlsruhe. In addition to the main train station, traffic to the signal boxes in Wiehre , Leutersberg , Denzlingen and Gottenheim is controlled there. About 70 signals and 40 turnouts can be operated from there. In addition, the signal box was part of the CIR-ELKE pilot project between Offenburg and Basel from the start.

Before the new interlocking was inaugurated, there were smaller electromechanical interlockings of the type E43, the name of which denotes their first year of construction in 1943: Stellwerk 1 in the north (formerly surrounded by the Freiburg Planetarium), Stw 2 behind the Wiwilí bridge, Stellwerk 3, the largest, in the direction of Dreisam . At the beginning of the 20th century, the three predecessors of these interlockings had to operate 15 signals and the majority of 113 points. Initially this was done mechanically until the turnouts and signals were electrified in 1931. In 1932, Freiburg received a new command station, which at that time only had the capital Karlsruhe in the Republic of Baden . From this point on, this command signal box controlled and secured the entire operation. The individual interlockings remained in place, but could only operate the signals if the command interlocking had released them. The transmission of approval and the route locking were done electrically. The routes and thus the main signals were dependent on the command switchboard. The handling officers on the platforms no longer had any direct influence on the moving operations; from this point on they were only responsible for handling trains.

The Heidenhof signal box on Breisacher Strasse was also closed in 1998. The shunting operations in the area of the depot was done by the now abandoned and demolished signal box 6 at the depot. Today this work is carried out by electrical switches that are set locally . The only remaining signal box is the mechanical signal box 5, which is used solely for shunting traffic: It distributes the trains, locomotives and wagons to be parked in their groups, the washing system and the locomotives in the direction of the depot.

Ruderal flora

As at any other train station, you can discover typical ruderal plants in the tracks of the Freiburg (Breisgau) Hauptbahnhof train station . In September 2002 Dietmar Brandes examined the flora there more closely. As was to be expected, you can compare the flora there with that of other train stations by and large. However, there were some special features:

For the location of Freiburg partly abundant deposits of are Schmalblättrigem diplotaxis ( Diplotaxis tenuifolia ), Schmalblättrigem hollow tooth ( Galeopsis angustifolia ), field-snapdragon ( Misopates orontium ) and Fox Red foxtail ( Setaria pumila ) common. However, the rarer mustard ( Coincya monensis ) and the imported Chinese bluebell tree ( Paulownia tomentosa ) also occur.

Train connections

Long-distance passenger transport

In long-distance traffic, there are regular ICE connections to the north from Freiburg main station in the direction of Berlin , Hamburg and Cologne from track 1. On the route to Hamburg, individual trains are connected to Kiel ; on the route to Cologne, wing trains are used that are separated in Cologne and One part of the train goes to Dortmund and once a day to Amsterdam . In addition, two pairs of EuroCity trains on the Zurich / Interlaken Ost - Mainz - Cologne - Hamburg route stop in Freiburg. To the south, most trains end in Basel SBB , some of them continue to Zurich HB , Interlaken Ost or Chur . Long-distance trains to the north usually stop on platform 1, and to the south on platform 3.

Since 26 August 2013, a wrong TGV the SNCF for Paris. In the first five years this pair of trains drove via Mulhouse and Dijon on the LGV Rhin-Rhône and LGV Sud-Est and reached the Gare de Lyon after about 3 hours and 40 minutes. Since December 9, 2018, a route via Strasbourg and the LGV Est européenne to the Gare de l'Est has been chosen instead. This connection is about 30 minutes faster.

With the timetable change in December 2017, a EuroCity Express was also introduced on the Frankfurt - Milano Centrale route with a stop in Freiburg.

In the night train to the main train station is the since December 2016 ÖBB Nightjet approached. On the way from Zurich HB to Hamburg-Altona , this serves among others the train stations Basel SBB , Frankfurt (Main) Süd and Berlin Hbf . Before that, there were connections with the now discontinued night trains of the City Night Line of Deutsche Bahn, for example to Amsterdam and Prague .

On weekends, Flixmobility offers a night train connection under the name FLX NIGHT from Hamburg via Hanover and Freiburg to Lörrach.

| Train type | route | Clock frequency | track |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICE | Interlaken Ost - Basel SBB - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Karlsruhe Hbf - Mannheim Hbf - Frankfurt Hbf - Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe - Braunschweig - Berlin Ostbahnhof | Every 2 hours | 1/3 |

| ICE | Basel SBB - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Karlsruhe Hbf - Mannheim Hbf - Frankfurt Airport - Siegburg / Bonn - Cologne - Wuppertal - Dortmund Hbf | Every 2 hours | 1/3 |

| ICE | Zurich HB - Basel - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Karlsruhe Hbf - Mannheim Hbf - Frankfurt Hbf - Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe - Hannover Hbf - Hamburg-Altona (- Kiel) | Every 2 hours | 1/3 |

| ICE | Basel - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Karlsruhe Hbf - Mannheim Hbf - Siegburg / Bonn - Düsseldorf Hbf - Duisburg Hbf - Emmerich - Amsterdam Centraal | individual trains | 1/3 |

| TGV | Freiburg (Breisgau) - Emmendingen - Lahr - Offenburg - Strasburg - Paris | a pair of trains | 4/5 |

| IC | Basel Bad Bf - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Karlsruhe - Stuttgart - Munich | a pair of trains | 1/2 |

| ECE | Frankfurt - Mannheim - Karlsruhe - Baden-Baden - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Basel - Lucerne - Bellinzona - Lugano - Chiasso - Monza - Milano Centrale | a pair of trains | 1/4 |

| EC | Zurich HB - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Karlsruhe - Mainz - Essen - Bremen - Hamburg-Altona | two pairs of trains | 1/3 |

| NJ | Zurich HB - Basel - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Karlsruhe - Frankfurt (Main) Süd - Halle (Saale) - Berlin - Hamburg | Every day | 1/3 |

| FlixNight | Hamburg-Altona - Hamburg Hbf - Hamburg-Harburg - Hanover - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Lörrach | daily (seasonal in summer) | 1/3 |

Public transport

There are numerous star-shaped connections in all directions for local transport to the clock node ( every full and half hour) . On the Rheintalbahn, the Regional Express trains to Offenburg and Basel are partially connected, so that the Offenburg – Basel / Basel – Offenburg route is offered without changing trains. With the Breisgau S-Bahn 2020 there are connections in the direction of Breisach , Endingen (via Gottenheim ), Titisee-Neustadt , Seebrugg and Villingen , as well as to the Elztal and a few trains to the Münstertal .

Since December 9th 2012 there has been a daily direct connection to Mulhouse Ville again . French X73900 are used .

| Train type | route | Clock frequency | track |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRISHMAN | Freiburg (Breisgau) - Müllheim (Baden) - Neuchâtel (Baden) - Bantzenheim - Mulhouse Ville | a pair of trains | 4th |

| RE | (Karlsruhe -) Offenburg - Lahr (Black Forest) - Emmendingen - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Bad Krozingen - Müllheim (Baden) - Basel Bad Bf (- Basel SBB ) | 60-minute intervals | 2/4 |

| RB | Freiburg (Breisgau) - Emmendingen - Lahr (Schwarzw) - Offenburg (- Karlsruhe) | 60-minute intervals | 1/3/4/5 |

| RB | (Offenburg -) Freiburg (Breisgau) - Eringen - Schallstadt - Bad Krozingen - Heitersheim - Müllheim (Baden) - Neuchâtel (Baden) / Basel Bad Bf (- Basel SBB) | 60-minute intervals | 1/3/4/5 |

| S 1 | (Breisach - Gottenheim - Freiburg (Breisgau)) - Kirchzarten - Titisee - Seebrugg | (30-) 60-minute intervals | 6/7 |

| S 10 | Freiburg (Breisgau) - Kirchzarten - Titisee - Neustadt - Donaueschingen - Villingen | 60-minute intervals | 8th |

| S 11 | [Breisach - Gottenheim - Freiburg (Breisgau) - Kirchzarten] - Titisee - Neustadt | [individual trains in the off-peak times]

60-minute intervals |

6/7 |

| S 12 | [ Freiburg (Breisgau) ] - Gottenheim - Eichstetten - Riegel Ort - Endingen | [individual trains in the off-peak times]

30-minute intervals |

6/7 |

| S 13 | Freiburg (Breisgau) - Freiburg-Wiehre - Freiburg-Littenweiler - Kirchzarten | 60-minute intervals (during peak hours) | 8th |

| S 2 | Freiburg (Breisgau) - Denzlingen - Waldkirch - Bleibach (- Elzach ) | 30 (-60) minute intervals | 1/5 |

| S 3 | [Freiburg (Breisgau) - Eringen - Schallstadt -] Bad Krozingen - Staufen (- Münstertal ) | [individual trains]

30 (-60) minute intervals |

1/4 |

Transport links

As early as the 1950s , Freiburg Central Station was an important junction between long-distance, regional and local transport. It made it possible to switch directly to post buses and trams , which probably made Freiburg unique at the time. The central bus station (ZOB) is still located at the southern end of platform 1 . It is mainly served by the SBG , which is also based there and operates a customer center. The bus service operated by the Freiburg Travel Service runs up to twelve times a day from here to the EuroAirport Basel Mulhouse Freiburg ; There are connections to Europa-Park in Rust, in the Black Forest to Elzach and St. Peter as well as to Colmar and Mulhouse through the SBG and some connections through lines of private bus companies of the Regio-Verkehrsverbund Freiburg (RVF) . A total of 15 bus routes serve the ZOB.

As a transition for pedestrians and the Freiburg im Breisgau tram, the Stühlinger Bridge runs across the tracks , on which the Hauptbahnhof (Stadtbahn) stop of the Freiburger Verkehrs AG (VAG) is located. This stop is served simultaneously by four of the five Freiburg tram lines - which the operator calls " Stadtbahn ". Under the bridge, at the bus station on Bismarckallee or in front of the concert hall, there is a bus stop operated by the Freiburger Verkehrs-AG. In the night traffic partially drive other lines.

| line | Means of transport | route | Tact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | tram | Littenweiler - Bertoldsbrunnen - Central Station - Paduaallee - Landwasser | 6-minute intervals |

| 2 | tram | Günterstal - Bertoldsbrunnen - Central Station - Main Cemetery - Hornusstraße | 10-minute intervals |

| 3 | tram | Vauban - Johanneskirche - Bertoldsbrunnen - Hauptbahnhof - Haid | 7.5-minute intervals (6 minutes in peak hours) |

| 4th | tram | Zähringen - Europaplatz - Bertoldsbrunnen - Central Station - Exhibition Center | 7.5-minute intervals (6 minutes in peak hours) |

| 11 | City bus | Main station - Pressehaus - Vauban - St. Georgen - Haid | 15-minute intervals |

| 14th | City bus | Central station - Eschholzstraße - Haslach - Haid | 15/30-minute intervals |

| 23 | City bus | Central station - Rennweg - North industrial area - Gundelfinger Strasse | Isolated buses in the morning and in the evening |

There are a total of 30 taxi stands in the area of the main train station, which are divided between the bus station, Bismarckallee and Konrad-Adenauer-Platz in front of the concert hall.

From the Bismarckallee, the underground car park with 100 spaces can be accessed via one of the four ramps. There it is permitted to park for 20 minutes free of charge under the name Kiss and Ride . Together with the underground garages Konzerthaus (366 spaces), Volksbank (103 spaces), Bismarckallee (220 spaces) and Uni- FMF / VF (95 spaces), it forms the station parking zone of the Freiburg parking guidance system .

The bike station has been located southwest of the train station since September 1999 with a bicycle parking garage, roof terrace, offers for mobility and culture as well as a restaurant. There are a further 1000 bicycle parking spaces in the open air in Bismarckallee and Wentzingerstraße.

literature

- Hans-Joachim Clewing: Friedrich Eisenlohr and the buildings of the Baden State Railway . Dissertation University of Karlsruhe 1968.

- City of Freiburg: The new central station Freiburg , press and information office / city planning office, Freiburg July 2001.

- Gerhard Greß: Freiburg transport hub and its surroundings in the fifties and sixties . EK-Verlag, Freiburg 1997, ISBN 3-88255-263-8 .

- Comradeship work of locomotive personnel at the Freiburg depot: 140 years of the railway in Freiburg - Rheintalbahn , Freiburg im Breisgau 1985.

- Albert Kuntzemüller : How Freiburg got its first railroad. In: Freiburger Almanach 5 (1954), pp. 121-136.

- Albert Kuntzemüller: The Baden Railways 1840-1940 , self-published by the Geographical Institute of the Universities of Freiburg i. Br. And Heidelberg, Freiburg im Breisgau 1940.

- Hans-Wolfgang Scharf, Burkhard Wollny: The Höllentalbahn. From Freiburg to the Black Forest. Eisenbahn-Kurier-Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1987, ISBN 3-88255-780-X .

Web links

- Location, track systems and some signals and speeds on the OpenRailwayMap

- Private homepage about the main station Freiburg (Breisgau)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Query of course book route 703 at Deutsche Bahn.

- ↑ Query of the course book route 727 at Deutsche Bahn.

- ↑ Querying the course book route 729 at Deutsche Bahn.

- ↑ Small request from the Abg. Boris Palmer and the answer from the Ministry for the Environment and Transport: State of the most important train stations in Baden-Württemberg . ( Memento from July 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ; PDF; 107 kB) State Parliament of Baden-Württemberg, printed matter 13/4069, from March 18, 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ Stiftung Warentest: Punctuality of the Deutsche Bahn 2011 - Hamburg brings up the rear . test.de, January 10, 2012; Retrieved February 4, 2013

- ↑ a b Law on the construction of a railway from Mannheim to the Swiss border near Basel . ( Wikisource )

- ^ Edwin Kech: The foundation of the Grand Ducal Baden State Railways . G. Braunsche Hofbuchdruckerei, Karlsruhe 1904, p. 83 ff.

- ^ A b c d e f g h i Albert Kuntzemüller: How Freiburg got its first railway in: Freiburger Alamanch 5, 1954, pp. 121-136.

- ↑ Clewing, p. 75; Figure: Compilation of the absolute heights of all main stations and intermediate stations in 1853 .

- ↑ Greß, p. 8.

- ^ Negotiations of the assembly of estates of the Grand Duchy of Baden / Extraordinary State Parliament / Minutes of the Second Chamber 1838 , p. 261.

- ↑ a b c Baden Higher Directorate of Hydraulic Engineering and Road Construction: Detailed documentation on railway construction in the Grand Duchy of Baden: according to the status on January 1, 1853 , Braun, Karlsruhe 1853.

- ^ Edwin Kech: The founding of the Grand Ducal Baden State Railways , G. Braunsche Hofbuchdruckerei, Karlsruhe 1904, p. 105 f.

- ↑ a b Kuntzemüller, p. 24.

- ↑ Article. In: Freiburger Zeitung , July 23, 1845; Retrieved December 22, 2010

- ^ A b Albert Mühl: The Grand Ducal Baden State Railways , Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-440-04933-7 , p. 26 f.

- ↑ Freiburg newspaper of July 31, 1845 .

- ↑ Greß, p. 7.

- ↑ a b c The station was opened with one track In: Badische Zeitung , April 25, 1970.

- ^ Title page of the Freiburger Zeitung of September 21, 1845.

- ^ Ordinance sheet of the Direction of the Grand Ducal Post and Railways 1845, pp. 98 - 99 .

- ↑ Michael Saffle: Liszt in Germany 1840-1845. A Study In Sources, Documents, And The History Of Reception , Stuyvesant, New York 1994, p. 278: Since departure and arrival are on the same day, only the train is possible for this journey.

- ↑ a b The city and rural districts in Baden-Württemberg: Freiburg im Breisgau , Rombach, Freiburg im Breisgau 1965, Volume I / 2, pp. 708–715.

- ^ Friedrich Eisenlohr : Collection of high-rise buildings of the Grand Ducal Baden Railway, containing train stations, stations and station keepers' houses, views, sections and floor plans. Vol. 1-3, Karlsruhe.

- ^ Freiburg: Vogelschauplan von Osten , Joseph Wilhelm Lerch, 1852. Basement of the Freiburg City Museum

- ^ A b Hans Schadek: Freiburg then-yesterday-today . Steinkopf Verlag, Stuttgart 2004, p. 121 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e f Eberhard Hübsch: The state railways . in: Freiburg im Breisgau. The city and its buildings , HM Poppen & Sohn, Freiburg 1898.

- ↑ Freiburg newspaper of August 21, 1901 .

- ↑ About the relocation of the open-air station in: Freiburger Zeitung of October 4, 1896 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ a b c d The renovation of the Freiburg passenger station. In: Second evening paper of the Freiburger Zeitung of July 20, 1927 .

- ↑ Kuntzemüller, p. 120.

- ↑ Reconstruction of the Freiburg main station. In: New Badische Landeszeitung from December 19, 1924.

- ^ Freiburger Bilderbogen , in: Freiburger Zeitung of June 8, 1930 .

- ^ Section statistics in several Freiburg address books ( available online).

- ^ Letter from the city administration of Freiburg dated October 12, 1938 to the Reichsbahndirektion Karlsruhe as well as extensive illustrations, city archive Freiburg C4 / XV 30/5.

- ↑ More beautiful and functional. In: Der Alemanne from September 16, 1943.

- ↑ a b c Kameradschaftswerk Lokpersonal, p. 65.

- ↑ Platform No. 3 . in: Freiburger Zeitung of May 12, 1929.

- ↑ Kuntzemüller, p. 142.

- ↑ Kuntzemüller, p. 190.

- ↑ Oliver Strüber: Temporausch und Dieselqualm in: 1,2,3-Leiter-Magazin , HK Edition Luxemburg, 1/2007.

- ↑ Kuntzemüller, pp. 144 ff.

- ^ Albert Kuntzemüller : The Baden Railways , G. Braun, Karlsruhe 1953, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Plaque at the monument on the Wiwilí Bridge.

- ^ Roger Chickering: The Great War and Urban Life in Germany: Freiburg, 1914-1918. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-85256-2 , p. 99.

- ↑ Scharf / Wollny, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Albert Kuntzemüller: The Baden Railways , G. Braun, Karlsruhe 1953, p. 176.

- ↑ a b Albert Kuntzemüller: The Baden Railways , G. Braun, Karlsruhe 1953, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Albert Kuntzemüller: The Baden Railways , G. Braun, Karlsruhe 1953, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Scharf / Wollny, p. 131.

- ↑ Scharf / Wollny, pp. 144–146.

- ↑ Kameradschaftswerk Lokpersonal, p. 48.

- ↑ Greß, p. 37.

- ↑ a b c d Albert Kuntzemüller: The old and the new main train station building in Freiburg i. Br . in: Schweizerische Bauzeitung 68 of June 3, 1950.

- ↑ a b c Scharf / Wollny, p. 133.

- ↑ Kameradschaftswerk Lokpersonal, p. 71 f.

- ^ City of Freiburg, p. 60.

- ^ City of Freiburg, p. 59 ff.

- ↑ Diesel express railcar network of the Deutsche Bundesbahn in the summer of 1958.

- ^ Erich Preuss (Ed.): The large archive of the German train stations: Freiburg (Brsg) Hbf . GeraNova Zeitschriften-Verlag, Munich. Loose-leaf edition. ISSN 0949-2127 .

- ^ Marcus Grahnert: ICE deployments from 1991 . grahnert.de; Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ↑ Simone Höhl: The escalator at the main train station will remain out of order until February. Badische Zeitung, October 24, 2018, accessed on October 24, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d City of Freiburg, p. 53.

- ↑ a b c d Wulf Daseking: Chances at the train station , In: Stadt Freiburg, p. 12 f.

- ↑ a b Frank Straube: Who took the money in hand? , In: City of Freiburg, p. 22 f.

- ↑ a b Communal council printed paper G-93/122 - draft resolution for the development plan 'train station' (new) ( memento from May 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) for the ninth meeting of the communal council on July 22, 1993 , created May 28, 1993; Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ↑ BB: Pillars become museum pieces. The days of historic platform roofing are numbered. In: Badische Zeitung , May 31, 2001, p. 27.

- ↑ Anja Bochtler: Pillars on the move . Badische Zeitung of July 2, 2010.

- ^ A b Bilfinger + Berger: The project in: Stadt Freiburg, p. 24 f.

- ↑ Schweizer Baublatt 108, 1997, p. 2.

- ↑ Klaus Boch: First address Hauptbahnhof , In: Stadt Freiburg, p. 48.

- ↑ Municipal printed matter BA-00/026 - draft resolution for a building application from Bilfinger and Berger Projektentwicklungs-GmbH for the subsequent granting of a building permit for the construction of a connecting bridge between components 2 and 3 on the 5th floor of the main train station (PDF) for the 10th meeting of the building and Reallocation Committee July 19, 2000 - created July 12, 2000; accessed on March 27, 2017.

- ^ Badische Zeitung of March 8 + 11, May 10 + 11, July 20 and October 9, 2000.

- ↑ VarTec closes call center. In: juve.de. June 29, 2005. Retrieved March 29, 2017 .

- ↑ a b municipal council printed matter BA-17/011 - information template connecting bridge between components 2 and 3 on the 5th floor of the main station (PDF) for the 3rd meeting of the building and reallocation committee February 22, 2017 - created February 15, 2017; accessed on March 27, 2017.

- ^ Sina Gesell: Freiburg: City wants to legalize illegal footbridge in the wind window. Badische Zeitung, February 22, 2017, accessed on February 22, 2017 . ; jlb: Freiburg: The bridge in the wind window can stay. Badische Zeitung, February 24, 2017, accessed on February 24, 2017 .

- ↑ Jelka Louisa Beule: Thick air in the Stühlinger. Badische Zeitung, March 3, 2020, accessed on March 3, 2020 .

- ^ Freiburg: "Call center do not close". In: suedkurier.de. April 8, 2003. Retrieved March 29, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d Interview with station manager Mr. Sutter from October 2009.

- ↑ named ICE trains of the 403 series. (No longer available online.) Eisenbahn-kurier.de, archived from the original on April 24, 2010 ; Retrieved September 14, 2012 .

- ↑ Bahn closes seven call centers. In: tagesspiegel.de. December 18, 2003, accessed March 29, 2017 .

- ↑ Milestones in the history of DB Dialog. (No longer available online.) In: dbdialog.de. September 21, 2016, archived from the original on March 30, 2017 ; accessed on March 29, 2017 .

- ^ Article in the archive folder "Hauptbahnhof" of the Badische Zeitung.

- ^ Erik Roth: Offenburg – Freiburg. The buildings of the Baden State Railway and the four-track expansion of the Rhine Valley Railway. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Wuerttemberg - newsletter of the state preservation of monuments , issue 3/2002 ( issue 3/2002 digitized ).

- ^ Peter Pretsch: Friedrich Eisenlohr - architect of the Baden railway . ( Memento of August 5, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) In: Blick in die Geschichte , No. 67, June 24, 2005; Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ A b c d Manfred Berger: Historic train station buildings III. Bavaria, Baden, Württemberg, Palatinate, Nassau, Hesse Publishing House for Transport, Berlin 1988, p. 114 ff.

- ^ A b Rainer Humbach: Page no longer available , search in web archives: The old Freiburg main train station lives on , In: Badische Zeitung , August 13, 2002.

- ↑ Kuntzemüller, p. 116 ff.

- ↑ Greß, p. 6.

- ↑ a b c Kameradschaftswerk Lokpersonal, p. 33 ff.

- ^ Albert Kuntzemüller: The Baden Railways , G. Braun, Karlsruhe 1953, p. 174.

- ^ New Station Building at Freiburg in: The Railway Gazette of July 14, 1950: "Although the building [...] is an outspoken utility building, it is not only fully adequate for the purpose, but also satisfactory architecturally."

- ↑ List of references from the architects Harter + Kanzler; Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ↑ Freiburg Statistics Emporis. Retrieved October 26, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c Bilfinger + Berger: Description of the property In: Stadt Freiburg, p. 29 f.

- ↑ Gina Kutkat: The Neko opens in autumn in the former Kagan. Badische Zeitung, August 11, 2018, accessed on August 12, 2018 .

- ^ Ludwig Harter: The architects . City of Freiburg, p. 26 f.

- ↑ Photovoltaic Architecture Prize Baden-Württemberg 2001 project documentation . (PDF; 1.4 MB) Landesgewerbeamt Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart 2003, p. 38 ff .; Retrieved September 14, 2012

- ↑ Jürgen and Ivo Wißler: Bahnbetriebswerk Freiburg ( Memento from November 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) badische-hoellentalbahn.de; Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ↑ Track plan of Freiburg main station .

- ↑ Joachim Röderer: Postbahnhof is being demolished - only 28 years after its construction . Badische Zeitung , February 3, 2012.

- ↑ a b "Traffic lights" instead of wings and temporary unity , Badische Zeitung, September (?) 1998.

- ^ The station renovation In: Freiburger Zeitung of September 30, 1931, No. 266.

- ↑ a b On the command bridge of our main train station , newspaper article from December 1937, Freiburg City Archives C4 / XV 30/5.

- ↑ Dietmar Brandes: Flora of the railway systems in Freiburg i. Br. Excursion notes . 2003 ( online (PDF)).

- ^ Joachim Röderer: Freiburg: Rail transport: Premiere at the main station: This is how the TGV to Paris started . Badische Zeitung , August 26, 2013.

- ↑ a b c Departure and arrival times on the official station website.

- ↑ 102

- ↑ Badisch-Alsatian bond in Badische Zeitung , December 10, 2012.

- ↑ Greß, p. 31.

- ↑ Timetable of the airport bus , October 25, 2009 up to and including March 27, 2010; Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ↑ SBG route network ( Memento of March 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive ; PDF) accessed on January 7, 2010.

- ↑ VAG SaferTraffic_Netzplan. Retrieved March 24, 2019 .

- ↑ VAG network plan. (PDF) Retrieved March 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Uwe Schade, Hans-Georg Herffs: Where should all the pedestrians, cyclists and cars go? City of Freiburg, p. 41.

- ↑ Parking guidance system - station garage. (No longer available online.) City of Freiburg im Breisgau, formerly in the original ; Retrieved January 7, 2010 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ Parking guidance system. (No longer available online.) City of Freiburg im Breisgau, archived from the original on July 24, 2010 ; Retrieved January 7, 2010 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Freiburg: Promising top offer. In: badische-zeitung.de. Retrieved July 24, 2015 .

- ↑ Freiburg bike station. Retrieved April 10, 2015 .

- ↑ Uwe Schade, Hans-Georg Herffs: Where should all the pedestrians, cyclists and cars go? , in: City of Freiburg, p. 39.