Mass in B minor

The B minor mass by Johann Sebastian Bach , BWV 232, is one of the most important sacred compositions. It is Bach's last major vocal work and his only composition based on the full ordinarium of the Latin text of the fair . In terms of type, it is a Missa solemnis , which consists of 18 choral movements and 9 arias . In 1733, Bach first composed a Missa from Kyrie and Gloria. Towards the end of his life he put the remaining movements together from arrangements of earlier composed movements, mainly from his cantatas, and new compositions ( parody method ). The manuscript from 1748/1749 is a UNESCO World Document Heritage .

history

occasion

After the death of Elector Friedrich August I of Saxony on February 1, 1733, a state mourning was ordered for the period from February 15 to July 2, 1733, during which no music was allowed to be performed. During this time Bach prepared the score and parts for the first version, a Missa with the parts Kyrie and Gloria . He dedicated the performance parts to his successor, Elector Friedrich August II., Who became King of Poland August III. was called.

It is not known why Bach expanded this short mass into a complete Missa tota . Bach himself did not write anything about his motives, just as otherwise personal information from him is rare. Since he began to create other cyclical works with model character from the mid-1730s ( Goldberg Variations , Christmas Oratorio , The Art of Fugue ), it is assumed that the expansion could be related to sifting through and collecting his important works to leave a musical legacy for posterity.

Although no vocal material has yet been found that indicates a specific occasion, various Bach researchers accept a performance of the mass during Bach's lifetime. According to a more recent hypothesis by Michael Maul , it could have been intended for a performance in St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna in 1749 . Count Johann Adam von Questenberg (1678–1752), active in Vienna as a member of the so-called Musical Congregation , made contact with Bach through a noble student from Moravia. The student visited Bach in the spring of 1749 on behalf of Questenberg and may have asked for a composition for the St. Cecilia celebration of the Vienna Brotherhood on November 22, 1749.

role models

With the Reformation , the tradition of Latin church music in the Protestant churches did not end, but it experienced considerable restrictions. From the time before Leipzig, only one single Latin composition can be traced by Bach, the five-part choral setting Kyrie eleison, Christe du Lamm Gottes , BWV 233a. However, there are various copies of Latin mass compositions by Bach by other composers, including four to six -part a cappella masses by Palestrina and Francesco Gasparini and orchestral concert masses ("Missa concertata") by Marco Giuseppe Peranda and Johann Baal, and the Missa sapientiae by Antonio Lotti . On major ecclesiastical holidays, figural performances of the Latin Kyrie and Gloria and the Sanctus (without Osanna and Benedictus) as polyphonic choral music were common in the main churches in Leipzig . In addition to the Magnificat (BWV 243), which in its D major version from 1733 has a similar scoring to the B minor Mass, there are also some settings of the Sanctus (BWV 237 and 238) and the Lutheran ones in Latin figural music by Bach Masses (BWV 233–236) that are smaller and in which only Kyrie and Gloria are set to music. For performances, Bach used works by other composers.

Christoph Wolff suspected that Bach used a Missa brevis (Kyrie and Gloria in G minor) by Johann Hugo von Wilderer as a model for the outer form of numbers 1, 2 and 3 . Before 1731, Bach had probably copied Wilderer's Mass for four-part choir and strings in Dresden and performed it in Leipzig. In addition to individual motivic similarities, there are correspondences in the form of the Kyrie: An introductory adagio with a triple Kyrie call is followed by a fugue, the head motif of which is characterized by repercussions . The Christe is in each case as a solo movement (in the case of Wilderer a trio with duet passages) in the major parallel and the final Kyrie motet in the style of antico . Konrad Küster has objected to the two works being dependent on one another due to the great differences. The large-scale system at Bach and the completely different implementation in detail speak against a direct relationship.

Work history

The composition of this mass spanned decades: The Sanctus (BWV 232 III ) was composed as early as 1724 for Christmas Day. In 1733 the Missa brevis was composed of Kyrie and Gloria (in contrast to the Missa longa or Missa tota , the five-part, complete mass). This first version could be used in both Lutheran and Catholic worship services, but in the original text it deviated from the prescribed Catholic Mass text in two places. Bach submitted the 21 parts of this version to the Dresden court with the dedication letter of July 27, 1733, combined with the request to be awarded the title of “court composer” (“Praedicat von Dero Hoff-Capelle”). Only after repeated memories, further dedications and numerous concerts was he awarded the title of “Electoral Saxon and Royal Polish Court Composer” in November 1736. The Saxon royal court has been Catholic since the personal union with the Kingdom of Poland. It is not known whether the set of parts was ever performed. There is no performance material in either Dresden or Leipzig.

According to Christoph Wolff, the five-part, richly orchestrated structure by Kyrie and Gloria with its carefully worked out individual movements indicates that Bach was planning a complete mass. Various references prove Bach's turn to mass compositions in the 1730s and 1740s and illuminate the prehistory of the B minor Mass. In the 1730s, for example, Bach created the Lutheran Masses and the Piano Exercise III (the so-called Organ Mass , 1739). In 1742 he compiled individual movements from the Gloria for the university music Gloria in excelsis Deo, BWV 191 , and re-performed the Sanctus from 1724 between 1743 and 1748 . In addition, Bach arranged masses by other composers in the late 1730s and early 1740s and used them for the Leipzig services. An early version of the Credo in unum Deum in G- Mixolydian is to be set around 1740. A choir intonation of a Credo in unum Deum to a Missa brevis by Giovanni Battista Bassani (BWV 1081), a composition study, leads to the Credo of the B minor Mass.

In 1748/49 Bach added Credo , Sanctus and Agnus Dei to the mass with a few new compositions, but mostly by parodying existing movements from his cantatas . The Credo was initially laid out in eight movements, but the new composition of Et incarnatus est no.16 gave it its nine-movement, strictly symmetrical structure with the life of Jesus in the center (no.16 Incarnation, no.17 Crucifixion, no.18 Resurrection).

Autograph

Bach only sent the two parts of the Missa from 1733 as individual parts to August III. and kept the score he completed in the last years of his life. He paginated the 95 manuscript pages of Kyrie and Gloria and provided them with an envelope on which he wrote as the title “No. 1 Missa ”, which wrote the scoring details and his name. A second half-volume, which is bound together with the first, contains the remaining parts in three fascicles on 92 pages. The Credo (pages 96 to 152) via stream with wrote "No. 2 Symbolum Nicaenum “. According to No. 3 Sanctus formed the remaining sentences under the heading “No. 4 Osanna, Benedictus , Agnus Dei et Dona nobis pacem “the conclusion. Bach's division of Sanctus and Osanna must have had practical reasons, as the Sanctus could be copied directly from the original, but with extended instrumental accompaniment, while the remaining movements were newly composed or had to be reworked. At the beginning of the first, second and fourth fascicle, Bach wrote “J. J. “( Jesu Juva , Jesus, help!), At the end of the Gloria“ Fine DGl ”(end, God the honor) and at the very end“ DSGl ”( Deo soli Gloria , God alone the honor).

Comparisons of manuscripts suggest that Bach completed the mass in December 1749. As early as 1956, Friedrich Smend pointed out that Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was involved in the revision of the final form. An X-ray fluorescence analysis provided further details , with the help of which the various revision phases of the Bach son, which took place over a longer period of time and with the use of different types of inks, could be more clearly distinguished. In places the manuscript is badly damaged by ink damage, multiple foreign entries, erased areas and holes. Recently, a (small) participation by Bach's son Johann Christoph Friedrich has also been considered possible, who could have added tempo indications, explanatory tablature letters and text syllables in the score. Carl Philipp inherited the autograph and in particular edited the Credo for a performance in 1786. After his death in 1788, after several attempts to sell the score, it was acquired in 1805 by the well-known music writer, publisher and composer Hans Georg Nägeli from Zurich, who was first printed in 1818 announced. In a roundabout way, the autograph score came to the Leipzig Bach Society in 1856 , which one year later sold it to the Berlin State Library (manuscript P 180 ), which currently holds 80 percent of Bach's musical manuscripts.

Surname

Bach did not give the completed work an overall title, but numbered and overwritten the four fascicles . In the list of the estate of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1790), the B minor mass was referred to as the “great Catholic mass”. It is unclear whether this name reflects the language used by the Bach family or whether it was chosen simply out of ignorance. Obviously, the mass should be distinguished from the Lutheran masses by the attribute “large”, while “catholic” refers to the setting of the entire text of the fair and represents an ecumenical dimension.

The name in use today in B minor mass (also: mass in b minor ) goes back to Carl Friedrich Zelter , who from 1811 rehearsed parts of the mass with his singing academy and who paved the way for the Bach renaissance . The key designation refers to the beginning of the work; In fact, only a few other movements are in B minor, but most of them in other keys ( mainly in the parallel key of D major because of the natural trumpets ). The three movements of Kyrie are in B minor, D major and F sharp minor, the root notes of which result in an B minor chord. This anticipates the harmoniously broad overall conception of the mass with D major as the central key. The name Hohe Messe , which was coined by the Romantic era, was created by the publisher Hermann Nägeli, corresponding to Beethoven's Missa solemnis , who published the first printed complete edition in 1845: “The Hohe Messe in B minor by Joh. Seb. Bach engraved from the autograph ”.

Parodies

In Bach research, there is a consensus that most of the movements were not newly composed, but put together from earlier works by Bach and partly revised for the B minor Mass. However, the templates are only known for a few sentences. In the original score, the copies stand out from the new compositions by a fair copy with only occasional error corrections. Obviously in this case Bach wrote the score vertically through all parts and did not write down the basic parts first as usual. Due to transposition errors , the Kyrie in B minor (BWV 232 I , No. 1) can be inferred from an original in C minor.

On September 5, 1733, Bach composed the secular cantata Drama per musica BWV 213 "Let us take care, let us watch" (Hercules at the Crossroads) for the birthday of the Prince Elector of Saxony Friedrich Christian . This cantata later served as a parody model for parts of the Christmas Oratorio (BWV 248, 1734/35). The autograph score of BWV 213 contains a four-bar sketch for no.11 as a reworking of a lost model that Bach did not use for BWV 213, but for the duet no.15 Et in unum Dominum from the Credo .

The text structure of BWV 193a No. 5 suggests that this duet served as a template for the Domine Deus (BWV 232 I , No. 8). The secular cantata was a tribute music for the name day of Elector Friedrich August I on August 3, 1727. Between 1743 and 1746 Bach worked three movements from the Gloria , namely Gloria in excelsis (No. 4), Domine Deus (No. 8) and Cum Sancto Spirito (No. 12) to the Latin Christmas music Gloria in excelsis Deo, BWV 191 um.

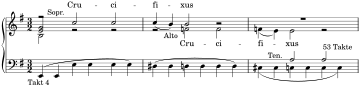

The Crucifixus goes back to a choral movement of the cantata Weinen, Klagen, Sorge, Zagen from 1714, which Bach had composed 35 years earlier, making it the oldest model for the entire mass. As with the other parodies, Bach made numerous changes. The movement was transposed from F minor to E minor, re-orchestrated and complementary rhythmized between the accompanying flutes and strings. Instead of the sustained half notes in the ostinato bass , the hammering quarter notes increase the expressiveness. Compared to the original, the melody of the vocal parts in bars 9 and 10 was sharpened by excessive seconds and declaimed again due to the shorter Latin text . Finally, the words “et sepultus est” (and buried) were given a newly composed ending in which the accompanying voices fell silent. Bach modulated in G major and thus led over to the next movement, Et resurrexit .

After the parody method was widely used in the Baroque period and was valued as a show of honor, it fell into disrepute in the 19th century as the Romantic aesthetic revered the original genius who created unique and incomparable works of art. Only in the last few decades was there a reassessment of the parodies, which play no small part in Bach's vocal late work, as it was not a matter of simply copying with a new text underlay, but of a fundamental revision with an "extremely astute and methodical approach in the editing process" , which led to a new musical emphasis, an improvement in quality and a careful fit into the overall work.

Performances and appreciation

The figured continuo part in concert pitch shows that the Missa from 1733 in its present form was not intended for use in Leipzig: In Leipzig, the church organs were tuned to the higher choir pitch, so that Bach always had a transposed organ part made for Leipzig performances . Bach knew the new organ by Gottfried Silbermann in Dresden's Church of St. Sophia from his visits in 1725 and 1731. On June 23, 1733 Bach's son was Wilhelm Friedemann appointed organist at the church.

The large complex exceeded the possibilities of the regular Lutheran and Catholic liturgy, and Bach himself probably never saw a complete performance of the work. Comparable with the only two-part Lutheran masses , a performance of the Missa on high church holidays in the main Leipzig services and at the Protestant court service in Dresden is conceivable and not excluded. According to Christoph Wolff, a cyclical performance is also conceivable that spanned several Sundays and public holidays, comparable to the Christmas Oratorio, which was divided into six services.

The myth of the B minor Mass, which began years before the spectacular revival of the St. Matthew Passion in Berlin in 1829 under Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy , was prepared by two works on music theory from the 18th century. As early as 1755, the Bach student Christoph Nichelmann praised the "emphatic effect" of the work and printed the first four bars of Kyrie as an example. According to Johann Philipp Kirnberger , who obtained a copy of the autograph in 1769, the Crucifixus is “full of sensation, imitations, canons, contrapuncts, and beautiful modulation” (1777). Johann Friedrich Hering made a copy in Berlin in 1765, further copies were made via Charles Burney to London and Gottfried van Swieten to Vienna and to Joseph Haydn . Obviously Beethoven also tried to get a copy.

Carl Friedrich Zelter , who rehearsed various parts with his Sing-Akademie in Berlin in 1811 and the entire mass in 1813, praised it as "the greatest work of art the world has ever seen" (1811). Hans Georg Nägeli's invitation to subscribe to the first edition in 1818 was titled Announcement of the Greatest Musical Artwork of All Times and Nations . The first public performance in two parts did not take place until February 20, 1834 (part 1) and February 12, 1835 (part 2) under Zelter's successor Carl Friedrich Rungenhagen . In Vienna and Frankfurt am Main, some parts of the fair were performed around 1830. In the memoirs of Louis Köhler there is a reference to a performance of the mass by the Braunschweiger Sing-Akademie under its director Friedrich Konrad Griepenkerl, perhaps in a more private setting. The performance, the exact time of which is unknown, can be scheduled between 1829 and 1836.

The first complete public performance, organized by the local Cecilia Society , took place in Frankfurt in 1856 . The basis was the edition published in the same year as part of the complete edition by the Leipzig Bach Society. The Riedelsche glee club led the complete work in 1859 in Leipzig's St. Thomas Church in German translation.

Little by little, the mass established itself in the concert program of the great oratorio choirs. Until the Second World War it was performed ten times at the German Bach Festival of the New Bach Society and was performed 47 times by the Berlin Sing-Akademie. At the oldest Bach Festival in Bethlehem (Pennsylvania) , the work has been heard year after year since 1911 in an unbroken tradition. After the Second World War, the mass took first place among Bach's major works in terms of the frequency of performances, well before the St. Matthew Passion.

occupation

The last version of the B minor Mass requires five vocal soloists ( soprano I / II, alto , tenor , bass ), a four-, five-, six- and eight-part choir as well as a rich brass orchestra (three trumpets , timpani , a corno da caccia ), woodwinds (two transverse flutes , two oboes , two oboi d'amore , two bassoons ) and strings ( violin I / II, viola ) with basso continuo .

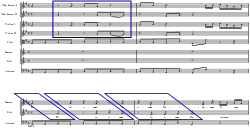

The orchestra is usually treated as obligatory and plays a major role in Bach's interpretation of the individual movements. In the two Kyries movements, Bach refrained from using the trumpets and performed the instruments colla parte in Kyrie No. 3 . In contrast, four out of five choral movements in the following Gloria are characterized by the festive instrumentation with trumpets and timpani. Only the Qui tollis peccata mundi (No. 9), in which the humiliation of the Son of God is thematized and a call to penance sounds, has a delicate instrumentation with two flutes and strings. The Credo is diversified. In Credo in unum Deum (No. 13) two violins above the soprano take over the two highest voices of the seven-part fugue. Bach took back the instrumentation in Et incarnatus est (No. 16) and in Crucifixus (No. 17) of the Credo . The five-part choral movement Confiteor No. 20 is only performed by the continuo group. In three choral movements (nos. 14, 18, 21) the tutti sounds again with the full cast. In the Sanctus (No. 22) Bach even prescribed three oboes. All arias have different instrumentation . Only the first and last aria (duet no.2 and solo aria no.26) are accompanied by two violins with continuo.

While large choirs appear in the 19th century and in modern performances that follow the romantic tradition, historical performance practice prefers a slim sound with few singers per voice. According to Joshua Rifkin , Bach's great vocal works were only performed with a choir consisting of solo voices , while Andrew Parrott used solo choir voices in fugue expositions and added a few other singers in the course of the composition.

Text template

When submitting the lyrics and the melodies Bach served consisting of the old church dating Ordinary Mass as amended by the New Leipzig hymnbook of Gottfried Vopelius (1682). The mass differs in two places from the traditional Roman Catholic Missal : In the Gloria, the word altissime is inserted after “Domine, fili unigenite, Jesu Christe” . In the Sanctus, instead of “gloria tua”, there is “gloria eius”, which corresponds to the Vulgate text of Isa 6,3 Vul . The differences are not a Lutheran peculiarity, but correspond to the medieval gradual , as it was created in the 13th century in the Thomasstift Leipzig. It is fitting that Bach followed the special cantus firmus version of the Thomas Gradual in the Confiteor (No. 20, bars 92–117) .

Work description

Missa

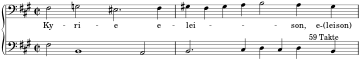

Traditionally, the Kyrie is made up of three parts: Between the framing Kyrie parts stands the Christe , which Bach clearly differentiated musically from the two Kyries movements. The opening Kyrie begins with a threefold invocation, followed by an orchestral ritual with a five-part choral fugue in B minor. According to Bach's contemporaries Johann Mattheson , B minor is “bizarre, uncomfortable and melancholy”. In both vocal throughs the theme is heard in both sopranos twice. While the instruments sound independently at first, they play along with the choir voices later. In Kyrie I, fugatics fuse with ritornello elements in a peculiar way. The Christe set to music Bach as a duet in a friendly in D major and chose the modern form of an opera duet. In Bach's two sopranos instrumentation there is no parallel, but it seemed to him particularly suitable for depicting the Trinitarian identity and yet the difference between God the Father and Christ the Son. The second Kyrie is a strict four-part choral fugue in the style of antico , in which the instruments support the vocal parts colla parte . His topic contains 14 grades that correspond to the numerological value of BACH (B = 2, A = 1, C = 3, H = 8).

The text of the Gloria is based on the hymn of praise of the angels of Bethlehem ( Lk 2.14 VUL ) and the early church Laudamus . All five vocal soloists are given arias, three solo arias for soprano II, alto and bass as well as a duet for soprano I and tenor (No. 8). In the opening chorus No. 4, trumpets and timpani sound for the first time, which in the radiant D major point to the majesty of the heavenly king, underlined by the fast three-bar, the broken major triads and the octave leaps in the bass. According to Mattheson, D major is “a bit sharp and obstinate by nature; for learning / funny / warlike / and encouraging things probably the most comfortable ”. Fugal inserts alternate several times with tutti sections. The affect changes suddenly at the transition to No. 5, where the peace on earth is set to music. In the quiet 4/4 time, minor keys, syncopation with paired eighth notes and long organ points predominate , which make earthly peace audible. In the course of the two fugatian developments, the trumpets only start again from bar 38. The movement, dominated by rich modulations, only finds its way back to the beginning D major in the meantime and in the last bars. The solo aria No. 6 Laudamus te for soprano II and solo violin is a modified da capo aria , which, with its long melisms , rich ornamentation and high registers, is conceived in an extremely virtuoso manner. The Gratias No. 7, a double fugue in the style of antico with colla-parte guidance of the instruments, could be taken directly from the BWV 29 template due to the text with the same meaning (We thank you) . In the last third the trumpets emerge through their obligatory voice treatment.

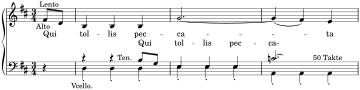

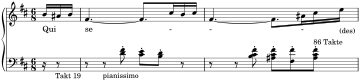

Similar to Christian No. 2, Bach used a duet in Domine Deus No. 8, which praises the first two persons of the deity. While the first line of text about the Almighty Father is set to music in one voice, the other voice sings the second line of text, which is about the only begotten Son, in canonical imitation: in the first 30 bars in the fourth or fifth , in the following 30 bars in the Octave and synchronized in thirds in the third part on the same text (Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris). The Qui tollis No. 9 (who you bear the sin of the world) conveys with the key of B minor, the descending minor triads, the lamento time in the slow threesome, the frequent shortened dominant seventh chords , the dissonances that rub against each other and the tones unrelated to the ladder (the figure of Pathopoeia ) a painful impression. In all three parts of Altarie No. 10 Qui sedes , Bach set the entire text of the Qui sedes to music .

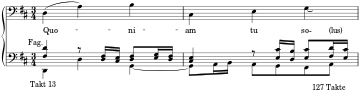

The instrumentation of the aria Quoniam (No. 11) in a modified da capo form, in which the bass is accompanied by three deep instrumental parts, two bassoons and the basso continuo , is unique to Bach . The corno da caccia (hunting horn) clearly stands out from this deep quartet and symbolizes the overwhelming majesty of the Son of God (you alone the Most High). The concluding five-part choir No. 12 Cum Sancto Spiritu is a crowning final doxology of the entire Gloria, which is enlivened by the multiple alternation of virtuoso fugatic elements and long, sustained homophonic chords (on the word patris ).

Creed

The credo is the middle of the five parts and the heart of the fair. It is built symmetrically in accordance with baroque designs. At the beginning and at the end there are two closely interconnected and in the center three choral movements (nos. 16-18) on the Incarnation, Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ (2 - 1 - 3 - 1 - 2), in between as no. 15 a duet and as No. 19 a solo aria. The opening chorus No. 13 is designed as a strict, seven-part fugue over a Gregorian melody made up of seven notes, the top two voices of which are taken over by the violins, while the continuo runs through a pitch of two octaves in quarter notes . The topic can be heard 17 times in three rounds, and at the end it is processed in a particularly artful way with an augmentation and multiple narrowing . In addition to the number symbolism with the seven as the number of abundance, the sentence reflects the order and power of the Creator, who has time and eternity. The patrem omnipotentem is a concertante fugue. At the end of the movement, Bach gave the number of bars 84 (12 × 7). The word Credo is heard 49 times (7 × 7) , 84 times the Patrem omnipotent .

In the second article of faith of Nicene, the person and work of Christ are developed. In the first version, the setting of the text from Et incarnatus est fell under the preceding aria Et in unum Dominum . Bach then composed his own choir piece, which he added to the manuscript on a new sheet. Aria No. 15 was finally underlaid with new text and the melody was adapted. Philipp Spitta already indicated the canonical voice leading in the words et in unum dominum with different phrasing ( staccato next to legato ) theologically on the close relationship between father and son, both of which are essentially but not identical: “The intent of this consistently carried out procedure can only be to distinguish the imitating voice from the other by a slightly different expression, even here to indicate a certain personal difference in the essential unity. "

In the Incarnatus (no. 16) the singing voices describe the condescendence of Christ by descending minor triads, seventh and ninth chords, which are fugatically performed in an irregular manner. It is probably Bach's last vocal composition at all (end of 1749 or in the first weeks of 1750). Meanwhile, the violins are constantly painting a cross motif, reminding us that the painful humiliation of Christ begins with the Incarnation and already points to the crucifixion. In contrast, the words “of the Virgin Mary and became man” are contrasted with ascending movements. The Crucifixus (no. 17) is a choral passacaglia in which the continuo runs through a chromatically descending fourth ( Passus duriusculus ) twelve times . Bach chose the key of E minor, which, according to Mattheson, "cultivates deep thinking / sadness and sadness / but in such a way / that one still hopes to comfort oneself." The surprising turn occurs the 13th time with the words "et sepultus est" (and buried), when the parallel major key is modulated at the burial, the accompanying strings and flutes fall silent and the movement ends in the silence of the grave ( piano ). The full orchestra, woodwinds, timpani and trumpets are followed effectively by Et resurrexit (No. 18) in the form of a festive-doxological concert movement. The vocal parts are led like instruments and have to sing long melisms, fanfare-like triad breaks, virtuoso triplets and sharp notes (in the soprano up to high b 2 ).

The third Article of Faith deals with the Holy Spirit as the third person of the Trinity. The three-part aria Et in Spiritum Sanctum (No. 19 ) takes this into account with a swaying three -piece rhythm in 6/8 time and the exaggerated dominant key of A major (with three accidental signs ). The subsequent a cappella chorus Confiteor (No. 20) is a double fugue with contrapuntal continuo. Like the opening chorus No. 13, the five-part choir movement archaicly picks up on a Gregorian melody that appears as a fifth canon in half notes from bar 73 in alto and bass and from bar 92 in full notes in tenor. The words “et expecto” are effectively heard at the end of the choral movement, initially in an adagio . In daring harmonies and unusual chromatic- enharmonic modulations , all keys of the circle of fifths up to E flat major and G sharp major are traversed. The Credo Vivace e Allegro closes with a tutti orchestra as a solemn doxology with a concertante fugue (No. 21). In this way Bach contrasted the suffering in this world with the expected heavenly glory. The abrupt final chord, which only comprises a quarter note and is followed by a composed rest, prepares for the next part.

Sanctus

While most of the choirs are composed of five parts, the six-part Sanctus No. 22 (two soprano, two alto and two male voices) stands out with the extension to three oboes and refers to the original from 1724. Bach added this reference to the autograph : " The parties [voices] are in Bohemia by Graff Sporck ". Bach changed the original choir (three sopranos, alto, tenor and bass). The Sanctus is in majestic D major and symbolizes the heavenly world with timpani and trumpets as well as the omnipresent triple symbolism: The slow first part in 4/4 time is dominated by chains of triplets , to which the plenary sunt coeli et terra in 3 / 8-stroke follows. In the style of multi-choir music - making, constantly changing groups from the six-part choir, three trumpets, three oboes and three strings compete with each other. Three different rhythms sound at the same time on the words Sanctus . The threefold call to Sanctus illustrates the antiphonally singing angel choirs of Trisagion ( Isa 6,3 VUL ). The octave leaps in the bass, which gradually descend in seconds, give the first part its majestic character. According to Walter Blankenburg , the Sanctus is “not only one of the highlights of the entire work, but also belongs to the mysteriously sublime music that has ever been created”.

Osanna to Dona nobis pacem

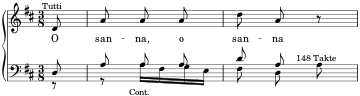

The alternating chant is taken up in Osanna No. 23 , which continues the praise of God at a fast pace in an eight-part double choir. The set is designed as a concertante virtuoso Fuga and wins by the powerful unison - acclamations its monumentality. The altogether 20-part Osanna stands in stark contrast to the tenor aria of Benedictus No. 24 , which is only accompanied by a delicate flute part , the Osanna is then repeated. A violin could also be used in the aria, since Bach does not specify an instrument and the template is not known.

The original of the alto aria Agnus Dei No. 26 , with its chromatically descending semitone steps, is thematically and motivically related to the fugue theme of the first Kyrie and was possibly therefore selected for the last part of the mass in order to form an overarching bracket for the entire work. In terms of key, the G minor falls out of the Mass, but as a minor subdominant to the central D major it can be interpreted as the deep humiliation of the Son of God. This is supported by expressive melodies with falling figures in the alto and in the violin, the Saltus duriusculus . In bar 34, the only fermata in the mass is in the middle of a sentence, which invites you to meditate on the death of the Lord on the cross. The Dona nobis pacem , which closes the mass, draws on the Gratias No. 7 from the Gloria section, links both parts together and in this way gives the request for peace the character of a song of thanks. When Bach reversed the order of the words on the second theme (“pacem dona nobis”), the word peace is given a particularly strong weight.

meaning

Bach's only Missa tota is his last choral work and at the same time his most extensive Latin church work. It stands in the tradition of the concertante orchestral mass (Missa concertata) , but is larger in size and richer than its predecessor. In addition, the B minor Mass differs from its predecessors in the way it deals with the instruments, which not only play an accompanying role, but also make an independent contribution to the theological and symbolic interpretation of the text of the fair. In addition to creative new compositions, it includes extensive revisions of earlier movements that Bach obviously considered his most successful works, and combines them into an "opus ultimum". Despite the diversity of the material, the long period of creation and the variety of archaic, traditional and modern forms and stylistic devices, Bach managed to create a self-contained vocal cycle with a high level of expressiveness. The mass is dominated by a continuous contrapuntal density, which is particularly reflected in the artistic choral fugues. Due to the “highest level of technical mastery at all levels”, the B minor Mass can be described as a “musical legacy” and a summary of his vocal work.

Unlike the cantatas, which are dialogically based on contemplation and address the subjective-affective element in the listener, and unlike the passions, which aim at dramatic visualization, the B minor Mass is characterized by objectivity, abstraction and universality. This is due on the one hand by the Latin liturgical text that the generally applicable interdenominational summarizes healing statements and the B Minor Mass facilitated by the language the international popularity. On the other hand, the mass is the most traditional musical vocal genre in the field of Christian music. Bach took this into account, especially in the choral movements, with a retrospective way of composing, drawing on the classical vocal polyphony in the antico style and taking up various gradual melodies of Gregorian chant .

The high esteem of the fair has been reflected since the 19th century in numerous superlative descriptions and the designation as "high fair". The Bach biographer Philipp Spitta judged in 1880: "Everything from Bach's compositions could be lost, the B minor Mass alone would bear witness to this artist for an indefinite period of time, as with the power of a divine revelation." In contrast to other vocal works by Bach, the cantatas, oratorios and passions, which were largely forgotten for almost 100 years after his death, the B minor mass was in high regard and enjoyed a legendary reputation. The musicologist Friedrich Blume considered it "one of the most impressive testimonies that history knows, of the non-denominational and pan-European spirit that permeated music at the end of the Baroque era". Today the two-hour, demanding mass is part of the standard repertoire of professional choirs and is performed most frequently by the major Bach works worldwide. In October 2015, her autograph was included in the UNESCO World Document Heritage .

Overview

Bach divided the five-part ordinarium into four separately stapled parts. The 27 individual successive movements consist of 18 choirs and 9 arias. The arias are highlighted in blue in the table.

The numbering in the first column is based on the Bach Works Directory (BWV) and the Bach Compendium (BC). In the second column the count of the New Bach Edition is given.

| No. | NBA | sentence | key | Tact | Singer | Instrumentation | Parody template | Remarks | Incipit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. | Missa | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | Kyrie eleison | B minor | 4/4 | Coro (S SATB ) | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboi d'amore, bassoon, violin I, II, viola, continuo | Kyrie in C minor (?) |

|

|

| 2 | 2 | Christe eleison | D major | 4/4 | Soprano I , II solo | Violin I, II, continuo | Original suspected |

|

|

| 3 | 3 | Kyrie eleison | F sharp minor | 4/2 | Coro (SATB) | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboi d'amore, bassoon, violin I, II, viola, continuo |

|

||

| 4th | 4th | Gloria in excelsis | D major | 3/8 | Coro (SSATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, bassoon, violin I, II, viola, continuo | Original suspected | Parody template for BWV 191 /1 |

|

| 5 | 5 | Et in terra pax | D major | 4/4 | Coro (SSATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, bassoon, violin I, II, viola, continuo | Original suspected | attacca , parody original for BWV 191/1 |

|

| 6th | 6th | Laudamus te | A major | 4/4 | Soprano II solo | Violin solo, violin I, II, viola, continuo | Original suspected |

|

|

| 7th | 7th | Gratias agimus tibi | D major | 4/2 | Coro (SATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, bassoon, violin I, II, viola, continuo | BWV 29/2 (1731) | like Dona nobis pacem (No. 27) |

|

| 8th | 8th | Domine Deus | G major | 4/4 | Soprano I, tenor solo | Transverse flute, violin I, II, viola, continuo | possibly BWV 193a / 5 (music missing) | Parody template for BWV 191/2 |

|

| 9 | 9 | Qui tollis peccata mundi | B minor | 3/4 | Coro (SATB) | 2 transverse flutes, violin I, II, viola, violoncello, continuo | BWV 46/1 (1723) |

|

|

| 10 | 10 | Qui sedes ad dextram Patris | B minor | 6/8 | Alto solo | Oboe d'amore, violin I, II, viola, continuo | Original suspected |

|

|

| 11 | 11 | Quoniam tu solus sanctus | D major | 3/4 | Basso solo | Cornu da caccia, 2 bassoons, continuo | Original suspected |

|

|

| 12 | 12 | Cum Sancto Spiritu | D major | 3/4 | Coro (SSATB) | 3 trumpets, cornu da caccia, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, violin I, II, viola, continuo | Parody template for BWV 191/3 |

|

|

| II | Creed | ||||||||

| 13 | 1 | Credo in unum Deum | A- Mixolydian | 4/2 | Coro (SSATB) | Violin I, II, continuo |

|

||

| 14th | 2 | Father omnipotent | D major | 2/2 | Coro (SATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 oboes, violin I, II, viola, continuo | Lost original for BWV 171/1 (1729 or 1737) |

|

|

| 15th | 3 | Et in unum dominum | G major | 4/4 | Soprano I, alto solo | 2 oboe d'amore, violin I, II, viola, continuo | Lost duet, which was to serve as a parody model for BWV 213/11 as early as 1733 | 2 variants |

|

| 16 | 4th | Et incarnatus est | B minor | 3/4 | Coro (SSATB) | Violin I, II, continuo |

|

||

| 17th | 5 | Crucifixus | E minor | 3/2 | Coro (SATB) | 2 transverse flutes, violin I, II, viola, continuo | BWV 12/2 (1714) |

|

|

| 18th | 6th | Et resurrexit | D major | 3/4 | Coro (SSATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, violin I, II, viola, continuo | presumably BWV appendix 9/1 |

|

|

| 19th | 7th | Et in Spiritum Sanctum | A major | 6/8 | Basso solo | 2 oboe d'amore, continuo | Original suspected |

|

|

| 20th | 8th | Confiteor | F sharp minor | 2/2 | Coro (SSATB) | Continuo |

|

||

| 21st | 9 | Et expecto | D major | 2/2 | Coro (SSATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, violin I, II, viola, continuo | BWV 120/2 (1729) |

|

|

| III | Sanctus | ||||||||

| 22nd | - | Sanctus | D major | 4/4; 3/8 | Coro | 3 trumpets, timpani, 3 oboes, violin I, II, viola, continuo | BWV 232 III (1724) |

|

|

| IV | Osanna, Benedictus, Agnus Dei, Dona nobis pacem | ||||||||

| 23 | 1 | Osanna in excelsis | D major | 3/8 | Coro (SATBSATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, violin I, II, viola, continuo | probably BWV Anh. 11/1 (1732) | → BWV 215 /1 |

|

| 24 | 2 | Benedictus | B minor | 3/4 | Tenor solo | Transverse flute (or violin), continuo | Original suspected |

|

|

| 25th | 3 | Osanna repetition | D major | 3/8 | Coro (SATBSATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, violin I, II, viola, continuo | like No. 23 | Repeat # 23 |

|

| 26th | 4th | Agnus Dei | G minor | 4/4 | Alto solo | Violin I, II, continuo | probably BWV Anh. 196/3 (1725), BWV 11 |

|

|

| 27 | 5 | Dona nobis pacem | D major | 4/2 | Coro (SATB) | 3 trumpets, timpani, 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, violin I, II, viola, continuo | BWV 232 I / 7 | BWV 29/2 like Gratias agimus tibi (No. 7) |

|

Recordings / sound carriers (selection)

The list contains a selection of influential recordings and takes particular account of the phonograms currently available on the market.

On modern instruments

- Hermann Scherchen , Vienna Academy Chamber Choir , Vienna Symphony Orchestra ; Soloists: Emmy Loose , Hilde Ceska , Gertrud Burgsthaler-Schuster , Anton Dermota , Alfred Poell . Westminster, 1950.

- Karl Richter , Munich Bach Choir & Orchestra; Soloists: Maria Stader , Hertha Töpper , Ernst Haefliger , Kieth Engen , Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau . Deutsche Grammophon, 1961.

- Herbert von Karajan , Vienna Singing Association , Berlin Philharmonic ; Soloists: Gundula Janowitz , Christa Ludwig , Peter Schreier , Robert Kerns , Karl Ridderbusch . Deutsche Grammophon, 1973/1974.

- Peter Schreier , Leipzig Radio Choir , New Bachisches Collegium Musicum ; Soloists Lucia Popp , Carolyn Watkinson , Siegfried Lorenz , Theo Adam . Berlin, 1981.

- Karl-Friedrich Beringer , Windsbach Boys Choir , German Chamber Academy ; Soloists: Christine Schäfer , Ingeborg Danz , Markus Schäfer , Thomas Quasthoff . Rondeau, 1994.

- Georg Christoph Biller , St. Thomas ' Choir , Gewandhaus Orchestra ; Soloists: Ruth Holton , Matthias Rexroth , Christoph Genz , Klaus Mertens . EuroArts, 2001.

- Herbert Blomstedt , Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra; Soloists: Ruth Ziesak , Anna Larsson, Christoph Genz, Dietrich Henschel . EuroArts, 2005.

- Helmuth Rilling : Gächinger Kantorei Stuttgart , Bach-Collegium Stuttgart ; Soloists: Marlis Petersen , Stella Doufexis , Anke Vondung , Lothar Odinius . Hänssler, 2005.

On historical instruments

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt , Vienna Boys' Choir , Concentus Musicus Vienna ; Soloists: Rotraut Hansmann , Helen Watts , Kurt Equiluz , Max van Egmond . Telefunken / TELDEC, 1968.

- John Eliot Gardiner , Monteverdi Choir , English Baroque Soloists . Deutsche Grammophon, 1984.

- Gustav Leonhardt , Nederlandse Bachvereniging , La Petite Bande ; Soloists: Isabelle Poulenard , Guillemette Laurens , René Jacobs, John Elwes , Max van Egmond , Harry van der Kamp . German Harmonia Mundi, 1985.

- René Jacobs , Academy for Early Music Berlin ; Soloists: Hillevi Martinpelto, Bernarda Fink , Christoph Prégardien , Matthias Goerne . Berlin, 1992.

- Hermann Max , Rheinische Kantorei , The Little Concert ; Soloists: Veronika Winter , Johanna Koslowsky , Kai Wessel , Markus Brutscher , Hans-Georg Wimmer, Stephan Schreckenberger . Capriccio, 1992.

- Harry Christophers, The Sixteen , Symphony of Harmony & Invention; Soloists: Catherine Dubosc, Catherine Denley, James Bowman, John Mark Ainsley, Michael George; Bach Edition - Brillant Classics, 1994; recorded in St. Augustines Kilburn London.

- Thomas Hengelbrock , Balthasar Neumann Choir , Freiburg Baroque Orchestra . German Harmonia Mundi, 1996.

- Masaaki Suzuki , Bach Collegium Japan ; Soloists: Carolyn Sampson, Rachel Nicholis , Robin Blaze , Gerd Türk . UP, 2006.

- Philippe Herreweghe , Collegium Vocale Gent ; Soloists: Dorothee Mields , Hana Blažíková , Thomas Hoobs, Peter Kooij . Philips, 2011.

- Jordi Savall , La Capella Reial de Catalunya , Le Concert des Nations; Soloists: Celine Scheen , Yetzabel Arias Fernández, Pascal Bertin, Makoto Sakurada, Stephan MacLeod. AliaVox, 2012.

- Georg Christoph Biller , St. Thomas Choir Leipzig (selection choir), Freiburg Baroque Orchestra; Soloists: Reglint Bühler, Susanne Krumbiegel, Susanne Langner, Martin Lattke , Markus Flaig . Accentus Music, 2014.

- Hans-Christoph Rademann , Gächinger Kantorei Stuttgart, Freiburg Baroque Orchestra; Soloists: Carolyn Sampson , Anke Vondung, Daniel Johannsen , Tobias Berndt. Carus, 2015.

- Jos van Veldhoven , Nederlandse Bachvereniging ; Soloists: Hana Blažíková , Anna Reinhold , David Erler, Thomas Hobbs, Peter Harvey . allofbach, 2016.

- Michael Schönheit , Collegium Vocale Leipzig, Merseburger Hofmusik; Soloists: Gerlinde Sämann, Britta Schwarz, Henriette Gödde , Falk Hoffmann, Andreas Scheibner. Querstand, 2017.

- Rudolf Lutz , choir and orchestra of the JS Bach Foundation ; Soloists: Julia Doyle , Alex Potter , Daniel Johannsen , Klaus Mertens . JS Bach Foundation, 2017.

With a solo cast

- Joshua Rifkin : The Bach Ensemble, Judith Nelson, Jiulianne Baird, Jeffrey Dooley, Frank Hoffmeister, Jan Opalach. Nonesuch Ultima, 1982.

- Andrew Parrott , Taverner Consort and Players, Emma Kirkby, Emily van Evera, Panito Iconomou, Christian Immler, Michael Kilian, Rogers Covey-Crump, David Thomas, Rogers Covey-Crump, David Thomas Plg Classics (Warner) 2002

- Konrad Junghänel , Cantus Cölln (Johanna Koslowsky, Mechthild Bach , Monika Mauch, Susanne Rydén, Elisabeth Popien, Henning Voss, Hans Jörg Mammel , Wilfried Jochens , Stephan Schreckenberger, Wolf Matthias Friedrich). Harmonia Mundi France, 2003.

- Frans Brüggen , Orchestra of the 18th Century , Dorothee Mields , Johannette Zomer , Patrick van Goethem , Jan Kobow , Peter Kooij . Glossa, 2009.

- Sigiswald Kuijken , La Petite Bande , Gerlinde Sämann , Elisabeth Hermans, Patrizia Hardt, Petra Noskaiová , Bernhard Hunziker, Christoph Genz, Marcus Niedermeyr and Jan Van der Crabben . Challenge, 2011.

- Lars Ulrik Mortensen , Concerto Copenhagen, Maria Keohane , Joanne Lunn, Alex Potter, Jan Kobow , Peter Harvey , Else Torp, Hanna Kappelin. CPO, 2011.

See also

literature

Sheet music editions

- Johann Sebastian Bach: High Mass in B minor . Facsimile edition of the manuscript. Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1924.

- Christoph Wolff (Ed.): Bach, Johann Sebastian (1685–1750), Mass in B minor BWV 232 . Facsimile of the autograph score. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1996, ISBN 3-7618-1170-5 .

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Mass in B minor BWV 232. With Sanctus in D major (1724) BWV 232III . Commentary by Christoph Wolff. Ed .: Christoph Wolff. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2009, ISBN 978-3-7618-1911-1 (facsimile based on the autograph).

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Mass in B minor BWV 232 . Ed .: Joshua Rifkin . Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden 2006 ( Explanations on the edition history of the B minor Mass [PDF] score, urtext).

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Mass in B minor. BWV 232 . for solos, choir and orchestra. Ed .: Christoph Wolff. CF Peters, Frankfurt am Main 1997 (study score, urtext).

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Mass in B minor BWV 232 . later called: Mass in B minor. Ed .: Uwe Wolf (= new edition of all works; rev. Ed., Vol. 1 ). Bärenreiter, Kassel 2010, ISBN 979-0-00620526-4 (study score, urtext).

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Mass in B minor BWV 232 . Ed .: Friedrich Smend (= new edition of all works, Series II, Volume 1 ). 10th edition. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012 (score, urtext (1954)).

Secondary literature

- Walter Blankenburg : Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass . 5th edition. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1996, ISBN 3-7618-1170-5 .

- Johan Bouman : Music for the Glory of God. Music as a gift from God and proclamation of the Gospel with Johann Sebastian Bach . 2nd Edition. Brunnen, Giessen 2000, ISBN 3-7655-1201-X .

- John Butt: Mass in B Minor . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1991, ISBN 0-521-38280-7 .

- Georg von Dadelsen : Digression on the B minor Mass . In: Walter Blankenburg (Ed.): Johann Sebastian Bach (= ways of research ; 170 ). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1970, p. 334-352 .

- Hans Darmstadt: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor. BWV 232 (based on the edition of the NBA / rev. 2010). Analyzes and comments on the compositional technique with practical performance and theological notes. Klangfarben-Musikverlag, Dortmund 2012, ISBN 978-3-932676-17-8 .

- Wilhelm Otto Deutsch: gestures of acceptance, metamorphosis, kinship . A contribution to the musical hermeneutics of JS Bach in the B minor Mass. In: Music and Church . tape 62 , no. 6 , 1992, ISSN 0027-4771 , pp. 321-327 .

- Yoshitake Kobayashi: The universality in Bach's B minor Mass . A contribution to the Bach picture of the last years of life. In: Music and Church . tape 57 , 1987, ISSN 0027-4771 , pp. 9-24 .

- Konrad Küster (Ed.): Bach Handbook . Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel / Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-7618-2000-3 .

- Michael Maul: The great catholic mass . Bach, Graf Questenberg and the Musicalische Congregation in Vienna. In: Bach yearbook . tape 95 , 2009, ISSN 0084-7682 , p. 153-175 ( qucosa.de ).

- Ulrich Prinz (Ed.): Johann Sebastian Bach, Mass in B minor “Opus ultimum”, BWV 232 . Lectures of the master courses and summer academies JS Bach 1980, 1983 and 1989 (= series of publications of the International Bach Academy Stuttgart; 3 ). Bärenreiter / Cambridge University Press, Kassel / Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-7618-0997-2 .

- Helmuth Rilling : Johann Sebastian Bach's B minor Mass . Hänssler, Neuhausen / Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-7751-0470-4 .

- Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach, Mass in B minor (= Bärenreiter work introduction ). Bärenreiter, Kassel 2009, ISBN 978-3-7618-1578-6 .

- Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-10-092584-X .

Web links

Digital copies

- Original score , Berlin State Library

- Original score of the Sanctus (first version 1724) , Berlin State Library

Sheet music and audio files

- Bach's B Minor Mass : Sheet Music and Audio Files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Sheet music in the public domain for the B minor Mass in the Choral Public Domain Library - ChoralWiki (English)

- Mass in B minor (MIDI / MP3) with practice files for choristers

- Mass in B minor with a photo of Helmuth Rilling and a photo facsimile from Insel Verlag

Further information

- Günter Brick: The B minor Mass by JS Bach. (PDF; 284 kB) in the download archive of the Berliner Kantorei , accessed on June 9, 2017.

- Mass in B minor (B minor mass) - source material at Bach Digital of the Leipzig Bach Archive

Individual evidence

- ^ Luther writings and Bach's B minor mass are world document heritage. UNESCO press release of October 9, 2015.

- ↑ a b c Joshua Rifkin : Explanations on the edition history of the B minor Mass . (PDF) p. V; accessed November 27, 2015.

- ↑ For example Kobayashi: The Universality in Bach's B Minor Mass. 1987, pp. 9-24.

- ^ For example, Hans-Joachim Schulze : JS Bach's Mass in B minor. Observations and Hypotheses with regard to Some Original Sources. In: To Yomita, Elise Crean, Ian Mills (Eds.): International Symposium, Understanding Bach's B-minor Mass . School of Music Camp, Belfast 2007, p. 236: "perhaps in Dresden, Prague, or Vienna, or, indeed, elsewhere".

- ^ Maul: The great Catholic mass. 2009, pp. 168–173, and Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs: The trail leads to Vienna . ( Memento of the original from December 23, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Musikfreunde: Journal of the Society of Music Friends in Vienna . 2010.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, pp. 22, 27.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, pp. 23-25, 31.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . 2000, p. 548, note 64.

- ↑ Christoph Wolff: On the musical history of Kyrie from Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B minor. In: Martin Ruhnke (Ed.): Festschrift Bruno Stäblein for his 70th birthday. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1967, p. 316.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 55.

- ^ Küster: Bach Handbook . 1999, p. 503f.

- ^ Küster: Bach Handbook . 1999, p. 498.

- ↑ JS Bach - Chronologie Bach-Archiv (bach-leipzig.de) accessed on March 16, 2013.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . 2000, p. 397.

- ↑ Markus Rathey: On the genesis of Bach's university music Gloria in Excelsis Deo BWV 191 . In: Bach yearbook . tape 99 , 2013, ISSN 0084-7682 , p. 319-328 , doi : 10.13141 / bjb.v20132989 .

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 17f.

- ↑ a b Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . 2000, p. 479.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, pp. 77f, 126.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 12f.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 22f.

- ↑ Anatoly P. Milka: On the dating of the B minor mass and the art of fugue . In: Bach yearbook . tape 96 , 2010, ISSN 0084-7682 , p. 53-68 , doi : 10.13141 / bjb.v20101880 .

- ↑ Correct that! In: Die Welt , November 7, 2008; Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ↑ Uwe Wolf, Oliver Hahn, Timo Wolff: Who wrote what? X-ray fluorescence analysis on the autograph of JS Bach's mass in B minor BWV 232. In: Bach yearbook . tape 95 , 2009, ISSN 0084-7682 , p. 117-133 , doi : 10.13141 / bjb.v20091862 .

- ^ Peter Wollny: Observations on the autograph of the B minor mass . In: Bach yearbook . tape 95 , 2009, ISSN 0084-7682 , p. 135-151 , doi : 10.13141 / bjb.v20091863 .

- ↑ a b Intelligence sheet for the general musical newspaper , No. 34 of August 26, 1818, p. 28 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ [ untitled ] . In: Messages . NF 6. State Library of Prussian Cultural Heritage, 1997, ISSN 0038-8866 , p. 36, 125 .

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Schulze (ed.): Documents on the aftermath of Johann Sebastian Bach 1750-1800 (= Bach documents . Volume 3 ). Bärenreiter, Kassel 1984, ISBN 3-7618-0249-8 (No. 957).

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 15 f.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 41.

- ↑ Gottfried Eberle: “I brought you back to light”. Zelter and Bach . In: 200 years Sing-Akademie zu Berlin. An art association for sacred music . Nicolai, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-87584-380-0 , p. 82-86 .

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . 2000, p. 478.

- ↑ a b Küster: Bach Handbook . 1999, p. 500.

- ↑ See in detail Küster: Bach Handbook . 1999, pp. 500-503.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 84.

- ↑ Klaus Häfner: About the origin of two movements of the B minor Mass . In: Bach yearbook . tape 63 , 1977, ISSN 0084-7682 , pp. 55-74 , doi : 10.13141 / bjb.v19772028 .

- ^ Rilling: Johann Sebastian Bach's B minor Mass. 1979, p. 75.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 91.

- ↑ For comparison see: René Pérez Torres: Bach's Mass in B minor. An Analytical Study of Parody Movements and their Function in the Large-Scale Architectural Design of the Mass . Master's thesis at the University of North Texas 2005, unt.edu (PDF).

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . 2000, p. 392.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 14.

- ↑ Christoph Wolff: The stile antico in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Studies on Bach's late work. Steiner, Erlangen-Nürnberg 1968, p. 34.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Martin Zenck: The Bach Reception of the Late Beethoven (= Archive for Musicology . Supplement 24). Steiner, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-515-03312-0 , p. 51 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ Christoph Nichelmann: The melody according to its essence as well as its properties . Johann Christian Schuster, Danzig 1755, p. 138 and Table XVIII ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Johann Philipp Kirnberger: The art of the pure sentence in music . Second part, second division. GJ Decker and GL Hartung, Berlin / Königsberg 1777, p. 172 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Friedrich Blume: History of Protestant Church Music. 2nd Edition. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1965, ISBN 3-7618-0083-5 , p. 210.

- ^ Hinrich Lichtenstein : On the history of the Sing-Akademie in Berlin. Along with a message about the festival on the fiftieth anniversary of your foundation. Verlag von Trautwein & Co., Berlin 1843, p. XXII.

- ↑ Andreas Waczkat: Friedrich Konrad Griepenkerl (1782-1849) . (PDF) accessed February 2, 2013.

- ↑ Swantje Richter: Introductory text. ( Memento of the original from February 16, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 27 kB) kreuzchor.de; Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 20.

- ↑ a b Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor. 2009, p. 49.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Andrew Parrott: Bach's Choir . To a new understanding . Metzler / Bärenreiter, Stuttgart / Kassel 2003, ISBN 3-7618-2023-2 , p. 66-107 .

- ^ For example, Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 14.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Peter Wagner (ed.): The gradual of St. Thomas Church in Leipzig . Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1930, p. VIIIf.

- ^ Johann Mattheson: The newly opened orchestra . Hamburg 1713, p. 251, koelnklavier.de , accessed January 27, 2013.

- ^ Küster: Bach Handbook . 1999, p. 504f.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, p. 60f.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 31.

- ^ Johann Mattheson: The newly opened orchestra. Hamburg 1713, p. 242 koelnklavier.de, accessed February 15, 2013.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 41f.

- ^ Küster: Bach Handbook. 1999, p. 507.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 46.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 63f.

- ↑ Bouman: Music for the Glory of God. 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Philipp Spitta: Johann Sebastian Bach. Volume 2. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1880, p. 532, zeno.org

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . 2000, pp. 478, 488.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 74f.

- ^ Johann Mattheson: The newly opened orchestra. Hamburg 1713, p. 239, koelnklavier.de, accessed February 15, 2013.

- ↑ Bouman: Music for the Glory of God. 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Rilling: Johann Sebastian Bach's B minor Mass. 1979, pp. 82-84.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor. 2009, p. 95f.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 86.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . 2000, p. 480.

- ^ Rilling: Johann Sebastian Bach's B minor Mass. 1979, pp. 114, 143.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor. 2009, p. 108.

- ^ Rilling: Johann Sebastian Bach's B minor Mass. 1979, pp. 122, 125.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 95.

- ↑ Friedrich Smend's suggestion to use a flute prevailed. Cf. Alfred Dürr: Johann Sebastian Bach's church music in his time and today . In: Walter Blankenburg (Ed.): Johann Sebastian Bach (= ways of research; 170 ). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1970, p. 298 .

- ^ Rilling: Johann Sebastian Bach's B minor Mass. 1979, p. 149.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, p. 99.

- ^ Rilling: Johann Sebastian Bach's B minor Mass. 1979, p. 150f.

- ↑ a b c Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach . 2000, p. 481.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. Mass in B minor . 2009, pp. 26-29.

- ^ Blankenburg: Introduction to Bach's B minor Mass. 1996, pp. 25, 103-105.

- ^ Prince: Johann Sebastian Bach, Mass in B minor "Opus ultimum", BWV 232. 1990.

- ^ Peter Tenhaef, Walter Werbeck (ed.): Mass and parody with Johann Sebastian Bach. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-631-50119-6 , p. 115.

- ^ Dadelsen: Excursus on the B minor Mass . 1970 (1958), p. 351.

- ^ Philipp Spitta: Johann Sebastian Bach. Volume 2. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1880, p. 544, zeno.org