doping

Under Doping is defined as the taking of illicit substances or the use of illegal methods to increase or to maintain the - mostly sports - performance.

Doping is largely forbidden in sport, as the use of doping substances, which is often associated with the risk of damage to health , leads to an unequal distribution of opportunities in sporting competition. In addition, there is a relationship to drug abuse with the risk of developing addictions through to drug abuse .

There is no uniform logic of the prohibitions: Every year in late autumn the list of prohibited substances is checked; the new list will then apply from January 1st of the following year. In spite of the short time in which the doping test can detect the presence of doping substances in the urine, such tests have a considerable threat potential, but the success seems limited.

The term is also used in the professional field in connection with stimulants and desired or (supposedly) required increases in B. Attention, perseverance, performance and stress resistance are used. According to the 2015 health report published by the German Employees Health Insurance Fund (“ DAK-Gesundheit ”) in spring 2015, an estimated up to 5 million employees use prescription drugs at times in this context .

Performance-enhancing substances are used in many societies outside of sport, sometimes with a prescription. For example, the use of substances developed from research in the military and whose use in sport is considered doping is the order of the day in the USA.

Origin of the word

The word "doping" comes from English and is the gerund of the verb to dope (= administer drugs). Its etymological origin, however, lies in Afrikaans , a language derived from Dutch in South Africa : A heavy schnapps, the so-called "dop", was drunk at village celebrations of the locals - the Afrikaans took over the word and used it as a general term for drinks with a stimulating effect . The word found its way from Afrikaans into English, where it was eventually used in connection with stimulants used in horse races. When the term first appeared in an English lexicon in 1889, it also referred to the administration of a mixture of opium and various narcotics to racehorses.

At the beginning of the 20th century, substances such as cocaine, morphine, strychnine and caffeine were referred to as "doping agents". With the invention of synthetic hormones in the 1930s, drug doping found its way into sport. The first doping tests at the Olympic Games were carried out in 1968 during the Winter Games in Grenoble and the Summer Games in Mexico.

definition

So far there is no precise formulation that limits what is and what is not doping. In 1963, the Euro Council "artificial and unfair increase in the administration or the use of exogenous substances in any form and physiological substances in abnormal shape or abnormal way to healthy people with the sole purpose of the performance for the competition." Defined doping as

for putting up Doping rules, however, this definition was too imprecise (the phrase "in abnormal form" alone left too much room for interpretation). Therefore, on the one hand, definitions under sports law have been developed which are intended to clarify what should and should not be considered doping from the perspective of sports law. In addition, however, there are broader definitions that are of great importance for public discourse, for sports education and doping prevention, and for the professional assessment of medical-ethical behavior.

There is also the special form of "mechanical doping", in which motors are used primarily as power amplifiers. While these would be clearly visible in the case of exoskeletons in competition, it has apparently been possible to hide motors in bicycles that were used in cycling . The transformation of athletes into cyborgs is also conceivable . In this case, performance-enhancing objects would be built into (and partly also on) the athlete's body. Hugh Herr , a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology , who had lost both lower legs in an accident and with two high-tech prostheses a steep face faster with two high-tech prostheses , proved that a “cyborg” can be more powerful than a person who has not been “improved” with electronic and mechanical aids climbed up as his friends with no amputated limbs.

Sports law definition

In 1977 the German Sports Confederation defined doping as the “attempt to increase performance in an unphysiological way through the use of doping substances (...)”, but within the definition itself used the term “doping” or “doping substances”. At the 1999 World Doping Conference in Lausanne, a new definition was finally established that determined doping through a list of expressly prohibited substances and behavior. A draft of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) served as the basis:

“Doping is defined as 1. the use of an aid (substance or method) that is potentially hazardous to health and improves the athlete's athletic performance, and 2. the presence in the body of an athlete of a substance that is on the list corresponding to the current one Medical Code attached, or the use of a method that appears on this list. "

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) definition of doping has been in effect since January 1, 2004 . She expanded the IOC rules. The different sections of the definition are summarized in Articles 1 and 2 of the World Anti-Doping Code. The annually revised definition of the substances and procedures prohibited in competition and / or training makes it more difficult to systematically prosecute doping offenses.

Sports pedagogical definition / doping from a prevention-theoretical point of view

From the point of view of doping prevention and medical ethics, broader definitions apply in addition to this definition of "doping in the narrower sense". They are not decisive for the doping discussion under sport law, but they correspond closely to the public discourse on doping and are decisive for prevention. One could speak of "doping in the broader sense" or of "doping mentality". According to Andreas Singler (2011, p. 38), this is the case "if funds are taken specifically to increase performance, regardless of whether they are prohibited or not". The French health sociologist Patrick Laure also uses the concept of doping mentality, even if substances that are not prohibited by sports law - even if they are "only" so-called dietary supplements - should be used. The willingness to take medication or substances to improve performance, even in areas that are not forbidden under sports law, can be viewed as a sign of a lack of self-efficacy and, from a psychological point of view, refers to the lack of an important protective factor against doping (Singler ibid.).

Medical ethical definition of doping

The professional code for doctors and z. For example, the Lisbon Declaration forbid doctors to use drugs or other substances to perform treatments to improve performance. Therefore, all medical-pharmacological interventions that serve to improve performance and with which a medical indication cannot be connected are to be rejected from a medical ethical point of view. In 1992, the professional court for doctors in Freiburg designated any form of medically not indicated medical intervention as doping. Sports law considerations do not limit this assessment. The administrative lawyer Joachim Linck (1987) also saw any form of non-indicated intervention as doping - from a medical point of view - with reference to the professional code and professional conventions for doctors.

Types of doping

A special variant of the increase in performance is boosting . Hereby an athlete inflicts pain due to the adrenaline rush. Insofar as it is an illegal method of increasing performance, it can be classified as doping.

Active ingredient groups and their effects on the organism

The following three groups are distinguished in doping:

- prohibited substances,

- prohibited methods that can be used to improve the athlete's performance,

- Active ingredients that are subject to certain restrictions.

The group of prohibited substances is divided into stimulants, narcotics, anabolic steroids , diuretics and peptide and glycoprotein hormones . All substances that are related in terms of their effect or chemical structure to the substances mentioned above are also prohibited. Some professional associations have expanded their doping lists to include other doping classes, for example FITA , which also lists antipsychotics, anxiolytics , hypnotics / sedatives and antidepressants, because they can significantly influence the archery process.

| medium | Examples | effect |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide and glycoprotein hormones | Growth Hormone (HGH), Erythropoietin (EPO) | Increase in red blood cells, improve oxygen transport, accelerate growth |

| Anabolic steroids | Nandrolone , Dianabol, Stanozolol | Reinforcement of muscular growth, shorter regeneration times, anti-inflammatory effects |

| Stimulants | Amphetamine , Ephedrine , Captagon, Cocaine , THC | Increased alertness, increased pain threshold, improved concentration, increased willingness to take risks |

| Narcotics | Morphine | Numb pain |

Stimulants

Examples of stimulants are ephedrine and other amphetamine derivatives , purine alkaloids (xanthines) such as caffeine and other substances such as cocaine . The chemical structures of amphetamine or ephedrine, for example, are similar to the body's own hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline. Stimulants act on the central nervous system and increase motor activity. The side effects of stimulants are symptoms of stress and persistent aggression. When excessive stimulant intake occurs, the body's warning system no longer reacts and all remaining body reserves are used up without the athlete noticing. This then leads to severe exhaustion, fainting and, in extreme cases, death. Stimulants are occasionally used in medicine. Ephedrines cause the bronchial tubes to relax and the nasal mucous membrane to swell, which is why they can be found in many cold remedies.An example of this would be pseudoephedrine , which is currently used in Germany - exclusively in combination with other drugs such as cetirizine or acetylsalicylic acid . By taking cold medicines that contain ephedrine, an athlete violates the doping ban and has to reckon with the same consequences as if they intentionally take a doping substance. In 2002 Jan Ullrich tested positive for amphetamines during a stay in a rehabilitation clinic and received a six-month doping ban. In the meantime (2013) he would no longer be banned for this, since stimulants are only forbidden in competition, but not in training.

Caffeine also belongs to the group of stimulants. From 1984 to 2004, exceeding the tolerance value of 12 mg per liter of urine was considered doping, but has now been completely removed from the doping list. It has been shown that after taking caffeine, the concentration of free fatty acids in the blood increased. For endurance athletes, these empirical data, which are not yet completely undisputed in science, are of very high relevance. Because endurance athletes are interested in conserving their glycogen stores for a final sprint and running fat-burning. The effects of caffeine develop an hour to an hour and a half after ingestion and last about four to five hours.

Narcotics

Various classes of substances are grouped under narcotics . Well-known classes include sedatives , to which the benzodiazepines belong, and analgesics (pain relievers), such as opioids , which consist of morphine , other morphine derivatives and other substances that have morphine-like properties. The best-known opioids include heroin , methadone and tramadol , which are either produced from opium , which in turn is obtained from opium poppies , or are produced entirely synthetically. Analgesics have a pain-suppressing effect and are u. a. given shortly after operations or as long-term therapy for very serious diseases such as cancer. In sport, narcotics are misused for various purposes. Because of their calming effect on the human organism, they are used in sports such as golf and sport shooting (especially sedatives such as Valium ). Furthermore, if the dosage is too high, they lead to fainting and clouding of consciousness. However, athletes must be careful when taking cold medicines, as they often contain codeine, which is not forbidden, but which the body converts to a certain extent into morphine. If the limit value of 1 mg morphine per liter urine is not exceeded, the sample is to be assessed as negative.

Anabolic steroids

Under anabolic steroids anabolic steroids are usually understood. Almost all anabolic steroids are derivatives (descendants) of the male sex hormone testosterone (pure testosterone is also one of the anabolic steroids). If testosterone is supplied from the outside, the muscle mass increases without body fat being stored. The existing body fat may even be reduced. Thus, anabolic steroids are interesting for sports in which muscle mass is crucial, for speed strength . Examples are sprinting , long jump and weight lifting , also bodybuilding .

Anabolic steroids are also used in endurance sports. They stimulate protein synthesis and, above all, improve the body's ability to regenerate. The oxygen is transported better in the body. This has decisive advantages, especially in training phases in which you train at high intensity. Anabolic steroids can even increase performance in the short term. A well-known example is a stage win of the cyclist Floyd Landis in the Tour de France 2006. The day before, his performance had plummeted, he was ten minutes behind the day's winner. The explanation for the stage win was later provided by the positive testosterone test.

However, anabolic steroids come with many side effects . Men may become “more feminine” because if there is too much testosterone in their body, it is partially converted (“aromatized”) into the female sex hormone, estrogen . The mammary glands can grow, a female breast develops (gynecomastia), fewer sperm are produced and the testicles shrink. In addition, the body produces less of its own testosterone or even ceases to do so with constant intake.

Women, on the other hand, become “more masculine”: the breast may recede, baldness appears, whiskers grow, the larynx grows and provides a deeper voice, the clitoris grows. Teenagers may experience less growth. Other common side effects are high blood pressure , acne , hair loss, deteriorated liver values, injuries to ligaments and tendons , irritability and depression .

Since testosterone occurs naturally in the body, anabolic steroids are not easily detected. In addition, dismantling takes place within two days. The checkers are helped by the epitestosterone content: Normally it should be contained in the urine in a ratio of 1: 1. A deviation is an indication of a drug that has been added. However, some athletes have injected epitestosterone to compensate for the value. In any case, the performance of athletes in strength and speed sports fell sharply after controls were introduced in training .

In medicine , anabolic steroids are used for hormonal disorders. The body is supplied with hormones that it can no longer produce itself. A well-known doping agent in this category is stanozolol .

Diuretics

Diuretics are the only doping substances that do not cause an increase in performance, but rather a decrease in the performance of the athlete. Examples of prohibited agents are acetazolamide , furosemide and mersalyl . Diuretics are used in sports with weight classes such as judo and wrestling , in which the athlete absolutely has to maintain his weight, otherwise he is not allowed to start in competitions. Between the weigh-in and the competition, the athlete replenishes the losses and is thus more efficient than his competitors. This doping agent is also used in equestrian sports, as athletes have to be extremely light in order to achieve good performance. In bodybuilding , diuretics are mostly used to get rid of the water stored in the subcutaneous fat tissue, since as many muscle parts of the athlete as possible should be recognizable.

Strong diuretics are able to bring about a large loss of water in a few hours, which can result in a weight reduction of one to three kilograms. The body loses many minerals due to the rapid dehydration . This weakens the athlete's performance and can lead to muscle cramps and kidney damage.

Diuretics are difficult to detect in doping controls because most of them are flushed out of the body with the urine . Because of this effect, diuretics are often used as masking agents to make it more difficult to detect other doping agents. They are used in medicine to reduce the accumulation of water in tissues .

Peptide and glycoprotein hormones

Peptide and glycoprotein hormones are all endogenous proteins . These include HGH , corticotropin, and erythropoietin . As a side effect, deformations occur in parts of the body.

Corticotropin, also known by the acronym ACTH, regulates the body's own production of cortisol and can lead to euphoria . ACTH causes the breakdown or redistribution of the body's own energy reserves in the form of fat and sugar and promotes infections by suppressing the body's inflammatory response .

Taking erythropoietin (EPO) greatly increases the number of red blood cells in the blood . This means that more oxygen can be transported in the blood. This increases the endurance of the athlete , which is used in cycling , marathons and skiing . It was only recently that a method was found that can clearly demonstrate the use of this hormone . Today it is possible to detect EPO through a urine test . Arterial hypertension (high blood pressure) and changes in the flow properties of the blood are known to be side effects of EPO . The blood becomes thicker, which increases the risk of clogging the coronary arteries and causing the athlete to have a heart attack . Fine veins ( capillaries ) in the brain or in the lungs can also no longer be supplied, which considerably increases the risk of a heart attack or stroke.

The medical purpose is the treatment of anemia or the support of the therapy of cancer patients after chemotherapy .

Epo and blood doping

Erythropoietin (EPO) is (in addition to the permitted creatine ) the “fashion drug” in sports, especially in endurance sports.

Under Blood doping is defined as the administration of whole blood or of preparations containing red blood cells. This measure increases the number of erythrocytes in the blood. The oxygen transport capacity is thus improved. The actual blood doping (transfusion of autologous or foreign blood with increased red blood cells) has been known since the Olympic victories of the Finnish long-distance runner Lasse Virén in 1972 , who were subject to such blood transfusions (which were not yet prohibited at the time).

→ Erythropoietin as a doping agent

Methods

Since January 1, 2003, for the first time, prohibited methods have been described in more detail in the doping rules. They are divided into three groups: increasing the transport capacity for oxygen as well as gene doping and active substances that are subject to certain restrictions.

Increasing the transport capacity for oxygen

The performance of many athletes depends on their endurance, which in turn depends on the oxygen supply in the muscles . One method of increasing the blood's ability to transport oxygen is through blood doping . This involves drawing a larger amount of blood after altitude training , after which there are more red blood cells in the blood than usual. This blood is stored and then transfused into the athlete's body shortly before a later competition . As a result, he has an increased number of red blood cells in his blood and his performance increases. This means that the blood collection, which is initially poor in performance, can be carried out well before an important competition. This method cannot be directly detected as long as it is transfused autologous blood and not foreign or animal blood.

Furthermore, all other methods and active ingredients that increase the oxygen uptake capacity are also prohibited. A borderline case is the training in vacuum chambers, as it was carried out in the GDR in the 1960s and 70s due to travel restrictions. The negative pressure creates an effect similar to that in the high altitude training camp. A modification of this method are the so-called "Norwegian houses". These are houses that can be completely airtight (and pressurized). Many Scandinavian endurance athletes, such as cross-country skiers, used this method in the 1980s and 90s.

Gene doping

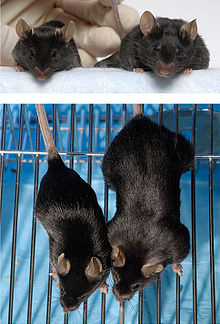

for myostatin was switched off in the right mouse . Myostatin inhibits muscle growth. Due to the lack of myostatin, the muscle mass of the transgenic right mouse is four times higher than that of the wild type (left)

The ban on gene doping means that any use of cells , genes and their components is prohibited, provided that they can increase athletic performance.

Active ingredients that are subject to certain restrictions

This third large group of doping includes, for example, alcohol and cannabis . All international sports federations have agreed that both alcohol and cannabis tests may be carried out and that positive results can result in sanctions . Furthermore, local anesthetics are only allowed if they do not contain cocaine as an active ingredient and if a medical examination confirms the need. However, written notification of the diagnosis , the dose and the route of administration is required.

The use of corticosteroids is also only permitted to a limited extent. Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory drugs . Local application of the anti-inflammatory drugs to the skin, ears, eyes and joints as well as inhalation are permitted. If treatment with this active ingredient is carried out during competitions, written notification to the competition management is required.

Beta blockers are active ingredients that are only permitted to a limited extent. They prevent nervousness and have a calming effect on the heart and circulation . Beta blockers are therefore prohibited in sports in which rest and concentration play an important role. The athlete himself has the task of checking whether any of these restricted active substances are banned in his sport or his country.

Risks

Damage from doping

The risks that the athlete takes when he ingests doping substances are great and can be divided into four groups: firstly, the risk of being convicted of doping use, secondly, that the doping agent may harm the body, thirdly, the risks go hand in hand with a performance that is higher than the natural level, and fourthly, that the doping agent leads to a weakening.

Doping tests found in competitive sports often take place. They are either carried out unannounced during training or immediately after a competition . If an athlete is proven that he has illegally increased his performance, he loses the right to participate in competitions for two years. Since almost all professional athletes are dependent on sponsors and prize money , there is no longer any possibility for them to earn money with the sport during this period. So far, the ordinary courts have refused to deal with the question of the ban on competitions, i.e. that of a professional ban. This is an internal matter of sport. Furthermore, such a pre-stressed athlete is unlikely to get good sponsorship contracts again.

However, there is a much greater risk that the athlete will damage his body in the long term by taking doping substances. Any drug that is used illegally to improve performance, like any other drug , has side effects . In addition, in sport, a multiple higher dose of a preparation must be used to increase performance than with medical use. This increases the side effects to the same extent. The range of use e.g. B. of anabolic steroids is very large and ranges from 50% of the therapeutic amount in long-stretchers to 50 times the therapeutic amount in bodybuilders and weightlifters. Some of this damage is irreparable. In the case of injected products, there are also the risks that are solely caused by this form of administration.

Often, however, this risk is not due to the side effects of preparations, but rather the consequence of the effect achieved. For example, the cardiovascular problems of very heavy bodybuilders are the same as those of very obese people of comparable body weight. The mere increase in body mass above the natural level is on the one hand the desired effect, on the other hand it is also a decisive factor for increased stress on the circulatory system. Chronically high blood pressure also damages all organs, especially the kidneys . In competitive sports, the existing risks are simply increased by the increased performance. Running at a higher speed or over a longer distance is more stressful, and both the risk and severity of injuries increases when movements are carried out more explosively or greater loads are mastered.

This means that at the end of their career the athlete accepts a partially destroyed body and some of the impairments caused by the side effects may persist until the end of their life or can lead to serious consequential damage to health even years later.

However, given the dangerousness of doping, it should not be overlooked that there are few proven doping deaths. An exception is bodybuilding , in which a high number of doping-related deaths has been scientifically documented in both the professional and amateur sectors. Otherwise one refers to a large number of unreported cases, but without being able to prove this. Leading doctors, especially from Great Britain, point out that the greatest risk for public health lies in the rigorous prosecution of doping cases in top-class sport by the respective NADA and WADA. This would drive the use of doping substances in recreational sports underground, which increases the health risks of 1,000 times as many people compared to the number of controlled members of the cadre. Serious medical care for recreational athletes who are doping and research in the field of doping damage is not given due to the criminalization of the use of doping substances.

Deaths

- On July 23, 1896 Arthur Linton fell dead from his bike more than 600 kilometers on the long-distance Bordeaux – Paris trip. The Englishman had used stimulants to push his performance limits so far that his organism could no longer withstand the strain. However, other sources point out that Linton did not die of typhoid fever until after the race, although it is believed that the stimulants in his body left him with no defenses.

- 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome: Knud Enemark Jensen died after a heat stroke in a team race (100 km). It later emerged that the entire Danish road cycling team had been doped with amphetamines .

- Tour de France 1967 : Tom Simpson died after taking amphetamine during the stage on Mont Ventoux .

- 1968: Joseph (Jupp) Elze died of severe head injuries after a boxing match against Carlos Duran. The autopsy revealed that his sensation of pain was greatly reduced by stimulants during the fight .

- The athlete Birgit Dressel died on April 10, 1987 after multiple organ failure , most likely as a result of doping.

- On March 14, 1996, top bodybuilder Andreas Münzer died at the age of 31, also due to multiple organ failure as a result of years of massive doping.

Causes of doping

While in the media and in the public debate the responsibility is mostly sought with the individual athlete or his immediate environment, sport sociological research sees doping primarily as a result of competitive sport and thus as a structural problem that is also responsible for society as a whole. It is therefore a complex construct of high expectations of sports viewers with regard to successes, records and sensations, which is picked up and even reinforced by the mass media, the orientation towards the results of state donors and the corresponding political pressure on non-profit sports associations, officials and coaches, as well as the commercial structures of professional sport.

A competitive athlete usually earns his living through national sports funding programs, employment contracts with professional sports clubs, prize awards and sponsorship contracts. Depending on the type of sport and competition, even short phases of failure can have significant negative consequences for the individual athlete, but also for entire clubs and sports associations. The livelihood of a competitive athlete is therefore mostly directly dependent on sporting, even sustained success, which leads to immense pressure to perform. In order to be successful, intensive training is required, but this is not always enough in the top range, especially if there are injuries or (early) signs of wear and tear. The decision to doping, in addition to the intensive training that is still required, is not only based on the individual motivation to want to assert oneself against other athletes or to gain an advantage, but to stick to one's profession and the system of competitive sports in general that many competitive athletes get into as early as their childhood and youth and often cannot develop career alternatives due to the high time and physical effort.

However, doping can also be the result of a purely individual addiction to success. Professional athletes and also many amateurs try to always strive for the highest possible performance. Once an athlete has won victories, he strives to achieve them again and again. In order to be the best, many athletes are willing to take doping substances. The Goldman dilemma known in sports sociology has shown that many competitive athletes are even willing to accept an early death if the use of drugs would guarantee success at the highest level. The sports philosopher Volker Caysa comments on this: “In doping […] a fatal illusion of the dawning biotechnical age […] of being able to arbitrarily make a body what one wants is focused. The massive doping systematically practiced by all sports nations is only an expression of the fact that the traditional ethic of the inviolability of the body is fundamentally refuted by the biotechnological revolution that is only just beginning . "

The doping ban in the dispute of opinion

Position of supporters

In public, doping is almost exclusively portrayed negatively as fraud against fellow athletes and the public. In general, the doping ban is based on three arguments. One is aimed at fair competition. Opponents of doping emphasize that doping fundamentally contradicts fair competition. The other two relate to the protection of athletes and the public.

Protection of athletes

Proponents of the doping ban assume that any form of doping is fundamentally harmful and always causes significantly more damage to the body than a “clean” competitive sport could ever do. That is why the participation of doctors in the procurement and administration of doping substances is always considered a violation of medical ethics . The core task of doctors is to prevent diseases and to treat and cure the sick. The inability to win or break a record in a sporting competition is not a disease. Athletes who routinely used performance enhancers would unlearn to accept the limits of their ability to act. Ambitious athletes would be lacking in humility once they were allowed to manipulate their own physical characteristics through artificial procedures. The ban on doping continues to be justified by the fact that a release of doping would in fact require “clean” athletes to do doping due to increased competitive pressure. Doping athletes do not voluntarily make use of their “ right to self-harm ” in sports in which doping is common . Also, the hope of many amateur athletes that they will be “rewarded” for doping with the chance to become famous, to generate high income and to amass a fortune, is illusory, since only a very small proportion of them rise to the top of their sport.

Protection of the public

According to the proponents of the ban, the role model function of competitive athletes speaks against a public commitment by sport to doping. Particularly with regard to young people, it is feared that lifting the doping ban could send false signals and encourage people to use doping substances who are not aware of the resulting dangers. The community of those with health insurance cannot be expected to finance high costs for long-term damage caused by the side effects of doping. The same applies to side effects such as the need for early retirement.

Position of the opponent

Opponents of a doping ban point out that the release of doping could lead to greater equality of opportunity than today's strict ban. Since the doping ban is obviously hardly enforceable in practice, this means that it is not the most physically capable athletes but the most skilful people who circumvent the ban who are most successful.

Some authors even see the doped athlete as an archetype of self-conscious and free decision-making people who improve according to their own ideas. The pragmatic variant of this thesis consists in the sober indication that the time when it was said: "Being there is everything" is long gone and only success (however brought about) in the sense of a victory, winning championships, the Breaking a record, etc. count. The above "Improvement" is most easily recognized by the development of the account balance of those involved. Moralizing arguments of the proponents of a doping ban are therefore "naive".

Kimura points out that the doping bans and especially the doping controls accompanying training are primarily about the fact that the sports associations wanted to have a power potential in the sense of Michel Foucault over top athletes after the amateurs' regulations (which gave them the arbitrary potential of unwelcome athletes) . This is the only way to ensure that enough of the added value that top athletes generate remains with the officials. The use of Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) (= approval of the use of prohibited substances with medical approval) also has a considerable potential for arbitrariness in the sense of Kimura, since the associations organize the approval. Even if such TUEs are necessary to e.g. B. in senior sports, in which prescription drugs are (must) often used in the interests of quality of life, not to exclude too many athletes, there is still a considerable potential for abuse in the TUEs.

Mediating position

One suggestion made by opponents of a comprehensive doping ban is that decisions about the harmfulness of doping substances should be made on a case-by-case basis and, in the event of a release, the use of the substance or process in question should be subject to medical control. A legalization of relatively harmless means to improve performance should aim from the outset to prevent the unregulated spread of doping substances. Similar to the prescription of “normal” drugs, “the doctor or pharmacist should be asked” who can and must be expected to deal responsibly with the transfer of active ingredients. This would largely remove the basis of the black market that exists today.

Doping prosecution

Doping is prohibited to athletes by the international sports associations (especially the IOC ) as part of their competitions. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was founded in 1999 to combat doping . Officially, this is usually justified with equal opportunities for the competitors, the protection of them from damage to health through doping and a role model function that sport and thus top athletes have to fulfill.

Since a general public image of properly performed services in a sport is of enormous importance for its respective market value, there is also a high economic incentive for associations and organizers to promote this image by successfully creating the impression that effective doping prosecution measures would be taken by them.

In some countries doping or certain doping variants are considered a criminal offense and are prosecuted by state organs with sovereign measures against athletes (and their helpers), for example in France , Spain or Italy . Since 2000, doping offenses against athletes can be punished with a prison sentence of up to three years in Italy. However, no athlete has ever been charged or punished for ingesting prohibited doping substances, and certainly not with a prison sentence. The Spanish Anti-Doping Act prohibits doping controls during training between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m. and only applies to competitive athletes from associations affiliated to the Olympic Committee. This z. B. Bodybuilding not covered.

According to the law currently in force in Germany, athletes do not commit any criminal offense by taking doping substances , as there is a “right to self-harm”. But athletes can also make themselves liable to prosecution if they share doping substances with other athletes. This is because it is forbidden according to Section 2 (3) of the AntiDopG to acquire or possess a doping agent in large quantities for the purpose of doping people in sport or to bring it into the scope of this law. The determination of this not insignificant amount has been found in the doping agent quantity regulation since November 29, 2007 . This offense is punishable by a fine or imprisonment of up to three years in accordance with Section 4, Paragraph 1, No. 3 . Section 95 (3) of the Medicines Act provides for a prison sentence of one to ten years in particularly serious cases (dispensing or using medicinal products for doping purposes in sport to persons under the age of 18).

In the past, however, there have been convictions for crimes of bodily harm, in some cases against those under wards , when preparations were administered by trainers to athletes without their knowledge / consent. Declarations of consent from legal guardians of underage athletes are considered abuse of parental rights . Doping of animals during sporting competitions or in training for it is prohibited in Germany according to § 3 No. 1b Animal Welfare Act and an administrative offense according to § 18 I No. 4 TierSchG, which can be punished with a fine of up to € 25,000 according to § 18 IV . If doctors , veterinarians or pharmacists actively participate in doping practices, their license to practice medicine can be withdrawn from them in Germany because of unworthiness or unreliability , which would mean that they would lack the basis for their professional existence.

Action

Because in many sports different active substances and methods of non-physiological performance enhancement are forbidden, but new methods and new substances are always classified as performance-enhancing, a doping list with precisely listed and described substances and procedures defines what is to be understood by doping in a doping list that is constantly adapted to reality .

This list - drawn up, updated and permanently supplemented with new substances by international sports associations in cooperation with the IOC's medical commission - is adopted by all national associations. Accordingly, there is a doping violation if one of the substances listed in the prohibited list is detected in the body of the athlete , he has refused a doping control , is in possession of substances prohibited in sport or wants to obtain them. A prescription is sufficient as proof of procurement. Each of the approximately 1,500 top athletes in Germany who belong to the individual top-level squads must undertake in writing to their own national association to comply with all doping regulations, to cancel their journeys and to tolerate controls at all times.

When detecting illegal substances, a distinction is made between competition and training controls. Competition controls are necessary to prove the short-term increase in performance through doping, which was carried out shortly before the start of the competition. Training controls try to prove a long-term use of doping and to track down substances that can no longer be detected in competition controls due to a timely withdrawal. These controls consist of a urine sample and a blood sample - voluntary in Germany .

The biological passport program is a new type of detection method for doping and is intended to supplement the classic detection methods for prohibited substances or methods. In this indirect detection method, the results of urine and blood samples from training and competition controls are combined to form a biological profile of the athlete. Values that represent a deviation from the expected profile should not provide direct evidence of how manipulated - which substance, which method - was, but indirect evidence that it was manipulated.

When taking prohibited stimulants or painkillers for the first time , a warning is issued. For all other offenses, such as the use of anabolic steroids or the manipulation of a doping sample, the athlete will be banned from competition (see also disqualification ) for at least two years. Furthermore, in the case of doping offenses that take place during a competition, the performances are canceled.

Manipulation of doping samples

Since more and more doping samples were manipulated, the manipulation itself is now viewed and described as a doping offense. Any manipulation is expressly prohibited, as these values are essential for the proof of doping. This includes exchanging or changing the samples, diluting them with any liquid, injecting foreign urine into the bladder, influencing urine excretion with chemical substances and influencing the ratio of testosterone to epitestosterone .

Last but not least, the BALCO affair in the United States with the development of new, unknown doping substances that could not be proven has shown that certain circles have an interest in permanent performance improvement in sport, because this can be marketed well.

Trainers and officials have warned athletes against controls. Certain events are well attended because it is known that there is no control. In paid football, the shirt numbers of certain doped athletes cannot be drawn because they are replaced by others.

Situation in Germany

According to the figures from the National Anti-Doping Agency (NADA) for 2011, a total of 7767 training controls (urine samples 6530, blood samples 1237) and 5087 competition controls were carried out in Germany. In 2011, as part of 86 doping controls, proceedings were initiated for possible anti-doping rule violations. Critics note that the financial outlay for this low rate is disproportionate and seems to be justified solely by the very high media interest.

As part of the training controls, around 8,650 squad athletes can be tested, divided into three test pools and taking part in national and international competitions. All other members of the German Olympic Sports Confederation who also take part in competitions are not checked. But especially in the levels below top-class sport, the doping mentality - in the knowledge that there are no controls - is very pronounced. However, this is negated by the sports management, although there are sound studies, for example of anabolic steroids in Germany and the USA. Sport is a reflection of society. As early as the 1990s, Klaus Hurrelmann found that around ten percent of young people up to the age of 16 regularly use stimulants and other doping substances as well as drugs. However, doping, although not a criminal offense, has a very negative connotation in public.

On December 10, 2015, the anti-doping law was passed. Top athletes who are recorded in one of the test pools of the National Anti-Doping Agency, and athletes who generate significant income from sport, should be punished with up to three years in prison if they can prove self-doping. Doping doctors and other backers could be punished even more severely than athletes. Anyone who "endangers the health of a large number of people" faces a prison sentence of up to ten years. The same applies if doping risks serious damage to health or even the death of the athlete. If the victim is a minor, this has an aggravating effect.

Spectacular doping cases

Individuals

- The controversial doping case Dieter Baumann from 1999, which was banned by the IAAF for three years, although he was nationally acquitted of doping allegations.

- The also extremely controversial case of Alexander Leipold , who was stripped of the gold medal in Sydney in 2000 , although, on the one hand, fluctuations in the amount of urine in the sample in the order of 35 ml suggested subsequent manipulation and, on the other hand, it was proven that the substance discovered at Leipold ( nandrolone ) in the concentration found (one thousandth of a tablet) could not have had any performance-enhancing effect and Leipold's body could have produced it in a completely natural way.

groups

- In the course of the Balco affair , several sports professionals were convicted of doping in the USA: the most prominent representative was sprinter Marion Jones , who was subsequently deprived of five Olympic medals as well as her partner Tim Montgomery, his world record in the 100-meter run. Otherwise, only baseball player Jason Grimsley was banned without a positive test , although the company's customer lists also included numerous other athletes, from sprinting to middle-distance running, basketball, boxing, hammer throwing and the shot put to football. Judoka were also suspected.

sports

Cycling

- Festina affair at the 1998 Tour de France

- Fuentes doping scandal : In the course of investigations, house searches and investigations by the Spanish police, Jan Ullrich , Ivan Basso , Francisco Mancebo and Óscar Sevilla were excluded from suspected doping or suspended from their teams prior to the Tour de France 2006 .

- The 2006 Tour de France winner , Floyd Landis from the Phonak cycling team , tested positive for testosterone. In September 2007, he was found guilty by an arbitration tribunal of the United States Anti-Doping Agency , whereupon the international cycling federation UCI for the first time revoked the Tour de France victory and suspended Landis for two years. The judgment was finally confirmed by CAS on June 30, 2008.

- The cyclist Bert Dietz admitted on 21 May 2007 to have doped in his career and joined other drivers of his former teams explicitly with one.

- The cyclists Christian Henn (May 22, 2007), Udo Bölts (May 23, 2007), Rolf Aldag (May 24, 2007), Erik Zabel (May 24, 2007) and Bjarne Riis (May 25, 2007) - former teammates of Bert Dietz at Team Telekom - confessed to having also doped with EPO. Erik Zabel is the first still active, unconfirmed driver who has confessed to doping in this context.

- On July 2, 2007, cyclist Jörg Jaksche confessed in an interview with Der Spiegel that he had already started EPO doping in 1997 and had used autologous blood doping since 2005. Jaksche is the first driver involved in the Fuentes doping scandal to report in detail about his involvement. He also accuses the current team boss of Team Milram , Gianluigi Stanga , the current team boss of Team CSC , Bjarne Riis, and Walter Godefroot , former head of Team Telekom , of complicity in the doping of their teams.

- Alexander Vinokurow was proven during his victory on the 13th stage of the Tour de France 2007 on July 21st, foreign blood doping. His Astana team ended the tour, as did the Cofidis team and overall leader Michael Rasmussen , who was excluded from his team because he had specified wrong training locations, allegedly to evade doping tests. The winner is Alberto Contador, a driver whose name appeared on a customer list of the doping doctor Fuentes, from whom he was later deleted for unexplained reasons.

- The American Lance Armstrong won the Tour de France seven times between 1999 and 2005 . Because of doping, which he later admitted himself, all titles and an Olympic bronze medal he won in 2000 were stripped of him in 2012 and he was banned for life.

Triathlon

However, the extent of doping in triathlon was always considered to be inconsistent with the z. B. viewed comparable in cycling: Triathlon is also characterized by individualists in the professional area - compared to cycling with its professional team structures. In addition, the income of professional triathletes is far below that of professional athletes in other sports.

In 2004, NADA carried out 101 training and 80 competition controls, during which a positive test ( testosterone ) occurred. In 21 of the training controls, tests were carried out for Epo in the urine.

For comparison: In 2004, 88 training controls were carried out on footballers from clubs of the German Football Association , which has a total of around 7 million members, 656 in 2014. In 2013, the German Athletics Association was almost sixteen times higher Number of athletes is the only German sports association in whose area more doping controls were carried out than in triathlon.

Soccer

The most extensive and court-confirmed case of systematic doping in football is known from Italy. The then manager of Juventus Turin, Antonio Giraudo, as well as the club doctor Ricardo Agricola and the pharmacist Giovanni Rossato were found guilty of having practiced systematic team doping in the 1990s. In the second instance, Agricola was acquitted of the charge of blood doping. There are numerous similar reports from other European countries, but due to a lack of solid evidence and a reluctance to come to terms with them, for the most part they remained without consequences. As early as the late 1970s, there were individual players, including Franz Beckenbauer, who reported about blood transfusions.

In 1993, the team from Olympique Marseille is said to have been collectively doped before the final of the national champions' cup against AC Milan. Only Rudi Völler, who was playing in Marseille at the time, is said to have resisted. The Argentine playmaker Diego Maradona caused one of the best-known individual doping cases in football at the 1994 World Cup when an ephedrine-containing drug was detected in him during the tournament. In the same year a book by the former competitive athlete Edwin Klein was published under the title "Red Card for the DFB", in which various witnesses reported on numerous doping offenses in German football.

In the course of the Spanish doping scandal in 2006, which mainly revolved around cycling , it became known that soccer players were among the customers of doping doctor Eufemiano Fuentes . Reports from the French newspaper Le Monde on Fuentes' collaboration with four top Spanish clubs, including Real Madrid and FC Barcelona , were the subject of several litigation, some of which are still ongoing.

In 1987 Harald (Toni) Schumacher published his book “Anpfiff. Revelations about German football ”, in which he describes how the German national team was doped during the 1986 World Cup.

In 2007 there was a wave of statements from former German players and coaches regarding the years of abuse of Captagon , ephedrine and other substances.

In the spring of 2015 in Freiburg, the results of an investigative commission chaired by Letizia Paoli, which had been published in advance, raised the issue of the former German sports physicians Armin Klümper and Josef Keul, as well as systematic doping in German football and many other sports.

| Surname | society | Finding | punishment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Möller | Eintracht Braunschweig | positive for psychostimulants Prolintan and Etilefrin | no sanctions because Braunschweig lost the game | |

| Roland Wohlfarth | VfL Bochum | positive to norephedrine | two months ban | |

| Holger Gehrke | MSV Duisburg | positive for phenylephrine | no proceedings initiated; Gehrke was not used | |

| Thomas Ernst | VfL Bochum | Taking a circulatory stabilizing substance | 80,000 DM fine for VfL Bochum | |

| Petr Kouba | 1. FC Kaiserslautern | positive for the anabolic steroid Clostebol | four weeks suspension | |

| Thomas Ziemer | 1. FC Nuremberg | positive on anabolic steroids | nine months ban | |

| Quido Lanzaat | Borussia Monchengladbach | positive for THC | eight weeks suspension; Denial of the Indoor Masters title for Mönchengladbach | |

| Manuel Cornelius | TeBe Berlin | positive for nandrolone | Acquittal as victim of a contaminated dietary supplement | |

| Ibrahim Tanko | Borussia Dortmund | positive for THC | four months suspension, 15,000 DM fine | |

| Raymond Kalla | VfL Bochum | Taking triamcinolone | three game lock | |

| Daniel Gomez | Alemannia Aachen | positive for the cortisone preparation methylprednisolone | twelve games suspension | |

| Kay-Uwe Jendrossek | FC Erzgebirge Aue | Use of a product containing cortisone | six game suspension | |

| Marko Rehmer | Hertha BSC | Taking the steroid betamethasone | nine games suspension | |

| Senad Tiganj | FC Rot-Weiß Erfurt | positive to fenoterol | ten weeks suspension; Conversion of the game score into a 2-0 defeat of Erfurt against Unterhaching | |

| Falk Schindler | Kickers Emden | positive to finasteride | six months ban; Conversion of the game standings into a 2-0 defeat by Emden against Düsseldorf | |

| Nemanja Vucicevic | TSV 1860 Munich | positive to finasteride | six months ban | |

| Marc Lerandy | SC Pfullendorf | positive for reproterol | six game suspension | |

| Oliver Kahn | FC Bayern Munich | Tantrum at the check, possibly also a late check | one game suspension in the UEFA Champions League and a fine of 12,339 euros | |

| Christoph Janker and Andreas Ibertsberger | TSG 1899 Hoffenheim | appeared late for the doping test | 75,000 euros fine for 1899 Hoffenheim | |

| Tobias Francisco | SV Babelsberg 03 | positive testosterone / epitestosterone sample | two year ban | |

| Sources: Article in Welt Online and n-tv.de | ||||

Weightlifting

- At the 2006 World Weightlifting Championships, the entire Indian team and 45 other athletes were suspended.

athletics

- Disqualification of the Olympic champion and world record holder in the 100 meter run , Ben Johnson (Canada) at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul

- 1992 Doping suspicion or drug abuse by Katrin Krabbe , Grit Breuer , Manuela Derr and their trainer Thomas Springstein .

- The US sprint star, world record holder and Olympic champion Justin Gatlin was convicted of doping in July 2006.

rugby

- In the spring of 2015, Pierre Ballester , author of Lance Armstrong's 2005 book LA Confidential about doping , published a new work revealing the widespread use of doping in the third most popular sport in France, rugby .

Winter sports

- Disqualification of the third place in the 5 km cross-country skiing Galina Kulakowa ( Olympic champion of Sapporo 1972 over 5 km, 10 km and in the relay) at the 1976 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck because of the use of a cold spray containing ephedrine . It was not banned by the FIS or the IOC and achieved bronze and gold in the relay in the 10 km individual race.

- Disqualification of the three-time gold medal winner Johann Mühlegg at the 2002 Winter Olympics

Sporting occasions

- At the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, ten weightlifters were convicted of doping, among them the two-time Greek silver medalist Leonidas Sampanis , who was stripped of his bronze medal in front of a home crowd. The also Greek sprinters and Olympic medal winners from Sydney Ekaterini Thanou and Konstantinos Kenteris evaded a doping control due to a simulated accident and did not take part in their competitions.

- In 2007, 15 Austrian biathletes, supervisors and officials were banned from the Olympic Games for possession of doping substances during the 2006 Winter Olympics, some for life. The ÖOC was fined one million US dollars.

- In December 2014, based on information from the whistleblower and athlete Yulia Stepanova and her husband Vitali, ARD - Documentation Secret Matter Doping - How Russia Makes Its Winners - researched nationwide and systematic doping in Russia in the run-up to the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi with connections to the Head of the IAAF World Athletics Federation .

In response to the research, WADA set up a commission of inquiry. The result of the investigation, published a few weeks before the 2016 Summer Olympics, became known as the McLaren Report . The Russian Athletics Federation initially considered legal action, and at the beginning of February 2015, its incumbent President Valentin Balachnitschew resigned. In November 2015, the All-Russia Athletics Federation (ARAF) was temporarily suspended by the IAAF Council. The association is therefore not allowed to send athletes to international competitions until further notice and there is a threat of Russian athletes being excluded from the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro .

Prohibited technical aids

E-doping in chess

E-doping is a catchphrase used to describe the unauthorized use of computers to improve performance, especially in chess . In contrast to doping, which aims to increase the athlete's physical and / or mental performance, the unauthorized use of electronic aids does not affect the athlete's performance; rather, it is a simple rule violation in the sense of unsportsmanlike conduct. Since there are obviously no physical risks for the athletes, the use of such aids is permitted in certain disciplines of chess, especially correspondence chess .

Since chess computers or so-called "engines" are far superior even to human world champions due to their greater computational depth, the problem of manipulating chess games by using electronic aids has arisen. This problem has become even worse due to the massive spread of smartphones on which the corresponding engines can be installed. While cases of fraud were initially known in which helpers in the tournament hall were in contact by SMS with a third party who analyzed positions on a powerful computer and worked out move suggestions (e.g. in the case of Sébastien Feller ), cases with increasing performance of smartphones became known in which the players sought unauthorized assistance even while they were in the toilet (e.g. in the case of Christoph N.)

According to No. 11.3.2.1 of the FIDE Chess Rules, chess players are generally not allowed to keep any electronic devices at the venue that have not been expressly approved by the referee beforehand. The rules provide that the tournament organizer can determine in the tournament rules that electronic devices may be kept in a completely switched-off state in a bag that is kept in a location approved by the referee and that a player can only access with the referee's permission. In the event of a violation, FIDE rules provide for the loss of the lot, whereby the organizer can determine less serious measures. This does not affect disciplinary measures by the chess associations involved.

Motor doping

At the Cyclocross World Championships in 2016 , the 19-year-old Belgian Femke Van Den Driessche was proven to have had a racing bike with a hidden engine ready. She was stripped of her U23 European and national champion titles by the World Cycling Association . It was fined CHF 20,000 and banned until October 10, 2021, i.e. for six seasons. Even before the UCI's verdict was announced on April 26, 2016, she announced her resignation. A mini-motor, batteries in the seat tube and a bluetooth trigger were found in one of her bikes.

Media reported alleged motor doping by seven professional cyclists at two cycling races in Italy and urged the UCI to do more effective controls. So far, UCI has been using inexpensive magnetic resonance devices that - about the size of a tablet - are guided along the wheel frame. As an alternative, it is required to use thermal imaging cameras to film the wheels while driving, whereby (in addition to waste heat from bearing friction, frame wear) the waste heat from the battery or motor should be visible.

Industry experts suspect seven - not known by name - participating professional cyclists of the Strade Bianche cycling race in Italy in 2016 of motor doping.

Animal doping

Doping is not only known in humans, but is also used where animals are to be reached by humans or for him sporting success: for example, in the equestrian sport in horse racing or greyhound racing . In Germany, doping on animals is permitted at competitions or similar events in accordance with Section 3 of the Animal Welfare Act is prohibited, and the dog and equestrian associations also take measures against doping.

See also

- Chaperone (sport)

- Heidi Warrior Medal

- State plan topic 14.25 of the GDR

- Forced doping

- Anthropomaximology

literature

- Mischa Kläber: doping in the gym. The addiction to the perfect body. transcript, Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-8376-1611-8 .

- Nicole Arndt, Andreas Singler, Gerhard Treutlein (eds.): Sport without doping! Arguments and decision-making aids for young athletes and those responsible in their environment. German Sports Youth, 2004, ISBN 3-89152-485-4 .

- Christoph Asmuth (Ed.): What is doping? Facts and problems of the current discussion. (= Focus on doping. 1). transcript, Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-8376-1444-2 .

- Brigitte Berendonk : Doping Documents - From Research to Fraud. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-540-53742-2 .

- Karl-Heinrich Bette , Uwe Schimank: Doping in high-performance sport . 2., ext. Edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-518-11957-5 .

- Karl-Heinrich Bette, Uwe Schimank: The doping trap 2., Erw. Edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2006.

- Klaus Blume: The doping republic. A (German-) German sports history . Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86789-161-5 .

- Bettina Bräutigam, Michael Sauer: DOPING dimensions and drug abuse; Fields of action for prevention. Regional Association Westphalia-Lippe, 2004. (www.lwl.org)

- Dirk Clasing (Ed.): Doping and its active ingredients - Prohibited drugs in sport . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Spitta Verlag, Balingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-938509-90-6 .

- Dirk Clasing, Rudhard, Klaus Müller: Doping control - information for active people, supervisors and doctors to combat drug abuse in sport. 4th edition. Sport and Book Strauss, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-89001-134-9 .

- Karl Feiden , Helga Blasius: Doping in sport: who - with what - why . Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8047-2440-2 .

- Michael Gamper, Jan Mühlethaler, Felix Reidhaar (eds.): Doping; Top sport as a social problem . NZZ Verlag, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-85823-858-9 .

- Wolfgang Jelkmann: Blood doping - myth and reality. In: Ch. Knust, D. Groß (Ed.): Blood. The power of the very special juice in medicine, literature, history and culture. kassel university press, Kassel, 2010, pp. 101–109. (Abstract on: uni-kassel.de )

- Wolfgang Knörzer, Giselher Spitzer , Gerhard Treutlein (eds.): Doping prevention in Europe. First international expert discussion 2005 in Heidelberg . Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 2006, ISBN 3-89899-196-2 .

- Martin Krauss : Doping. Rotbuch-Verlag , Hamburg 2000.

- Arnd Krüger : The paradoxes of doping - an overview. In: M. Gamper, J. Mühlethaler, F. Reidhaar (eds.): Doping - top sport as a social problem. NZZ Verlag, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-85823-858-9 , pp. 11–33.

- Arnd Krüger: Basics of doping prophylaxis. In: Rico Kauerhof, Sven Nagel, Mirko Zebisch (eds.): Doping and violence prevention. (= Series of publications by the Institute for German and International Sports Law. Volume 1). Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2008, ISBN 978-3-86583-300-6 , pp. 143–166.

- Ralf Meutgens (Ed.): Doping in cycling . Delius-Klasing Verlag, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-7688-5245-6 .

- Arno Müller: Doping - Sport - Ethics: Teaching materials for discussion. In: Sport-Praxis - The trade journal for sports teachers and trainers. Vol. 48 (2007), No. 5, ISSN 0176-5906 , pp. 4-9.

- Rudhard Kl. Müller: Doping. CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-50845-6 .

- Carl Müller-Platz, Carsten Boos, R. Klaus Müller: Doping in recreational and popular sports. (= Federal health reporting. Issue 43). Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89606-174-7 .

- Eckart Roloff and Karin Henke-Wendt: Doping West, Doping East - sports medicine professionals and their unsportsmanlike competition in cheating. In: dies .: Damaged instead of healed. Major German medical and pharmaceutical scandals. Hirzel, Stuttgart 2018, pp. 65–75, ISBN 978-3-7776-2763-2 .

- Juana Schmidt: Doping as reflected in Swiss criminal law - perspectives for an anti-doping offense. In: Journal for Sport and Law. (SpuRt) 2006, Issue 1 and 2, CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISSN 0945-3873 , pp. 19–24 and 63–67.

- Wilhelm Schänzer , Mario Thevis: Doping and doping analysis: active ingredients and methods. In: Chemistry in Our Time. 38 (4) (2004), ISSN 0009-2851 , pp. 230-241.

- Katja Senkel: Play True. The doping problem between sport ethical requirements and general legal entitlement . (= Olympic Studies. Volume 7). Agon Sportverlag, Kassel 2005, ISBN 3-89784-997-6 .

- Andreas Singler, Gerhard Treutlein: Joseph Keul: Scientific culture, doping and research on pharmacological performance enhancement. Scientific report on behalf of the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg. Mainz: 2015. Access under: Website Andreas Singler .

- Andreas Singler: Doping at the Telekom / T-Mobile team. Scientific report on systematic manipulations in professional cycling with the support of Freiburg sports medicine specialists. On behalf of the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg. Mainz: 2015. Access under: Website Andreas Singler .

- Andreas Singler, Gerhard Treutlein: Herbert Reindell as radiologist, cardiologist and sports medicine specialist: Scientific focus, involvement in sport and attitudes to the doping problem. Scientific report on behalf of the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg. Mainz 2014. Accessed at: Website Andreas Singler. [1]

- Andreas Singler: Doping prevention - aspiration and reality. Aachen: Shaker 2011.

- Andreas Singler: Doping and Enhancement. Interdisciplinary studies on the pathology of social performance orientation. Göttingen: Cuvillier Verlag 2012 (Würzburg Contributions to Sports Science Volume 6).

- Andreas Singler, Gerhard Treutlein: Doping in top-class sport. Sports science analyzes of national and international performance development . exp. 3. Edition. Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 2006, ISBN 3-89899-192-X .

- Andreas Singler, Gerhard Treutlein: Doping - from analysis to prevention. Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 2001, ISBN 3-89124-665-X .

- Norman Schöffel, David A. Groneberg, Henryk Thielemann, Axel Ekkernkamp: Black Book Doping. Methods, means, machinations . Medical Scientific Publishing Company, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-95466-135-0 .

- Ludwig V. Geiger: Art of Movement. This is how the body works. Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, Rosenheim 2014, ISBN 978-3-475-54329-6 , pp. 76, 91 f., 245 f., 259, 262 f., 270 f., 394 f., 398, 402 ff.

- youth book

- Florian Buschendorff: I want more muscles - no matter how! - Youth novel on the subject of doping, bodybuilding and body cult (14-16 years). Verlag an der Ruhr, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8346-0405-7 .

- Deutsche Sportjugend (Ed. - Authors Gerhard Treutlein and others): Sport without doping! Working media kit for doping prevention. Frankfurt am Main 2006/2008.

- Deutsche Sportjugend (Ed. - Authors: Gerhard Treutlein / Patrick Magaloff): Sport without doping! Information on anti-doping rules for competitive athletes. Frankfurt am Main 2009.

Web links

- NADA - National Anti-Doping Agency - current doping list, list of permitted drugs, etc.

- WADA - World Anti-Doping Agency (in English and French) WADC information

- Antidoping Switzerland , information platform for the fight against doping Switzerland: current doping list, effects and side effects of doping, control procedures etc.

- Doping-Info.net , definition, effect, substances and control

- Release doping! - Matthias Heitmann in NOVO, September 2007

- German Sport University Cologne , side effects of doping substances

- Kurt A. Moosburger: Doping - An overview of the present and an outlook into the future. A brief explanation of doping substances and methods. (PDF file; 155 kB)

- Translating Doping , scientific project of the BMBF for the inter- and transdisciplinary knowledge transformation of the doping issue

- Doping at work to cope with stress , interview with specialist Götz Mundle

- Doping research / doping at the University Clinic Freiburg: Andreas-Singler.de

- Professional Association of Legal Journalists eV (undated): Doping - With all means to victory ( Memento from March 10, 2018 in the Internet Archive ). A thematically broad and informative overview article on the subject of doping with information on various doping agents, a chronicle of doping and the fight against doping. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ dpa , Michael Brendler: Doping in the job is increasing , Badische-zeitung.de , March 18, 2015

- ↑ Jacob Bucher: soldiering with Substance: Substance and steroid use among Military Personnel. In: Journal of Drug Education. 42 (2012), 3, pp. 267-292. see. America's chemically modified 21st century soldiers , Clayton Dach, AlterNet , May 2, 2008

- ↑ M. Verroken: Drug use and abuse in sport. In: Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 14, 2000, pp. 1-23. PMID 10932807 .

- ↑ Adrian Lobe: Mechanical doping: Is cycling threatened with the next fraud scandal? . welt.de. April 1, 2015

- ↑ Rachel Metz: Five Ways to Become a Cyborg . Technology Review. heise.de. 17th July 2018

- ↑ Andreas Menn: On the way to the cyborg - why people optimize themselves . wiwo.de. January 13, 2018

- ↑ wada-ama.org (PDF).

- ↑ Andreas Singler: Doping Prevention - Claim and Reality. Aachen: Shaker 2011.

- ↑ Patrick Laure: The prevention of doping mentality: the way through the education . In: Fritz Dannenmann, Ralf Meutgens, Andreas Singler (eds.): Sports education as a humanistic challenge. Festschrift for the 70th birthday of Prof. Dr. Gerhard Treutlein. Aachen: Shaker 2011, pp. 276–287.

- ^ District professional court for doctors in Freiburg: Judgment on behalf of the people in the professional court case of Prof. Dr. med. Armin Klümper [...] because of unworthy professional behavior. Freiburg (announced on September 16, 1992) .

- ^ Joachim Linck: Doping and state law. In: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift, 41/1987, pp. 2545-2551.

- ↑ Juan Manuel García Manso: La fuerza. Ed. Gymnos, Madrid 2002, ISBN 84-8013-215-9 .

- ↑ Luitpold Kistler: Deaths from anabolic steroids abuse - cause of death, findings and forensic aspects. Dissertation. Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich 2006, p. 13 ff.

- ↑ Bengt Kayser, Alexandre Mauron, Andy Miah: Current anti-doping policy: a critical appraisal. In: BMC medical ethics. 8 (2007), pp. 2–2.

- ^ Karl-Heinrich Bette, Uwe Schimank: Doping: the unleashed competitive sport. Federal Agency for Civic Education.

- ↑ The research: doping in hobby cycling (July 24, 2017)

- ↑ Volker Caysa: body utopias. A Philosophical Anthropology of Sport. Campus Verlag 2003, p. 236

- ↑ See e.g. B. Lars Figura : The everyday suspicion . In: taz. May 7, 2009.

- ↑ Central Ethics Commission of the Federal Medical Association: Statement of the Central Commission on the protection of ethical principles in medicine and its border areas (Central Ethics Commission) at the Federal Medical Association on doping and medical ethics ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) February 2009.

- ↑ Michael J. Sandel: The Case against Perfection. In: The Atlantic Monthly. 2004.

- ↑ Savulescu et al. a .: Why We Should Allow Performance Enhancing Drugs in Sport. In: Br. J. Sports Med. 2004; 38, pp. 666-667.

- ↑ Machiko Kimura: The genealogy of power. Historical and philosophical considerations about doping. In: International Journal of Sport & Health Science. 1 (2), (2003), pp. 222-228. near.nara-edu.ac.jp ( Memento from March 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF).

- ↑ cf. Arnd Krüger : Olympic Games as a means of politics. In: Eike Emrich, Martin-Peter Büch, Werner Pitsch (eds.): Olympic Games - still up to date? Values, goals, reality from a multidisciplinary perspective. Universitätsverlag des Saarlandes, Saarbrücken 2013, ISBN 978-3-86223-108-9 , pp. 35–54, especially p. 46 f. universaar.uni-saarland.de (PDF).

- ↑ BOLETIN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO. Núm. 148 Viernes 21 de junio de 2013 Sec. I. Pág. 46652.

- ↑ Medical ethics and doping abuse (PDF) In: Platform Sports Law. Issue 1/2011, pp. 15-18.

- ^ Edwin Klein: Red card for the DFB. ISBN 3-426-26732-2 .

- ↑ Federal Ministry of the Interior: Draft of the anti-doping law presented

- ↑ Three years imprisonment for doped athletes . In: The time. November 11, 2014.

- ^ Doping sinner: Floyd Landis loses Tourieg 2006. spiegel.de, June 30, 2008, accessed on January 10, 2016 .

- ^ Arbitral Award. (PDF) tas.cas.org, June 30, 2008, archived from the original on July 15, 2009 ; accessed on January 10, 2016 .

- ↑ Cycling versus triathlon: cultural disconnect . In: slowtwitch.com . Archived from the original on February 11, 2016.

- ↑ NADA annual report 2004 . In: National Anti-Doping Agency Germany .

- ↑ Oliver Kubanek: DTU front runner in number of doping controls . In: German Triathlon Union . April 2, 2014.

- ↑ Sentenza n. 21234 Corte Suprema di Cassazione (PDF) pp. 40-42, March 30, 2007 (Italian).

- ^ Thomas Kistner: Injection sport soccer. Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin , accessed on December 2, 2010 .

- ↑ Völler teammate raises serious doping allegations. Spiegel Online , accessed December 2, 2010 .

- ↑ Edwin Klein: The doped league. Focus , accessed December 2, 2010 .

- ^ ARD radio feature: Doping in football ( Memento from April 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), NDR 2010.

- ↑ Jörg Schallenberg: The wall is starting to crumble. Spiegel Online June 16, 2007.

- ^ The Dopingakte Freiburg , Badische-zeitung.de

- ↑ Prolintan - Möller was doped. In: Focus Online . February 18, 1994, accessed April 9, 2013 .

- ↑ 16 doping cases in German football. Welt Online , June 13, 2007, accessed August 15, 2011 .

- ^ Doping cases in German football. n-tv , accessed August 15, 2011 .

- ^ Hans Woller : Doping apparently widespread in rugby , Deutschlandfunk.de , March 8, 2015.

- ↑ No lifting of the lifelong ban: court rejects objections by cross-country skiers , news.at

- ↑ spiegel.de: Doping in winter sports - exclusion for Austrians, ban for cross-country skiers

- ^ Matthias Friebe: Whistleblowers express themselves again , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Clemens Prokop in conversation with Matthias Friebe: "A nightmare for sport" , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 6, 2014.

- ^ Andrea Schältke: Russian results in Sotschi doubtful , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 6, 2014.

- ↑ Jessica Sturmberg: Systematic and area-wide doping , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 3, 2014

- ^ Hajo Seppelt in conversation with Bastian Rudde: "An industrial production of top athletes" , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 7, 2014

- ↑ Hajo Seppelt in conversation with Astrid Rawohl: "Sport does not want to solve the doping problem at all" , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 13, 2014.

- ↑ Jessica Sturmberg: Entanglement of the IAAF top , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 7, 2014.

- ↑ Victoria Reith: Russian Association is considering lawsuit , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 6, 2014

- ↑ Hajo Seppelt in conversation with Matthias Friebeh: " Little has happened in the background" , Deutschlandfunk.de, December 6, 2014.

- ↑ Doping scandal: Russia's Athletics Association suspended at zeit.de, November 14, 2015, accessed on November 14, 2015.

- ^ New York Times, June 12, 2011: Disqualified by Evidence on a Phone

- ↑ FIDE: Laws of Chess, 2017

- ↑ Six years ban for engine doping: Belgian woman draconian sanctioned by UCI , orf.at, April 26, 2016, accessed on April 26, 2016.

- ↑ Suspected fraud in two races in Italy , orf.at, April 19, 2016, accessed on April 19, 2016.

- ↑ Six years ban for motor doping: Belgian woman draconian sanctioned by UCI , orf.at, April 26, 2016, accessed on April 26, 2016.

- ↑ FCI , International Guidelines about Dog Doping ( Memento from September 24, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), fci.be from July 2009 (PDF; 87 kB, English).

- ↑ Guidelines of the Working Group on Animal Welfare and Equestrian Sport - IV. Doping. ( Memento from May 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) bmelv.de