ETA Hoffmann

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (* 24. January 1776 in Königsberg / East Prussia ; † 25. June 1822 in Berlin ; name actually Ernst Theodor Wilhelm , in 1805 renamed based on the he admired Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart ) was a German writer of romance . He also worked as a lawyer , composer , conductor , music critic , draftsman and caricaturist .

Life

Origin and youth

Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann was born on January 24, 1776 in Königsberg as the youngest son of court attorney Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann (1736–1797) and his cousin Lovisa Albertina Doerffer (1748–1796, marriage 1767) and, like his two older brothers, was baptized Evangelical Lutheran . When his parents separated in 1778, his brother Johann Ludwig (1768 until after 1822) stayed with his father, who moved to Insterburg , and Ernst Theodor and his mother moved back to their parents' house. Ernst Hoffmann, as he was called, hardly knew his father and had hardly any contact with his older brother. The third brother Carl Wilhelm Philipp (* 1773) died as a child. Hoffmann lived in his mother's parental home with his maternal grandmother Lovisa Sophia Doerffer, a widow, two aunts (Johanna Sophia and Charlotte Wilhelmine Doerffer) and an uncle (Otto Wilhelm Doerffer), both of whom were unmarried. The dominant personality in the household was the grandmother. The uncle, who had been given early retirement due to incompetence in the judicial service, was a pedantic idler and an object of ridicule for Hoffmann ( oh-woe-uncle ). Luise Albertine could not adequately raise her son, which is why her sister Johanna Sophia had to take more care of the child. Apparently, he had no closer bond with his mentally vulnerable mother. The later poet and priest Zacharias Werner lived in the same house for a while with his mother, so that Hoffmann and Werner met here. Hoffmann's mother died in 1796, as did his father a year later.

From 1782 Hoffmann attended the castle school in Königsberg, where he made friends with his classmate Theodor Gottlieb Hippel (1775–1843) in 1786 .

Study and engagement

Sixteen-year-old Hoffmann began studying law at the Albertus University in Königsberg in 1792 , as did his friend Hippel. The philosopher Immanuel Kant , who was teaching at the university at the same time, did not exert any major influence on Hoffmann himself. His most important teacher was the Kant student Daniel Christoph Reidenitz . In 1795 he passed the first state examination in law and became a trainee lawyer (auscultator) at the higher court in Königsberg. In addition, he devoted himself to writing, making music and drawing. Nothing of his musical or literary works from this period has survived. He had a preference for Mozart , made music and received training from the organist and Bach fanatic Christian Podbielski . A number of letters to his friend Hippel have survived from this period, which give an insight into his personal life at the time. Hoffmann gave music lessons, including a student named Dora Hatt. She was nine years older than him, married, had five children, and was unhappy in their marriage. After the correspondence with Hippel, though stylized in literary terms, Hoffmann fell “immortally” in love, but only dared to confide in his friend Hippel in 1794. This advised against a relationship. In 1796 - Dora had meanwhile given birth to her sixth child - Hoffmann got into a public argument with the husband and as a result was transferred to the regional government in Glogau , where he lived with his godfather Johann Ludwig Doerffer. In 1798 he got engaged to his cousin Wilhelmine "Minna" Doerffer there.

On June 20, 1798, Hoffmann passed his second state examination with the grade "excellent". This service gave him access to an internship at the location of his choice. So he went to the Supreme Court in Berlin , especially since his uncle Doerffer and his daughter, Hoffmann's fiancé Minna, moved there for professional reasons (he became a Secret High Tribunal Councilor) and took him with them. In August 1798 he went on his first major vacation trip to the Giant Mountains, to Bohemia and Saxony, where he was greatly impressed by the picture gallery in Dresden . Visits to the theater and attempts to compose singspiels (he took lessons from the composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt and composed the singspiel Die Maske , Hoffmann's first major composition that has survived) captured Hoffmann in Berlin, so that he passed his third state examination, the assessor exam , did not take part until March 27, 1800, this time with the grade “excellent”. During his first stay in Berlin, he also met Jean Paul . Nothing is known about relations with the early romantic circles in Berlin.

Hoffmann and Romanticism

The spirit of the pre-Romantic era of Sturm und Drangs, with the emergence of an untamed enthusiasm for literature in Germany, affected the entire Romantic era and thus also the young Hoffmann. Hoffmann did not belong directly to the group of early romantics in Jena , who rallied around the brothers Friedrich and August Wilhelm Schlegel and their magazine Athenäum , to which Novalis also made decisive contributions. Without the poetological guidelines of Friedrich Schlegel and Novalis, but also of Gotthilf Heinrich Schubert and his natural-philosophical-medical publications such as views from the night side of the natural sciences or the symbolism of dreams , Hoffmann's special aesthetics, his ambivalence, the oscillation between a supposedly " real “and another wonderful world, but hardly conceivable. Hoffmann is the first romantic who illuminates the “night side” of human existence in all its radicalism and poetizes it narrative. The medical and psychiatric knowledge that Hoffmann acquired through his friendship with the Bamberg doctors Adalbert Friedrich Marcus and Friedrich Speyer and through reading relevant psychiatric works by Johann Christian Reil , Joseph Mason Cox (1763-1818) and Philippe Pinel are also decisive .

The founding of the secret societies in the 18th century was also formative for Hoffmann's literary work . Among the best known are the resurrected Rosicrucian League and the Illuminati Order, along with numerous others. What they all had in common was that they acted in secret and that their knowledge could only be passed on within the secret society. This, too, provided sufficient material for literary processing. The existence of secret societies was taken up in " secret society novels ", and their "secret eerie" goings-on was imaginatively embellished. The literary “knitting pattern” was often similar: a young hero suddenly falls into the hands of a secret power that influences his future development or ruin. A work that stirred up both Hoffmann and his contemporary Ludwig Tieck was entitled Der Genius and was by Carl Friedrich August Grosse . Hoffmann himself is said to have written two secret society novels when he was twenty; but since no publisher could be found, they remained in the drawer and were later lost. His Serapion brothers take up this genre again. In many of his texts, Hoffmann repeatedly made the motive of being at the mercy of someone else 's power , in contrast to the tower society in Goethe's Wilhelm Meister , of being at the mercy of evil. The works of the so-called gothic novel , such as The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis, were an essential role model for Hoffmann .

Prussian government councilor

Justice service and marriage

In March 1800 Hoffmann passed his third exam and was transferred to Posen as a court assessor, which had belonged to Prussia since the second partition of Poland . For the first time he was no longer under the supervision of his relatives. In the seclusion of society in Posen, Hoffmann began to use alcohol, a habit that he maintained until the end of his life. Hoffmann did become an alcoholic, but he was not a typical, uncontrolled "drunkard". His biographer Wilhelm Ettelt stated: He seldom drank too much and never so much that it stole his senses . But he also tolerated more than most of his friends, who therefore partially withdrew from him - and Ludwig Devrient also made him partially responsible for his own alcoholism. In Berlin he spent social evenings with wine at Lutter and Wegner's almost every day, and he often stayed after the socializing after midnight until dawn. When he died, he owed 1116 Reichstalers to the landlord von Lutter and Wegner in Berlin. For comparison, he received an average fee of 50 to 100 thalers from his publisher - who was also a wine merchant.

On New Year's Eve 1800 a musical work by Hoffmann was performed for the first time in Posen ( cantata to celebrate the new century ). In 1801/02 his music for Goethe's Singspiel Scherz, List und Rache was performed several times. In Poznan he also met his future wife Marianne Thekla Michaelina Rorer, also Rorer-Trzcińska, (1778-1859), a Polish woman from a humble background. In order to marry his "Mischa", he broke off his engagement with Minna Doerffer, who had remained in Berlin, in March 1802. The couple married on July 26th.

Carnival joke and transfer

During the carnival in 1802, masked people suddenly appeared at the great carnival redoubt of the Prussian colony, who distributed caricatures of high-ranking representatives of the city to the guests. The familiar faces of major generals , officers and members of the aristocracy were clearly identifiable and put in ridiculous poses. The fun lasted until the mocked ones held themselves in their hands as a caricature. The “culprits” were never caught, but the authorities quickly agreed that there was a group of young government officials behind them, including the young Hoffmann, who had made his talent for drawing available for this unheard of action. Hoffmann, who was to be promoted to the government council this year (and hoped to perhaps be brought to Berlin or at least to a city further west), received the promotion, but at the same time also the transfer to the even smaller, intended as a sanction, Płock, a small town with 3,000 inhabitants to the east . From this period, entries in his diary have been preserved for the first time, which reflect his boredom and dissatisfaction.

The years in Płock (1802–1804) and those in Warsaw , where he was transferred in March 1804, were dominated by attempts at composition. Nonetheless, Hoffmann's legal work never suffered from his secondary occupations, he always had good references.

In Warsaw in particular, which was awarded to Prussia after the third partition of Poland in 1795 , Hoffmann gained a reputation as a skilled musician, albeit only at the local level. One of his Singspiele ( Die Lustige Musikanten , 1804, for the first time with the initials E. T. A. Hoffmann) and his symphony in E flat major were performed publicly. As the organizer of musical life, Hoffmann was one of the founders of the “Musical Society”, which had its seat in the Mniszech Palace and which set itself the task of organizing concerts for lovers and training amateur musicians. In Warsaw he met the lawyer Eduard Hitzig , who from then on would be one of his closest friends and one of his most important advisors.

During the war against France , the French marched into Warsaw on November 28, 1806. The Prussian government officials were suddenly unemployed. When the French authorities offered all officials who remained in Warsaw the alternative of either taking the oath of homage to Napoleon or leaving the city within a week, Hoffmann decided to leave.

1807 to 1818

New ways

Hoffmann had decided not to seek employment, but to become an artist. While his wife and two-year-old daughter Cäcilia moved to Posen in 1807, Hoffmann tried in vain to gain a foothold in Berlin. Nobody wanted to take notice of his compositions. Although, after numerous applications, he finally had the promise to become Kapellmeister at the Bamberg Theater from autumn 1808 , Hoffmann was financially exhausted by the spring of the same year. Desperate he wrote to Hippel:

“I work tired and weary, I take health risks and I don't buy anything! I do not like to describe my distress to you. I haven't eaten anything but bread for five days, and it's never been like this. If you can help me, send me about 20 Friedrichsdor , otherwise I don't know by God what will become of me! "

Hippel sent money; At the same time, on the initiative of Freiherr von Stein, all officials who had become ailing through the war with France were granted a one-off payment.

The Kapellmeister

Hoffmann moved with his wife in September 1808 - their daughter Cäcilia had already died - to Bamberg , where his debut as music director failed in October due to inadequate performance of the orchestra and the singers at the opera he conducted . Intrigues against him caused Hoffmann to lose the job after only two months. His theatrical compositions were not profitable enough, but in return Hoffmann received an offer from the publisher of the Leipziger Allgemeine Musical Zeitung to write music reviews for the paper after he had been able to publish his story Ritter Gluck there in 1809 .

During this time he also developed the fictional character of Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler , his literary alter ego , who presented his view of the musical works to be discussed in the magazine. It later found significant musical expression in Robert Schumann's piano work Kreisleriana . It is also Kapellmeister Kreisler who encounters the reader again in the stories Kreisleriana and in the novel Life Views of the Cat Murr and The Golden Pot .

From 1810 onwards, Hoffmann was employed by the Bamberg Theater as a manager assistant, dramaturge and decorative painter. He also gave private music lessons. Hoffmann fell so deeply in love with the young singing student Julia Mark that it was most embarrassingly noticed in his surroundings and Julia's mother hurriedly watched the girl marry off elsewhere. Hoffmann no longer held anything in Bamberg. When he was offered the position of music director at Joseph Secondas in Dresden and Leipzig performing opera company, he accepted.

Return to civil service

The break with Joseph Seconda took place in 1814, but after Prussia's victory over Napoleon, Hoffmann had the opportunity to return to the Prussian civil service in Berlin. However, he has not yet received a fixed salary for his work at the Supreme Court , but only a one-off fee.

That's why he was all the more pleased that he had now earned a reputation as a writer. The publication of the fantasy pieces in Callot's manner (1814/1815), especially that of the fairy tale The golden pot contained in this collection, was a success, to which Hoffmann wanted to build on with his work on the novel The Elixirs of the Devil and the Night Pieces , which he wanted but did not succeed. However, Hoffmann became a sought-after author for paperback and almanac retellings, a sideline that kept him afloat financially. He was particularly proud that his opera Undine was premiered in 1816 in the Nationaltheater in Berlin. During these years Hoffmann maintained friendly relations with the writers Karl Wilhelm Contessa , Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué , Clemens Brentano , Adelbert von Chamisso and the actor Ludwig Devrient .

In 1816 Hoffmann was appointed judge of the chamber judge, with which a fixed salary was connected. Nonetheless, he was always drawn to art, especially music. However, his applications for various Kapellmeister posts were all rejected.

1819 to 1822

With Die Serapionsbrüder , life views of the cat Murr and Klein Zaches called Zinnober , Hoffmann's literary successes continued in the next few years. In the meantime, after Napoleon's defeat in Germany, the Metternich system of political restoration prevailed .

The Immediatkommission

In Berlin, the “Immediate Commission of Inquiry to Investigate Treasonous Connections and Other Dangerous Activities” was set up, whose task was to “identify dangers threatening Prussia and Germany”. Hoffmann became a member of the Immediatkommission as a member of the chamber judge. He could not get used to the views and activities of the fraternities and gymnastics associations , but he dutifully fulfilled his task of investigating the facts fairly and legally. The commission was also responsible for examining the reasons for arresting people. Numerous people were arrested simply because of their identification with the ideas of the fraternities and gymnastics associations. In the period that followed, the commission drafted numerous reports on individual “perpetrators”, among other things, Hoffmann was also responsible for the case of “gymnastics father” Jahn . In many cases, the commission ruled - not least on the basis of Hoffmann's report - that the reasons were neither sufficient for imprisonment nor for prosecution because no illegal act could be ascertained. In its reports, the commission repeatedly made it clear that a conviction alone is not a criminal offense.

Master Flea

The ministerial director in the police ministry, Karl Albert von Kamptz , was extremely dissatisfied with the decisions of the Immediatkommission and pleaded for tougher action against the protesters. In the case of the student Gustav Asverus, Kamptz saw it as extremely stressful that the young man had once noted the word “lazy to death” in his diary. For Kamptz, this was a clear indication that Asverus was up to evil, possibly even having committed such acts - because if you call yourself “lazy to murder” on one day, then maybe not on other days. This story about Gustav Asverus was known in the Immediatkommission and probably led to great amusement, because Hoffmann felt inspired to parody the incident later in his master Flea . He had no idea that this would cause him a lot of trouble.

Censorship and Disciplinary, Illness and End

Hoffmann had told his friends about the fourth and fifth chapters of Master Floh in his local pub “ Lutter & Wegner ” . Word got around and was finally passed on to Kamptz. Hoffmann was warned, but his attempt to have the two chapters removed from the manuscript that had long been with the publisher in Frankfurt am Main failed. The manuscript was already confiscated.

It cannot be ruled out that the Prussian police ministry could not have proven Hoffmann at all that he had ridiculed and ridiculed the ministerial director Kamptz in the figure of Knarrpanti, or that it would at least have had difficulties in "twisting a rope" from this artistic processing ". But Hoffmann couldn't help but write a “lazy murder” in his Peregrinus Tyß's diary elsewhere. As if that wasn't enough, he had Knarrpanti underline this unusual word in red pencil several times - as happened in the original case file by Kamptz. Hoffmann had thus committed an offense that no judge is permitted to do: he had made the non-public content of a trial file public through his story. His captors easily followed up on this breach of duty. Master Flea appeared censored for several episodes in the fourth and fifth adventures; the suppressed passages were not published until 1908.

E. T. A. Hoffmann, who also suffered increasingly from health problems from 1818, fell ill with progressive paralysis, the cause of which is unknown. Syphilis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) were named as possible causes . It began on his feet and legs on his birthday in January 1822 and moved quickly, spreading in his arms so that he could no longer write, and eventually resulted in loss of speech and respiratory paralysis. His mental abilities were preserved.

On February 4, 1822, the royal Prussian State Minister of the Interior Friedrich von Schuckmann wrote a letter to the Prussian State Chancellor Karl August Fürst von Hardenberg , in which he described Hoffmann as a "negligent, highly unreliable and even dangerous state official" and the imposition of disciplinary measures against him proposed. On the occasion, Schuckmann also rehashed the incident with the caricatures in Poznan. However, the questioning of Hoffmann about his wrongdoing was delayed because Hippel obtained a reprieve for his friend. Hoffmann's disease was already well advanced at this time; Due to the progressive paralysis that went with it, the patient was tied to the room and to the armchair. He could only dictate his defenses, as his hands were already failing.

In the period that followed, Hoffmann wrote a few more stories, including Des Vetter's corner window , before he died on the morning of June 25, 1822 in his apartment on Taubenstrasse in Berlin due to respiratory paralysis.

dig

E. T. A. Hoffmann's grave is located in Cemetery III of the Jerusalem and New Churches in front of Hallescher Tor near the Mehringdamm underground station in Berlin-Kreuzberg . The friends of the dead donated a grave monument made of sandstone, which weathered so badly in the following decades that it had to be replaced by a new version made of gray syenite in 1905 , now financed by the parish. The grave inscription adopted from the original contains the first name abbreviation E. T. W. after Hoffmann's actual name, which was consciously chosen by his friends. They also put his official position on the tombstone in the first place in order to counter the state slurs.

By resolution of the Berlin Senate , the last resting place of E. T. A. Hoffmann (grave location 311-32-6) has been dedicated as an honorary grave of the State of Berlin since 1952 . The dedication was extended in 2016 by the now usual period of twenty years.

estate

Hoffmann's estate was auctioned off the same year he died. His friend Julius Eduard Hitzig bought a part. Much can no longer be found today. Part of his compositional legacy is in the Berlin State Library . In the Märkisches Museum there is the manuscript for the night piece Der Sandmann from the bundle acquired by Hitzig . Hoffmann collections are available from the Berlin and Bamberg State Libraries and from the University Library in Munich ( Carl Georg von Maassen Library ).

Memorial plaques

The inscription on the memorial plaque at Charlottenstrasse 56 in Berlin-Mitte reads:

THE WRITER KAMMER

-GERICHTS-RATH

ERNST THEODOR AMADEUS

HOFFMANN

LIVED HERE FROM JULY 1815 UNTIL HIS DEATH

ON JUNE 25, 1822. THE CITY

OF

BERLIN IN HIS MEMORIAL IN 1890

The inscription on the commemorative plaque attached in 1908 to the ETA Hoffmann House , Schillerplatz 26 in Bamberg (Hoffmann's second Bamberg apartment) reads:

The poet

composer and painter

E. TW Amadäus Hoffmann

lived in this house from

1809 to 1813.

reception

Hoffmann's literary contemporaries reacted ambiguously to his work and his person. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe could not do anything with Hoffmann's writings, and Joseph von Eichendorff also behaved negatively. Jean Paul had little esteem for Hoffmann, but accepted the dedication of the fantasy pieces in Callot's manner . Wilhelm Grimm took a liking to the story Nutcracker and Mouse King , but judged:

"This Hoffmann is repulsive to me with all his spirit and wit from beginning to end."

Heinrich Heine and Adelbert von Chamisso , on the other hand, valued Hoffmann's works as much as Honoré de Balzac , George Sand and Théophile Gautier . After Hoffmann's death, the reactions in his home country were more derogatory than abroad. In France in particular, Hoffmann became a classic early on. Literary influences can be seen in Victor Hugo , Charles Baudelaire , Guy de Maupassant , Alexander Pushkin and Fyodor Dostoyevsky , but also in Edgar Allan Poe . Hoffmann's success in non-German-speaking countries was greater than in his home country.

With his anticipation of the literature of fantasy , Hoffmann became the leading figure of the second generation of French Romanticism, the so-called Jeunes-France . It was the Berlin doctor and poet David Ferdinand Koreff , who was friends with Hoffmann, and the translator François-Adolphe Loève-Veimar , who made Hoffmann's works known in France shortly after his death, which influenced Théophile Gautier in particular. In Germany, Hoffmann's work, which many contemporaries, including Goethe and Walter Scott , rejected as “sick”, fell into oblivion more and more after his death. Goethe translated, however, from Scott's extensive essay on Hoffmann's night pieces, which fluctuated between “admiration and criticism”, “only the short negative concluding remark and he sharpened Scott's phrases with his translation, so that they read as a devastating judgment. In Goethe's translation of 1827 it says among other things: 'It is impossible to subject fairy tales of this kind to any criticism; [...] they are feverish dreams of an easily agile sick brain ”.

Richard Wagner received lively inspiration for his own works from Hoffmann's texts. In particular, episodes from the Serapion brothers influenced Wagner's Paris novellas , the Meistersinger and Tannhauser, among others . Wagner's Der Fliegende Holländer also owes its mystical night-black character to Hoffmann.

About thirty years after his death and the success of his works in France, E. T. A. Hoffmann was made the protagonist of the play Les Contes d'Hoffmann by the French authors Michel Carré and Jules Paul Barbier . They modified three of his stories so that he became the main character in each, and added some details from his biography and other narratives. The Franco-German composer Jacques Offenbach saw this play and suggested using it to create a libretto for an opera. This is what Jules Barbier did after the death of Michel Carré. Jacques Offenbach was able to do most of his compositional work before his death in October 1880, but left the opera unfinished. The Contes d'Hoffmann (Hoffmann's stories) are now part of the standard repertoire of opera houses.

Around 1900, through the mediation of Franz Blei and Julius Rodenberg, a reassessment took place, which was then followed by German Expressionism .

Of the German-speaking authors of the present, Ingo Schulze and Uwe Tellkamp in particular have admitted that E. T. A. Hoffmann is their role model. In the novel Der Turm , published in 2008, Tellkamp describes the performance of a dramatized version of Hoffmann's Der goldenne Topf in Dresden in the 1980s.

The reception of E. T. A. Hoffmann's works in the pan-European context represents one of the most interesting chapters in the history of reception of German Romanticism . In addition to French, especially Russian literature, such as the stories by Nikolai Gogol , as well as Hoffmann's reference, which has still not been researched, deserve special mention to Poland.

Appreciation

Hoffmann's work, known today, was created over a period of thirteen years. The fact that he dared to commit to writing so late in the day can be attributed to his original preference for music; Hoffmann felt more a vocation as a composer. The novellas he had written before 1809 had either not been approved or they were lost. In many of his works he stayed true to the taste of his reading contemporaries: stories about uncanny events, encounters with the devil , fateful twists and turns in the life of a protagonist that the protagonist cannot resist. However - and this is what distinguishes Hoffmann's work both from the rationalistic horror stories of the Enlightenment as well as from authors of the “Sturm und Drang” era that came to an end - he virtuously condensed his stories into the often unanswered question of whether the ghost described actually took place or perhaps itself only played in the head of the affected character.

Hoffmann integrated a lot of real-time information into his works, for example the fears of his contemporaries about technical innovations who were both fascinated and suspicious of the development of machines (which at that time were not assigned the masculine article, but either "the machine" or "the machine." “Were called). Consequently, the fate of some of his characters is fatally linked to this new achievement ( The Sandman , The Automate ), where Hoffmann combines technology and occultism (especially the theories of mesmerism ) in a characteristic way .

Hoffmann's versatility, his talent for drawing and also his professional practice as a lawyer made him a keen observer. He caricatured philistinism and narrow-mindedness with drawings and finally also in the form of social satire (e.g. Klein-Zaches called Zinnober ) - and how right he was with his assessment of some contemporaries is shown by the hectic overreactions of the Prussian police ministry following the seizure of the Manuscripts by Master Flea .

However, anti-Jewish clichés also flowed into Hoffmann's work. According to Gunnar Och , these are particularly evident in the story Die Brautwahl . Here Jews or with negative ridiculed pulling connotations both in terms of physiognomy occupied and their character (eg. As the nose of one of the figures, "greed" from opportunistic reasons, conversion-ready , "evil arts", "dirty pettiness", " stupid, cheeky, intrusive ”,“ in the whole essence the most pronounced character of the people from the Orient ”). In addition, parallels or allusions to Shakespeare's play The Merchant of Venice are repeatedly incorporated.

Hoffmann's talents could never be clearly separated from one another in their diverse expressions. Music, writing and drawing, but also law, often merged. Hoffmann illustrated many of his stories himself. And there is even a caricature on the cover of a judicial file edited by Hoffmann, which lets two officials, riding a cat and a dog, attack each other.

Aftermath today

The ETA Hoffmann-Gesellschaft e. V., a literary society founded on June 14, 1938 and based in Bamberg , is dedicated to Hoffmann's person and work. She also looks after the ETA Hoffmann House in Bamberg .

The city of Bamberg's literary prize named after him, the E. T. A. Hoffmann Prize , has been awarded every two years since 1989. Since 1970 the theater in Bamberg has been called ETA-Hoffmann-Theater .

Works

Literary works

-

Fantasy

pieces in Callot's manner (1814/1815) include:- Jaques Callot

- Knight Gluck

- Kreisleriana

- Don juan

- News of the latest fate of the dog Berganza

- The magnetizer

- The golden pot (first published in 1814, revised in 1819)

- The adventures of New Years Eve

- Princess Blandina

- The elixirs of the devil (1815/1816)

- Night pieces (1816/1817)

- Strange Sorrows of a Theater Director (1818)

- Klein Zaches called Zinnober (1819)

- Haimatochare (1819)

- The Marquise de la Pivardiere (After Richers Causes Célèbres) (1820)

- Princess Brambilla (1820)

-

The Serapion Brothers (1819/1821)

include:- The Hermit Serapion

- Council Krespel

- The fermata

- The poet and the composer

- A fragment from the lives of three friends

- The Artus Court

- The mines at Falun

- Nutcracker and Mouse King

- The fight of the singers

- The automat

- Doge and Dogaresse

- Master Martin the Küfner and his journeymen

- The strange child

- Message from the life of a well-known man

- The bride choice

- The creepy guest

- The Miss von Scuderi

- Player luck

- The baron of B.

- Signor Formica

- Zacharias Werner

- Apparitions

- The context of things

- vampirism

- The aesthetic tea party

- The royal bride

- Views of the life of the cat Murr (1819/1821)

- The Errors (1820)

- The Secrets (1821)

- The Double Walkers (1821)

- The Elemental Spirit (1821)

- Master Flea (1822)

- The cousin's corner window (1822)

- The enemy (fragment) (1822)

The anonymously published erotic novel Sister Monika (1815) is attributed to Hoffmann. Gustav Gugitz was the first to speculate as the author , but the Hoffmann editor Rudolf Frank also provided reasons.

Musical works

Vocal music

- Messa in D minor. (1805)

- Trois Canzonettes à 2 et à 3 voix (1807)

- 6 canzoni per 4 voci a cappella (1808): Ave Maris Stella, De Profundis, Gloria, Salve Redemptor, O Sanctissima, Salve Regina

- Miserere in B flat minor (1809), presumably identical to Requiem

- In the white waters of the Irtian (Kotzebue), song (1811)

- Recitativo ed Aria "Prendi l'acciar ti rendo" (1812)

- Tre Canzonette italiane (1812); 6 Duettini italiani (1812)

- Night singing, Turkish music, hunter song, cat boy song for male choir (1819–1821)

Stage works

- The Mask (Libretto: ETA Hoffmann), Singspiel (1799)

- The Funny Musicians (Libretto: Clemens Brentano ), Singspiel (1804)

- Incidental music for Zacharias Werner's tragedy The Cross on the Baltic Sea (1805)

- Love and Jealousy Calderón / August Wilhelm Schlegel (1807)

- Arlequin , ballet music (1808)

- The potion of immortality (libretto: Julius von Soden ), romantic opera (1808)

- Goodbye (Libretto: ETA Hoffmann), Prologue (1809)

- Dirna (libretto: Julius von Soden), melodrama (1809)

- Incidental music for Julius von Soden's drama Julius Sabinus (1810)

- Saul, King of Israel (Libretto: Joseph von Seyfried ), melodrama (1811)

- Aurora (libretto: Franz Ignaz von Holbein ), heroic opera (1812)

- Undine (Libretto: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué ), Magic Opera (1816)

- The lover after death (stuck in the beginning)

Instrumental music

- Rondo for piano (1794/1795)

- Overture. Musica per la chiesa in D minor (1801)

- 5 piano sonatas: A major, F minor, F major, F minor, C sharp minor (1805-1808)

- Great Fantasy for Piano (1806) (not preserved)

- Symphony in E flat major (1806)

- Harp Quintet in C minor (1807)

- Grand Trio in E major (1809) for violin, violoncello and piano

- Caroline's Day Waltz (1812) (not preserved)

- Serapions Waltz (1818–1821) (not preserved)

- Fantasy of Germany's triumph in the battle of Leipzig (published in Leipzig in 1814 under the pseudonym Arnulph Vollweiler ) (lost)

Arrangements (music, film)

- The Russian composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky used Hoffmann's fairy tale Nutcracker and Mouse King as a literary model for his ballet The Nutcracker .

- Léo Delibes composed the ballet Coppélia based on the story The Sandman , which was premiered in Paris in 1870 .

- The composer Jacques Offenbach composed the opera Hoffmann's Tales through the writer Hoffmann , which premiered in Paris in 1881 .

- With his piano piece Kreisleriana , published in 1838, the composer Robert Schumann referred to the stories Kreisleriana as well as the figure of Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler created by Hoffmann in this context.

- Ferruccio Busoni's opera The Bride's Choice from 1905 is based on the story of the same name from the Serapion brothers .

- Paul Hindemith's opera Cardillac from 1926 is based on the story Das Fräulein von Scuderi .

- Manfred Knaak's musical Das Collier des Todes from 2007 is also based on the story Das Fräulein von Scuderi .

- Andrei Tarkovsky wrote a film book under the title Hoffmanniana (edited in 1984) in 1974 without realizing the film.

- In April 1974, Franz Fühmann conceived a feature film scenario of ETA Hoffmann's desolate house and produced the draft for it in the summer of 1984 under the title The desolate house. A night piece by ETA Hoffmann (it is Fühmann's last work before his death), a film was never made.

Radio play adaptations

- 1965: The Miss von Scuderi . With Maria Nicklisch (Fräulein von Scuderi), Lina Carstens (Martiniére), Herbert Kroll (Bastiste), Elfriede Gerhard (Marquise von Maintenon), Fritz Straßner (René Cardillac), Christa Berndl (Madelon), Hans Michael Rehberg (Olivier Brusson), Horst Tappert (King), Wolf Dieter Euba (Narrator) a. v. a. Director: Edmund Steinberger. BR 1965.

- 2006: The Serapions Brothers . Radio play in 12 parts. With Herbert Fritsch , Felix von Manteuffel , Bernhard Schütz , Stefan Wilkening , Werner Wölbern , Manfred Zapatka and others. a. Manuscript, composition and direction: Klaus Buhlert . BR radio play and media art 2006. As a podcast / download in the BR radio play pool.

expenditure

- ETA Hoffmann's selected fonts. 10 parts in 10 or 5 volumes. Reimer, Berlin 1827-1828

- ETA Hoffmann's collected writings. 12 parts in 6 volumes. Reimer, Berlin 1844-1845, ²1857, ³1871–1873 (these editions with pen drawings by Theodor Hosemann )

- ETA Hoffmann's works. In: National library of all German classics: Collection 2. Hempel, Berlin 1879–83

- Carl Georg von Maassen (Ed.): ETA Hoffmann. Complete Works. Historical-critical edition with introductions, notes and readings. 9 volumes (15 volumes planned, only volumes 1–4, 6–8 and 9/10 have been published). Georg Müller, Munich 1908–1928

- Georg Ellinger (ed.): ETA Hoffmanns works. Reissued based on the Hempel edition. 15 volumes. Bong, Berlin 1912

- Jürg Fierz (Ed.): ETA Hoffmann. Master stories, illustrated by Paul Gavarni , Manesse Verlag, Zurich 2001, ISBN 3-7175-1188-2 .

- Eduard Grisebach (Ed.): ETA Hoffmann. All works in 15 volumes. Hessescher Verlag, Leipzig 1900 (2nd edition 1909 with additional musical writings)

- Hans von Müller (ed.): ETA Hoffmann in personal and correspondence. His correspondence and the memories of his acquaintances. 2 volumes. Paetel, Berlin 1912.

- Leopold Hirschberg (Ed.): ETA Hoffmanns all works. Serapions edition in 14 volumes , Berlin 1922, W. de Gruyter. [authentic orthography, all preserved works in chronological order]

- Adolf Spemann (Ed.) Musical poems and essays by ETA Hoffmann. Musical folk books. J. Engelhorn's descendants, Stuttgart 1922

- Walther Harich (Ed.): ETA Hoffmann. Seals and writings as well as letters and diaries. Complete edition in 15 volumes. Lichtenstein, Weimar 1924

- Klaus Kanzog (Ed.): ETA Hoffmann. Poetic works. With pen drawings by Walter Wellenstein . 12 volumes. de Gruyter, Berlin 1957–1962

- ETA Hoffmann, Poetic Works , 6 volumes, Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin, 1958, with an essay by Hans Mayer “The Reality of ETA Hoffmann - An Attempt”.

-

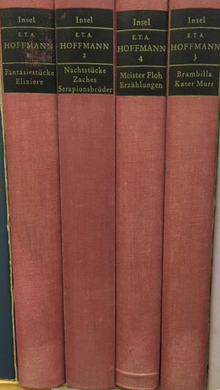

ETA Hoffmann. All works in individual volumes (= Winkler edition), 6 volumes; Introductions: Walter Müller-Seidel ; Winkler Verlag, Munich 1960–1965. [authentic punctuation, modernized orthography]

- Volume 1, 1960 Fantasy and Night Pieces . Notes: Wolfgang Kron.

- Volume 2, 1961 Elixirs of the Devil , Kater Murr . Notes: Wolfgang Kron.

- Volume 3, 1963 Serapions Brothers . Notes: Wulf Segebrecht .

- Volume 4, 1965 Late Works . Notes: Wulf Segebrecht.

- Volume 5, 1963 Writings on Music . Notes: Friedrich Schnapp .

- Volume 6, 1963 gleanings . Notes: Friedrich Schnapp.

- In addition:

- Correspondence. Collected and explained by Hans von Müller and Friedrich Schnapp. 3 volumes. Winkler Verlag, Munich 1968.

- Diaries. Edited by Friedrich Schnapp after the edition by Hans von Müller with explanations. Winkler Verlag, Munich 1971.

- Legal work. Winkler Verlag, Munich 1973.

- ETA Hoffmann in his friends' notes. Winkler Verlag, Munich 1974.

- The musician ETA Hoffmann - A document volume. Hildesheim 1981.

- Hans Joachim Kruse et al. (Ed.): ETA Hoffmann. Collected works in individual editions. 9 volumes (originally made up of 12 volumes, but the legal writings / diaries / letters have not appeared). Structure, Berlin 1976–1988. New edition (8 volumes): Aufbau, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-351-02261-1 .

- ETA Hoffmann: All works in six volumes. Edited by Hartmut Steinecke and Wulf Segebrecht. Deutscher Klassiker Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985–2004.

- Volume 1: Early prose , letters , diaries , libretti , legal writings. Works 1794–1813. Edited by Gerhard Allroggen u. a. (= Library of German Classics. 182). Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-618-60855-1 .

- Volume 2.1: Fantasy pieces in Callot's manner. Works 1814. Ed. Hartmut Steinecke with the collaboration of Gerhard Allroggen and Wulf Segebrecht (= Library of German Classics. 98). Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-618-60860-8 .

- Volume 2.2: The Elixirs of the Devil. Works 1814–1816. Edited by Hartmut Steinecke and Gerhard Allroggen (= Library of German Classics. 37). Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-618-60840-3 .

- Volume 3: Night Pieces , Little Zaches , Princess Brambilla. Works 1816–1820. Edited by Hartmut Steinecke with the assistance of Gerhard Allroggen (= Library of German Classics. 7). Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-618-60870-5 .

- Volume 4: The Serapions Brothers. Edited by Wulf Segebrecht and Ursula Segebrecht (= Library of German Classics. 175). Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-618-60880-2 .

- Volume 5: life views of the cat Murr. Works 1820–1821. Edited by Hartmut Steinecke and Gerhard Allroggen (= Library of German Classics. 75). Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-618-60890-X .

- Volume 6: Late prose , letters , diaries and notes , legal writings. Works 1814–1822. Edited by Gerhard Allroggen, Friedhelm Auhuber, Hartmut Mangold, Jörg Petzel, Hartmut Steinecke (= library of German classics. 185). Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-618-60900-0 .

ETA Hoffmann as a literary figure

- Erich Schönebeck : The dangerous flea. A novella about ETA Hoffmann's last days. Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1953, DNB 454447442 .

- Werner Bergengruen : ETA Hoffmann . Peter Schifferli, Verlag AG “Die Arche”, Zurich 1960, DNB 450371492 .

- Gerhard Mensching : ETA Hoffmann's last story. Novel. Haffmans Verlag, Zurich, 1989, ISBN 3-251-00147-7 .

- Ronald Fricke: Hoffmann's last story. Novel. Rütten and Loening, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-352-00561-3 .

- Ralf Günther : The thief of Dresden. Historical novel. List Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-471-79555-2 . (ETA Hoffmann investigates a murder and espionage case during his time in Dresden)

- Dieter Hirschberg: The black muse. A case for ETA Hoffmann. Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89809-027-2 . (The officer ETA Hoffmann, who has been transferred to the Prussian province, investigates three murder cases in this historical crime thriller)

- Dieter Hirschberg: Diary of the devil. ETA Hoffmann continues to investigate. Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89809-500-2 . (ETA Hoffmann in a historical crime thriller in Berlin)

- Dieter Hirschberg: Deadly Lodge. ETA Hoffmann under suspicion. Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89809-503-7 . (ETA Hoffmann in a historical crime thriller in Berlin)

- Peter Härtling : Hoffmann or The Diverse Love. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2001.

- Kai Meyer: The ghost seers. 1995, ISBN 3-404-14842-8 . (ETA Hoffmann in a historical crime thriller in Warsaw)

- Hoffmanniana : radio play based on a scenario by Andrej Tarkowskij. Editing / Direction: Kai Grehn. Composition: Kai-Uwe Kohlschmidt . Production: rbb / SWR 2004.

literature

General

- E. T. A. Hoffmann Society (Ed.): E. T. A. Hoffmann Yearbook. Erich-Schmidt-Verlag, Berlin, Volume 1.1992 / 93 ff. ISSN 0944-5277

- Jürgen Manthey : The birth of a world artist (ETA Hoffmann) , in ders .: Königsberg. History of a world citizenship republic . Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-423-34318-3 , pp. 397-423.

- Detlef Kremer (Ed.): ETA Hoffmann. Life - work - effect. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-018382-5 .

Biographies and general presentations

- Peter Braun : ETA Hoffmann. Poet, draftsman, musician. Biography. Artemis and Winkler, Düsseldorf et al. 2004, ISBN 3-538-07175-6 .

- Peter Braun: ETA Hoffmann in Bamberg. Erich Weiß Verlag, Bamberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-940821-38-6 .

- Wilhelm Ettelt: ETA Hoffmann. The artist and the person. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1981, ISBN 3-88479-031-5 .

- Brigitte Feldges, Ulrich Stadler: ETA Hoffmann. Epoch - work - effect. Beck, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-406-31241-1 .

- Susanne Gröble: ETA Hoffmann. (= Universal library. 15222). Reclam, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-015222-4 .

- Klaus Günzel : ETA Hoffmann. Life and work in letters, personal testimonies and contemporary documents. Bibliography. Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1976, DNB 760255245 .

- Gerhard R. Kaiser: ETA Hoffmann. (= Metzler Collection. 243; Realities on literature). Metzler, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-476-10243-2 .

- Eckart Kleßmann : ETA Hoffmann or the depth between star and earth. A biography. (= Insel-Taschenbuch. 1732). Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-458-33432-7 .

- Detlef Kremer: ETA Hoffmann for an introduction. (= Introduction. 166). Junius, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-88506-966-0 .

- James M. McGlathery: ETA Hoffmann. World Authors Series (Book 868) Twayne Publishers, Boston 1997, ISBN 978-080574-619-8 .

- Rüdiger Safranski : ETA Hoffmann. The life of a skeptical fantasist. (= Fischer pocket books; 14301). Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-596-14301-2 .

- Wulf Segebrecht : Hoffmann, Ernst Theodor Wilhelm. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , pp. 407-414 ( digitized version ).

- Wulf Segebrecht: Heterogeneity and Integration. Studies on the life, work and impact of ETA Hoffmann. (= Helicon. 20). Lang, Frankfurt a. a. 1996, ISBN 3-631-47202-1 .

- Hartmut Steinecke : ETA Hoffmann. (= Universal Library. 17605). Reclam, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-15-017605-0 .

- Hartmut Steinecke: The Art of Fantasy. ETA Hoffmann's life and work. Insel, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 2004, ISBN 3-458-17202-5 .

- Hartmut Steinecke (Ed.): ETA Hoffmann. (Series: Studies). Research paper. Scientific Book Society , Darmstadt 2006.

- Gerhard Weinholz: ETA Hoffmann. Poet, psychologist, lawyer. (Series of Literature Studies in the Blue Owl. 9). The Blue Owl, Essen 1991, ISBN 3-89206-431-8 .

- Gabrielle Wittkop -Ménardeau: ETA Hoffmann. With testimonials and photo documents. (= Rowohlt's monographs. 50113). Rowohlt, Reinbek 1966, ISBN 3-499-50113-9 . (17th edition 2004)

Hoffmann as a musician

- Fausto Cercignani : ETA Hoffmann, Italy and the romantic conception of music. In: SM Moraldo (Ed.): The land of longing. ETA Hoffmann and Italy. Winter, Heidelberg 2002, ISBN 3-8253-1194-5 , pp. 191-201.

- Hermann Dechant : ETA Hoffman's opera Aurora (= Regensburg Contributions to Musicology , Volume 2). Bosse, Regensburg 1975, ISBN 3-7649-2118-8 .

- Werner Keil : ETA Hoffmann as a composer. Studies on composition technique on selected works (= New Music History Research , 14). Breitkopf and Härtel, Wiesbaden 1986, ISBN 3-7651-0229-6 .

- Ingo Müller: "The alien spirit destroys the magic of words". ETA Hoffmann's aesthetics of the verse song in the context of contemporary song aesthetics and romantic universality. In: ETA Hoffmann yearbook. Volume 22, ed. by Hartmut Steinecke and Claudia Liebrand, Berlin 2014, pp. 78–97.

- Diau-Long Shen: ETA Hoffmann's way to the opera. From the idea of the romantic to the genesis of romantic opera (= perspectives of opera research , edited by Jürgen Maehder and Thomas Betzwieser, volume 24). Peter Lang Academic Research, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 3-631-66397-8 .

Hoffmann as a writer

- Michael Bienert : ETA Hoffmanns Berlin. Literary Schauplätze , Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg , Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-945256-30-5 .

- Klaus Deterding: The poetics of the inner and outer world at ETA Hoffmann. To the constitution of the poetic in the works and personal testimonies. Dissertation, FU Berlin. (= Berlin contributions to recent German literary history. 15). Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1991, ISBN 3-631-44062-6 .

- Klaus Deterding: Magic of Poetic Space. ETA Hoffmann's poetry and worldview. Winter, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-8253-0541-4 . (Contributions to modern literary history. Third part, volume 152)

- Klaus Deterding: The most wonderful fairy tale. ETA Hoffmann's poetry and worldview. Volume 3, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2003, ISBN 3-8260-2389-7 .

- Klaus Deterding: Hoffmann's Poetic Cosmos. ETA Hoffmann's poetry and worldview. Volume 4, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2003, ISBN 3-8260-2615-2 .

- Manfred Engel : ETA Hoffmann and the poetics of early romanticism - using the example of “Der Goldne Topf”. In: Bernd Auerochs, Dirk von Petersdorff (Ed.): Unity of Romanticism? On the transformation of early romantic concepts in the 19th century . Paderborn u. a. 2009, ISBN 978-3-506-76665-6 , pp. 43-56.

- Franz Fühmann : Miss Veronika Paulmann from the Pirna suburb or something about the horrible at ETA Hoffmann. Rostock 1979 / Hamburg 1980, ISBN 3-455-02281-2 .

- Lutz Hagestedt : The genius problem at ETA Hoffmann. An interpretation of his late story “Des Vetters Eckfenster”. Friedl Brehm, Munich 1991 (again: belleville, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-923646-82-8 ).

- Johannes Harnischfeger: The hieroglyphs of the inner world. Romantic criticism at ETA Hoffmann. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1988, ISBN 3-531-12019-0 .

- Christian Jürgens: The theater of images. Aesthetic models and literary concepts in ETA Hoffmann's texts. Manutius-Verlag, Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 3-934877-29-X .

- Sarah Kofman: Write like a cat. On ETA Hoffmann's 'life views of the cat Murr'. Edition Passagen, Graz 1985, ISBN 3-205-01301-8 .

- Detlef Kremer: Romantic Metamorphoses. ETA Hoffmann's stories. Metzler, Stuttgart a. a. 1993, ISBN 3-476-00906-8 .

- Detlef Kremer: ETA Hoffmann. Stories and novels. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-503-04939-8 .

- Alexander Kupfer: Portrait of the artist as a Spalanzan bat. Intoxication and vision at ETAH. In: dsb: The artificial paradises. Intoxication and reality since romanticism. A manual. Metzler, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-476-02178-5 , pp. 479-502. (Düsseldorf, Univ., Diss., 1994) (first 1996: ISBN 3-476-01449-5 )

- Peter von Matt : The eyes of the machines. ETA Hoffmann's theory of imagination as a principle of his storytelling. Tübingen 1971. (Habilitation thesis).

- Magdolna Orosz: Identity, Difference, Ambivalence. Narrative structures and narrative strategies at ETA Hoffmann. (= Budapest Studies in Literary Studies. 1). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 2001, ISBN 3-631-38248-0 .

- Jean-Marie Paul (Ed.): Dimensions of the fantastic. Studies on ETA Hoffmann . Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert 1998, ISBN 978-3-86110-173-4 .

- Stefan Ringel: Reality and imagination in ETA Hoffmann's work. Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 1997, ISBN 3-412-04697-3 .

- Günter Saße (Ed.): Interpretations. ETA Hoffmann: Novels and Stories . Reclam, Stuttgart 2004.

- Olaf Schmidt: "Callot's fantastically caricatured leaves". Intermedial productions and romantic art theory in ETA Hoffmann's work. (= Philological studies and sources. 181). Schmidt, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-503-06182-7 .

- Jörn Steigerwald: The fantastic imagery of the city. To justify the literary fantasy in ETA Hoffmann's work . (= Foundation for Romantic Research . 14). Wuerzburg 2001.

- Hartmut Steinecke: Comment. In: ETA Hoffmann: Complete works in six volumes. Edited by Hartmut Steinecke and Wulf Segebrecht, Frankfurt am Main 1985–2004. (= Library of German Classics), Volume 3: Night Pieces. Little Zaches. Princess Brambilla. Works 1816–1820. Edited by Hartmut Steinecke with the assistance of Gerhard Allroggen, Frankfurt am Main (new edition) 2009, ISBN 978-3-618-68036-9 , pp. 921–1178.

- Peter Tepe, Jürgen Rauter, Tanja Semlow: Conflicts of interpretation using the example of ETA Hoffmann's “The Sandman”. Cognitive hermeneutics in practical application. Study book literary studies. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8260-4094-8 .

Hoffmann as a lawyer

- Arwed Blomeyer : ETA Hoffmann as a lawyer. A tribute to his 200th birthday. Lecture given on January 23, 1976. De Gruyter, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-11-007735-3 .

- Hans Günther: ETA Hoffman's time in Berlin as a judge of the chamber judge. About the poet lawyer, especially in the matter of "Turnvater Jahn" - from a colleague who is now a retired judge from the Press and Information Office of the State of Berlin, 1976 (= Berliner Forum; 3/76).

- Bernd Hesse : "Das Fräulein von Scuderi" - ETA Hoffmann's striving for judicial independence. In: Peter Hanau , Jens T. Thau and Harm Peter Westermann (eds.): Against the grain. Festschrift for Klaus Adomeit . Luchterhand, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-472-06876-1 , pp. 275-290.

- Bernd Hesse : Reflection and impact of legal activities in ETA Hoffmann's work. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-58510-8 .

- Alfred Hoffmann: ETA Hoffmann. Life and work of a Prussian judge. Nomos-Verlag, Baden-Baden 1990, ISBN 3-7890-2125-3 .

- Hartmut Mangold: Justice through poetry. Legal conflict situations and their literary design at ETA Hoffmann. German Univ.-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 3-8244-4030-X .

- Rolf Meier: Dialogue between jurisprudence and literature: judicial independence and legal representation in ETA Hoffmann's “Das Fräulein von Scuderi”. Nomos Verlag Gesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1994, ISBN 3-7890-3428-2 .

- Georg Reuchlein: The problem of sanity at ETA Hoffmann and Georg Büchner. On the relationship between literature, psychiatry and justice in the early 19th century. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-8204-8596-1 .

Special literature

- Friedhelm Auhuber: In a distant dark mirror. ETA Hoffmann's poeticization of medicine. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1986, ISBN 3-531-11763-7 .

- Jürgen Glauner: A rediscovered Hoffmann portrait by the hand of Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Müller (1782–1816). online .

- Peter Lachmann: Fly through. ETA Hoffmann in Silesia. A reader. German Cultural Forum for Eastern Europe. Potsdam 2011, ISBN 978-3-936168-49-5 .

- Dennis Lemmler: displaced artists - blood brothers - Serapiontic educators. The family at ETA Hoffmann's plant . Dissertation (Bonn). Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-89528-827-2 .

- Hermann Leupold: ETA Hoffmann ... as a student in Königsberg from 1792 to 1795 . Einst und Jetzt , Volume 36 (1991), pp. 9-79.

- Rainer Lewandowski: ETA Hoffmann and Bamberg. Fiction and reality. About a relationship between life and literature. Franconian Day, Bamberg 1995, ISBN 3-928648-20-9 .

- Jörg Petzel: Devil dolls, burning wigs, magnetizers, jumping and swing masters - ETA Hoffmann in Berlin. Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-945256-36-7 .

- Michael Rohrwasser: Coppelius, Cagliostro and Napoleon. ETA Hoffmann's hidden political gaze. An essay. Stroemfeld Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-87877-379-X .

- Odila Triebel: State Ghosts . Political fictions at ETA Hoffmann. (= Literature and life. NF, 60). Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2003, ISBN 3-412-07802-6 .

- Kenneth B. Woodgate: The fantastic at ETA Hoffmann. (= Helicon. 25). Lang, Frankfurt a. a. 1999, ISBN 3-631-34453-8 .

reception

- Franz Fühmann: Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann , speech in the Academy of the Arts of the GDR, given on the occasion of the 200th birthday of ETA Hoffmann on January 21, 1976; printed in Sinn & Form 1976 (issue 3)

- the same: Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann , a radio lecture given in January 1976; reprinted in Neue Deutsche Literatur 1976 (issue 5)

- the same: epilogue to Klein Zaches called Zinnober , Leipzig (Insel Verlag 1978); Pre-printed in Weimar Articles 1978 (Issue 4)

- Theophile Gautier: Les contes de Hoffmann , Chronique de Paris, August 14, 1836, wikisource

- Ronald Götting: ETA Hoffmann and Italy. (= European university publications; series 1, German language and literature. 1347). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1992, ISBN 3-631-45371-X .

- Andrea Hübener: Kreisler in France: ETA Hoffmann and the French Romantics (Gautier, Nerval, Balzac, Delacroix, Berlioz). Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1606-8 .

- Ute Klein: The productive reception of ETA Hoffmann in France. (= Cologne studies on literary studies. 12). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 2000, ISBN 3-631-36535-7 .

- Sigrid Kohlhof: Franz Fühmann and ETA Hoffmann. Romance reception and cultural criticism in the GDR. (= European university publications. Series 1; German language and literature. 1044). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1988, ISBN 3-8204-0286-1 .

- Volker Pietsch: Split personality in literature and film. On the construction of dissociated identities in the works of ETA Hoffmann and David Lynch. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-58268-8 .

- Dirk Schmidt: The influence of ETA Hoffmann on the work of Edgar Allan Poe. (= Edition Wissenschaft; series comparative literary studies. 2). Tectum, Marburg 1996, ISBN 3-89608-592-1 .

- Walter Scott : On the Supernatural in Fictitious Composition; and particularly on the works of Ernest Theodore William Hoffmann. 1827, In: Ioan Williams (Ed.): Walter Scott: On Novelists and Fiction. London 1968, pp. 312-352 (first in The Foreign Quarterly Review 1, 1827, pp. 60-98).

Web links

- Literature by and about ETA Hoffmann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about ETA Hoffmann in the German Digital Library

- Search for ETA Hoffmann in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- ETA Hoffmann in the Bavarian literature portal (project of the Bavarian State Library )

- Works by ETA Hoffmann at Zeno.org .

- Works by ETA Hoffmann in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Works by ETA Hoffmann in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ETA Hoffmann in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- ETA Hoffmann in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (English)

- Sheet music and audio files from ETA Hoffmann in the International Music Score Library Project

- Works by and about ETA Hoffmann at Open Library

- Hoffmann's works in the literature network

- ETA Hoffmann Archive of the Berlin State Library

- ETA Hoffmann portal of the Berlin State Library

- Digitized autographs, music and drawings by ET A Hoffmann from the holdings of the Bamberg State Library

- ETA Hoffmann Society

- Annotated link collection of the university library of the FU Berlin ( Memento from August 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) ( Ulrich Goerdten )

- Small writings by ETA Hoffmann (e-book by "Im Werden")

- Nutcracker and Mouse King as a picture book based on original drawings by Peter Carl Geissler

- Works by ETA Hoffmann as free audio books at Vorleser.net

- Works by ETA Hoffmann as free audio books at LibriVox

- Nine illustrations for Master Floh by Stefan Mart

- ETA Hoffmann "elixirs of the devil" from the series classic of world literature of BR-alpha

- Entry via ETA Hoffmann on Afrikaans in Europe , a multilingual project of the University of Vienna

Individual evidence

- ↑ That's why ETW Hoffmann is written on his tombstone

- ^ ETA Hoffmann: Life - Work - Effect in the Google book search

- ↑ Detlef Kremer: E. T. A. Hoffmann in his time. In: Kremer (Ed.): E. T. A. Hoffmann , De Gruyter 2010, p. 1

- ↑ Detlef Kremer: E. T. A. Hoffmann in his time. In: Kremer (Ed.): E. T. A. Hoffmann , De Gruyter 2010, p. 2

- ↑ Peter Bekes: Reading key E. T. A. Hoffmann. The Sandman. Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Cf. E. T. A. Hoffmann Life - Work - Effect. In: De Gruyter Lexicon. (Ed.) Detlef Kremer, Göttingen 2010, p. 2.

- ↑ Kremer, Hoffmann, de Gruyter, 2010, p. 3

- ↑ Portrait of Otto Wilhelm Doerffer 1770 Article in the ETA Hoffmann-Gesellschaft eV with further information about the Doerffer family

- ↑ a b Kremer, Hoffmann, de Gruyter 2010, p. 4

- ↑ On the influence of romantic psychiatry and the influence of the Bamberg doctors Marcus and Speyer see Hartmut Steinicke (ed.), E. T. A. Hoffmann, Complete Works in 6 Volumes, Volume II.2 (Elixirs of the Devil), Frankfurt 1988, pp. 545ff

- ↑ a b Marko Milovanovic: "The muse rises from a barrel" - drunkard-poet or poet and drunkard? What E. T. A. Hoffmann actually did in Berlin pubs . In: Critical Edition . No. 1 , 2005, p. 17-19 ( online [PDF; accessed January 29, 2015]).

- ↑ Wilhelm Ettelt, ETA Hoffmann, 1981. Cited in Milovanovic, The Muse rises from a barrel, critical issue 1/2005

- ↑ Kremer, Hoffmann, de Gruyter 2010, p. 5

- ^ Letter of May 7, 1808 to Hippel, quoted in E. T. A. Hoffmann, Der Sandmann, Reclam XL, 2015, Appendix 3.2

- ↑ See Georg Ellinger: The disciplinary proceedings against E. T. A. Hoffmann. According to the files of the Secret State Archives. [With the first printing of the censored passages from Master Flea. ] In: Deutsche Rundschau. 1906, 3rd quarter, volume 128, pp. 79-103. Text archive - Internet Archive

- ↑ Ernst Bäumler, Cupid's poisoned arrow: Cultural history of a secretive illness, 1997, p. 259, quoted from Anja Schonlau Syphilis in the literature: on aesthetics, morality, genius and medicine (1880–2000) , Würzburg, Königshausen and Neumann 2005, p .80

- ↑ Ricarda Schmidt, E. T. A. Hoffmann suffered from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? , Announcements ETA Hoffmann-Gesellschaft

- ^ Deterding, E. T. A. Hoffmann: the great stories and novels, Volume 2, Königshausen and Neumann 2008, p. 87

- ↑ Monument renovations . In: Friedenauer Lokal-Anzeiger . No. 146, June 24, 1905. p. 3.

- ↑ Hartmut Steinecke, E. T. A. Hoffmann in his time, Detlef Kremer (ed.), E. T. A. Hoffmann, De Gruyter 2010, p. 13.

- ↑ Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection: Honorary Graves of the State of Berlin (as of November 2018) (PDF, 413 kB), p. 37 (accessed on April 1, 2019). Recognition and further preservation of graves as honor graves of the State of Berlin (PDF, 205 kB). Berlin House of Representatives, printed matter 17/3105 of July 13, 2016, p. 1 and Annex 2, p. 6 (accessed on April 1, 2019).

- ^ Hans von Müller: E. T. A. Hoffmann in personal and correspondence. His correspondence and the memories of his acquaintances . Collected and explained by Hans von Müller. Second volume: The correspondence (with the exception of the letters to Hippel). Third booklet: Appendices regarding Hoffmann's death and burial, the estate and the bereaved. In addition, corrections and minor additions. With the illustration of the real tombstone erected by Hoffmann's friends in 1822. Published by Gebrüder Paetel (Dr. Georg Paetel), Berlin 1912, p. 543-552 .

- ↑ E. T. A. Hoffmann Archive. Welcome to the E. T. A. Hoffmann Archive. In: staatsbibliothek-berlin.de. Retrieved July 4, 2015 .

- ^ Collection on the history of literature. In: stadtmuseum.de. February 2015, accessed on July 4, 2015 (manuscript title page in picture gallery at the bottom of the page).

- ↑ E. T. A. Hoffmann. (No longer available online.) In: staatsbibliothek-bamberg.de. April 13, 2015, archived from the original on July 5, 2015 ; Retrieved July 4, 2015 .

- ↑ Jochen Hörisch: The bibliophile collection of Carl Georg von Maassen (1880-1940) in the Munich University Library. In: deutschlandfunk.de. April 13, 1998, accessed July 4, 2015 .

- ^ Letter from Grimm to Hofrat Suabedissen, October 19, 1823, cited, for example, in Johannes Harnischfeger, Die Hieroglyphen der Innere Welt: Romantikkritik bei E. T. A. Hoffmann, Westdeutscher Verlag 1988, p. 123

- ↑ Hartmut Steinecke: Commentary. In: E. T. A. Hoffmann: Complete works in seven volumes , Volume 3: Night pieces. Little Zaches. Princess Brambilla. Works 1816–1820. Edited by Hartmut Steinecke with the assistance of Gerhard Allroggen, Frankfurt am Main 2009, p. 949.

- ^ Gunnar Och: Literary anti-Semitism using the example of E. T. A. Hoffmann's story "Die Brautwahl". In: Mark H. Gelber (ed.): Studies on German-Jewish literary and cultural history from the early modern period to the present. Festschrift for Hans-Otto Horch on his 65th birthday. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-484-62006-3 , pp. 57-72

- ^ Bloodletting in Poznan. In: Der Spiegel 42/1965.

- ^ Rudolf Frank: The concealed Hoffmann . In: Frankfurter Zeitung . No. 502 , July 8, 1924.

- ↑ A crazy, confused circle. In: FAZ. November 6, 2010, p. 40.

- ^ BR radio play Pool - Hoffmann, The Serapions Brothers

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hoffmann, ETA |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hoffmann, Ernst Theodor Amadeus; Hoffmann, Ernst Theodor Wilhelm |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German romantic writer, lawyer, composer, music critic, illustrator and caricaturist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 24, 1776 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Königsberg (Prussia) |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 25, 1822 |

| Place of death | Berlin |