Henry II (HRR)

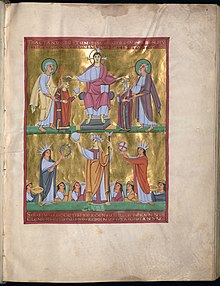

Miniature from the sacramentary of Heinrich II, today in the Bavarian State Library in Munich (Clm 4456, fol. 11r)

Heinrich II. (* May 6, 973 or 978 in Abbach or Hildesheim ; † July 13, 1024 in Grone ), saint (since 1146), from the noble family of Ottonians , was Heinrich IV. From 995 to 1004 and again from 1009 Until 1017 Duke of Bavaria , from 1002 to 1024 King of Eastern Franconia (regnum Francorum orientalium) , from 1004 to 1024 King of Italy and from 1014 to 1024 Roman-German Emperor .

As the son of the Bavarian Duke Heinrich II , known as "the brawler", and his wife Gisela of Burgundy , he was the great-grandson of Heinrich I and thus came from the Bavarian branch of the Ottonians. On June 7, 1002 he was crowned King of East Franconia and on May 14, 1004 in Pavia he was crowned King of Imperial Italy . On February 14, 1014, Pope Benedict VIII crowned him emperor. Heinrich II was married to Kunigunde of Luxembourg . The marriage remained childless, making Henry II the last emperor of the Otton family. Pope Eugene III. canonized him in 1146, some later historians therefore gave him the nickname "the saint". His feast day ( Protestant and Roman Catholic ) is the day of his death, July 13th.

Unlike his predecessor Otto III. Heinrich concentrated on the realm north of the Alps. His main focus was on the wars against the Polish ruler Bolesław I. Chrobry . The three Italian trains primarily served to acquire the dignity of emperor and to establish his rule in this part of the empire. Henry's reign is seen as a time of intensification and centralization of royal rule. He consolidated the empire through even closer personal and political ties with the church. Donations and new foundations strengthened the dioceses in the empire in particular as pillars of royal rule. In 1007 Heinrich founded the diocese of Bamberg . The king increasingly used the services of the churches ( servitium regis ) . He also promoted the beginning monastery reform.

The chronicle of Thietmar von Merseburg , who was appointed Bishop of Merseburg by Heinrich in 1009, is considered to be one of the most important sources on Heinrich II and is regarded as a leading tradition.

Life

Early years

Under Heinrich II's great-grandfather Heinrich I from the Liudolfinger family - unlike the Carolingians in the 9th century - not all sons were elevated to kings, but only the eldest son Otto I. The younger son of the same name , the grandfather Henry II had to renounce royal rule in 936 at the latest and later settled for the Duchy of Bavaria. The Bavarian line of the Liudolfinger was excluded from the rule. Heinrich der Zänker , the father of the future emperor Heinrich II., Tried to take a position like a king. After many years of conflict with Emperor Otto II , he was imprisoned indefinitely, initially in Ingelheim and then from April 978 in Utrecht . Heinrich lived in Hildesheim while his father was in custody . As a child he was given to Bishop Abraham von Freising for education and then trained in the Hildesheim Cathedral School for the clergy. Perhaps this happened on the instructions of Otto II, who wanted to eliminate the son of his opponent from any participation in the royal power. Heinrich learned to read, write and the Latin language at one of the best schools in the empire. In Regensburg he finished his training from 985 under Bishop Wolfgang . During this time he was also influenced by Abbot Ramwold of St. Emmeram , who, like the bishop himself, was a supporter of the monastery reform of Gorze .

After the death of Otto II, Heinrich der Zänker was released from prison. His efforts to win the royal crown failed, but he was able to regain power in the Duchy of Bavaria in 985. His son was in a document of Otto III. from the year 994 referred to as co-duke (condux) . After the death of his father in late August 995, the Duchy of Bavaria fell to Heinrich.

In the year 1000 or shortly before, Heinrich Kunigunde married from the ruling family of the Counts of Luxembourg . Through his connection with this noble house, Heinrich strengthened his position in the Rhenish-Lorraine region.

king

Election to king (1002)

Despite his origins, Heinrich's right to the throne after the death of Otto III. controversial in Italy in January 1002. The king, who died young, had left no instructions in the event of his death, and there were no regulations regarding the succession to the throne of a side line of the ruling house. In addition to Heinrich, Margrave Ekkehard von Meißen and Hermann von Schwaben also raised claims for the successor. Ekkehard could not count on undivided support for his candidacy in Saxony; he intended to win further approval for his candidacy in Lorraine , but was slain in the Palatinate Pöhlde in April 1002 by Count Siegfried von Northeim.

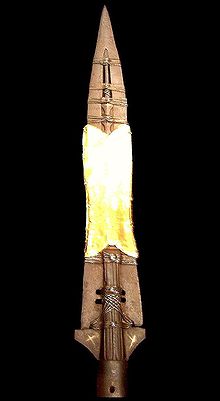

In order to substantiate his claims, Heinrich received the entourage of Otto III's corpse, which had been led across the Alps. in Polling near Weilheim in Upper Bavaria and had its entrails buried in the St. Ulrich and Afra monastery in Augsburg. This was the typical behavior of a legitimate successor who took care of the salvation of his predecessor. He then forced Archbishop Heribert of Cologne to hand over the ruler's insignia to him. However, the Holy Lance , the most important relic of the empire at the time, was missing . Heribert had sent them ahead, probably out of mistrust, since he wanted his relative, the Duke of Swabia, Hermann II , to be elected king. In order to force the surrender of the lance, Heinrich imprisoned the archbishop and later his brother, the Würzburg bishop Heinrich . Almost all companions of the funeral procession, who are probably confidants of Otto III. acted, could not be won over to the succession of the Bavarian duke. A few weeks later, at the emperor's solemn burial in the imperial cathedral in Aachen , these men confirmed their refusal, taking the view that Heinrich was unsuitable for kingship for many reasons. The specific reservations are unknown. They are probably related to the disputes that Heinrich's ancestors had with the members of the ruling line of the Ottonians.

Heinrich decided to take an unusual step: he was elected king in Mainz by his Bavarian and Franconian supporters and anointed and crowned by the Archbishop of Mainz Willigis in Mainz Cathedral on June 7, 1002 . This was the correct coronator (“royal crown”), but all other accompanying circumstances deviated from the usual customs (consuetudines) : the place of choice was unusual, the enthronement on the Aachen chair of Charlemagne was omitted and from a “election of all the greats Rich “could not be a question at first. The decision was finally made at the end of July through the so-called by-election in Merseburg, in which Heinrich had to justify himself to the Saxons for appearing in royal regalia and appearing as ruler. It was only after he had promised to respect the old Saxon law that the Saxon Duke Bernhard presented him with the Holy Lance and entrusted him with the care of the empire.

The king's choice of 1002 has been discussed frequently and controversially in medieval studies since the 1970s. There is a dispute over the question of whether it is a matter of a free election of the great (according to Walter Schlesinger ), or whether all candidates with Otto III. were related and for the succession to the throne the candidate's right of inheritance (according to Armin Wolf and Eduard Hlawitschka ) was decisive. According to Steffen Patzold , the discussion about abstract legal norms is based on false assumptions. It was not the kind of descent, but character traits such as piety, humility, wisdom and justice that qualified Heinrich. In a society largely characterized by orality, there was a lack of written norms for the legal process of electing a king. The only conceivable norm, habit, was not applicable, because the last comparable case of a king who died childless was over 80 years ago. Heinrich's recognition was the result of a large number of disorganized conversations and gatherings. In a reply to Patzold, Hlawitschka again identified the right of inheritance as the standard for assessing claims to the throne in the sources.

Taking office

Heinrich himself stated that he was related to Otto III in a royal document for Strasbourg. and stated their familiarity, cultivated from childhood, as the reason that convinced most princes to give him the choice (electio) and hereditary succession (hereditaria successio) without division. The following month-long king ride through large parts of the empire can therefore be seen as an attempt to obtain general confirmation of the election. Such a ride around was common among the Merovingians , but afterwards it had become out of custom. Heinrich's tour led through Thuringia, Saxony, Lower Lorraine, Swabia and Bavaria to Upper Lorraine. With the revival of this custom, royal authority was to be expanded over the entire empire.

Heinrich already had to face the first armed conflicts with some of the greats during the tour. Shortly after the beginning of his rule, a war began with Duke Hermann II of Swabia, who had also had hopes for the throne. There was no direct fighting between the duke and the new king; however, Heinrich devastated the possessions of Hermann, who in turn fought against Heinrich's supporters in the Swabian nobility. When there was no sign of military success, Heinrich went to Saxony, where he received homage from the greats in Merseburg . He then moved to Paderborn , where his wife was anointed and crowned queen by Archbishop Willigis of Mainz on August 10th. In Duisburg on August 18, the bishops of Liège and Cambrai paid homage to the new king. Above all, however, he also gained recognition from the Archbishop of Cologne, Heribert . On September 8th, the feast of the birth of the Virgin Mary , Heinrich was paid homage to the secular great Lotharingia in Aachen , who placed him on the throne of Charlemagne and Otto the Great and symbolically concluded his rule. His tour ended in Diedenhofen in Lorraine , where the first big farm day took place on January 15, 1003.

Hermann II submitted to Bruchsal on October 1, 1002. The new hierarchy in the empire was illustrated by the publicly staged submission ritual. Thanks to this demonstrative gesture of subordination, he was allowed to keep his duchy, but had to give up his capital Strasbourg and transfer his goods and bases there to the bishop. After Hermann's death in May 1003, the king took over the government of the Duchy of Swabia for the still underage son of the duke .

Heinrich also had to assert himself against Margrave Heinrich von Schweinfurt , to whom he had promised the Duchy of Bavaria for his support in the election of the king. After the election, Heinrich II is said to have broken this promise by pointing out that he could not pre-empt the free election in Bavaria. The conflict with the margrave was amicably settled through a ritual of submission (deditio) and brief imprisonment. Heinrich awarded the Duchy of Bavaria in 1004 to his brother-in-law Heinrich V of the Lützelburg family . This was the first time that an alien family without their own real estate acquired the Bavarian duchy. When Duke Heinrich V rose up against the king a few years later because of the curtailment of his power base together with his brothers, Heinrich II. Gathered the aristocracy of Bavaria in Regensburg and got him "partly through promises, partly through threats" to support the Give up Duke. Duke Heinrich V was deposed in 1009.

Henry becomes King of Italy (1004)

In 1004 Heinrich led a campaign against the Margrave Arduin of Ivrea . He murdered Bishop Peter von Vercelli in March 997 and was condemned in January 999 by a Roman synod in the presence of the Pope and Emperor. Nevertheless, on February 15, 1002, only three weeks after the death of Otto III, he was made King of Italy (rex Italiae) .

Other Lombard bishops, including Leo von Vercelli , appealed to Henry II for help. They had been curtailed several times by Arduin in their power of disposal over the church property. After initial hesitation, Heinrich prepared for his first Italian train in 1004. Previously, an army under Otto von Worms , Duke of Carinthia , had suffered a heavy defeat at the Veronese Klausen in January 1003 .

The army of the first Italian campaign consisted almost exclusively of troops from the Bavarian clergy and nobility. Heinrich gathered his troops in Augsburg and moved over the Brenner to Trient . In view of the uncertain situation in Italy, Heinrich intensified the help in prayer. In the Trento Episcopal Church he entered into a prayer fraternity with his spiritual and secular greats as well as the northern Italian bishops . Archbishop Arnulf II crowned Henry King of Italy (rex Langobardorum) on May 14, 1004 in Pavia . The ceremony was performed in the Church of San Michele , where Arduin had been crowned king two years earlier. Since Otto I, none of the Ottonian rulers had been crowned King of Italy. The following night the citizens of Pavias attacked Heinrich and his companions. These in turn set fire to houses in Pavia to alert the distant troops. The insurrection could only be suppressed with difficulty. Heinrich's brother-in-law Giselbert , Queen Kunigunde's older brother, was so badly injured in the attack that he died a few days later.

After Heinrich had received homage from other Lombards on a court day in Pontelungo , he withdrew from Italy at the beginning of June 1004 without having achieved the imperial crown or defeating Arduin. Italy was left to its own devices for a whole decade. However, evidence of Arduin's ruling activities during this period is rare.

Conflict with Bolesław Chrobry

When he was elected king, Henry II came into conflict with the Polish ruler, the Piast Bolesław I. Chrobry. The dispute can be divided into three phases based on the peace treaties of Posen 1005, Merseburg 1013 and Bautzen 1018.

The death of Otto III, the assassination of the candidate for the throne, Margrave Ekkehard von Meißen, as well as Henry's reign led to a change in the ruling association. Heinrich's father's earlier Saxon opponents were initially on the side of Ekkehard, after whose death they sought support from Bolesław. As a Bavarian duke, Heinrich had, for his part, maintained close relationships with the Bohemian Přemyslids , who traditionally were opponents of the Polish Piasts. Bolesław was one of the most important followers of Otto III. This had given him special honor in Gnesen in the year 1000. Whether it is a king's uprising ( Johannes Fried ) or a friendship alliance ( Gerd Althoff ) is controversial in recent research. By raising the rank in Gniezno, Bolesław was likely to have felt at least equal to, if not superior, to the Bavarian Duke Heinrich. Under the new ruler Heinrich II. Boleslaw lost influence. Future attempts at agreement should always fail because of the question of equality or subordination.

In the by-election of Henry II in Merseburg in 1002, Bolesław, as a relative of Margrave Ekkehard, was unable to assert his claim to the whole of the Mark of Meissen, although he offered Heinrich a lot of money in return. He only received the Lausitz and Milzenerland . So he left Merseburg disappointed. The core of the conflict, however, was not just a territorial dispute over the legacy of Ekkehard von Meissen. Knut Görich explains the conflict “with political ties and traditions” from Heinrich's time as Bavarian Duke - he relied on Bolesław's opponents in the Saxon nobility - and with the compulsion to enforce the royal honor . Stefan Weinfurter sees the drive for the long armed conflicts in similar concepts of power. Both pursued "the idea of a church kingdom on earth". Both rulers considered themselves chosen by God; they wanted to align their rule with the commandments of God and convey them to their people. From an archaeological point of view, Joachim Henning recognizes the cause of the conflict in the "efforts to redistribute access to the developing economic and trade scene in the east". Both rulers claimed access to the trade route running from the Rhineland via Erfurt, Meissen, Krakow to Kiev and further to Central Asia, the importance of which had increased significantly. Henning cites the emergence of a new type of castle as the most important evidence for his thesis. This was intended to fill important points in supraregional long-distance trade.

Bolesław was attacked when leaving Merseburg. He owed his salvation only to the intervention of Duke Bernhard of Saxony and Margrave Heinrich von Schweinfurt. After Thietmar the motive was for the attack that Bolesław accompanied the royal armed entered and the, in the opinion of some noble honor had hurt (honor) of the king. Thietmar claims that the attack took place “without the king's instructions and knowledge”, but shows that not all contemporaries were of this opinion. Bolesław received no satisfaction from Heinrich for the attack. On the way back, the Pole had Strehla Castle burned down, opening the feud against the king. Bolesław found support from Margrave Heinrich von Schweinfurt, to whom the king refused the Bavarian duchy despite acceptance. Heinrich concluded an alliance with the pagan Liutizen at Easter 1003 in Quedlinburg . This alliance with pagan enemies against the Christian Poles aroused the most violent indignation among the Saxons. It is related to the traditionally good Bavarian-Bohemian relations and the alliances between the Bohemians and Liutizen. Bolesław enjoyed considerable sympathy among the Saxon nobility. The Saxon aristocrats supported Heinrich reluctantly on several occasions; during his absence, military action against the Pole could not be carried out.

Thietmar took a clear stand for Heinrich and against Bolesław in the conflict. He attributed the support of Saxon nobles for Bolesław almost always to bribery. Heinrich's measures against alleged or actual supporters of Bolesław make clear the extent of their assistance to the Poles. Heinrich held the Margrave Gunzelin von Meißen in prison for over seven years. Other Saxon greats were punished by confiscating goods and withdrawing their royal favor. Heinrich tried to expand his room for maneuver in disputes within the nobility by obtaining reliable followers or by weakening supporters of Bolesław by awarding offices and fiefs. Heinrich tried to increase his room for maneuver by drawing on the episcopate. In 1005, together with his wife and numerous Saxon bishops as well as Duke Bernhard of Saxony, he formed the Dortmund Totenbund , whereby all participants committed to reciprocal prayer, fasting and charitable services in the event of death. Heinrich was the only Liudolfingian ruler who formed a prayer fraternity with bishops at a synod. With this prayer fraternity he wanted to secure the support of the bishops for the upcoming procession against Bolesław. In the occupation of the bishopric, Thietmar in Merseburg , Wigger in Verden and Eilward in Meißen, confidants of the king were preferred. In return, the Saxon bishops were used intensively for the army succession against Bolesław.

Peace of Poznan (1005)

After the confusion of the throne in Bohemia, Bolesław had gained power there, but refused to accept the ducal dignity as a fief from Henry II. To redeem this disgrace, Heinrich moved with his army to the fortress of Poznan in 1005. The conflict was settled through mediators. Bolesław's ally, Margrave Heinrich von Schweinfurt, had to undergo a ritual of submission (deditio) barefoot and in poor clothes and was imprisoned for a short time. Bolesław, on the other hand, did not perform this demonstrative subordination. Since a meeting after a conflict was only possible if the loser gave satisfaction for the injured honor of the king by public submission, a personal meeting between Heinrich and Bolesław did not take place. Rather, mediators, including Archbishop Tagino von Magdeburg, swore peace with Bolesław before Posen, but in the absence of the king. For Heinrich this peace was no public satisfaction for the honor previously injured by Bolesław .

Peace of Merseburg (1013)

Heinrich needed some rest in the northern part of the empire for the planned trip to Rome for the coronation of the emperor. Bolesław did not find the compensation he was aiming at inconvenient, as he had to deal with problems in the Kievan Rus . In 1013 peace negotiations began on a farm day in Merseburg. Bolesław took the oath of allegiance and received the Lausitz and Milzenerland as a fief. Bolesław carried the sword when Heinrich went to the Merseburg church under the crown. Whether the sword bearer service is a special honor ( Knut Görich ) or a sign of demonstrative subordination ( Gerd Althoff ) is controversial in recent research. In Merseburg the already in Gnesen between Otto III. and Bolesław consummated the prearranged marriage. Richeza , a relative of Heinrich from the Ezzone family , married Mieszko II , the son of Bolesław. The choice of location with Merseburg was also intended to symbolically erase the insults in historical memory that Bolesław suffered in 1002 at this location. At the same time, with the choice of location, the recognition of Heinrich's superior position should be made clear. Apparently, however, Bolesław did not have to perform a ritual submission (deditio) to Henry II.

Emperor

Imperial coronation in Rome (1014)

Similar to Heinrich's predecessors, popes loyal to the emperor could not hold out in Rome and were ousted by representatives of urban Roman aristocratic groups. Such representatives of the Roman nobility were John XVII. who officiated in 1003, John XVIII. (1003-1009) and Sergius IV. (1009-1012). They were all either relatives of the Roman Patricius John II. Crescentius or at least heavily dependent on him. John II. Crescentius prevented meetings between the respective pope and the king on several occasions.

After Pope Sergius IV and John, who supported him, died shortly after one another in May 1012, the Tusculan counts , the rivals of the Crescentians , placed their head of the family Benedict VIII on the papal throne. Benedict won the following short schism with the antipope Gregor (VI.) By confirming the establishment of the Bamberg diocese and offering Heinrich the dignity of emperor.

In October 1013 Heinrich set out with an army from Augsburg to Italy after he had given himself the necessary freedom through the Peace of Merseburg. His wife Kunigunde and a number of clerics accompanied him. Other bishops and abbots joined him in Pavia. Arduin, who still ruled parts of northern Italy, avoided a military conflict and offered the king to lay down his crown if only his county would be left to him. Heinrich refused and continued his march to Rome for the imperial coronation.

On February 14, 1014, Benedict VIII crowned him Emperor and his wife Empress in the Basilica of St. Peter . The Pope presented him with a golden ball adorned with a cross. This is the first evidence of the use of a " Reichsapfel ". Such an orb later became an integral part of the imperial insignia .

Subsequently, a synod was held in Rome, chaired by the emperor and the pope, at which five bishops were deposed and decrees against simony and for the chastity of clergy were issued; In addition, the return of alienated church property was demanded. Shortly afterwards the emperor moved north again, where he raised the monastery in Bobbio to the diocese . He left Rome to the Pope and the noble families who supported them; Little is known of royal interference in the conditions of Italy and the Papal States. Rather, he celebrated Easter in Pavia and Pentecost in Bamberg. Even the conflict with Arduin was not resolved. But Arduin soon fell seriously ill and probably withdrew to the Fruttuaria monastery in the face of death . He died on December 14, 1015. He was the last national king of Italy before Victor Emmanuel II , who became Italian king in 1861.

Peace of Bautzen (1018)

Bolesław had not given the promised support for Heinrichs Romzug 1013/14. His participation would have made a demonstrative subordination to the future emperor obvious. Heinrich demanded a justification for the violation of the duty to help, which should be done at Easter 1015 on a farm day in Merseburg. Bolesław was supposed to appear barefoot and dressed as a penitent, throw himself to the ground and humbly ask for the ruler's grace. Heinrich took Bolesław's son Mieszko II hostage and kept him in custody for a long time in order to force the appearance of the Polish ruler. Only after urgent demands from the Saxon nobles did he deliver Mieszko to Bolesław in November 1014. Bolesław interpreted the long imprisonment as a demonstration of Heinrich's hostility; he refused to comply with the summons on a farm day. Heinrich led war campaigns against the Poles in vain in the summer of 1015 and for the last time in the summer of 1017. The imperial troops suffered heavy losses and turned back. At no point in the conflict with Bolesław did Heinrich lose more Saxon nobles in battle than in 1015. The lack of commitment by the Saxon nobility prevented Heinrich's campaigns from being successful. The Saxon princes initiated peace negotiations. For Bolesław, the conditions in the Kievan Rus were again the decisive motivation for a peace agreement. On January 30, 1018 Archbishop Gero von Magdeburg , Bishop Arnulf von Halberstadt , Margrave Hermann von Meißen, Count Dietrich and the Imperial Chamberlain in Bautzen swore a lasting peace between Bolesław and Heinrich, without the two rulers personally meeting, and peace confirmed demonstratively. Both sides held hostages, so that the equality of the parties became clear.

Acquisition of Burgundy

Heinrich was more successful in the west of the empire, especially in the Kingdom of Burgundy . Through his mother Gisela, he was a nephew of the childless King Rudolf III. of Burgundy. The two rulers met for the first time in 1006. Rudolf den Ottonen promised the inheritance of his kingdom and gave him Basel as a kind of pledge. From then on, the city gave Heinrich access to the Kingdom of Burgundy. At meetings in Strasbourg in May 1016 and in Mainz in February 1018, Rudolf confirmed his recognition of Heinrich's claim to inheritance. However, Heinrich died in 1024 during Rudolf's lifetime. Therefore, only his successor Konrad II. 1032/33 took over the Burgundian inheritance.

Campaign against Byzantium

Heinrich's involvement in Italy and his coronation as emperor inevitably brought him into conflict with Byzantium , which endeavored to reassert its old claims to power in southern Italy. Emperor Basil II had the administrative system systematically expanded and fortresses and castles strengthened. The princes Pandulf of Capua and Waimar of Salerno had joined the Byzantine rule.

In view of the Byzantine successes in southern Italy, which led to the restoration of Byzantine rule as far as central Italy, Pope Benedict VIII decided to take an unusual step in 1020: he visited the emperor north of the Alps and conferred with him in Bamberg and Fulda . No Pope had visited the emperor north of the Alps since 833. In Bamberg, in addition to the Pope and a large number of secular and spiritual imperial princes, Meles von Bari , the leader of an Apulian uprising against Byzantine rule, and his Norman comrade Rudolf were present. They celebrated Easter together. Meles presented the emperor with a precious gift, a starry cloak , as a symbol of the all-encompassing imperial claim to world domination. Thereupon Heinrich conferred Meles the dignity of Duke of Apulia, but a few days later, on April 23, 1020, Meles died.

In view of the threatening situation, the Pope managed to get Heinrich to set off again on an Italian expedition in autumn 1021. Even before his third move to Italy, he occupied the two most important bishoprics in the empire with two clerics of Bavarian origin, Aribo for Mainz and Pilgrim for Cologne. Three army groups, which in addition to the emperor commanded the bishops Pilgrim of Cologne and Poppo of Aquileia , moved to southern Italy. Pandulf of Capua, Waimar of Salerno and other Italian princes surrendered to pilgrims. Pandulf was sentenced to death by the royal court and was supposed to be drowned in public in Bari . At the intercession of Pilgrim, Heinrich ordered his exile in chains to the empire north of the Alps. Nobles were usually not placed in chains in the Ottonian period.

Heinrich moved with an army to northern Apulia, where he besieged the Byzantine fortress of Troia for a long time without success . The residents of the city twice sent their children with a priest to the emperor to ask for forgiveness. Only the second time did Heinrich Milde exercise. The inhabitants had to pull down their city walls a little, but were allowed to rebuild them after taking an oath of loyalty and being held hostage. However, the Byzantine troops could not be forced into battle. Heinrich had to turn back, and his army, weakened by illness, suffered great losses. But even Basil II could not benefit from Henry's retreat, he died in 1025.

Death and succession

In the last years of his life, Heinrich's rule was spared major conflicts. In 1023 he renewed the friendship alliance made in 1006 with King Robert II of West Franconia . At the beginning of 1024, Heinrich had to take a break of almost three months because of an illness in Bamberg. In April 1024 he was able to celebrate Easter again in Magdeburg . After the Easter celebrations he left, but then had to stay in Goslar for two months because of a serious illness . A violent relapse forced him to stay in the Palatinate Grona near Göttingen , where he finally died on July 13, 1024 of a chronic painful stone disease. He found his grave in Bamberg Cathedral , where he may share the high grave created by Tilman Riemenschneider around 1500 with Empress Kunigunde. Since the marriage remained childless, the rule of the Ottonians ended with his death. Henry II left an empire with no major unsolved problems.

At the beginning of September, the greats of the empire met in Kamba to negotiate as broad a consensus as possible for a new king. The Salian Conrad II finally prevailed as the new ruler . Konrad clearly distinguished himself from his predecessor. He never derived his kingship from him. However, in many areas of royal rule, Konrad II oriented himself towards Heinrich II. The first Salier took over the staff of the court orchestra and the royal chancellery, continued the principles of church policy as well as Italian policy and the imperial idea and completed the acquisition initiated by Heinrich II Burgundy.

Heinrich's politics

For a long time Heinrich was regarded as a tough realpolitician, who in the royal metal bull the motto of his predecessor Otto III. "Restoration of the Roman Empire" ( Renovatio imperii Romanorum ) replaced by the slogan "Restoration of the Frankish royal rule" (Renovatio regni Francorum) and abandoned the Rome-centered imperial ideology. Heinrich had turned away from Otto's idealistic projects in Italy and pursued a realpolitik that served German interests in the East. The friendship and cooperation with Bolesław Chrobry was replaced by enmity - made concrete in the protracted so-called Polish wars. Older research believed that it felt for the first time "the ice breeze of national interest politics" in the activities of Henry II.

On the other hand, Knut Görich (1993) referred to the numerical ratio of the bulleted, lead bulled documents of Otto III. and Henry II pointed out. 23 bulls from Otto are compared to only four bulls from Heinrich. The Frankenbulle (Renovatio regni Francorum) was only used on current occasions after it was successfully implemented in the empire in January and February 1003 and was used alongside the traditional wax seals. A short time later, the use of the Frankenbulle was abandoned.

Court and rulership practice

Until well into the 14th century, medieval royal rule in the empire was exercised through outpatient rulership practice. Heinrich had to travel through the empire and thereby give his rule validity and authority. Most often he stayed in Merseburg (26), Magdeburg (18) and Bamberg (16). Based on the fundamental studies by Roderich Schmidt and Eckhard Müller-Mertens , Hagen Keller (1982) noted an essential change: unlike the three Ottonians, the rule of the king had increased since around 1000 due to “the periodic presence of the court in all parts of the empire ”. In more recent mediaeval studies, long-term spatial policy concepts for kings in the 10th and 11th centuries were questioned. The discussion on this is still ongoing. In contrast to the study by Keller on the integration of the southern German duchies under Heinrich II, Steffen Patzold (2012) viewed Swabia as the edge of the empire.

The term “ court ” can be understood as “presence with the ruler”. The most important parts of the court were the chancellery and the court chapel . The office was responsible for issuing the certificates. A total of 509 documents from Heinrich's 22-year rule have been preserved. He was one of the few rulers of his time who dictated documents himself. Gerd Althoff has registered an abundance of Ottonian documents "as a motive for the gift of one's own salvation or that of another person". According to Michael Borgolte , the share with the hope of salvation is "more than two thirds of the total stock" in Heinrich II's diplomas . Of the 64 bishops raised by Heinrich, 24 had previously been active in the court chapel.

Italian policy

Heinrich did not continue the Italian policy of his Ottonian predecessors. Compared to them, he was in Italy for a short time. He even took more than a decade before he drove the Italian rival king Arduin of Ivrea out of his rule. The reasons for this have not yet been clarified. According to Stephan Freund , Heinrich had a well-functioning information network that supplied him with news from Rome and Italy. The problems of his Ottonian predecessors in Italy also made a long-term commitment south of the Alps seem unpromising. According to Stefan Weinfurter, the "stronger penetration inward [...] undertaken by Heinrich can also have resulted in the endeavor for a sharper demarcation from the outside". According to Weinfurter, Heinrich's idea of Moses' kingship may also have been decisive. Since Heinrich derived the legitimation of his rule from the biblical-Mosaic kingship, the empire was of less importance to him.

Church politics

In particular, when it comes to Heinrich's relationship to the Church, the judgments in modern research differ. It cannot be decided with certainty whether a religious, church reform goal or a political power calculation was decisive for the royal action.

As unsolved church problems, Heinrich took over from Otto III. the question of the re-establishment of the diocese of Merseburg and the so-called "Gandersheim dispute", which was conducted over the question of whether the Gandersheim monastery belongs to the Hildesheim or the Mainz diocese .

In the Merseburg question, Archbishop Giselher von Magdeburg had previously for several years the efforts of Otto III. and numerous synods resisted to induce him to restore the Merseburg bishopric. When Giselher died in 1004, Heinrich succeeded his candidate Tagino , which enabled him to re-establish the diocese of Merseburg. Heinrich showed similar consistency in settling the Gandersheim dispute by getting Willigis of Mainz and Bernward of Hildesheim to accept the verdict of a Christmas synod in Pöhlde in 1006. This decision fell in favor of Bernwards and ended the dispute for the reign of Henry II.

Heinrich fought the marriages with close relatives, which were suspect from a church perspective, throughout his reign. For Karl Ubl, the time of Heinrich II marked “the last climax of the state prosecution of incest offenses”. In his time the prohibition of incest was extended to the 7th degree of canonical counting. Already at the first great imperial synod in Diedenhofen on January 15, 1003, he criticized the marriage of Salier Konrad of Carinthia with the Konradiness Mathilde as being close. In March 1018, a synod chaired by the Archbishop of Mainz, Erkanbald, banned Count Otto von Hammerstein because of his marriage, which was not allowed under canon law. The count began a feud against the archbishop, provoking Heinrich's intervention. In September 1020 Heinrich besieged Hammerstein Castle . Count Otto had to surrender. The couple continued to live together and were excommunicated again because of this. Otto's wife Irmingard turned to Pope Benedict VIII to be able to continue their marriage. Heinrich's successor, Konrad II, prohibited the Archbishop of Mainz from pursuing the matter. According to Hein H. Jongbloed, Heinrich ran the Hammerstein marriage process for political reasons. In a scheming and vengeful manner, he tried to thwart possible claims of Ezzonen Liudolf , a grandson of Otto II, on his successor through the marriage process . The king's intention was to exclude the descendants of Otto II from the rule. Liudolf was Otto von Hammerstein's son-in-law and was therefore affected by the question of whether his wife came from a lawful marriage. Eduard Hlawitschka, on the other hand, does not see Heinrich as the decisive force in the fight against the Hammerstein marriage. The EZZones were also not particularly disadvantaged.

Relationship to the bishops and episcopal churches

Under Henry II, counties were increasingly transferred to bishops. The extensive county awards did not strengthen the position of the church in relation to the empire. On the contrary, Heinrich derived the right from his special support for the monasteries and bishops' churches to demand special services from them. In his documents he expressed this claim twice: "If you are given more, more is required of you." The monasteries should be obliged through the numerous donations and privileges to be more involved in the service of the Reich. But Heinrich not only ruled the church, he also ruled the empire through the church. In Saxony he tried to expand his scope of action by supporting the episcopate and at the same time drawing on secular tasks. He ruled mainly with the help of the bishops. The chronicler Thietmar uses the terms simpnista (official colleague) and coepiscopus (co-bishop) to describe the very special relationship of trust between Heinrich and the bishops, which no other medieval ruler had of this intensity. The synods , which Heinrich convened more often than his predecessors, were of particular importance for the close cooperation between the king and bishops . The synods gave the king the opportunity to "demonstrate his own prominent position as the Lord's anointed and thus his closeness to the highest clergy." 15 meetings are documented at which the king conferred with his imperial bishops. Secular and ecclesiastical affairs were scarcely distinguished and were negotiated equally at synods.

With this integration, Heinrich strengthened the role of the high clergy as a pillar of the empire and at the same time increased his influence in church politics. In return, the monasteries and episcopal churches had to pay for the maintenance of the emperor and his entourage on his travels. In contrast to his Ottonian predecessors, Heinrich and his entourage settled more in the episcopal cities and less in the royal palaces. They were increasingly burdened with the so-called guest obligation . In addition, the church rulers had to provide a large part of the imperial army. In most of Heinrich's campaigns, the clergy princes made up the largest contingent of troops.

Like his predecessors, Heinrich held on to the imperial right of appointment ( investiture ) of the bishops and also disregarded the securitized rights of the clergy. In the event of contradiction, he enforced his will by force. He filled most of the vacancies that arose during his reign with clerics from his immediate surroundings. All of his chancellors received a diocese from him. They were men loyal to the kingdom and the kingdom to whom he entrusted the dioceses and abbeys. His personnel policy decisions brought forth important personalities such as the archbishops Aribo of Mainz , Pilgrim of Cologne , Poppo of Trier and Unwan of Bremen and the bishops Godehard of Hildesheim , Meinwerk of Paderborn and Thietmar von Merseburg (the chroniclers).

Foundation of the Bamberg diocese (1007) and storage of the memoria

To secure his memoria , Heinrich founded the Bamberg diocese in 1007 . He is said to have loved Bamberg Castle in such a unique way that he gave it to his wife Kunigunde as a morning gift (dos) . From the first day of his kingship, Heinrich worked towards the establishment of a diocese in Bamberg and immediately began building a new church that had two crypts and could soon be completed. When the diocese was actually founded, considerable resistance from the diocese of Würzburg had to be overcome, as the new diocese was to comprise around a quarter of this diocese and, from 1016, northern parts of the Eichstätter Sprengels .

After a long dispute, a consensus was found between the bishops at a synod in Frankfurt on November 1, 1007. Heinrich was able to establish the diocese of Bamberg through repeated prostration ( prostration ) in front of the assembled bishops. Every time Heinrich feared a decision against him, he threw himself to the ground with his whole body. With this public humiliation he achieved the approval of the bishops for the foundation. Heinrich von Würzburg , who had hoped to be elevated to archbishopric in return for the cession of large areas to the new diocese, did not appear at the synod, he was represented by his chaplain Berengar. The intention of the king to “make God his heir” and to dedicate the diocese to his memoria is sufficiently attested. He “made God his heir” (ut deum sibi heredem eligeret) , is attributed to the emperor as a motive in the Frankfurt synodal resolution on the establishment of the diocese. The protocol added Henry's piety and his sense of duty to the people (ut in deum erat credulus et in homines pius) and the conversion of the Slavs (ut et paganismus Sclavorum destrueretur) as further motives . With the Slav mission , a classic motif of Ottonian politics is addressed. The extent to which Bamberg was or was not a second “center of the early Slav mission” alongside Magdeburg is being discussed. According to Joachim Ehlers , the Slav mission cannot have played an essential role, since only the relatively small pagan ethnic group of the Regnitz Slavs was affected.

According to Thietmar's report, the motive of “making God his heir” reappeared a few years later. Heinrich announced at a synod in 1007 that he had given up hope of having children: "For the sake of future retribution, I have chosen Christ as my heir, because I can no longer hope for descendants." Heinrich was convinced that he had his kingship with everything that went with it, received directly from God. In his understanding, he could only have passed it on to a son. In the absence of this inheritance, kingship reverted to the heavenly King Christ.

Numerous empire-wide donations by the king ensured the new diocese rich property from the beginning. The diocese received manors in the Nordgau , around Regensburg, around Salzburg and in Upper and Lower Austria as well as various forests and villications , property in Carinthia and Styria , as well as the Swabian ducal monastery Stein am Rhein , the palatinate monastery for the old chapel in Regensburg, and several women's convents such as Kitzingen am Main , Bergen near Neuburg , Gengenbach in Ortenau , Schuttern , the Haslach Abbey in Alsace and important royal places from the Carolingian era such as Hallstadt and Forchheim . Heinrich's previous center in Regensburg faded into the background. After 1007 his stay there can only be verified once. As the first bishop of Bamberg, Heinrich appointed his chancellor Eberhard , who was also archchancellor of Italy from 1013 to 1024. Eberhard was consecrated on the same day.

The childlessness of the king made special efforts of Heinrich and Kunigunde necessary to secure their memoria. In addition to establishing Bamberg, numerous other memorial foundations also served this goal. Among the rulers of the empire, Heinrich is by far the most frequently mentioned in memorial documents. According to Ludger Körntgen, the images of rulers are primarily to be seen as an expression of concern for the memoria and less as a means of propagating a sacred kingship. In the spring of 1017 Kunigunde fell seriously ill. The ruling couple then tried hard to maintain their memoria. The remembrance of the Ottonians, which was cultivated mainly in Gandersheim and Quedlinburg , was moved to Merseburg by Heinrich, where in 1017/18 Thietmar von Merseburg had the names of the deceased entered in a liturgical manuscript that is still preserved today . At the same time, Kunigunde founded the Kaufungen convent . In Bamberg, Magdeburg and Paderborn, Heinrich allowed himself to be included in individual cathedral chapters in order to receive a share in the intercessions there.

Nobility politics

A change of ruler in the 10th century was at the same time a “challenge to the previous hierarchy” and often a trigger for conflicts. The ruler had to balance the ranking among the most powerful nobles in such a way that conflicts did not arise. Heinrich did not take sufficient account of the “rules of the game”, the unwritten social norms in a high-ranking society. The Ottonian rule, based on personal relationships, was based on a cooperation between the nobility and the church and their involvement in the measures to secure the empire. In oral deliberations, a balance was reached and consensus was established (so-called consensual rule ). Research disagrees as to whether the conflicts that could not be resolved consensually had structural reasons or were due to Heinrich's new conception of the office of king.

Because of the numerous conflicts with the aristocratic families, Stefan Weinfurter referred to Heinrich II as the “King of Conflicts”. As a striking difference between Heinrich II. And his predecessors, Gerd Althoff pointed out that Heinrich was not as ready for rulership clementia (mildness) as the rulers of the Ottonian main line apparently were towards their enemies. This diminished the chances of mediators succeeding in conflicts. Althoff justified the ruler's willingness to compromise in later years of rule with the serious illness he and his wife had. That is why his actions focused primarily on securing his memoria. Karl Ubl attributed the numerous conflicts during his reign to his childlessness and interpreted them less as measures to strengthen central power. Because of his childlessness, Heinrich had to struggle again and again with attacks on his authority by worldly greats. Stefan Weinfurter explains the conflicts with Heinrich's conception of rule, according to which his kingdom was a "house of God" and he himself was the administrator of God. In the empire the royal power held the highest authority. This world of thought explains Heinrich's uncompromising attitude and his harsh demand for obedience.

In addition to the relationship with Bolesław Chrobry, Upper Lorraine in particular was a constant source of conflict. Even the brothers of Heinrich's wife Kunigunde rebelled against him. As members of the Luxembourg Count House, they tried in 1008 on the Trier Erzstuhl to enforce their candidate against the will of the king. Heinrich immediately began a feud against his brothers-in-law. He withdrew the duchy from his brother-in-law, Duke Heinrich of Bavaria , who had favored the Luxembourg counts as intermediaries. Count Palatine Ezzo , the husband of Otto III's sister, who had supported the Luxembourgers in this conflict, also felt the king's anger. Heinrich denied his share of the Ottonian inheritance. At the end of 1012, Heinrich made a provisional peace with the Luxembourg Count House in Mainz. Count Palatine Ezzo was granted his Ottonian inheritance. In January 1015, the Luxembourg counts submitted. They went barefoot and pleading for grace before the emperor and were received by him with grace. But they had to give up the Trier bishop's chair for good. For this they could keep the diocese of Metz and the duchy of Bavaria.

effect

Contemporary judgments

The judgments of contemporaries about Heinrich's rule are extremely different. Bishop Thietmar von Merseburg , who wrote his chronicle between 1012 and 1018, is considered a particular expert on the reign of Henry II. He judged the kings primarily according to their position in relation to his diocese. He celebrated Heinrich as the ruler who had brought back peace and justice to the empire. With the re-establishment of the diocese of Merseburg, which was repealed by Otto II. In 982, Heinrich became the savior of the Merseburg church. Nevertheless, Thietmar clearly disapproved of individual steps Heinrich took, and in particular he often criticized bishops' surveys. Thietmar only used the name of the king, derived from the anointing , as christus Domini (anointed of the Lord) in connection with an extremely harsh criticism after Heinrich had decided in a property dispute in favor of a follower and against Thietmar's family members. Thietmar hid his judgment by claiming that he was only reproducing an opinion that was widespread everywhere (omnes populi mussant) , but in this way he dared to write "that the Lord's anointed sin" (christum Domini peccare occulte clamant) .

In addition to mourning over Heinrich's death and praise for his deeds, there are also critical voices such as that of Bruns von Querfurt , a supporter of Otto III's politics. In 1008, Brun expressed sharp criticism of Heinrich's Poland policy in a letter and asked the king to immediately end the alliance with the pagan Liutizen against the Christian Duke of Poland, which was a sin. In his opinion Heinrich was not concerned about Christianity, but about honor secularis , worldly honor. Therefore he invades a Christian land with the help of pagans. Brun's urgent warnings to Heinrich also address the problematic severity of the king: "Be on your guard, O King, if you always want to do everything by force, but never with mercy."

The Quedlinburg Annals were created in the time of Henry II, when Quedlinburg lost its old dominant position as the royal capital. The annalist harshly criticized the ruler's actions. However, the loss of closeness to the king did not last throughout Henry's reign. In 1014 Heinrich transferred the management of the women's convents Gernrode and Vreden to the abbess Adelheid von Quedlinburg . In 1021 he visited Quedlinburg on the occasion of the consecration of the newly built monastery church and made a rich donation to the convent. From this year on, the annals will stop making negative comments. From 1021 the annalist even began to portray Heinrich's deeds in a panegyric way.

Henry's numerous donations and ecclesiastical measures have given rise to the image of a pious and caring ruler, especially in the monastic sources. In a poem dedicated to Abbot Gerhards von Seeon from 1012/14, Heinrich is praised as a brilliant jewel of the empire and a blossom of the entire microcosm. God entrusted him with the highest administrative dignity.

The Canonization (1146) and the later judgments

After Heinrich's death the picture of the holy emperor was put up in Bamberg. It was possible to directly tie in with the designation “the pious”, which was already used during his lifetime: In a prize song from Abbot Gerhards von Seeon he is addressed as “O pious King Heinrich” (pie rex Heinrice) . The actual transfiguration through a special “holiness” can be grasped around the middle of the 11th century. Adam von Bremen reported in 1074 about the emperor's sanctitas . In preparation for the canonization, an unknown author from Bamberg wrote a report on Heinrich's life and the miracles he performed in 1145/1146. This text was reworked into a saint's life in 1147. The Bamberg Church, in which his memory was kept alive by annual funeral masses , was finally canonized in 1146. The requirements for holiness were scrutinized before canonization. For Heinrich the assumption, derived from his childlessness, spoke that he had married Kunigunde in chastity. Several church foundations were also considered sacred acts, above all that of the Bishop's Church of Bamberg.

A year later, on July 13, 1147, Heinrich's bones were ceremoniously raised in Bamberg in honor of the altars. Pope Innocent III confirmed this ideal when he founded the canonization of Kunigunde in 1200 with her lifelong virginity and the establishment of the Bamberg diocese together with her husband and other pious works.

In 1189, the Bamberg bishop Otto I was canonized, in 1200 the Empress Kunigunde. No other place in Christendom could boast three new saints of its own in a comparable period of time. The bishopric of Bamberg recorded every ninth of the successful canonization procedures between 1100 and 1200.

Starting from the diocese of Bamberg, the worship of the holy emperor spread in several dioceses of the empire, mainly in Bavaria, but also in Alsace and the Lake Constance area. In 1348, Henry's Day, July 13th, was declared a major holiday in the diocese of Basel .

A completely different image of Henry was cultivated in Rome, as he was particularly accused of interfering with the structure of the church. Humbert von Silva Candida , one of the pioneers of church reform , called Heinrich a Simonist and church robber. Miniatures of Joachim von Fiore's work show him as one of the seven heads of the apocalyptic dragon after Herod , Nero , Constantine II and Chosrau II and before Saladin and Frederick II. However, this assessment had no effect north of the Alps. Through the efforts of the first Staufer King Konrad III. and the image of the Holy Emperor prevailed among the Bamberg clergy.

In addition to the memory of Heinrich and his wife as saints and the negative image from the point of view of Italian church reformers, a political appreciation made itself felt over the course of time: Heinrich II was regarded as the creator of the medieval imperial constitution. Late medieval chroniclers gave his assumption of government in 1002 a joint function for the order of the empire. He was considered to be the founder of the free election of kings, the creator of the Electoral College and the entire constitution (quaternion theory). So the idea of a Holy Kingdom was based on the figure of its holy emperor.

Research history

The aura of saints that surrounded Heinrich and his wife Kunigunde offered researchers an incentive to track down the “real Heinrich”. In the 19th century, attempts were made to achieve this goal by ascertaining every surviving detail about his life and compiling the results of the fact-finding in the yearbooks of German history . Since the portrayal of Wilhelm von Giesebrecht , Heinrich was regarded as the "political head". The "establishment of the German Empire" and the "exaltation of royalty as a protective power over everyone and everything" was "the great political idea that can be traced from his first to his last year in government". For Giesebrecht, Heinrich's reign remained tragic and incomplete, as it "took almost twenty years to break the defiance of the great". Only his successors succeeded in bringing the empire "to a height" "which it had never reached before and should never reach again". The relevant handbook descriptions by Karl Hampe ( The High Middle Ages. History of the West from 900 to 1250 , 1932) and Robert Holtzmann ( History of the Saxon Empire , 1941) took over the characterization of Heinrich as an ideal but tragic statesman.

For decades, however, Heinrich was not an attractive subject for biographical investigation. It is missing in the multiple published works on the great imperial history of the Middle Ages, both in Karl Hampe's rulers of the German Middle Ages from the 1920s and in Helmut Beumann's Imperial figures of the Middle Ages (1984). The Liudolfinger was honored only in the manuals and overview representations of the history of the empire, in which it necessarily belonged to the topic. Surrounded by two favorite rulers of historical science, Otto III. and Conrad II , the holy emperor did not take on any clear contours. His predecessor was stylized by Percy Ernst Schramm and the George Circle as a tragic youth on the imperial throne. In Heinrich, on the other hand, a sickly ruler who was completely focused on his clergy had followed a visionary emperor. Heinrich's successor Conrad II, who contrasted with him, was glorified by nationally minded historians as a supposedly unchurch ruler to a “full-fledged layman” and honored as a successful dynasty and power politician.

After the Second World War, in the work of Theodor Schieffer (1951) to Hartmut Hoffmann (1993), the comparison of Heinrich II with his successor developed into a popular topic in medieval research. Carlrichard Brühl referred to Heinrich as the first “German king” in 1972, Johannes Fried called him the “most German of all early medieval kings” in 1994, but such ideas, which were previously considered to be certain knowledge, have changed due to the extensive research into nation building over the past decades. Medieval studies today see the German Empire as a process that lasted from the 9th to the 12th century.

Stefan Weinfurter (1986) turned to Heinrich II's ruling practice. He spoke of the centralization of rulership and observed in Heinrich "a high degree of continuation and enhancement of the elements developed in the ducal rule at the royal level".

The newer reviews are very different. For Hartmut Hoffmann (1993) Heinrich is the embodiment of the ideal ruler in the Ottonian-Salian imperial church system , a “monk king”. Johannes Fried (1994), on the other hand, believes that Heinrich unscrupulously made use of all means of power, “from ruse to betrayal to naked violence and with a particular preference for canon law”. Modern Medieval studies largely agree that the last ruler from the Ottonian dynasty attempted to intensify royal rule.

Today Heinrich's image in historical studies is mainly determined by the biography published in 1999 and the accompanying studies by Stefan Weinfurter. According to Weinfurters assessment, Heinrich's self-image has been determined by the awareness of his descent from King Heinrich I since 1002 . From this he derived a never given up claim to participation in the rulership and, above all, to royal rights of the Bavarian duke. Without his origin, Heinrich's royal rule “cannot be interpreted”. This is indicated by personal continuities when "old friends from the ducal era" meet again in the court orchestra and chancellery, but also Heinrich's concept of his responsibility for the Church of God, which is perceived as a personal obligation. Weinfurter noted a special reference to the Old Testament Moses and understood Heinrich's kingship as a real "Moses kingship". Heinrich considered it his task "to ensure, like a new Moses, that the commandments of God become the basis and content of the life of all people of his people".

At the beginning of the new millennium, a large number of exhibitions and conferences on Heinrich II took place. At a Bamberg conference in June 1996, the continuities and discontinuities in the reign of Otto III. and Henry II discussed. Consensus was reached that “the change from Otto III. on Henry II should not be seen as a programmatic departure and a new conceptual approach ”. A change was noted in the style of rule and in relation to the imperial church. The Bavarian State Exhibition in Bamberg in 2002, recalled the election of a king Henry II. In 1002. Much attention was also the millennium anniversary of the Bamberg diocese founded in 2007. The Diocesan Museum Bamberg held from July 4 to October 12, 2014 to mark the thousandth anniversary of the imperial coronation the exhibition Crowned on Earth and in Heaven. The holy imperial couple Heinrich II and Kunigunde and published a catalog.

swell

- Adalbold von Utrecht : Vita Heinrici II. Imperatoris , ed. Georg Waitz , in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Scriptores (in folio) 4, Hannover 1841, reprint 1982, pp. 679–695 ( digitized version ).

- The documents of Heinrich II. And Arduin (Heinrici II. Et Arduini Diplomata) , edited by Harry Bresslau , Hermann Bloch , Robert Holtzmann et al. (MGH Diplomata regum et imperatorum Germaniae 3), Hanover 1900–1903 (reprint 2001) ( digitized version ).

- The Tegernsee Letter Collection, ed. Karl Strecker (MGH Epistolae selectae 3), Berlin 1925 (reprint 1964) ( digitized ).

- Johann Friedrich Böhmer : Regesta Imperii II, 4. The Regesta of the Empire under Heinrich II. , Reworked by Theodor Graff, Vienna et al. 1971 ( digitized ).

- Thietmar von Merseburg, chronicle . Retransmitted and explained by Werner Trillmich . With an addendum by Steffen Patzold . (= Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition. Vol. 9). 9th, bibliographically updated edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-24669-4 .

literature

Overview works

- Gerd Althoff : The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 3rd, revised edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-17-022443-8 .

- Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller : The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt. Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 3). 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-60003-2 .

- Helmut Beumann : The Ottonians. 5th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 2000, ISBN 3-17-016473-2 .

- Johannes Fried : The way into history. The origins of Germany up to 1024. Propylaea, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-548-26517-0 .

- Hagen Keller: The Ottonians. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-44746-5 .

- Ludger Körntgen : Ottonen and Salier. 3rd revised and bibliographically updated edition. Scientific book society. Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-23776-0 .

- Timothy Reuter (Ed.): The New Cambridge Medieval History 3. c. 900-1024. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, ISBN 0-521-36447-7 .

Representations

- Siegfried Hirsch : Yearbooks of the German Empire under Heinrich II. 3 vol., Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1862–75.

- Hartmut Hoffmann: Monk King and "rex idiota". Studies on the church policy of Heinrich II. And Konrad II. (= Monumenta Germaniae historica. Studies and texts. Vol. 8). Hahn, Hannover 1993, ISBN 3-7752-5408-0 .

- Josef Kirmeier, Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter et al. (Eds.): Heinrich II. 1002-1024. Accompanying volume for the Bavarian State Exhibition 2002 (Bamberg, July 9 to October 20, 2002). Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 978-3-8062-1712-4 ( review ).

- Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (Eds.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? (= Medieval research. Vol. 1). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1997, ISBN 3-7995-4251-5 ( digitized version ).

- Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages, historical portraits from Heinrich I. to Maximilian I. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-534-17585-9 , p. 97-118.

- Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. 3. Edition. Pustet, Regensburg 2002, ISBN 3-7917-1654-9 .

- Stefan Weinfurter: The centralization of power in the empire by Emperor Heinrich II. In: Historical yearbook . Vol. 106, 1986, pp. 241-297.

Web links

- Literature by and about Heinrich II in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Heinrich II. In the German Digital Library

- Emperor Heinrich II. - State exhibition in Bamberg, page with many pictures and brief information on Heinrich II.

- Kaiser Heinrich Library with digital copies of manuscripts going back to Heinrich II in the Bamberg State Library

- Maren Gottschalk : 02/14/1014 - Heinrich II is crowned emperor in Rome WDR ZeitZeichen from February 14, 2014 (podcast)

swell

- Arno Mentzel-Reuters , Gerhard Schmitz (arrangement): Digital edition of Thietmar's chronicle of Merseburg. MGH, Munich 2002.

Remarks

- ↑ Hubertus Seibert: A great father's hapless son? The new politics of Otto II. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): Ottonische Neuanfänge. Mainz 2001, pp. 293-320, here: p. 302.

- ↑ MGH DO III. 155 (994 Nov. 23). Compare with Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, pp. 41 and 94.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (ed.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages, historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I Munich 2003, pp. 97–118, here: p. 98.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 54.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Late Antiquity to the End of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, p. 318f.

- ^ Walter Schlesinger: Succession and election at the elevation of Heinrich II. 1002. In: Festschrift for Hermann Heimpel on the 70th birthday. Vol. 3. Göttingen 1972, pp. 1-36.

- ↑ Armin Wolf: 'Quasi hereditatem inter filios'. On the controversy about the right to vote for kings in 1002 and the genealogy of the Konradines. In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History . German Department. Vol. 112, 1995, pp. 64-157. Eduard Hlawitschka: Investigations on the change of throne in the first half of the 11th century and on the aristocratic history of southern Germany. At the same time clarifying research on "Kuno von Öhningen". Sigmaringen 1987. On the arguments against Eduard Hlawitschka Gerd Althoff: The applicants to the throne of 1002 and their relationship with the Ottonians. Notes on a New Book. In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine . Vol. 137, 1989, pp. 453-459.

- ↑ Steffen Patzold: King surveys between inheritance law and the right to vote? Succession to the throne and legal mentality around the year 1000. In: German archive for research into the Middle Ages . Vol. 58, 2002, pp. 467-507 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Eduard Hlawitschka: The legal basis and behavior in overcoming the crisis of occupation of the throne in 1002. In: Writings of the Sudeten German Academy of Sciences and Arts. Vol. 26, 2005, pp. 43-70.

- ↑ D HII, 34. Ludger Körntgen: Inprimis Herimanni ducis assensu. On the function of DHII. 34 in the conflict between Heinrich II and Hermann von Schwaben. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 34, 2000, pp. 159-185.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The centralization of power in the empire by Emperor Heinrich II. In: Historisches Jahrbuch . Vol. 106, 1986, pp. 241-297, here: p. 286.

- ↑ Thietmar V, 15-18.

- ↑ Thietmar V, 14.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The centralization of power in the empire by Emperor Heinrich II. In: Historisches Jahrbuch. Vol. 106, 1986, pp. 241-297, here: pp. 275f.

- ↑ Thietmar VI, 41.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Prayer remembrance for participants in Italian trains. A previously unnoticed Trent diptych. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien , Vol. 15 (1981), pp. 36-67, here: pp. 44ff.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, p. 232.

- ↑ Thietmar VI, 7-8.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, p. 340. Ursula Brunhofer: Arduin from Ivrea and his followers. Investigations into the last Italian royalty of the Middle Ages. Augsburg 1999, pp. 203-250.

- ↑ Johannes Fried: Otto III. and Boleslaw. The dedication image of the Aachen Gospel, the "Act of Gniezno" and the early Polish and Hungarian royalty. An image analysis and its historical consequences. Wiesbaden 1989, pp. 123-125.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, pp. 144ff.

- ^ Knut Görich: German-Polish relations in the 10th century from the point of view of Saxon sources. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 43, 2009, pp. 315-325, here: p. 322.

- ^ Knut Görich: German-Polish relations in the 10th century from the point of view of Saxon sources. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 43, 2009, pp. 315-325, here: p. 323.

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: pp. 112ff. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95–167, here: pp. 112 and 165 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Emperor Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. Rulers with similar concepts? In: Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae. Vol. 9, 2004, pp. 5–25, here: p. 24.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Emperor Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. Rulers with similar concepts? In: Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae. Vol. 9, 2004, pp. 5–25, here: pp. 18f.

- ^ Joachim Henning: New castles in the east. Places of action and history of the events of Henry II's Polish trains in archaeological and dendrochronological findings. In: Achim Hubel, Bernd Schneidmüller (Ed.): Departure into the second millennium. Ostfildern 2004, pp. 151–181, here: p. 181.

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95–167, here: p. 119 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Thietmar V, 18.

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95–167, here: p. 120 ( digitized version ); Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, p. 323.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 2nd extended edition, Stuttgart et al. 2005, p. 209. Knut Görich: A turn in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: pp. 110f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 124 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 136 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 127 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95–167, here: pp. 126 and 142 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Noble and royal families in the mirror of their memorial tradition. Studies on the commemoration of the dead of the Billunger and Ottonians. Munich 1984, p. 110f.

- ↑ Wolfram Drews: The Dortmund Totenbund Heinrichs II. And the reform of the futuwwa by the Baghdad caliph al-Nāṣir. Reflections on a Comparative History of Medieval Institutions. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 50, 2016, pp. 163–230, here: p. 166.

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95–167, here: pp. 128 and 142.

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 152 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Gerd Althoff, Christiane Witthöft: Les services symboliques entre dignité et contrainte. In: Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. Vol. 58, 2003, pp. 1293-1318. Gerd Althoff: The power of rituals. Symbolism and rule in the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2003, pp. 95f. Gerd Althoff: Symbolic communication between Piasts and Ottonians. In: Michael Borgolte (ed.): Poland and Germany 1000 years ago. Berlin 2002, pp. 293-308, here: pp. 296-299. Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 159 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 160 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, pp. 325f. Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 158.

- ↑ Sebastian Scholz: Politics - Self-Understanding - Self-Presentation. The Popes in Carolingian and Ottonian times. Stuttgart 2006, pp. 396-404.

- ↑ Klaus Herbers, Helmut Neuhaus: The Holy Roman Empire. Scenes from a thousand years of history (843–1806). 2nd Edition. Cologne 2006, p. 57.

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 160 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: pp. 137f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: p. 141.

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167, here: pp. 112-115; 124f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95–167, here: pp. 160–164 ( digital copy ); Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, p. 219.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, pp. 220-222.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 2nd expanded edition, Stuttgart et al. 2005, p. 226.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, p. 344.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 2nd expanded edition, Stuttgart et al. 2005, p. 227.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, p. 272.

- ^ Carlrichard Brühl: The beginnings of German history. Wiesbaden 1972, p. 177.

- ↑ Knut Görich: Otto III. Romanus Saxonicus et Italicus. Imperial Rome politics and Saxon historiography. Sigmaringen 1993, p. 270ff.

- ^ Rudolf Schieffer: From place to place. Tasks and results of research into outpatient domination practice. In: Caspar Ehlers (Ed.): Places of rule. Medieval royal palaces. Göttingen 2002, pp. 11-23.

- ↑ Thomas Zotz: The presence of the king. On the rule of Otto III. and Heinrichs II. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 349-386, here: pp. 384f.

- ↑ Eckhard Müller-Mertens, The structure of the empire in the mirror of the ruling practice of Otto the great. Berlin 1980; Roderich Schmidt, King's ride and homage in Ottonian-Salian times. In: Lectures and Research. Vol. 6, 2nd edition, Konstanz et al. 1981, pp. 96-233.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Empire structure and conception of rule in the Ottonian-Early Salian times. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 16, 1982, pp. 74-128, here: p. 90.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, especially pp. 21f., 30f. and 114-125.

- ^ Steffen Patzold: Heinrich II. And the German-speaking southwest of the empire. In: Sönke Lorenz, Peter Rückert (Ed.): Economy, trade and traffic in the Middle Ages. 1000 years of market and coinage law in Marbach am Neckar. Ostfildern 2012, pp. 1–18.

- ↑ Gert Melville: To Welfen and Höfe. Highlights at the end of a conference. In: Bernd Schneidmüller (Ed.): The Guelphs and their Brunswick court in the high Middle Ages. Wiesbaden 1995, pp. 541-557, here: p. 546.

- ↑ Hartmut Hoffmann: Self-dictation in the documents of Otto III. and Heinrichs II. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages. Vol. 44, 1988, pp. 390-423 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Noble and royal families in the mirror of their memorial tradition. Studies on the commemoration of the dead of the Billunger and Ottonians. Munich 1984, p. 172f.

- ↑ Michael Borgolte: The foundation documents of Heinrich II. A study on the scope of action of the last Liudolfinger. In: Karl Rudolf Schnith, Roland Pauler (Hrsg.): Festschrift for Eduard Hlawitschka for his 65th birthday. Kallmünz 1993, pp. 231-250, here: p. 239.

- ↑ Herbert Zielinski : The imperial episcopate in the late Tonic and Salian times (1002–1125). Part I, Stuttgart et al. 1984, p. 104. Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, p. 125.

- ↑ Stephan Freund: Communication in the rule of Heinrich II. In: Journal for Bavarian State History , Vol. 66 (2003), pp. 1–32, here: p. 24 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Otto III. and Henry II in comparison. A résumé. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): Otto III. and Heinrich II. A turning point. Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 387-413, here: pp. 406-409.