Russian pop music

Russian pop music and pop music from Russia are general terms for the popular music styles that are heard in Russia or the Russian-speaking area . By and large, the mechanisms of Russian pop music differ little from those of other industrialized countries . In addition to Anglo-Saxon-dominated international pop music productions that are also present in the new Russia, there are special country-specific traditions to bear - as the country's own folklore by the Soviet era dominated popular music ( Estrada ), the Russian Chanson and its own form of country-oriented pop music who have favourited Popsa .

term

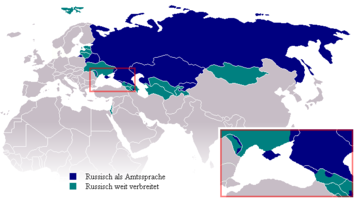

Linguistic and geographical ambiguities make it difficult to define the term precisely. It starts with the language. On the one hand, pop music sung in Russian is heard all over Russia. But there are also pop markets for ethnic minorities - on the one hand in Russia itself (for example in Siberia or the border areas to the former Soviet republics in Central Asia ), on the other hand in the former Soviet countries such as Belarus and Ukraine . In addition to this geographical differentiation, Russian pop music is also a factor worldwide. The different Russian exile communities - for example in Western Europe , the USA or Canada - are a major factor in this .

Another factor is that international pop productions are now being heard a lot in Russia too. While the older generation still prefers the classic Estrada style, international pop stars such as Madonna , Lady Gaga and others are very popular with the younger generation . Also techno -music has a strong presence in Russia - where the term Popsa has established for this form of disco dance music. With the fall of the Iron Curtain , western niche and underground styles have also spread. You can find them mainly in an urban environment - accordingly specialized clubs in St. Petersburg , Moscow or Kiev . After all, Russian rock music went through its own development . While it still functioned as a decisive catalyst for system-critical opposition in the Soviet Union, it increasingly fell into crisis in the 1990s and 2000s - on the one hand in terms of content, on the other hand due to the dynamism of the cultural sector, which is now subject to market laws .

Similar to other large countries, Russian pop music is also a conglomerate of different individual styles. The main directions are:

- Estrada. Classic Russian light music as it was known in the times of the Soviet Union. Internationally one of the most famous exponents is the Red Army Choir ; also some well-known hits like Moscow Nights (Russian original title: Podmoskownyje Wetschera ) are typical Estrada productions. This direction, which can roughly be described as the Russian version of easy listening , was strongly promoted by the state-owned music and record production company Melodija .

- Popular Russian music, folklore. The folklore scene is differentiated according to regionally different focuses. In part, it still serves to maintain customs. In addition, there are more or less commercialized productions that dominate the popular music market. A third direction is the adaptation on the part of advanced music projects that pick up on, maintain and develop folklore tradition.

- Popsa. Russian disco techno, i.e. electronic dance music, is widespread among younger people. On the one hand, Popsa is a differentiating factor, for example from critical young people belonging to certain subcultures . On the other hand, disco dance music “made in Russia” is a defining market factor and - for example: the duo tATu - is also noticed abroad.

- Chanson, Bard and Lied. The Russian variant of the Anglo-Saxon singer-songwriter culture is based on several lines of tradition. In addition to the upscale, demanding hit (example: the singer Michail Schufutinski ), these are above all the bard song (the Soviet form of the folk and protest song of the 1960s ) and the so-called blatnye pesni - the criminal, petty people and camp songs whose tradition goes back to the beginning of the 20th century .

- Jazz . The Russian variant of jazz music looks back on an eventful history. In the 1920s and 1930s , a Soviet jazz scene of its own developed. Increasingly sidelined at the end of the 1930s, it only hada brief revivalin the first half of the 1940s - during the Great Patriotic War . Because of the music itself, the current Russian jazz scene has a strong international focus. As in other countries, jazz in Russia is more of a niche than a mainstream music style.

- Skirt. Russian rock music had its heyday in the perestroika and glasnost periods at the end of the 1980s. After the opening of the Iron Curtain and the liberalization of the markets, rock music of the perestroika era also fell into crisis. In the meantime, a general reorientation has set in in the scene, along with a stylistic differentiation. However, rock is still a factor with Russian lyrics. Well-known bands: Aquarium , Kino and DDT .

- Underground . In heavily urbanized centers , underground niche cultures have emerged since the 1990s, comparable to those in other industrialized countries. The centers of these music scenes are small clubs , mainly in St. Petersburg and Moscow. Common feature: the demarcation from the predominant music mainstream. The underground is stylistically very heterogeneous. In addition to strong musical preferences for Ska , Klezmer , the Blat Chanson, Gypsy music and Eastern European folklore, there is also a scene that makes ambitious electronic music . In Germany this form of Russian club music was mainly due to the Russian disco events Select and compilations of the in Berlin living author and DJs Wladimir Kaminer known.

In addition to the Russian language, other international lingua franca are increasingly finding their way into the musical repertoire. In order to survive on the international pop market, groups and performers such as tATu or the singer Valerija publish English-language versions of their productions. Conversely, there are hundreds of cover recordings of well-known Russian pieces both in Russia and internationally - especially of classics such as Katjuscha or Dorogoi dlinnoju , whose melodies (sometimes with other titles such as Those Were the Days ) are spread across the globe are. A special feature besides the language is the accompanying Cyrillic script - a factor that clearly inhibits the spread beyond this writing space. With well over a hundred million people in the distribution area, the market for Russian pop music is still large. In the course of the constant and growing interest in local pop cultures (keyword: ethno-pop ), since the beginning of the 21st century there has been an increased interest in pop music from Russia in Western Europe , the USA and other regions of the northern hemisphere .

history

Precursors in the 19th century

Russian popular music was heavily influenced by Russian folklore . At the time of the tsarist empire , this encompassed not only Russian folk music in the narrower sense, but also Ukrainian, West and Belarusian as well as the musical traditions of Jewish minorities , Sinti and Roma and neighboring Central , Eastern and Southeastern European countries. Exotism , a longing for the Orient and a preference for gypsy music were very popular in both popular and serious music of the 19th century . The operas Carmen and Aida by Georges Bizet and Giuseppe Verdi as well as some works by the composer Claude Debussy are considered outstanding examples . Russian composers were also interested in folk music . Professional choirs and music orchestras were a means of staging this music . The first known folklore choir was formed at the beginning of the 19th century: the Pjatnizki Choir founded by Mitrofan Pjatnizki . Another well-known ensemble was the folklore professional orchestra founded by Vasily Andreev at the end of the 19th century . A characteristic of this orchestra was the fact that professional musicians arranged the folklore material and thus brought it into a new form. The Paris World's Fair in 1889 was an excellent opportunity to demonstrate this form of exoticism to a wide audience .

Even classical musicians inspired more and more for the music of the common people. Modest Mussorgsky , César Cui , Georgi Rimski-Korsakow , Alexander Borodin and Mili Balakirew founded the group of five . Their goal was to renew Russian art music by incorporating folk elements. This also included field studies. Mili Balakirew traveled along the Volga in 1860 and collected numerous folk songs . In terms of time, this interest coincided on the one hand with the abolition of serfdom, on the other hand with the rise of the critical intelligentsia - especially the politically left-wing Narodniki , from whose environment the Social Revolutionary Party, which was very important during the October Revolution, developed. Michail Glinka , father of Russian art music , formulated his preference for folk music with the words: “Music is created by the people. We composers only bring it into one form. ” The singer and musician Sergei Starostin also retrospectively characterized the importance of the folkloric tradition as immense: “ The village was the soul of Russia. The land has also fed us spiritually. This is where the various Russian musical styles originated. "

The folk music tradition was increasingly placed at the service of the state; The aim was to create a "national music culture". Due to technical inventions like the phonograph , the interest in rural folklore could be further systematized; This is how the first field recordings were made at the beginning of the 20th century. At the same time, the traditional entertainment class had also developed. St. Petersburg, at that time the capital of the tsarist empire, attracted numerous famous singers in the 19th century. A well-known venue was the St. Petersburg Mariinsky Theater , where the Verdi opera Power of Fate was premiered in 1862 . The place was renamed the Kirov Theater, which is also common today, in 1937. Another well-known venue was the Moscow Bolshoi Theater - a theater that was founded in 1776.

1917–1991: Popular music in the Soviet Union

The October Revolution of 1917 and the civil war that followed did little to change the basic constellation. As in other European countries, new musical styles that emerged after the end of the First World War became increasingly popular in the early Soviet Union - especially in metropolitan centers. The traditional waltz was joined by new fashion styles such as tango , foxtrot , Apache dance and jazz, which came to Russia from the USA via Western Europe. The contemporary operetta was also popular . Well-known interpreters from this period are Pyotr Leschtschenko and Alexander Wertinsky . The latter emigrated in 1920, played mainly in front of an emigrant audience in the following years and returned to the Soviet Union in 1943. Up until the 1930s, a variety of different styles coexisted - including, in addition to popular tango and popular folklore melodies, a number of more or less well-known jazz ensembles. Well-known jazz formations based on the swing style of the time were the orchestras of Jakow Skomorowski , Alexander Zfasman and Leonid Utjossow . An urban folklore tradition was offered by the metropolitan Blatnye pesni: the Criminal Songs and camp songs now known as Russian Chanson. They originally came from the port cities on the Black Sea (especially the strongly multicultural port city of Odessa ) and spread unstoppably over the entire republic during the NEP era. Well-known chansons such as Murka and Bublitschki were not only very popular in the Soviet Union. Through numerous interpretations, some of them found their way into the repertoire of international pop music.

In the mid-1930s, the era of relative cultural tolerance came to an end. Leonid Utjossow and others were able to assert themselves as recognized entertainers, but had to make artistic concessions. Despite the pressure exerted by the state and the open repression, especially during the years of the Stalinist show trials , popular music was not completely uniform even at the height of Stalinism . In practice, ideologically motivated cultural policy was often characterized by contradictions. The Criminal Songs, for example, fell under verdict on the one hand. On the other hand, even high functionaries, including Stalin himself, proved to be friends of this musical genre. Contemporary witnesses reported, for example, that the well-known chanson Gop-so-smykom was one of Stalin's favorite songs and was expressed as a music request in the informal area. During the time of the Great Patriotic War between 1941 and 1945, the regime was forced to make cultural concessions. Entertainment jazz made a brief comeback during World War II . Examples of this: some popular propaganda titles such as Cossacks in Berlin or Lied der Frontkraftfahrer . Another world-famous Russian song also comes from this period - Katyusha . Created in 1938 by the lyricist Michail Issakowski and the composer Matwei Blanter , Katyusha has been translated into all major world languages. Under the title Fischia il vento , it became one of the standard songs of the Italian Resistance .

Russian light music was more and more shaped by the so-called Estrada - a state-controlled form of easy listening that combined forms of light and serious music and pursued the goal of establishing a system-compliant, but at the same time demanding form of light music. On the one hand, this form of light music had a system-preserving function. Since - contrary to the opinion of some cultural ideologists - it turned out to be impossible to conceive a “Soviet” style of music on the drawing board, a certain variety of styles was ultimately inevitable, and within a certain framework even desirable. The spectrum ranged from operetta-like productions to patriotic titles, marching music and hits to more sophisticated entertainment and echoes of jazz. Popular hits and folklore were also an integral part of the Soviet musical spectrum - due to the heterogeneous musical traditions in the individual republics, this is a very diverse sector.

The craft profession guaranteed within this system the network of state music schools and music colleges as well as the state-regulated professional practice as a musician. On the one hand, this system was restrictive. On the other hand, it guaranteed a minimum quality standard and an adequate supply of (musical) culture to the population. Like other countries, the Soviet Union had its stars and audience favorites. Among the “red stars” of the 1930s and 1940s were the singers Isabella Jurjewa , Klawdija Schulschenko and Lidija Ruslanowa , the singers Pavel Michailow (soloist of Alexander Zfasman's jazz band) and Wadim Kosin, and the immensely popular bandleader Leonid Utjossow. In the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s the Estrada system - despite occasional scandals such as a concert series in the 1960s with playback and interpreter doubles - ensured a steady new generation. Well-known artists in the last decades of the Soviet Union included Anna German , Sofija Rotaru , the Baku- born singer Müslüm Maqomayev and Alla Pugatschowa . Alla Pugacheva not only included modern trends in her music, but did not shy away from confronting party leaders when it came to content-related issues.

A substantial change for the music publishing industry meant the establishment of a new monopoly company in 1964 - the Moscow record label Melodija. The practical consequence has been an even tighter control of music releases. The consequence of the state monopoly efforts was that independent musicians continued to be pushed into the semi-official underground and had to make their recordings in an informal, semi-legal way. This was especially true for rather unpopular art forms such as the Russian chanson and - to an even greater extent - anti-government protest songs, the bard songs. Due to the problems of getting suitable material for pressing records, artists made a virtue out of necessity and, for example, misused the layer supports of X-ray images for the production of sound carriers. Apart from the official events, some artists established themselves in the 1970s who are still regarded as formative for Russian chanson, especially the special genre of criminal songs or, in Russian, blatnye pesni. The singer and actor Vladimir Vysotsky , whose songs were mostly composed in the 1960s and 1970s, is still widely regarded by many as the most important Russian chansonnier of the 20th century. Arkady Severny from Leningrad , whose work coincides with that of Vysotsky and who died at a similarly young age at a little over 40 , was not quite as well-known, but just as important for the further development of this section of songs . Other chanson performers: Alexander Rosenbaum from St. Petersburg and Kosta Beljarew .

Apart from this scene of “Soviet dandies”, another non-conforming form of the song developed in the 1960s and 1970s. Unlike the traditional crook chansons, the so-called bard (literally translated: bard ) was primarily aimed at intellectuals . Stylistically, the Bard performers took up elements of Anglo-American folk music and songwriter / songwriter tradition. Closely connected with the literary-artistic opposition of the Brezhnev era, the Bard songwriters and the samizdat scene closely associated with them were even more restricted to the informal area. The venues were private apartments or public places outdoors. Bulat Okudschawa is considered the most important, outstanding bard singer . Okudschawa got involved in the fight against political repression, signed a petition for the release of Alexander Solzhenitsyn , translated texts by Wolf Biermann and is now considered the " Georges Brassens of the Soviet Union". The couple Tajana and Sergei Nikitin also became known as bard performers .

Western pop and youth culture also left its mark on the Soviet Union. An attempt to steer the new impulses in system-conforming paths was a new subgenre with the official abbreviation WIA (Russian: ВИА, abbreviated for vocal-instrumental ensemble) that was launched in the 1960s . The WIA-Schiene enables a stronger consideration of western styles, not least also in radio airplay . Well versed in a younger audience, WIA groups such as Iweria , Pesnjary , Pojuschtschije gitary , Zwety , Wesjolyje Rebjata and Semljane supplemented the conventional Estrada program with modern, contemporary elements. The building of a bridge to the international market was also sought after during the thaw period. An example: Venera, a cover version of the Shocking Blue hit Venus interpreted by the Bulgarian singer Lili Ivanova . In addition, the WIA tried to build bridges to the folkloric music of the individual republics. Popular groups here: Yalla from Uzbekistan , Chervona Ruta from Ukraine and the Belarusian formations Sjabry and Werasy .

In contrast to the WIA, which offered the opportunity to consume moderate western tones, harder rock music variants hardly had a chance. It was not until 1974 that Melodija published sound foils with Beatles pieces. Long hair and hippie clothes were considered undesirable until the 1980s; those who did not adapt had to accept career obstacles or other repression. Basically, this only changed with Gorbachev's accession to power and the perestroika he initiated. Bands from the very beginning were Nautilus Pompilius , who initially played cover versions of Led Zeppelin and the Eagles , and Aquarium, a band that was strongly oriented towards Pink Floyd . Cult bands of the perestroika era avancierten by the folk-rock coming DDT and cinema - a group whose music strongly influenced by Western European New Wave was affected. For many of their fans, DDT and cinema represented the conscience of perestroika with their socially critical texts. Other bands from this era: Alisa ( Hard Rock ), Bravo (nostalgic Rock'n'Roll ), Awia (New Wave), Awtograf ( Art Rock ), Agata Kristi ( Gothic Rock ) and Kruis ( Heavy Metal ).

After 1991: Pop music in Russia after the Soviet Union

The fall of the Iron Curtain, the breakup of the former Soviet Union and the establishment of a market economy from 1991 onwards also marked a clear turning point for Russian pop music. The first thing that became noticeable was the upheaval in the market. The state-owned company Melodija was only just able to avoid bankruptcy and in 1991 sought cooperation with the German major label BMG . One consequence of the changed situation was that the Russian market was flooded with black-copied , low-quality copies of western pop products. It was not until 1995 that music from the west was legally protected. Another reaction to the now internationalized pop music market was the emergence of test tube bands that flooded the market with their productions.

The Russian market itself was also increasingly differentiating itself. From a commercial point of view, musicians were in a bad position - not least because of the fact that Western pop music was now freely available. To make matters worse, the new production and sales channels were misused for money laundering purposes. As a result, the production and marketing of music clips in particular proved to be commercially viable (and correspondingly important for performers and groups) . The Russian branch of the US TV network MTV played an important role in this process . In 2002 Russia produced 50 to 80 music clips a year. On the one hand , money generated by crime also flows into the clip productions . On the other hand, they are currently the most promising method of making money with music. Western music majors have so far been little active in Russia. Conversely, Russian pop stars such as the singer Valerija or the duo tATu increasingly tend to aggressively target the Western market with their productions.

There have also been significant changes in the field of music genres since 1990/91. Perestroika rock of the 1980s, for example, was increasingly falling behind. In addition or as an alternative, a club scene was formed in the large urban centers, which is characterized by small, innovative bands and their fans. An independent factor is now the so-called Popsa - consumable pop with powerful beats as well as uncomplicated dance techno, which is used in the big discos and is especially popular with young people. Russian hip hop also attracted attention in the new millennium, albeit not as much as in western countries . Well-known hip-hop acts are the rapper Delfin and the group Otpetije Moschenniki . The traditional Estrada style is still very popular with the older generation; also commercialized folk productions. The Blat songs and Criminal Songs have experienced a renaissance in recent years. In terms of numbers, the Russian chanson is not as important as dance techno and conventional hits, but it is a stable factor and is especially noticed in the national and international feuilleton . One factor that still catches the eye is the ongoing music piracy . The legal downloads business is still insignificant. Overall, music sales fell by 21% in the first half of 2008. Estrada productions from the 20th century are still strongly represented on download portals on the Internet . Russian pop music is also distributed through Russian communities around the world.

The cultural upheavals in the new Russia and the associated shifts in musical habits were also closely observed by social and cultural scientists. There is broad agreement that the cultural upheavals are an expression of the overall social situation. Differences in music consumption can be identified on two levels - between old and young and within the youth themselves. While the majority of the older generation still see the stars of the Estrada as being very popular, the majority of young people prefer uncomplicated leisure time Dance techno or retort pop. Apart from this, the usual niche and subcultures have emerged in which the lifestyle is expressed with rock, metal, hip hop or underground club music. The Russian chanson traditions, sophisticated lounge jazz, western pop or avant-garde productions “made in Russia” also have their following, mainly in the urban centers. Overall, music serves as a means of demarcation within the different youth cultures. While critical, non-conformist young people distance themselves from the ever-present popsa, it is an important, identity-forming frame of reference for normal, apolitical young people. Jelena Omeltschenko, author of the book series “ kultura ” published by an intercultural Russia research project at the University of Bremen, characterized the conflicts between “normal people” and “alternatives” as part of youthful self-reassurance - whereby the Russian state specifically tries to instrumentalise the cultural reservations of the “normal people” for itself . In an essay in 2005, the author Jens Siegert named four important, distinguishable youth milieus : a nationalist-right-wing extremist, the left-wing extremist, the liberal-bourgeois and a career-oriented state-oriented one, which is strongly based on Vladimir Putin .

Genres

Estrada and Popsa

In practice, old and new Russian hits are difficult to distinguish from one another. The spectrum ranges from traditional crooners like Iossif Kobson to dance techno DJs such as DJ Smash - although the spectrum is fluid and the details of what is still “Estrada” or what is already “Popsa” are not always clear. The Estrada style from the Soviet Union still has numerous followers. He also has a strong presence in the media - especially TV. Estrada-oriented interpreters such as Nikolai Baskow , Lev Leschtschenko and others continue to perform regularly. The Estrada icon Alla Pugatschowa in particular enjoys cult status. In 2001 her record sales totaled 200 million. More recent interpreters of this direction are Irina Allegrowa , Valeri Meladze , Andrei Gubin , Tatjana Bulanowa , Larissa Dolina , Valeri Leontjew , Leonid Agutin and the interpreter Jelena Wajenga, who has been Pugacheva's successor for several years . Mixed forms between popular hits and chansons are sometimes also successful. Example: the entertainer and chanson singer Michail Schufutinski.

Techno music and Russian dance techno, the so-called “Popsa”, is ubiquitous in discos, on the Internet, on the radio and at events. The duo tATu and the singer Valerija in particular were able to gain international success. Typical for Popsa productions is the typical synthesis of internationally common disco music elements (dominant rhythm , samples , vocals ) and elements from Russian music culture. Remakes of well-known hits, which are re-recorded and given modern sound attributes, are just as common in Russia as in other countries. Finally, the numerous solo artists and boy or girl groups that come together for eliminations for international events such as the Eurovision Song Contest must be performed . With Dima Bilan , Russia managed to take first place in 2008. Other important events are the qualifications for the song contest and the annual MTV Russia Music Awards . In the broadest sense, the following artists, boy groups , girl groups and formations can be assigned to Popsa: tATu, Valerija, Alsou , The ART , Global Planet , MakSim , VIA Gra , Fabrika and Serebro .

Russian Popsa is not only present in Russia itself. Russian pop music is also in great demand in Russian communities abroad, for example in Germany. The preference is by no means limited to discos that are exclusively or mostly frequented by Russians. A reader reporter for the Oldenburgische Volkszeitung expressed the attitude towards life associated with it with the following words: “'Popsa' is more than just a genre of music, 'Popsa' is a direction of life. Women walk around in high-heeled shoes, in short skirts and with oversized lips and in general men and women walk around rather shrill for our taste. But by and large you can say that 'Popsa' is a positive addition to our music in Germany. "

Traditional folklore

Traditional folklore has only superficially fallen behind in recent years. As in other countries, there is also a stable market for traditional music and popular hits in Russia. The transitions to other main genres are also fluid here. In addition, regional differences and variants come into play in traditional folklore. While singing performed together without a solo part is typical for folk choirs in the northern regions , variants from the southern regions prefer the contrast between solo and choir voices. Regions with a strong folk music tradition are: Arkhangelsk in the north , the central Volga region and Siberia , in the south southern Russia and the Ukraine. In Ukraine, which is still closely linked to Russian culture, the typical folklore of the country is also divided into two parts. In the eastern parts of the country there are similar choral traditions as in southern Russia. In the west, on the other hand, there are many similarities with Carpathian music , as it is also known in Poland and Romania .

The origin of ecclesiastical chorales is an element of tradition that has clearly shaped the folkloric music of Russia to this day. The professionalization approaches from the 19th century - i.e. the combination of amateur and professional musicians - were continued in the time of the Soviet Union. For the 1970s, for example, the Dimitri Pokrowski Ensemble can be performed with its professionally recorded peasant songs, for the 1980s and 1990s Pesen Zemli, the groups Narodny Prasdnik and Kasatschi Krug . Other performers and ensembles of this traditionally oriented style of playing , also known as “ Revival ”: the Moscow Patriarchal Choir with singer Ariadna Rybakova, the Russian Druzhina Ensemble and the group Sirin .

Commercialized folk music hits are more popular and widespread than traditional ensembles. Well-known performers and formations are Lyudmila Sykina , Shanna Bitschewskaja (who also represents the country genre ), the Russkaja Pesnja Ensemble , Golden Ring , Anna German, Evgenija Karagod , Gennady Slavishchi and Evgenija Smoljaninowa . Since the 1990s, building bridges to the pop market has become more common, as have those to techno and electronic music. One example is the Terem Quartet , which first appeared on Russian TV on the occasion of a talent show . Other interpreters: Inna Schelannaja (Zhelannaya), Moscow Art Trio ( trance- oriented pop music with folklore elements) and the Volnitza Ensemble . Finally, the numerous ethnic music variants are to be performed, especially in the eastern, Asian regions of the country. Some are only slowly becoming accessible in the wake of the ethnic wave; In some parts of the country, especially in the Caucasus and the southern and Far Eastern Asian regions , there are Caucasian, Turkmen , Mongolian , Tuvinian and Chinese folklore traditions. An example of modern ethno-pop from the formerly Soviet Central Asian countries is the Uzbek singer Yulduz Usmonova , who - like the Israeli Ofra Haza - combines elements of pop music with the musical traditions of her homeland. Tuvinian musicians with their overtone singing are also well recognized in western countries : more traditionally oriented like Huun-Huur-Tu , rock music-oriented like Yat-Kha or avant-garde like Sainkho Namtchylak .

Rock and underground

Rapid changes have taken place in the Russian rock music scene in the two decades around the turn of the millennium. One eye-catching one is the steadily declining importance of the previously highly regarded perestroika rock. Bands like DDT, Kino and others played in sold-out halls in the 1990s. In addition, the idol-like position of some musicians - for example the DDT frontman Yuri Shevchuk or the charismatic cinema singer Viktor Zoi , who died in an accident in 1990 and subsequently became a kind of icon of perestroika rock. As early as the 1990s, the Russian rock music scene was becoming more and more differentiated. The political radicalization of some bands that became partisans of the nationalists or communists - such as the metal band Korrosija Metalla , the punk band Graschdanskaja Oborona or the folk rock group Kalinow Most - contributed to this . Some also ran for political offices - such as Sergei Troitsky, the singer of Korrosija Metalla, who - albeit unsuccessfully - applied for the office of Moscow mayor.

One element that contributed significantly to the differentiation of rock and underground music was the changing infrastructure. In Moscow, St. Petersburg and other large cities, a club scene developed more and more - small venues whose infrastructure was primarily supported by the commitment of the fans. The attempt to adopt more western styles than before did not pay off. A striking feature of the new underground was the fact that the meaning of song lyrics took a back seat . Instead, the fun character, the party factor or the artistic type of presentation came to the fore . Characteristic for the new independent rock scene is the playful, free recourse to all possible stylistic elements. Ska and punk are very common styles. In addition, local musical traditions serve as a musical orientation point - for example klezmer, gypsy music, Eastern European and Russian folklore and Russian chanson. Typical representatives of this direction are the bands Leningrad , Gogol Bordello , Billy's Band , The Red Elvises and the Moldovan skapunk band Zdob și Zdub , some of which sings in their native language and some in Russian. The trend that is more versed in electronic music is represented by music projects such as Messer für Frau Müller (St. Petersburg; Electronic and Easy Listening). Last but not least, bands and performers who are versed in jazz music are also making an appearance - such as Shanna Agusarowa (ex Brawo ) or the singer Iva Nova, who is more into the wave area . Other bands - such as the Notschnyje Snaipery , which was founded in St. Petersburg in 1993 and switched from Akustikfolk to rock - have managed to consolidate themselves over a longer period of time and to consolidate their reputation outside of the country with regular releases and performances.

The Russian underground has a strong bastion in the Russian communities scattered all over the world. In addition to the band's typical mix of styles, there is a special approach to language. Many bands have a (at least) bilingual repertoire: in addition to pieces sung in Russian, there are also pieces in English or (rarely) another national language. This mixture is strongly represented by the band The Ukrainians , which is mostly perceived as a British folk punk band. Another band coming out of the migration are Golem! (USA), the formations VulgarGrad ( Melbourne , Australia ) and La Minor , which specialize in Criminal Songs and Odessa Beats, and the two Berlin formations Rotfront and Apparatschik . In Germany, the new Russian underground music was popularized primarily by the author and DJ Wladimir Kaminer and his partner, the Red Front singer Yurly Gurzhy . Russendisko is not only the label of a sampler series published by the Munich label Trikont , but also takes place as a disco event at different locations.

The new underground in the 2010s was also rap, which was harassed by bans on performances, for example because of the glorification of drugs, to such an extent that President Putin spoke out in December 2018 about the possible counterproductivity of the official interventions, although according to SRF he was a new public enemy in the scene made out. Drugs are the way to decay the nation.

Russian chanson

Russian chanson plays a special role in current Russian pop music - more precisely: the blatnies and criminal songs from the Black Sea coast. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, this popular form of song experienced a renaissance. On the one hand, some artists from the Brezhnev era benefited from this revival - in particular the two 1970s icons Vladimir Vysotsky and Arkady Severny. Meanwhile, some film productions that deal with the marginalized and gang culture of these chansons in the broader sense have achieved cult status - for example the Soviet five-part TV series Mesto wstretschi ismenitj nelsja from 1979 (translated as: The meeting point cannot be changed; German title on the occasion a TV broadcast on GDR television: The Black Cat ) . In addition to those who were already active in the SU times, a number of newer chanson singers have established themselves in the last few decades, who continue the tradition of criminal songs in a contemporary way. Examples: the popular entertainer Michail Schufutinski, the more popular singer Michail Gulko and the chansonniers Grigori Leps and Griz Drapak .

The Criminal Songs have received increased interest from the international media in recent years. In Russia itself there are now several radio stations that have specialized in this genre. In Russia itself the popularity of this direction has increased; on the other hand, it does not meet with unanimous approval. The gangster chansons are often a thorn in the side of official rulers, functionaries and politicians. Sometimes there is reprisals - for example in Russia's neighboring country Ukraine, where the sound of taxis with Blat songs has been officially prohibited. In Russia itself, too, the popular genre keeps coming up for discussion. Andrei Saweljew, Duma member of the left-wing nationalist Rodina party , for example, expressed his annoyance in a statement about the ubiquity of the crook chansons in the radio programs and complained with the words: “If we go down to the parliamentary canteen for lunch, we'll be there ourselves with the song received via the robber princess Murka. "

The Bard song was also able to save itself into the new era. In Russia itself, there is no longer as much demand for its critical, oppositional texts as it was during the Soviet Union. It still plays an important role as a communication link between Russian communities abroad - especially in Germany, Israel and the USA. The bard song is also cultivated at some festivals, such as the Gruschin Festival near Samara and a regular event on the Sea of Galilee in Israel.

East – West Transfer: Songs and Stars

Despite the Iron Curtain, music “made in Russia” was always present in the West. Even in the days of the Soviet Union there were productions, individual songs and artists who promoted the popularization of Russian songs. Early examples of this East-West Music Transfer already existed in the 1920s and 1930s - such as provided with a French text recording of the hit song Bublitschki by the French chanson ICON Damia (1930). In Germany in the 1960s and 1970s, Ivan Rebroff in particular caused a sensation with pleasing performances of Russian traditionals. The German-Russian pop singer Alexandra also recorded Russian songs in the 1960s . Traditional Cossack -Liedgut offered the Don Cossacks is - where it was in the choir in fact a collective term for different exile choral ensembles. At the international level, the performances of the Alexandrov Choir of the Red Army caused a sensation. Despite a few bridges to the pop sector (including with the Finnish rock band Leningrad Cowboys ), the ensemble's repertoire concentrated on traditional songs as well as official songs - including the Soviet national anthem, civil war songs such as Partizanok and Soldaty as well as a number of popular evergreens (Katyusha, Kalinka ). Many of these traditionals experienced a special reception in the Eastern Bloc countries, for example the GDR.

Some classic songs have also become internationally known. The World War II hit Katjuscha from 1938, for example, spread rapidly during wartime. Katyusha has been recorded in hundreds of versions worldwide - among others by the American jazz musician and entertainer Nat King Cole and the FDJ folksing group Oktoberklub . The piece can also be found in the repertoire of current punk bands; there are also Hebrew and Chinese recordings. The two pieces Dorogoi dlinnoju and Podmoskownyje wetschera (Moscow Nights) also started an international hit career. The former was created in the 1920s and went around the world in different versions in 1969, following a recording by Mary Hopkin under the English title Those Were the Days . Podmoskownyje wetschera, a typical Estrada production from 1955, was also recorded in a wide variety of variations and language variants. Other (more or less) well-known Russian classics that can be found in different versions around the world: the traditionals Kalinka, Korobeiniki and Poljuschko Pole as well as the gypsy song Otschi Tschornyje (Black Eyes) .

In addition, there were numerous less spectacular forms of exchange - such as tours and guest appearances by more or less well-known Russian stars in the West. The famous Estrada singer Anna German, for example, had an international repertoire, including German hits, and made guest appearances at international festivals - for example the one in Sanremo, Italy . The same applies to the Soviet pop icon Alla Pugatschowa, whose song Harlekino became internationally known and appeared in a German version, among other things. Another German-Russian co-production was a duet with the German rock singer Udo Lindenberg in Moscow in 1985 (What are wars for). The Eurovision Song Contest became an important presentation platform for Russian pop in the new millennium . In the years 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007 and 2008 Russia - with the interpreters Alsou, tATu, Dima Bilan and Serebro - was able to book one of the top three places for itself.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Russia: Popsa and Russian Chanson , Irving Wolther, eurovision.de, March 28, 2008.

- ↑ a b Modern Russian Music ( Memento of the original from July 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , guidetorussia.org, accessed August 5, 2011

- ^ Exotisms in the 19th century , in: Weltmusik ; Gisela Probst-Effah, Institute for Musical Folklore, University of Cologne, summer semester 2008, accessed on August 5, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e f Simone Broughton, Kim Burton, Mark Ellington, David Muddyman, Richard Trillo (eds.): Weltmusik. World Music Rough Guide . JB Metzler, 2000, ISBN 3-476-01532-7 . (Chapter: Tatiana Didenko and Simon Broughton: Music from the People. The New Russia) .

- ↑ a b c d Russian folk music and its meaning ( Memento of the original from November 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Hubl Greiner / WDR , music history. Contributions to music history and musicology, 2003.

- ↑ a b c S. Frederic Starr: Red and Hot. Jazz in Russia 1917–1990. Hannibal, 1990, ISBN 3-85445-062-1 .

- ↑ a b c Uli Hufen: The regime and the dandies. Russian crooks from Lenin to Putin. Rogner & Bernhard, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8077-1057-0 .

- ↑ Murka - History of a Song from the Soviet Underground ( Memento of the original from May 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Wolf Oschlies, shoa.de, accessed on August 5, 2011.

- ↑ Back to the future: The renaissance of Russian crooks' songs ( Memento of the original from January 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Uli Hufen, kultura, May 5/2006: Popular Music in Russia, May 2006 (PDF; 508 kB)

- ^ A b Dance faster, comrade and don't forget to cry , Uli Hufen, Deutschlandfunk , March 12, 2005.

- ↑ a b Russian musical cultures in transition ( Memento of the original from January 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Mischa Gabowitsch, kultura, May 5/2006: Popular Music in Russia, May 2006 (PDF; 508 kB)

- ^ Fraud in the stadium , Der Spiegel , June 23, 1965 (archive).

- ↑ a b c The Russian Authors' Song ( Memento of the original from January 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Anna Zaytseva, kultura, May 5/2006: Popular Music in Russia, May 2006 (PDF; 508 kB)

- ^ Lennon instead of Lenin , Der Tagesspiegel , February 1, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e f g The history of Russian rock ( Memento of the original from December 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Michail W. Sigalow, Neue Musikzeitung , online at www.cccp-pok.com, accessed on August 5, 2011.

- ↑ a b Russian musicians are looking for fans abroad , press release news agency, February 17, 2009.

- ↑ China and Russia, the largest pirate nations in the world , press release austria, April 28, 2008.

- ↑ Russian youth scenes around the turn of the millennium or "Prolos" against "Alternative" , Jelena Omeltschenko, kultura, November 2/2005, Urban youth cultures and changing values in Russia, November 2005 (PDF; 720 kB)

- ^ Political youth organizations and youth movements in Russia , Jens Siegert, Heinrich Böll Foundation, December 2, 2005.

- ↑ Russian Pop Music Today: The Struggle for Independence ( Memento of the original from January 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , David MacFadyen, kultura, May 5/2006: Popular Music in Russia, May 2006 (PDF; 508 kB)

- ↑ Alla Pugatschowa: more successful than Dieter Bohlen , Meike Schnitzler, Jetzt.de ( Süddeutsche Zeitung ), July 28, 2001.

- ↑ The Library: Modern Russian Music ( Memento of the original from September 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , SRAS - The School of Russian and Asian Studies, accessed August 5, 2011

- ↑ "Popsa" from Russia an enrichment , reader's article; Viktor Schuhmann, Oldenburgische Volkszeitung, July 30, 2011.

- ↑ Simone Broughton, Kim Burton, Mark Ellington, David Muddyman, Richard Trillo (eds.): Weltmusik. World Music Rough Guide. JB Metzler, 2000, ISBN 3-476-01532-7 . (Chapter: Alexis Kochan and Julian Kytasty: The Bandura continued playing. The legacy of Ukraine) .

- ↑ Rock in Leningrad / St. Petersburg: Life before and after death ( memento of the original from January 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Anna Zaytseva, kultura, May 5/2006: Popular Music in Russia, May 2006 (PDF; 508 kB)

- ↑ Yuriy Gurzhy: Vodka, Garlic, Party , Der Tagesspiegel, June 13, 2011.

- ↑ Putin declared that it was necessary to be "very careful" with the ban on concerts by young people , Novaya Gazeta, December 15, 2018

- ↑ Putin fears Russian rappers , SRF Nachrichten, December 17, 2018

- ↑ Murka ( Memento of the original from March 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Uli Hufen, blog on the book Das Regime und die Dandys , October 1, 2010.

- ↑ Half of Russia listens to crooks songs , Russland-Aktuell , January 25, 2005.

- ↑ Reverie with order bells , Der Spiegel, August 14, 1948 (archive).

- ↑ "Stalin Organ" and "Katjuscha" ( Memento of the original from May 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Wolf Oschlies, shoa.de, accessed on August 5, 2011.

- ↑ Eurovision Song Contest 2009 in Moscow, Russia , russlandjournal.de, accessed on August 2, 2011.

- ↑ Eurovision Song Contest 2008: Moldova? Twelve Points! , Irving Wolther, SPON , May 20, 2008.

literature

German

- Ingo Grabowsky: Motor of Westernization. The Soviet Estrada song 1950--1975. In: Eastern Europe. 4/2012.

- Ingo Grabowsky: It is particularly aimed at the janz spicy ones. The Soviet hit of the 1960s and early 1970s. In: Boris Belge, Martin Deuerlein: Golden Age of Stagnation? Perspectives on the Soviet order of the Breznev era. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-16-152996-2 .

- Simone Broughton, Kim Burton, Mark Ellington, David Muddyman, Richard Trillo (Eds.): World Music. World Music Rough Guide . JB Metzler, 2000, ISBN 3-476-01532-7 .

- Tom Holert, Mark Terkessidis (Ed.): Mainstream of the minorities. Pop in the control society. Edition ID archive, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-89408-059-0 .

- Uli Hufen: The regime and the dandies. Russian crooks from Lenin to Putin. Rogner & Bernhard, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-8077-1057-0 .

- Uli Hufen: News from Russia: Petersburg new underground. In: Spex. 9/1995.

- Uli Hufen: A lot of money, little freedom. Neoliberalism & Counterculture in the New Moscow. In: Spex. 4/1998.

- Uli Hufen: Just being smart is not enough! In: Spex. 9/1998.

- S. Frederic Starr: Red and Hot. Jazz in Russia 1917–1990. Hannibal, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-85445-062-1 .

- Artemy Troitsky: Rock in Russia. Pop and Subculture in the USSR. Hannibal, 1989, ISBN 3-85445-046-X .

English

- Svetlana Boym: Common Places. Mythologies of Everydaylife. Harvard University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-674-14626-3 .

- David McFadyen: Red Stars. Personality and the Soviet Popular Song. McGill-Queens University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-7735-2106-2 .

- Hilary Pilkington: Russia's Youth and its Culture. London 1994, ISBN 0-415-09043-1 .

- Sabrina P. Ramet (Ed.): Rocking the State. Rock Music and Politics in Eastern Europe and Russia. Westview Press, Boulder 1994, ISBN 0-8133-1762-2 .

- Jim Riordan (Ed.): Soviet Youth Culture. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1989, 1995, ISBN 0-253-35423-4 .

- Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt: Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-1986. The Mass Media Music Scholars' Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 .

- Richard Stites: Russian Popular Culture. Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-521-36986-X .

- David-Emil Wickström: Rocking St. Petersburg: Transcultural Flows and Identity Politics in Post-Soviet Popular Music. ibidem Press, 2014, ISBN 978-3-8382-0100-9 .

Russian

- N. Bataschev: Sovetsky dzaz. Istroicheskij ocherk . Moscow 1972.

- GA Skorochodov: Zvezdy sovetskoj estrady . Moscow 1986.

- Mikail Tarevderdiev: Ja prosto zhivu , Moscow 1997.

- LO Utesov: Spasibo, serdce . Moscow 1976.

Web links

- The regime and the dandies . Uli Hufen's weblog about his book of the same name

- Russendisko.de Website of Wladimir Kaminer

- School of Russian and Asian Studies website , artist descriptions by genre, mostly modern

- The Icons of Russian Popular Music , Russia Profile, Volume 8, Summer 2011. Edition on Russian Music Culture (English; PDF; 2.5 MB)

- Modern Russian History in the Mirror of the Criminal Song , Marina Aptekman, Johnson's Russia List, January 15, 2002. Article on the history and meaning of the Russian chanson (English)