Cosworth DFV

The Cosworth DFV is a racing engine designed for Formula 1 by the British engine manufacturer Cosworth , which has been used by over 90 teams in the Formula 1 World Championship over a period of 19 years. Its development was initiated by Lotus and funded by Ford . That is why it is often referred to as the Ford DFV or Ford Cosworth DFV . With 155 world championship races won, 12 drivers 'titles and 10 constructors' titles, it is the most successful engine in the history of Formula 1. Various further developments were launched under the names DFY, DFZ and DFR until the 1990s. The DFV was also successful in other racing classes such as Formula 3000 . There were also versions for sports car racing.

History of origin

The 3 liter Formula 1

At the beginning of the 1966 season , Formula 1 received new regulations. Instead of the previous small-volume engines with a maximum displacement of 1.5 liters, naturally aspirated engines with a displacement of up to 3.0 liters were now approved. The decision of the then competent supervisory authority Commission Sportive Internationale (CSI) was made in November 1963 and was based on a proposal from the chassis and engine designers. The designers had proposed the 3.0-liter formula in the expectation that the CSI would reject it and instead set a two-liter limit as a compromise, which the designers actually preferred. Engines of this size could have been developed inexpensively by enlarging the existing 1.5-liter engines. Instead, the CSI unexpectedly took up the designers' proposal and, from 1966, introduced a displacement limit of 3.0 liters for naturally aspirated engines, for which the previous 1.5-liter engines were not a suitable basis.

Temporary emergency solutions

At the beginning of the 1966 season, only Repco , Ferrari and Maserati had developed new engines that were tailored to the new conditions. However, they were not freely available: Ferrari retained the new twelve-cylinder for its works team, Maserati exclusively equipped the Cooper works team, and from the summer of 1966 the Repco engine was used solely by the Brabham team, which had commissioned its development. There were no customer engines that complied with the new regulations because Coventry Climax , the largest supplier of freely accessible racing engines up to that point, announced its withdrawal from Formula 1 after it was taken over by Jaguar at the end of 1965.

Most teams therefore had to start the 1966 season with temporary solutions. For the most part, the engines from Coventry Climax and BRM used in the 1.5-liter formula were drilled out as much as possible, with displacements of 2.0 to 2.5 liters being achieved; in the case of the Climax FPF , some treatments even came to 2.8 liters ( Anglo American Racers and Brabham at the beginning of the season). Other emergency solutions were z. B. McLaren's reduced-displacement eight-cylinder Champ Car from Ford or Traco or sports car engines from the Italian Scuderia Serenissima , which did not achieve the level of performance of Formula 1.

Lotus, Ford and Cosworth

The British teams in particular found the engine situation to be unsatisfactory. Colin Chapman , head of the Lotus team, publicly appealed in the summer of 1965 to the auto industry and the British government to develop a powerful and readily available engine for the British teams or to support the development. From this side, however, there were no solutions. Chapman turned to Keith Duckworth , a former Lotus engineer who had run Cosworth since 1958 with Mike Costin . Cosworth was known for its racing engines for smaller motorsport classes such as Formula Junior or Formula 3 , which had been used across Europe since the early 1960s, including some in the 1.5-liter Formula 1. Keith Duckworth agreed to join Lotus to develop a Formula 1 engine. That was a new challenge for his company, which until then had not designed complete engines itself. Cosworth's Formula Junior engines (Ford 105E, MAE and SC series) were more or less intensive modifications of large series engines from the Ford Anglia and Cortina series .

Cosworth estimated development costs of £ 100,000 for the Formula 1 engine. The financing of the project was initially unclear. Chapman, whose company could not raise this amount, therefore looked for external investors. After the automobile manufacturer Ford initially refused, Aston Martin 's owner at the time, David Brown, showed interest in getting involved, but in return he asked for Cosworth to be incorporated into the David Brown Group . Keith Duckworth and Mike Costin refused. The oil company Esso was one of the other interested parties who dropped out in the course of 1965 . Ultimately, Chapman managed to win over journalist Walter Hayes , who had headed the public relations department at Ford of Britain since 1962 . With the support of Stanley Gillen , then CEO of the British Ford subsidiary, and Harley Copp , who had organized Ford's NASCAR program ten years earlier , Hayes convinced Henry Ford II of the advertising effectiveness of his own Formula 1 engine and in the fall of 1965 achieved that Ford ultimately agreed to fund the project. For Ford it was a logical further development of its own motorsport commitment, which after years in various US classes had meanwhile also led to an international presence; Ford had made a name for itself in endurance races such as the Le Mans 24-hour races, in particular with its Ferrari competitor GT40 . Ford announced the Formula 1 project in a press release in October 1965, but although Cosworth began work on the engine concept shortly afterwards, the contracts were not signed until June 1966.

The agreement with Ford also included the development of a four-cylinder engine for Formula 2 . Duckworth implemented this part before starting work on the Formula 1 engine. The Formula 2 engine was called FVA, had a cast iron Ford Cortina block and a cylinder head with four valves. Until the general availability of the BMW M12 four-cylinder in 1973, it was the standard engine of the Formula 2 European Championship and has many details similar to the later DFV eight-cylinder for Formula 1. Its conception was developed in close consultation with Lotus. Keith Duckworth largely implemented Colin Chapman's requirements and tailored the engine to the Lotus 49 .

The DFV was successful from the start. It already won the first race in which it was used. In the next races, the DFV engines went exclusively to the Lotus team. In the long term, however, Ford had no interest in an exclusive relationship with Lotus. The group saw the danger that in this case the public would see the reason for the success primarily in the chassis and not in the engine. Ford hoped for a greater advertising effect if the DFV engine won in the chassis of several manufacturers. Therefore, from 1968, Ford made the engine available to other teams against Chapman's resistance. This decision was a major reason for the almost one and a half decades of dominance of the “greatest Formula 1 engine”, which many authors believe would not have been so clear if the engine had only been used by Lotus in the following years would. For Ford, the advertising effect occurred to an unimaginable extent. Ford later described the investment as "the best £ 100,000 we've ever spent." In total, Cosworth made 400 copies of the DFV.

designation

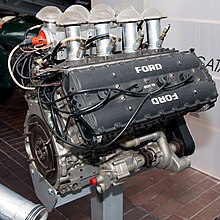

The engine is mostly referred to as a Cosworth DFV. Alternatively, the terms Ford DFV or Ford Cosworth DFV are used to indicate the financier of the project. The “Ford plum” is usually poured into the cylinder head covers; some engines used by Williams had lids with the Cosworth lettering or no logo at all.

The acronym DFV stands for D ouble F our V alve. It describes the engine as a "double four-valve" and refers to the FVA, which was only developed with the DFV. As an in-line four-cylinder, it was, as it were, a simple four-valve engine.

technology

The basic construction of the DFV

Unlike Cosworth's previous racing engines, which were based on standard engine blocks from Ford of Britain, the DFV was an in-house design. However, the structure of the DFV was influenced by some features of the Ford-Kent four-cylinder engine.

When designing new engines for the 3-liter Formula 1, most manufacturers relied on twelve-cylinder V-engines (Honda, Ferrari, Maserati, Weslake), and BRM even produced a sixteen-cylinder H-engine , although this was due to its high complexity , Susceptibility to defects and overweight found no permanent use. The DFV, on the other hand, was a V-engine with only eight cylinders. This can be explained on the one hand by the relationship to the four-cylinder FVA for Formula 2, on the other hand it was Duckworth's decision for simplicity and efficiency.

The cylinder bank angle of the DFV is 90 degrees. The displacement is 2993 cm³ (bore × stroke 85.7 × 64.8 mm). The engine block is made of an aluminum alloy. It has wet cast iron cylinder liners . The cylinder head is also made of aluminum. Each cylinder has four valves. The inlet and outlet valves are at an angle of 32 degrees to each other. They are controlled by two overhead camshafts for each cylinder bank, which are driven by gear wheels. The crankshaft has five bearings. When it was presented in 1967, the engine delivered 294 kW (400 hp), two years later the best engines had 301 kW (410 hp), and in 1972 some well-prepared DFVs already achieved 331 kW (450 hp). In 1977 the best DFV produced 353 kW (480 hp); However, they were now the weakest engines in Formula 1: Ferrari's twelve-cylinder engine at that time produced 382 kW (520 hp), Alfa Romeo's 115-12, a twelve-cylinder V-engine with a 180 ° bank angle, according to the factory, even reached 386 kW (525 Hp), and Renault's supercharged six-cylinder was 368 kW (500 hp). Cosworth's strength at the time was its reliability, which was well above that of the competing engines. At the end of its era, the DFV achieved 375 kW (510 PS), which corresponded to a deficit of around 147 kW (200 PS) on the most powerful turbo engines.

The short stroke version

In 1981 Cosworth developed a short-stroke version of the DFV, which appeared in 1982. The stroke was reduced to 58.5 mm, while the bore was enlarged to 90.0 mm. This resulted in a total displacement of 2991 cm³. With these changes, Cosworth wanted to enable higher speeds. However, this did not result in a noticeable gain in performance. The maximum power was estimated at around 500 hp. A total of 22 copies of the short-stroke DFV were created. It formed the basis for the Cosworth DFY, which was developed in the following year.

The Cosworth DFY

The 1982 Cosworth DFY was a further development of the original DFV. It was a reaction to the continuously increasing performance of the turbo engines, with which the DFV could no longer keep up. The DFY was designed under the direction of Mario Illien , who had worked for Cosworth since 1978. The British teams McLaren and Williams took over the financing primarily; Tyrrell was also involved to a lesser extent.

The DFY was based on the short-stroke DFV from 1982, whose cylinder dimensions it took over. The engine block remained unchanged. In particular, the cylinder head, which was 6.4 kg lighter than that of the conventional DFV, has undergone major revisions. The exhaust ports of the individual cylinders were now completely separated; they were only combined in the exhaust manifold. The valves were closer together now; the valve angle was only 22.5 degrees. The engine output was around 530 hp, the maximum speed was 11,500 revolutions per minute.

The DFY was short-lived and not widely used. A total of only seven copies were made. The DFY did not replace the DFV; rather, both versions were used side by side until at least 1984.

The role of the tuner

In the 1970s, Cosworth's DFV eight-cylinder engine was the most widely used power unit in Formula 1. For reasons of capacity, Cosworth could not maintain all of the engines in circulation. The service was outsourced to various independent companies at an early stage. The first of its kind was Swindon Racing Engines (Swindon or SRE for short), founded in 1972. The shares in Swindon were wholly owned by Keith Duckworth and Mike Costin and two other Cosworth employees. In the external relationship, however, John Dunn acted as managing director. Swindon was organizationally and technically independent. Over the years, Swindon began not only to maintain the DFV motors, but to develop them independently. John Judd's company Engine Developments , Hart Racing Engines , John Wyer Automotive and Langford & Peck soon joined as competitors . In the mid-1970s, Heini Mader Racing Components from Switzerland followed, with mainly continental European teams being looked after.

In the course of the 1970s, the big teams increasingly switched to servicing the engines themselves or at least working exclusively with a tuning partner. From 1973, McLaren transferred engine tuning to the company Nicholson-McLaren Racing Engines , which was founded by John Nicholson for this purpose . Williams carried out its own developments, most of which were exclusively implemented by Judd.

Racing history of the DFV in the Formula 1 world championship

Successful debut with Lotus

The first Formula 1 race of the Cosworth DFV was the Dutch Grand Prix in 1967 . Lotus launched the DFV in the Type 49 with Jim Clark and Graham Hill . Hill took pole position; his best training time was half a second below that of the runner-up. In the race, however, Hill dropped out after an engine failure. Clark, who started from eighth place, won the race 23 seconds ahead of Jack Brabham in Brabham-Repco. The DFV won the first time. Three more victories followed for Lotus this season. When it became generally available in 1968, almost all British teams gradually switched to the DFV engine: McLaren and Tyrrell started in 1968, and Brabham followed in 1969.

The most widely used engine in Formula 1

The Cosworth DFV was the dominant engine of the 1970s. The established designers almost without exception rely on the engine. The DFV was also responsible for the emergence of numerous new designers in the 1970s, because with a comparatively inexpensive DFV motor and an equally freely available Hewland transmission, a reasonably competitive car could easily be put on the wheels. One example of this was Tyrrell: In order to be able to continue using DFV motors, the team severed its connection with the previous chassis supplier Matra , who had insisted on using its own motor, and became an independent racing car designer. Not all designers worked at the same high level as Tyrrell. In the 1970s, the so-called Cosworth “modular car” was created. It referred to simply constructed vehicles with purchased technical components, including in particular DFV engines and Hewland transmissions. Such designers were, for example, Ensign , Shadow , Surtees or Frank Williams Racing Cars . The technology they bought made it possible for these midfield teams to finish in the points again and again. In addition, the Cosworth DFV also appeared in numerous amateur projects such as Connew , Kauhsen , Merzario , Trojan or Token from Europe or Maki from Japan. Most of them managed to build a racing car, but failed after a short time due to the high costs of racing. Some - such as Kauhsen or Merzario - had also underestimated the constructive complexity of Formula 1, and still others, to which z. B. Dywa from Milan , did not get beyond the level of a handicraft object. The designer March Engineering , founded in 1969, took a different approach and from 1970 onwards offered freely available customer chassis that were precisely tailored to the DFV engine. Many of these March-Cosworth customer vehicles supplemented the starter fields for the Grand Prix until the late 1970s and passed through the hands of many racing drivers over the years.

The DFV hardly had any competition during this time. Of the British teams, BRM was the only one that still produced its own engines. There were hardly any international competitors either. Ferrari's engines were intended exclusively for the company's own factory team. After its own works team had been hired, Matra supplied the Équipe Ligier alone . From 1970 onwards, Alfa Romeo tried to gain a foothold in Formula 1 with eight-cylinder engines derived from sports car engines. After these advances failed at both McLaren (1970) and March (1971), Alfa Romeo returned in 1976 with an exclusive engine for Brabham, but could not prevail here either. Small engine designers like Tecno appeared only temporarily.

Series wins

In the 1970s, the DFV also dominated sport. In its first full season, the DFV engine won 11 out of 12 races, and in 1973 every win at a world championship run went to a DFV car. In Formula 1, cars with DFV engines won a total of 155 world championship races from 1967 to 1983, the last of which were achieved with DFY versions. 12 different chassis manufacturers won world championship races with the DFV engine. By far the most successful chassis manufacturer was Lotus, followed by McLaren and Tyrrell. Frank Williams was also successful with his second racing team, Grand Prix Engineering, founded in 1977. The DFV also made it possible for small teams like Shadow or Hesketh to win individual wins under favorable circumstances. Apart from the DFV, only Ferrari engines regularly had the chance to win races in the 1970s. Wins of cars with BRM, Matra or Alfa engines remained the exception.

Displacement by turbo engines

At the end of the 1970s, however, the end of DFV dominance became apparent. With the turbo engines introduced by Renault in 1977 , competition arose whose level of performance clearly exceeded that of the DFV. With the increasing reliability of the turbos, the DFV fell noticeably behind in 1981 . This was all the more true as the leading turbo teams were using special fuels ("rocket fuel") from 1983 at the latest, through which the engine output rose to up to 1,300 hp for a short time, at least in qualifying, and several 100 hp over the DFV engines during racing .

Cosworth reacted to this by developing the DFV into the DFY. The DFY debuted with McLaren at the 1983 French Grand Prix . Little by little, Lotus, Williams, Tyrrell and Ligier also received individual DFY blocks. Shortly after its debut, the DFY engine scored a victory: Michele Alboreto won the 1983 US East Grand Prix for Tyrrell . It was the last victory of a naturally aspirated 3.0 liter Cosworth engine in the Formula 1 World Championship.

It is true that in the 1980s the FIA tried to limit the potential of the turbocharged engines through numerous rule changes on minimum weight and maximum consumption. Nevertheless, the naturally aspirated engines were no longer competitive. The DFY version of the DFV did not change this either. After all the top teams had switched to turbo engines from major manufacturers who had entered the racing scene by the end of 1983 - Brabham joined forces with BMW , Williams with Honda , and McLaren had an engine financed by TAG built by Porsche - the midfield teams followed by the summer of 1984 . ATS, Arrows and Benetton became BMW customers, Osella took over Alfa Romeo's turbo engines ( 890T ), and the British teams RAM , Spirit and Haas bought supercharged four-cylinders from Brian Hart (Hart Racing Engines), which were weaker and more fragile than the turbos of the established manufacturers, but still performed better than the DFV and DFY vacuum cleaners. The particularly financially weak teams Theodore or Fittipaldi , on the other hand, stopped racing. Minardi started his Formula 1 program in 1985 with a DFV engine, but after a few races switched to supercharged six-cylinder engines from Motori Moderni . Tyrrell was the last team that started regularly with DFV or DFY engines until the summer of 1985. In the end, however, the switch to turbo engines was inevitable here too. From 1986 Cosworth had its own turbo engine in its program, the GBA (Ford TEC); However, it was reserved exclusively for individual teams and was only used for two years.

Regardless of this, the DFV had one last, albeit extremely curious, appearance in Formula 1 at the 1988 Brazilian Grand Prix : The new BMS Scuderia Italia team had commissioned a chassis from Dallara , which was not yet completed at the season opener. In order to counteract a possible exclusion from the rest of the season, which threatened to result in a penalty if not starting, the Scuderia then entered the race with a Dallara 3087 for Alex Caffi - a Formula 3000 vehicle with a DFV engine that had been used in the previous year. Nevertheless, the vehicle was not competitive and clearly missed the pre-qualification. At the subsequent race in San Marino , the new vehicle with the DFZ engine was then ready, so that the DFV stayed with this last exception.

Championship-free Formula 1 races and local series

Formula 1 races without world championship status

In addition to the world championship races from 1967 to 1983, several Formula 1 races without world championship status took place every year. Drivers with DFV engines won a total of 30 of these races.

South African Formula 1 Championship

In the South African Formula 1 championship in the 1960s, European teams met local designers and drivers. The European designers often used the races in South Africa , Rhodesia , Southern Rhodesia and Mozambique , which did not take place in the weeks around the turn of the year, to prepare for the coming world championship season and to test their new vehicles. The South African competitors, on the other hand, who were equally approved, often used older European cars or vehicles they had designed themselves. The South African designers only followed the transition to the three-liter formula with some time lag. In many cases, they initially made do with Repco or reamed Climax motors. From 1970, however, the Cosworth DFV engine was also the standard engine for them. From 1968 onwards all champions - John Love (1968 and 1969 ) and Dave Charlton ( 1970 to 1975 ) - won their titles with DFV engines.

Aurora AFX Formula 1 Series and British Formula 1 Championship

The Aurora AFX Formula 1 series was a series held almost exclusively in the British Isles, the regulations of which were closely based on those of Formula 1. The forerunner of the series was the European Formula 5000 Championship , established in 1969 , in which 5.0-liter eight-cylinder engines of American origin were initially approved. The series came to an end in 1975. Formula Libre races took their place in 1976 and 1977 , until the Aurora AFX series was launched in 1978. In 1982 the series was finally called the British Formula 1 Championship. Here mainly young drivers drove in mostly older, used Formula 1 vehicles; but also some Formula 2 cars started.

Almost all of the Formula 1 chassis in this series were powered by Cosworth DFV engines. The only other manufacturer of Formula 1 engines represented in this series was BRM, whose outdated P207 racing car was equipped with the complicated twelve-cylinder P202 and was unsuccessful.

In the Aurora series or the British Formula 1 Championship, a total of 44 races were held from 1978 to 1982; 43 of them won drivers with DFV engines. The only exception was Jim Crawford , who won a race at Oulton Park in the fall of 1980 with a Formula 2 Chevron and an in-line Ford four-cylinder engine. The championships went to DFV pilots Tony Trimmer ( 1978 ), Rupert Keegan ( 1979 ), Emilio de Villota ( 1980 ) and Jim Crawford ( 1982 ). From 1983 the series was no longer held. Conceptually, the Formula 3000 took its place from 1985.

The DFV outside of Formula 1

Formula 3000

For 1985 the FIA reorganized the racing class below Formula 1 . The previous Formula 2 , according to which a European Championship had been announced every year since 1967 , was replaced by the newly introduced Formula 3000 . The reason for the introduction of the new class was the recent sharp rise in the costs of Formula 2, which had led to a dominance of the works teams and a continuous decline in the number of participants since the early 1980s. The Formula 3000 regulations stipulated the use of the widespread and uncomplicated 3.0-liter naturally aspirated engines that had become unusable in Formula 1 because from 1985 only turbo engines were used there. This resulted in a continued need for Cosworth DFV motors. For the Formula 3000, the engine output was reduced to around 450 hp.

According to the Formula 3000 regulations, the International Formula 3000 Championship was held in Europe from 1985 . Here the DFV was the most widespread engine up until the early 1990s. In the 1985 debut season, the engine was used exclusively, only in the following years gradually engines from Judd and Honda or Mugen entered the competition. The engines of the continental European teams were largely looked after by Heini Mader's company in Gland ; British teams, however, often had their engines serviced at Swindon. The engines prepared by Mader were considered to be of particularly high quality; During this time, Heini Mader acquired the reputation of "DFV guru". In the International Formula 3000 Championship, DFV-Motoren won 65 out of a total of 123 races from 1985 to 1993 . It wasn't until 1989 that Cosworth's dominance began to crumble when Jean Alesi won his driving title in a Reynard with a Mugen engine used by Jordan . The last championship a DFV driver won was in 1992 ( Luca Badoer for Crypton ), and the last DFV win in Formula 3000 was Pedro Lamy at the 1993 Pau Grand Prix . Cosworth's successor to the DFV in Formula 3000 was an engine with the designation AC , which was used from 1993 and was immediately successful, but disappeared again with the introduction of a Zytek- Judd standard engine for the 1996 season .

From 1989 to 1997 a British Formula 3000 championship was held annually, the regulations of which corresponded to those of the international (continental European) series, but required older chassis. The DFV engine was also the dominant engine here in the first few years.

There was also the Japanese Formula 3000 Championship (later: Formula Nippon ). Here the Cosworth engines played practically no role; engines from Honda and Yamaha dominated there .

Sports car racing

Ford P68

When new technical regulations came into force in the sports car world championship in 1968 , the DFV also became an alternative to the racing engines previously used for sports car teams. The new technical regulations resulted in a maximum displacement of 3 liters for prototypes . The first notable car with a DFV engine was the Ford P68 in 1968 . The British racing team owner and racing driver Alan Mann was the operator of the project; the very flat car was designed by Len Bailey . The initiative to build the car came from Ford Europe, which Alan Mann Racing found as a partner. Although Ford spoke of a reduced engine output in order to increase the stability of the car, the team management gave an output of 309 kW (420 hp) at 9000 / min and a maximum torque of 37.3 mkp (366 Nm) at 7000 / min on.

The P68 made its racing debut in the 1968 Brands Hatch 6-hour race . Jochen Rindt and Mike Spence's car already had an engine failure during training. The second car, which was driven by Bruce McLaren as well as Spence , failed after the race with a defective drive shaft. The project suffered a serious setback due to the serious accident of Chris Irwin at the 1000 km race on the Nürburgring in 1969 , which ended the career of the then only 26-year-old racing driver. The P68 was a faster prototype - according to the factory, the top speed was 350 km / h - but not very reliable. The last race was at the 6-hour race at Brands Hatch in 1969 , when Frank Gardner and Denny Hulme retired again with damage to the drive shaft.

Mirage racing car

In the era of the Mirage racing cars, there were several models with the Cosworth DFV engine. The first car with this V8 engine was the Mirage M3 . The M3 was the second in-house design of the team around John Wyer after the M2 , which had a V12 engine from BRM . The Spyder made its racing debut at the 1969 Watkins Glen 6 Hours , with Jacky Ickx and Jackie Oliver behind the wheel . The Cosworth engine had too little oil pressure, a circumstance that led to the failure of the car after driving 112 laps. After a steering defect at the 1000 km race in Zeltweg , Jacky Ickx won the 500 km race in Imola in 1969 with the prototype . It was the first victory for the Cosworth DFV engine in a sports car race.

1972 John Wyer Automotive became Gulf Research Racing . The team continued to receive financial support for building and running the racing cars from Gulf Oil and its head of motorsport, Grady Davies . In the winter of 1971/72 the M6 was created , an open prototype whose monocoque was made from aluminum plates. The transmission came from Hewland and the V8 engine was the DFV from Cosworth. The M6 was mainly used in the 1972 and 1973 sports car world championships. The team contested 16 races with the car model and made its debut at the 1972 Sebring 12-hour race, with Derek Bell and Gijs van Lennep at the wheel . A differential damage prevented the finish. The M6 has two wins. Derek Bell and Mike Hailwood won the Spa-Francorchamps 1000km race in 1973 . It was the first victory for the Cosworth engine in a World Sports Car Championship race. Derek Bell achieved a second overall victory at the Imola 500 km race in 1973 .

Successful Mirage racing cars were the Gulf GR7 , Gulf GR8, and Mirage GR8 . Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell won the Le Mans 24-hour race in 1975 with the GR8 . It was the first victory for a car with a Cosworth engine at Le Mans . Another Mirage with a Cosworth DFV engine was the Ford M10 that Vern Schuppan , Jean-Pierre Jaussaud , David Hobbs and Derek Bell drove at Le Mans in 1979 . Both cars could not classify.

Other manufacturers

In addition to the use of Ford itself and Mirage or Gulf, the Cosworth DFV was used in a number of other sports car prototypes of the 1970s, which were used by factory teams and privateers. Appearances in the sports car world championship took place mainly in the first half of the 1970s. Subsequently, the use of vehicles powered by this engine concentrated on individual long-distance races, mainly on the 24 Hours of Le Mans , which were largely regulated separately from the Sports Car World Championship , where the DFV engine was last used in 1986 .

The longest lasting commitment was Lola , whose vehicle types T280 (with the further developments T282, T284 and T286) and T380 relied on the DFV engine. The T280 debuted in 1972 and was only used in the World Sports Car Championship that year. There were no notable successes in this racing series, however, Joakim Bonnier had a fatal accident in such a vehicle at Le Mans in 1972 . The T280 was only able to win in less important races; Noritake Takahara won three shorter races in the Fuji Grand Champion Series at Fuji Speedway at the end of the year , and the driver duo of Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Gérard Larrousse were successful in the 1972 Paris 1000 km race . In the following years the vehicles went to private drivers; last missions and finally one more victory saw this vehicle type in 1983 in the British Thundersports series. The improved models T282, T284 and T286, which appeared in the following years, were less popular and were only used sporadically by private drivers, but the T286 achieved nominally the greatest success with a victory for Renzo Zorzi and Marco Capoferri in the 1000 km race in Monza in 1979 of this vehicle family. However, the traditional race was not part of the sports car world championship that year. The Lola T380 , which was used from 1975 onwards , did not achieve any noteworthy results.

Comparatively prominent and partly successful was Ligier's commitment , which in 1975 converted its JS2 , which had previously been powered by a Maserati V6 engine, to the larger DFV engine. With drivers Jean-Louis Lafosse and Guy Chasseuil , the team was able to achieve second place at Le Mans this year behind the Gulf GR8 of Derek Bell and Jacky Ickx. However, the traditional race was not part of the sports car world championship this year . Ligier also competed in this competition, but was largely without a chance against the more powerful vehicles from Porsche , Alfa Romeo , Alpine and Chevron . This year Ligier ended his sports car involvement in order to enter Formula 1 as Équipe Ligier the following year .

The French racing team Inaltera was more successful, using its own design called Inaltera LM from 1976 to 1978 and having it controlled by prominent drivers such as Jean-Pierre Beltoise, Henri Pescarolo , Christine Beckers and Lella Lombardi . In particular, this vehicle was quite reliable: in the 1977 Le Mans 24-hour race , all three of the team's vehicles were rated. The best result was the 4th overall place for Jean Ragnotti and Jean Rondeau , equivalent to class victory in the prototype category GTP.

It was Jean Rondeau who also used his own designs with DFV motors in the years that followed. These were called Rondeau M378 and Rondeau M379 , were only launched in Le Mans and achieved at least respectable successes: In 1978 Rondeau crossed the finish line with his team-mates Bernard Darniche and Jacky Haran in 9th place overall, which in turn meant a GTP class victory . In 1979 this scenario was repeated when Ragnotti and Darniche achieved a victory in the new S class with 5th overall. In 1980, however, Rondeau had the big hit: Although the car from Ragnotti and Pescarolo was out, the M379 from Rondeau and Jean-Pierre Jaussaud took overall victory. Another M379, driven by Gordon Spice and brothers Philippe and Jean-Michel Martin , crossed the finish line in third place. However, since this vehicle was not registered in the sports car but in the GTP class, this position also meant another class win. In the following year, 1981 , the M379 competed again at Le Mans, this time exclusively in the GTP class, but had to admit defeat to the S-Class Porsche 936 in the overall standings . In subsequent years, Rondeau sat on the related- Cosworth DFL -Motor.

The DFV motor also served as the drive for the first appearances of the Japanese racing team Dome , whose futuristically designed Dome Zero RL debuted in Le Mans in 1979. In the race, however, both cars retired after 25 and 40 laps respectively. In the years that followed, the vehicles were improved and designated as RL 80 and RL 81 and again entered the race at Le Mans. The only scored finish came in 1980, but in last place and more than 90 laps behind the winning car from Rondeau. For his subsequent experiments from 1982 onwards, Dome finally used the DFL engine, and from 1985 Toyota engines were used.

In a certain sense, however, the popularity of the Cosworth DFV in Formula 1 could also be transferred to sports cars, because throughout the 1970s there were also a number of private drivers and team bosses with their own designs who used the DFV as an engine. One of these designers was the Argentine Oreste Berta , who launched a sports car called Berta LR from 1970 to 1972. Berta, who occupied the cockpit with different Argentinian drivers, was unsuccessful with this.

The Briton Alain de Cadenet took a similar approach, piloting his own designs in 1972 and 1974 with the designation Duckhams and De Cadenet LM72. From 1977 to 1981, however, de Cadenet used a Lola chassis called De Cadenet Lola LM , which in turn was powered by the Cosworth DFV, but was much more successful in the entire World Sports Car Championship. The highlight was the 1980 season , in which de Cadenet and Desiré Wilson were able to win both the Monza 1000 km race and the Silverstone 6-hour race . Previously, de Cadenet and Wilson had already finished third in the Brands Hatch 6-hour race . However, the performance over the season was not steady enough, so that at the end of the season, de Cadenet did not get past 25th place in the drivers' championship.

In individual cases, chassis from other manufacturers were occasionally equipped with the DFV motor. So the team put Mike Coombe Racing 1974 temporarily a March a 74S with DFV engine, which otherwise mainly by BMW M12 was powered -Reihenvierzylindern. Much later, in 1985, in the Thundersports series, Team PC Automotive launched the Chevron B26, usually powered by Hart, Cosworth or Ford four-cylinders, with a DFV engine.

Another curiosity is the Ibec 308LM , sometimes also referred to as the Ibec P6 or Ibec-Hesketh 308LM . This vehicle is actually the fully clad chassis of a Hesketh 308 , a Formula 1 vehicle that was already driven in its basic form at Hesketh Racing by Cosworth DFV. This vehicle appeared from 1978 to 1981 at the endurance races at Le Mans and Silverstone, but failed in each race, if at all qualified. This vehicle was later found in the Thundersports series.

Further developments for the 3.5-liter Formula 1: Cosworth DFZ and DFR

When the FIA allowed naturally aspirated engines again from 1987 , Cosworth returned to Grand Prix racing with a 3.5 liter version of the DFV called DFZ. The DFZ was based on the Cosworth DFL, which in turn was a 3.3-liter version of the DFV intended for long-distance races. Its block was taken over; Newly designed cylinder heads were added. The DFL bore remained unchanged. By adjusting the stroke, Cosworth achieved a displacement of 3489 cm³. The injection system came from Cosworth at the factory. From 1988 the DFZ was first developed into the DFR and then the HB series.

In contrast to the 1970s, the DFZ was no longer the standard engine in Formula 1 from 1987 onwards: On the one hand, the top teams continued their exclusive engine partnerships with major manufacturers that had emerged in the turbo era (McLaren with Honda, Williams with Renault), on the other hand, there was for the smaller teams there are now competitive alternatives to the Cosworth customer engines that came from Judd, Ilmor or Lamborghini . From 1988 Cosworth concentrated on the preferred customer Benetton, for whom the DFZ was further developed into the HB series via the DFR. The other customer teams, on the other hand, were dependent on independent tuners as intermediaries between them and Cosworth. Cosworth did not allow the motors to be worked on independently, as was primarily aimed at by Osella. Initially Mader was the only tuning company for DFZ engines, later Hart, Langford & Peck and Tom Walkinshaw Racing were added. Mader had a dominant position until 1990. Mader's customers during these years included AGS (1987–1991), Scuderia Italia (1988–1990), Coloni (1987–1989), EuroBrun (1988), Larrousse (1987–1988), March (1987), Minardi (1988 -1990), Onyx or Monteverdi (1989-1990), Osella (1989) and Rial (1988-1989). The last DFR engines were used in 1991.

Further developments for other racing series

Cosworth DFW: Tasman series

For the Australian-New Zealand Tasman series, Cosworth developed a version of the DFV adapted to the local regulations in 1968. The engine called DFW had a displacement of 2.5 liters. It competed with the 5.0 liter US eight-cylinder engines, which were based on high-volume engines and were significantly cheaper than the British designs. Since the performance of the DFW engines came close to that of the American 5.0-liter machines, the DFW could not prevail in the Tasman series. In the championships in 1970 and 1971 only one car with a DFW engine appeared. It didn't affect the championship.

Cosworth DFX and DFS: Cart

For the US cart series, Cosworth developed a 2.65 liter version of the DFV, which was equipped with a turbocharger. The engine was named DFX, the last copies in a revised form with a shorter stroke were called DFS. A total of 444 DFX blocks (104 of them as a kit) and 13 DFS blocks (6 of them as a kit) were created.

In its cart days, the DFX was just as dominant as the DFV in Formula 1: The prestigious Indianapolis 500 race was won ten times in a row from 1978 to 1987 by vehicles with DFX engines, as was the drivers' championship in ten of eleven of the 1977 seasons to 1987. in total, were obtained with this engine 153 races, including a winning streak fell from 81 consecutive races in the years 1981 to 1986. the end of the DFX era in Champ Cars came when Ilmor on behalf of General Motors own supercharged Developed V8 engines that were marketed under the brand name Chevrolet , but ironically, they went back to Ilmor's experience with the DFX (and were sometimes even regarded as copies of the DFY). These engines came into use from 1986 and began to dominate from 1988. In spite of this, the Cosworth units remained in use here until 1993 .

The last victory for a DFS engine was achieved by Bobby Rahal at the 1989 Marlboro Grand Prix at the Meadowlands Sports Complex . The official successor was the XB engine, first used in 1992, which was developed by Cosworth and - analogous to the nomenclature in Formula 1 - was designated as a Ford product, was continuously developed in the following years and finally from 2003 to 2007 after the competition (Toyota , Honda) even represented a standard engine.

DFL: sports car

For sports car races, Cosworth built a total of 36 engines, designated as DFL, with a displacement of 3.3 or 3.6 liters. Some regular communication blocks were later enlarged to DFL dimensions. In the 3.5-liter era of Formula 1, small Formula 1 teams used DFL blocks in individual races. Some sources report, among other things, a DFL block in a 1993 Minardi.

The DFL-engines were from 1981 used and enabled Ford now also a score in the highest former sports car racing class, the group C . Prominent vehicles with the DFL engine included the Lola T600 , the Ford C100 , the Sauber SHS C6 and the Rondeau M382 . However, the vehicles did not achieve any notable success in the long run. Only the victories of Guy Edwards and Emilio de Villota in the T600 in the 1000 km race at Brands Hatch in 1981 and of Henri Pescarolo and Giorgio Francia in the M382 in the 1000 km race in Monza in 1982 were outstanding . After that, however, the spread of DFL engines in Group C vehicles decreased significantly. In Group C, the DFL engine was used for the last time at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1988 , when the British team Davey started in this category with a Tiga chassis, but was eliminated after just five laps.

From 1984 DFL engines were mainly used in vehicles from the second highest vehicle class, group C2. The engines were more successful here: Team Spice Engineering won the C2 championship in 1985 with vehicles from Tiga and achieved the respective class victory in four of the seven races of the season. In the following year, 1986 , Spice, who now competed with specially designed vehicles, had to admit defeat to the Ecurie Ecosse racing team , which mainly used Rover engines , but remained close on their heels with a win of the season, two second places and a third place. In addition, the DFL engine also prevailed across the board this season - many other teams relied on this engine, with the ADA Racing team winning another race with a Gebhardt chassis.

1987 therefore dominated the DFL motors, the group C2, and this year, the class win could be achieved with this engine in every race. In the team classification, Spice was again in the lead. The result was even clearer in 1988 , when Spice was able to win every race but one - in this race, the 1000 km race on the Nürburgring in 1988 , Spice only had to admit defeat to Tiga customer team Kelmar Racing , which also had one DFL engine used. In 1989 , Spice (using DFZ engines) concentrated on Group C itself, but Spice vehicles with DFL engines continued to be reported under the name Chamberlain Engineering in Group C2. This team was again able to win the title with four wins this season. The main competitor Team Mako , who fielded a Spice from last year with a DFL engine, was able to win three more races. There was another win of the season for the Tiga works team - again with a DFL engine. As a result, all C2 races since 1987 have been won with the DFL engine.

Group C2 was deleted for the 1990 season . However, this year Louis Descartes' racing team used a DFL engine in its own ALD C289 chassis. However, the vehicle was not competitive and either retired or crossed the finish line last or outside of the classification. This ended the racing history of the Cosworth DFL.

In addition to the World Sports Car Championship, DFL engines were also occasionally used in the North American-dominated IMSA GTP series . In 1982, vehicles from the GRID Racing team competed in individual races , but were largely unsuccessful. In 1983, vehicles from John Wyer's racing team Mirage were also brought to the start, but this year, too, the vehicles went largely unnoticed. The only notable result was fourth place for a grid vehicle in the 500 km race in Road Atlanta . In 1984, improved it slightly, the Italian team for which mainly Alba Engineering and the British designer Argo Racing Cars were responsible whose vehicles could show some point standings this year. The highlight was a podium finish with third place for Lyn St. James and Howdy Holmes in an Argo JM16 at the 500 km race at Watkins Glen . In 1985, however, the results did not improve, and from 1986 the DFL engines, usually reported as Ford, began to disappear from the participant lists again.

statistics

The DFV teams in the Formula 1 World Championship

From 1967 to 1985, the works teams of 41 chassis designers equipped their cars with DFV and DFY engines for world championship races. During the same period, 53 customer teams with purchased chassis and DFV engines also registered for world championship races.

Factory teams of chassis designers with DFV motors

|

|

Customer teams with DFV engines

successes

The DFV won 155 world championship races, 12 drivers and 10 constructors championships in Formula 1.

Constructors' championships in Formula 1

| Constructors World Championships | |||||

| No. | season | constructor | chassis | Points | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1968 |

|

Lotus 49 Lotus 49B |

62 | |

| 2 | 1969 |

|

Matra MS10 Matra MS80 Matra MS84 |

66 | |

| 3 | 1970 |

|

Lotus 49C Lotus 72B Lotus 72C |

59 | |

| 4th | 1971 |

|

Tyrrell 001 Tyrrell 002 Tyrrell 003 |

73 | |

| 5 | 1972 |

|

Lotus 72D | 61 | |

| 6th | 1973 |

|

Lotus 72D Lotus 72E |

96 | |

| 7th | 1974 |

|

McLaren M23 | 75 | |

| 8th | 1978 |

|

Lotus 78 lotus 79 |

86 | |

| 9 | 1980 |

|

Williams FW07 Williams FW07B |

120 | |

| 10 | 1981 |

|

Williams FW07C | 95 | |

World drivers championships in Formula 1

| World Drivers Championships | |||||

| No. | season | driver | team | chassis | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1968 |

|

|

Lotus 49 | 48 |

| 2 | 1969 |

|

|

Matra MS10 Matra MS80 Matra MS84 |

63 |

| 3 | 1970 |

|

|

Lotus 49C Lotus 72B Lotus 72C |

45 |

| 4th | 1971 |

|

|

Tyrrell 001 Tyrrell 002 Tyrrell 003 |

62 |

| 5 | 1972 |

|

|

Lotus 72D | 45 |

| 6th | 1973 |

|

|

Tyrrell 005 Tyrrell 006 |

71 |

| 7th | 1974 |

|

|

McLaren M23 | 55 |

| 8th | 1976 |

|

|

McLaren M23 McLaren M26 |

69 |

| 9 | 1978 |

|

|

Lotus 78 lotus 79 |

64 |

| 10 | 1980 |

|

|

Williams FW07 Williams FW07B |

67 (71) |

| 11 | 1981 |

|

|

Williams FW07C | 50 |

| 12 | 1982 |

|

|

Williams FW07C Williams FW07D Williams FW08 |

44 |

Victories

Cars with DFV and DFY engines won a total of 155 world championship races from 1967 to 1983.

| Cosworth DFV and DFY victories in the Formula 1 World Championship | ||||||||||||||||||

| constructor | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

4th | 5 | 2 | 6th | 5 | 7th | 3 | 1 | 5 | 8th | 1 | 47 | ||||||

|

|

3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4th | 3 | 6th | 3 | 1 | 4th | 1 | 30th | ||||||

|

|

7th | 4th | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 23 | ||||||||

|

|

5 | 6th | 4th | 1 | 1 | 17th | ||||||||||||

|

|

2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 15th | ||||||||||

|

|

3 | 6th | 9 | |||||||||||||||

|

|

3 | 2 | 5 | |||||||||||||||

|

|

1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

|

|

3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

literature

- Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , Motorbuch Verlag Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9

- David Hodges: Racing Cars from A – Z after 1945 , Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-613-01477-7

- David Hodges: A – Z of Grand Prix Cars 1906–2001 , 2001 (Crowood Press), ISBN 1-86126-339-2

- Andrew Noakes: The Ford Cosworth DFV: The inside story of F1's greatest engine , Haynes Publishing UK, 2007, ISBN 9781844253371

- Doug Nye: The Big Book of Formula 1 Racing Cars . The three-liter formula from 1966. Rudolf Müller publishing company, Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-481-29851-X .

- Graham Robson: Cosworth: The Search for Power , JH Haynes & Co Ltd, 2017, ISBN 1-84425-015-6 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Doug Nye: The Big Book of Formula 1 Racing Cars . The three-liter formula from 1966. Rudolf Müller publishing company, Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-481-29851-X , p. 11.

- ↑ Mike Lawrence: Grand Prix Cars 1945-1965 , Motor Racing Publications 1998, ISBN 1-899870-39-3 , p. 102.

- ↑ Mark Whitelock: 1½.litre Grand Prix Racing 1961-1965 - Low Power, High Tech. Veloce Publishing, 2006, ISBN 1-84584-016-X , p. 297.

- ↑ Hartmut Lehbrink, Rainer W. Schlegelmilch: McLaren Formula 1 . Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft Köln 1999. ISBN 3-8290-0945-3 , p. 13.

- ↑ Mark Whitelock: 1½.litre Grand Prix Racing 1961-1965 - Low Power, High Tech . Veloce Publishing, 2006, ISBN 1-84584-016-X , p. 316.

- ^ A b c Graham Robson: Cosworth: The Search for Power , JH Haynes & Co Ltd, 2017, ISBN 1-84425-015-6 , p. 46.

- ^ Graham Robson: Cosworth: The Search for Power , JH Haynes & Co Ltd, 2017, ISBN 1-84425-015-6 , p. 48.

- ↑ Eberhard Reuß, Ferdi Kräling: Formula 2. The story from 1964 to 1984 , Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-7688-3865-8 , pp. 36, 69–71.

- ↑ So the title of the monograph on the Cosworth DFV by Andrew Noakes: The Ford Cosworth DFV: The inside story of F1's greatest engine , Haynes Publishing UK, 2007, ISBN 9781844253371 .

- ^ NN: Keith Duckworth. www.telegraph.co.uk, December 22, 2005, accessed November 22, 2018 .

- ^ Andrew Noakes: The Ford Cosworth DFV: The inside story of F1's greatest engine , Haynes Publishing UK, 2007, ISBN 9781844253371 .

- ^ Graham Robson: Cosworth: The Search for Power , JH Haynes & Co Ltd, 2017, ISBN 1-84425-015-6 , p. 26.

- ↑ a b Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 205th

- ↑ Cimarosti: The Century of Racing , p. 199.

- ^ Graham Robson: Cosworth: The Search for Power , JH Haynes & Co Ltd, 2017, ISBN 1-84425-015-6 , p. 37.

- ^ Graham Robson: Cosworth: The Search for Power , JH Haynes & Co Ltd, 2017, ISBN 1-84425-015-6 , p. 32.

- ↑ Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 219th

- ↑ Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 244th

- ↑ https://i.pinimg.com/originals/3d/a5/7a/3da57ad62a356f86299c71ffd526fe49.jpg

- ↑ Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 278th

- ↑ a b Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 327th

- ^ Documentation on the Cosworth DFV on the website www.research-racing.de (accessed on November 23, 2018).

- ^ Graham Robson: Cosworth: The Search for Power , JH Haynes & Co Ltd, 2017, ISBN 1-84425-015-6 , p. 178.

- ^ History of the Cosworth DFV on the website www.research-racing.de, s. there the section "The Tuner" (accessed on November 8, 2018).

- ^ Tribute to John Nicholson, (accessed December 10, 2018).

- ↑ Christopher Hilton: Ken Tyrrell. Portrait of a Motor Racing Giant , Haynes Publishing, Sparkford 2002 ISBN 1-85960885 X , p. 37.

- ^ About the term: David Hodges: Rennwagen von A – Z after 1945 , Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-613-01477-7 .

- ^ David Hodges: AZ of Grand Prix Cars 1906-2001 , 2001 (Crowood Press), ISBN 1-86126-339-2 , p. 144.

- ↑ Mike Lawrence: March, The Rise and Fall of a Motor Racing Legend. MRP, Orpington 2001, ISBN 1-899870-54-7 , p. 18.

- ↑ Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 320, 327th

- ↑ Ian Bamsey: The 1000 bhp Grand Prix Cars , 1988 (GT Foulis & Co. Ltd.), ISBN 978-0854296170 , p. 7

- ↑ Doug Nye: The Big Book of Formula 1 Racing Cars. The three-liter formula from 1966 . Verlagsgesellschaft Rudolf Müller, Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-481-29851-X , p. 18.

- ↑ Yörn Pugmeister: Hard times for Brian Hart . Motorsport Aktuell, issue 31/1985, p. 8.

- ↑ Ken Stewart, Norman Reich: Sun on the Grid. Grand Prix and Endurance Racing in Southern Africa. London 1967. ISBN 1-870519-49-3 .

- ↑ David Hodges: Racing cars from A – Z after 1945 , Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-613-01477-7 , p. 49.

- ^ Reuss, Ferdi Kräling: Formula 2. The story from 1964 to 1984 , Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-7688-3865-8 .

- ^ David Hodges: Rennwagen from A – Z after 1945 , Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-613-01477-7 , p. 273.

- ^ NN: Fortification. Motorsport Magazine, October 1991, p. 46.

- ↑ Statistics of the British Formula 1 Championship on the website www.driverdb.com (accessed on November 29, 2018).

- ↑ auto motor und sport, issue 8/1968, p. 86

- ↑ About the Mirage M3

- ↑ 500 km race in Imola in 1969

- ↑ Imola 500 km race in 1973

- ↑ Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 383rd

- ^ A b Graham Robson: Cosworth: The Search for Power , JH Haynes & Co Ltd, 2017, ISBN 1-84425-015-6 , p. 190.

- ^ International Motor Sport Association 1983. In: World Sports Racing Prototypes. February 14, 2007, archived from the original on April 8, 2009 ; accessed on April 8, 2020 .

- ^ International Motor Sport Association 1984. In: World Sports Racing Prototypes. February 14, 2007, archived from the original on April 8, 2009 ; accessed on April 8, 2020 .