Franco-German War

Ruined house in Saint-Cloud , takes photos to document the war damage to 1,871 in the Paris studio of Adolphe Braun developed

| date | July 19, 1870 to May 10, 1871 |

|---|---|

| location | France and Rhenish Prussia |

| exit | German victory. During the war, the four southern German states join the North German Confederation ( Kaiserreich ) and the French Empire becomes the French Republic |

| Territorial changes | France takes the bulk of the Alsace and part of Lorraine from |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

| 519,000 men at the start of the war (total mobilized: 1,400,000 men) | 336,000 men at the beginning of the war (total mobilized: 1,600,000 men) |

| losses | |

|

44,781 killed, |

138,871 killed |

Franco-German War (1870–1871)

Weißenburg - Spichern - Wörth - Colombey - Strasbourg - Toul - Mars-la-Tour - Gravelotte - Metz - Beaumont - Noisseville - Sedan - Sceaux - Chevilly - Bellevue - Artenay - Châtillon - Châteaudun - Le Bourget - Coulmiers - Amiens - Beaune-la -Rolande - Villepion - Loigny and Poupry - Orléans - Villiers - Beaugency - Nuits - Hallue - Bapaume - Villersexel - Le Mans - Lisaine - Saint-Quentin - Buzenval - Paris - Belfort

The Franco-German War from 1870 to 1871 was a military conflict between France on the one hand and the North German Confederation under the leadership of Prussia and the southern German states of Bavaria , Württemberg , Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt, allied with it, on the other. The trigger for the war was the dispute between France and Prussia over the Spanish candidacy for the throne of Prince Leopold von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen . On July 19, 1870, France declared war on Prussia. Contrary to the expectations of the French emperor , the four southern German states entered the war. Meanwhile, the other European powers remained neutral .

Within a few weeks in the late summer of 1870, the German allies defeated large parts of the French armies. After the Battle of Sedan in northern France, Emperor Napoléon III went. captured on September 2, 1870. Thereupon a provisional national government was formed in Paris, which proclaimed the republic , continued the war and raised new armies. But even the new government was unable to turn the tide. After the fall of Paris , the French government agreed to the preliminary peace of Versailles in February 1871 . The war officially ended on May 10, 1871 with the Peace of Frankfurt .

The most important results of the war were the establishment of the German Empire and the end of the Second French Empire . Because of its defeat, France had to cede what was later known as the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine to the German Empire . This in turn led to the deepening of the “ hereditary enmity ” that lasted up to the middle of the 20th century . Almost 190,000 soldiers were killed and more than 230,000 wounded in the war. After the German-Danish War in 1864 and the German War in 1866, the conflict with France was the third and last of the German wars of unification . During its course, Baden, Bavaria, Württemberg and Hessen-Darmstadt joined the North German Confederation. With this and with the constitution of January 1, 1871 , the German Empire came into being . Also during the war, the uprising of the Paris Commune led to an internal French civil war, which was put down by the French government.

Designation and classification

The Franco-German War is also known in German-speaking countries as the War of 1870/71 . In the English-speaking world, the dispute is called Franco-Prussian War (Franco-Prussian War) after the custom of naming the side declaring the war first . The British designation particularly emphasizes the direction of the German side of the war by the Prussian government, but does not include the Prussian allies in northern and southern Germany. The term Guerre Franco-Prussienne (Franco-Prussian War) is also still represented in French research literature , but is increasingly being replaced by the term Guerre Franco-Allemande (French-German War) . In Denmark, the war was dubbed fransk-tyske krig (Franco-German War) more often from the start .

The Franco-Prussian War took place in the industrial age . Therefore, it was waged similar to the previous Crimean War (1853 to 1856), the Sardinian War (1859), the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the German War (1866) with expanded weapon technology. This found its expression in the high number of victims. Almost 190,000 soldiers were killed in the entire Franco-Prussian War. The Chassepot rifle , "long lead" - a projectile in the form of an elongated drop - and grenades inflicted new, serious wounds on the soldiers. Bone fractures caused by projectiles, the loss of limbs and exit wounds led to previously unknown war injuries.

In its second phase after the Battle of Sedan , the Franco-German War also developed features of a war against an entire people . The French government around Léon Gambetta and Charles de Freycinet called for a “guerre à outrance”, that is, for a “war to the extreme”. It introduced general conscription, raised new mass armies and intensified the struggle. This led to an increase in atrocities on both sides of the war. In the end, however, in contrast to the First World War, the politicians succeeded in asserting themselves against the military leadership and ended the war again after a relatively short time. Since the Franco-Prussian War, however, it had to be assumed that wars “would potentially be fought according to the French model with the entire national force” (Stig Förster).

prehistory

Development up to the German War

In France the memory of the defeat of the Napoleonic Empire continued. The territorial demotion of 1814/1815 was felt as a severe humiliation. The Bourbon dynasty and the July monarchy could not live up to the public expectation that the old influence would be regained . The disappointed hopes of restoring France's old position of power ultimately contributed to the presidential election of Louis Napoleon in 1848 , who four years later became Napoleon III. crowned Emperor of the French. Napoleon III had his foreign policy goal. already formulated during his time in exile. In the writing Idées Napoléoniennes , he intended to weaken or dissolve Russia and Austria-Hungary . Napoleon III wanted to replace them with liberal nation-states dependent on France. In the 1850s, Napoleon III. still show foreign policy successes ( Crimean War and Sardinian War ) in this regard. In the 1860s, however, the foreign policy setbacks increased (the French intervention in Mexico and the German War of 1866 ).

In the run-up to the German War, the Prussian Prime Minister Bismarck tried to negotiate French neutrality . Napoleon III was not averse to this, but in return for the military standstill, brought territorial expansion into discussion (e.g. parts of Belgium, the Saar region and the Palatinate). Bismarck gave Napoleon III. however, no binding guarantees for territorial compensation. Napoléon III concluded with Austria. a secret treaty that provided France with the Prussian Rhineland in return for its neutrality . Napoleon III and his circle of advisers expected a lengthy war between Austria and Prussia. Therefore, they refrained from rallying French troops for quick intervention. In view of this situation, Napoleon III tried. to exert diplomatic pressure on Prussia. One month after the decisive battle of Königgrätz , he asked the victorious Prussia for support for French territorial gains. The plans envisaged the regaining of territories that France had been allowed to keep in the First Peace of Paris in 1814 and had to cede to German states only after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

The quick conclusion of peace with Austria ultimately prevented French intervention. At the same time, the balance of power in politics shifted: Prussia annexed the northern German states of Hanover , Electorate Hesse , Nassau and the Free City of Frankfurt . The remaining northern German states joined the newly formed North German Confederation in 1867 , which further increased the political weight of Prussia. In 1860, Prussia had reached less than 50% of the French population. The North German Confederation of 1867 now had 30 million inhabitants, which was closer to the French population of 37 million. In addition, the army of the North German Confederation was a third larger than its French counterpart due to the general conscription. The call for " revenge for Sadowa " (French name of the Battle of Königgrätz) came up in France. What was meant was the disappointment in France that they had not been sufficiently rewarded for neutrality in the German war. The French Minister of War commented on the French perception with the sentence: “We are the ones who were actually beaten at Sadowa” (“C'est nous qui avons été battus à Sadowa”).

At least France ensured that Prussia was only allowed to found the federal state north of the Main line. The southern German states of Württemberg, Baden and Bavaria initially retained their state independence. From a French perspective, this was not insignificant. The three southern German states were able to muster another 200,000 soldiers in a potential war and some of them bordered directly on France. However, the national exclusion of southern Germany was ultimately politically worthless, because in August 1866 Bismarck had managed to conclude secret protective and defensive alliances (mutual defense in the event of a war of aggression) with Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden. The reason for the treaties was the new demarcation of borders, which brought the southern German governments, fearing for their sovereignty, into an emergency. They were geographically between the great powers Austria, France and the North German Confederation. The growing national movement only allowed a foreign policy orientation towards the North German Confederation.

Luxembourg crisis and rapprochement between France, Austria and Italy

After the Franco-Prussian negotiations on extensive territorial compensations failed in August 1866, the French government deviated from its original objective. She now asked Prussia to support it in the annexation of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg . In March 1867, the French government started negotiations with the Dutch king who ruled Luxembourg. William III. agreed to hand Luxembourg over to France for financial compensation (5 million guilders). But he also made the sale dependent on the approval of the Prussian monarch Wilhelm I. Bismarck then had the previously kept secret protection and defensive treaties with the southern German states printed in the Prussian State Gazette . The publication of the alliance strengthened a nationalist outrage against France in the German states. Impressed by this, the Dutch king refused to sign the treaty with France. Bismarck also appealed to the other major European powers to work for a peaceful settlement of the Luxembourg crisis. So there was a conference in London in May 1867. As a result, France had to permanently give up its claims to Luxembourg. Prussia was forced to withdraw its garrison from the fortress .

The Luxembourg crisis brought France and Austria closer together. Both great powers tried to create an alliance directed against Prussia. French diplomacy at times envisaged an expansion of the planned alliance to include Italy . However, insurmountable conflicts of interest between the three powers emerged. The Italian government in Florence (1865–1871 capital of Italy) demanded the withdrawal of French troops from Rome, which were protecting the Papal States from Italian annexation . The Italian government also claimed Austrian areas such as the Isonzo Valley and Trieste for themselves. Vienna, on the other hand, distrusted Paris. It was not prepared to support French territorial expansion into the area of the former German Confederation. For its part, the French government hoped that - although an alliance treaty with Austria and Italy ultimately failed to materialize - it would receive support in a possible war against Prussia. This assessment encouraged Paris to seek a diplomatic course of confrontation with Prussia on the question of the Spanish succession to the throne .

Spanish succession crisis and declaration of war

The question of the Spanish succession to the throne became the immediate trigger for the Franco-Prussian War. In September 1868 the military overthrew Queen Isabella II from the Spanish throne. The leaders of the coup then looked to the European ruling houses for a new king for Spain. After several rejections from Italy and Portugal, the Spanish Prime Minister Juan Prim finally turned to the Sigmaringer Line of the Hohenzollern in February 1870. The decision fell on Prince Leopold von Hohenzollern , the son of a former Prussian Prime Minister and member of the Catholic branch line of the King of Prussia who ruled Berlin. Berlin and Madrid originally planned to keep their joint project secret from the public. Political Paris was only to be informed of the candidacy for king after Leopold had been confirmed as king by the Spanish parliament . The strategy failed because a mistake crept in while decoding a telegraph message from Berlin. The Spanish government wrongly assumed that the parliamentary vote on the candidacy for king should not take place until July 9, 1870. But actually June 26th was planned - an appointment two weeks earlier. The decryption error meant that the government prematurely released parliament into the summer recess. When Juan Prim found out about the misunderstanding, he had to recall Parliament. On the occasion, he justified his decision with the Spanish candidacy for the throne, which made the matter public.

A possible enthronement of Leopold as Spanish king aroused fears in France of a new dynastic embrace, as had already existed by Habsburg monarchs in the 16th and 17th centuries. In view of the already strong opposition of the Republicans in parliament, the emperor and his government had to fear their overthrow. On July 6, 1870, the French Foreign Minister Gramont gave a speech to the legislative assembly, the Corps législatif . He accused the Prussian government of being behind the Spanish project and stated that it would be a defamation of France. Although Gramont never spoke directly of war, his rhetoric could be interpreted as a threat of war to Prussia. On July 7, 1870, Gramont ordered the French ambassador to Prussia, Vincent Benedetti , to travel to Bad Ems . King Wilhelm I and his courtly followers stayed in the city for a cure. Benedetti should ask the king to withdraw Leopold's candidacy. On July 9, 1870, Wilhelm I declared to the French ambassador that he had only supported the candidacy as head of the Hohenzollern family, but not as King of Prussia. It is a purely dynastic matter. The confession of Wilhelm I strengthened Gramont's diplomatic position in Europe. He was now able to prove beyond doubt that the Prussian government, headed by Bismarck, was involved in the Spanish project. For example, Prince Reuss , the Prussian ambassador to Russia, sent a telegram to Wilhelm that Tsar Alexander II had recommended that he give up his candidacy. On July 10, 1870, Wilhelm I finally sent a special envoy to Sigmaringen. His task was to convince Karl Anton , Leopold's father, to give up. On July 12, Karl Anton renounced the Spanish crown on behalf of his son. Paris had a great diplomatic success with it.

Diplomatic victory was not enough for Gramont. The signed declaration of renunciation concealed any Prussian participation in the Spanish succession project. For this reason, Gramont demanded a public apology from Prussia. Ambassador Benedetti was supposed to elicit a binding promise from the Prussian monarch not to support any more Spanish Hohenzollern candidacies in the future either. On July 13, 1870, Benedetti visited the monarch on the Bad Ems spa promenade. Wilhelm I reacted politely to the request, but firmly rejected it. He feared a loss of face for Prussia. As long as only one non-ruling member of the Hohenzollern dynasty publicly withdrew the candidacy, the crisis could not discredit the reputation of the entire Prussian state. The situation was different if he himself had officially made an appropriate declaration as a monarch. Wilhelm I was not prepared to forbid the accession of a Hohenzollern to the throne in Spain “forever and ever”. When Benedetti informed Gramont that the French demand had been rejected, the Foreign Minister ordered another meeting with William I on the same day. However, the monarch refused the French ambassador another audience and thus authorized the Prussian Foreign Ministry to inform both the press and the Prussian ambassadors about his meeting with Benedetti. Wilhelm's rejection and the way in which Chancellor Bismarck published it in a press release (" Emser Depesche ") sparked outrage in France and national enthusiasm in Germany. In his autobiography, Thoughts and Memories, Bismarck presented it in retrospect as if the Emser Depesche had mainly been the cause of the war. This opinion is held by many historians to this day. However, scientists like Josef Becker follow a different traditional version of what happened. The historian Leopold von Ranke wrote in his diary that the decision to go to war was made on July 12, 1870 in Berlin. On the evening of that day in the official apartment of the Prussian Prime Minister Bismarck, the Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke and Minister of War Albrecht von Roon agreed on an armed conflict.

On the evening of July 14th, 1870, thousands of people gathered in the streets and squares of Paris to demonstrate for the war. Choirs like “Nach Berlin” and “Nieder mit Preußen” could be heard. On July 15, 1870, after an eleven-hour debate, the members of the French parliament voted 245 against 10 for the taking up of war credits. Four days later, on July 19, 1870, France declared war on Prussia. In the declaration of war, the French government justified its actions by stating that "the project to elevate a Prussian prince to the Spanish throne was an undertaking directed against the territorial security of France".

Initial foreign policy situation and war goals

South German states

The diplomatic events in Bad Ems caused a change of mood in the southern German states in favor of Prussia. The majority of the public was outraged by what they considered to be excessive French demands on the Prussian king. However, the Bavarian and Württemberg governments initially left it open as to whether they would actually meet their contractual alliance obligations towards the North German Confederation in the upcoming war . Only the government of the Grand Duchy of Baden expressed its military support for Prussia from the start .

In Bavaria , the Council of Ministers held a heated debate on July 14, 1870 - just five days before the French declaration of war - about the role of the country in the looming war. A day later the government in Munich agreed to fight on the Prussian side. On July 16, 1870, the Bavarian King Ludwig II ordered the mobilization of the Bavarian Army . Munich hoped that by actively participating in the armed conflict it would have to relinquish as few sovereignty rights as possible.

The Bavarian Foreign Minister Bray-Steinburg summarized Bavaria's political options as follows:

“If we go with Prussia and it wins the war, Prussia is forced to respect Bavaria's existence. If Prussia is defeated, we may lose the Palatinate, but nothing more can happen to us, because France must always favor the independence of the individual German states; the same will happen if we remain neutral and France wins. But if Prussia wins, although we let it go against the contract, then the fate of Hanover awaits us . "

The Württemberg government also had reservations about entering the war: During the crisis in the succession to the Spanish throne, the Württemberg Prime Minister Karl von Varnbuler, with the help of the French ambassador in Stuttgart , tried to moderate the French government. This should be dissuaded from making the purely dynastic matter a national incident. It was only after the diplomatic escalation in Bad Ems that Varnbuler agreed with the Bavarian government that the alliance case was recognized. Under pressure from the street, King Karl I then had the Württemberg army mobilized. Parliament almost unanimously approved the war credits.

The Grand Duchy of Baden bordered directly on France. The government in Karlsruhe was therefore anxious not to irritate Paris during the crisis of the Spanish succession to the throne. After the war became apparent, however, only Prussia and its North German allies seemed in a position to prevent a French occupation of the country. Since the Prussian suppression of the Baden Revolution in 1849, the Baden dynasty was also very close to the Hohenzollern. The Baden mobilization began on July 15. Gramont's comment that Baden was just a “branch of Berlin” that had to be politically destroyed also caused outrage against France.

European great powers

The Emser dispatch fulfilled the purpose intended by Bismarck: France stood in isolation as the aggressor , because in the eyes of the world public the cause of war was void, and France had unnecessarily forced itself to act through excessive demands. This assessment was also reflected in the London Times. She wrote on July 16, 1870: "There can be no doubt at present about the one thing that sympathies from all over the world are now turning to the attacked Prussia".

At the start of the war, France continued to have no real ally. Bismarck won Russia over by promising to support his policy of revising the Peace of Paris of 1856 . In return, Saint Petersburg not only tolerated the Prussian armed forces against France, but also increased the pressure on Austria to remain neutral as well. Tsar Alexander II informed the Austrian government that it would otherwise send troops to Austrian Galicia . With Wilhelm I of Prussia, his uncle, the tsar saw himself dynastically connected. In addition, Saint Petersburg assumed that a Franco-Austrian victory would lead to independence unrest in the Polish territories occupied by Prussia and Russia. As a result, Russia was able to advance its step-by-step revision policy with Bismarck's help at the Pontus Conference in March 1871.

Efforts to establish an Austro-French alliance failed in 1870. In June - before the French declaration of war on Prussia - the French general Barthélémy Louis Joseph Lebrun traveled to Vienna, but could hardly get any commitments from the Austrian government. Emperor Franz Joseph declared that he would only intervene militarily if Austria had a chance of being perceived by the southern German governments as a liberator. However, precisely that scenario did not occur; In July 1870, the southern German states declared their alliance with the North German Confederation. Austrian neutrality made it possible to move all German troops to the French border. The only exception to this was the Prussian 17th Division , which was supposed to defend the Schleswig-Holstein coast against French attacks from the sea .

Paris could not count on military help from Italy either. The point of contention was still the so-called Roman question : In order to secure the sympathy of the Catholic population and the clergy in France, Napoleon III insisted. on the continuation of the papal papal state. The government in Florence, on the other hand, insisted on the occupation of Rome by Italian troops. In their opinion, Rome should become the capital of Italy. However, the French protection troops, who ensured the political sovereignty of the Pope, stood in the way of this goal. In the looming Franco-German war, Italy suddenly had the chance to occupy Rome: shortly before it declared war on Prussia, the French government agreed to withdraw its troops from the Vatican. In doing so, Paris unintentionally cleared the way for the Italian conquest of Rome. The Franco-Italian diplomacy in the run-up to the war did not have the desired effect on France because the Italian King Victor Emmanuel II only assured Paris that he would not enter into negotiations with other powers. The French government mistakenly saw this as a declaration of support. However, contrary to what was expected, Italy did not intervene in the conflict.

Britain at the time was little interested in engaging in an armed conflict on mainland Europe. In London, the changed geopolitical situation in North America was perceived as more threatening than the previous successes of Prussia. There the United States of America had only bought Alaska from the Russian Empire in 1867 , which could potentially affect the interests of the British colony of Canada . Political London also saw Prussia as a possible counterbalance to France's expansionist ambitions. British politics combined with a possible French victory the fear of a renewed domination of Paris in Europe, similar to the time of Napoleon I. London therefore shied away from a military intervention in favor of France, the former partner in the Crimean War. The main concern of the liberally dominated British government was the disruption of trade that could be expected from the war. It therefore first endeavored to achieve disarmament in both countries. The dynastic connections between the British royal family and the Hohenzollerns were also used for this purpose. After all, Crown Prince Friedrich was married to a daughter of Queen Victoria of Great Britain . The mediation attempts failed, however, which was not least due to the disarmed and comparatively limited troop strength of Great Britain.

Denmark and Belgium

Like Great Britain, Denmark also opted for neutrality. Although Copenhagen had lost the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg to Prussia and Austria in the war of 1864, it did not want to take the risk of revanchism. The Danish government feared that in such a war against Prussia German troops would take Jutland before the French reinforcements appeared. At first on its own, Denmark could not have stopped the German advance with its own military forces. In addition to these concerns, foreign policy pressure also played a role in Denmark's neutrality: The Russian tsar spoke out against Danish entry into the war, because a Franco-Danish success on the coast could have led to uprisings in Poland. In addition to Danish neutrality, the fact that French forces were quickly tied up in their own country also contributed to restricting naval warfare . For the course of the conflict, the theater of war in the North Sea and Baltic Sea was to remain militarily completely insignificant.

Since the London Protocol in 1831, Belgium was committed to neutrality in Europe. King Leopold II of Belgium stuck to this point of view. In order to be able to counter violations of neutrality, the Belgian troops were mobilized. The fact that it was not involved in the Franco-Prussian War contributed to the fact that in 1914, at the beginning of the First World War , the Belgian public again mistakenly relied on the security of their neutrality.

War aims

With the war, Paris pursued the goal of preventing German unification for reasons of power politics. Prussian striving for power should be curbed in the future and France should remain the dominant nation on the European continent. At the same time, the war seemed for the government of Napoleon III. to be a means of silencing the domestic political opposition with a military success.

At the beginning of the war, France's territorial war objectives were also set. The Kingdom of Hanover, annexed by Prussia, was to be restored, southern Schleswig was to be returned to Denmark, and the German Confederation was to be re-established. Above all, however, the possession of parts of the Prussian Rhine province for France was insisted on ( Rhine border ).

In the Peace of Prague of 1866 , France was still able to prevent the German states south of the Main border from joining the North German Confederation. As early as 1866, Bismarck speculated that “in the event of war with France, [to] break the Main Barrier immediately and [to draw] all of Germany into battle”. A successful armed conflict against Paris would also secure the previous conquests of the German-Danish War and the German War.

In August 1870 - already during the war with France - the Great Headquarters around King William I agreed on the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine. The background to this decision was to want to permanently weaken France in terms of power politics and to create a buffer zone to protect southern Germany from possible future French campaigns. The demand for the assignment of territory, which Bismarck presented to the French negotiator on September 19, 1870, was initially rejected by the latter. The Prussian war aims thus prolonged the war.

course

Strategic planning in advance (1867–1870)

On the side of the North German Confederation and the South German states, King Wilhelm I was nominally the supreme commander. In practice, however, the monarch left the chief of the general staff , Helmuth von Moltke , to plan the military operations. Moltke had been planning a possible war against France since 1867. The chief of staff planned to use the numerical superiority of troops. A rapid mobilization, combined with the transport capacities of the railway lines, should shift the campaign to French soil as quickly as possible. He then wanted to force a quick decisive battle between Metz and Strasbourg. Moltke's strategy was based on the idea of a modern cabinet war . This means that he not only wanted to weaken the opposing troops, but also wanted to destroy them completely. Strategically important places in France should be captured. Previously, warfare was mostly about hitting the enemy just enough to agree to certain peace conditions. Moltke expected that France would try to advance in the direction of the Main and thus drive a wedge between the North German Confederation and its South German allies. To prevent this scenario, he let three German armies concentrate in the Palatinate. One unit finally marched in the direction of Trier, a second in the direction of Saarbrücken and a third in the direction of Landau.

On the French side, the prevailing opinion was that they could achieve an easy and quick victory. The Minister of War, Marshal Edmond Lebœuf , placed his hopes on a quick offensive success, which France was to win through rapid mobilization and deployment. Both Napoléon III followed his assessment. as well as the vast majority of the general staff. In the international European press a military superiority of France was expected. During the Luxembourg crisis in 1867, Marshal Niel had presented an offensive plan. He wanted to push east on the front between Thionville and Trier and cut off Prussia from its southern German allies. The project would have had good prospects due to the existing railway lines and French fortresses in the area. However, Niel's plan was not pursued after the end of the Luxembourg crisis. The French general Charles Auguste Frossard brought another, defensive consideration into play in 1868. Troops were to be relocated to the cities of Strasbourg, Metz and Châlons and from there initially repulsed a Prussian attack.

In February 1870, Napoleon III then changed the On the advice of General Lebrun, the military strategy of France was renewed, since after the visit of the Austrian field marshal in Paris he reckoned with military backing from Austria. Napoleon III relocated part of his army. therefore to Metz, the others to Strasbourg. Above all, the emperor hoped to be able to occupy southern Germany from Strasbourg and win the governments over to his side. After that, the French soldiers - so the idea - would be reinforced by the Austrian emperor's troops. When war broke out, an attempt was made to use elements from all three plans. So Napoleon III split. essentially divided his army into three units. The Rhine Army was led by himself and took up positions in Metz. The other two units had their temporary bases in Alsace and Châlons. The inadequate preparation of the campaign slowed the pace of the French deployment and the mobilization and formation of troops. The numerically superior forces of the German armies were given enough time to form. The planned offensive of the French army across the Rhine was no longer possible without further ado under these conditions.

In the Franco-Prussian War, it was essential to be able to move hundreds of thousands of soldiers, horses, equipment and food to the front. In the course of the war, nearly 3 million soldiers were drafted on both sides. In the German states active conscription was applied. Between the ages of 17 and 45, every male citizen could theoretically be obliged to do military service. However, due to the lack of capacities of the military stations, a lottery procedure decided the actual deployment. Socially better off people were often able to buy themselves out of their service. The French army was composed mainly of professional soldiers. There was no general conscription. The French soldiers were experienced in combat because of their use in the Crimean War and the Sardinian War and were equipped with the highly efficient Chassepot rifle .

Parades (July, August and September 1870)

However, the French army only numbered 336,000 soldiers at the beginning of the war. She was outnumbered. Due to the lower population of France, the German states were able to recruit a little more soldiers in the long term. On July 31, 1870, 460,000 men were ready on the German side near the border. It had taken 900 trains to get them to their destinations. A total of 1,500 trains transported 640,000 soldiers, 170,000 horses and almost 1,600 artillery to the front in just three weeks up to August 12. On the French side, hardly any provisions had been made for the imminent transfer of troops. Initially there was a lack of accommodation and tents. In the beginning, only the food they had brought with them was available to the soldiers. Although 900 trains quickly transported the units to the Rhine and Moselle, the necessary equipment was still in the depots. The weapons magazines were spread across the country, so the reservists who were supposed to bring the equipment to their units first traveled across France. Then they had to find their respective units at the front. Even after the fighting had already started, some of the French troops still lacked equipment and men in September 1870.

The railroad played an essential role, especially at the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War. The Prussian side recognized their potential as a means of transport early on. Since the 1840s, the Prussian War Ministry involved them in military planning. The railroad had been an integral part of military exercises since the 1860s. In 1869 a railway department was founded within the general staff, which had contacts with the railway companies. In this way, timetables to France were available as early as the spring of 1870. Such agreements between the military management and the railway companies were not made on the French side. So it happened that trains, despite the better developed French railway network, had to turn back on the way because the troops assigned to them had not yet boarded completely.

First phase of the war up to the Battle of Sedan

The fighting began on August 2, 1870 with an advance by French troops of the Rhine Army under General Frossard. They took Saarbrücken , which was strategically rather isolated and only protected by a few Prussian troops . On August 5th, Frossard vacated Saarbrücken, suspecting strong opposing troops in the vicinity. They beat him on August 6th in the Battle of Spichern . When he withdrew, the initiative passed to the three German armies, led by Karl Friedrich von Steinmetz ( 1st Army ), Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia ( 2nd Army ) and Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm ( 3rd Army ). Further French defeats in the border battles of Weissenburg on August 4th and the Battle of Wörth initially banished the possibility of a French invasion. It became apparent that France would become the main theater of war.

The first victories were associated with high losses. In Wörth alone, more German soldiers were killed than in the war of 1866 against Austria. At the beginning of the military conflict, the German officers often still ordered traditional frontal attacks on the French positions. In doing so, they exposed the soldiers to fire from the Chassepot rifle . Since the Prussian needle guns only had a firing range that was half as long (600 meters) as their French counterparts, the German troops had to travel several hundred meters before they could return fire. The German artillery , superior in terms of firing frequency and range , was often only used at the beginning of the war after the infantry had given it a favorable position with high losses.

The French troops pushed back from the border marched to Nancy and Strasbourg to regroup there. The Army of the Rhine , led by Marshal François-Achille Bazaine , kept its position in Metz. There were to be three battles around the city between August 14th and 18th: The first encounter with the Rhine Army at Colombey-Nouilly (August 14th) ended in a draw. In the second battle at Mars-la-Tour (August 16), the German troops succeeded in cutting off Bazaine's army from the heavily fortified Verdun . This was a union with the army of Napoleon III. been foiled. On August 18, the largest and most costly battle of the entire war took place near Gravelotte . As a result of the battle, the Rhine Army withdrew behind the fortress walls of Metz and could ultimately be encircled. The trapped Rhine Army - after all, the largest troop unit in France - was no longer able to guarantee the defense of the country.

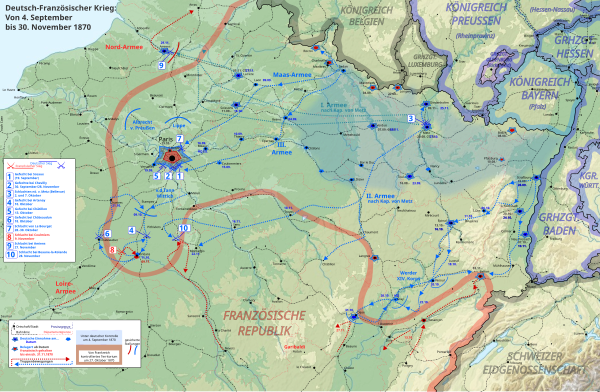

In order to lift the siege of Metz , the units assembled in the camp of Châlons under the command of Marshal Mac Mahon were set in motion. However, the 3rd Army of the Prussian Crown Prince and the Maas Army Mac Mahon followed suit. After the lost battle at Beaumont (August 30th) the French general finally abandoned the plan to relieve Metz fortress . He had his army pushed further in the direction of the Belgian border, to Sedan . The city lies in a valley, surrounded by hills to the east and north. These surveys made it possible for the German artillery to bomb the city and fortress from above on September 1st . For the first time in the Franco-Prussian War, guns served as the main weapon. It was no longer just enemy artillery that was under fire, but systematically, above all, enemy infantry. On September 2, 1870, the now also encircled Armée de Chalons surrendered . Emperor Napoleon III. got into Prussian captivity. When the news of the defeat reached Paris on September 3, the imperial regime began to collapse for good. On the night of September 4th, 28 members of parliament pleaded for a decision to abolish the monarchy. However, unrest in Paris preceded this in the course of September 4th. An insurgent crowd occupied Parliament and called for the establishment of a republic. MEPs around Léon Gambetta gave in to public pressure . They proclaimed the Third French Republic at the town hall and set up a "provisional government of national defense" to carry on the war. The disempowered Napoleon had to spend the following months in exile, in Wilhelmshöhe Castle near Kassel, before the conclusion of peace .

Continuation of the war and second phase of the war

Following the formal customs of the Cabinet War, France was defeated after the Battle of Sedan. Most of the French professional army was either taken prisoner of war (Sedan) or initially locked in the besieged fortress of Metz. The provisional government in Paris was nevertheless unable to make peace, because that would have meant agreeing to the demands made by the German side for a cession of Alsace and Lorraine. Such a loss of territory would have triggered renewed unrest in Paris and probably led to the overthrow of the new government. Negotiations between Bismarck and the French Foreign Minister Jules Favre therefore failed. The new government relied on a mass levy in the unoccupied parts of the country and tried to raise new armies . In fact, this meant that conscription was reintroduced in France.

For its part, the German General Staff planned to end the war by pushing Paris. The French capital was captured on September 19, 1870. However, there were not enough troops to storm the city. The massive fortifications of Paris and an expected street fight also spoke against a storm. Moltke hoped that the supplies in the besieged city would be used up after eight weeks and that the French government would then have to ask for peace. In fact, however, the French government, which had fled to Tours and later Bordeaux , succeeded in recruiting around a million men. On the Loire, in the north-west and south-east of France, new armies were formed for the planned liberation of Paris, albeit insufficiently trained and poorly armed. The General Staff was only able to respond significantly to this development after the fortress of Metz surrendered on October 27, 1870 and the First and Second Armies could be withdrawn.

Meanwhile, the Paris fortress governor Louis Jules Trochu made several attempts to break through the siege ring of the Germans. This was the case around September 30 at Chevilly , October 13 at Châtillon and October 28 in the suburban village of Le Bourget . The actions were badly organized and unsuccessful. In the winter of 1870, hunger, epidemics (typhus, dysentery, smallpox) and the cold made life increasingly difficult for the residents of Paris. Firewood was hardly available to heat the houses, especially for the poorer classes. 40,000 Parisians should not survive the aggravated living conditions in the city. Since the turn of the year 1870/1871 there were also casualties from artillery fire. 7,000 shells hit Paris in three weeks. The shelling of the French capital came at the urging of Bismarck, who wanted to hasten the surrender of France. As Chancellor of the North German Confederation, he feared that the other major European powers might convene a peace congress in the event of a protracted war. British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, for example, spoke of a “deep debt to France” that Prussia and its allies would incur if they actually annexed Alsace and Lorraine. The shelling of Paris also encouraged resistance in the city and damaged the reputation of German decision-makers abroad.

An immediate potential threat to the Paris siege came from the three newly established French armies: the Loire Army , the Eastern Army around Besançon and the Northern Army around Rouen . Moltke had to fight defensive battles on different fronts. Several battles took place in the region around Orléans on the Loire in particular . On October 10, 1870, a Bavarian corps withdrawn from Paris forced French forces to retreat in the battle near Artenay . Orléans was occupied the next day. The clearly outnumbered troops, however, did not prevail on November 9 in the Battle of Coulmiers against the Loire Army under the leadership of General Paladines . Orléans fell back into the hands of the French troops for the time being. On December 3, German reinforcements arrived in the region with the 2nd Army, which had withdrawn from Metz, and dispersed the Loire Army. At Le Mans , the army was finally completely defeated from January 10th to 12th, 1871. De facto, this meant that there was hardly any possibility of Paris being liberated.

The French military operations were also unable to reach the Paris siege ring from other regions: Moltke sent the 1st Army under the command of Edwin von Manteuffel to the region north of the Somme in mid-November 1870 . The troops were supposed to take action there against the northern army, which had become capable of fighting. In the Battle of Amiens on November 27, 1870, the newly established French units and Manteuffel's army met for the first time. The inadequately prepared French army was pushed back, not least because of the artillery fire that was more extensive on the German side. Shortly afterwards, the German troops advanced on Rouen and occupied the city on December 5, 1870. The planned advance to Le Havre , however, failed because Louis Faidherbe , who had meanwhile been appointed by the French government as commander in chief of the Northern Army, succeeded in building the fortress in Ham recapture. Thus, the French units briefly controlled the railway line from Reims to Amiens again, which interrupted the supply routes of Manteuffel's army in the direction of Rouen. Due to the victories in the following battles at the Hallue - a tributary of the Somme near Amiens - and at Saint-Quentin , Manteuffel was ultimately able to push the French Northern Army further away from Paris.

Civilians at war

In the occupied territories of France, the Prussian leadership introduced a military government based on the prescribed cooperation of the remaining French local governments. The civilian population was requisitioned to accommodate and supply the foreign troops. Because of the ban on the French press, there was no longer any information from their perspective. Local French politicians have sometimes been victims of reprisals from their own people. Organized requisitions by German troops caused displeasure, and in the eyes of the population came close to looting private property in places. The cities were less affected by such measures than the rural areas.

In the Franco-Prussian War, not only regular armies fought against each other. Civilians also intervened on the French side. They joined friar associations, so-called Franc-tireurs . The imperial government of Napoleon III. had inspired their formation from shooting societies. Out of bitterness over billeting and food for the German occupiers, more French civilians soon strengthened the associations. In the areas of France occupied by the German armies, they carried out actions that, firstly, impaired supplies of the enemy soldiers and, secondly, were intended to affect their morale. Mainly smaller departments, posts and couriers, but also rail, telegraph and bridge connections were attacked. The military effect was limited. "Only" about 1000 German soldiers died in clashes with the irregulars.

The German officers and soldiers did not recognize the armed civilians as combatants or legitimate combatants. The legal status of the franc tireurs was in fact hardly regulated, as the First Geneva Convention of 1864 was essentially limited to the protection of wounded soldiers. This legal loophole encouraged serious excesses on both sides. In addition to the participation of uniformed associations in the fighting, there were cases of the "abuse of hostages as human shields and [...] executions of recalcitrant civilians" (Heidi Mehrkens). The excesses of the war favored an expansion of the Geneva Conventions in the following decades. The fights for Bazeilles near Sedan made it particularly well known. On September 1, 1870, Bavarian soldiers shot and burned over 30 residents in the village. General von Senden issued a proclamation in December 1870:

“Any person who does not belong to the regular troops or the mobile guard and is found under the designation of irregulars or any other name with weapons, at the moment when he is caught red-handed while engaging in hostile acts against our troops, is regarded as a traitor and without any further legal proceedings, hanged or shot [...] all houses or villages that offer the rioters shelter and under whose protection they attack the German troops, are set on fire or shot at [...] "

The fear of franc tireurs remained in the military leadership long after the Franco-Prussian War. During the First World War, the German military justified preventive measures against the civilian population in Belgium and France by having to suppress an alleged “Franctireurskrieg”.

Empire founding

The successes achieved together on the battlefields favored a national unification process. Although Bismarck was generally not guided by public opinion, he had been working towards the establishment of the German Empire since autumn 1870 at the latest - during the war. There were several reasons for this. According to Bismarck's calculation, only an accession of the southern German states to the North German Confederation would deter France from future revanchism. In addition, the government was interested in a budget approval from the Reichstag . The elevation of Wilhelm I to German emperor promised to secure the necessary support in parliament. Bismarck's lengthy negotiations with the southern German governments ultimately proved successful, even if he had to make some concessions. In the November treaties, the southern German states committed themselves to join a German Confederation (so the official name). In return, they retained their self-administration in the postal, telegraph and rail systems. The Bavarian king remained commander in chief of his country's army in times of peace.

On December 10, 1870, the Reichstag voted for the proposal to introduce the title Kaiser in the new constitution instead of the term Presidium of the Federation . In the same act, the German Confederation was declared what would become the German Empire. The constitution did not formally enter into force until January 1, 1871. The founding of the empire was symbolically confirmed on January 18th by the proclamation of Wilhelm I as German emperor in the hall of mirrors of the Palace of Versailles near Paris. January 18th commemorated the revaluation of Frederick I as king exactly 170 years earlier. Significantly, only princes, princes and high officers were allowed to attend the ceremony. Representatives of the parliament were not invited. The French public perceived the proclamation in Versailles, the former center of power of Louis XIV , as a national humiliation . On June 28, 1919 - after Germany's defeat in World War I - the German delegation was supposed to have to sign the Versailles Peace Treaty in the same room.

End of the war and the Paris Commune

The persistent French resistance motivated Moltke to change his strategy in December 1870. The chief of staff believed that negotiations with the French government had become useless. In his view, France would have to be fully occupied in order to force a peace. The king should grant the military freedom of action - undisturbed by interference by politicians. These plans met with the resolute rejection of Bismarck, who headed for a quick compromise with the French government. After some hesitation, Kaiser Wilhelm I finally decided the conflict in Bismarck's favor. On January 23, 1871, the French government began secret armistice negotiations with Bismarck against the wishes of Interior Minister Gambetta . Here the position of the French Foreign Minister Favre prevailed, who wanted to avoid further political radicalization in enclosed Paris. On January 28, the French capital surrendered formally and a 21-day armistice came into effect, although this did not yet apply to departments in south-east France. The end of the fighting in the rest of France enabled elections to the National Assembly on February 8 . The voters favored peace advocates and, above all, secured seats in parliament for the monarchists. After the National Assembly in Bordeaux began its work on February 12, 1871, a preliminary peace was concluded in Versailles by February 26 . The treaty provided for the cession of much of Alsace and part of Lorraine. In addition, France was to pay off war indemnity by March 1874.

To clarify further details, the two states arranged negotiations in Brussels and Frankfurt am Main. In neutral Belgium, the French delegation was able to persuade the German side to reduce the reparation payments from 6 to 5 billion gold francs and prevent France from losing the Alsatian fortress town of Belfort . The French government delayed the final peace agreement in Frankfurt on May 10, 1871 for as long as possible. The tactic should increase the likelihood that other major European powers will intervene diplomatically in France's favor. However, the French government abandoned these plans after the beginning of the so-called Paris Commune and military threats from Bismarck. For the violent suppression of the revolutionary city council in Paris, the French government needed the tolerance of the German occupiers. So the French diplomats were ready to sign the peace terms now.

The formation of the Paris Commune was preceded by tensions between the monarchist-dominated National Assembly and the republican-minded capital. The government and the National Assembly met in Versailles, the former center of the Ancien Régime , from March 10, 1871 . This provoked rejection in Paris. The Committee of the Paris National Guard then sought to establish an autonomous republic. The protest of the Parisians intensified when, on March 18, 1871, government troops tried to confiscate cannons on Montmartre . The action failed and sparked an open riot. On March 26, 1871, the Parisians elected a city council, which took power over the next few months and refused to recognize the Versailles government. The so-called commune passed a series of resolutions, including the abolition of rent debts, a ban on night baking and the confiscation of religious property . In order to suppress the commune, Bismarck allowed the French government troops to be enlarged and released prisoners of war. After two months, Mac-Mahon succeeded in taking Paris. Around 20,000 Communards fell victim to the fighting in the "blood week", the "semaine sanglante".

Consequences of war

France

After the war, France was weakened. It had hundreds of thousands of casualties and wounded, lost a large part of its previous iron ore supply and lost 2 million of its inhabitants with the cession of Alsace-Lorraine . For eastern France, the end of the war did not mean an immediate return to normalcy. As agreed in the Versailles preliminary peace, German occupation troops were temporarily stationed in 19 departments until the required reparation sum had been paid. On the other hand, the German military withdrew from areas to the left of the Seine . In the Berlin Agreement of October 12, 1871, French diplomacy limited the occupation troops to 50,000 men and 6 departments. France paid the reparation installments faster than expected, so that in July 1873 the complete withdrawal of troops from France could begin.

The reconstruction of a French army made rapid progress: as early as December 1871, President Thiers announced that he was working towards a troop strength of 600,000 men. In response to this, Moltke began to prepare a possible preventive war against France in 1872. Bismarck rejected such plans, however, and stuck to his new course of isolating France in terms of alliance politics. In this way Paris should be prevented from a possible war of revenge. The question of the extent to which the forced cession of Alsace and Lorraine laid the foundations for the start of the First World War is highly controversial. Christoph Nonn believes that the annexation "blocked the possibility of reconciliation between the opponents of the war in 1870/1871". Klaus-Jürgen Bremm , on the other hand, refers to statements by prominent politicians and publicists in France who contradict such an assessment. The writer Remy de Gourmont described Alsace and Lorraine as "forgotten lands". In the following decades France - according to Bremm - tried rather to compensate for the loss of the two provinces through colonial seizures, something which Bismarck also urged. The colonial expansion of France in Africa in turn led to increased conflicts with England.

Gambetta's slogan “Pensons-y toujours, n'en parlons jamais” (“Always think about it, never talk about it”) shaped the relationship between the Third Republic and the lost provinces in the period up to the First World War. The German annexation was never completely forgotten, as numerous Alsatians and Lorraine people emigrated to Paris and founded the Association Générale d'Alsace et de Lorraine there in August 1871 . According to Julia Schroda, prominent personalities from Alsace and Lorraine succeeded in bringing a reconquest back onto the official political agenda at the beginning of the First World War. The French state gave high priority to efforts to regain the lost provinces in schools. The memory of the defeat and the pursuit of revenge were a recurring topos in the literary and political culture of the country. This had little impact on actual political decisions. The socialist politician and writer Jean Jaurès commented on the situation as Ni guerre, ni renoncement. ("Neither war, nor waiver.").

During the First World War, the return of Alsace and Lorraine was one of the war aims of France. In addition, Paris called for the formation of a belt of states on its eastern border, which should make future invasions by the German neighbor more difficult. High compensation payments were also discussed as revenge for the reparations payments from 1871 to 1873. The Versailles Treaty - both its content and the way it came about - of 1919 was shaped by the French need for revenge and laid the foundations for the far-reaching crisis of the young Weimar Republic and the rise of National Socialism . The effects of the Franco-Prussian War are not limited to French territory in Europe. In Algeria there was the Mokrani revolt , an uprising of the Algerian population against French colonial rule, which was suppressed by 1872. In Martinique , after the proclamation of the French Republic, riots occurred among the descendants of the slave population against the land-owning elite of Europeans. The unrest was quickly stopped by the armed forces stationed there.

The survival of the Third Republic proclaimed during the Franco-Prussian War still seemed uncertain until 1875. After the violent suppression of the Paris Commune, the reputation of the left wing of the Republicans was badly damaged. Orléanists and Legitimists continued to dominate parliament. While the Orléanists wanted to bring the younger line of the Bourbon dynasty back to the throne, the Legitimists favored the older line. On August 31, 1871, parliament elected Adolphe Thiers, who was politically decisive in the suppression of the Paris Commune, as French President. However, its rapprochement with republican forces was not well received by the monarchist-minded camps. In addition, Thiers refused to campaign for the restoration of the papal papal state. This cost him further sympathy among conservative circles, so that he was voted out of office by parliament on May 24, 1873. With the resignation of the president, the way seemed free for opponents of the republican form of government. Legitimists and Orléanists agreed on Henri d'Artois , the grandson of Charles X. However , he spoke out against retaining the tricolor and wanted to return to the white flag of the Bourbons, which Parliament rejected. In the years that followed, Republicans grew in influence. Finally, on January 30, 1875, Parliament voted 353 to 352 for the form of government as a republic.

Germany

With the establishment of an empire , Bismarck cemented a German empire excluding Austria-Hungary . The formation of the small German empire changed the power structure in Europe permanently. Germany replaced France as the most important continental power, which is why the former British Prime Minister Disraeli described the establishment of an empire as more momentous than the French Revolution . In 1871 the German Empire covered over 500,000 square kilometers and had about 41 million inhabitants. In terms of area and population, it was the second largest country in Europe. A few years later, Germany would also be among the world's best economically. The warlike rise of the new power aroused in many European states the fear of an even further expansion policy of Berlin. The Prussian model of general conscription for short periods of service quickly spread around the world.

The fact that the establishment of the first German nation-state was an authoritarian "birth of war" enforced by the Prussian government made it difficult to unify the empire in the following decades. German nationalism from 1871 onwards was mainly defined in terms of delimitation from France and to the exclusion of minorities, the so-called "enemies of the Reich" (Poles, Danes, Catholics and Social Democrats). The historian Eckart Conze therefore believes that "a liberal, also pluralistic nationalism had a hard time against the background [of the political founding of an empire]".

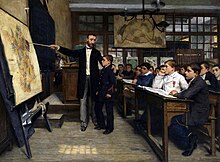

The perception of the military in civil society changed as a result of the Franco-Prussian War. The army was now seen in Germany as the midwife of national unity. Criticism of the procedure during the war, as it was expressed by some social democratic politicians, was not a majority in the population. Many military norms and behaviors flowed into everyday life. A military spirit was cultivated even in schools. At the same time, the military claimed a greater role in politics. High-ranking generals often brought calls for further armaments and preventive wars to the government. The so-called Sedan Day on September 2nd took the most prominent place in everyday life . He commemorated the battle of Sedan and the capture of Napoleon III. Although the Sedanag never developed into an officially confirmed national holiday, festive events were held at universities and schools in Prussia on its date. The warrior clubs held parades in the streets.

The French reparations were one of the triggers of the German boom in the early days . The French payments gave the German capital market additional impetus and increased the willingness of the bourgeoisie to invest. Between 1871 and 1873 around 928 joint stock companies were established. The railways as well as the steel, coal and mechanical engineering industries benefited in particular. However, the French reparations payments, which mainly flowed into the German capital market, or at least their psychological effects in connection with the simultaneous liberalization of the markets in Germany, triggered such a speculative overheating of the economy that the speculative bubble burst in the so-called founder crash in May 1873, which resulted a long-term crisis followed.

Parts of Alsace and Lorraine officially fell to the German Empire with the Peace of Frankfurt. There was no referendum on integration. The imperial law of June 9, 1871 united the two areas to form the newly created imperial state of Alsace-Lorraine . The annexation met with little approval in the affected region itself. Although the population predominantly spoke a German dialect, they harbored a French national feeling and political sympathies for France. The bourgeoisie in particular was hostile to German rule. The relative Catholic dominance of Alsace and Lorraine also corresponded more closely to the conditions in France than in the German Empire. As a result of the annexation, 130,000 residents emigrated to France. Conversely, 80,000 Germans were expelled from France.

Military Strategic Conclusions

Since rail transport was an important success factor in the German victory, the strategic rail network was further expanded with the help of French reparations payments and bonds . Since 1871, the first considerations were made about the strategic construction of the over 800 km long cannon railway from Berlin via Wetzlar and Koblenz to Metz for the effective connection of Lorraine to the German network. This line, which was built around 1878 with the help of the nationalization of railway companies, initially had hardly any civil significance.

After the war, Prussian military strategists also recognized the superiority of the French fortress system. It was recognized that ramparts with ditches and bastions made little sense, and in 1873 the Wilhelmshaven fortress plan was changed for the planned fortification of the mouth of the Jade by building numerous forts in front.

Mentality history

In both Germany and France, public opinion took an ambivalent stance on the Franco-Prussian War. Depending on the region, biography and political convictions, the war was perceived very differently. The notion of a wave of national enthusiasm that overlaps all existential worries is now considered to be refuted in research. Sections of the public in Germany welcomed the war as a means of establishing small German unity. These included students and the bourgeoisie. Catholic, democratic or socialist-minded forces rejected this type of Prussian power politics. The Jewish fellow citizens mostly took sides for the patriotic cause, because they hoped for public recognition. In southern Germany, the fear of the consequences of a possible French occupation and the uncertainty about the actual membership in the alliance first became noticeable. In France, in view of the declaration of war, the cities tended to cheer at the beginning, while the population in the rural provinces was more reserved. The outbreak of the conflict came as a surprise to the French public, but there was still great confidence in the superiority of the French army. It was expected that the fighting would mainly take place on German soil. A minority of the republican and left-wing camps in particular took to the streets with enthusiasm for the war, especially in Paris. The approval for the war was lower than in Germany.

Media such as newspapers, letters and graphics were usually propaganda in nature. Above all, the press, partly instrumentalized by the state, tried to initiate or maintain enthusiasm for war. On the French side, the newspapers first made up reports of spectacular victories over the Prussian-German armies. The Germans were later portrayed as cultureless barbarians who would attack the civilian population. The German side, in turn, staged the franc tireurs and units from French colonies as uncivilized savages. The enemy images of the press, which were picked up in this way, proved to be so powerful that they even shaped the field post letters of the fighting soldiers. After the Battle of Sedan, caricatures directed against the Germans also spread in France. In addition to the high human losses, the severe destruction of Strasbourg aroused the emotions of the French population. The occupation of Paris by Prussian troops and the imperial proclamation in Versailles also represented a national humiliation. Jean Jaurès accused France in his book La guerre franco-allemande (1870-1871) about the war with a large part of the guilt, as it was the unification over centuries thwarted his two neighbors Germany and Italy.

One type of source that is increasingly becoming the focus of research are autobiographical texts. The publications based on diaries or field post letters enable historians to reconstruct contemporary perspectives and perceptions beyond the official, political patterns of interpretation. However, the actors personally involved in the war usually only released their memories several years later. The occasion was mostly national anniversaries. The writings mostly served to promote patriotic sentiments. Also the infantryman Florian Kühnhauser wanted with his war memories of a soldier of the royal Bavarian infantry regiment from 1898 - as he wrote - "to raise the love and patriotism to the closer and wider fatherland, to promote the enthusiasm for the armed forces". Kühnhauser came from Tettenhausen in Upper Bavaria on Waginger See . He worked as a carpenter and took part in the German War as early as 1866. His report on the Franco-Prussian War shows Kühnhauser to be a supporter of what would later become the German Empire, but he does not conceal the atrocities on the battlefields and the hardships of a soldier's life.

Unlike Kühnhauser, the French diarist Geneviève Bréton belonged to the upper middle class. She lived with her parents on the Boulevard Saint-Michel in one of the posh districts of Paris. As a staunch Republican, Bréton welcomed the overthrow of the French Empire in September 1870: “A revolution [...] had never been more peaceful; not a rifle shot, not a drop of blood has flowed; the weather is good, the sun is shining, Paris is in a festive mood [...] ”. Shortly afterwards she experienced the everyday siege of Paris. In her diary, she complained that a grenade had struck only 50 meters from her home. In the middle of the war, the Parisian agreed to be engaged to the painter Henri Regnault . Shortly afterwards he fought as a national guard against the German besiegers. Despite the fighting, the couple planned to marry on March 7, 1871. However, that was not to come because Regnault was killed in the battle of Buzenval on January 19, 1871.

Everyday and social history

The war experience was very different. In the first phase of the war up to the Battle of Sedan, German and French soldiers were confronted with a war of movement . In the second phase of the war, however, their fighting style was based on the requirements of a siege war . The social position decided who got into the enemy fire and how much. Elite troops were used less often, while simpler infantry and cavalry soldiers were exposed to greater risks in combat. This applied to both the German and French troops. Differences within the regiments also existed in military training, with the number of inexperienced forces increasing on both sides in the course of the war. Certain ethical ideas such as an aristocratic code of honor linked the German and French officer ranks. This resulted in a comparatively humane treatment of prisoners of war and the wounded.

Medical care for the wounded soldiers was not always available in practice. The vast and confusing battlefields made it difficult to get help quickly, so that many soldiers succumbed to their injuries or died of thirst or starvation. The hardships remained high for the fighting. If summer temperatures and large mass battles with high losses had affected the soldiers at the beginning of the war, in the second phase of the war they suffered from many smaller skirmishes, still long marches (up to 40 kilometers a day) and an exceptionally cold winter. There was great disenchantment on the German side, as the war lasted for several months, despite the significant victory in Sedan.

reception

Popular cultural commemoration

Due to personal experiences and the major political changes, the war remained firmly anchored in the consciousness of contemporaries. Numerous monuments and memorials commemorating the fallen were erected in France, Germany, the formerly German Eupen in Belgium and Switzerland . In Germany in particular, numerous streets and squares were renamed after officers and locations of the battles. The Musée de l'Armée in Paris (2017) and the Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr in Dresden (2020) presented major special exhibitions on the Franco-German War .

After 1870 numerous war novels, autobiographies and historiographical texts appeared in Germany and France. In the case of French works in particular, the genres often cannot be strictly delimited from one another. Whether what is told is of a fictional nature or is based on actual experiences is usually left open. One of the most successful works of French war literature was Émile Zola's La Débâcle (The Collapse) . Around 190,000 copies were sold by 1897. The popular French war novels focus on, among other things, "the desperate heroism of the French troops, the sufferings of the Parisians during the siege of the city [and] the encroachments of the foreign occupation". Other French war novels took place in the future and propagated a military reconquest of Alsace and Lorraine. So far, only a few research results are available on German war literature. The only exceptions are investigations into publications by Karl May ( Die Liebe des Ulanen ) and Theodor Fontane . Fontane was active as a war correspondent. When he explored Domrémy-la-Pucelle - the birthplace of Joan of Arc - which was not occupied by Prussian troops , he was taken prisoner by the French. The writer processed his experience in the autobiography Prisoners of War . After the end of the war, Fontane visited France again in 1871, which was still partly occupied by German troops. In 1872 his travelogue from the days of the occupation was published .

On the German side, the Franco-German War was often equated with the so-called Wars of Liberation . As in 1813 - according to the narrative - the Germans once again went to war together against France in 1870. Again the fight was directed against a member of the Napoleon I dynasty . The contemporaries also thought back to the Napoleonic wars , as their fathers and grandfathers were involved in them and there was no major war between states afterwards. In particular, contemporaries made analogies between the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 and the Battle of Sedan in 1870. Alfred Spitzer, the author of the dedicatory inscription of the Völkerschlachtdenkmals in Leipzig, expressed this in 1913 - on the centenary of the battle - as follows: “Leipzig [...] was the sedan of the first Napoleon, here the principles grew out of the later that in the fight against the last Napoleon, a powerful German unitary state was founded ”. The war of 1870/1871 was therefore popularly known under the name "Leipzig - one-and-one Leipzig". In fact, the war of 1813 had little to do with a real German national war. Many Rhine Confederation states only turned away from France in the last moments of the war. According to the historian Hans-Ulrich Thamer, the Franco-Prussian War was accompanied by a shift in the national bourgeois commemorative culture: the memory of the Battle of Leipzig was still strongly shaped by ideals of political freedom and the unsolved problem of national unity. This commemorative culture, supported by the bourgeoisie, was gradually replaced annually from 1871 onwards by that of the Sedan Day on September 2 and the Emperor's birthday. This happened against the background of the establishment of the nation state and - according to Thamer - the growing concern of the bourgeoisie about a growing labor movement, against which the existing political system of the German Empire promised protection. The liberal-national component was lost in the sedan cult, which was loyal to the authorities.

As in Germany, people in France looked for historical parallels. The German invasion of 1870/1871 was compared with the penetration of the coalition armies in 1814 and 1815 and linguistically derogatory terms of the Napoleonic wars were revived. However, the intensity of the hostile attitude towards the German military could vary widely on site. Regions that were more frequently affected by billeting and seizures tended to take a more hostile position than regions of France that were less troubled or unoccupied by the war.

historiography

Historiography before the First World War

The Franco-Prussian War was a challenge for historiography in France, because several highly controversial aspects had to be dealt with in the respective political camps. From a republican, conservative, monarchist or secular perspective, the change from the Napoleonic Empire to the Republic and the Paris Commune was assessed very differently. There was no uniform, powerful pattern of interpretation. Republican-minded historians around Gabriel Monod and Ernest Renan blamed the poor organization of the army and insufficiently patriotic education in schools and universities for the French defeat. In their opinion, France had to embark on a reform course similar to that followed by Prussia after its defeat by Napoleon I.

In Pro-Prussian historiography, the Franco-German War seemed to form a unit with the German-Danish War of 1864 and the German War of 1866. The conflicts were seen as stages on the way to the Prussian-German nation-state, the so-called German wars of unification . The Franco-German War played a special role in this assessment, since in its course the French "hereditary enemy" had been overcome and the establishment of an empire took place. Historians such as Treitschke , Sybel and Droysen considered this to be “the high point of German history”. Leopold von Ranke saw the war as a break in the French hegemony that had shaped the European continent since Louis XIV. Representations critical of Prussia were unsuccessful during the German Empire, which led the Swiss cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt to comment that "the whole of world history from Adam to victorious German is being crossed out". Treitschke's German history in the 19th century played a major role in such historiography .

Historiography in the age of the world wars and the post-war period

According to Klaus-Jürgen Bremm, "historical research in Germany neglected the war of 1870/1871 for a long time since the Weimar Republic for understandable reasons". One reason for this was that many of the results of the Franco-Prussian War were reversed by the two world wars. The imperial rule of the Hohenzollern founded in 1871 came to an end in 1918, as did Alsace-Lorraine's membership of the German Empire. In the course of the German-German division after the Second World War, Germany temporarily lost its national unity. Even after reunification, the “catastrophes of the 20th century” overshadowed interest in the Franco-German War. Hermann Oncken's work Die Rheinpolitik Kaiser Napoleon III was created against the background of the discussion about Germany's responsibility for the First World War . from 1863 to 1870 and the origin of the war 1870/71 . In 1926 the historian tried to prove that France and not Prussia were to blame for the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.

After the First World War, research on the Franco-German War also changed in France. Before the First World War, it was partly about processing a defeat and justifying a possible war of revenge, the Franco-German War after 1918 was largely forgotten. A preoccupation with the First World War seemed to be far more central to French historians. Since the war of 1870/1871 was mainly fought on French soil, the French research literature is mainly localized. There are only a few overviews such as François Roth's La guerre de 1870 from 1990 or Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau's 1870. La France dans la guerre from 1989.