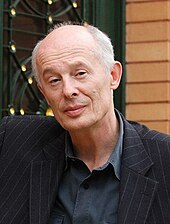

Hans Joachim Schellnhuber

Hans Joachim "John" Schellnhuber , CBE (born June 7, 1950 in Ortenburg , Passau district ) is a German climate researcher . His main areas of work are climate impact research and earth system analysis . He is one of the world's most renowned climate experts.

Until September 2018 he was director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), which he founded in 1992 and which, under his leadership, became one of the world's most respected institutes in the field of climate research. From 2009 to 2016 he was Chairman of the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU). He is a longstanding member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ( IPCC ).

Schellnhuber was one of the first to call for sustainable solutions to the climate problem and to have a decisive influence on the international political discussion. Among other things, he introduced the concept of the tilting elements to climate research and called for prompt political, economic and social measures to achieve the two-degree target , primarily through the switch from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.

Life

Schellnhuber grew up in Ortenburg in the Vilshofen district in a Protestant family. Even as a child he had the nickname "John", which family members and colleagues use to address him to this day. He attended elementary school in Ortenburg from 1956 to 1961 and then switched to the Vilshofen grammar school . According to his own statements, he had a talent for mathematics and was interested in physics, philosophy and archeology, among other things. After his older brother had already attended university, the family had no more money to enable a second child to study. However, his mother told him about the possibility of a highly gifted scholarship , which he then worked towards and graduated from high school in 1970 with a grade of 1.0.

Schellnhuber is married to the geologist , paleontologist , poet and publicist Margret Boysen, who, in addition to her journalistic work, also directs and coordinates the PIK's cultural program. He has a son born in 2008.

Schellnhuber describes himself as an agnostic .

Act

Scientific career

Immediately after graduating from high school, Schellnhuber began studying physics and mathematics at the University of Regensburg . He graduated with honors in physics in 1976 and received his doctorate in theoretical physics in 1980 with summa cum laude . Solid-state physicist Gregory Wannier became aware of Schellnhuber during a research stay at the University of Regensburg . Through his mediation, Schellnhuber received a postdoc position at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of California in Santa Barbara from 1981 to 1982 . Through this he got in contact with Walter Kohn , John Bardeen and John Robert Schrieffer , who worked there with him at the same time. He then worked as a research assistant at the University of Oldenburg , and completed his habilitation in 1985 . As a scholarship holder in the Heisenberg program , he received a visiting professorship at the Institute of Nonlinear Sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz from 1987 to 1988 .

From 1989 to 1993 Schellnhuber held a professorship for theoretical physics at the Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Sea (ICBM) at the University of Oldenburg, of which he was managing director in 1992. During this time he led a project funded by the then Federal Ministry for Research and Technology on the effects of rising sea levels on the tidal flats .

In 1992 he took over as founding director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). Under his leadership, this grew to more than 300 employees and is characterized by an interdisciplinary approach. Since 1993 he has also been a professor for theoretical physics at the University of Potsdam .

In addition to his work at PIK, Schellnhuber was professor at the Environmental School of the University of East Anglia (Great Britain) from 2001 to 2005 and was involved in the establishment of the Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research there as research director . He then worked there until 2009 as a “Distinguished Science Advisor”. From 2005 to 2009 he held a visiting professorship in physics at Oxford University , was an honorary member of Christ Church College there and was a Senior James Martin Fellow . Since 2010 he has been an external professor at the US Santa Fe Institute .

Schellnhuber has published more than 250 scientific articles and published more than 50 books or book chapters as an author, co-author or editor.

Research priorities

Schellnhuber did his doctorate in the field of solid-state physics on the band structure of crystal electrons in a homogeneous magnetic field . In his dissertation he was able to give the physical justification of the Peierls - Onsager hypothesis that had occupied physicists for decades.

During his time at the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of California at Santa Barbara , he worked on quantum mechanics . Through the contact there with Benoît Mandelbrot and Mitchell Feigenbaum , his interest shifted to non-linear dynamics ( chaos theory ), and after his return to Germany in 1984 he dealt exclusively with the analysis of complex systems . As part of his visiting professorship at the Institute of Nonlinear Sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz , he dealt with nonlinear dynamics and worked with the deputy director Michael Nauenberg .

Earth system analysis

As part of his work as director of the Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Sea in Oldenburg, he was commissioned to create a mathematical model of the Watt ecosystem and its fractal structure . His working group used the Kolmogorow-Arnold-Moser theorem . Through the son of James Lovelock , who was writing his master's thesis at the University of Oldenburg, he came into contact with Lovelock and his Gaia hypothesis . This inspired him to combine solid methodological knowledge with a “bird's eye view” in the sense of a “real systems analysis”. During this time his interest in ecosystems arose, and in connection with the conceptual planning of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research , he developed his concept of earth system analysis in the early 1990s , which he expanded further in the following years. He describes the earth system - unstable compared to “dead” planets like Venus or Mars - as a geosphere-biosphere complex (“ ecosphere ”), consisting of the components nature ( atmosphere , biosphere , cryosphere etc.) and humans .

In addition to its physiological - metabolic effects on the earth system - which correspond to those of animals - the human factor has a "metaphysical" subcomponent, the global subject , the z. B. through awareness , conquest / control of the environment and worldwide communication, e.g. B. on the Internet. The existence of the ozone hole showed that mankind is capable of strategically influencing the natural factor . Today mankind has the possibility of a macroscopic view of the earth system, for example through the principle of the bird's eye view , for example through the view from space on the earth through satellites , or through computer simulations . As a result, the global subject could e.g. B. determine its ecological footprint and consequently make collective 'rational decisions' at system level. One of the most responsible tasks is to choose the most sustainable from the multitude of possible coevolutions of man and nature .

His ideas were supported by Walter Kohn , Klaus Hasselmann , Bill Clark, Paul Crutzen , David King , Nicholas Stern and Diana Liverman , among others . The interest of some well-known American scientists (including John Holdren ) in his concept contributed to Schellnhuber's admission to the National Academy of Sciences .

On this basis, developed Schellnhuber and gentlemen, the concept of tolerance window (Engl. Tolerable Windows ) and the planetary guard rails (Engl. Planetary boundaries ), including the two-degree barrier ( two-degree target ) belongs.

Tipping elements

Around 2000, Schellnhuber brought the concept of tipping elements (Engl. Tipping Elements ) in climate research one. Building on his work on nonlinear dynamics , as one of the coordinating lead authors of Working Group II, in the third assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2001), he pointed to the previously neglected possibility of discontinuous, irreversible and extreme events in connection with global warming . Until then, linear, gradual changes had been assumed. As part of a workshop in Berlin in October 2005, possible tilting elements were discussed with 36 leading experts, followed by a survey of international experts and a literature review. The working group was able to identify nine components of the earth system that are relevant to climate policy - the so-called "tipping elements" - which could be stressed beyond a critical limit (" tipping point ") by anthropogenic influences , so that it becomes abrupt, in some cases even irreversible Change would come. Only tipping elements were taken into account here at which this critical point or tipping point could be reached before the year 2100. The following scenarios are differentiated:

- Melting arctic sea ice in summer

- Melting of the Greenland ice sheet

- Melting of the West Antarctic ice sheet

- The Atlantic thermohaline circulation slows down

- Change in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation

- Collapse of the Indian summer monsoon

- Changes in the West African monsoon system with effects on the Sahara and Sahel zone (with possibly greening of the Sahara as a positive tipping element)

- Deforestation of the tropical rainforest

- Boreal forest decline

Of these nine tipping elements, according to the experts surveyed, the melting of the Arctic sea ice and the Greenland ice sheet are currently the greatest threat. The specialist article published in February 2008 was one of the most frequently cited specialist articles in the field of geosciences in 2008 and 2009. In the meantime, further possible tilting elements have been identified.

Advice to science, politics and business

Schellnhuber is a long-standing member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and was among other things the coordinating lead author of Working Group II for the third assessment report . From 2000 to 2004 Schellnhuber was chairman of the working group Global Analysis, Integration & Modeling (GAIM) of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program , which dealt with the analysis of the earth system from a biogeochemical and climatic point of view. Under Schellnhuber's direction, the focus was on the analysis of the interaction between human society and the biogeochemical earth system. In 2003 he was the German representative of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program.

Schellnhuber is also often active in advising politics and business. Since 1992 he has been one of the nine members of the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU). Since 1994 he has been either chairman or vice-chairman of this body. From 1994 to 1998 he advised Angela Merkel in her former role as Environment Minister . In 2004, he was part of a group of climate scientists invited to visit the White House to update the Bush administration on the latest findings in climate research. In 2007, during the G8 and EU Council Presidencies, Chancellor Angela Merkel appointed him Chief Scientific Advisor to the Federal Government on issues relating to climate change and international climate policy . As a member of the “Energy and Climate Change” expert group, he has been advising the President of the EU Commission , José Manuel Barroso, since 2007 . He was supported by Barroso in 2013 newly founded addition Advisory Board on Science and Technology (English. Science and Technology Advisory Council , PSTAC) appointed. On February 15, 2013, Schellnhuber was the only scientist to speak on climate change at an informal meeting of the UN Security Council . The UN Security Council had only discussed the issue of climate change twice. In preparation for the follow -up treaty to the Kyoto Protocol , which is to be negotiated at the next UN climate conference in Paris in 2015 , the EU Commission organized a conference on April 17, 2013 at the invitation of the EU Commissioner for Climate Protection , Connie Hedegaard , to provide advice the decision maker. Schellnhuber gave the opening lecture and provided information - also here as the only scientist - about the current status of climate research.

Schellnhuber also worked several times with the World Bank . He was a member of the advisory committee for the World Development Report 2010. Under his leadership, his working group at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, together with Climate Analytics, prepared the World Bank report Turn Down the Heat: Why a 4 ° C Warmer World Must be , published in November 2012 Avoided .

Schellnhuber is a founder and now chairman of the European Knowledge and Innovation Community Climate (Engl. Climate Knowledge and Innovation Community , shortly Climate KIC ). Founded in 2010 by the European Institute for Innovation and Technology , where business and research work closely together, it funds innovations for climate protection with around half a billion euros (for example companies in the field of electromobility ). He is chairman of the Scientific Commission on Climate, Energy and Environment at the Leopoldina . From 2010 to 2012 he was Chairman of the Strategy Advisory Board of the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies , and has been Deputy Chairman of this body since 2012.

He is also a member of the Advisory Committee on Climate Change Research of the Grantham Institute for Climate Change at Imperial College London , a member of the European Academies Science Advisory Council , the Committee on Scientific Planning and Review of the International Science Council , the Global Change Advisory Group for the 7th Framework Program of the EU , the Global Agenda Council on Climate Change of the World Economic Forum , the Global Energy Assessment Council (GEA) of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), the Supervisory Board of the Stockholm Environment Institute , the Climate Justice Dialogue , an initiative of the World Resources Institute and Mary Robinson Foundation , and member of the Climate Change Advisory Board of Deutsche Bank .

On December 3, 2014, Schellnhuber presented the new WBGU report on climate protection as a global citizenship movement to the Committee on the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety of the German Bundestag .

On October 21, 2016, Schellnhuber was appointed by the EU Commission to head a nine-person high-level expert group that is supposed to explore paths to decarbonisation as part of the implementation of the Paris Agreement . After three years, the group should present a final report.

Schellnhuber has been a jury member for the Voltaire Prize since 2017 .

Climate change initiatives

As early as 1995, Schellnhuber discussed that limiting global warming to less than two degrees above the pre-industrial level could prevent dangerous consequences of climate change with a certain degree of probability - this approach was later adopted by the German government in the form of the so-called two-degree target as well as the European Union and recognized as a global goal by governments worldwide under the Copenhagen Accord of 2009. He was also involved in the development of the so-called “budget approach” for greenhouse gas emissions. In order to achieve the two-degree target , the WBGU proposed a global upper limit for carbon dioxide from fossil sources (“global budget”), which should be distributed among the individual countries according to the size of the population.

Schellnhuber also attracted international attention as the initiator of the Nobel Laureate Symposium "Global Sustainability - A Nobel Cause", at which 15 Nobel Laureates (including Murray Gell-Mann , Alan Heeger , Walter Kohn , Wangari Maathai , James Mirrlees , Mario Molina) in Potsdam and John Sulston ) the so-called Potsdam Memorandum on climate stabilization, energy security and sustainable development was formulated together with experts . The second Nobel Laureate Symposium was organized in London in 2009 by the Royal Society and was under the patronage of Prince Charles . The resulting St. James's Palace Memorandum was signed by 60 Nobel Prize winners, including Paul Crutzen , the Dalai Lama , Mikhail Gorbachev , David Gross and Paul Nurse . At the third symposium in the series in 2011 in Stockholm , members of the UN Secretary-General's High Level Panel on Sustainability came to receive a memorandum which was then fed into the preparation of the Rio + 20 conference . A “great transformation” towards a carbon-free world economy was called for, which was further elaborated in the WBGU's main report 2011 World in Transition - Social Contract for a Great Transformation . In this context, Schellnhuber organized the international WBGU symposium "Towards Low-Carbon Prosperity: National Strategies and International Partnerships" in May 2012, at which Chancellor Angela Merkel gave the opening speech. The fourth Nobel Laureate Symposium took place in Hong Kong from April 22 to 25, 2015 .

Schellnhuber is one of the initiators of the Earth League , a network of leading scientists and research institutes from over ten countries founded in February 2013 that deal with planetary processes and issues of sustainability. The aim of the network is to “develop a sound knowledge base for decision-makers on the most pressing future topics”. Members include Ottmar Edenhofer , Brian Hoskins , Mario J. Molina and Nicholas Stern .

In May 2013 Schellnhuber hosted the international, interdisciplinary conference Impacts World 2013 , which aimed to “develop a new vision for climate impact research”.

Schellnhuber's working group initiated the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISI-MIP), in which interdisciplinary models on the effects of global warming are collated and compared. More than 30 research teams from 12 countries have been involved so far. The first results of the project were published in a special edition of the journal PNAS in March 2014 and were also included in the fifth assessment report of the IPCC on the effects of climate change.

Others

Schellnhuber is a co-signer of the Potsdam Manifesto 2005 initiated by Hans-Peter Dürr , J. Daniel Dahm and Rudolf zur Lippe , which ties in with the Russell-Einstein Manifesto on the nuclear arms race .

On June 18, 2015 Schellnhuber presented together with Cardinal Peter Turkson and Metropolitan John Zizioulas in a press conference at the Vatican , the new encyclical of Pope Francis to environmental and climate protection.

Statements on climate policy

In order to achieve the two-degree target , it must be possible to limit the carbon dioxide content in the earth's atmosphere to a maximum of 450 ppm and to reach the peak of carbon dioxide emissions before 2020. These would have to be reduced to zero by 2070 and then a negative CO2 balance would have to be achieved. The key here is to renounce fossil fuels such as crude oil and coal and to switch to renewable energies . After the nuclear disaster in Fukushima , he also took an explicit position against the use of nuclear energy . Safe nuclear power plants could indeed be constructed, and even nuclear waste could theoretically be completely “defused”, but this would then no longer be economically viable. He also speaks out clearly against geoengineering in the form of influencing solar radiation ( Solar Radiation Management , SRM), as this entails incalculable risks. On the other hand, a “tolerable”, albeit costly, form of geoengineering is CO 2 sequestration , which one may not be able to do without in the long term. He also pointed out that in connection with the consequences of global warming (e.g. rise in sea levels , food and water shortages ), there could be "environmentally driven conflict constellations" that could "lead to violence or even war."

Schellnhuber calls for climate protection to become a core political issue, which he justifies with the overarching significance of climate change for many other policy areas: “You could compare the situation to a ship that has leaked on the high seas. Of course there are also problems besides this accident: the food in third class is miserable, the sailors are exploited, the band plays German hits, but when the ship goes down, all of this is irrelevant. If we can't get climate change under control, if we can't keep the ship afloat, we no longer need to think about income distribution, racism and good taste. "

Schellnhuber also repeatedly expressed himself critically with regard to the social and political reaction to the scientific findings on global warming (see also the controversy about global warming ). Among other things, he emphasized our responsibility for future generations and spoke critically of the “dictatorship of the now” and the “technology-loving comfort society.” Cool reason dictated the fight against climate change. So far, however, there has been a lack of political will. Despite the previously failed climate summit was a "capitulation" with respect to the two-degree target "premature, maybe even a bit cowardly." It is worthwhile to "fight for every tenth of a degree." Central was in the process that fossil fuels no longer subsidized are and civil society has more to speak up in the climate debate. He suggested writing the principle of sustainability in the Basic Law so that the constitutional judges can refer to it in specific disputes. In addition, from his point of view, a certain proportion of parliamentary seats should be reserved for parliamentarians who only care about the interests of future generations. Even scientists shouldn't withdraw into the ivory tower mentality. If their results play a role in the fate of entire societies, they are rather obliged to explain them to the public and to decision-makers.

He lamented a "broad campaign against the two-degree target, which is characterized by intellectual double standards and incorrect risk management". Above all, three “convenient untruths” (referring to the film An Inconvenient Truth by Al Gore ) are problematic : 1) “There is no man-made global warming”; 2) “There may be climate change, but it is harmless, if not beneficial.”; 3) “There is dangerous climate change, but the fight against it has long been lost.” It is “bizarre” how, despite contrary scientific findings, “the public debate about global warming gives space to so-called climate skeptics .” He therefore called for a larger interdisciplinary Solidarity when “the system of science as such is attacked” by climate skeptics. The attacks on climate research are (according to Benjamin Barber ) "anti-enlightenment" and "carried out in the same spirit as the struggle of biblical followers of creation doctrine against the science of the origin of species developed by Darwin ."

Schellnhuber also reports on the negative experiences that climate scientists have to make due to an aggressive scene of climate change deniers. He once said: “I have a group of persistent persecutors, small but completely insane. Wherever I go, Australia, Sweden, Berlin, they demonstrate against me and abuse me. […] There are people who hold up photomontages that show me with a hangman's noose around my neck. "

At the beginning of April 2016, Schellnhuber criticized the AfD's climate-skeptical position . In particular, one does not believe that carbon dioxide really plays a decisive role in the climate system, which is a “crazy thing” that “is not harmless”. If such tendencies prevailed in Germany as the AfD in Germany or Donald Trump in the USA represent, then “there will be no more salvation for the global climate”. He can only hope and firmly believe that the majority of voters will continue on the path of reason.

In a speech at the Federal Delegates' Conference of the Greens in Berlin at the end of November 2017, Schellnhuber presented his idea of a climate passport , which was strongly applauded by the party congress delegates, to the public for the first time : everyone who has to leave their home country because of climate change should travel to one of the countries and stay there that are the main causes of climate change.

Public impact and controversy

In a ranking of the 500 most important intellectuals in German-speaking countries, compiled by Max A. Höfer on behalf of the magazine Cicero , Schellnhuber was ranked 207. According to the Frankfurter Rundschau , his numerous statements and appearances in the media led, among other things, to “resentment among some colleagues”. Hans von Storch accused him of interfering with daily politics with specific political demands. The federal government should “consider whether this type of interference is what it pays science for”.

The renewed nomination of Schellnhuber for the chairmanship of the WBGU met with opposition from the Federal Ministry of Economics under the direction of Philipp Rösler ( FDP ) in 2013 . After the end of the last term of office (February 2013), the appointment of the WBGU members was therefore pending for about two months. Spiegel Online commented on the fact that the last major WBGU report reads World in Transition - Social Contract for a Great Transformation “like Schellnhuber in its purest form”. The Süddeutsche Zeitung suspected that the proposals made in the WBGU report on a world without fossil fuels "Rösler's strategists have long been suspicious". Members of the CDU , SPD and the Greens , including Federal Environment Minister Peter Altmaier (CDU), sharply criticized the process (delaying Schellnhuber's appointment), which was described, among other things, as "bullying", at the beginning of May. A few days later the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) reported that Philipp Rösler had decided "not to follow the previous reservations of the specialist level of his company" and to "forego" an objection to Schellnhuber's appointment to the WBGU. On May 8, 2013, Schellnhuber was confirmed in his office until October 2016.

In addition, Schellnhuber was also received in the political controversy about global warming . Joachim Wille commented in the Frankfurter Rundschau that Schellnhuber is not afraid to “become popular”, which makes the “notorious ' climate skeptics '” “flush with anger”. Schellnhuber himself reported how a man held a hangman's rope at him during a lecture in Melbourne , and warned of an increasingly threatening atmosphere for climate researchers. As the FAZ writes, however, he mostly ignores attacks against himself. According to Schellnhuber, these are often expressed anonymously on the Internet or by “self-appointed experts”, and that it is only a “small sample”. The problem with this is that you (as a recipient) do not really have the opportunity to assess which criticism is profound and which is less profound. Science has "become so complicated that large parts of the population can no longer follow it". In the past, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) has been accused of neglecting the arguments of climate skeptics. According to Spiegel Online , Schellnhuber has “nothing against professional exchange” with the climate skeptics at EIKE , “as long as their representatives adhere to the rules of scientific practice”. At Schellnhuber's invitation, several representatives from EIKE presented their arguments at a meeting in April 2011. From the perspective of the PIK researchers, this did not result in any significant new findings. However, Schellnhuber refused to sit on a political podium with EIKE representatives. This would give laypeople the impression that “experts are arguing on an equal footing”.

Awards and memberships

After graduating from high school in 1970, which he graduated with a grade of 1.0, Schellnhuber received a highly gifted scholarship from the Free State of Bavaria . After his habilitation, he received a Heisenberg grant from the German Research Foundation , under which he was visiting professor at the Institute of Nonlinear Sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz from 1987 to 1988 . Shortly after taking up his professorship at the Environmental School of the University of East Anglia (Great Britain), he received the Wolfson Research Award from the Royal Society in 2002 for his interdisciplinary approach to solving complex problems in the field of climate science and was accepted into the Royal Society as a Research Fellow.

For his achievements in climate research and his commitment to establishing the Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research and the scientific relationship between Great Britain and Germany, he was awarded the title of Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) by Queen Elizabeth II in 2004. awarded. In the same year Schellnhuber was accepted into the National Academy of Sciences because of his work on Earth system analysis .

In 2007 he received the German Environment Prize for his scientific and political contributions to solving the climate problem . For his contributions to the national and international discussion on climate change, Schellnhuber was awarded the Order of Merit of the State of Brandenburg in 2008 by Prime Minister Matthias Platzeck . In addition, he received the BAUM environmental award for his “comprehensive commitment to research into all aspects of climate change and for having anchored the importance of global environmental changes in the public and political consciousness”. Since he made the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), which he founded, into a leading international center in the research field of Earth system analysis, he was appointed Science Ambassador for the State of Brandenburg in 2009 .

Due to his contributions to the national and international "change in awareness in climate policy" and his "active and important role in science-based policy advice and knowledge transfer to the public", he was awarded the Federal Cross of Merit 1st class by Federal President Christian Wulff in 2011 . He was awarded the 2011 Volvo Environment Prize for his exceptional global role model in the intellectual and conceptual development of Earth System Science . In the same year he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Copenhagen and the following year an honorary doctorate from the Technical University of Berlin . Schellnhuber has been a member of the National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina since 2007 . He is also an "External Scientific Member" at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology and a member of the Leibniz Society of Sciences in Berlin , the Geological Society of London , the international research company Sigma Xi and the Academia Europaea . Since 2014 he has been a cultural prize winner of the Passau district and an honorary citizen of his home town of Ortenburg.

On June 17, 2015, in the run-up to the presentation of his encyclical Laudato si ' , Pope Franziskus appointed Schellnhuber as a full member of the 80 members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences for life . In June 2017 he also received the Blue Planet Prize for his contributions to the development of Earth system science and the scientific foundation of the now internationally agreed two-degree limit . Schellnhuber is also a member of the Board of Trustees of the Generations Foundation, which is committed to a sustainable future and intergenerational justice, and was one of the first to sign the Generations Manifesto of the Generations Foundation.

Fonts (selection)

Books

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Horst Sterr (Hrsg.): Climate change and coast. Insight into the greenhouse . Springer, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-77777-6 (first edition: 1993, reprint of the 1st edition).

- Hans-Joachim Schellnhuber, Volker Wenzel (Ed.): Earth System Analysis: Integrating Science for Sustainability . Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1998, ISBN 3-642-52354-4 .

- Armin Bunde , Jürgen Kropp, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber (eds.): The Science of Disasters. Climate Disruptions, Heart Attacks, and Market Crashes . Springer, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-62531-2 (first edition: 2002).

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Paul J. Crutzen , William C. Clark, Martin Claussen, Hermann Held (Eds.): Earth System Analysis for Sustainability . MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, London, UK 2004, ISBN 0-262-19513-5 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Wolfgang Cramer , Nebojsa Nakicenovic, Tom Wigley, Gary Yohe (eds.): Avoiding Dangerous Climate Change . Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-86471-8 .

- Lutz Wicke , Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Daniel Klingenfeld: The 2 ° max climate strategy - a memorandum . LIT, 2010, ISBN 978-3-643-10817-3 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Mario J. Molina , Nicholas Stern , Veronika Huber, Susanne Kadner (eds.): Global Sustainability - A Nobel Cause . Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Jürgen P. Kropp , Hans Joachim Schellnhuber (Ed.): In Extremis: Disruptive Events and Trends in Climate and Hydrology . Springer Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-14863-7 .

- Katherine Richardson , Will Steffen, Diana Liverman et al. (incl. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber): Climate Change: Global Risks, Challenges and Decisions . Cambridge University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-521-19836-3 .

- Stefan Rahmstorf , Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Climate change . Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63385-0 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Europe's Third Industrial Revolution . Diederichs Digital, 2014, ISBN 978-3-641-14957-4 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Self-immolation. The fatal triangular relationship between climate, humans and carbon . C. Bertelsmann, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-570-10262-6 .

Articles in trade journals (first authorship)

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: 'Earth system' analysis and the second Copernican revolution . In: Nature . 402 (Supplement), No. 6761, 1999, pp. C19-C23.

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Kyoto: no time to rearrange deckchairs on the Titanic . In: Nature . 450, No. 346, 2007. doi : 10.1038 / 450346c .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Global warming: Stop worrying, start panicking? . In: PNAS . 105, No. 38, 2008, pp. 14239-14240. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0807331105 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Tipping elements in the Earth System . In: PNAS . 106, No. 49, 2009, pp. 20561-20563. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0911106106 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: The road from Copenhagen: the experts' views . In: Nature Reports Climate Change . January 28, 2010. doi : 10.1038 / climate.2010.09 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Tragic Triumph . In: Climatic Change . 100, No. 1, 2010, pp. 229-238. doi : 10.1007 / s10584-010-9838-1 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Geoengineering: The good, the MAD, and the sensible . In: PNAS . 108, No. 51, 2011, pp. 20277-20278. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1115966108 .

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Katja Frieler, Pavel Kabat: The elephant, the blind, and the intersectoral intercomparison of climate impacts . In: PNAS . 111, No. 9, March 2014, pp. 3225-3227. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1321791111 . PMID 24347641 .

Articles in journals (as co-author)

- Timothy M. Lenton, Hermann Held, Elmar Kriegler, Jim W. Hall, Wolfgang Lucht , Stefan Rahmstorf, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Tipping elements in the Earth's climate system . In: PNAS . 105, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1786-1793. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0705414105 .

- Elmar Kriegler, Jim W. Hall, Hermann Held, Richard Dawson, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Imprecise probability assessment of tipping points in the climate system . In: PNAS . 106, No. 13, 2009, pp. 5041-5046. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0809117106 .

- Johan Rockström , Will Steffen, Kevin Noone, Åsa Persson, F. Stuart Chapin, Eric F. Lambin, Timothy M. Lenton, Marten Scheffer, Carl Folke , Hans Joachim Schellnhuber et al .: A safe operating space for humanity . In: Nature . 461, 2009, pp. 472-475. doi : 10.1038 / 461472a .

- Walt V. Reid, Deliang Chen, Leah Goldfarb, Heide Hackmann, Yuan T. Lee , Khotso Mokhele, Elinor Ostrom , Kari Raivio, Johan Rockström, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Anne Whyte: Earth System Science for Global Sustainability: Grand Challenges . In: Science . 330, No. 6006, 2010, pp. 916-917. doi : 10.1126 / science.1196263 .

- Peter H. Gleick, et al. (incl. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber): Climate Change and the Integrity of Science . In: Science . 328, No. 5979, 2010, pp. 689-690. doi : 10.1126 / science.328.5979.689 .

- Matthias Hofmann, Boris Worm, Stefan Rahmstorf, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Declining ocean chlorophyll under unabated anthropogenic CO2 emissions . In: Environmental Research Letters . 6, No. 034035, 2011. doi : 10.1088 / 1748-9326 / 6/3/034035 .

- Jonathan F. Donges, Reik V. Donner, Martin H. Trauth, Norbert Marwan, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Jürgen Kurths : Nonlinear detection of paleoclimate-variability transitions possibly related to human evolution . In: PNAS . 108, No. 51, 2011, pp. 20422-20427. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1117052108 .

- Jérôme Dangerman, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Energy systems transformation . In: PNAS . 110, No. 7, 2013, pp. 549-558. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1219791110 .

- Dirk Olonscheck, Matthias Hofmann, Boris Worm, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Decomposing the effects of ocean warming on chlorophyll (a) concentrations into physically and biologically driven contributions . In: Environmental Research Letters . 8, No. 014043, 2013. doi : 10.1088 / 1748-9326 / 8/1/014043 .

- Vladimir Petoukhov, Stefan Rahmstorf, Stefan Petri, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Quasiresonant amplification of planetary waves and recent Northern Hemisphere weather extremes . In: PNAS . 110, No. 14, 2013, pp. 5336-5341. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1309353110 .

- Josef Ludescher, Avi Gozolchiani, Mikhail I. Bogachev, Armin Bunde , Shlomo Havlin , Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Improved El Niño-Forecasting by Cooperativity Detection . In: PNAS . 110, No. 29, 2013, pp. 11742-11745. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1309353110 .

- Franziska Piontek, et al. ( incl.Hans Joachim Schellnhuber): Multisectoral climate impact hotspots in a warming world . In: PNAS . 119, No. 9, 2013, pp. 3233-3238. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1222471110 .

- Johan Rockström et al .: A roadmap for rapid decarbonization . In: Science . tape 355 , no. 6331 , 2017, p. 1269-1271 , doi : 10.1126 / science.aah3443 .

- Will Steffen et al .: Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . tape 115 , no. 33 , 2018, p. 8252-8259 , doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1810141115 .

Reports

- Renate Schubert, Hans-Joachim Schellnhuber et al .: World in Transition: The Security Risk Climate Change . Main report, WBGU, Berlin, 2007, ISBN 978-3-540-73247-1 (English Climate Change as a Security Risk , Taylor and Francis, 2013, ISBN 978-1-136-53564-2 ).

- Hans-Joachim Schellnhuber et al .: Solving the climate dilemma - The budget approach (Engl. Solving the Climate Dilemma: The Budget Approach ). Special report. WBGU, Berlin, 2009, ISBN 978-3-936191-26-4 .

- Hans-Joachim Schellnhuber et al .: World in Transition - A Social Contract for Great Transformation (Engl. World in Transition - A Social Contract for Sustainability ). WBGU, Berlin, 2nd edition 2011, ISBN 978-3-936191-38-7 .

- Hans-Joachim Schellnhuber et al .: Turn Down the Heat - Why a 4 ° C Warmer World Must be Avoided. (German: The 4 ° report. Why a world four degrees warmer must be prevented ). Report for the World Bank , prepared by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and Climate Analytics. November 2012.

- Hans-Joachim Schellnhuber et al .: World in Transition: humanity heritage Sea (Engl. World in Transition: Governing the Marine Heritage ). WBGU, Berlin, 2013, ISBN 978-3-936191-39-4 .

literature

- Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim . In: Deutscher Hochschulverband (Ed.). University Lecturer Directory 2013 / Volume 1 Universities Germany. 21st edition, De Gruyter, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-030489-3 ( online , not accessible).

- Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim . In: Kürschner's German Scholars Calendar . 26th edition, De Gruyter, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-030257-8 ( online , not accessible).

- Hübner's Who is Who : Hans Joachim Schellnhuber .

- Kaspar Mossman: Profile of Hans Joachim Schellnhuber . In: PNAS . 105, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1783-1785. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0800554105 .

- Martin Kemp : Science in culture: Inventing an icon. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber's map of global 'tipping points' in climate change. In: Nature 437, October 27, 2005, doi: 10.1038 / 4371238a .

- Henrike Rossbach: The temperature sensor . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . September 1, 2008.

- Joachim Müller-Jung: Hans Joachim Schellnhuber. The art of doubt. How climate research could become a world conscience. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , June 7, 2010, No. 128, p. 32.

- Joachim Müller-Jung: Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: "Self-immolation" . On: FAZ.net , November 27, 2015. (Review of his 2015 book Self-Burning ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Hans Joachim Schellnhuber in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by Hans Joachim Schellnhuber on ORCID

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, director (short biography, CV, publications, pictures). Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

- Prof. Dr. Dr. hc Hans Joachim Schellnhuber CBE (short biography). Scientific Advisory Board on Global Environmental Change.

- Member entry by Hans Joachim Schellnhuber at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on January 5, 2014.

- Hans Joachim (John) Schellnhuber. Santa Fe Institute, archived from the original on December 30, 2013 .

- A smart head for a cool climate: climate researcher Hans Joachim Schellnhuber staged with a thermal imaging camera. FAZ campaignwith Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, December 7, 2009.

- Billionaires' climate debt : Hans Joachim Schellnhuber in conversation with Christopher Schrader in the Energiewende magazine , March 23, 2017

Videos

- Before Cancun: A portrait of climate researcher Hans Joachim Schellnhuber. ( Memento from January 7, 2014 in the web archive archive.today ) (Video, 4:57 min.). German wave . November 22, 2010.

- World in Transition: Interview with the Chair of the WBGU, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber. Virtual Academy Sustainability at the University of Bremen, 2012(English).

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Terra quasi-incognita: beyond the 2 degree line. First keynote address, 4degrees and Beyond International Climate Conference (video, 34:21 min., English). Oxford University , April 28-30 September 2009.

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Climate Change: The Critical Decade . First keynote address (video, 1:05 hours, English) on the Four degrees or more? Conference , University of Melbourne , Australia, July 12, 2011.

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Prologue (. Video, 4:53 min) and Epilogue (Video, 7:44 min.) In the international WBGU Symposium "Towards Low-Carbon Prosperity: National Strategies and International Partnerships" (dt "Ways to. Climate Compatible Prosperity: National Strategies and International Partnerships ”). Berlin, May 9, 2012.

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: The Scope of the Challenge: Latest Scientific Insights . Lecture at the Stakeholder Conference on the European Commission Consultative Communication The 2015 International Climate Agreement: Shaping international climate policy beyond 2020 . Brussels, April 17, 2013 ( video of the entire event, 4:15 hours, English with German translation).

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Tipping Points and Extreme Weather Events . Lecture (with discussion) at the Joint Workshop “Sustainable Humanity, Sustainable Nature: Our Responsibility” , Pontifical Academy of Sciences , Vatican City , May 3, 2014 (video, 45 min).

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Expert discussion in the Environment Committee of the German Bundestag on the WBGU report on climate protection as a global citizenship movement , December 3, 2014 (video, 1:38 hours).

- But what remains? - In conversation with Hans Joachim Schellnhuber . Horizonte , Hessischer Rundfunk , March 20, 2016 (video, 30 min).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Energy and Climate Change: Internationally renowned experts are to advise Commission President Barroso . European Commission . March 6, 2007. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Bruno Kammertöns, Stephan Lebert: Hans Joachim Schellnhuber . In: The time . March 27, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hans Joachim Schellnhuber - Curriculum Vitae . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ a b “Political discussion about the solution of the climate problem decisively shaped” (German Environmental Prize 2007: individual award Prof. Dr. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber). (No longer available online.) Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt , September 26, 2007, archived from the original on January 4, 2014 ; accessed on January 4, 2014 .

- ^ A b Jan-Christoph Kitzler: Schellnhuber calls for a carbon-free world economy. (Interview). In: Deutschlandradio Kultur . March 23, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e Frank Raes: John Schellnhuber . Interview. In: Air & Climate. Conversations about Molecules and Planets, with Humans in between . Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg 2012, ISBN 978-92-79-25195-5 , pp. 55–75 , doi : 10.2788 / 31132 ( PDF [accessed February 10, 2014]).

- ↑ Andrea Huber: Portrait: A Potsdam climate researcher as an environmental advisor to the Pope . In: Berliner Morgenpost . July 19, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Kaspar Mossman: Profile of Hans Joachim Schellnhuber . In: PNAS . 105, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1783-1785. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0800554105 .

- ^ Margret Boysen: Escape from the lantern order. perlentaucher.de, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Boysen, Margret. In: Catalog of the German National Library. Retrieved April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Margret Boysen . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ Bruno Kammertöns, Stephan Lebert: "Sometimes I could scream" (interview) . In: The time . March 26, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Schellnhuber: Encyclical on the height of time . In: Vatican Radio . June 18, 2015. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- ↑ Portrait of the institute . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Schellnhuber becomes professor at the Santa Fe Institute . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. March 8, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ↑ Hans Joachim (John) Schellnhuber. Santa Fe Institute, archived from the original on December 30, 2013 ; accessed on January 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Brief CV . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: First principles band structure of crystal electrons in a homogeneous magnetic field and verification of the Peierls-Onsager hypothesis . Dissertation. University of Regensburg, 1980, DNB 810080494 .

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Gustav M. Obermair: First-principles calculation of diamagnetic band structure . In: Physical Review Letters . 45, No. 4, 1980, pp. 276-279. doi : 10.1103 / PhysRevLett.45.276 .

- ^ Stellan Ostlund, Rahul Pandit, David Rand, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Eric D. Siggia: One-Dimensional Schrödinger Equation with an Almost Periodic Potential . In: Physical Review Letters . 50, No. 23, 1983, pp. 1873-1876. doi : 10.1103 / PhysRevLett.50.1873 .

- ^ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Discourse: Earth System Analysis - The Scope of the Challenge . In: Hans-Joachim Schellnhuber, Volker Wenzel (Ed.): Earth System Analysis: Integrating Science for Sustainability . Springer-Verlag , Berlin Heidelberg 1998, ISBN 978-3-642-52356-4 , p. 3–195 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-642-52354-0_1 ( PDF [accessed on February 16, 2014]).

- ^ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: 'Earth system' analysis and the second Copernican revolution . In: Nature . 402 (Supplement), No. 6761, 1999, pp. C19-C23.

- ↑ WBGU : Welt im Wandel: Ways to Solve Global Environmental Problems . Annual report 1995. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg New York 1995, ISBN 3-540-60397-2 ( wbgu.de [PDF; accessed April 2, 2019]). World in Transition: Ways to Solve Global Environmental Problems ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2019 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Johan Rockström, Will Steffen, Kevin Noone, Åsa Persson, F. Stuart Chapin, Eric F. Lambin, Timothy M. Lenton, Marten Scheffer, Carl Folke, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber et al .: A safe operating space for humanity . In: Nature . 461, 2009, pp. 472-475. doi : 10.1038 / 461472a .

- ^ New Hot Papers: Timothy M. Lenton & Hans Joachim Schellnhuber . ScienceWatch.com. July 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ Joel B. Smith, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, M. Monirul Qader Mirza: Vulnerability to Climate Change and Reasons for Concern: A Synthesis . In: IPCC Third Assessment Report - Climate Change 2001 . Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge University Press , 2001 ( online [PDF; accessed March 14, 2018]).

- ↑ Timothy M. Lenton, Hermann Held, Elmar Kriegler, Jim W. Hall, Wolfgang Lucht, Stefan Rahmstorf, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Tipping elements in the Earth's climate system . In: PNAS . 105, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1786-1793. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0705414105 .

- ↑ Tilting elements remain a "hot" topic . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Tilting elements - Achilles' heels in the earth system . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ↑ Analysis, Integration and Modeling of the Earth System (AIMES) Project: Science Plan and Implementation Strategy. IGBP Report No.58 (PDF) International Geosphere-Biosphere Program . 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ↑ Prof. Dr. Dr. hc Hans Joachim Schellnhuber CBE . WBGU . Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Mark Townsend, Paul Harris: Now the Pentagon tells Bush: climate change will destroy us . In: The Observer . February 22, 2004. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ↑ CV of Prof. Dr. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Climate Protection Commissioner (pdf) The Federal Government . Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ President Barroso announces the creation of a science and technology advisory board . European Commission. February 27, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Schellnhuber will advise President of the EU Commission in a new position . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. February 28, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Climate researcher Schellnhuber briefs the UN Security Council . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. February 15, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ The 2015 international agreement . European Commission. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ↑ Schellnhuber speaks at a conference on the 2015 Climate Agreement . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. April 17, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ↑ Stakeholder Conference on the European Commission Consultative Communication (Agenda) (PDF) European Commission. April 17, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ↑ Berlin 2010: Climate Governance & Development (In preparation of WDR 2010) . The World Bank. September 29, 2008. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved on April 20, 2014.

- ↑ Four Degree Dossier for the World Bank: Risks of a Future Without Climate Protection . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. November 19, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Half a billion for climate innovation - EU commissioners in the Climate-KIC . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. February 23, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Member entry by Hans Joachim Schellnhuber at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Strategy Advisory Board ( en ) Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies . Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber ( English ) World Economic Forum. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ GEA Council ( English ) IIASA . Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Climate Justice Dialogue ( English ) World Resources Institute . Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Advisory groups: Advisory group for climate change . Deutsche Bank. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ German Bundestag : “Reduce carbon emissions to zero by 2070” (summary and video recording). December 3, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ↑ EU Commission appoints top advisors for decarbonization under the direction of Schellnhuber , PIK, October 21, 2016

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Wolfgang Cramer , Nebojsa Nakicenovic, Tom Wigley, Gary Yohe: Avoiding Dangerous Climate Change . Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-86471-8 .

- ↑ Malte Meinshausen, Nicolai Meinshausen, William Hare, Sarah CB Raper, Katja Frieler, Reto Knutti , David J. Frame, Myles R. Allen: Greenhouse gas emission targets for limiting global warming to 2 ° C . In: Nature . 458, No. 6, 2009, pp. 1158-1163. doi : 10.1038 / nature08017 .

- ↑ New approach to overcoming the climate policy deadlock: Kassensturz before Copenhagen - The budget approach . WBGU. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Mark Landler: A Climate Meeting With Nobel Laureates. In: The New York Times . October 11, 2007. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Potsdam Memorandum 2007 . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ↑ St. James's Palace Nobel Laureate Symposium . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ↑ World leaders urged to "move beyond aspirational statements" and seize "historic opportunity" at Rio + 20 to put the planet on a sustainable path (PDF) United Nations. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ WBGU Symposium 2012: "Towards Low-Carbon Prosperity: National Strategies and International Partnerships" (Paths to Climate Compatible Prosperity: National Strategies and International Partnerships) . WBGU. May 9, 2012. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ Nobel Laureates Symposium in Hong Kong 2015 . nobel-cause.de. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ↑ Earth League: Leading research institutions establish a worldwide network . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. February 14, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ↑ Alex Kirby: Case for climate change is overwhelming, say scientists . In: The Guardian . September 16, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ↑ Conference: IMPACTS WORLD 2013 . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Axel Flemming: "Impact World 2013" - Conference in Potsdam ( Memento from November 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: B5 aktuell . May 31, 2013. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ↑ The elephant in the room: Recognizing the future climate impact . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. December 16, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ↑ Quirin Schiermeier: Water risk as world warms. First comprehensive global-impact project shows that water scarcity is a major worry . In: Nature . 505, 2013, pp. 10-11. doi : 10.1038 / 505010a .

- ^ Association of German Scientists (Ed.): Potsdam Memorandum 2005 . Ökom-Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-86581-012-8 (German, English, vdw-ev.de ).

- ^ Papal encyclical: PIK researchers in the Vatican and in Berlin . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. June 12, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ Avviso di Conferenza Stampa, June 10, 2015 . press.vatican.va. June 10, 2015. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- ^ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Common Ground: The Papal Encyclical, Science and the Protection of Planet Earth . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved on July 20, 2015. (Handout on Schellnhuber's presentation when the encyclical was published)

- ↑ Joachim Müller-Jung: I don't believe in the master plan for the world. In: FAZ . June 19, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ↑ a b Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Geoengineering. The good, the MAD, and the sensitive . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . tape 108 , no. 51 , December 20, 2011, p. 20277-20278 , doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1115966108 .

- ↑ Olaf Stampf , Gerald Traufetter: Kick in the butt. (Interview). In: Der Spiegel . August 16, 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ↑ Joachim Müller-Jung: The climate researcher Schellnhuber in conversation: The world map of climate protection has changed. (Interview). In: FAZ . December 11, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ A b c Dagmar Dehmer, Lutz Haverkamp: Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: "Overcoming the dictatorship of the present." (Interview). In: Der Tagesspiegel . March 26, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ a b Katrin Elger, Christian Schwägerl: Dictatorship of Now. In: Der Spiegel . March 21, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Climate, Crises and Conflicts (PDF) Foreign Office . June 13, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ↑ Climate change is like an asteroid impact . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ Friedbert Meurer : How do we divide this cake? (Interview). In: DRadio .de . December 7, 2009. Retrieved November 2, 2013

- ↑ Climate protection within the framework of the UN not possible . Chat with Hans Joachim Schellnhuber. tagesschau.de . December 21, 2009. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Forward to nature. In: FAZ . May 3, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ↑ Fritz Vorholz, Frank Drieschner: "Surrender is cowardly" . In: The time . November 22, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ Gero Rueter: Schellnhuber: “Climate policy needs pressure from below” (interview). In: Deutsche Welle . December 10, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Claus Leggewie, Renate Schubert: Two degrees and no more . In: The time . January 16, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Three convenient untruths. The attacks of the "climate skeptics" require interdisciplinary solidarity (PDF). Leibniz Journal, 1/2013, p. 9. Retrieved on March 10, 2013.

- ^ Dirk Asendorpf: The struggle for air sovereignty (interview). In: The time . October 11, 2007. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Thomas Bärnthaler, Jasper Ruppert: “The truth doesn't do us good” . In: SZ-Magazin . January 24, 2016 ( sueddeutsche.de [accessed December 29, 2019]).

- ↑ Thomas Daniel, Dominik Rzepka: Climate researchers: Shaking your head about AfD . In: heute.de . April 3, 2016. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved on April 20, 2016.

- ↑ See. Show climate pass when entering , by Bernd Matthies, Tagesspiegel, Nov. 27, 2017

- ↑ Cicero - The 500 most important intellectuals, ranks 201–220 ( Memento from February 23, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Joachim Wille: Man with a Mission . In: Frankfurter Rundschau . December 10, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ↑ Sebastian Matthes, Dieter Dürand: "Mixture of stupidity and arrogance" (Interview with Hans von Storch ) In: Wirtschaftswoche . February 20, 2010. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ↑ FDP wants to get rid of climate researcher Schellnhuber as a consultant. In: Zeit Online , May 3, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ↑ Axel Bojanowski : Political Advisor: Thick air around Merkel's new environmental whisperer. In: Spiegel Online , May 2, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ↑ Michael Bauchmüller: FDP blocked climate experts Schellnhuber. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , May 2, 2013. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- ↑ Karl Doemens: Altmaier and Rösler argue about experts. In: Frankfurter Rundschau , May 2, 2013. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- ↑ Personnel dispute : Rösler takes Schellnhuber to the advisory board. In: FAZ , May 5, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ Members of the Scientific Advisory Board on Global Change Appointed . BMU press release. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ↑ Brendan Nicholson, Lauren Wilson: Climate anger dangerous, says German physicist . In: The Australian . July 16, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ↑ Henrike Rossbach: The temperature sensor . In: FAZ . September 1, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ↑ Prof. Dr. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber in conversation with Thomas Prinzler (interview, audio, 14:53 min, transcript) In: RBB Inforadio . Archived from the original on February 18, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ A b c Cordula Meyer: Lobbyists: Science as enemy . In: Spiegel Online . October 4, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ↑ a b EIKE visit to PIK - collection of factual arguments (PDF) Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ↑ New UEA professor awarded top science honor . University of East Anglia. November 4, 2002. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schellnhuber honored twice internationally . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. May 10, 2005. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ^ Member Directory: Hans Joachim Schellnhuber . National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Schellnhuber awarded the Brandenburg Order of Merit . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. June 13, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ↑ Professor Dr. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber CBE - Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) . Federal German Working Group for Environmental Management e. V .. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- ↑ Climate researcher Schellnhuber is a science ambassador. ZukunftsAgentur Brandenburg, August 4, 2009, accessed on April 12, 2019 .

- ^ Federal Cross of Merit for climate researcher Hans Joachim Schellnhuber and the bird protection couple Litzbarski . State Chancellery of the State of Brandenburg . December 4, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ The Volvo Environment Foundation takes great pleasure in awarding its 2011 environment prize to Professor Hans Joachim (John) Schellnhuber ( en ) Volvo Environment Prize. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Schellnhuber receives high-ranking honors. (PDF) WBGU, September 9, 2011, archived from the original on May 21, 2012 ; Retrieved January 5, 2014 .

- ↑ Honor for climate expert Hans Joachim Schellnhuber . Technical University Berlin. June 21, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Member entry by Prof. Dr. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber (with picture and CV) at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on July 20, 2016.

- ↑ see page of the institute with the external scientific members at http://www.mpimet.mpg.de/institut/organisation/ausw-lösungenemeriti.html

- ↑ Carola Brunner: Role models not only in terms of culture . In: Passauer Neue Presse . October 24, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ↑ Elke Fischer: You carry Ortenburg in your heart and out into the world . In: Passauer Neue Presse . October 26, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ Nomina di Membro Ordinario della Pontificia Accademia delle Scienze. In: Daily Bulletin. Holy See Press Office , June 17, 2015, accessed June 17, 2015 (Italian).

- ↑ Schellnhuber appointed to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences . Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. June 26, 2015. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- ^ Blue Planet Prize. The Laureates . Asahi Glass Foundation website. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ↑ Most important environmental award for climate researchers from Potsdam . In: Märkische Allgemeine , June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ↑ Generations Foundation - About. Retrieved June 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Who we are. Accessed June 14, 2020 (German).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schellnhuber, John (nickname) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German climate researcher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 7, 1950 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ortenburg , Vilshofen district , Bavaria |