History of Nordhausen

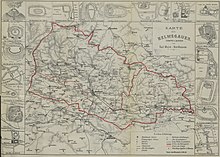

The history of Nordhausen spans more than 1000 years since the city of Nordhausen was founded and can also be traced back to individual prehistoric settlement areas in the southern Harz region. As the seat of the abbess of the Nordhäuser Damenstift and especially as a free imperial city, Nordhausen held a special status from the 13th to the 19th century. From 1937 to 1945, the Mittelwerk Dora armaments center was located near Nordhausen and, from August 1943, the Mittelbau concentration camp , in which 60,000 prisoners produced the V2 weapon underground . Beginning of April 1945 destroyed two air raids of the Royal Air Force three-quarters of the metropolitan area.

name of the city

Early documented name forms are Nordhusa (876), Nordhuse (929), Northusun (965, 1075, 1105), Northuson (993, 1042, 1105), Nordhusen (from the 12th century) and Northusia (1200, Latinized). Between the 12th and 15th centuries, the Northusen spelling predominated in chronicles and statutes , from 1480 the sounding Northausen and later Nordhausen with early New High German diphthongization is attested.

According to Germanistic name research, there is a formation from “ Nord ” and “ -hausen ” (originally a dative plural, ie “at the houses”); the meaning of the place name is therefore "in the northward settlement". The name-related counterpart is the town of Sundhausen , which was founded around the same time in the immediate vicinity of Nordhausen and whose name means "at the settlement located southwards" ( sunt is Middle High German for south ).

The thesis that the name North can be traced back to the Germanic deity Nerthus is outside the scientific discussion. According to this, the place name refers to a meeting place above the Zorge valley in the area of today's Petersberg, where the Germanic peoples a . a. gathered to the thing and also cultivated worship and customs.

The inhabitants of the city are correctly called "Nordhäuser" (in the dialect "Nordhisser").

Because of its centuries-old tradition of making brandy, Nordhausen also bears the local names “Branntwienpisser” and “Schnapshausen”. Another nickname is "Priemköppe" because of the former chewing tobacco production.

Prehistoric and early historical settlement

Early settlements in the region were known as early as the 19th century through "excavations", albeit with unsuitable means and with inadequate documentation, such as at the burial mound necropolis of Auleben (Solberg). In Windeshausen southeast of Nordhausen is one of the few grave sites in Thuringia found from the late Neolithic period, probably the Beaker culture . There was a three-quarter circle ditch about 12 m in diameter. About 300 m away there is a Late Bronze Age settlement, the grave there possibly represents the founding burial of this settlement. The warrior grave with numerous additions shows influences from the Middle Lüneburg Bronze Age and can be assigned to the early (West Central German) Late Bronze Age. Other end-Neolithic and Bronze Age graves are known in the area, which prove that the custom of digging graves in the eastern part of circular trenches was widespread in the late Middle and early Late Bronze Ages. The Early Bronze Age site of Nohra has been known for a long time .

The Nordhausen area was subject to both Celtic and Germanic influences, with the archaeologically recognizable elements being mixed and locally transformed. Accordingly, it is a mixed zone with numerous (Celtic) Latène culture elements , such as turntable ceramics or glass arm rings. At the same time, numerous elements of the Polish Przeworsk culture were found in the Nordhausen district that do not occur further south, plus a total of seven settlements of this culture in the Nordhausen area. These may go back to immigrants from Silesia who came to the southern Harz as specialists. A hierarchization can be demonstrated in the settlements, namely into the three types of hilltop castle , which are perceived as central locations , i.e. as economic, social and cultic focal points, then larger settlements, which functioned as exchange locations and specialized production, and finally smaller, open ones Settlements. After the 1st century this settlement structure disappeared, probably due to migration processes.

The area around Nordhausen belonged to the short-lived Thuringian Empire in the late 5th century and became Franconian through conquest around 531 . Between 650 and 700, Wendish-Sorbian groups populate the Bielen district. Slavic places are also proven. According to the former Nordhausen city archivist and museum director Robert Hermann Walther Müller, the settlement of the West Slavic groups, then known as Surbi , began in 640 as a result of a peace and friendship treaty between the Slav King Samo and the Thuringian Duke Radulf . First, the areas west of the Saale were settled by Sorbian colonists. Müller relies in particular on the research by Christoph Albrecht on The Slavs in Thuringia . A current analysis of the Hersfeld tithe directory by Christian Zschieschang shows a significant Sorbian settlement in Friesenfeld and Hassegau . A comparable current study on the Sorbian settlement west of Kieselhausen and Sangerhausen is not currently available, although Robert Hermann Walther Müller warned it at the time:

- The theory of the establishment of Slavic dwellings in Thuringia by servants, prisoners of war or slaves, which is repeatedly rewritten without criticism in the relevant literature, can and must be overcome if one does not want to do violence to the facts. Such a revision will require a lot of new work, but it will also yield a wealth of new knowledge.

According to Robert Hermann Walther Müller, Bielen is clearly of Slavic origin in addition to Windisehen spreads. In accordance with the state of research at the time, he sees the villages of Sittendorf , Rosperwenda , Windehausen and Steinbrücken as Slavic places , the latter having meanwhile also been incorporated into Nordhausen. In addition, there are the desert areas of Alt-Wenden, Nausitz, Lindeschu, Tütchewenden and Ascherwenden. He mentions Nenzelsrode and Petersdorf as other Slavic places , whereby Petersdorf is now part of the city of Nordhausen. In Berga already turned Rudolf Virchow laid the remains of a fishing village in the 1872nd The villages of Görsbach , Sülzhayn , Branderode , Buchholz and Leimbach can be recognized by Wendish impact , whereby the last two have meanwhile also been incorporated into Nordhausen. In Branderode there is even evidence of a windy door in the church, as well as in Kleinfurra and Trebra . Field names of Sorbian origin can be found in Kraja , Thalwend , Worbis , "Wyndischen Luttera", between Petersdorf and Steigerthal and near Stempeda , the latter two now also belonging to Nordhausen. In the city of Nordhausen itself, he traces the Grimmei road and the Grimm mill (later the Kaisermühle) to Sorbian origins. Also in the Zorgedorf Krimderode , today also in Nordhausen, there was a Grimme brook, which has now dried up, with the same Sorbian name: 'on the sand; on the gravel '. Robert Hermann Walther Müller even traces the name for the Zorge and the Mühlgraben back to Sorbian. For him, the Nordhausen linden legend has its origins in the Sorbian colonization, as the linden tree is the symbolic tree of this people.

middle Ages

It is believed that a Carolingian royal palace was built on the " Frauenberg " at the end of the 8th century . The old town later developed north of it. Nordhusa is already mentioned in a diploma from Ludwig the German dated May 18, 876 . Heinrich I built the first fortified complex between 908 and 912. According to a historical proposal by Gerd Althoff , the son of Heinrich I and Mathilde, Heinrich , was born here around 920 . On September 16, 929, Heinrichs I gave Nordhuse to his wife Mathilde in a deed of gift . On June 25, 934, Heinrich I issued a certificate during a stay in Nordhausen. Mathilde founded a women's monastery in 961, in which she institutionalized a number of other sacred institutions such as the canons 'convent in Quedlinburg , in addition to the castle built by Heinrich I, which was converted into an Augustinian canons' monastery in 1220. In the vicinity of these institutions, the castle complex and the monastery, craftsmen and traders subsequently settled around the Blasius Church. In the week after Whitsun 993 Otto III kept himself . in Nordhausen and issued two certificates there. When the Frauenstift was founded by Otto III in 1000. received a Romanesque splendor cross (which has been kept in Duderstadt since 1675), the Cathedral of the Holy Cross developed into the spiritual center of the monastery. The second version of Queen Mathilde's biography was probably written in the women's monastery in Nordhausen, whose first abbess Richburga was installed in the winter of 967 . Mathilde tried again and again to the place. After Mathilde's death in 968, their property fell under the control of the emperor again. In the marriage certificate of Empress Theophanu , Otto I and Otto II handed over Nordhausen in 972 as one of several assignments of the dowry to the wife Theophanu . A merchant settlement around the Nikolaikirche from the early 12th century developed into the actual city. This was extended by a Flemish cloth weaver settlement built on the other side of the city wall at the end of the 12th century to include the Petrikirche, in the 13th century by a new town that remained outside the wall around the Jakobikirche.

Nordhausen was in the medieval county of Helmegau , which was mentioned in a document of Charlemagne in 802 .

From 1144 to 1225, German kings stayed in Nordhausen several times. In 1158, Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa donated all imperial possessions in Nordhausen to the cathedral monastery , which gained considerable influence as a result. In 1180 the city was destroyed by the troops of Henry the Lion because of a rift between Henry and the Emperor. During the subsequent reconstruction, the city fortifications were reinforced around 1206 in order to be able to stand up to the counts and knights of the surrounding area. They felt that their rights were restricted by the city and feuded them several times. On July 22nd, 1212, Emperor Otto IV , son of Henry the Lion, married Beatrix of Swabia from the Staufer family in Nordhausen , which brought about a reconciliation between the two rulers. As early as 1234, a major fire destroyed large parts of the city.

On July 27, 1220 Nordhausen was the king and later Emperor Frederick II. To free imperial city raised what it to the media coverage was the 1,802th The city received its first seal in 1225, a council was formed for the first time around 1260 and the first town hall was built at the current location around 1280. At the end of the 13th century, the council prevailed against the Vogt and Schultheiss, who had already been occupied around 1220: in 1277 there was a revolt of the craftsmen and petty bourgeoisie against the imperial knights . The Reichsvogt was expelled and the Reichsburg destroyed. In 1290 the Roman-German King Rudolf von Habsburg confirmed the imperial freedom of Nordhausen and placed the city under his protection in order to be reconciled with the citizens. Due to its favorable economic and geographical location, Nordhausen probably enjoyed considerable prosperity in the 13th century.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Counts of Schwarzburg , von Stolberg , von Hohnstein and the knights of Klettenberg Castle attacked Nordhausen several times. When knights of the Counts of Hohnstein zu Sondershausen, the Counts of Stolberg and Klettenberg Castle tried - ultimately unsuccessfully - to penetrate the city through the Barfüßertor and the Altentor in 1329, the mayor of Nordhausen, Helwig von Harzungen and three citizens, fell Defending goals. In another uprising on February 14, 1375, the council was overthrown and its members banished. The city received a new constitution and the artisans took power. During this time, some orders settled in Nordhausen, for example Augustinians , Dominicans and Franciscans . The neighboring monasteries in Walkenried and Ilfeld also founded monastery courtyards in the city. As early as the 14th century, the imperial city of Nordhausen required its citizens' sons who wanted to join one of these orders to renounce their inheritance in writing in order to prevent the church's tax-free property (“ dead hand ”) from increasing.

The highest warlord of the free imperial city of Nordhausen was originally the imperial bailiff, later the council, who appointed two warlords (so-called arrow masters) from his ranks. The city army consisted of the well-fortified citizenry (statutes 1350) and recruited mercenaries (city unification 1308). Once upon a time the arrow masters were also city governors. From 1350 chivalric captains were taken into city service. The citizenship was divided into rotten based on the parish and parish division (arrow master list 1443-1545). There were 21 squads, each with two squad masters, the strength of the squads fluctuating (1491–1499) from 17 to 48 men. In 1499 there were 577 citizens capable of arms. Since the beginning of the 17th century there were city soldiers under one captain, who in 1794 numbered around 70 men. The vigilante group consists of two companies.

Proof that Nordhausen was active as part of the Hanseatic League dates back to 1430 . In 1500 Nordhausen became part of the Lower Saxony Empire . At the end of the Middle Ages, Electoral Saxony was the protective power over the city. Probably after 1277 a wall was built that covered an area of 35 hectares. This walling was renewed between 1350 and 1450. In 1365 the settlements were also legally united. Around 1500 the city had about 5000 inhabitants.

Early modern age

In 1507 the production of brandy in the city was first mentioned in a document. At peak times there were 100 distilleries in town. Chewing tobacco was also produced in Nordhausen. Vitriol oil was also produced in the 16th century ; after the first production site in Nordhausen, the product was called "Nordhäuser Vitriol".

The Reformation prevailed in Nordhausen in 1523/24 . The driving force here was the mayor Michael Meyenburg . That year Thomas Müntzer was in the city. Nordhausen was the first city to officially join the Reformation by council resolution in 1524, after a follower of Martin Luther had already given one of the first Protestant sermons in Germany in 1522 in the St. Petri Church . In the following period, all parish and monastery churches in the city became Lutheran and the church property was secularized , with the only exception of the Holy Cross Monastery , which continued as a Catholic body until 1810.

Although two city fires (1540 and 1612), the plague epidemics and the Thirty Years War hampered the development of the city, it continued to grow. The plague raged in Nordhausen repeatedly in the years 1393, 1398, 1438, 1463, 1500, 1550, 1565 and 1682. In 1550 a first register of the dead was drawn up, which lists over 2,500 victims. In 1626 there were over 3,000 deaths and in 1682 3,509 victims are recorded.

Nordhausen was persecuted by witches from 1559 to 1644 . 27 people were involved in witch trials , eight were executed, five sentenced to expulsion from the country and four died in torture or in prison.

There were further city fires in 1710 - the burnt down rectory was replaced by today's orphanage by 1717 - and in 1712, so that little of the medieval structure remained. Of the twelve churches in the Middle Ages, only the cathedral, the Blasiikirche, the Frauenbergkirche and the Altendorf church remained. During the Thirty Years' War the city was temporarily occupied by the Swedes, high contributions were extorted and all of the city's cannons and some of the church bells were stolen. As a result, the city secretly supported the Harzschützen with money, room and board.

Brandenburg occupied the city from 1703 to 1714 .

From the 19th century to the Weimar Republic

As a result of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss 1802, Prussia also received Thuringian areas as compensation for territories on the left bank of the Rhine that were lost to France. The city of Nordhausen was occupied by Prussian troops on August 2, 1802 and incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia , which lost its imperial freedom. On February 7, 1803, the city lost the right to mint . From 1807 to 1813 Nordhausen belonged to the Kingdom of Westphalia , which Napoleon had built for his brother Jérôme Bonaparte , and then again to Prussia, which was confirmed by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 . Nordhausen remained a Prussian city until 1945.

In the third book (second chapter) of his novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame from 1831, Victor Hugo Nordhausen praises Nuremberg , Vitré in France and Vitoria in Spain as a model Gothic city that, in contrast to Paris in the early 19th century, was able to retain its originality . Because of its GA Hanewacker chewing tobacco factory (founded in 1817), Nordhausen was the center of chewing tobacco production in Germany.

Nordhausen was briefly a garrison town under Prussian rule: 1832–1848 IV. Jägerabteilung, 1868–1870 II. Battalion 67th Infantry Regiment.

In the period up to 1866, a smuggling activity that was hitherto unknown in Thuringia flourished in Nordhausen . Above all, coffee, tea and tobacco were smuggled because these luxury foods were taxed much less in the neighboring Kingdom of Hanover than in Prussia. Even the strictest threats of punishment could not change the situation. The border ran along today's street at the enclosure. At times smoking of tobacco and the consumption of brandy in public were banned.

In 1867 Eduard Baltzer founded the German vegetarian movement in Nordhausen. The first congress of German vegetarians in the city follows in 1869.

In the middle of the 19th century, industrialization began in Nordhausen and initially extended to chewing tobacco, grain brandy (Nordhäuser), wallpaper manufacture, weaving, ice machines and coffee substitutes. The economic basis broadened around 1900 mainly in the machine, engine and shaft construction industry.

In 1866 Nordhausen was connected to the railroad from Halle (Saale) , the continuation to Heiligenstadt and Kassel was opened a year later. Rail routes to Northeim and Erfurt followed in the next few years . The tram has been in Nordhausen since August 25, 1900 . The commissioning of a modern water pipeline (1874), a hospital (1888), the Harzquerbahn (1897/99) and the construction of the Nordhäuser Dam mark further municipal progress up to the First World War.

From 1815 to 1945 Nordhausen belonged to the Prussian province of Saxony , in which it had been a separate urban district in the administrative district of Erfurt since 1882. The district office of the Grafschaft Hohenstein district was also located here .

At the beginning of the World War 3,000 conscripts were drafted, in 1916 the number rose to over 5,000 and in May 1918 to around 6,500. The war memorial erected in 1925 commemorates 1,048 fallen north houses. Although economic development was interrupted by the war, it continued to develop positively, a. expressed in lively construction activity; the new city theater and the stadium with outdoor pool were built.

From May 27 to 29, 1927, the city celebrated its millennium, on the occasion of which special postmarks, postage stamps, festival postcards and medals as well as a two-volume and richly illustrated history of the city were issued. The Reich Ministry of Finance also approved the issuance of a 3-mark commemorative coin with a circulation of 100,000 pieces.

National Socialism and World War II

In 1933 the NSDAP took control of the city. In the Reichstag election on March 5, 1933 , she received 46.7 percent of the vote in Nordhausen. By the summer of 1933, at least 20 members of the KPD and SPD were taken into protective custody, but several were released after a brief detention. Some of the arrested were interned in the Siechenhof , others in the court prison, the majority, however, in the police prison in Erfurt and from there to concentration camps. In March 1933 , the NSDAP and DNVP held almost 60 percent of the seats in the city council . It was followed by the DC circuit of the city administration. Mayor Curt Baller , who is considered to be left-wing liberal, tried in vain to stay in office. On July 1, 1933, the lawyer Heinz Sting was appointed Lord Mayor by the district government. In September 1933 the social democrat and editor of the “ People's newspaper ” Johannes Kleinspehn was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison.

In June 1933 the local group of German Christians was founded under the pastor of the St. Blasii community .

After the death of District Administrator Gerhard Stumme , a violent power struggle broke out in the spring of 1934 between Sting and the NSDAP district leader Heinrich Keizer, which also caused a sensation in the staff of the Führer’s deputy . On October 19, 1934, Heinz Sting was given leave of absence as Lord Mayor, and Keizer was transferred to Saalfeld-Rudolstadt in 1935.

After the introduction of compulsory military service, the Boelcke barracks with accommodation buildings and vehicle hangars were built for the air force in the south-east of Nordhausen in 1935/36 . The air base served primarily as a training and test site, and an aircraft yard was also in operation here at times.

During the November pogroms in 1938 , apartments and shops were destroyed and the synagogue on the horse market was set on fire. The 400 or so Jews from Nordhausen emigrated or were later deported to the concentration camps . On April 14, 1942, the evacuation of the Jews who remained in Nordhausen began.

From December 1939 to June 1940 around 9,000 Saarlanders were housed in private households and collective accommodation in Nordhausen. The first Polish prisoners of war arrived in autumn 1939. Around 450 prisoners of war were registered in early 1942 and 700 in March 1945.

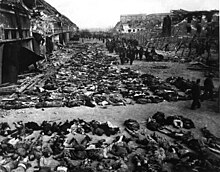

From 1937 to 1945 there was the Mittelwerk Dora armaments center near Nordhausen and from August 1943 the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp with 60,000 prisoners (20,000 of whom were killed by 1945), in which, after the attack on Peenemünde, the production of so-called retribution weapons , above all, was located the new A4 (rocket) , but also the older Fieseler Fi 103 , took place. In addition, 10,000 German prisoners and foreign forced laborers who were housed in 38 camps were forced to work in various companies. The largest forced labor camp with max. 6,000 inmates, some of whom had to work for the Junkers aircraft and engine works, were in the Boelcke barracks. From the end of January 1945 this became a “sick and death camp of the Mittelbau complex” and was located in the south-east of Nordhausen. It was badly hit in the British bombing raids on April 3rd and 4th. The US Army forced the residents of Nordhausen to rescue, transport and bury the dead. The 1,300 victims were buried in the cemetery of honor on Stresemann-Ring. A memorial erected in 1999 commemorates them. Next to it is a cemetery of honor for 215 Soviet victims, which was laid out in 1946.

On the night of August 25 to August 26, 1940, Nordhausen was first targeted by an air raid when two bombers attacked the airfield. Smaller attacks were flown on April 12, 1944 and July 4, 1944. On February 22, 1945, at around 12:30 p.m. US bombers attacked the marshalling yard, but hit the lower town, some facilities in the industrial area and the former Luftwaffe telecommunications school in the Boelcke barracks. A total of 296 multi-purpose bombs were dropped, killing 40 people. On February 26, the Südharzer Kurier published an obituary notice for the “fallen soldiers of the terrorist attack” with the announcement that the city would be buried with a memorial service.

On July 1, 1944, the Reich Governor in Thuringia was entrusted with the exercise of the duties and powers of the High President in the state administration of the Erfurt administrative district . On October 29, 1944, the age groups 1884–1928 were recorded for the Volkssturm and divided into 29 battalions. The first 200 Volkssturm men were called to the front on February 21, 1945.

At the beginning of March 1945, 42,207 residents were registered in Nordhausen. In addition there were 23,467 “non-residents” (659 prisoners of war, 503 wounded soldiers in 5 hospitals, 420 members of the navy , 6082 foreign workers in mass quarters).

A week before the US armed forces marched in, the city was 74% destroyed by two British air strikes on Nordhausen on April 3 and 4, 1945 , killing around 8,800 people and leaving over 20,000 homeless. The bombing was ordered by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force on April 2, 1945 . They called for an attack in support of the 1st US Army with priority at the earliest opportunity. The purpose of the RAF attacks in April 1945 was to clear the way for an unhindered advance from the resistance expected in the southern Harz region. The first major attack on April 3rd at 4 p.m. was carried out by 247 Lancaster bombers and 8 mosquitos of the 1st and 8th bomber groups , which dropped 1,170 tons of high explosive bombs in 20 minutes, especially on the south-eastern quadrant of the city. Around 1,200 prisoners also died. The second major attack on April 4 at 9 a.m. with 243 Lancaster bombers of No. 5 bomber group and 1,220 tons of bombs are considered to be the heaviest attack and aimed as area bombing , also with a firestorm triggered by phosphorus bombs on the inner city area. Mainly residential areas (10,000 apartments), the hospital and numerous cultural monuments of outstanding importance were destroyed. The city hospital, which had already been evacuated on the evening of April 3rd, moved to the tunnel complex in Kohnstein on April 8th . There were from 3./4. April also many thousands of northern houses fled. With the exception of the earlier Boelcke barracks, no targets that could be identified as military or important to the war effort were hit. The train station, the airfield, the railway tracks, the industrial plants and the Dora concentration camp, where the A4 (rocket) was also produced, remained undamaged. The St. Blasii Church, the Cathedral and the Frauenberg Church were badly damaged. The Frauenberg monastery, the Neustadt parish church of St. Jakobi, the market church of St. Nikolai, and the St. Petri church were destroyed (tower partially preserved). The remains of these buildings were demolished after the war. The city wall including the partly used towers and Wiechhäuser was badly hit, the town hall was destroyed except for the surrounding walls. Large numbers of the bourgeois half-timbered buildings from the Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo and early Classicism styles that are characteristic of Nordhausen were destroyed. In the city center, numerous fires raged for days, bombs with time fuses exploded, and the urban area was under fire from low-flying aircraft. Initially only a few residents tried to bury the dead or to salvage their belongings.

The losses of the permanent population were 6,000 people, those of the non-permanent population 1,500, plus 1,300 prisoners from the Boelcke barracks, which together results in an estimated number of 8,800 victims. This relates only to the closer urban area of Nordhausen, without the losses in the later incorporated districts. There are also higher estimates of over 10,000 dead, for example by the Antifa Committee in June 1945. Of the 8,800 deaths, about 4,500 were women and children.

At the beginning of April 1945 the Volkssturm made preparations to defend the city. So ditches were dug in the Gumpe, on the Holungsbügel, on the promenade, in the enclosure and at the city entrances. A majority of the officers and airmen set off in the direction of the “Harz Fortress” in the following days . Shortly after the police and party officials left the city, the Volkssturm, which had been decimated by the air raids, dissolved.

On the morning of April 11, 1945, the 104th US Infantry Division ( 1st US Army ) advancing via Werther occupied Nordhausen without a fight with tank support. Around 11 a.m., the soldiers encountered the survivors of the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp in the badly destroyed Boelcke barracks . Around 1,200 prisoners died in the bombing of the city in the accommodation blocks. The concentration camp to the northwest was reached on the same day. Mittelwerk Dora itself had never been bombed and fell into the hands of the US troops undamaged with all secret weapons and documents. In the vicinity of the Kohnstein and in the village of Crimderode , German rearguards blew up bridges over the Zorge. Around 200 German soldiers and suspicious people in the city were captured and brought together in the Rothleimmühle assembly camp . The city was officially handed over in the afternoon. Military governor became Captain William A. McElroy.

On April 12, the military administration released Nordhausen for eight days to be looted by former prisoners and foreign forced laborers . Werewolf activities became known in late April and some weapons and ammunition supplies were confiscated. On May 8, 1945, the mayor appointed by the Americans, the social democratic labor leader Otto Flagmeyer, had to threaten all looters with the death penalty. On May 13th, a funeral service for the victims from the Boelcke barracks took place in the Ehrenfriedhof. All adult northern houses had to take part in it, after which they received personal documents and ration cards. Since the Nordhausen hospitals had all been destroyed, an auxiliary hospital was set up in Ilfeld from April 1945 . In Nordhausen, too, typhus ruled from spring 1945 , which exacerbated the desolate situation in the city.

Soviet occupation zone and GDR period

On June 16, 1945, the former Prussian administrative district of Erfurt and thus also Nordhausen was incorporated into the state of Thuringia . The Red Army replaced the US Army as the occupying power on July 2, 1945.

“April, May, June: plundering hordes, 9 p.m. curfew, all houses barred doors and windows. Everyone wonders if they will be the victim today. Turbulent scenes in front of the shops, standing in line for hours and at the end of the day going home empty because the cheeky guys simply picked up 3-4 loaves of bread by force. "

In July 1945 there were over 7,200 people in the city and district who had their residence in the three newly formed Western Allied occupation zones . They sought protection from the air raids in the region during the war. In December 1945 their number was 1,411. In the course of the expulsion , the number of refugees in June 1945 was 10,463, in December 1945 a total of 18,054. They came from Berlin and the Mark Brandenburg , from Pomerania , East and West Prussia , very many from the Sudetenland and the vast majority from Silesia ; they were initially housed in larger camps.

The war-torn inner city of Nordhausen was rebuilt in the 1950s and 1960s after clearing it from 1945. The historical settlement structure was completely disregarded. Instead, wide main roads such as Rautenstrasse and Töpferstrasse were created, in line with contemporary tastes. Only in the north-west of the old town in the vicinity of the cathedral was the old town structure preserved, which survived both the air raids and the GDR era. The Bismarck monument in the promenade and the military freedom monument on the Theaterplatz were demolished in 1945.

The Nordhausen Trial was conducted as a United States Army war crimes trial in 1947. After the dissolution of the states in the GDR, which was founded in 1949, the city belonged to the district of Erfurt from 1952 until Thuringia was reconstituted as a federal state in 1990 . There it was the district town of the Nordhausen district , which was converted into today's Nordhausen district in 1994 .

Nordhausen was a center of unrest in the Erfurt district on and around June 17, 1953 . As early as the first days of June 1953 there were strikes against the decreed increases in labor standards. On June 17th there was a powerful strike in the VEB IFA tractor factory . However, the workers were unable to go to demonstrations in the city because the plant had been surrounded by the People's Police and the People's Barracked Police . There was also a strike in the shaft construction and drilling operations . Soon the slogans of the strikers became political: Away with the government, free elections and lifting of the state of emergency imposed by the Soviet Army . The strike leader was the union official Otto Reckstat (1898-1983), who worked as an auxiliary fitter at Nordhäuser VEB ABUS-Maschinenbau. Strikes and riots continued on June 18, when people's police units occupied the factories under the protection of the Soviet Army.

The organizers of the stage location of the GDR cycling tour made Nordhausen known far beyond the district borders. On August 22, 1961, the city was the destination of the 5th stage (Jena - Nordhausen; 136 km; winner: Gustav-Adolf Schur [SC Wissens. DHfK Leipzig I]) and the next day the start of the 1st half stage (Nordhausen - Kyffhäuser; individual time trial ; 24 km; winner: Dieter Wiedemann [SC Wismut K.-M.-Stadt I]) of the 6th stage (Nordhausen - Dessau; 164 km; winner: Dieter Wiedemann [SC Wismut K.-M.-Stadt I]) the 12th GDR tour ; on August 14, 1962 finish of the 1st stage (Magdeburg - Nordhausen; 147 km; winner: Klaus Ampler [SC DHfK Leipzig I]) and on the following day start of the 2nd stage (Nordhausen - Bad Langensalza; 100 km; winner: Manfred Weißleder [SC Wismut Karl-Marx-Stadt I]) the 13th GDR tour ; on September 5, 1974 finish of the 6th stage (Dessau - Nordhausen; 143 km; winner: Hans-Joachim Hartnick [GDR]) and on the following day the start and finish of the 7th stage ("Across the Harz"; 134 km; winner : Wolfgang Gansert [SC Turbine Erfurt]) of the 22nd GDR tour . On Saturday, September 7th, 1974, a report about the 7th and last stage of the 22nd GDR tour was broadcast on the first program of GDR television at 16:25 in the program “ Sport aktuell ”. Reports included the start of the race in Nordhausen, the stadium entrance in Nordhausen, the sprint on the cinder track at the Hohekreuzsportplatz, the award ceremony and the lap of honor. Finally, there was an interview with the GDR national cycling coach Wolfram Lindner . On August 20, 1976, Nordhausen was the destination of the 7th stage (Jena - Nordhausen; 165 km; winner: Holger Kickeritz [SC Dynamo Berlin II]) and the following day the start and finish of the 8th stage ("Across the Harz"; 119 km; winner: Bernd Drogan [GDR I]) of the 24th GDR tour .

On May 29, 1980, at a meeting of representatives of the LSK / LV command and the GDR border troops, it was decided to relocate Helicopter Squadron 16 from Salzwedel to the new location in Nordhausen due to the increased number of personnel and technology . In the following years, this air force air base, built in the mid-1930s, was expanded and provided with concreted helicopter parking areas, taxiways and a maintenance hangar. On October 14, 1986, the relay and staff relocated. At this time there were 15 Mi-2 and three Mi-8 in stock. On December 1, 1986, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the border troops of the GDR, the honorary name " Albert Kuntz " was given to the helicopter unit.

With 52,290 inhabitants (1989), the city was one of the most populous in the Erfurt district and was the second largest industrial center. Around 1989, around 25,000 people were employed in the factories that manufactured numerous products for the entire GDR. The most important ones included a. the IFA engine works , the VEB shaft sinking and the RFT Fernmeldewerk , were produced in which all the telephones for the GDR. The VEB Nordbrand was considered the "largest and most modern spirits producer in the GDR", while VEB Tabak was the "largest cigarette manufacturer in the republic"; until the end of the 1990s was u. a. produced the cigarette brand Cabinet .

On October 31, 1989, around 25,000 people met at August-Bebel-Platz for the first open demonstration against the GDR regime; on November 7, 1989, around 35,000 to 40,000 participants gathered. On December 4, 1989, members of the New Forum occupied the district office of the AfNS - the former district office of the MfS - in Dr.-Kurt-Fischer-Straße (today Ludolfinger Straße 13) and prevented further destruction of files. After Peter Heiter (SED) resigned as mayor in February 1990 , Olaf Dittmann ( NDPD ) held the office. On May 6, 1990, the doctor Manfred Schröter (CDU) became the first freely elected mayor.

Nordhausen in reunified Germany

Since October 14, 1990, Nordhausen has belonged to the state of Thuringia as a district town . The last Soviet soldiers left their garrison by the end of July 1991.

On July 1, 1994, Nordhausen received the status of a large district town in the course of some incorporations.

The Nordhausen University of Applied Sciences was founded in 1997, and Nordhausen has been connected to the federal motorway 38 since 2002 .

Large parts of the city center, such as the Petersberg, were renovated as part of the Nordhausen State Garden Show in 2004 . Since May 1, 2004, Nordhausen is officially a “ university town ”. On December 1, 2007, Petersdorf , Rodishain and Stempeda were incorporated.

On September 23, 2008, the city received the title “ Place of Diversity ” awarded by the federal government . Nordhausen has been the 17th fair trade city since June 5, 2010 . In 2012 she was accepted into the " Hanse City Association ". Nordhausen was the first city to officially join the Reformation by a council resolution in 1524 and is a member of the Federation of Luther Cities . Since February 2015 she has been a member of the organization " Mayors for Peace ".

swell

- Address books of the city of Nordhausen from 1824 to 1948

- Peter Kuhlbrodt (edit.): Special inventory of sources on the history of the Free Imperial City of Nordhausen in external archives . Nordhausen 2012.

- Günter Linke (edit.): Nordhäuser document book. Volume 1: The imperial and royal documents of the archive . Nordhausen 1936.

- Gerhard Meissner (edit.): Nordhäuser document book. Volume 2: Documents from princes, counts, lords and cities . Nordhausen 1939.

- Robert Hermann Walther Müller (Hrsg.): History of the Nordhäuser city archive . Nordhausen 1953. Digitized.

- Robert Hermann Walther Müller (Ed.): Official register of the imperial city of Nordhausen 1312-1345. Liber privilegiorum et Album civium . Nordhausen 1956.

- Johann Christoph Sieckel: The unfortunate after two. Kayserl recovered from fire-fires. fr. Imperial city of Nordhausen, after its name, antiquity and description of its streets . Coeler, Nordhausen 1753.

- Hermann Weidhaas: Half-timbered buildings in Nordhausen . Berlin 1955.

literature

history

- Mathias Seidel: The Southern Harz Foreland from the Pre-Roman Iron Age to the Migration Period - On the settlement history of an old settlement landscape in northern Thuringia (Weimar Monographs on Prehistory and Early History, 41), Beier & Beran, Weimar 2006.

- RH Walther Müller: Merwigslinde, Pomei Bog and Königshof (= local history research of the Nordhausen city archive, Harz. Volume 7). Neukirchner, Nordhausen 2002, ISBN 3-929767-53-8 .

- Peter Kuhlbrodt: Nordhausen - an imperial city in the century of the Reformation (= series of publications by the Friedrich Christian Lesser Foundation. Volume 30). Atelier Veit, Nordhausen 2015, ISBN 978-3-930558-26-2 . content

- Arthur Propp: The industrial development of Nordhausen . Klinz, Halle 1935. Digitized

- Heinrich Stern (text), Hans Wolff (pictures): History of the Jews in Nordhausen. Self-published, Nordhausen 1927 (new edition edited by Manfred Schröter and Steffen Iffland. 2008, ISBN 978-3-939357-07-0 ).

- Stadtarchiv Nordhausen (Ed.): Local history research by the Stadtarchiv Nordhausen, Harz . Volume 1.1953 to Volume 7.1995; Volume 8 since 2002. Geiger, Horb am Neckar, ISBN 3-89570-883-6 .

- Marie-Luis Zahradnik: From the imperial city protection Jew to the Prussian citizen of the Jewish faith. Chances and Limits of the Integration of the Nordhausen Jews in the 19th Century (Series of the Friedrich-Christian-Lesser-Stiftung, Vol. 37), Nordhausen 2018, ISBN 978-3-930558-33-9 .

Nazi era and World War II

- Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber visor . Neukirchner, Nordhausen 2000, ISBN 3-929767-43-0 .

- Peter Kuhlbrodt: Inferno Nordhausen. Fateful year 1945 (= research on local history by the Nordhausen City Archives, Harz. Volume 6). Archive of the city of Nordhausen, Nordhausen 1995, ISBN 3-929767-09-0 .

- Jens-Christian Wagner : Production of Death. The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Wallstein, Göttingen 2001 (2nd edition 2004), ISBN 978-3-89244-439-8 .

- Martin Clemens Winter: Public memories of the aerial warfare in Nordhausen. Tectum, Marburg 2005, ISBN 978-3-8288-2221-4 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Harry Bresslau and Paul Kehr (eds.): Diplomata 16: The documents of Heinrich III. (Heinrici III. Diplomata). Berlin 1931, pp. 125–126 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Pierre Fütterer: ways and rule. Investigations into the development and recording of space in East Saxony and Thuringia in the 10th and 11th centuries (= Palatium. Volume 2). Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-7954-3064-1 , Vol. 1, pp. 296-301.

- ↑ a b c Manfred Niemeyer (Ed.): German book of place names. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-018908-7 , p. 457.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Graul: Nordhuse - Nordhausen. Nordhausen-Salza 2005, p. 46.

- ↑ a b Women's project at the Environmental Academy North Thuringia eV (Ed.): Refreshments from the region. Nicknames from the Nordhausen district. Auleben 1999. p. 19.

- ↑ Mario Küßner: An extraordinary tomb at the transition from the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Bronze Age near Windehausen (Nordhausen district) , in: Contributions to the history of the city and district of Nordhausen (2017) 164–178 ( digitized , PDF).

- ↑ Erika Schmidt-Thielbeer: A cemetery of the early Bronze Age near Nohra, Kr. Nordhausen , in: Jahresschr. Hall 39 (1955) 93-114. Paul Grimm , Wolfgang Timpel, Johannes Löffler, Eva Blaschke gave an overview of the ground monuments in The prehistoric and early historical ground monuments of the Nordhausen district , Museum for Prehistory and Early History Thuringia , Nordhausen 1974.

- ↑ Michael Meyer : Locals and Migrants. Settlement systems in the Iron Age southern Harz foreland , in: Svend Hansen , Michael Meyer (Ed.): Parallele Raumkonzepte , de Gruyter, 2013, S: 281–292.

- ^ In: Bielen district on the official website of the city of Nordhausen (accessed on April 29, 2019).

- ↑ Christoph Albrecht: The Slavs in Thuringia. A contribution to the definition of the western Slavic cultural border of the early Middle Ages. [= Annual publication for the prehistory of the Saxon-Thuringian countries, Vol. 12, 2.], Halle 1925. ( Reception )

- ^ Christian Zschieschang: The Hersfeld tithe directory and the early medieval border situation on the middle Saale. A study based on names. (= Research on the history and culture of Eastern Central Europe, Vol. 52) Böhlau, Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-412-50721-3 ( PDF )

- ^ Robert Hermann Walther Müller: The Merwigslindensage in Nordhausen. A monument to the early history of Thuringia. , Series of publications on local history research by the Nordhausen City Archives, Harz / No. 1, City Council, Nordhausen 1953, p. 34.

- ↑ Pierre Fütterer: ways and rule. Investigations into the development and recording of space in East Saxony and Thuringia in the 10th and 11th centuries (= Palatium. Volume 2). Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-7954-3064-1 , vol. 1, p. 298f. Note 1350: "However, archaeological finds do not support this assumption so far."

- ↑ This and the following according to Karlheinz Blaschke : Nordhausen , in: Lexikon des Mittelalters , Vol. VI, Lachen am Zürichsee 1999, Sp. 1236.

- ^ Paul Kehr (ed.): Diplomata 8: The documents of Ludwig the German, Karlmann and Ludwig the Younger (Ludowici Germanici, Karlomanni, Ludowici Iunioris Diplomata). Berlin 1934, pp. 238–241 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ^ Certificate of Heinrich I. No. 20 Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 12: The documents Konrad I., Heinrich I. and Otto I. (Conradi I., Heinrici I. et Ottonis I. Diplomata). Hannover 1879, pp. 55–56 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Imperial certificates in illustrations

- ↑ Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 12: The documents Konrad I., Heinrich I. and Otto I. (Conradi I., Heinrici I. et Ottonis I. Diplomata). Hanover 1879, pp. 70–71 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II and Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hanover 1893, pp. 538–539 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II and Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hanover 1893, pp. 539-540 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Bernd Schütte : Investigations into the life descriptions of Queen Mathilde (MGH, Studies and Texts Vol. 9). Hahn, Hannover 1994, ISBN 3-7752-5409-9 .

- ↑ Hans K. Schulze : The marriage certificate of Empress Theophanu , p. 32. Regest in: Hans K. Schulze: Die Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu , p. 89.

- ↑ August von Wersebe: Description of the district between the Elbe, Saale and Unstrut, Weser and Werra. Published by Hahn'schen Buchhandlung, Hanover 1829, pages 59

- ↑ Hans Oelze: The economic life of the city of Nordhausen am Harz in the last two centuries of its imperial directness (17th and 18th centuries). Trosse, Nordhausen am Harz 1933. p. 6.

- ^ Werner Mägdefrau : The Thuringian Association of Cities in the Middle Ages . Böhlau, Weimar 1977, p. 145.

- ↑ Bernd Schmies: Structure and organization of the Saxon Franciscan Province and its Thuringian Custody from the beginnings to the Reformation. In: Thomas T. Müller , Bernd Schmies, Christian Loefke (eds.): For God and the world. Franciscans in Thuringia. Paderborn u. a. 2008, pp. 38–49, here p. 43.

- ↑ Claus Priesner : Johann Christian Bernhardt and vitriolic acid. In: Chemistry in our time , 1982, 16, 5, pp. 149-159; doi: 10.1002 / ciuz.19820160504 .

- ↑ a b Rudolf Eckart : Memorial sheets from the history of the former free imperial city of Nordhausen . Leipzig 1895, p. 22.

- ^ Ernst Günther Förstemann; Friedrich Christian Lesser: Historical news of the formerly imperial and the Heil. Roman imperial free city of Nordhausen printed there in 1740 . Nordhausen 1860, p. 245.

- ↑ Ronald Füssel: The witch persecutions in the Thuringian area (= publications of the working group for historical witchcraft and crime research in Northern Germany. Volume 2). Hamburg 2003, p. 252 f.

- ↑ gutenberg.org

- ↑ After 1945 the stadium was named Ernst-Thälmann-Stadion .

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death . Wallstein, Göttingen 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death . Wallstein, Göttingen 2004, p. 132.

- ^ Stadtarchiv Nordhausen (ed.): Chronicle of the city of Nordhausen. 1802 to 1989 (= local history research by the Nordhausen City Archives, Harz. Volume 9). Geiger, Horb am Neckar 2003, ISBN 3-89570-883-6 , p. 343.

- ^ Heinrich Keizer - NordhausenWiki, accessed on August 21, 2020.

- ^ Stadtarchiv Nordhausen (ed.): Chronicle of the city of Nordhausen. 1802 to 1989 (= local history research by the Nordhausen City Archives, Harz. Volume 9). Geiger, Horb am Neckar 2003, ISBN 3-89570-883-6 , p. 346 ff.

- ↑ Nordhausen under National Socialism: Adolf Hitler House ( Memento of the original from November 29, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed October 16, 2013.

- ^ Stadtarchiv Nordhausen (ed.): Chronicle of the city of Nordhausen. 1802 to 1989 (= local history research by the Nordhausen City Archives, Harz. Volume 9). Geiger, Horb am Neckar 2003, ISBN 3-89570-883-6 , p. 391.

- ^ Stadtarchiv Nordhausen (ed.): Nordhäuser news. Südharzer Heimatblätter . 1.2014, p. 10.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner: Nordhausen (Boelcke barracks). In: Wolfgang Benz , Barbara Distel (eds.): The place of terror . History of the National Socialist Concentration Camps. Volume 7: Niederhagen / Wewelsburg, Lublin-Majdanek, Arbeitsdorf, Herzogenbusch (Vught), Bergen-Belsen, Mittelbau-Dora. C. H. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-52967-2 , p. 320 f.

- ↑ Thuringian Association of the Persecuted of the Nazi Regime - Association of Antifascists and Study Group of German Resistance 1933–1945 (Ed.): Heimatgeschichtlicher Wegweiser to places of resistance and persecution 1933–1945 (= Heimatgeschichtliche Wegweiser. Volume 8: Thuringia ). Erfurt 2003, ISBN 3-88864-343-0 , p. 192 ff.

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomb sight. P. 61 f.

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomb sight. P. 221 f.

- ^ Stadtarchiv Nordhausen (ed.): Chronicle of the city of Nordhausen. 1802 to 1989 (= local history research by the Nordhausen City Archives, Harz. Volume 9). Geiger, Horb am Neckar 2003, ISBN 3-89570-883-6 , p. 401 f.

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, pp. 20, 32.

- ↑ a b balance sheet of horror , heinz-ruehmann-gedenkseite.de

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner (ed.): Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp 1943–1945. Göttingen 2007, p. 185 f.

- ^ A b Peter Kuhlbrodt: The fateful year 1945 - Inferno Nordhausen. 1995, ISBN 3-929767-09-0 .

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomb sight. P. 158 f.

- ↑ Nordhausen by Rudolf Zießler . In: Fate of German Monuments in the Second World War. Edited by Götz Eckardt, Henschel-Verlag, Berlin 1978.

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 115.

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 126.

- ↑ Jürgen Möller : The fight for the Harz April 1945 . Rockstuhl, Bad Langensalza 2011. p. 127.

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, pp. 48, 63.

- ↑ a b Joachim H. Schultze: The city of Nordhausen. A structural study of their geography, their living and environmental relationships; Assessment; completed in February 1947. p. 46.

- ^ Filmtheater "Neue Zeit" Nordhausen at NordhausenWiki. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Hubertus Knabe : June 17, 1953. a German uprising . Ullstein-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-548-36664-3 , pp. 91-92.

- ^ Secret report of the district authorities of the People's Police on June 17, 1953 (June 29, 1953)

- ↑ The cry for freedom. June 17, 1953 in Thuringia . Catalog for the exhibition of the Ettersberg Foundation on the 50th anniversary of June 17, 1953. Last shown in June 2012 in the Thuringian state parliament

- ^ Fritz Kirchner, Horst Propp: 1050 years of Nordhausen. Contributions to the history of the city of Nordhausen / published by the council of the city of Nordhausen on behalf of the commission for research into the history of the local labor movement at the district leadership of the SED. Nordhausen City Council, Nordhausen 1977, DNB 800809793 , OCLC 612355538 , p. 4.

- ^ Lutz Jödicke: From the radio archive : Nordhausen and the GDR tour. In: Stadtarchiv Nordhausen (Ed.): Nordhäuser News: Südharzer Heimatblätter . Volume 27, No. 2. Iffland, Nordhausen 2018, 1030841349 in the GVK - Common Union Catalog , pp. 20-21.

- ↑ Thomas Bussmann: Reinforced concrete, grass and railway lighting. The military airfields of the GDR. MediaScript, Cottbus, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-9814822-0-1 , pp. 136/137.

- ↑ Timeline of the military history of the German Democratic Republic from 1949 to 1988 . 2nd, expanded and reviewed edition, Military Publishing House of the GDR, Berlin (GDR) 1989, ISBN 3-327-00720-9 , p. 577.

- ↑ a b c d e Flohburg , the Nordhausen Museum (ed.): "Revolution of the candles" in Nordhausen 25 years ago (= Nordhäuser Flohburgblätter. Issue 3). Nordhausen 2015, DNB 104398173X , ISSN 2199-4099 , p. 6.

- ^ Minister of Social Affairs presented the award certificate - From May 1st: "Hochschulstadt Nordhausen". City website, accessed June 6, 2018 .

- ^ StBA: Changes in the municipalities in Germany, see 2007

- ↑ www.fairtrade-towns.de. German website of the campaign / German list of cities on the campaign page, accessed on June 7, 2018 .

- ↑ Mayor Rike signs Nordhausen's entry into the Hanseatic League. Thüringer Allgemeine , accessed on January 22, 2015 .

- ^ Address books Thuringian cities: Nordhausen (April 21, 2019).