Prehistory of Greece

The prehistory of Greece ranges from the earliest human traces to the beginning of a broader written tradition.

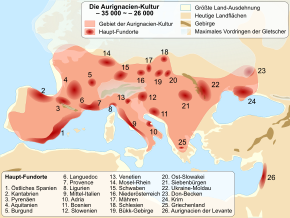

Paleolithic

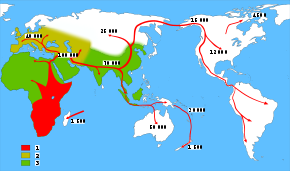

Due to its location, Greece may have played a significant role in the first colonization of Europe by members of the human species . However, potential archaeological sites were destroyed by climatic changes, tectonic activity, the relief of the landscape and floods in the alternation of warm and cold periods.

Old and Middle Paleolithic

Only a few sites can be assigned to the Old or Middle Paleolithic due to similarities with dated industries , such as Kokkinopilos in Epirus . This locality shows characteristics of the Moustérien . Rodia in Thessaly's knockoff and blade industry with only a few hand axes was estimated to be 200,000 to 400,000 years old. The Rodafnidia site on Lesbos can possibly be assigned to the Acheuléen . This would make it the oldest site in Greece.

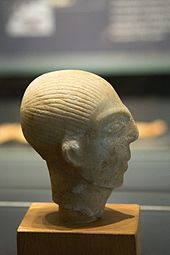

Few human remains have been excavated to date. The skull of a man about 30 years old was discovered in 1960 in the stalactite cave of Petralona on the Chalkidiki peninsula . The dead was at times referred to as Archanthropus europaeus petraloniensis . It was dated to an age of 160,000 to 240,000 years in 1981, and two decades later to at least 300,000 years. According to both dates, the fossil can be assigned to the late Homo heidelbergensis .

In the Greek part of Thrace , mainly choppers , i.e. rubble tools, were found. In the Turkish part of Thrace, more precisely on the northern edge of the lagoon of Küçükçekmece ( Küçükçekmece Gölü ), about 1,600 artifacts were found in the caves of Yarımburgaz, the oldest of which was dated to about 400,000 years. Probably Homo erectus first inhabited the cave. Mostly flint was used, but also quartz and quartzite . Overall, the industry is similar to that of the Rodia and Doumbia caves in Thessaly and Macedonia.

The stone artefacts of the more recent sites indicate the new stone processing technique that emerged at this time, known as the Levallois technique , and which is assigned to the Neanderthals . Artifacts of this have now also emerged on the Peloponnese and on Naxos at the Stélida site. It is unclear whether Naxos was temporarily accessible during the ice ages, but the ability to cross larger bodies of water is conceivable. In the Epirotic cave of Asprochaliko, 4 km northeast of Kokkinopilos in the valley of the Louros , the lowest layers have been dated to 100,000 years; In the nearby Kokkinopilos, field finds indicate the presence of Neanderthals 150,000 years ago, but this is controversial. Four kilometers west of the site PS 43 is the mesolithic , i.e. significantly younger site PS 3, in PS 43 the presence of arrowheads indicates hunting activity, the absence of sickles for the time before the Neolithic. This could be a criterion for the limitation, but the early farming residents may have hunted beyond the corresponding settlements. In the Peloponnesian Lakonis on the Laconic Gulf , several sites that are between 100,000 and 40,000 years old have appeared in the last decade. Among them was the tooth of a Neanderthal man from Laconia , which is assigned to the transition period to anatomically modern humans.

On Crete , artifacts were found in the Megalopotamos gorge above the palm beach of Preveli , which were dated to an age of 130,000 years. They were not only among the oldest finds in the country, but also proved that Neanderthals were able to cover greater distances across the sea. Their typical Moustérien stone tools were also discovered on the islands of Lefkada , Kefalonia and Zakynthos . Neanderthal groups lived at the same time along the rivers in Macedonia and Thessaly, because traces of corresponding camps were found on some of the well-preserved terraces. This is especially true for the area west of Larissa . The wide plains with their rivers attracted those prey animals on which the Neanderthals mostly lived. In the north, artifacts were found in the caves of Rodia and Doumbia in Thessaly and Macedonia. Rodia is currently the oldest find place. It has been dated to between 200,000 and 400,000 years. After that, a long time gap appears that only ended 60,000 years ago when Neanderthals reappeared. They show seasonal migrations, which were undertaken mainly to use natural resources along the rivers, but also those of the coastal marshland. Artifacts were also found on rock overhangs and in narrow valley passages, from which the grazing herds could be observed and hunted.

Upper Paleolithic

A hallmark of the Upper Paleolithic is a new stone processing technique. Flint was processed in a new blade concept with the creation of a "guide ridge". This means that a vertical dorsal ridge was created on the core , which enabled long, narrow cuts to be cut off. These are called blades.

During the largest ice age glaciation around 28,000 to 20,000 BC. BC (according to other sources 24,500 to 18,000 BC) - the last Neanderthals had long since disappeared - the sea level was 100 to 130 m lower than today. The subsequent increase was caused by the melting of the huge ice masses, which dragged on for thousands of years. The strong fluctuations in sea level destroyed archaeological artifacts, especially in the plains near the coast.

It is almost impossible to have any vague idea how many people were around 20,000 BC. Lived in Europe. As an experiment, the population, taking into account the ecological conditions of an advanced glacial period, has been estimated at perhaps 6,000 to 10,000. These were our immediate ancestors who came to Europe about 45,000 years ago.

A key site is the Franchthi Cave in the northeast of the Peloponnese, which has been visited again and again for 100,000 years. In addition, there is the Thessalian Theopetra Cave , which was visited from the Middle Paleolithic to the Neolithic, but also Mesolithic finds in the Klissoura Cave in the north-eastern Peloponnese or the Cyclops Cave on the Sporades . Theopetra lies in the transition area from the Thessalian plain to the Pindus . The oldest layers belong to the early Middle Paleolithic, and they may go back even further. Most of the finds, however, belong to the period 50 to 30,000 years ago. The hunters lived in a steppe landscape where they ambushed bears and deer. This phase was followed by a further usage phase, which ranged from 38,000 to 25,300 BP . The people displaced by the increasing cold did not return until 15,000 years ago. They stayed until 11,000 years ago.

After the maximum of the last glacial period , which was also a pronounced dry season in Greece, the temperature rose again about 18,000 years ago, but the country remained dry for a long time. Hunting camps can now also be found in higher regions, such as in Epiros , where the climate became milder. Apparently, the exchange contacts expanded, because in the Theopetra Cave there were tools made of material that no longer came from the area or was collected along the hiking cycles, but came from more distant areas. In summer, hunting groups moved to the Pindus Mountains, which became more attractive to the herds of animals who preferred open grasslands. The lower plains began to forest.

The Klithi Cave in North Epiros near Konitsa was visited by the said late glacial hunters, mostly in small groups of 5 to 10, maybe up to 20 people, probably families, over and over again in the warm season for several months. This happened between 16,500 and 13,000 BP, i.e. in the time between maximum glaciation and the beginning of the return of the forests in the course of global warming. 99% of the bones found in the cave came from goats and chamois . The animals were processed into food, artifacts and clothes in the cave. While plant food was of great importance in the plains and valleys, it hardly played a role in the mountains. In contrast to Klithi, numerous groups of hunters met at the site near Kastritsa. The third important site in Epiros, Asprochaliko, is smaller. It is the oldest site of these transhumant hunting groups (26,000 BP). With the advance of the forests, the prey disappeared from the region or retreated to the higher mountain ranges, so the hunter families had to change their summer location.

The exchange or trade can be more precisely defined towards the end of the last glacial period. The most important recognizable barter object in the Mediterranean area were initially mussels, then certain types of stone, which were of great importance for the production of equipment, especially if they were of high quality. This was true for the rare obsidian , for example . Around 10,000 BC BC obsidian came from the island of Melos into the Peloponnesian Franchthi cave, which dates from around 30,000 to 3000 BC. Was visited.

Mesolithic

When the huge glacier masses of the north and in the mountains began to melt - the last time it came in the Younger Dryas between 10,730 and 9,700 / 9,600 BC. Chr. To a strong cooling -, countless lakes and rivers arose. At the same time, the freed land masses were relieved of the pressure of the ice and rose. However, the water level of the oceans rose considerably more. This rise reached 120 to 130 m. The large herds of animals, dependent on tundras or other forest-free areas, disappeared, moved northwards or into the higher mountain areas.

The Upper Paleolithic big game hunters now shifted to small game, increasingly lived on vegetables, and developed new devices and weapons. Wild goats, deer, pigs and rabbits, but also birds, appeared as a hunting spectrum. Now coniferous forest spread in the higher elevations, oak in the lower. A Neolithic use took place in the Theopetra Cave from 8,000 to 6,000 BC. Chr.

The range of tools shows that Greece was relatively isolated and was hardly affected by cultural changes in the surrounding metropolitan areas. Fishing, especially tuna , increased significantly. Hunting and gathering only provided additional food. Since the fishermen also followed the seasonally growing fish population, their lives were characterized by corresponding hikes to the best fishing spots. Their stone artifacts are much smaller and are known as microliths . These were mostly components of tools and weapons that were used for catching, processing and storage. The plant remains of the Franchthi Cave include wild plants, nuts and grain.

It is unclear whether the stones that were needed to manufacture the devices, and that came from an ever larger area, indicate a kind of territory in which certain groups had privileges. It could also be a large trading network. The Cyclops Cave on the now uninhabited Sporade island of Gioura , 30 km from Alonnisos , was built from 8700 to 7000 BC. Visited regularly. On another island of the archipelago, on Kythnos , traces of round huts were found, which can also be assigned to the changed economic method, which has been described as the "broad spectrum revolution". There was a shift from large game to a wide range of small animals, plus vegetables, a shift that evidently gradually made survival more secure. The Mesolithic, it was postulated, would soon have used grain, but most archaeologists believe these finds to be floods from higher strata. The investigation of the Gioura obsidian tools was able to prove the origin of the Cycladic island of Milos , while tools show a resemblance to finds from the area of Antalya , which led to the conclusion that the inhabitants of Gioura had extensive contacts and had extraordinary navigation skills.

Mesolithic finds on the Cycladic island of Kythnos at the Maroulas site from 1996 to 2005 uncovered what is probably the oldest settlement in the Cyclades. It was built between 8600 and 7800 BC. Dated. The advancement of the coastline destroyed a large part of the settlement area, the remaining area extends to about 1500 to 2000 m². At the same time, only a few centimeters below the surface of the earth, the oldest burial grounds were found there.

In Franchthi the dead were buried close to the living. Ocher and personal jewelry came increasingly into use. The people lived in a network of contiguous camps. It turned out that there were micro-landscapes in Greece, small districts in which numerous sites could be identified.

Another way of life, the hunt for corresponding middle and high mountain animals, could be proven in the mountain regions between Epiros and Thessaly / Macedonia in over 90 places. There, the search was based on comparatively flat terrain at altitudes between 1400 and 1900 m. But here too the advancing forest soon ended the era of hunting. The following epoch, dominated by rural cultures, the Neolithic, received only a few contributions that are considered Mesolithic. This is in contrast to other regions of the Mediterranean and can be used as a further indicator that the number of hunters, gatherers and fishermen in Greece was comparatively low.

Neolithic (from 7000 BC)

Temporal structure and breaks in social development

The Neolithic in Greece is usually divided into four phases, namely the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic (from 7000 BC), the Early Neolithic (from 6500 BC), the Middle Neolithic (from 5800 BC) and the Late Neolithic ( from 5300 BC). The Neolithic settlements were seen as small, isolated and almost static in comparison to the impressive sites of the subsequent Bronze Age . In addition, they were denied social stratification as well as manual differentiation or more than mere subsistence farming. The Neolithic became a foil against which the rise of Greece could be re-enacted. The presentation of the usual cultural sequences was reduced to the question of origin, which meant that their complexity and their possibilities fell out of view. At the same time, slow changes in retrospect were stylized as revolutions, in the worst case the mere technical progress brought to the fore, which was usually expressed in an allegedly increased mastery of nature. This turned historical processes into a “caricature”.

The work of the last decades came to the conclusion that the fractures were by no means as hard as claimed. On the contrary, the Neolithic and Bronze Age had much in common. This included handicraft differentiation as well as a broad agricultural base with strong regional differentiation, gardening, but also agricultural surpluses and an economy driven by leadership groups as well as social competition. Local, regional and long-distance contacts were also part of both epochs, including ritual gatherings to strengthen and develop togetherness, identity and values. However, social competition was even more strongly controlled by social control. Even the advent of trade in metal, wine and olives (the latter from the end of the 5th millennium in western Crete and in Macedonia), formerly attributed to the Bronze Age, appeared as early as the Neolithic. So there is no break between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. Such a continuity was finally postulated for the question of urbanization. However, it turned out that some settlements were very extensive, so that the Cretan Knossos measured about 5 hectares, the Thessalian Sesklo 13, the Macedonian Vasilika even 25 hectares, but it turned out that these places were very sparsely populated. Excavations in Knossos, for example, showed that the inhabited part of this extended settlement had to be reduced to 2 to 2.5 hectares.

On the other hand, the transition between the Mesolithic and the Neolithic seems to have been all the more drastic, even if here the signs of continuity are increasing even in Greece, where the break was considered particularly radical.

Phases of socio-economic change can be seen in the Neolithic around 5500/5300 and around 3500–3100 / 3000 BC. Grasp. In the early Neolithic, stocks on the house level, i.e. probably on the level of the extended family, cannot be grasped, so that it is assumed that the stockpiling took place at the level of the settlement. In Knossos, for example, an adobe structure was found that was apparently used to store grain. From this the conclusion was drawn that the settlements, which were often extremely long-lived, shaped production as well as the presentation of their origins, their values and their identity. Internal competition may have been channeled by maintaining remote contacts in order to get goods that came from far away. Such gifts gave rise to prestigious and status-promoting displays, but also to the associated acquisition stories that did not undermine the dominant community.

Around 5500/5000 BC BC, however, the household, the extended family, came to the fore. The space occupied by their 70 to 100 m² houses in the settlement was more clearly delimited. In turn, “public” spaces were created more separately from this. This impression is reinforced by clay house models, which now appeared more frequently. This demarcation enabled the emergence of small settlements of less than 0.5 hectares, which in turn enabled the development of previously unused regions. In the late Neolithic there was a significant intensification and specialization of production, for example of ceramics. There are also references to weaving, olive and wine growing. So at the family level, specialization may have taken place. Supplies have now been set up there as well, suggesting greater control over production and storage. Nevertheless, the community remained the place of the rites, it still had a strong influence on ideological and economic activities and found, for example, in Dimini's megaron (and its surroundings) a monumental place for staging individual and family competitions.

Between 3600/3500 BC BC and the early Bronze Age, the hotplates moved into the houses or they were structurally connected to the respective house. The spread in up to then marginal areas took place in Crete around 3300 to 3000 BC. In the Peloponnese and the Cyclades a little later, but certainly in the Early Bronze Age (in Thessaly we know the late Neolithic as the Rachmani culture ). This expansion was a network of small settlements, and these areas required economic specializations, such as keeping cattle. The small settlements, which could be broken down to the family in times of need, continued to maintain contacts, but they were more on their own and in the long run, failures could hardly be compensated for by the neighbors. On the other hand, it made competition more obvious in terms of success or failure. This may have led to the first forms of indebtedness to property and work, further specialization or emigration. An alternative was trading. The scope and role of trade changed. Numerous new settlements emerged along the coasts of the southern Aegean, many of which can be traced back to the Bronze Age. Settlements like Paoura on Kea or Petras Kephala on Crete were no smaller than the large trading centers of the Bronze Age with an area of 1 to 2 hectares. This was probably the first time that privileged access to techniques and approaches came to the fore, while gift traffic lost its importance. In Strofilas on Andros there were pictorial representations of the associated means of transport, namely long boats. In Petras-Kephala, raw metals and obsidian were landed and processed there. Apparently, trade was carried out from there to the hinterland. The dispute over every single point, from the extraction of raw materials through transport, storage and further trading to the buyer, who could now set conditions for his part, began, because with the discovery of these prestigious goods a demand was stimulated at the same time. At the same time, households became separate, fully functional economic units, almost “modular” households that could acquire and accumulate goods without interference from the community. But they also came into competition with other economic units of this kind. This was especially true for the status and prestige sector, which was reflected in public rituals, such as more elaborate tombs and burials on Euboea, the Cyclades and in Attica in the form of burial sites outside the walls. In addition, the development of the palace courtyards emerged, as they are richly documented for the Bronze Age.

For a long time it was assumed that all societies were driven by technology, then by population pressure. It is now becoming clearer that identifiable groups with a very specific framework for action are responsible for the changes. Technologies don't spread because they're so good, but because people choose to use them. The population only grows when the socio-economic organization changes. Climatic changes are of considerable importance. Such is the period from 7000 to 5500 BC. Chr. Characterized by a very favorable climate, which was more humid and milder and which showed less seasonal fluctuations. Then the fluctuations increased from year to year, and around 3500 BC. The weather was similar to today's, so it was drier. The weather never determines the direction of social developments, but it has the potential to rob traditional societies of stability. In such difficult times, the weaknesses of the previously stable system become apparent, trust sinks and new paths have the prospect of being no longer involved.

Cultural connections to Anatolia in the early Neolithic

The change from the Meso- to the Neolithic was of a completely different nature. The settlements, which started around 7000 BC. They originated in Greece in BC, were of great uniformity and, above all, differed significantly from their Mesolithic predecessors. In addition to tillage and livestock farming, the newcomers brought with them various techniques such as spinning, polishing stones, building houses or pressure flaking , a stone- working technique that was only recognized late. The cattle did not come from local ancestors either, but from those who had brought them with them. The contribution of the Mesolithic to the newly emerging large-scale culture grew in the Mediterranean, roughly speaking, from east to west. In Greece, which was close to the Middle Eastern radiation centers of the new way of life, their contribution was apparently small. It was probably different groups from the eastern Mediterranean that reached Greece. In the oldest Neolithic settlements, the use of clay was limited to figurines and ornaments, similar to the eastern centers of radiation in the Middle East and Cyprus.

Genetic studies on the oldest Neolithic human remains in Greece were able to show that the mainland Greek settlers were more closely related to those in the Balkans, while the inhabitants of the islands were closer to the inhabitants of central and especially the Mediterranean Anatolia. In addition to studies on bread or common wheat , this indicates that there was a split of settlers towards northern Greece and the Balkans or towards Crete, Peloponnese and southern Italy, which already occurred in the early Neolithic. Therefore, common wheat is almost characteristic of the southern Anatolian, Cretan, but also the Italian groups. In all likelihood they were moving across the sea. This split can also be demonstrated in the DNA of the animals that were apparently carried along, above all sheep and goats, pigs and cattle. The domesticated animals reached around 7000 BC. Western Anatolia, the area north of the Bosporus around 6200 BC. In order to find further distribution on two or three routes from there. The main routes of distribution led across the Mediterranean, the Balkans and around the Black Sea, where Neolithic settlements around 6000 BC were found in the Caucasus region. Can be proven. With the spread of peasant culture, further genetic studies seem to have played a decisive role in reproductive advantages over the neighboring hunter-gatherer societies.

The cultural contexts that can be documented in Western Anatolia also fit this picture, but these relate more to fishermen and hunters. In Fikirtepe, east of Istanbul, their presence could be proven by their oval and rectangular houses made of clay wicker, as well as by incised ceramics. The site gave the name to the Fikirtepe culture . Their late Neolithic pottery was found westwards as far as Thessaly.

The newcomers preferred settlement sites, the basics of which were similar to those they knew from their homeland. Semi-arid areas with open woodlands were the typical basis for using plants and animals as farmers and shepherds. The cooler, more humid mountain areas of the north were initially excluded, but also the dry south-eastern mainland or the Cyclades, which were not affected by the new way of life until the late Neolithic. So it is not surprising that the great plains of Thessaly, Macedonia and Thrace have a large number of sites, so-called Tell settlements of larger dimensions, while the rest of mainland Greece was rather sparsely populated. Smaller settlements, probably based more on relatives and families, dominated there. However, recent studies show that in the Tell areas there were not only the conspicuous settlements built on hills, but that there were also flat settlements there, which, however, had escaped the eye of archaeologists for a long time. Finds in the Cyclades show that the find situation is not always so clear. The bones that were discovered on the island of Gioura are considered to be the oldest finds of (wild) pigs. They were dated to 7530–7100 BC. Dated.

Secondary products

Less attention was paid to the advanced Neolithic phase, referred to by Andrew Sherratt as the “ second Neolithic revolution ”, in which animals were not only used as meat suppliers, but also for the production of wool and milk or as carriers and draft animals. According to Sherratt, this innovation spread from Mesopotamia via Anatolia to Greece and the Balkans.

Two developments changed the situation in agriculture to a great extent. This included a simple hook plow , which could not be operated by humans but pulled by cattle. This not only changed the use of force, but also the time required. In addition, this opened up new soils in drier areas that were previously inaccessible for the simpler methods.

Dairy products, such as milk itself, but also yoghurt , cheese or butter , however, required a certain amount of time for physical adaptation in order to overcome the corresponding intolerances. It is significant that especially in northwestern Anatolia from the 7th to 5th millennium this type of livestock farming was much more widespread than in the Middle East. This knowledge was also used in Crete, but apparently to a much lesser extent.

In the first half of the 7th millennium BC, Knossos on Crete was the only Neolithic settlement on the whole island. Around 6500 settlements appear on other Aegean islands as well.

There was also a specialization in predominantly animal husbandry, which in turn opened up areas that were unsuitable for soil cultivation, but offered the best conditions for grazing. This way of life was so mobile that the change of pasture with the seasons, for example between mountains and plains, opened up further areas. The Cyclades were also settled on a larger scale. At least on Naxos, there was considerable continuity. The stratigraphy discovered during the excavations in the Zas cave on Naxos is decisive for the assessment of the cultural sequence from the late Neolithic to the early Bronze Age . Overall, an expansion can also be observed in the drier areas of Crete, the Peloponnese or Thessaly.

Tell settlements

The Tell settlements consisted of adobe houses that were built over centuries, if not millennia, over and over again on the remains of older buildings, so that hills of considerable proportions were created. They are mostly known from the Middle East and Anatolia. Narrow paths separated the houses, which were functionally diversified. So there were living quarters and warehouses, as well as those for ritual purposes. The places were not expanded into the open landscape, they perhaps represented representatives of the ancestors, the origin, perhaps also symbols of a habitus of stability, a way of life tied to traditions. A social hierarchy is not recognizable, the rectangular houses are very similar to each other, which perhaps represents a reference to societies whose basis were families or lineages . This is especially true of the early Neolithic. In Thessaly one can expect 100 to 300 inhabitants per tell.

Simple structures such as in Nea Nicomedeia contrast with later settlements, such as those of the Middle Neolithic settlement of Sesklo in eastern Thessaly.

Sesklos and Dimini were the first tells of Greece to be excavated. Sesklo consisted of a kind of lower town and a smaller upper town, which is often referred to as the Acropolis . The settlement covered a total of 13 hectares, the acropolis only extended over an area of 1 hectare. Its population was estimated at 3000 inhabitants. Dimini had extensive ritual architectural relics, including circular, concentric, low, perhaps a meter high walls, in the center of which was a large building structure, which was often referred to as a megaron . This design was widespread until the early Iron Age. It is considered evidence of an emerging social hierarchy, if not a class society. For the late Neolithic it is assumed that the surrounding villages were controlled by a Sesklos leadership group and served to supply the town-like settlement. While in smaller places the population was dependent on exogamous relationships, which led to a loss of control over the surrounding land, larger settlements, beyond 500 to 600 inhabitants, were less dependent on them, so that the families could maintain the access rights to the land within the settlement. because endogamous networks of relationships stabilized the possession or at least certain access and usage rights to local families. The leading families were thus able to dispose of supplies and were given crucial importance for the survival of the community as a whole. The now reduced, up to then intensive marriage contacts with other communities increased the risk of open, violent conflicts over rights, as ethnological and historical comparisons suggest. The erection of walls and signs of destruction are evidence of increasing conflicts. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the Cretan Phaistos goes back to a late Neolithic settlement, not to say city-like settlement of 5.6 hectares, which gradually dominated the surrounding area.

At the end of the Neolithic, numerous villages and hamlets were fortified. This applies to the entire south of Greece and the Cyclades. This in turn points to intense conflicts that are likely to have had their cause in the aforementioned social and economic processes. In Attica half a dozen fortified settlements found in the area Corinth go some of the walled and turreted cities probably also to the late Neolithic back. Strofilas on Andros has a strong wall, rock carvings on the Cyclades indicate fleets of ships that were interpreted as pirate fleets. The best location, however, is in Thessaly. There are 120 known sites from the early Neolithic, just as many from the Middle Neolithic. If you disregard the south-eastern part of the eastern plain, there are on average only 2.5 kilometers between the settlements. This led to the assumption that an average village had around 450 hectares of arable land.

The tells, however, were very unevenly distributed. Half of these settlements alone were concentrated in the hill country of Central Hessen. The small territories indicate a tillage that began just outside the walls. Those areas of Thessaly that were too dry or whose soils were too heavy were apparently still avoided. However, while large parts of the country were usable over a large area and accordingly a fairly uniform settlement developed, in the drier south one was much more forced to stick to marshes, rivers or lakes.

The flat sites, which are no longer noticeable in the landscape today, were much larger than the tells; the former covered 6 to 20 ha, in rare cases up to 100, while the much more conspicuous tells were only 1–3 ha in size. However, this does not mean that they were huge, ground-level settlements, but that the houses were relocated very frequently, resulting in extensive, but very flat horizons. Here, too, it is assumed that there are 60 to 300 inhabitants per settlement. Kouphovouno was a Middle Neolithic, at least 4 hectare large, ground-level village with perhaps 500 inhabitants - so it was quite large for the difficult conditions in the drier south. It was integrated into an extensive trading network, as numerous artefacts made of obsidian, which came from the Cyclades, were found. However, Makriyalos in Macedonia has been researched best. There it turned out that the dead were buried in trenches, in one case in a pit. In addition, large accumulations of animal bones and ceramic fragments in certain places are interpreted as signs of communal rituals and celebrations.

Considerations were made as to whether the early and middle Neolithic settlements tended to work more together - for example at cooking areas between instead of in the houses - and a disclosure of the common supplies, while the late Neolithic settlements increasingly took the cooking areas into the house and hid the supplies and thus withdrawn from access to the entire settlement. This tendency from the common to the private could be demonstrated for both Thessaly and Knossos. Possibly there were previously obligations to slaughter animals in turn if necessary, whereas now each house was responsible for itself. As documented in Knossos, grain was stored in a separate communal house on the edge of the settlement. In the late Neolithic, large storage vessels appeared and storage pits were created below, but also between the houses. The quality of ceramics, which had previously been produced jointly, also lost due to privatization. A trend from sharing to hoarding, which however makes it easy to overlook the length of time the egalitarian system was stable. The factors that ended this stability remain speculative.

It is assumed that a pure shepherd economy was not possible under the conditions of Greece, so it was always a mixed economy of animal husbandry and grain cultivation, whereby the products, which were mainly supplied by the cattle, plus their labor, the keeping of Cattle are likely to have given an additional meaning. As the obsidian finds show, there was a need for a suitable medium of exchange, for which the new products were certainly a suitable medium. In times of bad harvests or animal diseases, food was probably brought about through the necessary contacts, otherwise the enormous continuity of the tells could not be explained. There was also transhumance, which opened up new pastures for the herds. In addition, there was the seasonal presence of fishermen. Pure fishing villages were also difficult to imagine at that time, because these too could mainly only go about their work in summer. For a long time it was also unclear whether the preservation of fish - a crucial prerequisite for stockpiling and storage and thus for the greater importance of the food in the course of the year - was known. In any case, drying was already known at the transition from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic on the Sporades.

Crafts, material culture, copper processing, exchange

Vere Gordon Childe developed an influential theory in the 1930s that the early Neolithic farmers produced everything they needed themselves. The exchange of raw materials and finished products was of little importance.

This only changed with the Bronze Age, when the coveted metal sparked wide-ranging and extensive trade and craft specialization. On this basis, a class of traders and professional artisans emerged outside the peasant class. An aristocracy emerged over this, which controlled traders and craftsmen and skimmed off their earnings.

While ceramics were initially mainly used to serve food, this changed towards the end of the Neolithic in that the low production increased significantly and especially cooking and storage vessels, which were previously extremely rare, increased significantly. If cooking pots were initially unknown - hot stones were placed in pits filled with water and the food, which was packed in organic casings, was placed in the boiling water - traces of fire point to a rapidly increasing use of ceramics for cooking. The earlier vessels could have been copies of leather bags, for example. Even in the Middle Neolithic Sesklo, however, more elaborate vessels with a reddish-brown geometric design on a white background appeared, especially the late Neolithic goods of the Dimini culture with a polychrome surface. However, by the end of the period, regional styles disappeared, perhaps through interregional trade.

When trading, certain stones were the focus. Until the Middle Neolithic, they were more used for carpentry work or the processing of skins, while in the later Neolithic large axes appeared that were more suitable for clearing forests. Millstones made from hard volcanic rock were also in great demand. For example, andesite from the island of Aegina was in great demand. In addition, there were certain types of mussels from which jewelry and stamps were made, the latter possibly for adorning the skin.

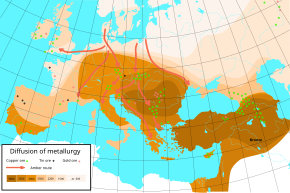

In the later Neolithic, probably already in the middle of the 5th millennium, and even more towards the end of the epoch, copper appeared as the first metal. An important mining site was located in the Bulgarian Ain Bunar, where, in contrast to Greece, where Neolithic II is preferred, the period between 5000/4800 and 4500 BC. Chr. Is called Chalcolithic or Copper Age . While copper came in extremely small quantities from outside Greece in the late Neolithic, the metal, along with silver and gold, was extracted and processed in the country. This happened on Syphnus or in the mines of Attica. The Cyclades in particular now supplied obsidian, millstones, marble and metals. Perhaps that was the only reason why they were settled. The islands became the hub of the Aegean trade in the Early Bronze Age. Perlès put forward the thesis that the extremely early trading in certain stones was possibly carried out by specialists whose mobile way of life was a relic of the Mesolithic or even the late Paleolithic.

Burial places are extremely rare in Greece. Occasionally the dead lay under the floor of the house, in each case within the settlements. Only at the end of the epoch did cemeteries appear, which were also laid out outside of the places, such as in Kephala on Kea . Since the late Neolithic, the dead were also buried in caves. But the number of burial places must have been considerably larger, as a chance find at Souphli Tell in Thessaly showed. A cremation site was found there; Something similar was found at the ground-level settlement of Makriyalos in Macedonia, where human remains tended to be mixed up with the earth.

Numerous figurines allow further insights into the symbolic level. They mostly represent domestic animals and women and have clear relationships with Anatolia. The simple classification of the female figurines as goddesses or ancestors in a kinship system oriented towards the female line, or as symbols of female or general fertility, stand alongside their interpretation as mere toys or as elements in female rituals of passage, such as puberty, marriage or childbirth. Finds in storage tanks possibly point to the separation of the gender spheres, i.e. into the female house and the male outside world. It was not until the transition to the Bronze Age that they appeared at funerals, which would perhaps assign them more to a religious sphere - but they are missing from the extremely rare Neolithic burial sites.

Bronze Age (3200/3000 - 1100 BC)

structure

The Bronze Age is usually divided into an early, a middle and a later period. The former covers the entire millennium from around 3000 to 2000 BC. BC, the middle period then extends to 1700 BC. And the later until 1100 BC. Chr.

Early Bronze Age (3000–2000 BC)

Mainland Greece in the Early Bronze Age

On the mainland, the Early Helladic I extends from 3000 to 2650 BC. BC, II to 2200 and early Helladic III to 2000 BC In the Middle Helladic, each of the three phases covers between 2000 and 1700 BC. A century. The subsequent late Helladic I extends to 1600 BC. BC, Late Helladic II to 1400 BC BC, III to 1100 BC The latter, the Late Helladic III, was finally divided again into three sections, namely the Late Helladic IIIA (up to 1300 BC), IIIB up to 1200 and IIIC up to 1100 BC. Chr.

Although the discussions about the beginning and end of the Early Bronze Age are not over, the traditional dating to the time between 3100 and 2000 BC is mostly used. BC recurs. As usual, the subdivisions are determined by differences in the ceramic. Here is Helladic period I characterized by polished ceramic and incised decoration, Helladic period II by glazed pottery ( Urfirnis ), now also black luster ware , Helladic period III by inferior glazed, dark-on-light-Ware, the decline of yellow, speckled goods and characterized by a growing proportion of undecorated ceramics. While earlier research saw a complete decline at the end of Stage III, but also a break between II and III in the south and again at the end of III a break on the mainland, breaks that - as was common at this time - related to invasions of foreigners Colin Renfrew suggested local causes for the Early Helladic III, also known as the Tiryns culture. At the transition from Early Helladic II to III one now assumes a continuity of the population on Aegina and in Lerna in the Argolis .

In Thrace, Macedonia and Thessaly there was evidence of a standardization of the various schools of ceramic production that had prevailed up to that point, as well as an increased demand for raw goods, especially storage vessels. Whether this was due to greater self-sufficiency or, on the contrary, to the need to exchange supplies for exotic goods is discussed. Little has been dug in Thrace so far, so the picture is clearer in Macedonia, where Dikili Tash has ties to Troy and Eutresis in Boeotia , but also to the north. The Sitageroi, located in the plain of Drama , represents a so-called Magoula, a tell or settlement hill. A necropolis was found near Kriaritsi in southern Chalkidiki , which was also in exchange relationships with Troy and Thessaly, but whose grave shape indicates relationships with Steno on Lefkas . In the west of Macedonia, early Bronze Age remains were found in Servia , whose connections also extended as far as Epirus. In Epirus, on the other hand, the northern influence was more noticeable, and the Doliana site has astonishingly extensive relationships, namely to the south as far as Attica , to the north as far as Moravia and Bulgaria. The drier Thessaly has far fewer connections to the north, but more intensive connections to the south. Magoules like Argissa or Pevkakia on a rock near the coast show Anatolian influence, plus a change from apsidal structures to rectangular megarons . At the same time, as is evident in Pevkakia, the first fortresses were built. Places in Attica, Kolonna on Aegina , Lerna in the Argolis or Geraki in Laconia were also fortified in the Early Helladic II.

An early, complex ceramic production could be proven in central Greek Lokris and in the hinterland. Even in Phokis , which is rather insignificant in this respect, a large burial mound was found with Kirrha . There are more sites in Boeotia , such as the large settlement of Lithares, as well as Lefkandi I and Thebes . On the Attica peninsula, settlement remains were often found on low hills; Obsidian came from Melos, but it was also related to the rest of the Cyclades, as the pottery shows. The relations of Attica in the east extended to Anatolia. Kolonna on Aegina is practically a transshipment point for the entire Koiné .

One of the key sites is the Lerna , excavated in the 1950s , which housed a large, palatial building, the House of Bricks , a two-story corridor house with traces of fire from the 22nd century BC. Has. The rotunda and apsidal houses from the Early Helladic II were also found in Tiryns. Helika in Achaia was a central place . His contacts reached from the Peloponnese to Anatolia, perhaps even to the Middle East. Pelopeion in Elis on the north-western Peloponnese represents a large tumulus from the Early Helladic II. Akovitika in Messenia, also part of the extensive exchange network of the Early Helladic II, contained corridor houses, similar to those in Lerna. In Laconia , small-scale trading networks for ceramics can also be found, which speaks for greater specialization.

Crete in the Early Bronze Age

The Early Bronze Age corresponds to the Early Minoan Period in Crete. There, the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age is considered to be the birth of the Minoan culture . Here too, external immigration from the east was assumed to be the impetus. The second transition phase, that of the Middle Bronze Age, i.e. the Middle Minoan Age, is considered to be the time of the beginning Cretan high culture. Now the famous palaces appeared, which were regarded as the central seats of an administration similar to the state.

In the meantime there is a tendency to recognize that certain central access points such as Petras Kephala, which handled the exchange with the Aegean region and thus acquired exclusive access to goods and technologies, had advantages over them as early as the late Neolithic IV (3300-3100 / 3000 BC) the hinterland. The settlement of marginal land, such as the Sitia plateau , began as early as the late Neolithic.

Krzysztof Nowicki, on the other hand, is more likely to assume that the fortified settlements on the mountain ranges will have recognizable security problems and an abrupt and extensive immigration from the east in the second half of the fourth millennium. The population collapse in the Dodecanese may indicate that at least some of these groups have migrated to Crete. Nowicki sees this migration as part of an east-west migration from Anatolia to the southern Aegean, which started earlier. On the basis of around 100 excavation sites from the transitional period on Crete, focal points can be identified on the Sitia peninsula, where the highest concentration of settlements can be found, and the south coast of the isthmus of Rethymno, plus smaller clusters up to the west coast between Palaiochora and Phalasarna . Almost all settlements can be found in easily defendable places in the coastal area. All of them were start-ups, the size of which varied between 2 or 3 and more than 20 households. Zakros Gorge Kato Kastellas measured 0.8 hectares, Xerokampos Kastri about 0.6-0.8 and Agia Irini Kastri 0.8-1.0 hectares. Many of the settlements were short-lived, but some, like Livari Katharades, that was extremely densely built up and heavily fortified, existed for a long time. These larger settlements of the Late Neolithic IV stand in clear contrast to the considerably smaller settlements of the Late Neolithic III. Apparently these newcomers expanded inland, first tangible in the Epano-Zakros basin, where they emerged again at easily defendable points on the edge of the basin and protected by walls. The largest concentration of such settlements for the transition period between the late Neolithic and the earliest Bronze Age was found on the Ziros plateau, then on the hills of Mesa Apidi and in Agia Triada . Two more clusters from this expansion phase were found on the Lamnoni plateau and between Palaio Mitato and Magasa . In some places tiny settlements were found, which often consisted of only one or very few houses. The most important settlement in Ierapetra of the late Neolithic and the earliest Bronze Age was Vainia Stavromenos, which extended over an area of 1.0 to 1.2 ha. In the west of the island the most important place was probably Palaiochora Nerovolakoi, which was similar in size, but it was soon abandoned.

Based on the ceramics, two different groups can be identified, namely around Phaistos and Katalimata on the one hand and Zakros Gorge Kato Kastellas and Palaiochora Nerovolakoi on the other. Nowicki assumes that the former goes back to the older Cretan population, while the latter is attributable to the immigrants. Apparently the immigrants first settled on offshore islands, such as on Gaidouronisi , which is 14 km south of Crete. On Koufonisi , 6 km off the coast, the population was found to be higher than the island could feed, so that it was possibly a first stop for immigrants. Both places were unpaved and lay on levels. Possibly habitable islands around Crete such as the Dionysades , Pseira , Dia and Gavdos played similar roles. On the Cyclades, in turn, settlements can be found, such as Agia Irini I or Paoura on Keos, which, like Kampos Komikias on the west coast of Naxos or Agios Ioannis Kastri on Astypalea , had similar characteristics to the Cretan settlements of this era. The same applies to settlements on Karpathos and Kasos . This restless time only ended in Crete with the significant changes at the end of the Early Bronze Age, so that the actual social upheaval here is probably not to be found on the border between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, but rather on the phase III and IV of the late Neolithic.

With the emergence of palace cultures, the focus has shifted further. The search for a steep social hierarchy and sudden change has been replaced in the last few decades. The focus is now less on the elites than on the question of the society behind them.

The earliest tangible stone vase industry that arose in Crete goes back to the early Minoic IIA. Apparently copper was melted in Petras Kephala , long daggers were made in Poros , and melting pots were found in Ayia Photia . In the early Minoan III, the specialized smelting site of Chrysokamino indicates an intensification of metal processing. Spatial segregation of the process steps could already indicate attempts to steer and control production, so that the "metal shock" of the Early Bronze Age II may have to be relocated to the Early Minoic I.

From the early Minoean IIB onwards, Cycladic imports in Knossos and Poros completely disappeared, while those from eastern Crete increased. Only in phase III and more in the Middle Minoic I did imports grow again. But obsidian and copper, both also from the Cyclades, continued to come to the big island, so the contacts probably continued. But the character of the exchange had changed. Contacts to Syria and Egypt existed during the early Minoican II and III, and their products were also copied. From phase III onwards, sailing ships appeared on Cretan seals. The emergence of elites with their representational compulsions possibly led to the more prestigious Eastern goods being of higher value than the Aegean ones, especially in the transition phase.

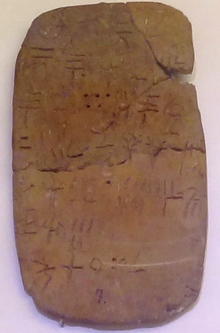

Seals appear on Crete around the same time as on the mainland, namely in the Early Minoean II. The oldest characters appear on seal stones of the Middle Minoic IA and B. Some fragments of a vase from Malia could even indicate the use of an equally undeciphered script as early as the Early Minoan III indicate. It is possible that their use is less related to economic motives, especially the palace administration as is often assumed, than to social and symbolic reasons. The addition of seals in graves could be an indication that they were used as an externally recognizable sign of social difference.

A sharp rise in temperatures in the northern hemisphere preceded the collapse of the palace centers, a sharp drop occurred during this phase. In the late Bronze Age, the temperature of the Mediterranean dropped, which reduced the entry of water into the atmosphere and, consequently, precipitation. As a result, the population centers, which depend on relatively high productivity, have been particularly hard hit by a decline in harvest. The so-called Dark Age coincided with a period of prolonged drought that extended into the Roman warm phase.

During the early Minoean II, the settlements grew rapidly and they developed urban structures. A further growth of these centers followed in the Early Minoan III up to the Middle Minoikum IA. In addition, a large number of smaller settlements emerged, which indicates an increase in agricultural production. The disadvantage that Knossos was exposed to in foreign trade, it compensated by the close ties with Poros, through which it found connection to long-distance trade. Political integration or domination of the surrounding area by Knossos, the most developed urban settlement, can only be assumed to be certain for the Middle Minoic IA. Although the large spaces for public rituals went back to the end of the Neolithic, the large terraces of the Early Minoan II provided space for the corresponding buildings. The so-called First Palace is likely to have arisen with such construction measures between the Early Minos III and Middle Minos IA and B. The same applies to Malia. In Phaistos the First Palace was built between the Middle Minoean IB and IIA, but the buildings also date back to the late Neolithic III – IV.

From the emergence of the first palace buildings around 1900 BC. Chr. Is often spoken of the first European high culture . Apparently the modern complexity of public spaces corresponded to the multifunctionality of Bronze Age sites; they were seen as places of remembrance, served for encounters between different social classes. Public spaces within necropolises (from 3000 BC) were a focus. Communal feasts were also part of the conduct of death cults there. In some urban settlements, public spaces were part of town planning from the start, perhaps first in Vasiliki in eastern Crete around 2700 BC. The so-called West Courtyards, which leaned against the palace facades as open spaces, were among the integral components of the urban squares. The local elites appropriated the spaces through the presence of architecture.

In keeping with the spirit of the times, the focus was on the assumption that these elites would rule politically. Knossos, Phaistos and Malia were considered centers under the barely verified assumption that they developed at the same time. All other palace finds were dismissed as secondary centers or as "exceptional". In addition, findings from linear B inscriptions that could be deciphered and that show that at least the center and the east of the island were actually administered from Knossos towards the end of the culture were projected back into the founding phase at the beginning of the 2nd millennium. This created a static image of the Minoan palace culture, which also suddenly appeared (and disappeared). New debates about methods and theories questioned this and opened the view to the developments in the period before about 1900 BC. And on the question of the early small-scale and fragility of political power structures. It seems recognized that the three main palaces dominated the island for the most part, with Knossos taking the lead towards the end of the culture. However, the deciphering of the Maya script showed that it is hardly possible to decipher political structures on the basis of archaeological traces. All assumptions about the political structure there were incorrect; the sources that have been accessible since the deciphering instead revealed a highly mobile, complex network of independent and quasi-independent, small to large cities and settlements linked to one another by alliances for a short period of time, based on inter-dynastic marriages and Conquest based. All of this left practically no archaeological traces.

Crete is considered to be one of the most archaeological areas of the Mediterranean. The models that make the political structure recognizable that deal with the settlement structure are most likely to come into question. A four-level model of hierarchization was preferred, which should provide the justification for speaking of a state. But even Athens in the classical period did not show such a hierarchy based on the archaeological finds, and so the model is hardly suitable for the small city-states of the Bronze Age to be expected. Surveys were mainly carried out around Phaistos, but in this question without a certain yield, and around Malia. In its area, on the edge of the Lassithi plain, there were buildings that could be identified as fortresses, and which probably represented a kind of border of the sphere of influence of Malia in the Middle Minoic. At the same time, however, these finds also raised doubts about a further dominance on the island.

Knossos is a different case. In the Middle Minoic IA the site already comprised 20, if not 40 hectares. More recent finds show that the area around Galatas possibly showed signs of fortification similar to those in the case of Malia, so that a southern border can be identified here (Middle Minoic III A). In any case, control of such an extensive, fertile surrounding area would have been much easier to gain than in the case of Malia, which would have had to overcome mountain ranges unusable for agricultural purposes in order to exercise control beyond these areas for a longer period of time. It is unclear whether the new palace in Malia only meant a stylistic orientation towards Knossos or an expansion of power in the larger city. Overall, the rule over Crete seems to have been much more fragmented, dynamic and complex than assumed since the beginning of palace research. Only in the case of Knossos, which was twice the size of the next largest centers, one can assume secondary centers, namely Archanes (about 12 km south of Heraklion), Tylissos, Poros, Amnisos (about 7 km east of Heraklion) and perhaps Vitsila.

The Cyclades in the Early Bronze Age

The cultural influence of the Cyclades , located in the middle between mainland Greece, Crete and Anatolia, was very pronounced in the early Bronze Age, as found in Liman Tepe in western Turkey, for example. The first settlement of this Cycladic culture that was excavated was Phylakopi on Melos, then followed by Ayia Irini on Kea (early Bronze Age in layers I to III), which is more known for the subsequent periods, which also applies to Akrotiri on Thira . The Early Bronze Age is only poorly represented, even if finds in Kastri on Syros or in Markiani on Amorgos , but above all the village of Skarkos on Ios , allow statements that go beyond the otherwise predominant burial sites.

Saliagos on Andiparos was the first to show that farmers and fishermen lived on the island in the Neolithic. They preferred barley over emmer and einkorn , sheep and goats already dominated domestic animal breeding at that time - spinning, perhaps weaving, was common. The violin-shaped female figurines already existed in an abstract form. The site gave its name to the Saliagos culture, which dates back to between 5000 and 4500 BC. Was dated. Maroulas on Kythnos is an even older Neolithic site. The type site for the late Neolithic, however, is Kephala on Kea. The discovery and excavation of Strofilas on Andros , the oldest fortified settlement in the Cyclades, has significantly changed our view of the era. Rock carvings from long ships, as they were only known from the Keros-Syros culture a thousand years later, contributed significantly to this.

Similar to the rest of the Aegean region, the early Bronze Age Cycladic culture is divided into three phases, although not every phase is proven on all islands. The early Cycladic Grotta-Pelos culture (according to Colin Renfrew, approx. 3400 to 3000 BC) represents the first phase, but it already began in the Neolithic. It is best known from crate graves. The dark ceramic is often decorated with herringbone patterns. Obsidian blades and marble vessels were also found. The figurines are rather schematic, with two types being distinguished, namely the Louros type and the Plastiras type. The latter is more detailed and the arms meet in the hip area, the former usually only consists of a prominent head and legs.

The Kampos group (approx. 3000 to 2800 BC) is named after the cemetery of Kampos on Paros . It already belongs to the transition phase between Sections I and II of the Early Bronze Age. Important sites are Agrilia on Pano Koufonisi and Markiani on Amorgos. The contacts between the southern Cyclades and some coastal towns of Crete were so intense that it is assumed that settlers migrated to the large island in the south.

The Keros-Syros culture (2800 to 2300 BC) already belongs to the Early Bronze Age Cycladic II. Chalandriani on Syros, a settlement and a cemetery, as well as Kavos on Keros , where the dead were ritually deposited (and the settlement on the nearby Daskalio ), gave the culture its name. It is also represented by various cemeteries on Naxos and Amorgos. The radiance and dynamism of the culture increased enormously, highly developed ceramics and found objects up to the figurines with crossed arms were characteristic. Copper now appeared in many ways, as a dagger or as jewelry. The contacts reached as far as Liman Tepe and Troy in Western Anatolia and as far as the Peloponnese. There was talk of an "international spirit" of the Cycladic culture of this time.

The Kastri group (approx. 2500–2200 BC, Early Cycladic II – III), named after the fortified settlement Kastri on Syros, finds its artifacts in Lefkandi on Evia , in Markiani and Ayia Irini. In addition, Korfari ton Amygdalion or Panormos on Naxos with an area of 500 m². Many cultural elements point to Anatolian origins, numerous settlements were now fortified. Tin bronze increasingly replaced the arsenic bronze that had dominated the Cyclades until then .

The Phylakopi-I culture (Early Cycladic III, 2200 to 1900 BC) is best represented in the eponymous Phylakopi and in Parikia on Paros. While the size of Phylakopi increased, that of Melos decreased drastically. There may have been a gap between this and the previous phases, but this could also be due to missing findings.

Overall, the Keros-Syros culture shows signs of prosperity; the population also exceeded that of the Grotta Pelos culture. Wine and olives increasingly supplanted the cultivation of cereals, and there were increasing signs of ceremonies and celebrations involving wine consumption. Chalandriani-Kastri, Ayia Irini, Grotta-Aplomata and Dhaskalio-Kavos were proposed as the four most important communication centers, because they stood out for their population and differentiated production, but were also characterized by increased consumption of prestigious goods and the most intensive integration into maritime trade - one speaks of an Anatolian trade network into which the Kastri group was increasingly integrated, but which was soon dissolved.

Western Anatolia and the Eastern Aegean in the Early Bronze Age

There were close contacts between Western Anatolia and the islands of the Eastern Aegean. However, while in the Troas at the transition from Troy I to Troy II a decline in the number of villages can be proven, which may be due to a population concentration, only two settlement centers in the east and on the Gulf of Kalloni can be proven for Lesbos . This is not surprising since the west of the mountainous island is extremely barren. In the hinterland there were few and small farmsteads or settlements such as Angourelia Sarakinas, Saliakas and Prophitis Ilias. Some settlements such as the at least 4 hectare large Kourtir on the Gulf of Kalloni existed for a long time, otherwise no statement can be made about the durability of the settlements.

The situation is similar on Limnos , where the majority of the settlements, which were also more complex, existed on the coast, while the hinterland was only sparsely populated. There, as on Lesbos, hill settlements such as Progomylos or Neftina arose. Defense and observation aspects may have played a crucial role in choosing these otherwise inconvenient locations. Plati-Mistegnon on Lesbos overlooks the eastern strait from a 100 m high cliff, while Saliakas controls the only land connection between the southeast coast and the inland on the Gulf of Kalloni.

For Imbros and Chios , no statements can be made about increasing settlement concentration. During the Early Bronze Age II, some settlements, such as the lesbian Thermi, grew considerably and are likely to have doubled their population, even if they lagged far behind the concentration process on the Anatolian mainland.

Middle Bronze Age (2100–1700 / 1600 BC)

Mainland Greece in the Middle Bronze Age

For a long time, the mainland received little attention with regard to the Middle Helladic. This had to do with the fact that the time before and after was much better studied, and that the mainland faded alongside the Aegean Sea and the palace culture of Crete. Research also focused on typological sequences and the origins of the Middle Helladic cultures. However, recent research has shown that the cultures on the mainland were neither static nor uniform, isolated nor backward.

The beginning of the Middle Bronze Age is around 2100 BC. Or a little earlier. The end of this era is traditionally around 1600 BC. A different chronology is followed more likely around 1700 BC, which is also supported by more recent radiocarbon dates (see also Minoan eruption on the problem ). If one concentrates more on social processes, on the other hand, it makes more sense to combine the time between Early Helladic III and Middle Helladic II and the Middle Helladic III with the Late Helladic I.

Numerous pieces of evidence show a strong decline in population and destruction at the transition from Early Helladic II to III and during the latter epoch, the causes of which, however, are still being discussed. In the process, the settlement structures, burial customs and material culture changed. Whereas in the past only population movements and invasions were blamed for this, today other changes are increasingly brought into play, such as soil degradation or erosion, which may have changed societies significantly. They appear to have occurred in connection with migration, whether as a cause or consequence. At the same time, the effects in the various regions were very different.

While Middle Helladic I and II were considered to be rather static for a long time, finds in Lerna showed that the house structures underwent significant changes in the earlier phase, which perhaps resulted in a more pronounced accumulation of wealth. In the later the funeral customs changed. These approaches seem to have disappeared again, while the changes at the end of the Middle Bronze Age proved irreversible. The extreme expansion of long-distance trade is well known - a gold-studded seal of an official from the time of Pharaoh Djedkare (around 2400 BC) indicates trade relations with Egypt. At the same time, the mainland cultural region took on much more Aegean and Minoan influences.

Only a few of the settlements were fortified, such as Kolonna, while the walls of Malthi are more likely to be attributed to the Mycenaean culture. The buildings were relatively uniform, free-standing and distributed irregularly in the area of the respective settlement. Mostly they consisted of two rooms and rarely exceeded a total area of 50 to 60 m². Mud brick structures rose on stone foundations. The differences were rather small in the early phase, but increased significantly later. Some of the Middle Helladic III houses in Asine were four times the size of the average house of the era, more complex, and stood along a path so that they were similarly oriented. Kolonna was an exceptional case: It was heavily fortified, the house structures were complex and a monumental building structure was built in the Middle Helladic I. The city looked more like the places in the Aegean.

The burials between the Early Helladic I and the Middle Helladic II took place within the walls; some of the dead, mostly children, were still buried under the houses. Many graves were laid in destroyed houses. Burial sites outside of the settlements were probably widespread outside the settlements by the Middle Helladic II at the latest; Burial mounds were built, but their distribution is uneven. Simple pits, boxes of all kinds, plus large pithoi or jugs exclusively for children were common. Usually the dead were buried individually, contractually, multiple graves are rare. Grave goods, such as vases or pearls, are seldom and hardly intended to make an impression. Exceptions are the grave mounds of Aphidna and Kastrulia or the grave structure in Kolonna. In the epoch after the Middle Helladic II to the Late Helladic I, cemeteries outside the walls were built much more frequently, graves were also used several times - Tholos and shaft graves are better suited for this - and the bodies of the dead were subjected to renewed treatment. Although the grave goods became richer, they were not remotely close to the furnishings in Mycenae.

There was no trace of places of worship, and even figurines like those of Eleusis are rare. The religious practice can only be grasped by means of rites in connection with the graves. Only in Apollon Maleatas near Epidauros - created at the end of the Middle Helladic - can a shrine be recognized, whose votive offerings, however, only come from the Late Helladic. At least there was a pit on the neighboring Kynortion hill in which the remains of ceremonial acts were found mixed with animal bones in the middle of a settlement that had already been abandoned in the Early Helladic. The fact that the settlement was never built on again could indicate a sanctification of the site.

Material culture showed some innovations, such as tumuli , but these did not appear at the same time. Ceramics were also considered to be conservative and simple, but each site has different proportions of a local nature, which is reflected in stylistic differences, as well as different proportions of imported goods or local imitations. Advances in ceramics can only be seen in Boeotia. On the other hand, the pottery from Aegina was imitated in Thessaly, but by no means in Boeotia. The tools remained unchanged for a long time. It has recently been shown that copper metallurgy has been replaced by bronze metallurgy, and that the potter's wheel has been adopted. At the end of the epoch there was a greater openness to external influences, there was a diversification of ceramic styles, a drastic increase in figuration and a sharp increase in imports.

But even in the early Middle Helladic I there were intensified contacts between the east coast towns and Aegina, the Aegean islands and Crete. Pottery from Aegina was more common near the island than in the hinterland, but in some cases it reached Anatolia and Italy. Boeotic pottery was exported to the south, and a Thessalian trade network spanned the northern Aegean. Imports were concentrated in Lerna and Argos. The lion's share of the mainland copper came from the Aegean Sea, which also supplied all of the lead. Small amounts of copper came from Thrace or from Cyprus . There were also contacts to Epiros, the Balkans and Italy.

Kinship was also the central element of social organization. As a result, questions of status and prestige, but above all questions of authority, shifted to the families and less had to be expressed at the overall social level of a settlement. Age and gender remained central. The causes of the changes can apparently not only be traced back to changes in the economy, such as the need to control raw materials. Nevertheless, the extensive trading networks, in which it was important to influence foreign leadership groups in one's own interest, may have played an important role. The expansionist aspirations of the Minoan palace culture and the competition or prestige of the trading centers are also likely to have been of great importance. This offered not only influential roles in society, but also only a few roles, especially in the "diplomatic" area. Against this background, the slow development towards the Mycenaean culture could turn out to be a coup for individual groups. But to be able to make a statement here, the knowledge about the roles of individuals, social groups and communities in this expanding world is still too unclear.

Crete in the Middle Bronze Age

The emergence of the first great or ancient palace is commonly referred to as the central event on the Middle Bronze Age island that borders the southern Aegean Sea. It is assumed that this happened in the Middle Minoic IB, which in calendar terms was 1925/1900 BC. Is reproduced.

The main locations included Knossos and Phaistos , Malia and Petras east of Sitia, whereby this monumentalization represented a rather slowly progressing process, while Phaistos and Malia immediately erected monumental structures following extensive leveling work. Elsewhere, palace buildings were built either in the Middle Minoikum IIA, as in Petras or Monastiraki, in the Middle Minoikum IIB, as in Kommos, or only in the Middle Minoikum IIIA, as in Galatas. In some places these buildings were not built until the new palace period, such as in Gournia, Zakros or Phaistos. The more recent finds in Sissi (at least the New Palace period) or Protoria-Damatri in the eastern Messara, from Chania and Archanes or Zominthos suggest that even more sites of this type will appear. It can now be assumed that the palace buildings varied from the simplest to the most highly developed complexes. Whether the monumentalization especially towards the end of the 20th century BC BC, which goes back to oriental influences, is still being discussed, but a “palace package” analogous to the Neolithic can hardly be spoken of.

The palace of Knossos comprised a built-up area of 21,000 m² on a clear area of 2.2 hectares. It was built around a rectangular central courtyard measuring 53 × 28 m. Angled, narrow corridors, richly decorated corridors, painted halls, elaborately designed staircases and pillared galleries approach this courtyard from four directions.

The idea of a kingdom and many other ideas go back to the excavator Arthur Evans . He interpreted the complex as the residences of priest-kings, whereby he was clearly inspired by oriental models. However, some of their structural patterns, such as the orientation, large courtyards, wing structures, point more towards the early Minoic IIB. After the Linear-B script was deciphered in 1952, the economic aspect was given a much larger place. Soon people believed in a highly efficient administration that registered and controlled every movement, be it human or goods. A strong connection to an agricultural hinterland from the 1970s was emphasized, along with the idea of an administration in a hierarchical society.

Such ideas of a central economic focus and transshipment point under the control of a comprehensive priest-royal leadership, possibly all over Crete, seem, if at all, to apply at best to the central economic transshipment point and more to the late Minoic II-III than to the earlier phases . The role as a distribution center (to dependent personnel) was also ultimately questioned. The question arose whether the presumed control in religious, economic and political terms did not imply a modern conception of the state. Even if this were the case, the transition was evidently less drastic than expected. In addition, the economic role of the koulourai , stone, circular pits, which apparently served to store grain, was questioned, as was the idea of a trade in luxury goods driven by the needs of the presumed elite. The Kamaresware, named after the Middle Cretan town of Kamares and usually attributed to palace workshops, cannot be linked to the idea of control by the palace. On the contrary, a considerable part of this high-quality ceramic was produced in southern central Crete and exported to Egypt, for example to Avaris . In the meantime, Knossos appears less as a producer than as a consumer in literature. Even the imagined complete control over distribution contradicts the fact that not even the more advanced state structures of the Middle East were able to do so, on which this idea was based. On the other hand, it turned out that part of the production actually took place in the palaces.

The recognition of the four main sites as “palaces” is also rather arbitrary, because the monumental complexes of Kommos , Monastiraki or Archanes are not counted among them, not to mention recent finds. In addition to hasty ideas about the state and adherence to a certain epoch, there is often the idea that the said palaces must be of the same shape, so a homogeneity across all cultural differences in Crete was assumed. In order to counteract the misleading associations that the term “palace” carries with it, people increasingly spoke of courtyard-centered buildings, but also of courtyard buildings or complexes. Finally, it is doubted that priesthood and rule were to be found under one roof, because this type of rule cannot be proven anywhere, especially not in the Middle East, where there was always a double structure. In addition, the palaces are not suitable for the reconstruction of the entire Minoan society, as was long assumed.

The evidence for a palace's own production is rather small in number and also very uncertain. In addition, similar products were made elsewhere, such as textile production, which certainly took place in Knossos. Grains, figs or olives on clay tablets could be indications of production in the vicinity of the temple. In any case, the tablets themselves were stored on a large scale in Knossos.

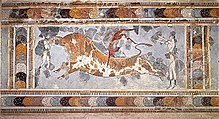

There drinking vessels were perhaps stacked on a large scale to distribute drinks, because their number far exceeds the number of vessels that were used for storage purposes. A workshop in the Mesara supplied both Phaistos and Knossos with high-quality ceramics. On the other hand, some of these elaborate goods were brought about by Pediada in the Middle Minoikum I. In Phaistos, enormous amounts of ceramics were found in the south part of the west wing, which alone represent about a quarter of the total stock. They probably served extensive rituals with numerous participants to whom drinks were served. In doing so, one thinks about the religious forms that may have been more shamanistic and based more on direct experience, which may have included trance , state changes and ecstasy, which may have been better suited to the performative nature for which the large places were suitable.

The writing and seal were also ascribed to the time the palaces were built as centers of rulership and religion, as was long believed. At that time, however, the use of writing already existed, even if it found an improvement and a wider spread. The seal shapes have also become more differentiated. The collections of clay tablets in Knossos, called “archives”, probably originate from the Middle Minoic II, but more likely from III. The largest “archive” has so far been found in the Mu quarter in Malia. Some of the ceramic workshops also used the script; in Knossos seals were found in the production rubble.