Landwehr

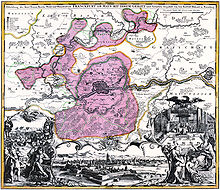

(copper engraving by Johann Baptist Homann , area boundaries corrected after Friedrich Bothe )

With Landwehr , Landgraben and country Hege be border marker - or border security stations and enclosures of residential areas with the right of containment or entire territories referred. These settlement protection systems are mostly dated to the High and Late Middle Ages and in individual cases have lengths of over a hundred kilometers. However, comparable earthworks have been mentioned since ancient times. The Roman Limes is the best known version of an early Landwehr. The Danewerk also belongs to this group of barriers.

In some regions, especially in forest areas, these land forces are still preserved and are often protected as soil monuments.

The construction of a Landwehr was an effective measure to protect the population of a settlement area or territory against attacks by neighbors or enemies in feuds or wars and to delimit a legal district. The Landwehr were a means of limiting the probability, the chances of success, the effectiveness and the consequences of medieval warfare and thus preventing them. They also prevented gangs of robbers from entering the area and made it difficult to retreat after raids. The combination of Gebück and Dörn was also well suited for enclosing cattle pastures and as a guideline for hunting and wolf hunting. Wolfskuhlen are often found along their course.

Landwehr was also a large-scale enclosure of forest and agricultural areas to protect the local population, who settled on distributed residential areas and farms within the protected area. The Landwehr gave the rural population protection similar to that of the population in fortified cities through the city wall. But the fields of many cities and their surrounding outer areas were often also given a ring-shaped landwehr-like enclosure, a so-called Stadtlandwehr, Stadthagen or Stadthege. One example of this is the Westphalian city of Dortmund, which, in addition to the city wall around the city center, also had an extensive landwehr surrounding it. The Stone Tower was how busy a map from 1748, as part of this waiting Landwehr ring.

There were only passages through the Landwehr on thoroughfares, where goods and person controls were carried out analogous to the gates in a city wall . Landwehr also served as an effective customs border, whereby in the case of roadblocks executed as landwehr within territories, customs mainly mean a road toll .

Also were trade routes , particularly in the area of control bodies, accompanied by both sides Landwehr. In addition to protecting against raids, these accompanying land forces primarily served to channel the traffic flows and effectively prevented people from bypassing or bypassing the control and customs posts.

history

Early and early times

Hedges are one of the most natural forms of border fortification and fencing. Their simplest and most common application to this day is the garden hedge .

To protect storage areas (in caves), fixed dwellings, houses, property and settlements from attack by predators or enemies, the people of the already used antiquity and in the early history of backups in the form of fences from branches and brambles. This is still common today among nomadic tribes. Gaius Iulius Caesar reports z. B. from dense " Hagen ", which were created by the " Nerviern " in today's Belgium:

“To avert the predatory incursions of their neighbors' cavalry, they had put hedges everywhere. At the end they cut young trees so that they planted young branches on the sides and then planted thorn bushes between them. So these hedges literally formed thick walls, which not only made it impossible to pass through, but also made it impossible to see through. "

A shape with walls and ditches is more elaborate. In the year 16 Tacitus reported about a border guard of the Angrivarians , the Angrivarian Wall , which was built to protect against the Cheruscans . The most important border weir is said to have been near Rehburg-Loccum .

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles speak of a Bebbanburg that was "first fortified by a hedge around 547 ...". The capitularies of Charlemagne also mention “ramparts planted with hedges” .

In England , comparable systems are called "Dyke" (dike) or "Ditch" (ditch), for example the Bokerley Dyke , which was built around the year 360 and dates back to 300 BC. Chr. Dated Grim's Ditch passes or 270 km long Offa's Dyke .

The existence of “hagediks”, walls planted with hedges, has been handed down among the Normans.

Middle Ages and Modern Times

Medieval land defense usually consisted of one or more impenetrable strips of wood of intertwined hornbeams - (the " Gebück ") with underplanted thorny bushes such as blackthorn , hawthorn , hedge rose , blackberries or Ilex - (the "drenched")

In addition, there was usually a combination of one or more of the following elements:

- one or more parallel earth walls, between or on which the wood was planted

- a path to care for the hedge and for patrol rides along the Landwehr

- Trenches in front of, between and behind the earth walls, which, depending on the location (valley), were sometimes filled with water. The wall was usually created from the excavation of the trenches.

- Waiting towers , jumps , barriers and reels at street passages, so-called blows (customs clearance)

- a "wet border" from floods and moats

After the Frankish conquest until the late Middle Ages arose with the formation of solid dominions territorial militia, the individual legal areas fenced . Gaue , Zenten , judicial districts , often congruent with parishes , offices and entire domains ( territories ) were surrounded by land forces in the form of hedges (Heegen), bridges and thorns.

Then there were Landhagen and Stadthagen , which were arranged in a ring around smaller settlement areas. The "Landhegen" limited and protected both entire areas and the surrounding area of cities, for example the almost 70 km long Aachener Landgraben the former Aachen Empire , similar to Frankfurt (Main) , Rothenburg ob der Tauber , Lübeck or Mühlhausen / Thuringia . The traces of the Rothenburger Landhege are still around 60 km long today, the Mühlhausen Landgraben , still around 26 km long today, is reminiscent of the border between Mühlhausen and Eichsfeld . The Middle Hessian Landheegen formed the border between the Landgraviate of Hesse and the County of Nassau ; the outdoor enclosure was 29 kilometers long and the indoor enclosure 16 kilometers.

These earthworks bundled various functions. They delimited, reinforced and pacified “areas” that were under their Greven , Count or bailiff . This bundling of tasks for the protection of armed land areas ( Landwehr ) sounds as the cherishing in terms such as Hege or Heege, Hag and Haag or also "hedge", but at the same time also in the term protective hedge. Numerous toponyms such as Zarge , Gebück , Wehrholz or Gehag are reminiscent of the different designs as hedges, trenches or staggered construction methods.

The primary goal of the barriers was to protect the rural population and the respective area against foreign claims to rule and military or predatory attacks. Landwehr was a clear border marking and at the same time, when they marked the outer border to another area of rule, also a customs border. Even within a territory there were sometimes landweists, which delimited the individual offices from one another, including streams and other natural obstacles. These "internal" land forces, so-called intermediate land forces, were usually not as complex as those on the external borders.

A special variant in Switzerland was the so-called Letzi , where it was often enough to secure only the valley entrances accordingly. Many of the battles between the Old Confederation and the Habsburgs took place on such Letzi, for example the Battle of Morgarten , the Battle of Näfels and the Battle of the Stoss .

Some Landwehr also had a function as an advanced defense of fortresses . They were created with the character of a field fortification as the first approach protection. From a military point of view, up to modern times, in the form of Spanish horsemen, they had the purpose of forcing the attacker of a fortress to take measures to besiege a fortress even further ahead . Their modern successors include the barbed wire fencing , which was used in both world wars.

The course of many simple Landwehr shows, according to new research results, that they were completely unsuitable for defense purposes in many places. From this it can be concluded that some systems were mainly used for border marking and customs collection. Nevertheless, they restricted the free movement of enemy troops, so that they also had a military use, albeit limited. For example, the city of Hagen protected by Warendorf in the Thirty Years' War successfully before besiegers: This penetrated although occasionally into the city, but did not dare massive attack - simply because of the danger, not with a counter-attack quickly enough through the narrow gap in the militia to retreat compete to be able to.

As a border fortification of certain legal districts, land forces were broken through in some places by arterial or trade roads. These breakthroughs (called blows) were secured by means of simple barriers, by additional staggered routes (so-called loops) or - apart from at national borders also at some urban land forces - by building towers ( waiting rooms, wigh houses or land towers). Customs stations were usually located at the crossings. The lucrative customs law (often in connection with the jug law ) could be acquired by local farmers.

Executions

Landguards mostly consisted of a simple ditch, in the plain as a land ditch or water ditch as an obstacle, behind which there was an earth wall created from the trench excavation. Behind it stood the actual main border obstacle, a 20 to 50 meter wide, dense, interwoven strip of wood. In the mountains, the course has been adapted to the natural conditions such as rocks, steep slopes and watercourses, etc. A second trench was often dug ten to thirty meters apart.

The strip of wood and the walls were overgrown with a hedge made of hornbeams , which were cut to man's height and whose branches were kinked, intertwined with the other branches and stuck in the ground to be knocked out again. This gave rise to the so-called bridle . Dog roses, hawthorn , black thorn or blackberries were used as undergrowth so that the hedge was impenetrable . This is where the name "Gedörn" comes from in some places. The system was also kept free from higher vegetation. Most of the apron was cleared.

Father Hermann Bär from the Eberbach Monastery in 1790 describes how a weir hedge was created as follows:

“The establishment was made in the following way. The trees in this district were thrown (cut) at different heights, recently knocked down and the branches that were shot out were bent down (bend-stoop). These grew in the direction given to them, woven tightly into one another, and as a result produced such a thick and intricate wilderness that was impenetrable to humans and horses. "

With regular care and "care", an almost impenetrable strip of wood was created over the course of a decade. More elaborate land forces with a defensive function consisted of several parallel trenches and excavated walls with plants. Double trenches in particular were intended to prevent riders from jumping over them. Further versions were the so-called weir hedge ( kink ), for the maintenance of which the kink money was collected.

In Hesse at the end of the 17th century, many villages had fortifications on important roads or in border locations, regardless of the well-fortified churches, as the Hessian chronicler Johann Just Winkelmann mentioned in 1697. He writes:

"Today almost most of the large towns and villages in Hesse are surrounded by a ditch and a throw-up / so that they can defend themselves against minor parties."

The fortifications could consist of fences (called Etter or Dorfetter), hedges (grove fortifications ), ramparts and ditches (drier like moats) and gates.

Another, temporary artificial obstacle to be erected relatively quickly in the event of a defense and to close gaps in a landwehr in a suitable manner was the entanglement . It was also placed as the first obstacle to approach castles, city walls, entrenchments and military camps and was built from felled and cut - "beaten" - trees, bushes and thorns. Occasionally the new installation of a Landwehr was secured with a beating until it was functional. Since a lock was made of dead wood, it was relatively easy to remove by burning it after it had dried out.

Guard system and transit stations

Important roads that led through the Landwehr were secured with so-called defenses ( barriers ) and other reinforcements such as guard towers . The road toll that was due to the sovereign was taken from the blows. At some nationally important stations there were restaurants . The Kruger had to keep food and drink ready for those passing through. They also performed sovereign functions by watching the apron of the city and keeping the barriers closed at night .

In many cases, the streets were provided with trench-wall-trench systems on both sides so that no one could get into the villages outside the intended route. Often wooden bridges led across the trenches, so that in the event of war the road could be blocked by removing the bridge.

Messages about approaching enemy troops or visitors were forwarded along the land forces and to the hinterland via waiting towers (for example in the Münsterland ). In the mountains, this was also done by “waiting” at elevated vantage points from which one could see far into the surrounding area. When enemies approached, optical signals were given in the form of smoke signals, flags, mirrors, torches, or signal horns and church bells . The entire population of the villages and neighboring villages was obliged to obey these emergency signals or the striking of the storm bell, but also in other emergencies such as fire or flood, regardless of what other work or activity was pending. This striking of the bell was called, for example, the "rumor" in the Münsterland.

entertainment

To build all subjects were the territorial ruler used ( forced labor ) who was largely the weir wood / Heege. All residents also had to take care of the care. Some Heegen / Landwehren even built and maintained the neighboring rulers together, for example in Central Hesse the Landheege on the Hörre between the County of Nassau on the one hand and the Landgraviate of Hesse and the County of Solms on the other.

The construction and maintenance of the land forces were designed for the long term. It took up to ten years for an impenetrable hedge to form, even with constant and time-consuming care ("care and maintenance"). Even after that, the trenches and the Hählweg , a control path along the Landwehr, had to be freed of vegetation and kept functional. As a result, many land forces were neglected or not even completed in the long peacetime for reasons of cost.

Intentional damage to a Landwehr was punished with severe penalties. In the case of the more than 100-kilometer-long Westphalian Landwehr in the Teutoburg Forest , the scope of punishment ranged from amputation of the right hand to the death penalty. But also crossing the Landwehr in places not intended for this purpose was punished in many places. At the Rhön Landwehr, fines of up to five guilders are charged for crossing the bridle or entering the Hählweg .

The border fortifications were repeatedly renewed and maintained until the 18th century and reinforced as fortifications in the event of external threats.

The obligation to defend the earthworks, which had been razed under Napoléon but were still functional, became part of the general duty of the military association of the Prussian Landwehr (not to be confused with the structure) in Prussia in 1813 . In many cases the fortifications of the Landwehr were abandoned and leveled and the wood was charred to charcoal after the end of an armed conflict or after the abolition of an administrative district.

Landwehr as ground monuments

Due to the expanding construction activity around cities, the former land defense services were mostly leveled. In uninterrupted forest areas , however, the fortifications could be preserved for centuries. They can also be found as wall hedges in the open countryside, sometimes several kilometers long. The remnants of the military forces are now mostly protected as land and cultural monuments .

The community of Niederkrüchten in North Rhine-Westphalia wrote in support of the entry of the Landwehr Varbrook into the list of monuments of the community of Niederkrüchten as a ground monument in 1997:

“In the Viersen area and its immediate vicinity there was a system of various border and property fortifications. The Landwehr was first mentioned in a document in 1359. The large territorial defense was built in the 15th century as the border between Geldern and Jülich. Landweirs are obstacles that consist of one or more parallel walls, which are accompanied inside and outside by ditches and which were originally designed to delimit larger parts of the landscape and were originally many kilometers long. The embankment-like embankments reach a height of 2 to 3 m, while the depth of the trenches is about 1–1.5 m. The surviving land defenses are usually so heavily sanded that the characteristic trench profiles only become apparent as soil discoloration through archaeological investigations. Landguards were established in the late Middle Ages and early modern times in the immediate area of city, parish, court or territorial boundaries and were used until the 17th century. With such barriers, which were additionally secured by impenetrable hornbeam and hawthorn hedges on the crest of the ramparts, traffic was forced to pass the customs posts at the passages. In addition to these dominant fiscal reasons, their task was also to restrict the mobility of enemy associations. The Landwehr near Niederkrüchten impressively document the political, economic and cultural conditions in the Middle Ages and are indispensable evidence of human history in the Rhineland. They should primarily be seen as a monument to the preservation of peace, the intensification of which is one of the main features of the late medieval-early modern territorial state. They therefore represent important land documents in the history of the region, because their research serves to supplement and clarify archival documents and historical evidence. "

Hallway names as hints

When investigating the course of a medieval Landwehr, research can also use the place, street and field names that have survived to this day. A number of place names are an indication of a nearby Landwehr and its functional components.

These names include Landwehr, Schlagbaum, Landgraben, Hähl and Zollhaus . Place-name components with -hau indicate a lock, those with thorn (s) / Dörn (en) indicate a thorn hedge. Schneis stands for limiting swath, reel for turnstile-like persons passages, hard or Hardt / Haart for border forests, waiting for a watch tower and Schanz (e), Schlipp (e), deglutition (e) or shock for a strongly fortified passage.

Field names such as Grengel, Knick / Gnick, Koppelbirken, Krausenstuken, Lanfer, Lanter, Hecke, Heg, Heege, Haag, Hag, Hain, Han, Hahn or Hagen also point to former land defense services. In popular parlance, the routes of the routes are sometimes referred to as towing paths, discharge paths, dead paths or country roads.

Selection of military forces

Designation "Landwehr" or "Lanwehr"

- Landwehr of the former rule of Ahaus

- Anklamer Landwehr

- Bachgauer Landwehr

- Baroper Landwehr in Hombruch

- Bergische Landwehr in the Duchy of Berg

- Berlin Landwehr Canal

- Brunswick Landwehr

- Bückethaler Landwehr near Bad Nenndorf

- Dahler Landwehr in Mönchengladbach from Engelsholt via Ohler to Dahl

- Landwehr Dinslaken with remains in Dinslaken, Voerde and Hünxe

- Einbecker Landwehr

- Isern Purt (High German Iron Gate) , Landhemme, Landwehr south of Penzlin am Wedensee

- Frankfurter Landwehr

- Grebensteiner Landwehr near Grebenstein in the Kassel district

- Landwehr in Hamburg

- Hannoversche Landwehr in Hanover's city forest Eilenriede

- Hartwarder Landwehr

- Landwehr Himmelpforten near Soest

- Helmstedter Landwehr in the Lappwald

- Kasteler Landwehr (Kastel, also called Mainzer Landwehr), see under buildings

- Lambertsgraben near Creuzburg

- Landwehr Varbrook in Niederkrüchten-Varbrook (Viersen district)

- the Long Landwehr near Schmalkalden

- Speyer Landwehr with the Speyer watch tower , where there is also a Landwehrstrasse

- Landwehr on the southern edge of Neubrandenburg

- Lüneburg Landwehr

- North and East Landwehr near Dülmen

- Parchimer Landwehr near Parchim

- Saxon Landwehr in southern Thuringia

- Schaumburger Landwehr , north of Stadthagen

- Würzburger Hähl in the Thuringian Rhön

- Outer Landwehr of Würzburg

- Tilbecker Landwehr in the Baumberge

- Viersener Landwehr near Mönchengladbach-Großheide

- Landwehr on the northern edge of Calvörde

- other land defense in Barme , Ganderkesee , Hemmerde , Landgraaf , Leingarten , Lübeck , Nazza , Nettlingen , Rhön , Tönisvorst , Wetzlar , Werne .

Designation "Landgraben", "Landgraaf" and "Graben"

- Large ditch near Klempenow and Boldekow in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

- Small ditch near Altentreptow in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

- Landgraben on the northern border of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Mühlhäuser Landgraben in Thuringia

- Quedlinburger Landgraben near Quedlinburg

- Lübeck Landgraben in a large area around Lübeck

- Württemberg Landgraben between Beilstein and Heuchelberger Warte

- Aachener Landgraben extensive around Aachen

- various military forces in the duchy of Münster (for Ahlen , Beckum , Bocholt , Borken , Coesfeld , Dülmen , Haltern , Münster , Rheine , Telgte , Vreden , Warendorf and Werne )

- other country forces in Adelwitz , Bickenriede , Casekow , Glenne , Japenzin , Landgraaf , Lengefeld , Löwitz , Lüdersdorf , Pöndorf , Rednitz , Sachsendorf (Barby) , Stockelsdorf , Striesen , Wadersloh and on the river Oos

- Dreigräben near Sprottau , Sprottischwaldau in Lower Silesia

Designations "Hecke", "Heg", "Haag", "Hag", "Hagen", "Landheege", "Gedörn" and "Gebück"

For the special meaning of Häger in Lower Saxony, see: Adelung

- the Cologne hedge near Siegen

- the Rothenburger Landhege near Rothenburg ob der Tauber , see also Lichteler Landturm

- the Central Hessian Landheegen

- the Haller Landheeg near Schwäbisch Hall

- the Rheingau Gebück near Walluf and Eltville on the Rhine

- the Bechtheimer Gebück near Bad Camberg

Nameless

- Barriers at Springe in Deisterpforte

Border walls in England, Scotland, Denmark and Northern Germany, Poland

literature

- Werner Dobelmann : Landwehr in the Osnabrücker Nordland. In: Heimat yesterday and today. Communications from the Bersenbrück District Home Federation. Volume 16, 1969, pp. 129-180.

- Wilhelm Engels : The Landwehr in the outskirts of the Duchy of Berg. In: Journal of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein . (ZBGV), 66th volume, year 1938, pp. 67-278.

- Johannes Everling: The Aachen Landgraben today after 500 years. Aachen 1973, OCLC 1069243331 .

- Norbert Klaus Fuchs: On the trail of the Saxon Landwehr. In: Das Heldburger Land - a historical travel guide. Rockstuhl Publishing House, Bad Langensalza 2013, ISBN 978-3-86777-349-2 .

- Oswald Gerhard: Eckenhagen and Denklingen through the ages. A home history of the former imperial court area Eckenhagen. Ed .: Heimatverein Eckenhagen e. V. Eckenhagen 1953 (with map).

- Peter Hartmann: The Lübeck Landwehr in the Middle Ages and early modern times. (= Annual publication of the Archaeological Society of the Hanseatic City of Lübeck eV special volume 1). Lübeck 2016, ISBN 978-3-7950-5236-2 .

- Albert K. Hömberg: The emergence of the Westphalian free counties as a problem of medieval German constitutional history. In: Westfälische Zeitschrift, magazine for patriotic history and antiquity. 101/102. Volume, Münster 1953, pp. 1–138.

- Cornelia Kneppe : The city police forces of the eastern Münsterland. (= Publications of the Antiquities Commission for Westphalia. 14). Münster 2004, ISBN 3-402-05039-0 .

- Cornelia Kneppe (ed.): Landwehren. On the appearance, function and distribution of late medieval fortifications . Aschendorff, Münster 2014, ISBN 978-3-402-15008-5 .

- Cornelia Kneppe: The Westphalian Landwehr system as a task of preserving monuments. In: Excavations and finds in Westphalia-Lippe. Volume 9, part C, Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, LWL-Archäologie für Westfalen, Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2580-0 , pp. 139–166.

- Thomas Küntzel: City and Border - The Landwehr of the Nienover urban desert in the context of southern Lower Saxony. In: Archaeologia historica. Volume 29, 2004, pp. 167-191.

- Thomas Küntzel: Green borders, thorny barriers: Landwehr in northern Germany in: Archaeological reports of the district of Rotenburg (Wümme) 15, 2009, pp. 209–243 ( online )

- Hans Mattern, Reinhard Wolf : Haller Landheg. Their course and their remains. (= Research from Württemberg Franconia. 35). Sigmaringen 1990, ISBN 3-7995-7635-5 .

- Tim Michalak: The Stadthagen. On the importance and function of the military forces at the borders of the imperial city field mark of Dortmund. In: Home Dortmund. 1/2002, pp. 12-15. ISSN 0932-9757

- Horst W. Müller: The central Hessian hills. In: Hinterland history sheets. Volume 89, No. 4, December 2010, Biedenkopf.

- Georg Müller: Landwehr in the community of Ganderkesee . Ganderkesee 1989.

- Andreas Reuschel: Hagenhufensiedlungen or “Hägerhufensiedlungen” in the Ithbörde? A contribution to the differentiation of a settlement-geographical term and phenomenon. Dissertation. Bonn 2009. ( hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de ( Memento from March 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive ))

- Heinrich Rüthing: Landwehr and waiting in the Paderborn and Corveyer Land. In: Local history publication series of the Volksbank Paderborn. 33/2002.

- Gustav Siebel: The Nassau-Siegener Landhecken: An investigation of the Cologne hedge and similar weir systems near Siegen. In: Siegerländer contributions to history and regional studies. Issue 12, Siegerländer Heimatverein, Siegen 1963.

- Johann Carl Bertram Stüve: Investigations on the Gogerichte in Westphalia and Lower Saxony. Frommann, Jena 1870. (Unchanged reprint: Wenner, Osnabrück 1972, ISBN 3-87898-067-1 .)

- Otto Weerth: About kinks and Landwehr. In: Correspondence sheet of the general association of German history and antiquity associations. Volume 54, 1906, Col. 372 (online)

- Herbert Woltering: The imperial city of Rothenburg ob der Tauber and its rule over the Landwehr. Part 1–2. Rothenburg odT, 1965-1971. (New edition in one volume. Verlag Degener & Co., Insingen 2010. (= Rothenburg-Franken-Edition. 4).

- Josef Würdinger: War history of Bavaria, Franconia, Palatinate and Swabia from 1347–1506. Munich 1868.

Web links

- Cornelia Kneppe: Landwehr at the intersection of history, archeology and natural history

- Hildegard Nelson: Landwehr in north-eastern Lower Saxony in the Lower Saxony Monument Atlas

Individual evidence

- ^ Martin Kollmann: Landwehr. In: Romerike Berge. Solingen. 57th year, 2007, issue 1, pp. 27–41.

- ↑ Cornelia Kneppe: Landwehren - From the medieval defense system to the biotope ; LWL Archeology in Westphalia, 2007.

- ↑ Zweischlingen (near Bielefeld) - History, paragraph: The Landwehr at Zweischlingen ( Memento from September 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Sebastian Kinder, Haik Thomas Porada on behalf of Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography Leipzig and Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig (ed.): Brandenburg an der Havel and surroundings. A geographical inventory in the area of Brandenburg an der Havel, Pritzerbe, Reckahn and Wusterwitz (= landscapes in Germany. Values of the German homeland . Volume 69). Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2006, ISBN 978-3-412-09103-3 , L. Historical data from Brandenburg an der Havel and the surrounding area. 1396, p. 404 .

- ↑ Sebastian Kinder, Haik Thomas Porada on behalf of Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography Leipzig and Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig (ed.): Brandenburg an der Havel and surroundings. A geographical inventory in the area of Brandenburg an der Havel, Pritzerbe, Reckahn and Wusterwitz (= landscapes in Germany. Values of the German homeland . Volume 69). Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-412-09103-0 , C15 Wendgräben with Neue Mühle and Görisgräben, since 1928 on Brandenburg an der Havel, p. 295-296 .

- ↑ Etymological dictionary of the German language. Berlin 1967, p. 280 f.

- ↑ schwiepinghook.de

- ↑ wiki-de.genealogy.net

- ↑ Christian Aßhoff: The Landwehr Himmelpforten - Ostönnen, a part of the Soest Foreign Landwehr? ( www.oberense.de ( Memento from September 13, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ))

- ↑ Äußere Landwehr von Würzburg In: wuerzburgwiki.de

- ^ Historical Commission for the Province of Saxony and for Anhalt, Wilhelm Zahn, State Historical Research Center for the Province of Saxony and for Anhalt, Historical Commission for the Province of Saxony and the Duchy of Anhalt, Historical Commission for the Province of Saxony: Die Wüstungen der Altmark. O. Hendel, 1909, DNB 364052910 , p. 103. (books.google.de)

- ↑ Landwehr in Werne. Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, accessed on June 22, 2013.

- ↑ Landwehr protected against cattle thieves. In: Ruhr news. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ↑ Cornelia Kneppe: Landwehr in the Principality of Münster. Regional Association of Westphalia-Lippe.

- ↑ lexika.digitale-sammlungen.de

- ↑ About the Rothenburger Landhege ( Memento from July 1, 2009 in the Internet Archive )