atheism

Atheism (from ancient Greek ἄθεος átheos "without God") denotes the absence or rejection of belief in God or gods. In contrast, deism and theism ( θεός / ϑεός theós "God") denote belief in gods, with monotheism denoting belief in one god and polytheism denoting belief in several gods. To atheism in the broader sense some also include agnosticism (agnostic atheism), according to which the existence of god or gods is unexplained or cannot be explained. In a narrower sense, it describes the belief that there are no gods.

Extent and origin of the term

The conceptual range of atheism includes, on the one hand, the "broad" conceptual meanings, which include an existence without belief in God, corresponding ways of life and related reasons (also known as "non-theism"), and on the other hand, "narrow" or "strong" meanings that include to be represented negatively on assertions of the gods, possibly militantly or with counter-evidence (also referred to as " antitheism ").

In ancient Greece , the term atheism was formed with the alpha privativum (A-theism) , it has different ancient Greek variants (noun: ἀθεότης in the sense of “godlessness, denial of God, unbelief”) and it was a sufficient charge in Asebie trials. The Latinized form "atheism" is first found in Cicero , since the end of the 16th century it appears in German literature ( early New High German atheisterey ) and it has been Germanized since the beginning of the 18th century.

During the Enlightenment period , it was initially free thinkers , deists , pantheists and Spinozists who were identified and accused of being atheists by philosophers and established churches. Some of the encyclopedists were particularly attached to atheism. As a fighting term, the atheist (southern states of the USA) also served and serves for the moral defamation of those who accepted theism , but deviated in individual aspects from the prevailing doctrine of God. However, someone who expressly denies believing in God or gods is usually referred to as an atheist.

Agnostics who do not believe in God are often counted as atheists in the broader sense, although not all agree. Agnostic views, according to which the non-existence of God cannot be recognized , are not named here. Agnosticism brings together different views; therefore the assignment of agnosticism to atheism is controversial (and vice versa).

The assignment of positivism to atheism is also controversial . The philosopher Alfred Jules Ayer , advocate of logical positivism ( logical empiricism ), emphasizes that his position on sentences like "God exists" should not be confused with atheism or agnosticism. He considers such sentences to be metaphysical utterances that are neither true nor false. On the other hand, characteristic of an atheist is the view "that it is at least likely that there is no God".

Whether positions should also be designated as “atheism” that do not assume any deity, but cannot be reduced to religiousness, such as in Jainism or Confucianism , is controversial in the literature. It is sometimes suggested that the explicit rejection of theistic positions should be called “theoretical” and life practice (which takes place “as if” a numinous did not exist) should be called “practical atheism”.

Since the 19th century, the term “atheism” has been used so narrowly in a naturalistic sense that it is directed against all supernaturalist conceptions that are associated with a belief in supernatural beings, forces or powers, both divine and non-divine ( animism , spiritualism , mono- and polytheistic religions). At the beginning of the 21st century, this is often referred to as "New Atheism" when the argument is proven to be scientific.

Social aspects

Demographic characteristics

Atheism polls raise methodological problems as it is difficult to draw a consistent line between secularists, humanists, non-theists, agnostics and spiritual persons. The line between believers and non-believers is becoming increasingly blurred.

The The World Factbook of the CIA estimated in 2010: atheists 2.32%, Non Religious 11.77%, Christian 33.32% (including 16.99% Roman Catholic), Muslim 21.01%.

In his “Balance of Unbelief”, Georges Minois thinks that there are tons of numbers in circulation, “which are all wrong”. At most one can see from them that more than a fifth of humanity no longer believes in a God. Minois himself presents estimates for 1993 - 1.2 billion agnostics and atheists worldwide - and for the year 2000 - about 1.1 billion agnostics and 262 million atheists, and for comparison about 1.2 billion believers for Islam and 1, 1 billion for the Catholic Church.

According to the Eurobarometer 2010, 20% of the citizens of the then 27 EU countries believed neither in God nor in any spiritual power. A majority of 51% believed in God and 26% in "some kind of spiritual power"; 3% did not comment. There were big differences between the individual countries; the share of believers in God was highest in Malta with 94% and Romania with 92% and lowest in the Czech Republic and 18% in Estonia with 16%. In Germany, Austria and Switzerland, 44% each was determined.

The number of residents who stated that they believed neither in God nor in a spiritual force was highest in 2010 with 40% in France and 37% in the Czech Republic and was 27% in Germany, 12% and 11% in Austria. in Switzerland. According to the 2005 Eurobarometer, more women (58%) believed in God than men (45%); belief in God correlated positively with age, politically conservative attitudes and a lack of schooling. In the US, the number of people who believe in God or a higher power is 91%.

The Worldwide Independent Network and the Gallup International Association surveyed almost 52,000 people from 57 countries about their religious attitudes between 2011 and 2012. 13% of the people surveyed described themselves as “staunch atheists”, 23% called themselves “non-religious” and 57% stated that they were religious. According to the study, 15% of the population in Germany are staunch atheists. China (47%) and Japan (31%) are the countries with the highest proportions of staunch atheists. Between 2005 and 2012, the proportion of religious people worldwide decreased by 9%, while the proportion of atheists increased by 3%. This trend is particularly pronounced in some countries: in Vietnam, Ireland and Switzerland, the proportion of people who describe themselves as religious fell by 23, 22 or 21% between 2005 and 2012.

According to surveys in the USA, the proportion of atheists among scientists is particularly high: only seven percent of the members of the American Academy of Sciences believe in the existence of a personal God. A 2009 poll of members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science found that 51% of American scientists believe in God or a higher power, significantly less than the general population. The proportion of atheistic scholars has not changed much over the 20th century. A survey by psychologist James H. Leuba in 1914 found that 42% of American scientists believed in a personal God and the same number did not. In 1996, the historian Edward J. Larson repeated the survey of Leuba with the same questions and the same number of people and came up with 40% religious and 45% atheistic scientists. A meta-analysis of 63 individual studies published in November 2013 came to the conclusion that atheism or non-belief in God is significantly related to intelligence (intelligence was measured in most studies by the g-factor ).

Several researches showed a positive relationship between religiosity and the birth rate . In 2002, for example, people in Germany who described themselves as non-religious had significantly fewer children with an average of 1.4 children than people who described themselves as religious (1.9 children on average). The Institute of German Economy came to similar results in an evaluation of the data collected worldwide by the World Values Survey .

Political interactions

Throughout history, atheists have come into conflict with political authorities in many ways. As recently as 2013, expressing atheist views was punished by imprisonment in numerous countries, and even with death in 13 countries.

In modern times, areas of society including politics, law and the practice of religion have become increasingly autonomous. The separation of church and state was enshrined in constitutional law with the help of educational movements and then shaped by state church law . This separation is called atheistic (especially in secularism ). In contrast to religious-political or state-theist rulers, the rule of law guarantees ideological neutrality in a procedurally fundamental way. State law constitutional bodies are correspondingly in their decisions not only religious but also by other external influences released and instead primarily a constitutional obligation that in modern states on freedom clauses based. The correspondingly neutral legal education led, even against political resistance, to an increasingly legally effective toleration of atheist positions and ways of life in the modern world.

Today, the constitutions of many democratic states contain the human right to religious freedom, including the right to be or become an atheist. There is not a strict separation of state and religion in all of these states , especially since religions are protected to different degrees for reasons of culture and self-determination (for example through the right to religious instruction). There is also the reference to God in constitutions. The preamble to the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany begins with the words: "Aware of its responsibility to God and people ...". The preamble to the Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation begins with the words: “In the name of God Almighty!” In 1998, when the constitution was completely revised, an attempt to delete this preamble failed. Some of today's penal codes contain regulations that view the abuse of denominations, religious groups and ideological associations as a criminal offense. As a result, atheist religious or church critics have repeatedly been prosecuted in the past for public statements.

On the other hand, atheism was part of the Marxist-Leninist state doctrine, for example in the Soviet Union and the German Democratic Republic , so that forms of religious practice had no place in the state-controlled educational institutions and were fought politically. Richard Schröder regards the secularization of East Germany as the most effective legacy of the SED regime. According to him, 91.5 percent of GDR citizens were church members in 1950, 67.4 percent in 1964 and around 25 percent at the end of the GDR . This development continues even after reunification, so the church-bound proportion of the population continued to decline and is now only around 15% in large cities such as Magdeburg or Halle. The membership of the two larger churches in East Germany is also very old and will therefore continue to decline.

The atheistic worldview, taught by the state as a doctrine of progress and based on Marxism, is described by critics such as Herbert Schnädelbach as "denominational atheism" and "state religion" or "state atheism". A total religious ban was declared in Albania in 1967 (until 1990) and the country described itself as the “first atheist state in the world”. Atheism was promoted throughout the so-called Eastern Bloc , while practiced religiosity was at least viewed with suspicion, was often associated with disadvantages or was even deliberately persecuted, such as in the persecution of Christians under Stalin . According to NGOs, religious groups and individuals are still persecuted and often imprisoned, tortured and killed in some states that see themselves as “atheistic”, such as North Korea.

Atheism is actively promoted, for example in humanism , existentialism and the free thinker movement . To a large extent, socialism , communism and anarchism are atheistically shaped world views. In the last two decades of the 20th century, so Georges Minois in his History of Atheism , the zeal of the anti-religious struggle has subsided: “The camps are falling apart rapidly, apart from an inevitable hard core on both sides. Doubt permeates all minds, nourished by a feeling of powerlessness and futility, almost nothing compared to questions that once inflamed the spirits. "

Significance in the scientific context

Orientation towards scientific explanatory models made the “God hypothesis” appear methodologically inadmissible for some scientists early on, since it had no scientifically observable consequences, and therefore did not explain any scientifically describable phenomena. Such an exclusion of God from scientific research is called methodological or methodological atheism. However, it does not imply theoretical atheism, i.e. it does not claim that God does not exist. This is why the term “methodological non-interventionism” is sometimes used more precisely.

The question of whether scientific thinking and the assumption of a god can be related at all in such a way that a mutual confirmation or refutation is conceivable is controversial among science theorists. Opposite assumptions can also be found in popular scientific writings. Some, e.g. B. Stephen Jay Gould and John Polkinghorne , take the position that science is not in conflict with religion, since the former deals with empiricism and the latter with questions of ultimate justification and moral values. Others, e.g. B. Richard Dawkins , Steven Weinberg, and Norman Levitt , argue that theism is fundamentally incompatible with a scientific worldview, since miracles like the resurrection of Jesus Christ must override the laws of nature; science inevitably leads to atheism, deism or pantheism.

Up to the middle of the 20th century there were still several powerful, even intellectually hegemonic “scientific worldviews”, including Marxism in several political forms, psychoanalysis and neopositivism , which were declared atheistic and ascribed a harmful effect to religions.

Atheism and morality

In other represented Immanuel Kant the view that moral principles without resorting to higher beings in human reason had to found or in nature. Law and morals would allow maxims of freedom and action to exist under general (rational) laws. At least it should be deducible here that the assessment criteria are rationally negotiable.

Especially in church circles, the opinion is expressed that the lack of faith in God is accompanied by the negation of moral values in the sense of nihilism . The evangelical religious scholar and journalist Ravi Zacharias describes atheism as "deprived of all value" and denies that there can be well-founded moral principles without recourse to higher beings. The Catholic constitutional lawyer and former constitutional judge Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde is quoted with the formula: "The liberal, secularized state lives from conditions that it cannot guarantee itself." This so-called Böckenförde dictum is partly interpreted as meaning that democracies are based on religious ties Guarantors of common basic values are dependent.

Gerhard Czermak turns against this interpretation . He thinks that Böckenförde is "thoroughly misunderstood, if not instrumentalized", provided that it is derived from his dictum,

"[...] the state must support the churches and religious societies as value creators in a special way, because otherwise the destruction would be promoted [...]. He [Böckernförde] speaks of risk and refers to the very different forces at work in society. He is concerned that all groups contribute to the integration of a part of society with their own, also moral, self-image. "

Empirical results on morality and their interpretation

The relationship between religion and morality is also not empirically clarified. Some research suggests that personal morality does not depend on personal religiosity. So found z. For example, Franzblau is more honest with atheists, and Ross is more willing to help the poor with atheists. Gero von Randow takes from socio-psychological studies “a remarkably low crime rate among non-believers. Conversely, this should not be used in their favor, because they tend to be socially better off and more educated than the believers, at least in the West; so we are not dealing with a religion but with a class effect. ”A separation of morality and theism is the view that John Leslie Mackie in his book Ethics and Richard Dawkins in his book Der Gotteswahn explain, namely that morality is linked to the process of biological evolution and is the result of a socially influenced development process. From this it can follow that human morality will endure even when religions fall into decline.

Empirical results for the search for meaning

According to an empirical study, atheism (just like not feeling part of a religious group) is linked to the idea that life is meaningful when one gives it meaning for oneself. Atheists and theists, on the other hand, do not differ in terms of their propensity for fatalism or nihilism.

Demarcation from religious orientations

From an atheist perspective, acting on the basis of supposedly divine commandments appears questionable, because the evaluation of a behavior or an action does not depend on the consequences for the person concerned, i.e. is aimed at the interpersonal level, but is considered ethically desirable mainly through the extrinsic establishment of a transcendent being. According to a strictly theistic view, murder, for example, would be a bad, condemnable act not just because of the consequences for the victim, but on the basis of divine commandments. “It seems extremely problematic to try to base something as necessary as morality on the basis of something as dubious as it is religious belief. How should a real orientation and life knowledge be possible in this way? ”Writes Gerhard Streminger . Already Plato had in his early dialogue " Euthyphro " with the so-called Euthyphro dilemma pointed out that it is generally impossible to morally good to justify recourse to a divine principle. According to Kant, a person's obligation to morality cannot in principle be justified by referring to the “idea of another being above him”, that is, to a god.

Some atheists counter the argument that without a law given by a divine authority that is equally binding for everyone, it is more difficult to find a common ethical basis for a society: No religion can convincingly justify why its law has been given by a divine authority should have been and should therefore be able to claim general liability. Not even the existence of any divine authority can be convincingly justified. One can assume that the laws of religions are just as man-made as all other laws and rules of behavior: partly on the basis of reason and insight, partly on the basis of the interests of those who had enough power to enforce their ideas .

While, on the one hand, laws of a divine authority are seen as an aid to stabilizing social coexistence, some atheists take the view that the claims of religions to the universality of their laws have often made it difficult to find a common ethical basis for a society. Not infrequently, the attempt to enforce this general binding effect led to persecution, expulsions or even religious wars. Conversely, reference is made to the persecution of Christians in accordance with atheist state doctrine.

Atheists often consider a religious conviction to be a hindrance to the development of a common (moral) ethical basis: Many believers feel bound by divine laws and are probably therefore less willing to develop their ideas further in cooperation with other people. “If adherents of religiously founded ethics clash, conflicts can hardly be resolved in a sensible way, since everyone feels guided by God; everyone believes that their own commandments are objectively given, that they are God's will, ”writes Gerhard Streminger. Some believers, on the other hand, consider the (moral) ethical ideas that their religion has in common with related religions as a good basis for cooperation and further development.

From an atheistic point of view, one problem of a lack of willingness to further develop ethical ideas can be that the adaptation of rules of conduct to new social conditions is prevented. For the ethical assessment of a divorce, for example, one has to consider whether the woman would be exposed to material hardship and social ostracism as a consequence, or whether she would remain materially secure and socially accepted.

Atheist ideological groups

While religious representatives often deny atheists the ethical foundation necessary for a functioning social coexistence, on the other hand - mainly in the western world - there has been a lively debate for some decades about whether non-atheist humanism offers a more contemporary basis for a general ethics than traditional religions .

German-speaking groups, foundations and umbrella organizations:

- Atheist Religious Society in Austria (ARG)

- Umbrella organization of free ideological communities (DFW)

- Giordano Bruno Foundation (gbs)

- Humanistic Association of Germany (HVD)

- Humanistic Association Austria (HVÖ)

- Coordination Council of Secular Organizations (KORSO)

- Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science

Groups, foundations and umbrella organizations operating abroad:

- American atheists

- Council for Secular Humanism (CSH)

- Freedom From Religion Foundation (FFRF)

- Humanists UK , formerly British Humanist Association (BHA)

- National Secular Society (NSS)

- Rationalist International

- Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science (RDFRS or RDF)

- Unione degli Atei e degli Agnostici Razionalisti (UAAR)

International movements, umbrella organizations and committees:

- Atheist Alliance International (AAI)

- Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI)

- International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU)

Religious atheism

In his lectures on Albert Einstein , Ronald Dworkin dealt with the question of what could be religious about an attitude in which God obviously plays no role . His answer: “Religion is something deeper than God.” “He saw himself as a religious atheist, that is, he did not believe in God, but in the meaningful unity of the cosmos and the reconciliation of faith and knowledge.” While theists she regard as commanded by God, Dworkin argues that our ethical beliefs "we could not have without thinking that they are objectively true".

Atheism as a religious creed

Some atheists understand their worldview as a religious creed and strive for equal rights and equal treatment by the state by means of religious recognition as a religious community.

A German-speaking group of this type is the Atheistic Religious Society in Austria . On December 30, 2019, she submitted the application to the Office of Culture in the Austrian Federal Chancellery for the establishment of legal personality as a state-registered religious denomination "Atheistic Religious Society in Austria" .

Free religious movement

According to the self- portrayal of the free religious movement, there are also atheists or atheistic-religious positions among the free religious.

Jewish and Christian atheism

The religious criticism of the Bible is the starting point of a Jewish and Christian atheism. Douglas Rushkoff , professor of communication theory at New York University, describes Judaism as a way out of religion because of the imagery of the biblical God ( Nothing Sacred: The Truth about Judaism , 2004). In the 1960s, a group of theologians formed in the USA who proclaimed Christian atheism under the phrase " God is dead ". Representatives of this trend are the theologian Thomas J. Altizer ( The Gospel of christian atheism , 1966), William Hamilton ( Radical Theology and the Death of God , 1966), Paul van Buren ( The secular meaning of the Gospel , 1963) and Gabriel Vahanian ( The death of God , 1961).

According to J. Altizer, for example, the "death of God", i.e. the supposed impossibility of rationally believing in a god in the modern world, is good news because it freed people from a transcendent tyrant. According to Paul van Buren, the secular message of the Gospels relates only to the “liberator” Jesus of Nazareth . While the belief in a (otherworldly) God is rejected, the “Christian atheists” focus on the ethical and moral message of Jesus, which is purely related to this world. In the period after the Second World War, a link between atheism and Christianity developed that explicitly refers to God's silence in the face of the murder of millions of Jews by German National Socialists in the Holocaust . The German theologian Dorothee Sölle is the best-known representative of this direction. Some theologians of the "God is dead theology" were also influenced by Ernst Bloch's religious-philosophical thoughts in the third volume of his main work The Principle of Hope . In 1968 Bloch summarized, specified and expanded upon thoughts from this in the book Atheism in Christianity , in which the sentence can be found:

"Only an atheist can be a good Christian, but also certainly: only a Christian can be a good atheist."

Dorothee Sölle, influenced by Bloch, also published a book in 1968 with a very similar title: Believing in God atheistically. For Ernst Bloch and Dorothee Sölle, atheism does not mean renouncing meaningfulness or transcendence, but turning away from an overly theistic image of God, the idea of a God who, as an omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent God, allowed hardship and suffering up to Auschwitz . In the deconstruction and following the thought of Emmanuel Levinas and Jacques Derrida , another approach to the elaboration of a Christian atheism was found. Representatives include Peter Rollins and Jean-Luc Nancy ( Deconstruction of Christianity 2008). In short, one can see in it the appropriation of the gesture of deconstruction, in which the son dissolves the law, the arché of the father, while he himself is condemned by the law. This connects the messianic approaches of the late Derrida with his thinking about the différance .

Buddhism

The Buddhism knows no faith in a Creator God. Some Buddhist schools, however, assume in their cosmology the existence of numerous other levels of reality on which both better and worse off beings exist, of which the higher beings correspond to the Hindu gods ( Devas and Asuras ). However, like all beings, these gods are caught in the cycle of existence, samsara ; In the sense of the doctrine of rebirth, every being can at some point also be born as a deva , if the corresponding karma (in this case extremely great generosity or samadhi experiences) has been accumulated.

In Mahayana - or northern Buddhism, beings who have become Buddhas or Bodhisattvas themselves are worshiped . The respect that you show them creates one of the necessary foundations to achieve this state yourself. Therefore, numerous statues, stupas and temples are erected in Buddhism that are objects of worship. But these beings are not gods, but role models . In Theravada - or southern Buddhism, the goal is arhatships , i.e. liberation without return, so that arhats can only be worshiped in the last phase of their last life. There are also countless stupas , temples, statues of Buddha and images of earlier arhats, sometimes even of bodhisattvas. The question of a creator god is rejected as sterile metaphysical speculation and instead emphasizes the exploration of one's own possibilities of knowledge .

Islam

In Islamic cultures, atheists fall under the term kāfir ('unbeliever', 'God denier'). Muslims are not given the right to change their religion or become atheists.

The Koran does not mention this-worldly punishment for " apostasy ", which also includes the allowance falls to atheism. In Islamic law, the Sharia , however, this is punishable by the death penalty on the basis of hadiths and idschmāʿ . In Sudan (StGB from 1991, Art. 126), the Republic of Yemen , Iran , Saudi Arabia , Qatar , Pakistan , Afghanistan , Somalia and Mauritania (StGB from 1984, Art. 306), apostasy from Islam can still occur today be punished with death.

Even in countries that no longer have Islamic courts of justice, but whose state legal system is still based on Sharia law, the declared “apostasy from the Islamic faith” can have consequences under civil law ( inheritance law , marriage law ) and criminal law .

pantheism

In the pantheistic (Greek: universal theory) concept of God, the solitude of the universe takes on the creative role. God and nature are therefore in a sense identical. Since there is no personal God in pantheism, pantheism was and is sometimes viewed by both theists and atheists as an atheism hidden behind a religious language. Arthur Schopenhauer called pantheism a “ euphemy for atheism”. "Pantheism is just a polite atheism," it says in a Schopenhauer quote from Ernst Haeckel. In his work, the French philosopher Jean Guitton is convinced that he can demonstrate that atheism has transferred the concept of God into the world and therefore generally assigns it to pantheism. Pantheism is regarded by its followers as a doctrine of the philosophy of religion and was not regarded as belonging to atheism in earlier times, but this has now changed.

historical development

Atheism is "as old as human thought, as old as belief, and the conflict between the two is a constant feature of western civilization," says Georges Minois , who seeks to capture atheism in terms of both the history of ideas and behavior. For the early advanced cultures, however, the difficulty arises that sacred buildings and cultic writings have always been among the predominant testimonies, while the less conspicuous testimonies of skepticism, non-belief and religious indifference have only recently been subjected to intensified research, such as includes the Asian region. Practical and theoretical atheism had and still have their own and complementary meaning:

“The history of atheism is not only the history of Epicureanism, free-spirited skepticism, Enlightenment materialism, Marxism, nihilism, and a few other intellectual theories. It is also the story of millions of ordinary people who are stuck in their everyday worries and too preoccupied with mere survival to ask questions about the gods. "

In antiquity and the Middle Ages , both private and public life were as a rule permeated by religious ideas, whereas skepticism and doubt tended to be found among minorities and in intellectual circles. While the critical debates within the Roman Catholic Church intensified in the late Middle Ages and reached a climax in the Reformation , atheism experienced a significant upswing in the Age of Enlightenment and spread through the French Revolution . This led to secularization and, in many cases, to the separation of church and state .

In the 19th and 20th centuries, a wide variety of atheistic positions with a broad theoretical foundation were developed, especially in Marxism , existentialism and analytical philosophy . In addition, there are lines of connection with atheism in philosophical materialism and in philosophical naturalism.

South and Middle East

The earliest verifiable forms of theoretical atheism can be found in the ancient high cultures of South and Near East Asia . In India some of the oldest philosophical systems have atheistic forms. These include Jainism , Samkhya (both originated around the 6th century BC) as well as Vaisheshika and Nyaya . In particular, the tradition of Samkhya has remained alive in Indian thought to this day (compare atheism in India ).

The Indian school of the Charvaka was clearly materialistic and atheistic . Century AD as a fixed current and existed at least until the 16th century. She referred to the " Barhaspati Sutras " lost today . In the opinion of many Indologists , however, it was not an atheistic work, but a skeptical, but ethical, scripture against established religions. Individual skeptics are from the 5th century BC. Passed down to the 6th century AD.

The Buddhism who in the 5th century. Arose in India, and Daoism , which emerged in the 4th century BC. BC in China, know no creator deity.

In parts of the specialist literature, the cervanism of the ancient Persians with the overriding impersonal principle of Zurvan ("time" and space) is viewed as a form of atheism. Materialistic and predominantly atheistic was the current of the "Zandiks" or "Dahri" , which had existed at least since the 5th century AD .

Whether the Hebrews knew a theoretical atheism is disputed. Jean Meslier saw evidence of the existence of atheists in some passages of the Old Testament. So z. B. in Ps 10: 3:

“The wicked speak proudly: / 'He will never punish, there is no God!' / This is all of his senses and aspirations. "

Most scholars do not share this interpretation . In her opinion, only certain properties of God are denied in the said passages, but never his existence.

Greco-Roman antiquity

Pre-Socratics

The fragmentary ontological systems of the pre-Socratics explain the structures of reality not through mythical or etiological narratives, but through tracing back to one or more principles. In the case of Democritus or Epicurus , for example, only material principles come into consideration, so that a transcendent, especially spiritual God is neither used, nor could it get a place or function in these systems. On the other hand, conflicts with established religious cult and established discourse about the gods sometimes arise because ontological principles are ascribed to similar or the same properties as the gods, for example to rule over natural processes, to be eternal or to be the principle for life and thought. The earliest forms of criticism of the established ideas of God relate primarily to inappropriately human modes of representation ( anthropomorphism ). Gods are z. For example, fickle, irascible, jealous, and egotistical character traits as they emerge in the myths of Hesiod and Homer are denied . Examples are Xenophanes , Heraclitus and Protagoras . Xenophanes, for example, explains the ideas of gods and their differences by projecting human characteristics and formulates it polemically:

“Blunt-nosed, black: that's how the people of Ethiopia see the gods.

Blue-eyed and blond: that's how their gods see the Thracians.

But the cattle and horses and lions, if they had hands,

hands like humans, for drawing, for painting, for a picture form,

then horses would the gods same horses, the cattle equal cattle

painting, and their shapes, the forms of the divine body,

created after its own image. each according to his "

While such anthropomorphic ideas of God, so the tenor of this criticism, are nothing other than just human ideas, the critical corrective is increasingly being opposed to the idea of a monotheistic, transcendent divine or quasi-divine principle. Empedocles (* between 494 and 482; † between 434 and 420 BC) also saw personifications of the four elements in gods . Critias (* 460; † 403 BC) regarded religion as a human invention that was supposed to serve to maintain moral order.

Skepticism and Asebie Trials

A move away from or questioning of the gods worshiped in the polis by skeptical philosophers or scientifically oriented thinkers could lead to indictments and convictions. In ancient Athens, godlessness and iniquity against gods were sometimes prosecuted as Asebeia . A first wave of well-known Asebie trials, in which political motives are likely to have participated, was directed against confidants and friends of Pericles , including Aspasia and Anaxagoras .

In the 5th century BC The process of questioning traditional images of God, which was promoted by the Sophists in particular and which was reacted to in the Asebie trials, continued unstoppably. Resistance in this form was also encountered by 415 BC because of his religious relativism. BC Protagoras banished from Athens , who emphasized his ignorance of the existence of the gods and at the same time declared that man is the measure of all things. Skepticistic and agnostic positions, such as those represented by the Sophists and Socrates (* 469; † 399 BC), became increasingly widespread, and the indictment of godlessness against the "physicists" became common practice: "The scholar who in one working in a positivist spirit, is accused of wanting to fathom the mystery of the gods and, so to speak, 'dissect' the sacred. ”Some of the accused in the traditional asebie trials represented not only an agnostic, but a decidedly atheist position ( Diagoras von Melos , Theodoros von Cyrene ). An asebie trial has been handed down against Phryne , admired for her beauty , according to which the nude model work for an Aphrodite statue was interpreted as an outrage against the gods.

The trial against Socrates had an impact that still resonates in the history of ideas . His skepticism of faith is expressed in the Platonic dialogue Phaedrus : It is absurd to say anything about the myths and the gods, since he does not even have the time or is able to recognize himself. "So it seems ridiculous to me as long as I am ignorant of this to think of other things."

As a pupil of Socrates, Plato is not only the most important source of tradition for his thinking and philosophizing, but also , according to Minois , the person primarily responsible for the ostracism of atheism in the following two millennia. In his late work Nomoi (Laws) he takes a pantheistic position, which is differentiated from a strict naturalism, because it misunderstands the non-material forces of action:

"Will we now be able to draw a conclusion other than the same about the moon and all the stars, over the years, months and seasons, than the same one again: because one or more souls underlie them all as active forces and as beings of all possible perfection have appeared, we must assert that all these beings are gods, they may now live in bodies and connected with them to form living beings, or in whatever other way always lead and rule the whole world? And whoever admits this will be able to deny that everything is filled with gods? "

In the tenth book of the Nomoi , Plato seeks to prove that there are gods, that they also take care of the little things in life, but without being corruptible, and furthermore to justify that atheists depending on the degree of denial of God and hypocrisy be subject to graduated sanctions up to the death penalty. Since in Plato's teaching there is a higher-valued world of ideas, archetypes , souls and the divine outside the material world , atheists, Minois says, are henceforth ruled by lower thinking and unable to rise to contemplation of ideas.

“To be an atheist could up to now, if necessary, be considered an error and evidence of anti-subversive thinking; from now on it is not only a sign of blindness, but also a sign of bad will and malevolence, dangerous for social and political life, since it does not recognize absolute values in public and private behavior. The sources of morality so far have been in the human world, which is not fundamentally different from the divine world. By separating the two and placing unchangeable values with the gods, Plato declares the atheists to be immoral people who know no absolute norms of behavior and only obey their passions. The suppression of atheism in the name of morality and truth can begin. "

The influence of Platonic schools on the suppression of atheism is controversial. When the trials of godlessness during the 4th century BC Declined in BC, skeptical attitudes had not decreased, but meanwhile so widespread that criminal prosecution had less and less effect. The Cynic Diogenes (* approx. 400; † 325 BC) was able to spread his mockery of gods, mysteries, providence and superstitions in Athens without being tried.

Hellenism

While the worship of the anthropomorphic Olympian gods also lost more and more importance in domestic cult, in the course of the disintegration of the polis and the conventional city-state order - on the way to the Hellenistic empires and then to the Roman Empire - all sorts of imported mystery cults and foreign deities appeared also increasingly deified rulers who in this way diverted religious commitment to their own advantage.

Far removed from the old forms of belief are those at the turn of the 4th to the 3rd century BC. The philosophical doctrines of Epicureanism and the Stoa emerged in the 4th century BC . With the Stoics, pantheistic ideas unfold, which merge the divine with the all-nature and find in it the place of action for the people and for their ethical reference system. In Epicurus the gods disappear into worlds separate from human existence and have no power of influence over people and their doings. True to the purely materialistic worldview of Epicurus, the gods are also atomically constituted beings. However, Epicurus recommends, as a way of maintaining peace of mind, to adapt flexibly to the cults and religious customs prescribed by the state.

Roman antiquity

With the Roman expansion, the traditional Latin gods lost their binding force and importance. The conquest of Greece and the eastern Mediterranean basin by the Romans brought, with foreign religions and deities, an abundance of spiritualistic and materialistic schools of thought to Rome, such as Cybele , Isis , Osiris and Serapis , as well as astrological and magical ideas as well as Platonic, Cynic and skeptical, Epicurean and Stoic teachings .

Epicureanism, hymnically spread by Lucretius in Rome, at the center of which is an ascetic striving for pleasure and happiness, presents itself with the complete separation of the gods as a basically consistently atheistic moral doctrine. The Stoa, in turn, that in the ruling circles of Roman society was often accepted, conveys a vaguely blurred concept of God and hardly separates any longer between man and God in the ideal of the stoic wise man. Cicero's investigation into the nature of the gods ( De natura deorum ) resulted in skepticism: "Even those who think they know something about it will be determined by the great disagreement of the most learned men on this important question."

A basic agnostic mood - admittedly less reflected - seems to have been widespread in popular circles in the early Roman Empire (parallel to the beginning of early Christianity ); In his satirical novel Satyricon (in the scene of the Banquet of Trimalchio ) the writer Petronius puts the words in the mouth of the protagonist Ganymedes :

"Nobody believes in heaven anymore, nobody keeps the fast, nobody cares about Jupiter, everyone closes their eyes and only counts their cash."

In contrast to the increasing diversity of ideological and religious ideas, there was a willingness to discriminate as atheism and to criminalize what did not belong to the established state cults. Christianity was also affected by this in its beginnings. Because its followers refused to take part in the religious state cults for reasons of faith. In the rejection of the imperial cult in particular , they often became martyrs .

Middle Ages and Reformation

Whether there was atheism in the sense of a denial of the existence of a god in the Middle Ages is controversial. Traditionally, the “Christian Middle Ages” is seen as the age in which Europe was completely dominated by Christianity, with the exception of small Jewish and Muslim minorities. The often poor and almost entirely Christian sources make it difficult to clearly assign individual thinkers or groups of people to atheism.

The theologian Walter R. Dietz writes that the term atheism was only used in the Middle Ages for denial of the threefold idea of God, for example by Islam . According to the evangelical theologian Jan Milič Lochman , atheism in the sense of denial of God or godlessness did not appear in Europe until the 16th and 17th centuries. According to the French historian Georges Minois , there was certainly atheism in the Middle Ages, both in its practical and at least to some extent in its theoretical form. Faith dominated the Middle Ages, but atheism survived in the life and thinking of a minority.

Theoretical atheism

Since the 13th century, there has been an increasing criticism of Christian-Catholic beliefs. The rediscovery of Aristotelian teachings and their interpretation by Islamic philosophers seems to have played an essential role here . In particular, Aristotelianism and Averroism were powerful . Significantly, although Aristotle was sometimes referred to as a “ pagan ”, he was considered the master of logical thinking. The Aristotelian philosophy contradicts the Christian teaching in two points in particular: It denies the creation and the immortality of the soul . Therefore, teaching his physics and metaphysics was also repeatedly forbidden by papal decree.

Nevertheless, according to Georges Minois, reason fought for an increasingly greater independence from faith between the 11th and 13th centuries. Peter Abelardus demanded that belief should not contradict the rules of reason. Boetius von Dacien advocated the strict separation of rationally comprehensible truth and truths of faith . Siger von Brabant went even further and denied numerous central Christian dogmas. The Christian authority reacted on the one hand with censorship and repression. In addition, however, there were also increased efforts to underpin the faith with evidence of God .

Wilhelm von Ockham declared all attempts to prove beliefs with the means of reason as doomed to failure from the start.

Practical atheism

In the 12th century, the Goliards provoked in their songs with sometimes deliberately provocative atheistic positions such as "I am more eager for lust than for eternal salvation" . The English lollards also took a skeptical attitude towards many beliefs . Some of the so-called " blasphemics " could also have been atheists. In the book by the three deceivers , which is attributed to several authors , Moses , Jesus Christ and Mohammed are meant. In addition, pantheistic worldviews lived on in smaller religious communities and among individuals. Although they cannot be assigned to atheism in the narrower sense, they did challenge the Christian faith. Representatives are in particular the Parisian theologians David von Dinant and Amalrich von Bena , as well as the brothers and sisters of the free spirit .

The existence of unbelievers in the people is attested in numerous accounts of miracles . In addition, materialistic-atheistic positions can be demonstrated in the simple peasant people. Among other things, the existence of an immortal soul and the resurrection of Christ were denied. An example of this kind of "popular materialism" is recorded in the interrogation protocols of the Italian miller Menocchio . Towards the end of the Middle Ages there are also increasing complaints from Christian parishes about the weak presence of the community at Sunday mass.

Mercenaries and excommunicated people are named as medieval sections of the population that were particularly affected by atheism . The number of the latter went into the tens of thousands in France alone.

reformation

The Reformation did not turn away from the (Christian) faith, but even enhanced personal faith in the sense of subjective conviction. Nevertheless, the Reformation is an important turning point not only in the history of religion but also in that of atheism.

As a result of the Reformation, the Protestant denominations were able to establish themselves for the first time alongside the Catholic churches, which were too strong to be permanently suppressed by force. In the long run, both sides were forced to religious tolerance , which was later expanded to include groups that were initially not included in this tolerance, such as the Reformed . This development towards tolerance would later also benefit atheists. As a result of the religious wars that followed the Reformation, the warring churches discredited themselves in the eyes of many. The contradiction between publicly preached Christian charity and the actual action of the churches of the time, for example in the obvious barbarism of the Huguenot Wars and the Thirty Years' War, became apparent. It is also significant that the Catholic Church lost its almost inviolable monopoly of interpretation for the traditional interpretation of the Bible and thus lost a considerable amount of authority in the spiritual field.

Politically, the Reformation made a decisive contribution to the emancipation of states from their spiritual ties to the Church, which now had to subordinate itself to politics in many cases, for example in sovereign rule, in French Gallicanism and the imperial church . This emergence of modern power relations was an essential prerequisite for ultimately enabling the separation of church and state . The freedom of religion guaranteed by this expanded, even if the way there was by no means without repression, finally also to respect the right to disbelief. Nevertheless, atheism remained a phenomenon of an elite minority until the last third of the 19th century.

17th to 19th century

The Age of Enlightenment brought with it the first theoretically formulated atheism of modern times. This is closely related to the advances in science . As early as 1674, the German theologian Matthias Knutzen went public with three atheistic writings that made him the first atheist of modern times known by name. A decade later, the Polish philosopher Kazimierz Łyszczyński followed in his - except for a few quotes lost - work De non existentia Dei (Eng. About the non-existence of God ), in which he postulated that God is just a man-made chimera and religion is only one Means of oppression of the population. Despite the religious freedom in force in the Kingdom of Poland at that time , Łyszczyński was sentenced to death for political reasons and executed for his work in 1689.

Until well into the 18th century, the accusation of being an 'atheist' was usually a dangerous external attribution. In Prussia it was the enlightenment attitude of Frederick the Great (1740: "Everyone should be saved according to his own style"), in other countries the declaration of human and civil rights in the French Revolution (1789) and the American Bill of Rights (1789) which led to the acceptance of various atheistic points of view. In 1748, the French philosopher and enlightener Julien Offray de La Mettrie was only able to publicly represent his atheistic philosophy outside France, in Prussian exile. In the German language, in a critical turn against Hegel , the ex-theologians Bruno Bauer and Ludwig Feuerbach were the first atheistic philosophers. In his influential work Das Wesen des Christianentums (1841), Feuerbach not only criticized Christianity fundamentally, but also religion in general as the result of psychological projections (“Man created God in his image”). Friedrich Nietzsche later stated : "God is dead" (1882) and "Atheism [...] goes without saying for me out of instinct" (1888).

Enlightenment in France

The earliest evidence of a dedicated atheism in modern times can be found in Theophrastus redivivus , the work of an anonymous French author from 1659. The existence of God is denied, but the social usefulness of religion is asserted.

The French Abbé Jean Meslier (1664–1729) is considered the first radical atheist of the modern age . In his Pensées et sentiments , written between 1719 and 1729 and only later published anonymously , Meslier completely denied the existence of gods, which for him are mere fantasies. In contrast to Theophrastus , Meslier combines his atheism with an anti-clericalism : He polemics against the church and the crown, which he regards as exploiters and oppressors of the poor. Meslier left only three handwritten copies of his writing, which became known as the will , which initially circulated clandestinely for a few decades . It was not until 1761 that Voltaire published a version of the book in which he had erased all atheist and materialist passages and only received Mesler's criticism of Christianity and anti-clericalism. This deistically falsified version, especially since it found widespread circulation through new editions and inclusion in Voltaire's oeuvres , remained the generally known until the 20th century; A complete edition published in Amsterdam in 1864 did nothing to change this. It was not until 1972 that Albert Soboul et al. a. based on the original manuscripts, a now authoritative edition of this first modern work of atheism was created.

While Meslier was thus long considered a Voltairian anti-clerical deist, the first known radical atheist of the Enlightenment was Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709–1751). His philosophical debut Histoire naturelle de l'âme (Natural History of the Soul, 1745) was burned by the Parisian executioner as a materialistic and atheistic work. La Mettrie fled to Holland, where he published his famous work L'homme machine (Man as Machine, 1748), which says “that the world will never be happy unless it is atheist.” La Mettrie did not stay stand at the negation of God, but rather sketched in his Discours sur le bonheur (Speech about happiness, 1748) a seemingly modern psycho (patho) logical theory of the religious. He then even had to flee from the tolerant Netherlands. Friedrich II of Prussia offered him asylum and hired him as a reader in Sanssouci . He was also admitted to the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin .

An early public denial of the existence of a god can also be found in the work Système de la nature by Baron d'Holbach (1723–1789), published anonymously in 1770 , a basic work of materialism . Holbach saw religion as the greatest enemy of natural morality and took to the field against ontological and cosmological proofs of God . In his opinion, human happiness depends on atheism. The "ethocracy" he advocates, however, is not based on the previous materialistic philosophy of La Mettrie, whom he even described as a "madman" because of his moral theory.

Denis Diderot (1713–1784), best known as the editor of the Encyclopédie , initially represented a deist, in his works critical of church and religion, Pensées philosophiques (1746) and the Lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage de ceux qui voient (1749) later an atheist position. He was also a vehement opponent of La Mettrie, whom he posthumously excluded from the crowd of philosophers as an “author without judgment” and because of the “corruption of his heart”.

Voltaire sharply criticized the church and the clergy and attacked the Christian religion in countless writings and letters, sometimes with astute mockery and sometimes with subtle irony. However, he expressly did not want to be called an atheist (Réponse au Système de la nature, 1777). In the Athéisme article he wrote, among other things:

“Atheism is the mistake of some people of spirit, superstition is the mistake of fools; and rags are rags. "

Even though Voltaire frequently professed English deism, his style and the way in which he presented his deism made him an atheist for many of his contemporaries. The Catholic Church therefore accused him of atheism. Fritz Mauthner , author of the four-volume work Atheism and its History in the West , called Voltaire "the general and statesman of the French and European free thinkers."

Immanuel Kant

According to Immanuel Kant, there is no possible evidence for or against the existence of a Supreme Being, either by applying reason or by considering empirical nature. As Kant tries to show in the Transcendental Dialectic , the second main part of the Transcendental Logic in the Critique of Pure Reason , all proofs of God fail because the idea present in human reason is a transcendental idea , i.e. H. the idea of an object that cannot correspond to any possible human experience. He does, however, grant transcendental ideas a regulative function:

“Accordingly, I assert: the transcendental ideas are never of constitutive use, in such a way that they give concepts of certain objects, and if they are understood in this way, they are merely rational (dialectical) concepts. On the other hand, however, they have an excellent and indispensably necessary regulative use, namely to direct the understanding to a certain goal, in view of which the lines of direction of all its rules converge in a point which, whether it is only an idea (focus imaginarius), i.e. . i. is a point from which the concepts of the understanding really do not emerge, in that it lies completely outside the limits of possible experience, but nevertheless serves to provide them with the greatest unity alongside the greatest expansion. "

Put simply, this means that things that transcend possible human experience (God, immortality , infinity ) are not recognizable according to Kant, but they give the experience a certain, subjective unity. They are regulative because they offer the mind an orientation with which it can order experiences and impressions beyond their immediate perceptual content. Thus, from a theoretical point of view, Kant is a representative of an agnosticist position. The regulative idea “God”, however, takes on a new function in Kant's moral philosophy.

If Kant deals with the theoretical side of reason (“What can I know?”) In the Critique of Pure Reason, the Critique of Practical Reason deals with its practical side (“What should I do?”). God is postulated here : If human reason is able to set goals for itself freely, e.g. B. also against the directly felt empirical needs, this presupposes that every person experiences his own reason as binding (Kant calls this the “fact of reason”). That part of the human will that makes its choice based on reason and independently of empirical needs can now, according to Kant, want nothing other than to follow a moral law. The moral law obliges every man to morality by stopping him, his will after the categorical imperative to make. For Kant there is a problem in showing whether and why following the moral law also leads to happiness , i.e. a state of general satisfaction. The question is: if I am to act morally, is it also ensured that I will be happy? As the authority that ensures that moral behavior also leads to happiness, God is introduced to guarantee that the world as a whole follows a righteous plan.

In the succession, Kant's theistic skepticism or partial agnosticism went largely unnoticed. The German idealism ( Fichte , Schelling , Hölderlin , Hegel though) spoke of God as the absolute world spirit or an absolute I , however, paid little attention to the antinomies of reason. From today's perspective, Kant's postulate of a god as a link between morality and happiness is seen more as a defect in his theory. Kant's individualistic theory simply lacks the social horizon of morality. In his legal philosophy, however, Hegel manages without such an ad hoc postulate to justify morality. Instead, the absolute world spirit (= God) stands for Hegel theoretically and historically at the beginning of his dialectical system. In doing so, Hegel turns the antinomic misery of dialectics into a new virtue, so to speak , by developing the dialectical principle of self-contradiction into a method of his own.

Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Feuerbach advocated the following theses in The Essence of Christianity from 1841:

- Religion is not just a historical or transcendent fact, but above all an achievement of human consciousness, that is, of imagination or fantasy.

- All religions differ only in form, but they have one thing in common: They reflect the unmet needs of human nature . God and all religious contents are nothing more than psychological projections that have their material causes in human nature.

Feuerbach's starting point for deriving his theses was human nature. For Feuerbach it was essential that people have needs and desires and that these remain unfulfilled in certain respects because people - as we would say today - are defective. This is its anthropological core, which Marx largely adopts. From Hegel, Feuerbach took over the idealistic view that it is consciousness and its achievements that determine its practice. For Feuerbach, the focus was on the human imagination. It is now the unattainable and continuously unfulfilled needs that man project into a religious realm with the help of his imagination. According to Feuerbach, the religious contents refer to the unfulfilled needs and thus to the human nature, which is experienced as imperfect. In his main work he tries to show this using the terms love, finitude, mortality, injustice: the religious conception of the immortality of the soul is a reflex on the imperfect nature of man as a mortal being, the all-goodness of God a reflex on the impossibility of to love all people equally, etc.

Feuerbach's theory of criticism of religion was later and is discussed today in connection with the term "religious anthropomorphism " or " anthropocentrism " or under the catchphrase " projection theory ". They can be summarized by the following mottos:

"Man created God in his own image."

or:

"Homo homini Deus est"

"Man is a god to man."

According to Feuerbach, the explanation of religion has to start with man, derive it from him and relate it to him again:

"[...] Man is the beginning of religion, man is the center of religion, man is the end of religion."

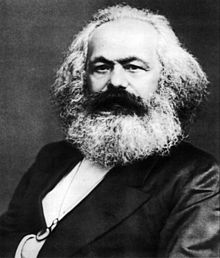

Karl Marx

Marx's criticism of Feuerbach - "socialized" religiosity

Marx's criticism of religion can be found primarily in two relevant works / texts:

- On the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right (1843/44)

- Theses on Feuerbach from 1845 (published in an edited version by Engels in 1888)

Marx adopts Feuerbach's projection theory. For him, too, the world of religion is not an ontological category, but belongs to the realm of human activity. For him, too, religion reflects a need, and for him too, religion is the reflection of a reality and not something transcendent .

However, Marx criticizes an essential lack of Feuerbach's criticism of religion: Feuerbach pretends that every human being produces his religion as an individual or as an abstract being, whereas - according to Marx - human beings primarily as a concrete, practical and thus always socialized (social) being to understand is:

“Feuerbach dissolves the religious being into the human being. But the human being is not an abstraction inherent in the single individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of social conditions. "

And that is precisely why religion does not reflect any abstract, individual needs, but concrete social needs of people.

In addition to this theory of socialized religiosity , Marx criticizes Feuerbach for the fact that the new anthropocentric interpretation of religion is not yet done:

“The philosophers have only interpreted the world in different ways; it depends on changing it. "

This thesis should say that from the point of view of practice - and according to Marx this is "objective activity" (= work as the changing appropriation of nature) - Feuerbach's theory only doubles the world into a religious world and thus explains religion, but does not ask what this means in practice for believers and social conditions. And it is precisely here that religion, according to Marx, has its practical task: it prevents changing practice because it comforts and obscures people with the idea of a perfect heavenly kingdom detached from and independent from the earth kingdom . Marx's battle cry that religion is “the opium of the people ” also relates to this . (in: On the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right ).

Marx's theory of alienation as a criticism of religion

According to Marx's criticism of ideology , religion reflects not only unfulfilled abstract needs, but also concrete social misery and injustice that runs through the whole of human history. However, they do this in a distorted form: This distortion consists on the one hand in a reversal or twisting of real conditions and on the other hand in a complete abstraction from everyday life, which leads to people fleeing into a "foggy region". For example, God, as the all-righteous, all-powerful and all-good, faces a world of unequal distribution of power, goods and love.

The starting point for Marx's criticism is the theory of self- alienation : "Alienation" is the general term used to describe the process and result of the loss of man's influence and power of disposal on and over everything that he once did through himself and thus trusts him directly which, however, ultimately confronts him as something independent and alien. Thus, a wage worker who is alienated from his work - according to Marx - no longer has any influence on the work product and the work process, although he is constantly in it. That is why the work process and the work product confront it as something alien (see Marx: Frühschriften). In religious self-alienation, people experience their needs on the one hand as things that can be fulfilled and fulfilled, but on the other hand as in principle or sometimes unfulfillable or unfulfilled. In relation to people, religion gradually becomes something independent, independent and alien to them. This is what is meant by religious self-alienation: In religion, the unfulfilled needs become independent because the latter lead a life of their own.

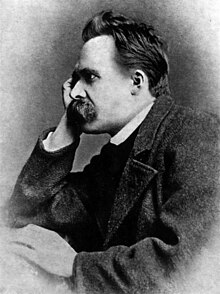

Friedrich Nietzsche

Atheism as an instinct - "God is a rough answer"

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), son of a Protestant pastor and raised Christian, called God “a far too extreme hypothesis”. He considered the Christian conception of God refuted and outdated (“ God is dead ”). There is little doubt that Nietzsche himself did not believe in any metaphysical God:

“I don't know atheism as a result, much less as an event: I understand it by instinct. I am too curious, too questionable , too cocky, to put up with a rough answer. God is a rough answer, an undelicacy against us thinkers - basically just a rough prohibition against us: you shouldn't think! "

However, this is not the focus of his argument. Rather, Nietzsche's atheism is a prerequisite for a radical criticism of (Christian) morality . He saw such a " slave morality " as a hindrance to the elevation of man to a new greatness. This criticism of Christian morality is characterized by numerous polemical and invective statements by Nietzsche ("What was the greatest objection to Dasein so far? God [...]"), but is shown above all in a historical-scientific ( Zur Genealogy of Morals ) and philosophical examination of the concept and purpose of morality (especially Dawn. Thoughts on moral prejudice and the happy science ). It is characteristic of Nietzsche's atheism that he does not generally oppose the postulate of higher values, but initially only against those of Christian morality, but finally against the values of all morality, insofar as they weaken instinctual certainty and the biological “will to power”. Nietzsche therefore turns against any morality that says “no” to life. In his opinion, however, this was the case to a greater or lesser extent with the moral teachings of all previous philosophies and religions - although these should be "instruments in the service of growing life".

- No to saying yes and amen - "revaluation of all values"

Nietzsche consequently called himself the “first immoralist” and thus describes an attitude of consciously renouncing any connection to a metaphysical order and truth. In Also Spoke Zarathustra he tried, consciously echoing the style of the Bible, to concretize the "good news" of the " superman " (ie a morality that is in the service of life).

“The psychological problem in the Zarathustra type is how he who says no, does no to an unprecedented degree , to everything to which one said yes up to now, can nevertheless be the opposite of a mind that says no ; how the spirit bearing the heaviest of fate, a fateful task can still be the easiest and most otherworldly - Zarathustra is a dancer -; like the one who has the hardest, the most terrible insight into reality, who has thought the 'most profound thought', despite not finding any objection to existence in it, not even to its eternal return , - rather, one more reason, the eternal yes To be oneself to all things , 'saying the immensely unlimited yes and amen'. "

Nietzsche's atheism is not just a nihilistic drive to devalue culture, in Nietzsche's own view it is precisely the opposite. Nietzsche criticizes morality and does not hide his aversion to Christian ideals, but he wanted to incorporate this devaluation into his program of " revaluing all values ", which ultimately serves the goal of creating new values. The type Zarathustra should be something like the first prophet of this new “yes-saying morality” , which stands in the service of life instead of preventing it from its free development.

- No to belief in gods - "human contemplation"

Nietzsche's atheism is therefore a necessary intermediate product which, in the process of “revaluing values”, is supposed to prepare the ground for a “self-reflection of humanity”, which ultimately leads to an affirmative, cheerful morality. Atheism here means the rejection of metaphysical order and the negation of the associated belief in God. In doing so, Nietzsche grants some types of belief in gods - without considering them to be "true" - a useful or aesthetically pleasing function. In Der Antichrist he describes a "healthy", harmless belief in gods as follows:

“A people who still believe in themselves also have their own God. In him it worships the conditions by which it is on top, its virtues, - it projects its pleasure in itself, its feeling of power into a being, whom one can thank for it. He who is rich wants to give up; a proud people needs a god in order to sacrifice [...] Religion, within such conditions, is a form of gratitude. You are grateful for yourself: for that you need a God. "

Consequently, it is also conclusive why Nietzsche repeatedly contrasts the Judeo-Christian concept of God ("nihilistic" in his usage) with the concept of a violent Dionysian God. It is not belief in God itself that is harmful, but belief in a metaphysical God on the other side . Nietzsche's attacks against the widespread concept of God are thus integrated into a much more far-reaching criticism of culture and religion and thus go beyond mere atheism. In fact, in many places Nietzsche is also directed against what he thinks are too simple or inconsistent forms of atheism.

20th and 21st centuries

Psychoanalysis

Sigmund Freud , the founder of psychoanalysis , has tried several times to explain the emergence of religions (and many other phenomena) as the fulfillment of unconscious, also suppressed human desires in an interpretation of natural history. Freud used the similarities between cultic-religious acts and the course of action of neurotic obsession as a basis. In his book Totem und Tabu (1913) he comes to the conclusion: "Illusions, fulfillments of the oldest and strongest, most urgent desires of mankind" are just the ideas of religion. The derivations, in which both the Darwinian “primal horde” and the Oedipus complex are used, are considered speculative. In a generalized form, namely that religions do pretend to fulfill strong conscious as well as unconscious wishes and longings of people, Freud's thesis is undisputed. Freud's relevant monograph on the subject is The Future of an Illusion (1927).

According to Freud, parents offer the child indispensable protection and a moral framework for orientation. From the child's point of view, the parents are able to do superhuman things. As the child gets older, he or she realizes that even parents cannot always offer protection and advice. In this way the child transmits the abilities ascribed to the parents to God. So instead of giving up the idea that one is always secure and advised in the world ( reality principle ), one continues to hold on to the illusion. God replaces parents in their role of protection and morality.

Even if Freud's conclusions do not directly refute theism, they do offer certain starting points for explaining religious phenomena in terms of psychological processes and for negating the need to assume supernatural powers.

existentialism

There is no existentialist atheism in the true sense of the word , since existentialism is not a closed system of teaching and very disparate ideological, philosophical and even theological concepts are brought together under this term. They range from Stirner to Schopenhauer , Kierkegaard , Heidegger , Camus to Sartre and Jaspers .

If one takes Sartre's existentialism as a reference point, the following atheistic view emerges: The most important existentialist principle of Sartre can be found in his well-known sentence, according to which the (human) existence precedes the essence (the being). There is no being (here understood both personally as God and abstractly as the nature of man) according to which and by what means man was conceived. Since man is “ nothing ” at the beginning and is constantly designing himself, God means someone who has conceived something like human nature, a limitation of this constitutive self-design. Instead, according to the existentialists, man is condemned to absolute freedom from the start . For the neo-existentialists of the Sartre school, God is first of all that which limits the absolute freedom of man.

"If God did not exist, anything would be allowed," wrote Dostoevsky . From an existentialist perspective one would add: “And because he does not exist, man is condemned to responsibility.” How is that to be understood? If God existed there would be something that preceded human existence that he could invoke as a ground for his actions. If this reason disappears, the person is absolutely abandoned and must completely draw the reasons for his actions from himself. Only now, when in principle everything is allowed, is he as an individual fully responsible for his actions according to the neo-existentialist view. For neo-existentialists, only a world (more precisely: an existence) without God enables the true responsibility of man.

The neo-existentialist view (Sartre, Camus) adopts Heidegger's concept of existence ( being and time ) for existence. Accordingly, three things are characteristic of human existence: the thrownness, the draft and the decay. Thrownness is essential for the atheistic attitude of the neo-existentialists: Man is not an image of an idea, a model or a blueprint, but is thrown into the world as a tabula rasa .

The atheism concept of neo-existentialism is not only about the rejection of a personal God to whom people have to answer, but also about all concepts that appear as theories of the “nature of man”: be it society (man as a social being ), be it economics (the homo oeconomicus) or be it anthropological concepts (man as man's wolf, as egoist) - they are all rejected by existentialism with the reference that they only render the person responsible because of this so that external, factual constraints can point to him. Existentialist atheism can thus also be understood as an attempt to rebel against the constraints of modern societies, which the neo-existentialists, especially Sartre, did in the course of the student revolts in France in 1968.

Analytical philosophy

- Logical-empirical critique of metaphysics

In large parts of the analytical philosophy developed in the 20th century, questions about the existence or non-existence of gods and metaphysical questions were initially viewed as nonsensical, untreatable, or irrelevant. Thus, in the context of logical positivism talk about gods held pointless because sentences in which these terms occur, not capable of truth are (i. E. Not be true or false can ). However, it does not claim that there are no gods. Rather, the sentence “There are no gods” is also viewed as devoid of content - just as every sentence about God or other metaphysical objects “has no meaning” but is a “pseudo-sentence” (for example Rudolf Carnap ). According to Max Bense , one of the most prominent representatives of this position in the German-speaking world at the time, a sentence like "God is transcendent" only says "from an indefinite something (x) an indefinite predicate (is pectable)".

- Epistemological Debates

When it comes to questions of existence, some epistemologists always see the person who asserts the existence of a thing in the burden of proof, here the theist. As long as this has not provided the obligation to give reasons, it is rationally justified to assume a non-existence, especially since the explanation of the world does not require a God hypothesis.

- Inconsistency of divine qualities

Since the beginning of systematic-theological debates, there has been a dispute about the compatibility of divine properties such as omnipotence, all-goodness, justice, simplicity, infinity, etc. This is also the case in recent analytical theology. A typical demonstration with the intended consequence of the non-existence of God has the form of a contradiction proof based on the assumption of existence and the usual statements about properties about God. If the properties ascribed to God are semantically absurd or logically contradictory (such as in the so-called omnipotence paradox ), then that God cannot exist.

- Theodicy

One of the oldest arguments in terms of the history of ideas that suggest the non-existence of God because of incompatibilities of assumed divine properties on the one hand and empirical findings on the other, is the argument that God's omnipotence and all-goodness are not compatible with the apparent existence of avoidable evils. (See in detail the main article Theodicy ).

Natural sciences

Opinions

- Scientific and neurophysiological arguments

Atheism based on empirical considerations: The American physicist Victor Stenger is of the opinion that not only is there a lack of empirical evidence for the God hypothesis, but that the properties often attributed to gods can also be challenged on the basis of scientific findings. Thus the creation of living beings through the theory of evolution , body-soul dualism and immortality through neurology , the effect of prayers through double-blind studies , the creation of the universe through thermodynamic and quantum physical considerations and divine revelations through the science of history have been refuted. The universe behaves exactly as it would be expected in the absence of a god.