Fukushima nuclear disaster

As Fukushima nuclear disaster a number of catastrophic accidents and severe accidents in Japan are Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant ( Fukushima I ) and their effects referred.

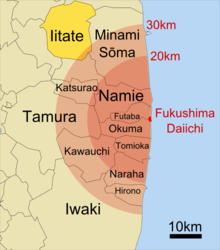

The series of accidents began on March 11, 2011 at 2:47 pm (local time) with the Tōhoku earthquake and ran simultaneously in four of six reactor blocks . Core meltdowns occurred in Units 1 to 3 . Large amounts of radioactive material - about 10 to 20 percent of the radioactive emissions of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster - were released and contaminated air, soil, water and food in the agricultural and sea side environment. Around 100,000 to 150,000 residents had to leave the area temporarily or permanently. Hundreds of thousands of animals left on farms starved to death. However, no human deaths from exposure to radiation were known.

On the basis of an estimate of the total radioactivity of the released substances , the Japanese nuclear regulatory authority classified the events on the international rating scale for nuclear events with the highest level 7 ("catastrophic accident").

Four out of six reactor blocks in the power plant were destroyed by the accidents. According to a statement by the Japanese government on March 20, 2011, the power plant is to be completely abandoned. Since December 2013, the IAEA has listed all six reactors of the power plant as "permanently shut down". The disposal work is expected to take 30 to 40 years.

Reporting on the disaster led in many countries to greater skepticism or a change in sentiment at the expense of civilian use of nuclear energy . Several countries gave up their nuclear energy programs.

Sources of information

Most of the information available about what is happening on the power plant site comes directly or indirectly from the operating company Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco). They were published partly directly by Tepco on the Internet and at press conferences, partly via regular reports or press conferences of the Japanese nuclear supervisory authority (NISA), the higher-level Ministry of Economic Affairs ( METI ) and the government spokesman . The Japanese government was involved in the crisis management team at the Tepco company headquarters. The NISA was on site with its own experts who, however, did not take any measurements, only checked the information provided by the operator for plausibility.

The Japanese Nuclear Industry Forum (JAIF) published status reports on its website several times a day on the situation in the power plant and on other events in connection with the accidents.

The few publicly available information from the power plant site that is independent of Tepco includes recordings and measurements made from outside, for example aerial photographs and satellite images, other photo and video recordings and radiation measurement data from unmanned US reconnaissance aircraft. There are also reports from employees at the power plant.

Measured values from various sources are available from the wider area in Japan, for example from government agencies such as the Japanese Ministry of Culture and Technology (MEXT), the Ministry of Health (MHLW) and the disaster control command established after the nuclear emergency was declared, from regional authorities and organizations, by private individuals and by international observers.

The German Society for Plant and Reactor Safety (GRS) collects and evaluates information on the accidents on behalf of the Federal Environment Ministry and relies on the sources mentioned above. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and many other specialist organizations and publications also evaluate the data from Japan and report on them regularly.

Organizations around the world such as the IAEA, the Organization of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBTO) and the Environmental Protection Agency published data from their sensitive measuring points on the spread of radioactive particles from Fukushima .

Tepco, the Japanese government, the IAEA and a commission of experts set up by the Kan government published the first detailed investigative reports.

Construction of the power plant

The Fukushima I nuclear power plant consists of six reactor blocks, each with a boiling water reactor . In addition to the nuclear reactor , each reactor building also has a cooling pool for the interim storage of spent fuel elements . There is also a larger, central cooling pool and a dry fuel storage facility with special containers on the power plant site. A further building is attached to each reactor building, in which the turbines and generators for generating electricity as well as the inlets and outlets for cooling water from the sea are located.

Reactors and cooling pools must be continuously cooled, even when they are switched off. In used or "burned off" elements, atoms with a short half-life that were created during nuclear fission ( fission products ) continue to decay . This releases heat ( decay heat ) that would destroy the fuel elements without adequate cooling. In each reactor block there are therefore several cooling circuits that are also designed redundantly .

Sequence of accidents in the power plant

Starting position

Before the accidents, there were indications of the risks of the reactor types used and construction defects of the plant in Fukushima Daiichi , inadequate protection against earthquakes and tsunamis, and inadequate control and maintenance . Tepco and the Japanese nuclear regulators ignored most of this advice.

At the time of the quake, reactor units 1, 2 and 3 were in operation. Reactor unit 4 has been out of operation since November 30, 2010 due to a major overhaul; the fuel elements in this unit were therefore completely stored in the associated decay pool at the time of the accident. Units 5 and 6 were shut down on January 3, 2011 and August 14, 2010, respectively, and were re-equipped with fuel assemblies as part of maintenance. In contrast to units 1 and 2, reactor 3 has also had mixed oxide fuel elements since August 2010 , which contain a mixture of uranium dioxide and plutonium dioxide . Each of the fuel assemblies consisted of 72 (reactor 3 differently 74) fuel rods and contained 170 to 173 kilograms of nuclear fuel .

The following number of fuel elements and the mass of nuclear fuel were located in the reactor cores, decay pool and storage pool:

| Storage location | Fuel assemblies | Cooling pool | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in the reactor core | in the cooling pool | of which unused | Estimated heat output ( kW ) |

Volume (m³) |

||||

| number | Mass (t) |

number | Mass (t) |

number | Mass (t) |

|||

| Block 1 | 400 | 68 | 392 | 67 | 100 | 17th | 180 | 1,020 |

| Block 2 | 548 | 94 | 615 | 105 | 28 | 5 | 620 | 1,425 |

| Block 3 | 548 | 94 | 566 | 97 | 52 | 9 | 540 | 1,425 |

| Block 4 | 0 | 0 | 1,535 | 263 | 204 | 35 | 2,260 | 1,425 |

| Block 5 | 548 | 94 | 994 | 171 | 48 | 8th | 1,000 | 1,425 |

| Block 6 | 764 | 132 | 940 | 162 | 64 | 11 | 870 | 1,497 |

| Central cooling pool | 6,375 | 1,093 | 1,130 | 3,828 | ||||

| total | 2,808 | 480 | 11,417 | 1,958 | 496 | 85 | 6,600 | 12,045 |

- ↑ The table shows estimates as of November 9, 2012 from a report by the Japanese authorities to the IAEA. There are various different estimates, some of them lower and some of them higher. The heat output in the cooling basins from Blocks 1 to 6 was reduced by 10–30 percent within three months.

- ↑ including 32 mixed oxide fuel elements

- ↑ estimated on the basis of an average fuel mass of 0.1715 t per fuel element

Tepco estimated the total amount of radioactive 131 I contained in the fuel rods to be 81 · 10 18 Becquerel or 81 million Terabecquerel.

In addition, there were at least 10,000 tons of contaminated water in the power plant's waste storage facility.

Accident series from March 11th to 16th

On March 11, 2011 at 14:46:23 (local time), the Tōhoku earthquake began under the seabed off the east coast of the Japanese main island of Honshū . Its epicenter was 163 kilometers northeast of the Fukushima I power plant, meaning that the primary waves (P waves) of the quake had reached the power plant site after 23 seconds. There they stimulated seismometers , which triggered a rapid shutdown of reactors 1 to 3. At the same time, the power plant's external power supply failed due to earthquake damage to its switchgear , and twelve of thirteen emergency diesel generators started (one at Block 4 was being serviced).

The quake lasted about two minutes and reached a magnitude of 9.0 M w . It shook reactor blocks 2, 3 and 5 with horizontal accelerations of 0.52 to 0.56 g , 15 to 26 percent more than assumed when the blocks were designed. The planned load limits of the other reactors were not reached; nevertheless there are indications of earthquake damage in block 1 . In Block 3, a reserve emergency cooling system was probably damaged.

All six blocks switched to emergency cooling.

From 3:35 p.m., tsunami waves with a height of approximately 13 to 15 meters hit the power plant. According to the IAEA, Fukushima I was not connected to the existing tsunami warning system, so that the operating personnel did not receive an early warning, while NISA speaks of an alarm immediately after the earthquake. There was only a 5.70 meter high protective wall for the sea-side part of the site; only 3.12 meters were required. The reactor blocks 1 to 4, which are 10 meters above sea level, were flooded up to 5 meters deep; the three meters higher built blocks 5 and 6 up to one meter. The seawater pumps positioned on the coast were destroyed; Waste heat could no longer be released into the sea water, which ran into various buildings and flooded five of the twelve running emergency power generators and most of the power distribution cabinets. The power plant operator Tepco reported that the generators failed at 3:41 p.m. A generator in Block 6 survived the tsunami because it was housed in a separate, higher building.

400 Tepco employees were mobilized for emergency operations - according to the IAEA far too few for a catastrophe of this magnitude. External companies such as power plant manufacturers Toshiba and Hitachi withdrew their employees. Simultaneous accidents in several blocks were not included in the emergency plan. Alluvial debris, puddles of water, road damage and inoperable door and gate openers hindered further work. Most of the communication facilities were down. There was a constant risk of aftershocks and further tsunamis.

Due to the failure of the power supply ( blackfall or station blackout ), sufficient cooling was no longer guaranteed to dissipate the decay heat from the reactor cores and cooling basins. With the existing emergency batteries, the emergency cooling systems could only be operated briefly (see section Problems in reactors 1 to 3 ). Additional generator vehicles that were brought in became active too late to stop the series of accidents due to traffic jams, blocked access routes, flooded connection points and cables that were too short. Only in blocks 5 and 6 could the power supply be restored in good time by the still functional generator. In Blocks 1 through 3, workers tried, with varying degrees of success, to connect car batteries and portable power generators to individual systems.

A lack of cooling, partly due to other technical and organizational problems, resulted in overheating of the reactors and cooling pool, the release of hydrogen into the reactor buildings and core meltdowns in reactors 1 to 3 (see sections Problems in Reactors 1 to 3 and Problems in the cooling pool ). Through targeted pressure relief of the reactors radioactive substances got into the environment and were distributed further in different directions by changing winds.

From March 12 to 15, there were explosions - probably hydrogen explosions - in units 1, 3 and 4, some of which severely damaged the reactor buildings and set the rescue work back. Highly radioactive rubble was hurled onto the power plant site. In Block 2 the containment of the reactor was damaged, so that extremely highly contaminated water escaped (see also section sea water channels ); Several fires broke out in Block 4. From March 13th to 15th, neutron radiation was measured several times on the power plant site , which indicated an uncontrolled restart of nuclear fission ( criticality ) in one of the reactors or decay basins.

The plant fire brigade pumped water into reactors 1 to 3 in order to cool them down, first from existing fresh water reserves and then from pits in which seawater had accumulated. Prime Minister Naoto Kan gave permission to discharge seawater - this will damage the reactors - on March 12, 2011 at 7:55 pm.

During the depressurization, explosions and fires, the radiation exposure on the site rose sharply (see graphic). On March 14th, Tepco considered giving up the power plant and withdrawing all employees because of the excessive radiation risks, but did not receive permission from the Prime Minister. As a result, on March 15, all but around 50 Tepco employees - also referred to in the media as " Fukushima 50 " - as well as 130 other workers and helpers from external companies, the fire service and the armed forces were temporarily evacuated. A few days later, 140 helpers from the Tokyo fire department joined them, who, according to Governor Shintarō Ishihara , were forced to do this by Minister of Economic Affairs Banri Kaieda . Work in the control rooms of the power plant has only been possible to a limited extent since the explosions because the employees were constantly exposed to high levels of radiation and there was only inadequate emergency lighting since the power failure.

Stabilization measures

The decay basins of reactor blocks 3 and 4 as well as the central decay basin were provisionally cooled with water cannons of the Japanese armed forces and the fire department from March 17, 20 and 21 respectively ; Later truck- mounted concrete pumps were used for cooling in units 1, 3 and 4. The fire service pumps for cooling the reactor were also replaced by more powerful devices. Starting from a neighboring high-voltage line, new power lines were laid to the power plant in order to be able to reconnect the electrical systems - if they were still functional - to the power grid. Above all, they hoped to be able to put the cooling systems back into operation. Reactor units 5 and 6 returned to a stable operating condition on March 20 after their emergency power supply had been restored. On the same day, blocks 1 and 2 were reconnected to the power grid, and all other blocks were also connected by March 22nd. The lighting in the control rooms was then restored, but most of the other systems were found to be inoperable or flooded.

The state of reactors 1 and 3 was still unstable at this point in time. In block 3 there was an increase in pressure and unexpected smoke development; the site was once again briefly evacuated. In reactor 1, the cooling caused problems (see here for details ), which continued in April; the activity of the reactor core increased several times. From blocks 2 to 4 steam or smoke rose again and again, from March 25th from all three (as of April 15th). Overpressure, core meltdown and sea water had damaged the pressure and containment vessels of reactors 1 to 3, so that contaminated steam and cooling water were constantly escaping.

From March 25th, the cooling of all reactors and cooling basins was gradually switched from sea to fresh water, above all to avoid further damage from salt deposits. Reactor 1 now held an estimated 26 tons of sea salt, and larger reactors 2 and 3 45 tons each. The freshwater was initially supplied by United States Navy barges, which were pulled or pushed by ships of the Japanese armed forces; It was later taken from a reservoir ten kilometers away via a pipeline .

At the end of March, the Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire estimated the heat output of the fuel elements in reactor 1 to be 2.5 megawatts and in reactors 2 and 3 to 4.2 megawatts. This output would be sufficient to allow 95 or 160 tons of water to evaporate per day, and would require continuous cooling with around 150 to 200 tons of water per reactor and day (see the section on quantities of cooling water fed in ). Because of the severely damaged fuel elements in the reactor cores, this water was and is highly radioactive contaminated. Parts of it evaporate and, depending on the weather, can be seen as white vapor clouds over the reactor blocks. The rest will initially remain on the power plant site.

By April 4, 2011, around 60,000 tons of radioactive water had accumulated in this way in the basement of the turbine building, in adjoining shafts and maintenance tunnels running towards the sea, and on other areas. The ground of the site was soaked with radioactive water that it penetrated into the buildings of reactor units 5 and 6, one kilometer away. These masses of radioactive wastewater became an increasing problem. They prevented work on electrical systems that were under water, endangered the workers and ended up in the sea in various ways (→ see Contamination of seawater by the nuclear accidents in Fukushima ).

First safety measures

Various measures to curb radioactive emissions and dispose of waste were discussed early on . This included building a “sarcophagus” like in Chernobyl , covering the reactor blocks with a special fabric , spraying the site with synthetic resin and treating radioactive wastewater with the Russian special ship Landisch ( Suzuran in Japanese ).

The first actually implemented measure was to bind radioactive dusts with synthetic resin. It began on April 6th on small trial areas and was later expanded to an area of half a square kilometer, one seventh of the power plant site. The buildings were also sprayed.

In order to create space for the storage of the contaminated wastewater, Tepco pumped around 10,000 tons of contaminated water from the waste storage facility (approx. 30,000 tons total capacity) with a radioactivity of 150 billion Becquerel (0.15 TBq) from April 4th to 10th Sea. There were protests by Japanese fishermen and the neighboring countries of South Korea, Russia and China. Then they began to pump water from the cellars and tunnels of the turbine buildings into the waste storage and later also into separate tanks, although progress was slow. Tepco commissioned the French nuclear technology group Areva to build a plant that can decontaminate 1,200 tons of wastewater per day on site.

The company Toshiba , the more of the reactors at Fukushima Daiichi had built and also at the disposal work after the accident at Three Mile Iceland was involved, Tepco submitted a bid for safety works at the power plant. Within 10 years Toshiba wants to remove all fuel rods from the power plant site, demolish various plants and reduce the contamination of the soil.

From April 10th, Tepco cleared away the radioactive waste that had been distributed on the power plant site by the explosions of units 1 and 3 with unmanned special vehicles - several dozen cubic meters of rubble per day. This work should continue until summer 2012.

In November 2011, the HAL (robot suit) was selected to carry out clean-up operations on the terrain of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. During the "Japan Robot Week exhibition" (German: "Messe Japanische Roboterwoche") in Tokyo in October 2012, a revised version of HAL was presented, which had been specially developed for the clean-up work in Fukushima.

Further measures served to contain the discharge of sewage into the sea. In addition to sealing manholes and pipes with water glass (see section wastewater discharge into the sea ), Tepco had a steel wall built at the water inlet of reactor block 2 and silt curtains put up at various points. In addition, floating barriers were used to hold back radioactive suspended matter and sandbags were piled up on the south pier of the power plant. Sacks with zeolites deposited at the exit points were supposed to bind radionuclides in the water. The measures were successful: emissions into the sea had fallen to a fraction by the end of April. The measured values on the northern and southern edge of the power plant site (see also the section on radiation exposure at the power plant ) now only showed that the limit values were exceeded slightly.

For temporary protection of the power plant from possible further tsunamis a twelve-meter-high dam was gabions built.

Situation determination

May brought clarifications to the sequence of the series of accidents and the condition of the power plant. First, the inside of the reactor building was explored. Because of the high levels of radiation in the buildings, this task was performed by PackBot robots that Idaho National Laboratory had converted for this purpose. The approximately one meter high devices could only be used to a limited extent due to the explosive debris in the way, but they provided valuable information about the radiation exposure in various parts of the building. The measured values in block 1 ranged from around 10 to 1000 millisieverts per hour. Various other robot models and remote-controlled special devices were later used, also on the other power plant premises.

Next, the air in the buildings was decontaminated so that workers with appropriate protective equipment could also work there (in some areas). The newly acquired information, together with data records from the control rooms and additional computer-aided analyzes, provided a picture of the condition of reactors 1 to 3. In all three the nuclear fuel rods were largely melted ("melt-down") and the melt had damaged the pressure vessel. The containment was also leaky, which the NISA - which had already confirmed a core meltdown in all three reactors on April 18 - explained that parts of the melt had leaked into the containment ("melt-through"). The cooling water leaked out of the reactors through the leaky container. At the beginning of 2017, a one-square-meter hole was found in the maintenance grille under the pressure vessel of reactor 2, presumably melted by hot material from the fuel elements. It has not yet been possible to determine whether the security container is also damaged.

The entire data material with records of the reactor parameters and activity logs of the employees was published on the Internet on May 16 at the instigation of NISA. Later, NISA also published all reports from the power plant operator to the authorities.

Original plans to quickly stabilize the cooling of the reactors with closed water cycles and to get the release of radioactive substances under control were no longer necessary due to the reactor damage. This also exacerbated the wastewater problem. With provisional measures such as the concreting of manholes and tunnels and the temporary storage of contaminated water in various buildings, which were actually not intended for this and sometimes leaked, Tepco saved itself over time - with the approval of NISA.

In the meantime there were technical problems and incidents, for example a critical temperature rise in reactor 3, a failure of the cooling in block 5 and a power failure in blocks 1 and 2.

The number of people on the power plant site increased steadily. After exceeding 1000 in early May, it was already 2500 in mid-June.

Medium-term stabilization

As a more permanent solution to the wastewater problem, the new decontamination system went into operation in June with four treatment stages:

- Oil separator

- multi-stage cesium filter with zeolites

- Replica of a chemical-physical decontamination system at the La Hague reprocessing plant

- osmotic desalination

The system reduces the radioactivity of the water to a 100,000th and produces highly radioactive sludge, which remains on the power plant site until a decision is made about final disposal . The decontaminated water is partly stored in newly built tanks and partly reused as cooling water for the reactors.

| Week from | metric tons | Plant utilization |

|---|---|---|

| June 29th | 6380 | 76% |

| July 6th | 6130 | 73% |

| July 13th | 4510 | 54% |

| 20th of July | 4870 | 58% |

| July 27th | 6190 | 74% |

| 3rd August | 6720 | 80% |

| August 10 | 7420 | 88% |

At the beginning of June, Tepco estimated the total amount of wastewater that had already accumulated at around 100,000 tons, with a radioactivity of 720,000 terabecquerels - about as much as was released into the air during the "hot phase" of the accidents. The inflow of new wastewater at that time was several hundred tons per day. The decontamination costs were estimated at the equivalent of 1,800 euros per ton.

Instead of the planned 50 tons of flow per hour, the system initially only achieved around 25 to 35 tons. There were regular breakdowns and business interruptions.

A second, more reliable zeolite filter system took over the decontamination of the water that had collected in the sealed off area in front of the power station.

The containment of reactors 1 to 3 was filled with nitrogen in order to prevent possible oxyhydrogen explosions. The cooling basins received new, closed cooling circuits. This allowed the water temperatures to be reduced and corrosive sea salt residues to be filtered out. The concrete pumps went out of service.

The wastewater level in the various buildings remained almost unchanged for months: inflow from cooling water and rain and outflow from treatment and storage in new tanks were balanced. Overflow could be prevented.

In order to increase the processing capacity, the (first) decontamination facility was expanded in August by an additional zeolite filter system built by Toshiba . This made it possible to gradually lower the water levels in the following months. A total of around 130,000 tons of water had been processed by mid-October. Further breakdowns, leaks and downtimes occurred during operation, up to and including the leakage of “at least 45” tons of highly radioactive strontium-contaminated water (175 million Becquerel per liter) in December. Up to 150 liters of it ran into the sea.

Since October 2011, the temperature of all reactors has been below 100 ° C. This state is stable as long as the cooling water supply is not interrupted for more than 18 hours. Japan's new Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda said on December 16th 2011, the power plant is - as planned - stable shut down ( cold shutdown, cold shutdown ). The NISA had previously confirmed that the cooling was ensured by redundant systems, although Tepco sees a ten times higher risk of failure with the provisional cooling systems than in the normal state. Critics doubt that one can speak of a cold shutdown if the state of the reactor core is unclear.

Long-term coverage

By mid-2013, Tepco had put in an additional steel wall directly in front of the power plant. It was driven deep into the sea floor in order to contain the leakage of contaminated “underground water” for the next 30 years. However, the steel wall does not seem to prevent contamination of the groundwater.

According to the Japanese government, the plan was to remove the fuel assemblies from the spent fuel pools in reactor units 1 to 4 and store them in the remaining spent fuel pools. In 2013, the recovery of around 1,500 fuel rods began. The salvage work in reactor block 4 was completed in 2014. In the other reactor blocks, however, the situation is much more complicated, as rubble first had to be cleared out of the way. The containment of reactors 1 to 3 is to be repaired and filled with water by 2021 and the remains of the reactor cores are to be removed by 2025 . The four blocks are then to be completely torn down. The work should be completed within 30 to 40 years. The evacuation of the fuel from the reactors should be completed by around 2031.

Process in the individual systems

Problems in reactors 1 to 3

After the rapid shutdown of the reactors, the steam and water circuits to the turbines were also interrupted (see lines no. 6 and 7 in the graphic on the right); thus the main heat sink of the reactors was lost as planned. The decay heat absorbed by the evaporating water in the reactors was then dissipated into water-filled condensation chambers, which served as a substitute heat sink. In blocks 2 and 3, this was the large condensation chamber under the reactor (No. 24 in the second graphic), which was cooled indirectly with seawater (RHR system). Various emergency cooling systems were used in the differently structured Block 1.

Less than an hour later, the emergency power generators failed, and with it the electrically operated pumps for the cooling systems of reactor blocks 2 and 3. It was no longer possible to dissipate heat from the reactor condensation chambers and the cooling basins into the sea. The direct cooling of the reactor cores was now carried out with steam-driven pumps (RCIC), whose use is only intended for a limited period of time. A power supply is only required to control the pumps and to control valves. This was possible for a short time in blocks 2 and 3 with emergency batteries until they failed or the cooling system failed for other reasons. In Block 1, the emergency cooling probably already failed due to the tsunami flooding. The diesel-powered pumps of the fire extinguishing system, which could be used as a last emergency measure, could not be used for various reasons or were operated incorrectly. No more fresh cooling water was injected into the reactors and the water still present evaporated. As a result, the water level sank and the reactor fuel rods were initially partially surrounded by water, later not at all, which caused them to heat up further due to the decay heat.

The shells of the fuel rods are made of a zirconium alloy called Zirkalloy . At temperatures above around 800 ° C, the zirconium reacts with the surrounding water vapor to form zirconium oxide and hydrogen . The considerable heat development associated with the oxidation process drives it further ( exothermic reaction ). From around 1200 ° C, the oxidation of the zirconium increases dramatically.

At temperatures above around 900 ° C, the cladding tubes of the fuel rods begin to burst due to the internal gas pressure . This releases radioactive gases and particles of the fuel, including the isotopes 131 I and 129 I, the other fission products 137 Cs , 134 Cs and 90 Sr as well as the brood product 239 Pu . The zircalloy melts above around 1750 ° C, flows together with dissolved uranium oxide from the fuel rods to the bottom of the pressure vessel and is deposited there as so-called corium - a core meltdown has begun. From 2850 ° C, the uranium oxide in the fuel rods also melts and, together with the melted control rods, forms further “corium”. In all three affected reactors, the fuel rods were without cooling for so long that these processes took place and most of the reactor core melted.

Since the reactor pressure vessels were locked after the emergency power failure, the pressure rose to the intended maximum values due to water evaporation and hydrogen production. Safety valves opened automatically and released parts of the steam-hydrogen- radionuclide mixture into the safety containers. Later, the pressure vessels were also manually relieved in order to be able to pump in water.

There was also no longer any possibility of cooling in the security containers, and the pressure there also rose. However, it stabilized at around 750 (reactor 1 and 2) and 500 (reactor 3) kilopascal (see graphic). Presumably at this pressure the seals of the containment failed, so that no higher pressure could build up, but the steam-hydrogen mixture escaped into the reactor building. In order to reduce the pressure and to prevent rupture of the containment portions of remaining in the containment vessels contaminated with radionuclides gases were eventually discharged into the environment ( venting ). It was later suggested that the venting had not worked properly because of undersized pipes or pipes that were broken by the earthquake or because of a lack of power supply, and that this was how the gas got into the building envelope. After most of the pressure relief operations, however, significant radioactive emissions were measured outside the reactor buildings.

After a sufficient amount of hydrogen had accumulated, a hydrogen explosion occurred in each case, which destroyed parts of the building and parts of the technology contained therein. Meanwhile, the meltdowns continued. According to an analysis by NISA, parts of the melted reactor cores ran out of the pressure vessels, accumulated on the bottom of the containment and damaged them.

In order to cool the reactor cores and at the same time prevent an uncontrolled chain reaction , seawater mixed with boric acid was introduced into the pressure vessel. The in natural boron present to 20% isotope 10 B may consist of a nuclear fission produced neutrons absorb very efficient ( neutron absorber ) which is to lithium and helium decays. Since Japan's boron reserves were insufficient, South Korea shipped 52 tons of its boron reserves to Japan. France delivered another 95 tons.

The water was fed in via existing lines, initially with fire fighting equipment and later with more powerful electric pumps. A little more water was introduced than would have been necessary to completely dissipate the decay heat by evaporation, but due to the damage to the containers more than half of it was lost, while the rest evaporated and escaped into the environment. The leakage water partly collected in the containment; the remainder exited from there into the reactor buildings. This emergency cooling process - under more favorable circumstances it would take place without the escape of liquid water - is known as “feed and bleed” . It has the serious disadvantage that radioactive substances from the reactor core get into the environment together with the steam.

Because of the loss of water through the leaks, the remains of the reactor cores could only be partially covered with water, according to NISA; they would be cooled partly with water and partly with steam.

Problems in the cooling pool

An additional risk arose from the fact that the used fuel elements were initially stored in the reactor building and later in a central spent fuel pool for many years and are still being stored. Due to the decay heat, the stored fuel elements continue to give off energy to the pool water, which is dependent on a cooling circuit. Due to the complete power failure, this cooling circuit failed in all cooling pools, so that the water there gradually heated up and partially evaporated.

If the elements are no longer completely covered by water, there is a risk of overheating and chemical reactions similar to those in the reactor, up to and including the bursting of the fuel rods. Without cooling water and without a building roof, which was missing from three of the reactors after the explosions, the radionuclides, which are even in higher concentrations than the reactors, would be released into the environment.

Water readings from the decay basins initially indicated that such processes were taking place in Units 2 and 3, and to a lesser extent also in Unit 4. Later, Tepco and official investigative reports concluded that both the basins themselves and the fuel elements stored in them were highly likely remained intact. During normal operation, the water level in the basin is almost three times as high as the height of the stored fuel elements. This means there is enough reserve to bridge cooling failures lasting several weeks. However, a study published by the National Academy of Sciences in 2016 came to the conclusion that only an accidental leak flooded the cooling pool in Unit 4 and prevented the fuel rods from spontaneously igniting.

Reactor block 1

Unit 1 of Fukushima I was built from 1967 to 1970 and was the first nuclear power plant in Japan. It is based on an older and smaller reactor model than the other units in the plant (→ see technical data for the reactor units ) and had weaker emergency systems. The lifetime of this reactor was supposed to end in early 2011, but was extended by ten years by NISA in February 2011.

Only a relatively small number of old fuel assemblies were stored in the decay basin of Unit 1, which, in contrast to the reactor, required little cooling.

Power and cooling failure

The earthquake triggered a large number of actions in Block 1 on March 11 at 14:46:46 (local time). The reactor was automatically shut down as planned and at the same time switched to emergency power operation due to the failure of the external power supply. Workers later reported broken pipes in the reactor building, from which water gushed out. One of the emergency cooling systems (isolation condenser) switched itself on briefly and then went out of operation again. Another (Containment Cooling System) then initially cooled the containment that surrounds the reactor pressure vessel. Tepco later denied that the earthquake caused significant damage or safety problems, but had to withdraw a similar denial for Unit 3 shortly afterwards.

After the tsunami hit, the emergency generators failed at 3:37 p.m. due to flooding. All running cooling systems went out of service. The reactor data recording also no longer worked, so that only notes and memory logs of the power plant employees as well as theoretical considerations exist for the further process. The backup batteries were only available to a limited extent - if at all - due to the flooding of the electrical system, and the emergency cooling no longer worked, or only worked temporarily, despite several redundant systems. Tepco reported a cooling failure to the supervisory authority at 4:36 p.m. and then again at 5:07 p.m.

The power plant operator ordered emergency generators from other power plants to Fukushima I, but they got stuck in traffic. Then Tepco asked the energy supplier Tōhoku Denryoku for help and had generators come from its power stations; likewise from the armed forces. Replacement batteries were also requested by helicopter from a Tepco power plant in nearby Hirono that was destroyed by the earthquake . In some places they made do with car batteries and mobile generators in order to be able to read at least individual measured values.

Since the cooling failure around 5 p.m., alternative methods of introducing cooling water have also been looked for. Employees went into the dark reactor building, opened valves by hand and started the diesel-powered fire pump . It is unclear to what extent water was actually injected into the reactor. In the control room, the employees tried to use manuals and manufacturer information to find out whether and how the reactor could be depressurized in the event of a power failure.

Due to the events in Unit 1 and other problems at the neighboring Fukushima II nuclear power plant , the Japanese government declared a “nuclear emergency” at 7:03 pm and the local authorities began evacuating the surrounding area. The first mobile power generators arrived at the power plant two hours later, but could not be connected because of blocked access routes and cables that were too short.

Pressure rise, core meltdown and cooling attempt

The water in the reactor continued to evaporate and the water level fell, but due to the lack of data recording it is unclear when and how the steam escaped from the pressure vessel into the containment. Individual measurement data from the following night indicate that sooner or later this happened due to a leak in the pressure vessel or the pipelines connected to it.

The partially dry fuel elements overheated and the above-described decomposition processes began. According to later investigations, a core meltdown began around 7 p.m. to 8 p.m. The water level meter was decalibrated due to overheating . During a check at 9:19 p.m. it indicated that the reactor core was still fully covered with water. The cooling by fire pump seemed to work.

From 21 pm, the authorities allowed a computer simulation to estimate that radioactive releases at a pressure relief ( venting ) of the containment, ie when releasing steam into the environment would result. The time of venting was assumed to be 3:30 a.m. on March 12th. The system predicted that the onshore contamination would be confined to the power plant site and that the northwest wind would carry the "radioactive cloud" out to sea.

At around 1 a.m. on March 12, the pressure in the containment exceeded the maximum permissible pressure of 528 kPa by 600 kilopascals (kPa) (in each case absolute; the relative pressures to the external atmosphere are around 100 kPa lower). A few hours later it reached 840 kilopascals (kPa), but then dropped back to 750 kPa on its own. Presumably the steam escaped past the overloaded seals of the containment into the reactor building, together with the hydrogen produced in the overheated reactor core. A slight increase in radiation ( local dose rate ) was detected for the first time at a measuring station on the western edge of the site . Radiation also increased in the turbine building in Unit 1. None of those responsible was aware that hydrogen was accumulating outside the containment.

The fire pump had run out of fuel. It was not possible to put it back into operation; it was ineffective anyway at high reactor pressure.

An emergency meeting was held in the Prime Minister's office. According to government circles, Tepco was urged to relieve the pressure on the containment of reactor 1, while the power plant operator himself said it asked for permission to relieve the pressure. Either way, venting was not easily possible because the electrically and pneumatically operated valves were out of order.

The radiation at the boundary rose rapidly and was at 4:35 a.m. with 0.00038 to 0.00059 millisieverts per hour (mSv / h) at 10 to 15 times the normal value. Meanwhile 40 TEPCO workers began to manually lay a 200 meter long and one tonne power cable from the generator car to a connection point at Block 1/2.

From 5:46 am, pumps from the fire engine stationed at Block 1/2 were used to inject fresh water from existing extinguishing water cisterns into the pressure vessel in order to cool the reactor as necessary; Hydrants and the much larger pure water tanks were unusable due to tsunami damage. The high reactor pressure limited the water flow. An hour later, the Ministry of Economic Affairs instructed Tepco to manually open the pressure relief valves. The radiation measured at the boundary had meanwhile increased tenfold.

At around 7 a.m., Prime Minister Naoto Kan arrived at the power plant by helicopter - according to official statements to signal support from the population in the region, but according to newspaper information, however, to influence crisis management. Kan asked Tepco to form a "suicide squad" of workers who were supposed to undertake the manual pressure relief. There was radiation of around 300 mSv / h in the building, a level that is dangerous to the health of people even if they stay for a short time.

Critics later suspected that the depressurization of reactor 1 had been delayed by Kan's presence. At around 8 a.m. - immediately before Kan's departure - the power plant manager gave the instruction to prepare manual venting for 9 a.m.

Depressurization and explosion

At 9:03 a.m., the authorities reported that the evacuation of the city of Ōkuma , on whose territory reactor units 1 to 4 are located, had been completed. Immediately afterwards, workers equipped with protective suits, compressed air bottles and flashlights went into the reactor building. Using a portable power generator, they managed to open the first (electromotive) pressure relief valve a quarter. They gave up trying to open the second pneumatic valve on the containment because of excessive radiation.

From 10:17 a.m. onwards, attempts were made several times to operate the pneumatic valve from the control room. The sensors in the containment did not show any significant pressure drop (see graphic), but the radiation at the edge of the site temporarily increased from 0.007 to 0.39 mSv / h. At the same time, Tepco tried to find a portable compressor in order to open a more easily accessible, larger pneumatic valve elsewhere.

Around noon, the defective water level gauges indicated that the fuel rods in the reactor core were half dry, and NISA warned that a core meltdown might have started.

At around 2 p.m., the workers managed to open the second pneumatic valve using a compressor. Tepco reported at 2:30 p.m. that the pressure relief had been successful. At 2:49 p.m., radioactive cesium was detected in the vicinity of Block 1. At 3:01 p.m. the hourly updated Tepco webcam showed steam escaping from the chimney at Block 1/2 for the first time, and at 3:29 p.m. the radiation at the site boundary exceeded the permitted limit of 0.5 at 1.0 mSv / h mSv / h.

By 2:50 p.m. the fresh water supplies were exhausted. According to its own information, Tepco had made preparations to quickly switch from fresh to seawater discharge; it could have started at 3:18 p.m. However, this was delayed by several hours due to communication problems between the power plant operator, supervisory authority, government agencies and the Prime Minister and / or due to technical concerns of the Prime Minister. (A NISA report later stated that there was “no hesitation” in using seawater.) The heavy power cable was now connected to the distributor in Block 1/2.

At around 3:30 p.m., workers tried to power a pump to feed borated water into the reactor (SLC pump). At this moment, an oxyhydrogen explosion (hydrogen explosion) occurred between the containment and the outer shell of the reactor building , during which the upper part of the outer lining of the reactor block was blown away. Video recordings show a fast, barely visible explosion burst upwards and then a cloud of smoke that spreads more horizontally than vertically around the reactor building. The explosion injured four workers on site, cut the power line, which was only completed half an hour ago, and damaged prepared hoses for discharging seawater. The backup work was interrupted for two hours.

At the time of the explosion, there was a southeast wind at the power plant. A mobile radiation measuring station on the northwestern, landside boundary showed a sudden, short increase from 140 to 1015 millisieverts per hour at 3:29 p.m.

The government announced that the reactor's containment had not been damaged. Later she was surprised: no one would have informed her beforehand that the venting could result in an explosion of the reactor building. Tepco pointed out that the hydrogen is normally broken down in the containment; Nobody expected an explosion.

The Japanese authorities suspected a core meltdown from around 5 p.m. due to the increased cesium values . The authorities prepared the distribution of iodine tablets and extended the evacuation radius around the power plant to 20 kilometers.

In the meantime, all measuring instruments for the reactor condition (pressure, temperature, water level) in Block 1 had failed. Apparently the emergency batteries were now completely exhausted.

Cooling tests and power connection

At 7:04 p.m., Tepco began introducing seawater into the reactor and informed NISA. However, since no confirmation was received from the Prime Minister, Tepco decided to stop pumping water around 7:30 p.m. The manager of the power plant ignored the instruction and continued the makeshift reactor cooling. An official clearance by the Prime Minister and NISA did not take place until around 8 p.m. It was later said that the Ministry of Economic Affairs had given the permit around 6 p.m.

From 8:45 p.m., the neutron-absorbing boric acid was added to the cooling water to reduce the risk of criticality. At 10:15 p.m. the sea water cooling had to be interrupted for a few hours due to an aftershock . The amount of water fed in fluctuated between 2 and 20 cubic meters per hour in the following days.

On March 13th the mobile generators finally succeeded in establishing an emergency power supply. The gauges again provided information on the status of the reactor, but the cooling systems remained out of order.

Over the next few days and weeks, the defective water level gauges continued to show that half of the fuel elements (or their remains) were covered with water. Apparently it had been possible to stabilize the water level via the fire extinguishing pipe. Every now and then the water supply had to be interrupted again for a few hours because the area was evacuated due to critical situations at reactor block 3 , due to further earthquakes or to repair minor defects in the pumping system.

It was now largely agreed that a core meltdown was taking place in Unit 1; Government spokesman Yukio Edano also officially confirmed this. Based on the radiation readings in the reactor of Unit 1 on March 15 (see section Radiation in the reactors ), Tepco estimated that 70 percent of the fuel rods were already damaged. Six weeks later, this figure was then corrected down to 55 percent - still based on the measurements from March 15 - because it was initially miscalculated. Another two and a half weeks later it was assumed that 100 percent of the fuel rods were damaged.

The makeshift cooling did not succeed in stabilizing the reactor core. On the morning of March 16, large amounts of steam escaped from the reactor building, while the radiation on the premises (see graphic ) rose sharply. In the following days the activity in reactor 1 (see also section Radiation in the reactors ) increased again. The temperature at the pressure vessel temporarily reached a maximum of 383 ° C on March 22nd, above the maximum planned operating temperature of 300 ° C.

On March 20, Block 1 was reconnected to the external power supply via a new power distributor (the old one was under water in the basement of the turbine house), and the lighting in the control room was restored on March 24. The majority of the electrical systems remained without function.

Only on March 23, Tepco switched the water feed into the pressure vessel to a different access line ( feed water - instead of fire extinguishing / core spray line) and more powerful pumps, so that the amount of water could be increased from 50 to 170 cubic meters per day . This, too, was apparently not enough to get the reactor under control: the radiation readings from the pressure vessel rose again to a new high by April 1st. Salt deposits may have restricted the flow of cooling water.

On March 31, for the first time since the power failure, the cooling pool in Block 1 was also cooled: A truck- mounted concrete pump sprayed 90 tons of water on it. It is unclear how much of the water was in the pool, but later research has shown that the water level never fell into a critical range.

Another unstable reactor

- April 2011

In April, reactor 1 seemed to be the only one that remained unstable: the measuring devices showed a steady and uncontrolled increase in pressure in the pressure vessel throughout April (see graphic; it was only two months later that it was discovered that the pressure sensors were also defective and displayed too much) . The reactor core presumably continued to produce hydrogen. After consultation with the Ministry of Economic Affairs, Tepco filled the containment with nitrogen to prevent a possible oxyhydrogen explosion.

On April 8, the radiation sensor in the pressure vessel of block 1 showed an extreme increase; the following day he fell out . Two weeks later, the ratio of 131 I and 137 Cs concentrations in the seawater channel of the adjacent and structurally connected Block 2 rose sharply.

On April 21, the Kyodo News reported that, according to a Tepco official, reactor 1 could (again or still) be undergoing a meltdown.

The power plant operator was concerned that the situation could get out of control if the makeshift cooling were to be unplanned and wanted to increase the amount of water fed in in order to fill the safety and pressure vessels with the excess water and thereby cool the reactor more reliably. In addition, a new, more stable and closed cooling circuit should be installed.

- May 2011

In preparation for the planned work - Tepco published a roadmap for this - the air in the building was decontaminated with special air filter devices . The water level gauges for the pressure vessel were then recalibrated and it was found that the area of the reactor core in which the fuel elements had been located before the melt was not about half under water, but not at all. Apparently, both the pressure vessel and the containment vessel were damaged and significant amounts of cooling water leaked from the reactor. The planned new cooling measures became obsolete due to the leaky safety container. The basement of the reactor building, in which the condensation chamber is located, was half filled with an estimated 5,000 tons of radioactive waste water.

The meltdown report on April 21 was not confirmed. It was now assumed that the remains of the reactor core were partly in the pressure vessel and partly in the containment and were cooled there.

Protection of block 1

- from June 2011

The cooling of the cooling pool was switched from a concrete pump to a direct line at the end of May and to a closed circuit in August. From the end of June, recovered wastewater was used to cool the reactor, so that an indirect cooling circuit was created to replace the closed cooling system that was no longer feasible.

As a hedge against radioactive emissions and rainwater entering a protective cover was built around the reactor building, consisting of a steel frame, PVC -coated polyester fabric - Plan and an elaborate ventilation system (completed in October 2011). The roof of the envelope can be opened if necessary.

On August 19, 2011, the reactor temperature in Unit 1 fell below 100 ° C for the first time on all sensors.

High hydrogen concentrations of 61 to 63 percent were discovered in pipes on the reactor. Presumably they were leftovers from the initial phase of the accidents. The hydrogen was driven off by pumping in nitrogen.

New Tepco simulation calculations in November showed that the majority of the molten fuel in reactor 1 had left the pressure vessel and had accumulated on the bottom of the containment (No. 13 in the picture above ). The concrete floor could be eroded up to 65 centimeters deep. A concrete layer of at least 37 centimeters would remain between the fuel and the steel casing of the containment (No. 19). Underneath there is another layer of concrete several meters thick (No. 20). It is assumed that the cooling measures carried out stopped further corrosion of the concrete.

Reactor block 2

Power failure and cooling problems

Block 2 was also automatically shut down on March 11 at 2:46 p.m. (local time) and initially supplied with emergency power from its two diesel generators. In order to refill water that evaporates in the reactor, the workers in the control room switched on one of two steam-operated emergency cooling systems (the RCIC system, Reactor Core Isolation Cooling; for example: "Cooling the reactor in isolated operation").

At 3:37 p.m. and 3:41 p.m., the generators failed due to flooding, and so did the electrical cooling water pumps for the cooling pool and the reactor condensation chamber. Parts of the battery emergency power supply also failed due to tsunami damage.

At 16:36, Tepco reported to the supervisory authority that the water injection into the reactor - i.e. the emergency cooling - was no longer ensured. The steam-driven cooling system was independent of the generators, but because of the power failure, the RCIC status display and the measuring device for the cooling water level had failed. On March 12th they were put back into operation with a temporary power supply. The water level was a little lower, but stable. The pressures in the reactor were in the normal range. Nevertheless, several pressure relievers were attempted around noon, which were unsuccessful due to the lack of overpressure. Meanwhile, the roof of the neighboring reactor building 1 to the north exploded.

This was followed by changing messages on the Tepco website about the state of the cooling. At 8 p.m. it supposedly stopped working; on the morning of March 13th at 9 a.m. it was said that the RCIC system was in operation. The later published records of the employees are also contradictory. There were still problems with measuring the water level. To be on the safe side, Tepco prepared the feed of seawater.

At 11 a.m., the containment was again relieved of pressure. Between 2 p.m. and 5 p.m. the pressure in the containment dropped a little. Around 2 p.m., mobile power generators were also connected, so that, according to NISA, the continued operation of the emergency cooling system was ensured.

On March 14, at 11 a.m., the neighboring reactor building 3 to the south also exploded and damaged the equipment for pumping seawater into reactor 2. Immediately after the explosion, the blow out panel of reactor building 2 was opened to prevent hydrogen accumulation as in the Blocks 1 and 3 to prevent. Around this time, the cooling system actually failed in Block 2. The extraordinarily violent explosion in Block 3 may have caused further damage in Block 2. At 1:18 p.m. - the water level in the reactor pressure vessel had already fallen by about one meter, but was still above the fuel elements - Tepco reported the cooling failure to the supervisory authority. The second steam-powered emergency cooling system, which is normally activated in such cases, remained switched off.

The introduction of seawater was prepared again, but had to be interrupted from 3 p.m. to 4 p.m. due to an aftershock. The fire service pump was ready for use at around 4:30 p.m., but the pressure in the pressure vessel first had to be reduced. The workers brought car batteries from their vehicles to the control room and tried to use them to operate the pressure relief valves. However, they could not be opened because an airflow meter was accidentally switched off. Tepco tried unsuccessfully for several hours to let off steam from the pressure vessel in order to then vent the safety vessel as well.

The water level kept falling. Around 5 p.m. the fuel elements were partially exposed and from 6 p.m. completely. At this point the pressure relief valves finally opened. It took an hour to release the pressure enough. In the meantime, the fire pump, which was not constantly monitored due to the high level of radiation on the premises, ran out of fuel. Almost another hour passed before the water injection could begin - too late: the meltdown was already underway at this point. Despite further attempts to relieve pressure - the pneumatic venting valve kept closing on its own - the pressure in the containment rose sharply and reached around 750 kilopascals around midnight .

The water level measuring device indicated now and in the coming days and weeks that half of the fuel elements were covered with water. Only two months later - after calibrating the measuring device in block 1 - it became clear that the device in block 2 (and 3) could have displayed too much the whole time. Similar to March 12 in Block 1 , the containment seals presumably failed and hydrogen got into the reactor building.

Damage to the containment

According to reports published later by NISA and JAIF , around midnight (March 15), steam was released from the containment into the area. However, the sensor showed no pressure drop. It remained at 750 kPa until around 6:10 am a loud bang could be heard from the direction of the condensation chamber under the reactor (" an abnormal noise began emanating from the nearby Pressure Suppression Chamber " according to Tepco). The NISA spoke of an "explosion sound" and a hydrogen explosion in the space below the reactor in which the condensation chamber is located; later also of a “big, impulsive sound” and a “ big impact sound”. The pressure in the chamber suddenly dropped; apparently it was damaged. Damage was also found in the roof area of the reactor building and in the adjacent waste processing building. Tepco has so far denied that an explosion took place and suspects that it was confused with the approximately simultaneous explosion in Block 4 (as of November 2011).

The radiation exposure on the site rose sharply, which may also be related to the explosion in Block 4. Dose rates of up to 12 millisieverts per hour (mSv / h) were temporarily measured at the site boundary. At the reactor building 4 the measured values were 100 mSv / h and at the neighboring block 3 they were 400 mSv / h. Because of the radiation risks, Tepco reduced the number of employees on the site from around 800 to 50.

At 10:30 am, Minister of Economics Banri Kaieda Tepco instructed to immediately inject water into the pressure vessel of reactor 2 and to release the pressure from the containment. After the containment 2 vented by itself in the meantime and the water had been fed in for 14 hours, this instruction came too late.

In the evening, the overpressure in the pressure vessel fell to zero, which indicates greater damage.

Satellite photos from March 16 show steam escaping from the exhaust flap on the east side of the reactor building. This could also be observed in the following days.

Based on the radiation readings in the containment, Tepco estimated that one third of the fuel rods from Unit 2 were damaged. That estimate later turned out to be way too low.

By March 17, the damage to the condensation chamber also spread; the overpressure in the chamber also fell to zero.

Three weeks later, information from the US Atomic Energy Agency emerged that pieces of the molten core of Reactor 2 had flowed out of the pressure vessel and had accumulated in the bottom of the containment. Radiation data from the condensation chambers in units 1 to 3 (in the lower area of the containment) confirmed this: the measured value for unit 2 was extremely high at 121 sieverts per hour.

Power connection and cooling measures

In the meantime, a new high-voltage line was in the works, which was to be connected to Block 2 first. It was hoped that the regular cooling systems could be put back into operation.

Meanwhile, on March 19, seawater began to be fed into the cooling pool. In contrast to Unit 1, the decay basin also had to be continuously cooled in Unit 2 because it contained twice as many and “fresher” fuel elements. At intervals of several days, the basin was refilled with cold water via an existing pipe. It was thus possible to stabilize the water temperature at around 50 ° C. The water level never fell into a critical range.

Also on March 19, the new power line was connected to a makeshift transformer in Block 2, and the next day to a temporary, new power distributor. From March 26th there was again a real lighting in the control center. A photo released on the same day shows three men in protective suits looking at individual instruments - in a room full of dead screens and warning lights. The power supply was restored, but as in Block 1, most of the systems remained inoperative.

From March 26, freshwater was injected into reactor 2 instead of seawater. In the basement of the turbine building of Block 2, Tepco measured a very high radiation of more than 1000 mSv / h on the surface of water that had collected there (1000 mSv / h was the upper limit of the existing measuring devices). The following day, similar radiation values were also discovered in the water in an attached maintenance tunnel. As a result, the Japanese government announced on March 28 that it was assuming a temporary partial core meltdown in reactor 2.

On March 29, the cooling of the cooling basin was switched from sea to fresh water.

Sewage discharge into the sea

- April 2011

Since March 21st, strongly increased iodine and cesium concentrations in the seawater at the power plant were measured and the cause was sought.

On April 2, Tepco discovered a 20 centimeter long crack in a concrete cable duct near the water inlet of Block 2, from which highly radioactively contaminated water flowed into the Pacific. An attempt to close the leak with concrete failed, as did the introduction of a mixture of superabsorbent , sawdust and shredded newspaper into connecting pipes to the turbine building. On April 6, Tepco was able to close the leak with a water-glass- based sealant .

According to NISA, most of the contaminated water had been released in the two days after the condensation chamber was damaged on March 15, but smaller amounts of water continued to flow out of the reactor, from where it entered the sea through various channels and shafts ( see grafic). Only later did it become clear that the pressure vessel was possibly also damaged and that large amounts of wastewater were continuously leaking from there.

On April 9, Tepco began building a steel wall and building a silt fence in front of the water inlet of Unit 2 to protect the sea from further contamination.

A week later, the first measured values for the water in the cooling pool were available. They showed a high level of radioactive contamination (see table of measured water values in the cooling basin ), which was most likely caused by emissions from the reactor.

Extremely highly contaminated water had also collected in the basement of the turbine building of Unit 2, a total of 25,000 cubic meters. Tepco began to pump 10 cubic meters per hour into the waste storage facility, while the ongoing cooling measures of the reactor and the cooling basin were constantly generating new wastewater. The water level in the turbine building remained almost unchanged. The further leakage of the extremely contaminated water from Unit 2 into the sea could, however, be largely stopped by the sealing and containment measures .

- May 2011

After the radiation in the condensation chamber below the reactor had decreased by the beginning of May, it temporarily increased fourfold from May 3rd . The molten core was still moving.

Protection from block 2

Further work in the reactor building was hardly possible due to excessive radiation exposure, and a humidity of almost 100 percent prevented the use of decontamination devices. The cooling pool was therefore given a new, closed cooling circuit that lowered the water temperature from 70 to 40 ° C and helped to reduce the humidity. The building was then ventilated and the air further decontaminated. Measuring devices on the reactor were calibrated . An investigation revealed that the highly radioactive wastewater was six meters high in the basement.

- from June 2011

At the end of June, the introduction of nitrogen into the containment began in Block 2 in order to prevent possible oxyhydrogen explosions.

In order to improve the reactor cooling, the cooling water was also introduced via the core spray system from mid-September . The water is sprayed from above into the pressure vessel and over the reactor core instead of pumping it in from the side, as is the case with all other cooling systems.

In early November, cesium was filtered in the cooling pool in order to reduce the extremely high level of water contamination.

On March 27, 2012, endoscopic examinations of the containment revealed that the water level was only 60 cm instead of the expected three meters due to leaks. However, the water temperature is 48.5–50 ° C. The radiation in the partially destroyed containment is between 30 and 73 Sv per hour.

In February 2017, a camera could be brought directly under the pressure vessel for the first time. Here it was confirmed that the reactor has melted completely and may have eaten its way through the containment. In addition, extreme radiation doses of 530 Sv / h were measured.

Reactor block 3

At the time of the accident, in contrast to Units 1 and 2, reactor block 3 was also equipped with 32 mixed oxide fuel elements (out of a total of 548 fuel elements), which contain a mixture of uranium dioxide and plutonium dioxide . Plutonium is poisonous and, due to its radiation effect, is highly carcinogenic even in small quantities. There were only conventional uranium fuel elements in the spent fuel.

Power and cooling failure in block 3

Block 3 was also shut down quickly on March 11 at 14:46 due to the earthquake, and the RCIC emergency cooling system (Reactor Core Isolation Cooling System) took over the water injection into the reactor as scheduled. After the arrival of the tsunami, the two emergency generators and the electric cooling water pumps for the cooling pool and the reactor condensation chamber failed at 15:38 and 15:39. The steam-powered RCIC system continued to run independently of this, in contrast to Block 2, however, only at half power. The backup batteries remained intact.

Around midnight the emergency cooling no longer worked properly; the water level fell below the intended range. On March 12th around 11:30 am the RCIC system failed, and an hour later the HPCI system ( High Pressure Coolant Injection ) switched on automatically . This is a much more powerful, steam-powered emergency cooling system that is used when the RCIC system is insufficient or fails. There was a sharp drop in pressure in the pressure vessel, which indicated earthquake damage to the HPCI pipes.

The supervisory authority (NISA) announced at a press conference around 6 p.m. that the water level in the reactor had fallen and that something urgently needed to be done about it. Around 9 p.m., preparations began to let off steam from the containment. (Initial NISA reports erroneously stated that the pressure was relieved at 8:41 p.m.)

On March 13 at 2:44 a.m., the HPCI emergency cooling failed because the batteries were exhausted or the reactor pressure was too low. Tepco tried unsuccessfully to get the RCIC system back into operation. At 5:10 a.m., the complete failure of the cooling was reported to the supervisory authority. At this point the pressure in both containers had risen sharply again. An attempt to inject water with the stationary diesel fire extinguishing pump of the reactor therefore failed.

After all the car batteries available in the power plant had already been used to rescue units 1 and 2, Tepco took batteries from vehicles at the government operations center and operated the safety valves on the pressure vessel of reactor 3 from the control center. The safety container valves - similar to block 1 - opened manually. Around 8:50 a.m., the pressure in the pressure vessel fell from approximately 7350 to 500 kilopascals (kPa), while in the containment it rose from 470 to 640 kPa and then fell again.

The hourly updated Tepco webcam showed steam escaping from the chimney of block 3/4 at 10:00.

Makeshift cooling of the reactor

At 9:08 a.m., makeshift cooling also began for reactor 3 by injecting water through the fire extinguishing pipe. The fire engine normally stationed at Block 5/6 was used for this. First, fresh water was fed in from the cistern of the fire extinguishing system and then switched to sea water mixed with boric acid. The measuring devices nevertheless indicated that the water level was still falling. NISA suspected that the measurement display was incorrect, as other readings indicated a functioning water supply, while government spokesman Edano mentioned technical problems with pumping in. The 3.70 meter long fuel rods were now probably dry for a good 3 meters and were very hot. Edano announced that a core meltdown in Block 3 is expected and that a hydrogen explosion is also possible here. Later research confirmed that a core meltdown began around this time.

After the pneumatic pressure relief valve closed by itself, it was opened again manually with a compressor around noon. At 1 p.m. and 2 p.m. the webcam showed steam escaping from the pressure relief chimney of block 3/4. This venting operation was repeated several times later.

On the night of March 14th, the water injection into the reactor had to be interrupted due to a lack of seawater in the sump. According to NISA, the interruption took place between 1:10 and 3:20 a.m. However, the water level displayed for the pressure vessel only began to drop shortly after 3 a.m., while the pressure in the pressure and safety vessel rose at the same time. The fuel assemblies were probably three meters long again at around 6 a.m., so that the meltdown could proceed.

At 5:20 am, according to later NISA reports, steam was released again; Radiation readings from the site tend to indicate venting between 2 and 5 a.m. However, the pressure in the containment increased steadily and reached around 500 kilopascals (kPa) around 7 a.m. From this point on, a rising water level in the pressure vessel was displayed again. The water level indicator then stabilized to such an extent that the fuel elements were probably 40 percent covered. The pressure remained at about 500 kPa for the next few hours.

Armed Forces tank trucks delivered 35 tons of fresh water that morning and began pouring it into the water sump for reactor cooling.

explosion

At 11:01 a.m., a violent explosion occurred in the reactor building. Video recordings show a ball of fire in the upper area and a dark mushroom of smoke rising quickly and vertically upwards. According to Tepco, seven people were injured in the explosion. The Daily Telegraph reported that six Japanese Central Nuclear Biological Chemical Weapon Defense Unit employees were killed , but the report remained unconfirmed, even after the debris was later cleared.

In contrast to Block 1, the explosion not only destroyed the roof area, but also parts of the floor below. Radioactive debris was hurled onto the site at distances of up to one and a half kilometers. Hot spots with local dose rates of up to 1000 millisieverts per hour arose around block 3 . In the neighboring block 2, the cooling system or its power supply was presumably damaged , which led to a core meltdown there with far-reaching consequences, including contamination of the sea. There was an oil fire in Unit 3, which caused further serious damage to the reactor building.

The American nuclear engineer Arnold Gundersen pointed out the much greater force and the stronger vertical direction of the Block 3 explosion compared to the hydrogen explosion in Block 1. Gundersen suspected that the explosion in Unit 3 was based on a criticality incident, i.e. a nuclear explosion in the decay basin, which was triggered by a smaller hydrogen explosion in the reactor building.

The makeshift cooling of reactor 3 had to be interrupted until the evening because the explosion had damaged the fire fighting equipment. The water pit with the freshly delivered fresh water was also unusable due to debris that had fallen in.

On March 15 at 10:22 a.m., radiation of 400 millisieverts per hour (mSv / h) was measured at Block 3. Based on radiation readings in the reactor, Tepco estimated that the fuel rods in reactor 3 were damaged by a quarter. That number was later revised up to 30 percent.

Large amounts of steam have been observed rising from the building since the morning of March 16 and on the days that followed. A local dose rate of 400 mSv / h was still measured at reactor block 3. After 10 a.m., the radiation value at the boundary of the site rose to up to 10 mSv / h (at the same time, large amounts of steam also escaped from Block 1). It was feared that the containment would be damaged and the joint control center of Blocks 3 and 4 was cleared between 10:45 and 11:30. The water injection into the pressure vessel was interrupted for this time.

Further manual depressurization took place from March 15 to March 20.

Makeshift cooling of the cooling pool

In addition to the reactor core, the fuel elements also had to be cooled in the cooling pool in the upper area of the reactor building. There was a risk that the explosion had caused leaks and that the fuel assemblies overheated and caught fire due to a lack of cooling water. The existing pumps could not be used, however, due to a lack of power supply or due to explosion damage. Instead, they resorted to seemingly desperate means: Chinook helicopters of the armed forces were supposed to throw water from the air. The first attempt on the evening of March 16, however, was canceled due to the high risk of radiation for the pilots.

The next morning they made a second attempt. This time, the helicopters were shielded from below with lead plates and dropped four water charges of 7.5 tons each from extinguishing water tanks onto the reactor building as they flew past. Video recordings show that the drop was not very accurate and that a large part of the water fell next to the reactor block or was already evaporating in the air. Instead of the planned dropping of several dozen water charges, the attempt was canceled.

The New York Times was of the opinion that the helicopter drops were primarily a demonstration of the ability to act for the Japanese people and the United States. Prime Minister Naoto Kan then phoned US President Barack Obama personally and told him about the alleged success of the campaign.

After the failure from the air, the next attempt was made from the ground: A water cannon from the riot police and five special fire engines from the Japanese armed forces sprayed a total of around 30 tons of water on or into the reactor building. Tepco rated the attempt as a success: Steam had risen, so you hit the cooling pool. Therefore, the cooling with fire trucks of the armed forces continued in the following days.

From March 20, fourteen fire engines from the Hyper Rescue Unit of the Tokyo Fire Department also took part in the operation. The amount of water sprayed increased to several hundred tons a day in the following days.

Hazardous situations and cooling measures

On March 20, the pressure in reactor 3 rose again. Temporarily, almost 500 kilopascals were reached in the containment - allegedly so “little” that it was not necessary to let off contaminated steam again. In later reports, however, the (last) opening of the pneumatic pressure relief valve is mentioned at around 11:25 a.m.