New York City Subway

The MTA New York City Subway , also called New York Subway or simply Subway or German “New Yorker U-Bahn” , is the subway network of New York City . It was opened on October 27, 1904, making it one of the oldest in the world. With 25 lines, 472 stations, 380 kilometers of track with over 1355 kilometers of track and over 4.9 million passengers per day, it is one of the longest and most complex networks in the world. In the ranking, it takes fourth place after the Beijing subway , Shanghai metro and London Underground .

The largest part of today's route network was built after the turn of the century until around 1940 by three competing companies: the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT), the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) and its successor, the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) and the city of New York itself under the name Independent City Owned Rapid Transit Railroad ( Independent or IND for short ).

The operator has been the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) since 1953 . It has been a subsidiary of the state transport company Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) since 1968 and is better known to the public under its marketing name MTA New York City Transit or simply "TA".

Key data

The New York subway network is basically a multiple axis network. Almost all branches of the route flow into one of the eight main routes in Manhattan , six of which run more or less parallel from north to south and two in west-east direction. The ninth main line is the IND Crosstown Line , which runs from Brooklyn bypassing Manhattan to Long Island City in Queens .

In addition to the island of Manhattan, the districts of Brooklyn and Bronx in particular are almost completely developed; In addition to a few connecting routes to Brooklyn and John F. Kennedy Airport, Queens has essentially three routes, two of which form the main traffic axes. Contrary to earlier plans, the fifth district of Staten Island is not connected, but the MTA operates a railway line there with modified subway cars. The once planned route to Fort Lee (New Jersey) over the George Washington Bridge was never realized.

The branches in turn cross each other several times, primarily in the southern part of Manhattan, in downtown Brooklyn and in the area of Long Island City. This seemingly disordered routing turns out to be a very simple structure, provided that the rail lines of the then competing companies IRT, BMT and Independent are each considered separately.

Of the 370.1 kilometers of route network with a total of 1,055 kilometers of track, 220.5 km run in tunnels, 112.6 km elevated and a further 37 km at ground level, in a cut or on a railway embankment . There are 71 route kilometers with three and another 140 with four operating tracks. Some short sections have six tracks or just one. Including depots and sidings, there are a total of 1355 kilometers of track. The track width is 1435 mm ( standard gauge ). However, there are two different clearance profiles on the New York City Subway , which is expressed in different vehicle widths.

Of the 468 stations served, 277 are in the tunnel, 153 elevated, 29 on a railway embankment and nine in the cut. The relatively highest station is Smith / 9 Streets on the IND Culver Line in Brooklyn; it is located on a bridge over the Gowanus Canal and is 26.8 meters above street level. At 54.9 meters below street level, 191st Street in Manhattan is the lowest station on the IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line .

In 2006 the subway had almost 1.5 billion passengers, more than 4.9 million on an average working day. According to its own statements, this makes it the third most popular underground train in the world. The total of 6,221 underground cars covered 570 million commercial vehicle kilometers. Energy consumption in 1995 was 2397 kJ / passenger kilometer. With over 27,000 employees, the subway is the MTA's largest business and also a major employer in New York.

The second New York subway is the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH), which crosses the Hudson River from Manhattan in two tunnels and leads to Jersey City , Hoboken , Harrison and Newark in the bordering state of New Jersey . It does not belong to the MTA New York City Subway, but is operated by the state port company Port Authority of New York and New Jersey . There are transfer options, but neither rail connections nor a real tariff community (only certain MTA ticket types are accepted); However, the profile and parts of the technical equipment are similar.

history

The history of the New York City Subway begins well before the official opening of the first subway route on October 27, 1904. The first plans for the operation of a subway between New York City Hall and the Grand Central Depot were made as early as 1872. In that year, Cornelius Vanderbilt founded the New York Rapid Transit Company , had surveys carried out and a cost estimate for such a railway line drawn up. After the latter showed that the route would not be profitable, Vanderbilt discontinued the project. Even before the subway was built, there were a number of elevated railways and other predecessor systems from various companies, some of which are still in operation today. The actual expansion of the route network took place at the beginning of the 20th century in several stages, with the double contracts and the Independent being mentioned above all. The next milestone was the unification of the underground network in 1940. In the following years the network expansion was limited to connecting tunnels and modernization measures. In the 1960s, a 20-year decline set in, the processing of which lasted until the turn of the millennium.

“Schnellbahnen” in the 19th century

New York faced numerous problems in the second half of the 19th century. The city at the mouth of the Hudson River in the Atlantic had become an important trading center since the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 and attracted immigrants from all countries, so that the population in today's urban area rose from 80,000 to over three million in that century. The problem was not only the traffic itself, but also the strong concentration of the population in the southern part of Manhattan. For the very few inhabitants of the northern part of the island, the way to work was unreasonably long.

Against this background, the mid-19th century discussions in New York began about rail network (rapid transit system) to build. Despite the obvious necessity, such projects met with rejection in those years.

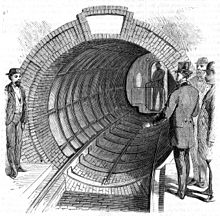

In February 1870, Alfred Ely Beach installed a 312-foot (95-meter) long stretch of subway under Broadway that functioned like a pneumatic tube , the Beach Pneumatic Transit, almost unnoticed by the public . A single pressure-tight carriage was pushed back and forth between two stations in a tube using compressed air. However, this in and of itself comfortable principle of locomotion proved to be impractical and technically too complex, so that Beach abandoned the facility in 1873. The tunnel was eventually destroyed when the BMT Broadway Line was built in 1912.

As early as 1868, Charles Thompson Harvey opened the first short section of the West Side and Yonkers Patented Railway , an elevated cableway , on Greenwich Street at today's Ground Zero . A year later the route led to 30th Street. But the traffic performance of the single-track route was too low to be able to work profitably, so that the stock market crash in September 1869 put an end to the company.

At that time it had also become clear that the construction of a subway would only be possible with subsidies from the state due to the high costs . Because political conflicts and legal framework conditions continued to delay the start of construction, only elevated railways were initially built in Manhattan on a private initiative . From 1872 they led from the South Ferry pier on the southern tip of the island along Second, Third, Sixth and Ninth Avenues to the north and finally reached the Bronx around 1880 . The elevated railways were initially operated with steam locomotives , but between 1900 and 1903 they were electrified with power supply via conductor rails . The bottom section of Ninth Avenue was Harvey's former cable car.

The Interborough and the first underground

However, the elevated railways were unable to solve the New York traffic problem due to a lack of sufficient traffic, especially since the population continued to grow rapidly. But the political prerequisites were still missing. Among other things, the debt was not allowed to exceed $ 50 million. In order to cover the construction costs, a financing model was designed according to which a subway would belong to the city, but a private company should take over the construction and operation. In the tender for contract No. 1 (Contract No. 1) in 1899, John B. McDonald and his financier August Belmont junior were awarded the contract for 35 million US dollars. The groundbreaking ceremony finally took place on March 26, 1900.

The route ran from City Hall Station at City Hall, initially under Lafayette Street and Park Avenue, to the north. At Grand Central Station , it turned left onto 42nd Street and then led to what is now Times Square . From there it went under Broadway to 242nd Street in the Bronx, today's terminus of the IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line . A branch line ran from 96th Street station under Central Park to Harlem , and from there further under the Harlem River along Westchester Avenue and Sutpin Boulevard to Bronx Park on 180th Street . This corresponds to today's IRT Lenox Avenue Line and the southern part of the IRT White Plains Road Line .

The depot was reached via a short branch route from 135th Street . The route ran completely in the tunnel in the lower and middle part of Manhattan, the northern sections from Dyckman Street and Jackson Avenue as well as the 125th Street station on the West Side and the depot were above ground . After the electrical operation had already proven itself on the elevated railways, the decision was made to use this technology for the underground from the very beginning. The first section between City Hall and 145th Street was opened to traffic on October 27, 1904. This date is considered the official opening of the New York subway.

1902 McDonald was awarded contract no. 2 (Contract No. 2) , of the continued construction of the stretch of its southern end under the East River through to the station Atlantic Avenue to the Long Iceland Railroad envisaged in Brooklyn. This section was opened in stages from 1905 to May 1, 1908.

The operating company Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT), founded by Belmont in 1902, was responsible for the operation . In order to increase the profitability of the new subway, the operation of the four Manhattan elevated railways was taken over as early as 1903 and the subway was built according to their specifications . In this way, joint operation should at least be possible in the outskirts. In addition, it created a monopoly-like position in the local traffic of Manhattan and the Bronx. Belmont was determined not to give this up again. Possible competitors were therefore simply bought up. This practice was viewed with suspicion by politicians. As a result, the Elsberg Act was created in 1906 , a law that dramatically worsened the conditions for private operating companies.

Brooklyn and the BRT

Brooklyn , which was still independent until 1898, developed similarly to New York in the second half of the 19th century. The population and traffic problems grew, and in 1885 the first elevated railway between the ferry terminal at Fulton Ferry and Alabama Avenue began operating. By 1893, more routes were added via Myrtle Avenue, Broadway, Fulton Street and Fifth Avenue. The steam locomotives and cars used were similar to those from New York.

In addition, there were a number of steam-powered excursion trams that led to the summer resort of Coney Island on the Atlantic coast since the 1860s and 1870s . The routes began on what was then the southern outskirts of the city, which was roughly at the level of Prospect Park , and ran at ground level along the streets to the beach. A similar railway line connected East New York with Canarsie Pier on Jamaica Bay since 1865 .

The tracks over the Brooklyn Bridge , which had been installed since it opened in 1883, were initially only used with a cable car because there were fears that the heavy weight of a steam locomotive could cause the bridge to collapse. It was only electrification in 1896 that allowed through traffic from the Brooklyn outskirts to the Park Row terminus in Manhattan.

In 1896, Timothy S. Williams founded the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Corporation (BRT) as a railroad holding company . Under his leadership, this company bought all trams and almost all rail lines in Brooklyn within four years , electrified them and streamlined their organization. In addition, ramps, rail connections and connecting lines were built so that continuous journeys from Coney Island or Jamaica to Manhattan were soon possible.

Inspired by the success of the Brooklyn Bridge, BRT planned to have their trains cross the East River on the Williamsburg Bridge and the Manhattan Bridge as well. There the three ends should be connected with an elevated track to save the headache. However, the construction work was delayed because the city administration on the Manhattan side only wanted to approve a subway and the geological conditions caused difficulties. However, the company was already taken into account when building the two new bridges.

The Triborough Plan

After the statutory debt ceiling for the now unified city of New York was raised, further plans for the construction of the subway matured by 1908. The close traffic relations across the East River should be dealt with much more closely. The discussed tri borough plan ("three-district plan") essentially contained three new routes. For aesthetic reasons, subways were planned.

- From the southern tip of Manhattan via Broadway and Lexington Avenue to Pelham and Woodlawn in the Bronx

- The loop between the three bridges planned and partly started by the BRT, the later BMT Nassau Street Line

- A subway under Fourth Avenue Brooklyn, which runs from the banks of the Hudson River over the Manhattan Bridge to Bay Ridge and Coney Island. This corresponded to today's BMT Fourth Avenue Line and the BMT Sea Beach Line .

An essential feature of those plans was that they no longer used the narrow clearance profile of the elevated railways, but rather the wider normal railroad profile. This should encourage operators of suburban railways to let their trains go into the tunnel to Manhattan . However, the technical equipment had to be based on the previous routes in order to continue to operate old vehicles.

When tendering these routes there were initially no bidders beyond the Nassau Street Line because of the Elsberg Act . Only after its abolition in 1909 could at least the construction of the Fourth Avenue Line be successfully awarded. This time, however, the BRT from Brooklyn was awarded the contract; After a good five years of construction, the line was opened on June 19, 1915. The first wide-profile section had already gone into operation on September 16, 1908 with the Essex Street station on Williamsburg Bridge; but still only the narrower elevated carriages went there.

Until the Fourth Avenue Line was completed, only the tram ran on the tracks of the Manhattan Bridge. The route was named after their tariff of three cents "Manhattan Bridge Three Cent Line".

Extensions in the course of the double contracts of 1913

When the city of New York was allowed to increase the debt for structural investments beyond the previous level through changes in the law, new opportunities for network expansion opened up. The city had learned lessons from the Triborough plan and this time wanted to offer the operating companies attractive conditions. Finally, they agreed on mixed financing, in which the city should raise a good half, the IRT and BRT each about a quarter of the total of 352 million US dollars of construction costs through loans. Construction and operation should again be in private hands and the city, in addition to a profit sharing, should have the right to buy back the routes, the so-called recapturing . Furthermore, the fare was fixed at five cents.

So in 1913 the so-called dual contracts were signed, which meant the largest expansion of the New York subway to date. Including the Fourth Avenue Line, the route network should grow by 519.2 to 995.5 kilometers of track within four years. The result of this construction project, taking into account the lines already built in New York, is referred to as the “ dual system ”.

Under Contract No. 3, the IRT expanded its existing network, particularly in Manhattan and the Bronx . She was awarded the contract for the following routes:

- The previous route network from the first two contracts was to be expanded to include today's IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line between Times Square and South Ferry and the IRT Lexington Avenue Line north of 42nd Street. Together with the 42nd Street Shuttle, these two north-south routes have since formed the so-called "H-System" . The name comes from its route on the map, which to a large H recalls.

- The IRT Jerome Avenue Line and the IRT Pelham Line were created as the northern feeder to the IRT Lexington Avenue Line.

- The IRT White Plains Road Line was extended to Wakefield – 241st Street .

- In Brooklyn, the IRT Eastern Parkway Line reached its current terminus at New Lots Avenue ; there was also a branch line, the IRT Nostrand Avenue Line. In addition, a new tunnel under the East River connected the IRT West Side Line with Brooklyn.

- With today's BMT Astoria Line [sic] and the IRT Flushing Line, Long Island City in Queens also received a subway connection. These two routes were operated jointly.

Contract No. 4 went to the BRT . Here the focus was in Brooklyn .

- From the Triborough plan, the Fourth Avenue Line and the Nassau Street Line, including another tunnel under the East River, were incorporated into Contract No. 4. The originally planned ramp up to the Brooklyn Bridge was omitted.

- The excursion trams to Coney Island were expanded to three and four tracks and brought up to subway standards. The current BMT Brighton Line, BMT Sea Beach Line, BMT Culver Line, BMT West End Line and BMT Franklin Avenue Line were created. The tracks were either relocated from the road to a railway embankment or in a cut or elevated like an elevated railway. DeKalb Avenue in the Brooklyn Heights district served as a route node .

- The previous suburban railways to Canarsie and Jamaica over the Williamsburg Bridge and part of the Myrtle Avenue Line were also integrated into the subway. In addition, the construction of a subway from 14th Street Manhattans to East New York was planned.

- Contract No. 4 also contained a four-track line under Broadway in Manhattan, today's BMT Broadway Line. This brought the Brooklyners into direct competition with the IRT.

All new routes were built with wide profiles. Most of the old elevated railways also received a third track. Furthermore, both contracts provided for the expansion of some existing routes to this underground standard so that they could leave the tunnel on the edge of the city center and continue on the previous routes. The only exception was the so-called Steinway Tunnel , which led from 42nd Street under the East River to Long Island City. It was built as a tram tunnel in 1907 and still had the narrower profile.

The underground operation initially seemed to be a permanently lucrative business for the private operators. But the First World War and inflation suddenly created enormous difficulties. Construction was delayed by shortages of materials and labor, and spending rose nearly 200 percent from 1915 to 1925. On the other hand, however, fare increases were contractually excluded; a problem that could not be solved either judicially or politically. Under the new mayor John Francis Hylan (1917–1925), the city categorically rejected tariff increases.

The urban "Independent"

Hylan was an advocate of publicly operating the underground and wanted to achieve that goal with all his might. In order not to have to spend an unnecessarily large amount of money on recapturing , he tried to force the two operators out of business. He refused building permits and did not release some of the funds agreed in the double contracts, so that some important construction work dragged on longer than planned. This resulted in losses for the operating companies, which in 1918 even led to the bankruptcy of BRT. Hylan, in turn, reinterpreted this in public as mismanagement. He also polemicized against strikes and industrial accidents , such as the Malbone Street railway accident of 1918.

Despite all efforts, Hylan did not manage to persuade the IRT and the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT), which emerged from the BRT, to give up. So he drafted plans for a third subway network, which, in contrast to the existing routes, should be built and operated by the city itself. However, this ran counter to the plans of the state government , which did not want to tolerate any further fragmentation of the New York subway, but sought its unification.

On the other hand, the city of New York had now grown to over five and a half million inhabitants, and new subways seemed urgently needed. The dual system could no longer keep pace with the ever increasing number of passengers. In view of these pressing problems, a compromise solution was finally found that allowed Hylan's plans as well as the interests of the private operating companies to protect. The long-term goal, however, remained the unification and consolidation of the existing subways under the roof of the city.

The 600 million US dollar plans for that urban subway were unveiled in August 1922. It was supposed to be “independent”, ie “independent” of the interests of the private operators, and was thus given the name Independent City Owned Rapid Transit Railroad . The groundbreaking ceremony took place on March 14, 1925. Although Hylan was voted out of office that same year, the project could not be stopped because most of the construction work had already been awarded. This was particularly true of some sections of the route that just couldn't be integrated into the existing system. The first section of the Independent began operating on September 10, 1932 under the direction of the New York City Board of Transportation .

The route network consisted of two trunk routes in a north-south direction under the Eighth and the Sixth Avenue of Manhattan, which were to cross three times. In the north, connecting routes led to the northern tip of Manhattan, to the Bronx and under Queens Boulevard to Jamaica. In Brooklyn, head south to the base of the BMT Culver Line and east just under the BMT Fulton Street Line to East New York. The Crosstown Line was supposed to connect Brooklyn directly to Queens. By 1940 most of this project had been implemented.

The Independent had some special features that were considered a technical masterpiece at the time. The routes were consistently wide, free of intersections and almost entirely ran in the tunnel. Most of the tracks were laid on a firm track . All operating facilities were generously dimensioned; about half of the lines were laid out with four tracks. This led to a transport performance that, with over 90,000 passengers per hour and track, was around a third above the values previously achieved. The technical equipment was completely taken over by the BMT in order to prepare the Independent from the outset for a merger of these two networks.

Three years before the opening of the independent routes, plans for a second expansion stage, the Second Independent System , the "second independent network", were revealed. The Independent's route network was to be expanded primarily towards Queens. But the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent global economic crisis put an end to these ambitious plans for the time being, apart from a few preliminary construction work.

- Independent Subway

Association 1940

In view of this dramatic economic development, the problem with the unification of the New York subway became more pressing. The city struggled with the Independent's heavy debt and deficit. The private operating companies suffered from rising costs on the one hand and the fixing of the standard fare at five cents on the other, which made their financial situation increasingly precarious. The income could no longer cover the operating costs on many routes.

After several years of political controversy, the state government finally lifted the debt ceiling for New York City in 1938, so that the city could finally buy the IRT for 151 million and the BMT for 175 million US dollars. The IRT Division and the BMT Division emerged from the two networks, and the IND Division of the New York City Board of Transportation emerged from the Independent by analogy . The takeover took place at BMT on June 1 and at IRT on June 12, 1940.

After the takeover, some of the deficit elevated railway lines were shut down immediately, some after a few years. The IRT hit the Ninth Avenue Line and the Second Avenue Line as well as the Queensboro Bridge after the Sixth Avenue Line had already been bought back and demolished during the construction of the Independent main line. In Brooklyn, traffic ended on the Fulton Street Line, Third Avenue Line, Fifth Avenue Line, and Brooklyn Bridge. Otherwise nothing changed operationally at first; all three subnets continued to exist side by side.

The New York City Transit Authority

The city of New York now hoped to use the profits from the remaining, formerly privately operated routes to support the expensive and highly deficient Independent and at the same time be able to repay its debts without having to increase the standard fare of five cents. But the renewed inflation caused by the Second World War finally forced an increase to ten cents in 1947 and six years later to 15 cents.

Because in the first few years after the unification the consolidation dragged on rather slowly, apart from a few improvements in the operational process, the question of organization soon arose. The outsourcing of business operations based on the model of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey was favored . On June 15, 1953, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) was finally founded with the aim of ensuring cost-covering and efficient operation of the subways.

The second and much more difficult task soon turned out to be the need to raise funds for investments from the public sector, because the rolling stock and infrastructure of the once private routes were now getting on in years and, above all in the IRT division, needed extensive renovation. The oldest wagons there came from the time the subway opened in 1904, and the oldest BMT subway cars were almost 40 years old in 1953.

Between 1954 and 1962, therefore, over 2500 new cars were purchased for the IRT Division , which made up almost the entire fleet. At the same time, the stations on the first line from 1904 were given longer platforms to accommodate ten-car trains. At some stations, the movable platform edges ( gap fillers ) also had to be adapted to the changed door arrangement. The BMT technology was also introduced in the signaling system and train protection during this period .

The tight financial framework still left scope for the extension of the subway to the Rockaway Peninsula . The city bought Long Island Rail Road's Rockaway Line for $ 8.5 million and converted it to subway standards for another $ 47.5 million. In a similar way, today's IRT Dyre Avenue Line was added from the bankruptcy estate of the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway in 1941 .

In addition, some important connecting tunnels between BMT and IND lines were built during this time. The Culver Ramp between Church Avenue and Ditmas Avenue stations in Brooklyn opened in 1954, a year later the BMT 60th Street Tunnel Connection connected the BMT Broadway Line to the Independent's Queens Plaza station , and on December 26, 1967, it became the IND Chrystie Street Connection opens. This connecting tunnel, by far the most important, enables BMT trains coming from the Manhattan Bridge and the Williamsburg Bridge to enter the main routes of the Independent in Manhattan. At this time went IND and BMT Division officially in the Division B , and the IRT Division was henceforth according to Division A . Together with some pedestrian tunnels for changing between nearby stations of different divisions, the unification of the New York subway was also architecturally completed.

For the first time on January 4, 1962, the company used a driverless subway train on a route. The Times Square-Grand Central Shuttle automatic train ran daily until April 21, 1964 when, following a fire, a decision was made to replace the destroyed vehicles with conventionally operated subway trains.

MTA, program of action and decline

On March 1, 1968, NYCTA came under the umbrella of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) together with other public transport organizations in the New York area .

In the same year, the MTA presented a 2.9 billion US dollar “Program for Action” , which envisaged a massive expansion of the existing subway network in two phases. The federal government provided the funds under the Urban Mass Transit Act . In addition to a few new connecting lines in Queens and southeast Brooklyn, the Second Avenue Line was to be created as a further trunk line under Manhattan's Second Avenue and another tunnel would run under the East River at 63rd Street. The plans were similar to the previously failed Second Independent System from 1929. Construction for phase one began in 1972 on the East River, on Second Avenue and on what is now the Archer Avenue Line in Jamaica, Queens. Everything should be finished by around 1988.

At the same time, a number of lines were closed that were either unprofitable or were to be replaced by those new lines: 1969 the BMT Myrtle Avenue Line in Brooklyn, 1973 the IRT Third Avenue Line in the Bronx and 1975 the Culver Shuttle between Ninth Avenue and Ditmas Avenue in Brooklyn . The BMT Jamaica Line was withdrawn to Queens Boulevard station in 1977 .

Apart from its ambitious plans, the MTA had to contend with considerable problems. Local public transport increasingly turned out to be a subsidy business. The running costs could no longer be covered by the income from the fare. In any case, passenger numbers have been falling rapidly since the late 1960s. In addition, the political side no longer granted the funds for the second phase of the action program, and the city of New York also fell into a severe financial crisis , which in 1975 meant its de facto bankruptcy . As a result, construction work on Second Avenue was suspended and the money was used to cover the operational deficit. Further tariff increases to 50 cents were only able to provide a short-term remedy, so that drastic savings measures had to be initiated. Only the bare minimum should be repaired.

Another development also turned out to be disastrous. The years of effort to keep its budget balanced between spending and revenue from fares was the abduction of since the 1950s, a policy maintenance (deferred maintenance) due to a slow but steady decline of plant and vehicles moved to it. Furthermore, the powerful Transport Workers Union had implemented a generous pension scheme in 1968 , which provided for retirement after only 20 years of service without any transition period. As a result, around a third of the mostly very experienced employees immediately retired. The result was a dramatic shortage of skilled workers.

As in all of New York, crime in the subway increased in the 1970s, with thefts, robberies, shootings and murders increasing. The vehicles were more and more often provided with graffiti inside and out or damaged by vandalism . When the New York City Police Department was completely overwhelmed, the public reacted with discomfort. The subway was deliberately avoided.

A new low point was finally reached around 1980: the reliability of the vehicles was one tenth of the normal value, and 40 percent of the route network consisted of speed limits . Because there had been no main inspections since 1975 , a third of the vehicle fleet was idle due to serious technical defects. There were also logistical problems. Target signs were incorrectly equipped, spare parts were missing or were bought in far too large numbers, could not be found or could not be installed due to a lack of repair capacity.

Resurgence

It was not until the 1980s that an 18 billion dollar funding program for the rehabilitation of the subway was raised. In the 1990s, the city's strong economic recovery also contributed to improving the financial situation. Between 1985 and 1991, over 3,000 subway cars were overhauled and equipped with air conditioning . In this way, comfort, reliability and service life should be increased in order to be able to postpone new acquisitions. Only the oldest cars in each division were to be replaced, so that despite the fact that the fleet was actually outdated, only 1,350 new vehicles had to be purchased. Increased patrols and fences around the depots offered better protection against graffiti and vandalism, the previously most obvious symbols of decay. In addition, maintenance plans significantly improved the condition of the car.

At the same time, extensive rehabilitation of the routes began. Within ten years the tracks were renewed almost over their entire length. The Williamsburg Bridge and the Manhattan Bridge, which showed severe corrosion damage , were completely refurbished over the years. The renovation of the stations was initially limited to security measures, fresh paint, new lighting and signs. The MTA also tried to improve service, which had been neglected for just as long. This ranged from new uniforms and training for staff to correct destination signs on the vehicles. Some liner routes have also been adapted to the changing needs of customers.

Another declared goal was to reduce crime or at least improve the subjective feeling of security. In addition, the railway police and members of the newly founded Guardian Angels citizens' initiative patrolled the underground trains at night . In fact, it was not until the 1990s that crime in the city, and thus also in the subway, fell significantly. Nevertheless, the subway's reputation as a slow, dilapidated, dirty and unsafe means of transport continued to stick. In particular, pollution, poor signage and, in some places, ailing plant are still a problem today.

After 16 years of construction, the Archer Avenue Line was finally opened in 1988, including the new Jamaica transfer station with connections to the suburban trains on the Long Island Rail Road . A year later, the IND 63rd Street Line went into operation, which mainly serves to develop the new housing developments on Roosevelt Island that were built in the 1970s . It began at 57th Street station under Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, ran under the East River and ended on its east bank at 21st Street Queensbridge station . The construction work for the last 460 meters to the IND Queens Boulevard Line however, began in 1994 and lasted until 2001, so that the 63rd Street Line since the 1970s as a "tunnel to nowhere" ( "tunnel to nowhere") was mocked.

Renovation work on the stations began in the 1990s. In Manhattan, this was often done through major renovations, with guidance systems for the blind and, where possible, elevators being retrofitted. In 1994, after several years of testing, the magnetic stripe-based MetroCard was introduced as a cashless payment method. During the same period, test drives were run for a new generation of subway cars that were put into service from 2000.

The Coney Island – Stillwell Avenue station on the Atlantic coast, the common endpoint of four routes, was extensively renovated from 2001 to 2004. At the beginning of 2009, the new South Ferry terminus station replaced the old turning loop on Line 1 at the tip of Manhattan.

As part of the redevelopment of the World Trade Center area, a new, central transfer point was created between the six already existing stations in the financial district . The Fulton Center opened in 2014 and connects a new mall and reception building with the four stations of the Fulton Street complex. The World Trade Center Transportation Hub serves primarily as the PATH's new station , but provides access to Cortlandt Street Station on the R Line and the Fulton Center.

German companies are also involved in modernizing subway technology.

Ups and downs

At the end of October 2012, Hurricane Sandy flooded and damaged parts of the network. The MTA suffered a total loss of around 4.75 billion US dollars, the subway's share of this is likely to have been billions. Sections of the tunnel had to be pumped out and repaired. The new South Ferry station on Line 1, which opened in 2009, was so badly damaged that it could not be put back into operation until 2017. Repair work on the structural fabric of some of the underwater tunnels damaged by salt water will continue beyond 2020. On the basis of this experience, flood protection devices were installed or provided at low-lying stations, tunnels, depots and ventilation structures.

From the end of the 1990s, new lines were planned again. As part of the 7 Subway Extension to the west, the new terminus 34th St / Hudson Yards of the IRT Flushing Line was opened in September 2015 . A stopover in the area 41st St / 10th Ave was not realized. The first section of the Second Avenue Line , which had been planned since 1929 and repeatedly failed due to lack of funds , went into regular operation at the beginning of 2017 with three new stations. This route is used by line Q. In anticipation of the opening, the W line, which was canceled six years earlier, was reintroduced in 2016.

The 42nd Street Shuttle will be completely refurbished from 2019 to 2022 .

The annual number of passengers on the subway has risen year after year since its low point in 1982 and reached its highest level since 1950 in 2015. After the financial crisis from 2007 , the MTA opened two lines on the subway in 2010 (V, which has since been with the line M is linked, and W) and took before the bus cuts to a total of saving a high hundreds of millions. In New York’s economic boom in the 2010s, the subway suffered all the more from its lack of modernization and maintenance. This resulted in slowness, unreliability and overcrowding. The punctuality values fell back to the level of the 1970s. In the summer of 2017, operational safety was clearly no longer guaranteed and the Governor of New York State, Cuomo , declared a state of emergency for the MTA. After the punctuality values had bottomed out at 58 percent in 2018, they were increased to 80 percent under MTA chairman Andrew Byford and a downward trend in passenger numbers was initially reversed.

For the first half of the 2020s, the MTA planned a $ 51.5 billion modernization program that would largely benefit the subway and include the second section of the Second Avenue subway. However, in 2020 there was a Covid-19 pandemic in New York City , the unrest after the death of George Floyd with curfews, and a global economic crisis . While in March and April 2020 in the stations of the office districts of Manhattan and Brooklyn the occupancy fell to 5 percent of the normal value in some cases, in the residential areas of the workers and the lower middle class, utilization rates of around 25 to 35 percent were still recorded. Overall, the number of passengers fell at times by 92 percent year-on-year. Continuous night traffic, a unique selling point of the subway since it opened in 1904, was discontinued on May 6, 2020. Between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. there are only bus rides for passengers. In mid-August 2020, demand stabilized at almost 25% of the previous year's value, with a foreseeable upward trend.

The discontinued fare and other sources of income burden the current budget of the MTA so heavily that no major modernizations appear to be financially possible in the foreseeable future. Given the magnitude of the revenue shortfalls, conventional measures such as fare increases, layoffs or even the cancellation of entire lines could not even come close to compensating for them, especially as this could trigger an even stronger downward spiral than in the 1970s. The MTA sees a deficit of $ 16.2 billion out of a total annual budget of over $ 17 billion and is seeking a grant of $ 12 billion from the federal government for the period through the end of 2021.

Appearance

Almost the entire network of the New York subway that is used today, covering 370.1 kilometers, was built between 1904 and 1940. Buildings and technology have remained almost unchanged since then. Therefore, almost the entire network represents the state of that time, so that the subway is sometimes viewed as ancient and ailing. Despite extensive renovation of numerous train stations and operating facilities over the past 25 years, their old age is evident everywhere.

Only a few lines and stations were built after 1940. These are mostly short connecting pieces between existing routes or extensions in the area of the end stations. The most important new buildings were the 3.2 kilometer long first construction section of the Second Avenue Subway (opened in 2016) and the 3.0 kilometer long Archer Avenue Line (opened in 1988).

The New York Times estimates that a necessary restoration of the entire New York network would cost at least 100 billion US dollars.

tunnel

This is particularly evident in the first tunnels , which were mainly built as a steel frame in a top-down construction and run directly below the streets. Steel supports are anchored on the edges of the concrete foundation at intervals of five feet (1.524 meters) . Their upper ends connect cross girders , which in turn are supported between the individual tracks. Walls and ceilings were then closed with segmented concrete vaults. Reinforced concrete masonry was only used later , which greatly reduced the number of pillars required.

Elevated routes

Most of the elevated route sections date from the time of the double contracts and are mostly designed as full-walled steel support structures and predominantly painted blue-green. Every 50 feet (15.24 meters) along the route, a support is anchored in the ground on the left and right, the clear width of which is spanned by a solid cross-beam a good six feet (1.83 meters) high. Between these supports with a clear height of at least 14 feet (4.27 meters), three pairs of longitudinal girders of the same size are usually suspended, on each of which there is space for a track. The rails are mounted on wooden sleepers that basically rest directly on this supporting structure. In addition to some tight bends, this is the main reason for the noise level on such a route, which is sometimes felt to be unbearable.

A special feature of these elevated routes in New York is their name. A distinction is made between "Old Els" and "Elevated Subways" depending on the state of development. The former refer to the "old elevated railways" from the time before the subway was built. In particular, they have the property that they cannot be easily accessed by subway cars. In addition to the tight curves and the smaller track center distances, this is particularly due to their supporting structure, which is too weak for the heavy steel underground cars . This is due to the fact that the private builders and operators at the time had to save money due to the lack of state participation in these projects. In addition, lighter wooden vehicle bodies were standard before 1900.

In contrast to this, "Elevated Subways" denote , on the one hand, elevated sections of the route that have already been built as a subway and, on the other hand, that subset of the old elevated railways whose supporting structures have subsequently been brought up to the underground standard. This enabled trains that used the newly built tunnels in the city center to drive onto the existing elevated railways in the outskirts without the passengers having to change trains. Such modifications were mostly carried out in the course of the double contracts and turned out to be around 80 percent cheaper than building a new tunnel.

Of the Old Els, i.e. the old elevated railways without a reinforced structure, none are in operation today. They had become uneconomical because of their low traffic and were gradually shut down by the city after unification. In many places one of the then newly built underground lines of the Independent took over. In some places, however, political reasons were also decisive for the demolition of the elevated railways. After the lower part of the BMT Myrtle Avenue Line, the last Old El, went out of service on October 4, 1969, only the subways are left today, the designation of which sometimes causes confusion given the location above the street.

Other routes

A smaller part of the routes runs at ground level, on a railway embankment or in a cut. Due to their superstructure made of ballasted sleeper tracks, the routes are similar to those of conventional railway lines and are mostly derived from them. In some places, lush tree-like vegetation protrudes deep into the route.

Multi-track

Another New York peculiarity are routes with more than two operating tracks, which are found mainly on the heavily used routes in the city center. In the case of four-track sections, in addition to an outer pair of tracks for trains that stop at each station, the local tracks , and an inner pair of express tracks , the express tracks , are used for overtaking in the same direction . In the case of three-track sections, the middle track, the center track , is only used for this purpose in the respective main load direction , depending on the time of day. Similar configurations only exist on the Broad Street Subway in Philadelphia and on the Northern Mainline in Chicago. Four-track lines are partly laid out on two floors with two tracks on top of each other, partly with four tracks next to each other.

The train stations are also geared towards this operating pattern. While the local tracks have platforms at every station , the express tracks only have boarding options at selected stations, the express stations . Usually about every fourth to sixth station along a multi-track route is such an express train station, in the Midtown Manhattan area (around 31st to 59th streets) there are often several successive express train stations due to the very high passenger volume there and the important junctions there.

All stations that are not served by express trains are accordingly local stations .

If the express trains only run in the load direction on a line according to the timetable , they use the central passing track of the three-track lines. Stations with a three-track express stop each have a central platform between the express track and the respective local track in the corresponding direction of travel.

Train stations

Although the New York subway network has over 400 stations, in most cases they have been built to at least some unofficial standards. A distinction can be made between tunnel location, elevated and ground-level systems.

A typical New York subway station initially has two outer platforms , regardless of its location and the number of tracks . On routes with more than two tracks, these only ever serve the lover track pair. Express stations, on the other hand, usually have two central platforms , which allow transfers in the same direction. In the case of three-track sections, the middle track is served by both platforms, with the train doors only being opened on the right in the direction of travel.

At the underground stations, comparatively narrow stairways with typical green railings lead from the street to a distribution level where the ticket machines and the barriers are located. The size of the distribution level depends on the importance of the respective station and the number of platforms. Smaller stations usually have no indented pedestrian level at all, so the barriers are located directly on the lower landing, after which you are immediately on the platform. Such entrances are marked with an addition such as "Uptown & The Bronx", which explains the direction of travel at the respective platform. At some of these exits there is not even a ticket machine.

The architecture of the tunnels continues seamlessly, especially at older train stations. Because the stability of steel at this time did not allow large clearances between the supports, there are often many rows of columns along the platforms and tracks, some of which run directly in front of the platform edge. In many cases, the room height does not exceed that of the adjacent tunnels. Above the platforms it is sometimes a little lower because of suspended lamps and supply lines . The MTA has been trying to counteract the resulting tightness and compactness for some time with improved lighting.

The design of the underground stations also shows significant differences between the stations of the IRT , which mostly opened between 1904 and 1918, and the stations of the IND, which mostly opened between 1932 and 1940 . The IRT train stations often do not have a mezzanine level, even if they are heavily frequented, centrally located train stations such as 50th Street on Line 1. Furthermore, due to the limited technical possibilities at the beginning of the 20th century, the IRT train stations are mostly directly below street level and appear very narrow due to the low ceiling height. The IND, whose aim was to drive the IRT out of business through competition, wanted to inspire passengers from the start with more comfortable trains and stations. Almost all IND train stations were designed with spacious mezzanines that stretched over the entire length of the platform. Technological progress made it possible to make the room height on the platform level a little higher and thus more friendly and to make the support columns on the platforms slimmer. The support columns between the individual tracks were completely eliminated, so that the stations as a whole gave a lighter and more spacious impression. In addition, the system was designed for high numbers of passengers, so the platforms even in the outer area of the routes often had six to eight staircases to the mezzanine and no fewer stairs from the mezzanine to the street.

However, the extremely generous construction of the IND turned out to be oversized even for New York. Little by little, countless staircases and mezzanines were completely or partially closed, especially in the 1980s, to prevent crime in the spacious and often deserted mezzanines. Today there are staircases barred with bars at countless former IND train stations - often also in Manhattan. Some of these were dismantled at street level and built over with the usual concrete slabs for New York pedestrian walkways, so that no remains can be seen at street level. In the mezzanine floors, different wall tiles often show that originally continuous mezzanines were built back onto the entrance areas at the platform ends. The areas in between are often used as storage rooms

In the case of the Elevated Subways, narrow fixed staircases, which are mostly enclosed, lead from the sidewalks either via a distribution level above the street or, more rarely, directly onto the platforms. Only relatively high stations such as 125th Street in Manhattan or Smith / 9 Streets in Brooklyn are additionally equipped with escalators . The platforms are usually planked with wooden panels and mounted on two steel longitudinal beams. In addition, there is usually a sheet metal roof over at least half the length . Instead of a railing, a vestibule made of white painted profiled sheet metal often serves as a rear boundary. The names of the stations are not always clear. On the one hand, the name of a crossing station can be different depending on the route, on the other hand, there can be several stations on a street with the same name but a considerable distance from one another. For example, there are five 23rd Street on the street of the same name in Manhattan.

Most train stations are not suitable for the disabled. This is not only due to the fact that no attention was paid to it at the time of the underground construction. The subsequent installation of escalators and elevators is also difficult and therefore expensive due to the often limited space available, so that up to now only heavily frequented or conveniently located stations have been equipped with them. However, new stations, such as the South Ferry Station, which was completed in 2009, will be equipped with escalators and elevators according to US law.

Route network

The New York subway distinguishes between routes and lines. A line is initially equivalent to a railway line , i.e. a connection with a railroad. As a rule, it has its own kilometrage and exists independently of the actual traffic. However, some of the delimitations are more popular than the actual route. A line designation is not synonymous with a specific route on the New York City Subway , as is the case in Berlin , Hamburg or Munich .

Naming

All sections of the subway have their own names. These are derived, for example, from the destination, as in the case of the Flushing Line and the Pelham Line from the districts of the same name, Flushing and Pelham ; or the main street (street , boulevard or avenue) is the namesake, as is the case with the Fourth Avenue Line or the Broadway Line. It has become common practice to put the abbreviation of the respective operating company in front of it because the names were not always clear in the past. For example, in addition to the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) subway under Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, the IRT Lexington Avenue Line, until 1950 there was still an elevated BMT railway of the same name on a street with that name in Brooklyn, the BMT Lexington Avenue Line .

One of the efforts to consolidate the subway after unification was to officially stop using those prefixes. This seemed possible after the closure of "ambiguous" routes. But the population has hardly adopted this practice to this day. Likewise, the plan failed, instead of that path name officially only the line designations for orientation to use the many line changes within the Division B .

Profiles and Divisions

Most of today's route network was built more or less independently of one another by the three companies, the IRT , the BRT / BMT and the Independent . After the unification of the U-Bahn in 1940, this division of the routes along those borders into the IRT Division , BMT Division and IND Division was initially retained because there were hardly any track connections, so the three sub-networks practically existed side by side.

The IRT routes have a narrower clearance profile so that they cannot be used by vehicles from the other two departments. Conversely, on a route with a wide profile, the gap between the platform edge and the car floor would be too large when using the narrower cars. This fact stems from the fact that Interborough built its underground network according to the standards of the old elevated railways, which for reasons of space and weight could only use narrow vehicles. Both the BRT and the Independent, however, were based on the profile of a main railway .

The technical equipment is in principle identical for narrow and wide-profile routes, so that joint operation on the same route is basically possible. This was the case, for example, between 1917 and 1949 on the Flushing Line and the Astoria Line. Work trolleys can be used equally on any route, provided they have a narrow profile.

The long-term plan is to convert all narrow-profile routes to wide-profile ones. Because all underground sections of the IRT from Contracts No. 1 and No. 2 would de facto have to be rebuilt, this project is not expected to be implemented anytime soon. The stretches on the surface, however, cause fewer problems; As a rule, only the platform edges have to be cut there. This happened, for example, in 1949 on the BMT Astoria Line.

After the construction of some connecting tunnel between the networks of the BMT and the Independent these two route groups were from 1967 under the name Division B combined, and that of the IRT as Division A designated. Today, however, the term division refers to profile and rolling stock. “Division A” is a synonym for narrow profile, “Division B” for wide profile. The C Division summarizes the most narrow-profile work and special vehicles together. The old division of the routes into IRT, BMT and IND remained in the public perception until today and is still used internally by the MTA.

IRT

The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) developed mainly Manhattan and the Bronx with its route network. It was divided into two groups, the "Subway Division" and the "Elevated Division". After the merger, it became the IRT Division .

As the subway division ("U-Bahn department"), the IRT referred to the routes that it had built under the first two contracts, and the associated extensions under the double contracts. Thus, those elevated lines also belonged to the subway that these trains used and led into their tunnels.

The Subway Division comprised the two main routes of the IRT under Seventh Avenue and Manhattans Lexington Avenue, the IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line and the IRT Lexington Avenue Line . Together with the 42nd Street Shuttle , these two north-south routes formed the so-called "H-System" . The name comes from its route on a map here, which to a large H recalls.

The Subway Division also included the IRT Eastern Parkway Line and the IRT Nostrand Avenue Line in Brooklyn , the IRT Lenox Avenue Line in Harlem and the IRT Jerome Avenue Line , the IRT White Plains Road Line and the IRT Pelham Line in the Bronx . The IRT Dyre Avenue Line was only added a year after the merger.

Under the Elevated Division ("Hochbahn -teilung") the four Manhattan elevated railways were summarized, which were named after the streets they traveled on ( IRT Second Avenue Line , IRT Third Avenue Line , IRT Sixth Avenue Line and IRT Ninth Avenue Line ). The division happened regardless of the fact that some sections had already been converted to the underground standard. After the unification, these routes were gradually taken out of service and broken off. The last elevated railway section on Manhattan Island was shut down on August 31, 1958, and operations on the northern section of the IRT Third Avenue Line ended on April 28, 1973. This meant that the last section of the former Elevated Division of the IRT went out of operation, although the modern underground cars were already in use there.

- IRT

Viaduct on Broadway at 125th Street

BRT / BMT

The route network of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company and later Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation mainly covered Brooklyn , Williamsburg , Bushwick and the southern part of Manhattan . Here, too, the route network was divided into groups, namely the "Southern Division", the "Eastern Division" and the "Queens Division". Since the unification of the U-Bahn, sections within the BMT Division have been used in this context .

The Southern Division ("southern routes") of the BMT summarized all routes coming from Manhattan via the DeKalb Avenue station in downtown Brooklyn towards the Atlantic coast. Historically, these are excursion trains to Coney Island and the connected subway tunnels that were created in the course of the double contracts. These are the BMT Fourth Avenue Line , the BMT West End Line , the BMT Sea Beach Line , the BMT Brighton Line and the BMT Franklin Avenue Line . The BMT Broadway Line and the Manhattan Bridge were also assigned to this group. The BMT Culver Line was one of them until it was connected to the main lines of the Independent in 1954.

To the Eastern Division , the " Eastern Lines", all other lines of the BMT were counted. In addition to the BMT Canarsie Line , the BMT Jamaica Line , the BMT Myrtle Avenue Line and the BMT Liberty Avenue Line , which are at least mostly still in operation today, this also included the old elevated railways in Brooklyn. These were the BMT Third Avenue Line , the BMT Fifth Avenue Line , the BMT Fulton Street Line , the BMT Lexington Avenue Line and the tracks over the Brooklyn Bridge .

The internal network limits defined in this way are reflected in maintenance and the fleet of vehicles used, as well as in regular operation. Despite a few track connections, there was hardly any traffic across both divisions, which has basically not changed to this day. The lines of the Eastern Section, J, L, M and Z operate de facto separately from the rest of the network of Division B.

There was another specialty in Queens: At the Queensboro Plaza station , several routes came together from the direction of Manhattan. From the IRT the underground line from the Steinway tunnel and the elevated railway from the Queensboro Bridge , and from the BMT the Broadway line. Behind the station, the route forked into a northern branch, the Astoria Line , and another branch to the east, the Corona Line and later the IRT Flushing Line . These two routes were operated jointly by the IRT and the BMT and assigned to the Queens Division ("Queens Department") . After the end of the joint operation in 1949, the Astoria Line was added to the Southern Section of the BMT Division , while the Flushing Line went to the IRT Division .

- BRT / BMT

The Canarsie Line in Bushwick

The Sea Beach Line with the express train to Coney Island

In addition, a number of lines were assigned to the BMT Division, which were only built after 1940. The BMT 63rd Street Line and the BMT 60th Street Tunnel Connection are connecting tunnels from the BMT Broadway Line to lines of the Independent. And the BMT Archer Avenue Line has replaced the outermost section of the BMT Jamaica Line since 1988 .

Independent

The network of the Independent Subway and later the IND Division was planned and built as a unit in the 1920s, so that there were no historically based route divisions. The core of this third New York subway network were two trunk lines under Manhattan's Sixth and Eighth Avenue, the IND Eighth Avenue Line and the IND Sixth Avenue Line . These crossed at 53rd Street, Fourth Street and again in Brooklyn at Jay Street – Boro Hall station .

From the northern end of this double network of fish bladders, the Eighth Avenue Line continued to Washington Heights , the IND Concourse Line to the Bronx and the IND Queens Boulevard Line to Jamaica under the street of the same name . At the southern end in Brooklyn, it went east on the IND Fulton Street Line to East New York and south on the IND Culver Line to the foot of the BMT Culver Line . The IND Crosstown Line ran from downtown Brooklyn, bypassing Manhattan over to Long Island City , Queens.

When the World's Fair took place in Flushing Meadows Park in 1939/1940, a branch was built from Forest Hills – 71st Avenue station of the IND Queens Boulevard Line, the IND World's Fair Line . It was dismantled after the end of the event in October 1940 and is the only disused section of the Independent next to Court Street station .

After the unification of the underground, a few more sections were added. The newly built IND Fulton Street Line replaced the last section of the parallel BMT Fulton Street Line in 1956 . At the same time, a branch line to the Rockaway Peninsula, the (IND) Rockaway Line, went into operation from Rockaway Boulevard station . This formed a separate department, the Rockaway Division , until 1967 .

The IND Chrystie Street Connection are also included in the IND Division . It allows trains coming from the Southern Division of BMT over the Manhattan Bridge from Brooklyn to the Independent's trunk lines in Manhattan. Its completion in 1967 is considered the birth of B Division . In addition, some new lines from the period after 1940 are included in this line group. These include the IND 63rd Street Line , the IND Archer Avenue Line, and the Second Avenue Subway .

Disused and unused routes

The New York subway is one of the few networks in the world that has disused routes. The abandoned old elevated railway lines make up the largest part of this, the remains of which are still visible in many places. In the course of time, some preliminary construction work was carried out for planned, but ultimately never realized routes.

The Old Els can usually only be seen where they were once connected to other, still existing routes. For example, the elevated Gun Hill Road station on the IRT White Plains Road Line has a second level under the subway that was once used by the IRT Third Avenue Line . The branch of the IRT Ninth Avenue Line can also be seen on the IRT Jerome Avenue Line at 167th Street station . The tunnel under 162nd Street and the foundations of the Jerome Avenue and Sedgwick Avenue stations have even been preserved here.

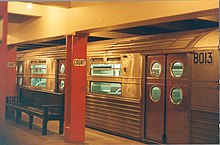

The Ninth Avenue - Ditmas Avenue section in Brooklyn, which was de facto replaced by the Culver Ramp in 1954 and finally abandoned in 1975, is one of the decommissioned Elevated Subways . The tracks and platforms on Ninth Avenue still exist and are occasionally used for filming. At the other end of the route on Ditmas Avenue you can still see the junction of the former route. Also opened in 1976 in New York Transport Museum ( New York Transit Museum ) is located in a disused subway station.

The largest part of the unredeemed construction work is due to the planning for the Second Independent System . In the process, crossing and branching stations were built in some places , but these are only partially in operation today. However, this fact is usually not immediately recognizable because the additional operating facilities are either not accessible or are used for other purposes. The ceiling construction in the Utica Avenue station on the IND Fulton Street Line in Brooklyn shows the shape of two central platforms including track beds, which belong to the planned IND Utica Avenue Line. Another example is 2 Avenue Station in Manhattan. There the two middle platform tracks form the stump of a link over to Williamsburg that was never built . Until 2010 the trains of line V turned there, today only special trips.

When the routes of the Triborough plan were included in the double contracts, the construction plans were changed in some places afterwards. In the area of the City Hall station on the BMT Broadway Line , another platform level was created, which is now superfluous and serves as a parking facility.

Another peculiarity occurs with the main routes of the IRT in Manhattan. When the platforms for ten-car trains were extended in the 1950s, some stations were left out in order to shut them down and thereby increase the travel speed . The platforms are still there, but have been passed through without stopping since then.

Especially in Manhattan, unused and apparently superfluous platforms are also noticeable in many stations. They are the result of changes in traffic flows over time, such as the relocation of the main business district from the southern tip of Manhattan to Midtown . As a result, the number of passengers at certain train stations fell, so that the additional effort was no longer justified. In other places there were platforms that opened up a service track from both sides, which proved impractical and were therefore abandoned.

Route plans

In 1979, the graphic designer Michael Hertz published a route map, which has remained the benchmark in its graphic layout to this day. When it first appeared, the map was praised for its clarity and clarity. On it, the dimensions of the individual parts of the city are not proportional, but rather compressed or stretched out. Some important landmarks, such as major streets, Central Park, etc. are also drawn in for better classification. Because of its catchiness and comprehensibility, the card achieved iconic status.

Announcements

The announcements (announcements) in New York usually consist of two parts:

- During the stop, the direction of travel and the next stop (without changing options) are announced: This is an 8th Avenue-bound L train, the next stop is 14th Street - Union Square . (This is an L train to 8th Avenue, next stop is 14th Street - Union Square.)

- Shortly before arriving at the station, the transfer options are announced: This is 14th Street - Union Square. Transfer is available to the 4, 5, 6, N, Q, R, and W trains. (This is 14th Street - Union Square. Transfer to Lines 4, 5, 6, N, Q, R and W.)

In the case of lines traveling on the same route, transfer options to these lines are normally only announced if there is a connection to other lines that do not travel on the same route.

Announcements at the end stations:

- With the announcements during the journey: The next and last stop is ... (The next and last stop is ...)

- After the eventual change announcements: This is the last stop on this train. Everyone please leave the train. Thank you for riding with MTA New York City Transit. (This is the last stop on this train. Everyone, get off. Thank you for taking the MTA New York City Transit.)

- Since it is permitted to remain seated on the train in the loop of Line 6 (e.g. to see the closed City Hall station) , the following, different announcement sounds at the terminus, Brooklyn Bridge - City Hall : Ladies and gentlemen, this is the last downtown stop on this train. The next stop on this train will be Brooklyn Bridge - City Hall on the uptown platform. (Dear Sir or Madam, this is the last downtown stop of this train, the next stop of this train will be Brooklyn Bridge - City Hall on the Uptown platform.)

The following special announcements are also made:

- The announcements of the express line

are: This is a Pelham Bay Park-bound 6 train making express stops in the Bronx. (This is a line 6 train to Pelham Bay Park that stops at express stations in the Bronx (only))

are: This is a Pelham Bay Park-bound 6 train making express stops in the Bronx. (This is a line 6 train to Pelham Bay Park that stops at express stations in the Bronx (only)) - For diversions: This is a Queens-bound M train via the E line. (This is an M train to Queens across the E route)

- Special transfer options:

- A free transfer is also available to the F train by walking to Lexington Avenue-63rd Street station and using your Metrocard. (Possibility to change by foot and Metrocard)

- Transfer is available to the M34 Select Bus Service. (Transition to an SBS line; similar to the German metro buses , but here the M stands for Manhattan)

- Transfer is available to the M60 Bus to LaGuardia Airport. (Transfer to bus M60 to LaGuardia airport)

- Connection is available to Metro-North , Long Island Railroad , Staten Island Ferry , New Jersey Transit , PATH and Amtrak . (Possibility to change to various S-Bahn, ferries, regional subways and long-distance trains)

Lines

In contrast to the routes, the lines (routes or services) designate the traffic actually taking place as a group of trains that serve a certain sequence of stops. Their numbering and processes have changed profoundly several times over time.

The difference to the routes becomes clear in the context: trains of line D ("the D service") travel one after the other in the Bronx the IND Concourse Line , in Manhattan first the IND Eighth Avenue Line , then their main route under the Avenue of the Americas , the IND Sixth Avenue Line , then the IND Chrystie Street Connection and in Brooklyn finally the BMT Fourth Avenue Line and the BMT West End Line . Likewise, a resident of 86th Street in south Brooklyn would not say they live “on Line D” but “on the West End Line”. But after he got on he would say: “I am on a D train” (“I'm in the D-Bahn”).

The numbering is done according to a certain pattern. Lines that travel on the narrow-profile routes of division A are numbered from 1 upwards. Lines of the wide-profile division B, on the other hand, are marked with a letter, whereby the former IND division can be found earlier in the alphabet for historical reasons. Pendulum traffic (shuttles) are always marked with "S". The current system has been in effect since May 5, 1986. The color, on the other hand, has been showing the main line of a line since June 1979.

Furthermore, lines are divided into strollers (locals) and express trains (expresses) . The difference lies in whether a train uses the lover track pair (local tracks) on a certain route and stops accordingly at every station, or travels on the express tracks and does not stop everywhere. The designation of a line as "Local" or "Express" is only derived from the behavior on the main route it travels. The full names of the lines are then for example "A Eighth Avenue Express" or "6 Lexington Avenue Local" .

Regardless of this, trains can run very differently on an outer branch than on their main line. For example, Line F is a Sixth Avenue Local, but trains run as an express on the IND Queens Boulevard Line . Conversely, Lines B and D are Sixth Avenue Expresses, but further north, on the IND Eighth Avenue Line between 59th Street – Columbus Circle and 145th Street , Line B is a Local and Line D is an Express. In the past, such "mutations" have repeatedly been the cause of changes to lines and designations. In the meantime, however, the situation seems to have stabilized; there have been no major changes in over twenty years.

Some lines run on the outer branches depending on the time of day in the main load direction both as local and as express, for example line 7. The behavior can be recognized here by the shape of the line symbol: Locals drive with a round, an express with a diamond-shaped logo as a so-called diamond service .

To shorten the travel time, some less frequented stops are only served alternately by two lines that run there at rush hour ( skip-stop operation) . The trains alternately stop at every second station on certain sections of the route. This is currently (2016) only the case on the inner section of the BMT Jamaica Line at line J, where it is reinforced there by line Z. The procedure was similar on the IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line, where line 9 operated as a repeater for line 1 between August 21, 1989 and May 27, 2005.

The following table shows the status from the beginning of 2017 on working days during the day.

| card | line | Surname | route | routes traveled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRT (Division A) | ||||

| via IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line | ||||

|

|

Broadway-Seventh Avenue Local | Van Cortlandt Park- 242nd Street - South Ferry | IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line |

|

|

Broadway-Seventh Avenue Express | Wakefield - 241st Street - Flatbush Avenue - Brooklyn College | IRT White Plains Road Line , IRT Lenox Avenue Line , IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line , IRT Eastern Parkway Line , IRT Nostrand Avenue Line |

|

|

Broadway-Seventh Avenue Express | Harlem-148th Street - New Lots Avenue | IRT Lenox Avenue Line, IRT Broadway - Seventh Avenue Line , IRT Eastern Parkway Line |

| via IRT Lexington Avenue Line | ||||

|

|

Lexington Avenue Express | Woodlawn - Crown Heights-Utica Avenue | IRT Jerome Avenue Line , IRT Lexington Avenue Line, IRT Eastern Parkway Line |

|

|

Lexington Avenue Express | Eastchester-Dyre Avenue - or (Nereid Avenue -) Bowling Green - Flatbush Avenue-Brooklyn College | IRT Dyre Avenue Line, IRT White Plains Road Line, IRT Jerome Avenue Line, IRT Lexington Avenue Line, IRT Eastern Parkway Line, IRT Nostrand Avenue Line |

|

|

Lexington Avenue Local (Pelham Local) |

Pelham Bay Park - Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall | IRT Pelham Line, IRT Lexington Avenue Line |

|

|

Lexington Avenue Local (Pelham Express) |

(Pelham Bay Park -) Parkchester - Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall | IRT Pelham Line, IRT Lexington Avenue Line | |

| via IRT flushing line | ||||

|

|

Flushing local | Flushing-Main Street - 34th Street-Hudson Yards | IRT flushing line |

|

|

Flushing Express | Flushing - Main Street - 34th Street - Hudson Yards | IRT flushing line | |

| Shuttle services | ||||

|

|

42nd Street Shuttle | Times Square-42nd Street - Grand Central-42nd Street | IRT 42nd Street Shuttle |

| BMT / IND (Division B) | ||||

| via IND Eighth Avenue Line | ||||

|

|

Eighth Avenue Express | Inwood-207th Street - Ozone Park-Lefferts Boulevard or - Far Rockaway – Mott Avenue or (- Rockaway Park-Beach 116th Street) | IND Eighth Avenue Line , IND Fulton Street Line, IND Rockaway Line |

|

|

Eighth Avenue Local | 168th Street - Euclid Avenue | IND Eighth Avenue Line, IND Fulton Street Line |

|

|

Eighth Avenue Local | Jamaica Center – Parsons / Archer - World Trade Center | IND Archer Avenue Line, IND Queens Boulevard Line, IND Eighth Avenue Line |

| via IND Sixth Avenue Line | ||||

|

|

Sixth Avenue Express | (Bedford Park Boulevard -) 145th Street - Brighton Beach | (IND Concourse Line,) IND Eighth Avenue Line, IND Sixth Avenue Line, IND Chrystie Street Connection, BMT Brighton Line |

|

|

Sixth Avenue Express | Norwood-205th Street-Coney Island-Stillwell Avenue | IND Concourse Line, IND Eighth Avenue Line, IND Sixth Avenue Line, IND Chrystie Street Connection, BMT Fourth Avenue Line, BMT West End Line |

|

|

Sixth Avenue Local | Jamaica-179th Street-Coney Island-Stillwell Avenue | IND Archer Avenue Line, IND Queens Boulevard Line, IND 63rd Street Line, IND Sixth Avenue Line, IND Culver Line , BMT Culver Line |

|

|

Sixth Avenue Local | Middle Village-Metropolitan Avenue - Forest Hills-71st Avenue | BMT Myrtle Avenue Line, BMT Jamaica Line, IND Sixth Avenue Line, IND Queens Boulevard Line |

| via IND Crosstown Line | ||||

|

|

Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Local | Long Island City-Court Square - Church Avenue | IND Crosstown Line, IND Culver Line |

| via BMT Nassau Street Line | ||||

|

|