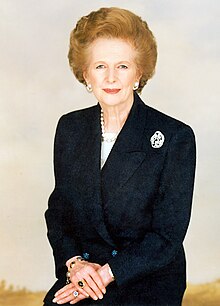

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (* 13. October 1925 as Margaret Hilda Roberts in Grantham , Lincolnshire , † 8. April 2013 in London ) was a British Staatsfrau and conservative politician .

While studying chemistry at Somerville College ( Oxford ), Thatcher decided in 1945/1946 to become politically active and ran for the lower house for the first time in 1950 . In 1959 she was elected as a member of the lower house of parliament for the Conservative Party . From 1970 to 1974 she was Minister of Education and Science in the government of Edward Heath . In a battle vote for the office of party leader, she defeated him in 1975 and remained party leader until 1990.

After the Conservative Party won the 1979 general election, Thatcher was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 4, 1979 to November 28, 1990 . She was the first woman to hold this office and has held it continuously longer than any other British Prime Minister of the 20th century. The victory of the British military in the Falklands War (1982) cemented her reputation as the " Iron Lady " and was a decisive basis for subsequent election victories for the Conservatives. In terms of foreign policy, Thatcher leaned closely to the USA and followed a tough anti-communist course. On the other hand, after initial sympathy, she was increasingly hostile to the ongoing process of European unification. Under their aegis , extensive deregulation , especially of the financial sector, and a more flexible labor market legislation were implemented, state-owned companies were privatized on a large scale and the influence of the British unions was broken.

Thatcher is considered one of the most controversial political figures of the post-war period. Adored and iconized by her followers, she is equally despised and reviled by her opponents. She was named after Thatcherism and is portrayed as a formative figure of the 1980s in many songs, films, books and plays.

Life

Family, studies and work

Margaret Thatcher was born Margaret Hilda Roberts on October 13, 1925, the younger of two daughters. Her parents came from the lower middle class. Her father Alfred Roberts from Northamptonshire was a grocer and mayor of her native Grantham and worked as a Methodist lay preacher . Her mother Beatrice Ethel Roberts b. Stephenson from Lincolnshire was a trained house tailor. While Thatcher also in later years liked to cite and idealize her father as an early role model she admired, she never showed any public affection for her mother. Her sister Muriel later described her mother as a " bigoted Methodist " with whom she and Margaret would not have been closely related. "Mother didn't exist in Margaret's head." The family lived in an apartment above the father's shop, where Margaret and her sister helped out. In later years she often referred to her father's shop, where she had an early understanding of the rules of free enterprise. The Christian faith imparted to her by her father also played a major role in Thatcher's later life; as a politician she often used religious metaphors and ostentatiously presented herself as a practicing Christian. She presented her personal view of the relationship between Christianity and politics in her well-known speech Sermon on the Mound in 1988. At times there was a Jewish child in her family who had fled the German Reich . She later witnessed the German Air Force attacks on her hometown during World War II .

After she had attended elementary school in Kesteven and the girls' high school in Grantham on a scholarship , Margaret Roberts studied chemistry at Somerville College in Oxford from 1943 . There she took little part in social life, but joined the Oxford University Conservative Association (OUCA). In 1947 she obtained her bachelor's degree in chemistry, and last year she wrote a thesis on X-ray crystallography of an antibiotic ( gramicidin ) for the later Nobel Prize winner Dorothy Hodgkin . She worked as an industrial chemist for four years and had her first job with British Xylonite Plastics. In 1950 she moved to the food company J. Lyons & Co., as her political home was in Dartford ( Kent ). According to various anecdotes, she was also involved in the development of soft ice cream there . What is certain is that she worked on improving the consistency and quality of cakes and ice cream.

Entry into politics

After Margaret Roberts had decided to be politically active around 1945/1946, she ran in the 1950 elections as a conservative candidate for the Dartford constituency for the first time for the House of Commons , but lost clearly in the Labor stronghold. Nevertheless, she was noticed by a wider public as the country's youngest female candidate. She expected to get a safe constituency for the next election, but the party establishment preferred less capable candidates, as Richard Aldous stated in 2009.

In December 1951 she married the wealthy divorced businessman Denis Thatcher . No longer dependent on her own income, Margaret Thatcher began another study soon after her marriage, this time in law . She then worked briefly as a lawyer for tax law . The twins Carol and Mark , who she gave birth to on August 15, 1953, were born from her marriage to Denis Thatcher . Through the influence of her husband, Thatcher began to turn to Anglicanism and later converted. In the general election of 1955 , she did not run to focus on her family.

After that, however, she began to look for a more promising parliamentary seat. In the 1959 election , Thatcher won the House of Commons with a narrow victory for the Finchley constituency in the northern London borough of Barnet . She gave her first speech there on February 5, 1960. In 1961, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan appointed Thatcher to the position of Parliamentary Secretary of State in the Department of Social Security, a promotion that was largely driven by Macmillan's aim to have at least three women in positions of responsibility to have his government. During this time Thatcher supported Macmillan's political course and in 1979 still called him the politician of the 20th century she admired the most.

In the 1960s, she advocated legalizing homosexuality and abortion , but opposed the abolition of the death penalty and expressed sympathy for law-and-order methods . She also supported the unsuccessful British applications for membership of the European Economic Community . After the Conservatives had suffered a narrow electoral defeat in 1964 , Thatcher was initially entrusted with the same area of responsibility in the opposition, from April 1966 onwards as deputy to the shadow chancellor Ian McLeod . Finally, Thatcher was appointed to his shadow cabinet in 1967 by the new party leader Edward Heath . A six-week trip through the US that same year sparked Thatcher's enduring enthusiasm for the country. For Thatcher, the USA became the ideal image of a free society and a free market economy. In addition, she began to take an open interest in market-liberal ideas as propagated by the Institute of Economic Affairs ; conversely, other free market economists (such as Geoffrey Howe ) did not regard her as “one of their own” until the 1970s. Thatcher later admitted her own, only gradual, conversion to the business-friendly ideas of neoliberalism .

In 1970, Thatcher became Minister of Education in Edward Heath's cabinet. In this role, she abolished free milk in elementary schools, among other things, which earned her the reputation of the “ milk thief” with the word game Milk Snatcher . In 1972 she campaigned with great energy for Britain to join the European Economic Community . In addition to the general effects of the oil crisis, the Heath administration was also hit by a series of severe strikes and was forced to temporarily implement a three-day week. In order to save energy, there were power cuts. Several commentators subsequently described Britain as the "sick man of Europe". Prime Minister Heath therefore called elections with the campaign slogan “Who rules Britain?” In order to be confirmed. In the general election on February 28, 1974 , Heath's Conservatives suffered a defeat; there was a hung parliament (for the first time since 1929 ) - no party had achieved an absolute majority. The Labor Party formed a minority government under Prime Minister Harold Wilson and reached a compromise with the unions. Wilson called new elections for October 1974 , in which Labor received a slim majority of the lower house seats.

Opposition leader

| First round February 4, 1975 | |

| Margaret Thatcher | 130 |

| Edward Heath | 119 |

| Hugh Fraser | 16 |

| Abstentions | 11 |

| Second round February 11, 1975 | |

| Margaret Thatcher | 146 |

| William Whitelaw | 79 |

| Geoffrey Howe | 19th |

| James Prior | 19th |

| John Peyton | 11 |

| Abstentions | 2 |

Candidate for party leadership

After the renewed defeat, especially within the parliamentary group of the Conservative Party, there was growing disillusionment and dissatisfaction with its party leader, who had now lost three out of four elections. Heath was also resistant to advice and unable to acknowledge its own mistakes. The influential chairman of the 1922 committee , Edward du Cann , called on the conservative backbenchers Heath on October 13 to stand for a new election within the party. After Heath initially resisted the demand and sought a trial of strength with the members of the committee, he finally had to bow down in November and agree to a new election.

In late November, Thatcher announced her own candidacy after party right wing leader Keith Joseph decided against running her own . Although she was praised as a talented politician in the press and her candidacy was openly supported in the Sunday Times , she was considered an outsider. On February 4, 1975 she stood against Edward Heath as party leader of the Conservatives and first won the first round of a fight vote with 130 to 119 votes against Heath, who then resigned from the party leadership . In the second round on February 11, 1975, she beat, among other things, the favorite William Whitelaw , who had renounced his own candidacy out of loyalty to party leader Heath in the first round. Thatcher was particularly able to benefit from the votes of the 1922 committee in her successes, perceived as surprising. After her victory, she immediately named Whitelaw her deputy, who would become Thatcher's most loyal supporter for years to come. The defeated Heath, on the other hand, developed into an implacable personal opponent of Thatcher who, increasingly isolated over the years, opposed Thatcher's policies at every opportunity.

Thatcher as opposition leader

As the leader of the opposition, Thatcher soon threw off proposals within the party to continue to advocate the so-called "middle way", which had been advocated primarily by her conservative predecessors Macmillan and Anthony Eden , and instead promoted the ideas of the economist Friedrich Hayek within the party . In addition, she gathered convinced monetarists who also campaigned for a rethink in economic policy. However, she only succeeded gradually in promoting them to prominent posts; their shadow cabinet continued to consist to a large extent of traditional Tories , who rather sympathized with their predecessor Heath.

Due to the desperate economic situation in Great Britain in the late 1970s and in particular the Winter of Discontent , the government of Labor Prime Minister James Callaghan continued to lose popularity; At the same time, Thatcher was increasingly determined to operate a complete departure from the previous policy of consensus of the "middle way" , which made them responsible for the steady British decline. She found the sterling crisis of 1976 and the subsequent use of a loan from the International Monetary Fund a national humiliation for Great Britain. In addition, she emphasized Victorian values and declared the economic crisis as an expression of a fundamental spiritual crisis of the nation.

In her speeches, she often deliberately imitated Winston Churchill's rhetoric . In contrast to her predecessors, she maintained a close relationship with the party's backbenchers, who were also taken with her aggressive and sometimes populist rhetoric. The nickname "Iron Lady", which she loved, comes from a comment on Radio Moscow in 1976 after she sharply attacked the " Bolshevik Soviet Union " in the so-called Kensington address and accused the Soviet Politburo of global military To strive for dominance.

The conservative election campaign in 1979

In early April 1979, Prime Minister Callaghan dissolved parliament and held new elections for May 1979. The Conservative election campaign was based on a negative and a positive aspect. The freedom of the individual was highlighted positively. In addition to the individual, Thatcher's election campaign emphasized the need for lower government spending, a reduction in bureaucracy and a reduction in tax levies. On the other hand, the mistakes of the Labor government, the unreasonable conditions in the strike-ridden Winter of Discontent , the failure of the Labor promise to cooperate with the trade unions and the need to legally prohibit gross violent picket line violations were emphasized negatively . For the first time the advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi was commissioned, which carried out an aggressive poster campaign against Labor under the advertising slogan “Labor Isn't Working” and alluded to the rising unemployment figures. The campaign was considered to be groundbreaking and was copied in later elections. The conservative election manifesto was entitled Time for a change . In the preface, Thatcher wrote that the upcoming election may be the last opportunity to restore the proper balance between the state and the individual. As in 1970, the Conservative campaign focused on 80 constituencies in which tight results were expected. A new target group was identified as the electorate of the qualified working class, who were seen as swing voters and were considered receptive to Thatcher's ideas. Analyzes had shown that this group, whose incomes had been rising for years, were just as dissatisfied with the high taxation and the mistakes of the Labor government as, for example, the group of top earners. According to surveys, these groups agreed to a partial dismantling of the welfare state.

In the general election of May 3, 1979 , the Conservative Party received 43.9 percent of the vote, compared with a Labor vote of 36.9 percent and a Liberal vote of 13.8 percent. The Conservatives gained 51 seats and got 339 of 635 seats. Labor had 269 seats and the Liberals 11 seats. The turnaround in favor of the Tories was 5.1 percent, the biggest change in sentiment since 1945.

Reign

The day after the election, Thatcher was appointed Prime Minister by Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace as Callaghan's successor. When she arrived at Downing Street , she quoted the prayer of St. Francis in front of the press .

Domestic politics

Domestic Affairs in Thatcher's First Term

From the beginning, Thatcher was determined to separate her government from that of her predecessors. Out of consideration for power politics, she formed her first cabinet - like her shadow cabinet before it - not exclusively from loyal followers, but also from many one-nation conservatives and supporters of Heath. Under Thatcher, the style of internal cabinet discussions changed substantially; Away from the tried and tested Asquith model of moderating leadership, Thatcher preferred to conduct the discussions aggressively from the beginning and introduced a combative, sometimes rude tone.

In the ongoing Northern Ireland conflict , she continued the policies of the previous governments to a large extent and publicly declared that Northern Ireland was and will remain part of Great Britain as long as a majority of the population there so wishes. The IRA, on the other hand, carried out a series of bloody bombings in the summer of 1979.

In May 1980, Thatcher successfully ended the hostage-taking in the Iranian embassy in London by Iraqi terrorists by allowing Interior Minister Whitelaw to conduct a violent rescue operation by the SAS . The action, broadcast live by television cameras, brought the SAS a lot of media coverage and Thatcher for the first time a reputation for cool, determined action in a crisis situation. At the Conservative Party Congress in October 1980, Thatcher addressed doubts within the party about the economic policy it had initiated and said in one of its most famous speeches that others could turn around, and that the party was not ready to turn around.

Riots broke out in several cities in England in the spring of 1981; the so-called England Riots of 1981 showed clear racial tensions and the consequences of the decline and neglect of the "innercities" (especially inner-city districts inhabited by ethnic minorities), especially in London, Birmingham, Leeds and Bristol. Thatcher condemned the outbreaks of violence and looting and stressed in the cabinet the need to equip the police with new equipment. At the same time, she refused to provide more money for the promotion of inner-city quarters and said that more money could neither buy trust nor harmony between the races.

In the summer of 1981 Thatcher was faced with a "revolt" in the cabinet after the popularity of the government and that of Thatcher himself had reached a low point according to surveys and its Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe had submitted an anti-inflationary budget again despite the current recession . However, the loyalty of her Deputy William Whitelaw and Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington saved her from falling. As a backlash, Thatcher reshuffled her cabinet after the parliamentary summer recess: she fired Christopher Soames , Ian Gilmour and Mark Carlisle and Labor Minister Jim Prior had to move from his portfolio to the post of Minister for Northern Ireland . All were supporters of one-nation conservatism, the socio-political direction of the Tories, and were dubbed “wets” by the press - in contrast to the “dries” Nigel Lawson , Norman Tebbit and Cecil Parkinson , who shared Thatcher's economic policy ideals and now moved to cabinet posts.

From the 3rd quarter of 1981 the economy showed clear signs of recovery, but unemployment remained at a level of 3 million, an unprecedented level since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Skeptics also countered Thatcher's government that the economic recovery remained regionally limited to the south of England, while the old industrial centers in the north of England, in south Wales and Scotland remained permanently damaged. In addition, only certain sectors such as the financial sector and the service sector had benefited, while the industrial sector had no part in the economic recovery.

The victorious Falklands War against Argentina in 1982 brought Thatcher, who a year earlier had hardly been given a chance of re-election, a huge boost in popularity. The general election in 1983 was the Conservative Party's greatest success and, at the same time, that of any party since the 1945 elections . The Tories benefited not only from the radical socialist course of Labor leader Michael Foot , who advocated unilateral disarmament, the abolition of the House of Lords , substantial tax increases and further nationalizations of large banks and commercial enterprises. The newly founded Social Democratic Party , which won 15% of the vote in an alliance with the Liberal Party , split the votes of the left.

Domestic Policy in the Second Term: The Westland Affair

After her success, she promoted many of her closest followers. So avancierten Nicholas Ridley , Cecil Parkinson and Leon Brittan to cabinet members. Nigel Lawson, one of the few Thatchers who contradicted regularly internally, became Chancellor of the Exchequer and remained a key member of her cabinet until his resignation. The last prominent "wets" - Jim Prior and Francis Pym - were removed from the cabinet by 1984.

On 12 October 1984, the IRA committed during the Congress of the conservatives in Brighton a bombing of the Grand Hotel , with the aim to kill Thatcher. Five people died; Trade and Industry Minister Norman Tebbit was injured and his wife was paraplegic . Thatcher and her husband were unharmed. The next day, outwardly unimpressed, she gave the intended speech, which contributed to her tough image and earned her admiration.

The following year, Thatcher and Irish Prime Minister Garret FitzGerald signed an agreement at Hillsborough Castle that for the first time gave the Irish Government an advisory role in the Northern Ireland conflict, while also confirming that Northern Ireland's constitutional status would not be changed without the will of the Northern Irish majority.

In February 1985, the University of Oxford denied her an honorary doctorate (normally awarded to any prime minister) in protest at cuts in education.

Thatcher's authoritarian and disparaging treatment of her cabinet colleagues was also evident in the Westland affair . The dispute over the rescue of the only British helicopter manufacturer Westland Helicopters resulted in the resignation of Defense Minister Michael Heseltine , who then spoke publicly of a collapse in joint cabinet responsibility. Heseltine had promoted a cooperation with a European consortium led by the Italian Agusta , while the management (supported by Thatcher and parts of the cabinet) wanted to team up with the American Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation . Thatcher's follower Leon Brittan also had to resign from the post of Minister of Industry after it became known that he had leaked a critical official dossier intended to undermine Heseltine's position to the press. The Westland Affair inflicted severe political damage on Thatcher, who had become politically vulnerable for the first time since 1982 and who had to survive a critical debate in the House of Commons. The media also attacked Thatcher's authoritarian style of government, which was in stark contrast to the ideal of collective responsibility in previous cabinets. The piercing of information regularly practiced by her inner circle to undermine political opponents also became the subject of critical press articles. While Brittan's political career practically ended, the ambitious and flamboyant Heseltine retired to the back seats and became a challenger on hold.

In April 1986, Thatcher's government experienced its only defeat in the House of Commons when it was introduced by law to allow retailers to go on Sundays. Not only the opposition voted against the law, 72 Christian-Conservative backbenchers from their own party also overthrew the law with their vote.

In the general election of June 11, 1987 , the Conservatives again defended their comfortable majority and only lost a few seats. As a result of Thatcher's reforms, there was also increasing polarization in the general election; While the Tories were able to gain more seats in the affluent south-east of England, they suffered heavy losses in the structurally weak north of England and even lost half of their seats in Scotland. Norman Tebbit, long considered Thatcher's possible successor, left the cabinet for private reasons after the general election.

Thatcher's domestic politics in his third term

In Thatcher's third term, privatization accelerated and many larger companies were privatized in favor of a lower government quota. In an interview with Woman's Own magazine in September 1987, she coined the phrase: “There is no such thing as a society.” The phrase immediately caused widespread outrage; Thatcher repeated it, slightly modified, but in 1988 and again appealed to the individual responsibility of the people instead of blaming society and the government. As early as 1985 she had said: “Society is nobody. You are responsible for yourself. "

In January 1988 her Deputy William Whitelaw resigned on grounds of age. Their popularity curve began to decline, as it introduced in 1989 a personal perceived as unjust tax that community charge , better known as poll tax ( " poll tax "). This led to fierce criticism and sometimes violent demonstrations even in extremely conservative parts of the country. The protests were particularly strong at first in Scotland, where the poll tax had already been introduced on a trial basis in 1988. The poll tax was widely viewed as unfair as it hit poorer people far harder than rich. In his history of the Conservative Party, Robert Blake names Thatcher's approval of the poll tax as its greatest political mistake, one of the major contributors to its overthrow.

In her third term in office, Thatcher lost more and more contact with the backbenchers of her party and showed herself less and less willing to respond to their concerns. Her increasingly anti-European rhetoric also alienated her from Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson, the two remaining key members of her cabinet. Both wanted to force Britain to join the European Monetary System (EMS). Thatcher, encouraged by her economic adviser Sir Alan Walters , strictly refused to allow Great Britain to join the European Monetary System. In July 1989, she made another cabinet reshuffle and appointed John Major foreign minister instead of Geoffrey Howe, whom she instead made Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council . Walters and Treasury Secretary Nigel Lawson argued further over the course of 1989 over British accession to the EMS; Lawson eventually called on Thatcher, under threat of resignation, to fire Walters. Thatcher, increasingly relying on her own advisors, refused to fire Walters and Lawson submitted his resignation. Even Walters, whose position had become untenable, resigned a few days later. Thatcher was again forced to reshuffle her cabinet and now pushed Major into the Treasury, while Douglas Hurd became Foreign Secretary. On October 7, 1990, Great Britain joined the EMS, thus introducing a narrow exchange rate corridor (± 2.25 percent) to the other EMS member currencies for the British pound. This turned out to be a mistake almost two years later: After Black Wednesday , Great Britain was forced to leave the EMS and the British pound lost more than 25% of its value against the American dollar.

In July 1990, Thatcher loyalist Nicholas Ridley was also forced to resign from the backbenchers of the 1922 committee against Thatcher's unsuccessful opposition after giving the Spectator a controversial interview in which he saw the European Economic and Monetary Union as a scam Germany designated to gain dominion over Europe. Howe resigned on November 1, 1990 after the meeting of the European Council in Rome and Thatcher's announcement in the House of Commons that Britain would never join the European currency unit, the ECU. Thatcher was forced to reshuffle his cabinet for the sixth time in fifteen months. On November 13, during a question time in the House of Commons , the resigned Geoffrey Howe cited Thatcher's European policy course as the main reason for his resignation and called on his party colleagues to “seek their own answer to the tragic conflict of loyalty with which I have perhaps been wrestling too long. "

A few days later, Thatcher was challenged as the Tories party leader by Michael Heseltine. Many Conservative MPs feared they would lose the next general election (April 1992) with Thatcher at the helm . The poll tax in particular had made it unpopular with many voters; their popularity ratings had consistently lagged behind their own party. In addition, the tax cuts in the state budget in 1988 were criticized. Their campaign was, according to consensus, poorly conducted; Thatcher herself, as incumbent Prime Minister, also declined to promote herself, believing that her record as Prime Minister spoke for itself.

When Thatcher just missed the necessary quorum (at least 15 percent more than Heseltine) for confirmation in the party leadership in the first ballot in absentia (she took part in the CSCE summit in Paris on November 19, 1990 ) , she initially declared that she wanted to continue fighting was convinced that he would win the second ballot. One-on-one interviews with all cabinet members revealed a lack of support within the cabinet. On November 22, 1990, she announced her resignation. Thatcher's eleven years and 209 days as Prime Minister was the longest since Lord Salisbury and the longest in one go since Lord Liverpool .

Determined to prevent Heseltine as her successor, she stood up for John Major, who appeared as a compromise candidate. Major prevailed with 185 votes against Heseltine (131 votes) and Douglas Hurd (56 votes) and succeeded Thatcher as leader of the Tories and Prime Minister of Great Britain. Thatcher could not come to terms with her sudden fall; In retrospect, she bitterly viewed her fall as a betrayal of her cabinet colleagues.

Economic policy

Implementation of economic reforms

The economic policy represented by Thatcher ( Thatcherism ), underlined by the wording there is no alternative , which she repeatedly used , had a lot in common with that of Ronald Reagan ( Reaganomics ) in the USA with regard to inflation control and deregulation , but also differed in some Respect. Like Reagan, it neither increased government spending excessively nor, at least until 1987, significantly reduced taxes.

Before Thatcher took office in early 1977, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey was forced to announce tough economic policy restrictions in order to avoid the financial ruin of his country. The strikes that followed, like an internal party controversy, paralyzed the country and government for months in the Winter of Discontent and led to Thatcher's election victory.

In Thatcher's first legislative period, however, the focus was on fighting inflation ( monetarism ). In the early years, Thatcher was faced with a prolonged recession, which was characterized by a sharp rise in unemployment and high inflation . Thatcher and her Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe cut direct taxes such as income tax , increased indirect taxes, and raised interest rates to fight inflation. In his first budget, Howe cut the standard income tax rate from 33 to 30 percent and the top rate from 83 to 60 percent. Public spending has been reduced by a total of 3 percent. The education budget and housing construction were particularly hard hit by the cuts.

In its second legislative term, the government was primarily concerned with reducing the influence of the state and the trade unions on the economy. Contrary to the British tradition that the government and administration used to consult the unions before making any decisions if these had an impact on the world of work and workers, Thatcher had the unions excluded from all deliberations.

With the privatization of many state-owned companies (such as British Telecom , British Petroleum (BP), British Airways ) and local supply companies ( drinking water supply , electricity companies), the mixed economy that had existed since the end of the Second World War came to an end. The influence of the state and the state quota were significantly reduced. At the end of the Thatcher era, 40 companies with a total of 600,000 employees had been privatized. In addition, housing was privatized on a large scale; While Great Britain was the largest landowner in Western Europe in 1979, more than a million social housing units were sold (often at reduced prices to residents) in the 1980s. As a result, owner-occupation of real estate rose from 55 percent to 67 percent within 10 years, while the treasury generated net proceeds of £ 28 billion. The Thatcher government was able to reduce its national debt by 12.5% through the proceeds from the privatization of companies and housing. While the national debt of Great Britain was 54.1% of the gross domestic product in 1980 , it fell to 34.7% by 1990.

Miners' strike and deregulation

The British miners' strike in 1984/85 , which lasted a year, turned into a long-awaited trial of strength between the government and the unions . Since the radical socialist union leader Arthur Scargill had never been able to assert his strike demands within the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in previous years, he instead initiated local strikes in regions with a higher degree of organization and willingness to strike, such as Yorkshire and Scotland, where he is on many supporters could count. The miners in Nottinghamshire and South Wales, however, did not take part in the strike. Other unions, such as those of the dock and steel workers, also opposed Scargill. Scargill ensured that strike money would only be paid to miners who - unsuccessfully - took part in violent clashes against willing miners, which drew the strikers further sympathy in the country.

During the course of the strike, Thatcher's government benefited on the one hand from the accumulation of coal stocks that had been carried out long before. On the other hand, the effects of British North Sea oil production , which had further reduced the dependency on coal production , now also became apparent . The strikers soon used up their strike fund and could then no longer receive strike money . As a result, most of them returned to their work. On March 3, 1985, a NUM delegates' conference finally voted to end the labor dispute. Due to Thatcher's success and the privatization of many companies, as well as the fact that the trade unions were divided, their influence fell permanently. The way for further reforms such as the abolition of the closed shop (legally required membership in trade unions for workers in numerous companies) and the ban on so-called flying pickets ( pickets that do not belong to the company on strike ) was clear. In the following years the membership of the trade unions decreased considerably. Thatcher's partly confrontational rhetoric - as it called the miners “the enemy within” in July 1984 - caused violent contradiction within the own camp and a temporary decline in their popularity among the population.

On October 27, 1986, the Financial Services Act 1986 deregulated the London financial market , removed the distinction between market makers and stockbrokers, removed the exclusion of foreigners from membership in the Stock Exchange, and allowed companies to become members. Subsequently known as the Big Bang event , the law led to a general boom in the British financial industry, strengthened the London financial market , which had meanwhile significantly lagged behind the New York financial market, and made it once again the most important financial center in the world.

In contrast, the National Health Service (NHS), to which Thatcher emphatically stated in 1982: "The NHS is safe in our hands." Thatcher rejected any far-reaching reform of the , remained expressly excluded from far-reaching reforms that would have questioned or resolved the post-war consensus NHS turned towards privatization, saying there was no support for it. In 1987 campaign appearances, she regularly stated that her government had spent £ 15 billion in 1986 on the health sector, almost twice as much as the previous Labor government, which had only spent £ 8 billion.

In 1988, Chancellor of the Exchequer Lawson made a final rationalization of the tax structure by introducing an income tax consisting of two tax rates (25% standard rate and 40% top rate). Lawson systematically reduced direct taxes as an incentive for entrepreneurship. In contrast, indirect taxes such as value added tax were further increased. Family allowances, housing benefits and unemployment benefits have been cut. This reinforced the trend towards greater inequality in society.

Foreign policy

Thatcher's first foreign policy act was the Lancaster House Agreement , which brought the Rhodesian colonial war to an end and enabled the creation of the independent state of Zimbabwe in place of the dysfunctional Rhodesia . While she managed to revive the “ special relationship ” with the USA right at the beginning of her term of office, she found herself isolated within the European Community from the decisive Franco-German tandem Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and Helmut Schmidt . She rejected sanctions against the apartheid regime of South Africa by the Commonwealth and the European Community and advocated further economic relations with South Africa, with which Great Britain was economically closely intertwined due to its colonial past. South Africa's President Pieter Willem Botha called her a friend and invited him to Great Britain in 1984 against substantial protests, while she defamed the African National Congress as a terrorist organization because of its communist orientation .

Which took place shortly after taking office, Soviet intervention in Afghanistan condemned Thatcher sharp and declared the bankruptcy of the policy of detente . She tried, largely unsuccessfully, to persuade the British athletes to boycott the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow. On the other hand, in consideration of Great Britain's weak economic situation, it turned against economic sanctions that the USA wanted to impose under President Jimmy Carter . Thatcher strongly supported the NATO double decision and the associated stationing of medium-range missiles on British territory, which should offset the existing advantage of the Soviet SS-20 missiles .

They ridiculed the peace movement and its desire for unconditional unilateral disarmament as pure wishful thinking. In June 1980 she announced in the House of Commons: “Any policy of unilateral disarmament is a policy of unilateral surrender.” On the contrary, she expressed concern about Soviet armament and, in talks with Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and Carter, advocated arming NATO members.

Your government supported the Cambodian government of the Khmer Rouge in its endeavors to remain in the UN . In September 1982, she visited the People's Republic of China to begin negotiations with key CCP official Deng Xiaoping about how to deal with Hong Kong . She campaigned in vain for the continuation of the British administration. In 1984 she finally signed a contract with China to return the Crown Colony of Hong Kong by 1999.

Suspicious of your Foreign Ministry , Thatcher sought advice from independent experts in the academic field on foreign policy issues - especially after the Falklands War. so she consulted among others Hugh Thomas , Robert Conquest and Timothy Garton Ash and installed Charles Powell as her private secretary for foreign affairs.

"Special relationship" with US President Reagan

In addition to the similarities in economic policy, Thatcher shared a deep distrust of communism with US President Ronald Reagan. Both rejected the policy of détente and did not seek peaceful coexistence, but rather to win the Cold War. Like Reagan, Thatcher also preferred harsh rhetoric against the Soviet Union. Thatcher stuck to NATO's double decision , which stipulated that a third of all cruise missiles should be stationed on British soil. This strengthened her connection with US President Ronald Reagan , but also led to violent protests and demonstrations by the peace movement . The advantages of the close British cooperation with the USA became apparent in the renewal of the British nuclear arsenal, which had been based on the fleet-based polaris missiles since the 1960s and the Nassau agreement . With the Trident program, Thatcher strengthened the cooperation between the two countries in the arms sector . The purchase and cooperation with the US tripled the British nuclear arsenal. It was one of the Thatcher's most expensive government programs at the time of £ 12 billion (1996–1997). In addition, Great Britain allowed the USA to use the island of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean for military purposes.

On the other hand, Thatcher, in agreement with her European partners, turned against the economic sanctions with which Reagan wanted to ruin the Soviet Union economically. Although Reagan was ideologically linked, she was appalled by the 1983 US invasion of Commonwealth member Grenada . As Reagan had assured her shortly beforehand that such an invasion would not take place, Thatcher's trust in Reagan was initially disrupted.

Reagan's SDI program was also aloof from Thatcher; Seeing the advantages on the one hand, she was, on the other hand, an outspoken advocate of nuclear deterrence . In an acclaimed speech to the American Congress in February 1985, she advocated the principle of nuclear deterrence and argued that nuclear weapons had also made conventional wars less likely.

On other foreign policy issues, Thatcher followed a common line with the US, both at G7 summits, in the common demands for increased defense spending within NATO, and in the attitude towards Libyan ruler Muammar al-Gaddafi . Thatcher also made British air bases available to the US in 1986 when they bombed Tripoli and Benghazi .

In February 1984, Thatcher attended the funeral of CPSU General Secretary Yuri Andropov . While she was unimpressed by the designated successor Konstantin Chernenko , she gained a positive first impression from the Politburo member Mikhail Gorbachev and invited him to London immediately. After Gorbachev's rise to general secretary, Thatcher acted more than once as an informal negotiator between him and Reagan.

When the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait began, Thatcher immediately condemned Saddam Hussein's aggression and encouraged the new President, George HW Bush, to intervene militarily.

Relations with Chile and Augusto Pinochet

In contrast to the Labor government as well as the US government under Jimmy Carter, which sharply condemned Augusto Pinochet's military dictatorship in Chile and issued various sanctions and embargoes, including against arms exports to Chile, the Thatcher government lifted the restrictions as early as June 1979 relevant export guarantees from the State Export Credit Guarantee Department . Margaret Thatcher officially justified these steps by claiming that the problem of human rights violations in Chile has improved. The UN , Amnesty International and other organizations, however, took the opposite view. Great Britain had previously approached Chile in its conflict with Argentina over the Beagle Channel . Chile's government under Salvador Allende had accepted the British mediation role in the arbitration tribunal in the Beagle conflict , but Argentina did not (see Operation Soberanía ).

Thatcher later praised the close cooperation with Chile, which also paid off during the Falklands War. She met the former dictator Augusto Pinochet several times , especially when he was imprisoned in Great Britain from 1998 to 2000 for extradition requests from several European countries with extradition treaties on charges of genocide , state terrorism and torture . Thatcher used her considerable political influence to prevent extradition and to have her detention lifted in a political campaign in which she portrayed Pinochet as a " political prisoner " and "whose rights were being violated." This also led to considerable controversy in Great Britain itself.

Falklands War

On April 2, 1982, the Argentine junta ordered the invasion and occupation of the British-populated Falkland Islands and South Georgia . As a result, the Falklands War broke out . Secretary of State Carrington took responsibility for past mistakes at the State Department and resigned - against Thatcher's opposition - on the grounds of principle and a sense of loyalty to Thatcher's administration that someone should serve as a scapegoat for the public and the enraged House of Commons for the surprise attack by Argentina . Thatcher, who had tried unsuccessfully to persuade Carrington to stay, appointed Francis Pym in his place.

On the advice of the former prime minister Harold Macmillan, Thatcher immediately set up a small war cabinet that conferred daily and - bearing in mind the British debacle in the Suez Crisis - excluded the Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe from there. After all attempts at mediation (especially by the USA) had failed, a British task force began to recapture the occupied territories in mid-April. The victory in the Falklands War gave Thatcher a huge boost in popularity. As a result, she called for 9 June 1983 general election , and increased its growth in popularity in an election victory translate, and they also benefited from the split in the Labor Party.

European integration and Germany policy

Under the motto "I want my money back", Thatcher achieved the British discount on British contributions to the then EC in 1984, which is still valid today . This led the Federal Chancellor Helmut Kohl to the sentence that he feared Margaret Thatcher “like the devil the holy water”.

Thatcher thought close cooperation between European states was important, but she always warned of a European superstate. She saw European unity above all as important under the conditions of the Cold War. She had a particularly difficult relationship with EC Commission President Jacques Delors . While the majority of the European partners under the leadership of Delors tried to advance the integration of the EC, Thatcher always saw the EC as just an economic community. In implementing the Delors package, which provided for a reform of agricultural policy, the creation of a financial system and the expansion of the structural funds for poorer member states, both of them worked closely together. Delors and Thatcher also advocated greater fiscal discipline and the containment of agricultural surpluses.

The first major argument between the Prime Minister and the Commission President was sparked when Delors said on a visit to the UK that 80% of economic and social decisions in the EC would be regulated at European level within ten years. Then on September 20, 1988 Thatcher gave a high-profile speech at the European College in Bruges. In it she set out her demand for a community based on business and trade relations and emphasized that she had no interest in a stronger political integration of Europe - Thatcher called this project “remodeling of Europe”. Thatcher stated that her government had not scaled back the role of the state in Great Britain in exchange for accepting a European superstate that would dominate its member states from Brussels.

Thatcher also strictly rejected the Delors report on European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU); she wanted to hold on to the British pound at all costs.

Thatcher had an ambivalent relationship with Germany. At the end of the 1970s and at the beginning of their tenure, Thatcher and the Conservatives repeatedly viewed the FRG as an economic model with high productivity, from which the British economy could learn a lot. However, this belief waned from the mid-1980s with the success of the British economy, which from 1982 recorded higher growth rates than the FRG and France. In particular, the success of the City of London, which was more likely to compete with the global financial markets of Tokyo and New York, left the two continental financial centers Paris and Frankfurt far behind and degraded them in comparison to provincial financial centers. While she initially had an extremely positive impression of the CDU politician Helmut Kohl and viewed the CDU as the German counterpart of the British Conservatives, in later years she was rather hostile towards him. She strictly rejected Kohl's enthusiasm for both European and German unification. In the process of German reunification in 1989/90, she initially reacted with fears and disapproval. Thatcher saw the danger of a Germany that would profit from the collapse of the Eastern bloc and dominate Europe as a hegemon. She stressed to President Bush that Germany's fate was not just a question of self-determination, but had far greater implications. The fate of Gorbachev, the Warsaw Pact and Eastern Europe is closely linked to the German question. Together with François Mitterrand , she looked for ways to stop developments. In March 1990 she had a conference with Germany experts held at the Checkers estate. The publication of a memorandum about this conference, which revealed their views , which were also influenced by German National Socialism , about bad characteristics in the national character of Germans, triggered the Checkers affair in the summer of 1990 . It finally insisted, after Fritz Stern's advice , on recognition of the post-war borders by Germany, which was finally laid down in the two-plus-four treaty . She told Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker that her image of Germany had essentially developed by 1942 and has changed little since then.

Environmental policy

In her reign, Thatcher dealt with issues of environmental protection and global warming early on . While on the one hand she mocked organizations like Greenpeace as naive and backward looking in interviews, on the other hand she campaigned for environmental protection and brought the issue to the attention of a broader British public. In June 1984, she used her chairmanship of the G7 summit in London to secure a commitment to more research to address pollution, and in particular the problem of acid rain .

Due to her longstanding support for the British Antarctic Survey , she quickly became aware of the discovery of the ozone hole there in 1985 . As a scientist, she recognized the importance of the discovery of the greenhouse effect and used her political weight to warn of and combat the resulting dangers. In a speech to the Royal Society in September 1988, for example, she warned of the dangers of the ozone hole, a topic that she subsequently took up in a speech to the General Assembly of the United Nations . In these speeches, she warned urgently about greenhouse gases: “We are creating a global heat trap that could lead to climatic instability.” She also emphasized the urgent need for further research and rapid measures to reduce emissions. So she worked to reduce carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, but faced opposition from the US on this issue. She has repeatedly advocated an international agreement with the Bush administration to discuss environmental issues on a global level.

She saw coal and other fossil fuels as "dirty" energy sources and instead advocated nuclear energy as a clean alternative. On the other hand, she dismissed the risks and problems of nuclear energy (such as radioactive waste) and declared: “The problems that science has created can be solved by science.” She was confident that within the next 50 years a solution for the problem of nuclear waste storage could be found. She paid little attention to the development of renewable energies .

For the problem of the continuously growing amount of garbage, she identified an individual responsibility and told the London Times in an interview that every individual has a responsibility for the environment. In addition, she saw a fault in modern packaging technology, which generates too much waste.

Honors

Margaret Thatcher was appointed to the Queen's Privy Council in 1970 . Member of the Royal Society (FRS) since 1983 , she was accepted into the Order of Merit in June 1990 . In 1995 she received the highest order in England, the Order of the Garter . She was also an honorary and only female full member of the renowned Carlton Club . Since February 2007, the foyer of the British Parliament, the Palace of Westminster , has housed a larger than life bronze statue of Thatcher created by the sculptor Antony Dufort.

In the Falkland Islands January 10th is celebrated as Thatcher Day. Since 1991 she has also been the namesake of the Thatcher Peninsula on the north coast of South Georgia in the South Atlantic.

The American Philosophical Society awarded her the Benjamin Franklin Medal for Distinguished Public Service in 1987 . 1991 gave US President George HW Bush Thatcher, the Medal of Freedom ( "The Presidential Medal of Freedom"), the highest civilian honor in the United States. The city of Gdansk granted Thatcher honorary citizenship in 2000.

After retirement and end of life

Shortly after her resignation, Margaret and her husband Denis Thatcher bought a townhouse in Chester Square in Belgravia, London . Always a restless workaholic with little interests outside of politics, Thatcher quickly found himself increasingly disaffected with her successor, John Major.

In two speeches in the United States in June 1991, she warned that attempts to establish a unified EC foreign policy would undermine and weaken NATO. They condemned the EC's protectionist trade policy and instead again campaigned for a free trade area that would encompass North American NAFTA , the EC and Eastern Europe. In the fall of 1991, she gave a speech on the collapse of Yugoslavia , in which she opposed the passivity of the West, which is watching while the Yugoslav army destroys Croatia and kills Croatian civilians. In the media she has now repeatedly criticized, sometimes categorically, sometimes openly, the work of her successor as too pro-European. She also rejected the Maastricht Treaty , signed in 1992 . For Major, Thatcher's repeated criticism proved a heavy burden; his government was severely affected by the constant disputes over the European question.

In the general election of 1992 , she supported her successor's government with several campaign appearances; she herself decided not to run for re-election for the lower house. She was then, as is usual for retired prime ministers, the same year ennobled . As a life peer (" Peer for life") she moved on June 30th as Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven in the County of Lincolnshire in the House of Lords (" House of Lords "). Denis Thatcher had been bestowed the hereditary title of Baronet of Scotney in the County of Kent the year before (which his wife already used the courtesy "Lady").

Thatcher wrote her memoirs from 1992 and published them in two volumes in 1993 and 1995; She also traveled around the world for various British companies as an unofficial ambassador and lobbyist. After the electoral defeat of the Tories in 1997, she supported William Hague in his candidacy for the chairmanship of the party.

In 2000 and 2001 Lady Thatcher suffered several strokes , which also led to permanent memory disorders. In March 2002, she then announced her resignation from public life. In 2003 her last book was published, Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World , in which she commented on current issues in world politics. Once again she had authored the book, as well as her memoirs, with the help of her speechwriter Robin Harris. In June 2003, Denis Thatcher succumbed to cancer.

After Ronald Reagan's death , she traveled to the USA again in 2004 to attend the memorial service in Washington on June 11. She was one of four people Reagan personally asked to speak at his funeral. Because of her poor health, the eulogy had been recorded well in advance and was played on screens at the funeral service.

In mid-2008 it became known that Lady Thatcher suffered from advanced dementia . Her daughter Carol Thatcher discussed her mother's disease in a book in 2008. In the British press in 2008 the question of whether Lady Thatcher should receive a state funeral after her death was controversial. On July 19, 2010, she attended a meeting of the House of Lords for the last time. In December 2012 she moved to a suite at the Ritz Hotel in London. There she died on April 8, 2013 from complications from another stroke.

Reactions to Thatcher's death

Immediately after Thatcher's death, the old conflicts from her tenure broke out again. Numerous obituaries and reflections appeared on her reign.

Both then-incumbent Prime Minister David Cameron and his surviving predecessors paid tribute to Margaret Thatcher. In general, Thatcher's political opponents also expressed respectfulness about her and her work. Labor leader Ed Miliband condemned all cheers over Thatcher's death and praised her as "a huge figure in British politics and on the world stage". Former Liberal Democrat party leader Paddy Ashdown called Thatcher "undoubtedly the greatest prime minister of our time."

Barack Obama , then President of the USA, described the deceased as "one of the great advocates of freedom and true friend of America".

In Brixton , Glasgow , Leeds , Cardiff and the old mining towns, on the other hand, around 200 - mostly young - people celebrated and danced in the streets on the occasion of Thatcher's death, leading to clashes with the police and several arrests. After a campaign on social networks, the song Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead is available en masse for ringtones and iTunes . The rapid spread is attributed to a social media campaign that has been prepared for some time. A short time later, Thatcher's supporters succeeded in positioning I'm in Love with Margaret Thatcher by the punk band The Notsensibles , which was written in 1979, in the British single charts via social media .

Funeral service

The funeral service held on April 17, 2013 was not a state funeral in the strictest of protocols, but still cost the British state £ 3.2 million. After a funeral procession through London, where u. a. 700 soldiers from regiments active in the Falklands War escorted, a service took place in St Paul's Cathedral with more than 2000 guests. 11 prime ministers and 17 foreign ministers had come. Former Foreign Ministers Henry Kissinger , George Shultz and James Baker were represented from the USA , as was former US Vice President Dick Cheney . Germany was represented by Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle . Thatcher's body was then cremated in the immediate family at Mortlake Crematorium in Kew . The urn was buried next to that of her husband Denis on the grounds of the Royal Hospital Chelsea in London. During the funeral, the Queen was present and the quarter-hour theme of Big Ben was switched off, a special honor bestowed upon British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who died in 1965 .

Political legacy

Thatcherism

The term Thatcherism was first used in 1979 by the communist magazine Marxism Today and initially used as a fighting term for the political left. Thatcher and her followers quickly adapted the term for their own use of the language. Thatcher founded the British think tank Center for Policy Studies in 1974 with Sir Keith Joseph and Alfred Sherman . This had an essential role in spreading positions of monetarism and a withdrawal of state activities in favor of the free market . The center itself considers Thatcher's advocacy of monetarism in the sense of Milton Friedman to be more important than the acceptance of the theses of Friedrich August von Hayek in the sense of the Austrian school . Although Hayek's intellectual rejection of socialism certainly influenced Thatcher, Keith Joseph and other political companions, Hayek's economic and macroeconomic approach played a much smaller role in Thatcherism than Friedman's monetarism. In a friendly correspondence with Thatcher, Hayek called for a much faster restriction of the unions and rather complained than welcomed the influence of the monetarists. Thatcher had rejected this like Hayek's references to the miracle of Chile insofar as this could not be enforced under the conditions of a democracy.

Thatcherism combines both conservative and liberal elements. In addition, traditional values are emphasized in Thatcherism or Victorian values in the British context , which stand in contrast to permissive society. More than other British politicians (with the exception of Tony Blair), Thatcher also publicly showed her Christian faith and emphasized what she saw as the central role of Christianity in national life. Thatcherism serves - in the words of Nigel Lawson - as a political platform for a strong emphasis on the free market, limited government spending and tax cuts, coupled with British nationalism. Nigel Lawson's definition: "Free markets, financial discipline, tight control over public spending, tax cuts, nationalism," Victorian values "(in the sense of a Samuel Smiles help yourself variant), privatization and a dash of populism."

Richard Vinen also differentiates between Thatcherism, on the one hand, between Thatcher's personal role and the reforms initiated by her government. On the other hand, he also draws a dividing line between supporters who, like Howe and Lawson, were more committed to the core ideas of Thatcherism than to Thatcher himself, and those who, on the other hand, defined themselves as Thatcherists in the sense of an unconditional loyalty to the politician Margaret Thatcher. Dominik Geppert judges Thatcher: "It was their will to lead, their populism, their missionary zeal to convince others of the correctness of their own attitudes that gave Thatcherism its political clout." a conflict-ridden relationship between conservative and liberal elements. As early as 1990, the historian Maurice Cowling critically questioned whether Thatcherism was really a new element in politics. In his view, Thatcher only used radical variations on the themes of freedom, authority, inequality, individualism and decency and respectability, which had been the theme of the Conservative Party since at least 1886. "

Thatcherism replaced the British post-war consensus and shifted the political middle ground to the right. The economic policy reforms of Thatcherism were also maintained from 1997 by New Labor under the new Prime Minister Tony Blair, who acknowledged Thatcher's legacy; In 2002, New Labor leader Peter Mandelson even declared, "We are all Thatcherists now." Occasionally, this continuation of Thatcher's economic policy by Blair's Labor government is described under the catchphrase "Blatcherism".

polarization

Thatcher's politics like her person polarize even after her active days. In two polls in 2002 and 2003, she was ranked 16th among the 100 greatest Britons of all time and 3rd among the 100 worst. In a September 2008 poll by BBC Newsnight program aimed at voting for the best prime minister after 1945, Thatcher came third behind Churchill and Clement Attlee . In a similar poll by the University of Leeds in 2010, Thatcher came second; this survey was of 106 academics specializing in British history and politics .

Richard Vinen sees Thatcher, who failed to win a majority in the other parts of the country in all general election, as a purely English phenomenon. Eric Evans attests that years after Thatcher's fall, it remains controversial in British society.

Her supporters highlight her economic and social policy, which has led to more prosperity for the country and many citizens. Their role in ending the Cold War is also emphasized by their supporters. In addition, they have re-established Great Britain, formerly known as the “sick man of Europe”, as a leading great power. Critics accuse her of the destruction of a social sense of community through the smashing of the trade unions, the ruin of the public sector through privatization and ignorance of intangible social values. In addition, the poverty rate has almost doubled. Quality problems arose with the English drinking water suppliers privatized under Thatcher . The water prices rose in ten years by 46 percent, the operating companies nevertheless not invested sufficiently in the pipe network. On the other hand, society benefited from privatizations. Large companies like British Steel and British Airways worked far more efficiently after privatization than before; This positive effect was subsequently also recorded in companies that remained in government hands. Many private households benefited from the increased willingness to provide services; New customers who had previously had to wait many weeks for a telephone connection could get it from BT in a few days. Thatcher's era also saw the adoption of the controversial Clause 28 , which banned local authorities from willfully promoting homosexuality.

Thatcher's authoritarian style of government is also cited as a point of criticism; Joint cabinet responsibility suffered during her reign; instead of joint cabinet decisions, she negotiated political issues mostly with ministers in one-to-one discussions. Supporters counter that this was completely legal within the constitutional framework and thus the problem of increasing congestion, which plagued the Heath, Wilson and Callaghan governments more and more, has been resolved. It is also criticized that Thatcher trusted a small circle of personal advisers (such as Bernard Ingham and Charles Powell) rather than the cabinet. In addition, she has reinterpreted the office of prime minister, formerly often only a primus inter pares in the cabinet, to a presidential office - an accusation that was later regularly brought against Tony Blair.

Thatcherism was never able to prevail in Scotland and its measures met with resolute resistance from the population, which increasingly turned away from the conservatives in the general election. The former Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond attributed the Scots' independence struggle indirectly to Thatcher and Polltax , which is downright hated, especially in Scotland . Polarization also took place in Wales through Thatcher's government; According to a study in 1979, only 57% defined themselves as Welsh rather than British, compared to 69% of those surveyed in 1981.

Economic Legacy

The importance of Thatcher's economic policy is still controversial today. With the contractionary monetary policy of the early 1980s, it succeeded in lowering inflation, but at the cost of a sharp rise in unemployment to a peak of three million (around 12.5 percent in 1983). Thatcher's monetarist policy is viewed as a failure by many economists, including Milton Friedman . The entire reign was marked by social unrest and high unemployment. The increase in productivity in the UK from an average of 1.1% in the 1970s to an average of 2.2% in the 1980s is attributed by some economists to their policies of privatization, deregulation and the reduction of trade union influence. Others attribute the increase in productivity to the decline of the (by international comparison rather low-productive British) industrial sector and the growth of the service sector. On the positive side, it was noted that the dynamism of the British economy has not lagged behind the dynamism of the German and French economies since the 1980s. Economic growth in the 1980s was slightly higher at an average of 2.7% than in the 1970s (2.5%).

The deregulation of the British banking system in the wake of the so-called Big Bang is seen as a contributory factor to both the later success of London as a financial center and the casino capitalism that led to the financial crisis from 2007 onwards .

Cultural aftermath and representation in drama, film and media

Beginning with her elimination of free milk in elementary schools in 1971, Thatcher became the subject of countless jokes and satirical accounts. The satirical radio play The Iron Lady was released in 1979. From the mid-1980s, Thatcher became one of the most famous people in the world, who was far more popular abroad than in Great Britain itself. Known as “Maggie” by opponents and supporters alike, Thatcher was also influenced by the influential British art critic Michael Billington as a formative for theater and music the arts classified.

In the 1980s it became the subject of numerous protest songs . Billy Bragg and Paul Weller formed the Red Wedge collective especially for this purpose . In the album The Final Cut of Pink Floyd Margaret Thatcher is mentioned several times. She is criticized, among other things, in connection with the Falklands War.

John Wells satirically targeting Thatcher in various media formats. With Richard Ingrams , the alleged Dear Bill letters were published in exchange with Denis Thatcher as a column in the Private Eye and as a play in the West End as Anyone for Denis? listed. Anyone for Denis? came on television in 1982. In Spitting Image , a satirical British television series, Thatcher was also a popular enemy; Steve Nallon gave her his voice.

Margaret Thatcher has also been featured in various television programs, documentaries, films and plays. In the James Bond film Deadly Mission , she was portrayed by the impersonator Janet Brown . Patricia Hodge played her in Ian Curteiss' The Falklands Play (2002) and Andrea Riseborough in The Long Walk to Finchley (2008). The 1991 television film Thatcher: The Final Days showed the final days as Prime Minister and was written by Richard Maher , in which Sylvia Syms played Thatcher. She is also the title character in the 2009 film Margaret , played by Lindsay Duncan . She played Meryl Streep in 2011 in Die Eiserne Lady (Original title: The Iron Lady ).

Thatcher has a side appearance in Alan Hollinghurst's book The Beauty Line , which won the Man Booker Prize in 2004.

Private archive

In June 2015, Margaret Thatcher's heirs gave their personal records and papers to an agency of the Ministry of Culture and Media. For this they were granted a discount of one million British pounds on the expected inheritance tax of 4.7 million British pounds. They turned down the opportunity to sell them in the United States . At Thatcher's request, the papers will be kept in the public archives of Churchill College at the University of Cambridge and should also be accessible online.

Thatcher's results in her constituency

| choice | Constituency | Political party | be right | % | result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margaret Roberts | ||||||

| British general election 1950 | Dartford | Conservative party | 24,490 | 36.2 | Failed | |

| British general election 1951 | Dartford | Conservative party | 27,760 | 40.9 | Failed | |

| Margaret Thatcher | ||||||

| British General Election 1959 | Finchley | Conservative party | 29,697 | 53.2 | Elected | |

| British General Election 1964 | Finchley | Conservative party | 24,591 | 46.6 | Elected | |

| British General Election 1966 | Finchley | Conservative party | 23,968 | 46.5 | Elected | |

| British general election 1970 | Finchley | Conservative party | 25,480 | 53.8 | Elected | |

| British General Election February 1974 | Finchley | Conservative party | 18,180 | 44.0 | Elected | |

| British General Election October 1974 | Finchley | Conservative party | 16,498 | 44.0 | Elected | |

| British General Election 1979 | Finchley | Conservative party | 20,918 | 52.5 | Elected | |

| British general election 1983 | Finchley | Conservative party | 19,616 | 51.1 | Elected | |

| British general election 1987 | Finchley | Conservative party | 21,603 | 53.9 | Elected | |

Titularia

- Miss Margaret Roberts (1925-1951)

- Mrs. Margaret Thatcher (1951-1959)

- Mrs. Margaret Thatcher, MP (1959-1970)

- The Rt Hon. Margaret Thatcher, MP (1970-1983)

- The Rt Hon. Margaret Thatcher, MP, FRS (1983–1990)

- The Rt Hon. Lady Thatcher, OM , MP, FRS (1990-1992)

- The Rt Hon. The Baroness Thatcher, OM, PC , FRS (1992–1995)

- The Rt Hon. The Baroness Thatcher, LG , OM, PC, FRS (1995-2013)

Own books

- Downing Street No. 10. Econ, Düsseldorf et al. 1993, ISBN 3-430-19066-5 .

- The memories 1925–1979. Econ, Düsseldorf et al. 1995, ISBN 3-430-19067-3 .

- The Collected Speeches of Margaret Thatcher. Robin Harris (Ed.), HarperCollins, London 1997, ISBN 0-00-255703-7 .

- Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World . Harper Perennial, London 2003, ISBN 0-06-095912-6 .

literature

- Richard Aldous: Reagan and Thatcher. The Difficult Relationship. Arrow, London 2009, ISBN 978-0-09-192608-3 .

- Gerhard Altmann: Farewell to the Empire. The internal decolonization of Great Britain 1945–1985 . Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-870-1 .

- Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, ISBN 1-904950-71-X .

- John Campbell: Margaret Thatcher: Grocer's Daughter to Iron Lady. Vintage Books, 2009, ISBN 978-0-09-954003-8 (first published in 2003).

- David Cannadine : Margaret Thatcher: A Life and Legacy. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017, ISBN 978-0-19-879500-1 .

- Erik J. Evans: Thatcher and Thatcherism. Routledge, Milton Park 1997, ISBN 0-415-66018-1 .

- Dominik Geppert : Thatcher's Conservative Revolution. The change of direction of the British Tories 1975–1979 (= publications of the German Historical Institute London. Volume 53). Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-56661-X (also: Berlin, Free University, dissertation, 2000).

- Bernd K. Ital: The policy of privatization in Great Britain under the Margaret Thatcher government. Shaker Verlag, Aachen 1996, ISBN 3-8265-5339-X .

- Detlev Mares: Margaret Thatcher. The dramatization of the political. Muster-Schmidt Verlag, Gleichen et al. 2014, 2nd updated edition 2018, ISBN 978-3-7881-0171-8 .

- Charles Moore: Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume One: Not For Turning. Allen Lane, London 2013, ISBN 978-0-7139-9282-3 .

- Charles Moore: Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume Two: Everything She Wants. Allen Lane, London 2016, ISBN 978-0-14-027962-7 .

- Charles Moore: Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume Three: Herself Alone. Allen Lane, London 2019. ISBN 978-0-24-132474-5 .

- Ian Gilmour : Dancing with Dogma: Thatcherite Britain in the Eighties. Simon & Schuster, 1992, ISBN 0-671-71176-8 .

- Simon Jenkins : Thatcher and Sons: A Revolution in Three Acts . Penguin Books, London 2006, ISBN 0-14-100624-2 .

- Hans-Christoph Schröder : English history. 7th, updated edition. Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-41055-0 .

- Richard Vinen : Thatcher's Britain. The Politics and Social Upheaval of the 1980s . Simon & Schuster, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-84739-209-1 .

- Hugo Young: One of Us: A Biography of Margaret Thatcher. Macmillan, London 1989, ISBN 0-333-34439-1 .

Web links

- Margaret Thatcher at Hansard (English)

- Literature by and about Margaret Thatcher in the catalog of the German National Library

- Meike Fechner: Margaret Thatcher. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Margaret Thatcher Foundation Archive with numerous documents by and about Margaret Thatcher

- The making of Maggie (English) , Germaine Greer , The Guardian 11 April, 2009

- Official biography of Margaret Thatcher (English)

- Extract from German Unification 1989–1990 - PDF, 5 p., 2.12 MB; see. Thatcher's fight against German unity , BBC, September 11, 2009

- Maggie Thatcher and the Reunification , someday / Spiegel Online, September 11, 2009

- Dossier on Margaret Thatcher from Spiegel Online

- Brigitte Baetz : Margaret Thatcher was authoritarian and assertive - on the death of the former British Prime Minister. In: Deutschlandradio . April 8, 2013.

- Wencke Meteling: "Instead of Phoenix, only ashes". Thatcher's economic policy in international and British criticism . In: Heuss-Forum 2/2016.

- One hour of history: Margaret Thatcher becomes British Prime Minister in 1979 In: Deutschlandfunk Nova . May 24, 2019.

Remarks

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Erik J. Evans: Thatcher and Thatcherism. Routledge, Milton Park 1997, p. 5.

- ↑ David Cannadine : Margaret Thatcher: A Life and Legacy . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017, p. 3.

- ↑ Thatcher, Baroness. In: World who's who: Europa biographical reference. Routledge, London 2003 (2002) ff. (Online resource; accessed February 29, 2012)

- ↑ John Campbell: Margaret Thatcher. Volume One: The Grocer's Daughter . Random House, London 2000, p. 18 ff.

- ^ Charles Moore: Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume One: Not For Turning. Allen Lane, London 2013, p. 8 f.

- ^ Charles Moore: Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume One: Not For Turning. Allen Lane, London 2013, p. 3.

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ Dominik Geppert: Thatcher's Conservative Revolution: The Change of Direction of the British Tories (1975-1979) . Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, p. 122.

-

↑ Dominik Geppert: Thatcher's Conservative Revolution: The Change of Direction of the British Tories (1975-1979) . Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, pp. 103 ff.

John Campbell: Margaret Thatcher. Volume Two: The Iron Lady . Vintage Books, London 2008, p. 388. - ↑ Peter Childs: Texts. Contemporary Cultural Text and Critical Approaches Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2006.

- ^ Robert Philpot: How Margaret Thatcher's family sheltered an Austrian Jew during the Holocaust , in: The Times of Israel, June 29, 2017.

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Richard Vinen: Thatcher's Britain. The Politics and Social Upheaval of the 1980s . Simon & Schuster, London 2009, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Simon Jenkins: Thatcher and Sons: A Revolution in Three Acts . Penguin Books, London 2006, p. 19.

- ↑ Simon Jenkins: Thatcher and Sons: A Revolution in Three Acts . Penguin Books, London 2006, p. 18.

-

↑ John Campbell: Margaret Thatcher. Volume One: The Grocer's Daughter . Random House, London 2000, p. 65.

Colin Letcher How Thatcher The Chemist Helped Make Thatcher The Politician , Popular Science 2012. - ^ Charles Moore: Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume One: Not For Turning. Allen Lane, London 2013, p. 66.

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 22.

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Richard Vinen: Thatcher's Britain. The Politics and Social Upheaval of the 1980s . Simon & Schuster, London 2009, p. 22.

- ↑ Richard Aldous: Reagan and Thatcher. The Difficult Relationship . Arrow, London 2009, p. 20.

- ↑ Simon Jenkins: Thatcher and Sons: A Revolution in Three Acts . Penguin Books, London 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 25.

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 26.

- ↑ John Campbell: Margaret Thatcher. Volume One: The Grocer's Daughter . Random House, London 2000, p. 100.

- ^ Richard Vinen: Thatcher's Britain. The Politics and Social Upheaval of the 1980s . Simon & Schuster, London 2009, p. 24.

- ↑ Clare Beckett: Thatcher (British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century) . House Publishing, London 2006, p. 30.