Stratiot

Stratiot or Stradiot ( Greek στρατιώτες stratiotes , Albanian Stratiotët , Italian stradioto, stradiotto [ plural : stradioti, stradiotti ]) is the Greek name for soldier . Stratioten were mercenary units from the Balkans , which were mainly recruited by the states of Europe from the 15th to the middle of the 18th century .

Surname

The Greek term στρατιώτης / -αι stratiotes / -ai has been used since antiquity (800 BC to approx. 600 AD) with the meaning of the "citizen who is obliged to fight and does military service, the warrior" and later " Who does military service for pay " is used. The same word was then used in the Roman (8th century BC to 7th century AD) and Byzantine Empires (395–1453). In later Byzantine times, stratiot was understood to be a cavalryman , to whom the emperor granted a military fief as a reward for military service ( pronoia ).

The noble Dalmatian Coriolano Cippico described in his work De Bello Asiatico that the Republic of Venice employed many Albanians with their horses in all the cities of the Morea that were under their rule , which were called stratiotes in Greek.

A late 19th century Greek writer, Konstantin Sathas, attributed the origin of the name Stratiot to the Italian word Strada ("street"), assuming that the Stratiotes were organized into mercenary companies that trod the street in search of one Engagement and employment. However, this thesis seems improper. The Italian term "Stradioti" (plural) is more a borrowing of the Greek word στρατιῶται (stratiótai), d. H. Soldiers.

Origin and descent

The ethnic identity of the stratiotes is uncertain. The Italian historian Paolo Giovio called them Spartians , Achaeans or simply Greeks, the Italian poet Torquato Tasso born in Greece wanderers, the Italian humanist scholar Pietro Bembo Greeks and Epirotians , the Italian author Luigi da Porto Levantine Albanians with Greek names, the Italian historian and Politician Francesco Guicciardini Albanians and those coming from the surrounding provinces of Greece, the Venetian chronicler and Senator Marino Sanudo reported that the Stratiots were people who were called in Latin Epirots, Greeks Albanians or Turks .

According to a study by the Greek author Kostas Mpires of the names of the Stratiotes, it appears that around 80% to 90% were of Albanian origin, while the rest were of Slavic (Croatian) and Greek origin. The latter mainly concerned the captains of the Stratiotes. Among them there are names like Alexopoulos, Clada, Comnenos, Klirakopoulos, Kondomitis, Laskaris , Maniatis, Palaiologos (Paleologo), Psaris, Psendakis, Rhalles (Ralli), Spandounios, Spyliotis, Zacharopoulos etc. Others like Soimiris, Vlastimiris and Voicha seem to have been of South Slavic origin.

Modern writers have come to the conclusion today that the Stratiotes are primarily about Greeks and Albanians from Morea , where they or their ancestors had previously moved from more northern areas and took refuge in the Byzantine despotate of Mistra and the Venetian possessions in western and found southern Greece from Nafpaktus , Argos , Koroni , Methoni , Nauplion and Monemvasia.

The stratiotes who came to Italy in the late 15th and early 16th centuries had already been born on Morea and the ancestors of these stratiotes had immigrated there from Epirus in the late 14th and early 15th centuries and lived there in clan communities. Given the poor and poor conditions on earth, they worked as shepherds and horse breeders. In the 15th century, this ethnicity comprised about a third of the population of Morea. Since 1402 there have been references in Venetian-Levantine documents from Albanians on the island of Evia . In a document from 1414, the name Stratiot appears for the first time, meaning members of the Albanian communities living on the island who were equipped with a horse to defend the island in the event of an attack. (See: The Albanian Settlement of Greece )

It must also be noted that the Stratiotes coming from Venetian Greece were Hellenized or even Italianized after two generations . Since many served under Greek commanders and with Greek stradiotes, this process continued. Another factor in this assimilation process was the active participation of the Stradiotes and their families in the Greek Orthodox or Greek Byzantine parishes in Naples, Venice and elsewhere. In Venice, the Greeks turned to the Greek Orthodox church community, which first met in the Chiesa San Biagio and from 1561 in the Chiesa San Giorgio dei Greci, and the Albanians to the Catholic Greek-Byzantine church community, which was located in the Chiesa San Maurizio gathered. In Naples , the Greek-Albanian population came together in the Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo dei Greci .

![]()

The French historian Philippe de Commynes again reported that the Stratiotes were all Greek from the beginning and came from those places that belonged to the Venetians; one from Nafplio on Morea, the other from Albania near Durrës and that the Signoria of Venice had great confidence in them and used them very much. Venice did not make much of a problem in terms of ethnic differences or regions of origin. They simply qualified them as stratots. What was remarkable, however, was the rivalry and intolerance between the Greeks and the Albanians, which often led to disobedience, especially with regard to commanders belonging to rival nationalities, which was a constant concern of Venice.

When the Republic of Venice lost the last of the aforementioned Greek possessions, Koroni, to the Ottomans in 1534 , Stradiotes were hired from the Dalmatian possessions.

history

For the first time the name Stratiot appears in connection with the profound reform of the Byzantine military system in the 7th century when the defense of the eastern and African provinces ( Egypt , Syria and Africa ) collapsed under the onslaught of the Saracens within a short time and it turned out that the late Roman army organization , which relied mainly on mercenaries, was not up to the demands.

When the Crusaders invaded the areas of the Byzantine Empire during the Fourth Crusade (1204) and Constantinople was sacked and conquered by Franco-Flemish Crusaders and Venetians, the term Stratiot also became known among the Western peoples. However, its importance changed significantly in the 12th and 13th centuries. Stratiotes were now called local mercenaries who belonged to various peoples residing in Romania . So there were Greek , Albanian , Wallachian and Slavic stratiots in the Balkans . Muslim soldiers of Ottoman origin who had settled in Asia Minor were also known as stratiotes. These mercenaries of different origins mostly served as light riders in the principalities and lordships of the Aegean region , later also in European countries. As “displaced people” who had lost their homes and families in the fight against the Ottomans, they preferred to wage wars of revenge against the Ottomans, but fought for everyone who paid them. Their bravery was proverbial and their cruelty notorious.

The consolidation of feudalism in the High Middle Ages (beginning / middle of the 11th century to around 1250) and the conflicts of interest between the feudal lords had turned Western Europe into a field of local battles. The organization of the troops was based mainly on the training of the military aristocracy and on the bond between the lords and their vassal soldiers. The rise of the regional states and the gradual concentration of power in the hands of the great dynastic monarchies fundamentally changed the process of war.

Niccolò Machiavelli pointed out in his book Il principe (The Prince) that “a prince must have no other objective, thought or occupation than war […] and it is clear to see that when princes have more delicacies thought than of the weapons, they lost their status [...]. "

Regardless of Machiavelli's theory, the above-mentioned increasing needs of states were met by conversion to military technology and with the use of new weapons of mass destruction (cannons, mobile artillery and later rifles and pistols). Added to this was the recruitment of mercenaries, experts in the art of war, using new military tactics and the gradual formation of permanent armies.

A flourishing war market developed in Italy. Until the middle of the 14th century Italy was a generous mercenary importer, who mainly came from Germany but also from other European countries, such as B. the soldiers of the Swiss Confederation ( Reisläufer ) recruited. In 1360 the English condottiere John Hawkwood was in the service of the city of Pisa against Florence in the Hundred Years War .

The emergence of organized modern states, which had new instruments and whose ambitions were not only limited to enforcing their sovereignty over their territories, but also tried to expand their dominance over all of Europe, made it from the late Middle Ages (approx. 1250 to approx. 1500) necessary to form better trained and organized armies. In the second half of the 14th century, the Condottieri (plural of Condottiere), the so-called "Capitani di ventura" (commanders of a private mercenary company), who quickly became the undisputed protagonists of the war on the Italian peninsula, asserted themselves in Italy.

Those who could afford it recruited the expensive Western European mercenaries, such as Italians, Germans, Swiss, etc. With the Swiss, because of a solidarity code within the Swiss Confederation, it was not always easy to hire them, as they never took up arms when a contingent of Compatriots already was in the ranks of the enemy. Otherwise they contented themselves with “surrogates”, such as the stratiotes, who, because of their special war tactics (as described below), have proven to be just as capable over the decades.

These stratiots were considered "mostly" faithful to the Lord who paid them. In his work La spedizione di Carlo VIII in Italia, Marino Sanudo underscored her loyalty to the Republic of Venice: "[...] Bernardo Contarini mounted his horse armed with all stratiotes [...] and made everyone swear to die in honor of the Signoria [...] ] and screaming: Markus! Markus! [meaning the Republic of Venice] Saint George! Saint George! [meaning the patron saint of the Stratiotes] they rode away. [...] "

Other factors that set the Stratiots apart from other mercenaries were their fitness as refugees; in fact, they were accompanied by their families and their clergy to the locations and resettled at or near their place of work.

If they were "well behaved" they were granted privileges, honors and land. Hereditary titles (mostly knights ) and lifelong provisions (pensions) were conferred on those who distinguished themselves. This is evidenced both by the titles that their leaders amassed and by poems in Greek and Italian that treated their exploits. Mention should be made here of the " Lance Spezzate " (broken lances), armed men who for various reasons (desertion, death) had remained without a captain, were directly recruited by the state and organized in companies under the leadership of the captains appointed by them. For their virtue and loyalty, the “Lance Spezzate” were given the privilege of carrying weapons throughout the empire, right into the prince's apartments.

It seems, however, that the Stratiots appreciated awards and privileges over payment, as they sought favors from the Venetian government in the form of parades to show their skills with weapons, which the frugal government was happy to approve. Pietro Bembo describes the Stratiotes in his Istoria Viniziana as follows: “[…] and in those [icy] days in the Grand Canal of the city [Venice in 1491] […], where it had snowed on the frozen waters, some Stratiotes rode to Horse with spears for fun one against the other [...] "

What also impressed the population in the Western European countries were the dances and songs of the Stratiotes: the rhythm of the Tsamikos dance, which the ancestors of the Stratiotes had brought from Epirus to the south of the Greek peninsula, and the melancholy monotonous songs they carried learned on Morea.

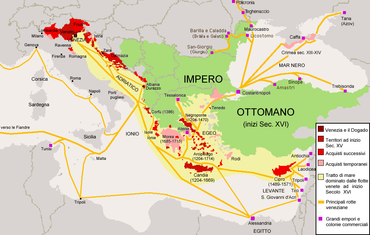

Light cavalry companies of Stradioten were found in the service of a number of European states, such as the Republic of Genoa , the Duchy of Milan , the Duchy of Florence , the Kingdom of Naples , Great Britain , France , the Spanish Netherlands , the Holy Roman Empire and Tsarist Russia . In the sixteenth century they were present in Cyprus , Venice , Mantua , Rome , Naples, Sicily and Madrid , where they presented both their projects and their grievances, asking for barrels of gunpowder or something else, always bossily arrogant and always ready for a fight.

Recruitment and placement

Only in a few cases did the Stratiotes organize themselves into real companies under a captain. The Albanian captains Gjok Stres Balšić (1460), Ivan Strez Balšić (brother of Gjok Stres Balšić) (1460), Georg Kastriota , called Skanderbeg (1460) in the Kingdom of Naples (see: Skanderbeg's military company in the Kingdom of Naples ) and the Greek-Albanian Mercurio Bua (1495, 1513) in the pay of the Republic of Venice.

Usually the Stratiotes were recruited directly from the Venetians among the local populations of Morea and especially among the Albanian clan communities and transported by ship to the Lido of Venice . Marino Sanudo wrote in his diaries: “[…] when the Stratiotes were seen to have an advantage, the matter was included in the“ Consiglio dei Pregadi ”[Senate] and decided to go to Morea to register them and pay them. [...] "

The companies were led by clan members whose names were repeated from the 15th to the 16th century. Among them are the Albanian family names such as Bua, Busicchio, Manes and the Greek family names such as Ralli, Clada and Paleologo. Proper dynasties emerged, each with its own hereditary system of loyalty. In some of them it can be observed that the leaders and most of the soldiers had the same surname and that the leadership passed from father to son.

The family continuity of the leaders was also created by the policy of the Republic of Venice, which systematically encouraged the consolidation of “hereditary fidelity” by granting pensions to widows and orphans. The Republic of Venice never conferred titles of nobility or fiefs on the stratiote leaders, unlike those enlisted by the Kingdom of Naples. The highest honor for the most deserving was given to the honorary title " Knight of San Marco ", which did not belong to a real knightly order . As Marino Sanudo wrote in his diaries, in 1483 some of these stratiote leaders received this title: “[…] The stratiotes were released and sent with our [Venetian] ships to Morea, where they were brought ashore. 50 of these leaders were made Knights of San Marco by our Prince. They received the religious mark in case we needed to induce them to return. They thanked them very much and offered to let others come if our Signoria needed them. [...] "

However, these dynastic chiefs of the Stratiotes were subordinate to one or more "Provveditori agli stradioti" (superiors of the Stratiotes). These were the only patricians who were officially entrusted by the Republic of Venice with an office of commander of the troops of the " Terraferma ".

Appearance

The sources describing the appearance of the Stratiotes are generally consistent. They really looked very strange, wore long beards in the Balkan style, often split into two points and long hair braided in pigtails, which perhaps earned the Stratiotes the nickname “devil's head” among the Swiss.

The French chronicler Jean Molinet describes the Stradioten as follows: "The Stradioten in the Venetian army look very strange, they have long beards."

Jacopo Melza, a notary from Brescia , who saw the Stradiotes at the time of the War of Ferrara (1482–83), gives us an interesting description of their appearance : under the lips of the mouth on the chin and under the nose above the lips of the mouth fork-shaped parts, look very bad. "

A picture of the Stratiotes is in the form of a Deësis from 1546 in the Chiesa San Giorgio dei Greci in Venice. According to the inscription, the commissioners and donors of the work were the Stratiote brothers Ioannis and Giorgios Manessis, sons of Comin.

equipment

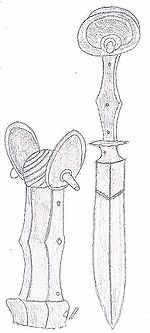

In contrast to the knights of the time, who mostly wore heavy armor , the clothing and equipment of the Stratiotes were fairly simple. As a light cavalry, the stratiotes wore a mixture of oriental and Byzantine costumes without a turban, a cape and a small hat or a light helmet. Their weapons were a throwing lance up to 4 m long, ironed at both ends , long curved Ottoman sabers ( Kilidsch ), mallets , ear daggers and later also rifles or pistols.

The Albanian and Dalmatian Stradioten ( Chevaulegers ), who were in the service of the Republic of Venice until the 17th century, were also called Cappelletti (Sing. Cappelletto) because of their characteristic pointed headgear. This hat was reinforced on the inside with several sheets of paper glued together, which ensured surprising resistance.

Coriolano Cippico reported that the Stratiotes were very predatory by nature and more suited to raiding than fighting. They were armed with shields, swords and spears, a few with breastplate ; others wore a long soldier's coat padded with cotton to protect them from the blows of the enemy. Nafplio's had been braver than anyone else.

According to Jean Molinet, the stratiotes were without armor and without footwear and carried a shield in one hand and a half-lance in the other. A fluttering flag at the top of the lance served them as a standard.

According to Philippe de Commynes, the stratiotes were about uncouth people who were dressed like the janissaries : "on foot and on horseback like the Turks, except for their heads, where they do not wear the shawl called the turban".

Jacopo Melza reported at the time of the war in Ferrara that the Stratiotes were not dressed like the other soldiers, but only with a long padded robe according to their fashion. With their horses, which were equipped with short stirrups, they rode across the country without keeping. Each stratiot had an Ottoman style curved sword .

According to the leaflet of the German printer Hans Guldenmund , the Stratiotes wore long equestrian coats without sleeves, a cylinder-like headgear and were equipped with small round leather shields, light lances or two-pointed spears and possibly also with bows or crossbows. Under their riding coats they wore a dagger attached to their belts, which could cause some inconvenience in close combat.

Sanudo reported that the Stradiotes were Greeks and that soldiers' skirts made of cotton thread, sewn in their own way, wore hats, and several also wore bandages. The Stradioten were described as hardened people who slept outdoors with their large Turkish horses all year round. The horses were made for hard work and were used to high speed. The Stratiotes remained permanently on their horses, which did not eat hay like the Italians. As weapons they carried a lance and a mace in their hand and a sword by their side.

According to Luigi da Porto, the stratiotes “had strange clothing and weapons; [...] their shoes are made of string and the robe reaches to the heels [...] "

Over time, the Stratiotes adopted Western weapons and garments the longer they were in service in Western Europe and in the Venetian territories of the Balkans and Levant. In the Italian wars (1494–1559) the use of armor and helmets increased and the meaning of the shield became less and less important. In France, the stratiot companies that under Louis XII. At the end of the 15th century, their traditional armament was used. Until the time of Henry III. (1574–1589) they adapted to the royal regulations, which led to better protection of the body with more complex and heavier armor.

According to Sanudo, they ate little and were satisfied with everything, the main thing being that their horses were doing well. The best examples cost between 100 and 200 ducats . The Stratiotes bred these horses themselves and, when the military adventure was over, it was common for them to sell their horses to the Italian knights for a good price. Sanudo was astonished to see that these stratiotes, like their horses, fought with their heads held high, whereas in Europe for centuries horses were trained to fight with their heads bowed so that they would present the rider with the least obstacle during the attack. In addition, the Stratiotes used very short stirrups to ensure greater mobility and saddles for long rides.

tactics

The Stratiotes' fame was mainly due to the use of Eastern (no rules) military tactics that they imported into Western Europe. The chronicles that mention the stratiotes describe them as very courageous, resilient, greedy and uncivilized. The fighting style of these men, which was not achieved by western troops, emerged from an innate hostility of the Balkan peoples, which was certainly intensified by the prolonged warfare with the cruel par excellence of the modern age, the Ottomans. The light cavalry tactics of the Stratiotes corresponded to those of the Sipahi and Akıncı of the Ottoman cavalry, which were characterized by high tactical agility and speed. These include attack-like attacks, ambushes, counter-attacks, land destruction and sham retreats in which a retreat was simulated in order to induce the enemy to confuse the armies and to plunge into the pursuit of the stratiotes; then the stratiotes regrouped and attacked the enemy in a semicircle from the side.

An example of these tactics is described by Sanudo: “[…] The guardians of Lecce , who were unwilling to obey, harmed us [Venetians], in particular 500 stratiotes were forced to hide. They sent 30 [stratiotes with their] horses near the gates of Lecce. At this sight, the enemies [Leccesi] came out and our [Stratiotes] pretended to flee and were then pursued outside the city. The stratiotes surrounded them, beat them all, and left the wounded and dead behind them. [...] "

In general, this picture is confirmed and completed by Torquato Tasso in the first cant of the Liberated Jerusalem : “Two hundred Greeks then come drawn, only a little weighted with iron armor. A bow and arrow sound on her back, A crooked sword hangs on one side. The horses, slim, brought up on meager fare, are quick to run, well proven in service. Quickly to attack, to retreat quickly, this people is scattered and still fleeing. "

Luigi da Porto describes these Stradioten in his Lettere storiche (historical letters) as follows: “[…] scattered on one side [the constellation], they attack immediately like demons on the other [side] with even more attention than before; and swim through very wide and deep rivers, and use roads that are almost unknown to the same inhabitants, and so penetrate with incredible silence directly into the interior of the enemy [...] "

The Stratiotes were recruited by the Kingdom of Naples and especially the Republic of Venice and were unknown to the Western forces of the time. When, on the one hand, they were praised for penetrating deep into enemy-occupied land, where opportunities for prey were feasible at will, their behavior was criticized on the other. They are anti-Christian, perfidious, born thieves, potential traitors and so disobedient that they are more harmful to Venice than to the enemy. In the Battle of Fornovo (1495) they turned out to be savages, because when it came to looting, they lost their minds and forgot for what purpose they were recruited. (See below: Republic of Venice )

A macabre custom of the Stratiotes has been passed down, which they very likely adopted from the Ottomans. The stratiots did not take prisoners, but simply chopped off the heads of their enemies, thus ruining the possibility of demanding a ransom. The heads of the slain enemies were usually carried on the saddle button (see here left). According to their custom, they received one ducat per head from their commanding officer.

Philippe de Commynes describes this cruel custom in his diaries: “[...] These [stratiotes], who besides one of these armed men killed on horseback, chased the others into the marshal's chamber , where the Germans camped, including them killed three or four; afterwards they rode away with their heads, according to their custom; the Venetians, who were already at war with the Ottoman Mehmed II [...] and [Mehmed] did not want prisoners to be taken, but rather had their heads cut off, for which [he] gave them [Stratiotes] one ducat per head , the Venetians did the same. I think they wanted to scare our [French] army, which they did [...] ”

Sanudo also reported on their cruelty: “The Stratiotes who were in Crema […] decided to cross the Adda and rode near Milan , from where they met 300 crossbowmen who were surrounded by the Stratiotes. Many were killed and their heads chopped off, which were tied to their belts for the customary bonus. Others had their tongues or hands cut off and sent back to Milan to let their cruelty be known there. "

Jacopo Melza reported on the tactics of the Stratiots at the time of the War of Ferrara (1483): “Every Stratiot had an Ottoman-style curved sword that cut off [the head] at the first cut and, in order to achieve this, rose on the With short stirrups and a short movement they carried out their blow, then turned around and fled with their horses. "

The Italian historian Francesco Guicciardini gives us an interesting picture of the extreme mobility and speed of the Stradiotes : “[…] It is known that the Cappelletti [Stratiotes] of the Venetians, divided into several departments, can be found throughout the country, day and night afflict the army and cause great harassment together with the others, he ( Maximilian I ) said to his [soldiers], adding to beware of the cappelletti [...] that they [cappelletti] like God everywhere to be found. [...] "

The barbaric practice of the stratiotes was rejected and condemned by both the enemies and allies of Venice - but nothing was done. The habit of venting its anger on the prisoners also caused a stir, because in Italy and across Europe in general there was a kind of “unofficial” code that treated every captured enemy with a certain respect; a kind of internal "ethical" code that followed the logic of the mercenaries: professional soldiers who were always in danger of falling into the hands of the enemy.

The stratiotes were also masters in the expeditions carried out in the high mountains, which was a rarity for a cavalry corps. You were z. B. 1508 used in the Battle of Cadore near Pieve di Cadore . Given the inaccessible conditions, the mountain world was an area where soldiers had considerable difficulty in providing their offensive skills, which remained to the more skilled and nimble Balkan knights.

According to a graphic (see here on the right) by Hans Guldenmund, the special fighting tactics of the fast riders from the Balkans is described: “The picture shows a stradiot; these are special fighters. In the skirmish they ride up impetuously. If the enemy flees, they pursue him violently; if he stands up, turn around soon and shoot many arrows behind you. This people is just fighting in a hurry. "

Stradiotes shooting arrows appeared in any case in 1529 during the first siege of Vienna's Ottomans at the gates of Vienna , here apparently on the side of the Ottoman aggressors.

Stratiots in the Byzantine Empire

As in Asia Minor new administrative districts which topics have been created whose commanders were all military and civilian powers for the area transferred and were subordinate to the emperor directly. Within the themes, fortified farmers were settled who, according to the Byzantine theme organization, lived on the yields of their land, performed military service and received tax exemptions in return. In peacetime they cultivated their own land and in the event of a defense they had to serve as military service. For the most part they served as foot soldiers , but some were also used in light cavalry . Armenians , Magyars , Khazars , Rus , Serbs and Bulgarians were recruited through treaties with the respective rulers.

The Byzantine army, based on the Stratiotes, was very successful from the 8th to the 10th centuries. Numerous further Ottoman attacks on the remaining core area of the empire (Asia Minor) could be repulsed and in the second half of the 10th century Byzantium went on the offensive, in which large areas in the Balkans as well as in the east could be recaptured.

At the time of Michael VII (1067-1078) the bulk of the army consisted of foreign mercenaries. Among them were Varangians and Rus of the Volga River , Franconia , Turkmen , Pechenegs , Cumans and Guzzen ( Oguz ). In addition to mercenaries, there were also foreigners who did not volunteer in the Byzantine army . These included deportees , prisoners of war and slaves .

After the catastrophic defeat of Manzikert on August 26, 1071 and the associated extensive loss of Asia Minor, the thematic system could no longer be maintained. It was replaced by the Pronoia system, which lasted until 1453 (the year the Byzantine Empire fell). The system consisted of granting land in exchange for military service. The Pronoiai system developed into a kind of tax tenancy . The owner of a Pronoia, Pronioiardo, collected taxes from the citizens (paroikoi) who lived within the boundaries of the assigned area and kept part of it as payment.

Pronoiai troops were usually cavalrymen and were much like Western knights in their armament and equipment, with lances, swords and armor for horse and rider. At that time the army was composed of mercenary detachments, among which in the central part of the army were the Scythikons (archers) of Cuman origin, the Tagmats and, above all, Pronioiardi.

Stratos in European countries

With the advance of the Ottomans towards the northwest between the 14th and 15th centuries, an alliance formed in the Mediterranean between the Albanian principalities, the Republic of Venice, the Italian lords and the kings of Naples and Sicily , who on various occasions met Spain and France , the Roman papacy , the Eastern European countries and the African Mediterranean. This alliance continued later in the Italian wars of the 16th century. In this political and social situation, particularly skilled mercenary armies were needed and the Stratiotes with their Albanian captains from “good families” formed an efficient, highly trained cavalry.

During the four centuries of Ottoman rule in the Balkans, many Christian stratiotes found protection with the surrounding Christian powers and served in their armed forces. Greek and Christian Albanian troops served the Republic of Venice and the Spanish rulers in Italy ( Aragonians , Habsburgs and Bourbons ) and in the Balkans.

During the Ottoman-Venetian Wars of the 15th century, large numbers of Stratiotes who had served the last Christian states in the Balkans found employment in the Venetian possessions in Greece and, after 1534, in Dalmatia. Venice also promoted the settlement of Stratiote families in their possessions with privileges. In 1485 Venice offered undeveloped land on Zakynthos to a stratiot company .

The Albanian Chevaulegers became a standard part of the armed forces almost everywhere in Italy and in other armies as well. During the Battle of Avetrana in Apulia on April 19, 1528 Albanian Stradiotes recruited from the Kingdom of Naples, which was under Spanish rule, fought against the Greek-Albanian Stradiots hired by the Republic of Venice. One could say that in much of Europe, as a result of Skanderbeg's long struggle against the Ottomans, his own reputation as a hero of Christianity and the descendants of his cavalry had spread.

As stratiote units became hereditary and the military capabilities of these older stradiot companies declined, the number of these companies employed in Italian and other Western armies dwindled at the end of the 16th century. They were replaced in many European armies with the creation of light cavalry formations based on the Stratiote tradition. This trend reversal was also determined by the scientific-military revolution that restructured and redesigned the European armies in the second half of the 16th century, rendering the tactics of the Greek-Albanian stratiotes obsolete. The new units, made up of indigenous or different ethnic groups, also added firearms to their armor, so the mention of Stratiots, Albanians, Greeks, etc. became increasingly rare. The stratiots gradually integrated themselves into the society of the host country.

During the Thirty Years War , the Republic of Venice recruited lesser-known infantrymen of Greek origin, the so-called Greek companies or militias.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, new military organizations emerged that extended the tradition of the Balkan legions in Venice and Naples. The two largest foreign regiments, consisting of Balkan troops, were the Venetian Reggimento Cimarrioto and the Reggimento Real Macedone (light Balkan infantry ) of Naples. While the Reggimento Cimarrioto was organized by the Venetians during the Fifth (1645-69) and the Sixth Ottoman – Venetian War (1684–99) (Morea War) , the Reggimento Real Macedone was shortly after the establishment of the independent Kingdom of Naples (1734) under the Spanish Charles III. educated.

Republic of Venice

During the 15th century, the Stratiotes served in the armies of Venice, Milan , Genoa , France, England, and the Holy Roman Empire.

The organization of the Venetian army was mainly based on the individual stratiot captains and the state. Over time, the nature of the contractual relationship changed. The duration of the contracts became longer and included both war and peace service. The majority of the generals conformed to the permanent service and the renewal of their contracts became a formality.

In the second half of the 15th century, the payment was standardized to about seven or eight ducats per lance and the payment was fixed at ten times a year, so that the amount of the fee was often given as 70 or 80 ducats per year. The infantry received two to two and a half ducats per man per month, and stratiots 4 ducats per month plus two sacks of corn. In the 1490s the standard wage rate was increased to 100 ducats per lance per year. It must be taken into account that a lance was increased from four to five men.

During the war campaigns, the stratiotes either slept outdoors or were billeted with the civilian population, which led to friction, so that every evening a special troop was busy assigning new accommodations. In peacetime, the army was housed in permanent shelters in the areas of Brescia , Verona , Vicenza and Trevignano or in the border zones of Ravenna , Crema , Bergamo and Gradisca d'Isonzo . There were no barracks for troops, so the stratiotes in the cities rented houses within the fortified complexes, where they put their families with them. The Stratiotes also valued the right granted to them to practice their religion, the Byzantine rite , be it Orthodox or United, and were instrumental in the founding of the Greco-Byzantine churches in Venice, Naples and the cities of Dalmatia.

Mpires estimates that the number of Albanian and Greek stradiots who settled in the Venetian territories and Italy reached 4,500 men, and together with their families they numbered about 15,500. If one includes those who settled in southern Italy and Sicily, the numbers reach around 25,000. (See: Arbëresh )

When their "customers" began to form local light cavalry units, such as the later hussars and dragoons , the employment opportunities of the Stratiotes were limited to the Venetian possessions in the Peloponnese (Koroni, Methoni, Nafplio and Monemvasia ), on the Ionian Islands ( Kefalonia , Corfu , Kythira , Zakynthos) and in the Eastern Mediterranean ( Crete and Cyprus ).

First Ottoman – Venetian War (1463–79)

Coriolano Cippico , who was involved in the First Ottoman – Venetian War (1463–79) at the side of Captain General Pietro Mocenigo from 1470 to 1474 , reported of the Stratiotes that they were generous men ready for any great enterprise. With raids they had so badly destroyed the part of Morea that belonged to the Ottomans that it was almost deserted.

War of Ferrara (1482–1484)

As courageous warriors armed for every danger, the statiots were introduced to the "Terraferma" by the Venetians in the War of Ferrara (1482–1484) in the 1480s. After Sanudo, on April 22nd [1482] the first Arsil (ship without mast and rigging ) with 107 stratiotes from Koroni under Alegreto from Budva called the Lido of Venice. When the Stratiotes disembarked, they paraded in their usual manner. The crowd present marveled at the speed of the horses and the skill of the riders. On March 12th [1484] an Arsil with 98 Stradiotes and their barbaric horses from Nafpaktos docked in the port of Venice. On March 22nd, another Arsil reached the port of Venice with 112 Stradioten and their horses from Methoni. Every day another Arsil arrived until in the end there were eight Arsil with 1000 stratiotes and their horses.

“The stratiotes sent an act of grace to the Venetian Signoria” because they did not want a commission, as was customary among soldiers, but instead demanded two ducats for each living “head” and one for each dead, as was customary. In addition, because of their customs, they demanded a noble local commander and not a foreign (Albanian) one, as was the custom. The pay of the stratiotes was lower than that of western mercenaries (Italian, Swiss, German or others) at least until 1519.

Battle of Fornovo (1495)

In the Battle of Fornovo (1495) the Stratiotes forgot their duty and plundered 35 pack horses of the French baggage train , spoils of war valued at at least 100,000 ducats, which fell into the hands of the Venetians. The looted property included the sword and helmet of the French King Charles VIII , two Royal Standards , several royal pavilions (tents), the king's prayer book, relics , precious fittings and items from the royal chapel. Alessandro Benedetti , a Venetian doctor who served in the Army of the Holy League , reported that he saw in the spoil an album full of portraits of the mistresses whom Charles had shown affection for in the various cities of Italy. After the undisciplined stratiotes had satisfied themselves with the looting, they preferred not to take part in the now quite bloody battle. Since the remaining Venetians could not follow up and thus bring about a decision, the remaining troops of Charles VIII managed a happy retreat across the Alps. The Venetians and their allies had temporarily rid of the French and the rich booty served the Venetian Signoria as a pretext for a claim to victory in which she promised her military commander Gianfrancesco II Gonzaga a triumphant entry and a splendid reward.

Nevertheless, in the following campaigns, the Stratiotes convinced the Venetians and their opponents with their tactics of attack-like attacks, sham withdrawals and counter-attacks, which led the opposing forces to continue. The enemy forces lost their line-up and became more and more susceptible to the Stradioten attacks, so that the opponents had to use their infantry with arquebuses or artillery to defend against the Stratiotes.

Ottoman-Venetian Wars (16th - 18th centuries)

Even in the Ottoman-Venetian wars of the 16th and 17th centuries, the stratiotes were an essential part of the land forces that the Republic of Venice led into the field. When the Republic of Venice lost Morea to the Ottomans in the Third Ottoman – Venetian War (1537–40), it became extremely difficult for Venice to locate Albanian-Greek stratiotes. As a result, the cappelletti (soldiers of the light cavalry) and the "overseas troops" consisting of the Dalmatians , Schiavoni , Morlaken and Çamen acquired more relevance within the Venetian military organization. The main areas of application of these stratiotes were the Venetian-Ottoman border in Istria , Friuli in Italy, the Dalmatian coast ( Herceg Novi , Šibenik , Split , Trogir , Kotor and Zadar ) and the islands in the Aegean Sea . The latter were located in an area in which, in the event of enemy counter-attacks (especially by the Ottomans), rapid intervention was possible and decisive.

Ionian islands

In the Ionian Islands, the Stratiotes continued their services into the 18th century. These stratiotes were descendants of refugees from the lost Venetian possessions on the mainland who had settled on the islands in the 15th and 16th centuries. They received land and privileges, served as cavalry, and took part in the Ottoman-Venetian wars during the 17th century. Eventually these units became a hereditary rank. Some of the stratiots or their descendants became members of the Ionian nobility over time, while others were engaged in farming and other occupations.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Venetian authorities were forced to reorganize the stratiot companies. On Zakynthos, for example, they reduced their numbers and privileges as a result of absence and indiscipline. The stratiot companies of Corfu existed until the end of Venetian rule and French occupation in 1797.

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples was another center of military activity and colonization for Balkan peoples under the Spanish Aragonians (1442–1501, 1504–1555), the Habsburgs (1516–1700, 1713–1735) and the Bourbons (1735–1806).

While the Republic of Venice also entered into trade relations with the Ottomans, the representatives of Spain in southern Italy always showed a hostile attitude towards the Ottomans. They never allied with them (until the mid-18th century) and were unable to create commercial interests of any kind in the eastern Mediterranean and other sultans' territories .

Despite the opposition from Venice, the Spaniards did not hide their efforts to expand their political influence to the nearby Balkan Peninsula . Both in relation to this tactic and in view of the general policy of Madrid, the viceroys of Naples and Sicily always had to have strong armed forces ready, ready on the one hand to avert possible uprisings by the local barons and on the other hand to pose the uninterrupted Muslim threat to stop the Balkans. Due in particular to the Muslim threat, strong naval units had to be maintained to fend off the constant attacks of the Muslim pirates of North Africa (which for centuries the coasts of the two kingdoms, Sardinia and the same Eastern Iberian Peninsula ) and a possible Ottoman invasion that had been going on since the time of Mehmed II ( 1444–1446, 1451–1481), the conqueror, always hung like a sword of Damocles over the Calabrian and neighboring coasts. The Greeks and Arbëresh (name of the Albanians in the region of what is now Albania in the 15th and 16th centuries), who at that time already lived in the Kingdom of Naples (and to a certain point also those of Sicily), thus found the opportunity to get involved in the Sicilian navy or in the Neapolitan light cavalry (stratiotes) and thus fulfilled a double need: to be paid well by their Spanish superiors and to let their hatred of the Ottomans run free.

Local riots

Under King Ferdinand I (1458–1494) from the Spanish house of Aragon , Albanian stratiotes were deployed from 1460 to 1462 against the uprising of the local barons (1459–1462) in Apulia ( Terra di Bari and Terra d'Otranto ), in which the Albanian prince and military commander Georg Kastriota, called Skanderbeg, participated with his troops himself. After the battle, a garrison of Albanian stratiotes was left behind to defend any rebel incursions.

The Spanish King Ferdinand II (1495–1496) used the elite cavalry of the Stratiotes as a private guard and to defend the city of Naples against the Albanian Stratiotes who were hired by the French and who fought in the Kingdom of Naples.

Under the Spanish King Ferdinand III. of Aragon (1504-1516) the great captain Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba y Aguilar was sent to southern Italy to support the Kingdom of Naples against the French invasion. In Calabria Gonzalo had 200 Greek stratiotes, very selected riders and 500 Italian farmers at his disposal.

The Viceroys' anti-Ottoman policy

The most important task of the viceroys of Naples and Sicily was to prevent a possible surprise from the Ottomans. Therefore, they always needed to be informed of any movement of the Ottoman fleet, their supply centers, their commanders and officers, the Ottoman shipyards and their ability to build or repair warships and their plans for future military action. Occasionally the viceroys had to support sabotages in the most important Ottoman naval bases, such as Constantinople. In times of war had to be created for deflecting the Ottoman pressure distraction caused by insurgent movements at various points of the southern Balkans and particularly in troubled and inaccessible mountain regions, as in Maina and Çamëria are formed where the residents were always willing to take action against the Ottomans.

So a network of spies, agents and saboteurs was gradually organized, who carried out their activities against payment, but also for sentimental reasons in the Ottoman capital Constantinople, on Evia, on the Morea and in other Ottoman centers, such as in distant Cairo , in Alexandria or practiced in Syria . These " Espias " (spies), " Confidentes " (confidants), " Agentes " (agents) or " Embajadores " (ambassadors) were in constant contact with the governors of Bari and Terra d'Otranto. Countless " Avisos " (reports) were transmitted by various means , which were not always absolutely reliable or up-to-date. These were the positions of the Ottoman fleet, the new viziers and other officers of the Sultan, famines, epidemics, fires and other accidents in the various Ottoman territories, newly appointed rowers and janissaries, rebellions of the Ottoman pashas and other events of this nature.

It also reported about suspicions of various trustworthy or questionable people who were informed about the Sultan's plans and his future offensives. One example is a list of informants and agents of the Kingdom of Naples from the years 1531–1533: Giovanni Ducas reported from Vlora ; from Corfu Giorgio Bulgaris, Nicolò Faraclòs, Giacomo Cacuris (son of Francesco), Giovanni Cacuris (son of Giacomo), Pietro Cocalas, Michelis Coravasanis, Pietro Cotsis and Andrea Sachlikis; from Zakynthos Giacomo Siguros and Giovanni “de lo Greco” (the Greek); from Kefalonia Giorgio “de Cefalonia” (from Kefalonia); by the Morea Nicolò Gaetanos, Michalis Carviatis, Giorgio Covalistis, Giacomo Gaetas, Michails Pasacudillis, Demetrio Rondakis and Paolo Capoisios. News of special missions to Constantinople and other regions of the Ottoman Empire were regularly brought to the Kingdom of Naples by Giorgio Cechis and Giovanni Zagoritis. The number of such informants increased from 1569.

These missions usually started on the eastern banks of Lecce and Otranto ; but the center of the organization was the Greek quarter of Naples or, according to a Venetian confidante, “[…] on the Via dei Greci (street of the Greeks), which was inhabited by these nations (Albanian and Greek stratiotes) and notorious Neapolitan women; not far from the Viceroy's palace and near the Spanish Quarter, that is, in the center of Naples. “The meeting place was usually the Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo dei Greci of Naples and acted as mediator between the various conspirators, rebels, spies, etc. and the viceroy, the pastor, who also had the spiritual supervision of the whole colony and was usually a former student of the Greek College of Saint Athanasius in Rome.

Information about this type of activity from the Greeks and Albanians of Naples began at the beginning of the 16th century. They increased significantly after the appearance of Emperor Charles V (1516–1554) in Italy and around 1530 the organization of anti-Ottoman politics began. From then on, the agents were sent to Greece with instructions, where they usually returned with compatriots who, after the discovery of their conspiracy, had to flee to the Kingdom of Naples. From 1530 the main instrument of this policy was the governor of the provinces of Bari and d'Otranto Giovanni Battista Lomellino, Marquis of Atripalda († 1547). This marquis sent a large number of Greek spies to various important regions of the Ottoman Empire and kept secret contacts with numerous Greeks and Albanians who expressed a desire to rebel against the Ottomans. Giovanni Battista Lomellino usually supported these rebels with weapons and gunpowder and with favorable reports to Charles V, whom he tried to convince during his conflict with Suleyman I (1533–1544) to support the revolutionary plans of the Greeks, Albanians and Slavs. In one of his reports to the emperor, written in Naples on July 6, 1530, he reported that the inhabitants of Greece “are waiting with open arms for this holy day” on which the Spanish would decide to conquer Romania.

Lomellino also fueled the rebellions in northern Albania, became an ardent supporter of the Çamen's attempts to maintain their autonomy with the rebellion of 1530–1532 and finally became a spokesman after the temporary Spanish occupation of the region of Koroni (1532–1534) the residents of Morea in their petitions to Christian powers.

Between 1532 and 1534, many Greek-Albanian Stradiotes and their families from Maina , Methoni , Nafplio and Patras on the Peloponnese settled in the lands of the Kingdom of Naples, where they received land and citizenship from the local feudal lords in sparsely populated areas. Most of these settlements were given both military privileges and duties. However, these conventions lapsed in the course of the 18th century. (See also: The fourth wave of migration of the Arbëresh (1468–1506) , The fifth wave of migration (1532–1534) , The sixth wave of migration (1600–1680) )

The Spanish Habsburgs also recruited statiots in the 16th and 17th centuries, who were deployed mainly in Naples and other parts of Italy. The main recruiting area for these troops was Çamëria in Epirus.

In the Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo dei Greci in Naples there is a tombstone from 1608 with the following inscription:

ordinaria in questo regno,

di trecento cavalli, nominati Sdradioti,

The recruitment and maintenance of stratiot troops continued in the Kingdom of Naples until the early 18th century.

France

In the Middle Ages, Greece often gave light riders to French services known as Estradiots and Argoulets . The best-known name at that time, however, was that of the Greek or Albanian cavalry. They came from the Venetian possessions in Greece, from Nafplio , capital of Morea, and partly from Albania near Durrës.

In the Battle of Fornovo (1495) near Parma , the French troops faced the cruel and indefatigable Balkan horsemen, the Stratiotes, for the first time. The battle was fought between the armies of the anti-French Holy League and the French army of Charles VIII. The commander in chief of the allied troops was Gianfrancesco II Gonzaga , Margrave of Mantua , captain general of Venice. With his nearly 25,000 men (of whom about 5,000 were in the pay of Milan; all others, including a contingent of almost 2,000 stratiotes in that of Venice; while the French had a total of about 11,000 soldiers) he felt strong and challenged the invading army in the instead of blocking the Apennine crossings.

The battle plan that the Italian commander had worked out with the help of his veteran uncle Ridolfo was very complex and based on a coordinated action by several troop positions which, by attacking at the same time, should have broken up and confused the army of Charles VIII. In the meantime, the Stratiotes should bypass the enemy and then pounce "like eagles" from the hills on the French vanguard , which should lead to further unrest among the enemy troops and prevent the enemy from escaping over the hills. However, the Italian plan fell into crisis from the start, both because of the heavy rains that had swollen the waters of the Taro River and because of the difficulty of coordinating the various columns and the various departments. In addition, the stratiots showed indiscipline and greed: after reaching their first objective and allowing the Milanese cavalry to prevail against the French vanguard, they withdrew from the fight, pillaging the enemy entourage and stealing much of those from the French during theirs Campaign amassed booty, thus undoing the original aim of surrounding enemy troops.

An eyewitness to the Battle of Fornovo, Philippe de Commynes, described the episode in his memoir as follows: “They sent some of their stratiotes, crossbowmen on horseback and some armed men down a road that was very overcast. After they had crossed the river and came into the village, they attacked our entourage, which was very large. ”In addition,“ the Stradioten killed a French nobleman named Leboeuf, cut off his head, and brought him triumphantly on the head of a Fähnleins Lance her Provveditore [superior] to get a ducat paid for it. ”Shortly after returning home, King Charles VIII paid 400 stratiotes. (See above: Republic of Venice )

When Louis XII. went to the field against the Genoese in 1507, he recruited 2000 Stradiotes. After Louis subjugated the city, the French poet Clément Marot , who was then living in Genoa, dedicated a few verses to the Stratiotes:

You wield the blades like knights,

you wave your banner and ride so fast

During the Huguenot Wars (1562–1598), the Albanian cavalry fought on the side of the army of the kings of France.

Spain

Since Spain and Naples were connected to the Holy Roman Empire by Charles V in the first half of the 16th century , stratiotes were soon installed for the Spanish Habsburgs not only in Italy, but also in Germany and the Netherlands.

Among those who distinguished themselves in the Habsburg service and became knights of the Holy Roman Empire were the captains Giacomo Diassorino, Giorgio Basta , the brothers Vassilicò and the dreaded Mercurio Bua.

Spanish Netherlands

During the Spanish-Dutch War , the Spanish army in Flanders had Albanian stratiots armed with spears in the 1570s, and in 1576 there were Albanian stradiots in Brussels . During the twelve-year armistice from 1609 to 1621, Teodoro Paleologo (* Pesaro 1578 approx .; Clifton, Landulph, Cornwall 1636) was paid by the English in the Netherlands.

Great Britain

Also in Great Britain under Henry VIII were during the Anglo-Scottish Wars (1514-1541) and the Siege of Boulogne (1544) units of Greek-Albanian Stratiotes under the Greek captains Thomas Buas of Argos , Theodore (or Theodoros) Luchisi and Antonios Stesinos used. The former became colonel and commander of the 550 stratiotes in the garrison in what was then Calais, England .

In the English civil war (1642-1651) between the royalists and parliamentarians , the brothers Teodoro (* 1609) and Giovanni Palaiologos (* 1611) fought as high-ranking officers against each other for both parties. Tombs of the Palaiologos are located in the parish church of St Leonard and St Dilpe in Landulph, Cornwall , in Westminster Abbey in London and on the island of Barbados .

Holy Roman Empire

In the war of the Holy Roman Empire against the Republic of Venice, the imperial troops under Paul Sixt I von Trautson suffered a heavy defeat on March 2, 1508 in the Battle of Cadore . The Stradiots fighting on the side of Venice, a swift and particularly feared troop of light riders, beheaded many of the imperial troops, for which they received a bounty, a ducat for each head. After this experience, Emperor Maximilian I also recruited mercenaries. Were wanted for their special ability in addition to the German mercenaries , mercenary from the Kingdom of Bohemia , but also 400 Greek-Albanian Stratioten. The emperor valued the stratiotes and even kept them occasionally in his guard .

Archduchy of Austria

When Empress Maria Theresa had to defend her western countries in the War of the Austrian Succession against Prussia and France after the death of her father Charles VI , she deployed Albanian stratiotes.

Notable stratiots

- Giorgio Basta (born January 30, 1550 in Rocca in the province of Taranto ; † August 26, 1607 in Vienna or November 20, 1607 in Rocca near Taranto)

- Mercurio Bua (* 1478 in Nafplio, † 1542 in Treviso ); received titles from the Spanish Habsburgs, Venetians and French

- Giacomo Diassorino , (* 16th century in Rhodes ); served in the army of Charles V in Italy and France.

- Krokodeilos Kladas (1425-1490)

- Lazzaro Mattes (or Lazaro Mathes), Giovanni Mathes and Angelo Mathes (sons of Lazzaro)

- Graitzas Palaeologus (1429-1492) from the family of Palaiologoi

- Costantino Paleologos, Manoli Paleologo.

- Matthäus Spandounes (or Spadugnino), a stradiot whose heroic deeds earned him the title "Count and Knight of the Holy Roman Empire".

- Michael Tarchaniota Marullus (* 1453 probably in Constantinople, † April 12, 1500 in Volterra ), humanistic scholar, Latin poet and soldier of Greek origin.

- Giacomo Vassilicò (* 16th century); Cousin of Giacomo Diassorino; Stratiot captain in Charles V's army in Italy and France

See also

literature

- Franz Babinger : Albanian Stradioten in the service of Venice in the late Middle Ages . In: Studia Albanica . tape 1 . Academy of Sciences of Albania, Tirana 1964, p. 162-182 .

- Coriolano Cippico: Della guerre de 'Veneziani nell' Asia dal 1470 al 1473 . Carlo Palese, Venice 1796 (Italian, online version in the Google book search).

- Andrea Gramaticopolo: Stradioti: alba, fortuna e tramonto dei mercenari greco-albanesi al servizio della Serenissima . Soldiershop, 2016 (Italian, online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- John F. Haldon: State, Army and Society in Byzantium. Approaches to military, social and administrative history, 6th - 12th centuries . Aldershot 1995, ISBN 0-86078-497-5 .

- ME Mallett, JR Hale: The military organization of a Renaissance state. Venice c. 1400 to 1617 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, ISBN 0-521-24842-6 (English, online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- Donald M. Nicol : Byzantinium and England . In: Balkan Studies . Institute for Balkan Studies, 1974 (English, uom.gr ).

- Raphael and Benjamin Herder: Stradioten . In: Herders Conversations-Lexikon . tape 5 . Freiburg im Breisgau 1857, p. 349 ( zeno.org [accessed November 5, 2017]).

- Charles Oman: The History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century . EP Dutton, New York 1937 (English).

- Nicholas C. Pappas: Balkan foreign legions in eighteenth-century Italy: The Reggimento Real Macedone and its successors . Columbia University Press, New York 1981 (English, macedonia.kroraina.com [PDF; accessed November 4, 2017]).

- Heinrich August Pierer: Stradioten . In: Pierer's Universal Lexicon . tape 16 . Altenburg 1863, p. 886 ( zeno.org [accessed November 5, 2017]).

- Marino Sanuto: Commentarii della guerra di Ferrara tra Li Viniziani ed il duca Erdole d'Este . Giuseppe Picotti, Venice 1829 (Italian, online version in the Google book search).

- Marino Sanuto: La spedizione di Carlo VIII in Italia . Marco Visentini, Venice 1883, p. 313-314 (Italian, archive.org ).

- Stathis Birtachas: La memoria degli stradioti nella letteratura italiana del tardo Rinascimento . In: Tempo spazio e memoria nella letteratura italiana . Tabucchi Aracne Editore, Rome 2012, ISBN 978-88-548-5139-9 , p. 123-141 (Italian).

- Nikos G. Svoronos: Les novelles des empereurs macédoniens concernant la terre et les stratiotes . Athens 1994 (collection of sources on land law and the stratiotes at the time of the Macedonian dynasty).

- Warren T. Treadgold: Byzantium and its army. 284-1081 . Stanford (CA) 1995, ISBN 0-8047-2420-2 .

Remarks

- ↑ Debbe adunque uno principe non avere altro obietto né altro pensiero, né prendere cosa alcuna per sua arte, fuora della guerra […] e per avverso si vede che, quando e 'principi hanno pensato piú alle delicatezze che alle poor, hanno perso lo stato loro [...]

- ↑ […] alla strada delli greci, populatissima di quella natione et di donne infami napoletane; questa non è molto lontana dal palazzo del Signor viceré et vicina al quartiero delti spagnuoli, che vuol dir nella maggior frequentia de Napoli.

- ↑ [...] están con los brazos abyertos esperando esto sancto dia [...]

- ↑ The kings of Naples named parts of their property (or claim to possession) east of the Adriatic Romania, which meant Epirus, Aetolia , Acarnania and the settlement area of the Aromanians , especially in central Greece with the capital Metsovo .

- ↑ Here rest the two captains of an ordinary company of 300 horses of the kingdom, called Stratioten, granted to the families of the Albanian captains mentioned by the royal crown of Spain in 1608.

Web links

- The Palaeologus Family. Accessed May 17, 2019 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Louis Tardivel: Répertoire des Emprunts du français aux langues étrangères . Septentrion, Québec 1991, ISBN 2-921114-51-8 , pp. 134 (French, online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- ^ Wilhelm Pape : στρατιώτης . In: Concise dictionary of the Greek language . tape 2 . Braunschweig 1914, p. 952 ( zeno.org [accessed November 3, 2017]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Nicholas CJ Pappas: Stradioti: Balkan mercenaries in fifteenth and sixteenth century Italy. In: De.scribd.com. Sam Houston State University, accessed November 6, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c Coriolano Cippico, p. X

- ^ Paolo Petta: Stradioti. Soldati albanesi in Italia (sec. XV-XIX) . Argo, Lecce 1996, ISBN 88-86211-86-4 , pp. 43 (Italian).

- ^ Stradioti. Retrieved October 5, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Stathis Birtachas, p. 125

- ↑ a b c d e Marino Sanuto: Commentarii della Guerra di Ferrara tra li Viniziani ed il Duca Ercole d'Este nel 1482 . Giuseppe Piccotti, Venice 1829, p. 114 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Kostas Mpires: Οι Αρβανίτες, Οι Δωριέων του Νεώτερου Ελληνισμού . Athens 1960, p. 191-192 (Greek).

- ↑ a b Georgios Theotokis, Aysel Yildiz: A military history of the Mediterranean Sea: aspects of war, diplomacy and military elites . Brill, Boston 2018, ISBN 978-90-04-31509-9 , pp. 328 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Stathis Birtachas, p. 126

- ↑ a b Paolo Petta, p. 42.

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 41

- ↑ a b Lucia Nadin: Migrazioni e integrazioni: Il caso degli albanesi a Venezia (1479–1552) . Bulzoni, Rome 2008, ISBN 978-88-7870-340-7 , pp. 59 (Italian). }

- ^ A b Filippo Di Comines: Delle Mémorie Di Filippo Di Comines, Caualiero, & Signore d'Argentone . tape VIII. . Bertani, Venice 1640, p. 271 f . (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Andrea Gramaticopolo, p. 28.

- ^ A b Hermann Wiesflecker: Austria in the age of Maximilian I: the unification of the countries to form an early modern state: the rise to world power . Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-7028-0363-7 , p. 270 .

- ↑ a b c Stathis Birtachas, p. 124

- ↑ Niccolò Machiavelli: Il principe . ISBN 978-88-97313-36-6 , pp. 56 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Piero Del Negro: Guerra ed eserciti since Machiavelli a Napoleone . Editore Laterza, 2012, p. 3 (Italian, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Angiolo Lenci: Il leone, l'aquila e la gatta: Venezia e la Lega di Cambrai: guerra e fortificazioni dalla battiglia di Agnadello all'assedio di Padova del 1509 . Il Poligrafo, Padua 2002, p. 30 (Italian).

- ^ A b La spedizione di Carlo VIII in Italia, p. 509

- ^ A b Fernand Braudel : The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II . tape 1 . University of California Press, Berkeley 1996, ISBN 978-0-520-20308-2 , pp. 48 (English, online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Piero Del Negro, p. 6.

- ^ Angiolo Lenci, p. 36

- ↑ Francesco Tajani: Le istorie albanesi . Tipi dei Fratelli Jovane, Palermo 1886, p. 47 (Italian, archive.org , Capo III., 2.).

- ↑ Stathis Birtachas, p. 127

- ^ Pietro Bembo: Della Istoria Viniziana . In: 12 . tape 1 . Venice 1790, p. 37 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Stathis Birtachas, p. 129

- ^ Alfredo Frega: Scanderbeg eroe anche in terra di Puglia. In: arbitalia.it. Retrieved December 2, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Jann Tibbetts: 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time . Alpha Editions, New Delhi 2016, ISBN 978-93-8550566-9 , pp. 575 (English, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Skënder Anamali, Kristaq Prifti: Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime . Botimet Toena, Tirana 2002, p. 387 (Albanian).

- ↑ a b Paolo Petta, p. 70

- ↑ Commentarii della Guerra di Ferrara ..., p. 51

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 85

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 66

- ↑ a b c M. E. Mallett, JR Hale, p. 376

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 67

- ^ Commentarii della Guerra ..., p. 148

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 64

- ↑ a b c d Paolo Petta, p. 46

- ↑ a b c d Eugène Fieffé: History of the foreign troops in the service of France, from their formation to our days ... Deschler, Munich 1857, p. 78 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Balkan foreign legions in eighteenth-century Italy, p. 35

- ↑ Cappelletti. Retrieved October 5, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Paolo Petta, p. 48

- ↑ Eugène Fieffé, p. 81.

- ↑ a b Paolo Petta, p. 49 f.

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 47

- ^ A b c d Marino Sanuto: La spedizione di Carlo VIII in Italia . Tipografia del Commercio di Marco Visentini, Venice 1883, p. 313 (Italian, archive.org ).

- ↑ Luigi da Porto, p. 41

- ↑ a b Paolo Petta, p. 51

- ↑ Commentarii della Guerra ..., p. 115

- ^ A b Frederick Lewis Taylor: The Art of War in Italy, 1494-1529 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1921, pp. 72 (English, archive.org ).

- ↑ Commentarii della Guerra ..., p. 152 f.

- ↑ Torquato Tasso: Liberated Jerusalem. First chant, verse 50. In: Zeno.org. Accessed January 31, 2018 .

- ↑ Luigi da Porto: Lettere storiche scritte dall'anno 1509 al 1512 . Tipografia di Alvisopoli, Venice 1832, p. 30 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ Charles Oman : A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century (reprinted 1937) . Greenhill Books, London 1999, ISBN 978-1-85367-384-9 , pp. 114 (English).

- ↑ Eugène Fieffé, p. XI

- ↑ Filippo Di Comines, p. 272

- ↑ Commentarii della Guerra ..., p. 123

- ^ Francesco Guicciardini: Istoria d'Italia . In: 6 . tape 6 . Classici Italiani, Milan 1803, p. 285 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 5 6

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 53

- ↑ Michael Bittl u. a .: Reflex arc: history and manufacture . Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2009, ISBN 978-3-938921-12-8 , pp. 101 ( online preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Jonathan Shepard: The uses of the Franks in eleventh-century Byzantium . In: Anglo-Norman Studies . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1993, pp. 279 (English).

- ↑ João Vicente Dias: Il confine e oltre: La visione bizantina delle regioni a ridosso della frontiera orientale . In: Porphyra Anno IV Volume = IX . Cambridge University Press, May 2007, pp. 101 (Italian, porphyra.it [PDF]).

- ^ Stradioti. Retrieved May 16, 2019 (Italian).

- ^ Impero Romano d'Oriente: L'esercito romano del X e XI Secolo. Retrieved May 16, 2019 (Italian).

- ↑ Steven Runciman : History of the Crusades . Beck, Munich 1978, p. 62 .

- ^ Charles M. Brand: The Turkish Element in Byzantium, Eleventh-Twelfth Centuries . In: Dumbarton Oaks Papers . tape 43 , 1989, pp. 14 (English).

- ^ Ian Heath: Byzantine Armies AD 1118-1461 . Osprey, Oxford 1995, pp. 23 (English).

- ↑ Maria Gabriella Belgiorno de Stefano: religione libertà di lingua e di: Le comunità albanesi in Italia . Perugia 2015, p. 3 (Italian, riviste.unimi.it [accessed November 3, 2017]).

- ^ A b c d Noel Malcolm: Agents of Empire: Knights, Corsairs, Jesuits and Spies in the Sixteenth Mediterranean World . Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-026278-5 , pp. 15 (English, online version (preview) in Google Book Search). }

- ↑ Stathis Birtachas, p. 136

- ↑ a b c Balkan foreign legions in eighteenth-century Italy, p. 36

- ^ ME Mallett, JR Hale, p. 101.

- ^ ME Mallett, JR Hale, p. 126

- ^ ME Mallett, JR Hale, p. 132.

- ↑ John Seargeant Cyprian Bridge: A History of France from the Death of Louis XI . tape 2 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1924, pp. 263 (English, archive.org ). }

- ↑ Ennio Concina: Le trionfanti armate venete: Le milizie della Serenissima dal XVI al XVIII secolo . Filippi Editore, Venice 1971, p. 29-30 (Italian).

- ↑ Salvatore Bono: I corsari Barbareschi . Edizion RAI Radiotelevisione Italiana, 1964, p. 136 (Italian).

- ↑ JK Hassiotis: La comunità greca di Napoli et i moti insurrezionali nella penisola Balcanica meridional durante la seconda metà del secolo XVI . In: Balkan Studies . tape 10 , no. 2 , 1969, p. 280 (Italian).

- ↑ JK Hassiotis, p. 281

- ↑ Jann Tibbetts: 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time . Alpha Editions, New Delhi 2016, ISBN 978-93-8550566-9 , pp. 575 (English, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Wim Decock ,; Jordan J. Ballor, Michael Germann, Laurent Waelkens: Law and religion: the legal teachings of the Protestant and Catholic Reformations . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-647-55074-9 , pp. 222 (English, online version in the Google book search).

- ↑ Jerónimo Zurita, Guillermo Redondo Veintemillas, Carmen Morte García: Historia del rey don Hernando el Catholico: de las empresas y ligas de Italia . Institución Fernándo el Católico, Saragossa 1998, p. 3 (Spanish, ifc.dpz.es [PDF]).

- ↑ a b c J. K. Hassiotis, p. 282

- ↑ Archivo General de Simancas , E 1011-1016

- ↑ a b J. K. Hassiotis, p. 283

- ↑ JK Hassiotis, p. 284

- ^ Archivo General de Simancas, 1010, num. 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 ff., E 1011, num. 156, 165, 197, 207 ff.

- ^ Archivo General de Simancas, E 1011, num. 208: Letter from the Çamen, written in Himara on August 14, 1532, asking Lomellino to support their revolt; num. 218: Lomellino writes from Lecce on October 16, 1532 to the viceroy Don Pedro de Toledo, Marquis of Villafranca, about his positive mediation for the cause of the Çamen.

- ^ Archivo General de Simancas, E 1016, num. 54: Copy of a letter from the Metropolitan of Koroni (Benedetto) to the Marquis of Tripalda (undated) appealing for help and a promise of the revolt of the inhabitants of Morea.

- ↑ Attanasio Lehasca, p. 7

- ↑ a b Eugène Fieffe, p 77

- ↑ Giuseppe Gullino: Storia della Repubblica Veneta . La Scuola, Brescia 2010, pp. 114 (Italian).

- ^ ME Mallett, JR Hale, p. 55

- ^ ME Mallett, JR Hale, p. 158

- ↑ a b Petta, p. 39

- ^ ME Mallett, JR Hale, p. 56

- ^ ME Mallett, JR Hale, p. 73

- ↑ Filippo Di Comines, p. 276

- ↑ Eugène Fieffé, p. 79.

- ^ Donald M. Nicol: Byzantinium and England in: Balkan Studies . Institute for Balkan Studies, 1974, p. 202 (English, uom.gr ).

- ↑ Jonathan Harris: Shorter Notice. Greek Emigres in the West, 1400-1520. In: English Historical Review (2000). Retrieved November 11, 2017 .

- ^ Gilbert John Millar: The Albanians: Sixteenth-Century Mercenaries Christians from the Ottoman Empire who served in European armies . In: History today . tape 26 . London 1976, p. 470-472 (English).

- ↑ a b Byzantinium and England, p. 202

-

↑ The St. Leonard and St. Dilpe Church is known as the resting place of Teodoro Palaiologos (* 1560 approx. Pesaro (Byzantinium and England, p. 201); father of the brothers Teodoro and Giovanni). Teodoro died in the house of Sir Nicholas Lower in Clifton, Landulph and was buried in St. Leonard and St. Dilpe Church on October 20, 1636 (Byzantinium and England, p. 201). His brass plaque can be seen in the choir. The inscription reads:

HERE LYETH THE BODY OF THEODORO PALEOLOGVS / OF PESARO IN ITALY DESCENDEN FROM YE IMPERIAL / LYNE OF YE LAST CHRISTIAN EMPORERS OF GREECE / BEING THE SONNE OF CAMILO YE SONNE OF PROSPER / THE SONNE OF THEODORO THE Y. SONNE OF IOHN / SONNE OF THOMAS SECOND BROTHER TO COSTANTIN / PALEOLOGVS THE 8TH OF THAT NAME AND LAST OF / YE LYNE YT RAYGNED IN COSTANTINOPLE VNTILL SVB / DEWED BY THE TURKES WHO MARRIED WITH MARY / YE DAUGHTER OF GILLIAM BALLS / OF SOUFFE. & HAD ISSVE 5 CHILDREN THEO / DORO IOHN FERDINANDO MARIA & DOROTHY & DEPARTED THIS LIFE AT CLYTON YE 21YH OF IANVARY 1636.

(This is where the body of Teodoro Paleologus [father] of Pesaro in Italy rests; descendant of the imperial line of Greece's last Christian imperial line He is the son of Camillo, the son of Prosper, the son of Teodoro, the son of Giovanni, the son of Tommaso, the second brother of Konstantin Paleologi, the 8th of that name and the last to reign in Constantinople until for the Turkish conquest; he married Mary, the daughter of William Balls of Hadley in Souffolke Gent and had five children: Teodoro, Giovanni, Ferdinando, Maria and Dorothea and ended this life on January 21st in Clyton [sic!] 1636. ) - ^ John Thomas Towson: A visit to the tomb of Theodoro Paleologus . (English, org.uk [PDF]).

- ^ The Palaeologus Family

- ↑ Jan-Dirk Müller, Hans-Joachim Ziegeler: Maximilians Ruhmeswerk: Arts and Sciences in the Kaiser area . De Gruyter, 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-034403-5 , pp. 354 .

- ↑ Michael Howard: The war in European history: from the Middle Ages to the new wars of the present . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60633-5 , p. 110 ( online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- ^ Wilhelm Edler von Janko : Basta, Georg Graf von . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1875, p. 131 .; according to other sources 1544

- ↑ according to ADB 1612

- ^ Procházka novel : Genealogical handbook of extinct Bohemian gentry families . Neustadt an der Aisch 1973, ISBN 3-7686-5002-2 (master sequence Basta von Hust, pp. 35–37 with further references)

- ↑ Diassorino, Giacomo. Retrieved February 3, 2018 (Italian).

- ↑ Cronaca Cittadina II. Retrieved November 11, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Donald M. Nicol: The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250-1500 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-57623-9 , pp. 104 (English, online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Marullo Tarcaniota, Michele. Retrieved February 3, 2018 (Italian).

- ↑ Stathis Birtachas, p 134