Historical picture of the origin of the Mark Brandenburg

The popular historical image of the origin of the Mark Brandenburg is based on a historical myth , namely a founding myth : The Mark Brandenburg was created after Margrave Albrecht the Bear conquered the Brandenburg in Brandenburg an der Havel as the center of the tribal area of the Slavic Hevellers . The expansion of the Mark under the dynasty of the Ascanian Margraves of Brandenburg was said to have taken place through the influx of German settlers and citizens, who brought about social changes (especially through Christianization and agricultural technical improvements). The article refers exclusively to the founding phase until the Ascanians died out in 1320 .

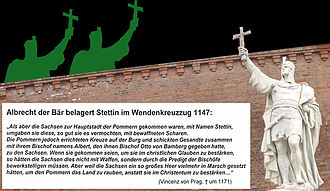

The most popular expression of the founding myth, which was not least politically inspired, is the statue of Albrecht the Bear from the former Siegesallee in Berlin: The armed margrave lifts the cross as a symbol of triumph over the pagan Slavs through Christianization and cultivation; his iron foot rests on the head of a destroyed Slavic god. The “ historical image ” of violent Christianization condensed in this statue is told in more detail in the Schildhorn legend .

The process of the subsequent development of the country and the cultivation of the Slavs was described most popularly by Theodor Fontane in his hikes through the Mark Brandenburg , in the third volume ( Havelland ) published in 1873 , there in the chapter "The Wends and the Colonization of the Mark by the Cistercians " . Since the literary treatment of historical material is most widespread due to its high circulation, non-scientific literature has shaped the popular image of history the most.

This popular view of history, which is correct in its narrowest core, but distorted by national- ethnic perspectives, has been put into perspective by historical-archaeological research results, especially since 1945. The following article explains the most important differences between the general image of history, which is still effective today, and the current scientific image of history (see the origins of the Mark Brandenburg ), based primarily on the research results of Germania Slavica .

General and scientific picture of history

The general image of history and historical awareness are subjectively influenced by personal experiences against the background of social developments (here with regard to the Slavic neighbors e.g. the Polish partitions and their consequences for the eastern parts of Germany up to the two world wars against Slavic states) through the latest findings in historical research .

Until the middle of the 20th century, this was based predominantly on the analysis of written sources , with the result that it was one-sided, since the Slavs between the Elbe and Oder had no written sources of their own before their Christianization. It was only through the strengthening and intensification of archeology that the Slavic part in the development of the Mark Brandenburg became recognizable. The new research direction of medieval archeology emerged, with differentiated knowledge possibilities, especially through dendrochronology and archeobiology . For example, the pollen analysis now enables statements to be made about when and how certain areas were overgrown or used for agriculture. The interdisciplinary cooperation between Medieval Studies and Archeology is therefore essential for the Slavic-German transition period. In this interdisciplinarity, other source groups are included even more strongly and systematically than before: onomastics , settlement geography , numismatics and art history . This also includes cooperation with scientists from neighboring Slavic countries. The Germania Slavica project, which was founded in the 1970s at the Free University in Berlin and has been continued by the GWZO in Leipzig since 1996, points the way for this increasingly qualified research .

The scientific image of history only has a delayed effect on the general image of history. Some myths are almost ineradicable (for example "Brandenburg was originally called Brennabor"; " Berlin-Cölln arose from a fishing village").

Cornerstones of Brandenburg history

The historical image expressed in the statue of Albrecht the Bear and in Fontane's chapter of Wenden did not come about without preconditions. It is not known whether the Schildhorn legend originated in the Middle Ages; It is mentioned in writing for the first time in 1722. For this reason it is also not clear whether and how legend and historiography influenced each other. Up to Fontane, therefore, the two topoi "bloody struggle" and "Christianization" were the focus. A few years before Fontane's Wenden chapter, the connection and authorship of various fragments of medieval sources were discovered. But it was not until the Tractatus de captione urbis Brandenburg by Heinrich von Antwerp was published two years after Fontane's chapter on Wends that it was recognized that the topoi "bloody struggle" and "Christianization" did not have the importance that had previously been assigned to them, and that the founding phase of the Mark by Albrecht was characterized more by similarities than by opposition between Germans and Slavs.

Helmold von Bosau, Heinrich von Antwerp and Pribik Pulkava (Middle Ages)

In his Chronica Slavorum , Helmold von Bosau mainly describes the history of the Obotrites , but he also mentions Albrecht the Bear, both with regard to the Wendenkreuzzug in 1147 and his settlement policy after 1157. Helmold was a rather distant observer in Bosau , the crucial key witness for the history of the Brandenburg region due to the lack of better sources, until 1868 the connection between several long-known chronical fragments was recognized and Heinrich von Antwerp was identified as its author. His treatise had entered the Bohemian Chronicle of the Pribik Pulkava (+ probably 1380) as a "lost Brandenburg chronicle" , whose work was based on information from several older chronicles . Only through the unequivocal assignment of this source did it become apparent:

- the exact identity of Pribislaw-Heinrich von Brandenburg , who until then had been mistaken for the Obotriten prince Pribislaw (old Lübeck) ,

- the alliance with Albrecht the Bear that existed during the entire reign of Prince Heveller Pribislaw (inheritance contract and sponsorship gift Zauche for Albrecht's son Otto ) and

- the fact that both Pribislaw and Jaxa von Köpenick were baptized Christians from birth (like almost all Slavic princes of that time).

So there could be no question of struggle and Christianization in relation to Pribislaw.

Albert Krantz (1448–1517)

Albert Krantz also mentioned Albrecht the Bear several times in his “Description of Wendish History” ( Wandalia , 1519), although his work mainly deals with the Obotrites in the former Billunger Mark . The most important early historians from the Brandenburg region, Bekmann and Gundling , therefore referred to the “famous Scribenten” several times. Its main sources are Adam von Bremen and Helmold von Bosau.

Krantz, a scholar and diplomat in the service of the Hanseatic cities of Hamburg and Lübeck , led the Wendish quarter of the Hanseatic League, which he represented and to which the Brandenburg Hanseatic cities also belonged, back to the Wende. He described her glorious past, e.g. B. citing Adam von Bremen's description of the splendid Slavic trading town of Vineta , regrets that under the conquering Saxons Heinrich the Lion and Albrecht the Bear their names were made “contemptible” (“ slaves ”), and finally says who “ but if our ancestors brought history and deeds right to consciousness ”, he could only regard it as“ an honor that we were born from such people ”.

Krantz was of the opinion that Henry the Lion and Albrecht the Bear would have either slain or expelled the Slavs in the reconquest of the territories lost in the Slav uprising of 983. (The thesis of the "extermination" of the Slavs was first fully refuted in 1960 by Werner Vogel .) According to Krantz, King Heinrich I "made the conquered city of Brandenburg into a Saxon colonies" in 929. (The word colony found its way into the concept of eastern colonization and, at the end of the 19th century, was associated with the idea of Wilhelmine colonial policy, distorting the meaning .)

Johann Christoph Bekmann (1641-1717)

In 1707 Johann Christoph Bekmann received the official commission from the Prussian King Friedrich I to write a history of the Mark Brandenburg. With him the official history of Brandenburg began. Bekmann referred to Krantz; with the chroniclers used by Bekmann, Helmold von Bosau is even more prominent. He quoted Helmold in more detail than Krantz in relation to the events in Brandenburg, but added nothing else that would go beyond Helmold and Krantz. Since he knew only fragments of the source Heinrich von Antwerp, the focus was on “bloody struggle” and “Christianization”. The positive identification of Hanseatic Krantz with the Wende was alien to Märker Bekmann. This shifted the accents.

Baron Jacob von Gundling (1673–1731)

The historian Freiherr Jacob von Gundling also explicitly referred to Krantz as a “famous scribe” , because the Obotrites also ruled the tribal area of the Heveller at times and Albrecht fought with the Obotrites. Gundling was President of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and introduced a systematic evaluation of sources in the Prussian humanities. He was the first to not only collect sources, but also to quote and critically evaluate them (more carefully than Krantz and Bekmann):

“The stories of Marggraf Albrecht the First, who was then called the Bahr, are important, great and remarkable, which deserve to be read from so many scattered writings and documents, put in order, and posterity after so long -Proceedings, now for the first time in the manner of the year books, are presented. "

At the beginning of his work on Albrecht the Bear, he corrected “great errors in the genealogy ” of the Ascanians. In Paragraph 2 he continues: “Since I have now brought the genealogy of the current ancestral table into order, I have also discovered the errors in the history, and have cleared them out of the way.” Then he again turns against individual “erroneous ones “Opinions. Among the 15 points listed, three are of particular importance for the traditional image of history (cited and commented here):

- “It is wrong what one claims of a Marggraf Pribislau, so A. died in 1103. Pribislau was not a Marggraf, but a descendant of the Obotritic princes, who died not A. 1103, but rather A. 1139. ”

Gundling did not recognize that the frequent mentions of Pribislaw in the written sources were about different princes. The Prince of Heveller died in 1150, the Prince of Obotrites after 1156. - "The same Marggraf Albrecht would have got the state of Hohen Zauche for Pathen-Pfenning at the baptism of his son Marggraf Ottens, since [= although] Marggraf Otto was born, because Pribislau was still a hey and enemy of the Christians." But

Pribislaw had assumed the name Heinrich at baptism. Because Gundling only knew the source Heinrich von Antwerp in fragments, without knowledge of the context and the identity of the author. - “They call Pribislau a King of Brandenburg, because [= although] he is only a King. Was a descendant of the Obotrites, and last lived in Brandenburg. ”

Renewed confusion. Indeed, Heinrich von Antwerp called Pribislaw von Brandenburg the king ( rex ). The significance of the king's rank for the Heveller Pribislaw as well as for the ancestors of the Obotrite Pribislaw ( Nakoniden ) is still unclear and controversial.

From the following remarks ("You cannot judge these things if you do not repeat the story of how these countries came to the Obotritic [...] rule") the following points are significant for the traditional image of history (quoted and commented here):

- After the murder of Knud Laward in 1131 "the Brizaner - and Stoderaner -Wenden were torn from the Obotritischen rule and finally became subservient to Marggraf Albrechte, so that the present day Brandenburg got its present form."

In fact Albrecht ruled except the Altmark at his death only the Zauche, the Havelland and parts of the Prignitz. In the development phase of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, the Margraves of Meissen, the Archbishops of Magdeburg, the Bishops of Brandenburg and several smaller noble families, especially in the Prignitz and in the Land of Ruppin , exercised rulership rights until the middle of the 13th century . - “One has news that there was a meeting not far from Potsdam between Marggraf Albrechte and King Prebislaus, in which the latter was beaten, that he drove through the Havel on his horse, as the place not far from Sacro is shown where the Wendish king is shown Prebislaus escaped through the Havel. ”

This is considered to be the oldest written down of a folk tale that became the Schildhornsage. It contributed to the overvaluation of the combat character of the German-Slavic relationship. - “Some have pretended that King Prebitzlau would not have waged any wars with Marggraf Albrechte, but had kept a free distance to the Land of Zaucha and ceded such to Marggraf Albrechte to the Pathen-Pfenning; But this is found differently in the best writings of the same time, which clearly show that the slaves invaded Saxony, which Marggraf Albrecht attacked with great bravery in their lands, and as a result, when he broke in over Eiß in winter, would have defeated them. "

Gundling holds the well-known fragments (“some have given”) from the Leitzkau document collection, written by Heinrich von Antwerpen, countered by the highly regarded source Helmold von Bosau, whereby he mixed up several events: the conquest of Brandenburg in winter 928/929, the Slav uprising in 983 , the battles of Albrecht against Slavs in 1131 in the Havelberg area, the Wendenkreuzzug 1147 and the reconquest of Brandenburg in the summer of 1157. - “Marggraf Albrecht played a major role in these changes [after the death of Emperor Lothar III. 1137], to which the fortune formed in such a way that not only the present-day northern Alt-Marck, along with the lands between the Elbe and Oder, if he acquired it with the Schwerdt as well as in a contract with King Prebitzlauen, calmly in front of him held, but he also found the opportunity to set himself on a higher level through his claims, and to bring the Reichs-Ertz-Cämmerer dignity to his countries . ”

Gundling considered the former Nordmark to be basically identical to the Mark Brandenburg. Amazingly, he mentioned the purchase by contract with Pribislaw. The corresponding fragment of the Heinrich von Antwerp spring must therefore have been known to him. Otto I, son of Albrecht the Bear, was first named as arch chamberlain in 1177. The question of when and how the electoral college, connected with the ore offices, was formed is still unclear and controversial today. - “So that his things [Albrecht's struggle for the office of Duke of Things] would like to remain upright, he got along with Prebislau the Wendish kings, with whom he fought a few years ago in the wars between the Elbe and other occupied lands. While this Obotritic king accepted the Christian religion and allowed himself to be baptized, he again called himself Henrich, so Marggraf Albrecht had no hesitation in associating himself with him, who then overran the Holsteiners and lavishly on hand to completely subdue Marggraf Albrecht. “

Since the predecessor Pribislaw von Brandenburg, who is again confused with the Obotrite prince Pribislaw, the Heveller prince Meinfried , is assumed to be a Christian because of his German name, Pribislaw should have been a Christian since birth. - “It was also around this time [1142] the Obotritic King Prebislaw or Henrich as he was baptized in Brandenburg died, who willingly left everything that he still had to Marggraf Albrechte. […] Marggraf Albrecht got the Marggrafschaff Salzwedel with all accessories, as well as his hereditary lands. At the same time he received the Land of Prignitz and the Land of Barnim and all of its lands with all ducal rights from the Kayser as a land immediately under Reich Freyes, as a consolation and retribution that he had ceded his right to Saxony. […] One finds that at that time he was already administering the Ertz-Cämmerer office […] which things Crantzius, the famous Scribent, probably mentioned, only that he did not know who this Heinrich was, which he was holding in front of a marggrave because he better be able to call the same an expelled King of the Obotrites. ”

At the Reichstag of Frankfurt in 1142 Albrecht lost the office of duke of Saxony. At the same time, Albrecht was first designated as Margrave of Brandenburg by the Reich Chancellery . Gundling suspected it was - probably not wrongly - compensation. It became effective with the death of Pribislav, who did not die in 1142, but only in 1150. If Gundling thought Albrecht owned Prignitz and Barnim as early as 1142, this obviously reflects the fact that in the course of the Wende Crusade in 1147, smaller German aristocratic rule in the Prignitz and in the Land of Ruppin, i.e. in the northern and eastern foothills of the Hevellerland, the Albrecht had skilfully evaded the Wendenkreuzzug. - “When Marggraf Albrecht came to own this considerable land, to which the ducal power was attached at the same time as that power such as Henricus Auceps and the Ottones , now [1143] he intended to establish it on German footing. The same could not trust the Wendish peoples, who were hostile to the Christian religion, as well as to the Germans, because they showed great affection for the Obotritic prince Nicolot, who was still alive in the present-day state of Mecklenburg . […] While the Wends in the Wische could not be trusted, so Marggraf Albrecht decided to occupy the wonderful land of the Wische with German residents, but to distribute the Wends to other places. ”

The Slavic territories conquered by the Ottonians between the Elbe and the Oder were considered Christianized. The abandonment of forced baptism, at the latest in the Slavs' revolt in 983, was considered a betrayal of the faith. From this the topos of the general “betrayal” of the Slavs developed, not only in religious matters. According to Gundling, the Christian enemies in the march sympathized with Niklot, but Helmold reported that he was allied with his neighbor Adolf II von Schauenburg. Niklot shared the rule of the Obotrites with Pribislaw (Alt-Lübeck), who, according to Helmold I, 83, replied to the attempt at conversion of the Bishop of Oldenburg: “If the Duke and you please that we should have the same faith as the Count, please we will then also be granted the rights of the Saxons with regard to goods and taxes; then we would like to become Christians, build churches and pay our tithes. ”So Gundling should have known that the Slavs were neither hostile to Christianity nor to Germans, but only to exploitation by the German princes. - "So [1143] the villages were occupied, provided with churches and courts, which knew how to cultivate the land far better than the Wends [...] because of the Wendish way of that time, the farms and villages were not cultivated, but mostly located in a desert, because the Wends were satisfied with a few and did not particularly seek wealth and wealth. ”

The Germans did indeed introduce improvements, in particular iron plowing and three-field farming . However, this does not mean that the Slavs did not understand anything about agriculture, but mainly lived from hunting, fishing and beekeeping.

Gundling reported about the settlement of the country [1143]:

- Salzwedel, Werben and Arneburg were laid out by the Romans.

- Albrecht founded the Arendsee Monastery in 1160 . (In fact, however, not until 1183 by Otto I.)

- Gransee was said to have been the residence of Pribislaw.

- Gundling correctly reports the oldest name in Brandenburg, citing Widukind von Corvey, as Brennaburg (not as Brennabor .)

- " Berlin was already able [1150], but this city was very small as there are still indications." (The earliest traces of settlement on the Spree islands, however, point to the time around 1170. Late Slavic settlement has not yet been proven.)

- There was a lock on the site of Frankfurt on the Oder . (However, neither written sources nor archaeological traces are verifiable.)

- Keywords for Christianization are: apostasy after the Slav uprising in 983, takeover of Christianity only for the sake of appearance, relapse into darkness, founding of the monasteries Arendsee (1160) and Lehnin (1190), expulsion of suspicious or “worse” Slavic farmers, cessation of the Wendish language Except for certain regions. Conclusion: Albrecht “gradually introduced the Christian religion and did everything so calmly that no complaints arose”.

He reports on the Wenden Crusade in 1148:

- “The Wendish princes were enemies of Christianity because they were forced to pay great tribute and wanted to deprive them of sovereignty. So these peoples got a disgust for the Christian religion. "

- "Marggraf Albrecht was also not in the mood to exterminate or rub up the inhabitants of this country, because he made a lot of money from it."

- "It was very important that Christianity should be introduced in the country, yes, the institution of the Christian religion was a great work to bring so many thousands of people to the Christian faith, of whom the turning points at that time bore the greatest disgust."

- "He could not trust his Revisited Wends in his own country."

He reports on the attack by Jaxas von Köpenick:

“... that Jaxe, a Syriac printz, and a disgruntled noble man, who had the daughter of the former Prince Buthue of King Prebislaw's wife, took up arms and seized the castle at Brandenburg. Who this Jaxe or Jazke was is given ambiguously. Some say that he was a prince in Niederlausitz […] Jaxa was a Silesian count, as a learned man said. […] I will leave these conjectures in their place, but it is certain that he was a Sirbian Printz in Silesia and a great man in the country of Ziaz or Zucha , which country the Lords of Hake and Rochau had in good part and that of them Margraves of Brandenburg received in fiefdom from the same times. "

This is followed by a brief report on the siege of Brandenburg by Albrecht and Archbishop Wichmann of Magdeburg ; it ends with a “handover”, in accordance with a fragment of the Heinrich von Antwerp source. In order to “thank” God for the “happy conquest” of Brandenburg, Albrecht then travels to the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem . After his return, “while he was thinking about the introduction of Christianity in front of his greatest work in his country”, he tried to “provide the churches with income” and “longingly demanded the building of the Stifft Church in Brandenburg ”.

Characteristic of Gundling's work on Albrecht is the sometimes contradicting juxtaposition and coexistence of verifiable facts, inaccuracies and misjudgments that were unavoidable for him due to a lack of other possibilities for knowledge (e.g. through modern interdisciplinary research). He reports both positive and negative aspects of the topoi Slavs and Christianization. However, he repeats again and again the "greatest abhorrence" of the Wends against the Christian religion; He mentions the connection only once: “The Wendish princes were enemies of Christianity because they were forced to pay great tribute and wanted to deprive them of sovereignty. So these peoples got a disgust for the Christian religion. "

Valentin Heinrich Schmidt (1756–1838) and Johann Wilhelm Löbell (1786–1863)

Characteristic of the Krantz, Bekmann and Gundling view of the history of the origins of Brandenburg is the controversy between Schmidt and Löbell , who in 1820 at the age of 34 tried to clarify the history of Brandenburg as a private scholar in Breslau. In 1823 the Berlin high school professor Schmidt (67) replied with Albrecht the Bear, conqueror or heir of the Mark Brandenburg? A historical-critical illumination of the writing of Dr. Löbell on the origin of the Mark Brandenburg :

"Dr. Löbell has in his work entitled: Commentatio de origine Marchiae Brandenburgicae […] the acquisition of the Mark Brandenburg by inheritance, in his opinion, most succinctly proven. The tone that prevails in it reveals a self-confidence that one could not expect from a man whose test of the sources of Brandenburg history one has not yet heard of. "

Schmidt rebukes Löbell's criticism of Philipp Wilhelm Gercken (1722–1791), praises August von Wersebe's work on the “Dutch colonies of northern Germany in the 12th century”, in stark contrast to Löbell, whose work “has long been rejected by connoisseurs as a fable real historical truth "and thus" dares to speak against the most thorough Brandenburg historians ". This fable is the report of Heinrichs von Antwerp, which Schmidt only knows as a "lost Brandenburg chronicle", which was incorporated into the Bohemian Chronicle of the Pribik Pulkava († probably 1380). It is the main source of Löbell's argument.

At the beginning of his reply, Schmidt quotes the corresponding passages from the Bohemian Chronicle in a summary that essentially corresponds to the treatise of Heinrich von Antwerp. But he doubts her reliability because she reports things about which Helmold von Bosau knows nothing. Löbell refers entirely to Helmold, namely to his report on the siege of Demmin, after which the besiegers say: “Isn't the land that we devastate, our country and the people we war against, ours? Why are we our own enemies and destroy our income? "Schmidt replies:" This - man rathe - is supposed to prove that the German princes would rather inherit lands by wills than conquer them. If Helmold got up from the grave, he would be shocked by this inconsistent conclusion. ”For Schmidt it is inconceivable that he would rather inherit through alliance politics instead of waging war against“ a highly bitter, not to be neglected enemy ”. It is also unimaginable that Albrecht received the castle (by inheritance) in 1150: “Albrecht would have to have left again after taking possession of it quickly, and again took the city from Jazko. What a labyrinth of events! "

Schmidt's field of vision never got beyond that of a prorector at the Cöllnisches Gymnasium in Berlin. Soon afterwards, in 1831, Löbell became a full professor at the University of Bonn and is considered to be one of the founders of modern history.

Gercken, Raumer, Riedel, Krabbo and Theodor Fontane (1819–1898)

In addition to Löbell, the modern, source-critical history found its way into the historiography of Brandenburg by Philipp Wilhelm Gercken (1722–1791), Friedrich Ludwig Georg von Raumer (1781–1873), Adolph Friedrich Johann Riedel (1809–1872) and Hermann Krabbo (1875–1928 ). With the exception of Raumer, they worked intensively in archives and therefore drew their knowledge primarily from the most precise critical knowledge of the sources.

However, historical fiction in the form of the migrations through the Margraviate of Brandenburg by Theodor Fontane (1819–1898) was far more effective than historiography . Fontane saw himself not as a historian but as an artist. Still, he had a good knowledge of the sources; in addition, a generally benevolent attitude towards the Wende and a not uncritical attitude towards the church. If one compares today's popular literature and the information in local museums and village church vestibules with Fontane's chapter "The Wends and the Colonization of the Mark by the Cistercians" in the third volume (1873) of his walks through the Mark (1862–1898), its origin from To recognize Fontane. The identification of Heinrich of Antwerp in 1868 did not become known to him in time; it was first published in 1875. His presentation was based essentially on the (insufficient) level of knowledge achieved by Gundling.

Fontane's wanderings saw several new editions during his lifetime; their popularity remains unbroken to this day. Without a doubt, they have shaped the popular image of history the most. Therefore, the critical examination of its representation is the focus of this article.

Johannes Schultze (1881–1976)

Against the background of the efforts of the Polish population in Prussia for national independence, answered by increased attempts at their "Germanization", the "Polish enthusiasm" of 1831, with which the revolutionary attempts of the Poles against the Russian Empire in Prussia had been accompanied. From the middle of the 19th century onwards the tensions in the German-Polish relationship increased, intensified after the First World War and culminated in the extermination policy of the Nazi Reich against Poland and other Slavic neighboring countries, to which millions of Slavic “subhumans” fell victim . An ideological “Ostforschung” on the “German East Settlement” had contributed significantly to this. Many works on the history of Brandenburg from the time between the two world wars can only be understood in this way in their burden of stereotypical prejudices.

Johannes Schultze (1881–1976), through his work in the Prussian Secret State Archives, was able to present a more prejudice-free point of view after the Second World War with his five-volume work Die Mark Brandenburg 1961–1969, which is considered the culmination of his work. Johannes Schultze had been forced into retirement in 1944 because of his opposition to the Nazi Reich. Nevertheless, he also made a remark such as:

“It is not improbable that the Wends, averse to the forms of intensive land use, mostly preferred to feed themselves by dairy farms or as cottagers or residents by services for peasants and knights than to do hard farm labor by clearing; they were not pressed down against their will. "

Schultze must be credited with the fact that archeology only came to better research techniques and more systematic evaluations from the 1950s and that modern interdisciplinary research, in particular in the interaction of medieval studies, archeology, onomatology, settlement geography and art history, was only developed in the 1970s, in particular through the “Germania Slavica” project at the Free University of Berlin, which has been continued since 1996 by the GWZO in Leipzig. The decisive impetus for a new, more appropriate perspective on the German-Slavic relationship in the Middle Ages in the context of the Ostsiedlung came from Walter Schlesinger (1908–1984) and Wolfgang H. Fritze (1916–1991). The interdisciplinary perspective finds its clear expression in the team of authors of the current standard work Brandenburg History (edited by Ingo Materna and Wolfgang Ribbe , 1995). Nevertheless, Schultze's classic Die Mark Brandenburg remains an indispensable working basis, especially in terms of the history of the event.

The popular historical image of the origin of the Mark Brandenburg

The historical image of the emergence of the Mark Brandenburg, which can still be felt today, was formed at the end of the 19th century, after the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. It was literally embodied in the marble statue of Albrecht the Bear in 1898 for the nearby Siegesallee of the Reichstag in Berlin. In no other “picture” is Brandenburg's founding myth so concentrated. Theodor Fontane, who died in the year the statue was inaugurated in 1898, had prepared this “historical picture” with the third volume (1873) of his walks through the Mark (1862–1898), in particular through the chapter “The Wends and the Colonization of the Mark” the Cistercians ”. By Wenden, Fontane understood “the tribe most advanced to the west” west of the Poles, whereby he had the Lutices more in focus than the Obotrites and Pomorans .

Theodor Fontane: Quotes from walks through the Mark Brandenburg

In the following, the ten quotations are dealt with (in the order in which they were mentioned in the “Wenden” chapter) which had the most momentous consequences for the view of history inherited from Fontane.

About the name of Brandenburg

"On the north bank of the Mittelhavel, dominating the entire Havelgau and south of it the 'Zauche', was the old Wendenfeste Brennibor."

In the oldest written mention of the main Heveller castle, this is called Brennaburg . The name Brennabor (several times in Fontane: Brennibor ) is fictitious. In 1677 the Bohemian Jesuit priest Bohuslav Balbinus tried to reconstruct the names of the places in the earlier Slavic settlement areas in order to prove their Slavic origin. The background was the struggle for dominance by the Germans or the Slavs in Bohemia. For ethno-political reasons, the Bohemian Slav replaced the unpopular German -burg with the Slavic, similar-sounding, but not documented -bor .

The Märker did not contradict. The Slavs had long been considered hostile and barbaric (Fontane: "The Wends of that time were like the Poles of today"). A German-sounding place name of the former Slavic fortress Brandenburg (and thus the recognition of their rulers as Christians) would have made them too similar. Current enemies (like the West Prussian separatists in 1873) could be fought all the better, the more different they and their ancestors were.

On the alleged return of the "Germans"

“When, after three, four and five hundred years, the Germans came into contact with this country for the first time 'between the Elbe and the Oder', they found, including a few traces of German life, a completely Slavic d. H. Wendish country. "

Anyone who comes into contact "again" may claim old (territorial) rights. The creation of a historical continuity between the Semnones and the Ottonian Saxons must therefore be viewed critically. Fontane does not name any evidence for the “few traces of (remaining) German life”. Possibly he also meant the numerous names of waters that are of Germanic origin (e.g. Spree , the "spraying"). From the transition period between migrating Germanic peoples and immigrating Slavs, there are otherwise only minor archaeological traces of remaining Germanic peoples, which are then considered to be soon assimilated. The current prevailing opinion in historical research assumes that there has been no significant continuity.

On the significance of the Brandenburg Wends as a warrior

"The Brandenburg Wends [...] had the task of being constantly on the vanguard in the centuries of battles with the invading Germanness, and their importance is rooted in the courage that the Spree and Havel tribes have developed in these battles [...] - Brandenburg […] was conquered and lost nine times, seven times by storm, twice by betrayal […] It was an endlessly spun chain […] German cruelty created Wendish uprisings, and the Wendish uprisings were followed by new defeats, which, forever accompanied the new atrocities of the winner, repeated the old interplay. "

The Brandenburg changed hands not only nine times, but thirteen times: five times after a siege or attack, four times due to treason, once due to inheritance and three times for unknown reasons. Albrecht acquired the Hevellerland as an inheritance through clever alliance policy; He was only compelled to fight through the betrayal of the sympathizers Jaxas . The battle took the form of the usual siege with "blood flowed on all sides" (to an unknown extent), but it ended in a negotiation of surrender, not a "storm".

There was bloodshed, there was atrocity, on both sides, but since the five militant changes of ownership are also opposed to five without a fight, the formulation of the "endlessly spun chain" runs the risk of overemphasizing the aspect of the bloody fight. For the two hundred year old contacts of the Germans and Slavs between the Elbe and the Oder, the idea of incessant carnage is inappropriate. There were also trade links and alliances. No doubt the confrontation prevailed.

For Fontane's point of view, it was crucial that he, who only saw himself as a historian to a limited extent, had only a few sources available, almost exclusively written sources (chronicles, annals). This type of source is less suitable for the representation of processes, but more for the report on events: accession to government and death of rulers, battles, etc. Other things (namely "uneventful" times) are neglected when considering the history of events.

On the "superiority of the Germans"

“The question has often been raised whether the Wends were really on a much lower level than the advancing Germans, and this question has not always been answered with a definite 'yes'. It is very likely that the superiority of the Germans, which will ultimately have to be admitted, was less than has often been asserted on the German side. […] In 1180 the first monks appeared in the march. [...] Where the culture was at home, the culture bringer had their most natural field. "

Fontane's remarks are in a certain contrast: on the one hand, in his opinion, the cultural superiority of the Germans is often overestimated, on the other hand, the Slavs felt at home with the Slavs.

The word “unculture” was taken up by the settlement researcher Werner Gley in 1926, in the period between the emperor's abdication and Hitler's seizure of power , in his work The settlement of the Mittelmark from Slavic immigration to 1624 :

“Instead of the highly developed Germanic culture, which the Semnones had created as a people with a sense of form and beauty, a state of unculture emerged in Slavic times that we can hardly imagine more primitive. The Slavs adapted to the harsh nature of the country without making more serious attempts to improve the poor living conditions through hard work. "

Since the "Wends", nowadays better known as Elbe Slavs in historical studies including archeology , did not know any written sources, the assessment of their material culture is largely dependent on archaeological finds. In 1873, when Fontane wrote the chapter on the Wends, archeology as a science was still in its infancy. Only Flinders Petrie (1853–1942) systematically presented methods and goals of archeology in 1904. However, scientific methods for dating finds and clarifying the origin of their material were not developed until the second half of the 20th century.

Nevertheless, both Fontane and Gley knew of archaeological finds. However, as these finds show, the material everyday culture of the Slavs did not differ in principle from the culture of the migrating Germans. The ceramic produced by the Slavs 500 years after the Great Migration also differs from that of the immigrating Germans essentially only in the forms of decoration: The Slavic ceramic floor stand was more suitable for placing on flat surfaces; the early German spherical bottom pots had a better level of fuel in the hearth fire.

Fontane and Gley could only have derived their disdain for Slavic culture from written sources (written by the Slavs' neighbors). Fontane explicitly mentions the report by the chronicler Adam von Bremen about the Slavic long-distance trading center Jumne (probably Wollin at the mouth of the Oder):

“Beyond the Leuticians, who are called Wilzen by another name , we meet the Oder river, the richest river in the land of the Slavs. At the mouth of the same, where it touches the Scythian waters of the Baltic Sea, the very prestigious city of Jumne offers the barbarians and Greeks who live around it a much visited site. Because great and almost unbelievable things are being brought forward at the price of this city , so I think it would be interesting to include a few things here that deserve a mention. It is really the largest of all cities that Europe includes. Slavs and other nations, Greeks and barbarians dwell in it. For the Saxons arriving there are also allowed to live together with the rest of the population under the same rights, of course only if they do not publicly announce their Christianity as long as they are there. Because all are still caught in the delusion of pagan idolatry. Incidentally, as far as custom and hospitality are concerned, there will be no people to be found who prove themselves to be more honorable and more dedicated. That city, which is rich in the goods of all the nations of the north, possesses every possible comfort and rarity. There you will find the volcanic pot, which the natives call the Greek fire, which Solinus also commemorates. "

The (pagan) Slavs did not yet know any stone building ; it was only adopted by them with the Christianization on the occasion of the building of churches (Poland and Russia, however, already adopted Christianity in 966 and 988 respectively). Herbord reports on the quality of the Slavic wooden temple in Stettin in his vita of the Pomeranian missionary Otto von Bamberg:

“In the city of Stetina, however, there were four continins, but one of these, which was the noblest, was wonderfully ornate and artfully built, had sculptures inside and out that protruded from the walls, pictures of people, birds and animals, so lifelike depicted in their posture that one might have thought they were breathing and alive, and, which must be mentioned very seldom, the colors of the external pictures could not evaporate or be washed off by any snow or rainy weather, that was the art of painters set up. In this building, according to the old custom of their fathers, they brought the treasures and weapons they had won from their enemies and the booty they had gained in sea or land combat, according to the law of paying tithes. They had also set up golden and silver mixing jugs from which the noble and powerful used to divine, feast and drink, so that they could be taken out of a sanctuary on festive days. There they also kept large horns of wild bulls, gilded and adorned with precious stones, suitable for drinking, and horns for blowing, daggers and knives and a lot of valuable implements, rare and beautiful to see what they, as an ornament and in honor of their gods the temple was destroyed, it was decided to give everything to the bishop and the priests. "

Thietmar von Merseburg (IV, 46) mentions a third aspect of culture in his report on the visit of Emperor Otto III . in Poland on the occasion of Gnesen's elevation to the archbishopric in 1000:

"After all questions had been settled, Duke Boleslaw I. Chrobry honored the emperor with rich gifts and - which pleased him most - 300 armored warriors."

Chainmail was the most expensive item of equipment for mounted warriors everywhere, and Boleslaw will certainly not have given away the majority of his horsemanship, so an inventory of at least 1,000 Polish armored riders would be assumed.

Even if one subtracts the usual medieval exaggeration in all three cases, the result is a cultural level of the Slavs that is obviously inappropriately described as “unculture”, even when considering the fact that the living conditions in the country were of course different from those in the big ones Trading cities and at the ruler's court, which Fontane expressly admits.

The use of state-of-the-art technology and procedures was required for large-scale land development with the intention of making a profit: iron reversible plow with wheels, collar tensioning for the horses, three-field management with hoof measurement , water mills and stone construction technology. None of this was used in the Slavic country before 1150, but by no means was it already applied across the board in the Old Kingdom. The new techniques were not yet used in the first early German settlement phase (around 1150–1200), and even after that not everywhere and by everyone; wooden hook plows were in use in the market well into the 19th century. The most favorable localities and corridors for three-field farming with hoof measurement (anger and street villages, Hufengewannfluren) were only developed in the practice of land development east of the Elbe, in which the Slavs were involved; These forms only became systematic from around 1230 east of the Havel (on Teltow and Barnim) under the "town founders" Johann I and Otto III. applied.

The existence of a cultural gap (here: from west to east) is inevitable. It is explained by the fact that renewals take place selectively and not in terms of area simultaneously. Cultural progress spreads from its respective starting point in waves and reaches the one earlier than the other, which depends exclusively on the spatial location of the residential area and not on its individual abilities. The first tools of mankind (stone wedges) were invented in sub-Saharan Africa; the Neolithic revolution started in Asia Minor. The Teutons took over cultural achievements from the Romans; these were passed on from the early Germans to the Slavs half a millennium later. The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation only reached the high cultural level of the previous Roman Empire again at the end of the Middle Ages. The Nazi German arrogance to call the Slavs “sub-humans” because of the cultural gap and to derive the right to systematically exterminate them is therefore without any basis. This disregard, developed in the 19th century, is still the reason for the use of the words “Polacken” and “Polish economy” today.

The Wends as hunters, fishermen and beekeepers

"The main occupations [of the Wends] were of course hunting and fishing , alongside beekeeping ."

To substantiate this claim, Fontane argues that "the same phenomena [...] still exist [1873] in the Slavic plains of Eastern Europe, on the stretches between the Volga and the Urals". These plains are located in the steppe areas of the Eastern Slavs, more than 2000 km away as the crow flies .

The archaeobotany and archaeozoology however, prove that even with the Elbslawen agriculture and animal husbandry were the basis of the economy. The evaluation of animal bones shows that (as was generally the case in Central Europe in the early Middle Ages) pigs dominated as slaughter cattle (cattle were more prominent towards the High Middle Ages). So far no stalls for large cattle have been found in the area of the Elbe Slavs. Ibrahim ibn Jaqub , however, mentions the "wealth of horses" in the Obotrite land. Hunting played only a minor role, with different emphases; where a social upper class formed with changes in the castle structure, the proportion of hunting animal bones in the waste finds increased.

Honey is only mentioned in written sources, next to Ibrahim ibn Jaqub especially in tax registers: honey, mead and wax ; So far, however, there are no archaeological finds such as the remains of mead or logs . However, in the tax registers, grain taxes clearly come first, as the finds of sickles , millstones and silos show.

Ibn Jaqub: The Slavs “inhabit the most fertile and richest in food of the countries. They are engaged in agriculture and maintenance, and in this they are superior to all the peoples of the north. Your goods go to the Rus and Constantinople by land and sea . "

Sebastian Brather (2001): "The fact that the Slavs were largely fishery populations who lived on in the late medieval kietzen misses reality and is a topos (from the 19th century)."

No wrong conclusions can be drawn from the fact that the Slavs were mainly involved in long-distance trade in fur , honey, mead and wax and that these goods, if they are mentioned in the tax registers, indicate a Slavic ethnic group. They do not mean that nothing else was available, otherwise one would have to assume that in Flanders, the economically most advanced region of the High Middle Ages, the grain industry was unknown in view of the extensive grain imports. Fish were of great importance for the religious fasting days. For the princes it was more natural not to demand this from the newcomers recruited for the regular cultivation of grain, but from the resident Slavs.

Alleged character traits of the Wends

“The Wends were brave and hospitable and, as we are convinced, no more wrong or more unfaithful than their conquerors, the Germans; but in one thing they were certainly unequal to them, in that formative force that steadfastly kept an eye on great goals from generation to generation, which has always been the main feature of the Germanic race and which is still the guarantee of their lives. "

According to Fontane, the Poles are: “Quick, clever, tough, amiable, dazzling, chivalrous, passionate, willing to sacrifice, [but] wandering outwardly, […] they lacked the concentric, while they were eccentric in every sense. In addition, respecting individual freedom more than state consolidation - who does not recognize Polish national features in all of this? "Fontane came to the conclusion:" The changes of that time were like the Poles of today. "

He also uses this type of argumentation through equation elsewhere: "The emigrating Semnones are the returning Germans." And: "The main occupations of the Wends were the same as they are now with the Eastern Slavs between the Volga and the Urals." spatial and temporal distance he gives no reason.

That Poland saw itself as a nation state since the year 1000, went through periods of strength and weakness, like all other states, and that Poland as a major European power reached almost as far as the Gulf of Finland and the Black Sea in 1618 and after the eruption the French Revolution was the first country in Europe to give a free constitution ( constitution of May 3, 1791 ) - for Fontane that counts for nothing compared to the "unshakable strength that has always been the main feature of the Germanic race and is still the guarantee of their lives" . Apparently Poland was responsible for the three partitions (from which Prussia always benefited as well) through its "higher respect for individual freedom", which Fontane criticized. So it can be no wonder that the area of the southern Lutizen fell into Albrecht's hands.

Albrecht as the alleged founder of the monastery

“But to the churches and castles [...] he [Albrecht the Bear] added something new, a third, the union of castle and church - the monasteries. Monks were called into the country, especially the Cistercians . "

Albrecht did not found a single monastery. Up to his death in 1170 there were only two monasteries, both in the Altmark ( Benedictine nunneries , of which Hillersleben was founded in the 10th century). It was not until his son Otto founded an Ascanic monastery with Lehnin in 1180 , the first east of the Elbe, the first male monastery and the first Cistercian monastery. That was not a fundamental change, because four years later he founded Arendsee , again a Benedictine monastery in the Altmark. All Cistercian monasteries came into being after Albrecht's death: Zinna (1171 by the Archbishop of Magdeburg ), Dobrilugk (1184 by the Wettins ), Neuzelle (1268 by the Wettins). Fontane lists a total of 23 Cistercian monasteries for the period up to 1300; ten of them are nunneries; only two thirds are Ascanian foundations (16 out of 23).

Monasteries are nothing new in and of themselves, and the fact that the oldest monasteries in the Ascanian area are women's monasteries shows that they were not understood as a kind of castles, but as a supply center for noble daughters.

What is new to the east of the Elbe is that the monasteries do not form “monastery landscapes” as in the Altreich, but represent islands. Until the foundation of the Mariensee Monastery in 1258, which was moved to Chorin in 1273 , Lehnin (1180) is the only Cistercian monastery in the heart of the Mark; Marienfließ (Nonnen, 1230) and Dranse (1233) are in the Prignitz , Zehdenick (Nonnen, 1249) in the Uckermark and (Alt-) Friedland (Nonnen, around 1250) on the edge of the Oderbruch .

This factual representation of Fontane results in two serious misjudgments: the importance of the Cistercian order and - through the image of the "castle" - the link between the church and military tasks.

The Cistercians as bringer of culture

"The monks of Cisterz had penetrated deep into pagan lands with the cross in their left hand, ax and spade in their right hand, teaching and farming, educating and sanctifying."

Above all in the entrance halls of the village churches there are still not infrequently written tablets and leaflets that attribute a leading role to the Cistercians in the agricultural development of the Mark (also in the construction of the village churches, see below). Example:

“It was not until the 12th century that the huge colonization movement began in our homeland. The orders of knights and monks began their extensive work, which always revolved around two goals: evangelism and civilization . They preached the Gospel , built more and more solid bases and showed the Wends how to take up the fight against sand and water and how to get rich income from the barren, sandy soils of the Brandenburg region. "

At the time of its emergence in the 19th century, this view strengthened the role of the church in the alliance of “throne and altar” to defend the monarchy and referred to the original ideal of the order of the Cistercians: retreat into solitude and nourishment by one's own work. As the Cistercian research has shown in detail in the meantime, the importance of the order is wrongly assessed:

“Based on the references to the establishment of monasteries in the wilderness, which were widespread in the religious tradition, the doctrine of the outstanding achievements of the Cistercians in the cultivation of undeveloped or poorly developed areas emerged in the 19th century. This was linked, especially in German research, to the view of the cultural backwardness of all Slavic regions in the time before the onset of the so-called German colonization of the East in the high Middle Ages. Crowds of monks and conversations, as pioneers of civilization and Germanness, would have settled in the Slavic wastelands and, in collaboration with the summoned German farmers, in the 12th and 13th centuries east of the Elbe, 'terras desertas' (desert lands) flourished Transformed cultural landscapes. Even if one had to infer from the sources that the Cistercians were given existing villages here, Franz Winter , the author of the three-volume work on the 'Cistercians of northeastern Germany' published between 1869 and 1871, held fast to the fact that the 'actual cultivation' of the countries inhabited only by the incompetent Slavs or 'by poor and lazy Poles' had to be done by the Cistercians. "

The original order ideal changed over the centuries. The economic successes of the Cistercians through effective agriculture led to profits with which they bought up villages that had already been developed, which was forbidden according to the original religious ideal, but was increasingly tolerated by the annual general chapters of the Cistercians. Three economic activities of the monks exceeded the profits from agriculture: the construction and operation of water mills , the operation of markets and jugs, and lending from the economic profits .

The interest taking was the most obvious violation of the original order ideal, but can be proven by numerous accounting books. Towards the end of the High Middle Ages at the latest, the Lehnin monastery could be regarded as the Brandenburg “Landesinvestitionsbank”, from which the towns, the nobility and the margravial court took loans. This was undoubtedly of great importance for the rise of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, but it differs very clearly from the type of alleged merit through hard farm labor.

So far, their water supply systems (including the construction of dams and bridges) for the monasteries, which in addition to the drinking water supply and hygiene, above all allowed the operation of water mills, which were the "power stations" of the Middle Ages, not only for grinding, have received insufficient recognition but also for saws and hammer mills thanks to camshafts .

On the role of the Cistercians in building the village churches

“Everywhere in the Teltow and Barnim villages, in the Ukermark and in the Ruppinschen, old stone churches rise up with a short tower and small low windows, wherever the east wall has a choir-like extension, a neatly finished sacristy or the roof as a result of a later extension right-angled bend, shows a kink, everywhere we can be sure - Cistercians were here, Cistercians built here and prepared the first place for culture and Christianity. "

Even more than the services of the Cistercians for the (agricultural) development of the country, their services for the building of the village churches in the Mark region are overestimated. So one finds the claim of local research about the village church Marienfelde : "The current stone church was built by the Bauhütte Kloster Zinna, as the first known construction of this Bauhütte after the completion of the monastery church in Zinna, which was consecrated in 1226."

This stubbornly defended claim is unfounded. In general, there is no written evidence of the participation of the Cistercians in the building of village churches in Brandenburg , neither in Marienfelde nor anywhere else. There is also no written evidence of the existence of a construction hut belonging to the Zinna monastery in the Mark, its existence is merely assumed. There is no source evidence for any Cistercian construction site anywhere in Europe. The claim for Marienfelde is justified as follows:

- The Zinna monastery church is the highest quality block stone building in (today's) Mark Brandenburg and therefore a general model for all carefully square stone churches. Zinna in the medieval country of Jüterbog, which belonged to the ore monastery of Magdeburg , did not join Brandenburg-Prussia until 1815 . The Brandenburg Cistercian monastery Lehnin, on the other hand, is a brick building.

- Marienfelde is relatively close to Zinna. The assertion of Cistercian participation in the construction of the village church extends up to the Uckermark. However, even Marienfelde on the Teltow is closer to Lehnin than to Zinna.

Speaking against the claim of the Marienfeld local research:

- Carefully square stone churches as possible models for Marienfelde exist in the Altmark well before 1200 (dendrodata from 1130), long before the Cistercians also settled there.

- The claim “first? better known? Construction of the Bauhütte? after the completion of the monastery church in Zinna, consecrated in 1226 “is based on two false assumptions. The latest research, which is based on scientific methods, not on legendary traditions, shows that Zinna - independent of the ( altar ) consecration in 1226 - was only completed around 1230 and that Marienfelde was not built "around 1220" because it was built by a second used roof beam, dendrodated to 1230, has become extremely unlikely.

- In today's Brandenburg there are around 850 village churches of medieval origin, around 400 of them from the Ascanian founding period. Even if the Cistercians had only been involved in half of them, this would have clearly overwhelmed the Cistercians, who had difficulty building their own monastery church: in 1179 the Zinna abbot was slain by (Christian) Pomerania and the surrounding area was devastated. In 1195 the general chapter condemns the abbot for sending monks to Jüterbog to beg. The construction date of 1226 does not refer to the consecration, but, as building research has shown, to the restart of construction work. Then follows a series of bad harvests, so that in 1230 the General Chapter had to deliberate about a possible move "of the Abbey of Zinna, of which it is said that it cannot be kept as an abbey". To solve the problem, the monastery is given land on the Barnim around Rüdersdorf , but the quality of the village churches is very different. - Only Lehnin (foundation 1180, start of construction 1183) is economically successful, but not through own work, but through rich donations from already developed villages to the monastery of the Ascanian princely house. The second Ascanian burial place in Mariensee was only founded seventy years later, around 1255; However, in 1273 it had to be moved to Chorin due to poor soil conditions.

- The assertion of Cistercian authorship is based on the idea that there are certain building types specific to the builder (e.g. “Ascanic architecture”). In total there are only a dozen different basic types, but none of them have any specific reference to certain major builders. The villages belonging to the Zinna monastery property around Rüdersdorf had village churches of very different quality. Parallel example: The three Templar villages around Tempelhof , spatially and temporally developed in close connection, did not even have a uniform village form; Structural details of their village churches show that they cannot come from the same "construction hut".

Almost all of the sacristy houses in the village churches, which Fontane also attributes to the Cistercians, were only added to the churches at a later date, mostly after the Ascanian period.

On the interpretation of the village churches as fortified churches

“The hill church, which they called up several times, was an old stone building from the first Christian era, from the days of colonization of the Cistercians; This was indicated by the neatly hewn stones, the choir niche and, above all, the small, high arched windows, which gave this church, like all pre-Gothic places of worship in the march, the character of a castle. [...] From the days when the Ascanians fought out their regularly recurring feuds with the Pomeranian dukes [...] "

Fontane never used the term “ fortified church ”, but for him monasteries and village churches have a castle-like character, and for him the meaning of the Wends is rooted in their courage to fight (see above). Regarding the "regularly recurring feuds [of the Ascanians] with the Pomeranian dukes", especially in the popular histories regarding the violent death of the Zinna abbot in 1179, the equation is almost always assumed: Pomerania = Slavs = pagans. The Pomeranians, however, had been proselytized by Otto von Bamberg since 1128 (see below), and their campaign was initiated by Heinrich the Lion in the fight against his Saxon opponents.

For the period from the final occupation of Brandenburg in 1157 to the conclusion of the Teltow War 1239–1245, the following combat operations can be proven in the Mark:

- 1178–80: Trains of the (Christian) dukes of Pomerania (through the Berlin area) to the (Wettin) Lausitz and the (Magdeburg) Land of Jüterbog. The Pomeranians are allies of Henry the Lion, from whom Emperor Barbarossa wants to withdraw the Saxon ducal office.

- Around 1180, the Wettin margrave Dietrich von der Lausitz destroyed the Köpenick castle wall of the (Christian) Slavic prince Jaxa , who was probably allied with the (Christian) Pomeranian dukes.

- 1187: Margrave Otto II of Brandenburg mentions that the frequent threat to the Brandenburg Church from pagan attacks was still ongoing at this time.

- 1195–1199: A fleet of (Christian) Danes drives up the Oder against the Ascanians, in whose area (probably in Barnim) a fight takes place.

- 1200–1215: Campaigns by the (Christian) dukes of Pomerania against the Ascanians for possession of Barnim.

- Around 1200 Köpenick and the castle near Mittenwalde were destroyed during an advance by the Wettins against the Lebus region .

- In 1209 the Wettin margrave Konrad II moves again via Köpenick on a train against Lebus.

- In 1210 the Ascanian Margrave Albrecht II claimed to the Pope that he needed parts of certain tithe income to defend against Slavic attacks on the Barnim (cf. on 1234).

- In 1225, Landgrave Ludwig of Thuringia, as guardian of the Meissen and Lusatian margraves, probably traveled via Köpenick on a train against Lebus.

- Around 1230 the Brandenburg-Pomeranian disputes over the Barnim finally came to an end.

- 1234: The Bishop of Brandenburg argues with the Pope in the Brandenburg tithe dispute that, contrary to the assertions of the Ascanian margraves (cf. on 1210), the Barnim was by no means snatched from pagan lords, but rather Christians, whose present incursions are not directed against Christianity, but wanted to withdraw the area from the empire. The Pope then comes to the conclusion that in the whole country there really were no more pagans, but only Christians; the margrave wanted to cheat the church.

- 1239–1245: Teltow War (also called Meißnische feud) between the margraves of Brandenburg and Meißen ; the Archbishop of Magdeburg is also involved. In 1240 Köpenick is destroyed; in the course of the fighting also Mittenwalde and Strausberg .

- It was not until 1254 that Strausberg, which like Berlin / Cölln had no castle before, received city walls; political developments make building a castle unnecessary.

In view of these phenomena, the prevailing opinion of historians denies the "castle lines" and "stage roads" repeatedly stated by older research to protect against the (pagan) Slavs. Johannes Schultze (1961/62) already doubted:

“Not quite in line with Margrave Otto II's references in 1187 to the liveliness of the pagans and the hardships they suffered, however, is the fact that the St. Gotthard Church in the Brandenburg suburb of Parduin has not been destroyed since the time of the last Heveller princes Nor is the Marienkirche (first mentioned in 1166) built on the site of the Triglaw shrine on the Harlungerberg […] In this context, the fact that there is neither a proven Christian martyrdom nor a saint of the Catholic Church in the area of the Mark Brandenburg is noteworthy Has."

The actual dangerous situation is exemplified by the detailed description of the Teltow War: In this feud, in which the archbishop, bishop and margrave were personally injured and imprisoned, massive stone buildings were undoubtedly of great use, if not against pagan ones Slavs, but against their Christian neighbors. The square stone churches claimed as "fortified churches" were not built on the Teltow and Barnim before 1230, further east even later, so actually only after the end of the Teltow War, which ended the rival battles of the (Christian) feudal powers over the Central Mark.

The fortified church is defined as “a fortified church for defensive purposes, sometimes built like a castle with a strong wall or churchyard wall, a fixed gate tower, a bell tower similar to a bell tower, an upper floor similar to a battlement. W. served as a refuge for the population in times of war. In the north they were built as circular systems (e.g. on Bornholm), in Thuringia, southern Germany and Transylvania they were designed as fortified churches. ”Not explicitly mentioned, but in fortified churches there are often storehouses and wells or cisterns, ditch systems and sometimes even portcullis and drawbridges .

All of these facilities are not available in the Brandenburg square stone village churches. Your masonry is less than a meter thick; in the tower area up to two meters are reached. There are also slot windows, sometimes wooden locking beams for the portals ("weir beams"), and rarely internal stairs. But the slit windows lack the expansion towards the inside so that they can be used as loopholes, and there is also a lack of standing space for possible shooters. The towers are not locked opposite the nave; often the apse windows are so low that it is possible to penetrate the nave without a ladder. Since there is no water supply, the village churches can only serve as shelters for a short time. They are not (church) castles.

In representations since around 1900, the impression has been given that the field stone churches were a kind of military building program that, with the progress of "Eastern colonization", was pushed forward eastward against hostile Slavs. This fits the idea of a military "stage road" which allegedly ran across the Barnim from Spandau or Berlin via Bernau to Oderberg, which in turn led to the erroneous claim of an "Ascanian defensive tower" as the origin of the Ladeburg village church .

The following quote shows that the idea of "Eastern colonization" arose using the example of Wilhelmine colonial policy :

"At the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, the Teltow was still a Slavic area [...] So gradually the German invaded the country. Of course he had to be on his guard and, as we did with our African colonies, secure himself militarily. [...] Therefore, a building in the middle of the village was also used for military purposes: the church. "

But even in the History of the Prussian States by Johann Friedrich Reitemeier , published between 1801 and 1805 , the medieval eastern settlement was compared with the "colonization and immigration of Europeans to North America". This was combined with the idea of expanding the United States through a constant advance of the Western Frontier , secured by forts . In fact, the German settlement in the east was more of a selective infiltration and mixing.

Conclusion

Fontane's wanderings can give the impression that the origin and development of the Mark Brandenburg in the century between 1150 and 1250 was the sole or predominant work of the Ascanians and the Cistercians. The settlement activity of smaller aristocratic families in the Brandenburg areas, which have been in evidence since 1147 and which frame the Ascanian heartlands of Zauche, Havelland, Teltow and Barnim, i.e. in the Prignitz and Uckermark, in Ruppin, Lebus and Beeskow-Storkow, from Magdeburg's Jüterbog, is insufficiently appreciated -Luckenwalde and not to mention the Wettin Lower Lusatia. The development of the Uckermark and Lebus was initiated by the dukes of Pomerania and Silesia.

All of the above commissioned locators with the development of the country, for which they in turn recruited farmers from Northern Germany to Flanders . It is to the merit of the Ascanians to have bundled these remarkable and indispensable beginnings in the second half of the 13th century, and to the merit of the Cistercians, who managed the farmland, which was developed under other guidance and then acquired by donation or purchase, profitably for the benefit of the country to have.

All of this has to be taken into account when looking at the classic historical image seems to focus everything on the person of Albrecht the Bear. The monument situation for the emergence of Berlin in front of the Berlin Nikolaikirche is more balanced : the seal of the city founders Johann I and Otto III. are accompanied by the coat of arms of the Berlin medieval guilds and guilds ( Viergewerke ).

Kaiser Wilhelm II and Albrecht the Bear

The statue of Albrecht the Bear in Siegesallee

Based on the historical image made popular by Fontane's hikes , Kaiser Wilhelm II developed the inclusion of the Ascanian margraves in the succession of rulers that led to the establishment of the German Empire in 1871 for Siegesallee . Since the represented succession of rulers began in the High Middle Ages of the 12th century, the Wilhelmine Empire wanted to be seen as the restoration of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. This new empire was to give Germany world renown, among other things through the establishment of colonies.

Fontane saw himself more as a man of letters than as a historian. In the case of Wilhelm II, however, political intent is also to be assumed, because images of history are the subject of historical politics (see also national history ). The statue of Albrecht the Bear was intended to convey three messages, the most important of which is unmistakably:

- Through Albrecht the Bear, the Christian cross triumphed over the Slavic idols. This is in the foreground of his merits.

- He is the creator of the Mark Brandenburg.

- The position of the statue of Albrecht at the beginning of Siegesallee says: Ultimately, the Wilhelmine German Empire emerged from the Mark Brandenburg.

The following political intentions can be seen from the Siegesallee beginning with Albrecht:

- The Hohenzollern dynasty emphasized its claim to leadership in the German Empire over the older dynasties of the Welfs , Wettins , Wittelsbachers , Anhaltins and Mecklenburgers , who were forced into the Prussian-dominated empire by the Wars of Unification of 1864–1871. In order to appear just as old, Albrecht and the Ascanians were captured and presented as "Pre-Hohenzollern".

- The Christian cross of Albrecht underlined the alliance of throne and altar, which was needed to justify the royal claim to rule. This claim was derived from the divine right . The growing labor movement, on the other hand, demanded legitimation of rule through elections and was therefore opposed with the socialist laws. The divine cross was stretched out towards her.

- The controversial German colonial policy of Wilhelm II, which began late with the German Empire, took on the appearance of an old tradition through the formation of the term "Eastern colonization" for Albrecht the Bear's conquest. The description of the Ascanian settlement policy as colonization is not necessarily given, especially not in the sense of the 19th century.

- The armor of Albrecht ( chain armor ) indicated that disputed territorial issues between Germans and Slavs could always only be resolved by force.

At the latest with the establishment of the German Empire, the Poles demanded ever stronger national unification for themselves, namely the restoration of Poland, which had lost its statehood through the three Polish partitions. For the region around Poznan , in particular, it was disputed whether it was more German or Slavic-Polish from a historical perspective.

Fontane was paternal benevolent and indulgent towards the "Wends". However, since he had used the word “unculture”, the key words he provided to the image of “fighting idolaters ” could be sharpened. While Wilhelm II was only concerned with repelling efforts by the Polish nation-state, the feeling that Germany was threatened by these demands after the First World War increased when armed conflicts broke out between Poland and Germany during the consolidation phase of the restored Polish state. For their part, the Poles were overrun by the Red Army in the Polish-Soviet War . This “Bolshevik danger” from the east, not least represented by the KPD in the German Reichstag, increased the fear of possible aggression by the Slavic neighboring states. The stereotype of the vicious Slavs, the "danger from the east", solidified.

To the Christianization of the Slavs

The Stettiners had been Christianized since 1128.

Albrecht's contemporaries, the Heveller prince Pribislaw-Heinrich and the Sprewanen prince Jaxa, were both already baptized. Most of the predecessors of the Heveller prince were probably also Christians (see above); Jaxa came from Poland, which had been Christianized since 966 . At least the upper classes of all neighboring Slavic countries had been baptized for a long time: the Bohemians also since the 10th century, the Obotrites since the 11th century, the Pomerania since 1128 (see the emergence of the Mark Brandenburg # Christianization ).

Christianity was permanently rejected and opposed only by the Lutizen; only they could have been the object of any Christianization attempts by Albrecht. However, only the southern half of the Lutizen area came to the Mark Brandenburg; In these sub-areas of all places (Land Ruppin, Land Löwenberg ), however, the rule did not lie with Albrecht and his successors, but with the Counts of Lindow-Ruppin and Bishops of Brandenburg.

Vincenz von Prague reported that Albrecht's attempts at Christianization were pointless about the Wendenkreuzzug in 1147:

“But when the Saxons came to the capital of Pomerania, named Stettin, they surrounded it as best they could with armed bands. The Pomeranians, however, erected crosses on the castle and sent envoys to the Saxons together with their bishop named Albert , whom Bishop Otto von Bamberg had given them, to inquire about the reason why they would have appeared with such army. If they came to strengthen their Christian faith, the Saxons had to do this not with weapons, but through the sermons of the bishops, declared the Pomeranian ambassadors. But because the Saxons would have set such a large army on the march to rob the Pomeranians of the land instead of strengthening them in Christianity, the bishops of Saxony, when they heard this, met with the Pomeranian Prince Ratibor and Bishop Albert advise how peace can be made. "

In the best source about the Christianization of the Slavs (Helmold von Bosau) the Wagrier prince Pribislaw says to the bishop of Oldenburg :

"If it seems right to Duke Heinrich the Lion and you that we are of one faith with Count Adolf II of Holstein, then we should also be given the rights of the Saxons to goods and income, then we will gladly be Christians, Build churches and pay our tithe. "

As a result of the missionary attempts of Saxon princes, Helmold (I, 68) says about Heinrich the Lion: "On the various campaigns that he undertook into the Slavic land, Christianity was not mentioned at all, only money."

There is no reason to assume that Albrecht the Bear acted significantly differently from Henry the Lion in this regard. It goes without saying that the quoted sources were known to Prussian historians at least since Niebuhr and Ranke . However, the final decision on the design of the statues on Siegesallee rests with Wilhelm II.

Colonization as an alleged benefit

Albrecht, who was built in 1898, symbolically stretches the cross as if he were bringing the torch of freedom , the light of civilization . Taking possession of foreign territories and ruling over the local peoples required justification in the age of colonialism. There was a cultural gap to be overcome. The way in which this cultural divide was to be overcome was decided by the colonizer; he presented this as an act of generosity. The naval officer Francis Garnier (1839–1873) said at the time on the occasion of the colonization of French Indochina :

“This generous nation of France [...] has received from Providence a far greater mandate than the expansion of its trade and pursuit of profit, namely to liberate the races and peoples that are still slaves of stupidity and oppression, to give them light and freedom call."

This well-meaning paternalism of the "stupid and oppressed races and peoples" was maintained by the League of Nations after the First World War :

“The following principles apply to the colonies and areas [...] inhabited by peoples who are not yet able to govern themselves under the particularly difficult conditions of today's world [1919]: Welfare and development of these peoples constitute a sacred task of civilization, and it is imperative that guarantees for the fulfillment of this task be included in the present statutes. "