History of Slovakia

The history of Slovakia begins with the settlement of Germanic and Celtic peoples. At the beginning of our era, Roman garrisons temporarily invaded areas north of the Danube and set up fortified camps and settlements in what is now Slovakian territory. The Huns threatened southern and western Europe in the 5th century, while the Slavs invaded Slovakia during the Germanic western migration . The Avars came here later. From an uprising of the Western Slavs against the Avars, the first written Slavic state structure, the Samos Empire , emerged. Around 800 a Christian principality was established around today's Nitra, which then became part of the Great Moravian Empire around 830 . The sphere of influence of Greater Moravia extended as far as Cracow, Meißen and later Hungary. In 906, however, it fell victim to the invading Hungarians . After the fall of the Great Moravian Empire, the Magyars gradually conquered today's Slovakia. After a brief conquest by Poland (1001–1030), the entire area returned under Hungarian rule. A large loss of population occurred after the Mongol invasion in 1241, which also devastated the landscape. Since the 13th century, large numbers of Germans were settled there, and Jews in the 14th century .

After the defeat of the Hungarian army at Mohács against the Ottomans in 1526, Slovakia fell to the Habsburgs by inheritance . During the period of Turkish expansion, Slovakia, as part of Royal Hungary, remained the only non-Turkish part of Hungary for a long time and thus gained military importance. Pressburg , today's Bratislava, became the capital and coronation city in 1536 and was able to maintain this status until 1848. In 1787 tried Anton Bernolák , with the codification of the Slovak language to create a unified Slovak language for the first time. In Slovakia, the opposition to the Hungarian upper class and the dissatisfaction with the implementation of Hungarian as the official and school language became particularly noticeable. In 1848 the national movement presented a political and constitutional program that also included the split from the Habsburgs. This culminated in the unsuccessful September uprising in Slovakia . It was not until the First World War that the Slovaks had the chance to gain autonomy.

On May 31, 1918, groups of Czechs and Slovaks living in exile in the USA reached an agreement in the Pittsburgh Agreement on cooperation in building a future common state. Czechoslovakia was founded on October 28, 1918 . The international recognition of the new state took place in the Treaty of Saint-Germain (dissolution of the Austrian multi-ethnic state) and the Peace of Trianon (separation of Slovakia from Hungary). However, 23% Germans and 5% Hungarians as well as some minorities also lived in the newly founded state. The German population, which until then had belonged to the ruling nationality , was now suppressed. In Slovakia there was growing dissatisfaction with the guaranteed but not granted autonomy. Thus, with the Slovak People's Party, a Slovak autonomy movement came into being. In 1939, under pressure from the German Reich, Slovakia was declared the First Slovak Republic to be independent and was given an autonomous government under the leader of the autonomists, Jozef Tiso . Slovakia had only a small amount of political sovereignty. The opponents of President Tiso initiated the Slovak National Uprising in 1944, but it was suppressed. Slovakia was occupied by Soviet troops in 1945 and the Czechoslovak Republic was restored, with the exception of Carpathian-Ukraine, which had ceded to the Soviet Union . The German population, including large parts of the Carpathian Germans and the Zipser , was expelled. In 1948 the Communist Party took power. The federalism guaranteed by the constitution to the Slovaks was thus definitely lost. After the Velvet Revolution , it was transformed into a federal republic within the ČSFR in the spring of 1990 . The ČSFR only existed for a short time because of the Slovaks' aspirations for autonomy. The Slovak Prime Minister, Vladimír Mečiar, pushed Slovakia's drive for autonomy. Negotiations with the Czech Prime Minister Václav Klaus to form a confederation failed.

On July 17, 1992 the Slovak parliament proclaimed independence from the CSFR. On January 1, 1993, Slovakia became a sovereign state. Accession negotiations with the EU begin on February 15, 2000. Under the Dzurinda government , the country is on a consolidation course. Slovakia joins NATO on March 29, 2004 . On May 1, 2004 it becomes a member state of the European Union . Further milestones for Slovakia on the way to European integration are the accession to the Schengen Agreement , which came into effect on December 21, 2007, and the introduction of the euro on January 1, 2009.

Period of the Great Migration (380-568) and the First Slavs (around 471-658)

In northern Slovakia there existed between 360 and 440 the northern Carpathian group of the Przeworsk culture , which was probably identical in central Slovakia with the Vandals and in the east with the Sarmatians .

In southern Slovakia, in 375, the last of the numerous Roman-Quadic Wars that had raged on the territory of Slovakia for centuries was ended by a Roman invasion and a subsequent peace agreement. After that year, Roman legions never set foot on Slovak soil again. Most of the people living in southern Slovakia Quaden left after about 400 years along with the (since 165 in eastern Slovakia and since 360 based in northern Slovakia) Vandals this area. The Jazygens lived in southern eastern Slovakia (1st century to 380). Between 380 and 455, the Huns lived in what is now western Hungary and southern Slovakia. The Skiren were proven in Slovakia established, certain groups of the Goths , but their exact assignment is not possible. The Gepids lived in the south eastern Slovakia in the period from 455 to 567. The Heruli were in western Slovakia and South Moravia resident in the period 471-526. The Lombards lived from around 500 to 540 on the March (up to and including Bratislava ).

After 471, the first major wave of Slavs came to northern Slovakia from the north - the ancestors of today's state people of Slovakia. The Slavs spread throughout Slovakia from the north and south in the first half of the 6th century and live here to this day.

The Avars settled in what is now Hungary after 568. After 595 they began to subjugate the neighboring Slavs in southern Slovakia, which in 623 led to the creation of the Empire of Samo .

658 to 833

The settlements from the time of the kingdom of Samo after his death in 658 are partly identical with those from the time of the later Neutra Principality and Moravian Principality (see there). The Avars chased away by Samo returned to southern Slovakia and evidently lived there in symbiosis with the Slavs.

In the second half of the 8th century, the whole of Slovakia and neighboring Moravia reached a turning point in terms of civilization. Numerous fortresses and two principalities emerged there : the Moravian Principality (originally in today's south-eastern Moravia and in the neighboring Slovak regions) and the Neutra Principality (originally in western and central Slovakia and parts of northern Hungary). The former is mentioned for the first time in 822, its center was called "Morava" (Eng. Moravia, perhaps today's Mikulčice ), Mojmir I ruled as the prince from around 830. The center of the second was called Nitrava (later Nitra , Eng. Neutra ), es is mentioned for the first time in 828, Pribina (Privina) ruled as prince from around 825 . The two principalities emerged in connection with the struggle of the Slavs and the Frankish Empire against the Avars, who are still settling in present-day Hungary and the neighboring areas. The Avars were defeated in this war and disappeared at the beginning of the 9th century. The last Avars lived in the area of today's Slovakia in the area of today's Komárno .

At the beginning of the 9th century, the Neutra principality expanded, so that it probably also included today's western Carpathian Ukraine . The largest centers were Nitra, Bratislava (including today's districts Devín , Devínska Nová Ves), Pobedim , Brekov , Zemplín and Feldebrő in today's Hungary. At the same time, the victory over the Avars enabled a new wave of Christianization in Slovakia and Moravia. In 828 the first known Christian church of the Western and Eastern Slavs was consecrated in Nitra, the seat of Prince Pribina. A year later, Ludwig the German assigned the area of today's Slovakia and today's Moravia to the diocese of Passau as a Christianization area. However, some of these areas had already been Christianized beforehand.

Great Moravia (833–907)

In 833, Prince Mojmir I, who ruled the Moravian Principality, drove his neighbor Pribina out of the Principality of Neutra and united both principalities. Great Moravia came into being. Pribina became the prince of the Balaton Principality in the southwest of today's Hungary. The Neutra principality became a feudal principality within Greater Moravia, in which the heir to the throne of the ruling Mojmiriden family ruled as princes. The Great Moravian mission of the Slav apostles Cyril and Methodius was important for Slavic (and Slovak) literature and culture . Attacks by the then nomadic Hungarians then destroyed the central power of Great Moravia in 907 after the three battles of Pressburg .

The Slavic sources at that time refer to the inhabitants of Greater Moravia as slověne (Slavs; at that time about slovenian (very open e) or slovenian (middle e) pronounced). This was most likely the original name of all Slavic tribes - the name is also known from the area of today's Hungary, Slovenia, Slavonia, Russia (in the vicinity of Novgorod ) and Pomerania (see the Slovinces, which died out around 1900 ). The names of the Slovaks and Slovenes are derived from him.

Between Hungary, Poland and Bohemia (907-1030)

In the 20s of the 10th century, Lél (Lehel), one of the Hungarian tribal leaders (the Hungarians at that time still consisted of numerous tribes), made Nitra and southwestern Slovakia (i.e. the lowlands) his seat. The rest of Slovakia fell apart for Centuries - until it was successively conquered by the Hungarians from the 11th to the beginning of the 14th century - in small Slavic / Slovak principalities located around certain fortified towns . The core of today's Slovakia (the areas up to the rivers Waag and Hornád ) was conquered by the Hungarians around 1100. Until 1108, Slovakia (the Neutra Principality) was considered a special area within the Kingdom of Hungary . The area of the Hungarian Archdiocese of Esztergom (Slov. Ostrihom, German Gran), established around 1000, coincided with the area of the Principality of Neutra.

The entire functioning of Greater Moravia, the division into counties , church structure, military system, etc., was taken over by the Hungarians, similar to the Duchy of Bohemia and the Kingdom of Poland , for lack of their own models . The Hungarians also adopted around 1200 words from Slovak and 1000 other words of Slavic origin, according to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, for lack of their own terms. The Slovak nobles from the time of Great Moravia (especially the Poznans and Hunts ) played an important role in the early history of Hungary. The most important Hungarian ruler of Neutra was Michael (971–995), who became so powerful that the then Hungarian Grand Duke Géza had him murdered. Géza and his son Stephan (Vajk) were both first princes of the Neutra principality before they subsequently became rulers of all of Hungary. (For further details see under Neutra Principality .)

It is also likely that the north (or possibly the northwest) of present-day Slovakia was under the influence of the so-called White Croats at the beginning of the 10th century . Then in the 11th century Polish influence prevailed in the northern Slovakian regions of Arwa (Orava) and Spiš , especially since the Spiš was under the Krakow bishop in the 11th century and the whole of Slovakia was temporarily annexed by Poland to the Danube 1000-1030 . There is also controversial evidence that Eastern Slovakia belonged to the Kievan Rus sometime in the middle of the 11th century (see also History of Carpathian Ukraine ) and that Western Slovakia was under Bohemian suzerainty around 955–975 / 999.

The Slovak ethnogenesis , which began in the 8th century, was completed after 955 when the Hungarians were defeated on the Lechfeld and decided to settle definitely in today's Hungary, which split the Slavic population of this area into today's Slovaks, Slovenes , Croats , etc. .

Part of the Kingdom of Hungary

High and late Middle Ages (1030–1526)

The mining industry , which has been intensively practiced since the 11th century, and the German settlers who arrived especially since the 13th century (after the great Mongol invasion of 1241/1242) made Slovakia the most prosperous area in the Middle Ages , but also into the 18th century of the Kingdom of Hungary. Around 1400 gold and silver mining in Slovakia reached 40% and 30% of the total world production at that time. The first medieval cities of the kingdom emerged from the 13th century, mostly in the area of today's Slovakia.

The 11th and 12th centuries were a time of clashes between Hungary, on the one hand, and the Holy Roman Empire and / or Bohemia, on the other, which often took place in Slovakia. Politically, the Neutra border principality (Ducatus) (1048–1108) emerged in the area of today's Slovakia in 1048 . It was ruled by Hungarian aspirants to the throne. With its dissolution in 1108, the area was fully incorporated into the Hungarian Kingdom, which lasted until 1918. (For details see under Neutra Principality .)

Around the year 1300 Slovakia was de facto taken over by the nobles Mattäus Csák III. ruled by Trenčín (Čák, Chak, Chaak, Czak) in western and central Slovakia and Omodej (Amadeus, Amadé, Amadej, Omode) by Aba in eastern Slovakia.

In 1412 Sigismund of Luxemburg pledged some towns of the Spiš to Poland-Lithuania . The cities remained under Polish-Hungarian administration until 1772. From 1419–1437 Sigismund of Luxembourg had to fight the Czech Hussites in Slovakia as well . 1440–1453 the Czech nobleman Johann Giskra (Ján Jiskra) occupied Slovakia for the Habsburgs during the wars for the throne in the Kingdom of Hungary . Between 1445 and 1467 the rulers of Hungary fought against the post-Hussite rebellious Bratríci in Slovakia. In 1467, the first university in Slovakia was established in Pressburg and at that time the only university in the Kingdom of Hungary.

The government of the Jagiellonian kings (1490–1526) from Poland was marked by anarchy throughout the kingdom, which ultimately led to the Mohács disaster in 1526.

Anti-Habsburg uprisings and wars against the Ottomans (1526–1711)

After the Battle of Mohács (1526) , which ended with a victory for the Ottomans , and a subsequent civil war (1526–1538), the Kingdom of Hungary was divided into three parts:

- The Habsburg "Royal Hungary" (in fact a Habsburg province): today's Slovakia (except for Turkish areas in the extreme south of central Slovakia) and a small part in the northeast of today's Hungary with Burgenland and western Croatia. These were all areas that were almost exclusively inhabited by non- Magyars , Germans and Slavs.

- Transylvania in present-day Romania on this side of the Carpathian Arc (subsequently extended to eastern Slovakia), which was a Turkish vassal and later the starting point for the anti-Habsburg uprisings in Slovakia.

- The Turkish province in the center and south of the Kingdom of Hungary, which was a direct part of the Ottoman Empire .

Although Slovakia remained formally part of Hungary, more than 400 years of Magyar-influenced politics came to an end at the beginning of the 16th century with the Turkish conquest of today's Hungary, and a policy determined by the House of Habsburgs prevailed. Pressburg became the capital and coronation city of Hungary (1536) and Trnava (Eng. Tyrnau , Hungarian Nagyszombat ) became the seat of the archbishop (1541).

In addition, the Reformation took hold in Slovakia after 1521 . In the 17th century, however, a very successful Counter-Reformation began , which slowly turned the largely Protestant Slovakia back into a largely Catholic country.

Parallel to the almost uninterrupted struggle against the Ottomans (1520–1686), who also conquered parts of southern central Slovakia and plundered the rest of Slovakia, several anti-Habsburg uprisings followed from 1604 to 1711, namely the uprising of Stephan Bocskay (1604–1606), the uprising of Gabriel Bethlen (1619–1626), the uprising of Georg I. Rákóczi (1644–1645), the Wesselényis conspiracy (1664–1671), the first Kuruc campaign ( 1672 ), the Kuruc partisan war (1672–1678), the uprising of Emmerich Thököly (1678–1687 / 1688) and the uprising of Franz II. Rákóczi (the "Kuruzenkrieg", 1703–1711). Common characteristics of the uprisings were that they were directed against the Habsburgs, against the Counter-Reformation and against Viennese centralism and were usually supported by the Ottomans. But each of them also had very specific causes. Except for the Kuruzenkrieg and the Wesselényis conspiracy , they took place almost exclusively in what is now Slovakia and began in Transylvania. Their leaders were often also princes of Transylvania.

Enlightenment (1711-1848)

General developments

After almost 200 years of anti-Turkish struggles (1520–1686) and anti-Habsburg uprisings (1604–1711) in Slovakia, the peace of Sathmar / Satu Mare (1711) marked the beginning of a long period of peace. This enabled a clear economic, social and cultural consolidation. About 92% of the burden of rebuilding the Kingdom of Hungary had to be borne by the cities and the servants in Slovakia. The Slovaks populated the depopulated areas in the south (since 1690). 50% of the total population of the Kingdom of Hungary lived in Slovakia, the Slovak economic potential was 1400% higher than that of the rest of Hungary, which was recaptured from the Turks, and 70% of the artisans and merchants of Hungary were resident in Slovakia.

Just when Pressburg had become the largest city in the Kingdom of Hungary at the end of the 18th century, Emperor Joseph II moved the Hungarian central authorities to Buda (Slov. Budín, German furnace) in 1784 . However, coronations took place in Pressburg until 1830 and sessions of the Hungarian state parliament until 1848 . The importance of Slovakia decreased significantly in the first half of the 19th century.

The French Revolution that broke out in 1789 also had an impact in Slovakia and the rest of Hungary. In 1794, under their influence, the so-called movement of the Jacobins of the Kingdom of Hungary, the so-called conspiracy of Ignjat Martinović (Slov. Ignác J. Martinovič, Hungarian I. Martinovics) arose . Around 200 people across the country were involved, including a large number of Slovaks. Their goal was the creation of a democratic republic based on the French model, the abolition of the monarchy and the conversion of Hungary into a federation consisting of the provinces of Hungary, Slovakia, Illyria and Wallachia . But the conspiracy was betrayed.

The Napoleonic Wars also affected Slovakia: Russian troops passed through (1789–1800), Napoleonic troops occupied Pressburg in November 1805 and December 1805 with the signing of the (fourth) Peace of Pressburg after the Battle of Austerlitz ; 1809 with the signing of an armistice by Napoleon and the demolition of the Devín Castle / dt. Thebes . The Kingdom of Hungary lost a total of 120,000 soldiers in the Napoleonic Wars, a large number of whom also came from Slovakia. The emperor did not convene the state parliament of Pressburg from 1812 to 1825, because it did not want to meet its financial demands after the bankruptcy of the Austrian monarchy (1811). In 1815, many negotiations took place during the Congress of Vienna in neighboring Pressburg.

In May 1831 the plague spread from Galicia in eastern Slovakia . The subsequent hygiene measures by the authorities triggered the East Slovak Peasant Uprising (also known as the Cholera Uprising ) in the uneducated and starving population in the summer , in which 40,000 insurgents were involved.

While around 90% of the Slovak population was Protestant at the beginning of the 17th century, the tide turned in the 18th century (after 1711) and the Protestants slowly became a minority (until today). In the Catholic area, Emperor Joseph II deprived the bishops of the right to educate priests and instead set up state general seminars. One of them was built in Pressburg in 1783 and played an important role in the national movement of the Slovaks.

economy

The 1720s brought an important innovation - the manufactories (since 1722, not more widespread until 1784). The beginnings of the industrial revolution (industrialization) and with it the first factories in Slovakia go back to the 1820s and 1830s, but most of the factories were not built until the end of the 19th century. The 18th century is also known as the Golden Age of Slovak mining. In the 19th century, the centuries-old mining of precious metals , the amount of which was slowly being used up after several centuries of exploitation, was replaced by the mining of iron ore . The Slovak Ore Mountains became the main area of iron ore mining in the kingdom. In 1831, 78% of the pig iron and 64% of the cast iron production of the Kingdom of Hungary were produced in Slovakia.

The most important industrial centers in Slovakia were Pressburg and Košice (German: Kaschau). After the central authorities were relocated from Pressburg to Buda in 1784 , Pressburg was replaced by Buda in its role as the most important economic and industrial center of the Kingdom of Hungary during the first half of the 19th century.

It was not until 1840 that the first (horse) railway line in the Kingdom of Hungary was opened between Pressburg and the suburb Svätý Jur . In 1848 the connection Pressburg – Vienna followed (also the first steam railway line in the area of today's Slovakia) and in 1850 Pressburg – Pest (city) .

Culture and language

In the field of culture and language, the greatest Slovak scholar of the 18th century, Matej Bel (Bél Mátyás, Matthias Bél), became rector of the Evangelical Lyceum in Pressburg, founded in 1607 . In 1735 a mining school was established in Banská Štiavnica , which in 1762 became the world's first famous mining college. In 1819 Cardinal Alexander Rudnay of Slovakia became Archbishop of Esztergom (Gran). Among other things, he promoted Slovak religious literature and in 1830 crowned the last Hungarian king who was crowned in Pressburg.

Beginnings of the Magyarization

In 1784, as part of Joseph II's efforts to centralize, German (instead of Latin ) was introduced as the official and teaching language in the Kingdom of Hungary (abolished in 1790). The result was an increasing Magyar nationalism . In 1790 and 1792 the Diet passed the first laws promoting the Hungarian language at the expense of the other languages used in the kingdom. This marked the beginning of the Magyarization of the kingdom's non-Magyar population, which then gradually increased in the 19th century. The Magyars (= ethnic Hungarians), especially their nobility, began to regard themselves as the only state people in the Kingdom of Hungary, in which, however, they only made up a minority of the population. Since the 1820s, however, there have been clear and open efforts to convert the kingdom into a state with Hungarian as the only language. There were nobles who wanted to achieve a gradual assimilation of the non-Magyars of Hungary (middle nobility under the leadership of István Széchenyi ), but also those who wanted to create a radical Magyar nation-state (lower nobility under the leadership of Lajos Kossuth ). In the 1830s, the radical group prevailed. In the 1840s this turned against the Slovaks in particular. In the 1830s and 1840s, especially in 1844, Latin, which had been used as the official language in the kingdom for about 1,000 years, was gradually replaced by the Hungarian language, which met with fierce opposition from non-Magyars.

National rebirth of the Slovaks

The national consciousness of the Slovaks increased significantly in the 18th century and - similar to the Magyars and other nations of this region - under Joseph II (1780–1790), under the influence of the Enlightenment, the process of forming the modern Slovak nation (also Called national rebirth ). This process (1780–1848 / 1867) is usually divided into three phases (generations, 1780–1820, 1820–1835, 1835–1848). It culminated in 1843 in the codification of today's form of the Slovak written language by Ľudovít Štúr and in the participation of the Slovaks in the revolution of 1848/49 together with Vienna against the Magyars. During the revolution of 1848, the Slovaks fought together with the imperial troops against the Magyars (→ Slovak Uprising ).

Before the First World War (1850-1914)

A longer period of peace followed in Slovakia in the second half of the 19th century. Until the Austro-Hungarian settlement in 1867 , the German Austrians had dominance in the Kingdom of Hungary, including Slovakia, but since 1867 the Magyars as the second “ruling people”.

The official language in Slovakia was 1849-1868 German (language of the courts predominantly Hungarian ), and also in contact with the simple Slovak population Slovak tolerated. German and Hungarian were the official languages from 1860 to 1868. From 1868 on, Hungarian was the almost exclusively official language.

1850–1867 (Bach era and provisional period)

In Slovakia and the other parts of the Habsburg Monarchy , it was hardly possible to devote oneself to national activities during the neo-absolutist era of Bach (1851–1859). The leaders of the Slovaks Ľudovít Štúr and his colleague Jozef Miloslav Hurban , for example, were under constant police supervision as "suspects". The activities were only increasingly resumed after 1861.

With regard to the written Slovak language , in principle it finally took on its present form in 1851 at a meeting of Slovak personalities. In the same year the government in Vienna in Slovakia temporarily introduced "Old Slovak" as the official language (see also Ján Kollár ).

On June 6th and 7th, 1861, at a meeting of 6,000 Slovak personalities in the city of Martin, the memorandum of the Slovak nation was adopted, which among other things, the creation of an independent territorial unit in the territory of Slovakia (the "Slovak region"), the application of Slovak in the Slovak counties, the creation of a professorship in Slovak languages at the University of Pest, the possibility of establishing Slovak cultural and literary associations and the like. In December, the Slovaks then submitted the modified Vienna Memorandum to the emperor , in which they already demanded their own parliament and crown land . The emperor then allowed the Slovaks to use three only Slovak-speaking grammar schools (1862 Veľká Revúca , 1867 Martin, 1869 Kláštor pod Znievom ) and, above all, in 1863 the Slovak Matica ( Matica slovenská - matica means 'source / queen bee' in Serbian) goes back to the Serbian Matica founded in 1826 ), a society for the maintenance of the Slovak language, culture and science. The first chairman of Matica was Štefan Moyzes , its seat was Martin. In the absence of other Slovak institutions, Matica advanced to become a representative of the Slovaks and established contacts with other cultural and scientific institutions in Europe.

Politically, there were two groups in Slovakia in the 1860s and 1870s. One of them was the Old Slovak School (Stará škola slovenská) , which was in favor of traditional cooperation between the Slovaks and Vienna against the Magyars. The most important representatives were Jozef Miloslav Hurban, Štefan Marko Daxner and Janko Francisci . The Slovak National Party emerged from this group in 1871 . The second, smaller group was the New Slovak School (Nová škola slovenská) , which campaigned for an understanding with the Magyars and existed until 1875.

1867-1914

After the Empire of Austria was balanced with the Kingdom of Hungary in 1867, the Austrian monarchy split into two loosely connected parts, which were unofficially known as Cisleithanien and Transleithanien . While in the following years life in Cisleithanien (Austria) became increasingly democratic and liberal , in Transleithanien (Hungary) the feudal system was more or less maintained. The oppression of non-Magyar nations increased significantly and the economic level was significantly lower than in Cisleithania.

In 1869 Jozef Miloslav Hurban, one of the leading figures of the Slovaks, was imprisoned by the Hungarian authorities, but after criticism in Viennese newspapers he was released again in 1870 on the basis of an order from the Austrian emperor. In 1874–1875, the Hungarian authorities closed the only Slovak secondary schools (grammar schools). During the reign of Kálmán Tisza (1875–1890), the Matica slovenská was closed in 1875, the assets of which were confiscated through gifts from the Slovaks and the emperor, and which has become the national symbol of the Slovaks to this day. Under this Prime Minister, who said in 1875 that he did not know any Slovak nation, the Slovaks were not only culturally but also economically oppressed. Numerous business enterprises of the Slovaks were called " Pan-Slavic enterprises" and therefore closed.

After the state elections of 1865, no Slovaks (1869: 4, 1872: 3, 1875/1881/1896: 0, 1901: 4, 1905: 2, 1906: 7, 1910: 3) made it into the 415-strong Hungarian state parliament , although according to the censuses, the Slovaks were entitled to around 40–50 seats. In the elections of 1878 and 1884–1901, the Slovak National Party did not take part in protest against the election manipulation. Only the richest or aristocratic citizens (5% of the population) were eligible to vote, corruption, acts of violence in the election, the arrest of non-Magyar candidates, and the deletion of Slovak personalities from the electoral list were common.

The Slovak politicians only became active again in the second half of the 1890s . The Slovak National Party was divided into several currents at this time: The Catholic current, led by priest Andrej Hlinka , founded the Slovak People's Party in 1906 and 1913 , which played an important role later in the 20th century. The so-called Hlasists represented another current - these were Slovak students in Prague, Vienna and Budapest. It was strongly influenced by the Prague professor Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk . This current was replaced in 1909 by the likewise liberal and pro-Czechoslovakian Prudists . The Hlasists and the Prudists were committed to the creation of Czechoslovakia . The last movement was the peasant movement under the leadership of Milan Hodža , which before the First World War sought to work with the heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand , who campaigned for the federalization of Austria-Hungary. In addition to the Slovak National Party, the Slovak Social Democratic Party was formed in 1905 under the influence of Czech Social Democrats (since 1906 an autonomous parliamentary group of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party ). In addition to social democratic achievements, it also demanded complete equal treatment of the Slovaks.

In 1907 the priest Andrej Hlinka was jailed by the Hungarian authorities on fabricated charges. In 1909 he was declared innocent by the Holy See . In 1907 there was also the Černová incident , which drew the world's attention to the situation in Hungary: Hungarian gendarmes shot 15 residents in this village (including pregnant women and children), seriously injured 12 and imprisoned 40 other villagers for these wanted to prevent their new church, which they built, from being consecrated by a Hungarian priest instead of Andrej Hlinka, who was born there. This act was criticized not only by the foreign press, but also by the chairman of the Austrian parliament and above all by the Czech members of this parliament.

From the end of the 19th century there was an intensification of cooperation between the Czechs and Slovaks. In addition to the activities of Slovak students in Prague (see Hlasists above), practically all Slovak political currents had contacts with the Czechs. A few years before the beginning of the First World War, there was also intensive cooperation between Czech and Slovak emigrants in the USA . But there were also many Slovaks who maintained close contacts with the Croats , Serbs , Ruthenians and Romanians , who also lived in the Kingdom of Hungary, as well as with the Russians .

The American Slovaks were also very active. By 1900 there were already 12 important Slovak associations in the USA, which among other things published more newspapers and magazines than was the case in Slovakia itself. In 1893 the Slovak Matica in America was founded in Chicago , which continued the activity of the Matica, which was banned in 1875. In 1907 the Slovak League of America was founded in Cleveland (Ohio) with the aim of providing financial and political support to Slovakia.

Magyarization

After the Austro-Hungarian reconciliation, Magyarization, which in the years after the revolution (1849–1860) had been temporarily replaced by Germanization, reached its climax. It was declared the official state ideology. In 1868 all citizens of Hungary became members of “a single inseparable Hungarian [d. H. in Hungarian = Magyar] nation ”, although in 1850 less than 50% of the population of the Kingdom of Hungary were Magyars. Hungarian was also declared the only state language. The only three Slovak grammar schools in Slovakia (which had been founded by the Slovaks themselves) were closed in 1874–1875 because of "pan-Slavism". From then until 1918 there was not a single Slovak secondary school in Slovakia. In 1875 the Slovak Matica was closed. From 1879–1893, Hungarian was prescribed as the only language in kindergartens (1891) and elementary schools (1879) by several laws.

In several stages, initially hesitant, any national statement was visibly made impossible under Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza. The situation was hardened with Tisza's denial of the existence of the Slovak nation. Between 1872 and 1900 the number of Slovak-speaking primary schools in the entire kingdom fell from 1822 to 528 (-71%) and that of German from 1232 to 383 (-69%), while the number of Hungarian-speaking primary schools rose from 5,819 to 10,325 (+77 %). According to the official proportion of Slovak and German students, the Slovaks and Germans would have needed about four times as many schools at that time. Slovak students studying in Magyar schools (which was practically always the case) were forbidden to speak Slovak in or outside the school and to have Slovak books or newspapers, otherwise they would have to leave the school. In the 1890s, numerous Slovak-language theater performances and various associations (for example, the Myjava Literary Association in 1896) were banned. In 1898 a law came into force according to which all municipalities in the kingdom, regardless of their population, were only allowed to use Hungarian names. Planned protest meetings by Slovaks, Serbs or Romanians against these and other Magyarization laws were banned and authors of protest articles in newspapers were arrested.

In 1907, with the Appony School Acts (named after the then School Minister Albert Apponyi ), the climax of Magyarization followed: Due to this law, Slovak and German were only allowed to be taught as a foreign language for one hour per week. The laws at the world-famous mining academy in Banská Štiavnica , where the numerous foreign students, especially Germans, could no longer follow the lectures and had to move (mostly to Vordernberg or Leoben ) , had extremely negative consequences .

In the church sector, priests who did not want to work in Hungarian were sent to the poorest villages in the mountains. For priests (schools) the rule was that they had to accept various penalties for mere possession of Slovak-language books as well as for using the Slovak language.

In 1883 and 1885 the authorities founded the FMKE ( Felsőmagyarországi Magyar Közművelődési Egyesület / Hungarian Educational Association for Upper Hungary ) and the MTK ( Magyarországi Tót Közművelődési Egyesület / Educational Association for the Hungarian Slovaks), which had the task of the Slovak Magyars in particular. At the end of the 19th century (according to some sources up to 60,000) Slovak children were sent for labor service in Hungarian-speaking parts of the kingdom under the auspices of the FMKE (especially in 1887 and 1892) due to official orders.

The rigorous Magyarization policy, which was particularly successful among the Slovak and German-speaking population of Transleithania, caused the Magyar population to grow to just over half. Between 1880 and 1910 the percentage of citizens of Hungary (excluding Croatia) who professed to be Magyars rose from 44.9 to 54.6 percent. In 1913, only 7.7% of the total population were eligible to vote or were allowed to hold public offices. After a change in voting rights shortly before the end of the war, this percentage rose to a full 13%. From 1900 to 1910 the number of Slovaks, for the first time also in absolute terms, had fallen to 1.7 million. The first Czechoslovak population census in 1921 showed, however, that this Magyarization was often only temporary because the number of Magyars had decreased by 250,000, while that of Slovaks had increased by 300,000.

Economy, emigration, Slovaks abroad

The Kingdom of Hungary was gripped by modernization and urbanization from 1850 to 1918 . Slovakia was one of the most industrially rich areas of the Kingdom of Hungary, although Hungary as such was still very backward industrially. Outside of the main industrial areas of Slovakia, Bratislava / Pressburg and the Spiš, there were numerous areas, especially in eastern and northern Slovakia, where the population was starving. This development was also strengthened by the slow decline of the once so important Slovak mining industry and by the fact that, as part of the Magyarization policy, the Slovaks were not allowed to work for the railway or in public administration, for example.

A consequence of poverty, the cholera epidemic from 1872 to 1873 (in which 2.3% of the Slovaks died) and partly also the repressive Magyarization was the mass emigration of Slovaks, Germans and Ruthenians , which to a greater extent at the end of the 1870s began and peaked at the beginning of the 20th century. About 40–50% of the emigrants from the Kingdom of Hungary came from the counties in Slovakia, especially from eastern Slovakia. Between 1871 and 1914, around 650,000 people, mostly Slovaks, emigrated from Slovakia, including 500,000 to the USA (mainly to the east coast) and 150,000 to other parts of the Kingdom of Hungary ( Budapest , Transdanubia , Transylvania) and Europe (mainly to Vienna). Slovakia had only 2.6 million inhabitants in 1890.

The American Slovaks contributed significantly to the maintenance of the Slovak national consciousness and to the later emergence of the state of Czechoslovakia . The 500,000 American Slovaks made up about a quarter of all Slovaks just before the start of the First World War. In 1860 and in the following years fought the first Slovak immigrants in the context of the Slovaks of Gejza Mihalóci (which after the Fort Mihalotzy in Tennessee was named), founded Slavic military unit Slavonian Lincoln Rifle Company in the American Civil War on the side of the northern states .

Although Pressburg was the largest city in Slovakia in 1900 with 60,000 inhabitants, the city of Pittsburgh (just before the First World War) became the city with the most Slovaks in the USA. In addition, many Slovaks lived in the Hungarian capital Budapest (1900 about 110,000, in 1910 about 150,000 inhabitants of Budapest were born in the area of today's Slovakia). Since 1690 Slovaks had emigrated to the southern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary, so that by 1900 there were already around 500,000 Slovaks living in what is now Hungary, Serbia, Romania and Croatia.

First Czechoslovak Republic

In 1918 Slovakia merged with the countries previously ruled by Austria, Bohemia and Moravia, to form Czechoslovakia .

Shortly after the Munich Agreement came into force on September 30, 1938 under German pressure , Slovakia was granted autonomy and lost its southern territories to Hungary due to the First Vienna Arbitration on November 2, 1938.

First Slovak Republic

Under pressure from Adolf Hitler , who threatened to divide the country between Poland and Hungary, and Czech troops who had advanced on Slovak territory, the Slovak parliament declared Slovakia on March 14, 1939 the Slovak Republic , later called the First Slovak Republic , for independent. The state was under the strong influence of the German Reich, with which it concluded a so-called protection treaty shortly after the declaration of independence on March 23rd . This gave Germany far-reaching opportunities to influence the Slovak economy and foreign policy. In addition, the German Reich was allowed to militarily occupy a strip along the border with Moravia (following the course of the eastern fringes of the Little and White Carpathians and the Javorník Mountains ) as a "protection zone". The German declaration to protect the integrity of Slovak territory soon proved ineffective when Hungary attacked from the east and occupied parts of eastern Slovakia (see Slovak-Hungarian War ). In 1939, German troops attacked Poland from Slovakia and with the participation of Slovak associations. By 1944 at the latest, the National Socialist genocide as a result of the Slovak National Uprising was systematically extended to Slovakia.

Deportations of the Slovaks or the Roma did not take place. However , after constant pressure from the Reich, the Jews were recorded by the police and deported to concentration camps abroad (the planned labor camps for Jews were then not established). At least 57,000 Jews had been deported from Slovakia by October 1942. However, after it became public what kind of “labor camp” abroad it was in reality, the transports were stopped. The deportations were resumed at the end of 1944. The reason for this was the military occupation of the whole of Slovakia by the German Wehrmacht after the Slovak National Uprising (and the access of the SS and SD as a result). Many Slovaks were involved in this militarily failed but important uprising against Hitler in the post-war period in August 1944.

Third Czechoslovak Republic

After the Second World War , Slovakia lost its short-lived independence and again became part of the communist Czechoslovakia from 1948. Carpathian Ukraine was occupied by the Soviet Union and is now part of Ukraine , and the borders of the now part of the state have been slightly corrected, for example in the south of Bratislava, the so-called Bratislava bridgehead and a major swap of territory on the eastern border with the former USSR. A city and some communities in the area south of Uzhhorod as far as Chop came to the Ukrainian SSR:

| Slovak | Ukrainian | transcription | Transliteration | Hungarian 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galoč | Галоч | Halotsch | Haloč | Gálocs |

| Palov | Палло | Pallo | Pallo | Palló |

| Batva | Батфа | Batfa | Batfa | Bátfa |

| Palaď + Komarovce | Паладь-Комарівці | Palad Komariwzi | Palad'-Komarivci | Palágykomoróc |

| Surty | Сюрте | Sjurte | Sjurte | Anger |

| Malé Rátovce | Малі Ратівці 1 | Mali Rativtsi | Mali Rativci | Kisrát |

| Veľké Rátovce | Великі Ратівці 1 | Velyki Rativtsi | Velyki Rativci | Nagyrát |

| Male Slemence | Малі Селменці | Mali Selmenzi | Mali Selmenci | Kisszelmenc |

| Salamúnová | Соломоново | Solomonovo | Solomonovo | Tiszasalamon |

| Téglás | Тийглаш | Tyhlasch | Tyhlaš | Kistéglás |

| Čop | Чоп | Chop | Čop | Csap |

1 District of Ратівці (Ratiwzi, Rativci)

2 Officially until 1918 and 1939–1945

In return, the place Lekárovce came to Czechoslovakia.

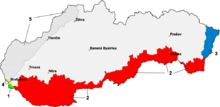

- 1 - Bratislava bridgehead , handed over by Hungary on October 15, 1947

- 2 - Jabłonka Region, belonged to Poland from March 12, 1924 to November 21, 1939 and from May 20, 1945

- 3 - Nowa Biała area (Slovak Nová Bela, German Neubela ), belonged to Poland from March 12, 1924 to November 21, 1939 and since May 20, 1945

- 4 - Strip of land with and north of the city of Chop , came to the Soviet Union in 1945 as part of the cession of Carpathian Ukraine

- 5 - Lekárovce and its immediate vicinity became part of Czechoslovakia in 1946 in the course of the adjustment of the border to Carpathian Ukraine

Before the end of the war in 1945, the German population was mostly evacuated from the advancing Red Army , and some were also expelled (see Carpathian Germans ). There was a partial “population exchange” among the Hungarian population.

Independent Slovakia since 1993

After independence, Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar and his HZDS minority government, which had been in office since the parliamentary elections in 1992 and was supported by the Slovak National Party (SNS), remained in office. The HZDS nominee Michal Kováč was elected President. From October 1993 the parties HZDS and SNS officially formed a coalition. After several resignations by HZDS MPs and the split in the SNS, Mečiar's second government became a minority government again in the spring of 1994. On March 14, 1994, Mečiar was removed from parliament after the President's criticism of his style of government and replaced by a nine-month transitional government of the opposition parties under Jozef Moravčík ( see Jozef Moravčík's government ).

"Mečiarism" and "Third Way" (1994–1998)

The early elections in September 1994 again won Mečiars HZDS with 35% of the votes, which then formed a coalition with the right-wing extremist SNS (5.4%) and the left-wing populist ZRS (7.3%), which had recently entered parliament ( see Government of Vladimír Mečiar III ). The authoritarian and populist style of government of the Prime Minister and his HZDS established in the following years was or is often referred to as "Mečiarism" (Slovak. Mečiarizmus ).

In terms of economic policy, the 1994 coalition refused to allow the total market opening desired by the West and insisted on greater room for maneuver for social, regional and national politics. Mečiar opposed the model of a “market economy without adjectives” as it was introduced in the Czech Republic with an eco-social “third way” between socialism and capitalism. In economic policy, the state should act as a moderator and protector of the domestic economy. Privatizations were not rejected in principle, but the economy should submit to the political guidelines of the government. Attempts were made to create a domestic capital-forming class, whereby privatizations often resulted in nepotism . In 1996, Slovakia recorded the highest economic growth among the post-communist countries with 6.5%. However, since this was achieved with massive public investments by the government, which took out generous foreign loans for this purpose, the foreign debt tripled to 12 billion US dollars or 60% of GDP.

In domestic politics, chronic disputes dominated between Prime Minister Mečiar and his government on the one hand and President Kováč and the opposition on the other, resulting in numerous authoritarian , illegal and criminal acts by the government. At the first session of the newly elected parliament in November 1994 (known in Slovakia as “Noc dlhých nožov”, dt Night of the Long Knives ) the opposition was ousted from all parliamentary offices and other control functions, including posts in the public media were awarded exclusively to nominees from the Mečiar government. There were attempts to exclude the opposition party DÚ from parliament and to intimidate journalists critical of the government with violence. In 1995 the president's son was kidnapped to Austria and one year later the police officer who acted as a leniency witness was murdered (the Slovak secret service is said to have been involved in both cases). At the end of 1996, the Mečiar government unconstitutionally withdrew his mandate in parliament after he had left the HZDS. Earlier, a bomb exploded in front of the MP's house after he refused to voluntarily give up his mandate. In 1997 a referendum on the direct election of the president and joining NATO was prevented by the government. After President Kováč's term of office expired on March 2, 1998, the government and the opposition could not agree on a candidate, which meant that Slovakia had no head of state for a year. As President of the Commission, Mečiar issued amnesties to all persons involved in the kidnapping of the President's son, which made criminal prosecution impossible.

The Mečiar government's minority policy was also often criticized. The treatment of the Hungarian ethnic group in particular contained considerable explosives. The government in Bratislava had already increased the pressure on the Magyars in 1992, abolished bilingual place-name signs in the predominantly Hungarian-populated areas of the country and arranged for Hungarian first names to be entered in the birth register only in Slovak form. Tensions also grew on the issue of mother tongue teaching. The basic treaty signed in March 1995 between Slovakia and Hungary could not be ratified initially because of the resistance of the Slovak National Party. Its confirmation by the Slovak parliament in 1996 hardly changed the situation of the minority. The Law on the State Language, which came into force on January 1, 1996, provided for the use of Slovak in all authorities in the country, even in a business conversation between an official and a citizen who were both ethnic Hungarians. Following a request from the opposition Hungarian party and the KDH, the Slovak Constitutional Court declared parts of the law to be unconstitutional. A law on the territorial and administrative division of the country of March 1996 drew the boundaries of the new administrative units in such a way that the Hungarian minority in none of the new administrative units barely exceeded 30 percent of the population. The leaders of the Hungarian minority then accused the government of curtailing their political say with this administrative reform .

In terms of foreign policy, Vladimír Mečiars from 1994–1998 strived for a balance between East and West, as it had done during his two previous governments. The Mečiar government officially declared an interest in Slovakia joining NATO and the EU, but since the relationship with the West deteriorated increasingly from the mid-1990s, Slovakia increasingly moved closer to Russia. In a military cooperation agreement, Slovakia granted Russia use of all Slovak military airports, making Slovakia an outpost of Moscow in Central Europe. As a result of Western criticism of the foreign policy orientation, economic policy and authoritarian practices in the country's domestic policy, Slovakia was removed from the list of candidates for NATO's first eastward expansion and initially fell back into the second row as a candidate for EU accession. While functionaries of the Mečiar party declared that they “do not want to enter the European Union on their knees”, then US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright warned that Slovakia was threatening to become “the black hole of Europe”.

Western integration and the neoliberal era (1998-2006)

In the parliamentary elections in September 1998 , Mečiars HZDS was again the strongest force with 27% of the vote, but its previous coalition partner ZRS was thrown out of parliament, an alliance with the SNS was no longer sufficient for a majority and the opposition parties had all ruled out a coalition with Mečiar , the HZDS went into opposition despite the election victory with the SNS. The new government created a pro- Western coalition of the liberal-conservative electoral alliance SDK , the post-communist SDĽ , the left-liberal SOP and the Hungarian party SMK . The new Prime Minister was the chairman of the SDK Mikuláš Dzurinda ( see government Mikuláš Dzurinda I ). In the parliamentary elections in 2002 , the scenario from 1998 was repeated. With heavy losses, Mečiars HZDS again took first place with 19.5%. However, since Mečiar was again unable to find a coalition partner due to his bad reputation in the West, Dzurinda remained Prime Minister for another four years. During his second term in office, his coalition consisted of the liberal-conservative SDKÚ-DS , the Catholic-conservative KDH , the neoliberal ANO and the Hungarian party SMK ( see government Mikuláš Dzurinda II ).

The first Dzurinda government, which had a majority in parliament to change the constitution, made the country's integration into the West a top foreign policy priority. Before the end of 1998, all heads of administration, presidents of Slovak courts, theater directors and journalists from state television were dismissed and their posts were filled again as part of a so-called “de-meciarization”. Furthermore, a constitutional law was passed, which enabled the direct election of the president. In the 1999 presidential election, the ruling coalition candidate Rudolf Schuster won the runoff election against opposition leader Mečiar, giving Slovakia a head of state again after a one-year break, which contributed to the country's stability. At the same time, Slovakia was now more open to Western investors. Liberalization was advanced and the rule of law expanded. Official accession talks with the EU began in February 2000 . In May 2003, during the referendum on Slovakia's accession to the EU, 52% of those eligible to vote, 90% of those who went to the polls, voted for EU membership.

The new government also pursued a more offensive policy with regard to NATO membership. In 1999, during the war in Kosovo, the Dzurinda government decided to open up Slovakian airspace to NATO support and combat aircraft. Russia was now completely ignored in Slovak foreign policy and Slovakia participated in the international military missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina , Kosovo , Afghanistan and Kuwait . In 2003, Slovakia supported the Iraq war as part of the 2003 Coalition of the Willing . In 2005, George W. Bush became the first US president to visit Slovakia.

In terms of economic policy, Dzurinda implemented tough austerity measures and radical neoliberal economic reforms in his second term . The first austerity program passed shortly after the parliamentary elections in 2002 on November 14th was the toughest budget adjustment program of an EU candidate country to date and contained price increases for electricity, gas, petrol, rents, public transport, alcohol and cigarettes as well as an increase in the value added tax that had existed since 1993. The second austerity program followed in 2004. On January 1, Slovakia became the first European country to introduce a flat tax of 19%. As part of a health reform, hospitals and health insurance companies were converted into corporations. All these measures increased the attractiveness of Slovakia for foreign investors and so the amount of foreign investments increased sevenfold in the years after 1998. The reforms of the Dzurinda government were rated extremely positively in Western media. Slovakia has moved "from last to first place" and Bratislava has become the "tiger on the Danube".

There was also a turning point in minority politics. As one of its first essential official acts, the government introduced an amendment to the language law passed under Mečiar in 1995 in parliament. According to their proposal, the Hungarian and Slovak languages were given equal status where the Hungarian minority made up at least 20 percent of the population. Place signs should also be bilingual there and school reports should be issued in Hungarian on request. The Slovakization of names of members of the minorities would henceforth cease to apply. In addition, a faculty for Hungarian teachers was established at the University of Nitra and the Hungarian -speaking János Selye University in Komárno.

Left national reorientation (2006-2010)

In June 2006, early elections were held in Slovakia . They ended with a victory for the former opposition politician Robert Fico and his left-wing populist party Smer-SD (29.1%), which a week after the elections signed a coalition agreement with the nationalist SNS (11.7%) and Mečiar's much-shrunk HZDS (8, 8%) closed ( see also Government Robert Fico I ). The new coalition was described by the critical media as a "cabinet of horrors" and "catastrophe" because, on the one hand, it was feared that the participation of the two ruling parties HZDS and SNS in the coalition in the 1990s would jeopardize the country's EU and NATO course could, on the other hand because the left-wing populist Smer-SD did not want to continue the neoliberal policy of the Dzurinda government.

In terms of foreign policy, Slovakia under Fico followed a course that was largely independent of the USA in 2006–2010 and strengthened relations with various non-EU states such as Russia, Serbia , Belarus , Libya , Cuba , Venezuela , Vietnam and China . Slovakia rejected the independence of Kosovo as well as the missile defense shield required by the USA in the Czech Republic and Poland, during the war in Georgia in 2008 Fico condemned the Georgian aggression and took sides with Russia. In 2007 the Slovak government withdrew all Slovak troops from Iraq, but in return increased its military presence in Afghanistan on the condition that Slovak soldiers would not be available for combat missions.

A permanent diplomatic conflict developed in the already strained relations with the neighboring state of Hungary, which from the beginning were not a good star because of the government participation of the SNS. In Hungary, politicians called for sanctions against their northern neighbors because of the SNS. At the first meeting with his Slovak counterpart, the Hungarian Prime Minister Gyurcsány asked Robert Fico to distance himself from his coalition partners, which he refused. In the period that followed, relations between the two states reached one low point after the other. In autumn 2006, for example, there were several violent crimes against ethnic Hungarians, which was widely discussed in the media by the opposition Hungarian party SMK as well as by the Hungarian government. The activities of the right-wing extremist Hungarian Guard of the Jobbik party also became a long-running issue in the interstate dispute . But Hungarian social democrats, liberals and conservatives also regularly interfered in Slovakia's internal affairs. In 2007 the Hungarian President László Sólyom and the social democratic Hungarian parliamentary speaker Katalin Szili traveled “privately” to Slovakia to meet representatives of the Hungarian SMK party. Prime Minister Fico then criticized the Hungarian officials for pretending to be in "Northern Hungary". The planned visit of the Hungarian President Sólyom to the Slovak border town Komárno in 2009 marked the absolute lowest point in the relations between the two states. He wanted to attend the opening of a monument in honor of the Hungarian King Stephan I. Since the date of the unveiling coincided with the anniversary of the crackdown on the Prague Spring by the Warsaw Pact in 1968, in which Hungarian troops were also involved, the Slovak President Ivan Gašparovič described this as a "provocation" and recommended Sólyom not to travel to Komárno. However, since this was ignored by the Hungarian President, Prime Minister Fico had a telegram sent to Budapest to warn President Sólyom that he might be denied entry to Slovakia. The Hungarian president arrived anyway, was turned away at the border bar and held a media-effective press conference on the Danube bridge in which he threateningly declared that he would “come back”.

In terms of economic policy, the Fico government was able to record Slovakia's acceptance of the Schengen Agreement on December 21, 2007 and the introduction of the euro on January 1, 2009 as a success. In 2007 Slovakia recorded the highest economic growth in the whole of the EU with 10.4%. However, due to the global financial crisis, GDP per capita shrank by 4.7% in 2009. The international world economic crisis also hit the Slovak financial sector, but unlike other countries it was hardly dependent on state support and at no point did it endanger macroeconomic stability. The flat tax introduced in 2004 was largely retained by the Fico government, but several privatization projects were halted, the government blocked gas price increases and extended workers' rights.

Domestically there were a number of patriotic measures, e.g. E.g. the installation of busts of important historical Slovak personalities in the entrance area of the parliament building (including the Slovak leader Andrej Hlinka , who was rehabilitated by law in 2008 ), the unveiling of an equestrian statue of the Moravian Prince Svatopluk I in front of the Bratislava Castle , which was also renovated by the Fico government, and the installation of two statues in honor of the Slav apostles Cyril and Method in the southern Slovak border town of Komárno . The media policy of the new government, which took a hostile attitude towards journalists throughout Fico's term in office, presented itself as conflictual. The press law of the Fico government of 2008 caused a stir. The most controversial point of the law was the right of reply by people who feel offended by published information. According to the new law, the Slovak newspapers should be obliged to print such counter notifications. In addition, the Ministry of Culture was given the power to impose fines if newspapers advocate “socially harmful behavior” or stir up politically motivated hatred. Despite oppositional and international criticism, the Smer-SNS-HZDS coalition disregarded these concerns and passed the new regulation on April 9, 2008. In 2009, Slovakia slipped 37 in the list of countries for press freedom of Reporters Without Borders Places in 44th place.

In the 2009 presidential elections, the incumbent President Ivan Gašparovič, supported by the Fico government, was able to clearly prevail over the opposition Iveta Radičová .

Liberal Intermezzo (2010-2012)

Regular elections to the National Council took place on June 12, 2010 , in which Fico's party Smer-SD clearly won with 34% of the vote. But since the SNS had been severely weakened and Mečiars HZDS was even elected from parliament, a conservative-liberal coalition of the parties SDKÚ-DS , SaS , KDH and Most-Híd was able to replace the Fico government and had been in place since July 8, 2010 power. The vice-chairwoman of SDKÚ-DS Iveta Radičová became the first woman to become Slovak Prime Minister. ( see Radičová government ). The Radičová government tried to tie in with the neoliberal reforms of the two Dzurinda governments and increased the value added tax from 19% to 20%. Large-scale privatizations were also planned, but the premature end of the coalition prevented their implementation. In October 2011, Radičová's government failed prematurely because the governing parties could not agree on the euro bailout fund . Richard Sulík's liberal SaS refused to approve participation in the EFSF , with Prime Minister Radičová combining the parliamentary vote on participation in the EU bank bailout package with her government's question of confidence. After Radičová had approved early elections, Fico's opposition Smer-SD supported the rescue package in a second vote. With his voting behavior in the "Euro rescue package" EFSF, Fico positioned himself out of the opposition as a reliable partner for the European state chancelleries. The unstable governance and a corruption scandal uncovered in December 2011, the so-called gorilla affair , inflicted great damage on the bourgeois-liberal parties.

Smer sole government (2012-2016)

In the early elections in March 2012 , Fico's Smer-SD party won an absolute majority with 44.4% of the vote and formed the first one-party government since the end of the communist dictatorship in 1989 ( see Robert Fico II government ). One of the first measures taken by the second Fico government was the resolution of a consolidation package worth 2.3 billion euros. Slovakia's new debt, which was 4.6% in 2011, is expected to drop to 3% by the end of 2013 in accordance with the Maasstricht criteria of the EU. As a basis for this, the flat tax introduced in 2004 under Dzurinda was abolished. Another innovation in economic policy was the creation of the “Council for Development and Solidarity” based on social partnership. The budget deficit was reduced from 4.3% to 3% between 2013 and 2014, which means that Slovakia again met the Maastricht criteria . On January 1, 2013, the Prime Ministers of Slovakia and the Czech Republic, Robert Fico and Petr Nečas, met on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the partition of Czechoslovakia. At the meeting, which was broadcast live on Slovak and Czech state television, both sides emphasized the extraordinarily good economic and social relations between the two countries. The partition of Czechoslovakia has been described as the “right step” and the “only way”.

Prime Minister Fico ran for the government camp in the 2014 presidential election in Slovakia , but was defeated in the runoff to former entrepreneur and philanthropist Andrej Kiska , who was supported by the opposition.

In terms of foreign policy, Slovakia officially supported the EU's common position during the Crimean crisis and the war in Ukraine from 2014, but the Slovak government repeatedly criticized the economic sanctions imposed on Russia and at times threatened to veto it together with the Czech government. Prime Minister Fico described the sanctions as “useless and counterproductive”, but at the same time referred to the solidarity support given to Ukraine by Slovakia in reversing gas transport. During the refugee crisis in Europe in 2015 , the Slovak government, like the governments of Poland and the Baltic states, declared that they were strictly against an EU quota system for the redistribution of refugees from Greece and Italy as well as a permanent, mandatory distribution key to all EU states. The government argued that it was not known whether there were “terrorists or extremists” among the refugees, that it was difficult to integrate “people who have a different tradition and culture” and that it had not even made it to the Roma so far -Integrate minority in the country. At the same time, the government offered the EU Commission to take in 200 Syrian Christians, because Slovakia is "a Christian country, and if you want to integrate people, religion and culture should be similar."

On September 22, 2015, the 28 EU interior ministers decided for the first time by majority vote against votes from Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania to relocate 120,000 refugees from Italy and Greece to the entire EU. On the following day, Slovakia announced that it would challenge the decision legally. On December 2, 2015, Slovakia filed a complaint against the decision with the European Court of Justice. In his press conference, Prime Minister Fico described the quota system as an “absolute fiasco of European politics”. He considers them "nonsensical and technically not feasible". At the same time, the government announced that Slovakia would take in 25 Christian families from Syria in the next few days. This means that the Slovakian capacities are fully utilized.

literature

- Július Bartl, Viliam Čičaj, M. Kohútová, Robert Letz, V. Letz, Dušan Škvarna: Lexicon of Slovak History (original title: Lexikón slovenských dejín ). Slovenské Pedagogické Nakladatelství, Bratislava 2002, ISBN 80-08-02035-0 .

- Simon Gruber: Wild East or Heart of Europe? Slovakia as an EU candidate country in the 1990s (= publications on political communication. Volume 7). V&R Unipress, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-89971-599-6 .

- Hannes Hofbauer , David Noack: Slovakia: The arduous way to the west. Promedia, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-85371-349-5 .

- Stanislav J. Kirschbaum: A history of Slovakia - the struggle for survival. Palgrave, New York 2005, ISBN 978-1-4039-6929-3 .

- Titus Kolnik, Karol Pieta: Slovakia. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 29, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-018360-9 , pp. 114–123. Preview (prehistory and early history of Slovakia up to 500 AD).

- Hans Lemberg , Jörg K. Hoensch (ed.): Studia Slovaca: Studies on the history of the Slovaks and Slovakia. Festschrift for the 65th birthday of Jörg K. Hösch (= publications of the Collegium Carolinum. Volume 93). Oldenbourg, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-486-56521-4 .

- Elena Mannová (Ed.): A Concise History of Slovakia. Bratislava 2000, ISBN 80-88880-42-4 .

- Roland Schönfeld, Horst Glassl , Ekkehard Völkl (eds.): Slovakia - from the Middle Ages to the present. Pustet, Regensburg 2000, ISBN 3-7917-1723-5 .

- Dušan Škvarna u. a., Andrea Koch-Reynolds (translator and ed.), Pavl Žigar (ed.): Slovakia, history, theater, music, language, literature, folk culture, visual arts, Slovaks abroad, film (= Wieser encyclopedia of European Ostens. Vol. 1, 2). Wieser, Klagenfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-85129-886-4 .

Web links

- A detailed timeline up to 1714

- Maps of the historical settlement and the development of the administrative structure of Slovakia. (on the right under "Komozície 2."). (No longer available online.) In: enviroportal.sk. Formerly in the original (Slovak, mementos not meaningful). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- Website of the “Institute for National Remembrance” with information on contemporary history in Slovakia

Individual evidence

- ^ Distribution of Races in Austria-Hungary . In: William R. Shepherd : Historical Atlas . New York 1911.

- ↑ Manfred Alexander (ed.): Small peoples in the history of Eastern Europe. Festschrift for Günther Stökl on his 75th birthday . Verlag Steiner, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-515-05473-1 , p. 80 f.

- ↑ Wolfdieter Bihl : The way to collapse. Austria-Hungary under Charles I (IV.) . In: Erika Weinzierl , Kurt Skalnik (ed.): Austria 1918–1938. History of the First Republic. Volume 1, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1983, pp. 27–54, here p. 44.

- ^ Zdeněk Kárník: National upheavals (and a Bolshevik one) - gravedigger of the monarchy and midwife of the new Central Europe and Czechoslovakia. In: David Schriffl, Niklas Perzi (ed.): Spotlights on the history of the Bohemian countries from the 16th to the 20th century. Selected results from the Austrian-Czech Historians' Days 2006 and 2008. Lit Verlag, Vienna / Münster 2011, ISBN 978-3-643-50386-2 , pp. 145–160, here: p. 175.

-

^ Pieter van Duin, Zuzana Poláčková: Submission, survival, salvation: the political psychology of right-wing populism in post-communist Slovakia. In: Wolfgang Eismann (Ed.): Right-wing populism: Austrian disease or European normality? Czernin Verlag, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7076-0132-3 , p. 131;

Soňa Szomolányi: Spoločnosť a politika na Slovensku: cesty k stabilite 1989–2004 [Society and Politics in Slovakia: Paths to Stability 1989–2004]. Univerzita Komenského, 2005, p. 205;

Christian Boulanger: Review of Kipke, Ruediger; Vodicka, Karel, Slovak Republic: Studies on Political Development. In: Habsburg, h-net.org, July 2001. - ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 91.

-

↑ End of the Hyphenated Federation. In: faz.net, accessed January 2, 2013;

Memories of Meciar. In: faz.net, accessed on January 11, 2013. - ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 94.

- ↑ Vladimír Meciar: From pariah to courted: Comeback despite dark spots. In: derStandard, accessed on January 9, 2013.

- ↑ Kováč: Dejiny, S. 333rd

- ↑ Schönfeld: Slovakia, p. 226.

-

↑ Kováč: Dejiny, pp. 333–334, and Divoké s tajnými službami to bolo za Mečiara. In: sme.sk, accessed January 26, 2013;

Stalin's pupil. In: focus.de, accessed on December 30, 2012. - ^ Repression in Slovakia. Press release: 12-12-96 (2). In: europarl.europa.eu, accessed on December 30, 2012.

- ↑ Hofbauer: Slovakia, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 114.

- ↑ Schönfeld: Slovakia, p. 236 ff.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 92.

- ↑ Kováč: Dejiny, p. 337.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 113.

- ↑ Kováč: Dejiny, p. 338, and Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 145.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 103.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 115.

- ↑ Kováč: Dejiny, p. 338.

- ↑ Hofbauer: Slovakia, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Radoslav Štefančík: Christian-Democratic Parties in Slovakia. P. 61.

- ↑ Wolfgang Gieler (Ed.): Foreign Policy in European Comparison: A Handbook of the States of Europe from AZ. P. 456.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 148.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 170.

- ^ David X. Noack: Slovak foreign policy: vision of a political independence. In: davidnoack.net, accessed January 26, 2013.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 151.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, pp. 152, 154.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 202.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 156.

- ↑ Schönfeld: Slovakia, p. 239.

- ↑ Grigorij Mesežnikov, Oľga Gyárfašová: The Slovak National Party: A fading Comet? On the Ups and Downs of Right-wing and National Populism in Slovakia. In: Karsten Grabow, Florian Hartleb (eds.): Exposing the Demagogues. Right-wing and National Populist Parties in Europe. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung / Center for European Studies, Berlin 2013, pp. 331–334.

- ↑ Hofbauer: Slovakia, pp. 180-182.

- ↑ Fico is the leftmost Prime Minister in Europe. In: davidnoack.net (interview with Ľuboš Blaha on June 14, 2010).

- ↑ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 191.

- ↑ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 191.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 192.

-

^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 193 f .;

Hungarian President Solyom not welcome. In: derstandard.at, August 20, 2009, accessed December 8, 2015. - ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 208.

-

^ Austrian Chamber of Commerce : Country Profile Slovakia. (PDF; 52 kB) (No longer available online.) In: wko.at. Aussenwirtschaft Austria , September 1, 2015, archived from the original on November 20, 2015 ; accessed on October 18, 2018 (no mementos from 2009/2010). Gerit Schulze: Thanks to the auto industry in turbo mode: The Slovak economy. In: bpb.de. Federal Agency for Civic Education , November 13, 2015, accessed on November 30, 2018 (Section Bump Flat Tax ).

- ↑ Guido Glania: The financial sector in Slovakia convinces with stability ( Memento from October 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). In: estandort.com. June 22, 2011, accessed October 18, 2018.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 202.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 204.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 205.

- ↑ Hofbauer: Slovakia, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 197.

- ↑ Country report ROG 2009. In: rog.at, accessed on December 8, 2015.

- ↑ Clear election victory: Gasparovic remains President of Slovakia. In: handelsblatt.com, accessed on January 9, 2013.

- ↑ Hofbauer: Slovakia, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 214.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 215.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 217.

- ^ Hofbauer: Slovakia, p. 219.

- ↑ Stefan Gutbrunner: A Premier as President ( Memento of 12 March 2014 Internet Archive ). In: derstandard.at, March 11, 2014.

- ^ Heads of government of the Czech Republic and Slovakia commemorate the division. In: blick.ch, accessed on January 12, 2013

- ↑ DPA: Political newcomer Kiska becomes President of Slovakia. In: FAZ.net . March 30, 2014, accessed October 13, 2018 .

-

↑ Slovak Prime Minister under fire after criticism of Russia sanctions. In: derstandard.at, August 12, 2014, accessed December 8, 2015;

Slovakia of the Baltic states that they prefer Christian refugees and an EU and the Czech Republic say “Njet” about further sanctions against Russia ( Memento from September 14, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). In : wirtschaftsblatt.at, September 6, 2014, accessed December 8, 2015. -

↑ Slovakia only wants Christian refugees. In: derstandard.at, August 20, 2015, accessed on December 8, 2015;

Slovakia could take even more refugees from Austria. In: kurier.at, August 10, 2015, accessed on December 11, 2015. - ↑ Markus Becker: EU distributes refugees: Then just without consensus. In: spiegel.de, September 22, 2015, accessed December 8, 2015.

- ↑ Refugees: Slovakia announces lawsuit against EU quota resolution. In: diepresse.com, September 23, 2015, accessed December 8, 2015.

- ↑ Slovakia sues against EU refugee distribution. In: diepresse.com, December 2, 2015, accessed December 8, 2015.

- ↑ Slovakia accepts 25 refugee families. In: de.rsi.rtvs.sk, December 1, 2015, accessed on December 11, 2015.