History of philosophy

The history of philosophy has the development of theoretical reflection on the world and the principles ruling in it from the beginning of European philosophy in ancient Greece in the 6th century BC. Chr. To the present to the subject. As a philosophical discipline, the historiography of philosophy takes an interpreting position on the historical drafts, tries to understand them in their respective context and examines whether and to what extent lessons can be drawn from them for the present. The theory of the history of philosophy examines methods , categories and significance of the historical approach to philosophy.

It is one of the peculiarities of philosophy that in the course of its history it has repeatedly produced fundamentally new explanatory models for its own perennial questions about the recognizable , about correct action or the meaning of life . In doing so, philosophers have to adapt their answers to the knowledge of the science and to use their current state of knowledge to explain the world. The story of the answers always flows into the current explanations. This systematic difference to the sciences explains the special interest of philosophy in its own history of ideas .

Types of history reference

Different aspects can be considered as "types of historical reference" to clarify the historical self-image, which fulfill different functions:

- The collation of the life data, works and conceptions of the philosophers of the past enables an overview of the already existing thinking and the emergence of today's positions (history of ideas as historical reality - res gestae, information function).

- By arranging and recognizing systematic connections, concepts and basic ideas are clarified (conceptual history, fund of existing arguments).

- You can find the questions asked again and again in the course of the history of philosophy and the different answers given to them (problem history, relativization of individual positions).

- One can try to determine whether there is progress in the history of philosophy , something like a goal-oriented development (philosophy of history, question of truth and validity).

- In a self- examination, methods and forms of the history of philosophy are examined in their historical development (history of the history of philosophy as “memory reflection - historia rerum gestarum”).

History of philosophy can be approached in a person-oriented , work -oriented or problem-oriented manner . Another approach consists in the division into major epochs , whereby the essential people with their essential works and their answers to the essential questions are worked out. As far as the respective historians of philosophy provide their own interpretation, it is necessary to use alternative representations and in particular also the original scripts in order to be able to make their own assessment. Dealing with the history of philosophy can, depending on the intended function, take place in various forms, such as documentary, polemical , topical , narrative , argumentative or hermeneutical .

The benefit of the history of philosophy

The task of philosophy is very different from that in the positive sciences, be it natural sciences or humanities and social sciences, in which knowledge is gradually accumulated, corrected and continuously replaced by better, more differentiated or fundamentally new theories. Philosophy, on the other hand, tries to give answers to very general questions with which the connections in the world can be explained. Immanuel Kant's questions are famous : What can I know? What should I do? What can I hope for? what is the human? ( KrV B 833; Lectures on Logic VIII) These or all of the questions derived from them arise over and over again in the course of history, because social conditions, but also knowledge of nature, continue to develop. One therefore speaks of a Philosophia perennis , an everlasting philosophy. Hegel believed that philosophy takes its time in thought. Because the old questions persist and have at best been differentiated and systematized over time, it seems that there is no progress in philosophy. In this sense, Whitehead's statement is often quoted that the entire history of European philosophy consists only of footnotes to Plato. Whitehead, however, only wanted to emphasize the wealth of ideas of Plato without damaging his successors. Kant even spoke of “groping around” and of philosophical “nomads” (KrV B VII), because the debate has been dominated by diverse, often contradicting and contradicting views throughout history. Ulrich Johannes Schneider speaks of a “tangle of legends” The inventory of Wilhelm Dilthey is drastic : “The diversity of philosophical systems lies behind us in a chaotic, boundless manner [...] we look back on an immeasurable rubble field of religious traditions, metaphysical assertions, demonstrated systems: The human spirit has tried and tested all kinds of possibilities for many centuries, and methodical, critical historical research explores every fragment, every remnant of this long work of our sex. One of these systems excludes the other, one refutes the other, none can prove itself. "

The fundamental question arises as to the usefulness of dealing with the history of philosophy. One could try, with the help of a canon to be updated, to derive the questions directly from the knowledge of the present and to summarize the answers in a compendium, which takes into account a renewal according to the progress of the sciences through respective new editions. With such an approach, however, one would forego access to the many clever answers that earlier philosophers had already worked out. The basis of experience of philosophy does not lie in empirical facts, but in the theories developed in its history. Above all, one would ignore the fact that one can only approach the full content of a question in the broad discourse of philosophers. Every philosophical theory must critically differentiate itself from alternative theories and this also includes the relevant theories of the past. The essence of Kant's answers to his questions is that people are limited in their abilities and that philosophical questions are constantly being asked anew.

There are philosophers like Karl Jaspers who view the examination of historical positions as an intellectual conversation that promotes one's own thinking. Only in this way - according to Hans Georg Gadamer - is it possible for a “truth to be recognized that cannot be reached in any other way.” The discussion with the great thinkers itself becomes a “way of philosophizing”. Similarly, Whitehead emphasized that precisely this Discrepancies and unresolved questions from past positions provide approaches for the further development of new theories and speculations . This is precisely where the engine of progress lies. Others, like Hegel, see the history of philosophy as a development of thought so that one can only understand contemporary thinking if one understands how it came about. Only then can one develop principles and guiding ideas that are also systematically fundamental for the answers of philosophy. Here the examination of the history of philosophy becomes an original philosophizing and not just the reproduction of historical doctrines ( doxography ). Accordingly, Wolfgang Röd calls for a “philosophizing history of philosophy”. The narration of the story is then no longer based solely on documentary, but also on conceptual evidence that underlies the interpretation of the philosophizing historian. Arthur Schopenhauer , on the other hand, thought that access to the history of philosophy based on its presentation by philosophy professors made little sense, because it would shorten and distort the content. “Instead of reading the philosophers' own works of all kinds of presentations of their teachings, or even reading the history of philosophy, it is like letting someone else chew your food.” Instead of a presentation, a collection of important text excerpts would be much more helpful. Only by studying the original writings can one really approach the thinking of historical models. Schopenhauer then emphasized that his remarks represent one's own thinking based on studying original works. This view was also emphasized by Fritz Mauthner : “The two circumstances that do not allow a serious history of philosophy relate to the fixed standpoint of the performer and to the unrepresentability of what is being represented. As if a photographer wanted to bring the air movement onto the plate, but had no tripod for his apparatus and no plate sensitive to the air. "

On the other hand, there is the view that the essential and lasting must be found in the history of philosophy. Martin Heidegger commented: "No matter how diligently we scrape together what previous people have already said, it doesn't help us if we don't muster the strength of the simplicity of the essence." Nicolai Hartmann , who, however, considered pure historiography to be worthless, agreed Regarding: “What we need is the historian who is also a systematic at the height of his time - the historian who knows about the task of recognition and has the prerequisite for systematic contact with the problems.” Victor Kraft countered this denied that dealing with the history of philosophy can bring any substantial profit at all: “So now a large part of philosophy as it is taught publicly consists in overviews of its own past. And these now almost without exception offer this same picture. Thinker after thinker appears on the stage, everyone is presented in a loving, accompanying presentation, one stands entirely on one's point of view, builds metaphysics with the metaphysician, becomes skeptical with the skeptic and critical with the critic, and when the abundance of figures has passed is, there is not a building there, big and huge, on which they all worked, but only the memory of their dichotomy, and their incompatibility and confusing abundance. ” Instead, Vittorio Hösle calls for“ a middle ground between a philosophy without that Awareness of one's own historicity and a history of philosophy sinking into erudition without a systematic perspective ”. Hösle opposes all varieties of relativism , be it historicism , pluralism or skepticism . Every position, even a relativistic one, can only be put forward seriously in the end if it makes a claim to truth. “The fact that truth must be possible in spite of historicity has been shown to be a condition for the possibility of any theory. Self-teleology is therefore necessary for every philosophy. "

Friedrich Nietzsche , for whom the discussion of antiquity was the starting point for philosophical thought as a philologist, dealt extensively with the meaning of the history of philosophy in his early work On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life . Nietzsche's relationship to the history of philosophy was ambivalent. On the one hand, it enables insights: “Now philosophical systems are only completely true for their founders: for all later philosophers usually a big mistake, for the weaker minds a sum of mistakes and truths. In any case, as the highest goal, it is an error, and insofar reprehensible. This is why many people disapprove of every philosopher because his goal is not theirs; it is the distant ones. Those who, on the other hand, enjoy great people at all, enjoy such systems, even if they are quite mistaken: they have a point about them that is completely irrefutable, a personal mood, color, you can use them to do that To gain an image of the philosopher: how one can infer the ground from a plant in one place. ”On the other hand, it is dangerous to force the past into a corset with mental constructions and thus create“ web of concepts ”:“ Reaching for them, he thinks [ the educated] to have philosophy, to look for them, he climbs around on the so-called history of philosophy - and when he has finally gathered and piled up a whole cloud of such abstractions and templates - it may come across to him that a true thinker gets in his way and blows it away. "

Access to philosophy through history was also problematic for Henri Bergson . The philosopher gains access to the truth through his philosophical intuition . This knowledge from intuition, the simple and deep basic idea, is what survives all contemporary historical perspectives. “We are certainly not entirely wrong, because a philosophy is more like an organism than an agglomerate. [...] But apart from the fact that this new comparison ascribes a greater continuity to the history of thought than is actually inherent in it, it is also inappropriate in that it directs our attention to the external complication of the system and to what is in its superficial Form appears derivable instead of letting the novelty and simplicity of the ground emerge. "

Approaches to the history of philosophy

Orientation towards your own thinking

Dealing with one's own history has a long tradition in philosophy itself. Aristotle's metaphysics already contained detailed explanations of the ideas of his predecessors. It is obvious that Aristotle was not interested in a philological reappraisal. He wasn't a historian. Rather, he used the traditions as the foundation of his own thought structure and one gets the impression that all thinking before him tends towards his own philosophy, which thus becomes the further development of the previous philosophy and its climax. For Aristotle, dealing with the history of philosophy means its interpretation and transformation. It is a first concept to think of the history of philosophy as progress. Even Kant's endeavor, with his critical approach in the critique of pure reason , to reject dogmatism and skepticism and to find a middle way between empiricism and rationalism , is based on a developmental thinking towards one's own philosophy. "Hegel's conceptual virtuosity was shown not least in writing the history of philosophy as a whole in such a way that it can be understood as a universal learning process leading to Hegel's own system," said Jürgen Habermas . Jaspers, too, criticized the fact that Hegel had partly left out "what was of particular importance to other thinkers".

Aristotle also used the teachings of his predecessors in the sense of a modern topology for the phenomenological understanding of the field of problems, ideas and arguments, which from his point of view needed to be freed from errors or further developed. Corresponding dialectical introductions to a topic can be found in Physics I on the number and nature of principles, in Physics IV on time, in De anima on the soul and in Metaphysics A on the analysis of causes. In Plato there is an overview of past positions only in the Sophistes (241b - 247d) with regard to the number and nature of beings .

A very similar approach can be found in the 20th century with Martin Heidegger or Whitehead, who used process and reality specific ideas of a certain group of great philosophers (Plato, Aristotle, Newton, Locke , Leibniz, Hume and Kant) as a mirror for the development of his own Thought took advantage. Similarly, Kant was an important source of ideas for Charles S. Peirce , although he developed his own positions. Heidegger in particular used history in a negative sense, using metaphysics and its great historical representatives as a starting point for developing his own critical thoughts. The metaphysical concepts were for him "stages of progressive oblivion of being ", which he linked back to the origins of the thought of being in Parmenides and Heraclitus . Heidegger evaded the claim to hermeneutically merely reproduce historical positions, but used Plato, Aristotle, Kant or Hegel to develop his own question. "[...]; understand. that means not just taking note of what has been understood, but repeating what has been understood in the sense of the most specific situation and for this originally . […] Understanding exemplary setting, who is concerned with oneself, will fundamentally place the role models in the sharpest criticism and develop them into possible fruitful opposition. ”Similarly, the lectures on the history of moral philosophy by John Rawls are a critical examination of the positions von Hume, Leibniz, Kant and Hegel with regard to their own concept of a theory of justice . However, subjective distortions can also be problematic, according to Nicolai Hartmann : “ Eduard v. Hartmann in his 'History of Metaphysics', like Natorp in his interpretation of Descartes, Plato, Kant and others. a .; the former searches the whole of history for the 'unconscious'; the latter turns the great thinkers of the past into incomplete neo-Kantians. That was rightly reprimanded and fought. ”There are countless relatively short, one- or two-volume introductions to the history of philosophy. There are two reasons for this. On the one hand, philosophers summarize their own engagement with history here. On the other hand, they are the material that philosophers use to introduce their own students to philosophical thinking. The classics include the writings of Ernst von Aster and Wilhelm Windelband , but also Bertrand Russell's Philosophy of the West . What they have in common is that in their portrayal the story becomes an interlocking thought development. Kurt Wuchterl and Kurt Flasch, on the other hand, point out that the history of philosophy is also the site of diverse controversies and unsolved problems. Similarly, Kant already described metaphysics as the “battleground of endless disputes” or as the “stage of contention”. Nicholas Rescher speaks of the "dispute of the systems" and Franz Kröner viewed the confusing diversity as "the anarchy of philosophical systems".

The way of reason

Giambattista Vico designed a new perspective on history in general in the “Scienza nuova” with the thesis that God's providence is reflected not only in nature, but also in the political world as the world of the intersubjective spirit. The omnipotence of God is to be regarded as immanent in the world, so that there is no break in the causal order. Vico interpreted the history of human culture as "a gradual coming to itself" of reason. In this perspective, history is not accidental ( contingent ), but has a direction, a goal ( telos ) of development. Thinking about history becomes a philosophy of history .

In this sense - but without a theological justification - Immanuel Kant also saw an intention of nature as the driving force in history, whereby the cultural world - despite all recurring setbacks - is on the way to a reasonable "world class", according to Kant's historical-philosophical view in the “ Idea for a general story with cosmopolitan intent ” . The bearer of this general "reason developing from concepts" is not the individual, but the species. The teleological goal of history is the regulative idea of a republican state in perpetual peace. Purposes of nature cannot be grasped empirically, but can only be formulated in a morally practical manner. With regard to the history of philosophy in particular, one has to go back to Kant's estate. He distinguished the historical history of philosophy as a narrative of empirically comprehensible material from the rational, which is a priori possible. "For even though it sets up facts of reason [that is, it cannot be proven], it does not borrow them from the narrative of history, but rather draws them from the nature of human reason as philosophical archeology." The problem for Kant is that the finite reason of the People cannot recognize the absolute, and therefore no one knows with certainty to what extent the practical ideas are approximated to the “supersensible” [God, the “transcendent”, the “absolute”]. “Philosophy is to be seen here as a genius of reason, from whom one demands to know what he was supposed to teach, etc. whether he has achieved it. ”Kant was critical of pure historiography, at least it was no way for him to philosophize itself:“ There are scholars for whom the history of philosophy […] itself is their philosophy, for whom contemporary prolegomena are not written . They must wait until those who try to draw from the sources of reason themselves have settled their cause, and then it will be their turn to give news of what has happened to the world. "Pure retelling is for ( the late) Kant unproductive. Only the philosophical discussion makes it possible to grasp the actual rational content. But this requires an already existing philosophical knowledge. “A history of philosophy is of such a special kind that it cannot be told about it without knowing beforehand what should have happened, and consequently what can happen.” The own critical philosophy becomes the standard of the philosophy historian. For Hermann Lübbe, Kant was the first thinker to understand reason “as the product of its own genesis”.

Knowledge is not everything - this is the short form of the Romantics' critique of the Enlightenment. Reason is a dimension that the wholeness of the world cannot describe on its own. One cannot grasp the story correctly if one does not encounter it poetically and intuitively and also tries to empathize with the emotional world of the observed time. The concentration on the rational misses the organic, which was already thematized by Plato in the Phaedo (70e ff) as a cycle of becoming and passing away in a historical culture. These thoughts brought into the debate by Hamann ( Socratic Memories ) and Herder ( Also a Philosophy of History for the Education of Humanity ) were taken up in Romanticism and, along with others, reworded by Novalis ( Pollen ) and Schlegel .

- “If history is the only science, one might ask, how does philosophy relate to it? Philosophy itself must be historical in spirit, its way of thinking and imagining must be everywhere genetic and synthetic; this is also the goal that we set ourselves in our investigation. "

Schlegel supplemented the concept of becoming, an organic history of philosophy, with the idea of the cycle:

- “Philosophically, one can set up as a general law for history that the individual developments form opposites according to the law of jumping into the opposite that applies to them, disintegrate into epochs, periods, but the whole of the development forms a cycle, returns to the beginning; a law that is applicable only to totalities. "

Just like the Romantics, Schelling assumed an organic development in the history of philosophy. He also emphasized the unity of philosophy that is formed from the various systems. While Kant analyzed reason as a structure, Schelling viewed it as a never-ending development process in which the individual philosophical systems participate. Philosophy becomes a living science, constantly creating new, interlocking forms. Philosophy as a whole itself forms a coherent system: “The system that is to serve as the center of a history of philosophy must itself be capable of development. There must be an organizing spirit in him. ”For Schelling, however, history was only one way of accessing philosophy. The philosophy of nature stands in the same right, and both are to be supplemented by a philosophy of art in which nature and freedom come together.

Hegel, too, viewed the history of philosophy not as a collection of accidental opinions, but as a necessary context. The aim of the story is the development of reason and freedom. For Hegel, dealing with the history of philosophy is a process of reason's self-knowledge. In contrast to Kant, Hegel assigned history to an objective reality because reason, as the expression of the absolute, and reality form a unity for him. Only in this way does history have a power to guide knowledge.

- “The deeds of the history of philosophy are not adventures - just as world history is not only romantic - not just a collection of coincidental incidents, journeys by erring knights who struggle for themselves, struggle without purpose and whose effectiveness has disappeared without a trace.

- Just as little has one worked out something here, there another at will, but in the movement of the thinking spirit there is essential connection. It is sensible. With this belief in the world spirit, we must go to history and especially to the history of philosophy. "

For Hegel, the history of philosophy is the development of the world spirit as it comes to itself in the present. History is not to be thought of as the past, but as an image of the past in the present. In thinking, the absolute mind absorbs the past systems. "The development of the spirit is going out, laying apart and at the same time coming together." The historical development goes into the systematic understanding of the philosophical questions and is here united to a present picture of the truth, which is not itself historical. “The idea is then also the true and only the true. The essential thing is now the nature of the idea to develop and only through the development to grasp itself, to become what it is. ”The development thought turns the history of philosophy into philosophy itself, because this“ is now knowledge for itself of this development and, as comprehending thinking, is itself this thinking development. The further this development progressed, the more perfect the philosophy. ”Hegel thus emphasizes the progress of philosophy on the way to truth in a systematic (dialectical) development. The concrete factual history of philosophy is a historical expression, how the even timeless philosophy was brought to the concept in its respective time. Dialectics requires the insight that every philosophy necessarily presupposes its predecessor. Philosophy is expressed as a whole in its history. It is "an organic system, a totality, which contains a wealth of levels and moments in itself."

The historicism saw itself as a countermovement to romanticism and idealism. With the sole norm of recording historical events in a “value-free” manner, a philosophical metatheory was dispensed with. Historical judgments should be impartial and without preconditions based exclusively on empirical factuality. When Johann Gustav Droysen , this "realistic" methodology combined with the hermeneutics of Schleiermacher . Kant and Hegel wanted to show how their (each different) concept of "true philosophy" was realized historically. History seeks the general, the structural features, in history and thus concentrates on the empirically given, against which historical narration must prove itself. Historiography is an understanding look at what has been uncovered by scientific means. At the same time, philosophy also requires an understanding of history, according to Friedrich Schleiermacher:

- "Because whoever presents the history of philosophy must possess philosophy in order to be able to sort out the individual facts that belong to it, and whoever wants to possess philosophy must understand it historically."

This conception of the relationship between philosophy and history extends into the 20th century, when the prominent historian of philosophy Eduard Zeller advocated the thesis “that only he who fully understands the history of philosophy who has the perfect philosophy and only who comes to true philosophy, which the understanding of history leads to her. "

Michel Foucault's view of history is also completely directed against Hegel and Kant , who contributed to the “destruction of the great narratives” ( Lyotard ) in the sense of postmodernism , but did not see himself as postmodern. Foucault, who took over the term “archeology” from Kant, but filled it with a completely different content, denied the existence of a timeless reason and emphasized that there are only historically conditioned forms of rationality in history. He emphasized that philosophers always depend on the thinking of their time and the historically contingent background. Accordingly, Foucault advocated a history of philosophy as a case-related institutional history and emphasized the radical discontinuities in the historical process.

Richard Rorty sees four traditional approaches to the history of philosophy.

- (1) Many analytical philosophers try to treat great philosophers as contemporaries and formulate their texts in such a way that they can be included as arguments in current debates. These rational reconstructions are often accused of anachronism . Because with this concept the questions to the historical text are asked from the perspective of the interpreter, the answers also depend on his point of view. The dead are, as it were, reeducated.

- (2) In the historical reconstruction, the interpreter tries to understand the protagonist , his terminology and his historical context. Here, according to Rorty, one can learn above all that there were other forms and conditions of spiritual life than in the present. If one tries to use modern knowledge as a yardstick for interpretation within this framework, this runs the risk of self-justification. You develop a feeling of superiority when you try to point out the mistakes of the predecessors in order to substantiate your own position.

- (3) In the history of philosophy as a history of ideas, the focus is less on individual philosophical questions and more on the overall work of a philosopher. Rorty cites Hegel, Heidegger, Reichenbach , Foucault , Blumenberg and McIntyre as examples of such a history of philosophy . This approach is less about the solution of specific problems than about the question of the correct formulation of the problem, about the evaluation of a specific philosophical position. Who was a great philosopher and what did he do to solve the problems of philosophy? Is z. B. Is the question of the existence of God an important, interesting or even a meaningful question for philosophy? Insofar as the historian of philosophy takes a position on these questions, there is again a self-justification of his own view. A fundamental problem of such historiography is the canon that arises and leads to the fact that the vocabulary of the different epochs must be given the same name.

- (4) Rorty regards doxography as particularly questionable in the history of philosophy, for example in the form of representations of thoughts from Thales to Wittgenstein. Most of the thinkers depicted are deprived of their intellectual content through foreshortening. By repeatedly presenting the same "main problems of philosophy" across the ages, trying to make Leibniz and Hegel, Nietzsche and Mill the same, by presenting their epistemology, their religious philosophy or their moral philosophy, the ideas of the thinkers become , its meaning for one's own time as well as for intellectual history is not grasped in depth, but rather distorted. For Rorty, philosophy is not a “natural way” that poses certain questions on its own. It has no fixed methodological or conceptual structures, but is contingent . It is (with Hegel and Dewey) the grasping of the thoughts of the respective time. The history of doxographic philosophy can only convey something meaningful if it is limited to the context of an epoch, to a few contiguous centuries, and thus comes close to the form of historical reconstruction.

Against the traditional forms of the history of philosophy, Rorty sets the "intellectual history", a procedure that is more complex and demanding for him. It consists of descriptions of what the intellectuals of a time were aiming for, and includes the sociological, economic, political and cultural framework of the epoch. As examples, Rorty cites topics such as "The rise of the English working class" or "The moral philosophy in Harvard in the 17th century". In this way, living conditions and options for action in a certain social area are illuminated and made comprehensible. Explanations can then interact with the analysis of contemporary conditions without being restricted by a predetermined canon. Good studies of this kind are a prerequisite for recognizing which philosophers are particularly suitable to be regarded as heroes of the history of philosophy and which topics deserve the honorary title of a philosophical problem. They are as much the basis of a good rational or historical reconstruction as a balanced intellectual history. Despite his critical stance towards traditional philosophical historiography, Rorty thinks it makes sense:

- “I am definitely in favor of abolishing canonical rules that only seem strange, but I don't think that we can do without canonical rules. The reason for this is that we cannot do without heroes. We need mountain peaks to look up to. We need to tell detailed stories of the great dead to one another to give concrete shape to our hopes of getting further than them. We also need the idea that there is such a thing as "philosophy" in the sense of the honorary title, that is, the idea that there are questions that - if only we were smart enough to ask them - everyone should have always been asking . We cannot give up the idea without at the same time giving up the idea that the intellectuals of the previous European historical epochs form a community to which it is an advantage to belong. "

History of philosophy

Antiquity

Overall, the history of the processing of doctrines and biographies of earlier philosophers goes back to antiquity. The first known account of pre-Socratic philosophy can be found in Hippias von Elis in the 5th century BC. Systematic collections of earlier doctrinal opinions emerged in Peripatos , the school of Aristotle, primarily initiated by Theophrastus , which Hermann Diels prepared and published as " Doxographi graeci " (Greek textbooks). A rather uncritical collation of sources geared towards collecting earlier works can be found in Diogenes Laertios ( Life and Opinions of Famous Philosophers ), who filled their biographies with anecdotes . Since the work contains many excerpts and quotations, it is an important building block in knowledge of ancient thought despite all methodological inadequacies. Many representations of the history of philosophy in the Middle Ages and the early modern period fall back on it or are merely compilations of it, such as Walter Burley's Liber de vita et moribus philosophorum (Book of the Life and Morals of Philosophers, beginning of the 14th century). Also important for tradition is the work of Cicero , who made historical considerations in various writings ( Academica : first principles, De natura deorum : concept of God, De finibus : representation of the four great schools). In particular, in the context of his translations, Cicero created important foundations for the Latin philosophical vocabulary. Important predecessors of Diogenes were Plutarch and Sextus Empiricus . Another source is Flavius Philostratos , whose writings have been evaluated by Eunapios of Sardis, among others .

Many of the ancient writings that are reported on have been lost and could only be reconstructed in fragments from other sources. The works of Plato and Aristotle are only available in parts. Some authors like Democritus have remained almost entirely unknown, although an extensive work is reported. While Augustine's writings have survived, there is hardly any original material from his Pelagian adversary Julian . This leads to gaps in reception, which is why the picture of the ways of thinking of the historical epoch must remain incomplete and distorted.

middle Ages

The sources of original texts by authors on medieval philosophy are significantly more extensive than those in antiquity, if not complete. The processing of these materials began in the early modern period, but has not yet been completed. For example, Martin Heidegger wrote his doctorate on a script that was ascribed to Johannes Duns Scotus in his time , but is now considered a script by Thomas von Erfurt . The critical edition on Scotus began in 1950 and was laid out in 100 volumes, of which only a part is available 60 years later. Years ago, historians and interpreters often still worked with the Opera Omnia , the “Wadding Edition” from 1639, which was fraught with errors.

In the meantime Kurt Flasch has made a philologically and philosophically competent research contribution with his original texts published in 1982 and 1986 and translated into German and his presentation of medieval philosophy. These publications also enable self-taught people to study medieval philosophizing themselves. Flasch would like that "the texts of the medieval thinkers ... as documents of their engagement with real experiences ..." are read. A research overview of the 19th and partly 20th centuries on the philosophy of the Middle Ages can be found in Karl Vorländer.

enlightenment

The modern, empirical-scientific form of historical processing of early writings only began in the Enlightenment . It is the beginning of the critical self-reflection of philosophical historians on their subject. A starting point for critical thinking is the Dictionnaire historique et critique published by Pierre Bayle between 1695 and 1702 . Regarding the present representations, with specific reference to a mistake he found in Plutarch, Bayles said: “So this is the wretched state in which the so much vaunted ancients left the history of philosophy behind. A thousand contradictions everywhere, a thousand incompatible facts, a thousand incorrect dates. ” Jakob Brucker is considered the founder of modern philosophical historiography , whose “ Historia Critica Philosophiae ”had a strong influence on Diderot and the Encyclopédie . The "Acta Philosophorum, which is: Thorough news from the Historia Philosophica, together with appended judgments of the old and new books belonging to it" appeared even earlier by Christoph August Heumann from 1715 to 1727 without any reference to the authors . This emphasized the importance of the critical method and formulated reflections on the subject area of philosophy. In addition to the philological preparation of the material, which must be carried out with great precision, Heumann called for a philosophical criticism, with which, on the one hand, errors in tradition can be discovered and, on the other hand, implausibilities of the sources can be revealed. In his work, the historian of philosophy changes from a collector and chronicler of the history of philosophy to a reflective philosophical interpreter .

Brucker, who referred to both Bayle and Heumann, presented a monumental work with several multi-volume writings, one of which was over 9,000 pages in 7 volumes (" Brief Questions from the Philosophical History ", 1731) and another over 7,000 pages in five volumes (" Historica critica philosophiae ", 1742), where he expanded subsequent editions. The special thing about his work is that he no longer strung historical things together, but tried to show connections and effects within and between the various positions. In doing so, he viewed philosophical knowledge as part of the cultural knowledge of a society that individual philosophers had produced. For a long time, Brucker's writings were considered to be the fundamental work on the history of philosophy and were used by many to study the history of philosophy from Goethe to Kant and Hegel to Schopenhauer. Hegel considered the distortions that had arisen during the structuring of the material by Brucker to be "sealing" and called "the representation in the highest degree impure".

In the second half of the 18th century, the idea of progress in history gained importance. The detachment of thought from the idea of an order directed by God opened the view to the subject and the question of how man became what he is. Questions of anthropology were raised and cultural development became an issue. Herder wrote the " Idea for the Philosophy of Human History ". In the early Enlightenment, Heumann and Brucker tried to explain how the history of thought produces an ever clearer picture of the truth . The philosophers of the Renaissance had their eyes on the past and saw their ideal in antiquity. With the reversal of the direction of view through the progressive thinking of the Enlightenment, history was interpreted as a way of perfection. The past was now given the status of something less perfect, less enlightened and therefore darker. Turgot used the epoch scheme of theological, metaphysical and finally scientific thought, which is later found in Auguste Comte as the three-stage law . This idea of progress also shaped the descriptions of the history of philosophy by Joseph Marie Degérando and Dietrich Tiedemann , in which philosophy was only part of a development of humanity, part of a more comprehensive universal history. The works of Christoph Meiners and Christian Garve were in the same line. At the same time, many authors of this time addressed popular topics in the fashionable journals to a broader public beyond the university in the spirit of enlightenment.

A look at progress had also raised the question of the origin, which can be found in various longitudinal sections with investigations into the origin of language, the development of the concept of God , the idea of truth and the like. on followed. Garve stressed the problem of changing meanings of terms and called for the use of authentic sources so that the meaning of what is depicted is properly grasped. Meiners emphasized the importance of including source criticism in historiography. Tiedemann focused on the new and rejected (against the Kantians) any notion that there could be something final in philosophy. The historian of philosophy should “make the progress of reason perceptible and show the relative perfection of the systems.” The greatness of philosophers arises from the extent to which they contribute to progress and have an effect on their successors. It is no longer primarily about the representation of what has been, but about the assessment of the material, its content-related precision and coherence, the evaluation of its effects and its position in history as a continuity or break with the past. For this purpose, the influences of earlier philosophers on the respective position must also be presented. Furthermore, the thought developments of the respective philosopher are to be included in order to better understand the origin of a thought.

According to Kant

The philosophical historians, building on Kant's considerations, sought the systematic, the operative principles of reason in the history of philosophy. For Georg Gustav Fülleborn , the truth unfolds step by step in the story. “I do not deny that the general laws of thought have always existed in man as they are today, and that they will remain just as unchangeable: but it does not follow from this that the application of the same to objects and relationships does not apply changes, that is, should either widen or narrow. Newton did not think according to any other forms and laws, like Tycho de Brahe , but he made discoveries that the latter did not suspect. ”The history of philosophy must deal in particular with the methods in which reason is expressed. Fülleborn took up Kant's distinction between dogmatic, skeptical and critical philosophy and called for the "spirit of a philosophy" to be represented. Johann Christian August Grohmann referred to the tensions between the two concepts of constantly changing empirical history (quid facti) and theoretical philosophy (quid iuris), which is aimed at the discovery of the unchangeable principles of reason. It is essential that the sequence of thinking has its own regularity, an inner logic that does not follow the physical causal order and can still be recognized. For Grohmann, however, this also meant the end of the history of philosophy; for by recognizing what is reasonable in history from a priori generally applicable principles, there can be no logical further development beyond this. "The history of philosophy shows how and where there is rest and standstill of all systems, so that no more come, no more can arise, and that if in future times there is still a dispute about philosophy, it is only about old systems, about what has already been there, since any new material is missing. ”In the judgment about the finality of knowledge, Grohmann erred, like Kant with regard to the laws of the natural sciences, who assumed that Newton had found final laws of physics so that one can formulate a metaphysics of the natural sciences based on it. However, if one takes the critical method, the question of the conditions of the possibility of knowledge and the limits of reason, as the fundamental Kantian principle, then this standard has survived into contemporary philosophy. From the conception of the history of philosophy as self-knowledge of reason, which has its ultimate point of reference in itself, Grohmann formulated a claim that also became effective in Hegel's philosophy of history.

Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann interpreted Kant less radically and did not consider it appropriate to look for a system in history. Rather, according to his view, it is important to show how the historical movement approaches the found philosophical systematics. If one regards critical philosophy as a goal, the analysis of the history of philosophy yields an orientation that Brucker and Tiedemann still lacked. The assessment of history results in a point of view, a guide for what is philosophically possible and what was wrongly thought in earlier systems, what from today's point of view no longer has any meaning or is still missing. The presentation of the history of philosophy can accordingly dispense with minor matters. The prerequisite for this is that the historian of philosophy thinks as a philosopher. Tennemann was concerned with a "representation of the successive development of philosophy or representation of the efforts of reason to realize the idea of science of the ultimate reasons and laws of nature and freedom." To adequately grasp the content, the form, the inner context (the spirit), the architecture and the purposes of the historical object. This also includes the endeavor to be as authentic as possible, which takes into account what the author “was able to achieve at that time according to the level of culture”. Schleiermacher's hermeneutics can already be heard here . Because Tennemann analyzed and prepared his material using a new system, he advocated leaving past interpretations aside as possible and dealing with the original texts. His reason-oriented philosophical approach corresponded to the need for a philosophical science determined by its object and its methods, which on the one hand has as its object what holds the world together - metaphysics - and on the other hand nature - natural science - and finally the people - ethics and aesthetics. As a scientist, the historian of philosophy knows his subject, its sources and their nature and knows how to judge them. Other early Kantian philosophical historians include Johann Gottlieb Buhle , Wilhelm Traugott Krug and Friedrich August Carus .

Like criticism, the philosophical currents that followed it found their expression in the history of philosophy. Carl Friedrich Bachmann and Friedrich Ast in particular emerged as representatives of Romanticism . In his description of the history of philosophy, Ast followed Schlegel above all as an organic development. Against the analytical self-limitation of the Kantians to reason, he demanded: “Therefore, true history must be permeated with speculation in order to represent the true life of things; Speculations and empiricism must combine to form a life. ”He also implements Schlegel's idea of an eternal cycle:“ So the life of mankind is a cycle that is always the same and always re-opening, an eternal emergence, revelation and a Eternal flowing back, dissolving. ”Bachmann's dissertation dealt with“ On Tennemann's mistakes in the history of philosophy ”. One of the differences was that Bachmann (like Ast) did not locate the origin of philosophy in the Greeks, but in oriental mythology . Furthermore, he paralleled the history of nature and the history of the mind. At the same time, he incorporated concepts from Fichte and Hegel, whom he had heard himself, into his philosophical-historical thoughts. So he set up a dialectical scheme for classifying the respective historical concepts:

- "Thesis: Nature and things outside of us are and they are in themselves, A = A." (Thales, p. 71)

- "Antithesis: Things are only insofar as they are not, insofar as they are posited as canceled, they are only through something else." (Anaxagoras, Fichte, p. 72)

- "Synthesis: both nature and the I are not in themselves, they are just different expressions of the same being, the identity of both." (Pythagoras, Plato, Schelling, p. 73)

Hegel is not mentioned in this scheme. However, according to Geldsetzer, Bachmann's basic insight could have been formulated by Hegel.

- “The history of philosophy appears to us as a big whole, as an infinite evolution, as the history of formation of the absolute spirit that has passed through thousands of years; of the emancipating, in this emptying nature outside of itself, but then recognizing as its own essence. "(p. 73)

Anselm Rixner also succeeded Hegel and Schelling . Fichte's philosophy finds its counterpart z. B. with August Ludwig Hülsen , who described history as a productive development of contradictions and conflicts, which are inherent in a dialectical dynamic. Dealing with history leads people to themselves. Only through this do they grasp what they have become, their historicity. “Reason as reason cannot at all other than go back to the past and seek out oneself. Only in this way does it receive its specific point of view, because it learns to understand the human being, how he emerged through all the stages of his becoming to eternal Dasyen. "

Christian August Brandis was one of the first to follow Schleiermacher's hermeneutic school . According to his view, “philosophy pursues an indefinite manifold in order to show the highest manifold in it.” Its proximity to the emerging historicism is shown in the rejection of a unified idea of philosophy. Instead, he saw "only contemporary philosophy terms". Then it is the task of the historian of philosophy to show the areas and methods worked on, but to present the content itself in its historical context. Brandis attached particular importance to etymological and historical language analysis. Heinrich Ritter , also a student of Schleiermacher and at the same time editor of his posthumous writings, was even more important as a philosophy historian. The history of philosophy served him as an education and as a gateway to understanding life. With this aspect, Ritter already pointed to the later life-philosophical influences of Dilthey .

- “The life which is to be grasped in the history of philosophy is the life of science in those who are dedicated to it; the philosophical knowledge of these should therefore be recognized through the similarity that takes place in us, or through the knowledge that they themselves have. "

It was only in historicism that the form developed that has become the object and content of the modern history of philosophy. The focus is on the reconstruction of the original material. However, it is important to be aware that the reception depends essentially on who prepares, translates and summarizes the relevant texts in a philological way, because they are already aligned and interpreted. An outstanding example of this approach to the history of philosophy is that of Friedrich Ueberweg begun monumental work plan of the history of philosophy that a philological professional, fact-rich as possible Doxografie aims. As a counterpart to this will appear in the same publishing house from Rudolf Eisler philosophical terms Dictionary The Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , that the conceptual history has as its object. Another historiographical approach to philosophy is Eisler's Philosophenlexikon published in 1912 . The Große Werkslexikon der Philosophie, edited by Franco Volpi , offers yet another approach .

Longitudinal sections

Another approach to the history of philosophy is dealing with a specific topic. Problem stories examine individual questions that have been discussed differently along the history of philosophy and have received different answers in their historical context. This includes, for example, the question of the origin and the knowledge of God, which leads to the talk of the “God of the philosophers”. Among other things , Wilhelm Weischedel undertook a passage through the entire history of philosophy. The opposition of freedom and necessity was already a fundamental topic in the Stoa , which in the early modern period found an opposite solution with Spinoza ( determinism ) and Leibniz (indeterminism), which Kant discussed with the philosophy of the “fact of practical reason” and can be found in Heidegger's criticism of Sartre in the letter of humanism . This debate ends in the modern philosophy of mind , in the question of the qualia and in the debates about neurophilosophy . Similar questions such as the problem of universals , the theories of justice or property can be expanded at will. The situation is similar with the history of the philosophical disciplines, that is, the “history of” epistemology, ethics, aesthetics, philosophy of language, metaphysics, logic, cultural philosophy, etc. Ernst Cassirer , whose four-volume study The problem of knowledge in modern philosophy and science is a classic An example of a problem history is, states: “Anyone who follows the overall development of thought must realize that what is involved here is a slow, steady progress of the same great problems. The solutions change; but the same great basic questions assert their existence. "

The consideration of the interpretation of certain philosophers in the course of the history of philosophy is also a longitudinal section, which makes it clear that the respective reception cannot be understood without consideration for the interpreter. Paradigmatic here is Plato, whose philosophy was used at all times as a benchmark for one's own thinking and whose reception via the Platonic Academy , Middle Platonism , the reception of Plato in the Christian philosophy of patristicism with Augustine as the outstanding interpreter, via Neoplatonism and the influence on the philosophy of the Middle Ages and the Florentine Platonism around Ficino in the Renaissance to modern times. Even within a short period of time, the interpretations can be very different, as can be seen at the beginning of the 19th century:

- For Fichte , Plato was primarily a pre-Christian scientist.

- Schelling regarded him as a transcendental philosophical cosmologist .

- Hegel brought Plato's role as an ancient dialectician to the fore.

- In Schleiermacher's picture , Plato is emphasized as a philosophical artist.

- Schopenhauer's interpretation makes Plato a forerunner of Kant.

This comparison alone makes it clear that dealing with the object of the history of philosophy does not guarantee objectivity , but rather that one's own thinking - approving or rejecting, in any case choosing - plays a decisive role in the image of the history of thought generated. The intent of the interpretive philosopher is also of great importance. A vivid example of this is Popper's "Kampfschrift" The Open Society and Its Enemies , which was directed against the National Socialist ideology and in which he made Plato (along with Hegel) the harbinger of totalitarianism , an approach that earned him harsh criticism from many historians of philosophy. From a historical point of view, the criticism of Aristotle, John Locke and Kant regarding their statements on slavery , which they advocated with the perspective of their respective time, is similarly problematic . It is certainly not much of a speculation that they would have approached the issue differently in the context of the 20th century. A special theme of modern historiography is the role of women in the history of philosophy, which has been largely neglected in traditional representations.

Modern hermeneutics in particular make it clear that every preparation of a historical text is at the same time and necessarily an interpretation from a certain perspective. Martin Heidegger explained:

- “The idea that philosophical research has of itself and the concreteness of its problematic also determines its basic attitude towards the history of philosophy. What constitutes the subject area actually questioned for the philosophical problem determines the line of sight into which the past alone can be placed. This pointing inward is not only not contrary to the sense of historical knowledge, but actually the basic condition for making the past speak at all. All interpretations in the field of the history of philosophy, and equally in others, who insist on not interpreting anything in the texts in relation to problem-historical 'constructions', must be caught in the fact that they also indicate, only without orientation and with conceptual means of the most disparate and uncontrollable origin . One considers carelessness about the means used to turn off any subjectivity. "

The lasting

The history of philosophy can also be viewed in terms of the lasting insights of great philosophers. All of them have contributions that have been rejected by their successors and yet their thinking has an impact on all epigones. Leibniz , for example, took this view : “It shows both that the Reformed philosophy can be reconciled with the Aristotelian philosophy and is not opposed to it, and also that one can not only be explained by the other, but also got to. Indeed, even the principles themselves, so braggingly thrown out by innovators, come from the principles of Aristotle. The first way creates the possibility of reconciliation and the last, its necessity. "

Such a sketch can also be found in Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg :

- “Plato's doctrine of ideas has fallen in so far as it isolated the general in a motionless archetype, and has cleared the field of Aristotle's creative, individual concept . But Plato's artistic view of the world, Plato's thought-provoking art and that attitude that transfigured knowledge has remained for all time. Spinoza's grand but mathematically rigid view of the One Substance and his geometric demonstrations have given way to a more vivid 'conception' and evolving method. But his view of unity in the system remains a great example, and some parts of his writings, e.g. B. his simple representation of the passions, retain their significance for science. Kant's critical results are given up and knowledge no longer despairs of the thing in itself. But the way in which he posed the final problems remains a model. And there remain the ingenious treatments with which Kant illuminated individual concepts as if with the flash of the spirit, e.g. B. the investigation of the concept of purpose, of the dynamic, of eudaemonism, a property of science. Fichte 's world-creating act of the self has faded away; but the self-founded character of the spirit stands as a self-erected monument and will always refer every observer to his own strength and dignity. Schelling's constructions of intellectual intuition have in himself given way to a more positive consideration; but the momentum of his thoughts and the artistic beauty of his portrayal are destined to renew the life of the whole of knowledge again and again, when it threatens to be suffocated by the mass of the individual, and now to wither from subtle abstractions. In the same way, what is transitory and what is permanent will be separated in Hegel's system. It is true that the dialectical method is the uniform pupation of all his thoughts; but the freer spirit that is in it will tear the web and outlast the form. "

Nicolai Hartmann made very similar considerations . Every system thinker is fixated on his own basic ideas and overlooks the fact that he makes a contribution to the overall return of philosophy by adding another building block to knowledge. “Neither Heraclitus nor Parmenides were right on the whole, but both saw part of the truth that has been preserved. Democritus and Plato taught opposites, atoms bear no resemblance to ideas; but both are looking for the λόγοι [logoi = principles of reason] and both found them in the same conclusion about the prerequisites. Thomas and Duns sought the principle of individuation in quite the opposite direction; but what they found was nevertheless similar - the qualitatively determined matter and the highly differentiated form (materia signata [certain substance] and haecceitas [thisness]) - both complement each other without compulsion; but neither they nor their successors realized it. Locke and Leibniz each saw one side of the structure of knowledge; they put themselves in the wrong by advancing to extreme consequences - to absolute sensualism and absolute a priorism; these consequences were in incurable conflict. What the one and the other originally saw, however, not only got along, but afterwards - with Kant - proved to be possible with one another and with one another. One can also cite the example of Hegel and Schopenhauer , who both meant a unified world ground; one as absolute reason, the other as absolute unreason; but here the level of speculation is too great and the inequality of implementation too conspicuous to produce a uniform picture. At least the demonstrable meaning of the real world should lie on a middle line between the extremes. "

Nicholas Rescher sees an advance in the philosophical development, an improved level of insight, but without the expectation of a conclusion of this process : “Old doctrines in philosophy never die out; they just reappear in a new make-up. They just become increasingly complex and sophisticated to meet the demands of new conditions and circumstances. In the course of the dialectical progress of philosophical development, more and more complex questions, refined terms, and more subtle distinctions are introduced. As new theories are introduced to resolve the aporetic inconsistencies of previous determinations, there is not only an increasing refinement in the conceptual machinery, but also a continuous expansion of the problem horizon of the respective controversial doctrine. "

The beginnings of philosophy

There are a number of theories for determining the origins of philosophy, each of which also depends on what is defined as philosophy. The doxographer Diogenes Laertios wrote about this in the 3rd century BC. Chr .: “In the opinion of some, the philosophy originated with the Un-Greeks, for the Persians had their magicians , the Babylonians and Assyrians their Chaldeans , and the Indians their gymnosofists . Among the Celts and Gauls were the so-called Druids and Semnothes, as Aristotle and Sotin […] say. The Föniker Ochus , the Thracian Zamolxis and the Libyan Atlas are also mentioned. The Egyptians name Hefästus, a son of the Nile, as the creator of philosophy, whose teachers are its priests and prophets. ”Even Aristotle Thales was one of the first“ who researched beings and philosophized about the truth before us (philosophêsantes peri tês alêtheias ) ".

In the presentations on the history of Western philosophy, the beginning of philosophy is usually found in the natural philosophy of the Greek colonies around 600-500 BC. Seen. This period is described as the "transition from myth to logos". The explanation for the phenomena of the world was no longer sought in the arbitrary acts of the gods - such as in the astronomy of Mesopotamia - but in laws and mechanisms with which events can be predetermined. The prediction of a solar eclipse by Thales von Milet in the year 585 BC is considered an important event in this sense . Seen.

Around 1805, Hegel developed a theory according to which there is a development of thought that progresses from despotic Asian states, in particular from China via India to Persia and subsequently to the aristocratic societies of Greece and the Roman Empire and finally ends in the modern constitutional states of the West. For him, the history of philosophy becomes a history of progress of the increasing self-development of thought and the resulting increasing freedom of the individual.

Karl Jaspers said on the question of the beginning: "The history of philosophy as methodical thinking began two and a half millennia ago, but as mythical thinking much earlier." Jaspers differentiates between historical beginnings and the origins of philosophy. His origins include amazement, doubt and the awareness of being lost, which is based on the contingency of the world and the borderline situations it creates . In contrast to Hegel, he saw in the Axial Age a movement of awakening that arose in different cultures at about the same time, which resulted in a “spiritualization” of human culture.

Modern intercultural philosophy goes beyond Jaspers and emphasizes the interweaving of thought between cultures that has existed at all times, so that a distinction between occidental and oriental philosophy, as it was still made by Jaspers, is considered obsolete. Heinz Kimmerle counts philosophizing as well as art to the peculiar attributes of humanity, which depend on the respective cultural development such as the separation of mental and physical work. The Philosophy Atlas by Elmar Holenstein , for example, shows new perspectives .

Classifications in the history of philosophy

Any structuring of the historical process is arbitrary. It serves to work out common features of certain epochs and is therefore already an interpretation. There is a risk of oversimplification through labeling and stereotyping. The determination of an epochal consciousness is problematic from a historical perspective. Immanuel Kant warned: "Names that denote a sectarian attachment have at all times caused a lot of legal distortion" Martin Heidegger took the view: "Metaphysics founded an age by giving it a certain interpretation of beings and a certain conception of Truth gives the basis of his being. ”Accordingly, he distinguished a Greek, a Christian and a modern interpretation of beings. Kurt Flasch objects to such a hard structuring of the historical development : "You can always find texts that falsify the schema of the epochs ". Epoch structures are shaped by the intentions of those who use them and inevitably lead to distortions. Flasch therefore advocates largely abandoning such historical categories. At best, these can express tendencies and serve a rough structure without the respective term allowing sharp delimitations in terms of content. The tendency towards classification "satisfies a certain need for order and can appear suitable for finding places where inquiries have to be made."

The division of philosophy used by Jakob Brucker goes back to Christian Thomasius under theological influence according to 1. The time before the Roman Empire. 2. The time from the beginning of the Roman Empire to the beginning of the Italian Renaissance. 3. The time from the Italian Renaissance to the present day. Dieterich Tiedemann suggested - following the idea of progress - the formation of five epochs in the history of philosophy:

- The pre-scientific beginnings from Thales to Socrates, shaped by an elementary pantheism and materialism

- From Socrates to the Roman Empire, competing schools with sharper conceptual structures, ontology and deism

- Little progress in the period up to the Middle Ages due to the exaggerations of Neoplatonism with a further development of the concept of emanation

- Middle Ages and Renaissance under the influence of Arabic philosophy with a new form of discussion and even greater accuracy in the examination of metaphysical principles

- Modern times with dominance of experience and observation and the invention of new systems

Joseph Marie Degérando created a comparable scheme for characterization and classification by dividing the history of philosophy according to the predominant modes of thought:

- The search for the principles of things (pre-Socratic)

- The phase of logic and dialectics (classical, Hellenism)

- Contemplation, Enlightenment and Mysticism (Neo-Platonism, Early Middle Ages)

- Axioms and Argumentation (Scholasticism)

- Art of method, search for laws, study of the spirit (modern times)

Friedrich August Carus chose a completely different level of classification with the distinction between “main types or methods of the philosophical process”, on which he based a passage through history, and according to the Kantian categories of dogmatism ( thesis ), skepticism ( antithesis ) and they analyzed in neutralizing criticism . His phenomenological map of ways of thinking, which also includes a categorization of the forms of language and the methodology with which he characterized the "soul" of the respective system and which does not take any chronology into account, is divided into:

- A) "positive dogmatism" ( empiricism , rationalism , eclecticism )

- B) "Systems about being and not-being, reality and appearance" ( realism , idealism , synthesis)

- C) "Systems of the kind of being - of the universe (macrocosm) or the human world (microcosm)" ( pluralism , monism / materialism , spiritualism )

- D) "Systems of causality " ( determinism , indeterminism both as cosmology and as anthropology )

- E) "Assertions about fate" ( fatalism , unconditional and pointless necessity , deliberate arrangement by an author)

- F) " Theological ways of thinking " ( supranaturalism , theism , atheism , deism )

- G) " moral systems " (based on material or formal principles)

The romantic Friedrich Ast follows Schlegel's idea of the cycle , in which the story strives again for harmonious unity after the alternation of 'alienation' and 'division'. This results in four stages of development, which Ast artfully linked with the dialectic of realism, idealism and ideal realism:

- "The period of undivided, in itself veiled unity, of original life, from whose division real life emerged: the period of oriental humanity, the mythical (golden) age." This is the period of the original philosophy of the Indians, Chaldeans, Persians, Tibetans, Egyptians and Chinese.

- "The period of external life emerging from unity, characterized by free education and external community: period of the Greek and Roman world, ie of classical antiquity." In this period of realism, philosophy develops as the realism of the Ionians , idealism of the Pythagoreans and ideal realism of the Attics . The culture is plastic and outwardly formed.

- "The period of life striving from the outside into the inner, into the spirit: the period of the Christian world." In medieval idealism, the stages of scholasticism and mysticism are found, in which Platonism, Kabala and theosophy are at work, which are reflected in the philosophy of Giordano Unite Brunos . Christian thinking is musical, internal and strives to develop towards unity with the external.

- "The period of life striving for a freely formed unity of the outer and inner: the period of the modern world." The realistic perspective represented in modern ideal realism beginning with Descartes the rational philosophy of Spinoza , the intellectual philosophy of Locke as well as the empiricism and skepticism of Hume . On the idealistic side there are Leibniz , Berkeley and the transcendental idealism of Kant . Reconciliation and unity arise in Schelling's ideal realism, to whose philosophy Ast professed. Culturally, this is the phase of poetry in which sculpture and music unite, in which the opposites of Greek outwardness and Christian inwardness also become a unity.

The representatives of the historical school protested against this more or less violent construction of a logic in the history of philosophy, which is also expressed in particular in Hegel's dialectic: "One cannot write the history of philosophy according to periods, because everything period is unphilosophical." “The story itself has no sections; all period division is only a means to facilitate the lesson, only a list of resting points. "

Under the guiding principles of reason and knowledge, Tennemann used a simple chronological periodization according to antiquity, the Middle Ages and modern times with the following characterization:

- “First period. Reason's free striving for knowledge of the ultimate reasons and laws of nature and freedom from principles without a clear awareness of essential principles. Classical Antiquity or Greek and Roman Philosophy.

- Second period. Reason's striving for knowledge under the influence of a principle given by revelation and elevated above reason [...] philosophy of the Middle Ages

- Third period. Independent striving to research the ultimate principles and complete systematic linking of knowledge, especially visible in the exploration, justification and limitation of philosophical knowledge. Newer philosophy. "

This division according to periods and central ideas - as Tennemann carried out - has become common in the history of historiography from a European point of view and can be found, for example, in Wilhelm Windelband , and is also widespread in more recent representations of the history of European philosophy. Windelband emphasized that within this temporal structure, philosophy should be examined with regard to its problems, distinguishing between theoretical philosophy on the one hand ( metaphysics , natural theology , natural philosophy and methodological philosophy of history as well as logic and epistemology) and practical philosophy on the other ( ethics , philosophy of society , legal philosophy , empirical philosophy of history, philosophy of art and religion ). This matrix of temporal structure and problem areas suggests that the particular problem areas can be viewed as a problem history in a longitudinal section.

With such a rough subdivision, of course, many individual points of view and opinions are lost, which can only come to light when looking at the individual sections within the respective larger periods. Fundamental ways of thinking that persist independently of temporal structures such as mysticism or panpsychism , but also the successors of ancient skepticism, cannot be incorporated into a period scheme. The division also includes a fading out of the non-European history of philosophy, which in some cases goes back further than that of Europe and was largely independent, especially in China and India , so that it is usually recorded in separate chapters of the corresponding historical works or in independent works of the history of philosophy (see Confucianism , Buddhism , Hinduism , Islamic Philosophy ).

| phase | Greek classical | Hellenism | middle Ages | Modern times |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Thesis (realism) |

Eleates | Aristotle | Thomas Aquinas | Metaphysics (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz) |

|

Transition (empiricism) |

Empedocles, Anaxagoras, atomists | Stoa, kepos | empiricism | |

|

Antithesis (skepticism) |

sophistry | skepticism | Nominalism, mysticism | subjective idealism, skepticism, enlightenment |

|

Transition (self-abolition of negativity) |

Socrates | Philo of Larissa, Antiochus | Criticism, finite transcendental philosophy | |

|

Synthesis (objective idealism) |

Plato | Neoplatonism | Nicolaus Cusanus | absolute idealism |

After an analysis of the history of philosophy, in particular the cycle idea of Friedrich Ast (see above) and Franz Brentano , Vittorio Hösle developed his own cyclical scheme of the history of philosophy, expanding the dialectical structure of history by two intermediate stages, each of which is in the transition from thesis (empiricism) and develop antithesis (skepticism) to synthesis (objective idealism). This is on the one hand the positivistic-empirical relativism shaped by the idea of usefulness and on the other hand the position of a transcendental philosophy of this world, which rejects the recognizability of objective ideas ( I know that I don't know ) and only recognizes transcendence as "regulatory ideas" (Kant). With this "modification of Hegel's philosophy of history, enriched by the idea of cycles", he wants to combine the idea of dialectical development with a linear notion of progress, resulting in a historical development in the form of a spiral movement. In classifying the historical epochs, Hösle essentially follows Hegel's classification into the Greek Classical period as a starting point, followed by the Hellenistic-Roman times, the Middle Ages and the modern age, which he regards as an epoch completed by Hegel, as well as the modern age. Hösle does not give an explicit structure for the last period. It should be noted that the definition of the dialectically constructed synthesis in Kantianism (Carus), in the romantic concept (Ast) and in the objective idealism that Hösle advocates differs from one another and is seen in their own system. The problem with the Hösles model is that it lacks a well-considered justification for its model, that it neglects individual phases in the history of philosophy such as late antiquity and the Renaissance , and that it is not open to the simultaneity of opposing positions. As with all systematizations, the assignment of individual philosophers to certain categories is also problematic. In Wilhelm Dilthey , for example, Aristotle and the Stoa are assigned to objective idealism. At the very least, the formation of such fixed classifications requires precise content-related provisions and criteria for their conceptual content.

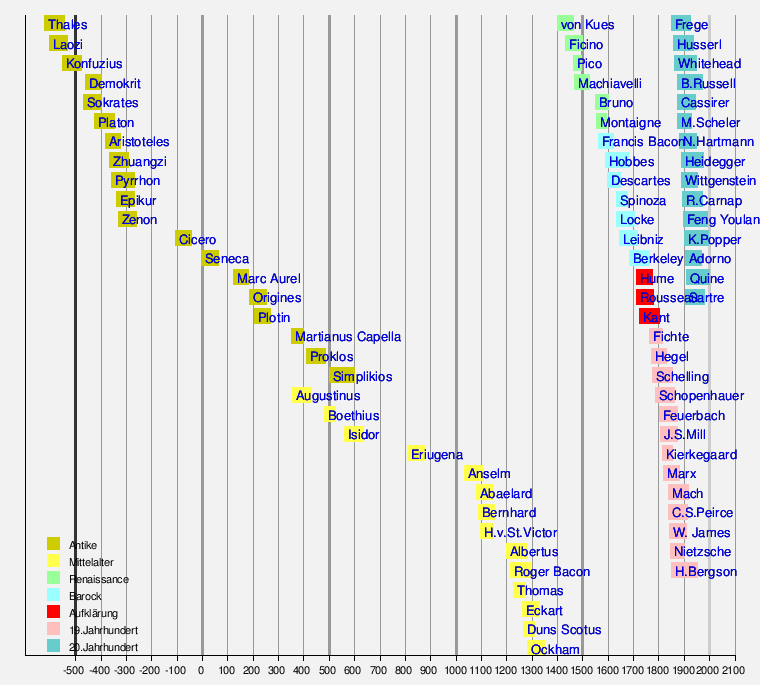

Important people in the history of philosophy