Portuguese language

| Portuguese (português) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

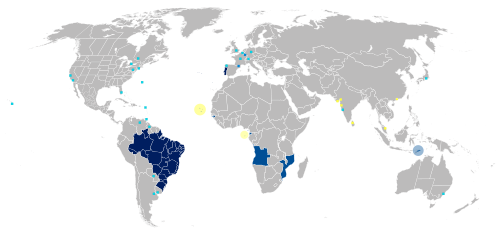

Europe : Portugal ( Spain ) * ( Andorra ) ** ( Luxembourg ) ** * Minority language ** Minority language; Country has CPLP observer status ( Paraguay ) 1 ( Argentina ) 2 ( Uruguay ) 2 1 regional partly mother tongue or lingua franca 2 reg. partly mother tongue / lingua franca; CPLP observer status Africa : Angola (incl. Cabinda ) Equatorial Guinea Guinea-Bissau Cape Verde Mozambique São Tomé and Príncipe ( Senegal ) a) a) Minority / reg. partly cultural language; CPLP observer status

( Namibia ) ** ** Minority language; CPLP observer status Asia : Macau East Timor ( India ) * ( Japan ) ** * Minority language ** Minority language; CPLP observer status |

|

| speaker | 240 million native speakers , 30 million second speakers (estimated) |

|

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

Europe : Portugal Africa : Angola Equatorial Guinea Guinea-Bissau Cape Verde Mozambique São Tomé and Príncipe South America : Brazil Asia : Macau (to People's Republic of China ) East Timor |

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

pt |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

por |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

por |

|

The Portuguese language ( Portuguese português ) is a language from the Romance branch of the Indo-European language family and forms the closer unit of Ibero- Romance with Spanish (the Castilian language), Catalan and other languages of the Iberian Peninsula . Together with Galician in northwest Spain, it goes back to a common original language, Galician-Portuguese , which developed between late antiquity and the early Middle Ages . After the formation of the statehood of Portugal , the two today's languages developed from it. Today Portuguese is considered a world language .

It is spoken by over 240 million native speakers; including second speakers, the number of speakers is around 270 million.

The Portuguese language spread around the world in the 15th and 16th centuries when Portugal established its colonial empire, which in part survived until 1975 and encompassed present-day Brazil as well as areas in Africa and the coasts of Asia. Macau was the last to pass to China from Portuguese ownership. As a result, Portuguese is the official language of several independent states today and is also spoken by many people as a minority or second language. In addition to the actual Portuguese, there are about twenty Creole languages on a predominantly Portuguese basis. As a result of emigration from Portugal, Portuguese has become an important minority language in several countries in Western Europe and in North America over the past few decades .

distribution

* in Macau, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Equatorial Guinea with standard Portuguese as the official language

Portuguese is the only official language in Angola , Brazil , Mozambique , Portugal and São Tomé and Príncipe . Along with other languages, Portuguese is the official language in East Timor (along with Tetum ), Macau (along with Chinese ), and Equatorial Guinea (along with French and Spanish ). In Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau , although it is the sole official language, but not the main language. An important language, but not an official language, is Portuguese in Andorra , Luxembourg (spoken by around ten percent of the population due to the immigration of Portuguese workers), Namibia and South Africa .

America

With over 190 million speakers in Brazil, Portuguese is the most widely spoken language in South America . But Portuguese is also enjoying growing importance in the Spanish-speaking countries of South America. Because of the great influence of Brazil, Portuguese is taught in some of the rest of the South American states, particularly Argentina and the other Mercosur (Mercosul) member states . In the border area between Brazil and Argentina, Bolivia , Paraguay ( Brasiguayos ) and Uruguay, there are people for whom Portuguese is the mother tongue (122,520 native Portuguese speakers live in Paraguay according to the 2002 census). Among the people who live in the border area but are not able to speak the other language, a mixed language of Portuguese and Spanish called Portunhol has developed. In addition, Portuguese is an important minority language in Guyana and Venezuela .

In North America and the Caribbean, there are large Portuguese-speaking colonies in Antigua and Barbuda , Bermuda , Canada , Jamaica, and the United States , with the majority made up of immigrants or guest workers from Brazil or Portugal. In Central America, however, the Portuguese language is of little importance.

Europe

In Europe, Portuguese is mainly spoken by the 10.6 million inhabitants of Portugal. In Western Europe , the language has spread in recent decades, primarily through immigration from Portugal, and is spoken by more than ten percent of the population of Luxembourg and Andorra . There is also a significant proportion of the Portuguese-speaking population in Belgium , France , Germany , Jersey and Switzerland . In Spain , Portuguese is spoken in the Vale do Xalima , where it is referred to as A fala . A Portuguese dialect was spoken in oliveça , today in Spain , until the 1940s. Galician , which is very closely related to Portuguese , is spoken in Galicia in northwestern Spain .

Galician and Portuguese have the same roots and were a single language until the Middle Ages , now known as Galician-Portuguese . This language was even used in Spain ( Castile ) in poetic creation. Even today, many linguists see Galician and Portuguese as one unit. For sociolinguistic reasons, however, the two languages are often seen separately. In Galicia, two written language standards have emerged, the one supported by the Galician Autonomous Government being more based on Spanish (Castilian), while in certain political and university circles a standard very close to Portuguese has been established . The only Galician MP in the European Parliament , Camilo Nogueira , says he speaks Portuguese.

Africa

Portuguese is an important language in sub- Saharan Africa . Angola and Mozambique , together with São Tomé and Príncipe , Cape Verde , Equatorial Guinea and Guinea-Bissau, are known and organized as PALOP (Paises Africanos de Língua Oficial Portuguesa) ; they represent around 32 million speakers of Portuguese (a generous estimate of nine million native speakers, the rest being bilingual). Paradoxically, the use of the Portuguese language increased after the independence of the former colonies from Portugal. The governments of the young states saw the Portuguese language as an instrument for the development of the country and a national unity.

In central and southern Africa, Portuguese is - depending on the country or region - a more or less important minority language in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (border region with Angola), in the Republic of the Congo , Malawi , Namibia , South Africa (more than one million speakers), and Zambia and Zimbabwe .

In other parts of Africa there are Portuguese Creole languages . In the south of Senegal , in Casamance , there is a community that is linguistically and culturally related to Guinea-Bissau and where Portuguese is learned. On the island of Annobón ( Equatorial Guinea ) there is another Creole language that is closely related to that of São Tomé and Príncipe .

In Angola , Portuguese quickly became a national language rather than just a lingua franca. This is especially true for the capital Luanda . According to the official 1983 census, Portuguese was then the mother tongue of 75% of Luanda's population of around 2.5 million (at least 300,000 of whom spoke it as the only language), and 99% of them could communicate in Portuguese, albeit with varying levels of proficiency . This result is hardly astonishing, because as early as the 1970s a survey conducted in the slum areas of Luanda in 1979 indicated that all African children between the ages of six and twelve spoke Portuguese, but only 47% spoke an African language. Today, especially in Luanda, young Angolans rarely speak any African language besides Portuguese. Nationwide, around 60% of the population, which according to the 2014 census is 25.8 million, use Portuguese as a colloquial language . Also in the 2014 census, 71.15% of respondents said they spoke Portuguese at home (85% in urban and 49% in rural areas). The television stations from Portugal and Brazil, which can be received in Angola and which are very popular, do their part.

The Angolan Portuguese also influenced today spoken in Portugal Portuguese, since the Retornados , (Portuguese returnees after the Independence of Angola) and Angolan immigrants brought with them words that spread especially in the young urban population. These include iá (ja), bué (many / very; synonymous with the standard language muito ) or bazar (to go away) .

Mozambique is one of the countries in which Portuguese is the official language , but it is mostly only spoken as a second language. But it is the most widely spoken language in cities. According to the 1997 census, about 40% of the total population speaks Portuguese, but about 72% of the urban population. On the other hand, only 6.5% (or 17% in cities and 2% in rural areas) say Portuguese is their mother tongue. Mozambican writers all use a Portuguese that has adapted to Mozambican culture.

In Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau , the most important languages are Portuguese Creole, known as Crioulos , while the use of Portuguese as a colloquial language is on the decline. However, most Cape Verdeans can also speak standard Portuguese, which is used in formal situations. Schooling and television from Portugal and Brazil, on the other hand, contribute to decreolization. In Guinea-Bissau, the situation is slightly different because only about 60% of the population speak Creole, and only 10.4% of them speak standard Portuguese (according to the 1992 census).

In São Tomé and Príncipe , the population speaks a kind of archaic Portuguese that has many similarities to Brazilian Portuguese . However, the country's elite are more likely to use the European version, similar to the other PALOP countries. In addition to the actual Portuguese, there are three Creole languages. As a rule, children learn Portuguese as their mother tongue and only learn Creole, called Forro , later. The daily use of the Portuguese language, also as a colloquial language, is growing, and almost the entire population is proficient in this language.

Asia

Portuguese is spoken in East Timor , in the Indian states of Goa and Daman and Diu, and in Macau ( People's Republic of China ). In Goa, Portuguese is called the language of the grandparents because it is no longer taught in school, has no official status and is therefore spoken by fewer and fewer people. In Macau, Portuguese is spoken only by the small Portuguese population who stayed there after the former colony was handed over to China. There is only one school there that teaches in Portuguese. Nevertheless, Portuguese will remain an official language alongside Chinese for the time being .

There are several Portuguese Creole languages in Asia. In the Malay city of Malacca there is a Creole language called Cristão or Papiá Kristang , other active Creole languages can be found in India , Sri Lanka and on Flores . In Japan there are about 250,000 people known as dekasegui ; these are Brazilians of Japanese descent who have returned to Japan, but whose mother tongue is Portuguese.

In East Timor, the most widely spoken language is Tetum , an Austronesian language, but it has been heavily influenced by the Portuguese language. At the end of the Portuguese colonial era, many Timorese were able to speak at least basic Portuguese through a rudimentary school education. However, the reintroduction of Portuguese as the national language after the Indonesian occupation (1975-1999) met with displeasure from the younger population, who had gone through the Indonesian education system and did not speak Portuguese. The older generation predominantly speaks Portuguese, but the proportion is increasing as the language is taught to the younger generation and interested adults. East Timor has asked the other CPLP countries to help introduce Portuguese as the official language. With the help of the Portuguese language, East Timor tries to connect with the international community and to differentiate itself from Indonesia . Xanana Gusmão , the first President of East Timor since the restoration of independence, hoped that Portuguese would be widely spoken in East Timor within ten years. In 2015, the census found that 1,384 East Timorese have Portuguese as their mother tongue, 30.8% of the population can speak, read and write Portuguese, 2.4% speak and read, 24.5% only read and 3.1% only speak. There are voices in the introduction of Portuguese as an official language by the old educational elites see an error. Most university courses are still held in Bahasa Indonesia . English is becoming increasingly important due to its proximity to Australia and the international peacekeeping forces that were in the country until 2013. Portuguese is only gradually taught to children in school and is used as a language of instruction alongside Tetum. One of the reasons for this is the lack of Portuguese-speaking teachers. The Portuguese Creole language of East Timor, Português de Bidau, died out in the 1960s. The speakers used more and more standard Portuguese. Bidau was spoken almost only in the Bidau district in the east of the capital Dili by the Bidau ethnic group , mestizos with roots on the island of Flores. Macau Creole Portuguese was also spoken in Timor during the heaviest immigration period in the 19th century, but quickly disappeared.

Official status

The Community of Portuguese- Speaking Countries CPLP is an international organization made up of eight independent states whose official language is Portuguese. Portuguese is also the official language of the European Union , Mercosul , the African Union, and some other organizations.

Portuguese is the official language in:

| country | Native speaker | Overall spread | population | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (including second language speakers) | (July 2003) | |||

| Africa | ||||

|

|

60% | k. A. | 25,789,024 | According to the results of the 2014 census |

|

|

k. A. | 80% | 412.137 | |

|

|

k. A. | 14% | 1,360,827 | |

|

|

12% | 50% | 20.252.223 | According to the 2007 census |

|

|

50% | 95% | 175,883 | |

| no official language: | ||||

|

|

less than 1% | less than 1% | 1,927,447 | |

|

|

1 % | 1 % | 42,768,678 | |

| Asia | ||||

|

|

k. A. | 18.6% | 947,400 | |

|

|

2% | k. A. | 469.903 | |

| not official language: | ||||

|

Daman ( India )

|

10% | 10% | 114,000 | |

|

Goa ( India )

|

3–5% | 5% | 1,453,000 | |

| Europe | ||||

|

|

99% | 100% | 10.102.022 | |

| no official language: | ||||

|

|

11% | 11% | 69,150 | |

|

|

14% | 14% | 454.157 | |

| South America | ||||

|

|

98-99% | 100% | 190.732.694 | According to the 2010 census |

historical development

The Portuguese language developed in the west of the Iberian Peninsula from a form of spoken Latin ( Vulgar Latin ) used by Roman soldiers and settlers since the 3rd century BC. Was brought to the peninsula. After the collapse of the Roman Empire , Galician-Portuguese began to develop separately from the other Romance languages under the influence of the pre-Roman substrata and the later superstrate . Written documents written in Portuguese have survived from the 11th century. By the 15th century, the Portuguese language had developed into a mature language with a rich literature.

Roman colonization

From the year 154 BC The Romans conquered the west of the Iberian Peninsula with today's Portugal and Galicia , which later became the Roman province of Lusitania . Along with the settlers and legionaries came a popular version of Latin , Vulgar Latin , from which all Romance languages are derived. Although the area of what is now Portugal was inhabited before the arrival of the Romans, 90 percent of Portuguese vocabulary is derived from Latin. There are very few traces of the original languages in modern Portuguese.

Germanic Migration Period

From 409, when the Western Roman Empire began to collapse, peoples of Germanic origin invaded the Iberian Peninsula . These Germanic tribes, mainly Suebi and Visigoths , slowly assimilated to the Roman language and culture. However, with little contact with Rome , Latin continued to develop independently, with regional differences increasing. The linguistic unity on the Iberian Peninsula was slowly destroyed and dialects that could be distinguished from one another developed , including the forms Galician-Portuguese, Spanish and Catalan , which are now standard languages . The development of Galician-Portuguese away from Spanish and Mozarabic is traced back to the Suebi, among other things. Germanisms thus came into Portuguese in two ways: indirectly as Germanic borrowings, which came to the Iberian peninsula as part of the common Latin colloquial language of the Roman legionaries, and directly as loanwords of Gothic and Suebian origin. However, other authors assume that Portuguese is older and more conservative than Castillano, which originated in the region around Burgos, which has undergone various sound shifts that cannot be found in Portuguese (e.g. from the Latin palatal f to the frictional h , von lat. ct to ch as in nocte / noche , from diphthongs like au to monophthongs like o ).

Moorish conquest

From 711 the Moors conquered the Iberian Peninsula and Arabic became the administrative language in the conquered areas . However, the population continued to speak their Iberomaniac dialect, which is why the influence of Arabic on Portuguese was not very strong. A Romance written language in Arabic script , the so-called Mozarabic, also developed . After the Moors had been driven out by the Reconquista , many Arabs, whose legal status was severely restricted, remained in the area of present-day Portugal; they later also worked as free craftsmen and assimilated to the Portuguese culture and language. Due to the contact with Arabic, traces of Arabic can mainly be found in the lexicon , where New Portuguese has many words of Arabic origin that cannot be found in other Romance languages. These influences mainly affect the areas of nutrition and agriculture, in which innovations were introduced by the Arabs. In addition, the Arabic influence can be seen in place names of southern Portugal such as Algarve or Fátima in the west .

Rise of the Portuguese language

The Romans split from the Roman province of Lusitania in the 1st century BC. From the Gallaecia (today's Galicia) and attached them to the Tarraconensis ( Hispania Citerior ). The Portuguese language (like Galician) developed from Galician-Portuguese , which is now extinct except for a few remains ( A Fala ) and which arose between the 8th and 12th centuries in what is now northern Portugal and in present-day Galicia. For a long time, Galician-Portuguese existed only as a spoken language, while Latin was still used as a written language . The earliest written evidence of this language is the " Cancioneiros " from around 1100. Galician-Portuguese developed in the High Middle Ages (13th / 14th centuries) to become the most important language of poetry on the Iberian Peninsula.

The county of Portugal became independent in 1095, from 1139 Portugal was a kingdom under King Alfonso I. After Portugal's independence from Castile , the language slowly developed on Portuguese territory, mainly due to the normative influence of the royal court (in contrast to Galicia). The first written evidence of the so-called Romanesque dialect are the will of Alfonso II and the Notícia de Torto from 1214.

In 1290 King Dionysius (Diniz) founded the first Portuguese university, the Estudo Geral in Lisbon . He stipulated that Vulgar Latin , as Portuguese was still called at the time, should be preferred to Classical Latin. From 1296 the royal chancelleries used Portuguese, which means that the language was no longer used only in poetry , but also in laws and notarial documents.

Due to the influence of court culture in southern France on the Galician poetic language in the 12th and 13th centuries, Occitan loanwords also found their way into the language area of Portugal. However, only a limited number of these words have survived in modern Portuguese. Of greater importance for the development of the vocabulary is the influence of the French language, which today can be demonstrated not only lexically but also phraseologically .

With the Reconquista Movement, the Portuguese's sphere of influence gradually expanded southwards. By the middle of the 13th century, this expansion ended on the southern border of today's Portugal with the reconquest of Faro in 1249, making the entire west of the Iberian Peninsula the Galician-Portuguese language area. By the 14th century, Portuguese had become a mature language with a rich literary tradition and poetry spread in other areas of the Iberian Peninsula , such as the Kingdom of León , Castile , Aragon, and Catalonia . Later, when Castilian (which is practically modern Spanish) became firmly established in Castile and Galicia came under the influence of the Castilian language, the southern variant of Galician-Portuguese became the language of Portugal.

Arabic and Mozarabic had a significant influence on the development of the Portuguese language : During the Reconquista, the center of Portugal moved further and further south towards Lisbon, where there were speakers of various varieties who influenced Galician-Portuguese - in contrast to the north, its language was more conservative and even more influenced by Latin. In a dialect in the north of Portugal (on the border with Spain), the Mirandés , the connection to the Kingdom of León, i. H. the Castilian influence, still to be recognized, while the Leonese dialect in Spain e.g. T. is strongly influenced by the Galician-Portuguese.

Period of the Portuguese Discoveries

Between the 14th and 16th centuries, during the time of the Portuguese discoveries, the Portuguese language spread to many regions of Asia , Africa and America . In the 16th century it was the lingua franca in Asia and Africa, where it served not only for colonial administration, but also for trade and communication between the local rulers and Europeans of all nationalities. In Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka ), some kings spoke Portuguese fluently, and nobles frequently took Portuguese names. The spread of the language was also promoted by marriages between Portuguese and local people (which was a more common practice in the Portuguese colonial empire than in other colonial empires). Since the language was equated with the missionary activities of the Portuguese in many parts of the world , Portuguese was also called Cristão (Christian) there. Although the Dutch later tried to push back Portuguese in Ceylon and what is now Indonesia , it remained a popular and widely used language there for a long time.

Portuguese Creole languages emerged in India , Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Indonesia after Portugal lost influence in these countries to other European powers. Portuguese words can be found in modern lexicons in many languages, for example the word pan for “bread” in Japanese (Portuguese: pão ), sepatu for “shoe” in Indonesian (Portuguese: sapato ), keju for “cheese” in Malay (Portuguese: queijo ) or meza for "table" in Swahili (Portuguese: mesa ). Portuguese loanwords can also be found in Urdu , e.g. B. cabi for "key" (from "chave"), girja for "church" (from "igreja"), kamra for "room" (from "cámara"), qamīz for "shirt" (from "camisa"), mez for "table" (from "mesa").

Development since the Renaissance

Since the middle of the 16th century, a large number of loanwords found their way into the Portuguese language, mostly of Latin or Greek origin. Italian words from the fields of music , theater , painting and Spanish loanwords, which are particularly numerous due to the personal union between Portugal and Spain from 1580 to 1640, made the language richer and more complex. For this reason, a distinction is made between two phases of development: Old Portuguese (12th to mid-16th century) and New Portuguese, whereby the appearance of Cancioneiro Geral by Garcia de Resende in 1516 is considered to be the end of Old Portuguese .

However, the areas where Portuguese had spread before the development of New Portuguese largely did not go along with these developments. In Brazil and São Tomé and Príncipe , but also in some remote rural areas of Portugal, dialects are therefore spoken that are similar to Old Portuguese.

In addition to the 200 million Brazilians, more than 10 million Portuguese and just as many residents of the former African and Asian colonies speak Portuguese as their mother tongue. Portuguese developed into the second most common Romance mother tongue after Spanish. Portuguese owes this position to the fact that the population of Brazil has increased more than tenfold in the last 100 years: in 1900 Brazil had a population of only 17 million.

Relationship with other languages

As a Romance language, Portuguese has parallels to Spanish, Catalan, Italian, French , Romanian and the other Romance languages, especially in terms of grammar and syntax . It is particularly similar to the Spanish language in many respects, but there are significant differences in pronunciation. With a little practice, however, it is possible for a Portuguese to understand Spanish. If you look at the following sentence:

- Ela fecha semper a janela antes de jantar. (Portuguese)

- Ela pecha semper a fiestra antes de cear. (Galician)

- Ella cierra siempre la ventana antes de cenar. (Spanish)

Almost all words in one language have very similar relatives in the other language, although they may be used very rarely.

- Ela encerra semper a janela antes de cear. (Portuguese, with little choice of words)

(The phrase means: 'She always closes the window before dinner.')

(Latin: 'Illa claudit semper fenestram ante cenam.')

However, there are also a number of words in which there is no relationship between the languages and which poses problems for the respective speakers in the other country. Examples:

| German | Spanish | Portuguese | Portuguese (Brazil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| raw ham | jamón (serrano) | presunto | presunto (cru) |

| cooked ham | jamón dulce (York) | fiambre | presunto |

| Auto repair shop | taller | oficina | oficina |

| office | oficina | escritório | escritório |

| train | tren | comboio | trem |

There are places where Spanish and Portuguese are spoken side by side. Native speakers of Portuguese can usually read Spanish and often understand spoken Spanish relatively well; Conversely, the latter is usually not the case due to the phonetic peculiarities of Portuguese.

Dialects

Standard Portuguese , also known as Estremenho , has changed more often in history than other variations. All forms of the Portuguese language of Portugal can still be found in Brazilian Portuguese . African Portuguese, especially the pronunciation of São Tomé and Príncipe (also called Santomense ), has a lot in common with Brazilian Portuguese. The dialects of southern Portugal have also retained their peculiarities, including the particularly frequent use of the gerund . In contrast, Alto-Minhoto and Transmontano in northern Portugal are very similar to the Galician language.

Standard Portuguese from Portugal is the preferred pronunciation in the former African colonies. Therefore one can distinguish two forms, namely the European and the Brazilian; There are generally four major standard pronunciations, namely those of Coimbra , Lisbon , Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo , these are also the most influential forms of pronunciation.

The most important forms of pronunciation of Portuguese, each with an audio sample as an external link, are the following:

| dialect | Audio sample | Spoken in | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | ||||

| Açoriano | Audio sample | Azores | ||

| Alentejano | Audio sample | Alentejo | ||

| Algarvio | Audio sample | Algarve | ||

| Alto-Minhoto | Audio sample | North of the city of Braga | ||

| Baixo-Beirão; Alto-Alentejano |

Audio sample | Inner center Portugal | ||

| Beirão | Audio sample | Central Portugal | ||

| Estremenho | Audio sample | Regions around Coimbra | ||

| Lisboeta | Regions around Lisbon | |||

| Madeirense | Audio sample | Madeira | ||

| Nortenho | Audio sample | Regions around Braga and Porto | ||

| Transmontano | Audio sample | Trás-os-Montes | ||

| Brazil | ||||

| Caipira | Brazilian hinterland, including much of the state of São Paulo, Paraná, Mato Grosso do Sul, Goiás and south of Minas Gerais | |||

| Capixaba | State of Espírito Santo | |||

| Fluminense | Audio sample | State of Rio de Janeiro | ||

| Baiano | Bahia and Sergipe | |||

| Gaúcho | Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay | |||

| Mineiro | State of Minas Gerais | |||

| North Estino | Audio sample | Northeastern states of Brazil | ||

| Nortista | Amazon basin | |||

| Paulistano | Between megalopolis São Paulo to the west to do border with state of Rio de Janeiro to the east | |||

| Sertanejo | States of Goiás , Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul | |||

| Sulista | State of Santa Catarina and the central-southern state of Paraná | |||

| Africa | ||||

| Luandense (Angolano) | Audio sample | Angola - region of the capital Luanda | ||

| Benguelense | Audio sample | Angola - Benguela Province | ||

| Sulista | Audio sample | Angola - south of the country | ||

| Caboverdiano | Audio sample | Cape Verde | ||

| Guinean | Audio sample | Guinea-Bissau | ||

| Moçambicano | Audio sample | Mozambique | ||

| Santomense | Audio sample | Sao Tome and Principe | ||

| Asia | ||||

| Timorense | Audio sample | East Timor | ||

| Macaense | Audio sample | Macau , China | ||

| Audio samples from Instituto Camões , Portugal: www.instituto-camoes.pt | ||||

Some examples of words that have different names in Portugal than in Brazil or Angola are given below:

| Germany | Portugal | Brazil | Angola |

|---|---|---|---|

| pineapple | ananás ¹, sometimes abacaxi ² | abacaxi ², sometimes ananás ¹ | abacaxi ², sometimes ananás ¹ |

| go away, go away | ir embora ¹ (or bazar ³ among young people) | ir embora ¹ (or v azar among young people) | bazar ³, ir embora ¹ |

| bus | autocarro ¹ | ônibus ² | machimbombo ³ |

| mobile phone | telemóvel ¹ | celular ² | telemóvel ¹ |

| Slum, barracks settlement | bairro de lata ¹ | favela ² | musseque ³ |

¹ Portuguese origin ² Brazilian origin ³ Angolan origin ( Machimbombo probably has Mozambican origin)

Differences in the written language

Until the Acordo Ortográfico came into force in 2009, Portuguese had two variants of the written languages (Port. Variedades ), which are often referred to as padrões (standards). These are:

- European and African Portuguese

- Brazilian Portuguese

The differences between these variants concern the vocabulary , the pronunciation and the syntax , especially in the colloquial language , whereas in the language of the upper classes these differences are smaller. However, these are dialects of the same language, and speakers of the two variants can easily understand the other.

Some vocabulary differences are not really any. In Brazil, the standard word for 'carpet' is wallpaper. In Portugal they tend to use alcatifa. However, there is also the regional expression tapete in Portugal , just as there is the regional expression alcatifa in Brazil . For old words this is almost generally true, while in new words these differences are indeed country-specific, such as ônibus in Brazil and autocarro in Portugal.

Up to the Acordo Ortográfico, there were more significant differences in orthography . In Brazil , words that contain cc, cç or ct leave out the first c , and words that contain pc, pç or pt have no p . These letters are not pronounced, but rather represent relics from Latin that have mostly been eliminated in Brazil. Compare with Italian.

A couple of examples are:

| Latin | Portugal and Africa | Brazil | Italian | Spanish | translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| actio | acção | ação | azione | acción | Deed, action |

| directio | direcção | direção | direzione | dirección | direction |

| (electricus) | eléctrico | elétrico | elettrico | eléctrico | electric |

| optimus | óptimo | ótimo | ottimo | óptimo | Great |

There are also some differences in the accentuation, which are due to the following reasons:

- Different pronunciation: In Brazil, the o is pronounced closed in Antônio, anônimo or Amazônia , whereas in Portugal and Africa it is spoken openly. That is why in Portugal and Africa one writes António, anónimo or Amazónia.

- Simplification of reading: the combination qu can be read in two different ways: ku or k. To make reading easier, in Brazil the u is written with a trema when the pronunciation is ku , i.e. cinqüenta instead of cinquenta (fifty) . However, this is no longer provided for in the last spelling reform (see below).

A spelling reform was passed with the Acordo Ortográfico in 1990 to achieve an international standard for Portuguese. However, it took until 2009 for the agreement to enter into force in Portugal and Brazil, after it was ratified in 2008 by those two countries, as well as Cape Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe (later Guinea-Bissau; Angola and Mozambique have to date - as of October 2014 - not ratified). As part of this reform, the above-mentioned c in cc, cç or ct and p in pc, pç or pt were largely omitted in Portugal , there were also minor standardizations and attempts are made to adopt a coordinated approach with regard to new loanwords from other languages to agree. Since then, the spelling in Brazil and Portugal has been largely identical, with only a few differences.

Languages derived from Portuguese

When Portugal began to build its colonial empire in the Middle Ages, the Portuguese language came into contact with the local languages of the conquered areas and mixed languages ( pidgins ) emerged, which were used as lingua franca in Asia and Africa until the 18th century . These pidgin languages expanded their grammar and lexicon over time and became the slang languages of ethnically diverse populations. They exist under the following names in the following areas:

Guinea-Bissau and Senegal :

- Crioulo / Kriol

India :

- Creole language of Diu

- Creole language of Vaipim

- Kristi

- Língua da Casa

Macau :

- Cristão / Papiá Kristang

Netherlands Antilles and Aruba :

Suriname :

Some hybrid dialects exist where Spanish and Portuguese meet:

- A fala in Spain

- Barranquenho in Portugal

- Portuñol in Uruguay

phonetics

The Portuguese language has a very complex phonetic structure, which makes it particularly interesting for linguists. The language has 9 vowels , 5 nasal vowels, 10 diphthongs , 5 nasal diphthongs, and 25 consonants .

Vowels

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consonants

| bilabial | labiodental | dental | alveolar | postalveolar | velar | guttural | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p | b | t | d | k | G | ||||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | |||||||||||

| Fricatives | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ʁ | |||||||

| Approximants | l | ɾ | ʎ | |||||||||||

Stress point

In Portuguese, the stress (also word accent) of words that orthographically end with the vowels a , e or o and an s or m is on the penultimate vowel, whereas the stress on words that orthographically end with i , u or end a consonant (usually l, r, z ), located on the final syllable. An emphasis deviating from this rule is indicated by a diacritical mark ( acute or circumflex ). By Tilde marked syllables are always stressed unless another syllable carries a acute or circumflex.

Examples:

- bel e za 'beauty' - emphasis on the second e

- f o nte 'source' - emphasis on the o

- obrig a do 'thank you' - emphasis on the a

- ped i 'I asked' - emphasis on the i

- tat u 'armadillo' - emphasis on the u

- Bras i l 'Brazil' - emphasis on the i

- cant a r 'sing' - emphasis on the second a

- s á bado 'Saturday' - emphasis on the first a

- combinaç ã o 'combination' - emphasis on the ã

- Crist ó vão 'Christoph' - emphasis on the first o

Unlike French and Spanish, Portuguese is more of an accent counting language.

Orthography and pronunciation

alphabet

The Portuguese alphabet uses 23 letters of the Latin alphabet - A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, X, Z - and makes no use of K, W and Y outside of names. In 2009 a spelling reform was carried out with the Acordo Ortográfico , which takes these letters back into the alphabet.

In addition, the following letters are used with diacritics: Á, Â, Ã, À, Ç, É, Ê, Í, Ó, Ô, Õ, Ú, Ü

pronunciation

The following pronunciation hints apply to both European and Brazilian Portuguese; if there are differences, they are indicated with the respective sound.

Vowels

| Letter | Portuguese | meaning | IPA | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | t a lha | cut | a | like German: w a nn |

| a | a mo | (I am in love | ɐ | before nasal as in German: Wass er |

| a, á | a lto, á rvore | high, tree | ɑ | "Dark" a, back vowel |

| e, ê | m e do, l e tra, voc ê | Fear, letter, you¹ | e | like in German e wig |

| -e | lead e, val e | Milk, valley | P .: ɯ̆ or ɨ Br .: i |

at the end of the word: P: short, almost swallowed i at the end of the word: Br .: i often spoken in full tone |

| e, é | r e sto, f e sta, caf é | Rest, party, coffee | ɛ | open e as in E nde |

| i | i d i ota | idiot | i | as in the German F i nal |

| O | o vo, o lho, av ô | Egg, eye, grandfather | O | closed o, like O pa |

| -O | sant o, log o | holy, soon | u | o as final: like short -u |

| o, ó | m o rte, m o da, n ó | Death, fashion, knots | ɔ | Accented in the middle of the word or at the end: open o as in P o st |

| u | u vas | grapes | u | like German Bl u t |

| Diphthong with o or u | a o, ma u | too bad | w | very dark German u to w |

| Diphthong with i | nac i onal, ide i a | national, idea | j | Like a German j or similar to the pronunciation of i in nat i onal |

¹ você often also stands for you in Brazilian

Nasal vowels

The Portuguese nasal vowels are not as complete pronounced nasally as in French and usually are in Portuguese and not consonant at the end of the nasal. In some publications z. For example, the pronunciation of the nasal vowel ã is given as ang , which is not correct, because the nasalized vowels are a single nasal sound.

| Letter | Portuguese | meaning | IPA | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| am, an, ã | c am po, maç ã | Field, apple | ɐ̃ | nasalized a similar to the vowel in French blanc |

| em, en | l em brar, en tão | remember then | ẽ | nasalized e |

| un, um | um, un tar | one, grease | ũ | nasalized u |

| in, in | l im bo, br in car | Limb, play | ĩ | nasalized i |

| om, on, õ | lim õ es, m on tanha | Lemons, mountain | O | nasalized o, similar to the French on |

Consonants

| Letter | Portuguese | meaning | IPA | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | b ola | ball | b | like in German |

| ca, co, cu | c asa | House | k | like German k, but not breathy |

| ça, ce, ci, ço, çu | ce do, ma ç ã | early, apple | s | voiceless s as in Fa ss |

| ch | ch eque | check | ʃ | unvoiced sh as in Sch ule, but weaker than in German |

| d | d edo | finger | d dʒ |

as in German d ann in Brazilian before a pronounced -i- (which includes many orthographic -e- s) extremely soft or voiced, almost like dʒ, whereby the strength of the following sibilance varies from region to region. |

| f | f erro | iron | f | as in f ÜR |

| ga, go | g ato | cat | G | as g deal |

| ge, gi | g elo | ice | ʒ | as j in J ournal or g in G enie |

| gua | á gu a | water | gu to gw | g with very dark u, going into w |

| gue, gui | portu gu ês, gu ia | Portuguese, guide | G | wie g ehen, the u is not spoken , just like in French ( guerre , guichet ) |

| H | h arpa | harp | ∅ | is not pronounced |

| j | j ogo | game | ʒ | as j in J ournal or g in G enie |

| l | l ogo | soon | l | like L amm |

| -l | Portuga l, Brasi l | Portugal, Brazil | P .: ł Br .: w |

P .: dark l (like the Cologne l ) Br .: like u, English w or the Polish ł or like even darker l |

| lh | a lh o, fi lh o | Garlic, son | ʎ | like a lj in German or the gl in Italian ( fi gl io ) |

| m- | m apa | map | m | Beginning / interior of a word: as in German at the end of a word: nasalises the preceding vowel |

| n- | n úmero | number | n | Beginning / interior of a word: as in German at the end of a word: nasalises the preceding vowel |

| nh | ni nh o | nest | ɲ | like an nj in German or the gn in French ( Auba gn e ) or Italian (lasagne) |

| p | p arte | part | p | like in P a p ier, but bare |

| qua, quo | qu anto, qu otidiano | how much, daily | kw | a k and very dark u |

| que, qui | a qu ele, a qu i | that one here | k | as in German K atze |

| -r | ma r, Ma r ço | Sea, March | ɾ | sometimes slightly rolled, often suppository-r , sometimes voiceless at the end of the word |

| r | co r o, ca r o | Choir, expensive | r | usually slightly rolled (simply flick the tongue) |

| r, rr | r osa, ca rr o | Rose, car | P .: r Br .: h |

P .: suppository-r; regionally spoken longer, d. H. more strongly rolled r than above Br .: h or ch (soft ah sound) or uvula-r |

| s, ss | s apo, a ss ado | Toad, grilled | s | in the initial or inside the word as in barrel |

| -s | galinha s, arco s | Chickens, bows | ʃ, s or z | in final in Portugal, Rio de Janeiro and Belém (Pará) ʃ (like the sh in Sch ule); in the other regions of Brazil mostly s or with the following voiced loud like z (like the s in Wie s e); in some Portuguese dialects ʒ (like the j in J ournal) |

| s | ra s o | uniformity | z | if there is a vowel before and after the s , as in Germany the s in Wie s e, in English ea s y |

| t | t osta | toast | t tʃ |

as in German, but not breathy in Brazilian before a pronounced -i- (which includes many orthographic -e- s) extremely soft or voiced, almost like tʃ, whereby the strength of the following sibilance varies from region to region; often spoken like the Russian verb ending -ть. |

| v | v ento, u v a | Wind, grapes | v | like the w in w o |

| x | cai x a, x adrez pró x imo e x emplo tá x i, tó x ico |

Box, chess next example taxi, toxic |

ʃ s z ks |

unvoiced sh as in Sch ule often at book words in the word inside as Fa ss if the emphasis of x is (analogous to Verner's Law ). often with book words inside the word as in Wie s e, if the stress is behind the x (analogous to Verner's law). as in Ma x for learned words or foreign words |

| z | nature z a | nature | z | like in Germany the s in Wie s e, English z ero |

grammar

Nouns

Pleasure . Usually nouns ending in -o are masculine and nouns ending in -a are feminine. But there are also exceptions ( o problema , o motorista ). The gender is indicated by the preceding article (male: o ; female: a ). There are also numerous nouns that end in other vowels ( o estudante - the student; o javali - the wild boar; o peru - the turkey), on diphthongs ( a impressão - the impression; o chapéu - the hat) or on consonants ( o Brasil - Brazil; a flor - the flower).

Number . The plural is generally formed by adding -s to the noun (o amigo - os amigos; a mesa - as mesas; o estudante - os estudantes). Changes are made to nouns that end in a consonant. If -r, -z and -n are final, -es is appended in the plural. Some nouns that end in -s and are stressed on the penultimate or third last syllable are immutable in the plural (o ônibus - os ônibus; o lápis - os lápis). A final -m before the plural S becomes -n (o homem - os homens). The final -l is vocalized in the plural to -i- (o animal - os animais; o papel - os papéis; o farol - os faróis). The plural forms of the nouns ending in -ão are special. Depending on the etymology of the word, these nouns form different plural forms (o irmão - os irmãos; o alemão - os alemães; a informação - as informações).

Augmentative / diminutive . The meaning of a noun can be changed by adding suffixes. The augmentative suffix -ão can be used to create an enlargement: o nariz - o narigão (the giant nose). The situation is similar with the diminutive ( diminutive ) by the suffix -inho / -inha: o nariz - o narizinho (the nose).

items

Definite article . The definite article in Portuguese was derived from the Latin demonstrative pronoun illeg (that). In old Portuguese, the forms el (preserved today as a relic in the form of address for the king "El-Rei"), lo , la , los and las can be found. Due to the phonetic development, the initial l- fell away, so that today's forms were created. The old Portuguese form has been retained in some regional expressions (mais + o → mai-lo).

| Masculine | Feminine | |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | O | a |

| Plural | os | as |

The definite article is used in Portuguese to identify words when they are already known or when a new statement is made about them. In addition, the specific article can substantiate words ( o saber - the knowledge). As in some German substandard varieties , the definite article is almost always used in Portuguese before the proper name: Eu sou o João. (I am the . Hans) Even before possessive pronouns, the definite article is often: O João é o meu amigo. (Hans is my friend.)

Similar to Italian, the Portuguese article is connected to certain prepositions (a / de / em / por). The connection of the preposition a with the feminine article a is indicated by a grave accent : à . This phenomenon is called Krasis (port: crase).

| m.sg. | m.pl. | f.sg. | f.pl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a (to, in) | ao | aos | à | às |

| de (from) | do | DOS | there | the |

| em (in) | no | nos | n / A | nas |

| por (through) | pelo | pelos | pela | pelas |

Indefinite article . The indefinite article was derived from the Latin numeral unus, una, unum . It is used to introduce and present previously unknown nouns. It individualizes and defines words that have not previously been specified.

| Masculine | Feminine | |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | around | uma |

| Plural | us | umas |

The indefinite article is combined with the preposition em , in Portugal seldom also with the preposition de to form a so-called article preposition .

| m.sg. | m.pl. | f.sg. | f.pl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| de (from) | dumb | duns | duma | dumas |

| em (in) | num | well | numa | numas |

adjective

In Portuguese, the adjective is used to define nouns more precisely. It must match the noun it refers to in number and gender.

As a rule, the adjectives in Portuguese are placed after the noun (Como uma maçã vermelha - I am eating a red apple.) However, some adjectives are also placed in front of the noun. These include the superlative forms (o melhor amigo: the best friend). Some adjectives get a small change in meaning through the prefix (um homem grande: a great man; um grande homem: a great man). Advance booking is also possible for stylistic reasons. This gives the meaning of the noun a subjective component.

Adjectives can be increased. As a rule, the first step ( comparative ) is formed by prefixing the word mais (more) or menos (less): O João é mais inteligente. A Carla é menos intelligent. If one wants to express in comparison with what something is more or less, one connects the comparison with do que (as): O João é mais inteligente do que a Carla.

The second form of increase ( superlative ) exists in two forms. On the one hand as a relative superlative, which expresses what is the maximum in comparison: O João é o aluno mais estudioso da escola (João is the hardest working student at the school, i.e. compared to all other students.) The absolute superlative does not indicated what the comparative figure is. This form is expressed by adding the suffix -íssimo / -íssima or by the elative with muito (very): O João é inteligent íssimo / muito inteligente (João is very intelligent.)

Some frequently occurring adjective forms form irregular forms: bom - melhor - o melhor / ótimo; ruim - pior - o pior / péssimo; grande - maior - o maior / máximo; pequeno - menor - o menor / minimo.

Verbs

Verbs are divided into three conjugations, which are differentiated according to the infinitive ending (either -ar, -er or -ir ), with most verbs belonging to the -ar group. These verbs then follow the same conjugation rules. Similar to German, there are the imperative (o imperativo), the indicative ( o indicativo) and the subjunctive ( subjuntivo o conjuntivo ), whereby the rules of when to use the subjunctive are stricter in Portuguese and the use of German The subjunctive deviates considerably or largely corresponds to the use of the Spanish subjuntivo .

Another special feature is the so-called personal infinitive (infinitivo pessoal) . This denotes infinitive forms that have a personal ending. Example: Mostro-te para saber es disso. (I'll show you so that you know about it - literally: for you know (-you) about it).

Salutation

In Portuguese, as in most Indo-European languages, there are two forms of address, one of proximity (tu) and one of distance (o senhor / a senhora) . The original form of the second person plural (vós) has hardly any meaning today, apart from a few dialects in northern Portugal and the biblical sacred language used in worship . In addition, in Brazil, the polite form of address vossa mercê (Your Grace) has developed into the short form você , which is used with the third person singular of the verb. This form of address is the normal form of everyday life in most regions of Brazil. Seen in this way, Brazilians practically always siege each other (example: Você me dá seu livro? - will you give me your book? - actually: give me your book?) It is interesting that the você form has a greater semantic breadth than the German one You-form. This means that where you would use the Sie-form in German, you can definitely use the você -form in Brazil . In Portugal, this form is used as a familiar you , for example among work colleagues of the same rank or among older neighbors. O senhor / a senhora is restricted to very formal situations. In both language variants, the plural form vocês has completely replaced the old vós .

Language example

Universal Declaration of Human Rights , Article 1:

- Todos os seres humanos nascem livres e iguais em dignidade e em direitos. Dotados de razão e de consciência, devem agir us para com os outros em espírito de fraternidade.

- All people are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should meet one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

vocabulary

Since Portuguese is a Romance language , most Portuguese words come from the Latin language. However, one can also observe traces of other languages with which Portuguese had contact:

Pre-Roman loanwords

There are few words from the time before the Roman rule of Hispania that can be derived from the language of the indigenous people of today's Portugal ( Lusitans , Konii, Iberians ) or from the language of settlers ( Phoenicians , Carthaginians or Celts or Celtiberians ) to modern Portuguese have received. For many of these words, however, there is no precise scientific proof of their origin ( etymology ). The Celtisms in particular could be words that got into Portuguese via Latin.

Iberisms :

- arroio 'stream, stream'

- caçapo 'young rabbit'

- cama 'bed'

- manteiga 'butter'

- sovaco 'armpit (cave)'

Celtisms:

- bostar 'Kuhweide' (from Celtiberian boustom 'cowshed'; compare old Galician busto 'cow farm ')

- bugalho 'gall, gall apple'

- canga 'yoke' (from * cambica , formed to cambos 'crooked'; see old Irish camm )

- Colmeia , beehive '(from * colmos ;. cf. leonesisch cuelmo , straw, straw', m . Bret coloff , stems, stem ')

- garça 'heron' ( cf.bret . kerc'heiz )

- lavego 'wheel plow'

- sável 'Alse' (from samos 'summer'; see Spanish sábalo 'Alse', cat. saboga 'ds.', old Irish sam 'summer')

- seara 'plowed field' (cf. old Galician senara , Spanish serna ; old Irish sain 'alone')

Since practically all of these words of Celtic origin are also recorded in other Romance languages, it stands to reason that they were already borrowed from Celtic by the Romans and then entered Portuguese as Latin words.

- malha 'mesh, net'

- mapa 'map'

- saco 'sack'

The same applies here: These words are also used in other Romance languages. It is therefore obvious that they were already borrowed from Phoenician (or another language) by the Romans and then entered Portuguese as Latin words.

Hereditary words of Latin origin

Portuguese is a derivative of Vulgar Latin , which is related to classical Latin , but not identical. The transformation from Latin to today's Portuguese words began in some cases during the Roman Empire , with other words this process began later. The Portuguese language has been influenced again and again by the Latin; later words from the written Latin language of the Middle Ages and early modern times also found their way into Portuguese. These so-called book words have changed little compared to the Latin form, while the words that arose from spoken Latin ( hereditary words ) have changed significantly.

The processes by which Latin hereditary words became Portuguese words are in detail:

-

Nasalization : A vowel before [m] and [n] easily becomes a nasal vowel, this is a phenomenon that exists in many languages. In Portuguese this happened between the 6th and 7th centuries, in contrast to Spanish, where this change in vowel pronunciation never occurred.

- Latin luna first becomes old Portuguese lũa [ˈlũ.a] then new Portuguese lua [ˈlu.a] 'moon'.

-

Palatalization : an adjustment before the vowels [i] and [e], or near the semi-vowels or the palatal [j]:

- centum > * tʲento > altport. cento [t͡sẽnto]> cen [t͡sẽⁿ]> neuport. cem [sẽj̃] 'hundred'

- facere > * fatʲere > * fatˢer > altport. fazer [fa.ˈd͡zeɾ]> neuport. fazer 'make'

- had an older evolution: fortia → * fortˢa > força [ˈfoɾ.sɐ] 'strength, strength'

-

Elimination of lateral or nasal single consonants between vowels:

- dolor > door [do.ˈoɾ]> dor 'pain'

- bonus > bõo [ˈbõ.o]> bom 'good'

- ānellus > * ãelo > elo 'Ring' (next to it anel [ɐ.ˈnɛɫ])

-

Lenization - weakening the consonant strength between vowels:

- mūtus > mudo [ˈmu.ðu] 'deaf'

- lacus > lago [ˈla.ɡu] (Brazil)> [ˈla.ɣu] 'lake'

- faba > fava ' broad bean'

-

Geminate Simplification - Simplification of double consonants:

- gutta > gota 'drops'

- peccare > pecar ' to sin'

-

Dissimilation - dissimilarity of two adjacent similar sounding sounds

- Vowel dissimilation:

- locusta > lagosta 'lobster'

- campāna > campãa [kam.ˈpãa]> * [ˈkã.pɐ]> campa [ˈkɐ̃.pɐ] 'grave'

- Consonant dissimilation:

- memorāre > nembrar > lembrar 'remember'

- anima > alma 'soul'

- locālem > logar > lugar 'place'

- Vowel dissimilation:

Germanisms

- agarimar 'cuddle; to stow in bed '

- britar 'break' (from Suebian * briutan; see swed. bryta , mhd. briezen )

- ervanço 'chickpea' (from Gothic * arweits 'pea')

- fona 'spark' (from Suebian)

- gaita 'bagpipes' (from Gothic gaits 'goat', cf. German Bockpfeife )

- laverca 'Lerche' (from Suebian * laiwerka )

- loução 'elegant' (outdated "haughty", from Gothic flautjan ' to brag')

- luva 'glove' (from Gothic * lōfa )

- trigar 'push' (from Gothic þreihan 'contradict')

Arabisms

About a thousand words in Portuguese are Arabic loanwords , for example:

- alface 'leaf salad' from al-khass

- almofada 'pillow' from al-mukhadda

- armazém 'camp' of al-mahazan

- azeite 'olive oil' from az-zait

- garrafa 'bottle' by garrafâ

- javali 'wild boar', from * ǧabalí , to old Arab. ǧabalī (جبلي) 'mountainous'

Loan words of African, Asian and Indian origin

Through the discoveries, Portuguese came into contact with local African, Asian and Native American languages, many of which the Portuguese language absorbed and passed on to other European languages. Geographical names in Africa and Brazil in particular go back to the languages of the inhabitants of these regions.

Asian languages:

Indian words:

- abacaxi 'pineapple' from the Tupi language ibá and cati

- caju 'cashew nut' or 'cashew nut'

- jaguar 'Jaguar' from the Tupi - Guaraní jaguara

- mandioca 'cassava'

- pipoca 'popcorn'

- tatu 'armadillo' from the Guaraní tatu

- tucano 'toucan' from the Guaraní tucan

African languages:

- banana 'banana' from the Wolof

- farra 'wild celebration' from the Bantu

- chimpanzé 'chimpanzee' from the Bantu

Portuguese literature

In early Portuguese literature, poetry was of paramount importance. One of the most famous Portuguese writers is Luís de Camões (1524–1580), who created one of the most important works with the epic Die Lusiaden . Its importance is illustrated not least by the fact that the Portuguese equivalent of the German Goethe Institute is called Instituto Camões and Portugal's national holiday ("Dia de Portugal" - Day of Portugal) was set on June 10, the anniversary of the death of the national poet .

Other important authors are the novelist Eça de Queirós (1845–1900), the poet Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935), the Brazilian poet and novelist Machado de Assis (1839–1908), the Brazilian novelist Jorge Amado (1912–2001), and the Nobel Prize for Literature, José Saramago (1922–2010).

Language regulation

The Portuguese language is regulated by

- the International Portuguese Language Institute

- the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP)

See also

literature

- Aurélio Buarque de Holanda Ferreira: Novo Dicionário Aurélio da Língua Portuguesa. Positivo, Curitiba 2004, ISBN 85-7472-414-9 .

- Emma Eberlein O. F. Lima, Lutz Rohrmann, Tokiko Ishihara: Avenida Brasil. EPU, São Paulo 1992, ISBN 85-12-54700-6 (Introduction to Brazilian Portuguese).

- Emma Eberlein O. F. Lima, Samira A. Iunes, Marina R. Leite: Diálogo Brasil. EPU, São Paulo 2002, ISBN 85-12-54220-9 (intensive course).

- A. Endruschat, J. Schmidt-Radefeldt: Introduction to Portuguese Linguistics. 2nd Edition. Narr, Tübingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8233-6177-0 .

- Erhard Engler : Textbook of Brazilian Portuguese. 6th edition. Langenscheidt, Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-324-00516-7 .

- Celso Ferreira da Cunha, Luís F. Lindley Cintra: Nova gramática do português contemporâneo. 18th edition. Edições João Sá da Costa, Lisbon 2005, ISBN 972-9230-00-5 .

- Günter Holtus , Michael Metzeltin , Christian Schmitt (Hrsg.): Lexicon of Romance Linguistics . 12 volumes. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1988-2005; Volume VI, 2: Galegic / Portuguese. 1994.

- António Houaiss: Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa. Temas & Debates, Lisbon 2003, ISBN 972-759-664-9 (Portuguese edition).

- Maria Teresa Hundertmark-Santos Martins: Portuguese Grammar. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1998, ISBN 3-484-50183-9 (complete presentation of the grammatical phenomena of the Portuguese language, but largely without taking Brazilian Portuguese into account).

- Joaquim Peito: Está bem! Intensive Portuguese course. Butterfly, Stuttgart 2006.

- Matthias Perl et al .: Portuguese and Crioulo in Africa. History - grammar - lexicon - language development. University Press Dr. N. Brockmeyer, Bochum 1994.

- Vera Cristina Rodrigues: Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa. Objetiva, Rio de Janeiro 2003, ISBN 85-7302-488-7 (the largest dictionary, monolingual, with Portuguese and Brazilian spelling before AO90 ).

- Helmut Rostock: Textbook of the Portuguese language. 5th edition. Buske, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-87548-436-6 .

Web links

- Comunidade dos Países de Lingua Portuguesa

- German Lusitanistics website

- Portuguese vocabulary training

- Practice Portuguese verbs online

Individual evidence

- ↑ bmas.de

- ↑ Congo passará a ensinar português nas escolas (2010)

- ↑ 110 mil lusófonos na Namíbia (2012)

- ↑ Interest pelo português cresce na Namíbia (2016)

- ↑ A língua portuguesa no Senegal ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (2006)

- ↑ 17 mil senegaleses estudam português no ensino secundário (2008)

- ↑ Senegal - ensino da língua portuguesa ( Memento of July 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (2011)

- ↑ Speech Angola: Somos 24.3 milhões

- ^ A b John Hajek: Towards a Language History of East Timor ( Memento of December 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) in: Quaderni del Dipartimento di Linguistica - Università di Firenze 10 (2000): pp. 213-227.

- ↑ Direcção-Geral de Estatística : Results of the 2015 census , accessed on November 23, 2016.

- ↑ The languages of East Timor ( Memento of March 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Speech Angola: redeangola.info

- ↑ Bertil Malmberg: La America hispanohablante . Madrid 1966, p. 29.

- ^ Paul Teyssier: História da Língua Portuguesa. Sá da Costa, Lisbon 1993 (5th edition), pp. 3, 13.

- ↑ Endruscht; Schmidt-Radefeldt: Introduction to Portuguese Linguistics. Narr, Tübingen 2008 (2nd edition), p. 32.

- ↑ Esperança Cardeira: O Essencial sobre a História do Português. Caminho, Lisbon 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Paul Teyssier: História da Língua Portuguesa. Sá da Costa, Lisbon 1993 (5th edition), p. 21.

- ↑ Esperança Cardeira: O Essencial sobre a História do Português. Caminho, Lisbon 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ Rafael Lapesa: Historia de la lengua española. Madrid 1988, p. 176 ff.

- ^ Paul Teyssier: História da Língua Portuguesa , p. 94. Lisboa 1987

- ↑ Portal da Língua Portuguesa: História da Ortografia do Português

- ↑ Handbook of the International Phonetic Association pp. 126-130.

- ↑ Brazil's alphabet now complete. January 2, 2009, accessed September 5, 2009 .

- ↑ Raquel Master; Ko. Friday: ASPECTO INERENTE E PASSADO IMPERFECTIVO NO PORTUGUÊS: ATUAÇÃO DOS PRINCÍPIOS DA PERSISTÊNCIA E DA MARCAÇÃO. Alfa, São Paulo, 55 (2): 477–500, 2011 (PDF)

- ↑ Volker Noll: The Arabic article al and the Iberoromanic ( Memento of January 2, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 210 kB)

- ↑ The Lusiads. In: World Digital Library . Retrieved September 15, 2018 .