Rudolf I. (HRR)

Rudolf I. (* 1. May 1218 , † 15. July 1291 in Speyer ) was as Rudolf IV. From about 1240 Graf von Habsburg and from 1273 to 1291, the first Roman-German king of the sex of the Habsburgs .

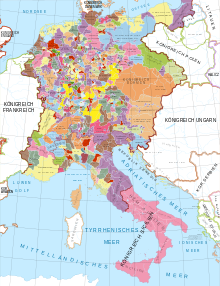

With the death of Emperor Frederick II in December 1250, the so-called interregnum ("period between the kings") began, during which kingship in the empire was only weak. During this time, Rudolf rose to become one of the most powerful territorial lords in the south-west of the empire. The interregnum ended with his election as Roman-German king (1273). As king, Rudolf tried to regain (revindicate) the imperial property, which had been almost completely lost since around 1240 . He was particularly successful in Swabia, Alsace and the Rhineland. The north of the empire, on the other hand, was largely out of reach. In relation to the powerful Bohemian King Ottokar , Rudolf had to enforce the recognition of his royal rule and the revindications militarily. His victory in the Battle of Dürnkrut (1278) established the Habsburg rule in Austria and Styria . The House of Habsburg rose to become an imperial dynasty. Rudolf recognized the importance of cities for his own royal rule. However, his tax policy generated considerable urban opposition. Rudolf tried in vain to achieve the dignity of emperor and to appoint one of his sons as a successor in the Roman-German Empire during his lifetime.

Life

Origin and youth

Rudolf came from the noble family of the Habsburgs . The family can be traced back to a Guntram who lived around the middle of the 10th century . Guntram's grandchildren included Radbot and Bishop Werner von Straßburg . One of the two is said to have built the Habichtsburg / Habsburg around 1020/30. The Habichtsburg was in Aargau and gave the family its name. In 1108, Otto II was the first family member to be assigned the surname ( comes de Hauichburch ). The Habsburg possession was based on the allod between the Reuss and Aare with the eponymous castle and monastery bailiots in northern Switzerland and Alsace. The Habsburgs were bailiffs of the Ottmarsheim and Muri monasteries they founded . In the course of the 12th century they gained the landgraviate in Upper Alsace. There the family owned extensive estates between Basel and Strasbourg.

Rudolf emerged from the marriage of Albrecht IV of Habsburg with Heilwig, a countess of Kyburg . The assumption that Rudolf's place of birth was Limburg goes back to an arbitrary statement by Fugger - Birken . Rudolf's father Albrecht IV shared the rule with his brother Rudolf III in 1232 . from which the Laufenburg line of the Habsburgs was derived. According to the chronicler Matthias von Neuenburg from the middle of the 14th century, the Hohenstaufen emperor Friedrich II was Rudolf's godfather. But Rudolf was not brought up at the royal court. He knew neither the script nor Latin. Rudolf had two brothers, Albrecht and Hartmann, and two sisters, Kunigunde and an unknown name. Albrecht was earmarked for a spiritual career at an early age. Rudolf's father Albrecht IV went on a crusade in the summer of 1239 . When news of his death arrived in 1240, Rudolf took over the sole rule of the main Habsburg line. Hartmann moved to northern Italy in late 1246 or early 1247 to fight for Emperor Friedrich II. He died in captivity between 1247 and 1253.

Count of Habsburg (approx. 1240–1273)

Rudolf continued the close ties between the Habsburgs and the Staufers. In the bitter disputes between Emperor Friedrich II and the papacy, Rudolf and his younger brother Hartmann were on the Hohenstaufen side. In 1241 Rudolf stayed at the court of Emperor Frederick II in Faenza . In the early 1240s he led a feud with Hugo III. von Tiefenstein / Teufen for his property, at the end of which Hugo was probably murdered on behalf of Rudolf. After the death of Frederick II in 1250, Rudolf remained loyal to the Hohenstaufen as a close follower of Conrad IV . He was therefore banned from church. Around 1253 he married Gertrud von Hohenberg . With the Albrechtstal northwest of Schlettstadt as a marriage estate, Rudolf was able to further increase his Alsatian property. After the death of Conrad IV in 1254, he made a lasting peace with the Curia and was exempt from church; he was able to retain his significant influence on the Upper Rhine and in northern Switzerland.

The double election of 1257 brought the empire two kings with Alfonso X of Castile and Richard of Cornwall . The time between the death of Frederick II and Rudolf von Habsburg's election as king in 1273 is known as the so-called interregnum (" period between the kings "). The term, which only became common in the 18th century, does not mean a period without a king or an emperor, rather this time is characterized by an "oversupply of rulers" who hardly exercised rulers. The long prevailing image of the interregnum as a particularly violent and chaotic time compared to other epochs was revised by Martin Kaufhold (2000). Kaufhold referred to the arbitration and other resolution mechanisms for conflicts during this time. On the other hand, Karl-Friedrich Krieger (2003) stuck to the traditional assessment and relied on the perception of contemporaries who perceived this period as particularly violent. According to Krieger, the “tendency towards violent self-help” was particularly pronounced in the Upper Rhine region and in northern Switzerland. Count Rudolf von Habsburg also used force as a means against weaker competitors to expand his territorial rule. In violent arguments with Heinrich III. , the Bishop of Basel, he was able to secure the Vogtei (secular protectorate) over the Black Forest Monastery of Sankt Blasien in 1254 . In an alliance with the Strasbourg citizens, Rudolf prevailed against the Strasbourg bishop Walter von Geroldseck in the battle of Hausbergen in March 1262 . When the Counts of Kyburg died out in 1264, Rudolf asserted the inheritance in bitter conflicts against Count Peter of Savoy , who was also related to the Kyburg family and claimed the inheritance. The cities of Winterthur , Diessenhofen , Frauenfeld and Freiburg im Üchtland as well as the county of Thurgau came into his possession. Compared to the Hohenstaufen or the overpowering Bohemia Ottokar II , Rudolf remained a poor count despite these territorial successes.

The royal election of 1273

Alfonso of Castile never came to the kingdom. Richard of Cornwall was crowned in Aachen, but his few stays in the empire concentrated on the areas west of the Rhine. After Richard's death in 1272, the princes wanted to raise a new king despite the existing claims of Alfonso of Castile. Alfons tried in vain to prevent a new election with a delegation to the Pope and to achieve recognition of his kingship. Pope Gregory X. was open to a new beginning in the empire. According to the Pope's ideas, a generally recognized ruler as emperor should take the lead in a new crusade . However, the Pope wanted to leave the decision to the princes and only approve the elected person , i.e. confirm his or her suitability for the Empire. However, a candidate who would have met strong resistance from the Curia would not have been enforceable. In view of the bitter conflicts between the Popes and the Hohenstaufen dynasty, the Curia would not tolerate an applicant with close ties to this sex. Similar to the previous royal elections, there were also numerous applicants for the royal crown this time. As ruler of southern Italy and Sicily, Charles of Anjou tried his nephew, the young French king Philip III. to assert himself as Roman-German king with the Pope. Pope Gregory X refused, however, because this connection between France and the empire would have brought the papacy a powerful enemy north of Rome. Ottokar also sent an embassy to the Pope to recommend himself as a candidate for king. Both candidates assumed that the Pope would make the binding decision and not the princes who were divided in the past. In the subsequent negotiations, however, the princes succeeded in building consensus among themselves and in reaching collegial and thus binding decisions, whereupon the Pope left the decision to them.

Ottokar von Böhmen could not secure the support of the Pope, but in view of his impressive position of power, which he had created through territorial acquisitions, the princes could not simply ignore him. After the Babenbergs died out in 1246, Ottokar took over the Duchy of Austria in 1251 . In the following years the Duchy of Styria (1261), the Egerland (1266), the Duchy of Carinthia , Carniola and the Windische Mark with Pordenone in Northern Italy (1269) were added; his possessions ranged from the Ore Mountains to the Adriatic Sea .

From the end of the 12th century to the middle of the 13th century, a narrower circle of special royal voters ( electors ) had formed, who succeeded in excluding others from being eligible to vote. The three Rhenish archbishops of Mainz, Trier and Cologne, as well as the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg and the King of Bohemia belonged to the royal electors. Intensive negotiations about a candidate for a king were conducted throughout 1272. The Landgrave of Thuringia Friedrich I the Freidige raised high hopes for a third Friedrich among the Staufer supporters in Italy because of his name. However, when the king was elected he was discredited by his relationship to the Hohenstaufen. His candidacy against the curia would not have been enforced. The Wittelsbach Duke of Upper Bavaria Ludwig the Strict also retired as a supporter of the Hohenstaufen. In August 1273, in view of the ongoing election negotiations, the Pope gave the prince an ultimatum. The Archbishop of Mainz, Werner von Eppstein , then brought two new candidates, Count Siegfried von Anhalt and Rudolf von Habsburg, into the election negotiations. The electors agreed on Rudolf in September 1273, but could not obtain the consent of the Bohemian king. Instead, they left Duke Heinrich XIII. of Lower Bavaria for election. The Bohemian king stayed away from the election, he was represented by Bishop Berthold von Bamberg . Rudolf had received the news of his upcoming election as a king during a feud with the Bishop of Basel. He waited for the election in Dieburg, south of Frankfurt am Main .

On October 1, 1273, Rudolf was unanimously elected by the electors gathered in Frankfurt; on October 24, he and his wife were crowned king in Aachen by Archbishop Engelbert II of Cologne . With very few exceptions due to special circumstances, it became customary after the end of the interregnum to crown the king and queen together in Aachen's Marienkirche , today's cathedral. Medieval dynasties often referred to their predecessors to legitimize their claims. On the occasion of the coronation in Aachen, Rudolf changed the name of his wife Gertrud von Hohenberg to Anna and that of his daughter Gertrud to Agnes. With this, Rudolf placed himself and his house in the Zähringian tradition. Anna and Agnes were the names of the sisters and heiresses of the last Duke of Zähringen, Berthold V.

Ottokar tried in vain with his envoy to the Pope to prevent Rudolf from being granted a license to practice medicine. The Curia had reservations about Rudolf, who had long been a loyal supporter of the Hohenstaufen. Rudolf met these concerns in many ways. So he refrained from resuming Hohenstaufen politics in Italy. On September 26, 1274, the Pope also recognized Rudolf as the rightful king. Alfonso of Castile gave up his claim to royal rule in the empire only in 1275 in personal negotiations with the Pope.

Peter Moraw's view that the voters saw only a "transition candidate" in Rudolf , who was already 55 years old, was rejected by Kaufhold and Krieger. Since the princes had decided against the overpowering Bohemian king Ottokar, the future king had to use force to assert himself against this powerful competitor, and even if Rudolf did not belong to the rank of imperial princes , as a count he had risen to become the most powerful territorial lord in the south-west of the empire . Armin Wolf's thesis of a Welfisch - Ottonian descent, which Rudolf would have dynastically legitimized in the election of a king, did not meet with approval from experts.

Marriage policy

From Rudolf's marriage to Gertrud (Anna) von Hohenberg , who came from the Counts of Hohenberg , a branch of the Hohenzollern family, went with Mathilde (around 1254 / 56–1304), Katharina († 1282), Agnes (1257–1322), Hedwig († 1286), Clementia († 1293) and Guta (1271–1297) six daughters and with Albrecht I (1255–1308), Hartmann (1263–1281), Rudolf II (around 1270–1290) and Karl (1276 –1276) produced four sons. One of his first acts as a king was to secure his kingship. In view of the still existing claims of Alfonso of Castile and the disappointed ambitions for the succession of the Bohemian and French kings, considerable conflicts were to be expected. Rudolf held a double wedding on his coronation day in Aachen. His 20-year-old daughter Mathilde was married to the Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Upper Bavaria Ludwig II , one of his most important voters. Rudolf's daughter Agnes was married to Duke Albrecht II of Saxony. Rudolf later initiated the connections between Hedwig and Otto VI., The brother of Margrave Otto V of Brandenburg , and between Guta and Wenceslaus II. , The successor to the Bohemian King Ottokar. Through these marriages, Rudolf succeeded in binding all secular royal voters to his family as sons-in-law.

Revindications

From Rudolf as the new king, the electors expected the repatriation of the goods and rights that had been alienated from the empire since the late Baptist period. During the reign of Richard of Cornwall and Alfonso of Castile, who had little or no presence in the empire, many nobles had made use of the imperial estate . With the exception of Ottokar of Bohemia, legally questionable acquisitions by the Electors should remain unaffected by Rudolf's claims for repayment. In the future, the electors had to give their consent to royal sales of imperial property. These letters of consent, also called letters of will , appeared more regularly as a means of granting consensus under Rudolf von Habsburg. After he came to power, they were only issued by the electors. From the 12th to the 14th centuries, the circle of people who shared the empire with the king was determined more and more precisely. Since Rudolf, the right to have a say in imperial affairs has been linked to the right to elect a king.

The revindications began two days after Rudolf's coronation. On a court day on October 26, 1273, with the consent of the princes, all unlawfully levied customs duties since the reign of Frederick II were declared invalid. If necessary, the decision was enforced by military force against unauthorized customs posts. This affected the Margrave of Baden , for example . After a military conflict he had to give up his customs duties in Selz , which were not recognized by the king . On a court day in Speyer in December 1273 it was announced that all illegally acquired crown property was to be surrendered . The implementation was difficult because there was no reliable information about the illegal changes of ownership. In contrast to the English Treasury (Exchequer) or the French Chamber of Accounts (Chambre des Comptes), Rudolf had no financial authority. The king relied on those affected or on coincidence for his information. For the revindications, Rudolf relied on the bailiffs . The Swabian-Franconian area was organized into new administrative units , with the exception of the burgraviate of Nuremberg . For example, Swabia and Alsace were each divided into two bailiffs. At the head of these administrative units was a governor. He exercised royal rights in his administrative area as the king's deputy. The duties of the provincial bailiff included, in addition to reclaiming the lost imperial property, managing the financial income, maintaining peace, monitoring customs duties and taking care of the protection of monasteries and Jews. As Reichslandvögte, the king relied on relatives and confidants. According to Krieger, Rudolf's success in revision policy is difficult to assess. The revindications were apparently mainly successful in Swabia, Alsace and the Rhineland. On a court day in Nuremberg on August 9, 1281, the revindication objects were specified. Disposals of imperial property that had been made since the papal deposition of Frederick II in 1245 were to be regarded as null and void if no princely approval had been given.

In the immediate vicinity of his home country, Rudolf used the revindications to develop landscapes loyal to the Habsburg castle. A re-establishment of the Duchy of Swabia did not take place. From 1282 to 1291 he built a new landgraviate in the central Swabian region around the administrative center of Mengen . In the north, however, the late medieval royal rule was only weakly present. Rudolf was dependent on the territorial lords there to regain the lost imperial property. As governors or vicars ( administratores et rectores ) appointed by the king, Duke Albrecht II of Saxony , Albrecht I of Braunschweig and later the Margraves of Brandenburg were supposed to take care of the lost imperial estates in Saxony and Thuringia. In carrying out the revindications, the princes pursued their own territorial political goals and attached little importance to the interests of the empire. After the death of Duke Albrecht of Braunschweig on August 24, 1280, Rudolf awarded Albrecht II of Saxony and the three margraves Johann II , Otto IV and Conrad I of Brandenburg to the Johannine line the maintenance of the imperial estates in Saxony and Thuringia as well as the administration Lübeck.

Battle against the King of Bohemia (1273–1278)

At the court conference in Nuremberg in November 1274, Rudolf opened a trial against Ottokar von Böhmen. In all his actions the Roman-German king submitted to the approval of the princes. In disputes between the Roman-German king and an imperial prince, the Count Palatine near Rhine was appointed judge. As king, Rudolf had to present his complaints to the Count Palatine and all the princes and counts present. Within a period of nine weeks, Ottokar was supposed to answer to the Count Palatine at a court day in Würzburg. The Bohemian king let this period expire, trusting in his power. In May 1275 he sent his envoy, Bishop Wernhard von Seckau, to Augsburg for a court day. The bishop questioned Rudolf's choice and his kingship. Thereupon the princes recognized Ottokar from all imperial fiefs. On June 24, 1275 the imperial ban on the Bohemian king was proclaimed. Ottokar still showed no insight. After he had not broken away from the eight within a year, therefore, in June 1276, the disregard of the Bohemian king was pronounced. The Archbishop of Mainz pronounced the church ban and imposed the interdict on Bohemia. A military decision would end the conflict as a divine judgment for both sides .

Rudolf and Ottokar tried to win allies for the upcoming confrontation. Rudolf secured the support of Count Meinhard and Albert von Görz-Tirol through a marriage between his son Albrecht I and Elisabeth von Görz-Tirol . The territorial focus of the Counts of Görz-Tirol was in the southeastern Alpine region and thus in the immediate vicinity of Carinthia. Rudolf enfeoffed Philipp von Spanheim , the brother of the last Carinthian duke, with the Duchy of Carinthia and thus drew him to his side. Ottokar had only granted Philip the title of governor of Carinthia without any real influence. Rudolf also allied himself with Archbishop Friedrich von Salzburg , who was besieged in his territory by the Bohemian king. In Hungary, hostile aristocratic factions faced each other and fought for influence and the guardianship of the underage King Ladislaus IV. Rudolf succeeded in winning part of the Hungarian nobility on his side. Relations with Duke Heinrich von Niederbayern had become more problematic since Rudolf's election. Heinrich did not see his commitment in the king's election sufficiently rewarded. The Duke of Lower Bavaria with the control of the Danube access to Austria was of decisive importance for the upcoming dispute. By confirming his right to vote, Rudolf was able to bind the duke to himself. Rudolf's illegitimate son Albrecht von Löwenstein-Schenkenberg also took part in the campaign against Ottokar.

Opposite Pope Gregory X. Rudolf had committed himself to a trip to Rome with the aim of the imperial coronation. As a result, military planning came to a standstill in 1275. Due to the unexpected death of the Pope on January 10, 1276, Rudolf's priorities shifted again to the dispute with the Bohemian king. The burgrave of Nuremberg Friedrich III. invaded the Egerland . In Carinthia and Carniola, Bohemian rule collapsed immediately after the invasion of the Tyrolean counts. Rudolf decided at short notice to change his tactics and lead the main attack not against Bohemia, but against the weak Bohemian rule in Austria. The new tactic also had the advantage that Duke Heinrich von Niederbayern, whose stance remained obscure, could not attack Rudolf's army from behind if he changed parties. Under pressure from the royal army in Regensburg, the Duke of Lower Bavaria clearly acknowledged the Habsburgs in return for appropriate concessions. Rudolf had to consent to a marriage between his daughter Katharina and Heinrich's son Otto . In return, Rudolf was given free access to the Danube and was able to reach the Austrian states with his troops by ship as quickly as possible. The Habsburgs were also able to take these quickly. Only Vienna offered longer resistance, but could also be defeated. In Bohemia, the nobility took advantage of the situation for a revolt. Ottokar had to give in.

In Vienna, Ottokar had to make peace on October 21, 1276. On November 25th, Rudolf, in street clothes and on a wooden stool, received the homage to Ottokar. With this, Rudolf deliberately humiliated the Bohemian king, who was concerned about public recognition, because he had appeared for the enfeoffment act in splendid robes and a large entourage. This scene was particularly humiliating for Ottokar and his wife Kunigunde. For them, Rudolf was just a little count who assumed the royal dignity. Ottokar had to recognize Rudolf as king and publish his legally questionable acquisitions, the duchies of Austria, Styria and Carinthia with Carniola and Pordenone. With the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Margraviate of Moravia, he should belehnt be. The feudal act expressed a hierarchization between the enthroned king and imperial prince. Ottokar received his fiefdom from the king with bent knees in the presence of numerous ecclesiastical and secular princes. For the first time in the Reich, bent knees are unequivocally proven in the act of lending. In return, Ottokar was freed from eight, excommunication and interdict. The peace was to be secured by a double marriage between Ottokar's daughter and a son of Rudolf and between Ottokar's son Wenzel II and Rudolf's daughter Guta .

The peace was short-lived. Both sides had reasons for another military confrontation. The Bohemian king did not forget the humiliations suffered in Vienna. The provocation was intensified by the fact that Rudolf had contacts with the aristocratic opposition, especially the Rosenbergs , in Bohemia and Moravia. For this purpose, Ottokar continued to have contact with his former confidante in the Austrian states. In the southeast, Rudolf wanted to replace the Bohemian king with the Habsburgs. In June 1278 the war broke out again. However, the support for Rudolf had diminished. With the exception of the Count Palatine, Rudolf had found no supporters for the struggle against Bohemia among the electors. The Archbishop of Cologne had established friendly relations with the Bohemian king. In addition to Margrave Otto V of Brandenburg , the Bohemian was able to make substantial payments to Duke Heinrich XIII. from Niederbayern win for themselves. Heinrich closed his country to Rudolf's troops and allowed the Bohemians to hire mercenaries in Lower Bavaria. The Silesian and Polish dukes also supported Ottokar. After all, Rudolf received the support of the Hungarian King Ladislaus IV. It was no longer the princes but the Habsburg power and the Hungarian troops that Rudolf raised against Ottokar.

On August 26, 1278, the battle of Dürnkrut, northeast of Vienna took place. Rudolf took part in the battle himself at the age of 60. He fell from his horse and could only be saved by a Thurgau knight who put him on a new horse. During the battle, Rudolf had held back a reserve unit of around 60 knights. The flank attack of these knights had devastating consequences for the Bohemians and brought Rudolf the victory. The Bohemian army was divided into two parts and lost order. The Hungarian light cavalry pursued the enemy. Many thousands of Bohemians perished. Contrary to the traditional knightly honor, Ottokar was not taken prisoner, but was slain in revenge by some Austrian nobles. Rudolf had the embalmed body of Ottokar exhibited in Vienna for several weeks. In gratitude for his victory over the Bohemian king and rescue from danger of death, Rudolf founded a monastery in Tulln . It remained his only monastery foundation.

Power politics in the southeast

The battle was of European importance. It created the basis for the later Danube empire, in which the Austrian states were to form the power-political center. The Habsburg dynasty rose to become a royal and grand dynasty. The Bohemian king's widow Kunigunde feared that Rudolf would seize Bohemia and Moravia as well. Therefore she called Margrave Otto V of Brandenburg as guardian for her underage son Wenzel II. Even the imperial princes did not want to build up an overpowering imperial dynasty with the Habsburgs instead of the Přemyslids . In view of the balance of power, Rudolf was content with what had been achieved at the moment. Ottokar's son Wenceslaus was recognized as his successor in Bohemia and Moravia. The marriage projects planned during the first peace of 1276 were carried out. Rudolf's daughter Guta was married to Wenzel II and Rudolf's son of the same name, Rudolf II, to Kunigundes daughter Anna. Due to the Brandenburg protectorate, Bohemia was withdrawn from the Habsburg control. The marriage connections at least gave the freedom of action to be able to access Bohemia later. The fickle in his attitude towards Rudolf, Duke Heinrich von Niederbayern, was able to be tied more closely through a marriage project: Rudolf's daughter Katharina was married to Heinrich's son Otto III. married.

Instead of in Bohemia, the Habsburg wanted to create a new power base in the southeast of the empire. Rudolf stayed in the southeast of the empire almost without interruption from 1276 to Pentecost 1281. This unusually long stay served the aim of consolidating the situation in Austria and Styria for the Habsburgs. When analyzing the introductions to the royal documents ( Arengen ), Franz-Reiner Erkens was able to determine that since Rudolf's long stay in the document practice, late-Staufer models were used formally and stylistically. The continuity to the Hohenstaufen was supposed to give Rudolf's kingship additional legitimation. After lengthy negotiations, in the summer of 1282 he obtained the approval of the electors in letters of will for the successor to his sons in the Austrian lands. On a court day in Augsburg on December 27, 1282, Rudolf enfeoffed his sons Albrecht and Rudolf with the countries of Austria, Styria, Carniola and the Windischen Mark as a whole, i.e. jointly. The two dukes were thereby elevated to the rank of imperial prince. However, this lending met resistance from the Austrian gentlemen. Six months after the deed, Rudolf had to leave the Austrian duchies to his son Albrecht in the Rheinfeld house rules of June 1, 1283. As a result, the dominance of the Habsburg dynasty shifted from Upper Alsace, Aargau and Zürichgau to the southeast. The Habsburgs ruled Austria until the early 20th century.

Rudolf's policy of domestic power also endangered the rule of consensus and fueled the fear of a power-hungry king among the princes. For the succession of the sons to the king, the king needed the approval of the electors. Rudolf therefore had to reduce his household power: Albrecht and Rudolf renounced the Duchy of Carinthia in 1286 . Meinhard II was enfeoffed with the duchy.

Court and rulership practice

In his court rulership and rulership, Rudolf often drew on the Hohenstaufen tradition. However, he had the government acts of his immediate royal predecessors William of Holland and Richard of Cornwall declared invalid, unless they had the majority approval of the electors. As a sign of continuity with the Hohenstaufen, Rudolf re-appointed the court judge office created by Friedrich II in 1235 as one of his first acts.

Until well into the 14th century, medieval royal rule in the empire was exercised through outpatient rulership practice. Rudolf had to travel through the empire and thereby give his rule validity and authority. The late medieval kingship could not cover all areas of the empire equally. Peter Moraw has therefore divided the empire into zones of different proximity or distance to the king. At the time of Rudolf, southern and western Germany as well as central Germany were considered "close to the king". The north of the empire, which Rudolf did not enter, was considered to be a “remote” landscape. Contacts there were limited to embassies. With the help of the imperial city of Lübeck , Rudolf tried in vain to assert his authority in the north. Longer stays with only short interruptions are recorded between 1276 and 1281 for Vienna and from December 1289 to November 1290 for Erfurt. The favorite Palatinate of the late Hohenstaufen, Hagenau, came second after Basel (26) with 22 stays. In Basel, Rudolf created a permanent memoria for his house with the funeral of his wife Anna and his sons Karl and Hartmann in the local cathedral . The ruler still had no permanent residence. The court formed the "organizational form of rule". It was "within reach of verbal orders" and thus largely evaded writing. Personal relationships at court were therefore of great importance. The "difficult path to the ruler's ear" only led through the intercession of closest confidants of the Habsburgs. Friedrich von Zollern , Heinrich von Fürstenberg and Eberhard von Katzenelnbogen had the greatest influence at his court .

16 farm days have been handed down for Rudolf's reign. The Hoftage are considered to be the “most important political concentration points” in the empire of the 12th and 13th centuries. The number of princes gathered on a court day made clear the strength and integrative power of the royal rule. As political assemblies, the court days represented the hierarchy of king and prince in the empire. The identification of the rank and status of the princes at the meetings was of considerable importance for the political and social order in the empire. The long time without court days due to the interregnum also increased the pressure of the princes to assert previous or new claims to rank. Through their personal appearance, the princes were able to express their position in the power structure of the empire in a representative way. Ever since Rudolf came to power, the sources regularly record seat disputes on court days. The court day thus offered Rudolf the best opportunity to stage the royal rule. The Habsburg court no longer had such an attraction for culture and science as the court of Frederick II once did, but it retained its importance for deliberation and consensual decision-making.

Rudolf invited to his first court day in 1274, using the metaphor common in the Staufer period of the king as head (caput) and of the princes as members of the empire. Rudolf also used the rhetoric of head and limbs in the Arengen , the introductions to his documents. It showed that his dispositions in the kingdom were bound to the approval of clerical and secular princes. The princes usually only attended the Habsburg court days for personal interests or special occasions. Rudolf's reign reached a climax with the very well-attended Christmas Court Day in Erfurt in 1289. Rudolf held the last court day on May 20, 1291 in Frankfurt am Main.

Arbitration proceedings at court "exploded". The rise in arbitration is seen as a consequence of the interregnum. The most important part of the court was the chancellery . She was responsible for issuing the certificates. In the 13th and 14th centuries, considerably more documents were drawn up than before. From Rudolf's eighteen-year rule, 2223 documents have survived, 622 of them (28%) for a city and less than 70 (3%) for northern German recipients. Rudolf constantly obtained acts of consensus in his government activities. Rudolf repeatedly emphasized the general approval of the princes in his documents or singled out individual gentlemen. In addition to the form of documents, political action in the late Middle Ages was communicated through staging using non-verbal and symbolic acts.

Urban politics

Under Rudolf's rule, the term imperial cities (civitates imperii) became common for royal cities . In the interregnum, the cities became increasingly independent, and the king's power of disposal declined. Nevertheless, the imperial cities became a support for the exercise of royal rule through their military potential and financial strength. The regular city tax was an important source of income for Rudolf. In addition, the cities of Rudolf increasingly served as royal accommodation. Rudolf tried to enforce the royal right to host the ecclesiastical princes. In response to the bishops' resistance, Rudolf demonstratively favored the cities. Of his 2,223 documents, 662 went to a city and 222 cities were among the 943 recipients. He allowed the imperial cities the council constitution and thus a certain internal independence. In addition, Rudolf promoted the development of the episcopal cities into free cities. The city of Colmar z. B. granted Rudolf generous liberties in 1278. The citizens could receive fiefs and form guilds. They were also exempt from death tax. However, his taxation measures generated considerable resistance in the cities. Rudolf tried in vain to enforce direct individual taxation of city citizens in 1274 and 1284. Nevertheless, Rudolf succeeded in systematically integrating the rising urban bourgeoisie into imperial politics for the first time.

Occurrence of "false peace"

The belief in a return of Emperor Frederick II has been documented since 1257, along with the hope of a new Emperor Frederick. Under Rudolf von Habsburg, there was a boom in the " false peace " in the 1280s . The distant grave was crucial to the fact that by the end of the 13th century people appeared in Germany who claimed to be the Staufer Emperor. The “false Friedriche” show the popularity of Frederick II and the hope of a return to the Hohenstaufen conditions, which research interprets as a reaction to current social crises caused by famine, bad harvests or price increases . On the other hand, Krieger attributes the “false Friedriche” solely to Rudolf's controversial tax policy.

In 1284 a hermit appeared between Basel and Worms by the name of Heinrich, who referred to himself as "Kaiser Friedrich". The "false Friedrich" disappeared without a trace when Rudolf arrived in July. The most successful "false Friedrich" was Dietrich Holzschuh (Low German Tile Kolup ). Around 1283/84 he tried his luck in Cologne in vain, where he was expelled. In Neuss , however, he was quickly recognized. For a year he asserted himself extremely successfully as a Friedrich impersonator. He held court first in Neuss and then in Wetzlar . He issued his certificates with forged imperial seals. With his large income he was able to surround himself with a court. He also managed to take oaths on himself. Kolup justified the long absence of Friedrich, who has now allegedly returned, with a pilgrimage he had undertaken. Rudolf von Habsburg moved to Wetzlar with an army. In his presence the "false Friedrich" was burned at the gates of the city.

Peace policy

A well-recognized king had to remedy the lack of peace and justice perceived by contemporaries. The Reich administration was reorganized in Franconia. At the regional court of Rothenburg , the records in court books began in 1274. They are among the oldest of their kind. Rudolf began a royal peace policy , which was initially limited to regional and time-limited agreements. In 1276 a country peace limited to Austria was issued. This was followed by 1281 Landfrieden for the regions of Bavaria, Franconia, Rhineland and again Austria. The north, far from the king, could not be included in the same way; the individual territorial lords took over the security of peace there. In Würzburg, on March 24, 1287, based on the example of the Mainz State Peace, the peace was extended from 1235 to the entire empire for a limited period of three years.

In Rudolf's last years, the settlement of disputes and the safeguarding of imperial interests were the focus, especially in Thuringia. From December 1289 to November 1290 he stayed in Saxony and Thuringia to restore the authority of the king. With the places of residence in Erfurt and Altenburg, he followed up on models from the Hohenstaufen era. In the winter of 1289/90 the king in Thuringia destroyed 66 or 70 robber castles according to Saxon information and had 29 robber barons beheaded on one day in December at the gates of Erfurt. During his stay in Thuringia, Rudolf reclaimed the entire Pleißnerland for the empire.

Reaching out to Burgundy and contacts to France

After the end of the armed conflict with the Bohemian king and the acquisition of the Austrian lands for the House of Habsburg, Rudolf concentrated on Burgundy, which was far from the king, from 1283 onwards. Under Burgundy the bordering France southwestern in this context is part of the empire to understand the Provence , known as the Franche-Comte , the Dauphiné (county Vienne ) and the counties Mömpelgard and Savoy , but not belonging to France Duchy of Burgundy with its capital Dijon included . Derived from the coronation city of Arles , the Burgundian part of the empire is often referred to as regnum Arelatense or Arelat in historical studies . The imperial power in the Arelat was always only weakly developed.

Count Rainald von Mömpelgard had taken Elsgau from the Basel bishop Heinrich von Isny , a close partisan of Rudolf . Rudolf decided to intervene militarily. Count Rainald could not count on greater support and holed up in Pruntrut . After Rudolf had besieged the city for a month, the count had to give up his claims on April 14, 1283, but without having to take the oath of fief to Rudolf. Subsequently, Rudolf undertook an advance against Count Philip I of Savoy . The Counts of Savoy had strategically important possessions to which Rudolf wanted to secure access as part of his Burgundy policy. Hostilities began as early as 1281, but it was not until the summer of 1283 that the king proceeded on a larger scale against the count. After a long siege of the city of Peterlingen , Count Philipp gave up; in the peace of December 27, 1283 he had to hand over the cities of Peterlingen, Murten and Gümminen to Rudolf. He also had to pay a war indemnity of 2,000 silver marks.

The French expansion policy affected territory along the Schelde , Meuse , Saône and Rhone . A marital connection with the Burgundian ducal house should ensure better relations with France. In February 1284, at the age of 66, Rudolf married 14-year-old Isabella of Burgundy , a sister of Duke Robert II of Burgundy , brother-in-law of the French King Philip III . His first wife Anna died in 1281. Through the marriage, Rudolf tried to increase his influence in the Arelat. Robert was enfeoffed with the county of Vienne . In spite of family ties and imperial mortgages, Rudolf II was unable to weaken his opponents, the Counts of Savoy, Count Palatine Otto of Burgundy and Count Rainald von Mömpelgard, through Robert II . His hope for a connection to the French house was not fulfilled either. Robert II took the side of the French king Philip IV , who had succeeded his deceased father in October 1285. Philip IV expanded the French sphere of influence in the border area considerably and also pursued interests in the Arelat, where several areas subsequently fell to France. This includes the attempt to gain control of the Free County of Burgundy. In 1289 Rudolf forced the homage of Otto of Burgundy through a campaign, who was based on France. After Rudolf's death, however, Count Palatine Otto concluded a contract with Philip IV in 1295, which provided that the free county should pass into French possession through a marriage relationship and in return for monetary payments.

Unsuccessful efforts for the imperial crown and successor

Eight popes officiated during Rudolf's 18 years of reign. Pope Gregory X had promised Rudolf the imperial crown if he took over the leadership of a crusade. Gregor's unexpected death thwarted plans for an imperial coronation and the crusade enterprise. The following popes Innocent V , Hadrian V and John XXI. exercised their pontificate only from January 1276 to mid-1277. Pope Nicholas III officiated from 1277 to August 1280, but gave no priority to the crusade project. Rudolf's negotiations with his successors Honorius IV and Nikolaus IV were unsuccessful. Despite the numerous changes in people, it was possible to agree on specific dates for a coronation three times (1275, 1276 and 1287). Rudolf's daughter Clementia was married in 1281 to Karl Martell , son of Charles II of Anjou . This marriage connection between the houses of Habsburg and Anjou was part of an overarching plan that had been pushed forward by the curia since 1278. In this context, Rudolf was promised the imperial crown. From the Arelat an independent kingdom was to be formed under the rule of the House of Anjou, the claims of the empire to the Romagna were to be dropped. Except for the marriage, however, the plan did not materialize. Only Rudolf's later successor, Henry VII , was to receive the dignity of Emperor again in Rome in 1312.

Rudolf's pursuit of the imperial dignity was primarily intended to secure the succession to his son and thus to found a dynasty. As emperor he could have raised a fellow-king. With the Ottonians, Salians and Hohenstaufen this was always the imperial son. Initially, Rudolf wanted to make his son Hartmann his successor. Hartmann drowned in the Rhine in December 1281. In the last years of his life, only his sons Albrecht and Rudolf remained. Rudolf tried to build up his son of the same name as a candidate for king. In 1289 and again in 1290 he confirmed the Bohemian voting vote to his son-in-law Wenceslaus. In return, Wenzel agreed to the royal succession of Rudolf's son on April 13, 1290 at a court in Erfurt, but Rudolf's son died unexpectedly on May 10, 1290 in Prague. The only surviving king's son, Albrecht, did not find approval from the electors on a court day in Frankfurt on May 20, 1291, only Count Palatine Ludwig stood up for him. Instead of the Habsburg Albrecht, Count Adolf von Nassau from the Middle Rhine was elected in 1292 .

death

At the beginning of the summer of 1291 Rudolf's health deteriorated considerably. Shortly before his death, the seventy-three year old king decided to move from Germersheim to Speyer. The imperial cathedral in Speyer was a memorial of the Salian-Staufer dynasty and was the most important burial place of the Roman-German kingship. Rudolf wanted to place himself in the Salian-Staufer tradition and clarify the rank of the Habsburgs as a royal family. One day after his arrival in Speyer, on July 15, 1291, he died of old age in connection with a gout disease. Rudolf was buried next to the Staufer King Philip of Swabia in the Speyer Cathedral. The still preserved grave slab was made by an artist during the king's lifetime. It is considered to be one of the first realistic depictions of a Roman-German king at all.

effect

Late medieval judgments

In the late Middle Ages, Rudolf played the role of top man for the Habsburg dynasty. The Habsburgs owed their rise to the imperial prince status and their ability to become a king to Rudolf.

The royal court and the Habsburg power centers in northern Switzerland and Alsace actively pursued rulership propaganda for Rudolf. Even more important for spreading his fame were the bourgeois elites of the city of Strasbourg, as well as the southern German Minorites and Dominicans . The citizens of the city of Strasbourg saw the Habsburg as an ally after the fighting with their bishop (1262). On the Upper Rhine the mendicant monks spread numerous anecdotes about Rudolf. In the spirit of the church's poverty movement, he was portrayed as an unpretentious king who was humble towards God and the church.

As a result, a large number of contemporary narratives and anecdotes, some of which have been instrumentalized for propaganda purposes, have come down to us about Rudolf von Habsburg, to which historiography has often given little source value. Karl-Friedrich Krieger gave greater importance to the anecdotes. According to Krieger, they "bring you closer to Rudolf's individual personality than hardly any other king of the 13th century". A total of 53 narrative motifs could be identified with certainty. Rudolf is characterized as "just, shrewd, sometimes cunning, sometimes even daring, but never brutal or tyrannical". On a campaign in Burgundy he is said to have pulled beets out of the field by hand and then ate them, or he is said to have mended his tattered doublet himself on a campaign. In Erfurt he is said to have advertised Siegfried von Bürstädt's beer. After Johannes von Winterthur and Johannes von Viktring , nobody could pass Rudolf's long eagle nose ("Habsburg nose"). One man had claimed that he couldn't get past him because of the long king's nose. Rudolf then pushed his nose aside with a laugh. In numerous other stories, the king's life was in danger and was saved by loyal followers.

The contemporary representations and medieval historiography described Rudolf as humorous and popular. His portrait on the grave slab was praised by contemporaries of the late 13th century for its closeness to reality. According to Martin Büchsel, the grave slab does not show the character of a sullen and resigned ruler, but the new image of the king after the end of the interregnum. The grave figure was lost for centuries and was damaged. Its restoration in the 19th century is problematic because it is different from the painting of the grave plate, Hans Knoderer on behalf of Maximilian I created. Now it is in the crypt of the Speyer Cathedral.

Modern

In the 18th century, and especially in the Vormärz and the Biedermeier period of the 19th century, a large number of poems, dramas and legends about Rudolf von Habsburg were written . Not least as the first Habsburg to be elected Roman-German king, Rudolf was a popular subject. With their dynastic-Habsburg perspective, the German-language dramas often glorified Rudolf von Habsburg ( Friedrich August Clemens Werthes : Rudolph von Habsburg 1785; Anton von Klein : Rudolf von Habsburg 1787; Anton Popper : Rudolf von Habsburg 1804). In poetry, the virtues of humility and piety were often emphasized to characterize the Habsburgs. In 1803, in his poem Der Graf von Habsburg, Friedrich Schiller addressed “the emperorless, the terrible time” that ended with Rudolf's election. When Schiller finished his poem in April, the Holy Roman Empire was only a historical entity due to the main Imperial Deputation. The adaptations of August von Kotzebue ( Rudolph von Habsburg and King Ottokar von Böhmen 1815) and Christian Ludwig Schöne ( Rudolf von Habsburg 1816) tried to dramatically exaggerate the Habsburgs by highlighting the negative sides of the Bohemian king. In his play König Ottokars Glück und Ende (1825), Franz Grillparzer brought Rudolf's conflict with the Bohemian king to the stage. Rudolf appears in a soldier's coat as a peace-bringer who has returned from the crusade. Grillparzer paralleled the fate of Ottokar with that of Napoleon Bonaparte .

King Ludwig I of Bavaria had Ludwig Schwanthaler erect a tomb in Speyer Cathedral in 1843 . Arthur Strasser created a Rudolf statue in Vienna in 1912 . At Germersheim , on October 18, 2008, the four-lane Rhine bridge, which had been completed there in 1971, was named Rudolf-von-Habsburg-Brücke .

Research history

In the 19th century, historians in Germany were looking for the reasons for the late emergence of the German nation state. The epoch of the German Imperial Era from 900 to 1250 was described as the Golden Age , because the German Empire of the Ottonians , Salians and Staufers held the primacy in Europe and surpassed the other empires in size, splendor and power. Historians viewed medieval history from the perspective of royal power. Rulers were measured according to whether they achieved an increase in power or at least prevented a decline in power over princes and the papacy. In this historical picture, the Staufer Friedrich II was considered the last representative of German imperial glory. With his death, medieval studies let the late Middle Ages begin, which was considered to be an era of disintegration and a dark time of powerlessness. Late medieval kings such as Rudolf von Habsburg or Charles IV , who wanted to end the decline of imperial power, failed because of the elective monarchy in which the ruler had to buy the support of the electors with numerous concessions. Princes and popes were seen as representatives of self-interest who opposed the powerful unity of the empire. This view of history pervaded scientific work until the second half of the 20th century. Since the 1970s, the research of Ernst Schubert , František Graus and Peter Moraw has brought the late Middle Ages into focus. Since then, royal rule is no longer seen from the point of view of an irreconcilable conflict between king and prince, but it is emphasized that the cooperation between king and prince "belonged to the consensual decision-making structure practiced as a matter of course".

In 1903 Oswald Redlich presented a monumental, Greater German Catholic- oriented biography of Rudolf von Habsburg. The 800-page work is still considered to be irreplaceable in the professional world thanks to the extensive evaluation of sources. Redlich saw “Rudolf's importance and his contribution to Germany” in “that he saw with a clear view the fall of the old empire, that he courageously dropped all those Hohenstaufen claims, that he essentially restricted the new kingship and empire to German soil wanted to". Redlich's comprehensive presentation could be one reason why the reign of Rudolf von Habsburg afterwards met with little interest in historical studies.

In his presentation, published in 1989, From Open Constitution to Structured Compression, Peter Moraw described the period from Rudolf's rule to that of Henry VII as the age of the “little kings”. Compared to the other European kingdoms, the structural foundations of the Roman-German kingship were worse. On the occasion of the 700th anniversary of death, a conference was held in Passau in November 1991. Franz-Reiner Erkens judged the Habsburg ruler as a "pragmatist of a conservative style" and showed how much the Staufer tradition had an effect even after the Interregnum. Erkens saw innovative approaches in the reorganization of the imperial castle system, in the urban tax system and in the dynastic power policy. At the Passau conference, Moraw elaborated on his thesis of the "little kings" with regard to Rudolfs. It found both criticism and approval in history. A hundred years after Redlich's work, Karl-Friedrich Krieger presented a new biography in 2003. Krieger identified a “pragmatic attitude” with Rudolf, which gave him the opportunity to “set signs for the future”. Accordingly, it was Rudolf's merit "to have fundamentally re-activated the royal power of peace, which had largely been abandoned in the interregnum, and [...] brought it back to life". In contrast to Moraw's view, for Krieger the first king of the Habsburg dynasty was “not a 'little' king because of his skills and energy, but an important king”, “who does not shy away from comparison either with other contemporary rulers or with his late medieval successors in the empire got to".

To mark the 800th anniversary of his birth, the European Foundation for the Imperial Cathedral of Speyer organized a scientific symposium on “King Rudolf I and the Rise of the House of Habsburg in the Middle Ages” in April 2018. The symposium, chaired by Stefan Weinfurter and Bernd Schneidmüller , marks the beginning of the preoccupation with the topic, which will lead to a special exhibition at the Historisches Museum Speyer in 2021 .

swell

- The regests of the empire under Rudolf von Habsburg 1273–1291 (= JF Böhmer, Regesta Imperii. Vol. VI, Department 1). Edited by Oswald Redlich . Innsbruck 1898 ( digitized ; ND Hildesheim 1969).

- Regesta Habsburgica 1: The Regesta of the Count of Habsburg up to 1281. Edited by Harold Steinacker . Innsbruck 1905.

literature

Biographies

- Oswald Redlich : Rudolf von Habsburg. The German Empire after the fall of the old Empire. Innsbruck 1903 (and reprints; digitized in the Internet Archive ). [still fundamental, although obsolete in terms of details and some evaluations]

- Karl-Friedrich Krieger : Rudolf von Habsburg. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-13711-6 ( review ).

- Thomas Zotz : Rudolf von Habsburg. In: Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I. CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50958-4 , pp. 340–359, 587 f.

Representations

- Egon Boshof , Franz-Reiner Erkens (ed.): Rudolf von Habsburg: 1273–1291. A royal rule between tradition and change (= Passau historical research. Volume 7). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1993, ISBN 3-412-04193-9 .

- Martin Kaufhold : German Interregnum and European Politics. Conflict resolution and decision-making structures 1230–1280 (= Monumenta Germaniae historica. Volume 49). Hahn, Hannover 2000, ISBN 3-7752-5449-8 .

- Ulrike Kunze: Rudolf von Habsburg. Royal peace policy in the mirror of contemporary chronicles (= European university publications. Volume 895). Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2001, ISBN 3-631-37547-6 (also: Berlin, Technical University, dissertation, 2000).

- Christel Maria von Graevenitz: The peace policy of Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291) on the Lower Rhine and in Westphalia (= Rhenish archive. Publications of the Institute for Historical Regional Studies of the Rhineland at the University of Bonn. Volume 146). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2003, ISBN 3-412-15302-8 .

- Bernd Schneidmüller (Ed.): King Rudolf I and the rise of the House of Habsburg in the Middle Ages. wbg Academic, Darmstadt 2019, ISBN 978-3-534-27125-2 .

Lexicon articles and overview works

- Peter Moraw : From an open constitution to structured condensation. The empire in the late Middle Ages 1250–1495 (= Propylaea history of Germany. Volume 3). Propylaeen Verlag, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-549-05813-6 .

- Franz-Reiner Erkens: Rudolf I . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 7, LexMA-Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-7608-8907-7 , Sp. 1072-1075.

- Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd updated edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-17-018228-5 , pp. 11-74.

- Martin Kaufhold: Rudolf I. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11203-2 , pp. 167-169 ( digitized version ).

- Michael Menzel : The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt. Handbook of German History . Volume 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-608-60007-0 , pp. 80-109.

- Peter Niederhäuser: Rudolf I (von Habsburg). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

Web links

- Literature by and about Rudolf I in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications on Rudolf von Habsburg in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

Remarks

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Paul-Joachim Heinig: Habsburg. In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 85–96, here: p. 85. Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 14.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 80.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 14.

- ↑ See Oswald Redlich: Rudolf von Habsburg. The German Empire after the fall of the old Empire. Innsbruck 1903, p. 16 ( digitized in the Internet Archive , reprint: Aalen 1965).

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, pp. 60f.

- ↑ Amalie Fößel: The Queen in the Medieval Empire. Exercise of power, rights of power, scope for action. Stuttgart 2000, p. 77 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ On this Martin Kaufhold: German Interregnum and European Politics. Conflict resolution and decision-making structures 1230–1280. Hanover 2000, p. 6.

- ↑ Peter Moraw: From an open constitution to a structured compression. The empire in the late Middle Ages 1250 to 1490. Frankfurt am Main et al. 1989, p. 202.

- ^ Martin Kaufhold: German Interregnum and European Politics. Conflict resolution and decision-making structures 1230–1280. Hannover 2000, esp. Pp. 136-167, 256-276.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 54.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 41.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Hubert Houben: Kaiser Friedrich II. (1194-1250). Ruler, man, myth. Stuttgart 2008, p. 201.

- ↑ The authenticity of this letter was doubted by Martin Kaufhold: Deutsches Interregnum und Europäische Politik. Conflict resolution and decision-making structures 1230–1280. Hanover 2000. By contrast, Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 96f.

- ↑ Amalie Fößel: The Queen in the Medieval Empire. Exercise of power, rights of power, scope for action. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 35 and 119 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Amalie Fößel: The Queen in the Medieval Empire. Exercise of power, rights of power, scope for action. Stuttgart 2000, p. 35 ( digitized version ); Gertrud Thoma: Name changes in ruling families of medieval Europe. Kallmünz 1985, pp. 204-206.

- ↑ Thomas Zotz: Centers and Peripheries of the Habsburg Empire in the Middle Ages. In: Jeannette Rauschert, Simon Teuscher, Thomas Zotz (eds.): Habsburg rule on site - worldwide (1300–1600). Ostfildern 2013, pp. 19–33, here: p. 22; Dieter Mertens: The Habsburgs as descendants and as ancestors of the Zähringer. In: Karl Schmid (Ed.): Die Zähringer. A tradition and its exploration. Sigmaringen 1986, pp. 151-174, especially pp. 155-162.

- ^ Bernd Schneidmüller: Rudolf von Habsburg. Stories of ruling in the empire and of dying in Speyer. In the S. (Ed.): King Rudolf I and the rise of the House of Habsburg in the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2019, pp. 9–42, here: p. 31.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 81.

- ↑ Peter Moraw: From an open constitution to a structured compression. The empire in the late Middle Ages 1250 to 1490. Frankfurt am Main et al. 1989, p. 213.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 100. Martin Kaufhold: German Interregnum and European Politics. Conflict resolution and decision-making structures 1230–1280. Hanover 2000, p. 433f.

- ↑ Armin Wolf: Why was Rudolf von Habsburg († 1291) able to become king? On the right to vote in the medieval empire. In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History . German Department. Vol. 109, 1992, pp. 48-94. See critical Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 87. Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 100f.

- ↑ On the dates of life and the number of descendants Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, pp. 290f. The period of the birth of their daughter Mathilde "around 1251", which is widespread there and often in the literature, cannot be correct, since Rudolf's marriage to Gertrud von Hohenberg was only concluded between July 1253 and March 8, 1254. Cf. Gabriele Schlütter-Schindler: Regis filia - comitissa palatina Rheni et Ducissa Bavariae. Mechthild von Habsburg and Mechthild von Nassau. In: Zeitschrift für Bayerische Landesgeschichte 60 (1997), pp. 183–252, here: p. 189 note 30 ( digitized version ), according to which Mathilde could be born between April and October 1254 at the earliest or from April / May 1256.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, pp. 90f.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 109.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Jürgen Dendorfer: mutual authority - Princely participation in the empire of the 13th century. In: Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm, Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013, pp. 27–41, here: p. 40.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller: Consensus - Territorialization - Self-interest. How to deal with late medieval history. In: Early Medieval Studies . Vol. 39, 2005, pp. 225–246, here: p. 243. Bernd Schneidmüller: Between God and the Faithful. Four sketches on the foundations of the medieval monarchy. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 36, 2002, pp. 193-224, here: p. 221.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 121.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 35. Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbook of German History. Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 92.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: Court and Court Day of King Rudolf of Habsburg. In: Peter Moraw: Deutscher Königshof, Hoftag and Reichstag in the later Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2002, pp. 387-415, here: p. 407. Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 166.

- ^ Franz Quarthal: royal landscape, duchy or princely territorial state. On the goals and results of the territorial policy of Rudolf von Habsburg in the Swabian-Northern Switzerland area. In: Egon Boshof, Franz-Reiner Erkens (ed.): Rudolf von Habsburg: 1273–1291. A royal rule between tradition and change. Cologne 1993, pp. 125-138.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 171.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 37 f.

- ^ Thomas Michael Martin: Rudolf von Habsburg's urban policy. Göttingen 1976, p. 54.

- ^ Jürgen Dendorfer: mutual authority - Princely participation in the empire of the 13th century. In: Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm, Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013, pp. 27–41, here: p. 39.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, pp. 131-135.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Meeting of rulers of the late Middle Ages. Forms - rituals - effects. Ostfildern 2007, pp. 167-169 ( online ).

- ^ Jörg Peltzer: Personae publicae. On the relationship between princely rank, office and political public in the empire in the 13th and 14th centuries. In: Martin Kintzinger, Bernd Schneidmüller (Hrsg.): Political public in the late Middle Ages. Ostfildern 2011, 147–182, here: p. 154.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The battle at Dürnkrut 1278. In: Georg Scheibelreiter (Hrsg.): Highlights of the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2004, pp. 154-165.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 153.

- ^ Thomas Zotz: Rudolf von Habsburg. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I Munich 2003, pp. 340–359, here: p. 347.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Between Hohenstaufen tradition and dynastic orientation: The Kingship of Rudolf von Habsburg. In: Egon Boshof, Franz-Reiner Erkens (ed.): Rudolf von Habsburg: 1273–1291. A royal rule between tradition and change. Cologne 1993, pp. 33-58, here: p. 36. Gerald Schwedler: Erased Authority. Denial of the past and reference by Rudolf von Habsburg to Staufers, opposing kings and the Salic defeat at Welfesholz. In: Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm and Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013, pp. 237–252, here: p. 238.

- ^ MGH Constitutiones 3; 1273-1298, ed. by Jacob Schwalm, Hanover / Leipzig 1904–1906, No. 339, p. 325 f.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller: Consensual rule. An essay on forms and concepts of political order in the Middle Ages. In: Paul-Joachim Heinig et al. (Ed.): Empire, regions and Europe in the Middle Ages and modern times. Festschrift for Peter Moraw. Berlin 2000, pp. 53-87.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Erased Authority. Denial of the past and reference by Rudolf von Habsburg to Staufers, opposing kings and the Salic defeat at Welfesholz. In: Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm and Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013, pp. 237–252, here: p. 239. Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 166f.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Between Hohenstaufen tradition and dynastic orientation: The Kingship of Rudolf von Habsburg. In: Egon Boshof, Franz-Reiner Erkens (ed.): Rudolf von Habsburg: 1273–1291. A royal rule between tradition and change. Cologne 1993, pp. 33-58, here: p. 37.

- ^ Rudolf Schieffer: From place to place. Tasks and results of research into outpatient domination practice. In: Caspar Ehlers (Ed.): Places of rule. Medieval royal palaces. Göttingen 2002, pp. 11-23.

- ^ Peter Moraw: Franconia as a landscape close to a king in the late Middle Ages. In: sheets for German national history. Vol. 112 (1976) pp. 123-138 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 111.

- ↑ Thomas Vogtherr: Rudolf von Habsburg and Northern Germany. On the structure of the royal rule in an area remote from the king. In: Egon Boshof, Franz-Reiner Erkens (ed.): Rudolf von Habsburg. A royal rule between tradition and change. Cologne et al. 1993, pp. 139-163.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 276–282, here: p. 277.

- ^ Thomas Zotz: Rudolf von Habsburg. In: Bernd Schneidmüller and Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): German rulers of the Middle Ages. Munich 2003. pp. 340–359, here: 356.

- ↑ Thomas Zotz: Centers and Peripheries of the Habsburg Empire in the Middle Ages. In: Jeannette Rauschert, Simon Teuscher, Thomas Zotz (eds.): Habsburg rule on site - worldwide (1300–1600). Ostfildern 2013, pp. 19–33, here: p. 23.

- ↑ Peter Moraw: What was a residence in the German late Middle Ages? In: Journal for Historical Research . Vol. 18, 1991, pp. 461-468.

- ^ Peter Moraw: Councilors and Chancellery. In: Ferdinand Seibt (Ed.): Emperor Karl IV. Statesman and patron. Munich 1978, pp. 285-292, here: p. 286.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Relatives, friendship, clientele. The difficult way to the ruler's ear. In: Ders .: Rules of the game of politics in the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 1996, pp. 185-198.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 276–282, here: p. 278.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: Court and Court Day of King Rudolf of Habsburg. In: Peter Moraw: Deutscher Königshof, Hoftag and Reichstag in the later Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2002, pp. 387-415, here: p. 393 ( digitized version ). Franz-Reiner Erkens: Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 276–282, here: p. 279.

- ↑ Timothy Reuter: Only in the West anything new? The emergence of premodern forms of government in the European High Middle Ages. In: Joachim Ehlers (Ed.): Germany and the West of Europe. Stuttgart 2002, pp. 327-351, here: p. 347.

- ↑ Jörg Peltzer: Arranging the empire: who sits where on the court days of the 13th and 14th centuries? In: Jörg Peltzer, Gerald Schwedler, Paul Töbelmann (eds.): Political gatherings and their rituals. Forms of representation and decision-making processes of the empire and the church in the late Middle Ages. Ostfildern 2009, pp. 93–111.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Spieß: Thinking of rank and dispute over rank in the Middle Ages. In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Ceremonial and space. 4th Symposium of the Residences Commission of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, organized jointly with the German Historical Institute in Paris and the Historical Institute of the University of Potsdam, Potsdam, September 25-27, 1994. Sigmaringen 1997, 39–61.

- ^ Jörg Peltzer: Personae publicae. On the relationship between princely rank, office and political public in the empire in the 13th and 14th centuries. In: Martin Kintzinger, Bernd Schneidmüller (Hrsg.): Political public in the late Middle Ages. Ostfildern 2011, pp. 147–182, here: p. 166.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 276–282, here: p. 278. Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 177.

- ^ Jürgen Dendorfer: mutual authority - Princely participation in the empire of the 13th century. In: Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm, Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013, pp. 27–41, here: p. 38.

- ^ Jürgen Dendorfer: mutual authority - Princely participation in the empire of the 13th century. In: Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm, Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013, pp. 27–41, here: p. 37.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 276–282, here: pp. 278f.

- ↑ The quote from Bernhard Diestelkamp (ed.): Document recitals on the activities of the German royal and court courts until 1451. Vol. 3: The time of Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291). Edited by Bernhard Diestelkamp and Ute Rödel, Cologne et al. 1986, S. Xf. See in detail Ute Rödel: Royal jurisdiction and disputes between the princes and counts in the southwest of the empire 1250-1313. Cologne et al. 1979, pp. 127-208.

- ^ Jürgen Dendorfer: mutual authority - Princely participation in the empire of the 13th century. In: Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm, Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013, pp. 27–41, here: p. 39.

- ↑ Malte Prietzel: The Holy Roman Empire in the late Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2004, p. 14 and 21. Thomas Vogtherr: Rudolf von Habsburg and Northern Germany. On the structure of the royal rule in an area remote from the king. In: Egon Boshof, Franz-Reiner Erkens (ed.): Rudolf von Habsburg. A royal rule between tradition and change. Cologne et al. 1993, pp. 139–163, here: p. 142.

- ^ Bernd Schneidmüller: Rudolf von Habsburg. Stories of ruling in the empire and of dying in Speyer. In the S. (Ed.): King Rudolf I and the rise of the House of Habsburg in the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2019, pp. 9–42, here: p. 37.

- ↑ Claudia Garnier: Amicus amicis - inimicus inimicis. Political friendship and princely networks in the 13th century. Stuttgart 2000; Claudia Garnier: Signs and Writing. Symbolic acts and literary fixation using the example of peace agreements of the 13th century. In: Early Medieval Studies. 32: 263-287 (1998).

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 123 and 126. Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Malte Prietzel: The Holy Roman Empire in the late Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 185.

- ↑ Gabriela Signori : The 13th Century. An introduction to the history of late medieval Europe. Stuttgart 2007, p. 118.

- ↑ Malte Prietzel: The Holy Roman Empire in the late Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Thomas Michael Martin: Rudolf von Habsburg's urban policy. Göttingen 1976, p. 203. Approving Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Knut Görich: Friedrich Barbarossa - from redeemed emperor to emperor as a national redeemer figure. In: Johannes Fried, Olaf B. Rader (ed.): The world of the Middle Ages. Places of remembrance from a millennium. Munich 2011, p. 195–208, here: p. 199. Hannes Möhring : The prophecies about an emperor Friedrich at the end of time. In: Wolfram Brandes, Felicitas Schmieder (Ed.): Endzeiten. Eschatology in the monotheistic world religions. Berlin et al. 2008, pp. 201-213. Hannes Möhring: The world emperor of the end times. Origin, change and effect of a millennial prophecy. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 217-268.

- ^ Rainer Christoph Schwinges: Constitution and collective behavior. On the mentality of the success of false rulers in the empire of the 13th and 14th centuries. In: František Graus (Ed.): Mentalities in the Middle Ages. Sigmaringen 1987, pp. 177-202, here: pp. 190-192.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 193. Critical review by Karl Borchardt in: Das Historisch-Politische Buch 2005, p. 355f.

- ^ Hubert Houben: Kaiser Friedrich II. (1194-1250). Ruler, man, myth. Stuttgart 2008, p. 199.

- ↑ See for example Hubert Houben: Kaiser Friedrich II. (1194–1250). Ruler, man, myth. Stuttgart 2008, pp. 195-199. Oswald Redlich: Rudolf von Habsburg. The German Empire after the fall of the old Empire. Innsbruck 1903, pp. 532–541 ( digitized in the Internet Archive , reprint: Aalen 1965).

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, pp. 47-56.

- ↑ Marita Blattmann taking minutes in Roman canonical and German legal proceedings in the 13th and 14th centuries. In: Stefan Esders (ed.): Legal understanding and conflict management. Judicial and extrajudicial strategies in the Middle Ages. Cologne et al. 2007, pp. 141–164, here: p. 159.

- ↑ Thomas Vogtherr: Rudolf von Habsburg and Northern Germany. On the structure of the royal rule in an area remote from the king. In: Egon Boshof, Franz-Reiner Erkens (ed.): Rudolf von Habsburg. A royal rule between tradition and change. Cologne et al. 1993, pp. 139-163, here: pp. 157f.

- ↑ See in detail Christel Maria von Graevenitz: The Landfriedenspolitik Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291) on the Lower Rhine and in Westphalia. Cologne 2003, pp. 182-261.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Erased Authority. Denial of the past and reference by Rudolf von Habsburg to Staufers, opposing kings and the Salic defeat at Welfesholz. In: Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm and Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013, pp. 237–252, here: p. 242.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, pp. 164 and 220f.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 167.

- ↑ On Rudolf's Burgundy policy in detail Bertram Resmini: The Arelat in the field of forces of French, English and Angiovinischen politics after 1250 and the influence of Rudolf von Habsburg. Cologne 1980, p. 111ff. See also Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, pp. 208-215; Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, pp. 62–65.

- ↑ Brief overview from Hermann Kamp : Burgundy. History and culture. 2nd updated edition. Munich 2011.

- ↑ Bertram Resmini: The Arelat in the force field of French, English and Angevin policy after 1250 and the action of Rudolf von Habsburg. Cologne 1980, p. 238f.

- ↑ Bertram Resmini: The Arelat in the force field of French, English and Angevin policy after 1250 and the action of Rudolf von Habsburg. Cologne 1980, p. 177ff.

- ↑ Bertram Resmini: The Arelat in the force field of French, English and Angevin policy after 1250 and the action of Rudolf von Habsburg. Cologne 1980, p. 178.

- ↑ Bertram Resmini: The Arelat in the force field of French, English and Angevin policy after 1250 and the action of Rudolf von Habsburg. Cologne 1980, p. 186f.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 209.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003, p. 210.

- ↑ Bertram Resmini: The Arelat in the force field of French, English and Angevin policy after 1250 and the action of Rudolf von Habsburg. Cologne 1980, pp. 208ff.

- ↑ Thomas Frenz: The "Kaisertum" Rudolf von Habsburgs from an Italian perspective. In: Egon Boshof, Franz-Reiner Erkens (ed.): Rudolf von Habsburg. A royal rule between tradition and change. Cologne et al. 1993, pp. 87-102, here: p. 88.